Abstract

Transcription ceases upon stimulation of oocyte maturation and gene expression during oocyte maturation, fertilization, and early cleavage relies on translational activation of maternally derived mRNAs. Two key mechanisms that mediate translation of mRNAs in oocytes have been described in detail: cytoplasmic polyadenylation-dependent and -independent. Both of these mechanisms utilize specific protein complexes that interact with cis-acting sequences located on 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR), and both involve embryonic poly(A) binding protein (EPAB), the predominant poly(A) binding protein during early development. While mechanistic details of these pathways have primarily been elucidated using the Xenopus model, their roles are conserved in mammals and targeted disruption of key regulators in mouse results in female infertility. Here, we provide a detailed account of the molecular mechanisms involved in translational activation during oocyte and early embryo development, and the role of EPAB in this process.

Keywords: EPAB, CPEB, DAZL, MASKIN, RINGO/Spy, cytoplasmic polyadenylation

Regulation of maternally derived mRNAs' translation and presence of embryonic poly(A) binding protein (EPAB) are critical for gene expression profile in oocytes and early embryo.

Introduction

During fetal development, primordial germ cells (PGCs) migrate from their extragonadal origin to the site of future gonads, where they differentiate into oogonia and proliferate via mitosis. These oogonia then further differentiate into primary oocytes, which enter meiosis and are surrounded by a single layer of somatic cells to form primordial follicles [1, 2]. In most metazoan, oocytes become arrested at the diplotene stage of the first meiotic prophase; this first meiotic arrest may span several years in Xenopus and decades in many mammals including humans [3, 4].

Upon sexual maturation, resumption of meiosis is stimulated by gonadotropins in mammals, triggering drastic changes in the nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments of the oocyte and marking the initiation of oocyte maturation [4–6]. In oocytes, transcription ceases upon resumption of meiosis, and remains quiescent until zygotic genome activation (ZGA) [4, 6, 7]. ZGA occurs at the two-cell and four- to eight-cell stages in mouse and human embryos (although there is now evidence that mouse and human embryos experience a minor ZGA wave as early as 1-cell stage) [8, 9], respectively, in comparison to zebrafish (Dario rerio) and African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis) embryos, where the zygotic genome is fully activated upon mid-blastula transition (MBT), after 10 and 12 consecutive mitotic divisions, respectively [6, 10–14]. It is, however, noteworthy that mammalian early embryo development is slower (the first division occurs after 18–36 h, and subsequent cleavage divisions take place every ∼12 to 24 h until blastocyst formation) while D. rerio and X. laevis early embryos develop much faster until MBT (in X. laevis, the first cell division occurs 90 min after fertilization, followed by 11 synchronous divisions every 30 min). Therefore, mouse embryos take longer to reach ZGA (2 days) [15], compared to Xenopus embryos (6 h) [16].

Gene expression (defined here as protein synthesis, which results in the appearance of a characteristic or effect attributed to a particular gene in a phenotype) during oocyte maturation, fertilization, and early pre-implantation embryo development through ZGA relies exclusively on the timely translational activation of maternally derived mRNAs, while transcription remains suppressed [4, 12, 17–19]. This is made possible by the large amounts of mRNAs synthesized by fully-grown oocytes prior to the initiation of oocyte maturation [20–25]. The half-lives of many of these mRNAs are measured in days, not hours, as in most somatic cells, and 90% of these transcript are conserved until the first cleavage division [26]; ZGA is associated with intricate mechanisms regulating degradation of maternal transcripts in a timely manner [16].

In this review, we will delineate the evolutionarily conserved molecular pathways that underlie control of gene expression during early development. These pathways utilize unique mechanisms to regulate the stability and translational activation and suppression of the mRNAs in oocytes and early embryos.

Translational regulation of gene expression in oocyte and early embryo

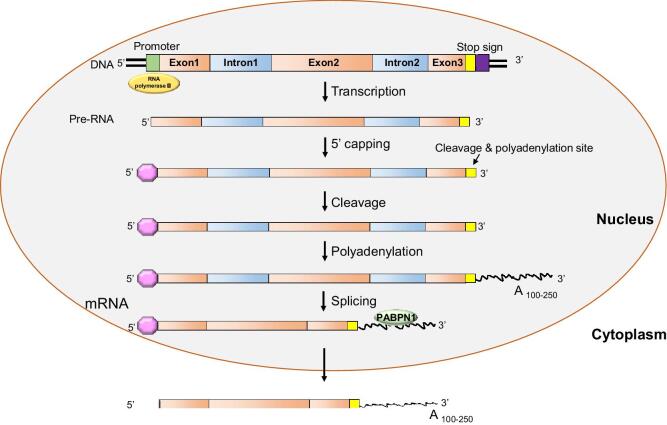

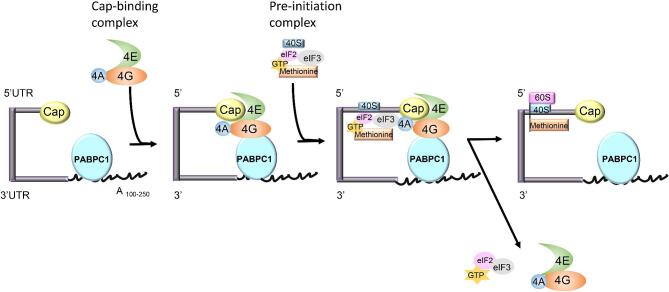

Regulation of transcription in oocytes is similar to that in somatic cells, where transcription and post-transcriptional modifications take place in the nucleus, followed by transportation of mature mRNAs into the cytoplasm (Figure 1). In somatic cells, these steps are followed by translation of the mRNA, regulated through a process that is conserved across species and involves protein complexes that have been characterized in a number of model organisms (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

mRNA synthesis and post-transcriptional modification. RNA polymerase II associates with the promoter region on DNA, located upstream of the gene of interest and continues to transcribe the short unwound DNA segment until it encounters the stop signal. This newly synthesized transcript, termed pre-mRNA then undergoes further nuclear modification before being transported into the cytoplasm. These modifications include the addition of a 7-methylguanosine residue (also known as 5′-cap) to the 5′-end of the pre-mRNA, which protect the nascent transcript against enzymatic degradation and guides exon splicing. Next, cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor (CPSF) cleaves pre-mRNA at the consensus sequence AAUAAA, located in the 3′-UTR, followed by polyadenylation at the 3′-end, forming a poly(A) tail composed of 100–250 adenosine residues. Next, non-coding introns are excised, any remaining exons are spliced, and the transcript is exported into the cytoplasm. [95–98].

Figure 2.

Regulation of mRNA translation. Once an mRNA is transported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, the cap binding complex, eIF4F, which consists of eIF4E (cap-binding subunit), eIF4A (RNA helicase) and eIF4G (scaffolding protein), binds to the target mRNA 5′-cap, and plays a vital role in translation initiation. PABPC1, a 70 kDA protein comprised of a unique poly(A)-binding domain on its C-terminus and four highly conserved RNA recognition motifs (RRMs) on its N-terminus, binds both the poly(A) tail and eIF4G. This step prevents mRNA deadenylation/degradation and allows the transcript to assume a circular structure, facilitating translation. This circular structure interacts with the pre-initiation complex, which is composed of 43S complex (which includes of 40S ribosomal subunit and eIF3) as well as a ternary complex (composed of eIF2, GTP, and methionine tRNA). This interaction is the cardinal step of translation initiation and results in 48S translation initiation complex formation. The 40S ribosomal subunit of the 48S initiation complex then scans the mRNA, starting at the 5′-end and moving towards the 3′-end, until it reaches the start codon, AUG, where it binds 60S ribosomal subunit to form the functional ribosome. [6, 17, 99–102].

