Abstract

Purpose:

EGFR exon 20 insertions (ex20ins) are an uncommon genotype in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) for which targeted therapies are under development. We sought to describe treatment outcomes and genomic and immunophenotypic characteristics of these tumors.

Experimental Design:

We identified sequential patients with NSCLC with EGFR ex20ins and compared their clinical outcomes and pathologic features with other NSCLC patients.

Results:

Among 6,290 patients with NSCLC, 106 (2%) had EGFR ex20ins. Patients with EGFR ex20ins were more likely to be Black (14 vs 6%, p<0.001) or Asian (22 vs. 10%, p<0.001) compared to all other patients with NSCLC. Median tumor mutational burden (TMB) (3.5 vs. 5.9, p<0.001) and proportion of tumors with PD-L1 expression ≥1% (22 vs. 60%, p<0.001) were lower in EGFR ex20ins compared to other NSCLC (TMB n=5851, PD-L1 expression n=282) and EGFR del 19/L858R (median TMB 3.5, p=0.001; 39% PD-L1≥1%, p=0.02). Compared to a 2:1 cohort of patients with metastatic NSCLC without targetable alterations (n=192), EGFR ex20ins patients had longer overall survival (median 20 vs. 12 mo, HR 0.56, p=0.007) and longer time to treatment discontinuation (TTD) for platinum chemotherapy (median 7 vs. 4 mo, HR 0.6, p=0.02) and no improvement in TTD for immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) (HR 1.75, p=0.05).

Conclusions:

With better outcomes on platinum chemotherapy, patients with EGFR ex20ins NSCLC have improved prognosis, lower PD-L1 expression and TMB, and derive less benefit from ICI compared to NSCLC patients without targetable oncogenes. Improving molecularly targeted therapies could provide greater benefit for patients with EGFR ex20ins.

Keywords: EGFR exon 20 insertions, non-small cell lung cancer, lung adenocarcinoma, platinum chemotherapy

INTRODUCTION:

The treatment of patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has evolved rapidly in recent years, as next-generation sequencing (NGS) has facilitated identification of new molecular targets and development of multiple generations of effective targeted therapies. The effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) as monotherapy or combination therapy has further added to the repertoire of approved treatment options for NSCLC(1–5). Prior work has shown that molecular subtypes of NSCLC further influence response to standard treatments(6–8). In particular, patients with some oncogene-driven lung cancers have improved responses to chemotherapy compared to patients without oncogene-driven cancers(9,10).

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) exon 20 insertions (ex20ins) are driver alterations that comprise approximately 4–10% of EGFR-mutant NSCLC (11–13) and 2% of all NSCLC (14–16). EGFR ex20ins preferentially maintain the regulatory C-helix element of EGFR in its active, outward conformation (17), while EGFR exon 19 deletions (del 19) and L858R alterations permit constitutive receptor activation by destabilizing the inactive form of EGFR and inducing greater affinity for ATP than wild-type EGFR (18,19). Due to these conformational and mechanistic differences between classical sensitizing EGFR mutations and exon 20 insertions, NSCLC with EGFR ex20ins are generally insensitive to currently approved EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) at standard doses(20–22), although limited responses to standard dosing osimertinib have also been reported(23,24). A notable exception is EGFR A763_Y764insFQEA, an alteration found in the C-helix predicted to activate EGFR in a manner closely resembling classic sensitizing alterations, which has demonstrated sensitivity to multiple EGFR TKIs in both in vitro models and a limited number of patients(25–27).

While there are no currently approved targeted therapies for EGFR ex20ins, it is an active area for drug development with multiple promising molecularly targeted strategies in clinical trial testing. Several investigational agents, including mobocertinib (28) and amivantamab (29), have shown encouraging activity against EGFR ex20ins in early clinical trials. Osimertinib 160 mg, twice the standard dose, has shown activity in patients with EGFR ex20ins from preliminary trial results(30). The role and effectiveness of standard therapy in EGFR exon20ins remains unclear. A better understanding of the effectiveness of standard therapies in EGFR ex20ins is needed to assess whether investigational agents offer substantial benefit.

We sought to describe the clinical outcomes and response to standard therapies, including ICI, platinum-based chemotherapy, and combination chemo-ICI. We identified all patients with NSCLC and EGFR ex20ins detected by next-generation sequencing (NGS) using MSK-IMPACT (31) at our institution and retrospectively evaluated their clinical outcomes compared to a historical cohort of NSCLC without targetable alterations.

METHODS:

Patient identification:

We identified all patients with NSCLC whose tumors underwent genomic profiling with MSK-IMPACT(31) prior to July 2020 using the MSK Clinical Sequencing Cohort in cBioPortal(32,33). Patients with EGFR ex20ins were identified from this cohort, with EGFR exon 20 insertion status verified by a diagnostic molecular pathologist. A 2:1 control cohort was selected consecutively from the remaining cases after removing all cases with known driver alterations in EGFR, ALK, RET, and BRAF V600E. All patients with EGFR ex20ins and the 2:1 control cohort underwent medical record review to obtain treatment history, pathology, and basic demographic information. Basic patient (age sequencing was performed, sex, race) and tumor characteristics (histology, genomic results, and TMB) for all patients was collected from cBioPortal. As patient smoking histories were not collated for the entire cohort but were of interest to us, we used a subgroup of patients with NSCLC included in the MSK-IMPACT clinical sequencing cohort where smoking histories was available from a previously published study(6), after removing patients with EGFR exon20ins. The study was conducted in accordance with recognized ethical guidelines and was approved by the MSK Institutional Review Board/Privacy Board.

