Abstract

The incidence and prevalence of cancer continues to rise throughout Canada. Approximately one in two Canadians are expected to develop cancer at some point in their lives (Canadian Cancer Society, 2021). As the complexity and acuity of individuals with cancer increases, there is increased necessity to define the ideal nurse-to-patient ratio and patient caseload for nurses in specialized oncology settings. Two senior nurse leaders, faced with the need to determine the most appropriate model to inform the nursing model of care within their respective care areas, collaborated and decided to implement the Synergy Model.

The Synergy Model is a professional practice model developed by the American Association of Critical Care Nurses (AACN). In the Synergy Model, nursing care reflects the integration of nurses’ knowledge, skills, attitudes, competencies, and experience to meet the needs of patients and families (Curley, 2007). This model provides a framework for matching nursing resources based on patient care needs and has been adapted in various care settings. The model, however, has not been applied in a surgical oncology inpatient unit or in an oncology ambulatory care setting. Using a quality improvement methodology, the Synergy Model was piloted in these new areas and found to be effective. The Synergy Model can be utilized to determine the need for additional nursing resources with specialized oncology nurses and appropriate skill mix of intraprofessional nursing teams. It can also be used to assess adult oncology patients who present to the ambulatory systemic care suite for unscheduled care related to symptomatic concerns.

BACKGROUND

Healthcare leaders are being challenged to implement models of care (MOC) that will improve health service delivery, promote quality care, and improve patient, caregiver, and provider satisfaction. ‘Model of care’ is defined as a multidimensional patient-centred concept that defines healthcare service delivery, role determination, governance, and development of role relationships with patients, family, and members of the healthcare team (Lee & Fitzgerald, 2013). In designing a new MOC, issues to be considered relate to ensuring patients receive the right care, at the right time, by the right team, and in the right place (Booker et al., 2016).

There is a heightened need to explore new nursing models of care in oncology because of the increasing complexity of cancer patients’ needs, the colliding costs of care, and the requirement for supportive treatments. The challenge is to balance these factors between providing high-quality care and providing appropriate resource allocation with highly skilled oncology care providers. Nurse leaders from two different organizations who were faced with these issues within their respective clinical areas collaborated to find a solution.

The Synergy Model had been successfully piloted in an inpatient Hematology/Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant (HSCT) Unit at the Juravinski Hospital in Ontario with positive results (Amenudzie et al., 2017). However, the model had not yet been tested in a surgical oncology inpatient unit with a nursing skills mix model (e.g., Registered Nurses and Registered Practical Nurses working with unregulated healthcare workers), nor in an outpatient oncology ambulatory setting. Therefore, as we set forth on our journey, we wanted to answer two specific questions:

Can the Synergy Model be applied in an inpatient surgical oncology unit to inform the nursing model of care?

Can the Synergy Model be applied in an outpatient oncology ambulatory clinic to inform the nursing model of care? In this paper, we will describe how we applied the Synergy Model to inform the nursing model of care in the inpatient and ambulatory oncology care settings from two different organizations, using a quality improvement process. We will also discuss the changes that occurred as a result of implementing the model in our respective sites and share the lessons we learned in the process.

WHAT IS THE SYNERGY MODEL?

The Synergy Model is a nursing professional practice model developed by the American Association of Critical Care Nurses (AACN). It is based on eight universal characteristics: stability, complexity, predictability, resilience, vulnerability, participation in decision making, participation in care, and resource availability. Application of the model is a means for nurses to articulate patient characteristics and consider the respective impact on workload, ultimately determining the most appropriate nurse to meet the patient care needs. Depending on the clinical area, it can be used as a decision-making tool daily at every shift, or for long-term planning by leaders and administrators. Underpinned by an empowerment model, the Synergy Model can be successfully implemented by point of care nurses in their areas. In Canada, the Synergy Model has been implemented in various care settings in B.C., Saskatchewan, and Ontario, including in emergency department, and acute care, mental health, residential care, and community health settings.

The Synergy Model has two components: patient care needs and staff competency. For our project, we added a third component, the environment, to align with the College of Nurses of Ontario’s three-factor framework: the client, the nurse, and the environment (CNO, 2018). The addition of the environmental factor is needed to provide us with a better understanding of the context to which care is provided. When all three components are defined, then care needs are determined; when care needs are determined, then the most appropriate nurse to care for the patient can be identified. In turn, this helps inform decisions related to nursing skill mix, and intraprofessional nursing resource allocation.