In the oocyte and early embryo, translational regulation of maternally derived mRNAs utilizes a number of unique pathways that differ from the ubiquitous translational machinery of somatic cells. These pathways are primarily orchestrated by cis-acting and trans-acting elements associated with the 3′-UTR of mRNAs, and can occur via cytoplasmic polyadenylation or in a polyadenylation-independent manner [7, 27–29].

Translational activation by cytoplasmic polyadenylation

In fully grown immature oocytes, the long poly(A) tails of newly synthesized mRNAs are shortened to a length of 20–50 adenosines in the cytoplasm by deadenylation (mechanism discussed below). These deadenylated transcripts are then stored in oocyte cytoplasm for future re-activation upon induction of oocyte maturation [5, 17]. Importantly, while deadenylation of poly(A) tails in somatic cells is known to promote mRNA degradation, in oocytes and early embryos this is not the case; deadenylated transcripts can be stored in the cytoplasm in a dormant state until they are utilized [7]. Translational activation of most these transcripts require cytoplasmic polyadenylation.

Cytoplasmic polyadenylation was first identified in sea urchin oocytes and later characterized using Xenopus oocyte and early embryo models [21, 30]. Cytoplasmic polyadenylation differs from nuclear poly(A) tail extension in terms of location, regulatory mechanisms, and its specificity to gametes, embryos, and neurons [4]. Its regulatory pathways are highly conserved among species. It occurs primarily in mRNAs that contain a cytoplasmic polyadenylation element (CPE), a cis-acting element located in the 3′-UTR region, with a consensus sequence of UUUUA1-2U, that binds CPEB1 [4–6, 20, 31–34]. Transcripts of key genes involved in oocyte meiotic resumption and fertilization contain CPE in their 3′-UTRs. In Xenopus oocytes, Eg1, Cdk2, Aurora A/Eg2, Eg5, c-Mos, Wee1, and in mouse oocytes, Ccnb1, Dazl, c-Mos are among several well-characterized CPE-containing messages whose poly(A) tails extend upon initiation of oocyte maturation [20, 35–37].

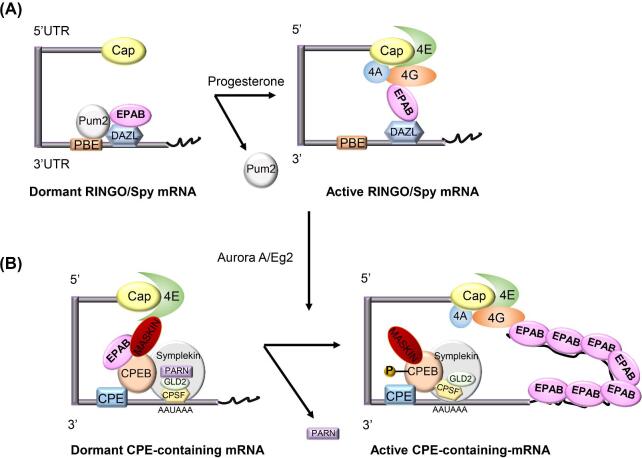

Cytoplasmic polyadenylation-dependent translation of CPE-containing mRNAs require binding of CPEB1, which becomes phosphorylated by Aurora kinase/Eg2 upon stimulation of oocyte maturation [20, 22, 34] (Figure 3B). Injection of anti-CPEB1 antibody to Xenopus oocytes results in inhibition of cytoplasmic polyadenylation of CPE-containing messages [21]; in immunodepleted oocytes, this phenomenon can be rescued partially by CPEB1 microinjection [32]. While many of the mechanistic aspects of cytoplasmic polyadenylation of CPE-containing mRNAs have been characterized in Xenopus oocytes (Figure 3B), CPEB1 seems to also play a key role in mammalian oogenesis. Tay et al. established that global CPEB1 knockout (KO) results in infertility in adult female mice; such mice have vestigial ovaries with depleted oocytes. When these mice are assessed at mid-gestational fetal stage, their ovaries comprise of oocytes arrested at the pachytene stage of meiosis I [38], suggesting that CPEB1 is crucial in earlier stages of oogenesis prior to meiotic arrest and resumption. Racki et al. generated female mice with targeted disruption of oocyte CPEB1 by using a small-interfering RNA (siRNA) under the control of zona pellucida3 (Zp3) promoter. These mice were subfertile with decreased number of oocytes and progressive oocyte loss; oocytes demonstrated increased apoptosis and underwent parthenogenesis resembling c-Mos-null mice (Table 1) [39–41]. Moreover, GV stage oocytes failed to express crucial polyadenylated transcripts such as Gdf9, Smad5 or c-Mos.

Figure 3.

Translational activation in oocytes. A. In the immature Xenopus oocyte, pumilio-2 (PUM2) is bound to PBE and suppresses its translation. PUM2 also associates with DAZL and EPAB, which act as co-repressors. In vitro hormonal induction of Xenopus oocyte maturation by progesterone leads to dissociation of PUM2 from PBE, DAZL, and EPAB. Upon dissociation, the DAZL–EPAB complex activates translation of RINGO/Spy protein [53]. B. CPEB1 binds to the CPE on dormant mRNAs stored in the cytoplasm of immature oocytes, forming a complex with the cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor (CPSF, which itself binds to the 3′-UTR cleavage and polyadenylation signal, AAUAAA), Symplekin (SYMPK) and GLD2 (an atypical polymerase responsible for elongation the mRNAs poly(A) tail). In addition, a 64 kDa poly(A) ribonuclease (PARN) isoform present in this complex in immature oocytes is responsible for the short poly(A) tails of CPE containing mRNAs. Upon stimulation of oocyte maturation, CPEB1 becomes phosphorylated, PARN leaves the complex and GLD2 initiates polyadenylation. However, simple extension of its poly(A) tail is insufficient to promote translation of an oocyte mRNA. In Xenopus oocytes, dormant CPE-containing mRNAs are bound by MASKIN, an inhibitory protein that interacts simultaneously with CPEB1 and eIF4E (bound to 5′-cap) and blocks the assembly of the translation initiation complex. For translational activation, MASKIN must be displaced from its interaction with eIF4E. As demonstrated in Xenopus oocytes, displacement of MASKIN requires that a poly(A)-binding protein become associated with the newly elongated poly(A) tail. Importantly, MASKIN is not conserved in mammals, where another protein called eIF4E-binding protein1 (eIF4E-BP1) interacts with eIF4E decreasing its availability for eIF4G. [4, 6, 17, 35, 53, 57, 76, 78, 103, 104].

Table 1.

Summary of genes involved in translational regulation of maternally derived mRNAs in oocytes and early embryo in Xenopus and mouse models.

| Deleted gene | Animal model | Method | Phenotype | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cpeb | Xenopus | Immunodepletion with anti-CPEB antibody | Halted progesterone-induced oocyte maturation. | CPEB-Ab injection inhibition of cytoplasmic polyadenylation of CPE-containing transcripts including c-mos. | 16 |

| Immunodepletion with anti-CPEB antibody | Arrested RNA polyadenylation. | Depletion of CPEB by CPEB-Ab inihibits RNA polyadenylation which can be partially rescues by CPEB injection. | 27 | ||

| Mouse | Conditional knockout with siRNA under Zp3 control | Female subfertility and progressive oocyte depletion. | Zp3-promoter mediated conditional Cpeb knock-out leads to failure of Gdf9 polyadenlation, abnormal spindle and polar body formation, increased apoptosis in granulosa cell and disrupted oocyte-cumulus attachment. | 34 | |

| Global knockout | In adult female, vestigial ovaries devoid of oocytes. In midgestation female embryo, ovaries comprising oocytes arrested in pachytene of meiosis I. | CPEB is necessary before meiotic maturation. Global knock-out of Cpeb results in absence of synaptonemal complexes and fragmented chromation. | 33 | ||

