ABSTRACT

Background: Prevalence rates of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression are high among refugees in Germany. However, knowledge on subjective as well as objective need for psychotherapy and utilization of psychotherapeutic treatment is scarce. Both structural and personal barriers regarding utilization of mental health services must be addressed in order to increase treatment efficiency.

Objective: The aim of this study was to determine the objective as well as the perceived need for treatment, the utilization of mental health care among refugees in the past 12 months, and the perceived barriers to treatment.

Method: By means of face-to-face interviews, an unselected convenience sample of 177 adult refugees were interviewed in either Arabic, Farsi, Kurmancî, English, or German. The general sample was reached through social workers. In addition to the Refugee Health Screener-15 (RHS-15), utilization of psychotherapeutic and psychiatric care as well as the subjective needs and barriers to treatment were assessed.

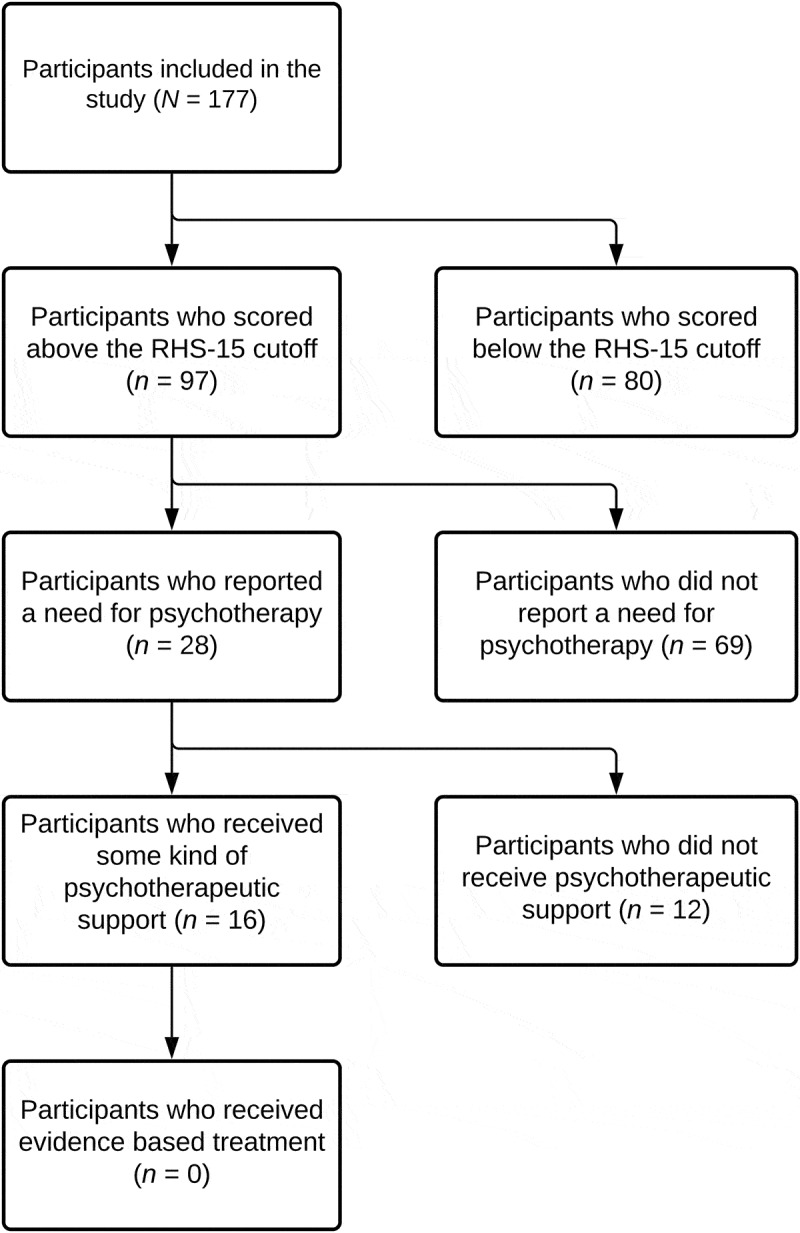

Results: According to the RHS-15 54.8% of participants (n = 97) suffered from relevant mental health problems. However, although 28 (28.9%) of the 97 participants who scored above the RHS-15 cut-off perceived a need for therapy, none of them had received psychotherapy as recommended by the German S3 Guidelines. Missing information about mental health and language difficulties were the most frequently cited barriers to mental health services.

Conclusions: Psychologically distressed refugees do not receive sufficient treatment. The reduction of barriers to treatment as well as extension of mental health services to lower thresholds should be considered in the future.

KEYWORDS: Refugees, mental health service utilization, barriers to treatment, asylum seekers, access

HIGHLIGHTS

There is a large gap between the number of refugees who are suffering from mental strain and the number who are actually getting treatment.

Besides conventional psychotherapy alternative approaches are needed to increase the availability and minimize (perceived) barriers to mental health service utilization.

Short abstract

Antecedentes: Las tasas de prevalencia de trastorno de estrés postraumático y depresión son elevadas en los refugiados en Alemania. Sin embargo, es escaso el conocimiento sobre la necesidad subjetiva y objetiva de acceder a psicoterapia y sobre el uso de tratamiento psicoterapéutico. Se deben abordar las barreras tanto estructurales como personales en relación al uso de servicios de salud mental para poder lograr aumentar la eficiencia del tratamiento.

Objetivo: El objetivo de este estudio fue determinar la necesidad objetiva y percibida de acceder a tratamiento, el uso de atenciones en salud mental entre los refugiados en los últimos 12 meses, y las barreras percibidas para acceder a tratamiento.

Método: Mediante entrevistas cara a cara, una muestra no seleccionada de conveniencia de 177 adultos refugiados fueron entrevistados en árabe, persa, kurdo del norte, inglés o alemán. La muestra general fue contactada mediante trabajadoras sociales. Adicionalmente al Tamizaje de Salud del Refugiado-15 (RHS-15 por sus siglas en inglés), se evaluó el uso de atenciones psiquiátricas y psicológicas, así como también las necesidades y barreras subjetivas para acceder a tratamiento.

