Brief summary:

Nursing home health disparities are pervasive at the end-of-life and efforts are needed to address the cultural barriers and increase access to resources that nursing home with higher proportions of racial/ethnic residents experience.

Objective.

Health disparities are pervasive in nursing homes (NHs), but disparities in NH end-of-life (EOL) care (i.e. hospital transfers, place of death, hospice use, palliative care, advance care planning) have not been comprehensively synthesized. We aim to identify differences in NH EOL care for racial/ethnic minority residents.

Design.

A systematic review guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses and registered in PROSPERO (CRD42020181792).

Setting and Participants.

Older NH residents who were terminally ill or approaching the EOL, including racial/ethnic minority NH residents.

Methods.

Four electronic databases were searched from 2010 to May 2020. Quality was assessed using the Newcastle Ottawa Scale.

Results.

18 articles were included, most (n=16) were good quality and most (n=15) used data through 2010. Studies varied in definitions and grouping of racial/ethnic minority residents. Four outcomes were identified: advance care planning (n=10), hospice (n=8), EOL hospitalizations (n=6), and pain management (n=1). Differences in EOL care were most apparent among NHs with higher proportions of Black residents. Racial/ethnic minority residents were less likely to complete advance directives. Although hospice use was mixed, Black residents were consistently less likely to use hospice before death. Hispanic and Black residents were more likely to experience an EOL hospitalization compared to non-Hispanic White residents. Racial/ethnic minority residents experienced worse pain and symptom management at the EOL; however, no articles studied specifics of palliative care (e.g., spiritual care).

Conclusions and Implications.

This review identified NH health disparities in advance care planning, EOL hospitalizations, and pain management for racial/ethnic minority residents. Research is needed that uses recent data, reflective of current NH demographic trends. To help reduce EOL disparities, language services and culturally competency training for staff should be available in NHs with higher proportions of racial/ethnic minorities.

Keywords: health disparities, end-of-life care, palliative care, nursing homes, quality of care

Introduction

Nursing homes (NHs) have become an eminent healthcare institution for end-of-life (EOL) care as approximately 25% of all deaths in the United States (U.S.) occur in this setting.1 The COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted the frailty and vulnerability of NH residents,2–4 who are often older adults, with multiple chronic conditions,5,6 and many are approaching the EOL.7

EOL care refers to the medical care and support provided in the time surrounding death.8 The EOL experience is unique and personal for each individual where most agree that they wish to avoid suffering during this time and others wish to prolong life at all costs.8 Authors of Dying in America,9 concluded that the primary goal of EOL care is to provide person-centered, family-oriented care, and provide comfort and maintain or improve quality of life. However, EOL care in the U.S. is often associated with aggressive treatments and increased physical and emotional suffering for patients and their families, particularly racial/ethnic minorities.8,9 For example, Black hospice residents have been found to be at higher risk of hospital admission and disenrollment from hospice care compared to White hospice residents.10 Hispanics are more likely to receive aggressive treatments at the EOL, such as ICU admission and mechanical ventilation, compared to White individuals.11–13 While the EOL experience needs to be improved for all, racial/ethnic groups are further disadvantaged, particularly those who are NH residents.9

The proportion of racial/ethnic minority NH residents is increasing compared to White NH residents who typically have access to more long-term care options.14 Racial/ethnic minority older adults often reside in NHs with higher concentrations of minority residents that tend to provide poorer quality of care.15–18 These NHs are often financially strained, Medicaid dependent, and with limited resources.15,16,19 While advance care planning engagement is poor in all NHs and over 25% of NH residents are admitted to hospitals every year, these rates are higher for racial/ethnic minority NH residents.20–22 NH EOL care remains suboptimal and NH segregation has been widely documented,16–18 which may have downstream impacts to disparities in NH EOL care.

Therefore, given the vulnerability of NH residents, the growth of racial/ethnic minorities in NHs, and the known disparities in NH care, it is imperative to understand if disparities in EOL care exist for these populations. However, a comprehensive synthesis on the current state of the science of NH EOL care health disparities has not been conducted. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review was to examine the differences in EOL care for racial/ethnic minority NH residents. Identifying the factors that influence the quality and type of services provided at EOL is necessary to guide efforts aimed at advancing health equity in NH EOL care.

Methods

Study Protocol and Registration

We developed a study protocol based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRIMSA) guidelines.23 The protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020181792) on July 5, 2020. The protocol can be accessed from https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020181792.

Study Eligibility

We included all peer-reviewed, English-language, observational studies in the U.S. that met the following criteria: 1) included NH residents, aged 60 or older, who were terminally ill or approaching the EOL; 2) included racial and/or ethnic minority NH residents (Blacks or African Americans, Hispanics or Latinos, American Indians or Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, and other Pacific Islanders24); 3) reported on differences in NH EOL care (i.e. hospital transfers, place of death, hospice use, palliative care, advance care planning) by NH resident race and/or ethnicity; 4) published from January 1, 2010 to May 22, 2020, to account for the growth of racial/ethnic minorities over the last decade. Case reports, duplicative papers, and not full text manuscripts (e.g., conference abstracts) were excluded.

Search Strategy

The search strategy was developed with assistance from the Columbia University Irving Medical Center Informationist and determined in terms of PICO (Population: older, seriously ill NH residents; Intervention/Exposure: race/ethnicity, Comparison: White NH residents, Outcome: EOL care). On May 22, 2020 the electronic systematic search was conducted in PubMed, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Embase. We used PubMed Medical Subject Headings, CINHAL subject headings, Embase Emtree search terms and keywords related to: 1) NHs, 2) EOL care, and 3) health disparities. An overview of the search strategy with the combination of search terms, keywords, and Boolean operators is available in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search Strategy

| Databases | PubMed CINAHL Embase |

|---|---|

| Terms Included | Keywords used per term |

| Palliative and end-of-life care | terminal care, hospices, hospice care, end of life, end of life care, palliative care, palliative supportive care, hospice utilization, hospice programs, hospice patients, terminally ill patients, hospitalization, burdensome transition, life-limiting, terminally ill, place of death, death, symptom management, pain management, palliative supportive therapy, palliative therapy, palliative treatment, hospice and palliative care nursing/standards, hospice and palliative care nursing/statistics and numerical data, hospice and palliative care nursing/trends, analgesia, patient-controlled, hospice and palliative nursing, advance care planning, advance health care plan, advance medical plan, advance healthcare plan, advance health-care plan, advance discussions, medical treatment orders, written advance directive, resuscitation orders, do-not-resuscitate orders, DNR, resuscitate order, do-not-hospitalize order, DNH, hospitalization order, living will, do not administer antibiotics order |

| AND | |

| Nursing homes | nursing homes, intermediate care facilities, skilled nursing facilities, homes for the aged, home for the aged, aged care facility, nursing home patients, nursing home residents, long term care facility, long-term care |

| AND | |

| Health disparities | racial disparities, race factors, race and ethnicity, racial and ethnic minorities, minority population, ethnic disparities, ethnic group, health disparities, health disparity, healthcare disparities, health care disparities, health care disparity, disparities in health, minority group, minority health, black, African Americans, Hispanic, Latin, Hispanic American, Asian, Asian American, Asian-Americans, Pacific islander |

| Filters | English and Spanish only January 1, 2010-May 22, 2020 United States |

Study Selection

Search results were imported into Covidence, a web-based platform for systematic reviews, that managed our study selection process. Study selection consisted of a two-step, independent screening process by two reviewers (LVE, MA). The first step was a title and abstract screening for article relevance and the second step was a full text screening of the remaining articles to determine eligibility based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any discrepancies were discussed at regular meetings to reach consensus on inclusion.

