Abstract

Background

The objective of this study was to explore Canadian emergency physicians’ experiences, concerns, and perspectives during the first wave of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic.

Methods

This cross-sectional survey of physician members of Pediatric Emergency Research Canada and the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians explored: personal safety/responsibility to care; patient interactions; ethical issues in pandemic care; institutional dynamics and communication practices. Data analysis was descriptive: categorical data were summarised with frequency distributions, continuous data [100 mm visual analog scales (VAS)] were analysed using measures of central tendency. Short open-ended items were coded to identify frequencies of responses.

Results

From June 29 to July 29, 2020, 187 respondents (13% response rate) completed the survey: 39% were from Ontario and 20% from Quebec, trained in general (50%) or pediatric (37%) emergency medicine. Respondents reported a high moral obligation to care for patients (97/100, IQR: 85–100, on 100 mm VAS). Fear of contracting COVID-19 changed how 82% of respondents reported interacting with patients, while 97% reported PPE negatively impacted patient care. Despite reporting a high proportion of negative emotions (84%), respondents (59%) were not/slightly concerned about their mental health. Top concerns included a potential second wave, Canada’s financial situation, worldwide solidarity, and youth mental health. Facilitators to provide emergency care included: teamwork, leadership, clear communications strategies.

Conclusion

Canadian emergency physicians felt a strong sense of responsibility to care, while dealing with several ethical dilemmas. Clear communication strategies, measures to ensure safety, and appropriate emergency department setups facilitate pandemic care. Emergency physicians were not concerned about their own mental health, requiring further exploration.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s43678-021-00129-4.

Keywords: COVID-19, Emergency medicine, Pediatric emergency medicine, Physician wellness, Ethics

Résumé

Contexte

L'objectif de cette étude était d'explorer les expériences, les préoccupations et les perspectives des médecins urgentistes canadiens pendant la première vague de la pandémie de coronavirus (COVID-19).

Méthodes

Cette enquête transversale auprès des médecins membres de Pediatric Emergency Research Canada et de l'Association canadienne des médecins d'urgence a permis d'explorer les aspects suivants : sécurité personnelle/responsabilité de soigner ; interactions avec les patients ; enjeux éthiques liés au soin en temps de pandémie ; dynamique institutionnelle et pratiques de communication. L'analyse des données était descriptive : les données catégorielles ont été résumées par des distributions de fréquence, les données continues [échelles visuelles analogiques (EVA) de 100 mm] ont été analysées à l'aide des indicateurs de tendance centrale. Les réponses ouvertes courtes ont été codées pour déterminer la fréquence des réponses.

Résultats

Du 29 juin au 29 juillet 2020, 187 répondants (taux de réponse de 13 %) ont répondu à l'enquête : 39 % provenaient de l'Ontario et 20 % du Québec, fet étaient formés en médecine d'urgence générale (50 %) ou pédiatrique (37 %). Les répondants ont rapporté une obligation morale élevée de s'occuper des patients (97/100, IQR : 85-100, sur une EVA de 100 mm). Quatre-vingt deux pourcent des répondants ont déclaré que la peur de contracter le COVID-19 avait modifié leurs intéractions avec les patients, tandis que, 97 % ont déclaré que l'EPI avait un impact négatif sur les soins aux patients. Bien qu’ils aient rapporté une forte proportion d’émotions négatives (84 %), les répondants (59 %) n’étaient pas/légèrement préoccupés par leur santé mentale. Parmi les principales préoccupations figuraient la possibilité d’une deuxième vague, la situation financière du Canada, la solidarité mondiale et la santé mentale des jeunes. Les facilitateurs chargés de fournir des soins d’urgence comprenaient : le travail d’équipe, le leadership et des stratégies de communication claires.

Conclusion

Les médecins urgentistes canadiens ont ressenti un fort sentiment de responsabilité envers les soins, tout en faisant face à plusieurs dilemmes éthiques. Des stratégies de communication claires, des mesures visant à assurer la sécurité des professionnels d'urgence et une organisation appropriée des services d'urgence facilitent les soins en cas de pandémie. Les médecins urgentistes n'étaient pas préoccupés par leur propre santé mentale, ce qui mériterait une étude une étude plus approfondie.

