Abstract

Background: mycobacterial cells contain complex mixtures of mycolic acid esters. These can be used as antigens recognised by antibodies in the serum of individuals with active tuberculosis, caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In high burden populations, a significant number of false positives are observed; possibly these antigens are also recognised by antibodies generated by other mycobacterial infections, particularly ubiquitous ‘environmental mycobacteria’. This suggests similar responses may be observed in a low burden TB population, particularly in groups regularly exposed to mycobacteria. Methods: ELISA using single synthetic trehalose mycolates corresponding to major classes in many mycobacteria was used to detect antibodies in serum of individuals with no known mycobacterial infection, comprising farmers, abattoir workers, and rural and urban populations. Results: serum from four Welsh or Scottish cohorts showed lower (with some antigens significantly lower) median responses than those reported for TB negatives from high-burden TB populations, and significantly lower responses than those with active TB. A small fraction, particularly older farmers, showed strong responses. A second study examined BCG vaccinated and non-vaccinated farmers and non-farmers. Farmers gave significantly higher median responses than non-farmers with three of five antigens, while there was no significant difference between vaccinated or non-vaccinated for either farmer or non-farmer groups. Conclusions: this initial study shows that serodiagnosis with mycobacterial lipid antigens can detect antibodies in a population sub-group that is significantly exposed to mycobacteria, in an assay that is not interfered with by vaccination. Given the links between mycobacterial exposure and a range of immune system diseases, further understanding such responses may provide a new opportunity for monitoring public health and directing treatment.

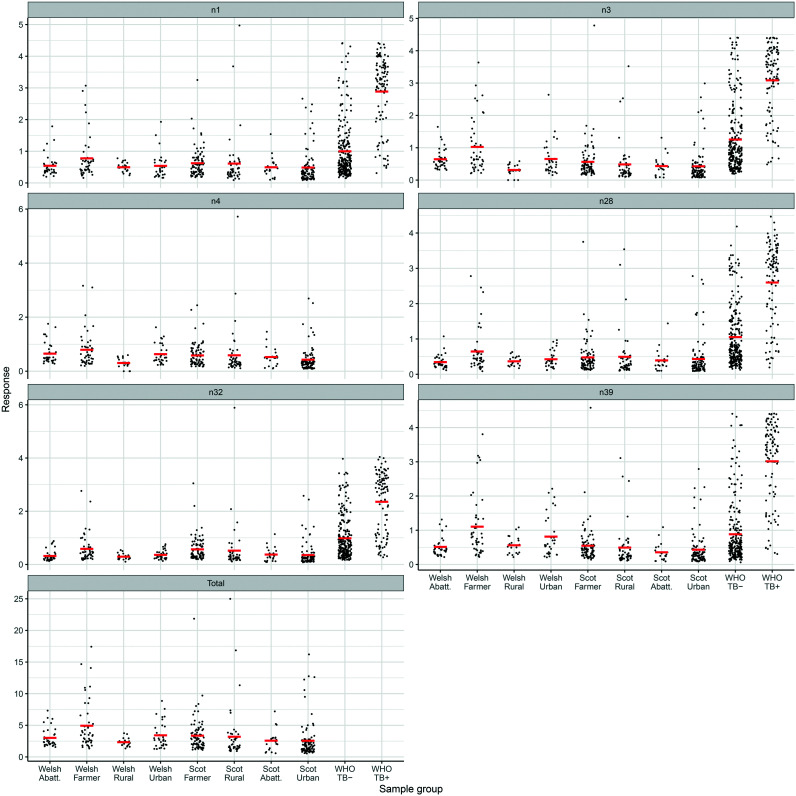

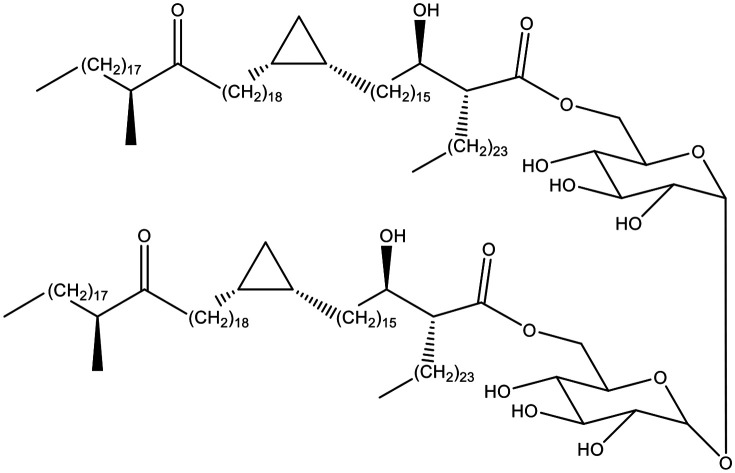

Antibody binding to trehalose mycolates, such as that shown, was evaluated in ELISA. Median responses with the serum of individuals with no known mycobacterial infection were low; some were very high, the majority from Welsh farmers older than 55.