Somatic alterations were determined using MSK-IMPACT as has been previously described (31). Somatic alterations, including copy number alterations, were assessed for enrichment in EGFR ex20ins cases compared to unselected NSCLC cohort and a separate cohort of EGFR L858R/del 19 cases using Fisher’s exact test. To reduce false discovery in multiple testing, a false discovery rate q value <0.05 was applied using Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. Tumor mutational burden (TMB) was calculated across each version of the MSK-IMPACT panel (341, 410 or 468 genes) and is defined as the total number of mutations divided by the coding region analyzed. TMB is reported as mutations/megabase (Mb). Only one sample was used per patient. If patients had multiple samples available, the sample with the highest tumor purity was selected for TMB analysis. PD-L1 expression was performed as part of routine clinical care and was scored as the percentage of tumor cells with membranous staining

Statistical Methods:

Patient and tumor characteristics were compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum test, chi-square test of independence, or Fisher’s exact tests. Overall survival was defined from the date of first-line metastatic treatment to the date of death or last follow-up, with a data lock on July 15, 2020. Time to treatment discontinuation (TTD) was defined from the first date of treatment to the decision date of treatment termination or last follow-up; patients were censored if they remained on treatment by July 15,2020. Overall survival and TTD probabilities were computed using Kaplan-Meier estimates with left truncation to account for the time of MSK-IMPACT. For the delayed entry Kaplan-Meier analyses, patients may enter the risk set post-baseline if their IMPACT data were recorded after the start of treatment. Patients were also excluded if full treatment details, such as date of first-line therapy or reason for therapy discontinuation, were unknown. The comparative analysis for the time to event endpoints with respect to EGFR exon 20 mutation status was computed using the log-rank test with left truncation.

RESULTS:

Patient and tumor characteristics:

From July 2014 to July 2020, 106 patients with EGFR ex20ins were identified out of 6,290 (2%) NSCLC patients with MSK-IMPACT results and 1,507 (7%) with any EGFR mutation. Of these, 59 (56%) were diagnosed in the metastatic setting and 47 (44%) at an earlier stage, with 17 disease recurrences during the study period (supplemental Fig 1). Compared to the remaining 6,184 patients with NSCLC without EGFR ex20ins, EGFR ex20ins patients were younger (median age 66 vs. 69, p<0.001), were more frequently women (69 vs 58%, p=0.03) and Black (14 vs 6%, p=0.001) or Asian (22 vs 10%, p<0.001) (Table 1). As has been described previously (11,13), the majority of EGFR ex20ins patients had adenocarcinoma histology (96 vs 76%, p<0.001) and were never or light former smokers (88 vs. 52%, p<0.001) compared to a subgroup of patients with smoking history available (n=985).

Table 1: Patient characteristics:

Basic demographic information was compared between the 106 patients with EGFR ex20ins and all other patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who underwent genomic profiling with MSK-IMPACT. Py indicates pack-years of smoking history. “Other” histologies include carcinoid, sarcomatoid, adenosquamous, lymphoepithelial, and basaloid, among other rare histologies.

|

EGFR ex20ins n=106 n (%) |

NSCLC without EGFR ex20ins n=6,184 n (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range) | 66 (30,−90) | 69 (13, 90) | p<0.001 |

| Sex | p=0.03 | ||

| Male | 33 (31) | 2586 (42) | |

| Female | 73 (69) | 3585 (58) | |

| Not stated | 0 (0) | 13 (<1) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 61 (62) | 4875 (84) | p<0.001 |

| Asian | 22 (22) | 583 (10) | p<0.001 |

| Black | 14 (14) | 318 (6) | p=0.001 |

| Native American | 0 (0) | 9 (<1) | |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 (1) | 5 (<1) | |

| Not known | 8 (8) | 394 (6) | |

| Histology | p<0.001 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 102 (96) | 4735 (76) | |

| Squamous | 0 (0) | 655 (11) | |

| Large cell/neuroendocrine | 0 | 142 (2) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 4 (4) | 387 (6) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 277 (4) | |

| Smoking history | n=985 | p<0.001 | |

| Never smoker | 63 (59) | 314 (32) | |

| ≤15 py | 31 (29) | 192 (20) | |

| >15 py | 12 (11) | 468 (48) | |

| Not known | 0 | 11 (1) | |

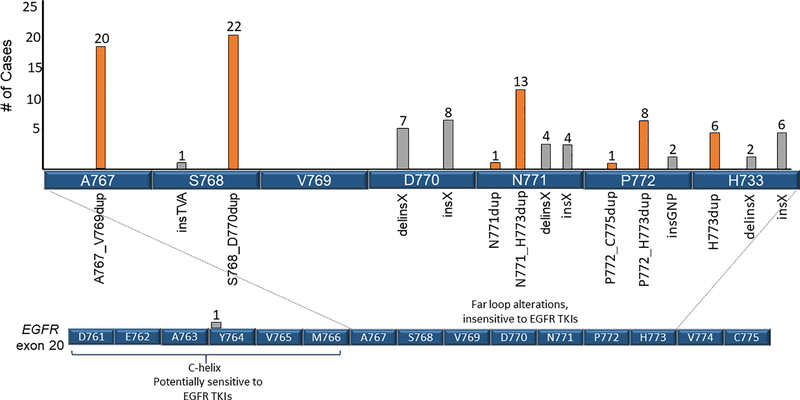

We identified 15 distinct exon 20 insertion alterations. The most commonly observed were S768_D770 duplication (n=22, 21%), A767_V769 duplication (n=20, 19%), and N771_H773 duplication (n=13, 12%) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Exon 20 insertions.