Clinician’s capsule

| What is known about the topic? | |

| Little is known regarding emergency physicians’ clinical experiences and moral concerns during a pandemic. | |

| What did this study ask? | |

| This study explored Canadian emergency physicians’ experiences, concerns, and perspectives during the first wave of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. | |

| What did this study find? | |

| Emergency physicians felt a strong sense of responsibility to care for patients. They may underestimate the emotional impacts of their work. | |

| Why does this study matter to clinicians? | |

| This knowledge will inform educational tools to prepare physicians during a pandemic and assist in designing future investigations into physician wellbeing. |

Introduction

In Canada, the “first wave” of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic lasted from March to July 2020 and was a healthcare crisis unrivaled in contemporary memory. The experiences of healthcare professionals in the time of a pandemic have been sparsely described. During a pandemic, healthcare professionals deal with issues regarding: (1) the balance of safety (their own and families’) and a responsibility to care [1–5]; (2) altered interactions with patients [4, 6]; (3) interactions between ED physicians and their colleagues, institutions and government [3, 7].

Until recently, emergency physicians’ perspectives of pandemic care were based on hypothetical vignette studies or theoretical reflections [2–4, 6, 8–12]. Studies conducted to date during the COVID-19 pandemic have found conflicting evidence regarding its impact on emergency physicians’ anxiety and burnout levels [13–16]. De Wit et al. found that Canadian emergency physician burnout did not change throughout the first 10 weeks of this pandemic, while Rodriguez et al. found an increase in burnout among American emergency physicians [13–15]. A broader understanding of emergency physicians’ experiences, concerns and perspectives is fundamental to prepare them for the inevitable future pandemic waves and to design emergency preparedness policies. The objective of this study was to explore emergency physicians’ experiences, concerns and perspectives during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada.

Materials and methods

Study population and setting

This was a cross-sectional, electronic survey of a convenience sample of Canadian pediatric and general emergency physicians during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Potential participants were contacted through Pediatric Emergency Research Canada group (PERC) and Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP) databases. PERC is a network of health care providers, from pediatric emergency departments (EDs) across Canada; their database includes physicians who have consented to have their email addresses distributed for research purposes [21]. CAEP is a national professional organisation that distributes surveys to consenting members through their membership database. These databases are updated yearly. Potential participants consisted of all physicians or trainee members practising in a Canadian pediatric or general ED, who were registered in the PERC and/or CAEP databases. Each database is managed differently: PERC’s is managed by the research team, while CAEP members receive the survey directly from its administration, making cross-referencing of participants’ e-mail addresses between both groups impossible.

Tool development

The survey tool was created based on a review of the literature, identifying four themes regarding the practice of emergency medicine (EM) during a pandemic: (1) staff balancing of personal/familial safety and responsibility to care; (2) changes in staff–patient–family interactions; (3) ethical challenges; (4) pandemic institutional dynamics and communication strategies. Five members of the research team (NG, SA, EDT, AJC, HA) developed a survey tool following published guidelines for self-administered clinician surveys [17]. Choice of scales were based on our teams’ experience with previously published clinician surveys of the same sample and previously identified clinician preference [18, 19]. After item generation and item reduction, the survey was pilot tested and reviewed for sensibility by 2 clinical ethicists and mixed-methods researchers to ensure readability, and face and content validity. The survey in English or French was composed of 40 questions, took 20 min to complete and could be reviewed by participants before completion (Supplementary material).

Protocol

Potential participants were contacted through the PERC and CAEP databases during a 4-week period in June and July 2020. Following a Dillman’s tailored design method for mixed-mode surveys, PERC participants received an invitation to participate on days 0, 7, and 14, and CAEP participants received invitations on days 0 and 14 [20]. Survey distribution was planned in June/July to capture experiences from the first wave of the pandemic. Surveys were administered using REDCap (hosted at CHU Sainte-Justine, Montreal), a secure web-based application for building and managing online surveys [21]. An information letter was provided with the invitation to participate. Consent was implied for respondents completing the survey. An arms-length research coordinator was responsible for distributing the survey; the study team was never aware of the identity of the respondents/non-respondents. The CHU Sainte-Justine Research Ethics Board provided ethics approval. The CHERRIES checklist guided the reporting of this study [22].

