Abstract

Recurrent aphthous ulcers are the most prevalent oral mucosal disease, but the subset major aphthous ulcer is a less frequent type. These ulcers are refractory, may persist for several weeks to months, and interfere with the normal state of health. The aetiology is multifactorial and so is the treatment. We present a case of an adolescent male patient reported with multiple oral ulcers. He developed three ulcers simultaneously and suffered for 10 months despite using topical medications prescribed by different dental practitioners. We executed a multidisciplinary treatment approach that resulted in a long-term disease-free state. The treatment methods followed in our case could be a successful model to implement by medical practitioners and oral physicians when the situation demands.

Keywords: dentistry and oral medicine, nutritional support, cognitive behavioural psychotherapy, medical management, mouth

Background

Aphthous ulcers are the recurrent, inflammatory mucosal lesions of oral mucosa that are frequently encountered by medical and dental practitioners.1 The aetiology of these localised ulcers is still unconfirmed and expected as multifactorial. Recurrent aphthous ulcer (RAU) is classified as minor, major and herpetiform based on their site, size, shape and number of ulcers.2 3

Major recurrent aphthous ulcers (major RAUs) comprise 10%–15% among the 2%–66% of the internationally reported RAU cases.4 In this report, we present a case of major RAUs resistant to topical medication and persisted over 10 months leading to emaciation and anxiousness in an adolescent patient. The multidisciplinary treatment approach and follow-up care are discussed.

Case presentation

A 19-year-old male patient presented with multiple painful ulcers in the oral cavity. History revealed that he had been having these ulcers for the past 10 months and first experienced on the cheek mucosa, and soon another ulcer appeared on the tongue. On enquiring about the previous occurrence of similar ulcers, he recalled the incidence of an ulcer at the back of the throat that was diagnosed as major aphthae in the ear, nose and throat (ENT) clinic 1 year before and was treated with systemic steroids (tablet prednisone 20 mg/day in four divided doses). When he was in the healing state after 2 months of steroid treatment, he developed mouth ulcers. The steroid therapy was tapered down in the following 4 weeks and the throat ulcers healed completely, but the mouth ulcers were persisting. The ENT surgeon explained the recurring nature of the lesion and advised him to consult a dental practitioner to treat the mouth ulcers. Different dental practitioners treated him in the 10 months and prescribed a variety of topical medications including 0.1% triamcinolone oral paste and amlexanox 5% oral paste but had no relief. The patient is otherwise healthy, and the family history was insignificant. His review of systems was unremarkable for cardiovascular, respiratory, neurologic, musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal and genitourinary disorders. On revealing the history, the patient claimed that he had no habits of using addictive substances including tobacco-related products. He insisted on the pain and eating difficulties that disturbed his routine dietary habits.

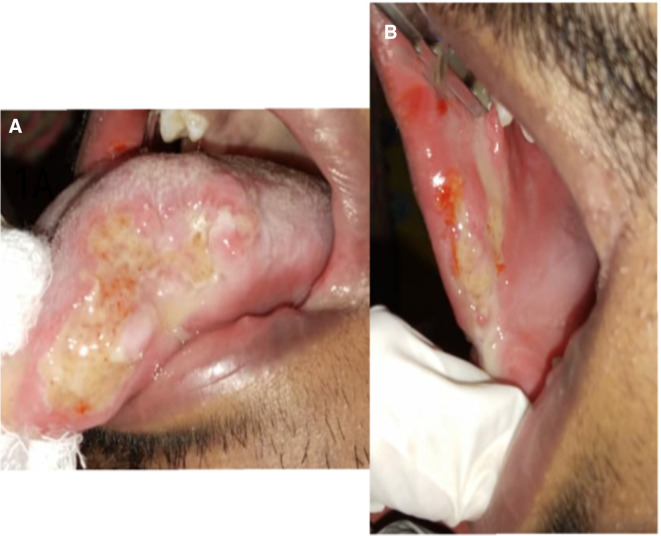

On examination, the vital signs were normal, and there were no signs of lymphadenopathy. The patient was 1.65 m tall and weighs 49 kg. His body mass index is 17.98 kg/m2. Intraoral examination revealed two ulcers on the right buccal mucosa, measuring approximately 2 and 2.5 cm, respectively, and another ulcer on the left lateral border of the anterior tongue, measuring 3 cm (figure 1A, B). The ulcers had erythematous borders and a non-indurated base. The floor was covered with a yellow slough, and there was no bleeding or pus discharge. Severe pain was elicited during palpation. There was no cervical lymphadenopathy and no signs of pallor, clubbing of fingers and pedal oedema.

