Abstract

Background

Stress and depression are risk factors for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) exacerbations. It is unknown if resilience, or one’s ability to recover from adversity, impacts disease course. The aim of this study was to examine the association between resilience and IBD disease activity, quality of life (QoL), and IBD-related surgeries.

Methods

We performed a cross-sectional study of IBD patients at an academic center. Patients completed the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale questionnaire, which measures resilience (high resilience score ≥ 35). The primary outcome was IBD disease activity, measured by Mayo score and Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI). The QoL and IBD-related surgeries were also assessed. Multivariate linear regression was conducted to assess the association of high resilience with disease activity and QoL.

Results

Our patient sample comprised 92 patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and 137 patients with Crohn disease (CD). High resilience was noted in 27% of patients with UC and 21.5% of patients with CD. Among patients with UC, those with high resilience had a mean Mayo score of 1.54, and those with low resilience had a mean Mayo score of 4.31, P < 0.001. Among patients with CD, those with high resilience had a mean HBI of 2.31, and those with low resilience had a mean HBI of 3.95, P = 0.035. In multivariable analysis, high resilience was independently associated with lower disease activity in both UC (P < 0.001) and CD (P = 0.037) and with higher QoL (P = 0.016). High resilience was also associated with fewer surgeries (P = 0.001) among patients with CD.

Conclusions

High resilience was independently associated with lower disease activity and better QoL in patients with IBD and fewer IBD surgeries in patients with CD. These findings suggest that resilience may be a modifiable factor that can risk-stratify patients with IBD prone to poor outcomes.

Keywords: Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, resilience, disease activity, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), comprising ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn disease (CD), affects >1 million individuals in the United States and 2.5 million in Europe.1 These chronic, complex diseases are often diagnosed in the second and third decades of life and have the potential to significantly impact one’s life course and personal choices, especially if disease onset or the adjustment period thereafter is perceived as traumatic or insurmountable.2 With some success, several studies have attempted to link psychological stress and depression with disease exacerbations, unplanned health care utilization, and poor quality of life (QoL).3-6 However, this literature does not consider individual differences in stress response or how these differences impact disease activity.7

The current study utilizes a positive psychology framework to understand the role of stress in IBD, seeking a proof of concept that stress resilience could be a protective factor in patients with IBD.8 Resilience is defined as the inherent and modifiable capacity of an individual to cope or recover from adversity.9 Neurobiological evidence supports the ability of psychological resilience to offset catecholamine and cortisol responses in the face of stress or trauma and to work through various brain structures and neurotransmitters to reduce the long-term impact of stress or trauma on the body.10 Resilience is a modifiable trait that is responsive to behavioral interventions, with resilience-building therapies associated with improved physical health and well-being.11

High psychological resilience could facilitate positive outcomes in IBD. It inflicts a substantial psychological burden, imposing ongoing stress on patients because of its unpredictable relapsing and remitting disease course that can lead to bowel damage, fatigue, and disability.12, 13 In addition, IBD is often stigmatized socially.14 Having IBD requires continuous adaptation to newly required self-management skills including adherence to complex medication regimens (and tolerance of adverse effects), transition from one medication to the next, and facing the need for abdominal surgeries. Research has shown that an individual’s ability to adjust to a diagnosis of IBD and the changing demands going forward is associated with a lower emotional representation of disease, less functional overlap, and higher QoL.13 The primary aim of this study was to elucidate the association between resilience and IBD disease activity using clinical disease activity indices. We also sought to determine the association of resilience with QoL and IBD-related surgeries.

