Abstract

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are a group of rare Philadelphia-negative chronic leukemias. Disease rarity has resulted in limited expertise concentrated in specialist centres. Patients are often referred to such expert centres for diagnostic issues, complex decision-making, access to novel drugs through clinical trials, and supportive care. Attending such appointments may increase financial and travel burden, increase caregiver stress, and negatively impact quality of life. To address this, the MPN program at Princess Margaret (PM) Cancer Centre has implemented a shared-care model, working with local healthcare providers to provide ongoing management, and supportive care for MPN patients closer to home. This decreases patient travel burden, while maintaining high-quality patient-centered care. In this article we share our experience implementing the shared-care model. This model is potentially applicable to other chronic hematological malignancies and rare chronic diseases. The ultimate goal of shared-care is not to centralize care, but instead to build a community of accessible care for the patient.

Keywords: care delivery models, chronic leukemia, myeloproliferative neoplasms, shared-care, hematological malignancies

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this paper is to describe the shared-care model utilized at Princess Margaret (PM) Cancer Centre for patients diagnosed with a Philadelphia-negative myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN). The aim of the MPN shared-care model is to implement high-quality care to allow patients to receive coordinated treatment from both the specialized oncology centre and their local shared-care provider (Hershenfeld et al., 2017; Khera et al., 2017). In this paper, we first define the potential elements of the shared-care model in the MPN program. Secondly, this paper will illustrate through case studies how this model has been implemented within the MPN program at PM, what lessons we have learned through implementing the model, the benefits it provides, challenges encountered, and the role of the clinical nurse specialist. In this paper, local shared-care providers are hematologists, oncologists, and/or internists at local hospitals. In addition, family physicians also play a critical role in patient care, managing co-morbidities and implementation of cardiovascular risk prevention strategies. The focus of this paper is on managing MPN and its related symptoms, which requires coordination of care between physicians in tertiary care setting and hematologists, oncologists and internists providing care in the community setting.

Evidence for proper care-coordination in shared-care model

Previous studies have identified challenges that arise due to a lack of proper care coordination including communication breakdown, lack of information for patients and caregivers, travel and caregiver burden, lack of psychosocial, financial and emotional support, and frequent emergency room visits (Gorin et al., 2017; Khera et al., 2017; Bazzell, Spurlock & McBride 2015).

Care coordination can take on many forms, ranging from implementation of a care coordinator/patient-navigator as a single point of contact for both the patient and interdisciplinary team, to the utilization of information technologies such as telemedicine (Gorin et al., 2017; Khera et al., 2017; Chumbler et al., 2007; Girault et al., 2015). Studies have demonstrated that coordination of care within the context of shared-care results in improved health-related quality of life, fewer unexpected hospitalizations (Chumber et al., 2007), decreased travel burden (Hershenfeld et al., 2017), and improved understanding and knowledge translation between the consulting team and local providers (Nielsen et al., 2003). This in turn builds a community of practice, rather than having care centralized, allowing the majority of care to be delivered closer to home in a safe manner, increased patient satisfaction, and better overall quality of life (Gorin et al., 2017).

Myeloproliferative Neoplasms

MPNs are characterized by the overproduction of one or more types of mature blood cells (Arber et al., 2016). There are three classical forms of Philadelphia negative MPNs: polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and primary myelofibrosis (PMF) (Mehta et al., 2014).

Based on data from the United States between 2008 and 2010, the prevalence of PV is 44–55 per 100,000; ET is 38–57 per 100,000, while the prevalence of PMF is much lower at 4–6 per 100,000 (Mehta et al., 2014). Over the long-term 5–15% of patients with PV or ET can transform to post PV myelofibrosis (PPV-MF) or post ET myelofibrosis (PET-MF). The prevalence of post-PV MF is 0.3–0.7 per 100,000, and post-ET MF is 0.5–1.1 per 100,000 (Mehta et al., 2014). Unfortunately, at present there are no Canadian epidemiological data available. However, in the MPN program at PM, from 2015 to present, we have seen 15 cases of PV and ET patients, with 58 cases of MF patients annually. Of note, the MPN program at PM is skewed towards seeing more MF patients, as these patients tend to experience greater symptom burden, complex medical situations, and require additional medical interventions. The three most common driver mutations in MPN are janus kinas 2 (JAK2), calreticulin (CALR), and myeloproliferative leukemia protein (MPL) (Arber et al., 2016).

