Abstract

Aging in Community (AIC) is the preferred way to age. This systematic review identified promising AIC models in the U.S. and analyzed model characteristics and push-pull factors from older adults’ perspectives. Push factors are those driving older adults to leave, while pull factors attract them to stay in a community. We conducted a two-phase search strategy using eight databases. Phase I identified promising AIC models and Phase II expanded each specific model identified. Fifty-two of 244 screened articles met the criteria and were analyzed. We identified four promising AIC models with the potential to achieve person-environment (P-E) fit, including village, naturally occurring retirement community (NORC), cohousing, and university-based retirement community (UBRC). Each has a unique way of helping older adults with their aging needs. Similar and unique push-pull factors of each AIC model were discussed. Analyses showed that pull factors were mostly program factors while push factors were often individual circumstances. Continued research is needed to address the challenges of recruiting minority older adults and those of lower socio-economic status, meeting older adults’ diverse and dynamic needs, and conducting comparative studies to share lessons learned across the globe.

Keywords: aging in community, village, naturally occurring retirement community, cohousing, university-based retirement community

Introduction

Aging in Community (AIC) is “a grassroots movement of like-minded citizens who come together to create systems of mutual support and caring to enhance their well-being, improve their quality of life, and maximize their ability to remain, as they age, in their homes and communities” (Blanchard, 2013, p. 7). AIC intentionally encourages older adults to engage in mutually supportive relationships to promote quality of life and a sense of community (Thomas & Blanchard, 2009).

To achieve Aging in Community, the community should meet older adults’ diverse needs regarding housing, health and caregiving, personal finance, social engagement, and transportation (National Aging in Place Council, 2021). From the social-physical perspective, older adults desire to have the agency or autonomous control of their physical or social condition, such as health, finance, housing maintenance, and travel (Geboy et al., 2012; Lang, 2004; National Aging in Place Council, 2021; Smith et al., 2014). Older adults often have place attachment and desire social-physical belonging or security with a sense of emotional connections to the environment (Geboy et al., 2012; Lang, 2004). While younger older adults may have equivalent agency and belonging needs, as one ages, older adults may face a decreased capability to perform their agency roles and have increased belonging needs (Geboy et al., 2012; Wahl & Lang, 2003).

An ideal supportive community or environment should also aim to achieve person-environment fits. Person-environment fits argue that “persons within particular subgroups may be at risk of maladaptation—low well-being and life quality, for example—depending on the level of fit between their needs and environment. Even those who have limited resources and capability can age optimally if environmental characteristics support them in a way that compensates for their limitations or lack of resources” (Park et al., 2017, p. 1328). A supportive environment for aging in the community can be any natural or intentionally designed community that supports older adults’ various health and social needs, including access to health services, meal services, housekeeping, transportation, and social activities. The environment should incorporate aging and universal design with barrier-free physical features such as handlebars in bathrooms and wheelchair ramps (Park et al., 2017). The services or activities should be available at an easily accessible distance or accessible via public transportation (Geboy et al., 2012; Lavery, 2015). Last but not least, affordable housing options for older adults with different needs should be available. AIC aims to delay the need for institutional care by providing a holistic approach to support older adults’ agency or autonomy control toward home maintenance, health services, finance management, social participation, and transportation, and promote a sense of belonging in the community (Scharlach, 2009). Promising AIC models should have opportunities to achieve person-environment fit and address challenges when members lose independence.

Promising AIC Models in the U.S

Four promising AIC modules in the U.S. showing the potential to achieve person-environment fit. These included villages, Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities-Supportive Service Program Model (NORC-SSP), cohousing, and university-based retirement communities (UBRCs) (Bookman, 2008; Chum et al., 2020; Scharlach, 2009; Stone, 2013). The village and UBRC models are mostly private-sector strategies and more affordable for older adults in the middle- or higher-class. NORC-SSP is mostly public-sector strategies to address aging needs in highly concentrated community areas with older adults (Stone, 2013). Cohousing focuses primarily on changing the community’s physical infrastructure concerning housing and land used to build age-friendly environments in cohousing communities (Scharlach, 2009).

Villages are grass-roots programs run by trained volunteers and paid staff to coordinate village-wide programs and activities and connect members to free, low-cost, or discounted services (Village to Village Network [VtVN], n.d.). These consumer-driven organizations aim to enable older adults aging in homes and communities to promote social interactions and reduce isolation (VtVN, n.d.). The majority of village communities are also age-friendly communities, providing rich social and civic participation opportunities, respect and social inclusion, community support and health services, communication and information, transportation, and outdoor spaces (Scharlach et al., 2014).

The terms NORC and NORC-SSP are often used interchangeably, yet they have different meanings. Michael Hunt, who wrote the pioneering work in 1990, defined NORCs as neighborhood areas where housing developments were not originally planned or designed for older adults, yet that have aged over time with at least half of residents aged 60+ years (Ormond et al., 2004). NORC-SSP refers to a program that builds collaboration between residents and local health and social service providers to help older adults aging in NORC areas (Bedney et al., 2010; Ormond et al., 2004). These services typically include social-recreational (e.g., yoga classes), educational (e.g., discussion groups and informational sessions), and civic activities (e.g., advisory council meetings) (Greenfield & Mauldin, 2016). Currently, most NORCs have NORC-SSP on-site services and activities to assist older adults with Aging in Community.

The Cohousing Association of the United States supports cohousing communities with shifted cultures toward every home surrounded by caring neighbors. Three aims of cohousing are to (1) help communities maximize opportunities to meet aging needs; (2) provide resources and create collaborative partnerships to address long-term care solutions; and (3) work with the Cohousing Research Network to support policy and practice based on research (The Cohousing Association of the United States, 2020). Senior cohousing is based on shared interests and purposes. It targets older adults over the age of 50 or 55 via universal designs and accessible common areas. Cohousing can benefit older adults socially and economically through mutual support (Wardrip, 2010).

University-based retirement communities (UBRCs) are most appealing to those interested in academic learning and campus life (Bookman, 2008). These communities provide lifelong learning opportunities and university-affiliated hospitals or recreational facilities (Bookman, 2008). Carle (2006) identified five common criteria for UBRCs: (1) close to the university’s main campus; (2) programs integrating community residents with university students, faculty, and staff; (3) inclusion of the full continuum of housing option (e.g., independent and assisted living, skilled nursing, memory care, etc.); (4) a financial relationship between the senior housing provider and the university; and (5) at least 10% of residents having some connection to the university (Carle, 2006). It is essential to note that a UBRC can also be a village, NORC, or cohousing community (Smith et al., 2014).

The Push-Pull Framework

Due to declining health or loss of independence, older adults must often consider alternative aging or housing options. Lee’s (1966) migration model discusses the push-pull factors, including economic, cultural, and environmental aspects. Push factors are unfavorable conditions that led individuals to leave their areas. These could include declining health, financial hardship, or a spouse’s death. Pull factors are favorable conditions that attract individuals toward an area. These could include proximity to family or friends, more activities, or access to health services (Lee, 1966; Stimson & McCrea, 2004; Weeks et al., 2012).

The push-pull framework has been used to explore factors affecting relocation to AIC programs such as villages in Australia, Canada, and other countries (Oztop & Akkurt, 2016; Stimson & McCrea, 2004; Weeks et al., 2012). Few studies in the U.S. have used this framework to examine factors influencing older adults’ aging and housing choices. One study guided by this framework examined the expected housing options among community-dwelling older adults living in New York and found that aging in home/community was still the most likely expected living option (Ewen et al., 2014). Researchers pointed out that new, emerging types of senior housing models should continue to be developed to better inform relocation decisions when needed (Ewen et al., 2014). Given that AIC is the most expected option as one ages, application of the push-pull framework to examine promising AIC models warrants attention.

