Abstract

Purpose

Population-based cancer statistics, including histology-specific incidence, prevalence, and survival are essential to evaluating the total burden due to disease in a population. The National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Comprehensive Oncology Network Evaluating Rare CNS Tumors (NCI-CONNECT) was developed to better understand tumor biology and patient outcomes for 12 selected brain and other central nervous system (CNS) tumor histologies that are rare in adults to improve approaches to care and treatment. The aim of this study was to determine the incidence, prevalence, and survival of these selected rare histologies.

Methods

Data from the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States (CBTRUS) from 2000 to 2014 were used to calculate average annual age-adjusted incidence rates (AAIR) per 100,000 population overall and by sex, race, ethnicity, and age. NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data were used to calculate relative survival (RS) estimates. Point prevalence for 2014 was estimated using annual age-specific incidence and survival from CBTRUS and SEER, respectively.

Results

Overall AAIR was 1.47 per 100,000 for all 12 rare histologies combined, with the highest histology-specific incidence in oligodendrogliomas (AAIR = 0.40/100,000). Overall, most histologies were more common in males, adults (age 40 + ), Whites, and non-Hispanics. Ependymomas were the most prevalent histology at 4.11 per 100,000; followed by oligoden-drogliomas at 3.68 per 100,000. Relative survival at 1-, 5-, and 10-years was 82.3%, 64.0%, and 55.4%, respectively for all 12 selected brain and other CNS tumor types combined. Ependymomas had the highest RS (1-year = 94.2%, 5-year = 83.9%, 10-year = 78.6%) and gliosarcomas had the lowest relative survival rate (1-year = 42.5%, 5-year = 5.6%, 10-year = 2.9%) at all three time points.

Conclusions

Incidence and prevalence of these rare brain and other CNS tumor histologies have not been previously reported. Along with survival, these data provide a statistical foundation to understand the impact of these cancers and provide important disease-specific data for the design of prospective clinical trials.

Keywords: Rare tumors, Incidence, Survival, Prevalence, CNS tumors

Introduction

Primary brain and other central nervous system (CNS) tumors are relatively rare, with an average annual age-adjusted incidence rate (AAIR) of 23.03 per 100,000 for all malignant and non-malignant histologies [1, 2]. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor (AT/RT), brain stem and midline glioma, choroid plexus tumors, ependymoma, high grade meningioma, gliomatosis cerebri, medulloblastoma, oligodendroglioma/anaplastic oligodendroglioma, pineal region tumors, pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma/anaplastic pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, supratentorial embryonal tumors/primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNET), and primary CNS sarcoma, are rarer than other malignant CNS histologies [1].

Measuring tumor-specific incidence, prevalence, and survival are essential when evaluating the contribution of specific tumor-types to overall cancer burden in the United States population. The mission of the newly convened National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Comprehensive Oncology Network Evaluating Rare CNS Tumors (NCI-CONNECT) is to advance understanding of CNS cancers that are rare in adults by establishing and fostering patient–advocacy–provider partnerships and networks to improve approaches to care and treatment. Understanding the incidence patterns and prevalence of these tumors is critical information that is necessary for planning clinical trials.

The Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States (CBTRUS) and NCI-CONNECT together aimed to determine the incidence, prevalence, and survival of 12 selected rare brain and other CNS tumor histologies by age, race, ethnicity, and sex. These data will serve as the foundation for clinical studies exploring education, community outreach, and clinical and treatment associated outcomes.

Materials and methods

Data collection

Incidence and frequency data were obtained from the CBTRUS analytic file from 2000 to 2014 containing incidence data representing 100% of the US population. Data were derived from 51 central cancer registries, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC), 46 National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) and five NCI Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registries. CBTRUS represents the most in depth source of cancer registry data for brain and CNS tumors in the US [1]. All tumors included in this analysis were newly diagnosed primary malignant tumors, and do not include recurrent tumors or metastases.

Survival data were obtained from the SEER analytic database files for malignant brain and CNS tumors from 2000 to 2014 [3], derived from 18 registries, representing approximately 28% of the US population, and are a subset of cases included in the CBTRUS dataset. All survival times were calculated based on the date of primary diagnosis.

Statistical analyses

This analysis included 12 primary malignant brain and other CNS tumor histology groups: AT/RT, brain stem and midline gliomas, choroid plexus tumors, ependymoma, high grade meningioma, gliomatosis cerebri (as determined by imaging features), medulloblastoma, oligodendroglioma/anaplastic oligodendroglioma, pineal region tumors, pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma/anaplastic pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, PNET, and primary CNS sarcoma. The International Classification of Disease for Oncology, Third Edition (ICD-O-3) morphology codes for these histologies are in Supplemental Table 1. Ependymoma was assessed in more detail by site and histology (Supplemental Table 8).

Cases were stratified by race [White, Black, Other (Asians or Pacific Islanders and American Indians/Alaska Natives), ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic)], age (children ages 0–14 years, adolescents and young adults (AYA) ages 15–39 years, adults ages 40–64 years, and older adults ages 65 + years), and sex. Cases where race was classified as unknown or unspecified were excluded from the data stratified by race but included in all other analyses. All rates were adjusted to the 2000 US standard population. AAIR, age-adjusted prevalence rates (AAPR), and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated using newly diagnosed cases in SEER*Stat and are reported per 100,000 population. Incidence rate ratios (IRR) and corresponding 95% CIs and p-values were calculated in SEER*Stat using methods described by Fay [4, 5].

Relative survival (RS), which is a measure adjusting observed survival for expected rate of death due to other causes, was calculated using the SEER 18 registries in SEER*Stat 8.3.5 statistical software [6]. All survival estimates presented are calculated based on the date of initial diagnosis, and only for individuals where the brain or other CNS tumor was their first diagnosed malignancy. RS rates were estimated at 1-, 5-, and 10-year intervals.

Point prevalence counts and AAPR in 2014 were calculated using age-specific CBTRUS incidence data and SEER observed survival data as described by Zhang et al. to estimate the total number of surviving individuals who were diagnosed with a primary CNS tumor between 2000 and 2014 [7]. When observed survival was not able to be calculated for an age stratum due to small sample size, the overall observed survival was used. AAPR and their corresponding 95% CI are reported per 100,000 population. Statistics were suppressed when fewer than 16 cases were reported, per CDC’s NPCR agreement with CBTRUS. However, these cases were included in overall counts. Figures were generated using R statistical software, version 3.5.1 [8].

