Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To estimate 30-day statin discontinuation among newly admitted nursing home residents overall and within categories of life-limiting illness.

DESIGN:

Retrospective cohort using Minimum Data Set 3.0 nursing home admission assessments from 2015 to 2016 merged to Medicare administrative data files.

SETTING:

US Medicare- and Medicaid- certified nursing home facilities (n=13,092).

PARTICIPANTS:

Medicare Fee-for-Service beneficiaries, aged ≥65 years, newly admitted to nursing homes for non-skilled nursing facility stays on statin pharmacotherapy at the time of admission (n=73,247).

MEASUREMENTS:

Residents were categorized using evidence-based criteria to identify progressive, terminal conditions or limited prognoses (<6 months). Discontinuation was defined as the absence of a new Medicare Part D claim for statin pharmacotherapy in the 30 days following nursing home admission.

RESULTS:

Overall 19.9% discontinued statins within 30 days of nursing home admission with rates that varied by life-limiting illness classification (clinician designated as end-of-life: 45.0%; receipt of palliative care consult: 34.5%; palliative care index diagnosis: 22.4%; serious illness: 18.6%; no life-limiting illness: 20.5%). Relative to those with no life-limiting illness, risk of 30-day statin discontinuation increased with life-limiting illness severity (serious illness: adjusted risk ratio (aRR) 1.06, 95% CI 1.02 – 1.10; palliative care index diagnosis: aRR 1.15, 95% CI 1.10 – 1.21; palliative care consult: aRR 1.58, 95% CI 1.43 – 1.74; clinician designated as end-of-life: aRR 1.59, 95% CI 1.42 – 1.79). Nevertheless, most remained on statins after entering the nursing home regardless of life-limiting illness status.

CONCLUSION:

Statin use continues in a large proportion of Medicare beneficiaries after admission to a nursing home. Deprescribing research which identifies how to engage nursing home residents and healthcare providers in a process to safely and effectively discontinue medications with questionable benefits is warranted.

Keywords: long-term care, nursing home, older adults, deprescribing, statins

INTRODUCTION

Despite questionable benefits in some older adults,1–3 statins are commonly used by Medicare beneficiaries.4–6 In the US, nearly half of adults over 65 years of age were on a statin in 2012 to 2013.7 Among patients with a life-limiting condition, statin use is prevalent with half receiving statins in their last six months of life.8 In US nursing homes,9,10 one in three chronically ill residents are on statins.11 Although many of these residents are likely overprescribed,12 less is known about statin discontinuation in nursing homes.

Older adults report a willingness to discontinue statins13 including those with life-limiting illness.14 While most physicians will deprescribe cardiovascular medications in light of debilitating adverse events,15 there remains wide discretion without guidance on prescribing and deprescribing statins in adults over 75 years of age.16 For those with a limited life expectancy, recommendations against routine statin prescribing exist.17 Despite this, less than half of nursing home residents on statins with progressive, severe cognitive impairment discontinue statins.10 No contemporaneous studies, to the best of our knowledge, have evaluated statin discontinuation among a broader population of all nursing home residents in the US.

The objective of this study was to estimate 30-day statin discontinuation among newly admitted nursing home residents overall and within categories of life-limiting illness. Using a national data resource including all Medicare/Medicaid certified nursing homes in the US from 2015–2016, we estimated the proportion of residents who discontinued statins in the 30 days after nursing home admission for a non-skilled nursing facility stay. We hypothesized that statin discontinuation would be strongly associated with life-limiting illness, but that most residents would remain on statins.

METHODS

Study Design

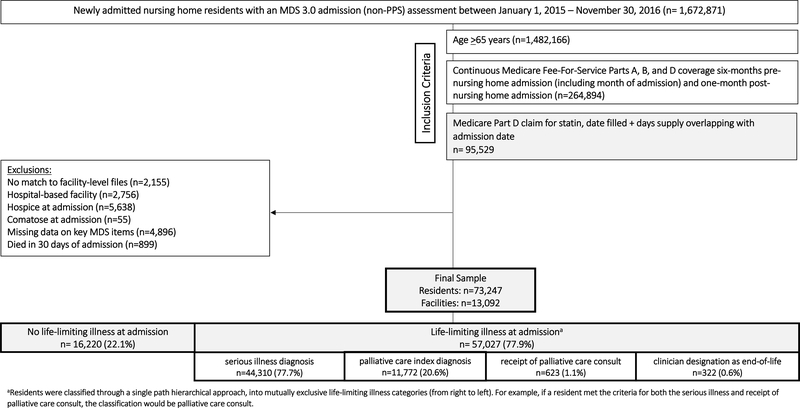

We used a retrospective cohort design. Residents newly admitted to nursing homes for a non-skilled stay between 2015 and 2016 were followed for 30 days from admission date (Figure 1). The study was approved by the University of Massachusetts Medical School Institutional Review Board.

Figure 1.

Study Design

Data Sources

The Minimum Data Set (MDS) 3.0 nursing home assessment database was linked to Medicare administrative data, consisting of: the Master Beneficiary Summary File (MBSF) enrollment files, Medicare Part A (inpatient) claims, Medicare Part D (prescription drug) claims, Nursing Home Compare facility-level data, and the Provider of Service (POS) files.