Data Extraction

A data extraction form was developed a priori and included the following variables: study aim, study design, setting, EOL definition (if any), how race/ethnicity was defined, sample size and characteristics, data sources, data analysis, variables, study outcomes and intended measures, and main findings related to racial/ethnic minority NH residents.

Methodological Quality Appraisal

Following data extraction, two reviewers independently appraised the methodological quality for included articles using the Newcastle Ottawa Scale.25 The Newcastle Ottawa Scale is designed to appraise cohort or case-control studies on three study domains, with a maximum score of 9: selection (maximum 4 points), comparability (maximum 2 points: study controlled for resident characteristics 1 point; study controlled for facility characteristics 1 point), and outcome (maximum 3 points). In order to score the overall quality of studies, we used the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) thresholds for converting Newcastle Ottawa Scale results as ‘good’, ‘fair’, and ‘poor’. A good quality study received 3 or 4 points in selection, 1 or 2 point in comparability, and 2 or 3 points in outcome. A fair quality study received 2 points in selection, 1 or 2 point in comparability, and 2 or 3 points in outcome. A poor quality study received 0 or 1 points in selection or 0 points in comparability or 0 or 1 points in outcome. Following independent appraisal by two reviewers, results were collectively discussed to settle discrepancies and reach consensus.

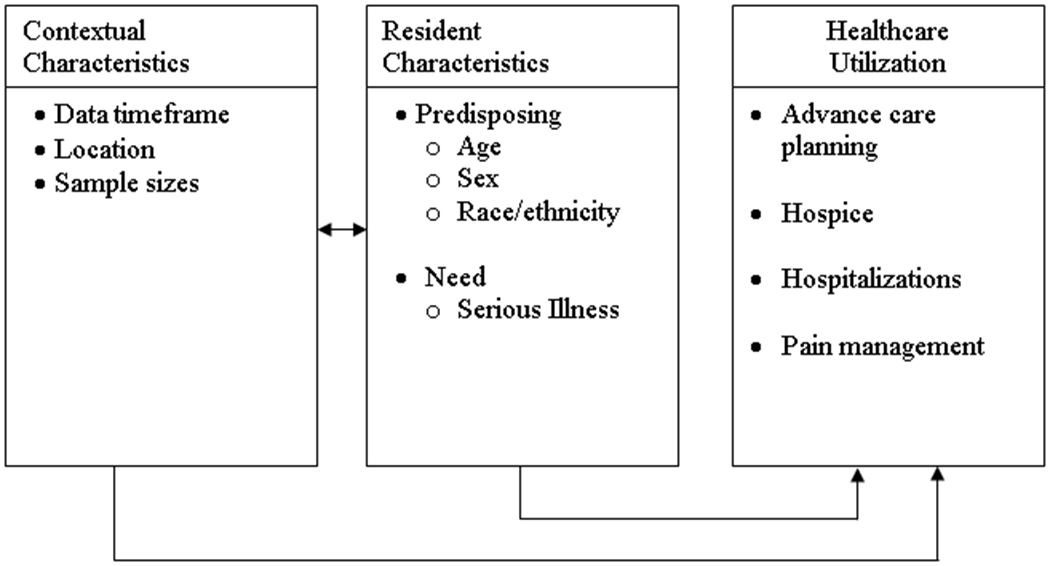

Conceptual Framework and Data Synthesis

The Gelberg-Andersen’s Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations26 guided the synthesis of results from this systematic review (Figure 1). This model is used to define and determine predictors of healthcare utilization. First, contextual characteristics of the NH facilities are presented. Second, NH resident characteristics from the included studies are presented. According to Gelberg-Andersen’s Behavioral Model,26 contextual and resident characteristics are associated with healthcare utilization.26 Third, healthcare utilization is conceptualized as NH EOL care, specifically for racial/ethnic minority NH residents. Study outcomes were categorized and presented across included articles into themes to identify patterns in EOL care for racial/ethnic minority NH residents.

Figure 1.

Adaptation of Gelberg-Andersen’s Model for Vulnerable Populations26 for Health Disparities in Nursing Home End-of-life care

Results

The electronic database search yielded 1,174 articles. First, after removing duplicates, 911 articles were screened in the first stage of title and abstract screening, based off the inclusion and exclusion criteria above. Next, the remaining 37 articles underwent full-text review, which resulted in 17 studies that were deemed eligible for inclusion. An additional article 27 was identified through an ascendency and descendency search for a final total of 18 included articles. Supplementary Figure 1 lists exclusions reasons during full-text review.

Table 2 presents a summary of the included studies. Six articles were specifically aimed at examining racial/ethnic health disparities in NHs.28–33 Four outcome themes were identified across included studies: 1) advance care planning,28–30,34–40 2) hospice use,29–31,33,41–43 3) EOL hospitalizations,27–30,33,44 and 4) pain management.32

Table 2.

Summary of Included Studies

| Contextual Characteristics | NH Resident Characteristics | Healthcare Utilization | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Aim | Health Disparities focus? | Data time frame | Location, number of facilities (if reported), sample size | Mean age (SD) in years | Sex | Serious Diagnoses/Chronic Conditions | Race/ethnicity demographics | How race/ethnicity was examined | Outcome Theme | Results |

| Araw et al. 2014 | To study the intervals between long-term care admission and AD completion, and between completion and death; and determine the interdisciplinary team’s compliance with documented wishes. |

----- | 2008-10 | New York 2 NHs N = 182 NH residents |

83.4(10) | Female = 68.6% Male = 31.3% |

AD/ADRD = 60.4% Cancer = 13.2% Heart diseases = 9.9% Stroke = 5.5% |

White = 91% Other (Black, Hispanic, Asian) = 9% |

White v. Other (Black, Hispanic, Asian) | Advance care planning | Median time from admission to AD completion was 21 days for Whites and 229 days for non-Whites. By first day of admission, 30% of Whites signed ADs compared to 12% of non-Whites. |

| Cai et al. 2016 | To examine whether the racial difference in end-of-life hospitalizations varies with: 1) the presence of ADs (DNH, DNR); and 2) different levels of cognitive impairment, among dying NH residents; and to examine the role of ADs in end-of-life hospitalizations. | Yes | 2007-10 | Nationwide N = 394,948 dual eligible, long-stay NH residents |

