Abstract

Objective

To evaluated the clinical outcomes of periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) patients with destination joint spacer compared with that of two‐stage revision.

Methods

From January 2006 to December 2017, data of PJI patients who underwent implantation with antibiotic‐impregnated cement spacers in our center due to chronic PJI were collected retrospectively. The diagnosis of PJI was based on the American Society for Musculoskeletal Infection (MSIS) criteria for PJI. One of the following must be met for diagnosis of PJI: a sinus tract communicating with the prosthesis; a pathogenis isolated by culture from two separate tissue or fluid samples obtained from the affected prosthetic joint; four of the following six criteria exist: (i) elevated ESR and CRP; (ii) elevate dsynovial fluid white blood cell (WBC) count; (iii) elevated synovial fluid neutrophil percentage (PMN%); (iv) presence of purulence in the affected joint; (v) isolation of a microorganism in one periprosthetic tissue or fluid culture; (vi) more than five neutrophilsper high‐power fields in five high‐power fields observed from histological analysis of periprosthetic tissue at ×400 magnification. Age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and laboratory test results were recorded. All patients were followed up regularly after surgery, the infection‐relief rates were recorded, Harris hip score (HHS) and knee society score (KSS) were used for functional evaluation, a Doppler ultrasonography of the lower limb veins was performed for complication evaluation. The infection‐relief rates and complications were compared between destination joint spacer group and two‐stage revision group.

Results

A total of 62 patients who were diagnosed with chronic PJI were enrolled, with an age of 65.13 ± 9.94 (39–88) years. There were 21 cases in the destination joint spacer group and 41 cases in the temporary spacer group, namely, two‐stage revision group (reimplantation of prosthesis after infection relief). The Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) in the destination joint spacer group was higher than that in the temporary spacer group, and this might be the primary reason for joint spacer retainment. As for infection‐relief rate, there were three cases of recurrent infection (14.29%) in the destination joint spacer group and four cases of recurrent infection (9.76%) in the two‐stage revision group, there were no significant differences with regard to infection‐relief rate. Moreover, there two patients who suffered from spacer fractures, three cases of dislocation, one case of a periarticular fracture, and three cases of deep venous thrombosis in destination joint spacer group, while there was only one case of periprosthetic hip joint fracture, one case of dislocation, and one patient suffered from deep venous thrombosis of the lower extremity in two‐stage revision. The incidence of complications in the destination joint spacer group was higher than that of two‐stage revision.

Conclusions

In summary, the present work showed that a destination joint spacer might be provided as a last resort for certain PJI patients due to similar infection‐relief rate compared with two‐stage revision.

Keywords: Complication, Destination joint spacer, Infection‐relief, Periprosthetic joint infection, Two‐stage revision

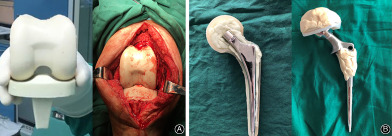

Diagram of destination joint spacer.

Introduction

Total joint arthroplasty is the main therapeutic method to reconstruct joint function in end‐stage osteoarthritis. With the advent of an aging society, there are more and more elderly people suffering with osteoarthritis, which leads to persistent and unbearable pain and poor daily mobility. Besides, end‐stage femoral head necrosis and developmental dysplasia of the hip might also lead to poor joint function and low life quality. Thus, they would turn to the last resort—total joint arthroplasty. Intertrochanteric fracture of femur in the elderly is another important reason for total joint arthroplasty. All these factors result in the increasing number of total joint arthroplasties. Total joint arthroplasty helps patients to reconstruct joint function, get back to normal life, and, most importantly, regain self‐confidence for life. However, there are many complications after total joint arthroplasty, including dislocation, periprosthetic fracture, lower extremity venous thrombosis, and so on, during which periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) is the most devastating complication.