15 distinct EGFR ex20ins were identified. The locations and number of each insertion are identified, along with amino acids 761D to 766M, which comprise the regulatory C-helix. Only one insertion (A763_Y764insFQEA) was found in the C-helix; this alteration is predicted to be sensitizing to EGFR TKIs. Amino acids 767A to 775C compose the loop following the C-helix (far loop alterations) where the majority of EGFR ex20ins events occur. Duplication events are labeled in orange and other insertion events are in gray.

Clinical outcomes and response to therapy:

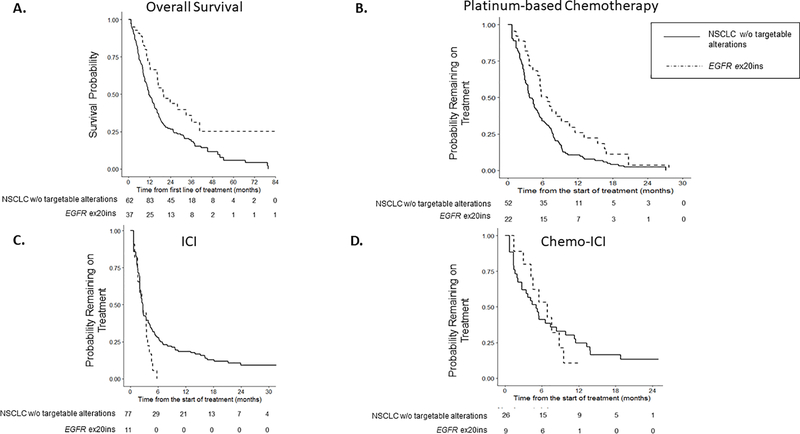

We next evaluated survival from initiation of first-line metastatic treatment. With a median follow-up of 1.3 years (range 0.2 to 17 years), 62 patients with EGFR ex20ins and 192 patients without driver alterations were included. Median survival for patients with EGFR ex20ins was 20 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 17 months to not reached), compared to 12 months for patients without targetable alterations (95% CI 10 to 15 months), with HR 0.56 (95% CI 0.37 to 0.86, p=0.007, Fig. 2A).

Figure 2: Clinical Outcomes.

A. Overall survival for EGFR ex20ins cohort was compared to patients with NSCLC without targetable driver alterations B. Time to treatment discontinuation (TTD) on platinum chemotherapy C. TTD for immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) D. TTD for chemo-ICI. To account for left truncation, any cases where MSK-IMPACT resulted after end of treatment, date of death, or last clinic follow-up were excluded. For the delayed entry Kaplan-Meier analyses, patients may enter the risk set post-baseline if their IMPACT data were recorded after the start of treatment.

Given well-established data that patients with EGFR ex20ins do not benefit from currently approved EGFR TKIs at standard doses, we focused on time to treatment discontinuation (TTD) for standard therapies for metastatic NSCLC: platinum-based doublet therapy +/− bevacizumab, ICI and chemo-ICI. In this analysis, 31 patients with EGFR ex20ins and 94 NSCLC patients without targetable alterations who received platinum chemotherapy in the metastatic setting (Supplemental Table 1) were included. The most common reason for treatment discontinuation was progressive disease (PD), which occurred in 65% of patients with EGFR ex20ins and 70% of those patients without targetable oncogenic drivers. Patients with EGFR ex20ins had longer TTD on platinum-based chemotherapy compared to patients without targetable alterations with median time of 7 vs. 4 months (HR 0.60, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.93, p=0.02) (Fig. 2B).

The next most common standard therapy received was ICI treatment with anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 antibodies, with 15 EGFR ex20ins and 99 control patients included. Among EGFR ex20ins, 6 (40%), 5 (33%), and 4 (27%) of patients received ICI as the first, second, or third or greater line of treatment, compared to 72% of control patients receiving ICI as second-line treatment. All EGFR ex20ins patients discontinued ICI for PD, compared to 77 (78%) control patients, with the remaining 10 control patients discontinuing ICI for toxicity. Duration of treatment with ICI was not different for patients with and without EGFR ex20ins (median TTD 2.8 vs. 2.8 mo, HR 1.75, 95% CI 1.0 to 3.1, p=0.05, Fig. 2C). We also assessed outcomes for the small subset of patients who received chemo-ICI, including12 patients with EGFR ex20ins and 36 control patients. The most common treatment given was carboplatin, pemetrexed, and pembrolizumab. The median time on chemo-ICI was similar for patients with EGFR ex20ins and control patients (median 7 vs. 5 months, HR 1.1, 95% CI 0.52 to 2.41, p=0.8, Fig. 2D).

