Abstract

Reliable and quantitative assessment of corneal biomechanics is important for the detection and treatment of corneal disease. The present study evaluates the repeatability and reproducibility of a novel optical coherence tomography (OCT)-based elastography (OCE) method for in vivo quantification of corneal natural frequency in 20 normal human eyes. Sub-micron corneal oscillations were induced by repeated low-force (13 Pa) microliter air pulses at the corneal apex and were observed by common-path phase-sensitive OCT imaging adjacent to a measurement region of 1–6.25 mm2. Corneal natural frequencies were quantified using a single degree of freedom model based on the corneal oscillations. Corneal natural frequencies ranged from 234 to 277 Hz (coefficient of variation: 3.2%; n = 286 for a 2.5 × 2.5 mm2 area; time: 28.6 s). The same natural frequencies can be acquired using a smaller sampling size (n = 9 for 1 mm2) and a shorter time (0.9 s). Spatial distribution and local changes in natural frequencies can be distinguished using denser sampling (e.g., 26 × 41 points for 2.5 × 5 mm2). This novel optical method demonstrates highly repeatable and reliable in vivo measurements of human corneal natural frequencies. While further studies are required to fully characterize anatomical and structural dependencies, this method may be complementary to the current OCE methods used to estímate Young’s modulus from strain- or shear-wave-based measurements for the quantitative determination of corneal biomechanics.

Keywords: Optical Coherence Tomography, Optical Coherence Elastography, Corneal Biomechanics, Natural Frequency, Micro Stimulation

1. Introduction

The human cornea maintains ocular shape and provides approximately two-thirds of the eye’s total refractive power. Corneal biomechanical properties, such as elasticity and viscosity, are inherently tied to corneal anatomy, corneal health, and vision quality (Kling and Hafezi, 2017; Ruberti et al., 2011). Morphological changes of the cornea are usually accompanied by biomechanical changes (Li et al., 2004; Maguire and Bourne, 1989; Rabinowitz, 1995). Keratoconus, a typical structurally degenerative disease, is characterized by corneal thinning and ectasia (Rabinowitz, 1998), and can cause a significant reduction of mechanical stability (Lu et al., 2013; Scarcelli et al., 2014). Riboflavin/UVA corneal collagen cross-linking treatment is widely used for the treatment of keratoconus progression by increasing the corneal rigidity (Jankov II et al., 2010; Meek and Hayes, 2013; Spoerl et al., 1998). Refractive surgery, such as Laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) and small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) (Kim et al., 2019; Pallikaris et al., 1990) on myopic eyes can also reduce the corneal stiffness (Dupps Jr and Wilson, 2006; Ortiz et al., 2007; Schmack et al., 2005; Shah and Laiquzzaman, 2009; Shetty et al., 2017); while corneal stiffness can, in turn, influence the predictability, stability, and safety of refractive surgery (Dupps Jr and Wilson, 2006; Guirao, 2005; Klein et al., 2006; Roberts, 2005). Therefore, characterization of corneal biomechanics is useful for diagnosing and classifying keratoconus progression (Scarcelli et al., 2014) for pre-operative identification of refractive surgery candidates to avoid complications, such as post-LASIK ectasia, and for prediction and evaluation of treatment outcomes (Binder et al., 2005). However, clinical methods for precisely accessing corneal biomechanical properties are currently limited.

Optical coherence elastography (OCE) (Schmitt, 1998) is a rapidly developing method for quantitative measurement of soft tissue biomechanics. OCE is composed of a loading system to induce tissue deformation and an optical coherence tomography (OCT) to detect the tissue response. Tissue biomechanical properties can be reconstructed based on elastic wave propagation or strain distribution in response to mechanical stimulation. Descended from ultrasound and MRI-based elastography techniques, shear wave-based approaches have related the shear wave velocity to the shear modulus or Young’s modulus, and have become the most common method used in OCE applications (Wang and Larin, 2014). However, the complex tissue geometry (Singh et al., 2016; Vantipalli et al., 2018), heterogeneous tissue structure, air/fluid/tissue boundary conditions (Han et al., 2015b), and/or intraocular pressure (Singh et al., 2016) can each influence and confound observations and interpretations of these velocity measurements (Pelivanov et al., 2019). Previous work has illustrated some of these dependencies by showing that mechanical waves traveling along the corneal surface contain multiple high-order dispersive and complex Rayleigh-Lamb components that cannot be described precisely using the simple Rayleigh waves (Han et al., 2015a). Our previous work on the impact of physiological movements, including respiration, heartbeat and ocular pulsations, showed that these factors could also induce measurement uncertainty and variability. We found that the average coefficient of variation for corneal displacement measurements was approximately 17% when the induced displacements were −0.2 to −0.8 pm in amplitude (Lan et al., 2020a). The corneal surface wave speeds ranged from 2.4 to 4.2 m/s for 18 eyes with an average coefficient of variation up to 19.3 % (Lan et al., 2021). Therefore, developing more robust and reliable measurement and reconstruction methods is necessary to further advance the potential utility of clinical corneal OCE imaging (Larin and Sampson, 2017).