Data analysis

Categorical data were summarised with frequency distributions; continuous data were analysed using measures of central tendency [medians, interquartile ranges (IQR)]. Short open-ended items were coded by one author (NG) to identify frequencies of responses reported. Continuous variables (100 mm VAS) that displayed very dispersed responses were transformed into categorical variables.

Results

Demographic characteristics

From June 29th to July 29th 2020, the survey was sent to 1229 CAEP and 232 PERC physician and resident members. The survey was completed by 187 respondents (13% response rate); 100 and 87 respondents completed the survey through the CAEP and PERC links, respectively. Given that Canadian physicians can be members of both CAEP and PERC, the overall response rate is actually likely underestimated. Respondents included 63 PERC-only, 92 CAEP-only and 32 PERC and CAEP members. Potential respondents who opened the link but did not complete any of the survey items were considered non-respondents. Demographic information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographic information

| Demographic information (n = 137) | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Province | |

|

Ontario Quebec BC Alberta PEI Manitoba Other |

54 (39) 27 (20) 19 (14) 17 (12) 8 (6) 5 (4) 7 (5) |

| Highest level of training | |

|

Pediatric emergency medicine CCFP EM RC EM GP Fellow in training Other |

50 (36) 38 (28) 30 (22) 10 (7) 3 (2) 4 (3) |

| Female sex | 70 (51) |

|

Age 30–39 40–49 50–59 60–69 |

29 (21) 50 (36) 35 (26) 16 (12) |

| Years in practice | |

|

Training 0–4 5–9 10–19 20–29 > 30 |

3 (2) 13 (10) 23 (17) 46 (34) 34 (25) 18 (13) |

| Proportion of children in ED practice | |

|

0–25% 26–50% 51–75% 76–100% |

58 (42) 13 (10) 0 65 (47) |

None of the respondents had contracted COVID at the time of survey completion, but 27% had self-isolated. Twenty-six percent considered having at least one risk factor for a severe infection; of these, 30% modified their clinical practice. Thirty-five percent of respondents’ partners were essential service workers; of these, 86% worked in healthcare. Most respondents lived with children (77%) or elderly people (52%). Forty-five percent had previously worked in a pandemic in Canada, mostly during Influenza A H1N1 (41%), SARS (35%), Ebola (17%) or MERS-CoV (15%).

Responsibility to care, medical practice and personal safety

Respondents believed they had a very strong moral obligation to care for patients during this pandemic (97/100 mm on a 100 mm VAS; IQR: 85–100). Almost all believed their professionals codes required that they care for patients during the pandemic (95%). Forty percent reported that their clinical EM load was unchanged, 38% reported a decrease and 21% an increase in ED shifts. Moreover, 67% of physicians reported an increase in non-clinical activities (administrative tasks and meetings, learning about COVID-19 and pandemic patient care, academic/research activities). Fifty-six percent of respondents reported a decrease in income, 36% reported no change, and 8% an increase. Only 10% of physicians reported working outside of their usual scope of practice, mostly relating to virtual medicine and new intubation techniques. Nonetheless, 22% were concerned/very concerned about the medicolegal consequences of working outside their usual scope of practice, while 19% believed that the Canadian Medical Protective Association (CMPA) would provide little to no protection when working outside their usual scope of practice.

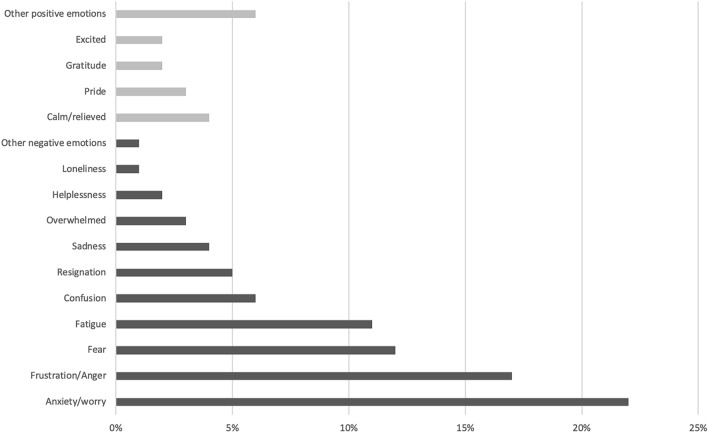

Ninety-six percent of respondents believed their professional code required that they protect themselves from infection. Forty-nine percent had experienced some degree of concern regarding lack of proper personal protective equipment (PPE) in their ED. Most respondents (68%) had never provided care without the appropriate PPE, although 31% had “sometimes” done this. Respondents’ concerns during the first wave of the pandemic are reported in Table 2, and the three emotions they felt most often since the beginning of the pandemic in Fig. 1. Only 5% of respondents had sought mental health support, while most suffered from “a little” (59%) or “a lot” (35%) of information fatigue.

