Abstract

Intersectoral action (ISA) is considered pivotal for achieving health and societal goals but remains difficult to achieve as it requires complex efforts, resources and coordinated responses from multiple sectors and organizations. While ISA in health is often desired, its potential can be better informed by the advanced theory-building and empirical application in real-world contexts from political science, public administration and environmental sciences. Considering the importance and the associated challenges in achieving ISA, we have conducted a meta-narrative review, in the research domains of political science, public administration, environmental and health. The review aims to identify theory, theoretical concepts and empirical applications of ISA in these identified research traditions and draw learning for health. Using the multidisciplinary database of SCOPUS from 1996 to 2017, 5535 records were identified, 155 full-text articles were reviewed and 57 papers met our final inclusion criteria. In our findings, we trace the theoretical roots of ISA across all research domains, describing the main focus and motivation to pursue collaborative work. The literature synthesis is organized around the following: implementation instruments, formal mechanisms and informal networks, enabling institutional environments involving the interplay of hardware (i.e. resources, management systems, structures) and software (more specifically the realms of ideas, values, power); and the important role of leaders who can work across boundaries in promoting ISA, political mobilization and the essential role of hybrid accountability mechanisms. Overall, our review reaffirms affirms that ISA has both technical and political dimensions. In addition to technical concerns for strengthening capacities and providing support instruments and mechanisms, future research must carefully consider power and inter-organizational dynamics in order to develop a more fulsome understanding and improve the implementation of intersectoral initiatives, as well as to ensure their sustainability. This also shows the need for continued attention to emergent knowledge bases across different research domains including health.

Keywords: Intersectoral action, meta-narrative, review, governance, accountability, leadership, politics

KEY MESSAGES.

This meta-narrative review synthesizes cross-disciplinary evidence across four research traditions-Political science, Public administration, Environmental and Health sciences; such multidisciplinary knowledge is essential to advance the thinking and application of intersectoral action (ISA).

There is a need to move beyond the technocratic dimension of ISA and better understand the political and inter-organizational dynamics.

ISA has difficulty to reach a permanent equilibrium. It is a quasi-permanent process that requires continuous attention.

Introduction

There has been recently more global attention to intersectoral action (ISA) in health as the nature of challenges at global, national and sub-national levels become ever more complex. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the SDG objective of Universal Health Coverage have brought the vital role of the health sector into sharper focus. Although critically important, SDGs face growing constraints in response to social, economic and environmental challenges. Addressing aims towards healthier and better educated societies, gender equality, environmental sustainability and justice requires more collaborative work across sectors to devise more appropriate and effective solutions (United Nations, 2015) .

The impetus for ISA has been there for a long time, as, it has been perceived as a means to achieve more inclusive policies that address equity and social determinants in health (Solar and Irwin, 2010). This has led to further research on what works in terms of ISA and coordination in health. There have been several recent evidence reviews of ISA in health that tackle this dimension of the problem. These evidence syntheses of ISA include a rapid review (Ndumbe-Eyoh and Moffatt, 2013), as well as scoping reviews (Shankardass et al., 2012; Chircop et al., 2015; Dubois et al., 2015) focusing on (1) the conceptualization of ISA in health; (2) the relation of ISA to equity (Shankardass et al., 2014); and (3) the (local) implementation of ISA (Guglielmin et al., 2018).

While these reviews have all examined the literature in the health arena, the development of relevant theories and models span across other research traditions. Theory-building on mechanisms of coordination, institutionalization processes and dimensions of culture, values and power has been primarily conducted in political science, and more specifically in the field of public administration (Peters, 1998; Ling, 2002; Pollitt, 2003). The domain of environmental sciences has, from its outset, always dealt with the challenge of governing across sectors due to the all-encompassing nature of environmental challenges (Young, 2002). Thus, this review aims to explore the theories and their empirical application of ISA beyond applied research in the health sector. An interdisciplinary perspective and cross-learning from the application of social sciences in other fields is essential in health (Ridde, 2016) and would be beneficial for ISA in health by deepening our knowledge on theories and their framing (Corbin, 2017).

Although there have been sporadic efforts to cross-disciplines and capture disciplinary diversity (De Leeuw, 2017), there has been no systematic examination in the health literature of how ISA is explored in disciplines such as political science, public administration and environmental sciences. This means that there has been limited shared understanding and learning between these disciplines and public health. To enable cross-learning, it is therefore important to develop a clearer understanding of theory and its application to ISA across these disciplines. Thus, this review synthesizes both empirical and conceptual research, providing the scope for shared learning across disciplines. The main review question is: what are the theories, including theoretical developments based on empirical examples of ISA in the identified research traditions that can inform approaches to research on ISA problem-solving in the health sector?

For the purpose of this review, we worked on a definition which is broad enough to capture the theoretical diversity/variety across disciplines. We use the definition which captures multiple social sectors, and included government departments, non-profit and for-profit organizations or societies and ordinary citizens in the conceptualization as actors. Given the complex nature of ISA and limited understanding of frameworks and theories in health (Corbin, 2017; Bennett et al., 2018), we aim to work towards developing clarity on theoretical underpinnings and seek a better alignment between theory-building and applied research to strengthen the relevance of such insights in empirical and implementation research. This is the first review that looks at ISA from four different perspectives; political science, public administration, environmental science and health, an essential step if we want encourage the interdisciplinary research that is essential to generate solutions for today’s complex problems.

Methods

Important considerations in ISA include mechanisms of coordination, cooperation (Peters, 1998), accountability and power (Flinders, 2002) embedded in collaborative dynamics (Emerson, 2015). Failures to coordinate are often labelled or considered as ‘wicked problems’ in health policy research. Wicked problems can be recognized by their uniqueness, social complexity, interdependence and the inputs of several actors and multi-causal factors, with no definitive solution proposed (Rittel and Webber, 1973). Understanding the theoretical development and empirical enquiry in other disciplines dealing with socially complex phenomena can enhance its potential application in health (Greenhalgh et al., 2005). Thus, we adopted a meta-narrative synthesis methodology (Wong et al., 2013), as this enables better comprehension of a complex topic by understanding commonalities and contrasts across disciplines by describing how a tradition has extended over time within the defined scope of inquiry (Greenhalgh et al., 2004), and hence promoting a basis for cross-learning. This review methodology provides a unique tool for the synthesis of vast and complex evidence for policy processes (Greenhalgh et al., 2005). Considering these potential advantages in health research, too, meta-narrative reviews have gained more attention and have recently been used to synthesize knowledge in the domains of food sovereignty, security and health equity (Weiler et al., 2015), urban municipalities and health inequities (Collins and Hayes, 2010), patients’ trust of information on the internet (Daraz et al., 2019) and health research capacity development in low- and middle-income countries (Franzen et al., 2017).

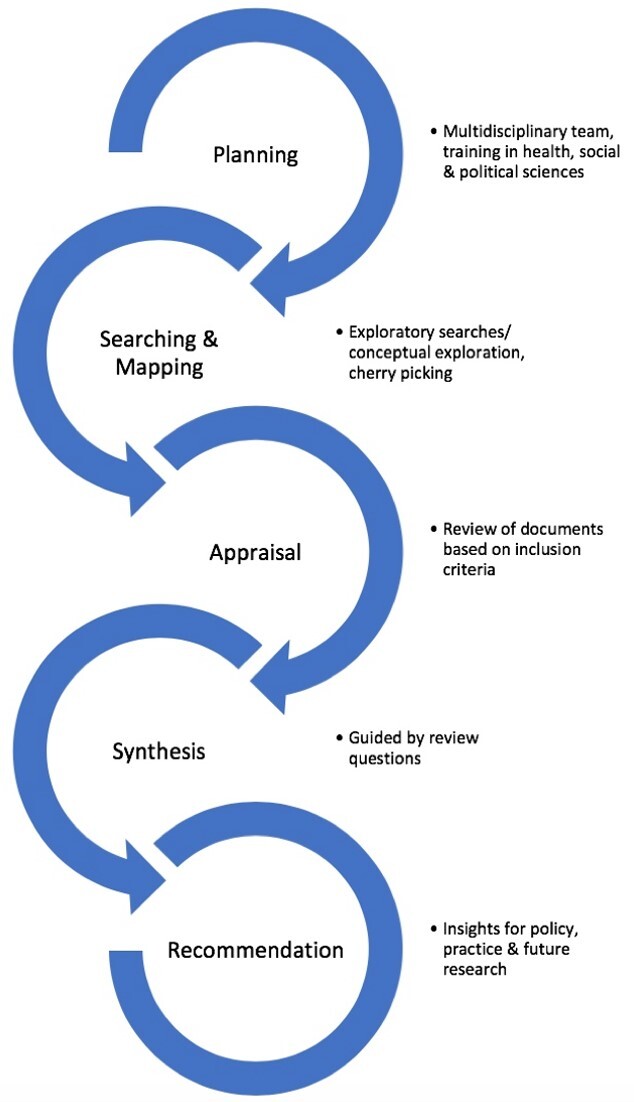

To encompass the concept of ISA across disciplines we use an adapted definition of ISA grounded in definitions of ISA formulated by the WHO (1997), Health Canada (2000) and Perera (2006); see Box 1 below. For this review, we followed the phases for meta-narrative review as explained by Greenhalgh et al. (2004, 2005). These phases include the following (Figure 1).