Genomic and Immunophenotypic Characteristics:

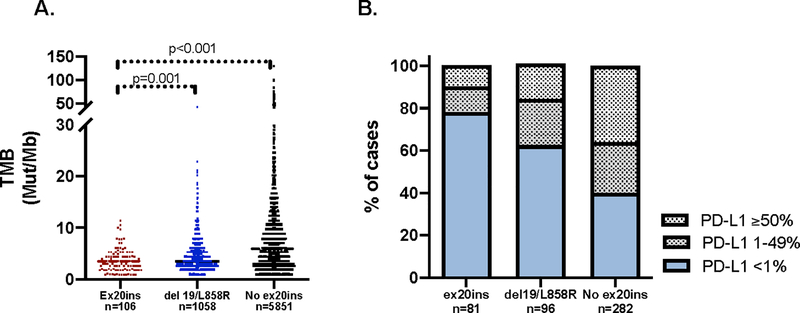

To determine whether known prognostic and predictive factors were different in patients with EGFR ex20ins, we compared genomic and immunophenotypic characteristics of EGFR ex20ins tumors to all NSCLC without EGFR ex20ins and tumors with classical EGFR alterations (del 19 and L858R). Of the 6,290 unique NSCLC patients with MSK-IMPACT available at the time of analysis, 1,088 patients had EGFR del 19 or L858R. The tumor mutational burden (TMB) in tumors with EGFR ex20ins (median TMB 3.4, interquartile range [IQR] 1.8 to 4.6, n=106) was lower than that observed in EGFR del 19/L858R (median 3.5, IQR 2.6 to 5.6, p=0.001, n=1058) and NSCLC without EGFR ex20ins (median 5.9, IQR 3.0 to 10.0, p<0.001, n=5,851) (Fig. 3A). Among available tumor samples, a higher proportion of tumors with EGFR del 19/L858R had PD-L1% expression ≥1% compared to EGFR ex20ins tumors (39% vs. 22%, p=0.02, Fisher’s exact). A higher proportion of tumors without EGFR ex20ins also had PD-L1 expression ≥1% compared to EGFR ex20ins tumors (60% vs. 22%, p<0.001, Fisher’s exact) (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3: Immunophenotype of exon 20 insertion cases.

A. Median tumor mutational burden (TMB) from available cases is significantly lower in EGFR exon 20 insertion (ex20ins) cases compared to both EGFR del 19/L858R tumors and NSCLC tumors without EGFR ex20ins B. Tumor PD-L1 expression was quantified as low (<1%), intermediate (1–49%) and high (≥50%) for available cases and tabulated across ex20ins, EGFR del19/L858R cases, and NSCLC without EGFR ex20ins tumors.

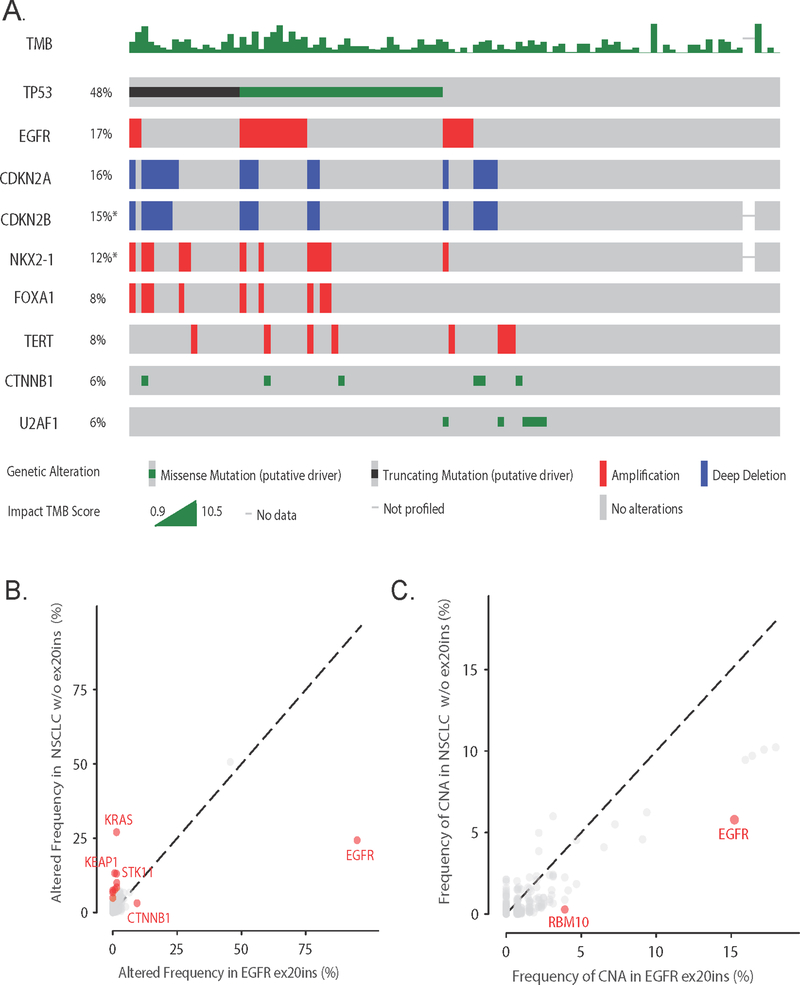

We next evaluated the frequency of co-occurring genomic alterations. Co-mutations that were observed in the EGFR ex20ins cohort at a frequency ≥5% were in TP53 (48%), CTNNB1 (6%), and U2AF1 (6%). Copy number alterations (CNA) observed at ≥5% frequency were EGFR amplifications (17%), deletions in CDKN2A (17%) and CDKN2B (16%), and amplifications in NKX2–1 (12%), FOXA1 (8%), and TERT (8%) (Fig. 4A). We identified that alterations in KRAS (27%, any alteration), STK11 (13%), KEAP1 (13%), NF1 (7%), PTPRT (7%), RBM10 (10%), KMT2D (8%), SETD2 (5%), and PTPRD (9%) occur more frequently in tumors without EGFR ex20ins, while mutations in EGFR (100 vs. 24%) and CTNNB1 (9 vs. 3%) were more common in tumors with EGFR ex20ins (p<0.001, q<0.05 by Benjamini-Hochberg) (Fig. 4B). EGFR (15 vs. 6%) and RBM10 (4 vs. 0.3%) amplifications were also enriched in tumors with EGFR ex20ins (p<0.001, q<0.03) (Fig 4C). We next compared the genomic landscape of EGFR ex20ins to classical EGFR del 19 and L858R cases, but there were no somatic alterations associated with either cohort that met our statistical thresholds. There were no CNAs enriched in EGFR ex20ins cases compared to EGFR del 19/L858R cases.

