Abstract

A 52-year-old long-term user of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) presented with vaginal bleeding. Endometrial biopsy was performed and revealed endometrioid adenocarcinoma. The patient had a laparoscopic hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Endometrial cancer is rare in women with LNG-IUS as only seven cases have been published in the literature. Although scientific evidence shows LNG-IUS has a protective effect on the endometrium from developing cancer, our report highlights the importance of clinicians to be vigilant in cases of women with LNG-IUS who develop intermittent vaginal bleeding.

Keywords: obstetrics and gynaecology, cancer - see oncology, contraception, menopause (including HRT), reproductive medicine

Background

Endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma is rare in women using levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS). Therefore, when a patient with long-term usage of LNG-IUS for menorrhagia presents with intermittent vaginal bleeding, the level of suspicion for endometrial cancer usually can be very low, which may lead to a significant delay in further investigation, diagnosis and, as a result may delay in treatment that can be potentially life-saving.

Herein, we present a rare case of a patient with LNG-IUS who was diagnosed with endometrial cancer.

Case presentation

A female patient presented to a gynaecology clinic when she was 37 years of age, complaining of regular heavy menstrual bleeding. She had no medical conditions, such as obesity, diabetes or hypertension. In the past, she had two uncomplicated pregnancies, and both were spontaneous vaginal delivery at term. Her grandmother in her 50th and aunt at age of 70 years both on maternal side had uterine cancer. She had 3 yearly cervical cytology testing which was uneventful. Speculum and bimanual vaginal examination demonstrated no abnormalities of cervix, uterus and adnexa. The transvaginal scan was also unremarkable. Endometrial biopsy was not required at this stage as it was not part of routine investigation for menorrhagia. After counselling about menorrhagia treatment options, the patient chose to have IUS containing 52 mg levonorgestrel released at a rate of 20 μg/24 hours, which was inserted into the uterine cavity.

Six months later, the patient informed her gynaecologist that periods became lighter, and she was satisfied with the effect of LNG-IUS. The patient used the same type of LNG-IUS, which was replaced two times at the exact 5 yearly intervals in our hospital, and it was documented in her medical records. Her body mass index remained normal, and she had no medical conditions.

At 51 years of age, the patient developed intermittent vaginal bleeding with a backache. The patient saw her general practitioner (GP) because of irregular vaginal bleeds; the GP requested a serum Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) level and a transvaginal ultrasound scan. The FSH was 37.3 U/L. The transvaginal ultrasound scan showed an endometrial thickness of 8.3 mm; both ovaries had normal morphology and clear outline measuring 24 mm × 21 mm × 21 mm and 25 mm × 18 mm × 22 mm. Given the persistence of vaginal bleeding, the GP referred her to the gynaecology clinic for review and further management.

When the patient was reviewed in gynaecology outpatient clinic, the intermittent vaginal bleeding continued to be the main presenting complaint. On examination, there was a mild cystocele, hypertrophic cervix and a bulky anteverted uterus. The gynaecologist reviewing the patient assumed that menorrhagia symptoms were returning because of an expiring LNG-IUS even though the patient’s next IUS replacement was due only in 12 months. At this point, it was 14 years from the date when the patient started LNG-IUS treatment for menorrhagia. Since the patient had intermittent bleeding, the gynaecologist took an endometrial biopsy and replaced the LNG-IUS.