For our project, we developed surveys or tools for each components of the model. All of the surveys and tools developed for each component of the Synergy Model are administered at various points over time, in order to determine whether any changes being made are effective. Staff engagement and an understanding of the dynamic nature of oncology care settings are essential components of the Synergy Model. Generally, the tools and surveys are administered at baseline, one month following change implementation, and six months after the implementation.

Patient Care Needs

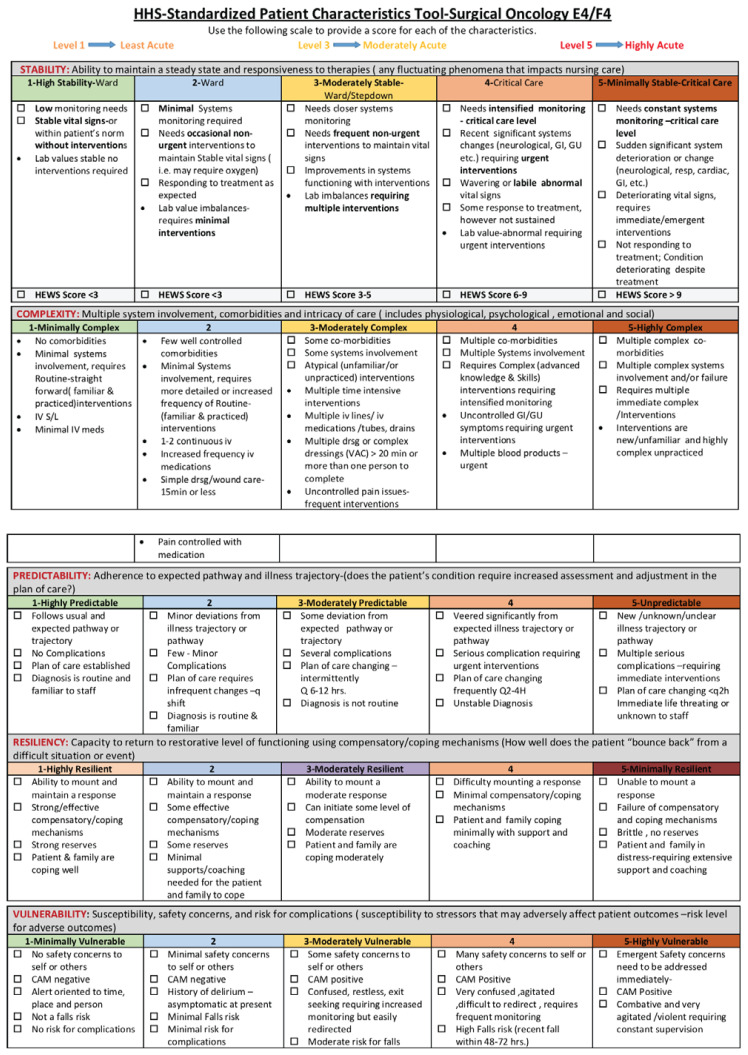

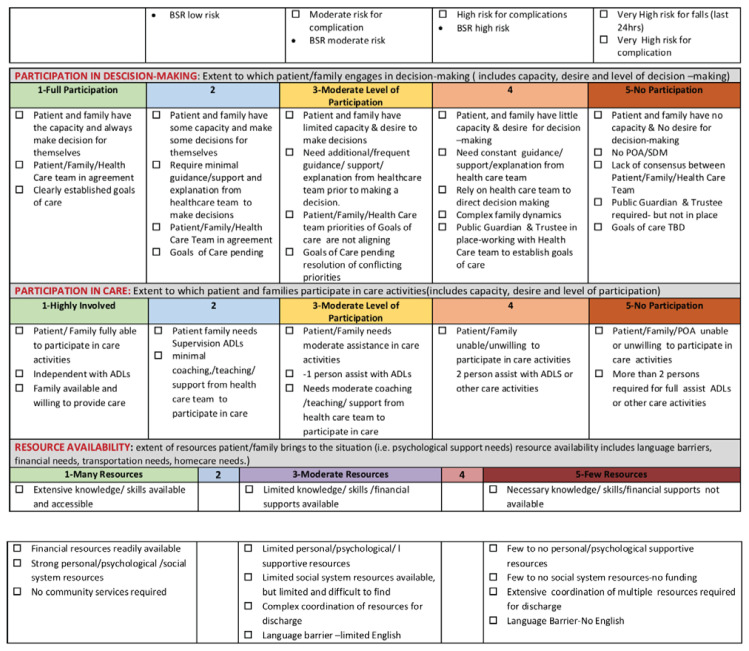

Patient care needs is one of the components of the Synergy Model. The needs are defined using eight characteristics, grouped into two categories: patient acuity and patient capability. Acuity is characterized by the patient’s level of stability, complexity, and predictability. Capability is characterized by the patient’s level of resilience, vulnerability, resource availability, decision-making, and participation in care. These characteristics are measured using a Patient Characteristics Tool, originally developed by McPhee at al. (2011). Each characteristic is further defined and measured using a five-point Likert scale, with ‘1’ being ‘high’ care needs, and ‘5’ being ‘low’. This tool uses the same approach as the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS, 2016), a standardized tool used in triaging patients presenting in the Emergency Department. The inpatient unit surgical oncology unit that applied the Synergy Model in this project, used an adapted version of the original Patient Characteristics Tool, where the scale is reversed, such that a score of ‘1’ means having a ‘low’ care need, and ‘5’ means ‘high’. The revised tool adapted by the project team was tested for face and content validity as described by Ho et al. (2017).

Staff Competency

As part of the Synergy Model, it is important to assess nursing competencies to determine the nurses’ skill level or expertise. A competency assessment tool was created for this project and nurses were asked to self-rate their skills. Staffing guidelines offer another tool that is generally created, based on the nurses’ competency, and matching their competencies with the patient’s care needs. When the level of nursing expertise is determined, it enables a well-balanced set of nurses on the unit, determined by the needs of the patient population served (Curley, 2017). In addition, a well-rounded team composition, inclusive of a range of novice to expert competencies, and intraprofessional collaboration are key enablers to support a high-functioning nursing team.

Work Environment