Resultados: De acuerdo al RHS-15 el 54.8% de los participantes (n=97) sufría de problemas de salud mental relevantes. Sin embargo, aunque 28 (28.9%) de los 97 participantes que puntuaron sobre el corte de la RHS-15 percibían necesidad de terapia, ninguno de ellos había recibido psicoterapia como lo recomienda las Guías Alemanas S3. La falta de información sobre la salud mental y las dificultades idiomáticas fueron las barreras más frecuentemente mencionadas para acceder a servicios de salud mental.

Conclusiones: Los refugiados con dificultades psicológicas no reciben suficiente tratamiento. La reducción de las barreras al tratamiento y la extensión de servicios de salud mental para aumentar el acceso deben ser consideradas en el futuro.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Refugiados, uso de servicios de salud mental, barreras al tratamiento, solicitantes de asilo, acceso

Short abstract

背景: 德国难民中的创伤后应激障碍和抑郁患病率很高。但是, 对于心理治疗的主观和客观需求以及心理治疗使用了解很少。为了提高治疗效率, 必须解决在使用心理健康服务方面的结构性和个人性障碍。

目的: 本研究旨在确定对于治疗的目标和感知到的需求, 过去12个月中难民在心理健康保健中的使用情况以及感知到的治疗障碍。

方法: 以阿拉伯语, 波斯语, 库尔曼语, 英语或德语, 对未经选择的177名成年难民的便利样本进行了面对面的访谈。总样本是通过社会工作者获得的。除了难民健康筛查 (RHS-15) 以外, 还评估了心理治疗和精神病治疗的使用以及主观需求和治疗障碍。

结果: 根据RHS-15, 54.8%的参与者 (n = 97) 患有相关心理健康问题。然而, 尽管97名参与者中有超过RHS-15临界得分的28名参与者 (28.9%) 认为需要治疗, 他们均未按照德国S3指南的建议接受心理治疗。心理健康和语言障碍方面的信息缺失是心理健康服务中最常被提到的障碍。

结论: 心理上有困扰的难民没有得到足够的治疗。未来应考虑减少治疗障碍以及拓展心理健康服务使其门槛降低。

关键词: 难民, 心理健康服务使用, 治疗障碍, 寻求庇护者, 使用

1. Background

Psychological disorders are common within refugee populations, most frequently post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression (Steel et al., 2009; Steel, Silove, Bird, McGorry, & Mohan, 1999). Prevalence rates of PTSD vary between 16–55% (Bozorgmehr et al., 2016). In Germany, Gäbel and colleagues (Gäbel, Ruf, Schauer, Odenwald, & Neuner, 2006) found a prevalence of 40% for PTSD in a sample of asylum seekers. In a sample of Syrian citizens holding residence permits for Germany, 14.5% of the participants suffered from depression (Georgiadou, Zbidat, Schmitt, & Erim, 2018). In general, prevalence rates for depression in refugee populations vary between 11–54% (Lindert, Von Ehrenstein, Wehrwein, Brähler, & Schäfer, 2018). Elbert and colleagues (Elbert, Wilker, Schauer, & Neuner, 2017) estimated that more than half a million of the people who fled to Germany in 2016 suffered from PTSD. The heterogeneity of prevalence estimations among refugees can be attributed to population differences as well as the methodological limitations of studies, such as small sample sizes and, sometimes, the utilization of untested mental health questionnaires (Baron & Flory, 2018; Lindert et al., 2018). However, regardless of the heterogeneity of prevalence rates, it is evident that PTSD and depression are more common in refugee samples than in the host population (Bozorgmehr et al., 2016; Gäbel et al., 2006), as only 2.3% of people suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder and less than 8% present with depression in the population at large (12-month prevalence; (Jacobi et al., 2014)).

The comparatively high prevalence rates of PTSD and depression among refugees may be explained by trauma and other risk factors associated with flight. People who were forced to leave their home country are often confronted with potentially traumatic experiences before, during, and after flight (Schröder, Zok, & Faulbaum, 2018). Possible post-migration stressors, such as discrimination or lengthy asylum procedures in the host country can have additional negative influences on mental health (Chu, Keller, & Rasmussen, 2013; Li, Liddell, & Nickerson, 2016).

Symptoms of mental disorders can hinder efforts to learn a new language or to follow integration programmes (American Psychiatric Association, 2014; Elbert et al., 2017) and therefore the process of integration into a new country. Risk of chronification (BPtK–Bundespsychotherapeutenkammer, 2015) and the accompanying increasing burdens on the health system’s material, human, and financial resources (Bühring & Gießelmann, 2019) underscore the importance of treating symptoms of psychological disorders in a timely manner.

1.1. Psychotherapeutic care for refugees in Germany

In a systematic review, researcher noted that the use of psychotherapeutic care structures in many of the included studies is much lower than the actual rate of illness (Satinsky, Fuhr, Woodward, Sondorp, & Roberts, 2019). Structural and personal barriers are discussed as reasons for the low utilization.

Even in the general population in Germany, the need for psychotherapeutic care exceeds the supply (Baron & Flory, 2016). This imbalance is even more precipitous in the refugee population. According to the German S3 Guidelines (Schäfer et al., 2019) as well as international guidelines (e.g. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2018; Phoenix Australia–Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health, 2013) regarding PTSD treatment, people suffering from PTSD should be offered trauma-focused psychological treatment. The focus is supposed to be on processing the traumatic memories and/or their meanings (Schäfer et al., 2019).

Psychotherapy as recommended by the S3 Guidelines for the treatment of PTSD (Schäfer et al., 2019) often cannot be made available to all people in need. Besides a lack of available mental health providers, additional organizational and financial expenditures play a major role, for example as the result of additional costs due to the need for interpreters (Bühring & Gießelmann, 2019; Elbert et al., 2017). Moreover, uncertainty about foreign cultures as well as structural difficulties may aggravate the work of psychotherapists in outpatient care (Baron & Flory, 2019). Compared to the general population, requests for psychotherapy for people without recognized residence status is complicated and, as a result, the coverage of costs often remains uncertain (Demir, Reich, & Mewes, 2016). Usually, during the first 18 months in Germany, refugees without recognized residence status need a health care voucher to be able to receive psychotherapeutic treatment. During this timeframe the matter of financial coverage of interpreter costs is often unclear, and the application process to access those services is time-consuming. After these 18 months, refugees change into the regular care system and have the same access to the health care system compared to the population at large. Financial coverage of interpreter costs is then no longer provided. Additionally, according to the Asylum Seeker Benefits Act (Asylbewerberleistungsgesetz, AsylblG) there is no entitlement to treatment of chronic illnesses, which makes adequate treatment of mental illnesses even more difficult.