Box 1. Definition ISA.

‘A recognized relationship/mandate for working with more than one sector of society to act on an area of shared interest, to achieve more effective, efficient or sustainable outcomes that is difficult to achieve by one sector alone. Actors may include government departments (such as health, education, environment and other social sectors); actors from civil society organizations and the private sector’.

(Adapted from WHO (1997), Health Canada (2000), Perera (2006))

Figure 1.

Phases of the meta-narrative review.

Planning phase

This review is a starting point to explore theories and their applications for a larger empirical work that investigates implementation and governance of an inter-sectoral policy at local level. A multidisciplinary review team (SM, SVB, AM) with training and experience in health, overall social sciences and specifically in political science, medicine, anthropology and public health was formed. This phase started with an initial exploration of the databases SCOPUS and Google Scholar to identify the research domain that has covered the research on ISA. During our exploratory searches, we noticed that the research areas of health and environmental sciences provide a vast number of empirical studies on actual implementation and adaptation of ISA at the national, sub-national and local/municipal level. However, political science, and specifically the sub-discipline of public administration, also provide rich theoretical studies next to empirical studies. In this phase, we deployed the help of a librarian from the authors institute to refine the searches and to make sure that search keywords include terms covering the terminologies used in all research domains. We should note that research from public administration, as sub-discipline of political science, can include cross-referencing and overlap in concepts and definition as they are not mutually exclusive. Moreover, while political science tends to place more attention on political and structural factors driving ISA, public administration tends to focus on inter-institutional interaction. Selection of these domains were also limited by the expertise of the study team.

Search and mapping

In this phase, exploratory searches were performed and key domains were identified. The decision to include both empirical and theoretical work was made to enrich the review. We proceeded with searching the multidisciplinary database of SCOPUS, and checked the indexing of journal from all the identified research domains, to ensure the inclusion of key publications in these domains. We conducted searches in SCOPUS for the period from 1996 to 2017, which includes all PubMed and Embase contents from 1996 onwards, and for all peer-reviewed, articles in English on the concept of ISA. We used three search concepts and numerous relevant search terms to ensure the search strategy was as comprehensive as possible (Table 1). The three concepts captured ISA, its action through an intervention, and the mechanisms in which the intervention acted to promote ISA. We also used cross-referencing, snowballing and cherry-picking (Finfgeld-Connett and Johnson, 2013; Booth, 2016) to identify the seminal literature in public administration and political science with higher citations.

Table 1.

Overview of keyword search strategy

| Concept#1 | Concept#2 | Concept#3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Keyword 1 | Inter-sectoral | Policy | Cooperation |

| OR Keyword 2 | Intersectoral | Programme | Collaboration |

| OR Keyword 3 | Health-in-all-policy | Implementation | Integration |

| OR Keyword 4 | Cross-sectoral | Promotion | Coordination |

| OR Keyword 5 | Cross sectoral (sometimes sectora) and use of brackets | Intervention | |

| OR Keyword 6 | Multi-sectoral | ||

| OR Keyword 7 | Multisectoral | ||

| OR Keyword 7 | Whole-of-government | ||

| OR Keyword 8 | Joined-up-government |

Variations in spellings were used.

Appraisal phase

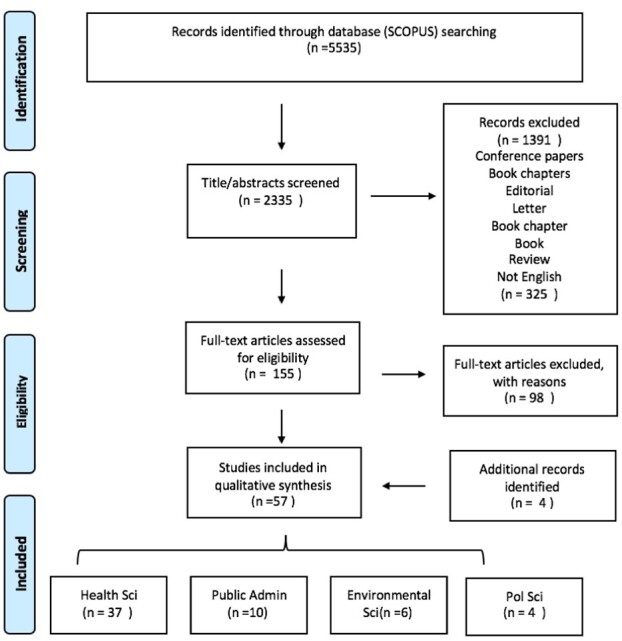

In this phase, all the eligible documents for inclusion and their relevance to the review were detailed (Table 2). Each document was appraised by two reviewers independently (SM and SVB) against the inclusion–exclusion criteria. We only selected the cases where roles of sectors were well defined, or where the policy mandate/engagement of the public sector in the partnership was well-defined. Articles which had the consensus of both were included immediately. In papers where there was no a clear clarity on the previous referenced criteria, a collective discussion was undertaken with the third co-author (AM), before taking a final decision. The PRISMA diagram (Figure 2) illustrates the flow of information through different phases.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Criteria | Included | Excluded |

|---|---|---|

| Timeline | 1996–2017 | Before 1996 |

| Countries | All countries | None |

| Languages | English | All other languages |

| Methodological Quality–Quantitative |

|

|

| Intersectoral action | Well-defined role of sectors, with one of the partners a public department/institution | Voluntary partnerships, not well-defined roles |

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Synthesis phase

This phase was guided by four objectives of the review: (1) to provide an overview of theoretical approaches in different research traditions; (2) to provide an overview of different ways of application/implementation in different research traditions; (3) to identify commonalities and different elements across research traditions.

Findings were summarized in tables and texts, and organized and incorporated into narratives, describing and discussing the relevant roots in each research domain, as well as theoretical and pragmatic aspects of ISA. We also used the key features of pragmatism, pluralism, historicity, contestation, reflexivity and peer review (Wong et al., 2013), as guiding principles in answering the key four questions directing the review.

Recommendations phase

With a final goal to pave the way for policy and practice recommendations, we share insights from the review that can inform policy and practice and suggestions for future research.