It is widely acknowledged that periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) is a serious complication after total joint arthroplasty 1 . It has been reported that the incidence of PJI after primary arthroplasty is about 1% 2 . Although the incidence is not high, with an increasing number of patients receiving total joint arthroplasty, the total number of PJI cases is also increasing 3 . So far, there are many challenges in PJI management, the treatment of PJI often requires multiple revision surgeries and extensive periods of antibiotic administration, which results in substantial physical and mental pain in patients and a huge economic burden to society 4 , 5 . Thus, it is cardinal to investigate the optimal therapeutic methods of PJI.

According to Tsukayama classification, PJIs that occur within 4 weeks post‐operation are defined as acute PJIs, and most acute PJIs can be cured by debridement, antibiotics, and implant retention (DAIR), which is suitable for patients with stable and well‐fixed prosthesis, short duration of symptoms, good soft tissue, and no sinus tract. During DAIR operation, the infected necrotic tissue and suspected infected tissue should be removed thoroughly, then the joints are soaked in iodophor for half an hour, afterward, removal inserts are replaced. Sensitive antibiotics should be administrated post‐operation according to microbial culture results for an extensive period. DAIR is the best method for acute PJI, which has the advantages of less pain, less cost, and so on. However, chronic PJIs which occurring more than 4 weeks post‐operation usually require removal of the prosthesis and thorough debridement combined with systemic antibiotic treatment to eliminate the infection. At present, there are two kinds of revision surgeries for chronic PJI 6 : one‐stage revision and two‐stage revision. One‐stage revision requires removal of the prosthesis, thoroughly debridement, and removal of the suspected infected tissue, then joints were rinsed repeatedly with a large amount of saline and hydrogen peroxide, soaked in iodophor, and new prostheses were re‐implanted. Antibiotics were used intravenously for 2 weeks and oral administration for 6 weeks to 12 weeks positively based on microbial culture results. While two‐stage revision requires removal of the prosthesis and implantation of an antibiotic‐impregnated spacer, once the infection is controlled, the new prosthesis would be replanted again.

Currently, two‐stage revision is considered as the “gold standard” for chronic PJI treatment 7 , which requires removal of the prosthesis and implantation of an antibiotic‐impregnated spacer. The implantation of antibiotic‐impregnated spacers plays an important role in two‐stage revision, as it can: (i) release antibiotics directly into joint to control the infection locally; (ii) simultaneously maintain the joint space and reduce soft tissue contracture to facilitate reimplantation of the prosthesis; and (iii) maintain joint stability, which provides basic joint functions to meet the needs of daily life 8 , 9 , 10 . In clinical practice, some patients cannot tolerate reoperation after spacer implantation because of complicated underlying diseases, while some patients are satisfied with joint function after spacer implantation, so they refuse reimplantation of the prostheses 3 . In addition, some patients are unable to undergo prosthesis reimplantation due to poor economic conditions. These reasons might lead to a temporary spacer being retained for a long time, even a patient's whole life, namely, “destination joint spacer.” However, the clinical outcomes of these patients with destination joint spacers are unclear at present. We hypothesized that destination joint spacer could be used as a last resort for treatment of PJI without reimplanting a new prosthesis.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was: (i) to observe the clinical outcomes of PJI patients who with “destination joint spacer”; (ii) to evaluate the infection‐relief rate and complications of patients with “destination joint spacer”; (iii) to compare the infection‐relief rates and complications between destination joint spacer group and two‐stage revision group. In this study, a destination joint spacer was defined as a joint spacer that had been retained for more than 5 years at the last follow‐up, and these patients had no intention of undergoing prosthesis reimplantation.

Materials and Methods

Patient Selection

Approved by the institutional review board, from January 2006 to December 2017, data from PJI patients who underwent implantation with antibiotic‐impregnated cement spacers in our center due to chronic PJI were collected retrospectively.