In addition to registered individual psychotherapists, 41 psychosocial centres for refugees and torture victims in Germany provide psychosocial and mental health care for refugees (as of January 2019; (Baron & Flory, 2019)). However, the typical waiting time for treatment in psychosocial centres in 2017 was up to one and a half years in some regions of Germany, even for severely traumatized refugees. The average waiting time for a psychotherapy was six months (Baron & Flory, 2018).

1.2. Barriers to psychotherapeutic care

In addition to the difficult conditions facing the supply side, there are also barriers facing the people who are in need (Bajbouj, 2016). Fear of exclusion, stigmatization, and feelings of shame were cited as the most prominent barriers to seeking psychotherapeutic care for trauma survivors (Kantor, Knefel, & Lueger-Schuster, 2017). The influence of fear of stigmatization on the decision to seek psychotherapeutic support is also described in a review by Clement and colleagues (Clement et al., 2015). Chowdhury (Chowdhury, 2016) points out that use of psychotherapeutic care is still widely seen as weakness and failure in the Arabic-speaking world and seeking support from family and close friends is preferred.

Lack of knowledge about mental health (Bajbouj, 2016), such as knowledge of the relationship between traumatic experiences and physical and non-specific symptoms like headaches, difficulty concentrating, and sleep disorders (Chikovani et al., 2015) are additional barriers. In these cases, patients suffering from mental disorders often seek advice from a general practitioner instead of psychotherapists (Chikovani et al., 2015; Kirmayer, 2001).

Another significant barrier faced by refugee populations seeking mental health support is a potential lack of sufficient language skills. The inability to communicate in the language of the host context can make the acquisition of knowledge about possible support and therapy possibilities difficult (Bajbouj, 2016; Demir et al., 2016; Lamkaddem et al., 2014). Moreover, in Germany interpreters for psychotherapies are not paid by the public health insurance if the persons concerned changed into the regular care system and therefore have the same access to health care compared to the population at large. As a result, therapy cannot be provided if the people seeking mental health support do not yet speak German sufficiently to comprehend treatment (Bühring & Gießelmann, 2019). Besides these barriers, negative prejudices about psychotherapy in general persist, which makes it less likely to be used. For example, in a semi-structured interview with a sample of traumatized migrants, respondents indicated, among other things, that people who are in psychotherapy are sometimes described as crazy in their home country (Maier & Straub, 2011).

1.3. Aim of the study

Based on the varying prevalence rates of mental disorders in refugee populations, the aim of this study is to document how many of the interviewed people in a region of North Rhine-Westphalia show symptoms of psychopathology and therefore may be in need of psychotherapeutic support. In order to be able to examine whether assessed symptom severity corresponds to subjective estimates of need for psychotherapeutic care, participants were asked for their appraisal of their needs for psychotherapeutic care. In addition, we sought to determine how many participants were seen by a psychotherapist and/or psychiatrist within the past year. Lastly, for people who indicated need but did not receive care, the aim of this study is to map possible obstacles so that these can be taken into account in future care plans.

2. Method

2.1. Sample

A total of 198 refugees (23.2% female; n = 46) participated in the study. Participants ranged from 18 to 75 years of age (M = 33.03, SD = 11.02). Inclusion criteria were: being at or above the age of majority, residence in North Rhine-Westphalia, possessing language skills sufficient to provide informed consent and conduct the interview in Arabic, Farsi, Kurmancî, English, or German. In addition, potential participants had to have arrived in Germany within the previous six years.

2.2. Procedure

The study presented is part of a larger study on refugee mental health and was conducted within the framework of the research consortium ‘FlüGe–Opportunities and challenges that global refugee migration presents for health care in Germany’. This graduate school programme was funded by the Ministry of Culture and Science of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia. Thirteen paraprofessional interviewers (12 male, 1 female; 9 fluent in Arabic, 4 fluent in Kurmancî, 3 fluent in Farsi) were trained and selected on the basis of face-to-face interviews. Informed consent forms, information letters, and the questionnaire were translated by a professional translation agency and the native speakers. Blind back-translations guaranteed correct translation.

Face-to-face interviews took place between February 2018 and August 2018. The unselected convenience sample was reached through contact with social workers who have been working in a region in the north-east of North Rhine-Westphalia and made contact with several shared accommodations. Interviews were carried out in shared accommodation facilities,private apartments, as well as in Bielefeld University. Prior to the interviews, meetings with refugees were organized in seven shared accommodations to provide information about the aims and procedure of the study. These meetings were the first opportunity to make interview appointments. Further appointments were arranged over time by asking people present in the shared accommodations and apartment buildings and via snowball sampling.

Field-teams consisted of two researchers and the trained interviewers in the required languages. The face-to-face interviews lasted 90 minutes on average (SD = 31.9). No financial compensation was provided for the respondents’ participation. The Ethical Review Board of Bielefeld University granted approval for the study.

2.3. Measures

The following sociodemographic variables were collected: age, gender, country of origin, citizenship, native language, education, profession in home country, current occupational situation, current financial situation, and marital status. In addition, participants were also asked for the length of time since their arrival in Germany, residence status, Table 1and potentially traumatic event types experienced (see Table 2). Instruments used in this study’s analyses assessing mental stress and (barriers to) use of psychotherapeutic services are explained below in detail.

Table 1.

