Abstract

South Africa has a long history of community health workers (CHWs). It has been a journey that has required balancing constrained resources and competing priorities. CHWs form a bridge between communities and healthcare service provision within health facilities and act as the cornerstone of South Africa’s Ward-Based Primary Healthcare Outreach Teams. This study aimed to document the CHW policy implementation landscape across six provinces in South Africa and explore the reasons for local adaptation of CHW models and to identify potential barriers and facilitators to implementation of the revised framework to help guide and inform future planning. We conducted a qualitative study among a sample of Department of Health Managers at the National, Provincial and District level, healthcare providers, implementing partners [including non-governmental organizations (NGOs) who worked with CHWs] and CHWs themselves. Data were collected between April 2018 and December 2018. We conducted 65 in-depth interviews (IDIs) with healthcare providers, managers and experts familiar with CHW work and nine focus group discussions (FGDs) with 101 CHWs. We present (i) current models of CHW policy implementation across South Africa, (ii) facilitators, (iii) barriers to CHW programme implementation and (iv) respondents’ recommendations on how the CHW programme can be improved. We chronicled the differences in NGO involvement, the common facilitators of purpose and passion in the CHWs’ work and the multitude of barriers and resource limitations CHWs must work under. We found that models of implementation vary greatly and that adaptability is an important aspect of successful implementation under resource constraints. Our findings largely aligned to existing research but included an evaluation of districts/provinces that had not previously been explored together. CHWs continue to promote health and link their communities to healthcare facilities, in spite of lack of permanent employment, limited resources, such as uniforms, and low wages.

Keywords: Community health workers, implementation science, qualitative research, primary health care

Key Messages.

South Africa’s community health worker (CHW) programme has been a vital part of healthcare service delivery in South Africa for decades. The programme has existing variation in models of implementation but is guided by a strong national framework since 2011, recently revised in 2018.

Despite the programme’s long history, there are still many challenges to optimal implementation, including limited resources, incomplete staff complements, inconsistent use of data, safety concerns and few pathways for professional development.

South Africa’s National Health Insurance, among other objects, seeks to ensure Universal Health Coverage and optimal implementation of the CHW programme is an important part of that policy and towards improving the quality of primary health care in South Africa.

Introduction

South Africa has a long history of community health workers (CHWs) dating back as early as the 1930s (MacKinnon, 2001). It has also been a complex journey, balancing constrained resources and competing priorities (Clarke et al., 2008). The 2004 National Department of Health’s (NDoH) CHW policy allowed for both generalist (care across the spectrum of health needs) and single-disease CHW functionality, focusing only on HIV. e.g. (Friedman, 2005). An increasing burden of HIV and tuberculosis between the 1990s and early 2000s resulted in the proliferation of CHWs being recruited and trained (Friedman, 2005; Schneider et al., 2016). Guided by the primary healthcare approach in Brazil, South Africa’s NDoH has prioritized re-engineering the primary healthcare (PHC) system since 2011 (National Department of Health of South Africa, 2011). CHWs, supported by other health professionals, form a bridge between communities and healthcare service provision within health facilities and act as the cornerstone of the national Ward-Based Primary Healthcare Outreach Teams (WBPHCOT1) programme (MacKinnon, 2001; SA NDoH, 2018a). From a policy perspective, the model has now long embraced the generalist approach, described as ‘integrated services’ by the NDoH 2011/12 and 2018/19 policies (Jinabhai et al., 2015).

There is ample evidence to show that CHWs can help in improving attitudes towards family planning, increased breastfeeding and immunization of children under five years, as well as tracing of patients on ART and other aspects of healthcare provision, particularly among those in rural and underserved areas (Geng et al., 2016; Naidoo et al., 2018). Under the current Policy Framework and Strategy for WBPHCOT 2018/19–2023/24, CHWs have a broad scope of work that supports various health programmes including: (i) health promotion and illness prevention; (ii) registering health needs at the household level; (iii) providing psychosocial support; (iv) management of minor health issues; (v) coordination with other health providers; (vi) providing adherence support and counselling for chronic conditions; and (vii) tracing of patients who have missed HIV and TB service visits or who need referring back to the clinic (SA NDoH, 2018b). Swartz (2013) and Jinabhai et al. (2015), acknowledge the substantial variability within small pockets of the country and across provinces in CHW service delivery (Swartz, 2013; Jinabhai et al., 2015). To date, ∼70 000 lay health workers (a broader category which CHWs fall within) have been recruited and deployed across communities in South Africa and have helped to address the vast shortfall in human resources for health in South Africa (Schneider et al., 2018). However, there are still only half the WBPHCOTs needed to cover all 4277 wards across the country (Schneider et al., 2018).

Because of the various models of implementation that exist across South Africa, the limited documentation of implementation countrywide and the persistent barriers that CHWs face, detailing CHW policy implementation across the different provinces is of critical importance. This is important as it may inform the NDoH about what is working and what is not working within the policy and help inform future revisions and implementation. A rapid appraisal was conducted by Jinabhai et al. (2015) to assess WBPHCOTs; however, their report only focused on the National Health Insurance (NHI) pilot districts (Jinabhai et al., 2015). This study aimed to document the CHW policy implementation landscape across six provinces in South Africa, to identify potential barriers and facilitators of the current policy to help guide and inform future planning.

Methods

Study design and population

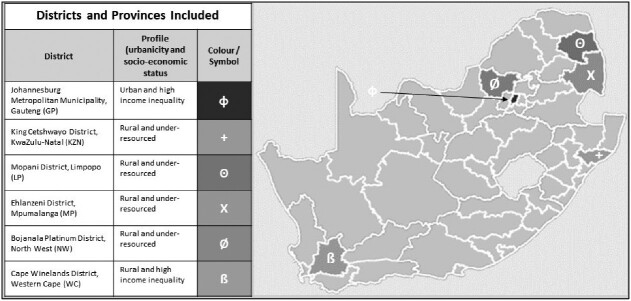

We conducted 65 in-depth interviews (IDIs) with a purposively selected sample of Department of Health (DoH) National, Provincial and District level managers, healthcare providers and implementing partners2 (who worked with CHWs) from a single district in Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal, Limpopo, Mpumalanga, North West and Western Cape provinces. Eligible districts were those not included in Jinabhai et al.’s (2015) work and otherwise a convenient sample to collect a variety of urban, peri-urban and rural districts based on existing relationships and familiarity with the study sites/communities. We also conducted nine focus group discussions (FGDs) with CHWs themselves. Figure 1 is a map of where the research took place.

Figure 1.

Map of South Africa and six districts/provinces included in the study

IDIs with experts—sample selection

We followed a top-down non-random convenience sampling approach to data collection starting with IDIs with national and provincial experts. These participants then suggested managers and providers at the district level (including implementing partners) who could be approached to participate and they in turn suggested participants at facility level [e.g. including facility managers, data capturers, outreach team leaders (OTLs) and/or CHWs] who would have valuable perspectives to offer (Bhattacherjee, 2012). Table 1 outlines the expected and actual number of respondents at each level and also includes illustrative titles, description of roles and level or areas of oversight. Respondents were eligible to be interviewed if they were employed in a relevant position, had prior experience and/or policy awareness with CHWs, were 18 years of age and older, agreed to participate and provided written informed consent.

Table 1.

