Abstract

Medium-ring lactones are synthetically challenging due to unfavorable energetics involved in cyclization. We have discovered a thioesterase enzyme DcsB, from the decarestrictine C1 (1) biosynthetic pathway, that efficiently performs medium-ring lactonizations. DcsB shows broad substrate promiscuity towards linear substrates that vary in lengths and substituents, and is a potential biocatalyst for lactonization. X-ray crystal structure and computational analyses provide insights into the molecular basis of catalysis.

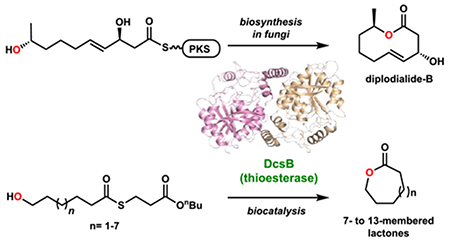

Graphical Abstract

Lactones of all sizes are found widely in bioactive natural products. Synthetically, the preparation of medium-ring (8-11 membered) lactones is significantly more challenging compared to small- and large-ring compounds.1 The reactivity of intramolecular lactonization of medium-sized rings is estimated to be nearly six-orders of magnitude slower than that of a five-membered lactone.2 The steep increase in activation energy arises from both entropic and enthalpic penalties, with the latter playing a dominant role due to transannular strain.2–3 Developing efficient strategies to construct such rings systems by cyclization of hydroxyacids has been an ongoing effort, anchored by methods such as Corey-Nicolau,4 Yamaguchi5, Mitsunobo,6 and others.7 Biocatalytically, enzymes responsible for forming small lactones and macrocycles are found in biosynthetic pathways,8 highlighted by the 12-membered and 14-membered forming pikromycin (Pik)9 and erythromycin (DEBS)10 thioestereases (TEs), respectively. However, there is no example of a natural enzyme that can promote lactonization to form 9- or 10-membered lactone rings.11 Discovering and characterizing enzymes that can catalyze such reactions can therefore bridge this notable inventory and knowledge gap.

