Abstract

Aims: This scoping review explores key strategies of creating inclusive dementia-friendly communities that support people with dementia and their informal caregiver. Background: Social exclusion is commonly reported by people with dementia. Dementia-friendly community has emerged as an idea with potential to contribute to cultivating social inclusion. Methods: This scoping review follows the Joanna Briggs Institute scoping review methodology and took place between April and September 2020. The review included a three-step search strategy: (1) identifying keywords from CINAHL and AgeLine; (2) conducting a second search using all identified keywords and index terms across selected databases (CINAHL, AgeLine, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Web of Science, ProQuest, and Google); and (3) hand-searching the reference lists of all included articles and reports for additional studies. Results: Twenty-nine papers were included in the review. Content analysis identified strategies for creating dementia-friendly communities: (a) active involvement of people with dementia and caregivers (b) inclusive environmental design; (c) public education to reduce stigma and raise awareness; and (d) customized strategies informed by theory. Conclusion: This scoping review provides an overview of current evidence on strategies supporting dementia-friendly communities for social inclusion. Future efforts should apply implementation science theories to inform strategies for education, practice, policy and future research.

Keywords: dementia-friendly community, dementia-inclusive, social inclusion, scoping

Summary Statement of Implications for Practice

This study advances the understanding of the current landscape of efforts in developing dementia-friendly and inclusive communities

Planning and Implementing dementia-friendly and inclusive interventions require direct involvement of people with dementia

The findings highlight the need of using theories to inform strategy development and implementation

Introduction

The number of people with dementia is projected to reach 82 million by 2030 and 152 million by 2050 (World Health Organization [WHO], 2020). The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared dementia as a public health priority (WHO, 2020), and has called for global action to establish dementia-friendly initiatives. It is widely recognized that people with dementia and their informal caregivers face significant challenges that include stigma, social exclusion, and difficulty accessing local support resources. The recent COVID-19 pandemic has impacted people across the world, further challenging people with dementia and their informal caregivers. The concept of inclusive dementia-friendly communities has potential to promote social inclusion, change attitudes and behaviors, and support people with dementia to live in their community in meaningful ways, and examples are increasingly evident in countries around the world.

Dementia-Friendly and Inclusive Community, Social Inclusion

An inclusive dementia-friendly community can be defined as a place where people with dementia can be understood, respected, supported, and feel confident about being able to contribute to the community (Wu et al., 2019). Social inclusion refers to a dynamic process where people engage with, and are part of, their social networks in the community to maintain meaningful social relations (Wiersma & Denton, 2016). Social inclusion refers to characteristics of (a) social integration, (b) social support, and (c) access to resources (Newman et al., 2019). Raising awareness and education across all societal sectors helps to minimize stigma and enable social acceptance. Social connection and a sense of belonging are essential to well-being and quality of life. Purposeful connection, engaging in meaningful activities with other people, are important to a person with dementia and their families/care providers (Phinney et al., 2016). People with dementia can benefit from their local community network; social inclusion and social participation promote a sense of social citizenship, safety, and contribution (Wiersma, 2008). Considering that stigma and social exclusion are important issues for people with dementia living in the community, interventions that engage and include people with dementia in their community activities would seem vital to help support people with dementia and to assist them to remain living in their personal residential house or as long as possible.

The notion of dementia-friendly community has been drawn from the Age-Friendly Cities initiative of the World Health Organization (Ogilvie & Eggleton, 2016). Age-friendly communities involve bringing stakeholders together to help create inclusive environments in local communities in order to promote active and healthy aging (Hebert & Scales, 2019). Age-friendly communities contribute to good health and allow people to continue to participate fully in society (Webster, 2016). A similar guiding principle that dementia-friendly and age-friendly strategies both embody is empowering local stakeholders to collaborate and contribute to social inclusion. Public education, reduction of stigma, and removal of barriers in physical and social environments are common themes in both age-friendly and dementia-friendly initiatives (Phillipson et al., 2019).

With the development of inclusive dementia-friendly communities that have the potential to empower people with dementia, it is important to better understand what strategies make dementia-friendly and inclusive communities effective (Heward et al., 2017; Phillipson et al., 2016). There has been a shift toward using an asset-based approach to include the voices of people with dementia in building dementia-friendly communities (Rahman & Swaffer, 2018). “Nothing about us without us” is a phrase borrowed from the disability movement which has been frequently expressed by people with dementia in public campaigns (Wolfe, 2017). However, to date, robust knowledge about inclusive dementia-friendly communities remains limited. This scoping review aims to identify current evidence about strategies being used to create inclusive dementia-friendly communities (DFC) that support social inclusion.

Methods

Scoping reviews are useful to systematically map and synthesize the current state of evidence when a research topic is new and has not been fully established (Peters et al., 2015). The study question that guided this review was: What are the strategies used for developing inclusive dementia-friendly communities to improve social inclusion? This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for scoping reviews (Peters et al., 2015), which involved a three-step search approach: (1) identifying keywords from the initial broad search of two databases CINAHL and AgeLine; (2) conducting a second search using all identified keywords and index terms across seven databases (CINAHL, AgeLine, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Web of Science, ProQuest and Google); and (3) hand-searching the reference lists of all included articles and reports for additional studies. Our project team consisted of patient partners (n = 3) and family partners (n = 4), nurse researchers (n = 2), and a student in the faculty of medicine. The search strategy included identifying published journal articles and gray literature to cover the breadth of the available research literature reporting strategies used for developing inclusive dementia-friendly communities to improve social inclusion. The study took place between April and September 2020. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Studies that consider people living with dementia or their caregivers | Studies related to health conditions other than dementia. |

| Research addressing social inclusion and social participation | Research that did not include strategies to support social participation or social inclusion |

| Articles related to dementia friendly communities | Articles that do not specifically reference “dementia friendly communities” |

| Participants of all ages were considered | Research which focused on formal healthcare organizations, institutions or hospital care |

| Research addressing people with dementia in their personal residential house | |

| All study designs (qualitative and quantitative studies as well as informal community reports) | Non-English publications |

| All publications prior to July 2020 |

Participants

We included studies that focused on people with dementia of all ages living at their personal residential house in the community. Studies that focused on neighbors, local citizens, public, and private service providers, informal caregivers, and families of people with dementia in the community that promoted dementia-friendly community were also included.