Gap

Currently, limited studies have synthesized or compared the current development of AIC models. Synthesizing lessons learned from current research is critical to providing updated trends and options for older adults to consider. There are also limited studies exploring how senior living arrangements can meet diverse needs to achieve a person-environment fit. This paper aims to fill this gap by reviewing and synthesizing promising AIC models, analyzing the core characteristics of each model to illustrate person-environment fit, and push-pull factors from older adults’ perspectives. The challenges and recommendations to guide future development are also discussed.

Methods

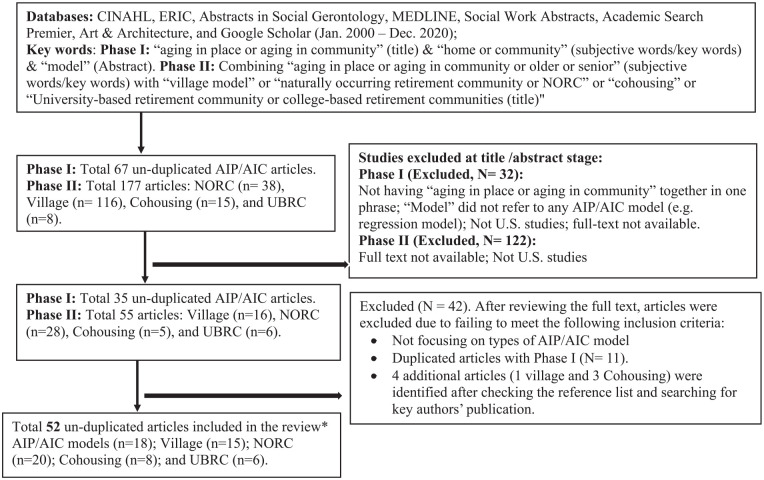

We conducted a comprehensive literature search to answer our research questions: (1) What are the comparative core characteristics of the promising AIC models, and (2) What are the comparative push-pull factors across promising AIC models? Eight scientific databases—CINAHL, ERIC, Abstracts in Social Gerontology, MEDLINE, Social Work Abstracts, Academic Search Premier, Art & Architecture, and Google Scholar—were searched. Studies published from January 2000 and December 2020 were included in this review. Only articles with full text and those conducted in the U.S. were included. Our search process comprised two phases:

Phase I identified existing senior living arrangements or models in the U.S. that support Aging in Community. We combined the phrases “aging in place or aging in community” in the title, “home or community” in subject terms or keywords, and “model” in abstracts in each database. Our initial search yielded 67 studies. Two reviewers screened titles and abstracts. Articles that did not have the “aging in place or aging in community” phrase together, non-U.S. studies, or studies whose full text was not available, were excluded (n = 32). Thirty-five articles met the criteria. After carefully examining the full text, articles not focusing on Aging in Place (AIP) or Aging in Community (AIC) models were excluded. A total of 18 articles met all study criteria and were downloaded into the EndNote database. The authors carefully reviewed each article and identified promising aging in place/community models discussed in each article. We identified four promising AIC models from Phase I analyses. These included the village model, naturally occurring retirement community (NORC), cohousing, and university/college-based retirement community (UBRC).

Phase II further identified articles specifically related to the four promising AIC models. We combined the phrases “village model or villages” or “naturally occurring retirement community or NORC” or “cohousing” or “university-based retirement community or college-based retirement communities” in the title and “aging in place or aging in community or older adults or elderly or seniors” in the keywords. We searched each AIC model separately in each database to ensure the comprehensiveness of relevant articles identified. Phase II yielded 177 articles, including 116 village, 38 NORC, 15 cohousing, and 8 UBRC articles. Articles without full text or non-U.S. studies were excluded (n = 122).

Fifty-five articles in Phase II met the criteria for a full article review. These included 16 village, 28 NORC, 5 cohousing, and 6 UBRC articles. Those not focusing on promising AIC models identified or that were duplicates of the Phase I search were excluded. Eleven duplicate articles were found in Phase II. We categorized all articles identified from both phases into five groups: AIP/AIC models, village, NORC, cohousing, and UBRC. Some articles were included in more than one group (repeated articles). The 11 duplicated articles included 1 for village/NORC/UBRC (repeated 3 times), 2 for NORCs (repeated 1 time), 6 for village (repeated 1 time), and 2 for village/NORC (repeated 2 times), for 15 repeated times. Four articles were added after the reference list was checked and key authors’ publications were searched for. These included 1 village and 3 cohousing articles. Overall, 52 un-duplicated articles (18 AIP/AIC models, 15 village, 20 NORC, 8 cohousing, and 6 UBRC articles) were identified through Phase I and Phase II searches and were downloaded into the EndNote database for review and analysis (Figure 1). We reviewed each article, analyzed core characteristics with attention to person-environment fit, and identified potential push and pull factors. We then conducted comparative core characteristics and push-pull factor analyses across these four promising AIC models.

Figure 1.

Articles searching flowchart.

*Five duplicated articles included 1 for village/NORC/UBRC (repeated 3 times), 2 for NORC (repeated 1 time), 6 for village (repeated 1 time), and 2 for village/NORC (repeated 2 times). This summed a total of 15 duplicated times (1 × 3 + 2 × 1 + 6 × 1 + 2 × 2 = 15).

Results

Core Characteristics of Promising AIC Models in the U.S

Focused areas of various AIC articles can be broadly grouped into two areas: model core characteristics and older adults’ perspectives, which we summarize below. Key research topical areas among village studies included older adults’ well-being, member characteristics, quality of life, retained independence, social cohesiveness, and aging in place (Graham et al., 2014; Hou, 2019, 2020; Lehning et al., 2017). NORC studies focused mainly on service utilization assessment, residents’ and providers’ experience, relocation risk, and active living (Bronstein et al., 2011; Carpenter et al., 2007; Cohen-Mansfield et al., 2013; Grant-Savela, 2010a). Senior cohousing studies discussed mutual support, a sense of community, and social resources (Glass, 2009, 2016, 2020). UBRC studies examined intergenerational connections and the impact on both older adults and younger generations (Montepare & Farah, 2018; Tsao, 2003).

In this review, we focused our analyses of each AIC model on two aspects: model core characteristics and older adults’ perspectives. AIC models highlighted mission, history and current status, core characteristics, subtypes, and services/activities (Table 1). Older adults’ perspectives summarized demographics, roles, pull-push factors, and funding sources by different AIC models (Table 2). A list of articles reviewed by AIC models can be found in Table 3.

Table 1.

Promising AIC Models: Mission/History & Current Status/Core Characteristics/Sub-Type/Services & Activities.

| AIC model | Mission | History & current status | Core characteristics | Subtypes | Services & activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Village model | • Build interdependence • Reduce social isolation • Empower seniors • Reduce care cost • Improve quality of life • Age in place (Scharlach et al., 2012; VtVN, n.d.). |

History

• In 2001, the first village was built in Boston, MA (Greenfield, 2014)Current By 2020 • 250 open villages • 100+ in development (VtVN, n.d.) |

• Spontaneous community • Grassroots • Self-governing • Funded mainly through membership fees • Self-supporting • Vetted discounted providers • Majority of the services provided by volunteers (e.g., community members) (Davitt et al., 2017) |

• Prototypic village • Village with external funding • Aging services with member funding • Aging services organization • Not otherwise specified (Lehning et al., 2017) |

Services

• Services coordination • Volunteer and social services • Discounted care services • Transportation • Information and referrals• (VtVN, n.d.)Activities • Health promotion activities • Civic/Social engagements (Graham et al., 2018; Greenfield et al., 2012) |

| NORC | • Collaborate with service providers • Promote independence • Enhance social connections • Reduce social isolation • AIC (Bedney et al., 2010). |

History

• Began in mid-1980s, 50% of residents aged 60 years or older • Majority in urban and suburban areas (Parker, 2020; Stone, 2013) |