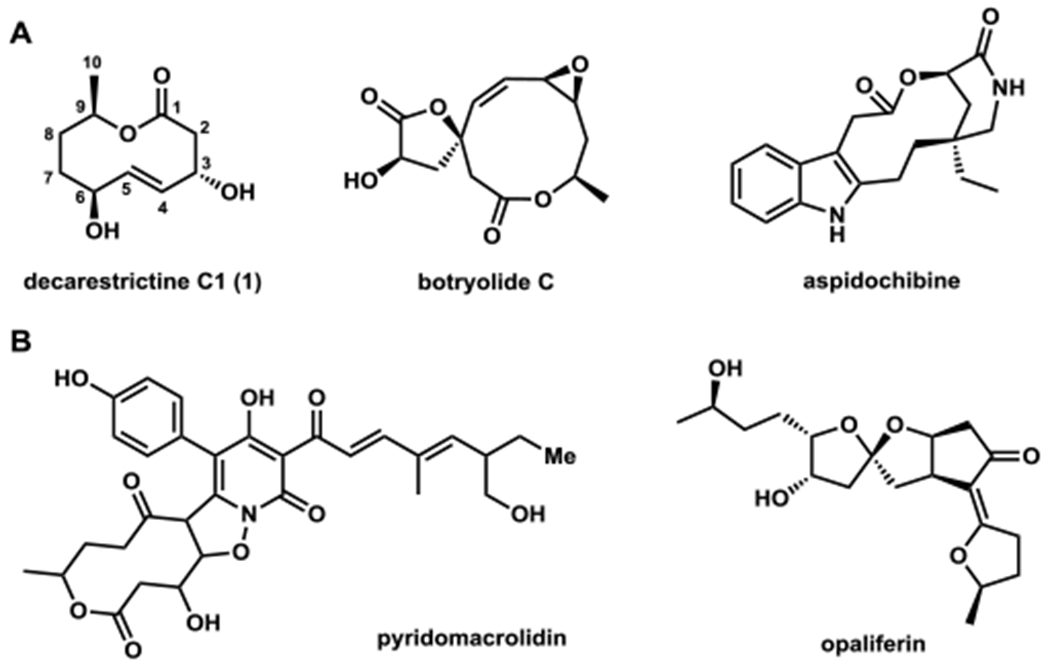

Toward this objective, we focused on the biosynthesis of nonanolides by filamentous fungi. Compounds in this family contain a 10-membered lactone core (Figure 1A). Decarestrictine C1 (1) isolated from Penicillium simplicissimum and other fungi,12 is a representative molecule. Lactone 1 shows inhibitory effects on cholesterol biosynthesis, and contains an (E)-alkene at C4 and C5 that is flanked by two allylic alcohols. The 10-membered ring with multiple chiral substituents has attracted several total synthesis efforts.13 Nonanolides such as 1 are also proposed to be biosynthetic precursors for pyridomacrolidin14 and opaliferin15 (Figure 1B). Biosynthetically, the 10-membered ring in 1 is proposed to derive from a polyketide pathway:16 one would expect a highly-reducing polyketide synthase (HRPKS) to iteratively assemble the enzyme-bound linear polyketide, which is lactonized by a TE.17 Additional oxidoreductases complete the biosynthesis. The proposed TE therefore represents a potential medium-ring lactonization biocatalyst.

Figure 1.

Nonanolides and related natural products. (A) Compounds with 10-membered lactones. (B) Compounds that are proposed to be derived from 10-membered lactones.

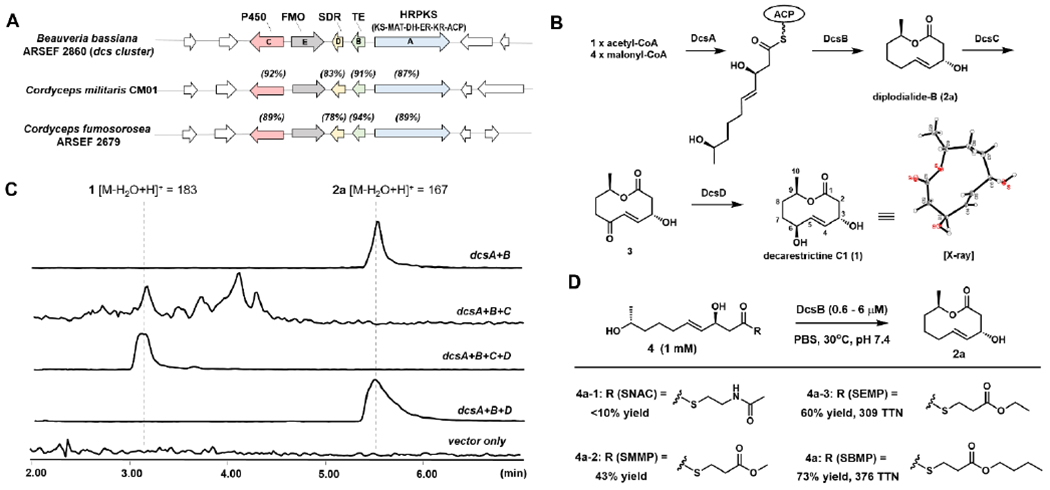

Our search for the biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) that encodes the enzymes for 1 started with genome scanning of Beauveria bassiana ARSEF 2860;18 a related fungus B. bassiana EPF-5 was reported to produce pyridomacrolidin.14 Guided by other fungal macrolide BGCs,17c, 17d we identified one BGC (dcs, Figure 2A) that encodes an HRPKS (DcsA), a TE (DcsB), a P450 (DcsC), a short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR, DcsD) and a flavin-dependent monooxygenase (FMO, DcsE) (Table S1). Close homologues of this five-gene cassette are found in two other fungi, including Cordyceps species that are known producers of nonanolides.19

Figure 2.

