Abstract

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a major public health issue, and the aim of the present study was to identify the factors associated with GDM. Databases were searched for observational studies until August 20, 2020. Pooled odds ratios (ORs) were calculated using fixed- or random-effects models. 103 studies involving 1,826,454 pregnant women were identified. Results indicated that maternal age ≥ 25 years (OR: 2.466, 95% CI: (2.121, 2.866)), prepregnancy overweight or obese (OR: 2.637, 95% CI: (1.561, 4.453)), family history of diabetes (FHD) (OR: 2.326, 95% CI: (1.904, 2.843)), history of GDM (OR: 21.137, 95% CI: (8.785, 50.858)), macrosomia (OR: 2.539, 95% CI: (1.612, 4.000)), stillbirth (OR: 2.341, 95% CI: (1.435, 3.819)), premature delivery (OR: 3.013, 95% CI: (1.569, 5.787)), and pregestational smoking (OR: 2.322, 95% CI: (1.359, 3.967)) increased the risk of GDM with all P < 0.05, whereas history of congenital anomaly and abortion, and HIV status showed no correlation with GDM (P > 0.05). Being primigravida (OR: 0.752, 95% CI: (0.698, 0.810), P < 0.001) reduced the risk of GDM. The factors influencing GDM included maternal age ≥ 25, prepregnancy overweight or obese, FHD, history of GDM, macrosomia, stillbirth, premature delivery, pregestational smoking, and primigravida.

1. Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), defined as glucose intolerance of variable degree with onset or first recognition during pregnancy, is reported as one of the most common clinical complications of pregnancy [1, 2]. According to International Diabetes Federation (IDF) 2017, the prevalence of GDM is expected to be on the rise year by year [3]. Women with GDM may incur a potential risk of adverse outcomes [4, 5]. Mothers who have GDM are at risk of developing gestational hypertension and preeclampsia, at risk of suffering from caesarean section, and at risk of inducing subsequent type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and cardiovascular diseases [6–11]. Infants born from GDM women could be prone to abnormal fetal development such as being in macrosomia, having more congenital abnormalities, and having neonatal hypoglycemia [6, 12, 13]. Consequently, it is suggested that healthcare policy makers should be aware of the significance of GDM for early detection and further intervention.

To date, various relevant factors have been identified as predictors of GDM. Several studies have demonstrated that the frequently reported risk factors of GDM include older maternal ages, prepregnancy obesity, family history of diabetes (FHD) [14, 15], previous obstetric outcomes (e.g., macrosomia [16], stillbirth [17], abortion [18], premature delivery [19], congenital anomaly [16], being primigravida [20]), history of GDM [21], infection factors (e.g., Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) [22]), pregestational smoking [23], and socioeconomic factors (educational level, occupation, and monthly household income) [24]. However, there are other evidences suggesting that maternal age, FHD, prepregnancy overweight or obesity, previous history of abortion, stillbirth, and macrosomia showed no significant association with GDM [25, 26]. Since most of the information regarding the main factors involved in GDM lack comprehensive analysis, it is necessary to conduct a meta-analysis to further explore the potential factors responsible for GDM.

2. Materials and Methods

Our study has been approved by the Open Science Framework (OSF) registries (https://osf.io/registries), and the registration number is 10.17605/OSF.IO/4HJGN. This meta-analysis was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement. Since this study was based on a meta-analysis of published studies, it did not require patient consent and ethical approval.

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

Four online databases (Web of Science, Embase, PubMed, and Cochrane Library) were systematically searched for articles published till August 20, 2020. We searched PubMed using the following terms: “diabetes mellitus” OR “diabetes” AND “pregnancy” OR “pregnancies” OR “gestation” OR “diabetes, gestational” OR “diabetes, pregnancy-induced” OR “diabetes, pregnancy induced” OR “pregnancy induced diabetes” OR “gestational diabetes” OR “diabetes mellitus gestational” OR “gestational diabetes mellitus” AND “risk factor” OR “risk factors.”

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria include the following: (1) women with GDM (the observation group) and with healthy pregnancies (the control group); (2) the reported relevant factors in our studies including maternal age ≥ 25 years, prepregnancy overweight or obese, history of GDM, primigravida, history of congenital anomaly, FHD, history of macrosomia, HIV status, history of stillbirth, history of premature delivery, history of abortion, and pregestational smoking; and (3) observational studies.