Description of interview respondent: types, targets/reached, geographic coverage and description of roles

| Type of respondent | Illustrative titles | DoH or NGO? | Reached/target | Geographic coverage by level of the health system | Description of roles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National stakeholder | Technical advisor | Both | 3/10 | Covered through engagement with national stakeholders | Advising provincial, district, facility and community leaders on how to implement WBPHCOT policy |

| Provincial management | HAST Director, Deputy Director Community Health Worker Programme, Deputy Director Primary Healthcare | DoH | 16/18 | Engaged with 6 of 9 provinces | Asset management, leadership, human resource management, training coordination, financial compliance, governance and support healthcare service delivery |

| District management | WBOT manager, District Director Primary Healthcare | DoH | 11/24 | Engaged with 6 districts out South Africa’s 52 total districts | Sub-district PHC manager |

| Implementing partner | PHC Re-engineering Technical Advisor | NGO | 6/6 | All but KZN and NW provinces | Support of implementation at provincial, district, facility and community levels |

| Facility based | Facility Manager, Data Capturer | DoH | 13/15 | We did not have a facility representative in GP | Management and operations of PHC at the facility level |

| OTL | OTL, professional nurse, enrolled nurse, CCG supervisor, CCG facilitator | DoH | 13/15 | Representation from all 6 selected districts | Clinical care, administration, documentation, reporting and training. As an example, professional nurses can support basic midwifery while enrolled nurses must refer and seek advanced support |

| CHWs | CHW, CCG (historical title in KZN), CCW (historical title in WC)a | Both | 4/6 | CHWs were only included in interviews in GP, KZN and NW provinces | (1) Promote health and prevent illness at households, (2) register health needs, (3) provide psychosocial support, (4) identify and manage minor health problems, (5) support the continuum of care and (6) provide adherence support for chronic conditions |

| Total | Various | Both | 65/94 | National and 6 of 9 total provinces covered | Various |

CHW, COmmunity Health Worker, CCG, Community Care Giver; CCW, Community Care Worker; GP, Gauteng; HAST, HIV/AIDS, STIs and Tuberculosis, KZN, KwaZulu-Natal; NGO, Non-governmental Organisation; OTL, Outreach Team Leader; PHC, Primary Healthcare; NW, North West; WBOT, ward-based outreach team; WBPCHOT, Ward-Based Primary Healthcare Outreach Team; WC, Western Cape.

Largely these roles are being phased out in favour of CHW across the country.

FGD with CHWs—sample selection

Focus group participants were also identified through a process of non-random convenience sampling. District and facility respondents included in the IDIs helped us to identify eligible CHWs and invite them to the FGDs. As planned, we conducted two FGDs per district, one at a high-performing facility and one at a low-performing facility (determined based on district managers subjective experience). Targets and reach of CHW FGDs are in Table 2. All our FGDs comprised CHWs belonging to at least two different facilities or two different WBPHCOTs. CHWs identifying as home-based caregivers (HBCGs), peer educators, community caregivers (CCGs) in KwaZulu-Natal and community-care workers (CCW) in the Western Cape (Friedman, 2005; Stellenberg et al., 2015) were considered eligible to participate in the FGDs if they were 18 years of age and older, agreed to participate and provided written informed consent.

Table 2.

Description of focus group respondents: targets/reached and languages present

| District, province | Number of FGDs reached/targeted | Number of participants | Number of teams | Number of facilities included | First languages present |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Johannesburg, Gauteng | 2/2 | 24 | 4 | 4 | Setswana, isiZulu, Sepedi, Sesotho, isiXhosa and Tshivenda |

| King Cetshwayo, KwaZul-Natal | 2/2 | 23 | 4 | 4 | isiZulu |

| Mopani, Limpopo | 1/2 | 11 | 2 | 2 | Xitsonga and Tshivenda |

| Ehlanzeni, Mpumalanga | 1/2 | 8 | 2 | 2 | SiSwati |

| Bojanala, North West | 2/2 | 20 | 4 | 4 | Setswana |

| Cape Winelands, Western Cape | 1/2 | 9 | 3 | 3 | Afrikaans, English and isiXhosa |

| Total | 9/12 | 101 | 19 | 19 | 10/11 official South African languages |

Data collection and instrumentation

Data were collected between April 2018 and December 2018. IDIs were conducted using separate interview guides for (i) provincial and national expert IDIs and (ii) district, facility and CHW IDIs. A further guide was developed to facilitate the FGDs. The guides were developed with input from experts: those in our organization as well as experts from the University of Pretoria and University of the Western Cape. The topics of each guide are summarized in a web annex (Supplementary Data S1). IDIs were carried out in English, but FGDs were conducted in the local language chosen by the CHWs. All interviews and FGDs were recorded for quality, transcription and translation purposes. The interviewers and note-takers also recorded their interview/FGD notes and reflections for each data collection event. Participants provided written informed consent to confirm that they had been informed about the study and were willing to be recorded. The IDIs lasted 30–60 min and the FGDs between 60 and 120 min. Interviews with national, provincial and select district respondents were conducted over the phone while FGDs and facility interviews were conducted in an office or boardroom at the healthcare facility.

Data management and analysis

All FGDs and all but one IDI were audio-recorded and transcribed, and the single IDI was included in the analysis as ‘expanded notes’ because the respondent declined to be recorded (Tolley et al., 2016). Interviews were transcribed verbatim while FGDs were simultaneously translated during the transcription process into expanded notes, i.e. not always verbatim, but included direct quotes as judged by the FGD facilitator (Oliver et al., 2005; Tolley et al., 2016). Transcripts were then imported into NVivo 11© (Doncaster, Australia), coded line by line and analysed using a content analysis approach (Richards, 2014).

We considered theoretical frameworks (Damschroder et al., 2009; Naimoli et al., 2014) as well as results from other South African reports and sections from the policy document to guide the creation of our codebook and analysis (Jinabhai et al., 2015; SA NDoH, 2018a). The deductive portion was guided by the most recent comprehensive reviews of WBPHCOTs (Jinabhai et al., 2015) and the policy itself (SA NDoH, 2018b), which led to the creation of codes (e.g. policy, services, implementation, training and management; codebook: Supplementary Data S2). Additional codes were added as themes emerged (as per the inductive process). To minimize researcher bias, we coded the first transcript as a group of five, thereafter two researchers coded least two additional transcripts each and inter-coder agreement was assessed using a Kappa coefficient. Coding was refined until agreement among coders reached good correlation (>0.5).

We present sample characteristics of IDI and FGD respondents and then our results within four primary areas: (i) current models of CHW policy implementation across South Africa; (ii) facilitators to CHW programme implementation; (iii) barriers to CHW programme implementation; and (iv) recommendations. Again, we split the facilitators and barriers into those that influenced policy implementation and those that directly influenced CHWs.

Results

Sample characteristics

We conducted IDIs with 65 stakeholders (Table 1). Of those interviewed, 82% were female. The median years in the position was 4.5 (range: 0.3–27.5) and the median years with their organization was 9.2 (range: 0.3–31.5). The FGD respondents (101 from 9 FGDs) were predominantly female (95%), they had worked a median of 4.7 years (range: 0.7–15.7) as a CHW, their median age was 43 years (range: 24–60 years) and 52% had completed secondary school (grade 12) (Table 3). Similarities and differences in CHW characteristics were observed across different provinces (Tables 2 and 3). Full FGD sample size was not reached in two provinces where only one FGD was conducted; data saturation that occurred within provinces suggests that the impact of only one FGD in those cases on a full data picture was minor.