Fungal nonanolide biosynthesis. (A) The dcs and homologous biosynthetic gene clusters. The % sequence identities are shown in parenthesis; (B) Proposed biosynthetic pathway of 1. (C) LC-MS analysis of metabolites produced from expression of dcs genes in A. nidulans. (D) Assaying activity of DcsB using small molecule thioesters.

The functions of the dcs enzymes were examined through heterologous expression in Aspergillus nidulans A1145 (Figures 2C and S1).20 Coexpression of DcsA and DcsB led to the production of 2a (~ 250 mg/L), which was confirmed to be the 10-membered lactone diplodialide-B (Table S5, Figures S50–S54). This implies DcsA and DcsB together are sufficient to synthesize the nonanolide. Coexpression of the P450 DcsC led to disappearance of 2a, but no accumulation of new metabolites. Additional coexpression of the SDR DcsD led to formation of a new metabolite that has the same molecular weight as 1. NMR and X-ray crystallography characterization confirmed the compound to be identical to decarestricitine C1 (Figure 2B, Table S6, Figures S45–S49). As shown in Figure 2B, we propose DcsC oxidizes the allylic C6 position of 2a to the ketone 3, which can be modified or metabolized in vivo as a Michael acceptor. The SDR DcsD stereoselectively reduces the ketone to the C6 alcohol to form 1. The FMO DcsE is not required in the biosynthesis of 1, and its role is not evident from heterologous expression.

We synthesized a panel of thioesters (4, Figure 2D) that mimic the proposed HRPKS-tethered pentaketide, and assayed with recombinant DcsB (Figure S2). Thioesters with the natural acyl chain were prepared through hydrolysis of 2a followed by reacting with different thiols (Supporting Methods). As shown in Figure 2D and Table S4, Acyl-S-N-acetylcysteamine 4a-1 was a poor substrate and gave low yield of 2a. Using more lipophilic acyl thioesters, such as acyl-S-MMP 4a-2,21 acyl-S-EMP 4a-3, and acyl-S-BMP 4a led to significant increases in yield and total turnover numbers (TTNs). Lowering the enzyme loading to 0.5 μM led to maximum observed TTN of 1258 (Table S4) with 4a. The kinetic parameters of DcsB towards 4a was determined to be kcat = 11.5 min−1 and KM = 298 μM (Figure S3). Sequence comparison of DcsB to other TEs showed the presence of the catalytic triad, S114, H276 and D247, that performs catalysis in a well-established reaction mechanism (Figure S14).22 While the S114A mutant cannot be solubly obtained, both the S114T and the S114C mutants retained <5% of the catalytic activity using 4a as the substrate (Figure S2).