Introduction

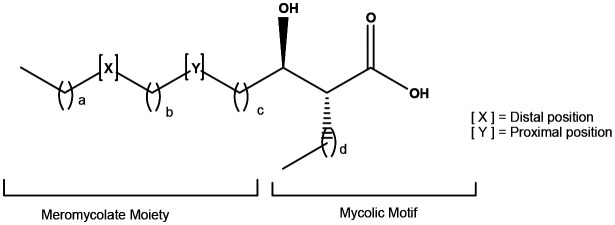

Mycobacteria contain characteristic long chain fatty acids, mycolic acids (MA) (Fig. 1), often comprising 90–100 carbon atoms,1–6 and present as very complex mixtures of different structural classes (X and Y), each normally present as an homologous series differing by two methylene groups. The common groups Y (Fig. 1) are cis-alkenes and cis-cyclopropanes, and trans-alkenes and trans-cyclopropanes with a methyl substituent on the adjacent carbon. Common groups X are cis-alkenes and cyclopropanes, trans-alkenes with an adjacent methyl group on the carbon distal from the hydroxy acid, and –CH(Me)CH(OMe)– or –CH(Me)CO– groups; the absolute stereochemistry of these substituents is now largely defined.6 The detailed composition of these mixtures provides a fingerprint for the particular mycobacterium.3,4 MA are commonly bound to the cell wall as penta-arabinose tetramycolates, non-wall bound, often as trehalose dimycolates (TDM) and monomycolates (TMM), and also as free MA. Natural mixtures of free MA cause inflammatory immune system responses; similar effects are seen with single synthetic MA, depending subtly on the structure.7,8 Natural mixtures of MA esters have very significant effects on cytokines and chemokines – TDM is a major component of Freund's total adjuvant,9 while BCG vaccine is an extract of modified cells.10 The apparent link between BCG vaccination and the control of viral infections such as Covid-19 has been highlighted.11 BCG vaccine has been shown to reduce the severity of infections by other viruses with similar structure, reducing yellow fever vaccine viraemia,12 and the severity of mengovirus infection.13,14 BCG vaccine also has beneficial nonspecific effects on the immune system that protect against a wide range of other infections and is used routinely to treat bladder cancer.15

Fig. 1. Typical mycolic acid structure.

Single synthetic MA esters also show inflammatory properties and adjuvant potential, which depend on detailed structure,16 while single synthetic MA esters modulate the responses of CD1b-restricted GEM T cells depending on the mero-mycolate chain.17