Possible barriers to treatment

| “Please indicate the extent to which the following statements apply to you. I have found it hard to use the range of services available in the German healthcare system because … |

|---|

| … I don’t have enough information about them.” |

| … the medical personnel don’t speak my language.” |

| … I have the feeling that I’m not taken seriously.” |

| … I’m looking for help within my social surroundings.” |

| … I’m scared of being excluded or ostracized.” |

| … I don’t know how to get to the doctor/psychotherapist.” |

| … I can’t get a medical certificate/health care voucher.” |

| … I haven’t been granted treatment.” |

| … I’m scared of the ramifications regarding my residency status.” |

Note: Answers were given on a 5-point Likert scale (not applicable at all–very applicable).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of all demographic variables

| Total sample (N = 177) | Subsample above RHS-15 cut-off (n = 97) | Subsample below RHS-15 cut-off (n = 80) | t-testd/ Chi-square teste/ Fisher’s exact testf | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | ||||

| M (SD) | 33.10 (11.18) | 33.66 (10.67) | 32.26 (11.83) | −0.912 |

| Range | 18–75 | 19–63 | 18–75 | |

| Gender (female) | ||||

| n (%) | 36 (20.3) | 25 (25.8) | 11 (13.8) | 4.052* |

| Formal education | 4.745 | |||

| n (%) | ||||

| Dropped out of school without certificate | 41 (23.2) | 24 (24.5) | 17 (21.3) | |

| Primary graduation | 34 (19.2) | 24 (24.5) | 11 (13.8) | |

| Higher school-leaving qualificationa | 101 (57.0) | 50 (51.1) | 51 (63.6) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.3) | |

| Higher educationb | ||||

| n (%) | 37 (20.9) | 19 (19.6) | 18 (22.5) | 0.946 |

| Marital status n (%) | ||||

| In a stable partnership (married orunmarried) | 107 (60.5) | 57 (58.5) | 50 (62.6) | 0.016 |

| Citizenship (multiple answers possible) | 6.197 | |||

| n (%) | ||||

| Syria | 75 (42.4) | 34 (35.1) | 41 (51.2) | |

| Iraq | 47 (26.6) | 27 (27.8) | 20 (25.0) | |

| Afghanistan | 16 (9.0) | 12 (12.4) | 4 (5.0) | |

| Other | 39 (22.0) | 24 (24.7) | 15 (18.8) | |

| Time since arrival in Germany in months | ||||

| M (SD) | 28.46 (9.96) | 28.29 (9.33) | 28.66 (10.73) | 0.239 |

| Range | 1–63 | 3–54 | 1–63 | |

| Residence status (securec) | ||||

| n (%) | 119 (67.2) | 55 (56.7) | 64 (80.0) | 11.641*** |

| Potentially traumatic event types | ||||

| M (SD) | 6.97 (3.56) | 7.72 (3.53) | 6.05 (3.38) | −3.193** |

| Refugee Health Screener-15 (Question 1–14) M (SD) | 15.61(10.92) | 23.11 (9.21) | 6.51 (3.13) | −16.633*** |

aSecondary school certificate, high school graduation

bDiploma, bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, PhD, postdoctoral qualification

csecure residence status: recognized as refugee, entitled to asylum, subsidiary protection; insecure residence status: asylum applicant with pending procedure, temporary suspension of deportation, demand to leave Germany

dα-values adjusted according to Bonferroni-Holm-procedure.

ep-values of the Chi-square test are italic.

fp-values of Fisher’s exact test are bold.

% figures rounded to one decimal place.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

2.3.1. Refugee Health Screener-15

The Refugee Health Screener-15 (RHS-15; (Hollifield et al., 2013)) consists of 15 questions assessing mental stress in refugees. Based on 13 questions, the presence of various symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD during the previous month is assessed. Answers are given on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 4 = extremely). Question 14 assesses respondents’ general coping capacities. Question 15 provides a ‘distress thermometer’ where participants indicate how much suffering they experienced during the previous week on a scale of 0–10. The instrument has been used in numerous studies and its effectiveness, validity, and reliability have been demonstrated (Hollifield et al., 2016, 2013; Kaltenbach, Härdtner, Hermenau, Schauer, & Elbert, 2017). Kaltenbach and colleagues (Kaltenbach et al., 2017) compared different versions of the RHS and found excellent internal consistency values with a Cronbach’s α between .91–.93. In our sample a Cronbach’s α of .87 was found. The cut-off criterion for the definition of a case requiring mental health treatment recommended by Hollifield and colleagues (Hollifield et al., 2013) is a sum score of ≥ 12 regarding questions 1–14 and/or a score of ≥ 5 regarding the distress thermometer. For a cut-off ≥ 12 regarding questions 1–14 Hollifield and colleagues (Hollifield et al., 2013) reported sensitivity of = .81 and specificity of = .87 for PTSD.

2.3.2. (Barriers to) use of psychotherapeutic services

The number of visits to psychotherapists and psychiatrists in the past 12 months was recorded (‘How often have you been to a psychiatrist during the past twelve months?’; ‘How often have you been to a psychotherapist during the past twelve months?’). According to international guidelines, including the German guideline for the treatment of PTSD (Schäfer et al., 2019), the first line treatment for PTSD consists of trauma-focused psychotherapy, with a minimum duration of 12 sessions. Subsequently, it was asked whether the participant subjectively ever needed psychotherapeutic help in Germany (‘Have you ever needed psychotherapeutic help in Germany?’). If this question was affirmed, participants were asked whether or not he or she had received the necessary help (‘Have you ever needed psychotherapeutic help and not received any?’). If no help was received, possible barriers were determined via a set of nine questions which were composed on the basis of previous studies (e.g. Bermejo, Hölzel, Kriston, & Härter, 2012), participatory observations that had been conducted in two different psychiatric outpatient clinics before drawing up the questionnaire (results not published yet), and on the basis of the current legal situation regarding health care for refugees in Germany (see Table 1 for all items). Questions regarding barriers to utilization were answered on a 5-point Likert scale (not applicable at all–very applicable).

2.4. Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics Version 26 for macOS. In total, 21 participants were excluded due to ≥ 10% missing data on the RHS-15. Regarding cases with < 10% missing values on the RHS-15, values were set equal to 0. Different two-tailed statistical tests with an alpha level set at 0.05 were used to investigate possible differences between the subsamples. Independent t-tests were conducted for continuous variables and a-values were adjusted according to the Bonferroni-Holm-procedure. Chi-square tests were calculated for possible group differences regarding categorical variables. Fisher’s exact test was calculated in cases where there were less than five participants per category.

