Abstract

We report the case of a 50-year-old Tibetan man who presented to an outpatient urology clinic after abdominal ultrasound for poorly defined abdominal pain demonstrated horseshoe kidney (HK) with a right moiety ~3.7 cm mass further characterised using contrast-enhanced CT scan (CECT). This dedicated imaging confirmed HK with a heterogeneously enhancing right upper pole 3.1 cm×3.7 cm×2.7 cm mass. Due to suspicion for aberrant vasculature on CECT, renovascular angiography was performed, which revealed recruitment of a right paravertebral vessel alongside two right renal moiety arteries and multiple right renal moiety veins. Based on vascular complexity and the surgical exposure required for arterial clamping, open transperitoneal right partial nephrectomy was preferred to minimally invasive techniques. Postoperative course was complicated by ileus, which resolved with standard management. Pathologic analysis revealed complete resection of a 5.0 cm Fuhrman grade II clear cell renal cell carcinoma.

Keywords: urology, oncology, cancer intervention, urological cancer

Background

Renal cancer is the seventh most common malignancy and is commonly diagnosed incidentally on imaging performed for unrelated indications.1 Risk factors for renal cancer include obesity, tobacco use and certain genetic syndromes. Horseshoe kidney (HK) is a well-known, typically asymptomatic, renal fusion anomaly with an estimated incidence of 74 000 yearly.2 Risk factors for HK include male sex and certain genetic syndromes, notably trisomy 21 and Turner syndrome.3 Consequently, there is substantial potential for coincidence of these conditions and several literature reports explore treatment modalities for this unusual situation.4–7

Current low grade evidence supports the oncologic equivalence and renal function preservation with using partial nephrectomy (PN) for managing renal tumours up to stage 2.8 Stage T2 tumours are defined as tumour greater than 7 cm and limited to the kidney.8 Due to the rarity of renal cancer in HK, treatment algorithms are not well defined for managing these tumours. Despite this, PN is preferable to radical nephrectomy where feasible because the latter would leave these patients anephric. In this setting, many urologists prefer minimally invasive robotic-assisted PN (RAPN). However, this approach may not be feasible in the setting of significant anatomic complexity, especially vascular aberrancy, and open transperitoneal PN may achieve optimal outcomes for these complex patients.

Case presentation

We report the case of a 50-year-old unemployed male Tibetan immigrant referred to a community urology office 2 years after evaluation at a local emergency department. During his initial emergency room evaluation, it was discovered that the patient was experiencing moderate episodic diffuse abdominal pain. He denied: a clear onset, inciting factors, fever, stool changes, gross haematuria, dysuria or other complaints and noted these episodes self-resolved after several hours. Based on that presentation, he was further evaluated using abdominal ultrasonography which incidentally revealed HK with a possible focal lesion but no clear radiologic correlation for his symptoms. Further history taking revealed the patient to be a former 7 pack-year smoker who denied: prior knowledge of renal disease, prior renal evaluation or a family history of kidney cancer or other malignancy. During this initial evaluation his symptoms resolved, and he was discharged pending contrast-enhanced abdominal CT scan and outpatient urology follow-up.

Two years later, the patient was counselled on the importance of completing radiologic and urologic follow-up, despite resolution of his initial complaint, and he agreed to undergo contrast-enhanced abdominal CT scan which revealed an approximately 3.5 cm lesion suspicious for renal cell carcinoma in the posterior right moiety of an HK. Using a Tibetan language interpreter, the patient was counselled on the likely significance of this finding and possible treatment options. After undergoing further dedicated imaging including renal artery angiography and extensive counselling, the patient elected to undergo definitive surgical management and was treated with an open transperitoneal PN.

Investigations

Abdominal ultrasound is a relatively inexpensive and rapid modality for evaluating a variety of abdominal complaints with the added benefit of avoiding radiation exposure. Unfortunately, it is somewhat operator dependent and is less accurate than other modalities for measuring distances and the size of various lesions. We present below a selected image from the patient’s initial abdominal ultrasound which demonstrates a focal lesion in an HK. Notably, ultrasound is not the preferred modality for categorising most renal lesions. Thus, renal lesions that are not benign cysts should be further evaluated for malignant potential using dedicated imaging such as contrast-enhanced CT scan (CECT) or MRI (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Initial abdominal ultrasound demonstrating a 3.6 cm focal lesion within horseshoe kidney (arrow).