Table 2.

Canadian ED physicians’ pandemic-related concerns

| Concerns (n = 137) | Very concerned % |

Concerned % |

Slightly concerned % |

Not concerned % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The potential for a second wave of pandemic | 49 | 33 | 16 | 2 |

| The pandemic’s impact on Canada’s financial situation | 46 | 37 | 15 | 3 |

| The pandemic’s impact on worldwide solidarity and cooperation | 39 | 37 | 20 | 4 |

| The impact of isolation measures on children and youth’s health | 36 | 40 | 18 | 7 |

| Acquiring the COVID-19 infection at work and transmitting it to your family | 26 | 39 | 27 | 8 |

| Your family’s physical health | 23 | 32 | 27 | 18 |

| The quality of your patients’ care | 13 | 45 | 30 | 12 |

| Your physical health | 15 | 28 | 39 | 17 |

| Your family’s mental health | 14 | 30 | 33 | 23 |

| Transmitting the COVID-19 infection to your work colleagues | 12 | 27 | 34 | 27 |

| Your mental health | 10 | 30 | 30 | 29 |

| Transmitting the COVID-19 infection to patients | 11 | 24 | 39 | 25 |

| The pandemic’s impact on your personal financial situation | 8 | 20 | 25 | 47 |

Fig. 1.

Negative emotions (dark grey) and positive emotions (light grey) felt most often by Canadian ED physicians during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (n = 389)

Interactions with patients

Most respondents (82%) reported that fear of contracting COVID-19 had changed how they interacted with patients. Main themes that emerged included: spending less time with patients, decreased physical contact with patients, taking medical histories over the phone, less access to common ED tools, difficulties in having sensitive conversations with patients. Most (97%) respondents reported that PPE changed patient care. The most common themes included: difficulties creating a bond with patients, limited non-verbal communication and facial expressions, barriers to verbal communication (muffled voices, no lip reading), PPE causing fear in pediatric patients, lost time donning and doffing PPE instead of time spent with patients, limited physical exams, delays and complications during resuscitations.

Ethical challenges during the pandemic

Ethical issues encountered by respondents are reported in Table 3. Ninety-one percent of physicians strongly believed COVID-19 vaccinations should be prioritised for healthcare workers, and 65% strongly believed vaccinations should be prioritised for healthcare workers’ families. Sixty-three percent and 45% strongly believed access to COVID-19 treatments should be prioritised for healthcare workers and for their families, respectively.

Table 3.

Ethical issues encountered by Canadian ED physicians during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic

| Ethical issue (n = 139) | To date, I have already encountered this issue % |

In this pandemic's future, I believe I will encounter this issue or that it will be an ongoing issue % |

I have not encountered and I do not believe I will encounter this issue during this pandemic % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Changes in hospital visiting policies causing additional distress to families | 93 | 14 | 0 |

| Patients postponing their ED visit due to fear of contracting COVID-19 | 93 | 14 | 0 |

| Patients visiting the ED because they are unable to access their primary care practitioner due to changes in clinical practices | 89 | 14 | 3 |

| Patients experiencing complications due to decreases in available healthcare services | 73 | 28 | 3 |

| Balancing personal risk of contracting COVID-19 with responsibility to care for patients | 71 | 26 | 7 |

| Patients and families lying about risk factors for having COVID-19 | 63 | 31 | 10 |

| ED team conflicts regarding different perceptions of risk of contracting COVID-19 | 66 | 19 | 18 |

| Decrease in quality of patient care to protect healthcare teams | 62 | 27 | 16 |

| Decrease in patient safety to protect healthcare teams | 55 | 25 | 23 |

| Allocation of scarce intensive care beds and/or respirators | 9 | 43 | 48 |

Institutional dynamics and communication strategies

Respondents identified two facilitators and two barriers to ED care during the pandemic (Table 4). Respondents rated the clarity of the information they received from various sources: 78%, 76%, 71% and 65% of respondents found information provided by their hospital/health authority, by their public health authority, by their federal government, and by their provincial government, respectively, to be “clear/perfectly clear”.