Table 3.

FGD demographics

| Province: district | Median years as CHW (range) | Median age years (range) | Completed secondary school (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Johannesburg, Gauteng | 2.7 (1.8–4.7) | 37 (26–54) | 67 |

| King Cetshwayo, KwaZulu-Natal | 7.7 (0.7–13.7) | 43 (24–57) | 48 |

| Mopani, Limpopo | 4.7 (3.7–15.7) | 47 (35–45) | 82 |

| Ehlanzeni, Mpumalanga | 6.7 (3.7–6.7) | 42 (35–45) | 63 |

| Bojanala, North West | 6.7 (4.4–7.7) | 47 (24–60) | 30 |

| Cape Winelands, Western Cape | 2.7 (1.7–13.7) | 43 (26–57) | 40 |

| Total | 4.7 (0.7–15.7) | 43 (24–60) | 52 |

Current models of CHW policy implementation and characteristics of CHWs across South Africa

Most national, provincial and district level respondents were aware of the new framework and the details. Most participants discussed the transition from HBCGs, where CHWs were employed by local non-governmental or community-based organizations (NGOs or CBOs), to the DoH. Community-oriented Primary Care (COPC) was described as one approach to implementing the WBPHCOT programme. This approach involves supporting communities holistically and differs from the PHC Re-engineering approach, which focuses more on facility-based outcomes. One district manager described COPC saying that WBPHCOT is the name of the programme and COPC is the methodology you use to implement WBPHCOT. COPC was mentioned as a more resource intensive model of implementation occurring in Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal and the Western Cape. While some respondents pointed out differences between COPC and PHC Re-engineering, others described them as the same (Table 4: Quotes A and B).

Table 4.

Key quotes from all respondent types concerning the key thematic areas

| Letter | Respondent type, province and ID | Thematic area/summary statement | Quote |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. | Provincial manager, KwaZulu-Natal, SS-14 | Current models of CHW implementation—COPC/multi-sectoral approach is key | [Collaboration] that's the strongest part of primary healthcare because it then tells you you've got to work with the community, everyone in the community. You've got to work with other sectors because health alone cannot do it. |

| B. | Provincial manager, Western Cape, SS-15 | Current models of CHW implementation—COPC/COPC has advantages of PHC Re-engineering | The Community Oriented Primary Care I think blows the boundaries between what happens at the Facility and what happens in the community far more than the current system which is pretty rigid |

| C. | CHW, Gauteng, FG-04 | Facilitators to CHW programme implementation—policy implementation | We are a team of 8 and we rotate, currently we have 1, we start at the facility then do household visits. If it’s a follow-up, we check the road to health chart and check if the child has been taken to immunization (vitamins and deworming) if the kids at the household do not go to school we do give them the vitamins. When we do registration, we register and do screening and we ask if there is no one who is pregnant and we ask if they do routine check-ups of breast cancer and educate men about circumcision and HIV, HPT and DM Educate on TB, cancer, demonstrate how to screen for breast cancer |

| D. | CHW, North West, FG-01 | Facilitators that influence CHWs’ work in the community/OTLs can be supportive | My OTL accompanied me to the house and we checked a patient’s medication and pills. |

| E. | CHW, KwaZulu-Natal, FG-09 | Facilitators that influence CHWs’ work in the community/passion and purpose | We became CHWs to ensure our community gets assistance. |

| F. | Implementing partner, Limpopo, KI-01 | Facilitators that influence CHWs’ work in the community/CHWs can respond quickly in their communities | It is helping because they are actually within the communities, it's easy for them to respond quickly to their patients when there is crisis because they are within communities. |

| G. | CHW, Gauteng, FG-03 | Facilitators that influence CHWs’ work in the community/CHWs can have a positive impact on behaviour change in their communities around early booking | We go outside to help the community. When I started there were a lot of defaulters, a lot of pregnant women didn’t understand the importance of booking early so we educate them. |

| H. | Provincial manager, Limpopo, SS-06 | Facilitators that influence CHWs’ work in the community/recognition by management and stakeholders | working very well with the Team Leaders (OTL) with the traditional healers together with the churches, we are able to communicate they are giving us access to each and every corner. |

| I. | District manager, North West, KI-04 | Facilitators that influence CHWs’ work in the community/facility integration and recognition (district manager, North West) | If the facility manager knows about [it], then we can work. |

| J. | Provincial manager, Limpopo, SS-09 | Barriers of policy implementation/clarity on elements of the policy framework | I wish the policy was just straight forward and says [completion of high school education]. |

| K. | Implementing partner, Limpopo, KI-01 | Barriers of policy implementation/incomplete staffing coverage | …when we started the whole programme of PHC re-engineering, it was supposed to have community health workers, team leaders, which is a professional nurse, and it should have a health promoter. But the problem is all those people, not every facility has those people in it. |

| L. | Provincial manager, Limpopo, SS-09 | Barriers of policy implementation/incomplete staffing coverage | We just don't have enrolled nurses nor the budget to employ them. OTLs are part time. |

| M. | District manager, Mpumalanga, KI-24 | Barriers of policy implementation/‘Catch-22 enrolled nurses compared to professional nurses’ | It’s a catch twenty-two situation … The country is having a shortage of professional nurses. We are having a challenge to say we don’t have that number of enrolled nurses that … can take over their role of the professional nurses. And on the other hand this scope of the enrolled nurses and the scope of the professional nurse is not the same…When there are things that are above this scope of that enrolled nurse, that nurse still needs to refer the client back to the Facility. |

| N. | CHW, Limpopo, FG-06 | Barriers of policy implementation/limited resources | Actually, we don’t have forms. We don’t have stationery. The only stationery we have, they only gave us one book. The book that I’m talking about is like this one, for us to write on it wherever we go. Then the stationery that we have is just for writing a report month end |

| O. | CHW, Gauteng, FG-04 | I had to trace multi-drug resistant TB patient with no mask. | |

| P. | CHW, North West, FG-01 | Barriers of policy implementation/limited resources | … we don’t have uniform and when you do household visit they give you a funny look and ask where are you from, this gives us a problem because they don’t trust us because we cannot be clearly identified as the CHW from DoH because of not having uniform and we cannot buy for ourselves as it’s too expensive. |

| Q. | CHW, North West, FG-01 | Barriers of policy implementation/limited resources | When you do household visits, they give you a funny look and ask where are you from?’ This gives us a problem because they don’t trust us because we cannot be clearly identified as a CHW from DoH. |

| R. | Implementing partner, Gauteng, KI-13 | Barriers that influence CHWs’ work in the facility/limited recognition and respect | Generally, there is no synergy between community work and facility. It comes back to buy-in of the facility. The facility managers refuse to take responsibility of OTLs and CHWs |

| S. | Provincial manager, Gauteng, SS-11 | Barriers that influence CHWs’ work in the facility/conflicting roles and remuneration | [The] Department had already resolved that NGOs did not work because of financial mismanagement. |

| T. | District management, Gauteng, KI-14 | Barriers/data—repeat of household registration data collection | It's going well, but as I said, they started to do household registration in 2012. We wanted now to recall all those forms to start profiling of the wards, and the information is missing because the forms are nowhere to be found… We're starting all over. |