Investigations

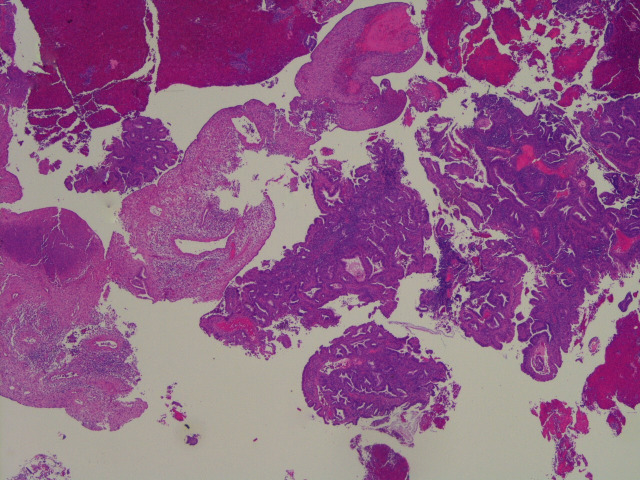

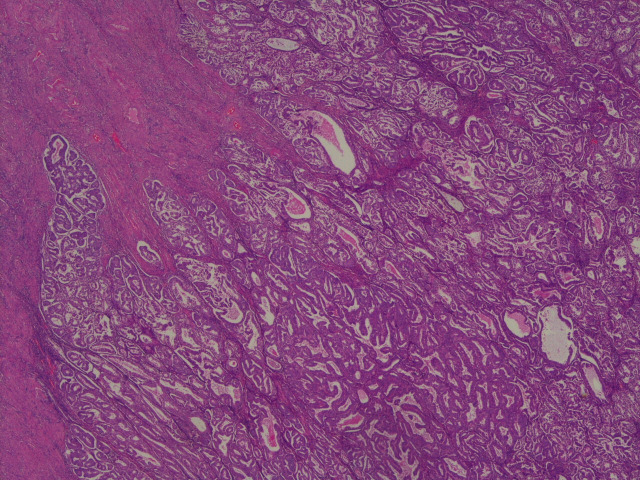

The endometrial biopsy showed complex endometrial hyperplasia with grade 1 endometroid adenocarcinoma (figure 1).

Figure 1.

A low-power H&E view of the original endometrial biopsy showing a mixture of endometrioid carcinoma and benign changes related to exogenous hormone administration (levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in this instance).

The patient had CT (chest, abdomen, pelvis) and MRI (pelvis and abdomen) scans as part of the local protocol to investigate patients with all types of endometrial cancer. Both scans were suspicious for endometrial malignancy with <50% of myometrial invasion and no evidence of local or distant metastasis.

Differential diagnosis

Treatment of menorrhagia was the main reason for the patient to use LNG-IUS for 14 years before being diagnosed with endometrial cancer. When irregular bleeding symptoms started and persisted, the cause for the bleeding was thought to be probable expulsion of the LNG-IUS. However, a speculum examination and transvaginal ultrasound scan confirmed the intrauterine position of the LNG-IUS.

Another suggestion was that vaginal bleeding was due to an expiring IUS, which might produce insufficient levonorgestrel levels and fail to achieve amenorrhoea which some women could experience after the IUS insertion. This suggestion was supported by the ultrasound scan showing the endometrial thickness of 8.4 mm and indicating the endometrium could be still active. Suspicion for endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer, in this case, was low because prolonged and continuous use of the LNG-IUS can prevent these conditions, and in some cases could even be used for their treatment. The menopausal status was also unclear due to previously diminished periods secondary to the LNG-IUS, which added some confusion to the differential diagnosis of the vaginal bleeding. The persistence of the symptoms and the patient’s age prompted to manage the patient as one with suspected endometrial malignancy. The endometrial biopsy was taken showing complex endometrial hyperplasia with endometrioid adenocarcinoma.

Treatment

The case was initially discussed at a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting at the local district general hospital (DGH), then at an MDT meeting with specialists in oncology gynaecology, histopathology, radiology at a leading regional cancer centre in London (UK). Based on the medical, radiological and histological information, the MDT members consensus at both sites was that the patient had a grade 1 endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the endometrium, probable tumour, node, metastases stage pT1a, The International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage IA.

The MDT members at the specialist meeting recommended a total laparoscopic hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy without lymph node dissection (LND). The advice was based on studies conducted by Janda et al and Walker et al1 2 : in women with stage 1 endometrial cancer, total laparoscopic hysterectomy compared with total abdominal hysterectomy resulted in similar disease-free and overall survival rates.