Figure 1.

(A, B) Giant ulcers on the tongue and buccal mucosa.

Investigations

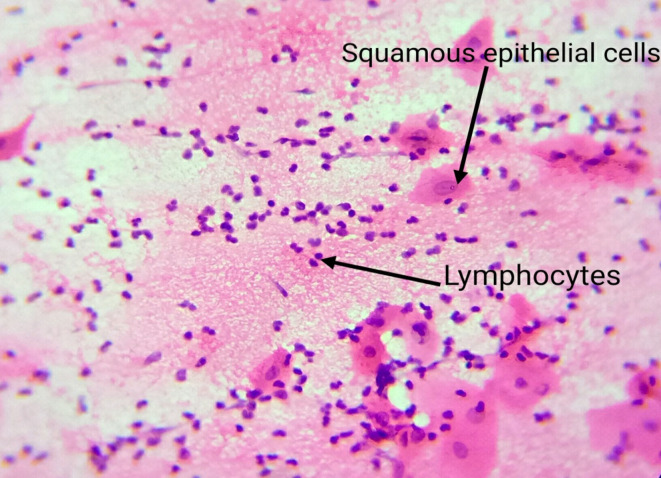

Exfoliative cytology was performed and subsequently advised complete blood count (CBC) and Mantoux test. The CBC was normal except for the haemoglobin level that was 11 g/L, and the peripheral smear report was normochromic and normocytic. The Mantoux test result was negative. Exfoliative cytology revealed squamous epithelial cells with atypia (nucleomegaly) and plenty of chronic inflammatory cells (figure 2). The above findings cued us to consider recurrent major aphthous ulcer as our working diagnosis.

Figure 2.

Exfoliative cytology findings of squamous epithelial cells and abundant lymphocytes.

Differential diagnosis

The other probabilities for the ‘aphthous ulcer-like oral lesions’ include Crohn’s disease, coeliac disease, tuberculosis ulcer, bullous autoimmune disorders and pernicious anaemia.

Crohn’s disease5 6 is a genetic disorder characterised by defects in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) mucosal immunity and intestinal epithelial barrier function, leading to an adverse inflammatory response to intestinal microbes. It exhibits a bimodal age distribution; the first incident at early adulthood and the second incident at 50–70 years of age. The symptoms include multiple chronic oral ulcers, fever, fatigue, abdominal pain and cramps, loss of appetite and weight loss. The oral ulcers are linear and superficial, resembling minor aphthous ulcers, commonly involving the labial and buccal mucosa, vestibular sulcus and soft palate.6 7 The histopathological finding of the oral ulcer reveals few focal inflammatory cells and non-caseating granulomas with scattered eosinophils in contrast with the abundant chronic inflammatory cells in RAUs.7

Coeliac disease (CD) is an autoimmune disorder caused by gluten intolerance. Aphthous-like oral ulcers are a well-recognised component besides the malabsorption syndrome with chronic diarrhoea, weight loss, weakness, anaemia, osteopenia or osteoporosis, and an array of neurological symptoms like headache, paresthesia, anxiety and depression.8 The oral ulcers may be small and multiple or large and single, round or ovoid with an erythematous halo, might be the initial symptom before the onset of other symptoms hence considered as a ‘risk indicator’ for coeliac disease.9 A gluten-free diet plan will help in the remission of oral lesions in these patients.

Tuberculosis ulcer is an oral form of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection that occurs because of autoinfection from sputum, or because of haematogenous or lymphatic transmission. Although rare, non-specific oral findings are associated with 0.05%–0.5% of total patients with tuberculosis.10 Painful ulcer commonly on the dorsal surface but sometimes on the ventral aspect of tongue, buccal mucosa, hard palate and gingiva usually accompanied with cervical lymphadenopathy is the clinical picture.11 The tuberculous ulcers are usually single, but sometimes multiple ulcers may also occur. They appear as superficial or deep oval lesions with undermined margins and indurated base, and with yellow exudate covering the surface. These altering presentations make it difficult to diagnose when the oral ulcer is the sole form of the disease. The confirmatory diagnosis requires the histopathological findings and Mantoux test report.10 12