Life-Limiting Illness Definition

Conceptually, the term ‘life-limiting illness’ was used to identify nursing home residents near the end of life, with varying degrees of terminal illness.18 Operationally, life-limiting illness was defined using four sub-conditions with ICD codes and MDS 3.0 variables (Supplemental Table 1). These sub-conditions included:

Clinician designated as end-of-life determined based on affirmative documentation in MDS 3.0 admission assessments of a prognosis less than six months using MDS variable J1400 (six month or less life expectancy).19

Receipt of palliative care hospital consultation, determined via evidence of inpatient ICD-9 V66.7 or ICD-10 V51.5 claims codes in the six months preceding nursing home admission date. Palliative care is often offered in the hospital to patients near the end of life. This ICD code has been shown to be predictive of severe disease with almost half of patients in one study dying before discharge.20

-

Palliative Care Index (PCI) diagnosis, defined by the Veterans Health Association (2000)21–23 as a set of 13 conditions to identify patients with progressive incurable diseases that could be appropriate for end-of-life services, determined via the presence of at least one condition based on MDS 3.0, ICD-9, and ICD-10 codes. ICD-9 codes from Silveria et al. (2008)23 were cross-walked to MDS 3.0 variables and ICD-10 codes using code translators24 and other indices (Supplemental Table 2).25,26

Serious Illness diagnosis, defined by Kelley et al. (2019)27 as a set of 11 conditions to identify patients with a high mortality risk and declining independence or quality of life, determined via the presence of at least one condition based on MDS 3.0, ICD-9, and ICD-10 codes.27,28 ICD-10 codes from Kelley et al. (2019)27 were crosswalked to MDS 3.0 variables and ICD-9 codes using code translators24 and other indices (Supplemental Table 3).25,26

A six-month lookback period from the date of admission (including month of admission) was used to operationally define life-limiting illness. We classified residents into mutually exclusive life-limiting illness groups, with group assignment based on the first definition met based on the following order : clinician designated as end-of-life, palliative care consult, PCI diagnosis, serious illness diagnosis, no life-limiting illness.

Sample

The sample consisted of Medicare Fee-for-Service beneficiaries newly admitted to a US nursing home with evidence of statin use on the day of admission (Figure 2). Inclusion criteria included: (1) non- skilled nursing facility (SNF) stay nursing home residents with an MDS 3.0 admission (non-PPS) assessment completed between January 1, 2015 and November 30, 2016, (2) Medicare eligible, (3) aged ≥65 years, (4) continuous Medicare Fee-for-Service Parts A, B, and D coverage six months pre-admission (including month of admission) and one month post-admission, (5) baseline statin use with evidence of Medicare Part D claim. If the statin date filled + days supply overlapped with nursing home admission assessment date, the resident was considered a baseline statin user at admission. Exclusion criteria included: (1) no facility match to Nursing Home Compare/POS files, (2) hospital-based facility residence, (3) on hospice at admission, (4) comatose at admission, (5) missing data on key MDS variables, or (6) died within 30 days after admission with no new statin claim. For residents with multiple eligible admission assessments within the study period, one assessment was selected at random.

Figure 2.

Sample Cohort Construction

Newly admitted residents were selected for this study given that most changes to medication regimens in the nursing home appear to occur within the first 30 days after admission.29,30 Moreover, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) requires medication reconciliation and comprehensive drug regimen reviews shortly after admission for all nursing home residents. Therefore, focusing on newly admitted residents enabled us to evaluate the role of nursing homes in statin discontinuation with the assumption that all received comprehensive medication reviews on admission and these reviews were the first of such between the resident and nursing home. SNF and hospice admissions were excluded from the sample due to our inability to measure statin use as medications with these services are bundled into per-diem rates, not reimbursed through Medicare Part D. The sample was further limited to statin users with baseline statin use outside of the hospital as inpatient medication use is also not reimbursed through Part D. Limiting the sample in this way enabled us to focus on the role of the nursing home in deprescribing prevalent statin use, while reducing potential bias associated with the role of the hospital in directing the continuation of inpatient prescriptions after discharge to nursing home.

Statin Discontinuation

Use of statins was operationally defined via Medicare Part D claims for generic or generic combinations of oral statin pharmacotherapy (atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pitavastatin, pravastatin, rosuvastatin, simvastatin). Statin discontinuation was determined by the absence of a statin re-fill in the 30 days post- nursing home admission and evaluated as a binary (yes/no) variable overall and by intensity-level relative to statin classification at admission (baseline). Intensity-level classification was based on the 2013 American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines (Table 1).31 This measure of statin discontinuation was selected based on federal regulations that mandate a comprehensive admission drug regimen review be performed on all new nursing home residents in up to 48 hours following admission, according to the 2014 Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation (IMPACT) Act.32 The 30-day gap period following new nursing home admission was selected based on the assumption of the satisfaction of this requirement including fulfillment of respective prescription orders occurs during this period.

Table 1.