Inclusion criteria: (i) Tsukayama type IV PJI cases with sufficient medical data; (ii) revision surgeries were performed with an antibiotic‐impregnated cement spacer and with regular follow‐up; (iii) the infection‐relief rates and complications between destination joint spacers group and two‐stage revision group were compared; (iv) the clinical outcomes of destination joint spacers group were recorded; (v) this study involved a single center, and PJI patients who underwent implantation with antibiotic‐impregnated cement spacers in our center were collected retrospectively and followed up regularly.

Exclusion criteria: (i) patients without regular follow‐up data or timely medication and with poor compliance; (ii) patients whose clinical outcomes were affected by infectious diseases in other parts of the body and patients who had immunosuppressive disease or malignant tumors; and (iii) patients with non‐PJI‐related death.

A diagnosis of PJI was made according to MSIS criteria for PJI. With the approval of the Ethics Committee of our hospital, 62 PJI cases were included with an average age of 65.13 ± 9.94 (39–88) years; there were 26 males and 36 females; 38 hips and 24 knees (summarized in Table 1). The mean follow‐up time was 45.12 ± 6.31 months.

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics

| Parameters | Destination joint spacers (n = 21) | Temporary spacers (n = 41) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 67.52 ± 11.61 | 63.9 ± 8.87 | 0.085 |

| Sex | 0.916 | ||

| Male | 9 | 17 | |

| Female | 12 | 24 | |

| Joints involved and type of spacers | |||

| Hip | 14 | 24 | 0.132 |

| Type I | 3 | 11 | |

| Type II | 11 | 13 | |

| Knee | 7 | 17 | 0.404 |

| Type I | 5 | 9 | |

| Type II | 2 | 8 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.23 ± 4.32 | 22.64 ± 3.26 | 0.083 |

| CCI (%) | 4.67 ± 1.88 | 2.15 ± 0.88 | <0.001 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 38.75 ± 23.11 | 35.42 ± 30.74 | 0.718 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 64.19 ± 33.18 | 76.49 ± 42.50 | 0.252 |

| SF‐WBC (×106/L) | 36783.24 ± 6737.19 | 23759.12 ± 7038.58 | 0.475 |

| SF‐PMN (%) | 84.16 ± 8.32 | 81.96 ± 8.16 | 0.324 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; CRP, C‐reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; PMN, polymorphonuclear; SF, synovial fluid; WBC, white blood cell count.

Process of Revision Surgery and Preparation of Joint Spacers

The revision surgeries were performed by the same medical team. Sufficient synovial fluid was obtained pre‐ and intraoperatively, and white blood cell (WBC) counts, polymorphonuclear (PMN) examinations, microbial cultures and drug sensitivity tests were routinely performed. At least five samples of periprosthetic tissues were obtained intraoperatively for microbial culture and intraoperative pathological examination. After removal of the prosthesis, debridement was performed using hydrogen peroxide, povidone iodine, and saline, and then antibiotic‐impregnated joint spacers were prepared (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Diagram of destination joint spacer 14 .