In this article, we will use the term MF collectively to include PMF, PPV-MF, and PET-MF. Although classical MPNs are considered chronic leukemias, PV, ET and MF may transform to acute myeloid leukemia (AML) over time. The risk of leukemic transformation is dependent on various factors, such as sub-type of MPN, patient age, and presence of high-risk genetic aberrations such as cytogenetics and somatic mutations (Mehta et al., 2014).

Due to the overproduction of one or more types of blood cells, patients with MPN are at a higher risk for a number of additional medical complications. The incidence of hemorrhagic complications is 1.7–20% in PV patients and 3.6–37% in ET patients (Elliott & Tefferi, 2004). The incidence of thrombotic events in PV patients is 12–39%, while in ET patients it is 11–25% (Elliott & Tefferi, 2004). Hemorrhagic and/or thrombotic events include pulmonary embolism, stroke or myocardial infarct, which can negatively affect overall well-being (Martin, 2017). MF and progressive bone marrow fibrosis can result in insufficient hematopoiesis, leading to anemia and transfusion dependency; this translates into more frequent hospital visits for transfusions, and also increases the risk of iron overload (Mughal et al., 2014).

Splenomegaly due to extramedullary haematopoiesis can also arise due to MF, which can cause the patient to experience significant abdominal pain, early satiety and decreased appetite, and result in significant weight loss and cachexia (Mitra et al., 2013; Mughal et al., 2014). Increased spleen size also leads to increased blood flow into the portal vein system, causing portal hypertension, which can lead to esophageal and gastric varices (Mitra et al., 2013); in turn this can worsen anemia and require medical intervention. Increased blood flow to the portal vein system can also lead to thrombosis and splenic infarct when blood supply demands are not met (Mitra et al. 2013). Other common and burdensome symptoms such as drenching night sweats, fatigue and generalized pain are also experienced by patients with MPN, especially those with MF (Harrison et al., 2017). These symptoms not only negatively impact quality of life (Mughal et al., 2014) but can strain the patient and family caregiver relationship (Harrison et al., 2017).

Shared-care model in MPNs

Shared-care is defined as the “joint participation of primary/local and specialized care providers in the planned delivery of care for patients with chronic conditions, underpinned by enhanced information exchange” (Hall et al., 2011, p.554–555). The shared-care model is not a new concept, having been utilized in various diseases including malignant hematology, diabetes, mental illness, and substance abuse (Hershenfeld et al., 2017; Khera et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2008). This model of care allows patients access to specialized treatment while maintaining a connection with their local care provider for routine care such as medication dose adjustment, management of co-morbidities, monitoring of blood counts, and transfusion support (Khera et al., 2017; Gorin et al., 2017).

Due to the complexity and rarity of MPNs, not all local hospitals have the expertise or experience to care for such patients. The PM Cancer Centre is a national resource and referral program for MPN patients in Toronto, Canada. The MPN program at PM offers enhanced diagnostic abilities to help in complex cases and provides a wide range of treatment options including allogeneic bone marrow transplant, clinical trials, and supportive therapy to patients with an MPN. However, due to the chronic and complex nature of MPNs, follow-up and supportive care is necessary to not only monitor and manage changes and/or progression of the MPN, but also other comorbidities patients may have, to ensure their well-being (Mehta et al., 2014).

Attending PM can be burdensome for patients due to the distance, costs, and other difficulties (e.g., caregiver burden, arranging for alternative transportation). Establishing a partnership with local hospitals through shared-care helps mitigate some of these concerns (Hershenfeld et al., 2017). Shared-care also facilitates knowledge translation to the local care team and allows patients to continue to receive ongoing supportive care such as blood count checks, transfusion support as required, renewal of medication, and dose adjustments at their local hospital. This in turn decreases travel time and the interruption to the daily life of the patient and their caregiver (Khera et al., 2017; Hershenfeld et al., 2017).