| Epab | Xenopus | Immunodepletion with anti-ePEB antibody | ePAB expression is controlled post-translationally by dynamic phosphorylation. | ePAB is dynamically phosphorylated within the cell. Its phosphorylation is crucial for cytoplasmic polyadenylation but not for translation initiation. | 12 |

| Immunodepletion with anti-ePEB antibody | Induction of mRNA deadenylation | ePAB immunodepletion induces ARE-mediated and non-ARE-mediated deadenylation of mRNAs in vitro whereas increasing ePAB concentration in the oocyte halts deadenylation. | 30 | ||

| Mouse | Global knockout | Female infertility with disrupted cumulus expansion and ovulation. | Lack of oocyte specific Epab results in disrupted cumulus cell responsiveness to EGF. | 7 | |

| Global knockout | Female infertility with absence of mature oocytes and embryo formation which cannot be rescued by Epab microinjection into GV oocytes. | Absence of translational activation of key transcripts (such as cyclin B1 or Dazl) in oocyte and decreased expression of EGF-like factors and their downstream activators which resulted in absence of cumulus expansion and decrease in ovulation. | 5 | ||

| Global knockout | Female infertility with smaller oocyte size, loose association with surrounding cumulus cells can be rescued by Epab microinjection into pre-antral follicles. | Failure of translational regulation results in arrest of meiotic maturation and abnormal chromatic reorganization. | 76 | ||

| Global knockout | Female infertility with disrupted bidirectional oocyte-cumulus cell connection. | Absence of ePAB in oocyte, leads to gap junction dysfunction and premature TZP retraction within the follicle. | 67 | ||

| Global knockout | Normal male fertility. | Male mice devoid of ePAB exhibits normal fertility parameters including litter size, sperm count, and testis size. | 82 | ||

| Dazl | Mouse | Global knockout | Female and male infertility. | DAZLa is critical for germ cell differentiation. Dazla-knock out female mice demonstrates small size ovaries with absence of follicles or oocytes. Dazla-knock out males have smaller testis mass and arrested spermatogenesis after spermatogonia stage. | 49 |

| Global knockout | Male infertility. | Germ cells in Dazl-deficient mice testis exhibited increased apoptosis. Germ cells in Dazl-deficient mice testis exhibited increased apoptosis. | 50 | ||

| Pum2 | Xenopus | Immunodepletion with anti-PUM2 antibody | RINGO/Spy translation and meiotic progression. | PUM2-Ab injection resulted in induction of RINGO/Spy translation and meiotic progression through activation of CPEB. PUM2 has to detach from RINGO/Spy transcript and its corepressor ePAB and DAZL in order to initiate translation. | 46 |

| Pum1 | Mouse | Conditional knockout under Vasa control | Progressive female subferility. | PUM1 interacts with SYCP1 and promotes meiotic progression in oocytes before they reach meiosis I arrest. PUM1, not PUM2, is essential for mammalian oocyte pool and reproductive tract formation and for meosis maturation. | 47 |

| Symplekin | Xenopus | Immunodepletion with anti-Symplekin Antibody | Inhibition of polyadenylation. | Injection of Ab against Symplekin results in suppression of polyadenylation as it fails to interact with CPEB and CPSF. | 117 |

| Maskin | Xenopus | Immunodepletion with anti-MASKIN Antibody | Cyclin B1, Wee1 and c-MOS translation induction. | MASKIN inhibits interaction of eIF4G with eIF4E, prevents CPE-containing transcripts' (Cyclin b1, Wee1, c-Mos) translation activation hence blocks oocyte maturation. MASKIN-Ab reverses these effects and induces translation. | 72 |

| c-Mos | Mouse | Global knockout | Female subfertility with failure to arrest in second metaphase. | Fertility is decreased in female mice homozygous c-Mos knock-out mice as their oocytes failed to arrest in metaphase II. | 35 |

| Global knockout | Normal male fertility. Female subfertility with failure of second meiotic arrest. | cMOS-deficient oocytes were able to mature normally until metaphase II after that they progressed into parthogenetic division without arrest. | 36 | ||

| Eden | Xenopus | Oligonucleotide directed mutagenesis | Polyadenylation of chimeric transcripts in Xenopus embryo. | After oocyte fertilization, EDEN, located in 3′UTR, is responsible with deadenylation of chimeric transcripts. Inhibition of EDEN’s ability to silence mRNAs, results in their translation. | 55 |

| Dan | Xenopus | Immunodepletion with anti-DAN Antibody | Inhibition of deadenylation during oocyte maturation | Injection of antibody against DAN impeded deadenylation during oocyte maturation which can be rescued by injection of human DAN orthologue. | 54 |

Key CPE-containing transcripts include maturation-promotion factor (MPF), a heterodimer comprising cyclin-dependent kinase1 (CDK1 or CDC2) and Cyclin B1 (CCNB1), which is required for completion of the first meiotic division [42–44]. As a response to hormonal stimulation, CDK1 is dephosphorylated by CDC25B at Thr14 and Thr15 and phosphorylated by CDK activation kinase (CAK) complex at Thr161 [45, 46]. Simultaneously, Cyclin B1 (Ccnb1), another CPE-containing transcript, undergoes translational activation through cytoplasmic polyadenylation [36, 47, 48]. In mouse, CCNB1 governs meiotic spindle formation and progression of the first meiotic spindle [5, 36, 49]. Another transcript critical for oocyte maturation containing CPE on its 3′-UTR region is c-Mos. C-MOS expression promotes translation of Ccnb1 and several other indispensable transcripts in mouse oocytes [17, 35, 41]. Through positive feedback, c-MOS also promotes further CPEB1 activation via phosphorylation and activation of the MAPK cascade [17]. Mice with global KO of c-Mos can produce mature oocytes, but they fail to arrest in metaphase II and continue with parthenogenetic division without appropriate stimuli (Table 1) [40, 41].

Polyadenylation-independent translation activation

In contrast to the above examples, certain mRNAs do not require cytoplasmic polyadenylation in order for translational activation to occur, instead following a different pathway for activation. Rapid inducer of G2/M progression in oocytes/Speedy (RINGO/Spy) is the best studies protein translated in oocytes independently of cytoplasmic polyadenylation [50]. RINGO/Spy was first identified in Xenopus oocytes and is a key protein for oocyte meiotic resumption. RINGO/Spy is almost undetectable in immature oocyte but increases significantly upon hormonal induction of oocyte maturation [50]. Translation of RINGO/Spy protein is indispensable in oocyte maturation resumption, resulting in recruitment of CDK1 and phosphorylation of Aurora A/Eg2, a protein necessary for CPEB1 phosphorylation. This critical step thus serves as a bridge between cytoplasmic polyadenylation-independent and -dependent pathways (Figure 3A).

RINGO/Spy mRNA contains a pumillio binding element (PBE) in its 3′-UTR. PBEs are among the most well-described sequences involved in translational regulation of oocytes. In the immature Xenopus oocyte, pumilio-2 (PUM2) is bound to PBE and suppresses its translation; PUM2 also associates with DAZL and EPAB, which act as co-repressors (Figure 3A). In female mice models, it has been demonstrated that pumilio-1 (PUM1) but not PUM2, is necessary for reproduction. Mak et al. generated conditional Pum1-KO mice under Vasa promoter control; these mice were subfertile exhibiting diminished ovarian reserve and premature, progressive ovarian failure, with fewer primordial follicles and lower numbers of viable ovulated oocytes. Interestingly, although injection of anti-PUM2 antibodies to Xenopus oocytes reverses the inhibitory action of PUM2 on translation activation [51], mice devoid of PUM2 do not exhibit differences in fertility (Table 1) [52].