• Spontaneous community • Coordinated professional health/social services onsite • Collaborations among diverse stakeholders • Funded mainly by government funds(Bedney et al., 2010) |

Subtype

• Horizontal models - neighborhood-based (single, semi-detached, or attached housing in suburban/rural) • Vertical models -housing-based (urban high-rise apartments) • Hybrid model Carpenter et al., 2007; Greenfield et al., 2013; Parker, 2020) |

Services

• Care or case management • Meal, housekeeping, personal assistance, or paid escort services • Healthcare and social services (Bedney et al., 2010; Pine & Pine, 2002)• Support groups, counseling, or crisis interventionActivities • Health promotion activities • Social-recreational and civic activities (Greenfield & Mauldin, 2016; Greenfield et al., 2013) |

| Senior Cohousing | • Build social connections • Foster a sense of community • Mutual support (The Cohousing Association of the United States, 2020) |

History

• First U.S. senior cohousing in 2006 (Glass, 2013 Current • More than a dozen were established, with more than a dozen in process (The Cohousing Association of the United States, 2017) |

• Intentional community • Have common areas to facilitate social connection • Planned and designed by older adults themselves • Self-management and decision-making • Shared values • Green living (The Cohousing Association of the United States, 2020) |

• Intergeneration cohousing • Senior cohousing (The Cohousing Association of the United States, 2017) |

• Common meals • Outdoor, indoor maintenance and cleaning • Shared hobby, exercise activities, special events • Residents’ association meetings • Steering committee/board committees (Glass, 2013) |

| UBRC | • Lifelong learning • Stay intellectually active • Improve quality of life (Bookman, 2008; Montepare & Farah, 2018) |

Current

• By 2020, 96 UBRCs built in the U.S., with six additional in development (Retirement Living Information Center, 2020) |

• Close to the university • Access to campus activities/services • Financial relationships to the university (Carle, 2006) |

Subtype

• University provides only academic and social programs • University involved in community development and program provision • University operates Harrison & Tsao, 2006) |

Services

• University-affiliated institutions (e.g., university-affiliated hospitals, art colleges, etc.) |

Note. NORC = naturally occurring retirement communities; UBRC = university-based retirement communities.

Table 2.

Older Adult’s Demographics/Role of Older Adults/Pull and Push Factors/Funding.

| AIC model | Demographics | Role of older adults | Push-pull factors | Funding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Village model | • Majority white • Highly educated • Majority female • Middle-higher income • About 50% live alone (Bookman, 2008; Graham et al., 2014, 2017; Hou, 2020) |

• Direct leadership • Decision-makers • Community volunteers (Greenfield et al., 2013) |

Push factors

• Requiring membership fees Pull factors • Social connection • Free or low-cost services (Greenfield et al., 2012; Scharlach et al., 2012) |

• Self-funded • Membership dues • Gifts or donations (Greenfield et al., 2012; Scharlach et al., 2012) |

| NORC | • Majority single or live alone (60%–80%) • Mean age (78–82 years) (Carpenter et al., 2007; Cohen-Mansfield et al., 2013) • Multicultural, multi-lingual populations • Middle-to-low income older adults • Lower education (Bookman, 2008; Greenfield et al., 2013; Usher, 2014) |

• Partners and leaders • Collaboration with professional providers • Volunteers (Greenfield et al., 2013; Guo & Castillo, 2012) |

Push factors

• Declining health, loss of independence or autonomy (Carpenter et al., 2007) Pull factors • Services and activities • Sense of community • Social connection • Reduce health care costs (Elbert & Neufeld, 2010; Guo & Castillo, 2012) |

• Government-funded services (majority) • Private philanthropy (some) (Bookman, 2008) |

| Senior cohousing | • Middle-higher income • Highly educated • Majority whites • Majority homeowners • Fewer disabled (Glass, 2013, 2020) |

• Direct leadership • Decision-makers • Service providers • Participants (Glass, 2013, 2020) |

Push factors

• Expensive • Limited availability (Glass, 2013) Pull factors • Place identity and autonomy • Mutual support and help • Sense of safety and security • Social engagement and empowerment (Glass, 2009, 2016; Grant-Savela, 2010a; Guo & Castillo, 2012; Kramp, 2012) |

• Private funded • Government support (Glass, 2013) |

| UBRC | • Majority aged 65+ • Middle to higher-income individuals (Bookman, 2008) |

• Senior students (Bookman, 2008) • Teaching young generations • Peer educators (Tsao, 2003) |

Push factors

• Expensive (Bookman, 2008) • Full-semester schedule may be inconvenient (Montepare & Farah, 2018) Pull factors • Educational and cultural activities • High quality, university-affiliated hospitals (Bookman, 2008) • Personal fulfillment and growth • Intergenerational connection (Tsao, 2003) |

• Private funded (Bookman, 2008) • Financial connection to the university (Montepare et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2014) |

Note. NORC = naturally occurring retirement communities; UBRC = university-based retirement communities.

Table 3.

List of Articles Reviewed by AIC Model Types.

Note. Among duplicated articles, 1 for village/NORC/UBRC (repeated 3 times); 2 for NORC (repeated 1 time); 6 for village (repeated 1 time); 2 for village/NORC (repeated 2 times).

1 for village/NORC/UBRC (repeated 3 times): (Bookman, 2008).

2 for NORC (repeated 1 time): (Bedney et al., 2010; Guo & Castillo, 2012).

6 for village (repeated 1 time): (Graham et al., 2018; Gammonley et al., 2019; Hou, 2020; LeFurgy, 2017; McDonough & Davitt, 2011; Scharlach et al., 2012).

2 for village/NORC (repeated 2 times): (Greenfield et al., 2012, 2013).

Mission

Overall, all AIC models share similar missions in building social connection and supportive services to help older adults aging-in-community, yet with different approaches and focuses.

The village model aims to reduce social isolation, build interdependence, improve social engagement, reduce care costs, and enhance older adults’ life purposes (McDonough & Davitt, 2011; VtVN, n.d.). It is founded, led, and funded primarily by older adults themselves (McDonough & Davitt, 2011; VtVN, n.d.). NORC-SSP coordinates healthcare and social services and group activities in the community to promote residents’ independence and healthy aging (Bedney et al., 2010). The membership-based village model was developed outside of existing health and social service systems and is served mainly by older adults themselves (VtVN, n.d.). In contrast, the NORC program model emphasizes collaborations among diverse stakeholders, such as health and social service providers, government agencies, and philanthropic organizations (Vladeck, 2004). Thus, the village model provides services mainly through volunteers (village members) instead of professional health and social services provided by paid staff (Greenfield et al., 2013). Senior cohousing is an intentional community design to build a sense of community and mutual support by creating age-friendly physical and social environments that allow residents to flourish as they age (Glass, 2009, 2012, 2013, 2020; Markle et al., 2015; The Cohousing Association of the United States, 2020). The design features common meals, large common areas (e.g., kitchen, dining space, and gardens), and smaller individual homes. It brings people together and allows them to interact in common areas (The Cohousing Association of the United States, 2020). The mission of UBRC is to connect older adults with higher education institutions for lifelong learning opportunities so that they can stay intellectually active (Bookman, 2008; Carle, 2006; Montepare & Farah, 2018).

History and current status

The village model, senior cohousing, and UBRC emerged in the U.S. between 2002 and 2006, while the NORC has the longest history. A group of residents of the Beacon Hill Village of Boston, MA founded the first village in 2002. Currently, more than 250 villages have opened, with at least an additional 100 villages in development (VtVN, n.d.). NORC-SSP development began in the mid-1980s, mostly in urban and suburban areas (Parker, 2020; Stone, 2013). The current state of NORCs isn’t very well documented, with limited data available. In New York State, it is estimated that of approximately 1.25 million seniors in the city, about 400,000 live in NORCs and access NORC-SSP (Montgomery, 2020).