Results

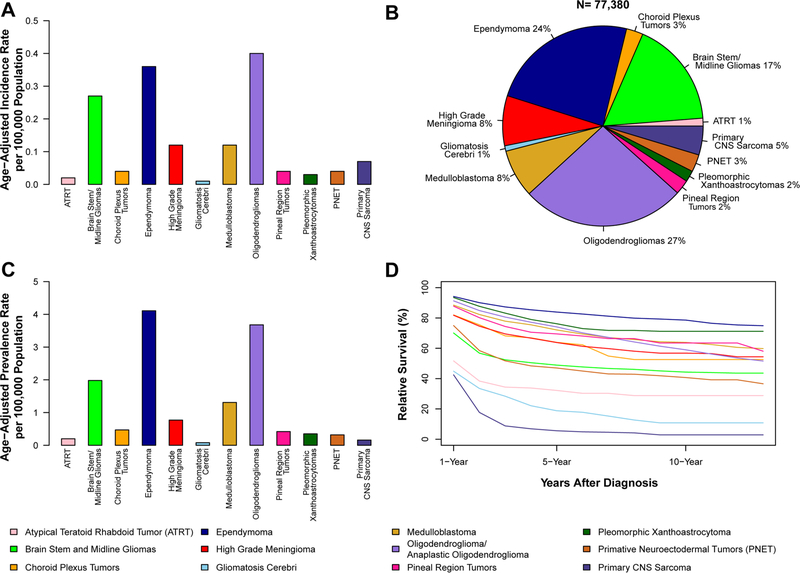

The overall total incidence of these 12 selected rare CNS histologies was 1.47 per 100,000 (95% CI 1.46–1.48) (Supplemental Table 2). Oligodendroglioma and anaplastic oligodendroglioma (AAIR = 0.40 per 100,000, 95% CI 0.40–0.41 (Fig. 1a) had the highest incidence and represented 27% of cases across all selected histologies (Fig. 1b). Gliomatosis cerebri (AAIR = 0.01 per 100,000, 95% CI 0.01–0.01) had the lowest AAIR. Ependymoma had the highest estimated prevalence in 2014 (13,294 cases, AAPR = 4.11 per 100,000, 95% CI 4.03–4.18), while prevalence of gliomatosis cerebri was lowest (247 cases, AAPR = 0.08 per 100,000, 95% CI 0.07–0.09) (Fig. 1c; Supplemental Table 2).

Fig. 1.

a Annual average age-adjusted incidence rates, brain and other central nervous system (CNS) tumors by selected histology, CBTRUS, 2000–2014; b Tumor distribution, brain and other CNS tumors by selected histology, CBTRUS, 2000–2014; c age-adjusted point prevalence rates, brain and other CNS tumors by selected histology, CBTRUS and SEER, 2014; d 1-, 5-, and 10-year relative survival rates for brain and other CNS tumors by selected histology, SEER 18 Registries, 2000–2014

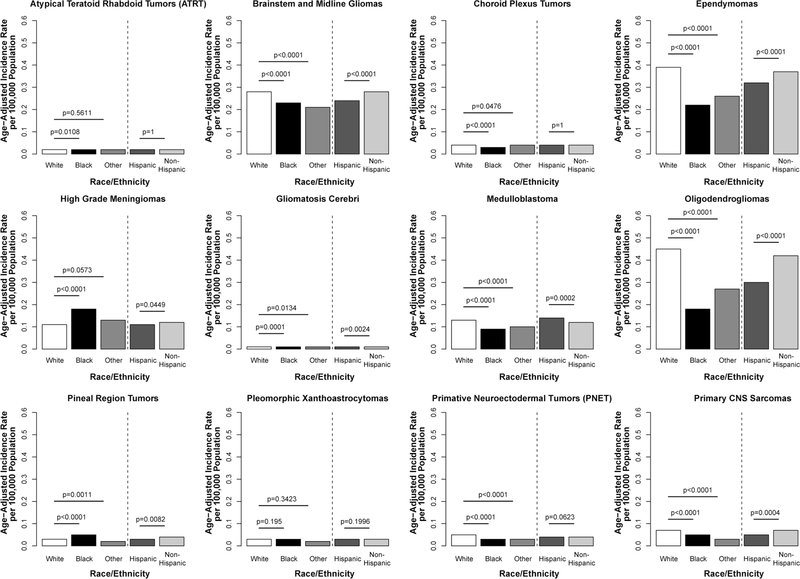

The overall race-specific incidence of the 12 selected histologies was highest among the White population (AAIR = 1.56 per 100,000, 95% CI 1.55–1.57) and lowest among the Black population (AAIR = 1.05 per 100,000, 95% CI 1.03–1.08, IRR = 0.68. p < 0.0001) (Supplemental Table 3). The largest difference was observed in oligoden-drogliomas (White AAIR = 0.45, 95% CI 0.44–0.45, Black AAIR = 0.18, 95% CI 0.17–0.19, IRR = 0.40, p < 0.0001). The only histology to occur with a higher incidence among Black individuals was high-grade meningioma, where incidence was 58% higher as compared to Whites (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Annual average age-adjusted incidence rates for selected histologies by race and ethnicity, CBTRUS, 2000–2014

Overall, incidence of the selected histologies was highest among non-Hispanics (AAIR = 1.15, 95% CI 1.50–1.52) as compared to Hispanics (AAIR = 1.27, 95% CI 1.24–1.30) (Supplemental Table 3). Most histologies occurred more frequently in non-Hispanics, with the largest difference in gliomatosis cerebri (IRR = 0.59, p = 0.0024). The exception to this pattern was medulloblastoma, where incidence was 14% higher among Hispanics (IRR = 1.14, p = 0.0002).