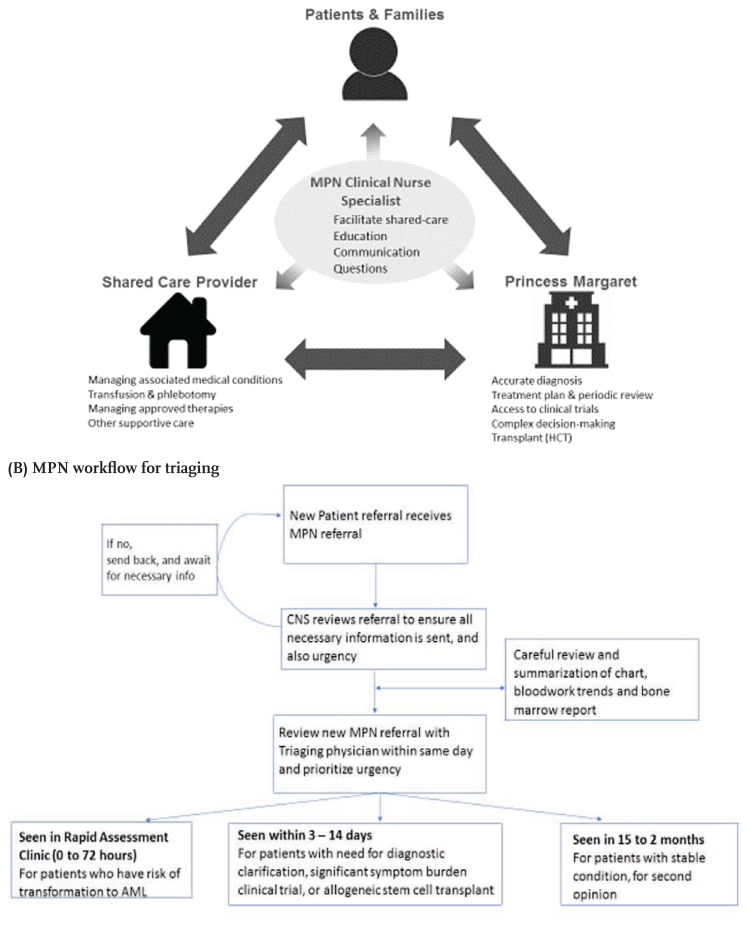

Successful shared-care requires proper care coordination (Khera et al., 2017; Chumbler et al., 2007) and clear understanding of expectations and responsibilities between key stakeholders (Figure 1A). In addition, it is extremely important that the model of care is explained to the patients and their caregivers from the beginning, so that they understand the role of each shared care provider.

Figure 1.

(A) MPN Shared-care model (B) MPN workflow for triaging

Figure 1A illustrates the shared-care model for the MPN program at the PM. Key stakeholders include the patient and their family, PM (specialized oncology centre), the shared-care provider (local hospital), and clinical nurse specialist (CNS). The responsibilities and expectations of each stakeholder are clearly outlined (Devlin & Siddiq, 2016; Tomasone et al., 2017). The role of the MPN Program at PM is to provide assistance in diagnostic issues, offer advice on complex clinical scenarios, establish a treatment plan, provide access to clinical trials where applicable, and engage in decision-making regarding complex treatments such as allogeneic stem cell transplant. The MPN program at PM also empowers the local healthcare teams by facilitating access to additional resources. In addition, the MPN team organizes meetings with community share care providers to discuss their educational needs and other tools which can facilitate the active participation of shared care providers. The role of the local shared-care provider is to provide approved therapies, engage in ongoing supportive care (e.g., count checks and transfusion support), and monitor and manage the established therapy and other co-morbidities (Devlin & Siddiq, 2016; Khera et al., 2017). There is an expectation that patients are seen at the necessary frequency at either the local shared-care provider and/or at PM. Shared-care coordination is led by the CNS in the MPN program, the CNS works collaboratively with all stakeholders to facilitate care-coordination and communication, and serve as a health learning resource for the patient and caregiver, and local shared-care partners. Multi-directional arrows in Figure 1A indicate constant communication between shared-care team members.