Characteristics of newly admitted nursing home residents by statin discontinuation within 30 days after nursing home admission (resident n=73,247; facility n=13,092)

| Characteristic, column % | Total (n=73,247) | Discontinued Statin (n=14,557) | Continued Statin (n=58,690) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline statin use | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Baseline high-intensity statin usea | 28.5 | 21.5 | 30.2 |

| Resident-level | |||

| Gender | |||

| Women | 67.4 | 66.0 | 67.8 |

| Age | |||

| 65–75 years | 25.9 | 24.3 | 26.4 |

| >75–85 years | 38.0 | 38.7 | 37.9 |

| >85 years | 36.0 | 37.1 | 35.8 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 85.5 | 87.4 | 85.1 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 8.7 | 7.2 | 9.1 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 3.7 | 3.4 | 3.8 |

| Other | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.0 |

| Life-limiting illness | |||

| None | 22.1 | 22.8 | 22.0 |

| Serious Illness | 60.5 | 56.6 | 61.5 |

| Palliative Care Index | 16.1 | 18.1 | 15.6 |

| Palliative Care Consult | 0.9 | 1.5 | 0.7 |

| Clinician designated as end-of-life | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.3 |

| Functional dependenceb | |||

| None to limited assistance required | 24.7 | 23.4 | 25.0 |

| Extensive assistance required | 60.7 | 61.7 | 60.5 |

| Complete assistance required/ dependent | 14.6 | 14.9 | 14.5 |

| Cognitive impairmentc | |||

| None/Intact | 41.9 | 45.7 | 41.0 |

| Mild | 25.3 | 24.2 | 25.5 |

| Moderate | 28.8 | 26.5 | 29.4 |

| Severe | 4.0 | 3.7 | 4.1 |

| Care status | |||

| Rejects care | 8.6 | 8.4 | 8.7 |

| Diagnoses | |||

| Cancer | 6.5 | 7.7 | 6.1 |

| Coronary artery disease | 29.4 | 29.9 | 29.3 |

| Dementia | 25.2 | 22.8 | 25.8 |

| End-stage renal disease | 13.7 | 14.0 | 13.6 |

| Heart failure | 20.0 | 20.5 | 19.8 |

| Liver disease/ cirrhosis | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Neurological (e.g., ALS) | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Peripheral vascular/artery disease | 8.0 | 7.7 | 8.1 |

| Stroke | 12.7 | 11.0 | 13.1 |

| ASCVDd risk factors | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 40.0 | 38.2 | 40.4 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 75.7 | 69.4 | 77.3 |

| Hypertension | 82.7 | 81.8 | 83.0 |

| ASCVD risk | |||

| ASCVD diagnosis | 41.6 | 40.8 | 41.8 |

| ≥1 ASCVD risk factor + no ASCVD diagnosis | 54.6 | 54.5 | 54.7 |

| No ASCVD risk factors + no ASCVD diagnosis | 3.8 | 4.7 | 3.5 |

| Number of non-statin concurrent medications | |||

| 0–5 | 22.2 | 52.0 | 14.8 |

| 6–10 | 36.6 | 24.8 | 39.5 |

| 11+ | 41.2 | 23.2 | 45.7 |

| Source of admission | |||

| Community | 38.0 | 34.7 | 38.8 |

| Acute hospital | 40.8 | 49.1 | 38.8 |

| Nursing home transfer | 18.2 | 13.8 | 19.3 |

| Other | 3.0 | 2.4 | 3.2 |

| Facility- level | |||

| Ownership | |||

| For-profit | 66.4 | 64.6 | 66.8 |

| Government | 26.2 | 27.5 | 25.8 |

| Non-profit | 7.5 | 7.9 | 7.4 |

| Chain status | |||

| Part of chain | 55.6 | 55.1 | 55.7 |

| Skilled nursing care | |||

| ≥50% | 56.3 | 58.5 | 55.8 |

| Staffing | |||

| No Full-time medical director | 95.4 | 95.4 | 95.5 |

| No physician extender | 27.8 | 29.3 | 27.4 |

| Registered nurse <30 minutes per resident/day | 46.7 | 45.4 | 47.0 |

| Direct care <3 hours per resident/day | 6.9 | 6.2 | 7.1 |

| % Black/African American residents | |||

| 0 to <15% | 80.4 | 82.2 | 80.0 |

| 15 to <50% | 16.1 | 15.1 | 16.4 |

| ≥50% | 3.5 | 2.7 | 3.7 |

| Facility average # of medications per resident | |||

| ≥6 medications | 54.7 | 51.5 | 55.5 |

| Residents dependent in activities of daily living (ADLs) | |||

| >50% | 11.5 | 10.9 | 11.6 |

| Overall Nursing Home Compare Star rating | |||

| 1 | 14.6 | 13.6 | 14.8 |

| 2 | 19.3 | 18.0 | 19.6 |

| 3 | 18.9 | 18.2 | 19.1 |

| 4 | 24.6 | 25.9 | 24.3 |

| 5 | 22.6 | 24.3 | 22.2 |

| Regional- level | |||

| urban location (non-rural) | 71.8 | 69.4 | 72.4 |

| US census region | |||

| Northeast | 23.5 | 21.8 | 23.9 |

| Midwest | 35.9 | 36.8 | 35.7 |

| South | 30.7 | 31.2 | 30.6 |

| West | 9.9 | 10.3 | 9.8 |

Baselinehigh-intensity statin use = Based on ACC/AHA 2013 guidelines, high-intensity statin (daily dose LDL-C reduction >50%) included: atorvastatin 40 – 80 mg, rosuvastatin 20 – 40 mg, and simvastatin 80 mg. Low- to moderate-intensity statins (daily dose LDL-C reduction <30% to <50%) included: atorvastatin 10 – 20 mg, fluvastatin 20 – 80 mg, lovastatin 10 – 40, or 80 mg, pitavastatin 1 – 4 mg, pravastatin 10 – 80 mg, rosuvastatin 5 – 10 mg, and simvastatin 5 – 40 mg

functional dependence = MDS-ADL Self-Performance Hierarchy (Morris et al. 1999; scored 0–6): independent to limited assistance required (0–2), extensive assistance required (3–4), and dependent to total dependence (5–6) in performing activities of daily living (ADLs)

cognitive impairment = Cognitive Function Scale (Thomas et al. 2015) - Brief Interview for Mental Status (BIMS; scored 0–15) and the Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS; scored 0–6) if unable to self-report: none (or cognitively intact; BIMS: 13–15), mild (BIMS: 8–12, CPS: 0–2), moderate (BIMS: 0–7, CPS: 3–4), and severe (CPS: 5–6)