The specialist MDT meeting recommended not to perform LND because patients with a low-risk type of cancer such as endometroid type and <50% myometrial invasion had a very low probability of lymphadenopathy.3 Moreover, evidence from two randomised controlled trials conducted by Benedetti Panici et al, and Kitchener et al demonstrated that systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy in women with clinical stage 1, low-risk endometrial cancer had no added benefits in improving disease-free and overall survival rates.4 5 Such management strategy was also supported by guidance from the latest ESMO–ESGO–ESTRO (European Society for Medical Oncology- European Society of Gynaecological Oncology- European SociaTy for Radiotherapy and Oncology) consensus on endometrial cancer.6

In accordance with the endometrial cancer surgery policy for South-East London, grade 1 tumours are operated on at the local DGH treating the patient; therefore, the patient had a total laparoscopic hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy carried out at the DGH, with no complications. She was discharged home the following day after surgery.

Outcome and follow-up

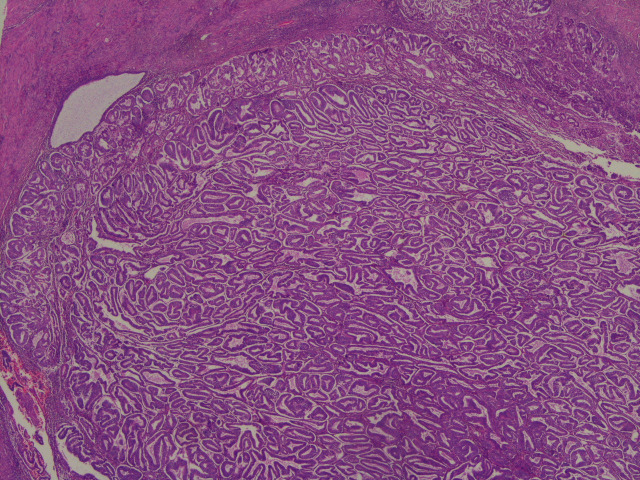

The reporting pathologist at the DGH provided the descriptions of the specimen. Microscopically, the sections taken from the uterus showed an endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the endometrium involving the inner half of myometrium (figures 2–7). The background endometrium had cystic atrophy and effect of progestogen administration. The histopathologist concluded it was endometrioid carcinoma pT1a FIGO grade 1A with no or <50% myometrial invasion, a 10 mm tumour-free distance to serosa, no lymphovascular invasion and no evidence of microscopic involvement of cervical stroma.

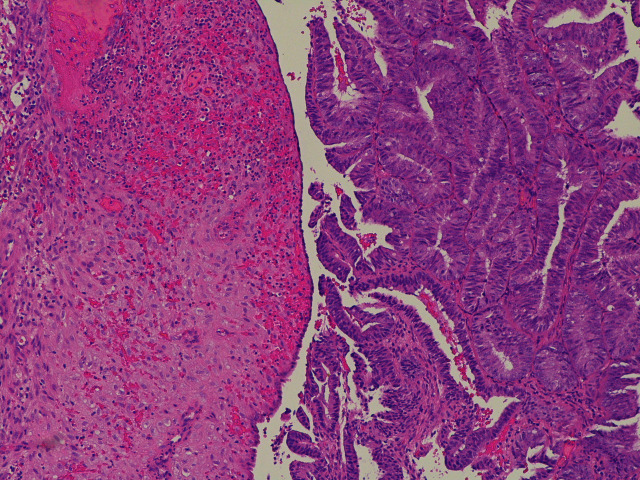

Figure 2.

A juxtaposition between the endometrioid adenocarcinoma on the right and the predecidual stroma induced by levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system on the left.