Understanding of the environment in which care is provided is important to understand issues that exists for nurses. The Synergy Model uses empowerment methods to support nurses with change, enabling them to determine solutions themselves that would work best for their unit. Nurses’ perspectives of their assignments, workload, and other factors are obtained using a patient assignment survey and a work environment survey.

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

There is limited literature on the outcomes of applying the Synergy Model. The Synergy Model has been applied in various contexts within clinical care settings, as well as informing the development of an undergraduate nursing curriculum and nursing staff development approaches (Curley, 2007). Curley (2007) indicated that the Synergy Model has the potential to positively affect patient and system outcomes, acknowledging achieving such outcomes would be “a challenge worth pursuing” (p. 234).

MacPhee et al. (2011) used the Synergy Model as a staff empowerment strategy, enabling staff to make real-time patient assessments at each shift to inform care planning and appropriate staffing levels. Rozdilsky and Alecxe (2012) used the Synergy Model to inform a nurse-to-patient pilot project implemented in a medicine unit, where nurses assessed each patient at every shift. Their project had positive patient outcomes, including improved nosocomial infection rates, and slightly decreased number of falls per patient days (Rozdilsky & Alecxe, 2012). Khalifehzadeh et al. (2012) conducted a quasi-experimental study applying the Synergy Model with 22 nurses and 64 patients with acute coronary syndrome in a Cardiac Intensive Care Unit to determine nursing competencies and patients’ satisfaction with their care. They reported increased patient satisfaction and improved performance of nurses in CICU following the application. Swickard et al. (2015) used the Synergy Model to determine the appropriateness of critical patients to be transported to other facilities and inform triage decisions for transport. The authors found the tool to be effective but acknowledged that studies linking their tool with measurable outcomes are still needed. Amenudzie et al. (2017) applied the Synergy Model in an inpatient hematology/HSCT unit and found positive staff and patient outcomes, such as greater nurse engagement and perceived improvement in the quality of patient care, and a reduction in safety occurrences such as patient falls and laboratory errors. Several studies utilizing the Synergy Model share similar insights: that the Synergy Model is a tool that can be used to help staff with decision-making regarding the appropriate staff (i.e., those with the right competencies) to meet patient care needs; and, as staff have the skill sets to meet patient care needs and are empowered to make decisions, staff engagement improves and patient outcomes are optimized (Curley, 1998).