Concept

This review considered any and all strategies that aimed to create positive impact to improve social inclusion and social participation of people with dementia, including public education activities to change attitudes and behaviors, and thus reduce stigma in community. For example, we included articles that reported on public awareness initiatives, education and training about dementia, and development of physical environment guidelines.

Context

We included studies conducted in community, with people residing at their personal residential house. Studies in targeted formal healthcare organizations and congregate living facilities such as hospitals, assisted living, and long-term care facilities, were not considered in this review.

Search Strategy

As recommended in JBI review guidelines, we applied a three-step search strategy. The first search of MEDLINE and CINAHL involved the following keywords: dementia or Alzheimer’s, (community or communities) OR (city or cities) OR (neighborhood or neighborhood) OR (environment or environments), friendly or capable or inclusive or inclusion. In the second step, we used all keywords and index terms identified from step one to search six databases: MEDLINE, CINAHL, Ageline, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and ProQuest for thesis and dissertation. Google was also searched using phrases, such as: “dementia-friendly” OR “dementia friendly” OR “dementia-inclusive” OR “dementia inclusive” OR “dementia-capable” OR “dementia capable.” Thirdly, the reference lists of all included articles and reports were screened for additional studies.

Study Selection and Reviewing Results

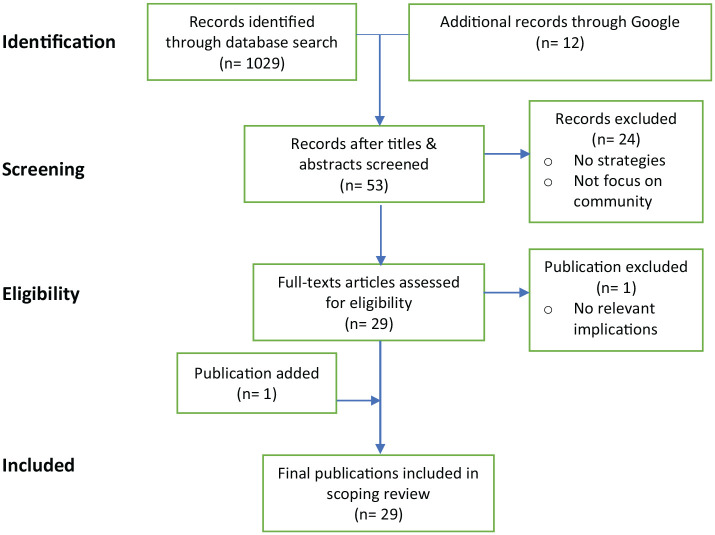

A bibliographic reference management tool, Mendeley, was used to ensure that all references and articles were systematically organized. All identified relevant articles were uploaded into Mendeley and duplicates were removed. The review process involved two levels of screening: a title and abstract review followed by a full-text review. In the first level of screening, three investigators independently screened the title and abstract for relevancy. In the second level of screening, the full text of relevant articles was examined for inclusion against the inclusion criteria: (a) focusing on people living with dementia, (b) home settings, (c) strategies for creating dementia-friendly communities. A data analysis software program, NVivo12, was used to conduct coding for full-text review of selected articles to identify themes that summarized the literature and answered the review question. We included studies published in English with no time limit, including a wide range of study designs from randomized controlled trials to descriptive studies, quantitative and qualitative designs. The database search initially yielded 1,029 publications and an additional 12 publications identified through Google search. After screening, 53 articles were identified. Of these, 24 records were excluded for not being relevant to the review question. After assessment for eligibility of the 29 articles in our team discussion with patient and family partners, one study was excluded. We also found one additional relevant study in the reference list and included it in the review. The final review included a total of 29 publications (n = 29). See Figure 1 for the PRISMA flow diagram (Peters et al., 2015) that describes the review process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Mapping

We mapped the selected articles in a summary table (see Table 2) by domains: author and country, setting, participants, strategies, and implications (lessons learned). In research meetings, the whole team including patient and family partners took part in analyzing the extracted data, sorted according to potential themes. We compared and discussed different interpretations to resolve conflicts.

Table 2.

Inclusive Dementia-Friendly Community Strategies.

| Author, Year | Setting | Participants | Type of article study design | Strategies | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buckner et al. (2019) | UK | 284 DFCs (Publicly available data and informal phone calls to staff of the DFCs) | Scoping review (Peer-reviewed article) | – Policy endorsement and recognition for DFCs are important. – Raising awareness is the most commonly cited DCF activity. – Involvement of people with dementia in organizational and operational aspects of DFCs. |

– Limited evidence to date of effected change, from DFCs. – Need for a systematic approach to evaluate DFCs. a. How they are organized b. How they are resourced c. How they demonstrate progress d. How they enable people living with dementia to live well. |

| Dean et al. (2015a) | UK (Bradford) | n = 100 (Community Members) | Evaluation report (Gray literature) | – Specific “Bradford approach” to creating DFCs which was unique to community needs and incorporated partners with lived experience. – Culturally sensitive services and inclusion of faith communities. – Support for informal caregivers. |