In vitro hormonal induction of Xenopus oocyte maturation by progesterone leads to dissociation of PUM2 from PBE, DAZL and EPAB (Figure 3A). Upon dissociation, the DAZL–EPAB complex activates translation of RINGO/Spy protein [53]. Ferby et al. and Lin et al. established that DAZL is also critical in mammalian gametogenesis; global Dazl-KO results in sterility in both female and male mice. Similar to Cpeb1-KO mice, ovaries of female mice lacking Dazl are small, and lack follicles and oocytes, illustrating the importance of this protein in the early stages of oogenesis [54, 55]. DAZL is also required in later stages of oogenesis; microinjection of mopholino oligonucleotides against Dazl into GV stage oocytes results in disrupted spindle formation and chromosome assembly, lower germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD) rates during in vitro maturation (IVM) and failure of fertilization with absence of 2-cell embryo formation (Table 1) [56].

Deadenylation in oocytes and early embryos

Translational suppression is as crucial as activation; the process of translational suppression helps to ensure efficient, accurate, and stage-specific gene expression. In vertebrate somatic tissues, deadenylation promotes transcript decay by either decapping or via exonuclease activity. In contrast, during oocyte and early embryonic development, deadenylation promotes suppression of mRNA translation of the mRNAs by uncoupling them from translational machinery.

PARN (poly(A)-specific ribonuclease) also known as default deadenylase (DAN), is a key DAN described in Xenopus oocytes. Upon induction of egg maturation, PARN redistributes to the cytoplasm and associates with the protein complex that binds CPE-containing mRNAs (Figure 3B); where it promotes deadenylation [57, 58]. Deadenylated CPE-containing mRNAs are then stored in oocyte cytoplasm until stimulation of oocyte maturation, when they undergo cytoplasmic polyadenylation and become translated. Immunodepletion of PARN via targeted antibody injection in Xenopus oocytes interferes with deadenylation of messages; this phenomenon can be reversed by PARN microinjection (Table 1) [59].

Some transcripts contain deadenylation signals in their 3′-UTRs. One of the most well-described deadenylation elements (signals) in Xenopus oocytes and embryos is the Eg-specific deadenylation sequence (EDEN), which marks Eg-family and c-Mos maternally derived mRNAs for rapid deadenylation and translational repression after fertilization. This occurs by associating with EDEN-binding protein (EDEN-BP), and allows for translational silencing once transcripts activated during oocyte maturation are no longer needed. Cdk2, Aurora A/Eg2, Eg5, and c-Mos are some examples of mRNAs that contain an EDEN sequence in addition to a CPE in their 3′-UTRs [35, 58, 60, 61]. Oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis of EDEN in Xenopus oocytes results in the inhibition of translational silencing (suppression of mRNA translation).

Another deadenylation signal, adenosine and uridine-rich element (i.e. AU-rich element or ARE) in 3′-UTR, can promote mRNA deadenylation uncoupled from decay in Xenopus oocytes [62–65], whereas in somatic cells, AREs and their binding proteins (ARE-BPs) regulate gene expression by modulating translation of bound transcripts and/or by promoting their decay (i.e. mRNA half-life). Interestingly, ZFP36L2, an ARE-BP, plays a key role in transcriptional silencing that occurs upon stimulation of oocyte maturation by promoting degradation of mRNAs encoding transcription and chromatin modification regulators and is required for female fertility in mice [66, 67].

The central regulatory role of EPAB

In somatic cells and in the germline, newly transcribed mRNAs bind the poly(A)-binding protein nuclear1 (PABPN1) in the nucleus, which enhances poly(A) tail elongation and prevents degradation [4–6, 68–73]. After transport of the nascent transcript into the cytoplasm, PABPN1 is replaced by PABPC1 (reviewed above), the predominant cytoplasmic PABP in metazoan somatic cells, which is responsible for binding the poly(A) tail and initiating translation [74] (Figure 2). However, in gametes and early embryos, PABPC1 expression is minimal to absent; embryonic PABP (EPAB) instead serves as the predominant PABP, until ZGA, when EPAB is replaced by PABPC1 [74]. The tightly controlled expression of EPAB, until ZGA, suggests a pivotal role for EPAB in gene expression regulation through translation activation.

Molecular mechanisms of EPAB action—insights from the Xenopus model

EPAB was first uncovered in X. laevis by the laboratory of Joan A. Steitz [35], as the predominant cytoplasmic PABP in oocytes and early embryos until ZGA, which occurs at approximately the 4000-cell stage in X. laevis, after 12 rapid and synchronous mitotic divisions [4, 35]. The 629 amino acid-long Xenopus EPAB has 72% identity with Xenopus PABPC1, and its N-terminus contains four RNA recognition motifs (RRM)s and is 82% identical to Pabpc1, while the PAB coding C-terminus is only 56% identical [4, 6].

Xenopus EPAB is a dynamically modified phosphoprotein, found in both hypo- and hyper-phosphorylated forms [17]. Its activity is upregulated with phosphorylation, which occurs during oocyte maturation. Four loci of phosphorylation have been identified in Xenopus EPAB: Ser460, Ser461, Ser464, and Thr465 [17]. Phosphorylation at one or more of these sites is vital for cytoplasmic polyadenylation of key maternal transcripts (such as C-mos), but not for translational activation [5, 17]. Phosphorylated Xenopus EPAB associates both with translating mRNAs and protein complexes bound to mRNAs that are responsible for cytoplasmic polyadenylation and translation initiation. In contrast, endogenous hypophosphorylated EPAB is not associated with ribosomes or cap-binding complexes [5, 17].

In fully grown immature Xenopus oocytes, EPAB is part of a protein complex with the aforementioned CPEB1, SYMPK, CPSF, GLD2, and PARN, and helps store maternally derived deadenylated CPE-containing mRNAs (Figure 3B). Upon induction of oocyte maturation, the same complex promotes cytoplasmic polyadenylation and translational activation of bound mRNAs: CPEB1 becomes phosphorylated, PARN (DAN) leaves the complex, the transcript becomes polyadenylated by GLD2, and finally EPAB induces dissociation of MASKIN from the cap-binding complex, hampering its inhibitory effect [75] (Figure 3B). Displacement of MASKIN allows EPAB to directly interact with the cap-biding complex and the poly(A) tail, giving the transcript a circular shape, and allowing translation to start (Figure 3B). EPAB also associates with the DAZL-PUM1/2 complex mediating storage and subsequent cytoplasmic polyadenylation-independent translation of RINGO/Spy mRNA (Figure 3A) [4, 5, 17, 51, 76]. In in vitro studies, EPAB enhances cytoplasmic polyadenylation of CPE-containing mRNAs [17], prevents deadenylation of the elongating mRNA pol(A) tail [35], and induces translation initiation [77], which are all key steps in translational activation of dormant transcripts in oocytes [6, 75, 78].

Role of EPAB in mammalian female reproductive function

The Xenopus model constitutes a very efficient system for studying biochemistry of translational regulation as the mature X. laevis oocyte is 1.2–1.3 mm in diameter [79], compared to the 75–80 mm in diameter of mature oocytes in mouse and human, resulting in a 4000-fold larger volume, which facilitates functional experiments. However, there are a number of differences between the Xenopus and mouse (mammalian) models. One of these differences is that, unlike the case in Xenopus, blocking translation does not inhibit GVBD in mouse [80]. It is therefore very important to further study findings from Xenopus experiments, before reaching conclusions regarding implications for the mammalian system.

In mouse, Epab is located on chromosome 2 and is composed of 14 exons with a total length of 1824 base pairs [4, 6]. Like other PABPs, mouse EPAB contains 4 RRMs at its N-terminus (a.a. 1–408), responsible for binding to RNA, as well as a PABP domain at its C terminal (a.a. 409–608) [6]. In the mouse, Epab mRNA can be found alternatively spliced into different forms lacking exon 10, 11, 13, or a combination of these [6, 72]. Similar to in Xenopus, mouse Epab mRNA is limited to gonads, female and male germ cells, and pre-ZGA (1- and 2-cell) embryos. After activation of the zygotic genome, which occurs at the two-cell stage in mouse, Epab mRNA diminishes significantly and becomes undetectable between four- and eight-cell stage mouse embryo [4, 5], at which point Pabpc1, which is expressed at low levels in mouse oocytes, increases significantly [5, 73].