We recently presented an alternative and complementary method for characterizing corneal properties using natural frequency (Lan et al., 2020b), which is the frequency tissue tends to oscillate when disturbed. Natural frequency oscillation in response to the excitation force is closely related to tissue elastic properties. In a simple elastic model, the natural frequency is linearly related to the square root of Young’s modulus (Lan et al., 2020b). The new OCE approach benefits from sub-nanometer detection sensitivity, which is achieved using common-path OCT detection combined with a low-force highly-focused microliter air-pulse sample stimulation normal to the tissue surface (Lan et al., 2017). This enables a more uniform wave propagation pattern in radial directions (Lan and Twa, 2019). In this study, we evaluated measurement repeatability and reproducibility using the novel OCE approach for in vivo assessment of human corneal natural frequencies in 20 healthy human eyes. Physiological eye motions with distinctly low frequency (~ 0.1 to 1 Hz) motion features in the lateral direction were subtracted using an iris-tracking camera and in the axial direction using the OCT signal (Lan et al., 2021; Lan et al., 2020a). Sub-micrometer amplitude corneal oscillations are induced by perpendicular air-pulse stimulations and observed using high-sensitivity common-path OCT detection. The corneal natural frequencies can be quantified from the damped corneal oscillation process using a single degree of freedom mechanical model. Corneal biomechanical responses were characterized spatially. The measurement precisión, repeatability, and local Variation of corneal natural frequencies were evaluated using several different measurement protocols as described below. Although the corneal natural frequency is also determined by many other factors, such as corneal mass, shape, intraocular pressure and boundary conditions, the highly repeatable measurement of corneal natural frequencies from sub-micron corneal oscillations could provide a new approach, complementary to other OCE methods, for in vivo characterization of corneal tissue properties. This novel method also has the potential to further the clinical application of OCE-based methods for quantitative characterization of corneal biomechanical properties.

2. Methods

2.1. Human subjects

The research protocol was approved by the institutional review board and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants after explanation of the study and the possible consequences of their participation. Each subject signed the consent form prior to enrollment. Ten subjects (four females and six males) were enrolled in the study. The ages were 20.3 ± 10.0 years (mean ± SD), and the intraocular pressures were 15.2 ± 3.5 mmHg. All subjects had no history of ocular disease or surgery or any systemic condition or medication that affected corneal structure or function.

2.2. Phase-Sensitive Corneal OCE system

A home-built prototype corneal OCE system was upgraded from the common-path OCE system (Lan et al., 2017) by making it more suitable for in vivo human eye measurement (Lan et al., 2021; Lan et al., 2020a), as shown in Fig. 1A. In brief, a fixation target and a camera were used to locate and monitor the corneal position. A focused (150 pm diameter), low-pressure (0–60 Pa) and short duration (as small as ~1 ms) air pulse was normally deliveredto the tissue through a solenoid valve attached to an air cannula. This generated a wide range of frequency excitation (0 to 1 kHz) along with detectable small amplitude corneal tissue displacements and oscillations. This microliter air-pulse stimulator provides far less mechanical stimulation pressure, over a smaller area, and for less time compared to clinical air-puff based instruments (e.g., 3 mm × 3 mm; 70–300 kPa; 10–30 ms) such as the Ocular Response Analyzer (Reichert Inc., Buffalo, NY), the CorVis ST (OCULUS, Inc. Arlington, WA), and other similar air-puff based OCE systems (Alonso-Caneiro et al., 2011; Jiménez-villar et al., 2019; Maczynska et al., 2019).

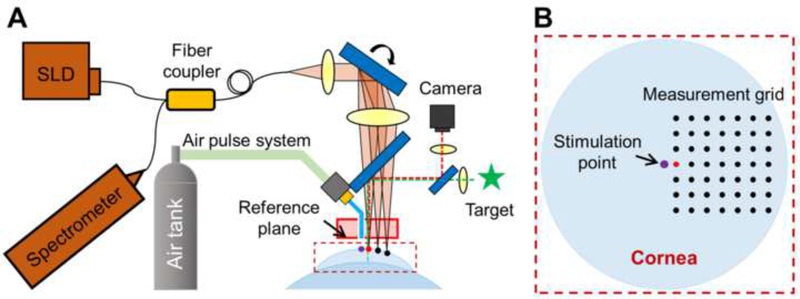

Fig. 1.

Schematic of corneal optical coherence elastography (OCE). (A) A corneal OCE system was combined with a fixation target and a camera to monitor the measured area, an air-pulse stimulator to provide localized tissue excitation, and a common-path OCT to quantify human corneal natural frequency from the resulting corneal oscillation behavior. SLD: 845 nm superluminescent laser diode; CL: collimating lens; TL: telecentric focusing lens; SL: scan lens (two Galvo scanners, only one is shown here for simplicity). (B) Demonstration of the geometric relation between the stimulation point and the measurement points on cornea. The red point in the measurement grid is the nearest point from the stimulation.