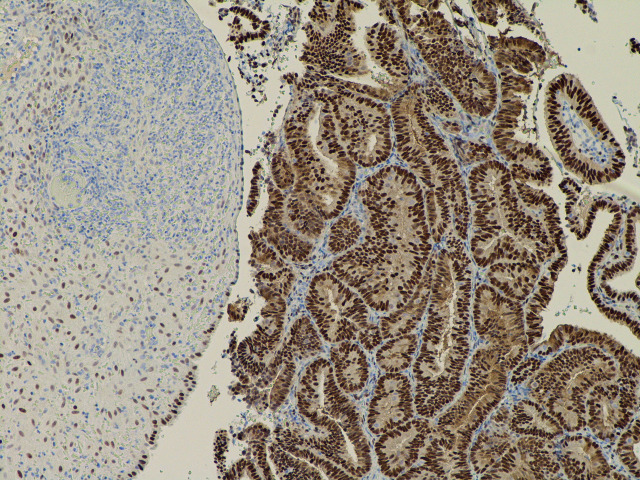

Figure 3.

The same field as in figure 2 and with the oestrogen receptor stain, which shows strong nuclear staining of the tumour cells (strongly positive).

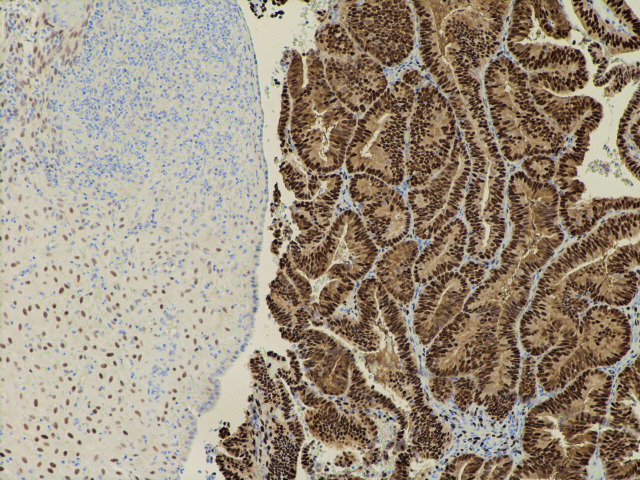

Figure 4.

The same field as in figure 2 showing similar strong expression of the progesterone receptor.

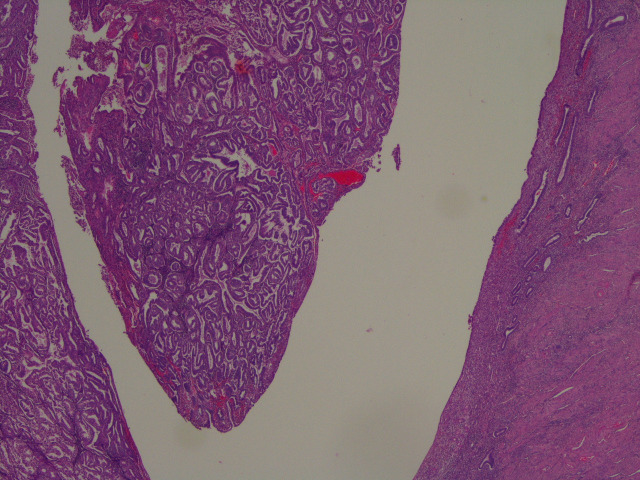

Figure 5.

The tumour invading the inner half of the myometrium (stage pT1a).

Figure 6.

An overview of the solid nature of the tumour filling part of the endometrial cavity.

Figure 7.

A contrast between the tumour and the uninvolved flat endometrium on the other side of the endometrial cavity.

The patient fully recovered after surgery and she was seen in the gynaecology outpatient clinic 4 months after the procedure as part of routine postoperative follow-up. After discussing with the patient, we agreed that we would follow her up on annual basis, focusing on the screening for asymptomatic pelvic or vaginal vault recurrence provided. One-year follow-up with pelvic MRI scan, vaginal vault cytology and examination, which is the standard practice in our hospital, showed no evidence of recurrence.

Given the patient family history of uterine cancer, the endometrial cancer was tested for mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency. The test showed patchy weak nuclear staining for mutL homologue 1 (MLH-1), postmeiotic segregation increased 2 (PMS-2) and mutS homologue 2 (MSH-2) with variable staining of background internal control. Although it was difficult to interpret, this was likely represented intact expression. Testing for MSH-6 showed complete loss of nuclear staining in the tumour area with preserved background internal control, which was interpreted as MSH-6-deficient tumour. In view of MMR result we referred the patient to our local research cancer centre to be tested for possible Lynch syndrome, which is an inherited mutation genes disorder associated with endometrial cancer. The result of the testing for Lynch syndrome was unavailable during writing the report.