Female mice with global targeted deletion of Epab are infertile and cannot generate mature oocytes [5, 7]. As is seen in the Xenopus model [17], translational activation via cytoplasmic polyadenylation fails to occur in Epab-KO oocytes [5]. After 18 h of IVM, poly(A) tails of key maternal mRNAs that mediate oocyte maturation (ccnb1, c-Mos and Dazl) become significantly elongated in wild type but not in Epab-KO oocytes [5]. However, impaired cytoplasmic polyadenylation alone cannot explain the failure of Epab-KO oocytes to mature, because, as previously mentioned, unlike Xenopus, protein synthesis is not a requirement for GVBD in mouse oocytes [80–82]. EPAB must therefore be required early during mouse oogenesis for translation of mRNAs that support oocyte growth and acquisition of meiotic competence. Indeed, while the ovaries of Epab-KO mice have similar number of oocytes compared to wild type, these oocytes fail to form the hood of heterochromatin around the nucleolus characteristic of mammalian fully grown oocytes that complete transcription and become competent to resume meiosis [83, 84]. Epab-KO oocytes also show abnormal spindle formation and chromosomal misalignment [5–7, 72]. Injection of Epab mRNA into preantral follicle enclosed Epab-KO oocytes restores oocyte competence and achieves oocyte maturation, while injection into germinal vesicle (GV) stage oocytes does not, providing conclusive evidence that EPAB is required early in mammalian oogenesis, well before oocyte stimulation of maturation [5, 84].

Although Epab expression is limited to oocytes within the ovary, there are significant abnormalities in follicular development and ovulation as well as granulosa and cumulus cell differentiation and function in Epab-KO mice. While Epab-KO mice ovaries contain all stages of follicle development, their late antral follicles have decreased responsiveness to hCG (LH), with diminished expression of EGF-like growth factors (Areg, Ereg, Btc) and their downstream regulators (Tnfaip6, Ptgs2, Has2) in cumulus cells, resulting in impaired cumulus expansion and a 8-fold decrease in ovulation [5]. When Epab-KO cumulus cells are co-cultured with denuded wild type oocytes, they still fail to express Tnfaip6, Ptgs2, Has2, or undergo expansion, suggesting that absence of EPAB in the oocytes during earlier follicle development results in a permanent dysfunction in follicular somatic cells that cannot be rescued by wild type oocytes [7]. Consistent with this observation, in cultured Epab-KO granulosa cells, LH, EGF, or AREG treatment fails to increase the levels of downstream mediators p-MEK1/2, p-ERK1/2, and p-p90 ribosomal s60 kinase.

While the mechanism of the follicular somatic cell dysfunction remains to be fully elucidated (as the levels of oocyte-derived GDF9 and BMP15 are unchanged), the bidirectional communication between the oocyte and surrounding granulosa cells seems to be disrupted in Epab-KO mice ovaries. Gap junctions are small (<1 kDa) intercellular membrane channels that allow adjacent cells to share small molecules; they are composed of connexins, a homologous family of more than 20 proteins. Gap junctions are critical for follicular growth, as they are responsible for the transfer of amino acids, metabolites, and ions that are necessary for cell signaling and metabolism. Gap junctions between granulosa cells contain predominantly connexin43 (CX43); follicles lacking CX43 arrest in early pre-antral stages and produce incompetent oocytes [85–88]. Connexin37 (CX37) appears to be the only connexin contributed by oocytes to the gap junctions coupling them with granulosa cells; loss of CX37 interferes with the development of antral follicles [85–88]. Even though the levels of CX37 and CX43, are similar in Epab-KO mice to wild type counterparts, communication through gap junctions is disrupted at the stage of large pre-antral follicles (> 125 um) [73]. Similarly, transzonal processes (TZPs) which are extensions of granulosa cells that cross the zona pellucida to associate with the oocyte membrane cytoskeleton are disrupted in large pre-antral follicles of Epab-KO mice [73]. In addition, Epab mRNA copy number in oocytes increases dramatically upon transition from the primordial to the pre-antral follicle stage, providing further evidence for the key role of EPAB in pre-antral follicle enclosed oocytes [7, 73].

In sum, targeted deletion of Epab in mice results in pre-antral follicle enclosed oocytes to fail to grow, maintain communication with granulosa cells, and acquire meiotic competence; the end result is maturational arrest, impaired ovulation, and female infertility.

Role of EPAB in male gametogenesis

During male gamete maturation, transcription stops in mid-spermatogenesis, after which spermatid gene expression depends on dormant paternally stored mRNAs [89]. Similar to oogenesis, alteration of poly(A) tail length is the main posttranscriptional mechanism used to activate and regulate gene expression during spermatogenesis [89]. However, in contrast to the process in oocytes, in spermatids, deadenylation of poly(A) tail appears to serve as the primary activator of translation. Dormant transcripts’ poly(A) tails are more than 150 nucleotide long and are not associated with ribosomes, but short (approximately 30 nucleotide long) poly(A) tailed mRNAs are bound with ribosomes and are actively translated [89].

Epab expression is temporally and spatially regulated in male mouse germ cells and gonads [89]. However, in contrast to oogenesis, EPAB is not required for spermatogenesis in mouse and is dispensable for fertility [90]. Male mice lacking EPAB are viable, phenotypically normal and are able to produce equivalent numbers of pups as their wild type counterparts [90]. Sperm count, motility and apoptosis index, and testicular anatomy are also normal in male mice with targeted Epab deletion [90]. Therefore, while Epab is detected in male germ cells at different stages of differentiation, in contrast to the case in the female, it is not indispensable for male fertility. The causes of this difference in EPAB’s role in males vs. females remains unknown, and could be due to differences between the two sexes in the mechanism of polyadenylation/deadenylation and the different roles of sperm and oocyte in early embryonic gene expression.

Human EPAB

In humans, the 1857 base pair-long EPAB gene is located on chromosome 20 [4]. Its transcript is composed of 14 exons, encoding a 619 amino acid-long human EPAB, which shares 77% identity and 84% similarity and 72% identity and 83% similarity with mouse and Xenopus orthologues, respectively [4]. Similar to in Xenopus and mice, in humans, EPAB is the predominant cytoplasmic poly(A) binding protein found in both immature and mature oocytes. It is expressed in significantly higher levels in prophase I (immature), and MII (mature) oocytes compared to 8-cell and blastocyst stage embryos. The decline in EPAB mRNA coincides with ZGA and the increase in PABC1 mRNA levels [4].

Unlike Xenopus and mouse, human EPAB mRNA is expressed in a less tissue-restricted manner; it is detected in multiple somatic tissues including brain, pancreas, liver, thymus, and lung in addition to oocyte, sperm and pre-implantation embryos [4, 72]. However, the EPAB transcript that is detectable in human somatic tissues is different from the gonadal full-length EPAB. It is predominantly an alternatively spliced form lacking the first 58 base pairs of exon 8, leading to a premature stop codon 6 amino acids downstream of exon 8, which results in protein truncation and omission of the crucial PAB domain [4, 72]. There are additional alternatively spliced forms of human somatic EPAB mRNAs which lack exon 9 or both exon 9 and 10 [4]. In these alternatively spliced transcripts, the first 58 base pairs of exon 8 are also missing [72]. Somatic cells as well as 8-cell and blastocyst stage human embryos express stable but low levels of alternatively spliced, truncated, EPAB mRNA.