Figure 4:

Genomic landscape of EGFR ex20ins. A. Oncoprint of the mutations and copy number alterations found at ≥5% frequency among ex20ins cases, with TMB quantified at top of graph B. Frequency of altered genes in EGFR ex20ins cohort compared to NSCLC without EGFR ex20ins. Genes highlighted in red designate q-value <0.05. C. Frequency of CNA in the EGFR ex20ins cohort compared to other NSCLC cases.

DISCUSSION:

In this analysis, we have described the clinical outcomes of patients with EGFR ex20ins NSCLC, an uncommon driver alteration in NSCLC, as well as the molecular features of these tumors. We found that EGFR ex20ins occurred in 2% of all patients with NSCLC and 7% of patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancers. Overall, we found that EGFR ex20ins were more prevalent in Black patients, Asian patients and never smokers and that patients with EGFR ex20ins have a somewhat greater benefit with platinum-based chemotherapy than NSCLC patients without a targetable alteration.

Prior reports on clinical outcomes of EGFR ex20ins patients have largely focused on the lack of response to EGFR TKIs and have provided limited data on response to cytotoxic and immune-based NSCLC therapies. Our analysis may serve as a benchmark to assess the efficacy of multiple investigational agents targeting EGFR ex20ins in single-arm clinical trials. In other molecularly defined NSCLC populations, targeted therapies for EGFR and ALK alterations have shown clear survival and response benefits over chemotherapy, as would be expected of oncogene-addicted cancers dependent on driver alterations (34–41). In our North American cohort, we found that patients with EGFR ex20ins have encouraging responses to platinum chemotherapy, with median TTD of 7 months that was superior to responses observed in an NSCLC cohort without driver alterations. These results are in concordance with these previously published studies. A study of Chinese patients with EGFR ex20ins reported a progression-free survival (PFS) of 6 months on first-line platinum-based chemotherapy(42). A study of 22 Korean patients reported a 50% objective response rate (ORR)with platinum chemotherapy(43). One possible explanation for this finding is that oncogene-addicted NSCLC is more sensitive to pemetrexed, with which all patients with EGFR ex20ins were treated, than other NSCLC. This has been demonstrated with other oncogene-driven NSCLC, including ALK(9,44), ROS1(45) and RET(10). Given the low number of patients in our cohorts treated with chemo-ICI, future studies are required to evaluate whether patients with EGFR ex20ins derive greater clinical benefit from chemo-ICI compared to platinum chemotherapy. This remains an important question to answer as it will enable clinicians to appropriately sequence therapies, but of note, combination platinum chemotherapy and pembrolizumab is not FDA approved for patients with EGFR mutations(46)

The suboptimal response to ICI observed among patients with EGFR ex20ins aligns with previous observations that ICI have poor activity in patients with NSCLC with driver alterations. A series of EGFR-mutant lung cancers previously reported poor responses to ICI(47). In the IMMUNOTARGET registry, patients with the common EGFR exon 19 deletion or L858R mutations, or fusions in RET, ROS1 or ALK had ORRs to ICI <20% and PFS less than 3.5 months (48). This may be explained partially by low tumor PD-L1 expression and low TMB, which have been consistently reported in NSCLC tumors with driver alterations(49). However recent work suggests that PD-L1 expression does not predict responsiveness to immune checkpoint blockade in patients with EGFR exon 19 deletion or L858R cancers (50)and may be of limited utility in predicting responsiveness to ICI in EGFR-mutant lung cancer. A further consideration for potentially avoiding ICI in patients with EGFR ex20ins is the risk for severe immune-related adverse events if osimertinib is given following ICI, as has been demonstrated in patients with sensitizing EGFR alterations(51). Overall, our results suggest that ICI may not be a fruitful later-line therapy for patients with EGFR ex20ins.

Given the rarity of EGFR ex20ins, the overall number of patients receiving each line of therapy is a limitation of this single-institution retrospective study. In this retrospective analysis, we used TTD rather than RECIST-based response rate or PFS to assess clinical efficacy, although TTD may approximate PFS(52). Our study population was also heterogeneous and received each category of treatment at varying time points of metastatic disease, which may confound the responses reported. Finally, a source of potential bias is that all patients included in our study underwent genomic profiling with MSK-IMPACT, which resulted in fewer patients with squamous cell carcinoma included in the comparator cohort (estimated real-world prevalence 30%, compared to 11% prevalence in our cohort). Despite these limitations, this study remains among the largest cohorts of patients with EGFR exon 20 insertions reported. The distribution of unique EGFR exon 20 insertions in our cohort is similar to previous reports, with the majority of insertions occurring in the far loop region following the C-helix (26,53,54). However, our cohort included only one patient with A763_Y764insFQEA—an alteration sensitizing to EGFR TKIs—while other studies have cited frequencies of 5–10%.