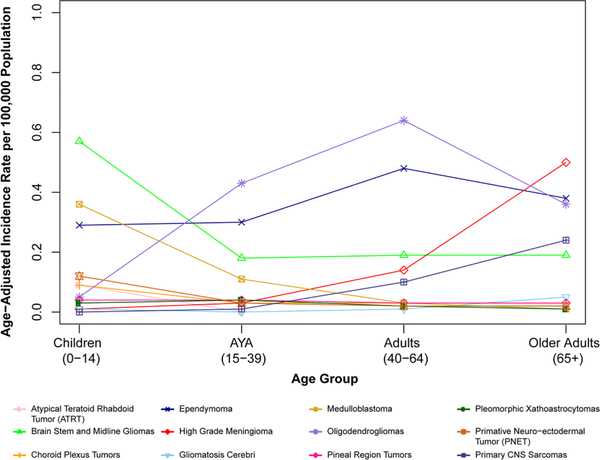

Overall, AAIR was highest in adults age 65 + years (AAIR = 1.75 per 100,000, 95% CI 1.72–1.78) and lowest in AYA (AAIR = 1.17 per 100,000, 95% CI 1.15–1.17) (Supplemental Table 4). While most of the 12 selected histologies rarely occurred in children ages 0–14 years, it is interesting to note that the highest incidence among individuals ages 0–14 years was in brainstem and midline gliomas (AAIR = 0.57 per 100,000, 95% CI 0.55–0.59) and medulloblastoma (AAIR = 0.36 per 100,000, 95% CI 0.35–0.37) (Fig. 3). Among AYA, the most commonly occurring histologies were oligodendrogliomas (AAIR = 0.43, 95% CI 0.42–0.44) and ependymoma (AAIR = 0.30, 95% CI 0.29–0.31).

Fig. 3.

Annual average age-adjusted incidence rates for selected histologies by age group, CBTRUS, 2000–2014

Among adults age 40–64 years, the highest incidence for oligodendrogliomas (AAIR = 0.64 per 100,000, 95% CI 0.63–0.65), and for ependymomas (AAIR = 0.48 per 100,000, 95% CI 0.46–0.49) was found (Fig. 3). The most frequently occurring histology in older adults (age 65 + years) was high-grade meningioma. Multiple histologies occurred at high frequency in this same age group, including high-grade meningioma (AAIR = 0.50 per 100,000, 95% CI 0.48–0.52), gliomatosis cerebri (AAIR = 0.05 per 100,000, 95% CI 0.04–0.05), and primary CNS sarcoma (AAIR = 0.24 per 100,000, 95% CI 0.23–0.26) (Fig. 3).

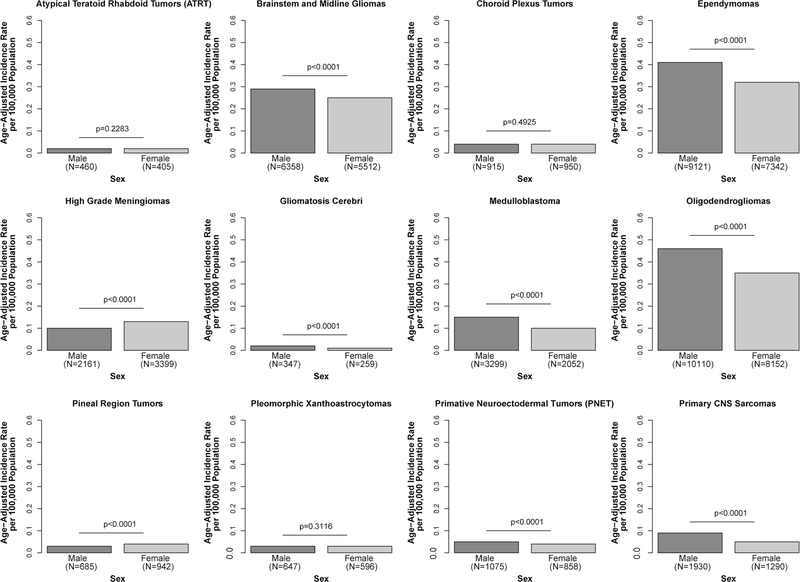

The overall incidence of these 12 selected rare CNS tumors was higher among males (AAIR = 1.61 per 100,000, 95% CI 1.60–1.63) compared with females (AAIR = 1.34 per 100,000, 95% CI 1.33–1.36, IRR = 0.83, p < 0.0001) (Supplemental Table 5). Oligodendrogliomas were the most commonly observed brain tumors in both males (AAIR = 0.46, 95% CI 0.45–0.47) and females (AAIR = 0.35, 95% CI 0.35–0.36). Most histologies occurred significantly more frequently in males, with the exception of AT/RT, choroid plexus tumors, and pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma in which there was no significant difference. Only two of the tumors studied were seen more commonly in females: high-grade meningioma (female AAIR = 0.13 per 100,000, 95% CI 0.13–0.14, male AAIR = 0.10 per 100,000, 95% CI 0.10–0.11, IRR = 1.29, p < 0.0001) and pineal region tumors (female AAIR = 0.04, 95% CI 0.04–0.04, male AAIR = 0.03, 95% CI 0.03–0.03, IRR = 1.36, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Annual average age-adjusted incidence rates for selected histologies by sex, CBTRUS, 2000–2014