In Canada, MacPhee and her colleagues in British Columbia (B.C.) were the first to implement the Synergy Model and publish their processes and results (MacPhee et al., 2011). Their work stemmed from the need to enhance nursing workload in B.C. and create a healthy work environment for nurses (British Columbia Nurses’ Union (BCNU), 2010). The toolkit published by BCNU (2010) describing detailed strategies for successful implementation of the Synergy Model, together with the work of Amenudzie et al. (2017) and Ho et al. (2017), were used to guide and inform our work. Ho et al. (2017) used a quality improvement method for implementing the Synergy Model within their organization with great results. They used a staff empowerment model and documented the impact of their work at various points in time by measuring staff satisfaction, overtime rates, and patient safety events.

OUR EXPERIENCE IMPLEMENTING THE SYNERGY MODEL

The Surgical Oncology Inpatient Care Experience

Surgical oncology inpatient units are often staffed with a nursing skill mix model, which include Registered Nurses (RNs), Registered Practical Nurses (RPNs), and Healthcare Aides (HCAs). Post-surgical patients admitted to these units require varying levels of care. For example, in the first 24 hours post-surgery, patients are typically non-mobile, acute, unpredictable, and quite complex. At 72 hours post-surgery, some patients are more independent, have more predictable care outcomes, and have moderate care needs. However, there may be some patients who have experienced complications in their recovery and require a higher level of nursing support. In a nursing skill mix model, it is often challenging to determine the right nurse for the right patient, and patient assignments for HCAs are also often hard to define.

In one surgical oncology inpatient unit, the need to find a model to help determine nursing assignments became quite evident. The unit had high overtime rates and the nursing staff were dissatisfied with the current model. The surgical oncology program in this organization consists of two units, each with 34 beds and a charge nurse. Nurses in this unit expressed concerns regarding their workload and were having difficulties articulating the care needs of their patients in an objective and standardized way. The nurses and leadership team in the program decided to pilot the Synergy Model in this unit, as a quality improvement initiative, to help address their nursing model of care delivery. The Synergy Model has been piloted in an inpatient hematology/HSCT unit with success (Amenudzie et al., 2017; Georgiou, et al., 2018). However, the model had not been tested within a surgical oncology context with a nursing skills mix model.

Developing the Patient Characteristics Tool

A team of point-of-care nurses, charge nurses, an educator, and a quality improvement specialist was organized to pilot the adapted Synergy Model. This team was championed by a point of care nurse in Surgical Oncology, and the process was supported by the unit manager and Chief of Interprofessional Practice. The Patient Characteristics Tool used in the pilot study by Amenudzie at al. (2017) was adapted by adding specific descriptors to suit the surgical oncology patient population. The new tool was evaluated for face validity and inter-rater reliability using a quality improvement process. (Refer to Appendix A.)

Nursing staff were instructed on the clinical application of the Synergy Model. The largest undertaking was related to staff training on the use of the patient characteristic tool to enable the team to adequately score their patients’ care needs. These data were collected over a two-week period to obtain a baseline score. Data were analyzed by calculating the percentage of patients with low, medium, and high care needs, and the type of care required. Having these data was important as the team understood the percentage of patients who were highly acute with unpredictable care trajectories, and those who were less acute and more predictable, but with complex care needs. These data were specifically valuable in determining the appropriateness of having RPNs and RNs on this unit. The data helped in determining which patients, based on their care need requirements, are better suited to be cared for by an RN or RPN.

Assessing Nurses’ Competencies

The competencies of the surgical oncology nursing staff were also examined. The tool to assess competencies was developed by using an adapted version of the Nursing Competencies for the Specialized Oncology Nurse (CANO, 2007). Registered Nurses (RNs) and Registered Practical Nurses (RPNs) were asked to self-assess their competencies. Based on their identified competencies and years of experience on the unit, their respective levels of expertise were determined. Results of the competency assessments were reviewed and used by the clinical educator. Based on aggregate results, the educator was able to identify knowledge and skills gaps among the nursing group on the unit, which allowed her to develop an educational plan. Unit-based in-services and learning activities were then developed which supported the learning of all nurses on the unit.