The Cohousing concept is a form of intentional community imported to the United States from Denmark in the late 80s. AARP reported that nearly all cohousing communities in the U.S. are intergenerational, open to families of all kinds and to individuals of all ages. Senior cohousing incorporated all the principles of the intergenerational cohousing model with features accommodating the needs of older adults (Wardrip, 2010). The first U.S. senior cohousing was built in 2006 (Glass, 2013). By 2017, more than a dozen senior cohousing communities across the country were established, with more than a dozen under development (The Cohousing Association of the United States, 2017).

The term “university-based retirement community” (UBRC) was coined in 2006 by Andrew Carle, founder of George Mason University’s program in senior housing administration. By 2020, 96 UBRCs had been built in the U.S., with six in the development stage (Retirement Living Information Center, 2020). Today, villages have been widely and rapidly developing. UBRC is also emerging, while senior cohousing is the slowest in development.

Core characteristics

Although all AIC models share similar purposes, core characteristics vary somewhat to better serve older adults with different characteristics. Village programs are grassroots, self-governing, self-supporting, and membership-driven, using voluntary resources from community residents and connecting members with vetted discounted services and activities (Davitt et al., 2017). NORC-SSP programs are mostly started and coordinated by formal social service agencies, with coordinated on-site social and healthcare services; often, they also incorporate volunteers to coordinate and provide services (Bedney et al., 2010; Guo & Castillo, 2012). Senior cohousing typically serves individuals 55 years or older. Cohousing residents live in their private homes and have access to shared spaces, including leisure areas, gardens, and community kitchens. Typically, homes are single-level and are built with wheelchair accessibility, grab bars, and other supportive features (Glass & Vander Plaats, 2013; The Cohousing Association of the United States, 2020). UBRCs are normally close to universities, with easy access to campus activities and services and some financial connection; at least 10% of residents are connected to the university (Carle, 2006).

Overall, both village and cohousing are organized and managed by older adults and take advantage of older adults’ mutual support capability. The major difference is that senior cohousing is an intentionally designed and built community, and thus has limited availability. Cohousing residents are usually involved in the community planning to design stages (The Cohousing Association of the United States, 2020). Villages are developed spontaneously in already-established places instead of an intentional community design (Thomas & Blanchard, 2009). The original design of houses in villages does not take older adults’ needs into primary consideration (e.g., age-friendly design, social interaction, shared facilities). Village members also are not typically involved in the village housing design stage phase. Instead, village members are involved mainly in the governance and service provision stage (Davitt et al., 2017). NORC residents rely mostly on professional on-site services coordinated by social service agencies. NORC older adults have less engagement in either design or governance. The membership fee is a requirement for joining a village, but not for NORC. UBRC differs by connecting members to educational and cultural opportunities, as well as recreational and medical facilities on campus. UBRCs include individual housing units designed for older adults. These can be single-family homes, neighborhoods with condos or townhouses, or apartment-style living near campus. Many UBRCs are within walking distance of campus without driving. Some include continuum of care offering assisted living services or memory care facilities (Senior List, 2021).

Subtype and housing type

While there is no standard village model, researchers have categorized villages into four subtypes based on the extent of member involvement, methods of service provision, and funding sources (Lehning et al., 2017): (1) prototypic village with prominent member involvement, (2) village with external funding, (3) aging services with member funding, and (4) not otherwise specified (Davitt et al., 2017; Lehning et al., 2017).

NORCs can be age-integrated apartments, single-family homes, or condos (Carpenter et al., 2007; Greenfield et al., 2013). There are two broad subtypes of NORC-SSP: housing-based NORCs and neighborhood-based NORCs. Housing-based NORCs (also called “classic”, “closed”, or “vertical” NORCs) are typically multi-family apartment buildings, either a housing complex with multiple buildings under common management or a cluster of apartment buildings. These often have distinct boundaries and are located in major metropolitan areas (Bronstein & Kenaley, 2010; Enguidanos et al., 2010). Neighborhood-based NORCs (“open” or “horizontal” NORCs) are defined geographically and rarely have distinct boundaries. These are often located in small, low-density neighborhood areas in small cities, suburbs, and rural areas, and are composed of a mixture of housing types including single-family homes (Bronstein & Kenaley, 2010; Enguidanos et al., 2010). Cohousing can be individually owned or owned via a housing cooperative. From a resident’s perspective, cohousing can be intergenerational or senior (The Cohousing Association of the United States, 2017). Finally, there are three types of UBRCs: (1) university-only provides academic and social programs; (2) university involves the provision of both community development and academic and social programs; and (3) university directly operates and manages the facility (Harrison & Tsao, 2006).

Services and activities

Village and NORC-SSPs provide similar services/activities that can be grouped into three categories: (a) civic engagement and empowerment, (b) social relationship-building activities, and (c) services to enhance participants’ access to resources (Greenfield et al., 2012). Villages programs are mostly led by older adults, involving both members and non-members as volunteers to provide group, health promotion, and civic engagement activities (Graham et al., 2018; Greenfield et al., 2012; VtVN, n.d.); while NORC-SSP is led mostly by formal service providers and partners with various stakeholders (Greenfield et al., 2012). NORC-SSP services normally include care or case management, meals, housekeeping, personal help, home chores, and social work services (Bedney et al., 2010; Pine & Pine, 2002). Other community activities include social-recreational (e.g., yoga classes, trips), educational and civic (e.g., advisory council meetings), support groups, counseling, and crisis intervention (Greenfield & Mauldin, 2016; Greenfield et al., 2013; Pine & Pine, 2002). Compared to villages, NORC programs have about twice paid staff (58% vs. 29%) and had fewer volunteers (14% vs. 46%) (Greenfield et al., 2013).

Senior cohousing regularly brings together residents in the common areas. It provides shared community activities, such as close social coffee breaks, weekly potluck dinners, hobby groups, exercise activities, outdoor/indoor maintenance and cleaning, special events, and steering committee/board/residents’ association committees (Glass, 2013; The Cohousing Association of the United States, 2020). It invests in paid services only when members consider them necessary (Kramp, 2012). UBRC is distinct from the other three models. It provides academic life involvement for older adults, including cultural events, college or lifelong learning courses, and access to university-affiliated healthcare and recreational facilities (Bookman, 2008; Montepare et al., 2019). In contrast, UBRC rarely provides supportive services, such as meals, housekeeping, or personal care.

Older Adult Characteristics and Perspectives

Demographics

Most village members, senior cohousing residents, and UBRC residents are white or middle-to-high class, whereas NORC participants have more racial-ethnic diversity or have middle-to-low incomes and lower education (Bookman, 2008; Greenfield et al., 2013; Usher, 2014). Most village members and senior cohousing residents were female, younger, with fewer disabilities, and lived alone (Bookman, 2008; Graham et al., 2014, 2017; Greenfield et al., 2013). Few studies have compared demographics among older adults taking part in different AIC programs. Hou (2019) was among the first to conduct direct comparisons of demographics among older adults in three AIC programs: two village programs, a county-wide neighborhood lunch program (NLP), and a university-based lifelong learning program (LLP) in a southern U.S. state. Most participants were older women (78%). Data further showed that village participants had more members aged less than 64 years and NLP had more residents aged 85 years or older, while LLP members were mostly between 65 and 74 years (p < .001). Data also showed that more village members were living alone (46%) as compared to NLP (35%) and LLP (25%) (p < .05) (Hou, 2019).

Role of older adults

Village older adults are decision-makers with direct leadership in every aspect of initiatives, including the provision of services by serving as community volunteers (Greenfield et al., 2013; McDonough & Davitt, 2011). NORC-SSP older adults are partners with lead agency professionals and other stakeholders including service and housing providers (Greenfield et al., 2013, 2014; McDonough & Davitt, 2011). Senior cohousing older adults are also decision-makers, service providers, and participants. UBRC older adults are senior students or peer educators, or contribute to inter-generational knowledge-sharing and relationship-building (Bookman, 2008; Montepare et al., 2019; Tsao, 2003).