| U. | CHW, KwaZulu-Natal, FG-09 | Barriers/data and tracing—wrong addresses | Let’s say I was given a task to trace 10 defaulters, I often find one. the others I don’t get them due to wrong addresses, we don’t find a lot of people because of wrong addresses and wrong phone numbers. |

| V. | Professional nurse, unidentified province, KI-35 | Barriers/tracing | I want to give you an honest answer, they just go, they don’t have a list. |

| W. | OTL, North West, KI-06 | Barriers/tracing | Some of them come in … and default when they get better. And because they are afraid of coming back here, they say those nurses are going to be [upset], they automatically start afresh [somewhere else]. |

| X. | Implementing partner, Gauteng, KI-13 | Recommendations/addressing qualifications and training | I still feel that the selection criteria [of CHWs] was done wrong in terms of basic qualification, like matric, because there are some who cannot read and write and also there are some who do not really comprehend what we are training them on. But I still feel that there should be continuous training for CHWs at all points. |

| Y. | Provincial management, Western Cape, SS-16 | Recommendations/policy integration | [Community-based Services7] should be integrated as parts of Primary Health Care. And that’s what [the Healthcare 2030] document also says. It says it’s a linkage between Community Base Service, Primary Health Care and Intermediate Care Facilities which is our step-downs. It’s a combination of those three platforms. And that’s one of the reasons that we are doing away with it as a directorate. |

| Z. | Implementing partner, Gauteng, KI-13 | Recommendations/COPC principles and community indicators |

Ki_13: I would like to see facility indicators speaking to community indicators. I would like to see community work complementing facility work. Community work contributing towards … facility indicators and vice versa. There has to be that linkage, for example we sit down and look at the indicators at facility levels, how are you doing on early booking? How are you doing on your HIV initiations and ja. Let's say we are targeting 90 90 90 at facility level, how are you doing in terms of first 90, second 90, third 90? That then will inform the activities at community level. That's my wish, to say okay [unclear] are not doing it initiation, let's have this month or this quarter, our WBOTs are going to be having a campaign on educating people on- Interviewer: Now you're speaking COPC a little bit? Ki_13: That's exactly it. Then when you come back after three months we look, how are we doing, how are we doing? Those kind of things, so that they complement each other. That's my wish. But as of now I don't know, it's… Interviewer: Everything going everywhere? Ki_13: You see! |

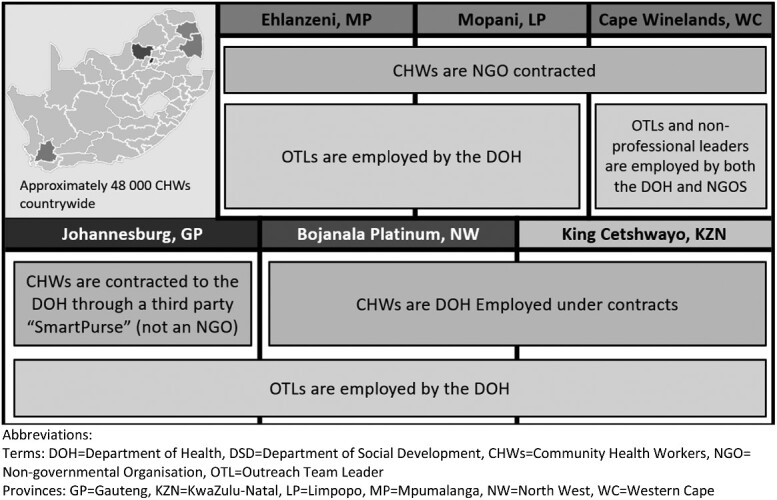

We observed both similarities and differences in implementation across the different provinces. The key elements, including information on NGO involvement, contractual and leadership structures, CHW working structure and working hours, are summarized in Figure 2 and Table 5.

Figure 2.

Structural differences in employment of CHWs and OTLs across six districts

Table 5.

Description of key elements of WBPHCOT policy implementation by district

| District, province | NGOs supervise | Leadership structuresa | Funding model structure | Employed by DoH? | Outreach team leadership | Report to facility daily (check-in and check-out) | Total hours per day; hours of operation | HH visit per day; total HHs responsible for | Travel in pairs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Johannesburg, Gauteng | No | DoH: Health Programmes, District Health Services |

Paid directly from DoH, but not on PERSAL—‘SmartPurse’ a third party EPWP provides some funding |

No | PNs and ENs, but more often ENs than any other district | Variable, some must finish their day back at the facility, while others shared evidence of ‘Health Posts’ where CHWs would check-in and out of a field office | 6 h; 8:00 am to 2:00 pm, 5 days per week | 2–3 HH visits per CHW; 250 HHs | Always |

| King Cetshwayo, KwaZulu-Natal | No | DoH: Special Projects, PHC Services as well as Department of Social Development | Led by Special Programmes and DoH for a smaller number of WBPHCOTs—all integrated into facility/district structures | Yes on PERSAL, 2-year contract |

CHWs report to CCG supervisors (ward-level) and supervisor’s report to CCG facilitators (sub-district level) There are also PN OTLs |

No, variable. In some cases, only once per week | 8 h; 8h00–16h00, 5 days per week | 4 in Urban area, 3 in rural areas; 60 HHs per month | Sometimes |

| Mopani, Limpopo | Yes | DoH: PHC and HAST directorate | Transitioned from over 300 NGO/NPOs to only 2 in 2018 | No | OTLs are PNs, but they are often supporting the WBPHCOT as a secondary role to their facility-based work | Yes, must clock-in in the morning, but depending on how far the CHW stays they do not have to return at the end of the day | 9 h; 7:00 am to 4:00 pm, some reported weekend work | Up to 10 visits; 250 HHs | Sometimes |

| Ehlanzeni, Mpumalanga | Yes | DoH: community-based services and PHC |

Funded by DoH and DSD, 114 NPOs funded by DoH EPWP provides some funding |

No | OTLs are more often PNs employed by the DoH, more often PNs supporting the CHWs. ENs are not available | Report to their CBO and the OTL liaises with the associated facility | 4 h; 8:00 am to noon (per their contract) | At least 4 follow-up HH visits, 2–5 non-vulnerable HHs (e.g. routine follow-up for someone on chronic medication); 250 HHs | Only if there are safety concern |

| Bojanala, North West | No | DoH: HAST and Healthcare Services and District Development |

Transitioned from NGOs to DoH-funding. CHWs do have PERSAL numbers EPWP does not provide funding for CHWs |

Yes, but not permanently | OTLs are more often PNs employed by the DoH | Yes, must clock-in in the morning, but not necessarily in the afternoon | 6 h; 8:00 am to 2:00 pm; some reported weekend work | 2–3 HH visits per CHW; 250 HHs | Variable, but prefer pairs |

| Cape Winelands, Western Cape | Yes | DoH: Community-based Programmes,b PHC | Maintaining NGO contracting—1 NGO per sub-district | No, despite calls to do so | OTLs are more often PNs employed by the DoH, more often PNs supporting the CHWs | Yes, clock-in and clock-out at the facility | 4.5 h; 7:30 am to noon | ± 4–6; 250 HHs | Always |

As reported in our interviews.

Community-based Programmes as a directorate is being phased out.

CBO, community-based organisation; CCG, community care giver; DSD, DoH, Department of Health; Department of Social Development; ENs, enrolled nurses; EPWP, expanded public works programme; HAST, HIV/AIDS, STIs and TB; HH, household; NGO, non-governmental organisation, NPOs, non-profit organizations; PERSAL, Personnel and Salaries management system; PNs, professional nurses; WBOT, Ward-based Outreach Team, WBPCHOT, Ward-Based Primary Healthcare Outreach Team.