Alternative splicing of pre-mRNAs, enables the use different exon combinations, achieving differences in function. Alternative splicing also leads to the formation of tissue specific isoforms, which localize to different intracellular regions, and may serve different biological functions [72, 91–93]. At least 90% human genes are subject to alternative splicing, generating a diverse transcript profile [72, 91–93]. It seems that human EPAB expression is regulated primarily through alternative splicing, limiting the full-length EPAB mRNA to oocytes and pre-ZGA (2-cell and 4-cell) embryos.

Summary and conclusions

Regulation of gene expression in maturing oocytes, during fertilization, and in early cleavage embryos has unique characteristics. As transcription ceases upon meiotic resumption, gene expression in oocytes and early embryos depends exclusively on temporal and spatial regulation of translation. This occurs through timely translational activation via cytoplasmic polyadenylation-dependent and -independent mechanisms, as well as tightly regulated silencing of specific transcripts. Both translational activation and suppression involves regulatory protein complexes and utilizes cis-acting sequences located in 3′-UTRs. EPAB is the predominant poly(A) binding protein in oocytes and early embryos, until it is replaced by its somatic cell homologue PABPC1 following activation of embryonic transcription. EPAB is associated with protein complexes that bind and store mRNAs in the oocyte cytoplasm, and plays central roles in both polyadenylation-dependent and -independent translational activation of maternally derived mRNAs. EPAB and other key regulators of these pathways (CPEB1, PUM1, DAZL) are conserved in mammals and required for female fertility. EPAB’s expression pattern, limited to oocytes and pre-ZGA embryos, seems to be conserved in human, although its regulation is post-transcriptional unlike the case in Xenopus and mouse. Whether or not EPAB is required for human fertility has not yet been determined. Similarly, the roles of other mediators of translational regulation have not yet been studied in human.

Translational regulation is a unique aspect of germ cells, although CPE-mediated translational regulation has also been shown in neurons [94]. In oocytes, the need for translational regulation is obvious; transcription is no longer feasible after induction of oocyte maturation and related changes that ensue in the DNA. Neurons probably need translational regulatory mechanisms for different reasons, such as the need for rapid protein synthesis in axonal regions away from the nucleus. Male germ cells are yet another perplexing entity, as their utilization of translational regulation, and the implications for polyadenylation and deadenylation in male germ cells seem to differ from what we observe in oocytes, not to mention that male germ cells do not depend on EPAB.

It is noteworthy that, despite recent advances in the field, a number of questions remain unanswered. Are there other protein complexes that bind and help store maternally derived mRNAs? Do these complexes also bind EPAB, and if so, can this interaction be exploited for uncovering proteins and transcripts involved? Are there other translational-activation cascades? How does the oocyte and early embryo regulate the timing of activation and suppression of individual (or groups of) transcripts? To answer these questions, a number of complex studies in model systems will be necessary, followed by determination of implications for human fertility.