Autoimmune blistering diseases are chronic inflammatory disorders caused by autoantibodies generated against structural proteins of the desmosomes and hemidesmosomes in the skin and mucosa, leading to intraepithelial or subepithelial blistering. The oral mucosa is involved in pemphigus vulgaris (PV), mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) and paraneoplastic pemphigus. They predominantly occur in middle or older age group individuals. The clinical presentation is heterogeneous and present with erythema and blisters leading to chronic erosions and ulcers on the oral mucosa causing pain, dysphagia and foetor.13 Extragingival ulcers in MMP have a gradual onset with acute exacerbations and remissions and heal with scar formation.14 Diagnosis is made based on the clinical, histopathological and immunopathological reports.13 14

Pernicious anaemia is the manifestation of vitamin B12 malabsorption and may present with multiple, small, shallow oral ulcers which mimic aphthous ulcerations. Pale mucosa, papillary atrophy and glossitis, and erythema on the tongue borders are the signs, and generalised sore/burning mouth, reduced taste sensation, weakness and paraesthesia of the extremities are the associated symptoms.15 16 Stomatitis, glossitis and linear ulceration on the tongue may occur as an initial manifestation because of the altered metabolism of epithelial cells in vitamin B12 deficiency.

We ruled out these possibilities based on the absence of other associated findings, age of onset, clinical presentation, a negative result of the Monteux test and the cytology report of chronic inflammatory cells.

Treatment

A team of specialists developed a multidisciplinary treatment plan in our tertiary care hospital set-up. In our oral medicine clinic, we started levamisole hydrochloride 150 mg (once per day for 3 consecutive days in a week for 3 successive weeks. Granulocyte count was monitored during this period). To overcome the possibility of super-added infection, we prescribed alcohol-free antimicrobial mouth rinse (Oral-B Pro-Expert Elixir Protection Professional) two times per day. As the patient was in the underweight group, as per the ICMR (Indian Council of Medical Research) guidelines, we have taken the support of the nutrition and dietician’s service to calculate the nutritional requirements and assist him towards health-promoting diets. The intervention of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) with the help of a psychotherapist handled the chronic pain-associated anxiety.