Discussion

The LNG-IUS is used in gynaecological practice for contraception, treatment of menorrhagia and endometrial hyperplasia. The most common type of IUS used usually contains 52 mg of levonorgestrel delivered with a rate of 20 mcg/24 hours.7 LNG’s effect to suppress endometrial proliferation is used in women receiving hormone replacement therapy and, in patients treated with tamoxifen to prevent recurrence of breast cancer.8 There were also case reports where the LNG-IUS was used to treat women with early stages of endometrial cancer who wished to preserve their fertility,.9

The effect of the LNG-IUS on endometrium and uterus was extensively studied and found that continuous release of LNG into the uterine cavity causes significant changes in endometrial morphology and function. Common histological changes reported by Phillips et al were decidualisation of stroma (96%), atrophy of glands (87%), stromal inflammatory cell infiltrate with and without plasma cells (79% and 27%) and surface papillary formations (51%).10 Furthermore, morphological features associated with LNG-IUS use were stromal myxoid change (39%) and stromal haemosiderin deposition (32%). Glandular metaplasia (9%), stromal necrosis (7%), reactive atypia in surface glands (4%) and stromal calcifications (1%) were also observed but were less common.10

Development of endometrial cancer in long-term LNG-IUS users is very rare. Only seven cases were reported in the literature to date (table 1).11–16 Our patient is unique due to continuous LNG-IUS use (14 years) before she was diagnosed with endometrial cancer. Previously reported cases showed that the longest period LNG-IUS was used before the development of endometrial cancer was 4 years. The majority of women in case reports, including our case, were perimenopausal or postmenopausal (between 48 and 55 years old). Only two out of seven women were premenopausal (36 and 38 years of age). Most patients (four out of six) were multiparous, one was nulliparous, and in one case there was no information about parity. Analysis of case reports showed that the most common reason for LNG-IUS insertion was treating previously diagnosed menorrhagia. Interestingly, in all cases, reported patients had the same type of IUS, which contained 52 mg levonorgestrel-releasing 20 mcg of the hormone every 24 hours. This coincident could be because only one brand of LNG-IUS was available on the market to treat menorrhagia at that time.

Table 1.

Reported in literature cases of endometrial cancer in patients with LNG-IUS

| Author | Age of patient, years | Duration of LNG-IUS used |

Diagnosis | Endometrial biopsy before LNG-IUS use | Body mass index, kg/m2 | Parity | Presenting symptoms |

| Kuzel et al 11 | 52 | 46 months | Polyp endometrioid adenocarcinoma Grade 1 Stage1 |

No | 26.7 | Multiparous | Routine check-up USS: polyp 12×5 mm |

| Thomas and Briggs12 | 50 | Unknown | Endometrioid carcinoma Grade 1 Stage 1A |

No | Unknown | Persistent vaginal bleeding | |

| Abu et al 200613 | 36 | 5 months | Endometrioid adenocarcinoma Grade 2 Stage 1B |

No | Unknown | Irregular vaginal bleeding | |

| Flemming et al14 | 39 | 4 years | Endometrioid adenocarcinoma Grade 2 Stage 1B |

Benign non-secretory endometrium | 39.5 | Multiparous | Vaginal bleeding for 8 months |

| Ndumbe and Husemeyer 200615 | 55 | 4 years | Endometrioid adenocarcinoma Grade 2 Stage 1C |

No | Multiparous | Intermittent vaginal bleeding | |

| Jones et al 16 | 54 48 |

1 year 3 years |

Endometrial carcinoma Grade1 Stage 2B Endometrial adenocarcinoma Grade 2 Stage 3C |

Proliferative endometrium No |

Multiparous Nulliparous |

Irregular heavy vaginal bleeding |

LNG-IUS, levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system; USS, ultrasound scan.