METHODS

Study Population and Design

We conducted a cross-sectional cohort study enrolling consecutive adult patients (between ages 18 and 65 years) seen and evaluated at an urban tertiary care IBD center from March 2016 to July 2017. We included patients with an endoscopically confirmed diagnosis of IBD. Patients who did not complete administered questionnaires or had incomplete clinical data were excluded. Enrolled patients completed a series of validated questionnaires before a routine clinic visit appointment, including:

the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CDRISC), which contains 10 items each rated on a 5-point Likert scale (range, 0-40). Items are not disease-specific but rather measure one’s general perceived ability to recover from adversity. A higher score represents greater resilience, with scores ≥35 indicative of “high” resilience.15, 16

the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ9), a 9-item questionnaire that screens for the presence and severity of depression.17

the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD7), a 7-item questionnaire that can identify the presence and severity of anxiety, particularly worry.18

the NIH PROMIS-Global Health, a 10-item questionnaire that measures general health-related QoL and has been normed (t scores) for the general population.19

Data Collection

In addition to questionnaire completion, data were manually acquired from electronic medical records including demographics (age, sex, history of psychiatric illness, current opioid treatment) and IBD-specific information including age at diagnosis, treatment modality, prior number of IBD-related surgeries, and current disease activity. The primary outcome was clinical disease activity, defined by the Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI) for patients with CD and the Mayo score for patients with UC.20-22 Our IBD center utilizes templated notes that capture the HBI (remission defined as a score of ≤4) and Mayo score (remission defined as a score of ≤2). The Mayo score included the most recent colonoscopy, within a 6-month interval, before the date of the questionnaire and clinic visit. Our other outcome variables of interest included QoL, measured by the NIH PROMIS-Global Health questionnaire19 and the total number of IBD surgeries. This study was approved by the Mount Sinai Institutional Review Board.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics of the baseline characteristics of the patients in the IBD study sample and each IBD group were conducted and are reported as proportions and means for categorical and continuous variables, respectively (see Table 1). Bivariate analyses to determine the association between resilience and disease activity (represented by HBI and Mayo scores) and QoL were performed via linear regression. The normalized natural log of HBI was analyzed because it was not normally distributed. Multivariate regression models were then performed to assess the independent association of resilience and disease activity and QoL while adjusting for covariates (any patient demographic or disease variable that was related to disease activity or QoL at P < 0.2 in a similar set of bivariate linear regressions; these were only excluded if they contributed to notable multicollinearity). Finally, generalized linear regression, modeling a Poisson distribution for count data, was used to assess the bivariate association between high resilience and number of IBD surgeries separately in each IBD group (multivariate analyses could not be performed because of insufficient samples with such surgeries). All analyses were performed with the statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics, footnote 24.

TABLE 1.

Summary of Patient Demographic, Psychosocial, and IBD Disease Characteristics

| UC (n = 92) | CD (n = 137) | IBD (n = 229) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, % | 48 (52.2) | 74 (54.0) | 122 (53.2) |

| History psychiatric illness, % | 11 (16.7) | 20 (20.2) | 31 (13.5) |

| PHQ9 depression score* | 4.00 (1.00-8.00) | 3.00 (1.00-7.00) | 4.00 (1.00-7.00) |

| GAD7 anxiety score* | 2.00 (0.00-5.00) | 3.00 (0.00-6.00) | 2.50 (0.00-5.25) |

| CDRISC resilience score | 28.27 (±8.05) | 27.96 (±8.08) | 28.11 (±7.95) |

| High resilience status (≥35), % | 24 (27.0) | 29 (21.5) | 53 (23.0) |

| QoL | 38.82 (±10.06) | 37.31 (±9.01) | 37.79 (±9.47) |

| Opioid use, % | 6 (9.2) | 16 (15.8) | 22 (10.0) |

| Disease duration, y* | 7.21 (2.83-16.45) | 7.22 (2.30-12.93) | 7.22 (2.81-13.97) |

| Prior IBD surgery, % | 12 (13.0) | 41 (30.0) | 53 (23.1) |

| Steroid for IBD, % | 21 (38.9) | 28 (33.3) | 50 (35.7) |

| Prior biologic, % | 13 (14.1) | 32 (23.4) | 45 (20.0) |

| In remission, %† | 38 (41.3) | 86 (70.5) | 124 (54.1) |

| Mayo Clinic score | 3.58 (±2.70) | ||

| HBI* | 3.00 (0.75–5.00) |

Data presented as mean (standard deviation) or number (%).