Outcome and follow-up

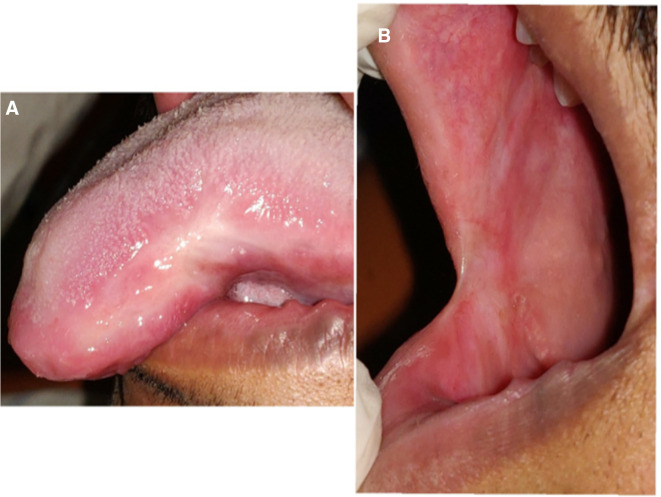

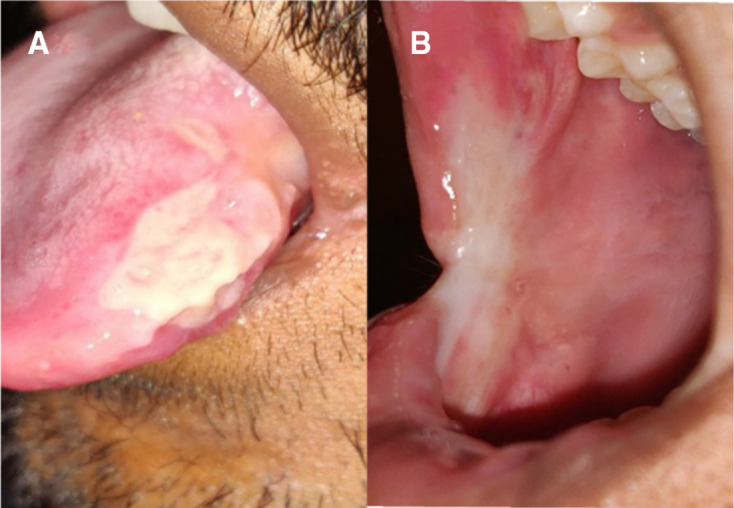

The follow-up visits were planned every week. At the end of the first week, we could not appreciate any signs of healing, but the patient expressed that the pain and discomfort had slightly reduced (Visual Analogue Scale score 7). The patient was satisfied with the response compared with the previous therapies. The levamisole, along with supportive care and weekly follow-up, was continued and there was a noticeable prognosis in each visit. In the fourth week of the review, the buccal mucosa was completely healed, leaving a scar at the ulcer site. On the tongue, there was evidence of a shrunken ulcer with keratinisation and no signs of inflammation (figure 3A, B). Our next focus was to treat the scar by prescribing medium potency topical corticosteroid, triamcinolone acetonide 0.1%, three times per day. The patient did not have a significant improvement in the initial 2 weeks; hence, we changed to high potent clobetasol propionate 0.5% topical application three times a day. At the end of a week’s application, we noted a very fine reduction of the scar on the buccal mucosa (figure 4A, B). At this visit, the patient pointed to 0 in the VAS score. We discontinued the topical therapy and asked to continue the suggested nutritional care. We shifted to bimonthly telephonic consultation in the follow-up period and the patient remains ulcer-free 1 year since the healing. By the year end, we called him for an in-person review and performed a complete examination. The patient gained 2.4 kg in weight, oral mucosa is healthy and is highly satisfied with the ulcer-free life.

Figure 3.

(A, B) Fourth week review picture showing completely healed ulcer, leaving a scar on the buccal mucosa and a shrunken ulcer with keratinisation on the tongue with no signs of inflammation.

Figure 4.

(A, B) Review of the patient after 1 week of topical application of clobetasol propionate revealing completely healed buccal mucosa and tongue.

Discussion

The present case has three ulcers developed in sequence, persistent over 10 months, all measuring more than 10 mm in size that caused severe pain and discomfort. The clinical findings (large, shallow ulcers with erythematous margins, floor covered with pseudomembranous slough and non-indurated base), the previous episode of a major aphthous ulcer on the throat and the exfoliative cytology findings assisted us to confirm the diagnosis of RAU. The eating difficulty because of the severe pain associated with the ulcerative lesion may affect the regular eating habits and induce hematinic deficiencies in some patients with RAU and so the present case.17 According to the WHO guidelines (2011), 11–12.9 g/dL haemoglobin level is grouped under mild anaemia for men (15 years of age and above) and is asymptomatic.18 Health-promoting diet and food fortifiers will satisfy the shortfalls and regulate the hematinic conditions together with better clinical outcomes.17 There are no specific histopathological tests to validate the clinical diagnosis of aphthous ulcers. The microscopic findings of this lesion will reveal squamous epithelial cells and chronic inflammatory cell infiltration that can rule out the other conditions.

RAU is suspected to have both exogenous (oral microbes, hypersensitivity response and psychological stress) and endogenous (genetic predilection and systemic factors) components. When the susceptible person is exposed to the exogenous components, the endogenous factors cause an immunological abnormality that triggers the ulcer development. The exact nature of immunological irregularity is not yet described but the neutrophil reactivation and hyper-reactivity, elevated concentration of the complements and cytokines, increased number of natural killer (NK) cells and B-lymphocytes, and disrupted CD4/CD8 ratio is recognised as a key factor.19 20

The treatment procedure for RAU varies extensively, and there is no promising guideline. The management is focused on providing symptomatic relief, reducing the healing period and decreasing the frequency of recurrence. Systemic intervention is shown for the chronic and severe form of RAU, whereas topical treatment is preferred for the RAU minor form (lesions less than 10 mm).21 We preferred low-dose levamisole for the present case because the drug acts as an immunopotentiator in short-term therapy.22 23 A double-blind study carried out to test the dose regimen of levamisole for RAU recommends 150 mg/day for 3 consecutive days every fortnight for 4 months to reduce the new episode, healing time and the lesion size.24 Levamisole provides the normal phagocytic activity of macrophages and neutrophils, regulates the T-cell activity, modulates the activity of human interferons (IFNs) and the serum levels of interleukin (IL-6 and IL-8), helps in the normalisation of CD4+/CD8+ cell ratio and increased level of serum immunoglobulin A (IgA) and M (IgM).25 This drug is effective in decreasing the size of the ulcer, pain, frequency of recurrence, duration of healing and the number of aphthous ulcers and produces fewer side effects than the other drugs.26 Being a broad-spectrum anti-helminthic drug, levamisole treats intestinal helminthiasis and slightly increases the haemoglobin level as well.27 The therapeutic effects of levamisole in treating RAU are differing among the published clinical trial results.22 27 28 The variation in the agreement is because of the study design with variation in terms of the type of aphthous ulcer, drug dose and duration of the therapy.