In all seven patients with LNG-IUS reported in the literature who were diagnosed with endometrial cancer, the main presenting symptoms were prolonged or irregular vaginal bleeding. Although case reports stated that patients developed endometrial cancer after starting treatment with the LNG-IUS, the data should be interpreted with caution because only two patients had an endometrial biopsy before insertion of the LNG-IUS. In both cases, endometrial biopsies were reported as benign non-secretory or proliferative endometrium.

All patients had endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma. It is subtype I, hormone-receptor-positive, low-grade, diploid endometrial cancer with a generally good prognosis.17 A literature search failed to identify cases where patients with the LNG-IUS develop subtype II non-endometrioid cancer, described as hormone receptor negative, high-grade, and aneuploid. Subtype II cancer generally has a poor prognosis and a higher risk of metastasis.

Our case is also unique because the patient had no recognised risk factors for endometrial cancer, including exposure to endogenous and exogenous oestrogen levels, diabetes, obesity, early age at menarche, nulliparity, late menopause and use of tamoxifen.18 However, it is essential to remember that our patient had no endometrial biopsy before the insertion of the LNG-IUS.

The pathogenetic mechanism in the development of endometrial cancer in the presence of LNG-IUS is unknown. However, the most plausible mechanism could be that women might initially develop endometrial hyperplasia, causing excessive menstrual bleeding, then hyperplasia gradually progresses to endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma, even in the presence of the LNG-IUS. The latest evidence of molecular profiling can support this theory. Some endometrial cancers can be caused by microsatellite instability, which is the result of non-functioning of the DNA MMR system, described as a high frequency of frameshift mutations in microsatellite DNA.19 An example of this could be germline mutations in either of the MMR genes such as MLH-1, MSH-2, MSH-6 and PMS-2, leading to Lynch syndrome which is present in up to 2%–5% of patients with uterine cancer.20 Lynch syndrome is inherited by autosomal dominant mutation-promoting colon, endometrial and ovarian tumours. Similarly, mutations of PTEN, PIK3CA, KRAS, BRAF and POLE genes also can be associated with endometrial cancer,20 21 which could be an aetiological factor in the pathogenic mechanism of endometroid adenocarcinoma in women using the LNG-IUS.

Although LNG-IUS can cause changes to the endometrium as described earlier, most evidence indicates that long-term use of the LNG-IUS is rather protective of malignancies. For instance, the LNG-IUS significantly decreases endometrial proliferation by promoting apoptosis of endometrial glands and stroma.22 The underlying molecular mechanism by which LNG-IUS causes atrophic change in endometrium can be associated with increased Fas antigen expression and decreased Bcl-2 protein expression. The Fas antigen is a mediator of apoptotic signal in the Fas/Fas ligand system responsible for early apoptosis, whereas Bcl-2 protein promotes survival of cells in the endometrium.23 24 The LNG-IUS can also suppress angiogenesis in endometrium by decreasing expression of vascular endothelial growth factor, which is required for rapid endothelial proliferation and spiral arterioles coiling,.25

Further evidence indicating LNG-IUS protective properties against endometrial cancer and other malignancies was a large retrospective cohort study that compared rates of various cancers between users and non-users of the LNG-IUS for treatment of menorrhagia.26 The LNG-IUS users had a lower standardised incidence ratio of endometrial adenocarcinoma which was 0.50 (95% CI: 0.35 to 0.70) after the IUS was used the first time and 0.25 (95% CI: 0.05 to 0.73) after its use was extended for a second time. Also, there was a reduction in the incidence of pancreatic cancer (95% CI: 0.28 to 0.81), ovarian cancer (95% CI: 0.45 to 0.76) and lung cancer (95% CI: 0.49 to 0.91). However, breast cancer’s standardised incidence ratio was higher than expected in LNG-IUS users (95% CI: 1.13 to 1.25). The authors concluded that the LNG-IUS has a protective effect against endometrial transformation leading to malignancy.