3 Results

Study characteristics

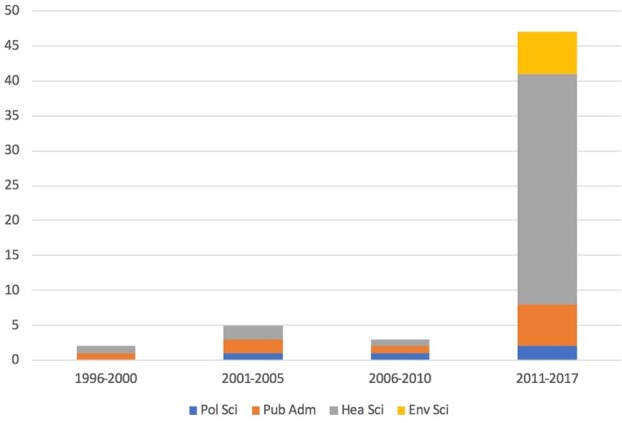

A total of 57 papers were included in the review, of which 37 (65%) were from health, 10 (18%) from public administration, 6 (10%) from environmental sciences and 4 (7%) from political science (other than public administration). Of these, 8 papers were conceptual in nature and 51 were empirical studies. Most of the conceptual papers were from political science and public administration, originating in the UK/Europe research institutions. Among the empirical studies, 3 papers were from North America, 21 from the UK/Europe, 11 from the Oceania, 10 from Africa, 17 from Asia and 7 from South America (Table 3). Among these papers, seven studies focused on multiple countries. In terms of number of studies, there is a considerable increase of papers in last decade, especially in health and environmental sciences (Figure 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of empirical studies

| Study location | |

|---|---|

| North America | 3 |

| UK and Europe | 21 |

| Oceania | 11 |

| Africa | 10 |

| South America | 3 |

| Asia | 17 |

| Scope of study | |

| Multi-country | 7 |

| Single country (national) | 26 |

| With-in one country (sub-national/provincial/municipal) | 16 |

| Study design | |

| Case study | 7 |

| Cross-sectional | 40 |

| Longitudinal | 2 |

| Retrospective | 1 |

Figure 3.

Number of publications from 1996 to 2017.

The findings of the data extracted are summarized in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 4.

Summary of key concepts from conceptual studies in the meta-narrative review

| Discipline | Author | Conceptualization/conceptual framework | Why it is required? | What is required? | What needs to considered? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Public Administration |

Peters (1998) | Co-ordination and horizontality | Improving public sector functioning | Accountability mechanisms, tackling challenges of redundancy, and coherence | Network perspectives, inter-organizational politics, relative power of interest groups, turf-wars |

| Flinders (2002) | Governance theory as analytical and theoretical tool | Societal wicked and complex issues | Leadership at ministerial and secretarial level, civil servant skills and capacity, budget flexibility. Establishing central mechanisms and new institutional units for coordination | Accountability, power, departmentalism, control-coordination, culture, window of opportunity | |

| Ling (2002) | Joined-Up-Government (JUG) | Insufficient conventional public service delivery, wicked issues | Organizational dimensions of culture and values, management of information and training. Interorganizational dimension of shared leadership, budget pooling, merged structures and teams | User focused services ‘one stop shop’, accountabilities and incentives for shared outcome targets and outcome measurement, and shared regulation | |

| Christensen and Lægreid (2007) | Whole- of-Government (WUG) | Counter the negative effects of siloization, sharing of information between public agencies for more secure world | Negotiative space, collaborative, engaging lower-level politics and Long-term engagement | Changes in structural arrangements and cultural practices (common ethics and cohesive culture), accountability systems | |

| (Amsler and O’leary, 2017) | Collaborative public management and collaborative governance | Complex and multi-faceted problems | Importance of institutional contexts in examining collaborative public management, collaborative governance, and networks | Family of governance practices (voice and collaboration) required, institutional contexts | |

|

Political science |

Pollitt (2003) | JUG | Increasing policy effectiveness, optimal use of resources, exchange of ideas and cooperation, seamless service delivery | flexibility, mutual intelligibility, mutual accountability and performance, culture of trust and joint problem-solving, adequate resources | Political dimensions, measuring impact and effectiveness, implications for politician, civil servants, professional service deliverers |

| Humpage (2005) | Whole-of-govt-approach | Catering Indigenous needs | Central leadership, capacity building govt agencies and communities, Formal collaborative partnership, reporting and evaluating mechanism | Move towards an instrument for governance than management tool, organization structure and culture slow to change | |

| Tosun and Lang (2017) | Policy integration | Policy problem or improve service delivery | Political leadership, structural/institutional changes, policy instruments, participation, capacity (human and institutional), Conscious organizational design, policy integration instruments | Organizational adjustment and accountability |

Table 5.

Summary of results from the empirical studies in the meta-narrative review

| Discipline | Research focus | Author/year | Geography | Conceptual framework | Methods | Conditions (key considerations) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Public Administration |

Sustainable development | (Christopoulos et al., 2012) | Coratia, Nepal, Mangolia | Metagovernance | Document review and interviews | Integrated modes of governance, access to information, knowledge, Empowerment of weaker players, Interactive learning, local practices |

| Program Ministries for Youth and Families, Housing, Communities, and Integration | Karré et al. (2013) | Netherlands | JUG/WUG | Document review and semi-structured interviews | Strategic (accountability, mandate, leadership, values) and operational issues (resources, time, culture, budget, staff) | |

| New employment and administration reforms (NAV) | Christensen et al. (2014) | Norway | Accountability framework in JUG. Political, administrative, legal, professional, and social accountability | Document analysis and survey | Multidimensional legal ability beyond hierarchical, leadership | |

| Sustainable Development plan and strategy | Vitola and Senfelde (2015) | Latvia | Policy coordination | Document analysis and survey | Informal aspects (organizational culture, social capital, networks) | |

| Social Inclusion Agenda | (Carey et al., 2015) | Australia | JUG | Semi-structured interviews | Coherence between institutional and operational level | |

| Political science | Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) | (Kraak, 2011) | South Africa | Horizontal coordination | Document review | Civil servant capacities-dialogic interaction, situated knowledge, boundary spanning |

|

Environmental sciences |

REDD+ implementation | Ravikumar et al. (2015) | Six countries (Brazil, Peru, Cameroon, Tanzania, Indonesia, Vietnam) | Multilevel governance | Likert scale rating, Qualitative data: interviews, field notes and observations | Context-specificity, technico-political support, data-sharing, interest and power understanding |

| Integrated approach to disaster risk management (DRM) and climate change adaptation (CCA) | Howes et al. (2015) | Australia | WUG and network governance | Literature review, comparative case study of reports, semi-structured interviews, workshop | Shared policy vision, multi-level planning, integrating legislation, networking organizations, and cooperative funding | |

| National adaptation of REDD+ | Fujisaki et al. (2016) | Five countries-Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Papua New Guinea, and Vietnam | Not mentioned | Policy document review and key-informant interviews | Institutional arrangements-space, participation(political, technical, resource-oriented) and communication, legitimacy and ability influenced by existing mechanism | |

| Integration of REDD+ in existing national agendas | Korhonen-Kurki et al. (2016) | Brazil, Cameroon, Indonesia, Nepal, Papua New Guinea, Tanzania and Vietnam | Multi-level governance | Interviews | Building on existing mechanisms, explicating institutional complexity, flow of information, trust, regulatory role | |

| Climate policy integration | Di Gregorio et al. (2017) | Indonesia | Policy coherence and integration | literature, official policy documents and interviews | Power and interests, fragmented responsibilities, departmental resistance | |

| Climate change and water-energy-food nexus | Pardoe et al. (2017) | Tanzania | Not mentioned | Document analysis and key-informant interviews | Institutional frameworks, power imbalances, data sharing | |

| Health sciences | Nutrition | Webb et al. (2001) | Australia | Not mentioned | Survey | Organizational development ,capacity building, formative evaluation method, planned joint action, strong relationships |

| Nutrition | Fear and Barnett (2003) | New Zealand | Not mentioned | Case study-Project reports, interviews, govt. documents, published research | Commitment, value collaboration, entrepreneurial style of leadership with agency autonomy | |

| Nutrition | Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al. (2016) | Iran | Kingdon’s multiple stream model (agenda setting and implementation) | Qualitative methods | Presence of evidence, legal instruments, policy entrepreneurs, political commitment | |

| Nutrition | Pomeroy-Stevens et al. (2016a) | Uganda | Not mentioned | longitudinal mixed methods (budget data, interviews) | Unified identity, human resources, sustainable structures, coordination, advocacy, and adaptation to local needs | |

| Nutrition | Pomeroy-Stevens et al. (2016b) | Nepal | Not mentioned | longitudinal mixed-method design | Human resources, ownership, bottom-up planning, coordination, advocacy, and sustainable structures | |

| Nutrition | Kim et al. (2017) | India | Degree of convergence | Semi-structured interviews | shared goals/motivation, clear leadership, mutual understanding of roles close inter-personal communication and vicinity, understanding of roles and responsibilities | |

| Nutrition | Harris et al. (2017) | Zambia | Not mentioned | longitudinal, qualitative case-study methodology | Policy coherence, political and financial commitment, combination of material, strategic and technical support | |