3. Results

The 177 participants (n = 36 (20.3%) female) were, on average, 33 years old (SD = 11.21). The largest proportion of participants came from Syria (n = 75, 42.4%), followed by n = 47 (26.6%) from Iraq, and n = 16 (9%) from Afghanistan. Participants arrived in Germany on average 28.5 months ago (SD = 9.96). A secure status of residency was reported by n = 119 (67.2%) of the participants (see Table 2 for all descriptive data).

3.1. Use and barriers to the use of psychotherapeutic services

Although slightly more than half of the participants (n = 97, 54.8%) scored above the cut-off on the RHS-15, 35 participants (19.8%) endorsed having a subjective need for psychotherapeutic care. Comparing the two subsamples, the proportion of female participants was significantly higher in the subsample above the RHS-15 cut-off (χ2 (1, N = 176) = 4.05, p = .044). A total of 17 participants (9.6%; 14 above the RHS-15 cut-off) stated having had at least one appointment with a psychiatrist in the past 12 months. Eight participants (4.5%; five above the RHS-15 cut-off) endorsed having had appointments with psychotherapists in the past 12 months. Two of those (1.1% of the total sample), both above the RHS-15 cut-off, stated having had more than 5 psychotherapy sessions (maximum 7 sessions). None of the participants reported having received evidence-based treatment. People with an insecure asylum status reported significantly more contact with psychiatrists during the past 12 months (t(54.33) = −2.13, p = .037) and they indicated significantly more often, that they felt a need for psychotherapeutic treatment (t(97.45) = 2.54, p = .013). Other differences regarding the utilization were not found regarding asylum status. In the subsample above the RHS-15 cut-off, 28.9% (n = 28), and in the subsample below the cut-off, 8.8% (n = 7) of the participants, stated that they needed psychotherapeutic help. None of the participants with subjective needs and values above the cut-off received psychotherapeutic support as recommended by the guidelines (see Figure 1 for an overview).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participants included in the analyses

A total of nine different barriers to use were surveyed among the participants who stated not having received psychotherapeutic care despite need (see Table 3 for all descriptive data).

Table 3.

Perceived barriers regarding mental health care utilization

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Treatment was not granted | 1 (12.5) |

| Fear of consequences of residence law | 2 (16.7) |

| No health care voucher | 3 (25.0) |

| Seeking help in the social environment | 4 (33.3) |

| No knowledge how to get to a doctor/psychotherapist | 5 (41.7) |

| Fear of exclusion | 6 (50.0) |

| Fear of not being taken seriously | 6 (50.0) |

| Language difficulties | 9 (75.0) |

| Missing information | 9 (75.0) |

Note: Barriers (if answered with ‘is partially applicable’/”is more applicable”/”is very applicable”) regarding the use of psychotherapeutic services in the subsample of people stating not having received psychotherapeutic help despite perceived need (n = 12). Scale: 1 (not applicable)–5 (very applicable).

4. Discussion

4.1. Health care utilization

Of the 177 participants, n = 97 (54.8%) scored above the RHS-15 cut-off, but only n = 35 people (19.8%) of the total sample (n = 28 above the RHS-15 cut-off) reported a subjective need for psychotherapeutic help. The subjective perception of not needing psychotherapeutic help despite reported symptoms is known to be one of the barriers to the use of psychotherapeutic care (Kivelitz, Watzke, Schulz, Härter, & Melchior, 2015). To be able to correctly assess one’s personal need for psychotherapy, sufficient information about the link between somatic symptoms and mental illness as well as treatment options needs to be accessible.

The fact that significantly more participants stated having contact with psychiatrists in the past year than with psychotherapists supports earlier research, concluding that physicians (e.g. psychiatrists) are still visited more frequently than psychotherapists for mental health problems (Laban, Gernaat, Komproe, & De Jong, 2007). Generally speaking, this aspect could also be explained by lack of knowledge about connections between traumatic experiences and somatic symptoms (Chikovani et al., 2015). However, as this kind of knowledge was not assessed in detail in the current sample, this explanation remains speculative.

By contrast, the discrepancy may also be explained by resilience some of the participants developed on the basis of cruel experiences. In a review by Galatzer-Levy, Huang, and Bonanno (Galatzer-Levy, Huang, & Bonanno, 2018) resilience was the most common response to major life stressors and potentially traumatic events. Following that, some of our participants simply might not have felt a need for psychotherapeutic treatment despite reporting several mental health symptoms because of resilience. Moreover, it needs to be kept in mind that the RHS-15 is a screening instrument that only indicates a direction for mental illness. To be able to diagnose potential mental health diseases clinician-rated instruments are needed. In addition to contact with psychotherapists and/or psychiatrists, contact with allied health care providers, like social workers, should be assessed in future studies to get a more general impression of the mental health care situation. Despite everything, it can be stated that none of the participants who indicated a need for psychotherapeutic help, reported having received adequate help, meaning psychotherapy as described in the guidelines for evidence-based therapy with a minimum of 12 sessions.

The number of people who endorsed not receiving psychotherapeutic help despite being in need of it and those who endorsed having received help do not add up to the total number of people who indicated being in need of psychotherapeutic care. This indicates that visits to psychiatrists may also have been interpreted as psychotherapeutic support by the participants.

The larger proportion of female participants in the subsample above the RHS-15 cut-off matches earlier research that states a higher chance for women to develop a PTSD or a depression (Jacobi et al., 2014). To be able to accurately investigate gender differences regarding the other results reported a more equal gender ratio would be needed. On the basis of the available results, no gender differences can be assumed.

Our findings indicate that mental health symptoms are probably associated with barriers to help-seeking. While all participants who scored below the RHS-15 cut-off and stated a need for psychotherapeutic care reported that they had received support through single sessions with a psychotherapist, 42.9% (n = 12) of those who scored above the cut-off and perceived a need for treatment did not receive any help. One possible explanation may be that people above the cut-off are more restricted in their everyday life due to their symptoms and thus less able to seek support. If this is true, the symptom severity itself might be part of the barrier. In that case, the necessity for education and information as well as screening for mental health problems after the arrival in Germany becomes vital. Lastly, each individuals’ decisions, motivation, and coping abilities needs to be taken into account.