Patients seen at the MPN program at PM are frequently engaged in aggressive therapy approaches, with one or more lines of therapies that have not been successful, and underlying comorbidities that add to the complexity of their disease trajectory. The following case studies highlight the clinical complexities surrounding patients with MPN and how shared-care may provide additional benefit to the patient.

Case Study One

The disease trajectory of a 58-year-old man diagnosed with PPV-MF is shown in Figure 2A. At age 53, Mr. B was found through routine bloodwork to have elevated hemoglobin and hematocrit, which prompted a referral for further hematological work-up. Based on persistent erythrocytosis, and the presence of JAK2 mutation, he was presumed PV, and treatment with phlebotomy initiated.

Figure 2A.

Case studies

Interestingly, Mr. B lost the need for phlebotomies one year later and started to develop mild anemia. Unfortunately, over time he became heavily transfusion dependent, and developed symptomatic splenomegaly and constitutional symptoms.

Given this change is Mr. B’s clinical presentation, the local hematologist referred Mr. B to the MPN program at PM. Through the consultation appointment with the MPN program a diagnosis of PPV-MF was confirmed. Given the significant symptom burden, treatment with ruxolitinib and Eprex was initiated, after approvals for both medications were obtained. Ongoing follow-up and dose adjustment were completed through the local hematologist to decrease travel burden and impact to daily life.

Through shared-care and ongoing communication between the local hematologist and MPN program, the healthcare team realized that although Mr. B’s constitutional symptoms had improved, his spleen remained enlarged and still required one transfusion of packed-red-blood cells per week. There were circulating blasts in his peripheral blood, indicating his disease continued to behave aggressively. This was communicated to Mr. B through a follow-up visit at the MPN program, and the decision was to consider an allogeneic stem cell transplant. Unfortunately, due to Mr. B’s splenomegaly, the transplant team felt further reduction of spleen size was needed prior to proceeding with transplant.

Given this recommendation from the transplant team, we increased Mr. B’s dose of ruxolitinib to the highest dose in hopes of further reducing his spleen size and avoid a splenectomy. The MPN team worked closely with the local hematologist not only to monitor Mr. B’s counts and transfusion support, but also to prepare Mr. B for a possible splenectomy if ruxolitinib could not further shrink his spleen to a safe size for transplant. The local hematologist arranged for vaccinations for Mr. B should he need to proceed with splenectomy, and the MPN team arranged for Mr. B to be seen by a general surgeon for possible splenectomy.

Mr. B unfortunately did not achieve further spleen reduction after being on a higher dose of ruxolitinib for six weeks. A decision between Mr. B, and the medical team was made, and he underwent a splenectomy, with clear communication of the plan of care among the MPN team, transplant team, local hematologist, and general surgeon. Mr. B was properly monitored throughout this process; received dose adjustment of ruxolitinib, transfusion supports, and vaccination pre-splenectomy; and proceeded to transplant post-splenectomy in a timely manner.

Case Study Two

Mr. P’s clinical situation highlights a more typical example of the MPN shared-care program. Mr. P’s disease trajectory is illustrated in Figure 2B. At age 25, Mr. P was found to have elevated platelet counts via routine blood work. A further haematological work-up confirmed the diagnosis of ET.

Figure 2B.

Care Trajectories

Mr. P has been monitored by his local haematologist over the years. At age 55, he developed left papillary carcinoma, which led to radical nephrectomy. He was being followed by nephrology. Shortly thereafter, Mr. P developed shortness of breath and presented to his local emergency department. Here he was diagnosed with pericardial effusion that required draining. Unfortunately, the pericardial effusions re-occurred, requiring readmission to hospital. Concurrently Mr. P began to experience a decrease in blood counts, with worsening fatigue and constitutional symptoms. During his hospitalization a bone marrow biopsy was performed and reviewed locally, which did not conclude disease progression to MF.