Exclusion criteria include the following: (1) studies not published in English; (2) meta-analyses, reviews, conference summaries, case reports, letters, and guidelines; and (3) animal experiments.

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

The data were extracted by two reviewers (Yu Zhang and Cheng-Ming Xiao) independently according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. If a conflict existed, the third reviewer (Yi-Meng Gao) would join in extracting the data. The following study features were extracted from each article: the first author's name, year of publication, country, study design, maternal age (years), sample size, the number of GDM cases, and quality assessment scores. The revised Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) scale was used for cross-sectional studies to evaluate the quality of the literature, with 1-13 being low-risk of bias, and 14-20 being high-risk of bias. The modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used for case-control studies and cohort studies, and the studies with scores of 1-4 were considered low quality, while those with scores of 5-10 were considered high quality.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata 15.1 software (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). The factors were assessed by odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Heterogeneity tests were performed for each effect size, and random-effects models were adopted when I2 ≥ 50%; otherwise, fixed effects models were performed. The publication bias was estimated using Egger's test and adjusted by trim and fill method. A difference was considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search

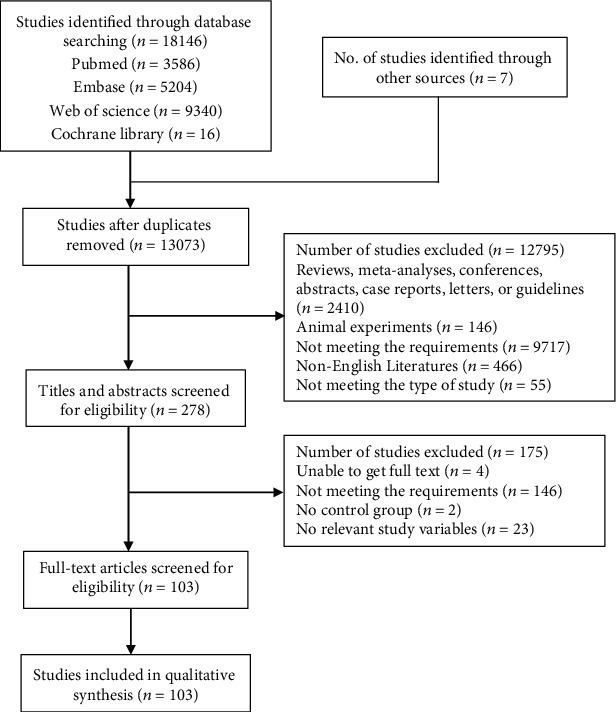

In this study, 3,586 articles were extracted from PubMed, 5,204 from Embase, 9,340 from Web of Science, 16 from the Cochrane Central, and 7 from other sources. After the removal of duplicate records (n = 13,073), 278 articles were excluded after screening of the titles and abstracts and another 103 through full-text screening for eligibility. Finally, a total of 103 studies (Supplementary Material 1) were included in our study for evaluating the relationship between these factors and GDM. The flow diagram is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of search strategy.

3.2. Study Characteristics

A total of 1,826,454 pregnant women were enrolled in this meta-analysis, divided into the observation group (with GDM) composed of 120,696 subjects and the control group (without GDM) composed of 1,705,758 subjects. In terms of the quality of our included studies, scores from the assessment by the revised NOS and JBI scales were summarized in Table 1. The quality scores ranged from 4 to 16. Of the 103 included studies, 29 articles were low quality, while 74 were high quality (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the included studies.