The detection system was comprised of an 840 nm spectral domain common-path OCT system, which was synchronized to the mechanical stimulation to record the dynamic mechanical responses of the cornea (Fig. 1A). A detailed description of this home-built OCE system was reported in our previous publications (Lan et al., 2020a; Lan et al., 2017). Fig. 1B illustrates the geometric distribution of the stimulation point and the measurement points on the corneal surface. The red point in the measurement grid is the nearest point from the stimulation point (purple). The induced small-magnitude tissue displacement of a measurement point can be calculated by the phase change from the complex component of the OCT interferograms. The observed unwrapped phase change, Φ(t), represents displacement, y(t), in the axial direction:

| (1) |

where λ0 is the center wavelength, t is time, and n is the refractive index (Song et al., 2013b). Phase signals are very stable in both the depth and the scan directions, which are 3.71 ± 0.63 milliradians (0.25 ± 0.04 nm) over 0 to 6.66 mm in depth, and 3.05 ± 0.48 milliradians (0.21 ± 0.03 nm) over a scan range of ±5 mm (depth: 1.65 mm). The superior and uniform phase stability is ideal for volumetric tissue elasticity measurements (Lan et al., 2017).

2.3. M-mode and M-B Mode measurement protocols

Measurements were performed using M-mode and M-B mode scan protocols (Song et al., 2013a; Song et al., 2013b; Wang and Larin, 2014). The geometric relationship between the stimulation point and the measurement points on the cornea is shown in Fig. 1B, where the distance from the nearest measurable point (red) to the stimulation point is 0.125 mm. For a stimulation event, corneal displacement of a certain corneal location was acquired using M-mode OCT detection in which the axial scans (A-scans) were measured over time at the same location. The M-B scan protocol was then used to map the corneal spatio-temporal dynamics by utilizing multiple tissue excitations to sequentially collect repetitive A-scans (M-mode scans) at the corresponding measurement positions on the corneal surface.

2.4. Natural frequency quantification using the single degree of freedom model

The single degree of freedom model was used previously to describe this tissue damping oscillation process using the dominant resonant frequency (Lan et al., 2020b). The response oscillation can be described as three different regimes based on the value of damping ratio (ε): critical-damping (damping ration ε = 1), under-damping (0 ≤ ε < 1), and over-damping (ε > 1). Although the human cornea with multiple layers and interfaces is actually a multiple degrees of freedom oscillation system, the single degree of freedom analytical method can be used to access the dominant oscillation features. Fig. 2A shows a typical corneal displacement profile, including an initial surface displacement that is driven by the excitation force, a recovery response period where the displacement returns from the maximum negative value to zero for the first time, and an obviously under-damped conditional corneal oscillation (red window). The equation of motion to describe the free response of a single degree of freedom system is as follows (Adie et al., 2010; Lan et al., 2020b):

| (2) |

where fn is the natural frequency in the single degree of freedom system, A is the maximum oscillation amplitude, and φ is a phase value. A damped natural frequency (fd) is defined as , and can be acquired directly as the dominant resonant frequency via fast Fourier transform (FFT).

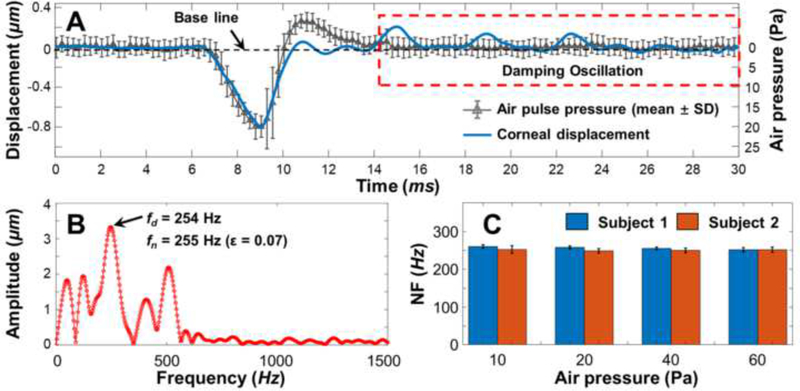

Fig. 2.

Evaluation of the corneal natural frequency (NF) measurement repeatability using the Single Degree of Freedom (SDOF) method in two healthy human subjects (right eye; measurement distance: 0.125 mm from corneal apex; stimulation: 10–60 Pa, 10 Hz). (A) Typical corneal displacement profiles in response to the air-pulse stimulation (20 Pa) in the time domain. The air pulse profile was demonstrated as the means and standard deviations (SDs) from 40 repeat measurements. The damping corneal oscillatory motion (in red window) can be used for the SDOF analysis based on Equation 2. (B) FFT of the corneal damping oscillations. The damped natural frequencies were in the range of ~ 0–500 Hz. The dominant natural frequency fn was calculated as 255 Hz. (C) Bar plots (mean ± SD) of the measured corneal NF values (n = 5 for each measurement).