White: - no/mild cognitive impairment: 84.3(8.4) -moderate cognitive impairment: 86.2(7.8) -severe cognitive impairment: 86.0(7.7) Black: - no or mild cognitive impairment: 80.9(9.91) -moderate cognitive impairment: 83.8(8.8) -severe cognitive impairment: 84.2(8.5) |

Female = 71.6% Male = 28.4% |

AD/ADRD = 65.8% Cancer = 12.3% COPD = 30.5% Stroke = 26.9% |

White = 88.61% Black = 11.39% |

White v. Black | Advance care planning; Hospitalizations | EOL hospitalizations rates were higher for Blacks compared to Whites (43% v 32%, respectively). AD completion was lower among Blacks than Whites, and the racial differences increased with severity of cognitive impairment. ADs modified the racial differences in EOL hospitalizations. Without a DNH order, the probability of EOL hospitalization was higher for Black residents with moderate and severe cognitive impairment (p<0.01). With a DNH order, racial differences in EOL hospitalizations increased for those with no or mild cognitive impairment only (p=0.025). DNR orders significantly lowered EOL hospitalization likelihood for all dying NH residents (p<0.01), no significant differences for Black residents. |

| Frahm et al. 2012 | This study examined the relationship between race and ADs, hospice services, and hospitalization at the end-of-life among deceased NH residents. | Yes | 2007 | Nationwide N = 183,841 NH residents |

86.0 | Female = 71.8% Male = 28.2% |

AD/ADRD and Cancer = 29.5% AD/ADRD only = 8.8% Cancer only = 2.8% |

White = 88.6% Black = 7.9% Hispanic = 2.3% Asian = 1.0% |

White v. Black v. Hispanic v. Asian | Advance care planning; Hospice; Hospitalizations | Non-White NH residents were all significantly less likely to have any AD (health care power of attorney or living will, DNR or DNH order) compared to White residents (p<0.0001). Black and Asian residents were less likely to use hospice before death, although only significant odds for Asians compared to Whites (p<0.0001). Hispanic residents were more likely to use hospice in the year before death, compared to White residents (p<0.0001). Non-White residents were significantly more likely to be hospitalized during the last 90 days before death (p=0.0001), compared to White residents. |

| Frahm et al. 2015 | This study examined the relationship between race and ACP, hospitalization, and death among NH residents receiving hospice care. |

Yes | 2007 | Nationwide N = 88,416 hospice/NH residents |

85.5 | Female = 76.6% Male = 23.4% |

AD/ADRD and Cancer = 44.2% AD/ADRD only = 13.6% Cancer only = 4.8% |

White = 87.8% Black = 8.4% Hispanic = 3.1% Asian = 0.7% |

White v. Black v. Hispanic v. Asian | Advance care planning; Hospice; Hospitalization | Non-white NH residents were significantly less likely to have ACP (power of attorney for health care, living will, DNH or DNR order) in place (p<0.0001). Except for Asian residents who were more likely to have a DNH order compared to White residents (p<0.0001). Non-white NH residents were more likely to be hospitalized in the last 90 days of life, compared to White residents (p=0.0001). All non-White NH residents were less likely to die while receiving hospice (p≤0.0001). |

| Gozalo et al. 2011 | To examine health care transitions among NH residents with advanced cognitive impairment at the end-of-life. |

---- | 2000-07 | Nationwide N = 474,829 NH residents with cognitive impairment at the end-of-life |

85.7 (7.6) | Female = 78% Male = 22% |

Unstable cognition or ADL status = 43% Swallowing problem = 54% CPS of 6 = 82.1% |

White = 83% Black = 12% Hispanic = 3.3% Asian = 1.2% American Indian = 0.3% |

White v. Black v. Hispanic v. Asian v. American Indian | Hospitalizations | Black and Hispanic NH residents were more likely to have a burdensome transition (transfer in last 3 days of life, a lack of continuity of NH facilities before and after a hospitalization in the last 90 days of life, and multiple transitions in the last 90 days of life; adjusted RR = 1.24, 95% CI: 1.22-1.26; Adjusted RR = 1.24, CI:1.21-1.27; respectively). |

| Huskamp et al. 2010 | To identify characteristics of NHs and residents associated with particularly long (>180 days) or short hospice stays. | ---- | 2001-08 | Massachusetts, Connecticut, Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island 394 facilities N = 13,479 NH residents discharged from hospice either upon death or before |

% 71–80 = 14.0% 81–90 = 73.3% 91+ = 3.9% |

Female = 67.4% Male = 32.6% |

AD/ADRD = 34.5% Cancer = 19.1% Heart Disease = 8.8% Stroke = 4.0% |

White = 81.7% Black = 2.5% Hispanic = 1.0% Asian = 2.0% Other (nonwhite) = 12.8% |

White v. Black v. Hispanic v. Asian v. Other | Hospice | Black residents were less likely than White residents to have long hospice stays (OR=0.535; p=0.01). Black and Asian residents were less likely to have a stay of 3 or fewer days compared to White residents (OR=0.691; p=0.04 and 0.749, p=0.03, respectively). No significant findings related to Hispanics length of hospice stay. |

| Jennings et al. 2016 | To evaluate the use of POLST among California NH residents, including variation by resident characteristics and by NH facility. |

---- | 2011 | California 1,220 NHs in 2011 N = 289,753 NH residents |

77.6 (13.5) | Female = 61% Male = 39% |

No cognitive impairment = 51% Mild/moderate cognitive impairment = 15% Severe cognitive impairment = 34% ADL score 21 (most dependent) = 30% |

White = 67% Hispanic = 13% Black = 8% Asian = 8% Other/unknown = 4% |

White v. Black v. Hispanic v. Asian v. Other | Advance care planning | Compared to White residents, only Asian residents and other/unknown races were more likely to use POLST, regardless of length of stay (OR=1.05, 95% CI: 1.01-1.10; OR=1.07, 95% CI: 1.02-1.13). No racial/ethnic difference in POLST use among Hispanic and black residents compared to White residents. |

| Kiely et al. 2010 | To identify characteristics of NH residents with advanced dementia and their health care proxies associated with hospice referral; and examine the association between hospice use and 1) the treatment of pain and dyspnea, and 2) unmet needs during the last 7 days of life. |

---- | 2003-07 | Massachusetts 22 NHs in Boston N = 323 NH residents with advanced dementia and their healthcare proxies |

85.3 (7.5) | Female = 85.4% Male = 14.6% |

GDS score of 7 = 100% | White = 89.5% Black = 10.3% Asian = 0.3% |

White v. other (Black, Asian) | Hospice | Non-white resident race was associated with hospice referral (adjusted OR = 2.55; 95% CI: 1.36-4.76). Unmet needs during the last 7 days of life were not analyzed by race. |

| Lage et al. 2020 | To examine factors associated with potentially burdensome transitions between care settings among older adults with advanced cancer in NHs. | ---- | 2008-11 | Nationwide N = 34,670 NH residents with poor-prognosis solid tumors |