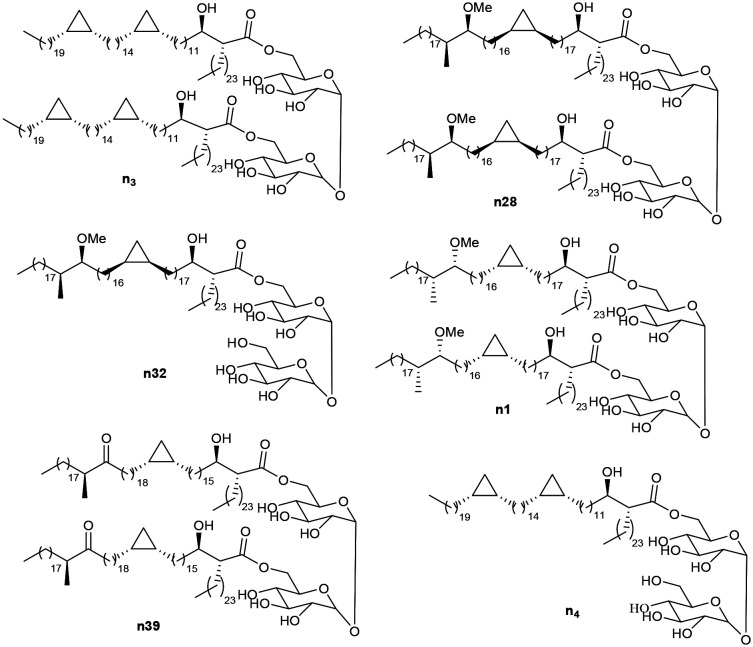

The recognition of natural mixtures of MA by antibodies in infected serum has been applied in serodiagnosis of tuberculosis;18 complex mixtures of trehalose esters of MA (TDM) isolated from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTb) or Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) differentiate the two infections.19–24 However, the WHO evaluated a large set of serodiagnostic assays and indicated that none met its required standards; it indicated, however, that a serodiagnostic method that did work would be very valuable.25 Individual synthetic TDMs comprising different classes of MA are also recognised in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) by antibodies in the serum of patients with active TB.26 The sensitivity (correct positives) and specificity (correct negatives) obtained using serum from patients from high TB-burden countries and showing symptoms of disease, but clinically diagnosed with (TB+) or without (TB−) active disease, depend on the detailed substituents X and Y of the MA (Fig. 1), and on their stereochemistry.26 From an initial group of some 15 synthetic TDMs and TMMs from different classes of synthetic MA, optimal values of around 85 and 85% sensitivity/specificity were obtained with single antigens (Fig. 2); the performance of antigens n3, n28, n32, n1, and n39 was rather similar, but in each case somewhat better than that of natural MTb TDM. Combination of the results with single antigens gave increased performance.26 Nonetheless, serum samples from some TB− patients consistently showed responses to each of these lipid antigens; one explanation is that, because complex mixtures of MA are present in all mycobacteria, there is a cross-reactivity and the antigens also bind to antibodies generated by exposure to other organisms, such as ubiquitous NTM.27 Another possibility is that there is a higher background response to such lipid antigens in a high burden population, particularly in individuals showing at least some symptoms of TB.

Fig. 2. Antigens known to distinguish active TB from not active TB in high burden populations,26 and used in this study.

Although tuberculosis remains a major global killer, infections by ‘non-tuberculous’ environmental mycobacteria (NTM), such as MAC, are increasing across the world.28 Apparent links have been reported between exposure to mycobacteria and a number of diseases (e.g., the observation of elevated levels of Mycobacterium avium paratuberculosis (MAP) in some Crohn's patients,29 the link between NTM and bronchiostasis,30 and infection with Mycobacterium abscessus in cystic fibrosis patients).31 Moreover, there is an increasing problem of infections by MAC in ageing populations,28,32 and by Mycobacterium malmoense;33 both are commonly found in water and soil. We were interested therefore to determine whether exposure to environmental mycobacteria generates antibodies to cell wall lipids in a low TB burden population and, in turn, to responses to MA-based antigens in ELISA.

We report studies of two sets of serum samples, the first from individuals living in Wales or Scotland, originally collected for a study of Escherichia coli in farmers and abattoir workers,34 the second from a cohort of Welsh farmers and non-farmers with no known symptoms of TB.

Study design and methods

The serum samples

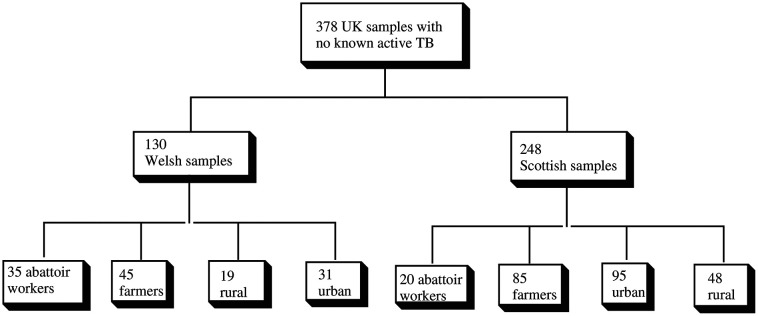

The first set of 378 sera,34 were used under an appropriate ethical approval.35 The Welsh samples were divided into four broad sets, those from: i) farmers (WF); ii) abattoir workers (WA); iii) people living in rural Wales (WR); iv) people living in urban Wales (WU). The Scottish samples were divided into four corresponding sets (SF, SA, SR, SU) (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Study plan: initial study.

The results were compared with those reported, using the same ELISA method, with serum from patients primarily from high burden TB countries, showing symptoms of disease but clinically diagnosed as active (TB+) or not active (TB−). These were provided by the WHO from the UNICEF/UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases TB Specimen Bank (labelled as WHO samples).26

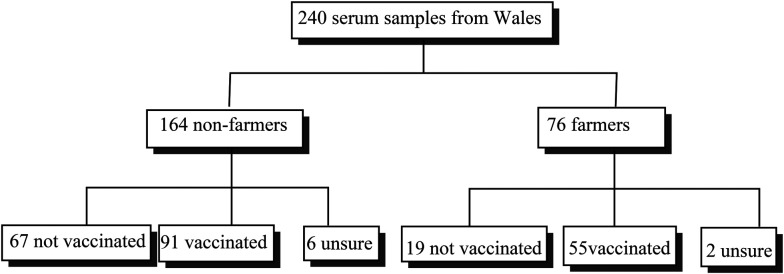

The second study used serum collected, with appropriate ethical approval,36 from farmers and non-farmers in Wales. The information collected included the BCG vaccination status of each individual (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Second study: Welsh farmers and non-farmers with vaccination status.

Those with unknown BCG vaccination status were excluded from the calculations in respect of this, but were included in overall calculations of medians and total responses.

The study demographics are given in ESI† (Table S1).