Push-pull factors

Pull factors are often programmatic factors, such as the appeal of the services/activities (e.g., reduced-cost services, social connection), benefits of enrollment (e.g., sense of community, mutual support, intergenerational connections), active living opportunities, and relationships with staff (Gammonley et al., 2019; Glass, 2016; Greenfield & Mauldin, 2016; Tsao, 2003; Wickersham, 2015). Most village and NORC programs are similar in that their most important goals are to promote older adults’ access to services (71% of villages and 66% of NORC programs), strengthen social relationships, and reduce social isolation (25% of villages and 30% of NORC programs) (Greenfield et al., 2013). Studies show that 90% of cohousing residents agree that cohousing also promoted social resources, community support, and reduced social isolation (Glass, 2016, 2020; Glass & Vander Plaats, 2013). Cohousing studies reported that environmental factors and surrounding town areas—such as common areas for conversation, natural lighting with outdoor views, and energy efficiency features in the living environment—are attractive (Glass, 2020; Kramp, 2012). Village and cohousing share similar pull factors in terms of autonomy/self-governing (Kramp, 2012; Scharlach et al., 2012).

Pull factors for AIC models differ in several ways, which may affect their ability to recruit and serve diverse groups. NORCs provide more professional social and health services through paid staff (Greenfield et al., 2013), while village and cohousing mainly offer services and support from older adults themselves. Cohousing has the unique pull motivations of living with people sharing the same interest and downsizing of the house (Glass, 2020; Kramp, 2012). UBRC draws members interested in lifelong learning and intergenerational opportunities, living with people sharing similar backgrounds, and promoting personal growth and self-actualization as one ages (Tsao, 2003). Overall, service provision and social connection are two major pull factors for the village and NORC (Greenfield et al., 2013); mutual support and sense of community are the major pull factors for cohousing (Glass, 2012, 2016); and lifelong learning and intergenerational relationships are the key pull factors for the UBRC (Bookman, 2008; Tsao, 2003).

Push factors are often individual circumstances, including social demographic condition, declining health condition/independence, financial constraints, or decreased desires for social activities (Gammonley et al., 2019; Glass, 2016; Greenfield & Mauldin, 2016; Tsao, 2003). One village study reported that the oldest group, aged 85 and above, was less likely to consider joining the village (Gammonley et al., 2019). On the other hand, older adults who engage in preventative health behaviors, have adequate resources, and identify potential benefits for enrollment were more willing to join the village (Gammonley et al., 2019). Data show that 26% of NORC residents believed that they might have to move elsewhere in the future due to declining health, financial constraints, or an inability to navigate safely, maintain their home, or preserve social connections (Carpenter et al., 2007). Older adults may have difficulty finding senior cohousing because of limited availability and costs beyond their budget. Additional push factors include adaptations necessary to balance privacy and shared boundaries, and adjusting to alternative lifestyles and neighbors with different personalities (Glass, 2013). Cohousing’s mutual support culture might present a potential conflict with the traditional American values of individualism and independence (Glass, 2013). Regarding UBRC push factors, the semester-long campus schedule or full-length classes may be inconvenient or less interesting to some older adults (Montepare & Farah, 2018). Overall, seniors’ declining physical and cognitive conditions are common push factors for all AIC models. These factors reduce older adults’ abilities to volunteer or lead in the village, take part in activities, or provide mutual support.

AIC communities and programs have the potential to delay institutionalized care compared to older adults not living in AIC communities. A NORC program evaluation study analyzing 6-year data reported its nursing home placement rate was 2%, which was lower than the national average rate of 4.5% and the state average of 4.8% (Elbert & Neufeld, 2010). This study also compared data of NORC members with data of non-members during the previous 1-year period and found that non-members had a 7.1% nursing home placement rate compared to a 3.2% rate for members (Elbert & Neufeld, 2010). The study showed that, compared to demographically similar non-cohousing residents, cohousing residents both give and receive significantly more socially supportive behaviors including emotional, instrumental, informational, and appraisal behaviors (Markle et al., 2015). A village study showed that village members were more likely to maintain residential normalcy and age in community longer than non-members because they had access to supportive resources (LeFurgy, 2017).

Funding

Villages are typically grass-roots initiatives and mostly self-funded through membership and donations (Greenfield et al., 2012, 2013; Scharlach et al., 2012). Unlike villages, NORC-SSP relies mainly on government grants and contracts, with some from a parent organization, instead of membership fees (Bookman, 2008; MacLaren et al., 2007; Vladeck & Altman, 2015). Data show that government grants and contracts comprised about two-thirds of NORC programs’ budgets and only less than 3% in villages (Greenfield et al., 2013). In contrast, membership dues comprised almost half of villages’ budgets and only less than 2% in NORC communities. Villages also rely on fund-raising and charitable donations (Greenfield et al., 2013). Senior cohousing is privately funded with some government support (Glass, 2013). UBRCs have financial relationships with universities but still rely on private funds for participation (Bookman, 2008; Smith et al., 2014).

Discussion

Aging in Community (AIC) is an ideal ideology that can help older adults achieve their desired way of aging. Its essence is that everyone works together to create a mutually supportive neighborhood to enhance older adults’ physical and social well-being and quality of life, and maximize independence to remain in their own homes and communities (Thomas & Blanchard, 2009; Blanchard, 2013). It underlines the importance of the human and the environment simultaneously. The environment should be supportive and affordable; older adults age together by building social connections with peers and the younger generation (Blanchard, 2013). From the Ecological Theory of Aging (ETA) perspective, AIC can achieve the person-environment fit by matching personal resources with environmental resources (Wahl et al., 2012). For example, AIC programs provide volunteer and civic opportunities for people who have higher autonomy and provide tangible and social support for individuals with declined independence.

This review synthesized four promising AIC models from core model characteristics and older adult participant perspectives, including analyzing the push-pull factors of each model. We found that all four models provide a variety of preventive and supportive activities to meet older adults’ agency belongingness needs (Bookman, 2008; Greenfield et al., 2012; Kramp, 2012).

The current review finds that, except for NORC residents, most older adults taking part in the promising AIC programs are white, middle-to-high income, and highly educated (Bookman, 2008; Glass, 2013; Graham et al., 2017; Hou, 2019). This observation is consistent with existing studies showing that low-income, and even middle-income, older adults face the challenge of aging in place, mainly caused by financial insecurity (Lavery, 2015; Pearson et al., 2019; US Department of Housing Urban Development, 2013). Although several government programs support low-income older adults in the community, there is only limited support for the cost, such as village membership fees, senior cohousing, or UBRC tuition (US Department of Housing Urban Development, 2013). Middle-class older adults may not qualify for Medicaid home or community-based care services or subsidized housing support services and may not be able to pay for in-home care, home modifications, or village membership dues (US Department of Housing Urban Development, 2013).

Ethnic and racial minorities, especially those who do not speak or are not fluent in English, may have different needs or preferences that the existing white-dominated AIC models cannot provide (Lehning et al., 2017). Minorities are underrepresented in these promising AIC programs. This may be explained by cultural preferences, value systems, language barriers, and financial challenges (Pandya, 2005). For example, Asian culture values family members taking care of their parents. Thus, Asian older adults who are not fluent in English may age in place with their English-speaking children in their own communities instead of in the AIC models discussed (Pandya, 2005). Asians or other ethnic older adults may also be less likely to build strong social connections with English-speaking older adults and may prefer to receive help from those who are of the same race/ethnicity (Pandya, 2005). Studies also show that white participants are more likely to report freedom of choice and control of their living arrangements than blacks (Fabius & Robison, 2019). Older blacks, Hispanics, and Asian Americans are more likely than whites to live in multigenerational households or with other relatives (Fabius & Robison, 2019; Guzman & Skow, 2019). Studies show that, compared to whites, older African Americans might prefer living alone over living with a stranger (Fabius & Robins, 2019) as black older adults have larger and stronger extended kin networks to provide informal care if needed (Peek & O’Neill, 2001). Overall, limited research focuses on racial/ethnic minority older adults’ AIC experience. Thus, research is needed to address this critical knowledge gap.