82.7(7.9) | Female = 62.7% Male = 37.3% |

Cancer = 100% Heart Disease = 29.3% COPD = 34.1% Moderate to severe cognitive impairment = 53.8% Complete ADL dependence = 66.5% |

White = 83.6% Black = 12.3% Hispanic = 1.6% Other/missing = 2.6% |

White v. Black V. Hispanic v. Other | Hospitalizations | Among residents not receiving hospice, Black (OR=1.21; 95% CI: 1.07-1.38; p<.01) and Other (OR=1.34; 95% CI: 1.12-1.61; p<.01) residents were more likely to be hospitalized in the last 90 days of life. |

| Lepore et al. 2011 | The aim of this study was to determine what factors, and what levels of factors (individual, NH, county), influence hospice use among urban Black and White NH decedents. |

Yes | 2006 | Nationwide 8,732 NHs with hospice contract N = 288,202 urban NH residents |

No hospice = 85.7(7.8) Hospice = 86.1(7.7) |

Female = 66.57% Male = 33.43% |

AD/ADRD = 29.5% Cancer = 8.1% CHF = 28.9% Stroke = 21.4% |

White = 91.3% Black = 8.7% |

White v. Black | Hospice | After controlling for interactions and covariates, and clustering of decedents in NHs and counties, the likelihood of Black resident hospice use is less than for White residents (adjusted OR=0.81, 95% CI: 0.77-0.86). Subgroups of Black used hospice at higher rates than whites. The odds of hospice use are 8% greater for Blacks with DNR orders, approximately 70% greater for Blacks with DNH orders, about 20% lower for Blacks with CHF, and approximately 15% greater for Blacks in low-tier NHs (compared to high-tier NHs). |

| Lu & Johantgen 2011 | The purpose of the study is to examine factors associated with do-not-resuscitate orders, do-not-hospitalize orders and hospice care in older NH residents at admission. | ---- | 2000 | Maryland 77 NHs N = 10,023 NH residents |

81.1 (7.9) | Female = 66.8% Male = 33.2% |

ADL score 8-21 (moderately independent) = 60.5% Organ failure (CHF, COPD, renal failure) = 38.6% AD/ADRD = 29.8% Cancer = 14.0% |

White = 78.7% Black = 19.5% American Indian/Alaskan Native = 0.1% Asia/Pacific Islander = 0.6% |

White v. non-White (Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaskan Native) | Advance care planning | White residents were consistently more likely to have DNR (adjusted OR=3.79, 95% CI: 2.80-5.14, p<0.01) or DNH (adjusted OR=2.51, 95% CI: 1.55-4.06) orders compared to non-White residents. Hospice associations were not analyzed by race/ethnicity. |

| Monroe & Carter 2010 | To explore the differences between Black and White NH residents’ pain management at the end of life. | Yes | 2003-09 | Tennessee 9 NHs N = 55 NH residents |

86.4 (7.84) | Female = 54.5% Male = 45.5% |

AD/ADRD and cancer = 100% | White = 71% Black = 29% |

White v. Black | Pain and symptom management | Black residents had a significantly higher DBS score compared to White residents (16 versus 39, respectively; p=0.0009, 95% CI: 1.93-12.61; Cohen’s d=0.67) |

| Mukamel et al. 2013 | To analyze resuscitation choices made by a national cohort of long-term NH residents. | ---- | 2003-07 | Nationwide N = 118,247 NH residents with ADs |

<65 = 5% 65-74 = 11.3% 75-84 = 36.2% 85 = 47.7% |

Female = 64.6% Male = 35.4% |

AD/ADRD = 48.1% | White = 89.4% Black = 6.8% Hispanic = 2.5% Other = 1.3% |

White v. Black v. Hispanic v. Other | Advance care planning |

Descriptive statistics revealed that Black, Hispanic, and Other residents more often are admitted with CPR orders compared to White residents who more often enter with DNR status. Black, Hispanic, and Other residents who were admitted with CPR status were less likely to convert to DNR status (p<0.010). Black residents who were admitted with DNR status were more likely to convert to CPR status (p<0.01). |

| Rahman et al. 2016 | To investigate the POLST preferences of NH residents in California. |

---- | 2012 | California 13 NHs in Southern California N = 941 NH residents |

65+ = 77.3% | Not reported |

Not reported | White = 61.4% Hispanic = 23.9% |

White v. Hispanic | Advance care planning | Residents in NHs with higher percentages of White, older (>65 years) residents had lower odds of electing aggressive treatment options (CPR, full care, long-term nutrition). Residents in NHs with higher percentages of Hispanic residents had higher odds of electing long-term nutrition, but no differences for CPR or full care. |

| Sterns & Miller 2011 | To understand how the characteristics of NH residents using hospice may have changed over time and examine how NH hospice characteristics and lengths of hospice stay differ among persons who died while in hospice depending on where they first entered hospice (i.e. in the community or in the NH). |

---- | 2006 (compared to 1992-96) | Kansas, Maine, Mississippi, New York, South Dakota N = 172,015 NH residents who received hospice care in the NH |

89.1 (9.3) | Female = 67.6% Male = 32.3% Missing = 0.1% |

AD/ADRD = 22.5% Stroke = 4.8% Cancer = 17.1% Heart failure = 7.9% COPD = 5.0% |

White = 89.1% Black = 7.3% Hispanic = 2.5% Other (native American, Asian, Pacific Islander) = 1.0% Missing = 0.2% |

White v. Black v. Hispanic v. Other | Hospice | In 2006, dying hospice residents were more racially diverse compared to dying hospice residents in 1992-96 (10% versus 6%, respectively). Non-white NH residents more often admitted to hospice prior to entering the NH compared to White residents who are more often admitted once in the NH. |

| Tjia et al. 2018 | To describe prevalence and content of AD documentation among NH residents by dementia stage (mild, moderate, advanced). | ---- | 2007-08 | Minnesota, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, California, Florida 3,371 NHs in 5 states N = 180,621 NH residents with dementia and an AD |

<80 = 25.2% 80–89 = 49.0% 90 + 25.7% |

Female = 72.7% Male = 27.3% |

Mild dementia = 22.1% Moderate dementia = 53.3% Severe dementia = 24.6% |

White = 80.4% Other (Black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaskan Native) = 19.6% |

White v. Black v. Hispanic v. Asian/Pacific Islander v. American Indian/Alaskan Native | Advance care planning | Black residents had the lowest odds of having an AD (adjusted OR=0.26, 95% CI: 0.25-27), followed by Hispanic residents (adjusted OR=0.35, 95% CI: 0.33-0.36), Asian/Pacific Islander (adjusted OR=0.46, 95% CI: 0.0.43-0.49), and American Indian/Alaskan Native residents (adjusted OR=0.57, 95% CI: 0.47-0.70). |

| Toles et al. 2018 | The purpose of this analysis was to describe current quality of communication between family decision-makers for persons with advanced dementia and NH staff and clinicians and the extent that characteristics of NH residents and decision makers were associated with their perceived quality of communication. | ---- | 2012-14 | North Carolina 22 NHs N= 302 English-speaking, family decision-makers of NH residents aged 65+, diagnosed with severe to very advanced dementia (stage 5-7 on GDS). |