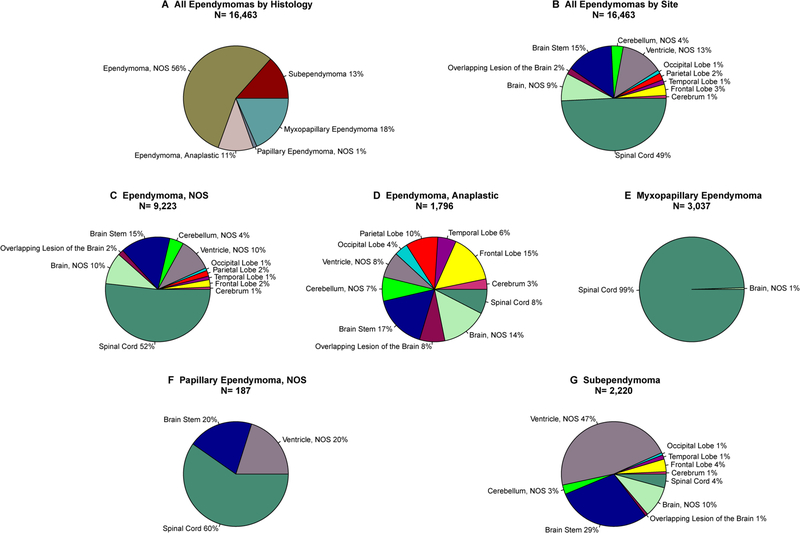

While ependymoma had the second highest incidence (after oligodendrogliomas), in 2014, these tumors were the most prevalent of all selected histologies. The most common ependymoma subtype was ependymoma, not otherwise specified [NOS, most likely grade II by WHO classification (56%)], followed by myxopapillary ependymoma (18%), subependymoma (13%), anaplastic ependymoma (11%), and papillary ependymoma, NOS (1%) (Fig. 5). For ependymoma, NOS 52% of cases were located in the spinal cord, 15% in the brain stem, and 10% in the ventricles and non-specified brain (Supplemental Table 6). In contrast, 99% of myxopapillary ependymomas were located in the spinal cord, with only 1% found in the brain. Subependymomas were found in the ventricles 47% of the time and 29% in the brain stem. Anaplastic ependymomas were the most widely distributed ependymomas by site, however these were most commonly located in the brain stem (17%). The rarest type of ependymoma, papillary ependymoma, was most commonly located in the spinal cord (60%) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Ependymoma frequency by histological type and site, CBTRUS, 2000–2014

Overall 1-, 5-, and 10-year RS for all CNS tumor types studied were 82.3%, 64.0%, and 55.4%, respectively (Supplemental Table 7). Ependymoma had the highest RS (1-year = 94.2%, 5-year = 83.9%, 10-year = 78.6%). Primary CNS sarcoma had the lowest RS (1-year = 42.5%, 5-year = 5.6%, 10-year = 2.9%) (Fig. 1d). RS varied substantially by age at diagnosis (Supplemental Table 8). In all histologies where survival was able to be calculated for older adults (ages 65 + years), survival in this group was substantially lower as compared to adults ages 40–64 years.

Discussion

Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors (AT/RT)

AT/RT are a highly malignant and predominantly pediatric form of brain cancer and represent only 3% of all pediatric (age 0–19 years) brain and other CNS tumors. It was estimated that there were 596 prevalent cases of these tumors in 2014 (AAPR = 0.20, 95% CI 0.18–0.22) (Supplemental Table 2). Results here show similar findings with an AAIR of 0.02 per 100,000 (95% CI 0.02–0.02). Previous survival rates for AT/RT ranged from a 1-year survival rate of 46.8% (data from 2001 to 2010), a 3-year survival rate of 22% (data from 1988 to 2004), a 5-year survival rate of 39.5% (data from 1996–2006), and a 5-year survival rate of 28.3% (data from 2001 to 2010) [9–11], however, these studies used data from significantly different timeframes when calculating average survival. These results are similar to those found in this analysis, where 1-year RS was 51.7%, 5-year RS was 32.2%, and 10-year RS was 28.8%.

Brain stem and midline gliomas

The little research conducted on brain stem and midline glioma incidence, prevalence, and survival showed that these tumors are most common in children [12–15]. It was estimated that for all age groups there were 6033 prevalent cases of these tumors in 2014 (AAPR = 1.98, 95% CI 1.93–2.03). We found an overall AAIR of 0.27 per 100,000 (95% CI 0.26–0.27) and an average of 791 newly diagnosed cases occurring annually, including 344 in children, 190 in AYA, 184 in adults age 40–64 years, and 73 in older adults age 65 + years. Our results support previous work which found that brain stem and midline gliomas were more common in males than females (IRR = 0.87, p < 0.0001) and in Whites than Blacks (IRR = 0.83, p < 0.0001) and all other races (IRR = 0.74, p < 0.0001) [13]. A 2016 study focusing on adults with brainstem gliomas showed a 5-year survival of 81.5% [15]. which is higher than reported in our study (5-year RS = 48.9%), however, our lower results include both adults and children. The recent discovery of specific mutations in histone genes, such as H3K27, in the majority of midline and brainstem tumors will likely impact future incidence and outcomes reports. These histone-mutated tumors have an overall worse outcome than other brain stem gliomas, particularly those with isocitrate dehydrogenase ½ (IDH½) genes which have been reported to result in a favorable outcome.

Choroid plexus tumors

Choroid plexus tumors are rare epithelial brain tumors, with an estimated 1423 prevalent cases in 2014 (AAPR = 0.47, 95% CI 0.45–0.50). Studies have shown incidence as low as 0.03 cases per 100,000 within a patient population consisting primarily of children age 0–14 years, aligning closely with a previous study by Wolff et al. (AAIR = 0.04 per 100,000, 95% CI 0.04–0.04) [16]. Our results are also consistent with previous research showing choroid plexus tumors are more common in children than in other age groups [17, 18]. However, our results (male:female IRR = 1.03, p = 0.4925), did not align with previous studies that have shown a slightly higher incidence in males than females. The 5-year RS of 63.9% (95% CI 52.8–73.0) found in our study is similar to other studies showing survival rates between 50 and 72% [17].

High grade meningioma

Meningiomas are the most frequently diagnosed type of primary brain and other CNS tumors. However, only ~ 1.2% of all meningiomas are high grade, also known as WHO grade III or anaplastic meningioma [1, 19]. Since most meningiomas are benign (WHO grade I/II), prior studies addressing the epidemiology of high-grade meningiomas are often based on small sample sizes. It was estimated that there were 2692 prevalent cases of these tumors in 2014 (AAPR = 0.77, 95% CI 0.74–0.80) for all age groups. Previous studies showed grade III meningiomas as slightly more common in females than males, more common in Blacks than any other race, and as having a higher incidence in non-Hispanics than Hispanics. A previous CBTRUS publication showed high-grade meningioma was more common in adults age 65 + years than any other age group [19–21]. The results from this current study agreed with all previously published results: increased incidence in females (IRR = 1.29, p < 0.0001), increased incidence in Blacks (IRR = 1.58, p < 0.0001), and a slightly higher increased incidence in non-Hispanics (IRR = 0.90, p = 0.0449). The overall incidence of these tumors increased with age and was highest in older adults age 65 + years. In 2015, CBTRUS showed a decrease in high-grade meningioma incidence of 0.13 per 100,000 in 2000 to 0.06 per 100,000 in 2010 [19], which may reflect changes in classification over time. Five-year survival (RS = 63.8%, 95% CI 60.2–67.3) has remained similar to the 2015 results showing 5-year survival of 66% for malignant meningiomas [22].