2.5. In-vivo corneal natural frequency measurement procedure

During OCE imaging, a subject sat in a chair, rested the chin on a chin rest with the forehead against a headband, and focused the eye on a visual target. The lateral positions of the cornea were monitored by an iris-tracking camera, and the axial physiological movements of the corneal surface were separated from the induced corneal displacements due to the distinctly low frequency (~ 0.1 to 1 Hz) motion features. The corneal apex was positioned at an axial distance of 1.5 ± 0.5 mm from the reference plane. The microliter air pulse stimulator delivered the air force at the corneal apex, and the OCT beam was scanned at the corneal surface to detect the corneal response at different locations (Fig. 1B). The duration of the air pulse was ~5 ms, and the time between two successive excitations was 100 ms. The corneal surface displacement of each point was recorded 5 ms prior to tissue excitation and lasted for 30 ms with an A-scan sampling rate of 20 kHz. The surface displacement was converted from the phase signal based on Eq. (1), and the natural frequency values were estimated based on Eq. (2). The performance of corneal natural frequency measurements was evaluated using both an M-mode at a fixed corneal position with various stimulation pressures (10–60 Pa, 10 Hz) and using different M-B scan protocols that covered measurement regions of 1 to 6.25 mm2 and measurement times of 0.9 to 28.6 s (stimulation: 10–60 Pa, 10 Hz).

3. Results

3.1. Repeatability evaluation using various stimulation pressures

Measurement repeatability of human corneal natural frequencies was compared in two human subjects at a fixed measurement distance (0.125 mm from the stimulation) when the stimulation pressures were in the range of 10–60 Pa. The typical temporal air-pulse profiles (20 Pa) are shown in Fig. 2A, and were comprised of 40 repeated measurements using an analog high-sensitivity pressure transducer (STS ATM.1ST Precision Pressure Transmitter, PMC Engineering, Danbury, CT) coupled to a data acquisition system (PowerLab 8/35, ADInstruments Inc., Colorado Springs, CO). The induced corneal displacements were overlaid with the airpulse profiles, and the oscillation features (red window) were characterized via FFT. As shown in Fig. 2B, the resonant frequencies were in the range of 0 – 500 Hz and the dominant resonant frequency (fd) was 254 Hz. The dominant corneal natural frequency was 255 Hz (ε = 0.07). Fig. 2C shows the means and standard deviations (SDs) for the measured natural frequencies, which were 257 ± 4 Hz and 251 ± 5 Hz, respectively, for for each of the subjects under the stimulation pressures of 10 Pa to 60 Pa. The single degree of freedom method analysis showed good repeatability for measurement of human corneal natural frequency (SD: ~ 3–5 Hz, mean coefficient of variation: 1.8%) for various stimulation forces.

3.2. Spatial characterization using a dense M-B sampling

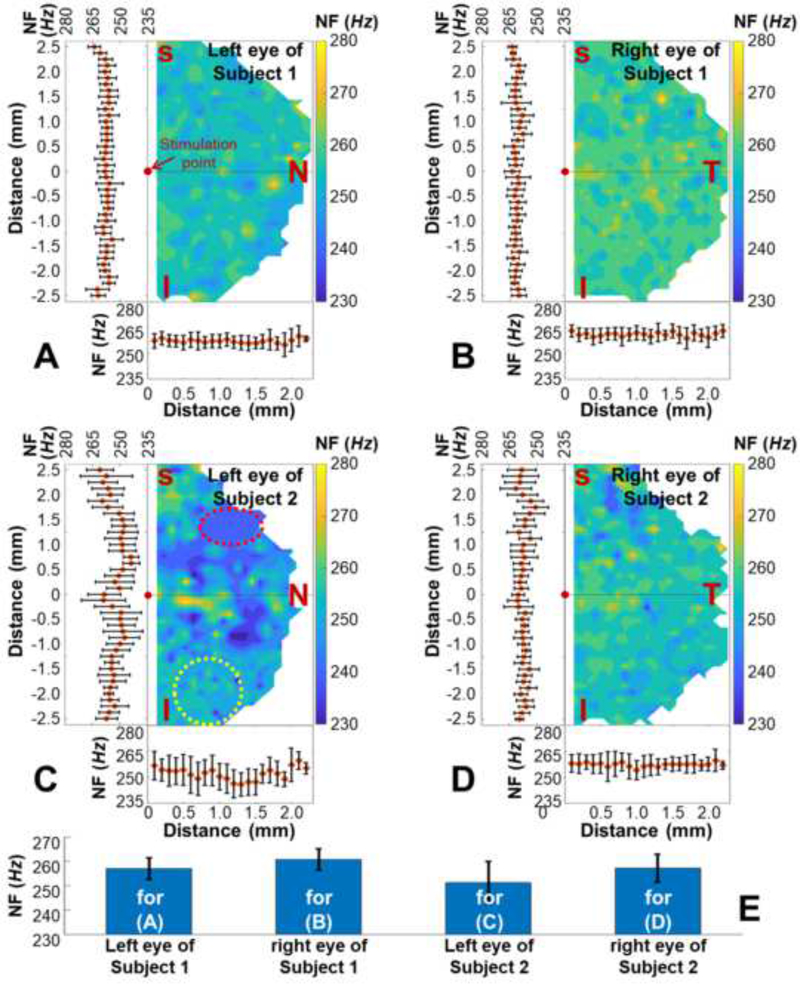

The corneal natural frequencies were measured spatially in the left and right corneas from two human subjects, as shown in Fig. 3. The air pulse stimulation pressure was 13 Pa. The measurement covered an approximately 2.5 mm × 5 mm (26 × 41 points) hemispherical area, and the total data acquisition time was 106.6 s for each eye. The edge of the field was undetectable due to a limited diameter (5 mm) of the reference plate (Fig. 1A). Figs. 3(A–D) show the 2-D plots of the corneal natural frequency distributions as well as the means and SDs in both the horizontal and the vertical directions. The corneal natural frequencies were uniformly distributed in Figs. 3(A, B, and D), and varied slightly in Fig. 3C. The local natural frequencies in the selected red-dash circle (241 ± 6 Hz) were smaller than those in the yellow-dash circle (260 ± 8 Hz). Fig. 3E shows all of the measured natural frequencies for Figs. 3(A–D), which were 257 ± 5 Hz, 261 ± 4 Hz, 251 ± 9 Hz, and 257 ± 6 Hz (mean ± SD).