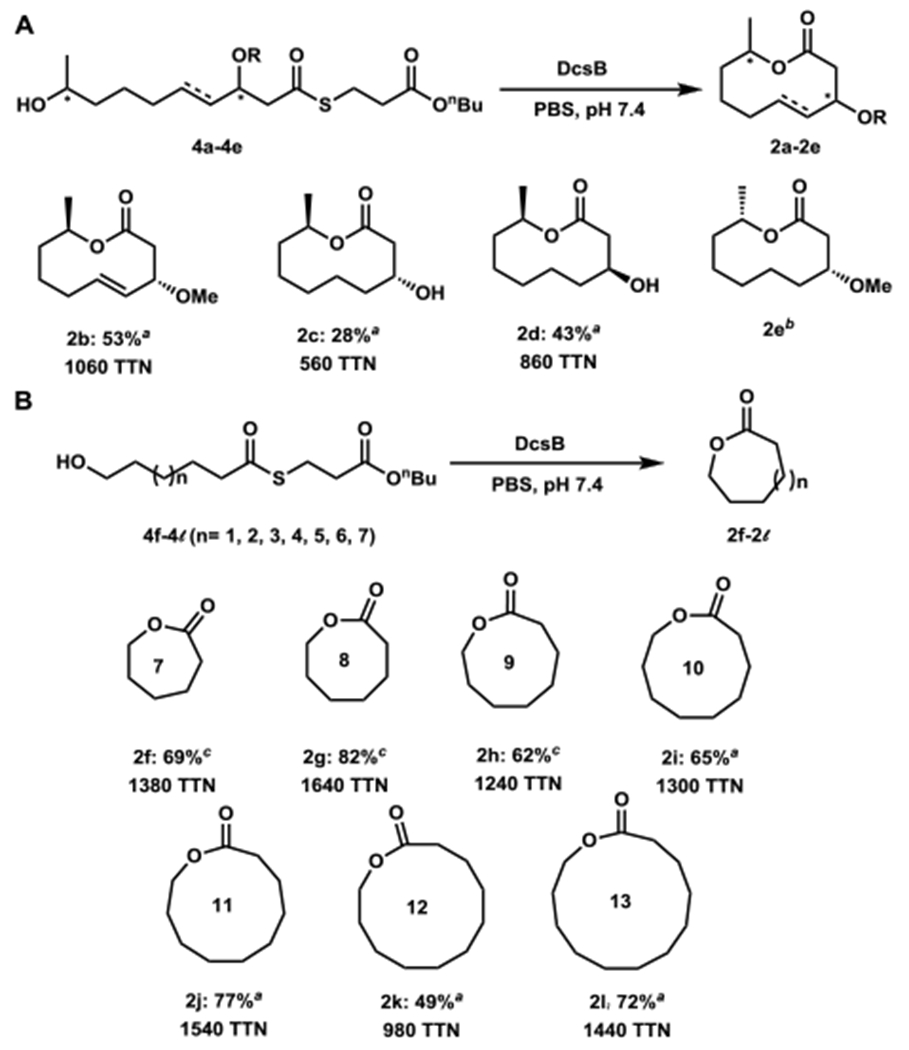

To examine how substitutions in the substrate affect cyclization, we synthesized modified pentaketide-S-BMP substrates 4b-4e by using semisynthetically modified 2a (Supporting methods). Products from the enzymatic reactions were isolated and characterized by NMR (Figures S55–S60). The C3-methoxy-containing substrate 4b was efficiently converted to the lactone 2b with 53% isolated yield (Figure 3A). The saturated pentaketide 4c was converted to lactone 2c, indicating that the olefin is not essential. The C3 epimer of 4c, 4d, was cyclized to 2d with 43% isolated yield, further indicating substitutions on the ring do not affect catalysis. In contrast, DcsB failed to lactonize substrate 4e containing an epimerized nucleophilic alcohol into 2e. Instead only the hydrolyzed byproduct was observed by LCMS analysis (Figure S5). This suggests that the proper spatial orientation of the nucleophile is required for attacking the Ser114-bound acyl chain in the lactonization reaction, in contrast to the stereotolerance of other macrolactonizing TE enzymes.17e

Figure 3.

Assaying the substrate promiscuity of DcsB. (A) Analogs 4b-4e used to probe functional group requirements; (B) simple alcohol-terminated substrates 4f-4l. a Isolated yield; b The cyclized product was not formed and only substrate hydrolysis was observed; c Yield determined by GC-MS analysis. Reaction conditions: 1 mM substrate, 0.5 μM DcsB except for 2k in which 2.4 μM DcsB was used.

We next explored the substrate tolerance of DcsB towards linear substrates of different sizes by using simplified acyl-S-BMP compounds 4f-4l (Figure 3B). These compounds, once cyclized, would afford lactones 2f-2l ranging in ring sizes from 7- to 13-membered. In cases where synthetic standards of the lactones were available such as in 2f-2h, formation of products and yields were measured from GCMS analysis (Figure S4). In other cases, all putative lactone products were purified and spectroscopically characterized (Figures S61–S72). Gratifyingly, all of the substrates can be cyclized using DcsB in yields ranging from 49% to 82%. Using DcsB, odd-membered lactones, which are rarely found in nature, can be readily accessed. These examples illustrate that DcsB has broad substrate scope and is a biocatalyst for constructing lactones of assorted ring-sizes.