The ELISA method26

ELISA were carried out in 96-well flat-bottomed polystyrene micro-plates. Antigens were dissolved in hexane to give concentration of 15 μg ml−1. 50 μl of this solution was added to each well, and the solvent was left to evaporate at room temperature. Control wells were coated with hexane (50 μl per well) only. Blocking was done by adding 400 μl of 0.5% casein/PBS buffer (pH = 7.4) to each well, and the plates were incubated at 25 °C for 30 minutes. The buffer was aspirated and any excess was flicked out until the plates were dry. Serum (1 in 20 dilution in casein/PBS buffer) (50 μl per well) was added and incubated at 25 °C for 1 hour. The plates were washed with 400 μl casein/PBS buffer 3 times using an automatic washer, and any excess buffer was flicked out onto a paper towel until dry. Secondary antibody (anti-human IgG (Fc specific) peroxidise conjugated antibody produced in goat (Aldrich)) (diluted to a concentration of 1 : 2000 in casein/PBS buffer) (50 μl per well) was added, and incubated at 25 °C for 30 minutes. The plates were again washed 3 times with 400 μl casein/PBS buffer, and any excess buffer was flicked out. OPD substrate (50 μl per well) (o-phenylenediamine (1 mg ml−1) and H2O2 (0.8 mg ml−1) in 0.1 M citrate buffer) were then added, and the plates were incubated for 30 minutes at 25 °C. The colour reaction was terminated by adding 2.5 M H2SO4 (50 μl per well), and the absorbance was read at 492 nm. ELISA responses above 3 should not be treated as quantitative. Absorbances reported have not been adjusted in this paper, for example by removing a standard background. The assays were run blind.

The antigens

The antigens used were as in the earlier TB study,26 and cover the three main classes of MA present in M. tuberculosis (α-, methoxy and keto). They were selected in that study from a wider set of some 15 synthetic TDMs and TMMs as giving the best sensitivity/specificity combination and were run with the largest sample set. They were chosen for this current study to provide the most direct comparison. They were synthesised by methods described before.37,38 Antigen n3 is a trehalose dimycolate (TDM) of an α-mycolic acid corresponding the main chain lengths and stereochemistry of such compounds in M. tuberculosis. TDM n28 and the corresponding trehalose monomycolate (TMM) n32 and TDM n1 incorporate stereoisomers of the major chain length of TB methoxy-mycolic acid, but gave good sensitivity and specificity in the TB study.26 Compound n39 is the TDM of a keto-mycolic acid with the natural stereochemistry and chain lengths. Antigen n4 was not evaluated with the full set of WHO samples but is included as the TMM corresponding to TDM n3.

Results

The binding of synthetic antigens to antibodies in serum from the different groups within Wales and Scotland was compared to median responses (already published) from the WHO sample bank (described earlier).26 These were taken from people who had been referred to a clinic with some of the symptoms of tuberculosis. Those in the TB+ set were clinically diagnosed to have active disease and were culture positive; those in the TB− set were culture negative and were diagnosed as not having active disease.

The median results for the ELISA assays for the six antigens, carried out in triplicate, are presented in Table 1, compared to the corresponding figures for WHO TB+ and TB− samples.26Table 1 also includes an analysis of the significance of differences between each group of samples within the two sets.

Median absorbances for four classes of Welsh and Scottish serum from individuals with no known mycobacterial infection, compared to those for WHO TB+ and TB− samples26.

| Antigen median | Pairwise significance | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHO TB+ comparison | WHO TB− comparison | Farmer comparison | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Wales | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of samples | n3 | n28 | n32 | n1 | n39 | n4 | n3 | n28 | n32 | n1 | n39 | n3 | n28 | n32 | n1 | n39 | n3 | n28 | n32 | n1 | n39 | n4 | |

| WA | 35 | 0.56 | 0.3 | 0.25 | 0.4 | 0.43 | 0.49 | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns | ns | ** | ns | *** | ns | ns | ns | ns | * | ns |

| WF | 45 | 0.65 | 0.4 | 0.42 | 0.6 | 0.79 | 0.58 | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns | ns | ns | ns | *** | ||||||

| WR | 19 | 0.29 | 0.3 | 0.27 | 0.5 | 0.52 | 0.29. | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns | ns | ns | ns | *** | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | * |

| WU | 31 | 0.49 | 0.4 | 0.32 | 0.5 | 0.57 | 0.50 | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns | ns | * | ns | *** | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Scotland | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA | 20 | 0.39 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.42 | 0.31 | 0.50 | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns | ns | ns | * | ns | ns | ns | ** |

| SF | 85 | 0.43 | 0.36 | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.42 | 0.44 | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns | ns | ||||||

| SR | 48 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.33 | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | * | * | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| SU | 95 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.30 | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | * | ns | *** | ** | * | ns |

| WHO | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TB− | 247 | 0.90 | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.55 | — | ||||||||||||||||

| TB+ | 102 | 3.40 | 3.03 | 2.83 | 3.24 | 3.36 | — | ||||||||||||||||

The results for individual serum samples are shown in the dot-plots in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Dot plots of responses for each set of serum samples with six antigens and the total response.