In summary, we describe here comprehensive genomic, immunophenotypic, and clinical outcomes of patients with EGFR ex20ins. We anticipate that patients with EGFR ex20ins will be increasingly recognized and understanding the response to standard therapies will help clinicians determine what treatments to offer to patients unable to enroll in clinical trials or who have exhausted trial options. Our analysis demonstrates that with low TMB and low PD-L1, EGFR ex20ins tumors are similar to EGFR del 19/L858R in genomic landscape and have relatively few genomic or immunophenotypic vulnerabilities to exploit with standard therapy options after progression on platinum-based chemotherapy. Given the promising activity of several investigational targeted therapies for EGFR ex20ins, these remain the preferred option for patients with EGFR ex20ins over later line ICI or non-platinum chemotherapy.

Supplementary Material

TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE:

An uncommon NSCLC genotype, EGFR exon 20 insertions are the subject of active drug development, although no targeted therapies have yet been approved. The response to standard therapies for these cancers has not been well characterized and is needed to serve as a benchmark to assess the efficacy of investigational agents in single-arm trials. We sought to describe the response to standard treatments for these patients and provide a comprehensive analysis of the molecular features of EGFR exon 20 insertion NSCLC. While responses to platinum chemotherapy are encouraging compared to NSCLC without targetable alterations, responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors are shorter. We report that EGFR exon 20 insertion tumors have low PD-L1 tumor expression, low TMB and infrequent co-alterations. Our results highlight the need for targeted therapies in this patient population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

This work was supported by the Ramapo Trust, John and Georgia DallePezze, and was funded in part by the Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis Center for Molecular Oncology and the National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Core Grant No. P30-CA008748. We gratefully acknowledge the members of the Molecular Diagnostics Service in the Department of Pathology.