We determined the crystal structure of DcsB by single anomalous diffraction at 1.56 Å resolution (PDB ID: 7D78; Figure S6 and Table S7). DcsB exists as a homodimer in the asymmetric unit, consistent with sedimentation velocity experiment results (Figure S7). DcsB possesses a canonical α/β-hydrolase fold with an eight-stranded β-sheet and a lid region inserted between β6 and β7 with three helices (αL1, αL2, αL3) (Figures 4A and S8). Although DcsB has less than 10% sequence identity to the well-characterized DEBS TE10 and Pik TE9a domains, the core regions have structural similarities with an RMSD of 2.5 Å and 2.7 Å, respectively (Figure S9). The catalytic triad is located in the loops of the core domain, and adopts the same relative conformations as in other TEs (Figure S9).

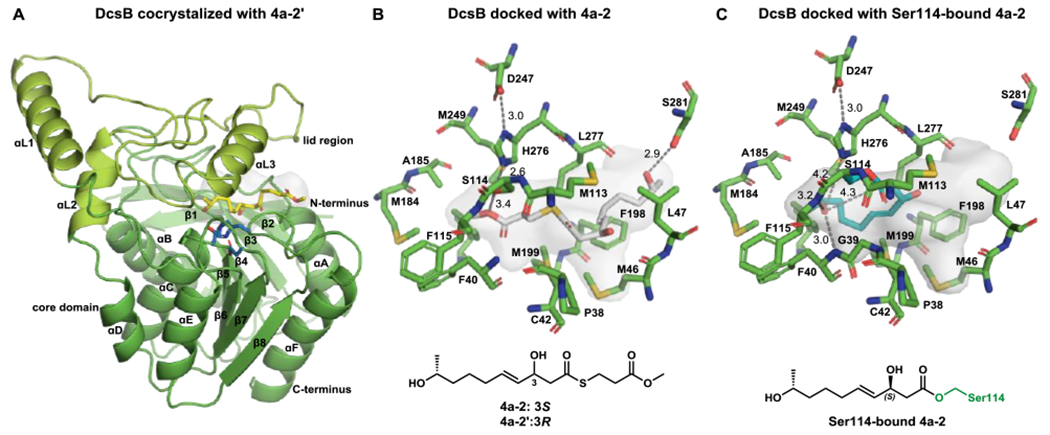

Figure 4.

Crystal structures of DcsB with bound and modeled substrate complexes. (A) Overall structure of DcsB-substrate analogue 4a-2’ complex. The active site catalytic triad residues (S114, H276, and D247) are shown in blue sticks while the substrate analog 4a-2’ is shown in yellow. The β-hydroxyl group in 4a-2’ is epimerized compared to the natural substrate 4a-2 and is bound in an unproductive conformation; (B) Active site of DcsB with docked substrate 4a-2 that is shown in grey sticks. The thioester is 5.6 Å from the catalytic S114 residue; (C) Covalent docking of the Ser114-bound acyl-intermediate of 4a-2 shown in teal.

We then attempted crystallization of DcsB with the substrate 4a-2. Unexpectedly, we obtained a 2.11 Å resolution structure of DcsB complexed with the substrate analogue 4a-2’, the 3R-epimer of 4a-2 (PDB ID: 7D79; Figures 4A and S10). Epimerization of the allylic and β-alcohol appears to take place nonenzymatically under crystallization conditions. The overall structure of DcsB-4a-2’ complex is essentially identical to the DcsB structure, with RMSD of 0.146 Å (Figure S10A). However, the conformation of 4a-2’ is a nonproductive one, as the nucleophilic alcohol that undergoes lactonization is hydrogen bonded to the catalytic Ser114. This pushes the thioester 7.9 Å away from the catalytic triad (Figure S10C) and gives a conformation that is unproductive towards lactonization. Nevertheless, the presence of 4a-2’ allowed us to visualize the active site cavity, which is an ~151 Å3 hydrophobic chamber calculated using POCASA.23 The active site is significantly different from those of the DEBS10 and Pik9a TEs, both of which have a substrate channel passing through the entire dimer (Figure S11). In these structures, the catalytic triad is located in the middle of channel to catalyze cyclization of the substrate that enters from one side and exits from the other side. The reaction chamber of DcsB is only open on one side, because the other side is blocked by the residues of I139 and F142 located in the loop between β6-αL1 connecting the lid and the TE core (Figure S11).