The total responses in the assays with each of the antigens were summed for each serum sample from Wales and ranked in descending order; 9 out of 44 farmer's samples (ESI† Table S2) showed total values above the WHO TB− median, and a large number of individual values above the individual medians. A small number of individual values were above the median reported for the WHO TB+ set. Table S3 (ESI†) shows the same analysis for the Scottish samples, where two were above the WHO TB+ total response. A more detailed analysis of the responses of Welsh farmers is shown in Fig. 4, which shows increasing responses with age. The Welsh farmer set was therefore reanalysed for those under 55 and those over 55. The difference is significant for antigen n32 (ESI† Table S4).

Fig. 4. Distribution of ELISA responses for each set of Welsh samples by age in years for each single antigen and the total response, with trend lines.

The corresponding analysis by age for the WA, WR and WU groups is given in ESI† (Fig. S4).

In the second study, a set of samples from farmers and non-farmers collected in North Wales was analysed using five antigens, to determine whether or not previous vaccination with BCG would induce strong responses. The results are given in Table 2.

Median responses for second set of serum samples from farmers and non-farmers in Wales. Significance figures compare all farmers with non-farmers and vaccinated and non-vaccinated samples within each set.

| Farmers | Non-farmers | Farmers | Non-farmers | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCG vaccinated | Non-vaccinated | BCG vaccinated | Non-vaccinated | ||||||

| Antigen | Median | Median | p value | Median | Median | p value | Median | Median | p value |

| n3 | 0.28 | 0.21 | 0.0026 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.209 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.047 |

| n28 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.0081 | 0.18 | 0.28 | 0.623 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.888 |

| n32 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.4462 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.36 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.316 |

| n4 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 0.044 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.373 | 0.32 | 0.22 | 0.033 |

| n39 | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.0014 | 0.27 | 0.33 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.198 |

The results for those samples with a total response higher than twice the overall median with all the antigens, ranked in order, are given in Table S5 (ESI†). Two farmers and one non-farmer gave total responses above the WHO TB+ set. The highest responder (responses well above linear scale of instrument) had recently returned from a high burden TB country and was diagnosed with an ascaris worm infection; such infections are linked to changes in TB immunity.39 The distributions of responses for each set by age are given in Fig. S6 (ESI†).

Discussion

Natural mixtures of mycolic acids (MA) show wide-ranging effects on the immune system.40 They will, e.g., control asthma in an experimental mouse model; single synthetic MA are even more effective in this model and show differential effects on a range of cytokines and chemokines.41 Sugar esters such as TDM are known to show very strong effects in the immune system.16,17 In a similar way, MA have been shown to be antigenic to antibodies in the serum of people with active TB; natural mixtures of MA sugar esters provide a rather simpler distinction between TB+ and TB− samples, but such a method has to date not proved good enough to be accepted by the WHO.25

To try to improve the performance of such approaches, we have examined the use of single synthetic mycolic acids and their sugar esters.26 Synthetic antigens, identical to, or stereoisomeric with, major components of natural sugar esters, were coated on ELISA plates. These were treated with human serum, then with a labelled secondary human antibody, Ig(Fc) which was visualised by the addition of an oxidase; this gave good sensitivity and specificity in distinguishing clinically defined TB+ from TB− samples. There were subtle differences between the responses to a set of 15 different antigens, but five provided the best combinations of sensitivity and specificity – a di-cyclopropane α-MA TDM (n3), a keto-MA TDM (n39), both with the natural absolute stereochemistry, methoxy-MA TDM (n28) and TMM (n32), with the opposite absolute cyclopropane stereochemistry to the natural molecule, and methoxy-MA TDM (n1), with the opposite absolute distal methoxy fragment stereochemistry.38 However, within the WHO TB− serum set, there were a number of apparent false positives with each antigen, perhaps partly due to infection with NTM, such as M. abscessus, MAC or MAP, or indeed bovine TB.

We therefore report the application of the same synthetic lipid antigens in ELISA using a series of human serum samples with no known mycobacterial infection, to probe the baseline signal for a country without a high level of TB, and to determine whether any pattern could be identified for any serum samples giving high signals.

The median responses for the all sub-groups of Welsh and Scottish samples were significantly lower than the TB+ samples (***, Table 1). As in the earlier TB study,26 all five antigens gave broadly similar patterns of response, largely independent of the nature of the distal group (Y, Fig. 1) or absolute stereochemistry. In the Welsh samples, medians were generally lower than those of the TB− samples, though only significantly so for antigen n32 with WA and WU sets; antigen n39 was significantly different from TB−, except for the WF when it was higher (***). The WA, WU and WR groups gave lower responses than WF with all antigens, but not significantly so except for WA with n39 and WR with n4. It is interesting to note that n39 is the TDM of a keto-MA, which was marginally the best antigen in the earlier TB study.26

However, the lack of statistical significance hid large sample to sample differences. Thus, when the results from the Welsh samples were ranked by total response to all the antigens, and those above the TB− median were selected (ESI† Table S2), seven of the top eight samples were from farmers. No samples gave a total value higher than the median for the WHO+ set. However, while the median for farmers under 55 was very similar to that for non-farmers, that for farmers over 55 years old was significantly higher as seen by the trend lines in Fig. 4. In the case of n32 this difference was significant (p = 0.006, ESI,† Table S4). This response suggests elevated levels of antibodies to mycobacterial lipids. It is possible they may reflect a lifetime of exposure to environmental mycobacteria, including MAP, and to animals carrying bovine TB, or simply reflect the trend seen worldwide,42–44 exemplified in the US,45,46 Canada,47 Japan,48 and Korea,28 that NTM infections in the older population groups are growing considerably. There was no such clear trend with the other sets of Welsh samples (ESI,† Fig. S4).