4.2. Handling of barriers regarding health care utilization

The barriers were assessed in the subsample of twelve participants who reported a need for psychotherapeutic treatment but did not receive any support. Lack of information about mental health (Bajbouj, 2016) was indicated as barrier to health care utilization by three quarters of the participants (n = 9) in this subsample. In addition, 42.5% of the participants (n = 5) stated that they do not know how to get to a doctor and/or psychotherapist. Thus, psychoeducation regarding mental health as well as information about the health care system are essential here. Early contact with language and cultural mediators can be helpful here. A similar cultural background can make it easier to ask questions and exchange information (Kirmayer, 2001).

Half of the respondents (n = 6, 50%) were afraid of social exclusion resulting from their visiting a psychotherapist. This fear was highlighted as an important barrier by Kantor and colleagues (Kantor et al., 2017) as well. Chowdhury (Chowdhury, 2016) reiterates that people from the Arabic-speaking world often ask family for advice because visits to a psychiatrist are still connected to feelings of weakness and failure. In our study, 33.3% of respondents (n = 4) who did not receive help despite needing it said they sought help within their social network. However, as no causal relationships can be made, it remains an associative relationship. Again, psychoeducation may help to reduce fears and break down barriers. The same is true for fear of consequences in terms of residence law (feared by n = 2 (16.7%) of the respondents in this sample).

The feeling of not being taken seriously was seen as an obstacle by half of the participants. Future studies should investigate the directionality of this concern for potential patients. Is it towards physicians, psychotherapists, or other groups? Irrespective of this, a better understanding of disorders could help those affected to stand up for their needs (e.g. knowing that mental disorders can be a natural consequence of experiencing a potentially traumatic event may lower the fear of being considered crazy and therefore strengthen the person to ask for help).

Apart from the barrier of lack of information, language barriers were the most frequently-cited impediment to accessing care. In this sample 75% of the participants (n = 9) who did not receive psychotherapeutic help despite subjective need indicated language difficulties as a barrier for mental health care use. These findings align with previous research findings (Bajbouj, 2016; Demir et al., 2016; Lamkaddem et al., 2014). It is essential that language mediators are made available and that relevant costs are covered.

For one (8.3%) participant in our sample treatment was not approved by the health insurance funds and three (25%) did not receive a health care voucher. In these cases, we do not know what led to the rejection or the missing health care voucher. Perhaps more knowledge about psychological problems on the part of decision-makers or providing extended support by interpreters could have reduced these barriers.

4.3. Strength and limitations

Considering the sample is an unselected convenience sample, results cannot be generalized. Even though participants were not purposefully selected, self-selection factors in potential participants may have played a role. The sample was collected locally in a region in the north-east of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. Therefore, it is important to consider whether regional differences in mental health care, such as differing availability of interpreters, may have had an effect on the results. Moreover, only participants who could answer the questions in Arabic, Kurmancî, Farsi, English, or German were included. Nevertheless, the fact that we recruited a sample with a considerable variance in all parameters does encourage us not to overrate selection factors. The similarity of our sample regarding previous findings on mental health in refugees (Kaltenbach et al., 2017) supports this view. And even though we cannot rule out selection factors in any direction, the finding that not a single participant reported regular treatment despite a high objective and some subjective need in this population remains difficult to explain on the basis of self-selection.

The number of people who answered the questions regarding possible barriers is small compared to the entire sample. In further studies, all participants should be asked about possible barriers in order to get answers from participants who said they received psychotherapeutic help as well as from those who said they do not need help at the moment.

Since the RHS-15 was the only instrument used to assess mental stress, not all facets of mental health were assessed. Further, as the answers are self-report, it is possible that, despite individual explanations during the interview, visits to a psychiatrist were confused with visits to a psychotherapist. In the future, long waiting times for a treatment should also be acknowledged as a possible barrier to accessing psychotherapeutic services. Wait times for trauma-focused therapies in Germany are generally long (Elbert et al., 2017).

Subjective assessment of participants’ need for psychotherapeutic care is a strength of this study. It allows comparison between the results reported in the screening questionnaire and the participants’ own assessment of their need for psychotherapeutic help.

4.4. Recommendations

The results of this study underline previous findings regarding the large number of mentally stressed refugees. It is well-recognized that untreated mental illnesses can become chronic (BPtK–Bundespsychotherapeutenkammer, 2015). Thus, timely treatment is important. This is especially the case for people who have experienced a high number of potentially traumatic events. Kolassa and colleagues (Kolassa et al., 2010) showed that spontaneous remission rate decreases with an increasing number of experienced events while the (severity of) symptoms increases. In addition, there is a high probability that people suffering from PTSD who get treatment experience an increase of quality of life and are better able to participate in daily life in the host country (Jongedijk, 2014). In addition to the benefits of treatment to the individual themselves, there is a high chance that family members will also benefit when people with PTSD are treated (Schauer & Schauer, 2010). These aspects should increase motivation to recognize and treat people suffering from mental illnesses as soon as possible. A first step towards this goal could be comprehensive screenings in this population (Baron & Flory, 2018; Kaltenbach et al., 2017; Schneider, Bajbouj, & Heinz, 2017). The RHS-15 and its shortened version, Refugee Health Screener-13 (RHS-13), have been tested in numerous studies as a screening instrument and have been classified as valid instruments (Hollifield et al., 2016; Kaltenbach et al., 2017). As described already, it is currently not possible to treat all people in need of mental health care by means of personal psychotherapy conducted by licenced therapists. For this reason, concepts and considerations around working with lay people may be part of a solution (Butenop, 2016; Elbert et al., 2017; Schneider et al., 2017). One example is Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET; (Neuner, Schauer, Roth, & Elbert, 2002)). NET is specifically designed for people with PTSD and the effect has already been classified as successful (Neuner et al., 2008).

In addition to trained lay therapists, group psychoeducation can also be a way to provide people with information about their symptoms and to identify further possible pathways to receiving support. In a form of group psychoeducation described by Demir and colleagues (Demir et al., 2016), attention was paid to a low-threshold concept so that people could participate regardless of their level of education. Results from the study show that psychoeducation led to psychological relief and an increase in knowledge about mental health. E-mental health care may be another possible solution helping to overcome the treatment gap. Keeping possible barriers in mind, current research yield promising results (Burchert et al., 2018).

Apart from these aspects, it is also critical that psychotherapists receive education about the intricacies of working with refugees in order to reduce possible fears or worries. The ‘Shelter’ project (E-Learning Kinderschutz–SHELTER Trauma, 2019), is one example of an online course in which psychotherapists and people from related fields were trained about working with refugees.