86.5 (NH resident) 62.9 (family decision-maker) |

Female (family decision-maker) = 67.6% | GDS 5 = 24% GDS 7 = 26% |

Family decision maker: White = 86.7% Black = 12.6% Other = 0.7% |

White v. Black | Advance care planning | No significant association was identified between quality of communication between NH clinicians and NH resident race. *non-English was exclusion factor* |

| Zheng et al. 2011 | To examine whether the observed racial disparities in end-of-life care are due to within- or across-facility variations. | Yes | 2005-07 | NY 555 NHs N = 49,048 long stay NH residents |

White: 87.4(7.65) Black: 84(8.92) |

White female: 71.4% White male: 28.6% Black female: 63.5% Black male: 36.5% |

White mean ADL Score (0-28) = 21.0 White Asthma/COPD= 22.9% White cancer = 14.18% Black mean ADL Score (0-28) = 22.5 Black asthma/COPD = 18.2% Black cancer = 14.2% |

White = 90.8% Black = 9.2% |

White v. Black | Hospice; Hospitalizations | Racial disparities between facilities is a strong predictor of increased odds of in-hospital death (OR=1.22, 95% CI: 1.17-1.26) and decreased odds of hospice use (OR=0.85, 95% CI: 0.78-0.94) compared to Black and White residents within the same facility. In other words, all other conditions being equal, residents from facilities with higher concentration of Black residents have higher risk of in-hospital death and lower probability of using hospice compared to NHs with lower concentrations of Black residents. |

Note. AD = advance directive; NH = nursing home; AD/ADRD = Alzheimer’s disease and Alzheimer’s Disease Related Dementias; DNH = do not hospitalize; DNR = do not resuscitate; ACP = advance care planning; COPD = chronic pulmonary obstructive disorder; ADL = activities of daily living; CPS = Cognitive performance score, CPS score 6 indicates very severe cognitive impairment; RR = risk ratio; OR = odds ratio; POLST = Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment; GDS = Global Deterioration Scale, GDS score 7 is indicative of very severe cognitive defects, minimal verbal communication, total functional dependence, incontinence of urine and stool, and inability to ambulate independently; CHF = congestive heart failure; DBS = Discomfort Behavioral Scale.

Quality Appraisal

Table 3 presents the results from the quality appraisal for the 18 studies, which were all cohort studies. Most studies (n=16; 88.9%) were scored as good quality. Three studies (16.7%) were rated poor quality because they failed to compare cohorts.32,34,43 More specifically, these studies did not control for both facility and resident characteristics in their analyses.

Table 3 .

Quality Appraisal for Included Studies

| Cohort Studies | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selection | Comparability | Outcomes | Total | |||||||

| Study | Representativeness of exposed cohort | Selection of non-exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Outcome not present at the start of the study | Assessment of outcomes | Length of follow-up | Adequacy of follow-up | Max=9 | AHRQ rating | |

| Araw et al. 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | Poor |

| Cai et al. 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | Good |

| Frahm et al. 2012 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | Good |

| Frahm et al. 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | Good |

| Gozalo et al. 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | Good |

| Huskamp et al. 2010 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | Good |

| Jennings et al. 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | Good |

| Kiely et al. 2010 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 | Good |

| Lage et al. 2020 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Good |

| Lepore et al. 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | Good |

| Lu & Johantgen 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | Good |

| Monroe & Carter 2010 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | Poor |

| Mukamel et al. 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 8 | Good |

| Rahman et al. 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | Good |

| Sterns & Miller 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | Poor |

| Tjia et al. 2018 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | Good |

| Toles et al. 2018 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 | Good |

| Zheng et al. 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | Good |

Note. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) thresholds for the Newcastle-Ottawa scales follow: Good quality: 3 or 4 points in selection domain AND 1 or 2 points in comparability domain AND 2 or 3 points in outcome/exposure domain; Fair quality: 2 points in selection domain AND 1 or 2 points in comparability domain AND 2 or 3 points in outcome/exposure domain; Poor quality: 0 or 1 point in selection domain OR 0 points in comparability domain OR 0 or 1 points in outcome/exposure domain.

Contextual Characteristics

The data timeframe of the included studies ranged from the year 1992 to 2014. Most studies (n=15; 83.3%) used data prior up to 2010. Seven articles (38.9%) examined samples of NHs nationwide.27–31,33,44 The remaining articles looked at NHs from specific states or groups of states. Ten articles reported on the number of facilities in their sample, which ranged from 2 NH facilities34 to 8,732 NH facilities.31 The NH resident samples ranged from 55 residents32 to 474,829 residents.44

Resident Characteristics

NH residents mean age ranged from 80.028 to 89.1 years old.43 Two studies did not report on sex38,40 and among those that did, most residents were female (70.2%). One study did not report on the proportions of serious illness in NHs.38 Of those that did report on the residents’ serious illness, all reported on the concentrations of NH residents with Alzheimer’s Disease and Alzheimer’s related dementias (AD/ADRDs), followed by residents with cancer (n=11; 61.1%),27–31,33,34,36,41,43 residents with heart disease (n=6; 33.3%),27,31,34,36,41,43 residents who were stroke survivors (n=5; 27.8%),28,31,34,41,43 and residents with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n=5; 27.8%).27,28,33,36,43

The proportion of White NH residents ranged from 67%35 to 91%.31 Black NH residents were represented in 14 studies28–33,35–37,40–44 and proportions ranged from 2.5%41 to 29%.32 Hispanic NH residents were represented in 8 studies29,30,35,37,38,41,43,44 and proportions ranged from 1%41 to 23.9%.38 Asian NH residents were represented in 6 studies29,30,35,41,42,44 and proportions were mostly under 2%. American Indian,36,39,43,44 Asian/Pacific Islander,36,39,43 and Alaska Native36,39 NH residents were represented in fewer studies and in smaller proportions.

Although individual, facility-level racial/ethnic resident demographic proportions were reported, studies grouped racial/ethnic groups differently for analyses. For example, White residents were compared to “other/non-White” residents differently: 1) Araw et al.34 it was Black, Hispanic, and Asian residents; 2) Kiely et al.42 it was Black and Asian residents; 3) Lu & Johantgen36 it was Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, and American Indian/Alaskan Native residents; 4) five studies it was Black residents28,31–33,40; and 5) two studies it was Black, Hispanic, and Asian residents.29,30

Healthcare Utilization

Advance Care Planning.