After receiving a referral for Mr. P and considering his reported symptom burden, possible disease progression to MF, and re-current pericardial effusions, we felt that there was urgency to bring him to our clinic. Hence, he was prioritized to come to the MPN program clinic sooner.

Through a consultation appointment with the MPN program at PM, a diagnosis of PET-MF was confirmed by coordinating review of bone marrow slides. The pericardial fluid samples were also reviewed and it was determined he had extramedullary hematopoiesis. After confirmation of the diagnosis, JAK-inhibitor therapy was initiated. This information was communicated to all his health care providers through clinic notes and email, resulting in clear and transparent understanding of Mr. P’s treatment goals and each discipline’s role is in his ongoing care. Mr. P’s local haematologist continues to remain involved with his care for monitoring and management of his MPN, thus decreasing the number of return visits to PM. This translates to a decrease in commute time, less disruption to his daily life, and lesser burden on his primary caregiver to attend appointments with him. The cardiology team’s understanding of Mr. P’s clinical situation prevented further invasive cardiac procedures, while ensuring they continued to be involved in his care to monitor and optimize cardiovascular concerns.

In summary, both case studies illustrate the complexities that can arise for patients with MPNs not only from the underlying MPN but also from the associated co-morbidities, the multiple medical disciplines involved, and how easily care can become fragmented and overwhelming for the patient. Through a shared-care approach with proper coordination of care in place, a patient can receive specialized MPN care that may not be available at their local cancer centre, clarification of their diagnosis, and access to clinical trials and/or novel therapies. All of this can be done while receiving supportive care at their local cancer centre. Care coordination ensures the treatment plan and next steps are communicated to all members of the health care team, and allows for more cohesive care.

MPN shared-care model: lessons learned

The MPN program at PM implemented the shared-care model in 2014. For shared care to succeed, dedicated resources are needed, including a single point of contact, proper care coordination, facilitation of ongoing open communication, and clear expectations of roles and responsibilities amongst various healthcare providers. Table 1 briefly summarizes the needs and solutions to enable shared-care success, based on our experience at PM.

Table 1.

Lessons learned to support shared-care success

| Needs | Solutions to enable shared-care success |

|---|---|

| Dedicated resources |

|

| Point of contact/dedicated team member |

|

| Clear, concise and timely communication between all stakeholders |

|

| Patient and caregiver acceptance of shared-care |

|

| Community partners’ acceptance and capacity (staffing skill set, and resources) |

|

| Standardization: From treatment protocol, referral, to patient education material |

|

| Psychosocial and financial support |

|

To ensure clear, consistent and timely communication and proper care coordination, the MPN shared-care model established a CNS role to assist and facilitate the shared-care process. The CNS is a masters’ prepared nurse with advanced clinical assessment skills and extensive MPN knowledge; the CNS is involved in all aspects of patient care and works collaboratively with the MPN physician team. The role involves triaging new MPN patient referrals, engaging in initial consultations and follow-up of MPN patients in the clinic, and providing education to patients and caregivers regarding MPN diagnosis, treatment options, supportive care, family planning, and symptom management. The CNS also works with patients to facilitate and coordinate care closer to home. Furthermore, given the CNS’s broad scope of practice, the CNS also serves as a resource and point of contact for patients and their caregivers, as well as point-of-care nurses, when they have concerns regarding further clarification and management specific to the MPN, its symptoms, and/or concerns surrounding medications and side effects. The malignant hematology clinics at PM also have a clinic nurse triage phone line serving as secondary support for patient symptom management and medication renewal.

With the broadened scope of practice, level of involvement in patient care and dedicated time to the MPN program, the CNS is well positioned to be a single point of contact (Khera et al., 2017), connecting the patient to care providers and ensuring information is shared across the multi-disciplinary team within and outside PM.