ASCVD = Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease including diagnoses of coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, and stroke

Independent Variables

Resident-level variables (drawn from MDS 3.0) and facility-level variables (drawn from POS and Nursing Home Compare files) were used to define sociodemographic, clinical, and facility characteristics that have shown associations with nursing home statin use in previous studies.9–11 Sociodemographic characteristics included: gender, age in years (65–75, >75–85, >85), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic/Latino, other), functional dependence33 (none to limited assistance required, extensive assistance required, complete assistance required/ dependent), cognitive impairment34 (none/intact, mild, moderate, severe), and urban location status (urban, rural). Clinical characteristics included: rejection of care, high-intensity statin use at admission (daily dose LDL-C reduction >50%),31 number of non-statin medications (0–5, 6–10, ≥11), source of admission to nursing home (community, acute hospital, nursing home transfer, other), cardiovascular disease (CVD)-related risk factors (diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension), CVD related-diagnoses (coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, stroke, heart failure), other diagnoses (cancer, dementia, liver disease/cirrhosis, neurological conditions). Facility characteristics included: ownership type (for-profit, government, non-profit), chain status, skilled nursing care >50%, presence of full-time medical director, presence of physician extenders, registered nurse <30 minutes per resident/day, direct care <3 hours per resident/day, average of ≥6 medications per resident, overall Nursing Home Compare quality rating (1–5), and US census region (northeast, midwest, south, west).

Analytic Approach

Descriptive statistics were used to describe sample characteristics by statin discontinuation and life-limiting illness status. Poisson models with robust confidence intervals (CI)35,36 provided crude and adjusted estimates of the relative risk (aRR) and 95% CI for statin discontinuation within 30 days of nursing home admission, adjusting for all sociodemographic, clinical, and facility variables described.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

-

Overall. Of the eligible newly admitted nursing home residents, 36% were on statins at the time of admission. The final cohort included 73,247 newly admitted nursing homes residents with baseline statin use from 13,092 US nursing home facilities; 28.5% were on high-intensity statins at baseline. The sample (Table 1) was mostly women (67.4%), non-Hispanic white (85.5%), and of advanced age (74% aged >75 years). The sample was relatively impaired both functionally (75.3% with moderate to complete functional dependence) and cognitively (32.8% with moderate to severe cognitive impairment). Clinically, <10% rejected care, 25.2% had a diagnosis of dementia, and 96.2% either had a diagnosis of atherosclerosis cardiovascular disease (ASCVD; 41.6%) or ASCVD risk factors (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus) without the disease itself (54.6%). Three quarters were on six or more non-statin medications at the time of their admission assessment (36.6% on 6–10 medications, 41.2% on >11 medications).

By Life-Limiting Illness. Breaking down the sample by life-limiting illness at admission (Figure 2), 22.1% had no life-limiting illness (n=16,220) and 77.9% met the criteria for life-limiting illness (n=57,027). Among those with a life-limiting illness: 77.7% had a serious illness diagnosis, 20.6% had a palliative care index diagnosis, 1.1% had a palliative care consult, and 0.6% had a prognosis <six-months.

In terms of characteristics across life-limiting illness classification (Supplemental Table 4), distributions remained relatively consistent with a few exceptions. Mean age in years was relatively consistent across life-limiting illness groups (mean ± standard deviation age of: no life-limiting illness: 82.3±8.5, serious illness: 81.7±8.1, palliative care index: 79.9±8.3, palliative care consult: 81.8±8.4, clinician designated as end-of-life: 81.5±8.8). In terms of source of admission, distributions appeared to vary by severity of life-limiting illness. Of those in the most severe life-limiting illness groups (palliative care index, palliative care consult, clinician designated as end-of-life), more than half in each life-limiting group were admitted from an acute care hospital setting with one-third or less admitted from the community. Residents in the less severe life-limiting illness groups (none, serious illness), were admitted relatively equally from an acute care setting or the community (approximately 40% from each setting).

Statin Discontinuation

-

Overall. Of the sample (Table 1), 19.9% discontinued statins within 30 days after nursing home admission. Over 20% (21.5%) of those that discontinued statins were on high-intensity doses at baseline.