– People with dementia are affected by a number of factors, including a. Economic circumstances, b. Ethnicity c. Gender These factors must be considered in DFCs. – A number of challenges were identified for DFCs including: a. Funding for sustainability, b. Support for people with dementia and caregivers in public transport, services and resources. – Active involvement of people with dementia and informal caregivers has been identified as key to achieve DFC. |

| Dean et al. (2015b) | UK (York) | n = 38 (people with dementia, their informal caregivers and stakeholders) | Evaluation report (Gray literature) | – Focus on awareness. – Using general practitioners as the first point of contact after diagnosis. – Involving schools and young people, working at the service provider level to raise dementia awareness – Involving people with dementia in planning/initiating/ implementing/evaluating DFC undertakings. – Production of newsletters, local radio, printed media and art cartoons. |

– Programs were successful with integrating people with lived experience, incorporating intergenerational work and drawing on community/cultural assets. – The program found it more challenging to provide support to informal caregivers, and to address questions regarding the impact of labeling “dementia”. – Key recommendations included: a. People should be seen as people and not a disease. b. Utilize local assets (government or community). c. Physicians should be using a wellness approach to care. d. Integration of health and social care. e. Providing practical supports for informal caregivers. |

| Ebert et al. (2020) | US (Wisconsin) | n = 645 (Wisconsin Residents) | Quantitative study (Peer reviewed article) | – Strategies to address fear of dementia in general public: a. Providing biomedical knowledge b. Providing personhood based knowledge |

– Greater personhood-based knowledge and less personal-dementia-fear significantly predicted higher levels of social comfort, while biomedical knowledge did not. |

| Fleming et al. (2017) | Australia (Wollongong) | N/A | Evaluation study (Peer reviewed article) | – Development of a reliable tool to assess the support provided to people with dementia by public and commercial buildings (i.e., council offices, supermarkets, banks, and medical centers). | – This new tool aids the collection of reliable information on the strengths and weaknesses of public and commercial buildings. – This information is likely to be of use in the refurbishment of these buildings to improve their support of people with dementia as they use them in their daily life. |

| Gaber et al. (2019) | Sweden (Stockholm) | n = 69 (n = 35 people with dementia people n = 34 people with no known cognitive impairment) | Qualitative study (Peer reviewed article) | – Address factors that limit participation in public space by people with dementia. | – Participation with and relevance of everyday technologies were significantly lower for the dementia group. – To enable participation, occupational therapists need to be aware of challenges that technologies and places within public space present to people with dementia. |

| Gilmartin-Thomas et al. (2017) | UK (Greater London) | n = 16 people (participants represented groups working with and/or for older people and people with dementia) | Qualitative study (Peer reviewed article) | – Using the experience and perspective of people with lived experience to determine how pharmacies and pharmacists could be more dementia friendly. | – Participants confirmed the importance of pharmacists and pharmacies being aging- and dementia-friendly. – Mixed opinions on whether pharmacists/ pharmacies are currently dementia friendly. – Suggested strategies for improvement included: targeting communication, pharmacist leadership and shop layout. |

| Green and Lakey (2013) | UK (England, Wales and Northern Ireland) | n = 510 (People with dementia) | Report (Gray literature) | – People with lived experience are at the heart of DFCs. – Early diagnosis – easy to navigate environments – Respectful and responsive businesses and services – Community based solutions – Acknowledge potential of people with dementia – Challenge stigma |

– Only 42% of respondents felt that their community was dementia friendly. – Provided a definition of a dementia-friendly community. – Suggest 10 key areas of focus for communities to consider in working to become dementia-friendly. |

| Harris and Caporella (2014) | UK | n = 27 (13 = undergraduate college students, 13 people with dementia, 1 family member) | Qualitative study (Peer review article) | – Using an intergenerational choir to break down stereotypes and misunderstandings that young adults have about people with dementia. | – This intervention had a number of positive impacts including: changed attitudes, increased understanding about dementia and the lived experience. Reduced dementia stigma, development of meaningful social connections. |

| Hebert and Scales (2019) | International | N/A | Literature review (Peer reviewed article) | – Person-centered care principles – Strong interdisciplinary collaboration |

– Dementia-friendly initiatives broaden the lens from which dementia is viewed. – Future research recommendations: a. Theory-based studies to confirm dementia friendly initiative components and support rigorous evaluation. b. Determine the effect of dementia friendly initiatives on stakeholder-driven and community-based outcomes. |

| Heward et al. (2017) | UK (South of England) | n = 14 (People involved in development of DFCs) | Qualitative study (Peer reviewed article) | – Strategies for achieving stakeholder involvement in DFCs: a sustainable approach; spreading the word; and sharing of ideas. | – Challenges to achieving stakeholder involvement were identified as: establishing networks and including people representative of the local community; involving people affected by dementia; gaining commitment from organizations. – Future policies need to consider the unpredictability of stakeholder involvement. |

| Innovations in Dementia (2011) | UK | n = 84 (People with dementia) | Report (Gray literature) | – Things that made communities more dementia friendly: The physical environment, local facilities, support services, social networks, local groups. −1:1 informal supports |

– People with dementia said that they had stopped doing things in their community because of their dementia, and because they were wary of the attitude and reaction of others. – A social model of dementia has much to offer both in terms of campaigns to reduce stigma and raise awareness. – Dementia needs to be “normalized.” |

| Lin and Lewis (2015) | International | N/A | Conceptual analysis (Peer review article) | – National level policy – Impact of terminology “dementia friendly”, “dementia capable”, and “dementia positive” |