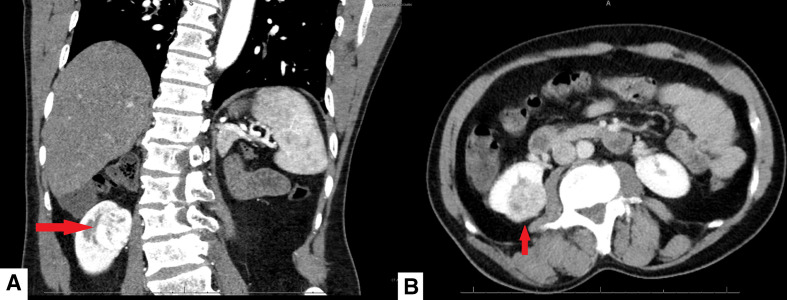

The selected abdominal CECT images below demonstrate the same lesion noted above, after a 2-year interval. A heterogeneously enhancing mass in the upper pole of the right kidney measuring 2.7×3.7 cm with characteristics concerning for renal cell cancer is demonstrated. The measurement of this lesion is more likely to be accurate using CT scan instead of ultrasonography although it is unlikely significant interval growth occurred between acquisition of these images as renal cell carcinomas tend to grow between 2 and 3 mm per year (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Contrast-enhanced CT scan showing a heterogeneously enhancing mass in the right upper pole moiety measuring 2.7×3.7 cm (arrow) in coronal (A) and axial (B) projections.

The CECT images presented above revealed significant vascular complexity and raised the question of additional vascular aberrancy. While HK is often notable for its complex vasculature, renal neoplasms are also commonly noted to produce unusual vascularity. In this setting, it was felt that definitive evaluation of the vasculature was critical to preoperative planning and the decision was made to acquire a renal angiogram. In particular, the aberrant right paravertebral artery noted below was felt to preclude a retroperitoneal approach. When considering this dedicated imaging, it was felt that exposure of the great vessels and aorta was necessary for definitive vascular control. Therefore, open transperitoneal PN was determined to be the safest option for definitive surgical management (figures 3–5).

Figure 3.

Renal angiogram reconstruction showing an aberrant right paravertebral artery (arrow) and other vascular complexity in a horseshoe kidney (viewed anterior to posterior).

Figure 4.

Coronal CT image showing the horseshoe kidney, which demonstrates superior and inferior vasculature.

Figure 5.

Cross-sectional CT image showing the right renal moiety mass and five right arterial branches. Four of these arteries supply the medial aspect, while one additional artery supplies the posterior aspect of the right moiety.

Treatment

The patient underwent open transperitoneal PN of his right renal moiety lesion. Pathologic analysis revealed resection of a 5.0 cm Fuhrman grade II renal cell carcinoma with negative resection margins. Postoperative course was complicated by ileus, which resolved with standard management techniques.

Outcome and follow-up

Postoperative visits in the subsequent year have been uneventful and the patient has resumed normal activities without restriction. Six-month and one-year postoperative CT scan showed no evidence of recurrence and the patient is continuing his follow-up care without any issues.

Discussion

Due to demonstrated oncologic equivalence and increased appreciation of the correlation between renal function and overall mortality, PN has become the preferred modality for surgical excision of renal lesions whenever technically feasible. This is particularly true for patients with solitary kidney who would otherwise become dialysis dependent. This procedure has been performed using transperitoneal or retroperitoneal approaches and open or minimally invasive techniques. In recent years, transperitoneal RAPN has become a preferred modality for this procedure and has even been studied in the setting of complex renal anatomy.9 Even in this complex setting, some authors report outcome improvements for minimally invasive techniques like RAPN versus open PN (OPN), mainly limited to reductions in length of stay, estimated intraoperative blood loss and transfusion rates.9 Despite this finding for patients with complex renal anatomy, there are no large studies of RAPN versus OPN in patients with HK and any such study would likely be undermined by the heterogeneity of this special population.