The current review found that NORC residents were more diverse in terms of ethnic/racial groups and older in mean age ranges (78–82 years). They were also more likely to be single or live alone (60%–80%) and to have lower education and moderate-to-low incomes (Bookman, 2008; Carpenter et al., 2007; Cohen-Mansfield et al., 2013; Greenfield et al., 2013; Usher, 2014). Studies show that older adults with these demographic characteristics are more likely to perceive lower social cohesiveness or live in economically disadvantaged and low-cohesion neighborhood areas (Ailshire & García, 2018; Hou, 2020). These individuals were also more likely to experience declines in physical and cognitive functioning, thus further limiting their social and civic participation (Carpenter et al., 2007). Therefore, NORC “supportive service programs” (SSP) could help provide residents with tangible support while also meeting their belongingness needs through additional social connection activities (Ailshire & García, 2018).

The main relocation push factor for older adults is that the physical environment cannot support older adults in maintaining autonomy or independence (Geboy et al., 2012). Push and pull factors are often embedded in the relocation decision. Push factors related to relocation are associated mainly with the loss of autonomy, such as maintaining the home or fear of being a burden on the family. Pull factors may include proximity to family, needed services, or amenities that may compensate for perceived autonomy losses (Geboy et al., 2012). This literature review shows that AIC communities have many promising pull factors to support older adults’ autonomy by providing age-friendly houses and communities, health services, financial management, social engagement, and public transportation (National Aging in Place Council, 2021).

As one’s physical and cognitive health condition and functional capability decrease because of aging or illness and financial constraint, one’s agency might decrease (e.g., maintain home, preserve social connections). Belongingness needs (e.g., place attachment, sense of community) may increase. These dynamic changes in role and needs may lead to a person-environment unfit, and, thus, a push factor from Aging in Community (Gammonley et al., 2019; Glass, 2016; Greenfield & Mauldin, 2016; Tsao, 2003). For example, unmarried older women, living alone and experiencing a loss of independence, may have higher needs to move out of NORC to institutional care (Carpenter et al., 2007), while older adults aged 85 and above may be less likely to join a village (Gammonley et al., 2019). Existing evidence suggests that village programs may have a protective effect until 85 years. A study showed perceived quality-of-life stayed similarly high across age groups and dropped significantly once an individual reached the oldest age (Hou et al., 2017). Data showed push factors for cohousing include limited availability, affordability, and getting along with neighbors (Glass, 2013; The Cohousing Association of the United States, 2017), while the full-semester schedule may be less attractive for some older adults, resulting in decreased motivation to stay in UBRCs (Montepare & Farah, 2018).

These dynamic changes in role and needs among older adults pose challenges to the sustainability of AIC models. As village members get older, community members’ engagement may decrease; thus, village programs may need to consider engaging new and younger members with the capacity to provide volunteer services and management (Bookman, 2008; Greenfield et al., 2012, 2013; Greenfield & Frantz, 2016; Hou, 2019). The challenges of NORC-SSP include ensuring that organized services and activities continue to meet the diverse aging needs and help older adults achieve a person-environment fit while maintaining the program’s effectiveness and efficiency. NORCs seem to be able to serve diverse older adults, and thus may want to share lessons learned on program experience, such as providing group meals with regular social opportunities (Hou, 2019). UBRCs have been successful in attracting newly retired older adults and may consider incorporating additional supportive services as members age (Hou, 2019). Other common challenges include the unstable and unsustainable funding to all AIC models and programs (Greenfield, 2013; Hou, 2019, 2020). Diversified financing, including government, private donations, and nonprofit organizations, may be more financially secure and is recommended (Greenfield, 2013; Greenfield et al., 2013).

Limitations

Although we tried to be comprehensive with a broad range of databases and a long 20-year timeframe, the search is limited by publication bias, database limitations, search term restrictions, and the unavailability of full-text articles. We limited our review to studies that were U.S.-based and published in English. We recognize that there are other promising AIC models outside the U.S.; thus, we encourage researchers to continue sharing lessons learned and perhaps conducting cross-cultural or cross-country comparisons to better identify AIC models and practices to address challenges in our rapid global aging populations.

Recommendation

Our review showed that each AIC model shares similar goals, with somewhat different focuses to meet diverse aging population needs. The arrangements of these services and activities should adapt if members’ roles change due to declining health, decreased social participation, or increased belongingness needs (Cohen-Mansfield et al., 2013; Gammonley et al., 2019). Evidence-based research data show that tailored programs and services to facilitate older adults aging in communities are needed (Hou, 2019, 2020). Practitioners and coordinators working with community-based aging programs should develop tailored services and activities considering the diverse demographic characteristics and background among older adults to meet their needs.

Overall, NORC residents are culturally and linguistically diverse, while village, senior cohousing, and UBRC residents are relatively homogenous in race ethnicity (Bookman, 2008; Glass, 2020). To attractive diverse older adults, more affordable and culturally tailored activities or services are needed (Bucknell, 2019; Hou, 2020). For example, villages may consider recruiting volunteers with divers background, subsidizing membership fee and increase the proportion of public funding. Public programs may consider support low- to moderate-income families who wish to live in cohousing neighborhoods. It is also necessary to identify cost-effective ways to retrofitting the current environment to meet older people’s changing needs (Glass, 2020). University may consider collaborate with affordable senior housing or places serving minority or lower income older adults, such as NORCs. It’s also important to note that Asians, Hispanic, or other racial minority older adults are more likely to live intergenerationally (Bucknell, 2019). Villages’ current individualized consumer-oriented service model may not be culturally congruent with ethnic minority cultural values (Scharlach et al., 2012). Family-centered approaches developed collaboratively with existing ethnic faith-based and cultural organizations may be explored.

Service providers should also consider push-pull factors from older adults’ perspectives. This can help AIC coordinators provide services and activities that are best suited for their particular context and members served. Mixed methods and qualitative research are needed to gain nuanced discovery and uncover the voice and needs of diverse older adults (Creswell & Clark, 2018; Hou, 2019). With the rapidly growing aging population globally, and especially in Asia, there continue to be emerging innovative models and experiences to share. Diverse culturally sensitive community-based and facility-based senior living and healthcare models must be identified and developed worldwide.

Conclusion

This study identified four promising AIC models: village, NORC, cohousing, and UBRC. The results suggest that all the identified AIC models have the potential to achieve person-environment fits by meeting older adults’ needs. Each model also has its push-pull factors and unique ways of helping older adults with different needs aging in communities. The demands of older adults and environments should be viewed as a dynamic process, especially in the village and senior cohousing community, as members are the major service providers for each other. When older adults’ capabilities are challenged, the environment should provide supportive service and activities to facilitate their Aging in Community. This study synthesized current lessons learned from promising AIC models in the U.S. Continued AIC research is needed to explore barriers to involve low-income individuals and minorities in different AIC models and meet their diverse and dynamic needs. Comparative studies to share lessons learned across the globe are also needed.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: IRB approval numbers—This study has been approved as an exempt study by the UCF Institutional Review Board (SBE-17-12893). A cover page with consent information was provided with the paper-survey version and “click-through consent page” for the online survey version, before participants voluntarily agreed to take part of the anonymous survey.