Evaluating the Work Environment Where Care is Provided

To gain the nurses’ perspectives on their patient care assignments, nurses were asked to share their experience and viewpoints on whether they thought their assignments were manageable and safe, or unmanageable and unsafe. A work environment survey was also administered. Data were collected daily over a two-week period at baseline.

Putting it all Together: Patient Care Needs, Staff Competencies, and Work Environment

Guidelines for patient assignment were created by the point-of-care nurses and charge nurses together by using the data collected from the Patient Characteristics Tool and the nurses’ competencies assessment. They were able to determine which nurses (e.g., novice) can care for which patients based on their care needs (e.g., high acuity). The nurses also developed staffing guidelines which enabled surgical staff RNs to collaborate with their manager and/or team leaders to advocate for additional nursing resources based on the acuity of the unit. Insights obtained from the results of the work environment survey and workload survey were also incorporated in this process. The team also created staffing guidelines which gave them guidance on when they could call in additional nurses, and whether an RN or RPN would be best indicated to support the team, depending on the care needs of the patients. The team went through multiple iterations to determine the right patient assignment and staffing guidelines. This was a dynamic process that promoted nurse empowerment and intraprofessional team building.

Piloting the New Staffing Guidelines

The team trialed their newly developed patient assignment and staffing guidelines for a two-week period. They also implemented three simple changes, based on the results of the work environment survey. The first change they implemented was related to the Charge Nurse coverage for both units. The team decided to pilot a staggered shift for the CNs on both units to enable a 12h CN support: One CN would work from 7am–3pm, and the second CN would work from 11am–7pm.

The second change they implemented was related to the team composition of nurses working each shift based on nurses’ experience. Nurses indicated that on some days, there were more ‘junior’ nurses, with less than two years of experience, working the same shift. This would leave the charge nurse, or the more senior nurse, with having to mentor the more junior staff, in addition to their existing workload. The team discussed this issue with their nursing colleagues, and a new schedule with a more even distribution of junior and experienced nurses on each shift was created.

The third change implemented was how the assignment for the HCA was made. Historically, the HCA would help nurses with patients’ Activities of Daily Living (ADL) if the nurses asked for help. This meant that depending on who asked for help, some nurses received support, while others did not. Newer nurses, or those who were more timid or shy about asking for help often did not receive support from the HCA. With the implementation of the Synergy Model, HCAs were given a patient assignment during their shift by the CN and based on the patients’ capability scores.

One month following implementation, nurses were asked again about their perspectives regarding their assignments. Overall, nurses indicated that they felt their assignments were significantly improved. CNs liked the new process, as they now had better guidelines to make patient assignments in a transparent manner and were better able to articulate the need to call-in additional nurses when they felt the unit was “acute”. Other nurses indicated that the Synergy Model enabled them to have a standardized language when discussing their patient care needs, and they perceived their assignments to be ‘fair’. The team did not alter its existing nursing model of care. Instead, using the Synergy Model, they had the tools to change the way in which nursing assignments were made in a transparent manner, and they changed some of the ways in which they were supported by the HCA and CN to facilitate better patient care and unit flow.

The Ambulatory Care Experience

In parallel with the quality improvement process in the surgical oncology unit of the academic teaching hospital and regional cancer program, a community hospital-affiliated out-patient oncology regional program also identified a need to consider matching nursing resources to meet the needs of individuals with cancer who were added to the systemic suite treatment area for unplanned care. Within the systemic suite there are three pods arranged to support 20 individuals to receive treatment throughout the day and booked to chair time. Specifically, the supportive treatment area was established to support eight individuals requiring same-day nursing intervention with two specialized oncology nurses during an eight-hour shift. Concerns were raised by the specialized oncology nurses that increasing complexity of treatment regimens meant the patient acuity and need for urgent ‘add on’ nursing support was increasing. They thought the nursing model should be examined to build a sustainable approach for future care delivery.

The Synergy Model was introduced to the nurses in the out-patient oncology clinic and systemic suite clinical environments by the director, manager, and educational practice lead. The specialized oncology nurses expressed interest in the model for reviewing the characteristics of patients presenting to the supportive treatment area of the systemic suite and considering future nurse-to-patient ratios and team composition. A group of fourth-year McMaster nursing students helped with providing education and support to the specialized oncology nurses regarding the Synergy Model and its three components (e.g., clinical environment, patient characteristics, nurse competency).