It is interesting that in this set of samples, those from abattoir workers were generally similar to urban and rural samples, perhaps reflecting the controlled environment in which they work. The abattoir worker with the most elevated response was the individual responsible for disposing of all intestinal material.

In the case of the Scottish set, there was a significant difference across all groups and antigen from the WHO+ medians. All groups also showed a significant difference to the WHO− median with three of the five antigens, but no significant difference with SA and SF sets with antigens n1 and n39. Moreover, the medians for the SF group were below those for the WHO− group, whereas for the WF it was higher. When the results for all the samples were ranked by their total response (ESI† Table S3), only 14 of the 42 samples with total responses above the WHO TB− set were farmers. One farmer and one abattoir worker gave total responses above the WHO TB+ median. The distribution of responses did not show the increase with age for the Scottish farmers (ESI† Table S4, Fig. S4). It is possible that this reflects to some extent the lack of bovine tuberculosis in Scotland, and therefore exposure of the SF set to Mycobacterium bovis, but at this stage it is not possible to rule out other factors.

In the second study, serum samples collected from groups of farmers and non-farmers from Wales, with known BCG vaccination status, were examined by ELISA using five antigens (Table 2). The medians for the farmer set were significantly higher than for the non-farmer set for three of the five antigens. When the total median responses were ranked in order, 14 (out of 76) farmers and 15 (out of 164) non-farmers gave values more than the TB− median and three were above the TB+ median (ESI† Table S5). Interestingly, two of the top five responses were from non-farmers whom had recently returned from high burden TB areas, suggesting that, at least in these cases, the responses might be caused by exposure to Mtb. There were no significant differences between the median responses with any antigen for vaccinated and un-vaccinated groups of either farmers or non-farmers. This supports the result of the earlier TB diagnostic study, that BCG vaccination does not lead to false positives.26 There was some evidence of an increased response in farmers with age (ESI† Fig. S6) but there were not many older farmers in this cohort.

Within this second group, one sample stood out, giving much higher responses than any other sample in this group or in the earlier study of samples from patients with active tuberculosis.26 This sample was from an individual diagnosed as having an ascaris infection, and who had recently returned from a country where TB is endemic. Such infections are known to cause significant changes to the immune system.39,49

The compounds present in the cell walls of mycobacteria, and their synthetic analogues as used in this work, are known to show very strong effects on a range of cytokines and chemokines and may provide a link between exposure to mycobacteria and the development of immune system diseases. A more detailed understanding of why the serum of some individuals, with no known mycobacterial infection, appear to bind strongly to these antigens – and potentially to a wider range of characteristic mycobacterial antigens such as diene mycolic acids,50 and wax ester mycolates51 – may offer the potential for early warning of immune system changes that could in time lead to disease, or of existing disease that has caused changes to immune system responses. It is also necessary to rule out responses to antibodies that are cross-reactive to non-MA ester antigens, such as those responding both to cholesterol and free mycolic acids.52

Conclusions

Serum from individuals with no known mycobacterial infection taken from four groups of people living in Wales and Scotland showed median responses that were somewhat lower than those reported for a population of individuals from TB endemic countries having TB symptoms, but clinically diagnosed as TB−, and significantly lower responses than a population with active TB. However, some individuals, particularly from a group of farmers, showed very high responses. Within the farmers set, responses were significantly higher with some antigens for individuals over 55 years old. It is dangerous to draw firm conclusions from this initial study, but this group has clearly been exposed to environmental mycobacteria for a longer period, and also are in the age group where NTM infections become more prominent.

A second study involved groups of farmers and non-farmers from Wales, and including those known to have been vaccinated with BCG, and those not vaccinated. The farmer cohort showed significantly lower responses with three of five antigens, but there was no significant difference between BCG vaccinated or non-vaccinated farmers, or the corresponding non-farmers.

Over the 618 samples evaluated, only five gave total signals exceeding the WHO TB+ median. This suggests that false positives would not represent a major problem in serodiagnosis of TB using lipid antigens in a low burden population. Moreover, the lack of effect of vaccination suggests that such an assay would ‘not be interfered with by vaccination’ (NIVA).