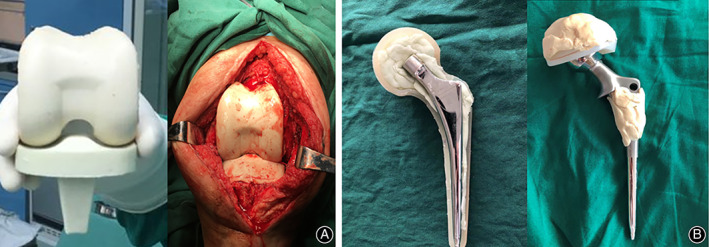

For hips, two types of joint spacers were used 11 , 12 . For type I, one to two Kirschner wires with a diameter of 5 mm that were bent to approximately 130° in advance were used as stents, which were placed in a silicone mold imitating the shape of the joint, embedded with antibiotic‐impregnated cement and molded under pressure (Fig. 2A,B). For type II, 105 mm femoral stem, 28 mm femoral head, and 32 mm femoral neck (CM‐CZ; AK Medical, Beijing, China) were used as scaffolds, which were embedded with antibiotic‐impregnated cement and molded under pressure (Fig. 2C,D). For knees, two types of spacers were also used 11 , 12 , 13 : for type I, an aseptic silicone mold imitating the joint shape was used, and a joint‐like spacer was made intraoperatively (Fig. 2E,F); for type II, the removed femoral end prosthesis was washed, soaked in povidone iodine solution, and resterilized, and the resterilized tibial prosthesis was used or replaced with a new polyethylene tibial component (Fig. 2G,H). The antibiotics used in the antibiotic‐impregnated joint spacer were selected according to the microbial culture and drug sensitivity test results. For those who had negative microbial culture results, vancomycin + ceftazidime (4.0 g vancomycin +4.0 g ceftazidime per 40 g bone cement) was empirically used. Patients who did not complete following prosthesis reimplantation were grouped into “destination joint spacers” group.

Fig. 2.

Two types of joint spacers used in this study for hips: type I (A, B): one to two Kirschner wires were bent to approximately 130° in advance and used as stents, which were placed in a silicone mold, embedded with antibiotic‐impregnated cement, and molded under pressure; type II (C, D), 105 mm femoral stem, 28 mm femoral head, and 32 mm femoral neck were used as scaffolds, embedded with antibiotic‐impregnated cement, and molded under pressure. Two types of joint spacers used in this study for knees: type I (E, F): an aseptic silicone mold imitating the joint shape was used, and a joint‐like spacer was made intraoperatively; type II (G, H): the removed femoral end prosthesis was washed, soaked in povidone iodine solution, and resterilized, and the resterilized tibial prosthesis was used or replaced with a new polyethylene tibial component.

For those who underwent prosthesis reimplantation, after infection elimination, the joint was incised along the original surgical incision, and joint spacers were thoroughly removed with necrotic granulation tissue, scar tissue, and cement debris. After washing with a large amount of hydrogen peroxide, povidone iodine, and saline, the new prosthesis was reimplanted. Those who have underwent prothesis reimplantation were grouped into “temporary spacers” or “two‐stage revision” group.

Follow‐up

The administration of antibiotics was based on the microbial culture and drug sensitivity test results, while those with negative microbial culture results were empirically treated with vancomycin. After receiving intravenous antibiotic treatment for 2 to 4 weeks, oral antibiotics were replaced. Patients were followed regularly post‐operation. The patient's age, sex, BMI, laboratory test results (such as CRP, ESR, synovial fluid WBC, and PMN%), Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), reasons for joint spacer retention, etc., were recorded. The diagnosis of infection recurrence was based on the symptoms, signs, laboratory tests, and images, which were judged by at least two orthopaedic experts and one infectious disease expert. Harris hip score (HHS) and Knee Society score (KSS) were used for functional evaluation, a Doppler ultrasonography of the lower limb veins was performed for all patient postoperatively for complication evaluation.

Evaluation Indexes

Harris Hip Score (HHS)

The HHS was used to evaluate postoperative recovery of hip function in an adult population. The HHS score system mainly includes four aspects: pain, function, absence of deformity, and range of motion. The score standard had a maximum of 100 points (best possible outcome). A total score <70 is considered a poor score, 70–80 fair, 80–90 is good, and 90–100 excellent.

Knee Society Score (KSS)

The KSS was used to evaluate postoperative recovery of knee based on clinical aspect and functional aspect. The clinical score includes the patient's subjective feeling of pain, range of motion, and stability of the joint; the functional score includes the ability to walk and the ability to go up and down the stairs. A total score <60 points is considered a poor score, 60–69 points is fair, 70–84 points is good, 85–100 points is excellent.