With a shift to quality-based funding, the ambulatory clinic environment and the activity requiring specialized oncology nursing care was reviewed from April 2016 to February 2017. Specifically, nursing activities were captured as chemotherapy administration (61%), nursing care of patients after procedures such as lumbar punctures and therapeutic thoracentesis (25%), blood transfusions (10%), and intravenous hydration for supportive care (4%).

After the educational support was completed, the specialized oncology nurses piloted the application of the Synergy Model to review patient characteristics over a 30-day period (including two long weekends) from August 2016 to September 2016. The average number of patients requiring an urgent ‘add on’ intervention in the supportive treatment area was 4.5 per day. Considering the complete eight patient characteristics of stability, complexity, predictability, level of resilience, vulnerability, resource availability, decision-making, and participation in care, the average patient characteristic score was 1.4 (with 1.0 as lower care needs and 5.0 as higher care needs). During the review, the team learned that 40% of the patients were in the supportive treatment area for longer than 2 ½ hours and the majority of the patients presented from the hematology service requiring blood transfusion support and nursing care. The average Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score for individuals cared for in the supportive treatment area was 1–2.

Review of these findings mobilized discussions on planning to add a hematology day care unit in the existing 16-bed in-patient unit within the community hospital. Considerations for staff mix opportunities for the specialized oncology RN and RPN were raised with the director and unit manager. However, the team underscored the importance of maintaining specialized oncology RNs as compliment for the delivery of parenteral chemotherapy and immunotherapy to individuals with cancer, due to ongoing advances in biomedicine and the evolution to new developments in targeted therapies. Such complexities from these treatment regimes and patient care needs require specialized oncology nurse with knowledge and competency in oncology treatment delivery. The nursing staff also emphasized the value of considering the Synergy Model for patient characteristic evaluation of all patients presenting to the systemic therapy suite. The ambulatory clinic RNs were committed to utilizing the patient characteristic evaluation in their clinic setting to assess the patient needs for unscheduled care in the future.

Thus, the pilot project of reviewing the utilization of the Synergy Model in an ambulatory oncology setting of a community-based regional cancer program was a valuable contribution to nursing empowerment. It also facilitated the consideration of the future nursing care delivery to match nursing resources to patient care needs.

DISCUSSION

Using a quality improvement process, nurse leaders and their teams were able to introduce the Synergy Model within their respective organizations. Implementing the Synergy Model enabled patient-centred decision-making and staff empowerment. Although nurse leaders played a fundamental role in introducing the model to their respective teams, having the team’s ‘buy-in’ with the model helped with its sustainability. Several learnings emerged for us from this implementation.

Using a Quality Improvement Process

Using a Quality Improvement (QI) process to drive change was an important aspect of this initiative. QI in healthcare is a systematic approach through which healthcare providers assess, develop, and implement small scale interventions to improve practice and performance, thereby improving care for patients, residents, and clients (HQO, 2012). The surgical oncology team determined that the current model of care was not working and initially had asked for more staff. However, using a QI process, the team was empowered to first understand what their problems were, and how their problems came about, before jumping to solutions. Using this method also enabled the team to understand their problems in a way that is standardized and measurable. The team collected data through surveys and time studies, analyzed the results, and identified solutions as a group. Each new solution was trialed over a two-week period. The team would then meet to determine its effectiveness and make any adjustments as needed.

This approach helped the team to systematically identify and understand their problems and identify solutions that are much more sustainable, without requiring additional financial resources. The teams were able to continue providing high-quality care and determine the right care provider based on patient care needs.

Achieving Patient-centred Decision Making Process

In patient-centred care, the patient’s preferences, needs, and values are honoured, and a biopsychosocial perspective rather than a purely biomedical perspective is applied (Greene, Tuzzio, & Cherkin, 2012). Determining the right healthcare provider to meet a patient’s care needs, requires a patient-centred decision-making process. The Synergy Model provides this methodology for leaders and clinicians. The patient characteristics tool enables clinicians to objectively determine their patients’ care needs, generating data, which can be collected and analyzed over time. This information is particularly helpful when determining the appropriate intraprofessional nursing team composition.