Advance care planning was examined in ten articles.28–30,34–40 On average, White residents completed advance directives 21 days from NH admission compared to non-White residents who completed advance directives 229 days after admission.34 Advance directive completion was lower for racial/ethnic minority NH residents compared to White residents,29 particularly among Black residents and racial differences increased with cognitive impairment severity.28 Among NH residents with AD/ADRD and adjusting for resident characteristics, Black residents had the lowest odds of having an advance directive (adjusted OR=0.26, 95% CI: 0.25-27) compared to White residents.39

White residents were consistently more likely to have both do-not-resuscitate (adjusted OR=3.79, 95% CI: 2.80-5.14, p<0.01) and do-not-hospitalize (adjusted OR=2.51, 95% CI: 1.55-4.06) orders compared to non-White residents.36 In California NHs, only Asian (OR=1.05, 95% CI: 1.01-1.10) and other/unknown (OR=1.07, 95% CI: 1.02-1.13) residents were more likely to use POLST.35 Among NH residents receiving hospice care, one study found that Asian residents were more likely to have do-not-hospitalize orders compared to White residents (p<0.0001).30

A nationwide analysis of resuscitation choices among NH residents revealed that upon admission, Black and Hispanic residents more often expressed assent to future cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) compared to White residents who more often assented to do-not-resuscitate status.37 In this study, Black residents were 41.7% less likely to convert to do-not-resuscitate status, Hispanic residents were 27.7% less likely, and other groups were 22.4% less likely to convert their status, compared to White residents.37 Furthermore, Black residents who assented to do-not-resuscitate status upon NH admission were 47.4% more likely to convert to CPR status.37 In a study of 13 NHs in Southern California, residents in NHs with larger proportions of White residents had lower odds of elective aggressive treatments as opposed to residents in NHs with larger proportions of Hispanic residents who had higher odds of electing aggressive treatments.38

Toles et al.40 examined the quality of advance care planning communication. In a sample of 302 English-speaking only family members, of which 12.6% were Black, no significant associations were identified between quality of EOL care communication between NH staff and clinicians and NH resident race.40

Hospice.

Hospice use was examined in seven articles.29–31,33,41–43 In a comparison of hospice use from 1992-1996 to 2006, the racial diversity increased among dying hospice residents from 6% to 10%, respectively.43

A nationwide sample of NH residents receiving hospice care revealed that non-White (i.e., Black, Hispanic, and Asian) NH residents were less likely to die while receiving hospice (p≤0.0001).30 However, in another analysis by the same researchers, compared to White residents, Hispanic residents were more likely to use hospice in the year prior to death (p<0.0001).29 Similarly, a study of NH residents in 22 Boston-area NHs found non-White resident race was associated with increased hospice referral (adjusted OR=2.55; 95% CI: 1.36-4.76) compared to White resident race.42

Contrary, an analysis by proportion of Black residents found that NHs with high proportions of Black residents had lower probability of using hospice compared to NHs with lower proportions of Black residents.33 Race was found to be a strong predictor of decreased odds of hospice use within the same facility (OR=0.85, 95% CI: 0.78-0.94).33 Black NH residents were found to be less likely to have long hospice stays ( >180 days; OR=0.535; p=0.01).41 Among urban NHs with a hospice contract, the likelihood of Black residents using hospice was less compared to White residents (adjusted OR=0.81, 95% CI: 0.77-0.86).31 The odds of hospice use decreased by 20% for Black residents with congestive heart failure and 15% for Black residents in low-tier NHs compared to high-tier NHs.31 Notably, the odds of hospice use for Black residents increased by 8% with do-not-resuscitate status and approximately 70% with do-not-hospitalize order.31

EOL Hospitalizations.

EOL hospitalizations were examined in six articles.27–30,33,44 Nationwide samples of NH residents found that non-White (i.e., Black, Hispanic, and Asian) residents were significantly more likely (p=0.0001) to be hospitalized in the last 90 days before death compared to White residents29,30 and Black residents experienced more EOL hospitalizations compared to White residents.27,28 Similarly, Gozalo et al.44 found that Black and Hispanic NH residents were more likely to have a burdensome healthcare transition (e.g., hospitalization) in the last 90 days of life (adjusted RR=1.24, 95% CI: 1.22-1.26). Racial disparities between facilities resulted in increased odds of in-hospital death for Black and White residents within the same facility (OR=1.22, 95% CI: 1.17-1.26).33 NH residents in facilities with higher proportions of Black residents had a higher risk of in-hospital death compared to NHs with lower proportions of Black residents.33

In the presence of a do-not-hospitalize order, the probability of EOL hospitalization was higher for Black residents with moderate and severe cognitive impairment (p<0.01)28 and racial differences in EOL hospitalizations increased for those with no or mild cognitive impairment only (p=0.025), but no significant differences were found by race in the presence of do-not-resuscitate orders.28

Pain Management.

NH pain management was examined in one article.32 In a study of 9 NHs with a sample of 55 residents with both AD/ADRD and cancer, Black residents had significantly higher Discomfort Behavior Scale scores compared to White residents (16 vs. 39, respectively; p=0.0009), which is indicative of a higher prevalence of pain.32

Discussion

Prior evidence has confirmed that NH disparities exist in quality of care15,16,45 and our findings add to this by confirming these disparities are pervasive in EOL care as well. This systematic review identified 18 studies that demonstrated consistent racial/ethnic health disparities in NH EOL care and were mostly of good quality. Across studies, racial/ethnic minority NH residents had lower advance directive completion rates compared to White residents,28–30,35,36,39 more likely to be hospitalized at EOL,29,3028,44 and report more discomfort at EOL.32 Hospice use was mixed, but higher proportion of racial/ethnic minority residents was associated with decreased hospice use.31,33 Similarly, EOL care disparities overall increased as the proportion of racial/ethnic minorities increased within NHs.33,38

Racial/ethnic health disparities in NHs are multi-layered and include obstacles such as socioeconomic barriers, history of discrimination in health care, and cultural differences. For example, Black and Hispanic older adults have the highest poverty rates,46 which often result in fewer choices for NH selection and subsequent residence in low quality, Medicaid-dependent NHs. Many Medicaid-dependent NHs lack outside revenue to maximize necessary services such as staffing hours,47 which are associated with increased hospitalizations.48 Indeed, NHs with higher proportions of racial/ethnic minorities have reported lower registered nurse hours per resident day compared to NHs with lower proportions of racial/ethnic minorities.49 Given the extensive knowledge on NH segregation,45 it is critical for efforts aimed at reducing EOL care disparities to focus on Medicaid-dependent NHs.

Some of these differences in EOL care may be due to the history of mistrust of the medical establishment among racial/ethnic minorities, particularly in Black communities.50 Racial/ethnic minority older adults have reported discrimination and feeling valued “less” by physicians through subtle verbal and nonverbal actions of respect, such as active listening and amount of time spent.51 Furthermore, the NH workforce may not represent the NH resident population, compounding the mistrust due to cultural and language barriers.52,53 Clinicians have expressed difficulty in discussing advance care planning with racial/ethnic minorities and often have preconceived notions regarding their willingness to engage in these discussions.54 Clinician-patient trust has been reported to improve health outcomes55 therefore given the sensitive nature of EOL care, clinician trust is likely essential for delivery of high-quality EOL care.