| Early childhood Development | Johns (2010) | Rural Australia | Conceptualization around social capital, trust, leadership | Case study methodology, multiple case study design | Social capital, leadership influencing processes roes and structure, environmental factors (structural and broader issues) | |

| Urban health/healthy cities | Bergeron and Lévesque (2012) | Canada | Not mentioned | Case study-Document review and interviews | Mix of formal and informal collaboration mechanisms | |

| Urban health/healthy cities | Kang (2016) | Korea | Tool to measure inter-agency collaboration and integration | Postal survey | Sufficient resources, knowledge and expertise, common vision and goals, close relationships, and leadership | |

| Alcohol | De Goeij et al. (2016) | Dutch | Not mentioned | Retrospective multiple case study (document analysis and in-depth interviews) | Framing as societal problem, enthusiastic employees, resources (money and time), political support, local media, dedicated leadership | |

| Alcohol and obesity | Peters, Klijn, et al. (2017a) | Netherland | Policy Networks | Web-based survey | Network management and trust for policy coordination and integration | |

| Alcohol and obesity | (Peters et al., 2017. ) | Netherland | Not mentioned | Multiple case study | Intersectoral composition from policy development stage | |

| Obesity | Hendriks et al. (2013) | Netherland | Behaviour change wheel | Case study design (in-depth interviews) | Sufficient resources (time, money, and policy free space), close social ties and physical proximity, reframing health issues in common language | |

| Mental Health | Horspool et al., 2016) | United Kingdom | Not mentioned | Cross-sectional qualitative (interviews) | Local context (geography and population size of a location),previous cross-sectoral experience and perception, stakeholder support, understanding of roles and responsibilities of other agency | |

| Primary Health Services | Anaf et al. (2014) | South Australia and northern territory | Not mentioned | Qualitative case study (interviews and document review) | Sufficient human and financial resources, diverse backgrounds and skills and personal rewards for sustaining | |

| Malaria | Mlozi et al. (2015) | Tanzania | Not mentioned | Documentary review, self-administered interviews and group discussion | Engagement of involved sectors in planning and development of policy guidelines, aligning the sectoral mandates and management culture | |

| School health | Pucher et al. (2015a) | Netherlands | DIagnosis of Sustainable Collaboration (DISC) model | Cross-sectional quantitative data | Perceived common vision, trust and investment of resources | |

| School health | Pucher et al. (2015b) | Netherlands | DIagnosis of Sustainable Collaboration (DISC) model | Mixed-methods approach: quantitative data and interviews | Involved and informed decision-making process, supporting task accomplishment, coordination of collaborative process | |

| School health | Tooher et al. (2017) | Australia | Not mentioned | Qualitative study: interviews | Communication of policy decisions, personal relationships, timing of collaboration, skilled stakeholder for aligning agendas. Champions, support of local leaders | |

| School health | De Sousa et al. (2017) | Brazil | Mendes-Gonçalves on the working process for health care and the elements | Interviews and observations | Structured and shared planning, training of professional, financial and material resources, willingness to work together | |

| Tobacco | Lencucha et al. (2015) | Philippines | JUG | Interviews | Power differential, vested (industry) interest, challenging institutional arrangements | |

| Health equity | Storm et al. (2016) | Netherlands | Theoretical model for reducing inequities | Document analysis and interviews | Strengthen existing links, role clarity, related activities and objectives, political choice | |

| Health equity | Storm et al. (2016) | Netherlands | Not mentioned | Document analysis, questionnaire, interviews | Good relationships, positive experiences, a common interest, use of same language, sufficient resources, supportive departmental managers and responsible aldermen | |

| Health equality | Scheele et al. (2018) | Scandinavian countries | health equity governance (politics, organization and knowledge) | Interviews | Political commitment and budgeting, horizontal and vertical coordination, presence of evidence | |

| Municipal/local govt | Spiegel et al. (2012) | Cuba | Not mentioned | mixed methods design, using a two-phased descriptive approach | Accountable health councils, organization structure, policy orientation, political will | |

| Municipal/local govt | Larsen et al. (2014) | Denmark | Not mentioned | Document review and semi-structured interviews | Political support, public engagement and participation, local media, establishment of health funds and network | |

| Municipal/local govt | (Hendriks et al. (2015) | Dutch | COM-B system [Capability, Opportunity, Motivation (COM), and Behavior (B)] | Semi-structured interviews and observations | Flatter organizational structures and coaching of officials by managers | |

| Municipal/local govt | Holt et al. (2017) | Denmark | Theory of organizational neo-institutionalism | Ethnographic study- semi-structured and informal interviews | Framing of problem, essential for policy or intervention. Narrow focus, inadequate to address broader structural determinants | |

| Municipal/local Govt. | Hagen et al. (2017) | Norway | Not mentioned | Cross-sectional study-Register and survey data | Specific public health coordinator, using cross- sectorial working groups, inter-municipal collaboration, confidence in capability, established cross-sector working group | |

| Health in All Policies (HiAP) Evaluation | Baum et al. (2014) | Australia | Applying the programme logic approach to HiAP | Semi-structured interviews, online surveys of policy actors, detailed case analysis | Presence of a co-operation strategy, Health Lens Analysis process, central governance-enabled shared understanding, uncover and negotiate for inclusive participation | |

| HiAP conduciveness | Friel et al. (2015) | WHO western Pacific region | WHO 2013 framework Demonstrating a Health in All Policies Analytic Framework for Learning from Experiences | Review of peer reviewed and grey literature, interviews | Evolving and sustaining partnerships, clear strategy, infrastructure and sustainable financing mechanisms, linking individual agency with structural changes organizations | |

| HiAP implementation support | Delany et al. (2014) | South Australia | South Australian HiAP approach (Baum et al., 2014) | Semi-structured interviews and workshops | Resourced centrally mandated unit, Joint governance structures and mandates, appeal of the unit, establishing trust and credibility, aligning core business and strategic priorities | |

|

Methodological application: HiAP lessons |

Baum et al. (2017) | South Australia | Institutional policy analysis framework (ideas, actors, institutions) | document analysis, a log of key events, detailed interviews, two surveys of public servants. | Dedicated HiAP Unit, A new Public Health Act, Existence of a supportive, knowledgeable policy network, political support, supportive network of public servants | |

|

Methodological application: Qualitative comparative analysis |

Peters et al. (2017b) | Netherlands | Policy networks | Web based survey | Network diversity, network management for resource mobilization and reduction of adversity and complexity | |

| Methodological application: Realist methodology | Shankardass et al. (2015) | Sweden, Quebec, Australia | Realist-CMO configuration | Systemic literature search and interviews | Stakeholder previous experience of working in Health Impact Assessments, thorough interministerial process, legislative mandate | |

|

Methodological application Coalition theory |

O’Neill et al. (1997) | Canada | Coalition theory | Historical document review, questionnaire, interviews | Effective collation among acquaintances, strong political link, believe in the cause, expert (informational resource) or power structure of the community (positional resource), information channels, persuasive, conflict resolution type of leadership |

In political science and public administration, Joined-Up Government (JUG) research is embedded in broader public sector reform and provide institutional analysis, embedded in a description of political context. In the more applied domains of environmental sciences, multi-country studies that examine national adaptation and cross-country examinations are frequent. The analytical and conceptual framing is focused on governance and the studies are explicit about underlying relations of actors vested in power, interest and values. In health, the most common analytical method remains case studies to identify barriers and facilitators. However, more recently, some studies have been ethnographic in study design and detail the context and processes (Holt et al., 2017) that can draw out the relationships between context, mechanisms and outcomes (Shankardass et al., 2014). Others are grounded in the application of qualitative-comparative analysis methodology (Peters et al., 2017b), or theory-based logic models for complex evaluations (Baum et al., 2014). These studies stem from lack of decision-making data, the absence of monitoring and evaluation frameworks, poor understanding of contextual and other contributing factors and ascertaining the pathways of ISA functioning and in the grand scheme of things the link between ISA and equity.