The standard practice to diagnose an endometrial cancer is endometrial biopsy. MRI scan is a first-line image method used for assessment and staging of endometrial cancer. MRI is chosen over CT scan based on the systematic review of 18 studies conducted by Selman et al, which found that MRI and sentinel node biopsy were the most accurate tests in assessing lymph nodes' status in women with endometrial cancer.27 Also, MRI is superior to CT scan in terms of radiation risk.

Treatment for FIGO stage I with grade 1 endometrioid adenocarcinoma is a surgery which can be limited to hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.28 However, in some cases further surgery or adjuvant treatment may be required, if histological grade on preoperative biopsy was underestimated.

In the UK, the traditional follow-up of gynaecological cancer has a similar pathway: clinical examination in secondary care outpatient clinics every 3 months for the first 3 years and annually for further 2 years. Because of a shortage of robust evidence concerning follow-up in women after surgery for endometroid endometrial adenocarcinoma, the British Gynaecological Cancer Society (BGCS) published guideline on the management of endometrial cancer, including advice on follow-up strategy.28 BGCS recommended adopting individualised follow-up with the package of care designed to screen for recurrence, side effects and consequences of treatment received, patients' choices. For instance, women with low risk of recurrence, which includes stage 1 of endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma, can have a limited number of infrequent visits within the first 2 years or can be discharged to patient-initiated follow-up.

In conclusion, endometroid endometrial adenocarcinoma is very rare in patients using the LNG-IUS to treat menorrhagia. In these cases, the aetiology of cancer could be due to mutation in MMR gene MSH-6 or undiagnosed endometrial hyperplasia. It is also possible that if the patient had endometrial hyperplasia, the LNG-IUS continuous use could have delayed its progression to cancer.

Patient’s perspective.

I felt that my diagnosis was delayed mainly at the stage of primary care where my vaginal bleeding was not taken seriously. Also, it was a delay between the start of the bleeding and my referral to the hospital. Since I never had an endometrial biopsy before and during treatment with Mirena coil for vaginal bleeding I felt frustration from unknowing if I had a pre-cancer condition in my uterus in the past and continuous use of Mirena prevented it progression to the cancer or if it was that using the coil in itself caused the change which led to development of the cancer.

Learning points.

Patients with irregular vaginal bleeding should have endometrial biopsy.

Endometrial cancer is very rare in patients with LNG-IUS.

A mismatch repair profile should be considered to exclude inherited mutation gene disorders.