– a new vision statement for the U.S.’ national plan was proposed and recommendations provided for incorporating “dementia friendly”, “dementia capable” and “dementia positive” concepts in policy, research, and practice. |

| Lin (2017) | US | N/A | Literature review (Peer reviewed article) | – The concept of “dementia-friendly communities” encompasses the following: a. A means a place or culture of empowerment, aspiration, self-confidence b. Contribution, participation, meaningful activities c. Way-finding ability, sense of safety, accessibility, d. Maintenance of social networks, social acceptance, understanding of dementia |

– The diversity in definitions of “dementia-friendly communities” may reflect the constant innovation and progression in ways of thinking and of living with dementia. – Stakeholder involvement might lead to potential long-term sustainability issues of DFC. – Citizenship in the context of DFC, as well as how place and environmental designs influenced resilience. |

| Mitchell and Burton (2010) | UK | n = 45 (n = 20 People with dementia. n = 25 without dementia) | Qualitative study (Peer-review article) | – design considerations for DFCs (i.e., urban design and street furniture) | – Defined dementia-friendly neighborhoods as: welcoming, safe, easy and enjoyable for people with dementia and others to access, visit, use and find their around. – Identified six design principles for DFCs: familiarity, legibility, distinctiveness, accessibility, comfort, and safety. |

| Mitchell (2012) | UK | N/A | Report (Gray literature) | – Physical interventions in neighborhoods such as signage, city planning considerations, non slip footpaths. | – Articulated the role for people with dementia in achieving the quest for dementia-friendly communities – checklists on designing dementia- friendly communities. |

| Mitchell et al. (2004) | UK | n = 45 (n = 20 People with dementia. n = 25 without dementia) | Qualitative study (Peer-review article) | – Identification of the design factors that affect legibility for orientation and wayfinding among older people with dementia. | – Design features of the outdoor environment (from street layouts and building form to signage) influence the orientation and wayfinding abilities of people with dementia. |

| Murayama et al. (2019) | Japan (17 district areas in Machida City, Tokyo, Japan) | N = 1341 (Community-dwelling older adults aged ≥ 65 years) | Qualitative study (Peer-review article) | – Social networks (i.e., neighborly ties) – Social supports (emotional support and instrumental support) |

– People can continue to live in communities with high social capital, even if they are experiencing cognitive decline. |

| Page et al. (2015) | UK | n = 20 (People working in the tourism industry) | Qualitative study (Peer-review article) | – Dementia friendly tourism. | – Awareness and understanding of dementia is limited within tourism. – Cost concerns of businesses based on physical disabilities. – Experience with people with dementia improves attitude. – Recommend pilot site and partnership, opportunity to contribute to well-being of people with dementia, and inclusion in policy. |

| Phillipson et al. (2019) | Australia (Kiama) | n = 174 (Community members) | Report (Community based participatory action research (CBPAR)) | -Educational events were co-designed and co-facilitated by people with dementia and their care partners -Dementia Advisory Group and Alliance; an awareness campaign and education in community organizations. -Used face-to-face and website interventions to reach the community with their message. |

-Over the course of the project a number of positive outcomes were identified including improvement in attitude, reduced negative stereotypes. -The direct involvement of people with dementia as spokespeople and educators was an effective way to improve positive attitudes and reduce the negative stereotypes associated with living with dementia. |

| Plunkett and Chen (2016) | Canada | n = 51 (Clergy, lay leaders, parish nurses, members of the church health committee, admin staff) | Mixed methods study (Peer-review article) | -A church community was evaluated as a dementia friendly community -Dementia friendly strategies within churches were identified as: physical infrastructure, transportation, and education. |

-There is a need of inclusion of faith communities in dementia-friendly frameworks. -Church has potential to strengthen the health of a community to become more dementia inclusive. |

| Prior (2012) | UK | Not reported (individuals who were, or had been, involved in the creation of DFC) | Community report Included: literature review, semi-structured interviews (Gray literature) | -Prioritized lived experience and research in understanding how to establish an effective DFC. | -Outlines existing knowledge about the role that physical environments, both indoors and outdoors, can play in developing dementia- friendly communities and what physical environments are most appropriate for individuals living with dementia. |

| Rahman and Swaffer (2018) | UK | N/A | Editorial (Peer review article) | -Reframing of dementia-friendly communities, using an assets-based approach. | -Embracing assets-based approaches is critical to a renewed articulation of “dementia-friendly communities” toward communities that are inclusive and accessible (for all) and would also help to break down the barriers of the silos that the main stakeholders have found themselves in. - An assets-based approach recognizes the potential of people’s strengths and resilience. -Dementia-friendly communities should be accessible and inclusive for people with cognitive disabilities, not only friendly. |

| Shannon et al. (2019) | International | N/A | Scoping review (Peer-review article) | -Active participation of people who have dementia. -Environmental Assessment Tool. -Steering groups and use action plans. -Connections with local government. -Partnerships with academia in research. |

-Including people with dementia in projects is important for fostering social inclusion. -Collaborations and partnerships are vital for the development of DFCs. -Challenges for DFCs identified: a. Lack of resources b. Difficulty ensuring representation of marginalized groups. |

| Smith et al. (2016) | New Zealand Christchurch | n = 26 (People with dementia) | Qualitative study (peer review article) | -Gathered insights from people with dementia about what would make it possible for them to live better in Christchurch and to rebuild as a dementia-friendly city after 2011 earthquakes. | -Importance of being connected and engaged in society. -Accommodation from service providers. -Increased awareness of dementia among community at large. -Attributes of the physical environment that impact people with dementia (i.e., features that aid navigation of outdoor spaces safely). -Social connection and support groups were meaningful. |