Table 4.

Facilitators and barriers to ED care during the pandemic

| Facilitators (n = 280) | % | Barriers (n = 288) | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| ED teamwork | 15 | Confusing and changing guidelines | 23 |

| ED leadership | 13 | Availability of appropriate PPE | 16 |

| Hospital leadership to help in the ED | 10 | Inadequate ED setups and environments | 13 |

| Clear information and communication strategies | 10 | ED inefficiency | 8 |

| Decreased ED census | 10 | New treatment protocols | 8 |

| Education | 9 | Patients’ fears of consulting the ED | 7 |

| Sufficient availability of quality PPE | 7 | PPE | 6 |

| Clear provincial and public health guidelines | 6 | Modified physician–patient relationship | 3 |

| Adapting ED care delivery | 5 | Restrictive family presence guidelines | 3 |

| Local initiatives | 4 | Access to consultants | 3 |

| Safety officer or COVID lead | 3 | Testing capacity | 3 |

| Other | 10 | Other | 9 |

Discussion

Interpretation of findings

This was the first study to describe Canadian emergency physicians’ experiences and concerns during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. In our study, emergency physicians felt they had a very strong moral obligation to care for patients. They were not very worried about their own mental health and did not seek mental health support during the first wave, although they experienced an alarming proportion of negative emotions. Fear of contracting COVID-19 and PPE created many barriers to patient care.

Comparison to previous studies

Studies of emergency physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic have shown varying degrees of anxiety and burnout [13–15]. In our study, we found that emergency physicians were not very worried about their own mental health and that they did not seek mental health support during the first wave, although they experienced an alarming proportion of negative emotions. It is possible that participants were not very worried at the time of this survey, as the tool was distributed while the first wave ended. De Wit et al. found similar findings in their cohort of 468 Canadian emergency physicians who did not demonstrate changes in levels of burnout throughout the first wave [14]. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that emergency physicians may underestimate the emotional impacts of their work during such stressful times or that their coping mechanisms and resources lie outside the usual mental health support provided to healthcare workers. Dean suggests that healthcare professionals may need to compartmentalise feelings in the acute phase of a serious stressor in order to perform important tasks [23]. Nonetheless, the ongoing pandemic, as a chronic stressor, is likely to generate more distress if healthcare workers’ feelings and fatigue are not addressed.

Participants in our study found that fear of contracting COVID-19 and PPE created many barriers to patient care, echoing previous findings [6, 10, 11]. During the first wave of the pandemic, healthcare workers received conflicting information from many different sources at a very rapid rate. In our study, participants believed the information they received was clear. ED workers require transparency and clear communication with administration to develop the necessary confidence in their institutions during a pandemic [11, 24, 25]. Furthermore, professional guidelines and directives for patient care need to be developed in a transparent manner to ensure trust and adherence to emerging clinical information, while government and public health initiatives should lead to greater feelings of solidarity and trust from providers [7, 26, 27]. Reciprocity is often reported as an important value to promote during a pandemic [7, 28–30]. Professionals need to know and feel that their institutions will provide the necessary protection from the infection and that they will care for them and their families if they are infected [29, 31]. In our study, physicians believed accessibility to vaccines and COVID-19 treatments should be prioritised for themselves and their families.

The balance between the responsibility to care and personal safety is a core issue for emergency physicians during a pandemic [5, 32, 33]. Previous scenario studies have tried to assess the willingness of healthcare professionals to report to work during a pandemic, with approximately half of respondents reporting willingness to care for patients [8–11]. Professional codes have evolved since their first iterations, from an almost heroic obligation to treat patients during a pandemic, to a weaker duty to treat [29, 30]. It is up to physicians to answer a call to action during a pandemic [34]. Our study was the first to report on emergency physicians’ sense of moral obligation to care for patients and we found a remarkably strong feeling of responsibility. Studies have provided conflicting evidence that professionals with deontological obligations (nurses and physicians) would be more likely to report to work than employees without such duties [24, 35]. Most participants in our study believed their professional codes required that they provide patient care during the pandemic while also protecting themselves. Canadian professional codes do not require that physicians provide direct patient care if they are high risk, unprotected or insufficiently protected [36].