For many CHWs that conduct household visits, checking in and out of the facility is standard practice. In Mpumalanga, e.g. CHWs begin their day from 7:00 am to 8:00 am supporting the health talks given by facility staff in the waiting areas before continuing with their required CHW duties. Conversely, some CHWs in North West and Limpopo start in the facility but finish their shift in their communities, while some CHWs in KwaZulu-Natal may only visit their facility once per week. The tools used were consistent across districts with frequent descriptions of (i) household registration form, (ii) individual form for anyone with chronic illness, (iii) maternal and child record, (iv) referral/back referral form, (v) household visit tick sheet, (vi) individual CHW monthly summary and (vii) team monthly summary form. The household visit tick form was sometimes used to plan the week ahead and served as a checklist for the number of household follow-up visits per week. Most teams conducted community work from Mondays to Thursdays with Fridays dedicated to in-service training or compiling and submitting reports. The in-service training was most consistently mentioned in Gauteng and North West province. The teams in KwaZulu-Natal and Western Cape did not mention participating in trainings on Fridays. The number of household visits ranged from two household visits per CHW per day in Gauteng to 10 per CHW per day in Limpopo. Large variations in hours of operation and levels of management were observed across different provinces.

Facilitators to CHW programme implementation

Overall participants in the IDIs and FGDs identified fewer facilitators to WBPHCOT implementation than barriers, but nevertheless facilitators were present.

Facilitators to policy implementation

Consistent health priorities

Strong consistent messages on health priorities were seen as a key facilitator for CHWs (e.g. in the Western Cape the focus on the ‘first one thousand days’ of children’s lives). Across models of implementation, districts and respondents, the health priorities that CHWs focused on were consistent. According to our respondents, TB, health issues of children under-5-year old, maternal health and HIV/AIDS remain their main health priorities. Social services and support of non-communicable diseases, such as hypertension and diabetes, also form part of the priorities of the WBPHCOT programme. Many CHWs felt that they understood the services they administer and their daily routines; there was an overall sense of clarity in their roles and responsibilities (Quote C).

OTLs

OTLs are a key facilitator to the implementation of WBPHCOT. Supervision and guidance from OTLs were common and viewed as being hands-on and supportive. Telephone advice and general support was also noted as being a key part of OTL management strategies (Quote D).

Tracing resources and adaptation

Across facilities we noted individualized solutions to facilitate planning and improve tracing of patients who missed a visit for HIV or TB services. When we did encounter office space (it was infrequent), there was evidence that OTLs and CHWs have created hand-drawn maps of the areas where CHWs and WBPHCOT have been assigned. These maps facilitated overall planning.

In KwaZulu-Natal, we observed some novel solutions to the defaulter tracing process: (i) each patient was assigned to a CHW at registration at the facility to establish relationship with the patient to assist with tracing in the future if needed and (ii) each CHW is assigned a pigeon box, or designated area in the facility, where details of patients assigned to the CHW for tracing can be conveniently found.

Facilitators that influence CHWs’ work in the community

Purpose and passion

A sense of purpose, passion for the work, trust from the community and a feeling that as CHWs, they were making a difference were common facilitators reported across respondents (Quote E).

Close proximity to the community

CHWs reported their deep knowledge of their client’s culture (most were from the communities they serve) as a key facilitator in being able to implement their work. CHWs reported that this enhances CHW–client communication and cooperation, helps build awareness of the services that CHWs offer and also fosters trust among the communities that CHWs are serving (Quotes F and G). Similarly, some provincial representatives indicated that when CHWs engaged with the community, then their tracing was more effective (Quote H).

Participants also mentioned ‘Health Posts’. A ‘Health Post’ is usually a physical office outside of the facility but within the community. Although evidence about these was limited, the respondents indicated that proximity to the community was an advantage in delivering CHW services and provided an opportunity to deliver outreach work more effectively.

Facility integration and recognition

A strong and supportive relationship with facility management, through knowledge and integration of community-based care and facility-based clinical services, was reported as an indication to success in CHWs’ work (Quote I).

Barriers to CHW programme implementation

Critical barriers emerged frequently across all participant responses. Below we report challenges around: awareness of the new policy, deficits on staff complement and coverage, concerns around OTL and integration with the facility, inadequate wage, resources, data collection/use and tracing challenges.

Barriers to policy implementation

Clarity on elements of the policy framework

Largely, respondents seemed to have a clear understanding of the points included in the framework and what should be implemented; however, this was less apparent at the facility and community level. Some respondents did raise issues of clarity in the framework, e.g. in relation to the required qualifications of CHWs (Quote J).

Limitations of staff complement

One of the more common challenges mentioned was allocation of a full staff complement in terms of coverage of all wards and ensuring that there are sufficient CHWs to cover each ward (Quote K). There was little evidence to show that CHWs were allocated appropriately with consideration of the size of the catchment area. As an example, in rural Mpumalanga, one OTL described that she had a catchment area of >10 000 individuals that was served by five CHWs (the policy states each WBPHCOT of between 6 and 10 CHWs should serve ∼6000 individuals). We did encounter reports that resources are directed towards those areas of greatest need, guided by socio-economic status and other social determinants of health.

Limited OTLs

While a key facilitator to implementation of WBPHCOT are OTLs themselves, we found that OTL availability, regardless of qualification (professional nurse or enrolled nurse3), was a problem countrywide, but most acute in Limpopo where OTLs were most limited and were often facility-based professional nurses who served as OTLs as secondary roles (Quote L).

The limitations of OTLs were a major concern across respondents. The preference for the qualification of the OTL varied across provinces. Some believed it could be either an enrolled or professional nurse whereas others felt it could only be a professional nurse (Quote M). Quote M from a district manager in Mpumalanga describes a difficult ‘Catch-22’ situation where there is a shortage of profession nurse and her belief that enrolled nurses are not adequately suited for the role. It was only Gauteng that had a presence of enrolled nurses serving as OTLs and did not mention a shortage of this cadre of staff.

Wage, professional development and limited resources

There was consistent disappointment with the low wage, lack of permanent employment and limited opportunities for professional development. We also asked the CHWs and OTLs if they are provided with required and necessary equipment and supplies, such as sphygmomanometers, educational tools, first-aid kits (dressings, paracetamol, etc.), masks, uniforms, name tags and stationary. None of the CHWs or OTLs interviewed reported that they had all the equipment they needed. Stationery was often in short supply with CHWs often having to use their own money to make copies of necessary forms or buy their own stationery (Quote N). Essential equipment like TB masks was in many cases not provided, putting the CHWs at the risk of infection while interacting with their TB patients.

The most common missing resource was uniforms (Quote P), which participants indicated were key to their work, especially in terms of being trusted and taken seriously (Quote Q).

Barriers that influence CHWs’ work in the facility

Limited respect

Many CHWs do not always feel respected and integrated into the facility (Quote R) and their job specifications are misunderstood by other staff members. At worst there is mistrust between facility staff and the CHWs with lower lay cadre staff members feeling as though CHWs are being used to replace them.