Fig. 3.

Natural frequency (NF) characterization for ~ 2.5×5 mm2 area (26 × 41 points; total time: 106.6 s) on the left and right corneas from two human subjects (stimulation: 13 Pa, 10 Hz). Panels (A)–(D) show the 2-D plots of the NF distributions and the corresponding means and SDs in the horizontal and the vertical directions. (E) Bar plots (means ± SDs) for the NF values corresponding to Panel(A) – Panel(D).

3.3. Reproducibility evaluation using M-B mode protocols

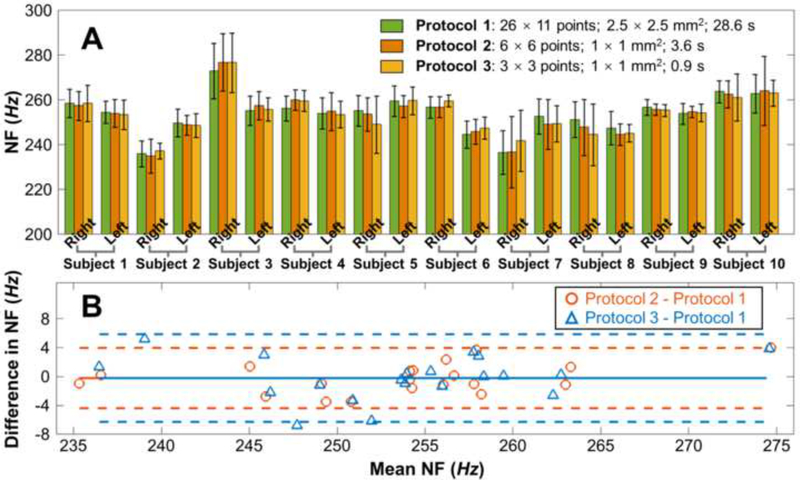

Corneal natural frequency measurement reproducibility was assessed in 20 eyes from 10 human subjects among three experimental protocols that covered different measurement areas (from 2.5 × 2.5 mm2 to 1 × 1 mm2), utilized different sampling points (from 26 × 11 points to 3 × 3 points), and different measurement times (from 28.6 s to 0.9 s). The air pulse stimulation pressure was 13 Pa for all protocols. Fig. 4A shows the comparison results (means ± SDs). The measured natural frequencies ranged from 234 Hz to 277 Hz for the 20 corneas. There were no obvious differences in the measured natural frequencies using these three protocols. The mean Coefficients of Variation for Protocols 1–3 were 3.2%, 2.9%, and 3.1%, respectively. Bland-Altman (mean vs. difference) analysis showed good agreement among Protocols 1–3 (Fig. 4B), such that the values of the means ± 1.96 SD were −0.3 ± 4.1 Hz (Protocols 2 and 1) and −0.2 ± 6.2 Hz (Protocols 3 and 1).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of corneal natural frequencies (NF) among three protocols with different measurement areas (from 2.5 × 2.5 mm2 to 1 × 1 mm2) and time (from 28.6 s to 0.9 s) using the Single Degree of Freedom (SDOF) method (stimulation: 13 Pa, 10 Hz). (A) Bar plots (mean ± SD) for the measured natural frequencies for the three protocols on 20 eyes from 10 human subjects. (B) A comparison of residual error (mean vs. difference) shows good agreement among 3 protocols, indicating no distinct bias among protocols and similar 95% limits of agreements. The means ± 1.96 SD were −0.3 ± 4.1 Hz (Protocol 2 - Protocol 1) and - 0.2 ± 6.2 Hz (Protocol 3 - Protocol 1), respectively.

4. Discussion

In the current study, a novel corneal OCE approach was used to obtain highly repeatable, reproducible, and spatially resolved in vivo human corneal natural frequency quantification. This work was built upon our common-path spectral domain OCE system (Lan et al., 2017) and a simple single degree of freedom model (Lan et al., 2020b). The superior and uniform phase stability (0.2–0.3 nm) at different scanning depths and locations enabled the M-B scan mode and volumetric corneal elasticity measurement. Recently, this common-path technique was successfully applied in a swept source based OCE system (Li et al., 2020).

In Fig. 2, the corneal natural frequencies were precisely quantified (Coefficient of Variation: 1.8 %) and were independent of the driving forces, which ranged from 10 Pa to 60 Pa. This result is consistent with our phantom measurements with stimulation pressures of 4–32 Pa (Lan et al., 2020b). The corneal natural frequency measurements were more repeatable and reliable than the corneal displacement measurements (Coefficient of Variation: 17%) and the corneal surface wave speed measurements (Coefficient of Variation: 19.3%) presented in our previous in vivo study (Lan et al., 2021; Lan et al., 2020a). High measurement repeatability and precisión are advantages of the natural frequency measurement in the current study and may advance the use of OCE methods for clinical measurement of corneal properties.