| Wiersma and Denton (2016) | Canada (Rural Northern Ontario) | n = 71 (n = 37 Health service providers, n = 15 care partners, n = 2 people with dementia, n = 17 community partners) | Qualitative study (Peer-review) | -Social networks (community, family members, caregivers) in a rural community provided informal social support for people with dementia. | -Key components of a dementia friendly community are: a. Strong social networks (looking out for each other and people with dementia), b. Informal social support and strong commitment by community members, families, c. Health care providers helped people with dementia feel connected to the community who had a “culture of care”. |

| Wisconsin Department of Health (2015) | US (Wisconsin) | Not reported (Local and State partners, and agencies working on dementia projects) | Resource guide (Gray literature) | -Establishes toolkit for building DFCs. | -Guidelines on how to build a DFC. -Strategies for community members, for example, Business and recreation sectors. |

| Maki and Endo (2018) | Japan | n = 16 (n = 15Occupational therapists, n = 1 speech therapist) | Practice analysis (Peer reviewed article) | -Developed an education tool with support strategies for the public to use and posted on the website of the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology Japan. -Focused on four community scenes: financial institutions (banks/post offices), retail settings (supermarkets, convenience stores, parcel delivery service, pharmacy), public transportation (trains, buses, taxis), and government institutions (city/ward office, police box). |

-Occupational therapists can contribute to building dementia-positive communities. |

| Van Rijn et al. (2019) | Netherlands | n = 22 (Stakeholder, managers and project leaders) | Qualitative study (Peer reviewed article) | -DemenTalent- a program to engage people with dementia as volunteers, (under supervision) in meaningful societal activities, while taking into consideration both their talents and skills and promoting social health. | -The implementation of DemenTalent was feasible, the success is dependent on human resources, the collaboration network and the attitude in the region. -Barriers in implementation included: Taboo on dementia, rapid turnover of personnel, top-down decision. |

Summarizing Results

The extracted data were collectively evaluated, refined and collated into categories to develop the final themes. Themes were validated by patient and family partners. See Table 2 for the results charted to answer the scoping review study question: strategies and impact for inclusive dementia-friendly communities.

Ethical Consideration

Research ethics approval and consent to participate was not required for this scoping review because the methodology of the study only consisted of data from articles in public domains. As a team that included academic scholars and a trainee (student in medicine) working with people living with dementia, we engaged in team reflection in our regular meetings and used the guidance of the ethical framework “ASK ME” specifically developed for co-research with people with dementia (Mann & Hung, 2019). The voices of patient and family partners enriched researchers’ understanding of the topic. The researchers and medical resident also gained skills in the project for engaging patient and family partners through developing an awareness of the different styles of communication, exploring experiential views, and lived experience perspectives.

Results

Table 2 describes the characteristics of the 29 studies that met the eligibility criteria, including strategies and impact reported. Of the 29 publications, 14 were from the United Kingdom and three were identified as multi-country. The remainder were from Canada (2), the United States (2), Japan (2), Australia (2), New Zealand (1), and the Netherlands (1). From these publications, only three followed a quantitative study design, eight followed a qualitative study design, and the remaining publications were a mix of reports, review articles or gray literature (including documents from community and government organizations. Analysis across the 29 studies yielded the following themes: Active involvement, Inclusive environmental design, Public awareness education, and Customized approach adapting to local context.

Active Involvement

Active involvement in the running and organization of dementia-friendly communities by people living with dementia and their informal caregivers was identified as a valued strategy in the development of dementia-friendly communities (Buckner et al., 2019; Dean et al., 2015a, 2015b; Ebert et al., 2020; Heward et al., 2017; Phillipson et al., 2019, p. 30). Knowledge shared by people with lived experience was identified as important within the process of designing inclusive dementia-friendly communities (DFC) interventions and was also seen as a means to instill a sense of value and autonomy for people living with dementia (Buckner et al., 2019; Dean et al., 2015b; Heward et al., 2017). Across the literature reviewed, examples of active participation included: participation in designed activities, engagement with community resources, involvement in development of educational resources/programming, delivery of educational materials, involvement on an organizational level, and promotion/advertisement of DFCs (Buckner et al., 2019; Dean et al., 2015b; Ebert et al., 2020; Heward et al., 2017; Phillipson et al., 2019). Personhood-based knowledge was specifically highlighted as beneficial in results when educating the public about dementia (Ebert et al., 2020; Phillipson et al., 2019). Involvement by people with dementia and their informal caregivers was also identified as important for sustainability of projects/organizations, as investment from community organizations was not always as consistent (Heward et al., 2017).

Active involvement was identified as a key to the success of DFCs; however, it was also recognized that within many existing DFCs, the organization had not been designed with active involvement from people with lived experience (Buckner et al., 2019; Van Rijn et al., 2019). In particular, a lack of first-person knowledge was felt to impact participation in DFCs (Dean et al., 2015b). There were a number of barriers to active involvement which were identified across the literature. Dean et al. (2015a, 2015b) conducted evaluation reports about two dementia friendly programs in the UK, primarily using qualitative interviews. Within these reports, themes of physical barriers; and socioeconomic status, gender, and ethnicity all had impacts on the individual’s active engagement in the dementia friendly communities. For example, individuals of certain ethnicities were found less likely to be referred to the program by health care providers. It was also recognized that gender and cultural experience had an impact on the way’s individuals experienced available programing, and as such influenced participation. In a 2019 scoping review, informal caregivers speaking on behalf of people with dementia and fear/concern of being negatively labeled if speaking about dementia were identified as themes which impacted involvement and prevented lived experience voices from being included in development of dementia friendly programs (Shannon et al., 2019). Increased involvement by people with lived experience was felt to improve the quality and success of DFCs.