Conflicting roles and remuneration

The presence of an NGO was sometimes a barrier to CHWs working with facility staff as this created confusion about work roles, while at other times a lack of communication between CHWs and the facility was a symptom of a system transitioning from NGO supervised to DoH/facility supervised. Community-based organization or NGOs who have historically managed and employed CHWs have since been dissolved in many areas to know managed by the DoH, except in the cases of Limpopo and the Western Cape (Quote S).

During our data collection there were announcements from South African government of a move to implement a minimum wage package for CHWs, and while in some districts this has now been initiated, there still remain many districts where this has not been implemented.

High burden of data collection and reporting

Data collection was described by participants as being time-consuming and information use was challenging due to resource limitations. Completing paperwork and the daily, weekly and monthly reporting that was frequently required was often described as burdensome and onerous and was on occasions even resented by patients. We collected reports that some patients would refuse to sign the forms because they were asked on every visit and did not see the benefit. The process of household registration was also reported to be time-consuming because forms are often not captured electronically or already collected information will often be missing and the process then has to be repeated (Quote T).

Challenges with tracing and record-keeping

An issue closely related to data management is tracing. This was highlighted by patient lists that are given to CHWs to trace those who are defaulting on chronic treatment or who need follow-ups for TB, pregnancy, immunizations, etc. The size of these lists per facility could vary greatly from just five up 500–800 individuals over a given month, while individual CHW house-visit lists could be as small as 2 and as large as 20 in the course of a week. Reported time to trace and follow up all of those on the list could be 2–3 h of walking in a day and between 2 and 3 weeks to trace everybody.

Success of tracing varied widely, from not finding any on the list to being able to successfully trace 9 out of 10 patients. The primary reason for low success was wrong addresses and phone numbers (S4: Quote U). This was also compounded by the fact that lists were often photocopied or hand-written making them difficult to read. The exceptions were in the Western Cape where tracing lists were emailed and even sent via WhatsApp. Client names also often reappear on these lists, even though there was a history of previous unsuccessful tracing attempts, or the patient had been confirmed as deceased and this would had been previously documented. Where CHWs self-selected the names of the patients that they were visiting from the lists, it was found that this also could result in duplication of effort, by the same CHW. More concerning though was the issue raised in one district where it seemed that CHWs did not even have a list of those who should be visited (Quote V) and just haphazardly visited households. The concept of ‘silent transfers’ where patients on antiretroviral therapy switch facilities without informing their originating facility nor their receiving facility was also frequently described and presented another challenge to tracing.

Concerns over safety and security

Safety and security remain a major concern among CHWs while they are out on the field tracing. As shown in Table 5, CHWs from Gauteng always went out in pairs because of safety concerns while the practice varied between working alone or in pairs in other districts. It was a concern everywhere, but most prominently noted in Gauteng and Western Cape.

Recommendations for improving implementation of WBPHCOT policy

Respondents offered a number of helpful suggestions on improving the current CHW programme implementation. The importance of permanent employment, a living wage and uniforms was discussed at almost all of the FGD sessions. These were indicated to be critical factors ensuring the livelihoods and well-being of CHWs.

Across all provinces, respondents noted that, even though training was received, more training was still needed (such as counselling generally, testing blood pressure and supporting diabetes). The issue of no certification for their trainings was also a recommendation for future trainings. A desire for being up-skilled through more training and further qualifications was also commonly highlighted as a recommendation (Quote X).

During data collection, we encountered reports of mobile health pilot interventions being implemented to ease the burden of data collection and programme management of the CHW programme in Gauteng, Mpumalanga and North West. Largely, this was well received and most respondents supported the introduction of mobile technology. However, this needed careful consideration and implementation as early indications in provinces where these systems have been piloted or used showed that the systems did not always provide helpful reporting nor did they have adequate management support. Although most supported it, others recommended against use of mobile tools for fear the devices may be stolen.

Other noteworthy considerations included emphasizing the importance of better integrating CHWs into the current PHC system (S4: Quote Y). Also, the potential use of community indicators (such as knowing one’s own HIV status) to assess CHW impact (S4: Quote Z) on progress towards UNAIDS 90-90-90 HIV targets.4

Discussion

We gathered a wide range of perspectives on models of the implementation of CHW policy in South Africa. We identified two major categories of CHW policy implementation support: (i) implementation supported by NGOs as seen in the provinces of Limpopo, Mpumalanga and the Western Cape and (ii) implementation managed by the DoH implemented as in the provinces of Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal and the North West. Western Cape and KwaZulu-Natal also have additional levels of non-clinical leadership (experienced CHWs promoted to support administrative and supervisory duties), to manage CHW activities. Hours of operation vary substantially and a few districts require ‘clock-in’ processes where CHWs are required to report to facilities. Other districts have ‘Health Posts’ or arrangements where CHWs can start their workdays directly from their communities, not always requiring a daily facility visit. ‘Health Posts’ described elsewhere consist of 3–6 rooms in temporary structures, often without water or electricity, and providing medication and minor treatments (Nxumalo, 2014; Tseng et al., 2019).

Key facilitators to implementation of the CHW policy included having effective OTLs in place, as well as individualized solutions to facility planning to improve CHW integration and tracing success. This included ensuring patients are allocated to specific CHWs prior to a missed visit to ensure effective tracing. CHWs’ ties and relationship with their community, their sense that they were making a difference and the trust of the communities were all seen as factors that facilitated successful implementation.

There were a number of barriers highlighted which threatened the success of these programmes, which were often centred on limitations. Insufficient numbers of CHWs, OTLs, equipment and supplies were frequently reported as a major challenge, as well as reports of a lack of respect and recognition from some in the community and from facility staff. Issues of a low wage, absence of a uniform, burdensome paper work, permanent employment and a lack of opportunity for professional growth were consistently highlighted by all CHWs with whom we engaged.

These findings largely align with the existing body of knowledge on the topic of CHW programme policy implementation: that leadership is in great demand (Schneider and Nxumalo, 2017b); that the policy is largely understood and followed, but that resources are constrained (Jinabhai et al., 2015). Also, aspects of implementation remain complex and challenged by limited availability of resources such as uniforms, equipment and stationery (Schneider et al., 2018; Clarke et al., 2008). As Jinabhai et al. (2015) had found, and also clear from this research, that WBPHCOTs are allocated to the areas of greatest need, based on social determinants of health (e.g. poverty, unemployment, violence and addiction) (Jinabhai et al., 2015). We also observed shortcomings of the existing paper-based data system as noted by Jinabhai et al. (2015) and observed a clear absence in the available use of available data for planning and implementation at all levels across the health system.

From our observations we believe that the implementation of the CHW policy must be adaptable and appropriate for the context in which it is implemented to achieve the objectives of PHC Re-engineering and support the implementation and rollout of universal health coverage5 in South Africa. (Stevenson, 2019). This assertion deviates slightly from the conclusions of Jinabhai et al. (2015) who call for one national centralized authority (Jinabhai et al., 2015), but perhaps reflects programme maturity and the need for provincial autonomy noted by Schneider et al. as implementation continues (Schneider and Nxumalo, 2017b).