Empowerment of staff members

One of the concepts that underpins the Synergy Model is empowerment. For the Synergy Model to be successful, it is important to empower nurses to identify issues and identify solutions that works for them; they need to lead and make recommendations if they are to ‘own the process’. In the inpatient surgical oncology unit, the manager did not lead the process; rather, a nurse champion with experience on the Synergy Model worked with four other nurses on the unit. The point-of-care nurses involved in the project were key-opinion leaders, experienced nurses, novice nurses, and charge nurses. The group met on a bi-weekly basis to review their results, share their experiences, and determine next steps. They also played a fundamental role in discussing the project with their peers to obtain their buy-in, gather their input, and disseminate and collect surveys.

The Role of Nurse Leaders

Nurse leaders played a supportive role during the implementation of the Synergy Model in our respective sites. In the inpatient surgical oncology unit, the Chief of Interprofessional Practice (IPP) and Nurse Manager provided resources and support to the implementation team. For example, the nurses in the working group who implemented the model were provided with paid protected time to participate in the project. The Unit Manager and Chief of IPP attended meetings to help facilitate project flow, help with communication to the rest of the surgical oncology team, and remove barriers, as they arose. For example, during staff meetings and daily huddles, the Charge Nurse would discuss key aspects of the project and deadlines, and the Unit Manager helped by reinforcing the message with the staff. The Chief of IPP and Unit Manager also discussed the project with the senior leaders within their program. The supporting role the nurse leaders played was a strategic move to help nurses who were leading the implementation of the project feel empowered.

In addition, the two senior leaders from the two different sites collaborated to learn from each other’s experience. Through their bi-weekly meetings, they were able to share which strategies were successful and the lessons learned. They were able to share resources including tools that were effective in measuring the result of the changes made in implementing the model.

Challenges for Sustainability

Although implementing the Synergy Model showed improvements in nursing perspectives surrounding workload, it was hard to sustain. Success of the program requires buy-in from all staff as it includes completion of a daily assessment of their patient’s care needs, using a paper-based tool. Not all nurses would complete scores, as they thought it was additional paperwork and double documentation. For the Synergy Model to be sustainable, it is important for it to be embedded in daily work processes.

Currently, the Patient Characteristic Tool is paper based. It would have facilitated better nursing flow if it were embedded in an electronic documentation system. Another strategy to contribute to sustainability would be to ensure that CNs are actually using the scores to guide the way nursing assignments are made. It is important for staff to see that their managers and senior leaders are using the Synergy Model when making decisions about resource allocation. This allows nurses to see the value in using the model. Finally, highlighting and celebrating the successes experienced from implementing the Synergy Model, with the staff on a regular basis, signals its importance and, in turn, encourages staff with its daily use.

NEXT STEPS

In this paper, we described our journey with implementing the Synergy Model in our respective clinical areas using a quality improvement process. There is limited literature describing the impact of implementing the Synergy Model on patient and system outcomes. The Synergy Model also only focuses on the nursing perspective; with the movement toward interprofessional models of care, it would be helpful to have other health professions staff included in this work.

At Hamilton Health Sciences, we have standardized the Patient Characteristics Tool and implemented the Synergy Model on 12 different inpatient units, including oncology, rehabilitation, complex care, and medical-surgical settings. To increase our understanding about the best approaches to successfully implement the Synergy Model, a qualitative descriptive study is currently underway; the purpose is to explore the experiences of participants’ and leaders’ from the clinical units that have implemented the model. Results from this study will help us better understand the drivers and barriers to implementing the model and help design a process with easier uptake and greater sustainability.

CONCLUSION

This paper serves to demonstrate the significant opportunity for nursing leaders to cross collaborate, follow a quality improvement process, and embrace a professional practice model to inform nursing healthcare resources and innovative approaches to care in the future. The surgical oncology unit found, by implementing the Synergy Model, they increased staff engagement, decreased workload grievances, shifted conversations (i.e., from ratio to the right healthcare provider to meeting care needs), and had real time clinical decision-making tools to assign the right healthcare provider. The ambulatory systemic suite unit’s pilot using the Synergy Model demonstrated that staff engagement and staff empowerment can bring forth solutions that facilitate the notion of “right provider, right time, right place”, and highlighted the importance of professional practice and administration collaboration with front-line specialized oncology nurses. Overall, the application of the synergy tool was an approach to consider patient care needs based on the unique characteristics presented by the patient and to build nursing decision-making and resource allocation. Future opportunities for building our knowledge about the application of the Synergy Model in various oncology care settings should be explored and include members of the interprofessional healthcare team.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge Gina de los Santos RN, BScN, CMSC, Clinical Manager Oncology, Grand River Hospital for her contribution to the implementation of the model in that setting.