Visual Analogue Score (VAS)

The VAS was used to evaluate pain postoperatively. Use a ruler of about 10 cm, marked with 10 scales, with “0” and “10” at both ends. “0” indicates no pain and “10” represents the most severe pain that is unbearable. The patient marks the corresponding position on the ruler that represents the degree of pain. A score >8 points is considered as poor, 6–8 is fair, 3–6 is good, 0–2 is excellent.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0. The normal distribution data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and compared by Student's t‐test; while the abnormal distribution data were expressed as mean (interquartile range) and compared by Mann–Whitney U test. And the measurement data were expressed by rate and compared by chi‐square test. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

In the destination joint spacer group, 10 patients could not tolerate prosthesis reimplantation because of complicated underlying diseases, eight patients refused reimplantation due to being satisfied with function, and three patients were unable to undergo reimplantation due to economic and other factors. These patients were treated with antibiotics for 76 (48–96) days after joint spacer implantation. The mean age was 67.52 ± 11.61 (45–88) years, and there were nine males, 12 females, 14 hips (three cases of type I and 11 cases of type II) and seven knee joints (five cases of type I and 2 cases of type II). The mean preoperative CRP level was 38.75 ± 40.11 mg/L, the ESR was 64.19 ± 33.18 mm/1 h, the SF‐WBC count was 36783.24 ± 6737.19 L, the PMN% was 84.16% ±8.32%, and the CCI was 4.67% ±1.88%. There were 41 patients in the temporary spacer group, with a mean age of 63.9 ± 8.87 years. There were 17 males and 24 females, with 24 hips (11 cases of type I and 13 cases of type II) and 17 knee joints (nine cases of type I and eight cases of type II). The mean preoperative CRP level was 35.42 ± 30.74 mg/L, the ESR was 76.49 ± 42.50 mm/1 h, the SF‐WBC count was 23759.12 ± 7038.58 mL, and the PMN% was 81.96% ±8.16%. The mean CCI was 2.15% ±0.88%. The CCI of the destination joint spacer group was higher than that of the temporary joint spacer group, and there were no significant differences in other demographic characteristics between the two groups.

Comparison of the Infection‐Relief Rate and Efficacy

The eradication of infection was defined according to Delphi‐based international multidisciplinary consensus 15 . The comparisons of infection‐relief rates were shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Efficacy evaluation

| Parameters | Destination joint spacers (n = 21) | Two‐stage revision (n = 41) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrent infection | 3 (14.29%) | 4 (9.76%) | 0.687 |

| VAS preoperation | 4.76 ± 1.26 | 4.78 ± 1.44 | 0.960 |

| VAS postoperation | 2.23 ± 1.13 | 2.09 ± 0.80 | 0.574 |

| HHS preoperation | 39.71 ± 8.62 | 47.21 ± 11.42 | 0.56 |

| HHS postoperation | 50.64 ± 5.47 | 76.88 ± 10.70 | <0.001 |

| KSS preoperation | 37.71 ± 9.38 | 43.94 ± 7.89 | 0.11 |

| KSS postoperation | 47.14 ± 10.07 | 73.35 ± 8.57 | <0.001 |

| ROM (Knee) postoperation | 37.1° ± 6.5° | 127.3° ± 16.8° | <0.001 |

| ROM (Hip) postoperation | 61.58° ± 10.42° | 121.31° ± 5.27° | <0.001 |

| Death postoperation | 1 (4.76%) | 1(2.44%) | 0.624 |

Abbreviations: HHS: Harris hip score; KSS: knee society score; ROM: range of motion; VAS: visual analog scale pain score.

In the destination joint spacer group, there were three cases of recurrent infection (14.29%). In two of these cases, the joint spacers were removed, and antibiotic‐impregnated joint spacers were reimplanted after debridement; in another case, the joint spacer was removed with left exclusion after debridement. In the two‐stage revision group, there were four cases of recurrent infection (9.76%). Among the cases of recurrent infection, two patients underwent DAIR, and two patients underwent one‐stage revision. There was no significant difference in the infection‐relief rate between the two groups.

There were no significant differences in preoperative visual analog scale (VAS) score, Harris hip score (HHS), Knee Society score (KSS), or postoperative VSA between the two groups, but the postoperative HSS and KSS in the two‐stage revision group (76.88 ± 10.70 and 73.35 ± 8.57, respectively) were higher than those in the destination joint spacer group (50.64 ± 5.47 and 47.14 ± 10.07, respectively). One patient suffered from non‐PJI‐related death (death of severe liver cirrhosis after discharge) in the destination group, and one patient died after two‐stage revision; the cause of death was unknown.