We computationally removed the 4a-2’ ligand and docked 4a-2 into the crystal structure (Figure 4B). 4a-2 docks into the enzyme in a conformation more consistent with catalysis. Now, the secondary alcohol is positioned at the entrance of active site and hydrogen bonds with Ser281. This conformation places the thioester 5.6 Å from the catalytic triad. We then performed covalent docking of the Ser114-bound acyl-intermediate (Figure 4C). The Ser114-bound acyl-intermediate adopts a folded conformation with the secondary alcohol ~ 4 Å from the catalytic His276 and the oxyester carbonyl where cyclization occurs. The backbone amides of F40 and F115 hydrogen bond to the alcohol and organize the substrate into a folded conformation ready for cyclization. This suggests that if the acyl-intermediate is formed, it will readily cyclize.

Quantum mechanical calculations on cyclization transition states with “theozyme” models of the active site further corroborated this mechanism; the computed transition states are very similar to the docked acyl-intermediate (Figure S12). The hydrogen bonding interactions between the substrate and F40 and F115 backbone amides distort the reactant towards a transition state-like geometry. Also of note is that the alkene and allylic alcohol do not form any stabilizing interactions with nearby residues, which is consistent with the fact that these substituents are not required for catalysis.

We performed covalent docking on Ser114-bound intermediates from the substrate 4f-4l and found that many structures produced a folded conformation as the best predicted docked pose (Figure S13). All structures except 4g produced folded conformations in the docked ensembles, but the lowest energy docked poses for substrates 4f, g, h, and i (n = 1–4) have extended conformations. The transannular strain associated with cyclizing these small to medium-ring substrates is unavoidable, but in the enzyme pocket these substrates can overcome this barrier by forming stabilized folded conformations. We propose that the broad substrate scope arises from the nature of the active site. One end of the substrate is bound to Ser114 and the other end hydrogen bonds with the backbone amides of F40 and F115. Positioning the termini in close proximity to each other with strong electrostatic interactions counteracts entropic and enthalpic barriers to cyclization. The active site residues that hug the alkyl chain are flexible methionines, bulky non-polar leucines and a phenylalanine that afford hydrophobic binding. These residues make up a large non-polar cavity with the Ser114-bound acyl-intermediate 4a-2. As the alkyl chain increases in length, the non-polar cavity can flex and accommodate the extra carbons. This general arrangement, in which the tails of the substrate are anchored by covalent modification and hydrogen bonds within a hydrophobic pocket, facilitates the promiscuity of DcsB.

In conclusion, we have identified the enzymes involved in forming the 10-membered lactone 1. DcsB is shown to have broad substrate promiscuity to form medium-ring lactones that are challenging to prepare chemically. DcsB adds to the collection of thioesterases discovered from biosynthetic pathways that are useful in chemoenzymatic preparation of lactones.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the NIH 1R35GM118056 to YT and GM124480 to KNH. We thank Dr. Yang Hai, Zhuan Zhang and Masao Ohashi for helpful discussion.