*Median (interquartile range) presented given variable not normally distributed (normalized natural log value of HBI was analyzed).

†Remission: for patients with CD, HBI ≤ 4; for patients with UC, Mayo score ≤ 2.

RESULTS

Study Cohort Characteristics

A total of 92 patients with UC and 137 patients with CD were included in the analyses. Descriptive statistics of demographic, psychological, and IBD characteristics of each patient group and the overall sample are presented in Table 1. Of the 229 patients, 53% were female. With regard to IBD management, 10.0% were prescribed opioids, 35.7% were on steroids, and 20.0% had prior biologic exposure. Mean IBD disease duration was 7.22 years, with 23.1% having a prior IBD surgery. The mean Mayo score for patients with UC was 3.58 (±2.70), and the median HBI score for patients with CD was 3.00 (interquartile range, 0.75-5.00). A history of psychiatric illness was noted in 31 patients (13.5%). The mean resilience score for patients with UC was 28.27 (±8.05), and the mean resilience score for patients with CD was 27.96 (±8.08). High resilience was observed in 27% of patients with UC and similarly in 21.5% of patients with CD. Among patients with UC, those with high resilience had a mean Mayo score of 1.54 (±1.29) and those with low resilience had a mean Mayo score of 4.31 (±2.74), P < 0.001 (Table 2). Among patients with CD patients, those with high resilience had a mean HBI score of 2.31 (±3.26), and low resilience had a mean HBI score of 3.95(±3.86), P = 0.035 (Table 2). Furthermore, among patients with CD, of those in remission (HBI score ≤4), 26% had high resilience, but only 16% of those with active disease (HBI score >4) had high resilience. Although there was a higher proportion of patients with high resilience in the remission category, this difference was not significant (P = 0.14) (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

High vs Low Resilience and IBD Disease Activity Measured Using Mayo or HBI

| Low Resilience* | High Resilience | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| UC (Mayo score), mean (SD) | 4.31 (2.74) | 1.54 (1.29) | P < 0.001 |

| CD (HBI), mean (SD) | 3.95 (3.86) | 2.31 (3.26) | P = 0.035 |

*Low resilience: CDRISC score <35; high resilience: CDRISC score ≥35.

TABLE 3.

Proportion of High Resilience by HBI Score

| HBI ≤4 | HBI >4 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 84 | n = 36 | ||

| High resilience n (%) | 22 (26) | 5 (16) | P = 0.14 |

Low resilience: CDRISC <35; High resilience: CDRISC ≥35.

Bivariate and Multivariate Analyses

CD disease activity

The results of bivariate linear regression indicated a significant association between high resilience and lower disease activity in patients with CD (P = 0.004; Table 4). In addition, whereas a history of psychiatric illness (P = 0.025), a higher PHQ9 depression score (P < 0.001), higher GAD7 anxiety scores (P = 0.021), and a current opioid prescription were all associated with higher HBI scores (P = 0.001), better QoL was associated with lower HBI scores (P < 0.001). The multivariate linear regression, which adjusted for covariates deemed significant in the aforementioned bivariate analyses, indicated that high resilience status (B, –0.471; 95% confidence interval [CI], –0.913 to –0.029; P = 0.037; Table 4) was independently associated with less disease activity for patients with CD. A current opioid prescription was also independently associated with higher disease activity (B, 0.597; 95% CI, 0.167-1.027; P = 0.007).

TABLE 4.