The variations in natural frequency values were very small in healthy corneas, as shown in the 20 healthy eyes in Fig. 4A. The mean Coefficient of Variation was only about 3% for the 2.5 × 2.5 mm2 measurement field; therefore, the average corneal natural frequency value could be estimated using a smaller sampling size and shorter measurement time. As shown in Fig. 4B, there was excellent reproducibility and agreement (means ± 1.96 SD: −0.2 ± 6.2 Hz) between the 26 × 11-point measurement (28.6 s) and the 3 × 3-point measurement (0.9 s). Reducing the measurement time could provide a more comfortable measurement experience for patients, as well as reduce measurement artifacts caused by eye-motion.

Even though the spatial variation of measured natural frequencies was small for different corneal positions, as shown Figs. 3(A, B, and D), spatially localized natural frequency variations were also observed in Fig. 3C. It should be noted that only the dominant natural frequency was considered in the single degree of freedom method. Because the human cornea is acomprised of heterogeneous tissue with a complex geometry, which has many interfaces and thin-layers (Meek, 2009), it acts as a multiple degrees of freedom oscillation system containing multiple natural frequency components, as demonstrated in Fig. 2C. The spatial variations in the dominant corneal natural frequencies reflected the changes of the oscillation amplitudes at different measurement positions, which may occur due to the subtle differences of local stiffness or corneal geometry. This result is consistent with our previous work, which used the relaxation model to distinguish spatial natural frequency distributions on heterogeneous agar phantoms and ex vivo corneas after riboflavin/UVA corneal collagen cross-linking (Singh et al., 2017). Detection of subtle changes in natural frequency distributions might be useful for the diagnosis of corneal disease (e.g., keratoconus) and for evaluation of corneal treatment (e.g., corneal cross-linking, refractive surgery).

Previous OCE methods have been developed to quantify elasticity and viscosity, such as the Young’s modulus estimation method using strain- (Kennedy et al., 2014) or shear-wave-based OCE (Song et al., 2013a), and the viscosity quantification method using the modified Rayleigh-Lamb frequency equation (Han et al., 2015a) or the kinematic model based on the tissue relaxation process (Wu et al., 2015). The highly reliable and repeatable measurement of natural frequency using OCE in the current study is a good complement to previous methods and has the potential for clinical development. First, the measurement of corneal natural frequency could be used to detect and quantify subtle morphological changes in the cornea caused by corneal disease (e.g., keratoconus and ectasia) or refractive surgery. Second, corneal natural frequency measurements could be used to detect elevated intraocular pressure and are potentially useful for early detection of ocular tissue changes caused by glaucoma. This in vivo human corneal natural frequency measurement study is preliminary and only focused on healthy human subjects with no history of corneal disease. Future studies on patients with ocular disease (e.g., keratoconus or glaucoma), myopic degeneration, or that have undergone surgical interventions are needed to understand the clinical utility of this imaging method for detection and classification of corneal abnormalities, and for treatment evaluation. Although the fundamental principles and spatio-temporal measurement scales differ considerably, it may be useful to compare OCE measurements to the clinical biomechanical parameters derived from the Ocular Response Analyzer (Luce, 2005) and the CorVis ST (Hon and Lam, 2013).

It should be noted that this corneal OCE is a prototype system, the use of OCE for the measurement of corneal natural frequencies from sub-micrometer to sub-nanometer tissue oscillations is recent work, and the reliable analytical model for determining corneal Young’s modulus from the observed natural frequencies is still needed. The current field of view is approximately 2.5 mm × 5 mm (Fig. 3), and is limited by the clear diameter (5 mm) of the reference plate and the position of the stimulation device (Fig. 1A), thus future work will also focus on continual improvement of the corneal OCE system and the imaging technique. One goal is development of an OCE imaging technique with large enough field of view (e.g., >12 mm) to map the natural frequency distribution of the whole cornea or whole eye. Precise measurement of the air-pulse profile, both in the temporal domain and the spatial domain, still presents a great technical challenge. Calibrating the spatial distribution of the air-pulse was not yet possible because the stimulation pressure was too low (e.g., 13 Pa), the time duration was too short (e.g., < 4 ms), and the stimulation area (150 μm) was too small. In addition, the natural frequency is comprehensively affected by many factors including not only the tissue biomechanics (such as Young’s modulus), but also the mass, shape, intraocular pressure and tissue boundary conditions. Our previous studies showed that, as expected, the natural frequencies decreased as the thicknesses/masses of agar phantoms increased (Lan et al., 2020b). Results from these studies suggest that mass and sample geometry may also be important factors that influence in vivo measurements as well; though this remains to be seen. Future detailed studies investigating corneal natural frequencies and their dependence on other ocular structural parameters (e.g., corneal center thickness, intraocular pressure, corneal topography, etc.) are needed to better understand the limitations and potential clinical use of these natural frequency measurements. We plan to develop more advanced analytical methods and more complex finite element eye models that comprise the shape and multi-layered structure, intraocular pressure, boundary conditions, and tissue biomechanics. Developing such theoretical models and investigating the relationships between natural frequency and the above factors could help develop methods to better characterize corneal biomechanical properties using high repeatable and reproducible natural frequency measurements.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (61975030; to GL), Department of Education of Guangdong Province (2020KTSCX130; to GL), Guangdong Pearl River Talents Program (2019ZT08Y105; to GL), Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Intelligent Micro-Nano Optoelectronic Technology Joint Laboratory (2020B1212030010), National Eye Institute (R01-EY022362; to MDT) and National Eye Institute (P30 EY07551 and P30 EY003039). We thank Yicheng Wang for assistance with figure plots.