Whatever the reason for the differences in the responses for farmers from the other sub-sets, there appears to be a strong case for understanding them further, and probing their possible link to particular exposure to mycobacteria, or to existing or developing infections. It is possible that routine measurement of responses of antibodies in serum to lipid antigens might provide a rapid means for guiding public health practices, identifying the early stage infection and controlling exposure of at-risk population groups. The links between infection by mycobacteria and the virulence of disease, highlighted by the apparent link between BCG vaccination, Covid-19 and the control of viral infections suggests this deserves further study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was partly supported by the Welsh Government to MSB, CDG and APW under the A4B programme, grant HE6-15-1012. Initial funding for the collection of samples was provided by the Rural Economy & Land Use (RELU programme) project ‘Reducing E. coli O157 risk in rural communities’ (award number: RES-229-25-0012); we thank the Scottish partners for making their samples available for this study.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/d0md00325e

References

- Daffé M., Quémard A. and Marrakchi H., Biogenesis of Fatty Acids, Lipids and Membranes, 2017, pp. 1–36 [Google Scholar]

- Barry C. E. Lee R. E. Mdluli K. Sampson A. E. Schroeder B. G. Slayden R. A. Yuan Y. Prog. Lipid Res. 1998;37:143–179. doi: 10.1016/S0163-7827(98)00008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M. Aoyagi Y. Ridell M. Minnikin D. E. Microbiology. 2001;147:1825–1837. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-7-1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M. Aoyagi Y. Mitome H. Fujita T. Naoki H. Ridell M. Minnikin D. E. Microbiology. 2002;148:1881–1902. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-6-1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnikin D. E., in The Biology of the Mycobacteria, ed. C. Ratledge and J. Stanford, Academic Press, London, 1982, pp. 95–184 [Google Scholar]

- Verschoor J. A. Baird M. S. Grooten J. Prog. Lipid Res. 2012;51:325–339. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korf J. Stoltz A. Verschoor J. De Baetselier P. Grooten J. Eur. J. Immunol. 2005;35:667–1007. doi: 10.1002/eji.20042533. doi: 10.1002/eji.20042533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Beken S. Al Dulayymi J. R. Naessens T. Koza G. Maza Iglesias M. Schubert-Rowles R. Theunissen C. De Medts J. Lanckacker E. Baird M. S. Grooten J. J. Innate Immun. 2017;9:162–180. doi: 10.1159/000450955. doi: 10.1159/000450955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubé J.-Y. McIntosh F. Zarruk J. G. David S. Nigou J. Behr M. A. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:5874. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62543-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades E. R. Geisel R. E. Sakamoto K. Russell D. G. Rhoades E. R. J. Immunol. 2005;174:5007–5015. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.5007. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis N. Sparrow A. Ghebreyesus T. A. Netea M. G. Lancet. 2020;395:1545–1546. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31025-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arts R. W. J. Moorlag S. J. C. F. M. Novakovic B. et al. . Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; .e5

- Old L. J. Benacerraf B. Clarke D. A. Carswell E. A. Stockert E. Cancer Res. 1961;21:1281–1300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floc'h F. Werner G. H. Ann. Immunol. 1976;127:173–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard A. J. Finn A. Curtis N. Arch. Dis. Child. 2017;102:1077–1081. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-310282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tima T. G. Al Dulayymi J. R. Denis O. Lehebel P. Baols K. S. Mohammed M. O. L'Homme L. Sahb M. M. Potemberg G. Legrand S. Lang R. Beyaert R. Piette J. Baird M. S. Huygen K. Romano M. J. Innate Immun. 2017;9:162–180. doi: 10.1159/000450955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chancellor A. Tocheva A. S. Cave-Ayland C. Tezera L. White A. Al Dulayymi J. R. Bridgeman J. S. Tews I. Wilson S. Lissin N. M. Tebruegge M. Marshall B. Sharpe S. Elliott T. Skylaris C.-K. Essex J. W. Baird M. S. Gadola S. Elkington P. Mansour S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017;114:E10956–E10964. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1708252114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1708252114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleicher G. K. Feldman C. Vermaak Y. Verschoor J. A. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2002;40:882–887. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2002.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekura R. Nakagawa M. Nakamura Y. Hiraga T. Yamamura Y. Ito M. Ueda E. Yano S. He H. Oka S. Kashima K. Yano I. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1993;148:997–1001. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.4_Pt_1.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J. Fujiwara N. Oka S. Maekura R. Ogura T. Microbiol. Immunol. 1999;43:863–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1999.tb01221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y. Doi T. Sato K. Yano I. Microbiology. 2005;151:2065–2074. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27790-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y. Ogata H. Yano I. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2005;43:1253–1262. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2005.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Marin L. M. Segura E. Hermida-Escobedo C. Lemassu A. Salinas-Carmona M. C. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2003;36:47–54. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y. Doi T. Maekura R. et al. . J. Med. Microbiol. 2006;55:189–199. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation, Global Tuberculosis Report 2018