| Author | Year | Country | Study design | Maternal age (years) | Sample sizes | GDM cases | Quality scores |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wagaarachchi | 2001 | Sri Lanka | Case-control | — | 1004 | 41 | 5 |

| Weijers | 2002 | Amsterdam | Case-control | 25.2 ± 4.5 | 561 | 71 | 5 |

| Yang | 2002 | China | Case-control | 28.0 ± 0.28 | 9886 | 177 | 4 |

| Dempsey | 2004 | USA | Case-control | — | 541 | 155 | 6 |

| Ozumba | 2004 | Nigeria | Case-control | — | 400 | 200 | 5 |

| Zhang | 2004 | China | Case-control | — | 327 | 67 | 6 |

| Hadaegh | 2005 | Iran | Case-control | — | 700 | 62 | 6 |

| Janghorbani | 2006 | UK | Case-control | — | 3933 | 65 | 4 |

| Wijeyaratne | 2006 | Sri Lanka | Case-control | — | 442 | 274 | 5 |

| Mamabolo | 2007 | South Africa | Case-control | 29.0 ± 8.5 | 262 | 23 | 4 |

| Qiu | 2007 | USA | Case-control | 33.1 ± 0.6 | 201 | 105 | 5 |

| Cypryk | 2008 | Poland | Case-control | — | 1670 | 510 | 4 |

| Hedderson | 2008 | USA | Case-control | — | 1323 | 381 | 6 |

| Hedderson | 2008 | USA | Case-control | — | 455 | 251 | 6 |

| Murgia | 2008 | Italy | Case-control | 32.8 ± 0.2 | 1103 | 247 | 5 |

| Bhat | 2010 | India | Case-control | 26.63 ± 4.547 | 600 | 300 | 4 |

| Harizopoulou | 2010 | Greece | Cross-sectional | 33.8 ± 4.5 | 160 | 40 | 5 |

| Hedderson | 2010 | USA | Case-control | — | 1134 | 341 | 5 |

| Ogonowski | 2010 | Poland | Case-control | 30.2 ± 5.6 | 2425 | 1414 | 6 |

| Kuti | 2011 | Nigeria | Case-control | — | 765 | 106 | 4 |

| Morisset | 2011 | Canada | Case-control | 31.5 ± 5.1 | 294 | 55 | 5 |

| Qiu | 2011 | USA | Case-control | 32.9 ± 5.3 | 596 | 185 | 5 |

| Anzaku | 2013 | Nigeria | Cross-sectional | 31.2 ± 5.8 | 253 | 21 | 5 |

| Jao | 2013 | Cameroon | Cross-sectional | 30.5 (27.5-34.5) | 316 | 20 | 4 |

| Khan | 2013 | Pakistan | Case-control | 35.01 ± 4.54 | 200 | 103 | 5 |

| Fawole | 2014 | Ibadan | Cross-sectional | — | 1086 | 35 | 12 |

| Kirke | 2014 | Australia | Case-control | 30.8 ± 5.7 | 1636 | 73 | 4 |

| Mwanri | 2014 | Tanzania | Cross-sectional | — | 910 | 54 | 14 |

| Padmanabhan | 2014 | Australia | Case-control | 33.0 (29.0-36.0) | 682 | 343 | 4 |

| Rajput | 2014 | India | Case-control | 24.0 ± 3.1 | 913 | 127 | 6 |

| Tabatabaei | 2014 | Canada | Case-control | 30.8 ± 0.7 | 96 | 48 | 4 |

| Bibi | 2015 | Pakistan | Cross-sectional | — | 190 | 50 | 11 |

| Erem | 2015 | Turkey | Cross-sectional | 32.4 ± 3.9 | 815 | 39 | 15 |

| Olagbuji | 2015 | Nigeria | Cohort | — | 1059 | 91 | 5 |

| Oppong | 2015 | Ghana | Cross-sectional | — | 399 | 37 | 14 |

| Robledo | 2015 | USA | Cohort | — | 649952 | 11334 | 5 |

| Singh | 2015 | India | Case-control | 29.05 ± 3.55 | 102 | 51 | 5 |

| Bowers | 2016 | Danish | Case-control | 32.2 ± 4.3 | 699 | 350 | 4 |

| Mohan | 2016 | India | Case-control | — | 201 | 32 | 4 |

| Nasiri-Amiri | 2016 | Iran | Case-control | — | 200 | 100 | 6 |

| Tomic | 2016 | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Cross-sectional | — | 285 | 31 | 13 |

| Abdelmola | 2017 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | — | 36 | 36 | 14 |