Conflict of interest statement

Michael Twa, Kirill Larin, and Salavat Aglyamov are supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Eye Institute (NIH/NEI) R01-EY022362, P30EY07551, and P30EY003039. Gongpu Lan is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) 61975030, and by start-up/platform funds from Foshan University (Gg07071, Gs06001, and Gs06019).

The authors declare no conflicts of interest associated with this publication, and there has been no financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adie SG, Liang X, Kennedy BF, John R, Sampson DD, Boppart SA, 2010. Spectroscopic optical coherence elastography. Opt. Express 18, 25519–25534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Caneiro D, Karnowski K, Kaluzny BJ, Kowalczyk A, Wojtkowski M, 2011. Assessment of corneal dynamics with high-speed swept source Optical Coherence Tomography combined with an air puff system. Opt. Express 19, 14188–14199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder PS, Lindstrom RL, Stulting RD, Donnenfeld E, Wu H, McDonnell P, Rabinowitz Y, 2005. Keratoconus and corneal ectasia after LASIK. J. Refract. Surg 21, 749–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupps WJ Jr, Wilson SE, 2006. Biomechanics and wound healing in the cornea. Exp. Eye Res 83, 709–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guirao A, 2005. Theoretical elastic response of the cornea to refractive surgery: risk factors for keratectasia. J. Refract. Surg 21, 176–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Z, Aglyamov SR, Li J, Singh M, Wang S, Vantipalli S, Wu C, Liu C, Twa MD, Larin KV, 2015a. Quantitative assessment of corneal viscoelasticity using optical coherence elastography and a modified Rayleigh–Lamb equation. J. Biomed. Opt 20, 020501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Z, Li J, Singh M, Aglyamov SR, Wu C, Liu CH, Larin KV, 2015b. Analysis of the effects of curvature and thickness on elastic wave velocity in cornea-like structures by finite element modeling and optical coherence elastography. Appl. Phys. Lett 106, 233702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hon Y, Lam AKC, 2013. Corneal Deformation Measurement Using Scheimpflug Noncontact Tonometry. Optom. Vis. Sci 90, E1–E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankov II MR, Jovanovic V, Nikolic L, Lake JC, Kymionis G, Coskunseven E, 2010. Corneal collagen cross-linking. Middle East Afr. J. Ophthalmol 17, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-villar A, Mączyńska E, Cichański A, Wojtkowski M, Kałużny BJ, Grulkowski I, 2019. High-speed OCT-based ocular biometer combined with an air-puff system for determination of induced retraction-free eye dynamics. Biomed. Opt. Express 10, 3663–3680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy KM, Es’haghian S, Chin L, McLaughlin RA, Sampson DD, Kennedy BF, 2014. Optical palpation: optical coherence tomography-based tactile imaging using a compliant sensor. Opt. Lett 39, 3014–3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TI, Alió Del Barrio JL, Wilkins M, Cochener B, Ang M, 2019. Refractive surgery. Lancet 393, 2085–2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein SR, Epstein RJ, Randleman JB, Stulting RD, 2006. Corneal ectasia after laser in situ keratomileusis in patients without apparent preoperative risk factors. Cornea 25, 388–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kling S, Hafezi F, 2017. Corneal biomechanics - a review. Ophthal. Physl. Opt 37, 240–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan G, Aglyamov SR, Larin KV, Twa MD, 2021. In Vivo Human Corneal Shear-wave Optical Coherence Elastography. Optom. Vis. Sci 98, 58–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan G, Gu B, Larin KV, Twa MD, 2020a. Clinical corneal optical coherence elastography measurement precision: effect of heartbeat and respiration. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol 9, 3–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan G, Larin KV, Aglyamov S, Twa MD, 2020b. Characterization of natural frequencies from nanoscale tissue oscillations using dynamic optical coherence elastography. Biomed. Opt. Express 11, 3301–3318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan G, Singh M, Larin KV, Twa MD, 2017. Common-path phase-sensitive optical coherence tomography provides enhanced phase stability and detection sensitivity for dynamic elastography. Biomed. Opt. Express 8, 5253–5266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan G, Twa MD, 2019. Theory and design of Schwarzschild scan objective for Optical Coherence Tomography. Opt. Express 27, 5048–5064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larin KV, Sampson DD, 2017. Optical coherence elastography - OCT at network in tissue biomechanics [invited]. Biomed. Opt. Express 8, 1172–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Rabinowitz YS, Rasheed K, Yang H, 2004. Longitudinal study of the normal eyes in unilateral keratoconus patients. J. Ophthalmol 111, 440–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Moon S, Chen JJ, Zhu Z, Chen Z, 2020. Ultrahigh-sensitive optical coherence elastography. Light Sci. Appl 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Vitart V, Burdon KP, Khor CC, Bykhovskaya Y, Mirshahi A, Hewitt AW, Koehn D, Hysi PG, Ramdas W.D.J.N.g., 2013. Genome-wide association analyses identify multiple loci associated with central corneal thickness and keratoconus. Nature genetics 45, 155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luce DA, 2005. Determining in vivo biomechanical properties of the cornea with an ocular response analyzer. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg 31, 156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maczynska E, Rzeszewska-Zamiara J, Villar AJ, Wojtkowski M, Kaluzny BJ, Grulkowski I, 2019. Air-Puff-Induced Dynamics of Ocular Components Measured with Optical Biometry. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 60, 1979–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire LJ, Bourne WM, 1989. Corneal topography of early keratoconus. Am. J. Ophthalmol 108, 107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meek KM, 2009. Corneal collagen—its role in maintaining corneal shape and transparency. Biophys. Rev 1, 83–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meek KM, Hayes S, 2013. Corneal cross - linking – a review. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt 33, 78–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz D, Piñero D, Shabayek MH, Arnalich-Montiel F, Alió JL, 2007. Corneal biomechanical properties in normal, post-laser in situ keratomileusis, and keratoconic eyes. J. Cataract Refract. Surg 33, 1371–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallikaris LG, Papatzanaki ME, Stathi EZ, Frenschock O, Georgiadis A, 1990. Laser in situ keratomileusis. Lasers Surg. Med 10, 463–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelivanov I, Gao L, Pitre J, Kirby MA, Song S, Li D, Shen TT, Wang RK, O’Donnell M, 2019. Does group velocity always reflect elastic modulus in shear wave elastography? J. Biomed. Opt 24, 076003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz YS, 1995. Videokeratographic indices to aid in screening for keratoconus. J. Refract. Surg 11, 371–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz YS, 1998. Keratoconus. Surv. Ophthalmol 42, 297–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts C, 2005. Biomechanical customization: the next generation of laser refractive surgery. J. Cataract Refract. Surg 31, 2–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruberti JW, Sinha Roy A, Roberts CJ, 2011. Corneal biomechanics and biomaterials. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng 13, 269–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarcelli G, Besner S, Pineda R, Yun SH, science v., 2014. Biomechanical characterization of keratoconus corneas ex vivo with Brillouin microscopy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 55, 4490–4495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmack I, Dawson DG, McCarey BE, Waring GO, Grossniklaus HE, Edelhauser HF, 2005. Cohesive tensile strength of human LASIK wounds with histologic, ultrastructural, and clinical correlations. J. Refract. Surg 21, 433–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt J, 1998. OCT elastography: imaging microscopic deformation and strain of tissue. Opt. Express 3, 199–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S, Laiquzzaman M, 2009. Comparison of corneal biomechanics in pre and post-refractive surgery and keratoconic eyes by Ocular Response Analyser. Cont. Lens Anterior Eye 32, 129–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shetty R, Francis M, Shroff R, Pahuja N, Khamar P, Girrish M, Rmma N, Sinha RA, 2017. Corneal biomechanical changes and tissue remodeling after SMILE and LASIK. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 58, 5703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M, Li J, Han Z, Wu C, Aglyamov SR, Twa MD, Larin KV, 2016. Investigating elastic anisotropy of the porcine cornea as a function of intraocular pressure with optical coherence elastography. J. Refract. Surg 32, 562–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M, Li J, Vantipalli S, Han Z, Larin KV, Twa MD, 2017. Optical coherence elastography for evaluating customized riboflavin/UV-A corneal collagen crosslinking. J. Biomed. Opt 22, 091504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S, Huang Z, Nguyen TM, Wong EY, Arnal B, O’Donnell M, Wang RK, 2013a. Shear modulus imaging by direct visualization of propagating shear waves with phase-sensitive optical coherence tomography. J. Biomed. Opt 18, 121509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S, Huang Z, Wang RK, 2013b. Tracking mechanical wave propagation within tissue using phase-sensitive optical coherence tomography: motion artifact and its compensation. J. Biomed. Opt 18, 121505–121505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoerl E, Huhle M, Seiler T, 1998. Induction of cross-links in corneal tissue. Exp. Eye Res 66, 97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vantipalli S, Li J, Singh M, Aglyamov SR, Larin KV, Twa MD, 2018. Effects of Thickness on Corneal Biomechanical Properties Using Optical Coherence Elastography. Optom. Vis. Sci 95, 299–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Larin KV, 2014. Shear wave imaging optical coherence tomography (SWI-OCT) for ocular tissue biomechanics. Opt. Lett 39, 41–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Han Z, Wang S, Li J, Singh M, Liu C, Aglyamov S, Emelianov S, Manns F, Larin KV, 2015. Assessing age-related changes in the biomechanical properties of rabbit lens using a coaligned ultrasound and optical coherence elastography system. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 56, 1292–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]