Notes

Edited by Dr. Lane K. Christenson

References

- 1. Sagata N. Meiotic metaphase arrest in animal oocytes: its mechanisms and biological significance. Trends Cell Biol 1996;6(1):22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adashi EY. Endocrinology of the ovary. Hum Reprod 1994;9(5):815–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. LaMarca MJ, Smith LD, Strobel MC. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of RNA synthesis in stage 6 and stage 4 oocytes of Xenopus laevis. Dev Biol 1973;34(1):106–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Guzeloglu-Kayisli O, Pauli S, Demir H, Lalioti MD, Sakkas D, Seli E. Identification and characterization of human embryonic poly(A) binding protein (EPAB). Mol Hum Reprod 2008;14(10):581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guzeloglu-Kayisli O, Lalioti MD, Aydiner F, Sasson I, Ilbay O, Sakkas D, Lowther KM, Mehlmann LM, Seli E. Embryonic poly(A)-binding protein (EPAB) is required for oocyte maturation and female fertility in mice. Biochem J 2012;446(1):47–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Seli E, Lalioti MD, Flaherty SM, Sakkas D, Terzi N, Steitz JA. An embryonic poly(A)-binding protein (ePAB) is expressed in mouse oocytes and early preimplantation embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102(2):367–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yang CR, Lowther KM, Lalioti MD, Seli E. Embryonic poly(A)-binding protein (EPAB) is required for granulosa cell EGF signaling and cumulus expansion in female mice. Endocrinology 2016;157(1):405–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Park SJ, Komata M, Inoue F, Yamada K, Nakai K, Ohsugi M, Shirahige K. Inferring the choreography of parental genomes during fertilization from ultralarge-scale whole-transcriptome analysis. Genes Dev 2013;27(24):2736–2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xue Z, Huang K, Cai C, Cai L, Jiang CY, Feng Y, Liu Z, Zeng Q, Cheng L, Sun YE, Liu JY, Horvath Set al. Genetic programs in human and mouse early embryos revealed by single-cell RNA? sequencing. Nature 2013;500(7464):593–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Flach G, Johnson MH, Braude PR, Taylor R A, Bolton V N. The transition from maternal to embryonic control in the 2-cell mouse embryo. EMBO J 1982;1(6):681–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Clegg KB, Piko L. RNA synthesis and cytoplasmic polyadenylation in the one-cell mouse embryo. Nature 1982;295(5847):342–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Newport J, Kirschner M. A major developmental transition in early Xenopus embryos: II. Control of the onset of transcription. Cell 1982;30(3):687–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Newport J, Kirschner M. A major developmental transition in early Xenopus embryos: I. characterization and timing of cellular changes at the midblastula stage. Cell 1982;30(3):675–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yuan K, Seller CA, Shermoen AW, O’Farrell PH. Timing the Drosophila mid-blastula transition: a cell cycle-centered view. Trends Genet 2016;32(8):496–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jukam D, Shariati SAM, Skotheim JM. Zygotic genome activation in vertebrates. Dev Cell 2017;42(4):316–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee MT, Bonneau AR, Giraldez AJ. Zygotic genome activation during the maternal-to-zygotic transition. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2014; 30(1):581–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Friend K, Brook M, Bezirci FB, Sheets MD, Gray NK, Seli E. Embryonic poly(A)-binding protein (ePAB) phosphorylation is required for Xenopus oocyte maturation. Biochem J 2012;445(1):93–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tadros W, Lipshitz HD. The maternal-to-zygotic transition: a play in two acts. Development 2009;136(18):3033–3042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Niakan KK, Han J, Pedersen RA, Simon C, Pera RA. Human pre-implantation embryo development. Development 2012;139(5):829–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gebauer F, Xu W, Cooper GM, Richter JD. Translational control by cytoplasmic polyadenylation of c-mos mRNA is necessary for oocyte maturation in the mouse. EMBO J 1994;13(23):5712–5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stebbins-Boaz B, Hake LE, Richter JD. CPEB controls the cytoplasmic polyadenylation of cyclin, Cdk2 and c-mos mRNAs and is necessary for oocyte maturation in Xenopus. EMBO J 1996;15(10):2582–2592. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mendez R, Hake LE, Andresson T, Littlepage LE, Ruderman JV, Richter JD. Phosphorylation of CPE binding factor by Eg2 regulates translation of c-mos mRNA. Nature 2000;404(6775):302–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Groisman I, Huang YS, Mendez R, Cao Q, Theurkauf W, Richter JD. CPEB, Maskin, and Cyclin B1 mRNA at the Mitotic Apparatus. Cell 2000;103(3):435–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Oh B, Hwang S, McLaughlin J, Solter D, Knowles BB. Timely translation during the mouse oocyte-to-embryo transition. Development 2000;127(17):3795–3803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Uto K, Sagata N. Nek2B, a novel maternal form of Nek2 kinase, is essential for the assembly or maintenance of centrosomes in early Xenopus embryos. EMBO J 2000;19(8):1816–1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hamatani T, Carter MG, Sharov AA, Ko MS. Dynamics of global gene expression changes during mouse preimplantation development. Dev Cell 2004;6(1):117–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gebauer F, Richter JD. Synthesis and function of Mos: the control switch of vertebrate oocyte meiosis. Bioessays 1997;19(1):23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hake LE, Richter JD. Translational regulation of maternal mRNA. Biochim Biophys Acta 1997;1332(1):M31–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pique M, López JM, Foissac S, Guigó R, Méndez R. A combinatorial code for CPE-mediated translational control. Cell 2008;132(3):434–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Slater DW, Slater I, Gillespie D. Post-fertilization synthesis of polyadenylic acid in sea urchin embryos. Nature 1972;240(5380):333–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bilger A, Fox CA, Wahle E, Wickens M. Nuclear polyadenylation factors recognize cytoplasmic polyadenylation elements. Genes Dev 1994;8(9):1106–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hake LE, Richter JD. CPEB is a specificity factor that mediates cytoplasmic polyadenylation during Xenopus oocyte maturation. Cell 1994;79(4):617–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hake LE, Mendez R, Richter JD. Specificity of RNA binding by CPEB: requirement for RNA recognition motifs and a novel zinc finger. Mol Cell Biol 1998;18(2):685–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stutz A, Conne B, Huarte J, Gubler P, Völkel V, Flandin P, Vassalli J-D. Masking, unmasking, and regulated polyadenylation cooperate in the translational control of a dormant mRNA in mouse oocytes. Genes Dev 1998;12(16):2535–2548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Voeltz GK, Ongkasuwan J, Standart N, Steitz JA. A novel embryonic poly(A) binding protein, ePAB, regulates mRNA deadenylation in Xenopus egg extracts. Genes Dev 2001;15(6):774–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tay J, Hodgman R, Richter JD. The control of cyclin B1 mRNA translation during mouse oocyte maturation. Dev Biol 2000;221(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Huarte J, Stutz A, O’Connell ML, Gubler P, Belin D, Darrow AL, Strickland S, Vassalli JD. Transient translational silencing by reversible mRNA deadenylation. Cell 1992;69(6):1021–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tay J, Richter JD. Germ cell differentiation and synaptonemal complex formation are disrupted in CPEB knockout mice. Dev Cell 2001;1(2):201–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Racki WJ, Richter JD. CPEB controls oocyte growth and follicle development in the mouse. Development 2006;133(22):4527–4537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Colledge WH, Carlton MBL, Udy GB, Evans MJ. Disruption of c-mos causes parthenogenetic development of unfertilized mouse eggs. Nature 1994;370(6484):65–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hashimoto N, Watanabe N, Furuta Y, Tamemoto H, Sagata N, Yokoyama M, Okazaki K, Nagayoshi M, Takeda N, Ikawa Yet al. Parthenogenetic activation of oocytes in c-mos-deficient mice. Nature 1994;370(6484):68–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Masui Y, Markert CL. Cytoplasmic control of nuclear behavior during meiotic maturation of frog oocytes. J Exp Zool 1971;177(2):129–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gautier J, Minshull J, Lohka M, Glotzer M, Hunt T, Maller JL. Cyclin is a component of maturation-promoting factor from Xenopus. Cell 1990;60(3):487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gautier J, Norbury C, Lohka M, Nurse P, Maller J. Purified maturation-promoting factor contains the product of a Xenopus homolog of the fission yeast cell cycle control gene cdc2+. Cell 1988;54(3):433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fesquet D, Labbé JC, Derancourt J, Capony JP, Galas S, Girard F, Lorca T, Shuttleworth J, Dorée M, Cavadore JC. The MO15 gene encodes the catalytic subunit of a protein kinase that activates cdc2 and other cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) through phosphorylation of Thr161 and its homologues. EMBO J 1993;12(8):3111–3121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Solomon MJ, Harper JW, Shuttleworth J. CAK, the p34cdc2 activating kinase, contains a protein identical or closely related to p40MO15. EMBO J 1993;12(8):3133–3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hampl A, Eppig JJ. Translational regulation of the gradual increase in histone H1 kinase activity in maturing mouse oocytes. Mol Reprod Dev 1995;40(1):9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Winston NJ. Stability of cyclin B protein during meiotic maturation and the first mitotic cell division in mouse oocytes. Biol Cell 1997;89(3):211–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Polanski Z, Ledan E, Brunet S, Louvet S, Verlhac M, Kubiak J, Maro B. Cyclin synthesis controls the progression of meiotic maturation in mouse oocytes. Development 1998;125(24):4989–4997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ferby I, Blazquez M, Palmer A, Eritja R, Nebreda AR. A novel p34(cdc2)-binding and activating protein that is necessary and sufficient to trigger G(2)/M progression in Xenopus oocytes. Genes Dev 1999;13(16):2177–2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Padmanabhan K, Richter JD. Regulated Pumilio-2 binding controls RINGO/Spy mRNA translation and CPEB activation. Genes Dev 2006;20(2):199–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mak W, Fang C, Holden T, Dratver MB, Lin H. An important role of Pumilio 1 in regulating the development of the mammalian female germline1. Biol Reprod 2016;94(6):134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rosario R, Adams IR, Anderson RA. Is there a role for DAZL in human female fertility? Mol Hum Reprod 2016;22(6):377–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ruggiu M, Speed R, Taggart M, McKay SJ, Kilanowski F, Saunders P, Dorin