In terms of other characteristics associated with statin discontinuation (Supplemental Table 5), those admitted with high intensity statin use at baseline (viewed as a marker of CVD severity) were less likely to discontinue statins compared to those with low-moderate intensity statin use at baseline (aRR: 0.77, 95% CI: 0.74–0.79). Non-Hispanic black residents were less likely to discontinue statins compared to non-Hispanic white residents (aRR: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.81 – 0.91). Most ASCVD conditions were not associated with statin discontinuation with the exception of stroke (aRR: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.84 – 0.92). ASCVD risk factors were associated with statin discontinuation including diabetes mellitus (aRR: 1.13, 95% CI: 1.09 – 1.16), hyperlipidemia (aRR: 0.71, 95% CI: 0.69 – 0.74), and hypertension (aRR: 1.10, 95% CI: 1.06 – 1.14). Regarding source of admission, compared to residents admitted from the community: those admitted from an acute care hospital were more likely to discontinue statins (aRR: 1.18, 95% CI: 1.14 – 1.22), while those transferred from a nursing home appeared to have no difference in risk of discontinuation (aRR: 1.03, 95% CI: 0.98 – 1.08).

By Life-limiting Illness. Discontinuation varied by life-limiting illness classification (Figure 3). The proportion of residents discontinuing statin use in 30 days was similar among residents with no life-limiting diagnoses (20.5%), a serious illness diagnosis (18.6%), and a diagnosis included in the palliative care index (22.4%). Discontinuation was highest in those who received a palliative care consult (34.5%) or in those whose clinician designated them as end-of-life (45.0%). Adjusting for a host of resident-level sociodemographic and clinical factors, as well as facility-level factors, did not explain the differences in 30-day statin discontinuation by life-limiting illness classification (Table 2). Among residents who received a palliative care consult, 40.1% of low-intensity statin users and 22.9% of high-intensity users at baseline discontinued in 30 days post admission. Among those whose clinician designated as end-of-life, discontinuation proportions were similar regardless of statin dosing at baseline.

Figure 3.

Percent statin discontinuation within 30 days of nursing home admission by life-limiting illness classification (statin intensity designation based on 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines

Table 2.

Association of life-limiting illness classification and statin discontinuation within 30 days of nursing home admission (resident n=73,247; facility n=13,092)

| Relative Risk (95% Confidence Interval)* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Variable Adjustments | Crude | Sociodemographic | Sociodemographic + Clinical | Sociodemographic + Clinical + Facility |

| Life-Limiting Illness Classification | ||||

| Non- life-limiting illness | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Serious Illness | 0.92 (0.89–0.96) | 0.95 (0.91 – 0.99) | 1.05 (1.02 – 1.10) | 1.06 (1.02 – 1.10) |

| Palliative Care Index | 1.02 (0.97 – 1.07) | 1.03 (0.98 – 1.08) | 1.15 (1.10 – 1.21) | 1.15 (1.10 – 1.21) |

| Palliative Care Consult | 1.64 (1.46 – 1.84) | 1.66 (1.48 – 1.87) | 1.58 (1.43 – 1.74) | 1.58 (1.43 – 1.74) |

| Clinician designated as end-of-life | 2.21 (1.93 – 2.52) | 2.23 (1.96 – 2.54) | 1.59 (1.42 – 1.79) | 1.59 (1.42 – 1.79) |

Crude and adjusted relative risk estimated via modified Poisson models with robust 95% confidence intervals.

Model Variable Adjustments defined:

- sociodemographic variables = gender, age, race, ADL status, cognitive impairment, urban location status

- clinical variables = high intensity statin use, rejection of care, source of admission to nursing home, and diagnoses of: cancer, dementia, liver disease/ cirrhosis, neurological conditions, cardiovascular disease (CVD)-related conditions (coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, stroke, heart failure), CVD risk factors (diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension), and number of non-statin concurrent medications

- facility variables = ownership type, chain status, >50% skilled nursing care, presence of full-time medical director, presence of physician extenders, registered nurse <30 minutes per resident/day, direct care <3 hours per resident/day, average of 6+ medications per resident, overall nursing home star quality rating (1–5)

DISCUSSION

In a nationwide sample of newly admitted nursing home residents with statin use at admission, one in five discontinued statins within 30 days of admission. Discontinuation varied by life-limiting illness classification with likelihood of discontinuation appearing to increase with condition severity. However, the majority of residents remained on statins after admission regardless of life-limiting illness status. In addition to life-limiting illness classification, the most predictive factors of discontinuation included intensity of statin use at baseline as a marker of CVD severity and source of admission.

Our estimates of statin use and discontinuation in older adults resemble rates reported elsewhere.9–11,37 Other studies9,11 conducted in comparable nursing home populations reported statin use to be around 30%, similar to our findings (36%). For discontinuation rates in the older adult US population, one study found that approximately 15% of older adult Medicare beneficiaries discontinued statins after 182 days (~6 months) post-discharge from a hospitalization for myocardial infarction,37 similar to our findings. However, we found statin discontinuation to vary by life-limiting illness classification severity. Those identified as being near the end of life via clinician designation or with receipt of a palliative care consult claim appeared more likely to discontinue statins. This mirrors other studies including one on nursing home residents with advanced, progressive dementia in a few US states.10 This study reported a discontinuation rate of 37.2%, which is consistent with our findings among residents with severe life-limiting illness classifications (clinician designated as end-of-life: 45.0%; receipt of palliative care consult: 34.5% ).