Comparison of Complications

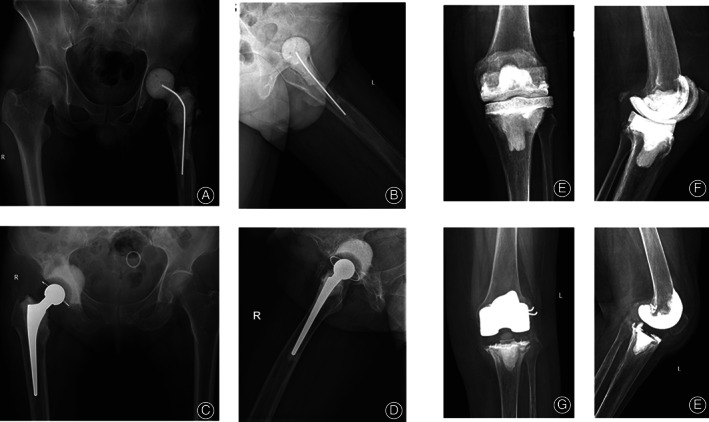

The comparison of complications (Fig. 3) between the two groups is listed in Table 3.

Fig. 3.

Representative radiographic images of complications in destination joint spacers group. (A) periarticular fracture; (B) spacer dislocation; (C) spacer fracture.

TABLE 3.

Incidence of complications (cases)

| Parameters | Destination joint spacers (n = 21) | Two‐stage revision (n = 41) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spacer fracture | 2 | N/A | N/A |

| Dislocation | 3 | 1 | 0.108 |

| Periarticular fracture | 1 | 1 | 0.339 |

| Deep venous thrombosis | 3 | 1 | 0.108 |

| Overall | 9 | 3 | 0.001 |

In the destination joint spacer group, two patients suffered from spacer fractures 3 and 5 years after spacer implantation (both were knees with type I spacers), respectively. Infection relief was confirmed after combining the clinical symptoms and signs with the laboratory test results, so the prostheses were reimplanted after debridement. There were three cases of dislocation (hip: two cases, both with type I spacers; knee: one case, type I spacer): two cases were successfully reduced, and one patient underwent surgery. There was one case of a periarticular fracture (hip, type I) and three cases of deep venous thrombosis, and these patients received oral anticoagulant therapy after joint spacer implantation.

Among the patients who underwent implantation of temporary joint spacers and prosthesis reimplantation, one patient suffered from a periprosthetic hip joint fracture after an accidental fall, so he received surgical treatment; one patient suffered from hip dislocation after reimplantation and was successfully reduced; and one patient suffered from deep venous thrombosis of the lower extremity. The total incidence of complications in the destination group was higher than that in the two‐stage revision group. Further analysis showed that in the destination joint spacer group, for hips (14 cases), there were three cases with type I spacers and two cases with dislocations (66.67%), and there were 11 cases with type II spacers (78.57%); however, there have been no complications so far, and there was a significant difference in the incidence of complications between the two types of hip spacers (P = 0.033). For knees (seven cases), there were five cases with type I spacers and two cases of spacer fractures with one case of dislocation, and the complication rate was 60%. While there were no complications in cases with type II spacers, there was no difference in the incidence of complications between the two types of knee spacers (P = 0.429).

Discussion

Application of Joint Spacers in PJI Treatment

PJI is a devastating complication after arthroplasty. At present, there are still many challenges in its diagnosis and treatment 16 . The surgical treatment of PJI includes DAIR and one‐ and two‐stage revision. Two‐stage revision is currently recognized as the “gold standard” for PJI treatment. Spacers play an important role in two‐stage revision to control infection. In clinical practice, some patients are unable to undergo reimplantation due to many factors, so joint spacers might be retained for a long time, even throughout the whole life of patients. However, the clinical outcomes of these patients are not clear. Thus, this study reported the clinical outcomes of patients with destination joint spacers in order to provide a clinical reference.