Some of the major ethical dilemmas that had been of theoretical concern during the first days of the COVID-19 pandemic, such as limited intensive care resource allocation, were not experienced by emergency physicians in our study, by the end of July 2020 [37]. Most participants were faced with several moral challenges, such as the consequences of decreased accessibility to care and changes in family visiting policies, while being concerned with major national and international matters.

Clinical implications

Our study supports recent reports identifying important factors to mitigate ED physician stress and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic including sufficient and appropriate PPE, clear communication regarding COVID-19 guideline changes, and rapid provider testing [14–16]. In our study, participants reported ED teamwork, responsive and engaged ED leadership, clear information and communication strategies, hospital leadership, and availability of adequate PPE as key facilitators.

Research implications

This study provides insight into some of the clinical experiences and moral issues Canadian EM physicians were confronted with during the first wave of the pandemic, suggesting that emergency physicians may underestimate the emotional impacts of their work, and that this moral burden may not always be captured by psychometric scales alone. This information will be essential to help guide future studies on EM physicians’ mental health, wellbeing and experiences during this pandemic. Further, mechanisms to address and normalise healthcare professionals’ emotional responses to the pandemic may include sharing of experiences by leaders in the field, creating peer support systems and encouraging the use of employee assistance programmes. These hypotheses would require further investigations, as fatigue, moral injury and burnout are likely to increase with the ongoing pandemic.

Strengths and limitations

This study’s generalisability was limited by its modest response rate. As such, this study likely represents only the views of a convenience sample of ED physicians in Canada, with almost half of them specialised in pediatric EM. Given that the pandemic was experienced very differently across the country and from one ED to another, this convenience sample may not represent the views of all Canadian EM physicians. Nonetheless, this was the first study to explore the moral implications of working during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada and is important to help guide future investigations in this field. Furthermore, as respondents were all members of a Canadian emergency professional organisation, the views presented in this study likely do not represent those of other non-member physicians, or those from other countries. Finally, given that no validated tool was available to conduct this survey, this study was limited by the use of a non-validated survey.

Conclusion

During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, Canadian emergency physicians felt a very strong sense of responsibility to care for patients, while dealing with several ethical issues in their practice. Strategies identified by emergency physicians to facilitate their work include concerted and streamlined communications from trusted sources, sufficient high-quality PPE, appropriate ED setups, and reciprocity measures to ensure their safety. Their lack of concern about their own mental health requires further investigation to develop sustainable support strategies.