Despite the potential perioperative outcome improvement afforded by RAPN, it is imperative to perform thorough preoperative evaluation and select the most appropriate PN modality for each patient based on the findings of their evaluation. The authors felt that OPN in this case afforded superior visualisation of the aorta and great vessels. Access to these vessels was essential to control intraoperative haemorrhage. A retroperitoneal robotic approach was also considered in this patient. However, with several aberrant vessels in the vicinity and an atypical hilar dissection, the authors felt that this approach, while tempting to consider, was not the safest for this patient.

It is therefore the author’s opinion that the choice to perform RAPN or OPN for renal tumours in HK should be made after assessing vascular complexity, tumour size and related imaging findings. This case-by-case decision-making is evident in the limited HK literature where some authors report successful minimally invasive PN, while others prefer OPN in this complex setting.4–7 One of the few literature reviews of RAPN in HK offers the advice that the procedure should only be attempted by expert robotic surgeons after thorough preoperative imaging, especially vascular reconstruction CT imaging, reveals favourable anatomy.10

Learning points.

We advise robotic-assisted partial nephrectomy (PN) in a horseshoe kidney only be pursued after thorough preoperative imaging showing favourable anatomy and that urologists maintain a low threshold to perform open PN in complex cases.

Renovascular angiography is a powerful technique for evaluation of complex vasculature and should be pursued when feasible.

Open surgical techniques may be preferred to minimally invasive techniques in cases with unusual anatomical complexity or unfavourable vasculature.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our gratitude to the outpatient clinical staff and hospital-based clinical staff without whom this work would have been impossible. In addition, we are deeply grateful to our patient for making the decision to contribute his experiences to the medical literature in service to future patients.

Footnotes

Twitter: @EvanSpe72773131

Contributors: ES - assistance with surgery, background research, chart review, manuscript writing, submission. AR - background research chart review, research, manuscript writing, submission. JB - Oversaw project, Assistance with surgery, chart review, manuscript writing. MF - Oversaw project, Assistance with surgery, chart review, manuscript writing.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin 2020;70:7–30. 10.3322/caac.21590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weizer AZ, Silverstein AD, Auge BK, et al. Determining the incidence of horseshoe kidney from radiographic data at a single institution. J Urol 2003;170:1722–6. 10.1097/01.ju.0000092537.96414.4a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bondy CA, Turner Syndrome Study Group . Care of girls and women with Turner syndrome: a guideline of the Turner syndrome Study Group. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:10–25. 10.1210/jc.2006-1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nikoleishvili D, Koberidze G. Retroperitoneoscopic partial nephrectomy for a horseshoe kidney tumor. Urol Case Rep 2017;13:31–3. 10.1016/j.eucr.2017.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamamichi G, Nakata W, Tsujimura G, et al. Renal cell carcinoma in a horseshoe kidney treated with robot-assisted partial nephrectomy. Urol Case Rep 2019;25:100902. 10.1016/j.eucr.2019.100902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grygorenko V, Zakordonets V, Danylets R, et al. Partial nephrectomy of horseshoe kidney with renal cell carcinoma localized in the isthmus and the lower poles of both parts: a case report. European Urology Supplements 2017;16:e2175–6. 10.1016/S1569-9056(17)31332-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kongnyuy M, Martinez D, Park A, et al. A rare case of a renal cell carcinoma confined to the isthmus of a horseshoe kidney. Case Rep Urol 2015;2015:1–3. 10.1155/2015/126409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Kidney Cancer (Version 1.2021). Available: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/kidney.pdf [Accessed 13 Sep 2020].

- 9.Garisto J, Bertolo R, Dagenais J, et al. Robotic versus open partial nephrectomy for highly complex renal masses: comparison of perioperative, functional, and oncological outcomes. Urol Oncol 2018;36:471.e1–471.e9. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2018.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raison N, Doeuk N, Malthouse T, et al. Challenging situations in partial nephrectomy. Int J Surg 2016;36:568–73. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.05.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]