Appendix A.

Footnotes

Note: Both Jennifer Lounsbury and Cheryl Shoemaker were nurse leaders at Grand River Regional Cancer Centre when they implemented the Synergy Model at that organization. They are now employed at Hamilton Health Sciences, at the time of writing this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Amenudzie Y, Georgiou G, Ho E, O’Sullivan E. Adapting and applying the Synergy Model on an inpatient hematology unit. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2017;27(4):338–342. doi: 10.5737/23688076274338342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Critical Care Nurses. AACN Synergy Model for patient care. n.d. https://www.aacn.org/nursing-excellence/aacn-standards/synergy-model.

- Booker C, Turbutt A, Fox R. Model of care for a changing healthcare system: Are there foundational pillars for design? Australian Health Review: A Publication of the Australian Hospital Association. 2016;40(2):136–140. doi: 10.1071/AH14173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- British Columbia Nurses’ Union. Provincial nursing workload project resource toolkit for teams: Nursing workload and staff plan processes. 2010. https://www.bcnu.org/safeworkplace/defendprofessionalpractice/documents/pnwp_resource_toolkit.pdf.

- Canadian Cancer Society. Cancer Statistics at a Glance: Chances (probability of developing or dying from cancer. 2021. Retrieved from https://action.cancer.ca/en/research/cancer-statistics/cancer-statistics-at-a-glance.

- Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale. 2016 Revisions to the CTAS Guidelines. 2016. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/canadian-journal-of-emergency-medicine/article/revisions-to-the-canadian-emergency-department-triage-and-acuity-scale-ctas-guidelines-2016/E2CB3E2063C54E11259313FA4FEAE495.

- College of Nurses of Ontario. The RN and RPN Practice: The client, the nurse, and the environment. Practice Guideline. 2018. http://www.cno.org/globalassets/docs/prac/41062.pdf.

- Curley M. The AACN Synergy Model for Patient Care. Sigma Theta Tau International; 2007. Synergy - The unique relationship between nurses and patients. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou G, Amenudzie Y, Ho E, O’Sullivan E. Assessing the application of the Synergy Model in hematology to improve care delivery and the work environment. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2018;28(1):13–16. doi: 10.5737/236880762811316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene SM, Tuzzio L, Cherkin D. A framework for making patient-centered care front and center. The Permanente Journal. 2012;16(3):49–53. doi: 10.7812/tpp/12-025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Quality Ontario (HQO) Quality Improvement Guide. 2012. http://www.hqontario.ca/Portals/0/documents/qi/qi-quality-improve-guide-2012-en.pdf.

- Ho E, Principi E, Cordon C, Amenudzie Y, Kotwa K, Holt S, MacPhee M. The Synergy Tool: Making important quality gains within one healthcare organization. Administrative Sciences. 2017;7(32) [Google Scholar]

- Khalifehzadeh A, Jahromi MK, Yazdannik A. The impact of Synergy Model on nurses’ performance and the satisfaction of patients with acute coronary syndrome. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research. 2012;17(1):16–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Fitzgerald B. Model of care and pattern of nursing practice in ambulatory oncology. Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology. 2013;23(1):19–27. doi: 10.5737/1181912x2311922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPhee M, Wardrop A, Campbell C, Wejr P. The Synergy professional practice model and its patient characteristics tool: A staff empowerment strategy. Nursing Leadership. 2011;24(3):42–55. doi: 10.12927/cjnl.2011.22600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozdilsky J, Alecxe A. Saskatchewan: Improving patient, nursing and organizational outcomes utilizing formal nursepatient ratios. Nursing Leadership. 2012;25 doi: 10.12927/cjnl.2012.22802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swickard S, Swickard W, Winkelman C. Adaptation of the AACN Synergy Model for patient care to critical care transport. Critical Care Nurse. 2014;34(1):16–29. doi: 10.4037/ccn2014573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]