Systemic drugs used in the management of recurrent major aphthous ulcers other than levamisole are corticosteroids, dapsone, colchicine, azathioprine, thalidomide, pentoxifylline and low-dose interferon-α.29

Corticosteroids are the first-choice systemic treatment. Systemic corticosteroids provide symptomatic relief and fasten the healing of ulcers. But steroids do not interfere with the frequency of ulcers.24 Long-term use may increase the risk of secondary infection, gastrointestinal bleeding, weight gain, fluid retention, elevated blood pressure and increased blood glucose level.

Azathioprine is an immunosuppressive drug that belongs to the class of purine analogues. It is proven to be effective in treating complex aphthous stomatitis (Behcet’s disease).29 The side effects include bone marrow depression, leucopenia, toxic hepatitis, biliary stasis, GIT disturbances and secondary infections.

Dapsone therapy is preferred at 25 mg daily for 3 days, 50 mg daily for 3 days, 75 mg daily for 3 days and 100 mg daily for 1 week.30 Patients need to be monitored during dapsone treatment, with tests including complete blood cell count with a differential count, a reticulocyte count, liver and renal function tests, and urinalysis. The tests should be performed weekly for the first 4 weeks, then monthly for the next 4 months and thereafter once every 3 months.

Colchicine is the most commonly used drug at the dosage of 0.6 mg, three times a day for 1 year. Recurrence is frequently reported on colchicine therapy after the drug is discontinued.30

Thalidomide31 remains the most effective drug at doses of 100–300 mg/day in healing minor and major RAUs. Thalidomide inhibits the production of TNF and reduces its activity by accelerating the degradation of its messenger RNA. The teratogenicity, sedation and peripheral sensory neuropathy associated with thalidomide limit the usage of the drug.

Pentoxifylline’s benefit in the treatment of RAUs is limited.32 It may have a role in the treatment of patients unresponsive to other treatments, but cannot yet be recommended as a first-line treatment.

Treatment with a low dose of INF-α downregulates the infiltration of cells into peripheral lymph nodes and delayed-type hypersensitivity and effective in the complete or partial remission of RAUs within 1–4 months, however, maintenance therapy is needed for 6 months.31 The side effects reported include influenza-like symptoms, haematological toxicity, elevated transaminases, nausea and fatigue.

Research reports suggest that patients with RAU exhibit higher levels of anxiety.33 34 Stress affects the activity of lymphocytes, phagocytes, cytokines and NK cells, and may trigger the ulcer episode frequently; thus, there is a high incidence of RAU in patients under stressful situations.35 CBT is a short-term remedy to improve the quality of life in anxiety patients by changing the patient’s thoughts, behaviours or both,36 and hence, we combined CBT in our management plan. This helped the patient to cope with the ulcer-related chronic symptoms during the healing period, manage emotions and preventing the relapse of the anxiety disorders.

The impact of diet and nutrition on the well-being of patients with RAU is proven. Diet rich in vitamin A, B and E, proteins,37 antioxidants and unsaturated fatty acids have a protective role against RAU pathogenesis and decreasing the ulcer frequency, whereas sweet, carbonated beverages and fried and spicy foods have a triggering effect on the oral mucosa to develop ulcers.38 Sweets and carbonated beverages lower the pH, and the reduced oral pH trigger the onset of aphthous stomatitis.39 The role of diet counselling may be a complementary treatment hence we included nutritional intervention in the treatment scheme.

The literature evidence to treat major RAU is extensive, but the therapy that supports complete remission and continual ulcer-free period is insignificant. Recurrence of the ulcer after cessation of the medication is reported between 1 and 6 months during the follow-up period when systemic medications are used.40 Staying a year ulcer-free condition is a fortunate outcome of the immunotherapy and lifestyle medication we used on an evidence-based approach satisfied the focus of treatment.