Tracing the roots and concepts of ISA

Joined-up Government in public sector reform

For almost two decades, the JUG and Whole of Government approaches have been implemented, tested and tried in many countries. The JUG model evolved under New Labour in Britain in the 1990s and was subsequently adopted in other settings: Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Sweden, USA (Ling, 2002), Norway (Christensen et al., 2014) and the Netherlands (Karré et al., 2013).

‘Joined-up-government’ is the term used to capture the changing nature of the central government and state, traditionally structured to work in ‘siloes’, ‘cages’ or ‘chimneys’ (Flinders, 2002) manner and not equipped to deal with cross-boundary issues. This JUG approach is sometimes also referred as to ‘post-New Public Management reform’ (Christensen and Lægreid, 2007). Whereas the era of New Public Management promoted silos and pillars of public sector institutions, focusing on ‘single-purpose organizations’ (Flinders, 2002), the JUG era refocused on building a strong unified set of values and collaboration among public servants. It overlaps to a great extent with the ‘Whole- of-Government’ approach used in Australia (Christensen and Lægreid, 2007) focusing on the dynamics of interaction between institutions, and ensuring challenges related to control, coordination and accountability.

Collaborative governance in environmental research

Research on joint working and collaborative (Emerson, 2015) or ‘networked’ (Stoker, 2006)or ‘multi-level’ (Bache et al., 2016) governance in recent years has intensified, spurred in part by the United Nations-Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (UN-REDD+) programme and other collaborative multisectoral partnerships within the context of climate change (Howes et al., 2015; Ravikumar et al., 2015; Korhonen-Kurki et al., 2016; Pardoe et al., 2017). The REDD+ mechanism was proposed under the United National Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), promoting technical assistance and capacity building initiatives and policy-related advice for implementation (Corbera and Schroeder, 2011; Thompson et al., 2011). Research on collaborative governance was also accompanied by a better understanding of power dynamics and interests among different stakeholders. Environmental research stresses the need for multi-actor engagement; that is, the need to engage with civil society, indigenous groups and forest-dependent communities as they are mostly affected by the implementation in this policy domain. Responsiveness to multiple stakeholders remains a balancing act, as priorities and tensions arise and it is difficult to build consensus with competing views (Fujisaki et al., 2016). Other challenges include the poor alignment of institutional boundaries and the blurring of accountability (Korhonen-Kurki et al., 2016), a common problem in multi-actor partnerships. As well, climate change adaptation and disaster risk management require an adaptive governance mode which also provides an impetus for the creation of networks (Howes et al., 2015).

Health: from Alma Ata to HiAP

The perceived need for ISA in health has been around for some time. In the 1970s, the Alma Ata declaration on social determinants of health brought the importance to the fore. Later, the first global conference for Health Promotion, with the launch of Ottawa Charter 1986, became a forerunner of efforts by the global health community to consider the role of other sectors in achieving health and well-being. By 1988, during the second WHO Global Conference on Health Promotion in Adelaide, the concept of ‘Healthy Public Policy’ was emphasized and key areas for ISA, namely food and nutrition, tobacco, and alcohol, were identified (WHO, 1988). A decade later, in 1997, an international conference in Canada on the relevance of ISA for health in the 21st century, assessed its progress and relevance for future challenges. The concept of HiAP was mainstreamed initially in the European Union with the launch of the book ‘Health in All Policies: prospects and potential’ (Stahl et al., 2006) and was adopted globally at the 8th Global Conference on Health Promotion (8 GCHP) in Helsinki, Finland in 2013 (WHO, 2013). These more recent studies explore HiAP implementation support (Delany et al., 2014), conduciveness (Friel et al., 2015), concepts and evaluation (Baum et al., 2014).

Narrative synthesis

Rationale for undertaking ISA in in health, environment and public sector reform

In health, ISA has remained a long-standing consensus to address health holistically. The WHO’s focus on health systems was strengthened under the leadership of Margaret Chan (Samarasekera, 2007), with the emergence of HiAP inquiry and more recently with the emphasis on SDGs. The WHO’s report of Commission on the Social Determinants of Health in 2008 effectively established that the conditions in which we live, work, grow and age affect our health and are in turn shaped by political, social and environmental decisions (CSDH, 2008). Coordinated action across sectors is considered essential to form and strengthen linkages to address social, economic and political determinants of health and reduce health inequities. The SDG framework emphasizes how interlinked goals in health require improvement in the other social outcomes, and hence the necessity of cross-sectoral collaboration (Nunes et al., 2016). In addition, the new paradigms of health security, and the One Health Approach, call for collaboration and coordination across all relevant sectors, ministries, agencies and stakeholders in order to address the emerging epidemic of non-communicable diseases (WHO, 2019).

As well, the global impact of climate change requires working vertically between international, national, and sub-nation levels of decision-making and also working horizontally across sectors (Korhonen-Kurki et al., 2016). This nexus approach emphasizes the need of inter-linkages between different sectors for coordinated relationships that promotes synergies and trade-offs, and which enables feedback. Tackling inter-dependencies through cross-sectoral coordination are critical to achieving results supporting climate sustainability and avoiding the pressure points (Pardoe et al., 2017).

Despite the growing intensity in published research, there still remains the problem of coordination, which has been called as ‘philosophers stone’ (Seidman, 1970; Jennings and Krane, 1994; Peters, 1998). This is due to the nature of how the public sector in different settings has evolved and gradually expanded. Government departments evolved as single purpose organizations, and this institutional architecture makes coordination a challenge in itself, and also creates a ‘turf’ problem, which creates inertia and unwillingness to share hard-won technical and monetary resources (Karré et al., 2013).

Focus of different knowledge domains

Theory-building in political science/public administration

In public administration, the primary focus has been on public sector reform, such as the shift in roles and functioning of institutions and their patterns of engagement when undertaking ISA (Ling, 2002). Considerable attention is devoted to a better understanding of coordination failures, and associated challenges of control and coordination, accountability and power (Peters, 1998; Flinders, 2002). Three major reasons for failing coordination have been identified: when two organizations perform the same role of coordination; when no organization performs the task of coordination; and when the policies catering to the same population have different goals and requirements, which leads to ‘policy incoherence’ (ibid). Enhancing ‘joined-upness’ hence calls for approaches that align institutional aims, management systems, culture and incentivises them to work together (Ling, 2002; Pollitt, 2003).

The cultural shift in organizations has been difficult to achieve, as change that involves moving away from a hierarchal culture and requires the acceptance of a learning culture with more tolerance for uncertainties and ways to manage them (Humpage, 2005). This requires the creation of values and trust, promoting team-building, with the intent of establishing a cohesive work culture (Ling, 2002). These shifts in culture are often slow, grounded in norms, values and practices, that require time.

Applied domains of environment and health

The knowledge domains of environment and health are empirical in nature and more outcome or goal-oriented, as they assess interventions or evaluate policies and programmes.

In environmental sciences, challenges in vertical and horizontal coordination have been discussed within the context of climate change and carbon emissions. The focus of enquiry has been on improving multi-level (Ravikumar et al., 2015; Korhonen-Kurki et al., 2016), collaborative or networked governance (Howes et al., 2015). The REDD+ studies focus on institutional complexity and adaptation of the REDD+ framework for implementation at the national and sub-national level in developing countries (Howes et al., 2015; Ravikumar et al., 2015; Fujisaki et al., 2016; Korhonen-Kurki et al., 2016). The studies linking water, energy and food security examine policy coherence, overlap and complementarities in sectoral approaches (Pardoe et al., 2017). Research on climate policy integration examines the level of integration of mitigation and adaptation objectives and policies (Di Gregorio et al., 2017).

In health, we see mainly two approaches. The studies with specific policy approaches focus on a particular policy/public health problem such as nutrition (Webb et al., 2001; Fear and Barnett, 2003; Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al., 2016; Pomeroy-Stevens et al., 2016a; Harris et al., 2017), early childhood development (Johns, 2010; Bilodeau et al., 2018), Malaria (Mlozi et al., 2015), school heath (Pucher et al., 2015a,b; De Sousa et al., 2017; Rebecca Tooher et al., 2017), Tobacco (Lencucha et al., 2015), alcohol and obesity (Hendriks et al., 2013; de Goeij et al., 2016; Peters et al., 2017a), mental health (Horspool et al., 2016) and primary health services (Anaf et al., 2014). These studies have considered how intersectoral coordination has been deployed in their formulation and implementation.