Compared with Two‐stage Revision, Destination Joint Spacers Have Similar Infection‐Relief Rate While Higher Complication Rate

A total of 62 PJI cases were included in this study, with 21 patients in the destination group and 41 patients in the temporary joint spacer group (who underwent prosthesis reimplantation after infection elimination). The CCI of the destination joint spacer group was higher than that of the temporary joint spacer group; this was a primary reason for retained spacer, followed by functional satisfaction. In terms of infection relief, the infection relief rate in the destination joint spacer group was 85.71%, while that in the two‐stage revision group was 90.24%. There was no significant difference in the infection relief rate between the two groups. In terms of complications, in the destination joint spacer group, there were two cases of spacer fracture, three cases of dislocation, and three cases of deep venous thrombosis after joint spacer implantation. However, in the two‐stage revision group, there was one case of periprosthetic fracture, one case of dislocation, and one case of deep venous thrombosis of the lower extremities. The overall incidence of complications in the destination group was higher than that in the two‐stage revision group, and the overall rate might be increased with longer follow‐up. This might be attributed to lower mechanical strength (fracture) 17 , mismatched spacer (dislocation), and decreased lower limb motion (deep venous thrombosis).

Destination Joint Spacers Could Be Used as a Last Resort for Some PJI Patients

Previously, some studies did not approve of the use of antibiotic‐impregnated joint spacers in the treatment of chronic PJI. They showed that spacers were new foreign materials on which bacteria could form new biofilms, affecting the administration of intravenous or systemic sensitive antibiotics and resulting in difficult‐to‐treat or relapsed infections 18 . However, similar to the study of Valencia et al. 19 and Petis et al. 3 , our study showed that the infection relief rate of destination joint spacers was similar to that of two‐stage revision, while the incidence of complications was higher than that of two‐stage revision. Therefore, for PJI patients who were unable to undergo reimplantation due to physical conditions or who did not plan to undergo reimplantation of the prosthesis, a spacer (type II spacer is recommended) provided an alternative for prosthesis implantation for infection control and daily activity.

Limitations

There were some limitations in this study. (i) This study was a single‐center study with a small sample size: there were only 21 patients with destination joint spacers and 42 patients with two‐stage revision. The sample size should be expanded in further research. (ii) In this study, PJI was diagnosed by MSIS criteria and there were various reasons for destination spacer, which might lead to selection bias to some extent. (iii) The follow‐up time was short, so it is necessary to prolong the follow‐up time in order to observe the clinical treatment outcomes of patients with destination spacers.

Conclusions

In summary, our study showed that the infection relief rate of destination spacers was similar to that of two‐stage revision, but the complications were higher than those of two‐stage revision (especially for type I spacers in this study). Due to the increasing number of PJIs, this study might provide a reference for treatment of PJI patients with complicated underlying diseases who are unable to tolerate multiple surgeries.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. All authors listed meet the authorship criteria according to the latest guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, and all authors are in agreement with the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81772251, 82072458), Joint Funds for the Innovation of Science and Technology, Fujian province (2019Y9136), the Middle‐aged Backbone Project of the Fujian Provincial Health and Family Planning Commission (2019‐ZQN‐55).

Contributor Information

Zhen‐peng Guan, Email: guanzhenpeng@qq.com.