ORCID iD: Su-I Hou  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4519-0974

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4519-0974

References

- Ailshire J., García C. (2018). Unequal places: The impacts of socioeconomic and race/ethnic differences in neighborhoods. Generations, 42(2), 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bedney B. J., Goldberg R. B., Josephson K. (2010). Aging in place in naturally occurring retirement communities: Transforming aging through supportive service programs. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 24(3/4), 304–321. 10.1080/02763893.2010.522455 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard J. M. (2013). Aging in community: The communitarian alternative to aging at home, alone. Generations, 37(4), 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bookman A. (2008). Innovative models of aging in place: Transforming our communities for an aging population. Community, Work & Family, 11(4), 419–438. 10.1080/13668800802362334 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein L., Gellis Z. D., Kenaley B. L. (2011). A neighborhood naturally occurring retirement community: Views from providers and residents. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 30(1), 104–112. 10.1177/0733464809354730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein L., Kenaley B. (2010). Learning from vertical NORCs: Challenges and recommendations for horizontal NORCs. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 24(3–4), 237–248. [Google Scholar]

- Bucknell A. (2019). Aging in place: For America’s older adults, access to housing is a question of race and class. https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/2019/10/aging-in-place-for-americas-older-adults-access-to-housing-is-a-question-of-race-and-class/

- Carle A. (2006). University-based retirement communities: Criteria for success. https://www.iadvanceseniorcare.com/university-based-retirement-communities-criteria-for-success/

- Carpenter B. D., Edwards D. F., Pickard J. G., Palmer J. L., Stark S., Neufeld P. S., Morrowhowell N., Perkinson M. A., Morris J. C. (2007). Anticipating relocation: Concerns about moving among NORC residents. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 49(1–2), 165–184. 10.1300/J083v49n01_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chum K., Fitzhenry G., Robinson K., Murphy M., Phan D., Alvarez J., Hand C., Rudman D. L., McGrath C. (2020). Examining community-based housing models to support aging in place: A scoping review. The Gerontologist. Advance online publication. 10.1093/geront/gnaa142 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Mansfield J., Dakheel-Ali M., Frank J. K. (2010). The impact of a naturally occurring retirement communities service program in Maryland, U.S.A. Health Promotion International, 25(2), 210–220. 10.1093/heapro/daq006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J., Dakheel-Ali M., Jensen B. (2013). Predicting service use and intent to use services of older adult residents of two naturally occurring retirement communities. Social Work Research, 37(4), 313–326. 10.1093/swr/svt026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J., Clark V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Davitt J. K., Greenfield E., Lehning A., Scharlach A. (2017). Challenges to engaging diverse participants in community-based aging in place initiatives. Journal of Community Practice, 25(3–4), 325–343. 10.1080/10705422.2017.1354346 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elbert K. B., Neufeld P. S. (2010). Indicators of a successful naturally occurring retirement community: A case study. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 24(3–4), 322–334. 10.1080/02763893.2010.522440 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enguidanos S., Pynoos J., Denton A., Alexman S., Diepenbrock L. (2010). Comparison of barriers and facilitators in developing NORC programs: A tale of two communities. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 24(3–4), 291–303. [Google Scholar]

- Ewen H. H., Hahn S. J., Erickson M. A., Krout J. A. (2014). Aging in place or relocation? Plans of community-dwelling older adults. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 28(3), 288–309. [Google Scholar]

- Fabius C. D., Robison J. (2019). Differences in living arrangements among older adults transitioning into the community: Examining the impact of race and choice. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 38(4), 454–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammonley D., Kelly A., Purdie R. (2019). Anticipated engagement in a village organization for aging in place. Journal of Social Service Research, 45(4), 498–506. 10.1080/01488376.2018.1481169 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geboy L., Moore K. D., Smith E. K. (2012). Environmental gerontology for the future: Community-based living for the third age. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 26(1–3), 44–61. [Google Scholar]

- Glass A. P. (2009). Aging in a community of mutual support: The emergence of an elder intentional cohousing community in the United States. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 23(4), 283–303. 10.1080/02763890903326970 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glass A. P. (2012). Elder cohousing in the United States: Three case studies. Built Environment, 38(3), 345–363. [Google Scholar]

- Glass A. P. (2013). Lessons learned from a new elder cohousing community. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 27(4), 348–368. 10.1080/02763893.2013.813426 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glass A. P. (2016). Resident-managed elder intentional neighborhoods: Do they promote social resources for older adults? Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 59(7–8), 554–571. 10.1080/01634372.2016.1246501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass A. P. (2020). Sense of community, loneliness, and satisfaction in five elder cohousing neighborhoods. Journal of Women & Aging, 32(1), 3–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass A. P., Vander Plaats R. S. (2013). A conceptual model for aging better together intentionally. Journal of Aging Studies, 27(4), 428–442. 10.1016/j.jaging.2013.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham C., Scharlach A. E., Kurtovich E. (2018). Do villages promote aging in place? Results of a longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 37(3), 310–331. 10.1177/0733464816672046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham C. L., Scharlach A. E., Price Wolf J. (2014). The impact of the “village” model on health, well-being, service access, and social engagement of older adults. Health Education & Behavior, 41(Suppl. 1), 91S–97S. 10.1177/1090198114532290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham C. L., Scharlach A. E., Stark B. (2017). Impact of the village model: Results of a national survey. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 60(5), 335–354. 10.1080/01634372.2017.1330299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant-Savela S. D. (2010. a). The influence of self-selection on older adults’ active living in a naturally occurring retirement community. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 24(1), 74–92. 10.1080/02763890903326996 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grant-Savela S. D. (2010. b). Active living among older residents of a rural naturally occurring retirement community. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 29(5), 531–553. 10.1177/0733464809341470 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield E. A. (2013). The longevity of community aging initiatives: A framework for describing NORC programs’ sustainability goals and strategies. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 27(1/2), 120–145. 10.1080/02763893.2012.754818 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield E. A. (2014). Community aging initiatives and social capital: Developing theories of change in the context of NORC supportive service programs. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 33(2), 227–250. 10.1177/0733464813497994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield E. A., Frantz M. E. (2016). Sustainability processes among naturally occurring retirement community supportive service programs. Journal of Community Practice, 24(1), 38–55. 10.1080/10705422.2015.1126545 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield E. A., Mauldin R. L. (2016). Participation in community activities through naturally occurring retirement community (NORC) supportive service programs. Ageing & Society, 37(10), 1987–2011. 10.1017/S0144686X16000702 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield E. A., Scharlach A., Lehning A. J., Davitt J. K. (2012). A conceptual framework for examining the promise of the NORC program and Village models to promote aging in place. Journal of Aging Studies, 26(3), 273–284. 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.01.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield E. A., Scharlach A. E., Lehning A. J., Davitt J. K., Graham C. L. (2013). A tale of two community initiatives for promoting aging in place: Similarities and differences in the national implementation of NORC programs and villages. The Gerontologist, 53(6), 928–938. 10.1093/geront/gnt035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo K., Castillo R. (2012). The U.S. long term care system: Development and expansion of naturally occurring retirement communities as an innovative model for aging in place. Ageing International, 37(2), 210–227. 10.1007/s12126-010-9105-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman S., Skow J. (2019). Multigenerational housing on the rise, fueled by economic and social changes. https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2019/06/multigenerational-housing.doi.org.10.26419-2Fppi.00071.001.pdf

- Harrison A., Tsao T. C. (2006). Enlarging the academic community: Creating retirement communities linked to academic institutions. Planning for Higher Education, 34(2), 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hou S.-I. (2019). Promoting aging-in-community – Lessons learned from demographic characteristics of older adults participating in three community-based programs [Conference session]. The 8th Annual Global Healthcare Conference (G.H.C. 2019) Proceedings, Singapore, pp. 9–13. 10.5176/2251-3833_GHC19.133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hou S.-I. (2020). Remain independence and neighborhood social cohesiveness among older adults participating gin three community-based programs promoting aging-in-community in the USA. Gerontology & Geriatric Medicine. Advance online publication. 10.1177/2333721420960257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hou S.-I., Niec G., Kinser P., Cummings D. (2017). Quality of life among young old, old, old old, and the oldest in the thriving village. Innovation in Aging 1(Suppl. 1): 722. 10.1093/geroni/igx004.2595 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kramp J. L. (2012). Senior cohousing: An optimal alternative for aging in place [Doctoral dissertation, Oklahoma State University]. https://media.proquest.com/media/pq/classic/doc/2921529671/fmt/ai/rep/NPDF?_s=5t9VCoKV5BEwMERzHUsNLWpPw4E% [Google Scholar]