Results of Bivariate (Unadjusted) and Multivariate (Adjusted) Linear Regression Analyses of Association of Resilience With HBI

| Beta Coefficient | 95% CI | P | Partial R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant bivariate results | ||||

| High resilience | –0.518 | –0.871 to –0.165 | 0.004 | — |

| Psychiatric illness | 0.471 | 0.061 to 0.881 | 0.025 | — |

| PHQ9 score | 0.055 | 0.026 to 0.085 | <0.001 | — |

| GAD7 score | 0.043 | 0.007 to 0.079 | 0.021 | — |

| Opioid prescription | 0.730 | 0.296 to 1.164 | 0.001 | — |

| QoL | –0.051 | –0.069 to –0.033 | <0.001 | — |

| Significant multivariate results | ||||

| High resilience | –0.471 | –0.913 to –0.029 | 0.037 | –0.215 |

| Opioid prescription | 0.597 | 0.167 to 1.027 | 0.007 | 0.280 |

N = 137. Normalized natural log value of HBI was analyzed. Partial R2 reflects unique variance explained by each predictor.

UC disease activity

The results of bivariate linear regression analyses also indicated a significant association between high resilience and lower Mayo scores for patients with UC (P < 0.001; Table 5). Higher QoL was also associated with lower UC disease activity (P = 0.018). History of psychiatric illness (P = 0.035), a greater PHQ9 depression score (P < 0.001), a higher GAD7 anxiety score (P < 0.001), an opioid prescription (P = 0.005), and a steroid prescription (P = 0.02) were inversely associated with Mayo scores. The results of the multivariate regression that adjusted for covariates deemed significant in the bivariate analyses indicated that high resilience status was independently associated with less disease activity (B, –2.660; 95% CI, –3.950 to –1.370; P < 0.001) (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Results of Bivariate (Unadjusted) and Multivariate (Adjusted) Linear Regression Analyses of Association of Resilience with Mayo UC Score

| Beta Coefficient | 95% CI | P | Partial R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant bivariate results | ||||

| High resilience | –2.765 | –1.604 to –4.737 | <0.001 | — |

| Psychiatric illness | 1.967 | 0.145 to 3.789 | 0.035 | — |

| PHQ9 score | 0.294 | 0.169 to 0.419 | <0.001 | — |

| GAD7 score | 0.222 | 0.101 to 0.343 | <0.001 | — |

| Opioid prescription | 3.202 | 0.978 to 5.425 | 0.005 | — |

| Steroid prescription | 1.625 | 0.269 to 2.981 | 0.020 | — |

| QoL | –0.090 | –0.164 to –0.016 | 0.018 | — |

| Significant multivariate results | ||||

| High resilience | –2.660 | –3.950 to –1.370 | <0.001 | –0.442 |

N = 92.

QoL

Bivariate analysis revealed high resilience was significantly associated with a higher QoL (P = 0.003; Table 6) among patients with IBD. Steroid prescription (P = 0.011) and higher PHQ9 depression (P < 0.001) and GAD7 anxiety (P < 0.001) scores were also associated with poorer QoL among patients with IBD. Multivariate regression analysis controlling for covariates suggested that high resilience was independently associated with greater QoL in patients with CD and those with UC (P = 0.016; Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Results of Bivariate (Unadjusted) and Multivariate (Adjusted) Regression Analyses of Association of Resilience With QoL in Patients With IBD

| Significant bivariate results | Beta Coefficient | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| High resilience | 6.120 | 2.053 to 10.187 | 0.003 |

| Steroid prescription | –0.4778 | –8.428 to –1.129 | 0.011 |

| PHQ9 score | –1.1014 | –1.306 to 0.722 | <0.001 |

| GAD7 score | –0.796 | –1.118 to –0.0475 | <0.001 |

| Significant multivariate results | |||

| High resilience | 4.486 | 0.837 to 8.136 | 0.016 |

N = 235.

IBD surgeries

The results of bivariate generalized linear regression models for count data indicated that high resilience was associated with fewer IBD-related surgeries (P = 0.001; Table 7) for patients with CD but not for patients with UC (P = 0.086; Table 7).

TABLE 7.

Results of Bivariate Generalized Regression Analyses of Association of Resilience With IBD-Related Surgeries

| Number of IBD-Related Surgeries | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P | |

| High resilience (CD) | 0.127 | 0.036-0.450 | 0.001 |

| High resilience (UC) | 0.960 | 0.915-1.006 | 0.086 |

DISCUSSION

Although stress and depression have been shown to negatively impact disease course, including flares, surgeries, poor QoL, and high health costs, protective factors such as psychological resilience, which has been extensively studied in other diseases, has not been examined in IBD.23, 24 This study is the first to explore the association between resilience and IBD disease activity, QoL, and number of IBD-related surgeries.