Learning points.

Major recurrent aphthous ulcer (RAU) cases are rare. A detailed history and complete clinical examination assisted with the microscopic findings of chronic inflammatory cells will help to rule out the ‘aphthous-like ulcers’ associated with many other conditions.

Systemic steroids are the protagonists in the treatment of major aphthous ulcers and provide symptomatic relief. Using immunomodulators as monotherapy for major RAU is proven in the literature. The non-serious adverse effects are reported to be less in single immunomodulatory therapy than the systemic steroids and the combination therapy of systemic steroids and immunomodulators.

Levamisole triggers the phagocytosis and regulatory T-lymphocytes, reinstates the altered immune responses. Hence, it is effective both in symptomatic relief and in altering the disease course.

Psychological effects provoke the repetitiveness of the aphthous ulcers. Cognitive–behavioural therapy educates the suffering person to become their own therapists, to treat the symptoms of anxiety and depression, and to take an active role in their treatment process.

Footnotes

Contributors: AW contributed to patient care, patient follow-up, manuscript conceptualisation and manuscript revision. MS is involved in patient care, patient follow-up, documentation of treatment details and manuscript writing. KA has contributed to patient management, literature search, manuscript writing and revision.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclaimer: Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Challacombe SJ, Alsahaf S, Tappuni A. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis: towards evidence-based treatment? Curr Oral Health Rep 2015;2:158–67. 10.1007/s40496-015-0054-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shashy RG, Ridley MB. Aphthous ulcers: a difficult clinical entity. Am J Otolaryngol 2000;21:389–93. 10.1053/ajot.2000.18872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bagán JV, Sanchis JM, Milián MA, et al. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. A study of the clinical characteristics of lesions in 93 cases. J Oral Pathol Med 1991;20:395–7. 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1991.tb00952.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burruano F, Tortorici S. [Major aphthous stomatitis (Sutton's disease): etiopathogenesis, histological and clinical aspects]. Minerva Stomatol 2000;49:41–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eckel A, Lee D, Deutsch G, et al. Oral manifestations as the first presenting sign of Crohn's disease in a pediatric patient. J Clin Exp Dent 2017;9:e934. 10.4317/jced.53914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katsanos KH, Torres J, Roda G, et al. Review article: non-malignant oral manifestations in inflammatory bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;42:40–60. 10.1111/apt.13217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woo VL. Oral manifestations of Crohn's disease: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dent 2015;2015:1–7. 10.1155/2015/830472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caio G, Volta U, Sapone A, et al. Celiac disease: a comprehensive current review. BMC Med 2019;17:1–20. 10.1186/s12916-019-1380-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sedghizadeh PP, Shuler CF, Allen CM, et al. Celiac disease and recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2002;94:474–8. 10.1067/moe.2002.127581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim S-Y, Byun J-S, Choi J-K, et al. A case report of a tongue ulcer presented as the first sign of occult tuberculosis. BMC Oral Health 2019;19:1–5. 10.1186/s12903-019-0764-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krawiecka E, Szponar E. Tuberculosis of the oral cavity: an uncommon but still a live issue. Postepy Dermatol Alergol 2015;32:302. 10.5114/pdia.2014.43284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carnelio S, Rodrigues G. Primary lingual tuberculosis: a case report with review of literature. J Oral Sci 2002;44:55–7. 10.2334/josnusd.44.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rashid H, Lamberts A, Diercks GFH, et al. Oral lesions in autoimmune bullous diseases: an overview of clinical characteristics and diagnostic algorithm. Am J Clin Dermatol 2019;20:847–61. 10.1007/s40257-019-00461-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carey B, Setterfield J. Mucous membrane pemphigoid and oral blistering diseases. Clin Exp Dermatol 2019;44:732–9. 10.1111/ced.13996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pontes HAR, Neto NC, Ferreira KB, et al. Oral manifestations of vitamin B12 deficiency: a case report. J Can Dent Assoc 2009;75:533–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim J, Kim M-J, Kho H-S. Oral manifestations in vitamin B12 deficiency patients with or without history of gastrectomy. BMC Oral Health 2016;16:1–9. 10.1186/s12903-016-0215-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu Y-C, Wu Y-H, Wang Y-P, et al. Hematinic deficiencies and anemia statuses in recurrent aphthous stomatitis patients with or without atrophic glossitis. J Formos Med Assoc 2016;115:1061–8. 10.1016/j.jfma.2016.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization . Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity, 2011. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/85839