Our findings support that supervision and leadership of CHWs is critical to the effective implementation of ward-based PHC outreach teams. A report led by Genesis (2019) recently provided a comprehensive evaluation that found similar findings to ours: an insufficient CHWs and insufficient OTLs (Genesis, 2019). Jinabhai et al. (2015) suggested that ‘Team leaders could be drawn from nursing and CHW cadres with sufficient qualifications, without appointing professional nurses who are in short supply and are the back bone of clinical care at facilities’—a strategy that we saw had been piloted and seems to have been successful in KwaZulu-Natal and the Western Cape. Conversely, Tseng et al. (2019) also explore the issue of supervision and emphasize the importance of the Professional Nurse cadre over a less senior, Enrolled Nurse (Rispel, 2015; Tseng et al., 2019).

A major challenge to the implementation of CHW policy was between full coverage and supporting those at most need. One of the major policy priorities is to ‘improve access to healthcare for poor and vulnerable communities in priority settings like the rural areas’ (SA NDoH, 2018a). The need for full coverage of CHWs across South Africa while ensuring the quality of that coverage and suitability of different implementation models in urban and rural settings presents a significant challenge. Focusing on optimal implementation in the subset of wards that are most in need, or potentially restricting the programme to rural rather than urban areas, might be considered as an interim solution while further resources are identified for complete quality coverage (Naidoo et al., 2018). Wahl et al. (2019), conversely, suggest that urban settings should not be excluded from CHWs’ services (Wahl et al., 2019).

A mobile health (mHealth) solution seems long overdue, considering the data gaps (Genesis, 2019), and the relative willingness of our respondents as well as the potential to address tracing challenges. A national policy document (Chowles, 2015) calls for a holistic approach to mHealth to ensure government leadership and stakeholder involvement and there are many existing projects from which to draw (Strydom, 2017; Venter et al., 2019).

A difficult but important issue to mention is safety. We collected the evidence of physical violence targeted towards some CHWs. This can be as severe as sexual violence, which has been reported in the popular South African media in the course of 2019 (Selepe, 2019). The overwhelming majority of CHWs in our sample (and in South Africa) are women—which might explain why CHWs’ safety while performing their duties was frequently raised as a challenge; the paucity of safety control measures for CHWs, besides travelling in groups, remains a concern. We collected no other safety procedures besides working in groups. In a different vein of safety, CHWs are currently being asked to serve as some of the primary screenings for the emerging COVID-19 global pandemic (van Dyk, 2020). With the consideration of their limited resources, including masks, this is an issue that requires urgent attention.

There are a number of strengths to the research presented here, namely: (i) presentation of findings from districts other than the National Health Insurance pilot districts (Jinabhai et al., 2015); (ii) the inclusion of both rural and urban districts as opposed to many CHW studies (van Rensburg et al., 2008; Schneider and Nxumalo, 2017a; Naidoo et al., 2018); and (iii) inclusion of a wide range of stakeholders from the national leadership to CHWs themselves.

Our major limitations were the routine forms of bias in qualitative research, namely qualitative research cannot be wholly generalizable to the country or even our selected provinces. We also recognize social desirability bias from respondents, selection bias in terms of our non-random selection and researcher bias (in the form of confirmation bias and also contamination from knowledge of the existing CHW research). Respondent bias was mitigated through an open-ended and non-leading interview guide and training prior to data collection. Our selection bias was balanced against our strength of having a large sample allowing viewpoints from across South Africa. We were unable to reach full FGD sample size because of time constraints and difficulty scheduling with a CHWs. Potential research bias was balanced through assessment of inter-coder reliability and review of interpretations during the write-up process. With our large sample size, we achieved saturation on most of our reported areas, but in other areas, such as reports of staff complement across wards, we did not achieve full saturation. We did not explore quality controls measures in depth and we were also unable to align the characteristics we collected to an objective measure of programme success, thereby highlighting opportunities for future work in this arena.

Conclusions

This research is unique in that it presents a detailed landscape of CHW policy implementation across several South African provinces. The passion, commitment and a feeling among CHWs that they can make a difference within the communities they serve is a key driver in ensuring the success of this programme. Although the CHW policy is widely recognized and understood, there are a number of challenges to implementation that still exist. The degree of collaboration between facility-based staff can be a facilitator or a barrier to implementation; this relationship can also be moderated by the presence of an involved OTL. We believe that it will be important to ensure that CHWs are given the visibility and recognition they seek through permanent employment, uniform, and a higher wage; also, that vacant OTL roles are filled as a priority with appropriate staff cadres. Mobile health solutions remain a priority to help CHWs effectively plan their work and to ensure that efforts are not wasted trying to support patients who are known to no longer be within the communities that CHWs support.

There are opportunities for learning across the existing models of CHW in South Africa. Implementation of other policies or strategies that might overlap or contradict the priorities of this policy needs to be introduced with care. Further research that builds on the information collected here and explores the preferences of CHWs and their managers for different attributes of CHW implementation (e.g. including leadership cadre, performance based-motivations, scope of work) using a discrete choice experiment or similar stated preferences design is warranted to further determine the focus to strengthen the implementation of this policy.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Health Policy and Planning online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all the CHWs, healthcare providers, data staff and other experts involved with the research directly or indirectly; community-based organizations and development partners; South African Department of Health at the National, Provincial and District levels; and the Research Team—Lezanie Coetzee, Kelebogile Kgokong and Daniel Letswalo. We also thank Noluthando Ndlovu from Health Systems Trust for help with mapping. We dedicate this work to Professor David Sanders who passed away on 31 August 2019, a champion of PHC and advocate for health as a human right as well as all healthcare workers facing the COVID-19 response in 2020.

Authors’ contributions

J.P.M., S.P. and D.E. conceptualized the study. J.P.M. oversaw data analysis, prepared the draft manuscript and managed subsequent revisions. J.P.M., S.P. and D.E. oversaw implementation of the study and all data collection. S.K., N.N., C.M., S.M. and A.M. analysed the IDIs and FGDs and contributed to writing the manuscript. J.M. provided substantive feedback on several iterations of the article.

Funding

This work has been made possible by the generous support of the American People and the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through USAID under the terms of Cooperative Agreements AID-674-A-12-00029 and 72067419CA00004 to HE2RO. The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of PEPFAR, USAID or the United States Government.

Conflict of interest statement. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval. Ethical approval for the study was granted from the Human Research Ethics (Medical) Committee of the authors’ institute. Data collectors were trained in qualitative interviewing techniques, good clinical practice, research ethics and study procedures. Respondents were not compensated for their time; however, CHWs participating in FGDs were reimbursed for any travel costs and provided with lunch.

Footnotes

Generally, we refer to WBPHCOT Policy Implementation as ‘CHW Policy Implementation’.

In this context, an implementing partner is a PEPFAR-funded organization who at the time of the study was mandated to provide technical support (such as training and mentoring) to support the implementation of CHW activities.

Rispel (2015) clarifies that a professional nurse requires 4 years of training and can specialize in midwifery, while an enrolled nurse requires only 2 years. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4430691/.

UNAIDS (2015) 90-90-90: treatment for all https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/909090.

Referred to as National Health Insurance in South Africa.

Currently CHWs work under community-based services.

Contributor Information

Joshua P Murphy, Health Economics and Epidemiology Research Office (HE2RO), Department of Internal Medicine, School of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg 2193, South Africa.

Aneesa Moolla, Health Economics and Epidemiology Research Office (HE2RO), Department of Internal Medicine, School of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg 2193, South Africa.

Sharon Kgowedi, Health Economics and Epidemiology Research Office (HE2RO), Department of Internal Medicine, School of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg 2193, South Africa.

Constance Mongwenyana, Health Economics and Epidemiology Research Office (HE2RO), Department of Internal Medicine, School of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg 2193, South Africa.