We observed significant associations between resilience and IBD disease characteristics. Multivariate analyses found an independent association between high resilience and lower disease activity for both the CD and the UC populations. Moreover, multivariate analyses indicated an independent relationship between high resilience and better QoL for patients with IBD overall. Finally, high resilience was significantly associated with fewer IBD-related surgeries for patients with CD although not for patients with UC. Furthermore, we found on bivariate analysis that high resilience was significantly associated with lower scores on the PHQ9 and GAD7 evaluations.

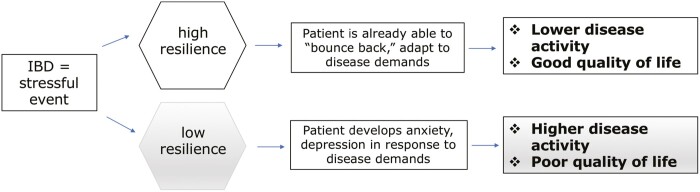

We propose that patients with high resilience are better able to cope with the ongoing demands of IBD, and resilience is therefore protective against negative disease outcomes (Fig. 1). Our study is the first to show that resilience is independently associated with established markers of disease activity, measured via the HBI and the Mayo score (including endoscopic data) measures. The present study is also the first to link high resilience with fewer CD surgeries. The lack of significance for UC may be because of the low power relative to the CD cohort.

FIGURE 1.

Proposed resilience-based IBD care model.

Although our study is the first to examine the relationship between resilience and IBD disease activity, our findings on resilience and QoL are consistent with the current literature. Taylor et al25 reported that resilience, measured via CDRISC, was positively associated with both mental and physical QoL in patients with IBD. Carlsen et al26 found that the CDRISC resilience score independently predicted transition readiness—the traits associated with successful lifelong disease self-management. Melinder et al27 reported that low stress resilience in adolescence was associated with an increased risk of developing UC and CD, with the association in CD being of a greater magnitude.

Our findings support the hypothesis that patients who are highly resilient may have better coping mechanisms that can buffer against IBD-related stresses and psychological stress. Identifying vulnerable patients or those with low resilience may provide a unique opportunity to create individualized treatment plans that center around positive psychology and resilience-building.8

The present study has several limitations. First, given the cross-sectional nature of our study it is possible that our findings could result from reverse causation. That is, higher disease burden (clinical activity and surgery) may result in lower resilience. Prospective studies using high resilience as a predictor of outcomes are required. Second, recent colonoscopy data to calculate the full Mayo score could be noncontemporaneous to the resilience questionnaire; however, a 6-month colonoscopy window is likely a robust estimate. Furthermore, the study’s primary disease activity outcome for CD, the HBI, captured clinical activity without objective disease metrics28; colonoscopy data for this cohort tended to be more distant, with less standard reporting of endoscopic scores and findings. Third, the majority of our patient cohort with CD were in clinical remission, representing a healthier patient population with IBD. Future prospective studies should be conducted with a well-balanced IBD cohort. In addition, the diagnoses of anxiety and depression were made based on self-administered screening rather than on full clinical evaluation.

In conclusion, high levels of resilience are independently associated with lower disease activity and better QoL in patients with IBD. Our study calls for further research into the role that high resilience plays as a potential moderator between an individual’s stress response and IBD disease course, suggesting that each individual’s unique resilience may impact the clinical course. We hope that these data raise further attention to the importance of creating personalized, patient-centered approaches to IBD treatment.29

Author contributions: PS and LK: study concept and design, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, and writing of manuscript. CF: statistical analysis, interpretation of data, and writing of manuscript. BI, RCU, and MCD: study concept and design, interpretation of data, and revision of manuscript for important intellectual content.