- 19.Ślebioda Z, Szponar E, Kowalska A. Etiopathogenesis of recurrent aphthous stomatitis and the role of immunologic aspects: literature review. Arch Immunol Ther Exp 2014;62:205–15. 10.1007/s00005-013-0261-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewkowicz N, Lewkowicz P, Dzitko K, et al. Dysfunction of CD4+CD25high T regulatory cells in patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis. J Oral Pathol Med 2008;37:454–61. 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00661.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brocklehurst P, Tickle M, Glenny A-M, et al. Systemic interventions for recurrent aphthous stomatitis (mouth ulcers). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012;3. 10.1002/14651858.CD005411.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xue Y, Liu J, Zhao W. Research article a comparison of immunomodulatory monotherapy and combination therapy for recurrent aphthous stomatitis.

- 23.Picciani BLS, Silva-Junior GO, Barbirato DS, et al. Regression of major recurrent aphthous ulcerations using a combination of intralesional corticosteroids and levamisole: a case report. Clinics 2010;65:650–2. 10.1590/S1807-59322010000600015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer JD, Degraeve M, Clarysse J, et al. Levamisole in aphthous stomatitis: evaluation of three regimens. Br Med J 1977;1:671–4. 10.1136/bmj.1.6062.671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta P, Ashok L, Naik SR. Assessment of serum interleukin-8 as a sensitive serological marker in monitoring the therapeutic effect of levamisole in recurrent aphthous ulcers: a randomized control study. Indian J Dent Res 2014;25:284. 10.4103/0970-9290.138293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chamani G, Rad M, Zarei MR. Effect of levamisole on treatment of recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Oral Health and Oral Epidemiology 2016;5:70–7. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olson JA, Silverman S. Double-Blind study of levamisole therapy in recurrent aphthous stomatitis. J Oral Pathol Med 1978;7:393–9. 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1978.tb01608.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weckx LLM, Hirata CHW, Abreu MAMMde, et al. [Levamisole does not prevent lesions of recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial]. Rev Assoc Med Bras 2009;55:132–8. 10.1590/s0104-42302009000200014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gulani A, Nagpal J, Osmond C, et al. Effect of administration of intestinal anthelmintic drugs on haemoglobin: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2007;334:1095. 10.1136/bmj.39150.510475.AE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mimura MAM, Hirota SK, Sugaya NN, et al. Systemic treatment in severe cases of recurrent aphthous stomatitis: an open trial. Clinics 2009;64:193–8. 10.1590/S1807-59322009000300008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lynde CB, Bruce AJ, Rogers RS. Successful treatment of complex aphthosis with colchicine and dapsone. Arch Dermatol 2009;145:273–6. 10.1001/archdermatol.2008.591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Altenburg A, El-Haj N, Micheli C, et al. The treatment of chronic recurrent oral aphthous ulcers. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014;111:665. 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thornhill MH, Baccaglini L, Theaker E, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pentoxifylline for the treatment of recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Arch Dermatol 2007;143:463–70. 10.1001/archderm.143.4.463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCartan BE, Lamey PJ, Wallace AM. Salivary cortisol and anxiety in recurrent aphthous stomatitis. J Oral Pathol Med 1996;25:357–9. 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1996.tb00278.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soto Araya M, Rojas Alcayaga G, Esguep A. Association between psychological disorders and the presence of oral lichen planus, burning mouth syndrome and recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Med Oral 2004;9:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keenan AV, Spivakovksy S. Stress associated with onset of recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Evid Based Dent 2013;14:25. 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hofmann SG, Wu JQ, Boettcher H. Effect of cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders on quality of life: a meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 2014;82:375–91. 10.1037/a0035491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ogura M, Yamamoto T, Morita M, et al. A case-control study on food intake of patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2001;91:45–9. 10.1067/moe.2001.110414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Du Q, Ni S, Fu Y, et al. Analysis of dietary related factors of recurrent aphthous stomatitis among college students. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2018;2018:1–7. 10.1155/2018/2907812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pizzorno JE, Murray MT. Textbook of natural Medicine-E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2020. [Google Scholar]