5. Conclusions

The number of mentally stressed people in this sample of refugees is high, but psychotherapeutic care was provided only to a small number. None of the participants received psychotherapeutic treatment according to the recommendations for treatment of PTSD. As the common individual therapy by psychological psychotherapists is not a viable solution in view of the high demand, low-threshold models should be considered in order to better meet the needs of this heavily burdened population.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank all participants who made this research possible. We acknowledge support regarding data collection by the “FlüGe” research consortium and all of our interviewers. We sincerely thank Justin Preston for proofreading the manuscript. Lastly, we acknowledge support for the publication costs by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Open Access Publication Fund of Bielefeld University.

Funding Statement

The research reported was supported by the Ministry of Culture and Science of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia; under Grant 321-8.03.07-127600. The funding body had no influence on designing the study, collecting, analyzing interpreting the data, or writing the manuscript.

Data availability statement

Due to the regional focus of data collection and the detailed sociodemographic information the full dataset does not fully protect anonymity and privacy of the respondents. For this reason, the full dataset cannot be made publicly available. However, excerpts of the data on a higher aggregation level can be provided upon justified demand.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethical Review Board of Bielefeld University granted approval for the study. Approval number: 2017-072W. Written consent was obtained from all study participants.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . (2014). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Bajbouj, M. (2016). Psychosoziale Versorgung von Flüchtlingen in Deutschland. Psychiatrie, 13, 187–11. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1672301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baron, J., & Flory, L. (2016). Versorgungsbericht zur psychosozialen Versorgung von Flüchtlingen und Folteropfern in Deutschland [Internet] (3rd ed.). Retrieved from http://www.baff-zentren.org/produkt/versorgungsbericht-3-auflage/ [Google Scholar]

- Baron, J., & Flory, L. (2018). Versorgungsbericht zur psychosozialen Versorgung von Flüchtlingen und Folteropfern in Deutschland [Internet] (4th ed.). Retrieved from http://www.baff-zentren.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Versorgungsbericht_4.Auflage.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Baron, J., & Flory, L. (2019). Versorgungsbericht zur psychosozialen Versorgung von Flüchtlingen und Folteropfern in Deutschland [Internet] (5th ed.). Retrieved from http://www.baff-zentren.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/BAfF_Versorgungsbericht-5.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bermejo, I., Hölzel, L. P., Kriston, L., & Härter, M. (2012). Subjektiv erlebte Barrieren von Personen mit Migrationshintergrund bei der Inanspruchnahme von Gesundheitsmaßnahmen. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz, 55(8), 944–953. doi: 10.1007/s00103-012-1511-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozorgmehr, K., Mohsenpour, A., Saure, D., Stock, C., Loerbroks, A., Joos, S., & Schneider, C. (2016). Systematic review and evidence mapping of empirical studies on health status and medical care among refugees and asylum seekers in Germany (1990–2014). Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz, 59(5), 599–620. doi: 10.1007/s00103-016-2336-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BPtK–Bundespsychotherapeutenkammer . (2015). BPtK-Standpunkt: Psychische Erkrankungen bei Flüchtlingen [Internet]. Retrieved from https://www.bptk.de/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/20150916_bptk_standpunkt_psychische_erkrankungen_fluechtlinge.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bühring, P., & Gießelmann, K. (2019). Geflüchtete und Asylbewerber–Ohne Sprachmittler funktioniert die Versorgung nicht. Deutsches Ärzteblatt, 116, 308–314. [Google Scholar]

- Burchert, S., Alkneme, M. S., Bird, M., Carswell, K., Cuijpers, P., Hansen, P., ... Knaevelsrud, C. (2018). User-centered app adaptation of a low-intensity e-mental health intervention for Syrian refugees. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 663. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butenop, J. (2016). Gesundheitssicherung Geflüchteter im Regierungsbezirk Unterfranken. Journal Gesundheitsförderung, 3, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chikovani, I., Makhashvili, N., Gotsadze, G., Patel, V., McKee, M., Uchaneishvili, M., & Wallander, J. L. (2015). Health service utilization for mental, behavioural and emotional problems among conflict-affected population in Georgia: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One, 10(4), e0122673. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, N. (2016). Integration between mental health-care providers and traditional spiritual healers: Contextualising Islam in the twenty-first century. Journal of Religion and Health, 55(5), 1665–1671. doi: 10.1007/s10943-016-0234-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu, T., Keller, A. S., & Rasmussen, A. (2013). Effects of post-migration factors on PTSD outcomes among immigrant survivors of political violence. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 15(5), 890–897. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9696-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement, S., Schauman, O., Graham, T., Maggioni, F., Evans-Lacko, S., Bezborodovs, N., … Thornicroft, G. (2015). What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychological Medicine, 45(1), 11–27. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir, S., Reich, H., & Mewes, R. (2016). Psychologische Erstbetreuung für Asylsuchende: Entwicklung und erste Erfahrungen mit einer Gruppenpsychoedukation für Geflüchtete. Psychotherapeutenjournal, 2, 124–131. [Google Scholar]

- Elbert, T., Wilker, S., Schauer, M., & Neuner, F. (2017). Dissemination psychotherapeutischer Module für traumatisierte Geflüchtete: Erkenntnisse aus der Traumaarbeit in Krisen- und Kriegsregionen. Der Nervenarzt, 88(1), 26–33. doi: 10.1007/s00115-016-0245-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E-Learning Kinderschutz–SHELTER Trauma [Internet] . (2019). Retrieved from https://shelter-trauma.elearning-kinderschutz.de [Google Scholar]