The second approach is systemic in nature, and this research does not focus on a particular policy or programme or the political environment, but rather considers the ‘will’ and institutional arrangements for promoting ISA. The focus of these studies has been in the implementation, conduciveness, evaluation of HiAP initiatives and equity effects within the health system (Storm et al., 2016; Scheele et al., 2018), the role of local governments (Spiegel et al., 2012; Larsen et al., 2014b; Holt et al., 2017) and urban health/health in cities (Bergeron and Lévesque, 2012; Kang, 2016). In recent years, interest has moved beyond traditional research designs and towards developing a more robust methodology for ISA to better capture the dynamic processes and understand the associated challenges (Baum et al., 2014; Shankardass et al., 2015; Holt et al., 2017; Peters et al., 2017b).

Implementation instruments

In this section, we discuss the formal and informal structures that have been created to support ISA, including the informal networks that emerge, the key components of an enabling institutional environment.

Setting up new formal structures

We observed a range of policy instruments that have been applied in various settings, such as, formal institutional structures to enhance horizontal coordination (Peters, 1998; Bakvis and Juillet, 2004). Interdepartmental committees are the most prevalent structural forms in practice, as they bring together different partners to work together in public sector. However, there remains some skepticism as to their effectiveness because of departments’ competing choices and demands unless caution is taken in their design and being affiliated to secretariats and specialist agencies (Peters, 1998; Greer and Lillvis, 2014). Another common mechanism is the creation of task forces, task teams or working groups, composed of experts, academics and community leaders, who are tasked with a specific problem and have to come up with a solution in a limited time frame. Third, central level agencies and coordinating units, such as those within a Prime Minister office in parliamentary settings, are high-level (policy)-level strategies with the direct responsibility, leadership and legitimacy to enhance coordination.

The applied domains of health and environment provide empirical examples of these new institutional designs to promote better coordination across sectors. In their study of the implementation of REDD+ across seven countries, authors found that coordination mechanisms in the form of inter-ministerial working groups, steering committees, and national task forces were readily used. These mechanisms were either built on existing structures or new institutions were established to take up the role of coordination (Korhonen-Kurki et al., 2016). In the health studies, one could identify the creation of multisectoral committees from regional, national to local level (Pomeroy-Stevens et al., 2016a,b), intersectoral meeting groups, steering committees, working groups (Hagen et al., 2017) and interagency committees (Lencucha et al., 2015) to spearhead coordination process.

However, the effectiveness of these inter-departmental groups and task forces is often challenged as they have no formal authority over other departments. In extreme cases, this can lead to the creation of a separate administrative structure that is not well integrated within existing departments, further causing ambiguity in implementation and accountability mechanisms. Hence, the creation of these supporting structures requires also an emphasis on connectivity or on the foundations of existing mechanisms and institutional arrangements (Fujisaki et al., 2016).

Emergent networks

Beyond working with formal structures, we also found examples of informal, emergent coordination. Informal ISA has been given a boost by information communication technologies, these patterns of communication that can engender collaboration and action among like-minded individuals, and generate networks. These informal networks play an important role in implementation and in solving practical problems. At times, they can become more effective than formal structures (Friel et al., 2015; Vitola and Senfelde, 2015), as these networks bring the role of social capital and reciprocity to the fore.

In the health sector, Bergeron and Lévesque (2012), exploring the collaboration between five sub-national ministries to promote active communities, explain that formal structures embedded in committees promote the interaction among identified ministries and stakeholders, while informal collaboration in form of sharing of information among civil servants at same time nudges other ministries to promote change by keeping them informed of the discussion and meeting processes (Bergeron and Lévesque, 2012).

There has been an increase in the proliferation of policy networks, both in health and environmental studies. For example, Peters et al. (2017a) studied policy networks in 34 Dutch municipalities, focusing on reducing overweight, smoking and alcohol/drug abuse, and found that policy networks bring together diverse actors, with different values, interests and perceptions. However, the performance of these networks lies in creation of trust and network management, to guide and facilitate interactions. Meanwhile, Howes et al. (2015) examine informal ISA within the context of three extreme climate-related events in Australia, and perceive these arrangements as an effective instrument to regulate conflict between departments by overcoming the structural barriers of bureaucratic hierarchy.

An enabling institutional environment

A policy orientation towards ISA can create some momentum, but needs to be supplemented along the way with supporting structures. In the absence of such support, it is difficult to sustain change and the risk is reversion to the status quo. The hardware elements refer to the provision of funds, human resources, management systems, adequate service delivery, that are concrete and measurable, whereas software elements include cultural aspects of ideas, values, interests, norms that guide the interaction (Sheikh et al., 2011). We also share important aspects of leadership and political will, and the lines of accountability imperative for ISA.

Hardware

The importance of adequate structural support in the form of financial and human resources, and management systems to capture data to enable shared policy vision has been stressed in the literature (Fear and Barnett, 2003; Anaf et al., 2014; Shankardass et al., 2014; Mlozi et al., 2015; Pomeroy-Stevens et al., 2016b; Pardoe et al., 2017). This is also intrinsically linked to political commitment as it provides the partnering institutions a mandate to work together. An example from the Malaria Control Programme in Tanzania demonstrates that the absence of a joint coordination mandate and the exclusion of engaged sectors during the early phases of policy planning and development resulted in lack of a national framework with further implications on budgetary allocation (Mlozi et al., 2015). Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al. (2016) had similar findings from Iran, studying the development and implementation of HiAP, where non-health department strategic plans did not have any priority or mandate for inclusion of provincial Health Master Plans, affecting HiAP’s impact. In South Australia, institutional support in the form of a well-resourced centrally mandated unit and alignment of policy priorities across departments contributed in supporting the implementation (Delany et al., 2016).

Though identified as the most common structural supports, financial and human resources are also the most persistent challenge. Lack of adequate human resources can lead to faulty or inadequate implementation (Anaf et al., 2014; Pomeroy-Stevens et al., 2016a,b; Tosun and Lang, 2017). Joining up is costly, in terms of staffing, technological developments and time. Brazil’s experience of a ‘Health in School’ programme (De Sousa et al., 2017), ISA for primary health care in Australia (Anaf et al., 2014), coordination between agencies to support nutrition in New Zealand (Fear and Barnett, 2003), and the coordination action between water, agricultural and energy policies to address climate change in Tanzania (Humpage, 2005), all point to shortages of financial and material resources and time as key limitations for enhancing ISA. Assuring dedicated resources, particularly at lower levels of policy implementation, is essential for success.

Software

ISA brings in a number of stakeholders to work together, with differences in interests, values and power. Ideally working in a coordinated and mutually productive environment, institutions and actors can negotiate over respective roles and responsibilities when undertaking ISA. However, this is challenging, due to the centralized nature of bureaucracies in many different settings, and the potential for bureaucratic rivalry (Peters, 1998; Flinders, 2002). Power differentials have been mentioned as a factor that encumbers ISA, especially when the treasury or ministry of finance is involved (Ling, 2002). We also find them between local communities, NGOs on the one hand and administrations on the other (Ravikumar et al., 2015; Di Gregorio et al., 2017; Pardoe et al., 2017) and in partnerships engaging the private sector and inter-agencies for collaboration (Lencucha et al., 2015). Representation of actors alone cannot ensure coordination as they cannot negate the political values and conflict (Karré et al., 2013) that are embedded in institutional interests and path dependencies (Fujisaki et al., 2016).

Studies in environmental sciences such as REDD+ and Climate Policy Integration contend that climate change is still considered too much as a technical challenge, whereas issues are often political in nature, and understanding the underlying interest and power relations across actors and across levels is key (Ravikumar et al., 2015; Di Gregorio et al., 2017). The implementation of REDD + policies require active participation of the local community, indigenous groups and forest-dependent communities. However, their participation is often tokenistic (Korhonen-Kurki et al., 2016).

In order to navigate these terrains and to bring coherence and sustainability to ISA, long-term trust promoting culture has been suggested, through sensitization and capacity building initiatives. Capacity-building at all levels, from the political to level all the way down to service delivery, need to be oriented towards improving communication skills for better collaboration (Webb et al., 2001; Tosun and Lang, 2017). Flinders (2002) argues that departmental structures are usually built in a manner that does not promote cross-departmental collaborations and hence civil servants and core executives require specific competencies to address cross-cutting problems and inter-organizational policymaking.