- Jones A. Pitts M. Al Dulayymi J. R. Gibbons J. Ramsay A. Goletti D. Gwenin C. D. Baird M. S. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181414. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grange J. M., in Medical Microbiology, ed. D. Greenwood, R. Slack, J. Peitherer and M. Barer, Elsevier,17th edn, 2007, pp. 221–227, ISBN 978-0-443-10209-7 [Google Scholar]

- Tzoul C. L. Dirac M. A. Becker A. L. Beck N. K. Weigel K. M. Meschke J. S. Cangelosi G. A. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2020;17:57–62. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201812-915OC. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201812-915OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naser S. A. Collins M. T. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2005;11:1123. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000191609.20713.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shteinberg M. Stein N. Adir Y. Ken-Dror S. Shitrit D. Bendayan D. Fuks L. Saliba Saliba W. Eur. Respir. J. 2018;51:1702469. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02469-2017. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02469-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deciacomi G. Sammartino J. C. Chiarelli L. R. Riabova O. Makarov V. Pasca M. R. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;22;20(23):E5868. doi: 10.3390/ijms20235868. doi: 10.3390/ijms20235868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y. Hirai T. Fujita K. Maekawa K. Niimi A. Ichiyama S. Mishima M. J. Infect. Chemother. 2015;21:352–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon Y.-S. Koh W.-J. Daley C. L. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 2019;82:15–26. doi: 10.4046/trd.2018.0060. doi: 10.4046/trd.2018.0060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quilliam R. S. Chalmers R. M. Williams A. P. Chart H. Willshaw G. A. Kench S. M. Edwards-Jones G. Evans J. Thomas D. R. Salmon R. L. Jones D. L. Zoonoses Public Health. 2012;59:83–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2011.01430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betsi Cadwaladr NHS Health Research Authority, 08/WNo01/57 [Google Scholar]

- Betsi Cadwaladr NHS Health Research Authority, 14/WA/1046 [Google Scholar]

- Al Dulayymi J. R. Baird M. S. Maza-Iglesias M. Vander Beken S. Grooten J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:3702–3705. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.03.213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al Dulayymi J. R. Baird M. S. Maza-Iglesias M. Hameed R. T. Baols K. S. Muzael M. Saleh A. D. Tetrahedron. 2014;70:9836–9852. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2014.10.072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Resende Co T. Hirsch C. S. Toossi Z. Dietze R. Ribeiro-Rodrigues R. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2007;147:45–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryll R. Kumazawa Y. Yano I. Microbiol. Immunol. 2001;45:801–811. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2001.tb01319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smet M. Pollard C. De Beuckelaer A. Van Hoecke L. Beken S. V. De Koker S. Al Dulayymi J. R. Huygen K. Verschoor J. Baird M. Grooten J. Eur. J. Immunol. 2016;46:2149–2154. doi: 10.1002/eji.201646357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevots D. R. Marras T. K. Clin. Chest Med. 2015;36:13–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2014.10.002. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson L.-O. Polverino E. Hoefsloot W. Codecasa L. R. Diel R. Jenkins S. G. Loebinger M. R. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2017;11:12:977–989. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2017.1386563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley C. L. and Griffith D. E., Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections, Murray and Nadel's Textbook of Respiratory Medicine, 6th edn, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Adjemian J. Olivier K. N. Seitz A. E. Holland S. M. Prevots D. R. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012;8:881–886. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-2016OC. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-2016OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkle E. Hedberg K. Schafer S. Novosad S. Winthrop K. L. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2015;12:642–647. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201412-559OC. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201412-559OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brode S. K. Chung H. Campitelli M. A. Kwong J. C. Marchand-Austin A. Winthrop K. L. Jamieson F. B. Marras T. K. Emerging Infect. Dis. 2019:25. doi: 10.3201/eid2507.181817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namkoong H. Kurashima A. Morimoto K. Hoshino Y. Hasegawa N. Ato M. Mitarai S. Emerging Infect. Dis. 2016;22:1116–1117. doi: 10.3201/eid2206.151086. doi: 10.3201/eid2206.151086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midttun H. L. E. Acevedo N. Skallerup P. Almeida S. Skovgaard K. Andresen L. Skov S. Caraballo L. van Die I. Jørgensen C. B. Fredholm M. Thamsborg S. M. Nejsum P. Williams A. R. J. Infect. Dis. 2018;217:310–319. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix585. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhuwaymil Z. S. Al-Dulayymi A. R. Jones A. Gates P. J. Valero-Guillén P. L. Baird M. S. Al Dulayymi J. R. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2020;233 doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2020.104977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; , in press

- Jones A. Lee O. Y.-C. Minnikin D. E. Baird M. S. Al Dulayymi J. R. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2020;230:104928. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2020.104928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranchod H. Ndlandla F. Lemmer Y. Beukes M. Niebuhr J. Al-Dulayymi J. Wemmer S. Fehrsen J. Baird M. Verschoor J. A. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0200298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.