Despite higher rates of discontinuation in nursing homes residents with a limited life expectancy and evidence that life expectancy is considered when deprescribing statins,15,38 we still found that over half of those with a prognosis less than six months remained on statins after their nursing home admission. A growing body of evidence suggests that older adults with a limited life expectancy are unlikely to benefit from statins3,17,39 and could potentially be harmed from continued use.2 Other studies have shown that life-limiting illness does not preclude nursing home residents from being on statins,8,10,11 with some even showing use that continues until the last days of life.10,23 With diminished benefits among those with a limited prognosis,3,40 the mechanisms driving persistent statin use in this population remain unclear.

Potential Mechanisms and Implications

One consideration driving rates of statin utilization is facility-level resources (e.g., physician extender availability, amount of direct care provided etc.). Yet, we found that many of these facility-level factors were not significantly associated with discontinuation. Notably resident-level factors appeared to be more strongly associated with statin discontinuation, especially source of admission. Those admitted from an acute care setting were more likely to discontinue statins, while nursing home transfers were just as likely to discontinue statins as those admitted from the community. Perhaps the onset of new medications, which are often prescribed following a hospitalization, affects the thoroughness of the medication reconciliation process upon nursing home admission. Of note, an admission drug regimen review is required for all admitted to a CMS-certified nursing home facility.32 Even with this requirement, our results highlight the need for a more thorough approach to medication reconciliation with nursing home admissions outside of hospital transfers.

Another potential mechanism driving the rates of statin utilization is national guidelines. Changes to national guidelines on statin prescribing have shown to affect prescribing patterns.4 Currently, the few national guidelines on statin prescribing (and deprescribing) for older adults over 75 years of age are inconsistent.38,41 Part of the issue underlying inconsistent guidelines is likely the insufficient availability of evidence on the efficacy and safety of statins in older adults. Clinical trials on treatment of cardiovascular disease have historically excluded older adults.42 This has led to a deficit of prospective data in this population. Nonetheless, a recent clinical trial on the discontinuation of statins in patients with a life-limiting illness demonstrated cessation of statins is not only safe, but also could have potential quality of life benefits.3 Without updating guidelines and providing clear deprescribing recommendations, this deficiency is a barrier that could provide a theoretical basis to rationalize why residents continue to receive statins near the end of life.43 National guidelines should be updated to include deprescribing recommendations for this specific population.

Without clear guidance, discontinuation of statins is left to clinical judgment. Although decision-making with patients that do not have a terminal prognosis may be less straight-forward, an individualized approach to care for a heterogenous older population has often been recommended.44,45 However, an individualized approach to deprescribing is not without barriers. A recent study (2019)15 reported that the most frequently cited barrier to deprescribing cardiovascular medications among different types of physicians is a fear of interfering with another provider’s treatment plan and perceived patient reluctance. Evidence suggests that perceived patient reluctance may be unfounded. In the case of older patients with life-limiting illness taking statins, it was reported that few in this population expressed concerns when asked to consider discontinuation.14 Overall, these provider barriers appeared mostly centered on communication and thus, best addressed through access to tools to facilitate communication, particularly between patient and provider. While not standardized, deprescribing guidelines and tools are available to help direct the process of statin discontinuation and facilitate patient-provider communication.46–50 This includes a multitude of clinician and patient resources specific to older adult care available from the US Deprescribing Research Network.50

Strengths and Limitations

This is the first study to evaluate statin deprescribing in US nursing homes on a national scale. We used a robust data source with recent data and a large sample. However, this study had several limitations, including: limited follow-up time, potential misclassification of statin use, potential unmeasured confounding, and concerns of generalizability. The limited follow-up time of 30 days post- nursing home admission was selected to focus on the effect of entering a nursing home on statin discontinuation given that timely medication reconciliation and review is required for every nursing home admission. However, studies with longer follow-up may be useful to understand the extent to which statins are re-initiated or continued up until death. Misclassification of statin use is possible as it was measured using Medicare claims. However, given the regulated nature of nursing homes, this potential bias is unlikely to be significant. As an observational study, the findings are limited by the potential for unmeasured confounding including laboratory values, especially low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and intent of discontinuation. If deprescribing or down-titration of statin dosing was evaluated, this may have provided more information on the intent, but is beyond the scope of this study. Finally, the sample did not include SNF admissions, hospice enrollees, and those without Medicare Fee-For-Service health insurance due to the constraints in our available data. Results may not be generalizable to these groups and others excluded (e.g., comatose residents) due to fundamental differences between our nursing home sample and the excluded populations, particularly hospice enrollees as their medical care and prescriptions are managed by outside entities, distinct from nursing home staff.

CONCLUSION

Using a national sample of nursing home residents, we found that only one in five newly admitted statin users discontinued statins within 30 days of admission. While life-limiting illness classification was associated with 30-day statin discontinuation, the majority of residents regardless of health status remained on statins after nursing home admission. These findings underscore the need for research on how best to safely and effectively discontinue statins in nursing homes. National guidelines should be updated with recommendations on statin deprescribing in older populations not likely to benefit from use.