EOL care is not a one-culture-fits all56–59 and resource allocation for language and ancillary support services and training for NH staff in cultural competence training is necessary. The differences in advance care planning highlight the need for more information to understand if advance care planning discussions in NHs were culturally competent and differed based on resident demographics. Increased training on culturally competent advance care planning discussions should be standard in nursing and medical schools, which have been effective at smaller scales.60 Furthermore, NH staff need to create safe spaces where residents can share their values and how best they want clinicians to communicate EOL care planning with them. Toles et al.40 included only “English-speaking” participants, therefore eliminating some racial/ethnic minorities. Research that aims to improve NH EOL care should increase efforts to include the perspectives of all racial/ethnic minorities and their EOL experience.

Palliative care has the potential to reduce EOL disparities for racial/ethnic minority residents, but is often unaddressed in NHs. Palliative care is essential in providing high-quality EOL care9 and includes management of pain and symptoms, caregiver support, and coordination of care.61 Racial/ethnic NH residents were disproportionately affected during the COVID-19 pandemic2 and palliative care guidelines could have relieved associated isolation and burdensome treatments associated with infection.62 Regardless, COVID-19 NH guidelines have focused primarily on infection prevention and not on palliative care.63 Although aspects of palliative care were identified in this review, not all aspects were measured nor was it comprehensively examined. A 2017 survey of palliative care in NHs nationwide found wide variation in palliative care services where over half of NHs nationwide would manage care without asking the healthcare proxy.64 Increased efforts to improve palliative care in NH could reduce disparities and improve EOL care.

The main strength of this review is the large number of included studies and the diverse sample populations from cohorts across the U.S. We followed the PRISMA guidelines to ensure rigor and quality appraisal assessments were completed independently by at least two reviewers. Most studies were of good quality adding to the quality of the science on health disparities in NH EOL care. However, limitations exist within our included studies. First, most studies were cross-sectional therefore limiting causal interpretations. Second, the sample sizes varied and some were quite small with only 55 subjects.32 Third, given the variation of sample sizes, locations (e.g., city vs. state vs. nationwide), and analyses based on race/ethnicity, it is difficult to create accurate generalizations and conclusions. Although most studies did control for facility and resident characteristics, therefore allowing some comparison of EOL care for racial/ethnic minority NH residents.

Conclusion and Implications

NH EOL is suboptimal in and NH health disparities are pervasive. We found that racial/ethnic minority NH residents experience poorer EOL care compared to White NH residents and particularly in NHs with larger proportions of Black residents.

This systematic review has several implications for care provision and future research regarding NH EOL care for racial/ethnic minority residents. First, 15 of 18 studies used data prior to 2010. Given the increased racial/ethnic diversity in NHs, data that reflect current NH demographic trends is needed. Second, more culturally competent work is needed to explore the experiences of racial/ethnic minorities at the EOL and identify the barriers to quality EOL care in NHs. Third, improvements to reduce, and ultimately eliminate, EOL care disparities will notably take time. This will require commitments from NH staff to understand and respect the cultural values of all residents and acknowledge the existing factors that have negatively impacted their EOL care experience for too long.

Supplementary Material

Sponsor’s role:

The sponsor did not play any role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis and preparation of this manuscript.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health (Grant number: R01 NR013687; Grant number: T32 NR014205). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank Gloria Willson for consultation in creating the search strategy.

Footnotes

SupplementaryFigure 1: PRISMA flow diagram

References

- 1.Bercovitz A, Decker FH, Jones A, Remsburg RE. End-of-life care in nursing homes: 2004 National Nursing Home Survey. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;(9):1–23. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/5146 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Y, Temkin-Greener H, Shan G, Cai X. COVID-19 infections and deaths among Connecticut nursing home residents: facility correlates. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(9):1899–1906. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Geriatrics Society. American Geriatrics Society Policy Brief: COVID-19 and nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(5):908–911. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fallon A, Dukelow T, Kennelly SP, Neill O. COVID-19 in nursing homes. QJM. 2020;113(6):391–392. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB. Dying with advanced dementia in the nursing home. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(3):321–326. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.3.321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Council on Aging. Healthy Aging Fact Sheet.; 2018. Accessed April 27, 2019. https://www.ncoa.org/wp-content/uploads/2018-Healthy-Aging-Fact-Sheet-7.10.18-1.pdf

- 7.Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services. Nursing Home Data Compendium 2015.; 2015. Accessed April 27, 2019. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/CertificationandComplianc/downloads/nursinghomedatacompendium_508-2015.pdf

- 8.Institute of Medicine. Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. (Field MJ, Cassel CK, eds.). National Academy Press; 1997. doi: 10.17226/5801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. National Academies Press (US); 2015. doi: 10.17226/18748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rizzuto J, Aldridge MD. Racial disparities in hospice outcomes: a race or hospice-level effect? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(2):407–413. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown CE, Engelberg RA, Sharma R, et al. Race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and healthcare intensity at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(9):1308–1316. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ornstein KA, Roth DL, Huang J, et al. Evaluation of racial disparities in hospice use and end-of-life treatment intensity in the REGARDS cohort. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2014639. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen C, Downer B, Chou L-N, Kuo Y-F, Raji M. End-of-life healthcare utilization of older Mexican Americans with and without a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. J Gerontol Ser A. 2020;75(2):326–332. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glz065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng Z, Fennell ML, Tyler DA, Clark M, Mor V. Growth of racial and ethnic minorities In US nursing homes driven by demographics and possible disparities in options. Health Aff. 2011;30(7):1358–1365. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y, Harrington C, Temkin-Greener H, et al. Deficiencies in care at nursing homes and racial & ethnic disparities across homes declined, 2006–11. Health Aff. 2015;34(7):1139–1146. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2015.1051611.INHALATION [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mor V, Zinn J, Angelelli J, Teno JM, Miller SC. Driven to tiers: socioeconomic and racial disparities in the quality of nursing home care. Milbank Q. 2004;82(2):227–256. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00309.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fennell ML, Feng Z, Clark MA, Mor V. Elderly Hispanics more likely to reside in poor-quality nursing homes. Health Aff. 2010;29(1):65–73. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rivera-Hernandez M, Kumar A, Epstein-Lubow G, Thomas KS. Disparities in nursing home use and quality among African American, Hispanic, and White Medicare residents with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. J Aging Health. Published online 2018:089826431876777. doi: 10.1177/0898264318767778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan Y, Louis C, Cabral H, Schneider JC, Ryan CM, Kazis LE. Socioeconomic and geographic disparities in accessing nursing homes with high star ratings. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(10):852–859.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reynolds KS, Hanson LC, Henderson M, Steinhauser KE. End-of-life care in nursing home settings: do race or age matter? Palliat Support Care. 2008;6(1):21–27. doi: 10.1017/S1478951508000047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mor V, Papandonatos G, Miller SC. End-of-life hospitalization for African American and non-Latino White nursing home residents: variation by race and a facility’s racial composition. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(1):58–68. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwak J, Haley WE, Chiriboga DA. Racial differences in hospice use and in-hospital death among medicare and medicaid dual-eligible nursing home residents. Gerontologist. 2008;48(1):32–41. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.1.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):1–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Institutes of Health. Racial and ethnic categories and definitions for NIH diversity programs and for other reporting purposes. Accessed July 22, 2020. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-15-089.html