- Gäbel, U., Ruf, M., Schauer, M., Odenwald, M., & Neuner, F. (2006). Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and ways of identifying asylum procedures. ZKI Psychology and Psychotherapy, 35, 12–20. doi: 10.1026/1616-3443.35.1.12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galatzer-Levy, I. R., Huang, S. H., & Bonanno, G. A. (2018). Trajectories of resilience and dysfunction following potential trauma: A review and statistical evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 63, 41–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiadou, E., Zbidat, A., Schmitt, G. M., & Erim, Y. (2018). Prevalence of mental distress among Syrian refugees with residence permission in Germany: A registry-based study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 393. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollifield, M., Toolson, E. C., Verbillis-Kolp, S., Farmer, B., Yamazaki, J., Woldehaimanot, T., & Holland, A. (2016). Effective screening for emotional distress in refugees: The Refugee Health Screener. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 204(4), 247–253. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollifield, M., Verbillis-Kolp, S., Farmer, B., Toolson, E. C., Woldehaimanot, T., Yamazaki, J., … SooHoo, J. (2013). The Refugee Health Screener-15 (RHS-15): Development and validation of an instrument for anxiety, depression, and PTSD in refugees. General Hospital Psychiatry, 35(2), 202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi, F., Höfler, M., Strehle, J., Mack, S., Gerschler, A., Scholl, L., & Wittchen, H.-U. (2014). Mental disorders in the general population. Study on the health of adults in Germany and the additional module mental health (DEGS1-MH). Der Nervenarzt, 85(1), 77–87. doi: 10.1007/s00115-013-3961-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongedijk, R. A. (2014). Narrative exposure therapy: An evidence-based treatment for multiple and complex trauma. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1), 26522. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v5.26522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach, E., Härdtner, E., Hermenau, K., Schauer, M., & Elbert, T. (2017). Efficient identification of mental health problems in refugees in Germany: The Refugee Health Screener. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup2), 1389205. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1389205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor, V., Knefel, M., & Lueger-Schuster, B. (2017). Perceived barriers and facilitators of mental health service utilization in adult trauma survivors: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 52, 52–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer, L. J. (2001). Cultural variations in the clinical presentation of depression and anxiety: Implications for diagnosis and treatment. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 62, 22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivelitz, L., Watzke, B., Schulz, H., Härter, M., & Melchior, H. (2015). Health care barriers on the pathways of patients with anxiety and depressive disorders–a qualitative interview study. Psychiatrische Praxis, 42(8), 424–429. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1370306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolassa, I.-T., Ertl, V., Eckart, C., Kolassa, S., Onyut, L. P., & Elbert, T. (2010). Spontaneous remission from PTSD depends on the number of traumatic event types experienced. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 2(3), 169–174. doi: 10.1037/a0019362 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laban, C. J., Gernaat, H. B., Komproe, I. H., & De Jong, J. T. (2007). Prevalence and predictors of health service use among Iraqi asylum seekers in the Netherlands. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 42(10), 837–844. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0240-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamkaddem, M., Stronks, K., Devillé, W. D., Olff, M., Gerritsen, A. A., & Essink-Bot, M. L. (2014). Course of post-traumatic stress disorder and health care utilization among resettled refugees in the Netherlands. BMC Psychiatry, 14(1), 90. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. S., Liddell, B. J., & Nickerson, A. (2016). The relationship between post-migration stress and psychological disorders in refugees and asylum seekers. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18(9), 82. doi: 10.1007/s11920-016-0723-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindert, J., von Ehrenstein, O. S., Wehrwein, A., Brähler, E., & Schäfer, I. (2018). Angst, Depression und posttraumatische Belastungsstörungen bei Flüchtlingen–eine Bestandsaufnahme. PPmP - Psychotherapie Psychosomatik Medizinische Psychologie, 68(1), 22–29. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-103344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier, T., & Straub, M. (2011). “My head is like a bag full of rubbish”: Concepts of illness and treatment expectations in traumatized migrants. Qualitative Health Research, 21(2), 233–248. doi: 10.1177/1049732310383867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . (2018). Post-traumatic stress disorder (NICE Guideline [NG116]) [Internet]. Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng116/resources/posttraumatic-stress-disorder-pdf-66141601777861 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuner, F., Onyut, P. L., Ertl, V., Odenwald, M., Schauer, E., & Elbert, T. (2008). Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder by trained lay counselors in an African refugee settlement: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(4), 686–694. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuner, F., Schauer, M., Roth, W. T., & Elbert, T. (2002). A narrative exposure treatment as intervention in a refugee camp: A case report. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 30(2), 205–209. doi: 10.1017/S1352465802002072 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phoenix Australia–Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health . (2013). Australian guidelines for the treatment of acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder [Internet]. Retrieved from https://www.phoenixaustralia.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Phoenix-ASD-PTSD-Guidelines.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Satinsky, E., Fuhr, D. C., Woodward, A., Sondorp, E., & Roberts, B. (2019). Mental health care utilization and access among refugees and asylum seekers in Europe: A systematic review. Health Policy, 123(9), 851–863. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer, I., Gast, U., Hofmann, A., Knaevelsrud, C., Lampe, A., Liebermann, P., ... Wöller, W. (2019). S3-Leitlinie Posttraumatische Belastungsstörung. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Schauer, M., & Schauer, E. (2010). Trauma-focused public mental-health interventions: A paradigm shift in humanitarian assistance and aid work. In Martz E. (Ed.), Trauma rehabilitation after war and conflict (pp. 389–428). New York: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-5722-1_16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, F., Bajbouj, M., & Heinz, A. (2017). Psychische Versorgung von Flüchtlingen in Deutschland: Modell für ein gestuftes Vorgehen. Der Nervenarzt, 88(1), 10–17. doi: 10.1007/s00115-016-0243-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder, H., Zok, K., & Faulbaum, F. (2018). Gesundheit von Geflüchteten in Deutschland–Ergebnisse einer Befragung von Schutzsuchenden aus Syrien, Irak und Afghanistan. WIdO-monitor, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Steel, Z., Chey, T., Silove, D., Marnane, C., Bryant, R. A., & Van Ommeren, M. (2009). Association of torture and other potentially traumatic events with mental health outcomes among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 302(5), 537–549. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel, Z., Silove, D., Bird, K., McGorry, P., & Mohan, P. (1999). Pathways from war trauma to posttraumatic stress symptoms among Tamil asylum seekers, refugees, and immigrants. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 12(3), 421–435. doi: 10.1023/A:1024710902534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the regional focus of data collection and the detailed sociodemographic information the full dataset does not fully protect anonymity and privacy of the respondents. For this reason, the full dataset cannot be made publicly available. However, excerpts of the data on a higher aggregation level can be provided upon justified demand.