Supplementary Material

IMPACT STATEMENT:

We certify that this work is novel. This research provides recent estimates of statin discontinuation among newly admitted, non-skilled stay nursing home residents, illuminating national deprescribing practices. Our findings highlight the need for improved guidance and better patient-provider communication regarding the deprescribing of statins, particularly for those near the end of life.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

FUNDING SOURCES:

The work was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (TL1 TR001454), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R36 HS026840). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Disclaimer: This project was supported by grant number R36HS026840 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Jennifer Tjia is a consultant for CVS Health and Omnicare Long Term Care Pharmacy. Kate Lapane is a consultant to Barbara Zarowitz to periodically review monographs on short stay prescribing guidelines for Empirian Health. The other authors have declared no conflicts of interest for this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stone NJ, Intwala S, Katz D. Statins in very elderly adults (debate). J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62(5):943–945. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12788_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curfman G. Risks of statin therapy in older adults. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177(7):966. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kutner JS, Blatchford PJ, Taylor DH, Ritchie CS, Bull JH, Fairclough DL, et al. Safety and Benefit of Discontinuing Statin Therapy in the Setting of Advanced, Life-Limiting Illness. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175(5):691. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenson RS, Farkouh ME, Mefford M, Bittner V, Brown TM, Taylor B, et al. Trends in Use of High-Intensity Statin Therapy After Myocardial Infarction, 2011 to 2014. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69(22):2696–2706. doi: 10.1016/J.JACC.2017.03.585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yun H, Safford MM, Brown TM, Farkouh ME, Kent S, Sharma P, et al. Statin Use Following Hospitalization Among Medicare Beneficiaries With a Secondary Discharge Diagnosis of Acute Myocardial Infarction. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tran JN, Caglar T, Stockl KM, Lew HC, Solow BK, Chan PS. Impact of the New ACC/AHA Guidelines on the Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in a Managed Care Setting. Am Heal drug benefits 2014;7(8):430–443. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25558305. Accessed March 7, 2018. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salami JA, Warraich H, Valero-Elizondo J, Spatz ES, Desai NR, Rana JS, et al. National Trends in Statin Use and Expenditures in the US Adult Population From 2002 to 2013. JAMA Cardiol 2017;2(1):56. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.4700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silveira MJ, Kazanis AS, Shevrin MP. Statins in the last six months of life: A recognizable, life-limiting condition does not decrease their use. J Palliat Med 2008;11(5):685–693. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campitelli MA, Maxwell CJ, Giannakeas V, Bell CM, Daneman N, Jeffs L, et al. The Variation of Statin Use Among Nursing Home Residents and Physicians: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65(9):2044–2051. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tjia J, Cutrona SL, Peterson D, Reed G, Andrade SE, Mitchell SL. Statin discontinuation in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62(11):2095–2101. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mack DS, Tjia J, Hume AL, Lapane KL. Prevalent Statin Use in Long‐Stay Nursing Home Residents with Life‐Limiting Illness. J Am Geriatr Soc February 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ouslander JG. Improving Drug Therapy for Patients With Life-Limiting Illnesses: Letʼs Take Care of Some Low Hanging Fruit. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qi K, Reeve E, Hilmer SN, Pearson SA, Matthews S, Gnjidic D. Older peoples’ attitudes regarding polypharmacy, statin use and willingness to have statins deprescribed in Australia. Int J Clin Pharm 2015;37(5):949–957. doi: 10.1007/s11096-015-0147-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tjia J, Kutner JS, Ritchie CS, Blatchford PJ, Bennett Kendrick RE, Prince-Paul M, et al. Perceptions of Statin Discontinuation among Patients with Life-Limiting Illness. J Palliat Med 2017;20(10):1098–1103. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goyal P, Anderson TS, Bernacki GM, Marcum ZA, Orkaby AR, Kim D, et al. Physician Perspectives on Deprescribing Cardiovascular Medications for Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019:1–9. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ploeg MA Van Der, Floriani C, Achterberg WP, Bogaerts JMK, Gussekloo J, Mooijaart SP, et al. Recommendations for ( Discontinuation of ) Statin Treatment in Older Adults : Review of Guidelines. 2019:1–9. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Medical Directors Association. Choosing Wisely: Don’t Routinely Prescribe Lipid-Lowering Medications in Individuals with a Limited Life Expectancy. - American Family Physician; 2019. https://www.aafp.org/afp/recommendations/viewRecommendation.htm?recommendationId=98. Accessed August 16, 2019.

- 18.Hui D, Nooruddin Z, Didwaniya N, Dev R, De La Cruz M, Kim SH, et al. Concepts and definitions for "actively dying," "end of life," "terminally ill," "terminal care," and "transition of care": a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;47(1):77–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.02.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.CMS. CMS’s RAI Version 3.0 Manual CH 3: MDS Items [J] SECTION J: HEALTH CONDITIONS. 2010. https://www.ahcancal.org/facility_operations/Documents/UpdatedFilesOct2010/Chapter 3-Section J V1.04 Sept 2010.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2017.

- 20.Hua M, Li G, Clancy C, Sean Morrison R, Wunsch H. Validation of the V66.7 Code for Palliative Care Consultation in a Single Academic Medical Center. J Palliat Med 2017;20(4):372–377. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Veterans Health Administration. Palliative Care Index. In: Journey of Change III. Washington DC; 2000:15. https://books.google.com/books?id=RJI3rdAaOdUC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false. Accessed November 25, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar G, Hayes K. Hospice and Palliative Care Strategic Plan for an Inpatient Unit: The Dayton Example. In: Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA), Geriatrics and Extended Care in the Office of Patient Service, eds. A Toolkit for Developing Hospice and Palliative Care Programs in the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Centers. Washington DC: VA Training and Program Assessment for Palliative Care (TAPC) Project; 2001:52–57. www.va.gov/oaa/flp. Accessed August 13, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silveira MJ, Segnini Kazanis A, Shevrin MP. Statins in the Last Six Months of Life: A Recognizable, Life-Limiting Condition Does Not Decrease their Use. J Palliat Med 2008;11(5). doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.AAPC. Online ICD Code Translator Tool. https://www.aapc.com/icd-10/codes/. Published 2020. Accessed February 3, 2020.