Supported by: RCU is supported by an NIH K23 Career Development Award (K23KD111995-01A1) and a Career Development Award from the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation.

Conflicts of interest: RCU has been a consultant for Takeda, Pfizer, and Janssen and has received research support from AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Pfizer. MCD has been a consultant for AbbVie, Janssen, Takeda, Celgene, Prometheus Labs, UCB, Genentech, and Pfizer and is a cofounder of Trellus Health. LK has been a consultant for Pfizer, has received research funding from Pfizer and AbbVie, and is a cofounder of Trellus Health.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kaplan GG. The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:720–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Taft TH, Bedell A, Craven MR, et al. Initial assessment of post-traumatic stress in a US cohort of inflammatory bowel disease patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25:1577–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bernstein MT, Targownik LE, Sexton KA, et al. Assessing the relationship between sources of stress and symptom changes among persons with IBD over time: a prospective study. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;2016:1681507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Click BH, Szigethy E, Binion DG, et al. Predictors of unplanned healthcare utilization in patients enrolled in an IBD patient centered medical home (PCMH). Gastroenterology. 2017;152:S25–S26. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Knowles SR, Graff LA, Wilding H, et al. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analyses—part I. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:742–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Knowles SR, Keefer L, Wilding H, et al. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analyses—part II. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:966–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Keefer L, Keshavarzian A, Mutlu E. Reconsidering the methodology of “stress” research in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2008;2:193–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Keefer L. Behavioural medicine and gastrointestinal disorders: the promise of positive psychology. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:378–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Iacoviello BM, Charney DS. Psychosocial facets of resilience: implications for preventing posttrauma psychopathology, treating trauma survivors, and enhancing community resilience. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2014;5. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v5.23970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bowirrat A, Chen TJ, Blum K, et al. Neuro-psychopharmacogenetics and neurological antecedents of posttraumatic stress disorder: unlocking the mysteries of resilience and vulnerability. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2010;8:335–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chmitorz A, Kunzler A, Helmreich I, et al. Intervention studies to foster resilience—a systematic review and proposal for a resilience framework in future intervention studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;59:78–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mikocka-Walus A, Knowles SR, Keefer L, et al. Controversies revisited: a systematic review of the comorbidity of depression and anxiety with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:752–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kiebles JL, Doerfler B, Keefer L. Preliminary evidence supporting a framework of psychological adjustment to inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1685–1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Taft TH, Keefer L. A systematic review of disease-related stigmatization in patients living with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016;9:49–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18:76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Campbell-Sills L, Forde DR, Stein MB. Demographic and childhood environmental predictors of resilience in a community sample. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43:1007–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al. ; PROMIS Cooperative Group . The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care. 2007;45:S3–S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harvey RF, Bradshaw JM. A simple index of Crohn’s-disease activity. Lancet. 1980;1:514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dignass A, Eliakim R, Magro F, et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis part 1: definitions and diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:965–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Walmsley RS, Ayres RC, Pounder RE, et al. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut. 1998;43:29–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Keefer L, Kane SV. Considering the bidirectional pathways between depression and IBD: recommendations for comprehensive IBD care. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2017;13:164–169. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Johnston MC, Porteous T, Crilly MA, et al. Physical disease and resilient outcomes: a systematic review of resilience definitions and study methods. Psychosomatics. 2015;56:168–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Taylor K, Scruggs PW, Balemba OB, et al. Associations between physical activity, resilience, and quality of life in people with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2018;118:829–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Carlsen K, Haddad N, Gordon J, et al. Self-efficacy and resilience are useful predictors of transition readiness scores in adolescents with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Melinder C, Hiyoshi A, Fall K, et al. Stress resilience and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a cohort study of men living in Sweden. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dubinsky MC. Reviewing treatments and outcomes in the evolving landscape of ulcerative colitis. Postgrad Med. 2017;129:538–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Siegel CA. Refocusing IBD patient management: personalized, proactive, and patient-centered care. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:1440–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]