- 25.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos PT M. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Accessed July 22, 2020. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- 26.Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res. 2000;34(6):1273–1302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lage DE, DuMontier C, Lee Y, et al. Potentially burdensome end-of-life transitions among nursing home residents with poor-prognosis cancer. Cancer. 2020;126(6):1322–1329. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cai S, Miller SC, Mukamel DB. Racial differences in hospitalizations of dying Medicare-Medicaid dually eligible nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(9):1798–1805. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frahm KA, Brown LM, Hyer K. Racial disparities in end-of-life planning and services for deceased nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(9):819.e7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frahm KA, Brown LM, Hyer K. Racial disparities in receipt of hospice services among nursing home residents. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2015;32(2):233–237. doi: 10.1177/1049909113511144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lepore MJ, Miller SC, Gozalo P. Hospice use among urban Black and White U.S. nursing home decedents in 2006. Gerontologist. 2011;51(2):251–260. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monroe TB, Carter MA. A retrospective pilot study of African-American and Caucasian nursing home residents with dementia who died from cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40(4 PG-1-3):e1–e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng NT, Mukamel DB, Caprio T, Cai S, Temkin-Greener H. Racial disparities in in-hospital death and hospice use among nursing home residents at the end of life. Med Care. 2011;49(11):992–998. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318236384e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Araw AC, Araw AM, Pekmezaris R, et al. Medical orders for life-sustaining treatment: is it time yet? Palliat Support Care. 2014;12(2):101–105. doi: 10.1017/S1478951512001010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jennings LA, Zingmond D, Louie R, et al. Use of the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment among California nursing home residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(10):1119–1126. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3728-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu C-Y, Johantgen M. Factors associated with treatment restriction orders and hospice in older nursing home residents. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(3-4):377–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03346.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mukamel DB, Ladd H, Temkin-Greener H. Stability of cardiopulmonary resuscitation and do-not-resuscitate orders among long-term nursing home residents. Med Care. 2013;51(8):666–672. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31829742b6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rahman AN, Bressette M, Gassoumis ZD, Enguidanos S. Nursing home residents’ preferences on Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment. Gerontologist. 2016;56(4):714–722. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tjia J, Dharmawardene M, Givens JL. Advance directives among nursing home residents with mild, moderate, and advanced dementia. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(1):16–21. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toles M, Song M-K, Lin F-C, Hanson LC. Perceptions of family decision-makers of nursing home residents with advanced dementia regarding the quality of communication around end-of-life care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(10):879–883. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huskamp HA, Stevenson DG, Grabowski DC, Brennan E, Keating NL. Long and short hospice stays among nursing home residents at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(8 PG-957-964):957–964. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kiely DK, Givens JL, Shaffer ML, Teno JM, Mitchell SL. Hospice use and outcomes in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(12 PG-2284–2291):2284–2291. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03185.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sterns S, Miller SC. Medicare hospice care in US nursing homes: a 2006 update. Palliat Med. 2011;25(4 PG-337-344):337–344. doi: 10.1177/0269216310389349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gozalo P, Teno JM, Mitchell SL, et al. End-of-life transitions among nursing home residents with cognitive issues. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(13 PG-1212-1221):1212–1221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1100347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mack DS, Jesdale BM, Ulbricht CM, Forrester SN, Michener PS, Lapane KL. Racial segregation across U.S. Nursing Homes: A systematic review of measurement and outcomes. Gerontologist. 2020;60(3):E218–E231. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Z, Dalaker J. Poverty among Americans Aged 65 and Older.; 2019. Accessed October 26, 2020. https://crsreports.congress.gov [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chisholm L, Weech-Maldonado R, Laberge A, Lin FC, Hyer K. Nursing home quality and financial performance: Does the racial composition of residents matter? Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6 PART1):2060–2080. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang BK, Carter MW, Trinkoff AM, Nelson HW. Nurse staffing and skill mix patterns in relation to resident care outcomes in US nursing homes [published online ahead of print, 2020 Oct 29]. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;S1525-8610(20):30792–1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Y, Harrington C, Mukamel DB, Cen X, Cai X, Temkin-Greener H. Nurse staffing hours at nursing homes with high concentrations of minority residents, 2001-11. Health Aff. 2015;34(12):2129–2137. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guerrero N, De Leon CFM, Evans DA, Jacobs EA. Determinants of trust in health care in an older population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(3):553–557. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hansen BR, Hodgson NA, Gitlin LN. It’s a matter of trust: older African Americans speak about their health care encounters. J Appl Gerontol. 2016;35(10):1058–1076. doi: 10.1177/0733464815570662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hughes MC, Vernon E. “We are here to assist all individuals who need hospice services”: hospices’ perspectives on improving access and inclusion for racial/ethnic minorities. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2020;6:233372142092041. doi: 10.1177/2333721420920414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Threapleton DE, Chung RY, Wong SYS, et al. Care toward the end of life in older populations and its implementation facilitators and barriers: a scoping review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(12):1000–1009.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ashana D, Reich A, Gupta A, et al. Clinician perspectives on barriers to advance care planning among vulnerable patients. Health Serv Res. 2020;55(S1):15–16. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13343 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Birkhäuer J, Gaab J, Kossowsky J, et al. Trust in the health care professional and health outcome: A meta-analysis. Nater UM, ed. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0170988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cain CL, Surbone A, Elk R, Kagawa-Singer M. Culture and palliative care: preferences, communication, meaning, and mutual decision making. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(5):1408–1419. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fishman J, O’Dwyer P, Lu HL, Henderson H, Asch DA, Casarett DJ. Race, treatment preferences, and hospice enrollment: eligibility criteria may exclude patients with the greatest needs for care. Cancer. 2009;115(3):689–697. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cagle JG, LaMantia MA, Williams SW, Pek J, Edwards LJ. Predictors of preference for hospice care among diverse older adults. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2016;33(6):574–584. doi: 10.1177/1049909115593936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lopresti MA, Dement F, Gold HT. End-of-life care for people with cancer from ethnic minority groups: a systematic review. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2016;33(3):291–305. doi: 10.1177/1049909114565658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spezia-Lindner NJ, Mitre V, Kunik ME. El intercambio cultural – a Hispanic culture and language immersion project in a nursing home. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(3):272–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.12.096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 4th ed. (Brandt K, ed.). National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care; 2018. Accessed October 14, 2019. https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/NCHPC-NCPGuidelines_4thED_web_FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fadul N, Elsayem AF, Bruera E. Integration of palliative care into COVID-19 pandemic planning. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020;0:1–5. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gilissen J, Pivodic L, Unroe KT, Van den Block L. International COVID-19 palliative care guidance for nursing homes leaves key themes unaddressed. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(2):e56–e69. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tark A, Estrada LV., Tresgallo ME, et al. Palliative care and infection management at end of life in nursing homes: A descriptive survey. Palliat Med. 2020;34(5):580–588. doi: 10.1177/0269216320902672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.