Footnotes

This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Experimental procedures, and spectroscopic data.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Molander GA Diverse Methods for Medium Ring Synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res 1998, 31, 603–609. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Illuminati G; Mandolini L Ring Closure Reactions of Bifunctional Chain Molecules. Acc. Chem. Res 1981, 14, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allinger NL; Tribble MT; Miller MA; Wetz DH Conformational analysis. LXIX. Improved force field for the calculation of the structures and energies of hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1971, 93, 1637–1648. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corey EJ; Nicolaou KC Efficient and mild lactonization method for the synthesis of macrolides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1974, 96, 5614–5616. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inanaga J; Hirata K; Saeki H; Katsuki T; Yamaguchi M A Rapid Esterification by Means of Mixed Anhydride and Its Application to Large-ring Lactonization. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn 1979, 52, 1989–1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurihara T; Nakajima Y; Mitsunobo O Synthesis of lactones and cycloalkanes. Cyclization of ω-hydroxy acids and ethyl α-cyano-ω-hydroxycarboxylates. Tetrahedron Lett. 1976, 17, 2455–2458. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Yet L, Metal-Mediated Synthesis of Medium-Sized Rings. Chem. Rev 2000, 100, 2963–3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Parenty A; Moreau X; Campagne JM Macrolactonizations in the total synthesis of natural products. Chem. Rev 2006, 106, 911–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Shiina I Total synthesis of natural 8- and 9-membered lactones: recent advancements in medium-sized ring formation. Chem. Rev 2007, 107, 239–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horsman ME; Hari TP; Boddy CN Polyketide synthase and non-ribosomal peptide synthetase thioesterase selectivity: logic gate or a victim of fate? Nat. Prod. Rep 2016, 33, 183–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Akey DL; Kittendorf JD; Giraldes JW; Fecik RA; Sherman DH; Smith JL Structural basis for macrolactonization by the pikromycin thioesterase. Nat. Chem. Biol 2006, 2, 537–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Giraldes JW; Akey DL; Kittendorf JD; Sherman DH; Smith JL; Fecik RA Structural and mechanistic insights into polyketide macrolactonization from polyketide-based affinity labels. Nat. Chem. Biol 2006, 2, 531–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Koch AA; Hansen DA; Shende VV; Furan LR; Houk KN; Jimenez-Oses G; Sherman DH A Single Active Site Mutation in the Pikromycin Thioesterase Generates a More Effective Macrocyclization Catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 13456–13465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsai SC; Miercke LJ; Krucinski J; Gokhale R; Chen JC; Foster PG; Cane DE; Khosla C; Stroud RM Crystal structure of the macrocycle-forming thioesterase domain of the erythromycin polyketide synthase: versatility from a unique substrate channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2001, 98, 14808–14813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The DEBS TE was shown to be able to form a eight-membered lactone when fused to an engineered PKS assembly line. See; Kao CM; McPherson M; McDaniel RM; Fu H; Cane; Khosla C Gain of Function Mutagenesis of the Erythromycin Polyketide Synthase. 2. Engineered Biosynthesis of an Eight-Membered Ring Tetraketide Lactone. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1997, 119. 11339–11340. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Gohrt A; Zeeck A; Hutter K; Kirsch R; Kluge H; Thiericke R Secondary metabolites by chemical screening. 9. Decarestrictines, a new family of inhibitors of cholesterol biosynthesis from Penicillium. II. Structure elucidation of the decarestrictines A to D. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1992, 45, 66–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Grabley S; Granzer E; Hutter K; Ludwig D; Mayer M; Thiericke R; Till G; Wink J; Philipps S; Zeeck A Secondary metabolites by chemical screening. 8. Decarestrictines, a new family of inhibitors of cholesterol biosynthesis from Penicillium. I. Strain description, fermentation, isolation and properties. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1992, 45, 56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Mohapatra DK; Sahoo G; Ramesh DK; Rao JS; Sastry GN Total Syntheses and Absolute Stereochemistry of Decarestrictines C1 and C2. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 5636–5639. [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Ferraz HMC; Bombonato FI; Longo LS Synthetic Approaches to Naturally Occurring Ten-Membered-Ring Lactones. Synthesis 2007, 21, 3261–3285. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sun P; Lu S; Ree TV; Krohn K; Li L; Zhang W Nonanolides of natural origin: structure, synthesis, and biological activity. Curr. Med. Chem 2012, 19, 3417–3455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Takahashi S; Kakinuma N; Uchida K; Hashimoto R; Yanagisawa T; Nakagawa A Pyridovericin and pyridomacrolidin: novel metabolites from entomopathogenic fungi, Beauveria bassiana. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1998, 51, 596–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Takahashi S; Uchida K; Kakinuma N; Hashimoto R; Yanagisawa T; Nakagawa A The structures of pyridovericin and pyridomacrolidin, new metabolites from the entomopathogenic fungus, Beauveria bassiana. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1998, 51, 1051–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grudniewska A; Hayashi S; Shimizu M; Kato M; Suenaga M; Imagawa H; Ito T; Asakawa Y; Ban S; Kumada T; Hashimoto T; Umeyama A Opaliferin, a new polyketide from cultures of entomopathogenic fungus Cordyceps sp. NBRC 106954. Org. Lett 2014, 16, 4695–4697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Cox RJ Polyketides, Proteins and Genes in Fungi: Programmed Nano-Machines Begin to Reveal Their Secrets. Org. Biomol. Chem 2007, 5, 2010–2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chooi YH; Tang Y Navigating the fungal polyketide chemical space: from genes to molecules. J. Org. Chem 2012, 77, 9933–9953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Zhou H; Zhan J; Watanabe K; Xie X; Tang Y A polyketide macrolactone synthase from the filamentous fungus Gibberella zeae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2008, 105, 6249–6254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zabala AO; Chooi YH; Choi MS; Lin HC; Tang Y Fungal polyketide synthase product chain-length control by partnering thiohydrolase. ACS Chem. Biol 2014, 9, 1576–1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Morishita Y; Aoki Y; Ito M; Hagiwara D; Torimaru K; Morita D; Kuroda T; Fukano H; Hoshino Y; Suzuki M; Taniguchi T; Mori K; Asai T Genome Mining-Based Discovery of Fungal Macrolides Modified by glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-Ethanolamine Phosphate Transferase Homologues. Org. Lett 2020, 22, 5876–5879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Morishita Y; Sonohara T; Taniguchi T; Adachi K; Fujita M; Asai T Synthetic-biology-based discovery of a fungal macrolide from Macrophomina phaseolina. Org. Biomol. Chem 2020, 18, 2813–2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Heberlig GW; Wirz M; Wang M; Boddy CN Resorcylic acid lactone biosynthesis relies on a stereotolerant macrocyclizing thioesterase. Org. Lett 2014, 16, 5858–5861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiao G; Ying SH; Zheng P; Wang ZL; Zhang S; Xie XQ; Shang Y; St Leger RJ; Zhao GP; Wang C; Feng MG Genomic perspectives on the evolution of fungal entomopathogenicity in Beauveria bassiana. Sci. Rep 2012, 2, 483–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rukachaisirikul V; Pramjit S; Pakawatchai C; Isaka M; Supothina S 10-membered macrolides from the insect pathogenic fungus Cordyceps militaris BCC 2816. J. Nat. Prod 2004, 67, 1953–1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu N; Hung YS; Gao SS; Hang L; Zou Y; Chooi YH; Tang Y Identification and Heterologous Production of a Benzoyl-Primed Tricarboxylic Acid Polyketide Intermediate from the Zaragozic Acid A Biosynthetic Pathway. Org. Lett 2017, 19, 3560–3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie X; Tang Y Efficient synthesis of simvastatin by use of whole-cell biocatalysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2007, 73, 2054–2060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rauwerdink A; Kazlauskas RJ How the Same Core Catalytic Machinery Catalyzes 17 Different Reactions: the Serine-Histidine-Aspartate Catalytic Triad of α/β-Hydrolase Fold Enzymes. ACS Catal 2015, 5, 6153–6176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu J; Zhou Y; Tanaka I; Yao M Roll: a new algorithm for the detection of protein pockets and cavities with a rolling probe sphere. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.