- Lang F. R. (2003). Social motivation across the life span. In Lang F., Fingerman K. (Eds.), Growing together: Personal relationships across the lifespan (pp. 341–367). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lavery A. L. (2015). Aging in place: Perceptions of older adults on low income housing waitlists [Doctoral dissertation, University of Denver]. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/217243937.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Lee E. S. (1966). A theory of migration. Demography, 3(1), 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- LeFurgy J. B. (2017). Staying power: Aging in community and the village model [Doctoral dissertation, Virginia Tech]. https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/bitstream/handle/10919/77386/LeFurgy_JB_D_2017.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Google Scholar]

- Lehning A. J., Scharlach A. E., Davitt J. K. (2017). Variations on the Village model: An emerging typology of a consumer-driven community-based initiative for older adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 36(2), 234–246. 10.1177/0733464815584667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon M., Kang M., Kramp J. (2013). Case study of senior cohousing development in a rural community. Journal of Extension, 51(6), 6RIB3. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough K. E., Davitt J. K. (2011). It takes a village: Community practice, social work, and aging-in-place. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 54(5), 528–541. 10.1080/01634372.2011.581744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLaren C., Landsberg G., Schwartz H. (2007). History, accomplishments, issues and prospects of supportive service programs in naturally occurring retirement communities in New York State: Lessons learned. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 49(1–2), 127–144. 10.1300/J083v49n01_08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markle E. A., Rodgers R., Sanchez W., Ballou M. (2015). Social support in the cohousing model of community: A mixed-methods analysis. Community Development, 46(5), 616–631. [Google Scholar]

- Montepare J. M., Farah K. S. (2018). Talk of ages: Using intergenerational classroom modules to engage older and younger students across the curriculum. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 39(3), 385–394. 10.1080/02701960.2016.1269006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montepare J. M., Farah K. S., Doyle A., Dixon J. (2019). Becoming an Age-Friendly University (A.F.U.): Integrating a retirement community on campus. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 40(2), 179–193. 10.1080/02701960.2019.1586682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery V. (2020). Naturally occurring retirement community (NORCs). https://www.nysenate.gov/newsroom/articles/velmanette-montgomery/naturally-occuring-retirement-communities-norcs

- National Aging in Place Council. (2021). The cost of aging. https://www.ageinplace.org/Portals/0/Costs%20of%20Aging%20Handbook_1.pdf

- Ormond B. A., Black K. J., Tilly J., Thomas S. (2004). Supportive services programs in naturally occurring retirement communities. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/73266/NORCssp.pdf

- Oztop H., Akkurt S. S. (2016). An analysis of the factors that influence elders’ choice of location and housing. International Journal of Business Administration, 7(2), 79–85. 10.5430/ijba.v7n2p79 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pandya S. (2005). Racial and ethnic differences among older adults in long-term care service use. AARP Public Policy Institute. https://www.aarp.org/home-garden/livable-communities/info-2005/fs119_ltc.html [Google Scholar]

- Park S., Han Y., Kim B., Dunkle R. E. (2017). Aging in place of vulnerable older adults: Person–environment fit perspective. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 36(11), 1327–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker T. (2020). What is a naturally occurring retirement community? Retrieved December 11, 2020, from https://www.thebalance.com/what-is-a-naturally-occurring-retirement-community-4585208

- Pearson C. F., Quinn C. C., Loganathan S., Datta A. R., Mace B. B., Grabowski D. C. (2019). The forgotten middle: Many middle-income seniors will have insufficient resources for housing and health care. Health Affairs, 38(5), 10.1377/hlthaff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek M. K., O’Neill G. S. (2001). Networks in later life: An examination of race differences in social support networks. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 52(3), 207–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine P. P., Pine V. R. (2002). Naturally occurring retirement community-supportive service program: An example of devolution. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 14(3–4), 181–193. 10.1300/J031v14n03_10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retirement Living Information Center. (2020). College-linked retirement communities. https://www.retirementliving.com/college-linked-retirement-communities

- Scharlach A., Davitt J., Lehning A., Greenfield E., Graham C. (2014). Does the Village model help to foster age-friendly communities? Journal of Aging & Social Policy Special Issue on Age-Friendly Cities, 26(1–2), 181–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharlach A., Graham C., Lehning A. (2012). The “village” model: A consumer-driven approach for aging in place. The Gerontologist, 52(3), 418–427. 10.1093/geront/gnr083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharlach A. E. (2009). Frameworks for fostering aging-friendly community change. Generations, 33(2), 71–73. [Google Scholar]

- Senior List. (2021). Life on a college or university campus – an alternative retirement destination. https://www.theseniorlist.com/retirement/best/university/

- Smith E. K., Rozek E. K., Moore K. D. (2014). Creating SPOTs for successful aging: Strengthening the case for developing university-based retirement communities using social-physical place over time theory. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 28(1), 21–40. 10.1080/02763893.2013.85809 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stimson R. J., McCrea R. (2004). A push-pull framework for modeling the relocation of retirees to a retirement village: The Australian experience. Environment and Planning A, 36(8), 1451–1470. [Google Scholar]

- Stone R. (2013). What are the realistic options for aging in community? Generations, 37(4), 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- The Cohousing Association of the United States. (2017). Aging in cohousing. http://oldsite.cohousing.org/aging

- The Cohousing Association of the United States. (2020). What is elder or senior cohousing? https://www.cohousing.org/senior-cohousing/

- Thomas W., Blanchard J. (2009). Moving beyond place: Aging in community. Generations, 33(2), 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Tsao T. C. (2003). New models for future retirement: A study of college/university-linked retirement communities [Doctoral dissertation]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/305328947

- US Department of Housing Urban Development. (2013). Aging in place: Facilitating choice and independence. Evidence matters: Transforming knowledge into housing and community development policy. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/periodicals/em/fall13/highlight1.html [Google Scholar]

- Usher K. (2014). Local environment of Neighborhood NORC-SSP in a mid-sized U.S. City. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 28(2), 133–164. 10.1080/02763893.2014.899282 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Village to Village Network. (n.d.). Welcome to the village to village network. http://www.vtvnetwork.org

- Vladeck F. (2004). A good place to grow old: New York’s model for NORC supportive service programs. United Hospital Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Vladeck F., Altman A. (2015). The future of the NORC-supportive service program model. Public Policy & Aging Report, 25(1), 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl H. W., Iwarsson S., Oswald F. (2012). Aging well and the environment: Toward an integrative model and research agenda for the future. The Gerontologist, 52(3), 306–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl H. W., Lang F. R. (2003). Aging in context across the adult life course: Integrating physical and social environmental research perspectives. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 23(1), 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wardrip K. (2010). Fact sheet: Cohousing for older adults, Washington. https://www.aarp.org/home-garden/housing/info-03-2010/fs175.html

- Weeks L. E., Keefe J., Macdonald D. J. (2012). Factors predicting relocation among older adults. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 26(4), 355–371. [Google Scholar]

- Wickersham C. E. (2015). The pioneers of the village movement: An exploration of membership and satisfaction among Beacon Hill village members [Doctoral dissertation, Miami University]. https://etd.ohiolink.edu/apexprod/rws_etd/send_file/send?accession=miami1430305412&disposition=inline