Clear guidelines about shared-care are crucial, including expectations and responsibilities for the local team and its benefits in co-managing patient care. The MPN program at PM has standardized the referral and triage processes to ensure efficiency and accuracy in referral prioritization (Khera et al., 2017; Tomasone et al., 2017). Figure 1B illustrates the workflow for triaging in the MPN program. This includes the implementation of a triage and referral template (Supp. Figures 1 and 2). These standardized processes are communicated to our shared-care providers through our referral form to ensure all relevant clinical information is provided to facilitate appropriate triage. Letters are provided to referring centres outlining the acceptance of their patient and establishing expectations of shared-care.

Because patients and their caregivers are key stakeholders in shared-care, ensuring they understand the value and benefit of shared-care is important. Clear communication and expectation of shared-care is provided when the patient is contacted for their initial appointment.

Knowledge translation (Nielsen et al., 2003) and equipping local shared-care partners with the appropriate resources are essential steps to enable ongoing provisional management and supportive care for MPN patients (Khera et al., 2017), and instill confidence in patients about their local care team. Knowledge translation also helps ensure practice is standardized and instils confidence in patients about receiving shared-care. The MPN program at PM uses multiple methods to support knowledge translation with shared care partners. For example, we provide education/in-service sessions to the local team with updates regarding management of MPNs. During these education sessions/in-services, the local team is encouraged to provide an MPN case they would like to discuss regarding diagnosis, treatment and management. Additionally, MPN team members are accessible to our local shared-care partners through email and phone, for either discussion of ongoing shared-care patient management, or complex new patients the local shared-care partner has encountered. Clinic notes also facilitate knowledge translation, ensuring continuous communication regarding shared-care patients. It is important the MPN team and local shared-care partner are both aware of the plan of care.

Another method of knowledge translation used in the MPN program is the MPN eSIMPLE online application, launched in 2016. The application is a collaborative initiative between the Canadian MPN Group and Novartis. The application is accessible through a website, as well as a mobile application, and serves as a resource for local shared-care partners, patients, and caregivers. MPN eSIMPLE consists of educational material on PV, ET and MF treatment options, and risk stratification calculators. Supplementary Figure 3 illustrates national and international usage of the site.

EVALUATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

Every model and program needs continuous evaluation to measure its effectiveness (Khera et al., 2017). Capturing successes and benefits to shared-care, and areas of improvement allows stakeholders to see the effectiveness of the model (Khera et al., 2017; Schultz et al., 2013; McWilliam, 2016). Factors such as decreases in cost, travel distance, and health care utilization (i.e., hospital admissions, emergency department visits) cannot be the only parameters used to assess a model’s effectiveness; patient experience and satisfaction in care, patient safety, change in health behaviour and knowledge, and reduction in disruption to daily life must also be assessed (McWilliam, 2016; Hershenfeld et al., 2017).

We anticipate the above parameters can also be used to evaluate the MPN shared-care model, which can take the format of a questionnaire. The MPN program is currently developing an evaluation tool to examine patient and caregiver experience of shared-care. The information collected will help the team identify areas of success, those requiring improvement, and guide the program’s future initiatives.

MPN is a rare chronic cancer, with potential to transform to an acute leukemia. A shared-care model with appropriate care coordination facilitates disease monitoring between local providers and specialized oncology teams. This can ensure effective disease management and treatment modification should complications arise in the patient’s disease trajectory. This collaborative and high-quality coordinated care model may also be applicable with other rare chronic diseases.

Supplementary Data

MPN Referral form

MPN Triaging form

Pageviews of the MPN eSIMPLE website from 2016 to Nov 2018

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would like to thank all the leukemia nurses in the ambulatory clinic for their ongoing support in our clinics and with the triage line.