- 25.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Transition from ICD-9-CM to ICD-10. CMS.gov. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/ICD9ProviderDiagnosticCodes. Accessed February 13, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Medical Association. 2016 ICD-10-CM : The Complete Official Codebook. American Medical Association; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelley AS, Ferreira KB, Bollens-Lund E, Mather H, Hanson LC, Ritchie CS, et al. Identifying Older Adults With Serious Illness: Transitioning From ICD-9 to ICD-10. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019;57(6):1137–1142. https://www-sciencedirect-com.ezproxy.lib.umb.edu/science/article/pii/S0885392419301162. Accessed August 14, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelley AS, Bollens-Lund E. Identifying the Population with Serious Illness: The Denominator Challenge. J Palliat Med 2018;21(S2):S7–S16. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boockvar K, Fishman E, Kyriacou CK, Monias A, Gavi S, Cortes T. Adverse Events Due to Discontinuations in Drug Use and Dose Changes in Patients Transferred between Acute and Long-term Care Facilities. Arch Intern Med 2004;164(5):545–550. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.5.545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Statin Discontinuation, Reinitiation, and Persistence Patterns Among Medicare Beneficiaries After Myocardial Infarction A Cohort Study. 2017. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.003626. Accessed January 22, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, Bairey Merz CN, Blum CB, Eckel RH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63(25):2889–2934. doi: 10.1016/J.JACC.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.By A, Ascp THE, Of B, July D. Guidelines for Admission Medication Regimen Review (aMRR) in the Nursing Facility Setting. 2019;(February 2014):1–8. doi: 10.1177/1060028017712725.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morris JN, Fries BE, Morris SA. Scaling ADLs Within the MDS. Journals Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci 1999;54(11):M546–M553. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.11.M546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas KS, Dosa D, Wysocki A, Mor V. The Minimum Data Set 3.0 Cognitive Function Scale. Med Care 2015;55(9):e68–e72. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zou G. A Modified Poisson Regression Approach to Prospective Studies with Binary Data. Am J Epidemiol Hopkins Bloom Sch Public Heal All rights Reserv 2004;159(7):702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen W, Shi J, Qian L, Azen SP. Comparison of robustness to outliers between robust poisson models and log-binomial models when estimating relative risks for common binary outcomes: A simulation study. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14(1):82. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Booth JN, Colantonio LD, Chen L, Rosenson RS, Monda KL, Safford MM, et al. Statin Discontinuation, Reinitiation, and Persistence Patterns Among Medicare Beneficiaries After Myocardial Infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2017;10(10). doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.003626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van der Ploeg MA, Floriani C, Achterberg WP, Bogaerts JMK, Gussekloo J, Mooijaart SP, et al. Recommendations for (Discontinuation of) Statin Treatment in Older Adults: Review of Guidelines. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019:1–9. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Todd A, Husband A, Andrew Pearson I, Lindsey Holmes L. Inappropriate prescribing of preventative medication in patients with life limiting illness: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2016;7(2):113–121. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-000941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holmes HM, Min LC, Yee M, Varadhan R, Basran J, Dale W, et al. Rationalizing Prescribing for Older Patients with Multimorbidity: Considering Time to Benefit. Drugs Aging 2013;30(9):655–666. doi: 10.1007/s40266-013-0095-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tibrewala A, Jivan A, Oetgen WJ, Stone NJ. A Comparative Analysis of Current Lipid Treatment Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71(7):794–799. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gurwitz JH, Goldberg RJ. Age-Based Exclusions From Cardiovascular Clinical Trials: Implications for Elderly Individuals (and for All of Us). Arch Intern Med 2011;171(6):557–558. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Narayan SW, Prasad •, Nishtala S. Discontinuation of Preventive Medicines in Older People with Limited Life Expectancy: A Systematic Review. Drugs Aging 2017;34. doi: 10.1007/s40266-017-0487-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee SJ, Kim CM. Individualizing Prevention for Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66(2):229–234. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Neill D, Stone NJ, Forman DE. Primary Prevention Statins in Older Adults: Personalized Care for a Heterogeneous Population. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020;68(3):467–473. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krishnaswami A, Steinman MA, Goyal P, Zullo AR, Anderson TS, Birtcher KK, et al. Deprescribing in Older Adults With Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73(20):2584–2595. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thompson W, Lundby C, Graabæk T, Nielsen DS, Ryg J, Søndergaard J, et al. Tools for Deprescribing in Frail Older Persons and Those with Limited Life Expectancy: A Systematic Review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67(1):172–180. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moriarty F, Bennett K, Kenny RA, Fahey T, Cahir C. Comparing Potentially Inappropriate Prescribing Tools and Their Association With Patient Outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020;68(3):526–534. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reeve E. Deprescribing tools: a review of the types of tools available to aid deprescribing in clinical practice. J Pharm Pract Res 2020;50(1):98–107. doi: 10.1002/jppr.1626 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.US Deprescribing Research Network. Resources for Clinicians. https://deprescribingresearch.org/resources-2/resources-for-clinicians/. Accessed July 4, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.