Gliomatosis cerebri

Gliomatosis cerebri is a rare type of diffuse glioma with considerable infiltration of a widespread region of the CNS and involves at least three cerebellar lobes [23]. Due to its rarity, aggressive nature, and typically fatal outcomes, very little research has been conducted on these tumors. It was estimated that there were 247 prevalent cases of gliomatosis cerebri in 2014 (AAPR = 0.08, 95% CI 0.07–0.09) over all age groups. Supporting prior studies [24], we found a slightly increased incidence in males (0.02 per 100,000 as compared to 0.01 per 100,000 in females), though this difference was not statistically significant. Incidence was highest in older adults age 65 + years (0.05 per 100,000). A study involving a pediatric population found these tumors to be highly fatal with only 3 of the 13 individuals in the study alive after 7, 16, and 22 months, and with no one surviving more than 6 years [25]. We also found that the outcomes for patients with gliomatosis cerebri were poor across all races, ethnicities, ages, and sexes with a 1-year RS of 44.9% (95% CI 36.7–52.7), a 5-year RS of 18.8% (95% CI 11.8–27.2), and a 10-year RS of 10.8% (95% CI 5.1–19.0). To our knowledge, this study may be the most comprehensive data published on gliomatosis cerebri, a histology that, as of 2016, has been removed from the WHO classification of CNS tumors [2]. Instead, these tumors have been included in a group of tumors with a widespread and very invasive growth pattern rarely identified in gliomas that provide unique challenges in management [2, 23].

Medulloblastoma

Medulloblastoma and supratentorial embryonal tumors previously existed as one tumor category (Medulloblastoma/PNET) instead of being separated into different entities [26]. Beginning with the WHO 2007 classification of CNS tumors, these tumors were differentiated into separate histologies under the broad category of embryonal tumors, a category that also includes AT/RT. It was estimated that there were 3840 prevalent cases of these tumors in 2014 (AAPR = 1.31, 95% CI 1.27–1.35). This study found that medulloblastoma was more common in males than females (IRR = 0.61, p < 0.0001) and in children than any other age group (IRR = 12.72 as compared to adults age 40–64 years, p < 0.001), similar to previous studies [26–31]. Nonetheless, the average annual age-adjusted incidence of these rare tumors in those 15 years and older in our study was 639 cases with 156 cases in adults age 65 + years as compared to children (844 cases) (Fig. 3). Our study also showed a slightly higher incidence in Whites (White:Blacks IRR = 0.64 and White:Other IRR = 0.73, p < 0.0001). Additionally, we found a higher 5-year RS of 72.1% (2000–2014) compared to a 2007 study that reported a 5-year survival rate of 51.5% between the years 1997 and 2005 [26]. This is likely due to improved screening measures and targeted treatment resulting from the development of a molecular classification for four distinct subgroups of medulloblastoma [32]. Cancer registration in the United States prior to 2018 did not include collection of the molecular histology subgroup information for medulloblastoma.

Primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNET)

All previous studies have consistently found that that PNET was more common in children than adults, as was the case in this analysis (Adults:Children IRR = 6.11, p < 0.0001; and Adults:AYA IRR = 1.53, p < 0.0001). It was estimated that there were 950 prevalent cases of these tumors in 2014 (AAPR = 0.32, 95% CI 0.30–0.34). A study published in 2012 found an overall incidence of 0.06 per 100,000 for PNET within the United States [28], which is similar but slightly higher than the results of this analysis (AAIR = 0.04, 95% CI 0.04–0.05). Differences in incidence by sex, race, and ethnicity have not been previously reported, but were shown in our analysis as slightly higher incidence in Whites (White:Black IRR = 0.70, p < 0.0001 and White:Other IRR = 0.63, p < 0.0001), and in males (IRR = 0.81, p < 0.0001) [28]. Furthermore, the results from our study showed PNET had a low survival rate with 47.0% of individuals alive after 5 years and only 40.7% of individuals alive after 10 years, which is similar to what has been reported in prior studies [33].

Oligodendrogliomas

Oligodendrogliomas are a relatively rare type of glioma that predominantly affect adults [34–36]. It was estimated that there were 11,757 prevalent cases in 2014 (AAPR = 3.68, 95% CI 3.61–3.75). A study published in 2017 included 7001 participants of which 93.5% were adults and only 6.5% were children under the age of 19 years [36]. The results from our study agreed with an AAIR of 0.05 per 100,000 (95% CI 0.05–0.06, Adults:Children IRR = 0.08, p < 0.0001, Adults:AYA IRR = 0.67, p < 0.0001) in children under the age 15 years, an AAIR of 0.43 per 100,000 (95% CI 0.42–0.44) in AYA, an AAIR of 0.64 per 100,000 (95% CI 0.63–0.65) in adults age 40–64 years, and an AAIR of 0.36 per 100,000 (95% CI 0.35–0.38, Adults:Older adults IRR = 0.57, p < 0.0001) in older adults over the age of 65 years. The AAIR for adults (age 40–64 years) was higher than the AAIR of 0.20 per 100,000 found in Europe in 2008 for this same age group [34]. This difference in incidence could be attributed to geographic variation in cancer registration patterns or potential differences in diagnosis, however, more research is needed to determine this. The aforementioned European study also showed a 1-year survival of 80% and a 5-year survival of 51% [34]. An American study, on the other hand, showed a 5-year survival of 85% and a 10-year survival of 81% [37]. The results of this current study showed an RS of 91.3% (95% CI 90.5–92.2) after one year, 74.1% (95% CI 72.6–75.5) after 5 years, and 59.0% (95% CI 57.0–60.9) after 10 years. The difference in survival may be due to geographic location in the European study, the timeframe of diagnosis in the European study (1990–1994), or the fact that the American study predominantly focused on a pediatric patient population. However, all studies verified the rarity of oligodendrogliomas and the incurability of these tumors. Going forward, the WHO criteria for diagnosis with the 2016 guidelines, no longer relies solely on histologic observations [25]. The new criteria include the presence of a mutation in IDH½ and the loss of the short arm of chromosome 1 and the long arm of chromosome 19 (1p/19q co-deletion). This refined definition will likely alter the incidence, prevalence, and outcomes data used in future analyses.