J, Cooke HJ. The mouse Dazla gene encodes a cytoplasmic protein essential for gametogenesis. Nature 1997;389(6646):73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lin Y, Page DC. Dazl deficiency leads to embryonic arrest of germ cell development in XY C57BL/6 mice. Dev Biol 2005;288(2):309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chen J, Melton C, Suh N, Oh JS, Horner K, Xie F, Sette C, Blelloch R, Conti M. Genome-wide analysis of translation reveals a critical role for deleted in azoospermia-like (Dazl) at the oocyte-to-zygote transition. Genes Dev 2011;25(7):755–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kim JH, Richter JD. Opposing polymerase-deadenylase activities regulate cytoplasmic polyadenylation. Mol Cell 2006;24(2):173–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kim JH, Richter JD. Measuring CPEB-mediated cytoplasmic polyadenylation-deadenylation in Xenopus laevis oocytes and egg extracts. Methods Enzymol 2008; 448:119–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Korner CG, Wormington M, Muckenthaler M, Schneider S, Dehlin E, Wahle E. The deadenylating nuclease (DAN) is involved in poly(A) tail removal during the meiotic maturation of Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J 1998;17(18):5427–5437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bouvet P, Omilli F, Arlot-Bonnemains Y, Legagneux V, Roghi C, Bassez T, Osborne HB. The deadenylation conferred by the 3′ untranslated region of a developmentally controlled mRNA in Xenopus embryos is switched to polyadenylation by deletion of a short sequence element. Mol Cell Biol 1994;14(3):1893–1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sheets MD, Fox CA, Hunt T, Vande W G, Wickens M. The 3′-untranslated regions of c-mos and cyclin mRNAs stimulate translation by regulating cytoplasmic polyadenylation. Genes Dev 1994;8(8):926–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wilson T, Treisman R. Removal of poly(A) and consequent degradation of c-fos mRNA facilitated by 3′ AU-rich sequences. Nature 1988;336(6197):396–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Chen CY, Shyu AB. Selective degradation of early-response-gene mRNAs: functional analyses of sequence features of the AU-rich elements. Mol Cell Biol 1994;14(12):8471–8482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Shyu AB, Belasco JG, Greenberg ME. Two distinct destabilizing elements in the c-fos message trigger deadenylation as a first step in rapid mRNA decay. Genes Dev 1991;5(2):221–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Voeltz GK, Steitz JA. AUUUA sequences direct mRNA deadenylation uncoupled from decay during Xenopus early development. Mol Cell Biol 1998;18(12):7537–7545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Dumdie JN, Cho K, Ramaiah M, Skarbrevik D, Mora-Castilla S, Stumpo DJ, Lykke-Andersen J, Laurent LC, Blackshear PJ, Wilkinson MF, Cook-Andersen H. Chromatin modification and global transcriptional silencing in the oocyte mediated by the mRNA decay activator ZFP36L2. Dev Cell 2018;44(3):392–402.e7 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Colegrove-Otero LJ, Devaux A, Standart N. The Xenopus ELAV protein ElrB represses Vg1 mRNA translation during oogenesis. Mol Cell Biol 2005;25(20):9028–9039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wahle E. 3′-end cleavage and polyadenylation of mRNA precursors. Biochim Biophys Acta 1995;1261(2):183–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wahle E. Poly(A) tail length control is caused by termination of processive synthesis. J Biol Chem 1995;270(6):2800–2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Bienroth S, Keller W, Wahle E. Assembly of a processive messenger RNA polyadenylation complex. EMBO J 1993;12(2):585–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Vasudevan S, Seli E, Steitz JA. Metazoan oocyte and early embryo development program: a progression through translation regulatory cascades. Genes Dev 2006;20(2):138–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Guzeloglu-Kayisli O, Lalioti MD, Babayev E, Torrealday S, Karakaya C, Seli E. Human embryonic poly(A)-binding protein (EPAB) alternative splicing is differentially regulated in human oocytes and embryos. Mol Hum Reprod 2014;20(1):59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lowther KM, Favero F, Yang CR, Taylor HS, Seli E. Embryonic poly(A)-binding protein is required at the preantral stage of mouse folliculogenesis for oocyte-somatic communication. Biol Reprod 2017;96(2):341–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Stambuk RA, Moon RT. Purification and characterization of recombinant Xenopus poly(A)(+)-binding protein expressed in a baculovirus system. Biochem J 1992; 287(3):761–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kim JH, Richter JD. RINGO/cdk1 and CPEB mediate poly(A) tail stabilization and translational regulation by ePAB. Genes Dev 2007;21(20):2571–2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Richter JD. CPEB: a life in translation. Trends Biochem Sci 2007;32(6):279–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wilkie GS, Gautier P, Lawson D, Gray NK. Embryonic poly(A)-binding protein stimulates translation in germ cells. Mol Cell Biol 2005;25(5):2060–2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Cao Q, Richter JD. Dissolution of the maskin-eIF4E complex by cytoplasmic polyadenylation and poly(A)-binding protein controls cyclin B1 mRNA translation and oocyte maturation. EMBO J 2002;21(14):3852–3862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Wallace RA, Misulovin Z, Etkin LD. Full-grown oocytes from Xenopus laevis resume growth when placed in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1981;78(5):3078–3082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Wassarman PM, Josefowicz WJ, Letourneau GE. Meiotic maturation of mouse oocytes in vitro: inhibition of maturation at specific stages of nuclear progression. J Cell Sci 1976;22(3):531–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. de Vant’ery C, Gavin AC, Vassalli JD, Schorderet-Slatkine S. An accumulation of p34cdc2 at the end of mouse oocyte growth correlates with the acquisition of meiotic competence. Dev Biol 1996;174(2):335–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Schultz RM, Wassarman PM. Biochemical studies of mammalian oogenesis: protein synthesis during oocyte growth and meiotic maturation in the mouse. J Cell Sci 1977; 24:167–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Mattson BA, Albertini DF. Oogenesis: chromatin and microtubule dynamics during meiotic prophase. Mol Reprod Dev 1990;25(4):374–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lowther KM, Mehlmann LM. Embryonic poly(A)-binding protein is required during early stages of mouse oocyte development for chromatin organization, transcriptional silencing, and meiotic competence1. Biol Reprod 2015;93(2):43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Gittens JE, Kidder GM. Differential contributions of connexin37 and connexin43 to oogenesis revealed in chimeric reaggregated mouse ovaries. J Cell Sci 2005;118(21):5071–5078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Simon AM, Goodenough DA, Li E, Paul DL. Female infertility in mice lacking connexin 37. Nature 1997;385(6616):525–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Juneja SC, Barr KJ, Enders GC, Kidder GM. Defects in the germ line and gonads of mice lacking connexin431. Biol Reprod 1999;60(5):1263–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Ackert CL, Gittens JE, O’Brien MJ, Eppig JJ, Kidder GM. Intercellular communication via connexin43 gap junctions is required for ovarian folliculogenesis in the mouse. Dev Biol 2001;233(2):258–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Ozturk S, Guzeloglu-Kayisli O, Demir N, Sozen B, Ilbay O, Lalioti MD, Seli E. Epab and Pabpc1 are differentially expressed during male germ cell development. Reprod Sci 2012;19(9):911–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Ozturk S, Guzeloglu-Kayisli O, Lowther KM, Lalioti MD, Sakkas D, Seli E. Epab is dispensable for mouse spermatogenesis and male fertility. Mol Reprod Dev 2014;81(5):390–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Gardina PJ, Clark TA, Shimada B, Staples MK, Yang Q, Veitch J, Schweitzer A, Awad T, Sugnet C, Dee S, Davies C, Williams Aet al. Alternative splicing and differential gene expression in colon cancer detected by a whole genome exon array. BMC Genomics 2006; 7(1):325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Wang Z, Burge CB. Splicing regulation: from a parts list of regulatory elements to an integrated splicing code. RNA 2008;14(5):802–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Kalsotra A, Cooper TA. Functional consequences of developmentally regulated alternative splicing. Nat Rev Genet 2011;12(10):715–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Lin AC, Tan CL, Lin CL, Strochlic L, Huang YS, Richter JD, Holt CE. Cytoplasmic polyadenylation and cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-dependent mRNA regulation are involved in Xenopus retinal axon development. Neural Dev 2009; 4(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Proudfoot N. New perspectives on connecting messenger RNA 3′ end formation to transcription. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2004;16(3):272–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Izaurralde E, Lewis J, McGuigan C, Jankowska M, Darzynkiewicz E, Mattaj IW. A nuclear cap binding protein complex involved in pre-mRNA splicing. Cell 1994;78(4):657–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Flaherty SM, Fortes P, Izaurralde E, Mattaj IW, Gilmartin GM. Participation of the nuclear cap binding complex in pre-mRNA 3′ processing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997;94(22):11893–11898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Zhao J, Hyman L, Moore C. Formation of mRNA 3′ ends in eukaryotes: mechanism, regulation, and interrelationships with other steps in mRNA synthesis. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 1999;63(2):405–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Dowling RJ, Topisirovic I, Alain T, Bidinosti M, Fonseca BD, Petroulakis E, Wang X, Larsson O, Selvaraj A, Liu Y, Kozma SC, Thomas Get al. mTORC1-mediated cell proliferation, but not cell growth, controlled by the 4E-BPs. Science 2010;328(5982):1172–1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Mangus DA, Evans MC, Jacobson A. Poly(A)-binding proteins: multifunctional scaffolds for the post-transcriptional control of gene expression. Genome Biol 2003;4(7):223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Kuhn U, Wahle E. Structure and function of poly(A) binding proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 2004;1678(2-3):67–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Aitken CE, Lorsch JR. A mechanistic overview of translation initiation in eukaryotes. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2012;19(6):568–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Barnard DC, Ryan K, Manley JL, Richter JD. Symplekin and xGLD-2 are required for CPEB-mediated cytoplasmic polyadenylation. Cell 2004;119(5):641–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Stebbins-Boaz B, Cao Q, de Moor CH, Mendez R, Richter JD. Maskin is a CPEB-associated factor that transiently interacts with elF-4E. Mol Cell 1999;4(6):1017–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]