In Brazil’s ‘Health in School’ programme, designers found that absence of competence training caused hurdles in making ISA operational (De Sousa et al., 2017), as trainings can aid in developing a shared understanding and identifying the roles of each sector. Effective ISA training should sensitize and promote capabilities for carrying out inter-departmental activities, especially with regard to instruments and motivation to share information and data for decision-making, as well as effective communication skills to convince other sectors that are not directly engaged or participating. Similar findings emerged from authors studying the coordination between maternal and child nutrition, where they found that close inter-personal communication and understanding of each other’s roles and responsibilities acted as enabling mechanisms for effective ISA (Kim et al., 2017).

Leadership

To navigating the boundaries of ISA, the need for a strong leadership has been documented in both the theoretical and empirical literature. Such leadership is commonly referred as ‘linking pins’ (Karré et al., 2013), ‘boundary spanners’ (Ling, 2002) or ‘champion’ (Baum et al., 2017; Tooher et al., 2017) or ‘facilitator’ (Bryson et al., 2006). This provides the essential interface between structures, spanning boundaries, connecting agencies, departments and sectors to break down silos, change behaviours and initiate join-decision-making action. The leadership competencies required include skills to advocate, persuade and to resolve conflicts. In fact, the style of leadership required is collaborative in nature, where one able to work horizontally, form partnerships across sectors and more specifically be inclusive, supportive, promoting trust, all of which bolsters communication, information-sharing and innovation as intermediary processes for effective ISA (Pucher et al., 2015b). In examining the implementation of healthy city networks at different levels (O’Neill et al., 1997) found that a more persuasive style of leadership, comprised of negotiating, nudging and bargaining was more effective than an authoritative style of consensus-building and more appropriate in intersectoral groups, as it fosters cohesiveness. Leadership at the political level is also important as this enables the shaping of mandates and aligning of systems, structures and processes to fit the need of ISA, but in itself not adequate (Humpage, 2005; Karré et al., 2013). Leadership at all levels, from the top, the level of permanent secretary (Flinders, 2002), to the highest administrative ranks (Humpage, 2005) and down to the local district level (Kim et al., 2017), is required for full engagement and ownership. However, Tooher et al. (2017) cautions towards viability of such efforts in long term, where mechanisms are contingent on champions, and suggests that efforts should move towards institutionalization through support from local leaders to change policy practices (Tooher et al., 2017).

In situations of high uncertainty, which is the case with tackling wicked problems such as those related to climate change, it is important to be able to nurture relations. ‘Boundary spanners’ extend and establish their networks and bring on the capacity to solve problems through social capital, making them enriched in skills and competencies to understand interdependencies and create engaging, respectful and trusting relationships (Howes et al., 2015). Kraak (2011) sees their role as catalysts or brokers, as they can cross red-tapes by leveraging trust to enable asymmetries of information and facilitate goal adjustment, this is linked to inter-personal style, skills and knowledge. The Dutch experience of working with different programme ministries shows that a boundary spanning role was adopted more by older civil servants working in the background, than by younger civil servants, who found it more lucrative for their career prospects to stay in their own departments (Karré et al., 2013). The complex and contradictory roles played by boundary spanners, often places them in a stressful positions having to deal with ambiguity and conflict, leading to lower satisfaction and higher turnover rates (Crosno et al., 2009) all of which points to the need for institutional design and executive support structures, and building an institutionalized support (Stamper and Johlke, 2003; van Meerkerk and Edelenbos, 2018).

Political will

The political nature of ISA is very well demonstrated in the literature, described variously as political support, priority, commitment and the will to be able to formulate and implement inter-sectoral initiatives. Baum et al. (2017) conducted an institutional analysis of the South Australian experience of HiAP, and noted that high-level political support and the presence of a policy network that is supportive as well as knowledgeable proved to be an important factor; furthermore, changes in ministerial leadership or high-level administrative appointments were considered a challenge for programme outcomes. Humpage (2005), examining the Whole-of-Government approach in the context of indigenous challenges in Australia and New Zealand, observed that limited political commitment was a hindering factor in an ISA approach and proved to be a roadblock for effective shifts in culturally indigenous specific policy discourse.

While political commitment at the highest level is key, studies focusing on municipalities and local health councils also found that political commitment at these devolved ‘frontline’ levels is essential. Scheele et al. (2018) and Larsen et al. (2014b), examining Scandinavian municipalities, found that political commitment at the local level during the initial phase of discussion aided the framing and adaptation of policy documents and helped generate the momentum for collaboration through stakeholder buy-in. The need for political will, linkages, support and commitment has been extensively documented as being crucial for the initiation and maintenance of the process of collaboration (Spiegel et al., 2012; Baum et al., 2014; Storm et al., 2014; Larsen et al., 2014a; Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al., 2016; Goeij et al., 2017; Harris et al., 2017; Tosun and Lang, 2017), and is an important consideration at all levels of governance.

Intersecting accountabilities

Working across sectors often makes accountability lines highly ambiguous. This situation arises primarily because a complex network delivery needs to be able to identify ‘who did what’ when organizations blend their work (Peters, 1998). Another ambiguity lies in identifying the chain of accountability, or ‘the problem of many eyes’ or ‘accountability to whom?’ as traditional hierarchical accountability clearly does not suffice (Christensen et al., 2014). As Pollitt (2003) argues, this requires a multi-dimensional accountability concept, comprising a cluster of accountability mechanisms. Christensen et al. (2014) also propose a ‘family’ of accountability mechanisms that include traditional political and administrative accountability, plus additional legal, professional and social accountability.

Below, we describe empirical examples of political/administrative, legal and social accountability. We did not find any conceptual or worked empirical example of professional accountability, which relates to obliging to professional norms, standards and expertise (Christensen et al., 2014).

Political and administrative accountability

Political accountability is the upward mechanism which denotes the interaction between political and administrative leadership and the lawmaking and executive bodies. In the larger scheme of things, this can also be seen as a subset of principal-agent relationships in which the voting class delegates the power to elected representatives, who in turn delegate the command to cabinet and civil servants (Byrkjeflot et al., 2014) . Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al. (2016), studying the development and implementation of HiAP in Iran, found that non-health sectors are accountable for their core tasks and duties but tasks assigned to them by the health sector are not in their primary purview, highlighting the difficulty in reinforcing horizontal accountability across sectors.

Legal accountability

Legal accountability provides an external oversight mechanism in the form of laws and entitlements as legal instruments. These instruments can act as a tool to hold public institutions accountable and serve as means of fairness and justice for individuals and society in general. Scheele et al. (2018), drawing on the experience of local governments to address equity in Scandinavia, conclude that the presence of legislation that obligates municipalities to implement inter-sectoral policies shows national commitment that compels municipalities to address health equity through budgetary allocation. Delany et al. (2014), examining the support for early implementation of HiAP in the South Australian context, found that presence of the Public Health Act, which was developed according to HiAP principles, provides the legal framework and promotes the adoption of HiAP across all levels of government and potentially also increasing its scope of the HiAP by legitimizing collaboration. In their study of Iran, Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al. (2016) found that legal endorsement and provisioning of programmes provided the much-needed push for ISA to move into the stages of agenda setting. A similar challenge was noted in the Philippines, where a Whole-of-Government approach was adopted for Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs), especially tobacco. The study noted that weaker legislation and the presence of the tobacco industry proved to be key challenges for Department of Health to be compliant to Framework Convention of Tobacco Control (Lencucha et al., 2015).

However, it is not only the lack of legislation but also the lack of legislative integration can create more ambiguity and further cause severe implementation challenges and hamper accountability. Using the example of extreme climate-related weather events in Australia, Howes et al. (2015) explain that individual agencies often have separate legislations, and in cases of natural disaster, new legislation leads to ever more fragmented policies, plans and goals among agencies. They highlight that either reviewing and amending previous legislation, or creation of a new omnibus act could bring in much needed legislative integration to support on the ground activities and lead to e a clearer chain of accountability.