Pineal region tumors

Pineal region tumors are rare, overall comprising only 0.2% of all primary brain and other CNS tumors occurring in the pineal region. It was estimated that there were 1297 prevalent cases of these tumors in 2014 (AAPR = 0.42, 95% CI 0.39–0.44). Previous studies have reported that these tumors predominantly affected those under the age of 19 years [38, 39]. Our study found incidence to be slightly higher in children and AYA (Both AAIR = 0.04) compared to all adults age 40–65 years, but this difference was significant only in children (Adults:Children IRR = 1.32, p < 0.0001; Adults:AYA IRR = 1.11, p = 0.0968). Previous studies had also shown pineal region tumors to have a higher incidence in Asian populations as opposed to any other race and in males as opposed to females [38, 39]. This study, however, found that Black individuals (AAIR = 0.05 per 100,000 95% CI 0.04–0.05, White:Black IRR = 1.34, p < 0.0001) are more likely than any other races (Whites AAIR = 0.03; Other AAIR = 0.02) and females are more likely than males (Female AAIR = 0.04 per 100,000 95% CI 0.04–0.04; Male AAIR = 0.03 per 100,000 95% CI 0.03–0.03, IRR = 1.36, p < 0.0001) to be diagnosed with a pineal region tumor. A study conducted in 2009 estimated a 5-year survival of 65.1% in individuals diagnosed between 1973 and 2005 [38, 39]. Our results found a slightly higher relative five-year survival rate of 69.5% (62.7–75.3), which may be attributable to improved treatments for more recently diagnosed patients.

Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytomas

Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytomas are rare primary brain tumors. A study published in 2015 found these tumors occurred predominantly in the pediatric population. It was estimated that there were 1081 prevalent cases of these tumors in 2014 (AAPR = 0.16, 95% CI 0.14–0.17). The current study confirmed this finding revealing an AAIR of 0.03 per 100,000 (95% CI = 0.03–0.04) and 0.04 per 100,000 (95% CI 0.04–0.04) in children (Adults:children IRR = 1.98, p < 0.0001) and AYA (Adults:AYA IRR = 2.33, p < 0.0001), respectively. This is in contrast to AAIRs of 0.02 and 0.01 per 100,000 in all adults over age 40 years [40]. While a prior small study of seven individuals conducted in 2016 was composed predominately of females [41], our analysis found no difference in incidence based on sex (Male:Female IRR = 0.94, p = 0.3116). The 2015 study also showed a 5-year survival rate of 80.6%, which is similar to the 5-year RS of 76.2% presented in the current analysis [40]. Both studies stated that non-anaplastic pleomorphic xanthoastrocytomas tended to have more favorable outcomes than anaplastic pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma [40, 41]. The current analysis pooled non-anaplastic and anaplastic pleomorphic xanthoastrocytomas, which may have led to slightly lower survival rates. To our knowledge, this is the only study that has analyzed incidence, prevalence, and survival on a population level for pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma.

Primary CNS sarcoma

Primary CNS sarcomas are so rare that, to our knowledge, they have not been studied within the past 10 years to determine incidence, prevalence, and survival on a population level (all studies to date have been case studies or cohort studies). Prevalence of these tumors was 0.16 per 100,000 (95% CI 0.14–0.17, estimated to be 557 prevalent cases in 2014), and incidence was 0.01 per 100,000 (95% CI 0.06–0.07). The prognosis for individuals with primary CNS sarcomas was very poor with a 5-year survival rate of 5.6% and a 10-year survival rate of only 2.9%. White and non-Hispanic individuals were more likely to be diagnosed with a CNS sarcoma than other races (White:Black IRR = 0.67, p < 0.0001; White:Other IRR = 0.45, p < 0.0001) or Hispanics (non-Hispanics:Hispanics IRR = 0.78, p = 0.0004). Additionally, primary CNS sarcomas were significantly more common in adults age 65 + years (Adults:Older adults IRR = 2.35, p < 0.0001) and in males (Male:Female IRR = 0.58, p < 0.0001).

Ependymoma

Ependymomas are a relatively rare type of glial CNS tumor and constitute approximately 1.7% of all primary brain and other CNS tumors [1]. While these tumors affect all age groups, they are generally more common in children and adolescents than in older adults [42, 43]. These tumors had the second highest incidence of the 12 rare CNS histologies included in this analysis (after oligodendroglioma) but had the highest prevalence (13,294 estimated prevalent cases, AAPR = 4.11, 95% CI 4.03–4.18). The results from this study showed ependymomas to be most common in adults age 40–64 years (AAIR = 0.48 per 100,000 95% CI 0.46–0.49). While both oligodendroglioma and ependymoma have favorable long-term survival, it is likely that the predominance of ependymoma in children led to the increased prevalence of this histology. The incidence in children for this analysis was similar to the incidence rate of 0.26 per 100,000 found in a 2016 study of pediatric ependymomas [44]. Additionally, the results from previous studies reporting ependymomas as more common in males than females were confirmed in our study (Male AAIR = 0.41, 95% CI 0.40–0.42; Female AAIR = 0.32, 95% CI 0.31–0.22, IRR = 0.78, p < 0.0001). Our study also confirmed that ependymomas are more common in Whites (White AAIR = 0.39, 95% CI 0.38–0.40; Blacks AAIR-0.22, 95% CI 0.21–0.24, White:Black IRR = 0.58, p < 0.0001; Other AAIR = 0.26, 95% CI 0.25–0.28, Whites:Others IRR = 0.68, p < 0.0001) [43, 44]. A study conducted in 2018 found 5-year survival ranging from 50 to 77% [43]; however, this was lower than the 5-year RS of 83.9% (95% CI 82.2–85.4) found in the current study.