Supplementary Information

Checklist---CHERRIES - PERC COVID survey_ESM.docx

Declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Ruderman C, Tracy CS, Bensimon CM, et al. On pandemics and the duty to care: whose duty? who cares? BMC Med Ethics. 2006;7:E5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ehrenstein BP, Hanses F, Salzberger B. Influenza pandemic and professional duty: family or patients first? A survey of hospital employees. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:311. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seale H, Leask J, Po K, MacIntyre CR. “Will they just pack up and leave?”—attitudes and intended behaviour of hospital health care workers during an influenza pandemic. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:30. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ives J, Greenfield S, Parry JM, et al. Healthcare workers’ attitudes to working during pandemic influenza: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malm H, May T, Francis LP, Omer SB, Salmon DA, Hood R. Ethics, pandemics, and the duty to treat. Am J Bioethics AJOB. 2008;8:4–19. doi: 10.1080/15265160802317974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Straus SE, Wilson K, Rambaldini G, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome and its impact on professionalism: qualitative study of physicians’ behaviour during an emerging healthcare crisis. BMJ. 2004;329:83. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38127.444838.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singer PA, Benatar SR, Bernstein M, et al. Ethics and SARS: lessons from Toronto. BMJ. 2003;327:1342–1344. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7427.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qureshi K, Gershon RR, Sherman MF, et al. Health care workers’ ability and willingness to report to duty during catastrophic disasters. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2005;82:378–388. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lanzilotti SS, Galanis D, Leoni N, Craig B. Hawaii medical professionals assessment. Hawaii Med J. 2002;61:162–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi JS, Kim JS. Factors influencing emergency nurses’ ethical problems during the outbreak of MERS-CoV. Nurs Ethics. 2018;25:335–345. doi: 10.1177/0969733016648205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lam KK, Hung SY. Perceptions of emergency nurses during the human swine influenza outbreak: a qualitative study. Int Emerg Nurs. 2013;21:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reilley B, Van Herp M, Sermand D, Dentico N. SARS and Carlo Urbani. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1951–1952. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp030080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chor W, Ng W, Cheng L, et al. Burnout amongst emergency healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multi-center study. Am J Emerg Med. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.de Wit K, Mercuri M, Wallner C, et al. Canadian emergency physician psychological distress and burnout during the first 10 weeks of COVID-19: a mixed-methods study. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Rodriguez RM, Medak AJ, Baumann BM, et al. Academic emergency medicine physicians’ anxiety levels, stressors, and potential stress mitigation measures during the acceleration phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad Emerg Med. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Zalesky C, Dreyfus N, Davis J, Kreitzer N. Emergency medicine physician work environments during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Emerg Med. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Burns KE, Duffett M, Kho ME, et al. A guide for the design and conduct of self-administered surveys of clinicians. CMAJ. 2008;179:245–252. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ali S, Weingarten LE, Kircher J, et al. A survey of caregiver perspectives on children’s pain management in the emergency department. CJEM. 2016;18:98–105. doi: 10.1017/cem.2015.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fowler M, Ali S, Gouin S, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of Canadian pediatric emergency physicians regarding short-term opioid use: a descriptive, cross-sectional survey. CMAJ Open. 2020;8:E148–E155. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20190101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dillman D. Mail and internet surveys: the tailored design method—2007 update with new internet, visual, and mixed-mode guide. Hoboken: Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet E-surveys (CHERRIES) J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e34. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dean W. Suicides of two health care workers hint at the Covid-19 mental health crisis to come. StatNews. 2020.

- 24.Devnani M. Factors associated with the willingness of health care personnel to work during an influenza public health emergency: an integrative review. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2012;27:551–566. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X12001331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gostin LO. Influenza pandemic preparedness: legal and ethical dimensions. Hastings Cent Rep. 2004;34:10–11. doi: 10.2307/3527583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kotalik J. Preparing for an influenza pandemic: ethical issues. Bioethics. 2005;19:422–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2005.00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melnychuk RM, Kenny NP. Pandemic triage: the ethical challenge. CMAJ. 2006;175:1393–1394. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.061322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gostin LO. Medical countermeasures for pandemic influenza: ethics and the law. JAMA. 2006;295:554–556. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.5.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huber SJ, Wynia MK. When pestilence...prevails physician responsibilities in epidemics. Am J Bioethics. 2004;4:W–11. doi: 10.1162/152651604773067497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Upshur R, Faith K, Gibson J, et al. Ethics in an epidemic: ethical considerations in preparedness planning for pandemic influenza. Health Law Rev. 2007;16:33. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaucher N, Racine E. Théories de la Justice. In: Payot A, Janvier A, editors. Éthique clinique: un guide pour aborder la pratique. Montreal: Éditions du CHU Sainte-Justine; 2015:75.

- 32.Iserson KV, Heine CE, Larkin GL, Moskop JC, Baruch J, Aswegan AL. Fight or flight: the ethics of emergency physician disaster response. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iserson KV, Must I. Respond if my health is at risk? J Emerg Med. 2018;55:288–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bensimon CM, Smith MJ, Pisartchik D, Sahni S, Upshur RE. The duty to care in an influenza pandemic: a qualitative study of Canadian public perspectives. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:2425–2430. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Imai H, Matsuishi K, Ito A, et al. Factors associated with motivation and hesitation to work among health professionals during a public crisis: a cross sectional study of hospital workers in Japan during the pandemic (H1N1) 2009. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:672. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bakewell F, Pauls MA, Migneault D. Ethical considerations of the duty to care and physician safety in the COVID-19 pandemic. CJEM. 2020;22:407–410. doi: 10.1017/cem.2020.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.SIAARTI. Raccomandazioni di etica clinica per l’ammissione a trattamenti intensivi e per la loro sospensione, in condizioni eccezionali di squilibrio tra necessità e risorse disponibili—versione 012020. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Checklist---CHERRIES - PERC COVID survey_ESM.docx