Wen‐ming Zhang, Email: zhangwm0591@fjmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1. Kheir MM, Tan TL, Shohat N, Foltz C, Parvizi J. Routine diagnostic tests for periprosthetic joint infection demonstrate a high false‐negative rate and are influenced by the infecting organism. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2018, 100: 2057–2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pitto RP, Sedel L. Periprosthetic joint infection in hip arthroplasty: is there an association between infection and bearing surface type?. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2016, 474: 2213–2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Petis SM, Perry KI, Pagnano MW, Berry DJ, Hanssen AD, Abdel MP. Retained antibiotic spacers after total hip and knee arthroplasty resections: high complication rates. J Arthroplasty, 2017, 32: 3510–3518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nodzo SR, Boyle KK, Spiro S, Nocon AA, Miller AO, Westrich GH. Success rates, characteristics, and costs of articulating antibiotic spacers for total knee periprosthetic joint infection. Knee, 2017, 24: 1175–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Akindolire J, Morcos MW, Marsh JD, Howard JL, Lanting BA, Vasarhelyi EM. The economic impact of periprosthetic infection in total hip arthroplasty. Can J Surg, 2020, 63: E52–E56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Parvizi J, Adeli B, Zmistowski B, Restrepo C, Greenwald AS. Management of periprosthetic joint infection: the current knowledge. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2012, 94: e104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chalmers BP, Mabry TM, Abdel MP, Berry DJ, Hanssen AD, Perry KI. Two‐stage revision total hip arthroplasty with a specific articulating antibiotic spacer design: reliable periprosthetic joint infection eradication and functional improvement. J Arthroplasty, 2018, 33: 3746–3753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marczak D, Synder M, Sibiński M, Polguj M, Dudka J, Kowalczewski J. Two stage revision hip arthroplasty in periprosthetic joint infection. Comparison study: with or without the use of a spacer. Int Orthop, 2017, 41: 2253–2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grubhofer F, Imam MA, Wieser K, Achermann Y, Meyer DC, Gerber C. Staged revision with antibiotic spacers for shoulder prosthetic joint infections yields high infection control. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2018, 476: 146–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Corró S, Vicente M, Rodríguez‐Pardo D, Pigrau C, Lung M, Corona PS. Vancomycin‐gentamicin prefabricated spacers in 2‐stage revision Arthroplasty for chronic hip and knee Periprosthetic joint infection: insights into Reimplantation microbiology and outcomes. J Arthroplasty, 2020, 35: 247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sporer SM. Spacer design options and consideration for Periprosthetic joint infection. J Arthroplasty, 2020, 35: S31–S34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jones CW, Selemon N, Nocon A, Bostrom M, Westrich G, Sculco PK. The influence of spacer design on the rate of complications in two‐stage revision hip Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty, 2019, 34: 1201–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Siddiqi A, Nace J, George NE, et al. Primary Total knee Arthroplasty implants as functional prosthetic spacers for definitive Management of Periprosthetic Joint Infection: a multicenter study. J Arthroplasty, 2019, 34: 3040–3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang W, Fang X, Shi T, Cai Y, Huang Z, Zhang C, Lin J, Li W. Cemented prosthesis as spacer for two‐stage revision of infected hip prostheses: a similar infection remission rate and a lower complication rate. Bone Joint Res, 2020, 9: 484–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Diaz‐Ledezma C, Higuera CA, Parvizi J. Success after treatment of periprosthetic joint infection: a Delphi‐based international multidisciplinary consensus. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2013, 471: 2374–2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nodzo SR, Bauer T, Pottinger PS, et al. Conventional diagnostic challenges in periprosthetic joint infection. J Am Acad Orthop Surg, 2015, 23: S18–S25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yang FS, Lu YD, Wu CT, Blevins K, Lee MS, Kuo FC. Mechanical failure of articulating polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) spacers in two‐stage revision hip arthroplasty: the risk factors and the impact on interim function. BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 2019, 20: 372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Citak M, Masri BA, Springer B, Argenson JN, Kendoff DO. Are preformed articulating spacers superior to surgeon‐made articulating spacers in the treatment of PJI in THA? A literature review. Open Orthop J, 2015, 9: 255–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Valencia JCB, Abdel MP, Virk A, Osmon DR, Razonable RR. Destination joint spacers, reinfection, and antimicrobial suppression. Clin Infect Dis, 2019, 69: 1056–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]