Due to their clinical importance and diversity, ependymomas were further analyzed by histology and site. The most predominant histology was ependymoma, NOS which includes tumors designated as grade II by WHO criteria (56% of all ependymoma), and the most predominant site was the spinal cord (49% of all sites). Additionally, ependymoma, NOS was most commonly found in the spinal cord (52% of all sites). Anaplastic ependymoma was most commonly found in the brain stem (17%), myxopapillary ependymoma and papillary ependymoma were most commonly found in the spinal cord (99% and 60% respectively), and subependymoma was mostly commonly found in the ventricle, NOS (47%). These findings are significant as recent molecular studies have shown that here are distinct subtypes of ependymoma based on specific molecular markers and therefore, each subgroup likely requires different treatment approaches such as surgical resection, radiation therapy, and targeted treatment or chemotherapy [42, 44].

This analysis represents the most complete and up-to-date reporting of patterns of incidence and survival for 12 selected rare brain and other CNS tumors in the US. All estimates are population-based. Estimates of incidence include 100% of the US population, while estimates of survival include data from ~ 28% of the population. To our knowledge, there are no prior studies that estimate the prevalence of these 12 selected rare CNS histologies. The absence of routine estimates of the prevalence of these diseases underscores an important knowledge gap that prevents longitudinal population assessments to both determine the impact of research efforts such as NCI-CONNECT on outcomes as well as the impact of each disease on public health in the US.

Cancer registry data provide the most complete data for characterizing patterns of cancer incidence and survival, but has several limitations including lack of central pathology review. All histologic classifications are assigned by treating physicians at the institutions where individuals are diagnosed, and as a result, they may vary from what would be assigned by a single pathologist. These histologic classifications, particularly glioma and embryonal histologies (including medulloblastoma and PNET), have changed over time and are becoming increasingly based on molecular features. As described above, the diagnosis of oligodendroglioma also now mandates specific molecular findings. This could lead to variation in how these histologies are defined both between institutions and over time. Cancer registries receive patient information from medical reports including pathology reports and other clinical records, but these data may not be recorded in all patients’ medical records, leading to missing data. Additionally, reporting laws for benign tumors changed in 2004 [21]. All of these factors affect the data received by CBTRUS and should be considered when reviewing our results.

Conclusion

The 12 groups of tumors reported here are extremely rare primary brain and other CNS tumors. It is because of their rarity, and for some their poor prognosis, that there is little (or even no) up-to-date statistics available to characterize these 12 tumor types; and there are no studies that compare all 12 rare tumor types to each other within one analysis. CBTRUS and NCI-CONNECT worked in collaboration with the aim of determining their incidence, prevalence, and survival by histology, age, race, ethnicity, and sex. The results of this study are meant to influence the research and clinical practice of these 12 specific rare brain tumors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Funding for CBTRUS has been provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) under Contract No. 2016-M-9030, the American Brain Tumor Association, The Sontag Foundation, Novocure, AbbVie, the Musella Foundation, National Brain Tumor Society, the Zelda Dorin Tetenbaum Memorial Fund, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) under Contract No. HHSN261201800176P, the Uncle Kory Foundation, and from private and in kind donations. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC or NCI. QTO is supported by a Research Training Grant from the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT; RP160097T).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical approval This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. This study was approved as an exempt study by the University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Informed consent This was a retrospective study using de-identified national cancer registries. Thus, formal consent was not required.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-019-03215-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Truitt G, Boscia A, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS (2018) CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2011–2015. Neuro Oncol 20:iv1–iv86. 10.1093/neuonc/noy131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Louis DNOH, Wiestler OD, Cavanee WK (eds) (2016) WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France [Google Scholar]

- 3.Surveillance E, and End Results (SEER) Program (2000–2014) SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 18 Regs Research Data + Hurricane Katrina Impacted Louisiana Cases, Nov 2016 Sub (2000–2014) <Katrina/Rita Population Adjustment> In: National Cancer Institute D, Surveillance Research Program; (ed). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fay MP (1999) Approximate confidence intervals for rate ratios from directly standardized rates with sparse data. Commun Stat Theory Methods 28:2141–2160. 10.1080/03610929908832411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fay MP, Tiwari RC, Feuer EJ, Zhaohui Z (2006) Estimating average annual percent change for disease rates without assuming constant change. Biometrics 62:847–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Surveillance Research Program National Cancer Institute SEER*Stat software. 8.3.5 edn.