Sithabile Mngadi, Health Economics and Epidemiology Research Office (HE2RO), Department of Internal Medicine, School of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg 2193, South Africa.

Nkosinathi Ngcobo, Health Economics and Epidemiology Research Office (HE2RO), Department of Internal Medicine, School of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg 2193, South Africa.

Jacqui Miot, Health Economics and Epidemiology Research Office (HE2RO), Department of Internal Medicine, School of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg 2193, South Africa.

Denise Evans, Health Economics and Epidemiology Research Office (HE2RO), Department of Internal Medicine, School of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg 2193, South Africa.

Sophie Pascoe, Health Economics and Epidemiology Research Office (HE2RO), Department of Internal Medicine, School of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg 2193, South Africa.

References

- Bhattacherjee A. 2002. Social Science Research: Principles, Methods, and Practices. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=oa_textbooks, accessed 6 October 2019.

- Chowles T. 2015. NDoH Releases mHealth Strategy—eHealth News ZA, eHealth News. https://ehealthnews.co.za/ndoh-mhealth-strategy/, accessed 13 April 2020.

- Clarke M, Dick J, Lewin S. et al. 2008. Community health workers in South Africa: where in this maze do we find ourselves?. South African Medical Journal 98: 680–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE. et al. 2009. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science 4: 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman I. 2005. South African Health Review—CHWs and Community Caregivers: Towards a Unified Model of Practice, South African Health Review. Health Systems Trust. https://journals.co.za/content/healthr/2005/1/AJA10251715_21, accessed 30 May 2019.

- Genesis. 2019. Evaluation of Phase 1 implementation of interventions in the National Health Insurance (NHI) pilot districts in South Africa Final Evaluation Report. https://www.hst.org.za/publications/NonHST Publications/nhi_evaluation_report_final_14 07 2019.pdf, accessed 2 September 2019.

- Geng EH, Odeny TA, Lyamuya R. et al. 2016. Retention in care and patient-reported reasons for undocumented transfer or stopping care among HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy in Eastern Africa: application of a sampling-based approach. Clinical Infectious Diseases 62: 935–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinabhai C, Marcus T, Chaponda A.. 2015. Rapid APPRAISAL of Ward Based Outreach Teams. https://www.up.ac.za/media/shared/62/COPC/COPC Reports Publications/wbot-report-epub-lr-2.zp86437.pdf, accessed 23 May 2019.

- MacKinnon A. 2001. Of oxford bags and twirling canes: the state, popular responses, and Zulu antimalaria assistants in the early-twentieth-century Zululand malaria campaigns. Radical History Review 2001: 76–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naidoo N, Railton J, Jobson G. et al. 2018. Making ward-based outreach teams an effective component of human immunodeficiency virus programmes in South Africa. Southern African Journal of HIV Medicine 19: 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naimoli JF, Frymus DE, Wuliji T. et al. 2014. A community health worker “logic model”: towards a theory of enhanced performance in low- and middle-income countries. Human Resources for Health 12: 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Department of Health of South Africa 2011. Provincial guidelines for the implementation of the three streams of PHC Re-engineering. http://www.jphcf.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/GUIDELINES-FOR-THE-IMPLEMENTATION-OF-THE-THREE-STREAMS-OF-PHC-4-Sept-2.pdf, accessed 27 January 2020.

- Nxumalo N. 2014. Ward-based community health worker outreach teams: the success of the Sedibeng Health Posts. http://www.chp.ac.za/PolicyBriefs/Documents/Otra Policy Brief.pdf, accessed 27 January 2020.

- Oliver DG, Serovich JM, Mason TL.. 2005. Constraints and opportunities with interview transcription: towards reflection in qualitative research. Social Forces 84: 1273–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards L. 2014. Handling qualitative data: A practical guide. Sage Publications Limited.

- Rispel LC. 2015. Special issue: transforming nursing in South Africa. Global Health Action 8: 28205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SA NDoH. 2018a. Policy framework and strategy for ward-based primary healthcare outreach teams, 22. doi:978-1920031-98-5.

- SA NDoH. 2018b. Policy framework and strategy for ward-based primary healthcare outreach teams 2018/19–2023/24. https://rhap.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Policy-WBPHCOT-4-April-2018-1.pdf, accessed 26 May 2019.

- Schneider H, Besada, D, Daviaud, E et al. 2018. Ward-based primary health care outreach teams in South Africa: developments, challenges and future directions, South African Health Review, pp.59-65. https://www.hst.org.za/publications/Pages/SAHR2018.aspx, accessed 28 May 2019.

- Schneider H, Nxumalo N.. 2017a. Leadership and governance of community health worker programmes at scale: a cross case analysis of provincial implementation in South Africa. International Journal for Equity in Health 16: 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider H, Nxumalo N.. 2017b. Leadership and governance of community health worker programmes at scale: a cross case analysis of provincial implementation in South Africa Lucy Gilson. International Journal for Equity in Health 16: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider H, Okello D, Lehmann U.. 2016. The global pendulum swing towards community health workers in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review of trends, geographical distribution and programmatic orientations, 2005 to 2014. Human Resources for Health 14: 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selepe L. 2019. Healthcare workers assaulted and forced to strip naked while on duty, Independent Online. https://www.iol.co.za/the-star/news/healthcare-workers-assaulted-and-forced-to-strip-naked-while-on-duty-20143133, accessed 13 April 2020.

- Stellenberg E, Van Zyl M, Eygelaar J.. 2015. Knowledge of community care workers about key family practices in a rural community in South Africa. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine 7: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson S. 2019. Spotlight on NHI: what has actually changed in the new Bill? Spotlightt. https://www.spotlightnsp.co.za/2019/08/23/spotlight-on-nhi-what-has-actually-changed-in-the-new-bill/, accessed 2 September 2019.

- Strydom C. 2017. AitaHealth: When Technology and People Join Hands, Mezzanine. https://mezzanineware.com/aitahealth-when-technology-and-people-join-hands/, accessed 13 April 2020.

- Swartz A. 2013. Legacy, legitimacy, and possibility. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 27: 139–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolley, E, Ulin, P, Mack, N, et al. 2016. Qualitative methods in public health: a field guide for applied research. John Wiley & Sons.

- Tseng Y-h, Griffiths F, de Kadt J. et al. 2019. Integrating community health workers into the formal health system to improve performance: a qualitative study on the role of on-site supervision in the South African programme. BMJ Open 9: e022186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dyk J. 2020. Pandemic Politics: Community Health Workers Gear Up to Fight COVID-19 with Little Protection, Less Pay—Bhekisisa, 2Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. https://bhekisisa.org/features/2020-03-31-pandemic-politics-community-health-workers-gear-up-to-fight-covid19-with-little-protection-less-pay/, accessed 13 April 2020.

- van Rensburg DH, Steyn F, Schneider H. et al. 2008. Human resource development and antiretroviral treatment in Free State province, South Africa. Human Resources for Health 6: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venter WDF, Fischer A, Lalla-Edward ST. et al. 2019. Improving linkage to and retention in care in newly diagnosed HIV-Positive patients using smartphones in South Africa: randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research 7: e12652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl B, Lehtimaki S, Germann S. et al. 2019. Expanding the use of community health workers in urban settings: a potential strategy for progress towards universal health coverage. Health Policy and Planning 35: 91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.