Inclusive Environmental Design

Environmental design that considers the unique needs of people with dementia and their informal caregivers can meaningfully contribute to DFCs (Dean et al., 2015b; Fleming et al., 2017; Gaber et al., 2019; Gilmartin-Thomas et al., 2017; Prior, 2012; Shannon et al., 2019; Wiersma, 2008). A review of 284 DFC programs in England highlighted that “enabling people living with dementia to access mainstream services is where DFCs should start” (Buckner et al., 2019). It was recognized within this review that many dementia friendly communities were formed specifically due to the need for environmental adaptations to support people with dementia using community services such as churches and shops. Similarly, a practice analysis conducted with occupational and speech therapists identified that many people with dementia were significantly limited in function and engagement in community due to environmental considerations, such as street design impacting wayfinding (Maki & Endo, 2018). Environmental considerations encompassed social interactions, physical design elements, and technological considerations. Supportive staff/community members and general friendliness were identified as essential strategies to help people with dementia engage in their communities (Smith et al., 2016; Wiersma, 2008). Placement and legibility of signage, and general consideration for wayfinding needs were also highlighted as common strategies employed to support people living with dementia (Maki & Endo, 2018; Mitchell, 2012; Mitchell et al., 2004; Mitchell & Burton, 2010; Shannon et al., 2019). Accessibility was another essential consideration related to environmental design, with particular consideration for transportation and access to public transit (Fleming et al., 2017; Mitchell, 2012). In a qualitative study conducted by Gilmartin-Thomas et al. (2017) both formal and informal caregivers highlighted pharmacies as an essential location, frequently visited by people with dementia. As pharmacies were felt to be an important touchstone for people with dementia the participants felt this would be a valuable location to employ dementia-friendly strategies (Gilmartin-Thomas et al., 2017). Technology was also identified as a potential barrier for people with dementia, and the importance of low technology spaces/programs was felt to be beneficial in supporting DFCs (Gaber et al., 2019).

Public Awareness Education

Stigma and lack of public awareness were identified as significant concerns for people living with dementia. Public awareness and education were identified as an essential strategy to target stigma within the general community (Buckner et al., 2019; Harris & Caporella, 2014; Hebert & Scales, 2019). Within studies evaluating the activities of existing DFCs, education and raising awareness were identified as the most common activities performed by DFCs (Buckner et al., 2019). Specific awareness-raising strategies have included educational campaigns including pamphlets, social media presence, and memory cafes (Buckner et al., 2019; Hebert & Scales, 2019; Maki & Endo, 2018). Promotion of intergenerational relationships was also identified as a public awareness tool. A qualitative study looking at the use of intergenerational choirs found that young adults involvement in this program resulted in a positive change in attitude and reduced stigma toward dementia (Harris & Caporella, 2014). In studies that explored the delivery of educational materials, people with lived experience were seen as valuable contributors (Ebert et al., 2020; Phillipson et al., 2019).

Customized Approach Adapting to Local Context

People living with dementia belong to many different communities, with variable geographic and cultural contexts. Within this scoping review, authors recognized that DFCs should be designed with the specific needs of the local community in mind (Dean et al., 2015b; Smith et al., 2016; Van Rijn et al., 2019; Wiersma, 2008; Wiersma & Denton, 2016). There are many factors which may influence the experience of people living with dementia, including socioeconomic status, ethnicity, gender, and culture (Dean et al., 2015b). Development of DFC interventions with support from people with lived experience and varied backgrounds was highlighted as a useful strategy to address this need (Dean et al., 2015b). The geography of a DFC may also influence individual community needs; for example, a rural DFC might have different considerations compared to an urban DFC (Wiersma & Denton, 2016). Local partnerships with other community organizations were felt to be another essential strategy for the creation of sustainable DFC structures (Heward et al., 2017). Failure to value a customized approach and reliance on top-down decision making was identified as a barrier to the development of successful DFCs (Van Rijn et al., 2019).

Discussion

The goal of this study was to explore key strategies for creating inclusive dementia-friendly communities that support people with dementia and their informal caregivers. Our findings are congruent with the four dementia-friendly principles promoted by the Alzheimer Disease International (ADI, 2016): people (involvement of people living with dementia), communities (supportive physical and social environments), organization (dementia-friendly businesses and organizations), and partnerships (relationships with local governments, service agencies). Although each place (neighborhoods, cities, and countries) may have different strengths and needs with regard to their local culture, there are similar key strategies to promote social inclusion.

The direct involvement of people with dementia is a growing demand from advocacy organizations such as ADI and Alzheimer Societies across the world. More attention should be paid to structural support to enable meaningful involvement of people with dementia. When considering the promotion and development of dementia friendly communities, people with dementia should be invited into the development of strategies and technologies from early phases through to dissemination to ensure these approaches are relevant, useful, and usable.

Within the literature included in the current study, there was limited discussion around the impact of gender, ethnicity, culture, and socioeconomic status, on DFCs and the experiences of people with dementia and their caregivers. Of the studies which addressed these themes it was recognized that each had a significant impact on both individual experience and systems level functioning for DFCs. The authors of this paper recognize that these are essential factors which require careful consideration and thought as they pertain to the development and running of DFCs.

One important gap in the current efforts for inclusive dementia-friendly communities is the involvement of young informal caregivers to include their perspectives of needs and experiences. The current literature has drawn attention to educating young children and young adults and involving them in intergenerational activities; however, there were no studies specific to dementia friendly communities that highlighted voices of young informal caregivers. Although intergenerational contacts and education are crucial for creating future inclusive dementia-friendly generations, further knowledge is required to gain a better understanding of young informal caregivers’ perspectives. Young informal caregivers of parents with young-onset dementia can be children at a very young age. The first author in her clinical work has met with young children in schools, even including some under 10 years old. These children have very different needs and creative strengths compared to adults and older caregivers. In the study by Hall and Sikes (2017), young informal caregivers reported that they provide substantial levels of care, which affected their health, school education, and childhood social life.