- 7.Zhang AS, Ostrom QT, Kruchko C, Rogers L, Peereboom DM, Barnholtz-Sloan JS (2017) Complete prevalence of malignant primary brain tumors registry data in the United States compared with other common cancers, 2010. Neuro Oncol 19:726–735. 10.1093/neuonc/now252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.R Core Team (2018) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ostrom QT, Chen Y, MdB P, Ondracek A, Farah P, Gittleman H, Wolinsky Y, Kruchko C, Cohen ML, Brat DJ, Barnholtz-Sloan JS (2014) The descriptive epidemiology of atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors in the United States, 2001–2010. Neuro Oncol 16:1392–1399. 10.1093/neuonc/nou090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Hoff K, Hinkes B, Dannenmann-Stern E, von Bueren AO, Warmuth-Metz M, Soerensen N, Emser A, Zwiener I, Schlegel PG, Kuehl J, Fruhwald MC, Kortmann RD, Pietsch T, Rutkowski S (2011) Frequency, risk-factors and survival of children with atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumors (AT/RT) of the CNS diagnosed between 1988 and 2004, and registered to the German HIT database. Pediatr Blood Cancer 57:978–985. 10.1002/pbc.23236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woehrer A, Slavc I, Waldhoer T, Heinzl H, Zielonke N, Czech T, Benesch M, Hainfellner JA, Haberler C (2010) Incidence of atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors in children: a population-based study by the Austrian Brain Tumor Registry, 1996–2006. Cancer 116:5725–5732. 10.1002/cncr.25540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reyes-Botero G, Mokhtari K, Martin-Duverneuil N, Delattre JY, Laigle-Donadey F (2012) Adult brainstem gliomas. Oncologist 17:388–397. 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis ME (2018) Epidemiology and overview of gliomas. Semin Oncol Nurs 34:420–429. 10.1016/j.soncn.2018.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freeman CR, Farmer JP (1998) Pediatric brain stem gliomas: a review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 40:265–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tasic G, Repac N, Nikolic I, Bogosavljevic V, Scepanovic V, Janicijevic A, Eric-Nikolic A, Rasulic L (2017) Adult brainstem gliomas: retrospective analysis of 51 patients. Turk Neurosurg 27:558–562. 10.5137/1019-5149.Jtn.16488-15.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolff JE, Sajedi M, Brant R, Coppes MJ, Egeler RM (2002) Choroid plexus tumours. Br J Cancer 87:1086–1091. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dudley RW, Torok MR, Gallegos D, Liu AK, Handler MH, Hankinson TC (2015) Pediatric choroid plexus tumors: epidemiology, treatments, and outcome analysis on 202 children from the SEER database. J Neurooncol 121:201–207. 10.1007/s11060-014-1628-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rickert CH, Paulus W (2001) Tumors of the choroid plexus. Microsc Res Tech 52:104–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kshettry VR, Ostrom QT, Kruchko C, Al-Mefty O, Barnett GH, Barnholtz-Sloan JS (2015) Descriptive epidemiology of World Health Organization grades II and III intracranial meningiomas in the United States. Neuro Oncol 17:1166–1173. 10.1093/neuonc/nov069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harter PN, Braun Y, Plate KH (2017) Classification of meningiomas-advances and controversies. Chin Clin Oncol 6:S2. 10.21037/cco.2017.05.02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiemels J, Wrensch M, Claus EB (2010) Epidemiology and etiology of meningioma. J Neurooncol 99:307–314. 10.1007/s11060-010-0386-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dolecek TA, Dressler EV, Thakkar JP, Liu M, Al-Qaisi A, Villano JL (2015) Epidemiology of meningiomas post-Public Law 107–206: the Benign Brain Tumor Cancer Registries Amendment Act. Cancer 121:2400–2410. 10.1002/cncr.29379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenfield JP, Castaneda Heredia A, George E, Kieran MW, Morales La Madrid A (2016) Gliomatosis cerebri: a consensus summary report from the First International Gliomatosis cerebri Group Meeting, March 26–27, 2015, Paris, France. Pediatr Blood Cancer 63:2072–2077. 10.1002/pbc.26169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bruna J, Velasco R (2010) Gliomatosis cerebri. Neurologia 25:143–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Armstrong GT, Phillips PC, Rorke-Adams LB, Judkins AR, Localio AR, Fisher MJ (2006) Gliomatosis cerebri: 20 years of experience at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Cancer 107:1597–1606. 10.1002/cncr.22210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan MY, Teo WY, Seow WT, Tan AM (2007) Epidemiology, management and treatment outcome of medulloblastoma in singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore 36:314–318 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curran EK, Sainani KL, Le GM, Propp JM, Fisher PG (2009) Gender affects survival for medulloblastoma only in older children and adults: a study from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Registry. Pediatr Blood Cancer 52:60–64. 10.1002/pbc.21832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smoll NR, Drummond KJ (2012) The incidence of medulloblastomas and primitive neurectodermal tumours in adults and children. J Clin Neurosci 19:1541–1544. 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farwell JR, Dohrmann GJ, Flannery JT (1984) Medulloblastoma in childhood: an epidemiological study. J Neurosurg 61:657–664. 10.3171/jns.1984.61.4.0657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McNeil DE, Cote TR, Clegg L, Rorke LB (2002) Incidence and trends in pediatric malignancies medulloblastoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor: a SEER update. Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results. Med Pediatr Oncol 39:190–194. 10.1002/mpo.10121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khanna V, Achey RL, Ostrom QT, Block-Beach H, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, de Blank PM (2017) Incidence and survival trends for medulloblastomas in the United States from 2001 to 2013. J Neurooncol 135:433–441. 10.1007/s11060-017-2594-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Archer TC, Mahoney EL, Pomeroy SL (2017) Medulloblastoma: molecular classification-based personal therapeutics. Neurotherapeutics 14:265–273. 10.1007/s13311-017-0526-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Becker LE, Hinton D (1983) Primitive neuroectodermal tumors of the central nervous system. Hum Pathol 14:538–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van den Bent MJ, Reni M, Gatta G, Vecht C (2008) Oligoden-droglioma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 66:262–272. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Achey RL, Khanna V, Ostrom QT, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS (2017) Incidence and survival trends in oligodendrogliomas and anaplastic oligodendrogliomas in the United States from 2000 to 2013: a CBTRUS Report. J Neurooncol 133:17–25. 10.1007/s11060-017-2414-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lau CS, Mahendraraj K, Chamberlain RS (2017) Oligodendrogliomas in pediatric and adult patients: an outcome-based study from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Result database. Cancer Manag Res 9:159–166. 10.2147/cmar.s117799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goel NJ, Abdullah KG, Lang SS (2018) Outcomes and prognostic factors in pediatric oligodendroglioma: a population-based study. Pediatr Neurosurg 53:24–35. 10.1159/000481458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zaazoue MA, Goumnerova LC (2016) Pineal region tumors: a simplified management scheme. Childs Nerv Syst 32:2041–2045. 10.1007/s00381-016-3157-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Hussaini M, Sultan I, Abuirmileh N, Jaradat I, Qaddoumi I (2009) Pineal gland tumors: experience from the SEER database. J Neurooncol 94:351–358. 10.1007/s11060-009-9881-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ida CM, Rodriguez FJ, Burger PC, Caron AA, Jenkins SM, Spears GM, Aranguren DL, Lachance DH, Giannini C (2015) Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma: natural history and long-term follow-up. Brain Pathol 25:575–586. 10.1111/bpa.12217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rutkowski MJ, Oh T, Niflioglu GG, Safaee M, Tihan T, Parsa AT (2016) Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma with anaplastic features: retrospective case series. World Neurosurg 95:368–374. 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.07.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu J, Armstrong TS, Gilbert MR (2016) Biology and management of ependymomas. Neuro Oncol 18:902–913. 10.1093/neuonc/now016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gerstner ER, Pajtler KW (2018) Ependymoma. Semin Neurol 38:104–111. 10.1055/s-0038-1636503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vitanza NA, Partap S (2016) Pediatric ependymoma. J Child Neurol 31:1354–1366. 10.1177/0883073815610428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.