Financial Disclosures: The authors report the following disclosures: CMR—consulting or advisory role: AbbVie, Harpoon Therapeutics, Genentech, AstraZeneca, Ascentage Pharma, Bicycle Therapeutics, Celgene, Daiichi Sankyo, Ipsen, Loxo, PharmaMar, Bridge Medicines, Amgen, Jansen, Syros. Pharmaceuticals Research Funding: AbbVie/Stemcentrx (Inst), Viralytics (Inst), Merck (Inst), Daiichi Sankyo (Inst), Genentech (Inst); MGK—consultant or advisory role: AstraZeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo, Novartis, and Sanofi Genzyme and editorial support from Genentech; MEA—Honoraria and consulting fees: Invivoscribe, Biocartis, AstraZeneca. HY—consultant or advisory role for AstraZeneca, Janssen, Blueprint Med, C4 Therapeutics, and Daiichi. Research funding: AstraZeneca (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Daiichi (Inst), Cullinan (Inst), Lilly (Inst), and Novartis (Inst). ML— consulting or advisory role: Takeda Oncology, Janssen Pharmaceuticals. GR—research funding: Roche (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Millennium (Inst), Mirati (Inst), and Merck (Inst). All other authors report no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Gandhi L, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, Esteban E, Felip E, De Angelis F, et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2018;378(22):2078–92 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1801005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mok TSK, Wu YL, Kudaba I, Kowalski DM, Cho BC, Turna HZ, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously untreated, PD-L1-expressing, locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-042): a randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019;393(10183):1819–30 doi 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32409-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hellmann MD, Ciuleanu TE, Pluzanski A, Lee JS, Otterson GA, Audigier-Valette C, et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Lung Cancer with a High Tumor Mutational Burden. The New England journal of medicine 2018;378(22):2093–104 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1801946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csoszi T, Fulop A, et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2016;375(19):1823–33 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, Felip E, Perez-Gracia JL, Han JY, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016;387(10027):1540–50 doi 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01281-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schoenfeld AJ, Bandlamudi C, Lavery JA, Montecalvo J, Namakydoust A, Rizvi H, et al. The Genomic Landscape of SMARCA4 Alterations and Associations with Outcomes in Patients with Lung Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 2020. doi 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-20-1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skoulidis F, Goldberg ME, Greenawalt DM, Hellmann MD, Awad MM, Gainor JF, et al. STK11/LKB1 Mutations and PD-1 Inhibitor Resistance in KRAS-Mutant Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cancer discovery 2018;8(7):822–35 doi 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-18-0099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arbour KC, Jordan E, Kim HR, Dienstag J, Yu HA, Sanchez-Vega F, et al. Effects of Co-occurring Genomic Alterations on Outcomes in Patients with KRAS-Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2018;24(2):334–40 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-17-1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaw AT, Varghese AM, Solomon BJ, Costa DB, Novello S, Mino-Kenudson M, et al. Pemetrexed-based chemotherapy in patients with advanced, ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 2013;24(1):59–66 doi 10.1093/annonc/mds242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drilon A, Bergagnini I, Delasos L, Sabari J, Woo KM, Plodkowski A, et al. Clinical outcomes with pemetrexed-based systemic therapies in RET-rearranged lung cancers. Ann Oncol 2016;27(7):1286–91 doi 10.1093/annonc/mdw163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arcila ME, Nafa K, Chaft JE, Rekhtman N, Lau C, Reva BA, et al. EGFR exon 20 insertion mutations in lung adenocarcinomas: prevalence, molecular heterogeneity, and clinicopathologic characteristics. Molecular cancer therapeutics 2013;12(2):220–9 doi 10.1158/1535-7163.Mct-12-0620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yasuda H, Kobayashi S, Costa DB. EGFR exon 20 insertion mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer: preclinical data and clinical implications. Lancet Oncol 2012;13(1):e23–31 doi 10.1016/s1470-2045(11)70129-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oxnard GR, Lo PC, Nishino M, Dahlberg SE, Lindeman NI, Butaney M, et al. Natural history and molecular characteristics of lung cancers harboring EGFR exon 20 insertions. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer 2013;8(2):179–84 doi 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182779d18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jordan EJ, Kim HR, Arcila ME, Barron DA, Chakravarty D, Gao J, et al. Prospective Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Lung Adenocarcinomas for Efficient Patient Matching to Approved and Emerging Therapies. Cancer discovery 2017:CD-16–1337 doi 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-16-1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kris MG, Johnson BE, Berry LD, Kwiatkowski DJ, Iafrate AJ, Wistuba II, et al. Using Multiplexed Assays of Oncogenic Drivers in Lung Cancers to Select Targeted Drugs. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 2014;311(19):1998–2006 doi 10.1001/jama.2014.3741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aisner DL, Sholl LM, Berry LD, Rossi MR, Chen H, Fujimoto J, et al. The Impact of Smoking and TP53 Mutations in Lung Adenocarcinoma Patients with Targetable Mutations-The Lung Cancer Mutation Consortium (LCMC2). Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2018;24(5):1038–47 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-17-2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eck MJ, Yun CH. Structural and mechanistic underpinnings of the differential drug sensitivity of EGFR mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010;1804(3):559–66 doi 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landau M, Ben-Tal N. Dynamic equilibrium between multiple active and inactive conformations explains regulation and oncogenic mutations in ErbB receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta 2008;1785(1):12–31 doi 10.1016/j.bbcan.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yun CH, Boggon TJ, Li Y, Woo MS, Greulich H, Meyerson M, et al. Structures of lung cancer-derived EGFR mutants and inhibitor complexes: mechanism of activation and insights into differential inhibitor sensitivity. Cancer cell 2007;11(3):217–27 doi 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naidoo J, Sima CS, Rodriguez K, Busby N, Nafa K, Ladanyi M, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor exon 20 insertions in advanced lung adenocarcinomas: Clinical outcomes and response to erlotinib. Cancer 2015;121(18):3212–20 doi 10.1002/cncr.29493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang JC, Sequist LV, Geater SL, Tsai CM, Mok TS, Schuler M, et al. Clinical activity of afatinib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring uncommon EGFR mutations: a combined post-hoc analysis of LUX-Lung 2, LUX-Lung 3, and LUX-Lung 6. Lancet Oncol 2015;16(7):830–8 doi 10.1016/s1470-2045(15)00026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu JY, Wu SG, Yang CH, Gow CH, Chang YL, Yu CJ, et al. Lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor exon 20 mutations is associated with poor gefitinib treatment response. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2008;14(15):4877–82 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-07-5123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fang W, Huang Y, Hong S, Zhang Z, Wang M, Gan J, et al. EGFR exon 20 insertion mutations and response to osimertinib in non-small-cell lung cancer. BMC cancer 2019;19(1):595 doi 10.1186/s12885-019-5820-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Veggel B, Madeira RSJFV, Hashemi SMS, Paats MS, Monkhorst K, Heideman DAM, et al. Osimertinib treatment for patients with EGFR exon 20 mutation positive non-small cell lung cancer. Lung cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2020;141:9–13 doi 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montenegro GB, Kim C. P1.14–52 Clinical Response to Osimertinib in a Patient with Metastatic NSCLC Harboring EGFR A763_Y764insFQEA Exon 20 Insertion Mutation: A Case Report. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2019;14(10):S575–S6 doi 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.08.1203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yasuda H, Park E, Yun C-H, Sng NJ, Lucena-Araujo AR, Yeo W-L, et al. Structural, Biochemical, and Clinical Characterization of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) Exon 20 Insertion Mutations in Lung Cancer. Science translational medicine 2013;5(216):216ra177–216ra177 doi 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vasconcelos PENS, Gergis C, Viray H, Varkaris A, Fujii M, Rangachari D, et al. EGFR-A763_Y764insFQEA Is a Unique Exon 20 Insertion Mutation That Displays Sensitivity to Approved and In-Development Lung Cancer EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. JTO Clinical and Research Reports 2020;1(3) doi 10.1016/j.jtocrr.2020.100051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janne PA, Neal JW, Camidge DR, Spira AI, Piotrowska Z, Horn L, et al. Antitumor activity of TAK-788 in NSCLC with EGFR exon 20 insertions. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2019;37(15_suppl):9007– doi 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.9007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haura EB, Cho BC, Lee JS, Han J-Y, Lee KH, Sanborn RE, et al. JNJ-61186372 (JNJ-372), an EGFR-cMet bispecific antibody, in EGFR-driven advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Journal of Clinical Oncology 2019;37(15_suppl):9009– doi 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.9009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piotrowska Z, Wang Y, Sequist LV, Ramalingam SS. ECOG-ACRIN 5162: A phase II study of osimertinib 160 mg in NSCLC with EGFR exon 20 insertions. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2020;38(15_suppl):9513– doi 10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.9513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheng DT, Mitchell TN, Zehir A, Shah RH, Benayed R, Syed A, et al. Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT): A Hybridization Capture-Based Next-Generation Sequencing Clinical Assay for Solid Tumor Molecular Oncology. The Journal of molecular diagnostics : JMD 2015;17(3):251–64 doi 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal 2013;6(269):pl1 doi 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer discovery 2012;2(5):401–4 doi 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mok TS, Wu Y-L, Ahn M-J, Garassino MC, Kim HR, Ramalingam SS, et al. Osimertinib or Platinum–Pemetrexed in EGFR T790M–Positive Lung Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2016;376(7):629–40 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1612674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shaw AT, Kim D-W, Nakagawa K, Seto T, Crinó L, Ahn M-J, et al. Crizotinib versus Chemotherapy in Advanced ALK-Positive Lung Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2013;368(25):2385–94 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1214886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, Sugawara S, Oizumi S, Isobe H, et al. Gefitinib or Chemotherapy for Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer with Mutated EGFR. New England Journal of Medicine 2010;362(25):2380–8 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, Feng J, Liu XQ, Wang C, et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2011;12(8):735–42 doi 10.1016/s1470-2045(11)70184-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, Vergnenegre A, Massuti B, Felip E, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology 2012;13(3):239–46 doi 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70393-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang JC, Wu YL, Schuler M, Sebastian M, Popat S, Yamamoto N, et al. Afatinib versus cisplatin-based chemotherapy for EGFR mutation-positive lung adenocarcinoma (LUX-Lung 3 and LUX-Lung 6): analysis of overall survival data from two randomised, phase 3 trials. Lancet Oncol 2015;16(2):141–51 doi 10.1016/s1470-2045(14)71173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Solomon BJ, Mok T, Kim D-W, Wu Y-L, Nakagawa K, Mekhail T, et al. First-Line Crizotinib versus Chemotherapy in ALK-Positive Lung Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2014;371(23):2167–77 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1408440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Soria JC, Tan DSW, Chiari R, Wu YL, Paz-Ares L, Wolf J, et al. First-line ceritinib versus platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer (ASCEND-4): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 2017;389(10072):917–29 doi 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)30123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang G, Li J, Xu H, Yang Y, Yang L, Xu F, et al. EGFR exon 20 insertion mutations in Chinese advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients: Molecular heterogeneity and treatment outcome from nationwide real-world study. Lung cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2020;145:186–94 doi 10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Byeon S, Kim Y, Lim SW, Cho JH, Park S, Lee J, et al. Clinical Outcomes of EGFR Exon 20 Insertion Mutations in Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer in Korea. Cancer Res Treat 2019;51(2):623–31 doi 10.4143/crt.2018.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Camidge DR, Kono SA, Lu X, Okuyama S, Barón AE, Oton AB, et al. Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase Gene Rearrangements in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer are Associated with Prolonged Progression-Free Survival on Pemetrexed. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2011;6(4):774–80 doi 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31820cf053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen Y-F, Hsieh M-S, Wu S-G, Chang Y-L, Yu C-J, Yang JC-H, et al. Efficacy of Pemetrexed-Based Chemotherapy in Patients with ROS1 Fusion–Positive Lung Adenocarcinoma Compared with in Patients Harboring Other Driver Mutations in East Asian Populations. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2016;11(7):1140–52 doi 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.KEYTRUDA (pembrolizumab) prescribing information. FDA; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hastings K, Yu HA, Wei W, Sanchez-Vega F, DeVeaux M, Choi J, et al. EGFR mutation subtypes and response to immune checkpoint blockade treatment in non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 2019;30(8):1311–20 doi 10.1093/annonc/mdz141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mazieres J, Drilon A, Lusque A, Mhanna L, Cortot AB, Mezquita L, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for patients with advanced lung cancer and oncogenic driver alterations: results from the IMMUNOTARGET registry. Ann Oncol 2019;30(8):1321–8 doi 10.1093/annonc/mdz167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lan B, Ma C, Zhang C, Chai S, Wang P, Ding L, et al. Association between PD-L1 expression and driver gene status in non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2018;9(7):7684–99 doi 10.18632/oncotarget.23969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schoenfeld AJ, Rizvi H, Bandlamudi C, Sauter JL, Travis WD, Rekhtman N, et al. Clinical and molecular correlates of PD-L1 expression in patients with lung adenocarcinomas✰. Annals of Oncology 2020;31(5):599–608 doi 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.01.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schoenfeld AJ, Arbour KC, Rizvi H, Iqbal AN, Gadgeel SM, Girshman J, et al. Severe immune-related adverse events are common with sequential PD-(L)1 blockade and osimertinib. Ann Oncol 2019;30(5):839–44 doi 10.1093/annonc/mdz077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blumenthal GM, Gong Y, Kehl K, Mishra-Kalyani P, Goldberg KB, Khozin S, et al. Analysis of time-to-treatment discontinuation of targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and chemotherapy in clinical trials of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Annals of Oncology 2019;30(5):830–8 doi 10.1093/annonc/mdz060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vyse S, Huang PH. Targeting EGFR exon 20 insertion mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2019;4(1):5 doi 10.1038/s41392-019-0038-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robichaux JP, Elamin YY, Tan Z, Carter BW, Zhang S, Liu S, et al. Mechanisms and clinical activity of an EGFR and HER2 exon 20-selective kinase inhibitor in non-small cell lung cancer. Nature medicine 2018;24(5):638–46 doi 10.1038/s41591-018-0007-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.