Strengths and Limitations

This scoping review offers three contributions. First, we provide a robust synthesis of updated evidence to report 29 articles from 2004 to 2019, thus building upon a previous review (Shannon et al., 2019) of eight papers from 2011 to 2016. Second, we mapped accessible literature, including gray literature to provide a comprehensive overview of evidence to inform education, practice, policy, and research. Third, by including patient and family partners in conducting the scoping review, we ensure the relevance and quality of the study, including transparency and accountability.

Here we must also acknowledge some of the study limitations. We focus on strategies for social inclusion in this study. “Inclusive dementia-friendly” is still a new term in development and as such, it has not been consistently defined. Dementia friendliness may mean different things to different people. The results of this scoping review did not highlight a complete breadth of current dementia care approaches. For example, no studies in the review addressed the role of animal companions despite this being an area discussed in dementia literature. Also, this scoping review did not include non-English literature. It is possible that we missed important dementia-friendly interventions implemented in non-English speaking countries. Future research should investigate efforts invested in non-English speaking and developing countries.

Future Areas of Study

Future research should investigate how different theories can be applied to guide implementation and evaluation of outcomes. International research to compare findings across inclusive dementia-friendly communities will allow sharing of useful lessons for collective and individual progress. Implementation science theories can inform strategies in developing inclusive dementia-friendly community projects. For example, future projects should consider applying an established framework such as the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to optimize process and outcome evaluations (Damschroder et al., 2009).

This review identified a need for additional voices and perspectives regarding dementia friendly communities to be included in the academic literature. In particular we identified the need for studies regarding young-informal-caregivers, individuals from varied backgrounds (with regards to sex, ethnicity, culture, and socioeconomic status) and the perspective of individuals with more variability in severity of dementia symptoms. It was also recognized that additional literature identifying specific facilitators and barriers for involvement in research for inclusive dementia friendly communities by people with dementia would be beneficial.

Lastly, now more than ever, as we live through the COVID-19 pandemic, there is an even greater need for innovative approaches to promote inclusive dementia-friendly communities for social inclusion. With the rise of technologies and virtual platforms, it may be possible to explore how touchscreen phones and tablet devices may be used to support people with dementia in active engagement in DFCs, promote social inclusion, and expand public education.

Conclusion

This scoping review identified four key strategies of creating inclusive dementia-friendly communities that support people with dementia and their informal caregivers: (a) active involvement of people with dementia and their informal caregivers; (b) inclusive environmental design; (c) public education to reduce stigma and raise awareness; and (d) customized strategies informed by dementia-friendly and inclusive theories. This study has yielded insights into the key DFC strategies that provide learning opportunities for global communities with evidence to take into account for their inclusive dementia-friendly agenda. Theories in implementation science should be applied to guide research and projects to optimize the process and outcome evaluations.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the funding support by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research #18 773.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project is funded by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research #18 773.

ORCID iDs: Allison Hudson  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4568-371X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4568-371X

References

- Alzheimer Disease International. (2016). Dementia-friendly communities: Key principles. https://www.alzint.org/u/dfc-principles.pdf

- Buckner S., Darlington N., Woodward M., Buswell M., Mathie E., Arthur A., Lafortune L., Killett A., Mayrhofer A., Thurman J., Goodman C. (2019). Dementia friendly communities in England: A scoping study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 34(8), 1235–1243. 10.1002/gps.5123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder L. J., Aron D. C., Keith R. E., Kirsh S. R., Alexander J. A., Lowery J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(50), 40–55. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean J., Silversides K., Crampton J., Wrigley J. (2015. a). Evaluation of the bradford dementia friendly communities programme. jrf.org.uk

- Dean J., Silversides K., Crampton J., Wrigley J. (2015. b). Evaluation of the York dementia friendly communities programme. jrf.org.uk

- Ebert A. R., Kulibert D., McFadden S. H. (2020). Effects of dementia knowledge and dementia fear on comfort with people having dementia: Implications for dementia-friendly communities. Dementia, 19(8), 2542–2554. 10.1177/1471301219827708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming R., Bennett K., Preece T., Phillipson L. (2017). The development and testing of the dementia friendly communities environment assessment tool (DFC EAT). International Psychogeriatrics, 29(2), 303–311. 10.1017/S1041610216001678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaber S. N., Nygård L., Brorsson A., Kottorp A., Malinowsky C. (2019). Everyday technologies and public space participation among people with and without dementia. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 86(5), 400–411. 10.1177/0008417419837764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmartin-Thomas J. F.-M., Orlu M., Alsaeed D., Donovan B. (2017). Using public engagement and consultation to inform the development of ageing- and dementia-friendly pharmacies – Innovative practice. Dementia, 19(4), 1237–1243. 10.1177/1471301217725896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green G., Lakey L. (2013). Building dementia-friendly communities: A priority for everyone. Alzheimer’s Society. https://actonalz.org/sites/default/files/documents/Dementia_friendly_communities_full_report.pdf

- Hall M., Sikes P. (2017). “It would be easier if she’d died”: Young people with parents with dementia articulating inadmissible stories. Qualitative Health Research, 27(8), 1203–1214. 10.1177/1049732317697079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris P. B., Caporella C. A. (2014). An intergenerational choir formed to lessen alzheimer’s disease stigma in college students and decrease the social isolation of people with alzheimer’s disease and their family members: A pilot study. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 29(3), 270–281. 10.1177/1533317513517044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert C. A., Scales K. (2019). Dementia friendly initiatives: A state of the science review. Dementia, 18(5), 1858–1895. 10.1177/1471301217731433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heward M., Innes P. A., Cutler C., Hambidge S., Innes A., Cutler C., Hambidge S. (2017). Dementia-friendly communities: Challenges and strategies for achieving stakeholder involvement. Health and Social Care in the Community, 25(3), 858–867. 10.1111/hsc.12371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innovations in Dementia. (2011). Dementia capable communities: The views of people with dementia and their supporters Executive summary and recommendations. www.Innovationsindementia.Org.Uk, February, 1–7. https://www.housinglin.org.uk/_assets/Resources/Housing/OtherOrganisation/DementiaCapableCommunities_fullreportFeb2011.pdf