Social accountability

Social accountability is also an important mechanism to ensure public service delivery, not only towards government but also potentially towards non-state service providers. The UN-REDD+ initiatives include a group of non-state actors, comprising of NGOs, civil societies, indigenous groups, local community and private sector, under stakeholder groups, as it is important that these initiatives are anchored in local communities. The need to build participatory governance mechanisms for indigenous and forest-dependent communities also stems from the fact that they are guardians of the forest land and it is essential to safeguard the rights of communities (Fujisaki et al., 2016). However, the environmental studies literature also cautions about tokenism as participation in decision-making is by no means a guarantee for their views to be taken into consideration. In health, there are some positive examples, for example in Cuba, where the implementation of ISA at municipal level was aided by co-location and embeddedness in the local and political context, thus providing ‘connectedness’ to people and at the same time, the inclusion of community representatives in local health councils provided local social accountability, by allowing for broader public participation for raising concerns or complaints (Spiegel et al., 2012). Thus, ISA can also act as a mechanism for ensuring long-term social accountability and relevance.

With the growth of information and communication technologies, media can be a powerful tool in promoting transparency, and be a key driver of accountability (Camaj, 2013) . In the case of Danish municipalities, Larsen et al. (2014b) show that share that local media was a positive facilitator for ISA in health, as it disseminated critical and complex information on policy, and identified the role of key actors to citizens. In Dutch municipalities, media channels were used to frame alcohol abuse as a complex social intersectoral problem, rather than just a health problem, thus influencing both political prioritization and processes for agenda-setting. Media can also be used as a regulatory and enforcement strategy, in influencing public opinion to promote accountability, in framing of the problem, and in providing an external oversight as a forum for debate for a plurality of actors (Goeij et al., 2017).

Discussion

This meta-narrative-review examines the literature exploring the concept of ISA across different knowledge domains, sharing the theories, theoretical framing and empirical application of ISA in other fields that can help better situate and inform health policy and systems research. We also share the roots of origin of ISA and motivations to pursue ISA in these research domains.

The review reveals that research on structural mechanisms for coordination across sectors (e.g. committees, task forces and coordinating units) is often skewed towards engagement of the public sector. The importance of the participation of communities and NGOs has been deemed important across all four research domains, but the mechanisms to engage and ways to empower their participation has oftentimes been limited. This also points towards the need to consider such participation in ISA, taking into account issues of power, interests and control. Interactions between and across do not occur only in the context of a single underlying policy/programme but are also governed by broader political factors, dynamics between actors from civil society, the market and state, as well as trust in government which forms the background and context against which ISA is implemented.

In the Health sector, the concept of HiAP has been promoted to make the policies and adopt policies in a systematic way. Australia, Brazil, Cuba, England, Finland, Iran, Malaysia, New Zealand, Northern Ireland, Norway, Quebec, Scotland, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Thailand and Wales have adopted HiAP approaches at national or sub-national jurisdictions. These examples, however, also share a more ad hoc adoption of HiAP through projects or programmes, instead of a systematic adoption (Shankardass et al., 2011). This also raises the questions regarding the overall success and sustainability of intersectoral initiatives. Holt (2017) opine that framing of health-goals into the agendas of other sector promotes the adoption of ‘small-scale interventions’ and might address only the ‘intermediate determinants’ and discount broader welfare policy impacts. However, following Holt, ISA needs to address the ‘causes-of-causes’, such as macro socio-economic and macro-economic impact, or else, it can impede the longer-term success and sustainability of ISA (Holt et al., 2017).

Thus, different frames lead to differences in mobilization, mandates, operationalization and solutions in ISA. In health, the case of the ‘commercial determinants of health’(Kickbusch et al., 2016) and the rising NCD epidemic bring/has brought the tension between global/trade policy and health to the fore, where public policy actors are constrained in their action by a lack the resources, power and capacity to promote the ideas and values of public health (Labonté and Stuckler, 2016; Schram, 2018).

In the design and implementation of inter-sectoral interventions, the role of power and politics is considerable, and it is common for traditional command and control forms of power to be upheld by statutory institutions. The process of coordination and regulation may lie outside the authority of the health ministry and may be in the hands of the ministries of finance, industry, or agriculture, who are also more powerful, having profound effects on public accountability (WHO, 2017; Lencucha and Thow, 2020). However, it is also important to note that traditional hierarchies are challenged during the process of implementation as such bureaucracies are often ill-equipped to work across institutions/across boundaries. Ostrom (2005), in describing an institutional design for ‘nesting’, evokes a scenario for ISA with several centres of decision-making (polycentrism), with each centre/institution retaining its independence, and where decision-making overlaps and cuts across different jurisdictions.

To promote joint-decision-making and to be able to resolve conflicts, informal aspects of organizational culture, social capital, and networks can play a crucial role. The role of leadership in enabling coordination, building trust and with an ability to navigate complex communication, has been considered essential. These leaders are sometimes described as being ‘linking pin’ or a ‘boundary spanner’. In the arena of global health, the concept of boundary spanner has been suggested important to promote an inclusive mindset. Crossing boundaries need, a constant engagement and comparisons across contexts, working across silos of research, practice and policymaking and finally integrating local, sub-national, national and global learning to promote learning (Sheikh et al., 2016).

The cross-sectoral collaboration for better health has gained a renewed impetus is the SDG era.

The recent series on ‘Making Multisectoral Collaboration Work’ in the British Medical Journal shares 12 country case studies that reveal news ways of collaboration and learning (Graham et al., 2018A); while the BMJ’s Global Health series on ‘Governing multisectoral action for health in LMIC countries’ (Bennett et al., 2018), shows the need to generate evidence to reach these goals. Our review directly contributes towards enumerating and detailing on theories and their application in this discussion, by being better able to understand the processes and complex undercurrents involved.

To frame and conceptualize ISA in terms of governance challenges, with the given degree of complexity, a ‘hybrid’, adaptive form of governance seems to be appropriate, which can be adapted depending on the institutional arrangements and context. The concept of meta-governance (Torfing et al., 2012) proves to be quite apt, due to the changing role of the health sector and the interaction with the multiple actors embedded in power differences. The health sector can enact the most appropriate role of a technical resource, implementor, regulator, coordinator or enabler, in an integrative form of governance, balancing the other sector requirements and needs. These functions can be translated into more specific roles, responsibilities and related accountability processes. A single form of accountability mechanism, may not be sufficient, and may need a mix of administrative, legal and social forms of accountability might be required, adapted to deliberately shared roles by civil society organizations and markets.

Strengths and limitations

The meta-narrative synthesis was the most appropriate methodology for a theoretical and empirical synthesis across disciplines. As a consequence, we did not include articles using only strength of evidence, which is characteristic of a systematic review. However, to maintain the quality of cases, we included only peer-reviewed articles in the study. Moreover, this decision was also influenced by the nature of the review, which set out to also include conceptual studies, and in such cases strength of evidence classifications would have not been appropriate.

Another limitation of this study is the restriction of our searches and analysis to four disciplines. As explained earlier, the choice of political science and public administration was based on the fact that much of the theoretical development on ISA stems from these research traditions, whereas health and environmental domains were chosen for their empirical advances. We acknowledge that there are other research domains which use similar concepts of ISA in conceptualization and implementation, such as organizational sociology and management studies.

Our entry-point was a mapping of concepts used in health which are also used in the other research domains, which may have produced restrictive searches. This also led to inclusion of more research articles from health and the possibility that not all relevant publications were included across the other three research domains. Through cherry-picking and exploring seminal works in each domain, we made the review more comprehensive. Thus, this review is a starting point for further integration of ISA between environment, health and political science, needed to tackle SDG challenges, and not exhaustive of concepts and theories that have been explored in the research domains.

Research and policy practice implications

Our review identifies challenges and opportunities to work on ISA and advances the theory knowledge and theoretical grounding of ISA across research domain that can be used in health and its more in depth understanding of specificities and similarities between health and other sectors. In health, there has been a gap in research methodologies that can capture or measure ISA, and this review addresses this by identifying the application of newer methodologies in form of ethnographic studies detailing on context and processes (Holt et al., 2017), realist methodology to draw the relation between context-mechanism-outcomes (Shankardass et al., 2014), theory-based logic models for complex evaluations (Baum et al., 2014), thus paving a way for future research.