Footnotes

Contributors: AS performed literature review and wrote the article. LH contributed to the intellectual content and edited the article. DC contributed to editing the article and selecting histology photomicrographs for it.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Janda M, Gebski V, Davies LC, et al. Effect of total laparoscopic hysterectomy vs total abdominal hysterectomy on disease-free survival among women with stage I endometrial cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;317:1224–33. 10.1001/jama.2017.2068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker JL, Piedmonte MR, Spirtos NM, et al. Recurrence and survival after random assignment to laparoscopy versus laparotomy for comprehensive surgical staging of uterine cancer: gynecologic Oncology Group LAP2 study. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:695–700. 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vargas R, Rauh-Hain JA, Clemmer J, et al. Tumor size, depth of invasion, and histologic grade as prognostic factors of lymph node involvement in endometrial cancer: a SEER analysis. Gynecol Oncol 2014;133:216–20. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benedetti Panici P, Basile S, Maneschi F, et al. Systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy vs. no lymphadenectomy in early-stage endometrial carcinoma: randomized clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:1707–16. 10.1093/jnci/djn397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5., Kitchener H, Swart AMC, et al. , ASTEC study group . Efficacy of systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (MRC ASTEC trial): a randomised study. Lancet 2009;373:125–36. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61766-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colombo N, Creutzberg C, Amant F, et al. ESMO-ESGO-ESTRO consensus conference on endometrial cancer: diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. The ESMO-ESGO-ESTRO endometrial consensus conference Working group. Annals of Oncology 2006;27:16–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luukkainen T, Lähteenmäki P, Toivonen J. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device. Ann Med 1990;22:85–90. 10.3109/07853899009147248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dominick S, Hickey M, Chin J, et al. Levonorgestrel intrauterine system for endometrial protection in women with breast cancer on adjuvant tamoxifen. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015:CD007245. 10.1002/14651858.CD007245.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhar KK, NeedhiRajan T, Koslowski M, et al. Is levonorgestrel intrauterine system effective for treatment of early endometrial cancer? report of four cases and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol 2005;97:924–7. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips V, Graham CT, Manek S, et al. The effects of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (Mirena coil) on endometrial morphology. J Clin Pathol 2003;56:305–7. 10.1136/jcp.56.4.305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuzel D, Mara M, Zizka Z, et al. Malignant endometrial polyp in woman with the levonorgestrel intrauterine system - a case report. Gynecol Endocrinol 2019;35:112–4. 10.1080/09513590.2018.1491028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas M, Briggs P. A case of endometrial carcinoma in a long-term Levonorgestrel Intrauterine System (LNG 52 mg-IUS) user. Post Reprod Health 2017;23:13–14. 10.1177/2053369117691201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abu J, Brown L, Ireland D. Endometrial adenocarcinoma following insertion of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (mirena) in a 36-year-old woman. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2006;16:1445–7. 10.1136/ijgc-00009577-200605000-00077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flemming R, Sathiyathasan S, Jackson A. Endometrioid adenocarcinoma after insertion of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2008;15:771–3. 10.1016/j.jmig.2008.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ndumbe FM, Husemeyer RP. Endometrial adenocarcinoma in association with a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena). J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2006;32:113–4. 10.1783/147118906776276143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones K, Georgiou M, Hyatt D, et al. Endometrial adenocarcinoma following the insertion of a Mirena IUCD. Gynecol Oncol 2002;87:216–8. 10.1006/gyno.2002.6817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morice P, Leary A, Creutzberg C, et al. Endometrial cancer. Lancet 2016;387:1094–108. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00130-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaaks R, Lukanova A, Kurzer MS. Obesity, endogenous hormones, and endometrial cancer risk: a synthetic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2002;11:1531–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) . Sog clinical practice statement: screening for Lynch syndrome in endometrial cancer. Chicago, IL: Society of Gynecologic Oncology, 2014. sgo.org/clinical-practice/guidelines/screening-for-lynch-syndrome-in-endometrial-cancer. (Accessed January 22, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 20., Kandoth C, Schultz N, et al. , Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network . Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature 2013;497:67–73. 10.1038/nature12113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El-Deiry WS, Goldberg RM, Lenz H-J, et al. The current state of molecular testing in the treatment of patients with solid tumors, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 2019;69:305–43. 10.3322/caac.21560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maruo T, Laoag-Fernandez JB, Pakarinen P, et al. Effects of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system on proliferation and apoptosis in the endometrium. Hum Reprod 2001;16:2103–8. 10.1093/humrep/16.10.2103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otsuki Y, Misaki O, Sugimoto O, et al. Cyclic Bcl-2 gene expression in human uterine endometrium during menstrual cycle. Lancet 1994;344:27–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)91051-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamashita H, Otsuki Y, Matsumoto K, et al. Fas ligand, Fas antigen and Bcl-2 expression in human endometrium during the menstrual cycle. Mol Hum Reprod 1999;5:358–64. 10.1093/molehr/5.4.358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laoag-Fernandez JB, Maruo T, Pakarinen P, et al. Effects of levonorgestrel-releasing intra-uterine system on the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and adrenomedullin in the endometrium in adenomyosis. Hum Reprod 2003;18:694–9. 10.1093/humrep/deg179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soini T, Hurskainen R, Grénman S, et al. Cancer risk in women using the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in Finland. Obstet Gynecol 2014;124:292–9. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Selman TJ, Mann CH, Zamora J, et al. A systematic review of tests for lymph node status in primary endometrial cancer. BMC Womens Health 2008;8:8. 10.1186/1472-6874-8-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sundar S, Balega J, Crosbie E, et al. BGCS uterine cancer guidelines: recommendations for practice. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2017;213:71–97. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]