- Lin S. Y. (2017). “Dementia-friendly communities” and being dementia friendly in healthcare settings. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 30(2), 145–150. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S. Y., Lewis F. M. (2015). Dementia friendly, dementia capable, and dementia positive: Concepts to prepare for the future. Gerontologist, 55(2), 237–244. 10.1093/geront/gnu122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki Y., Endo H. (2018). The contribution of occupational therapy to building a dementia-positive community statement of context Background. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 81(10), 566–570. 10.1177/0308022618774508 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mann J., Hung L. (2019). Co-research with people living with dementia for change. Action Research, 17(4), 573–590. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell L. (2012). Breaking new ground: The quest for dementia friendly communities. Housing Learning and Improvement Network, June. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell L., Burton E. (2010). Designing dementia-friendly neighbourhoods: Helping people with dementia to get out and about. Journal of Integrated Care, 18(6), 11–18. 10.5042/jic.2010.0647 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell L., Burton E., Raman S. (2004). Dementia-friendly cities: Designing intelligible neighbourhoods for life. Journal of Urban Design, 9(1), 89–101. 10.1080/1357480042000187721 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murayama H., Ura C., Miyamae F., Sakuma N., Sugiyama M., Inagaki H., Okamura T., Awata S. (2019). Ecological relationship between social capital and cognitive decline in Japan: A preliminary study for dementia-friendly communities. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 19(9), 950–955. 10.1111/ggi.13736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman K., Wang A. H., Ze A., Wang Y., Hanna D. (2019). The role of internet-based digital tools in reducing social isolation and addressing support needs among informal caregivers: A scoping review. BMC Public Health, 19(1495), 1–12. 10.1186/s12889-019-7837-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvie K., Eggleton A. (2016). Standing senate committee on social affairs, science and technology. Dementia in Canada: A national strategy for Dementia-friendly Communities. www.senate-senat.ca

- Page S. J., Innes A., Cutler C. (2015). Developing dementia-friendly tourism destinations: An exploratory analysis. Journal of Travel Research, 54(4), 467–481. 10.1177/0047287514522881 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters M., Godfrey C., Khalil H., McInerney P., Parker D., Soares C. (2015). The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ manual: 2015 edition/supplement. Joanna Briggs Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson L., Hall D., Cridland E. (2016). Dementia friendly kiama pilot project evaluation. Kiama Municipal Council. [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson L., Hall D., Cridland E., Fleming R., Brennan-Horley C., Guggisberg N., Frost D., Hasan H. (2019). Involvement of people with dementia in raising awareness and changing attitudes in a dementia friendly community pilot project. Dementia, 18(7–8), 2679–2694. 10.1177/1471301218754455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney A., Kelson E., Baumbusch J., OConnor D., Purves B. (2016). Walking in the neighbourhood: Performing social citizenship in dementia. Dementia, 15(3), 381–394. 10.1177/1471301216638180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plunkett R., Chen P. (2016). Supporting healthy dementia culture: An exploratory study of the church. Journal of Religion and Health, 55(6), 1917–1928. 10.1007/s10943-015-0165-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior P. (2012). Knowing the foundations of dementia friendly communities for the North East. September, 1–82. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman S., Swaffer K. (2018). Assets-based approaches and dementia-friendly communities. Dementia, 17(2), 131–137. 10.1177/1471301217751533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K., Bail K., Neville S. (2019). Dementia - friendly community initiatives: An integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(11–12), 2035–2045. 10.1111/jocn.14746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K., Gee S., Sharrock T., Croucher M. (2016). Developing a dementia-friendly Christchurch: Perspectives of people with dementia. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 35(3), 188–192. 10.1111/ajag.12287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rijn A., Meiland F., Droës R. M. (2019). Linking DemenTalent to Meeting Centers for people with dementia and their caregivers: A process analysis into facilitators and barriers in 12 Dutch Meeting Centers. International Psychogeriatrics, 2019, 1433–1445. 10.1017/S1041610219001108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster D. (2016). Dementia-Friendly Communities Ontario: A Multi-Sector Collaboration to Improve Quality of Life for People Living With Dementia and Care Partners Ontario. The Alzheimer Society of Ontario. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2020). Dementia. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia

- Wiersma E. C. (2008). The experiences of place: Veterans with dementia making meaning of their environments. Health & Place, 14(4), 779–794. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiersma E., Denton A. (2016). From social network to safety net: Dementia-friendly communities in rural northern Ontario. Dementia, 15(1), 51–68. 10.1177/1471301213516118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisconsin Department of Health. (2015). A toolkit for building dementia-friendly communities. https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/publications/p01000.pdf

- Wolfe A. (2017). Dementia friendly community: Municipal toolkit. http://www.dementiafriendlysaskatchewan.ca/assets/dfc_municipal_toolkit_web.pdf

- Wu S., Huang H., Chiu Y., Tang L., Yang P., Hsu J., Liu C., Wang W., Shyu Y. L. (2019). Dementia-friendly community indicators from the perspectives of people living with dementia and dementia-family caregivers. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(11), 2878–2889. 10.1111/jan.14123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]