REFERENCES

- Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, Bloomfield CD, Cazzola M, Vardiman JW. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasm and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127(20):2391–2405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzell JL, Spurlock A, McBride M. Matching the unmet needs of cancer survivors to resources using a shared care model. Journal of Cancer Education. 2015;30:312–218. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0708-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chumbler NR, Kobb R, Harris L, Richardson LC, Darkins A, Sberna M, Dixit N, Ryan P, Donaldson M, Krebs GL. Healthcare utilization among veternas undergoing cChemotherapy – The impact of a cancer care coordination/hometelehealth program. Journal of Ambulatory Care Managment. 2007;30(4):308–317. doi: 10.1097/01.JAC.0000290399.43543.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin R, Siddiq NM. Myeloproliferative Neoplasms (MPN): A guide for patients & families. University Health Network; Toronto: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott MA, Tefferi A. Thrombosis and haemorrhage in polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythaemia. British Journal of Haematology. 2004;128:275–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girault A, Ferrua M, Lalloue B, Sicotte C, Fourcade A, Yatim F, Hebert G, Di Palma M, Minivielle E. Internet-based technologies to improve cancer care coordination: Current use and attitudes among cancer patients. European Journal of Cancer. 2015;51:551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorin SS, Haggstrom D, Han PKJ, Fairfield KM, Krebs P, Clauser SB. Cancer care coordination: A systematic review and meta-analysis of over 30 years of empirical studies. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2017;51(4):532–546. doi: 10.1007/s12160-017-9876-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SJ, Samuel LM, Murchie P. Toward shared care for people with cancer: developing the model with patients and GPs. Family Practice. 2011;28:554–564. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmr012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison CN, Koschmieder S, Foltz L, Guglielmelli P, Flindt T, Koehler M, Mathias J, Komatsu N, Boothroyd RN, Spierer A, Ronco JP, Taylor-Stokes G, Waller J, Mesa RA. The impact of myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) on patient quality of life and productivity: results from the international MPN Landmark survey. Annals of Hematology. 2017;96(10):1653–1665. doi: 10.1007/s00277-017-3082-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershenfeld SA, Maki K, Rothfels L, Murray CS, Nixon S, Schimmer AD, Doherty MC. Sharing post-AML consolidation supportive therapy with local centres reduces patient travel burden without compromising outcomes. Leukemia Research. 2017;50:93–96. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2017.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khera N, Martin P, Edsall K, Bonagura A, Burns LJ, Juckett M, King O, LeMaistre CF, Majhail NS. Patient-centered care coordination in hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood advances. 2017;1(19):1617–1627. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017008789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin K. Risk factors for and management of MPN-associated bleeding and thrombosis. Current Hematologic Malignancy Reports. 2017;12(5):389–396. doi: 10.1007/s11899-017-0400-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams JM. Cost containment and the tale of care coordination. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;375(23):2218–2220. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1610821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta J, Wang H, Iqbal SU, Mesa R. Epidemiology of myeloproliferative neoplasms in the United States. Leukemia & Lymphoma. 2014;55(3):595–600. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.813500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra D, Kaye JA, Piecoro LT, Brown J, Reith K, Mughal TI, Sarlis NJ. Symptom burden and splenomegaly in patients with myelofibrosis in the United States: A retrospective medical record review. Cancer Medicine. 2013;2(6):889–898. doi: 10.1002/cam4.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mughal TI, Vaddi K, Sarlis NJ, Verstovsek S. Myelofibrosis-associated complications: Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and effects on outcomes. International Journal of General Medicine. 2014;7:89–101. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S51800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen JD, Palshof T, Mainz J, Jensen AB, Olesen F. Randomized controlled trials of a shared care programme for newly referred cancer patients: bridging the gap between general practice and hospital. Quality & Safety in Health Care. 2003;12(4):263–272. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.4.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz EM, Pineda N, Lonhart J, Davies SM, McDonald KM. A systematic review of the care coordination measurement landscape. BMC Health Service Research. 2013;13(119):1–12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Allwright S, O’Dowd T. Does sharing care across the primary-speciality interface improve outcomes in chronic diseases? A systematic review. American Journal of Managed Care. 2008;14:213–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasone JR, Vukmirovic M, Brouwers MC, Grunfeld E, Urquhart R, O’Brien MA, Walker M, Webster F, Fitch M. Challenges and insights in implementing coordinated care between oncology and primary care providers: A Canadian perspective. Current Oncology. 2017;24(2):120–123. doi: 10.3747/co.24.3426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

MPN Referral form

MPN Triaging form

Pageviews of the MPN eSIMPLE website from 2016 to Nov 2018