| Anand | 2017 | Canada | Case-control | 31.2 ± 4.0 | 1006 | 365 | 6 |

| Collier | 2017 | UK | Case-control | — | 47290 | 973 | 4 |

| Farina | 2017 | Italy | Case-control | 33.5 (24-40) | 72 | 12 | 6 |

| Liu | 2017 | China | Case-control | 29 ± 5.2 | 600 | 300 | 6 |

| Mapira | 2017 | Rwanda | Cross-sectional | — | 288 | 24 | 5 |

| Oriji | 2017 | Nigeria | Case-control | — | 235 | 35 | 5 |

| Rawal | 2017 | USA | Case-control | 30.5 ± 5.7 | 321 | 107 | 5 |

| Sedaghat | 2017 | Iran | Case-control | 29.64 ± 4.52 | 388 | 122 | 6 |

| Sugiyama | 2017 | Palau | Case-control | — | 1730 | 95 | 5 |

| Bartakova | 2018 | Czech | Case-control | 33 (29-36) | 363 | 293 | 4 |

| Egbe | 2018 | Cameroon | Cross-sectional | — | 200 | 41 | 13 |

| Feleke | 2018 | Ethiopia | Case-control | — | 2257 | 567 | 5 |

| Larrabure-Torrealva | 2018 | America | Cross-sectional | 29.83 ± 6.49 | 1300 | 205 | 15 |

| Macaulay | 2018 | South Africa | Cohort | 31 (27-36) | 741 | 83 | 7 |

| Macaulay | 2018 | South Africa | Cross-sectional | 31 (27-36) | 1900 | 174 | 15 |

| Mak | 2018 | China | Cohort | 26.8 ± 4.2 | 1337 | 199 | 6 |

| Nhidza | 2018 | Zimbabwe | Cross-sectional | — | 150 | 10 | 5 |

| Wu | 2018 | China | Case-control | 32.0 ± 4.32 | 4959 | 1080 | 6 |

| Xiao | 2018 | China | Case-control | 32 (29-34) | 1585 | 599 | 5 |

| Zaman | 2018 | Iran | Cross-sectional | 29.72 ± 5.34 | 520 | 260 | 16 |

| Abualhamael | 2019 | Saudi Arabia | Case-control | 33.4 ± 5.9 | 196 | 103 | 7 |

| Agah | 2019 | Iran | Cross-sectional | — | 609 | 28 | 14 |

| Asadi | 2019 | Iran | Case-control | 29.00 ± 5.17 | 278 | 130 | 6 |

| Chakkalakal | 2019 | Tennessee | Case-control | 29.27 ± 5.14 | 89 | 40 | 4 |

| Chen | 2019 | China | Case-control | — | 9556 | 1464 | 4 |

| Chen | 2019 | China | Case-control | 31.28 ± 4.66 | 249 | 123 | 5 |

| Hrolfsdottir | 2019 | Iceland | Cohort | 31.8 ± 5.4 | 1651 | 264 | 6 |

| Hu | 2019 | China | Cohort | — | 1014 | 238 | 5 |

| Huo | 2019 | China | Case-control | 29.2 ± 2.7 | 486 | 243 | 7 |

| Ijas | 2019 | Finland | Cohort | — | 24577 | 5680 | 5 |

| Kouhkan | 2019 | Iran | Case-control | 32.15 ± 5.07 | 270 | 135 | 6 |

| Li | 2019 | China | Case-control | 30.03 ± 3.73 | 496 | 248 | 4 |

| Mak | 2019 | China | Cohort | 27.4 ± 4.3 | 1449 | 229 | 6 |

| Muche | 2019 | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional | — | 1027 | 131 | 12 |

| Olmedo-Requena | 2019 | Spain | Cross-sectional | 33.5 ± 5.5 | 1466 | 291 | 16 |

| Rajasekar | 2019 | Vellore | Cross-sectional | 253.27 ± 4.42 | 225 | 75 | 16 |

| Rajput | 2019 | India | Case-control | 25.94 ± 4.90 | 100 | 50 | 7 |

| Telejko | 2019 | Poland | Cohort | 31 (27-35) | 1508 | 397 | 7 |

| Wan (China) | 2019 | China | Case-control | 32.7 ± 4.9 | 3419 | 398 | 5 |

| Wan (Australia) | 2019 | Australia | Case-control | 31.9 ± 5.6 | 28594 | 1181 | 5 |

| Wang | 2019 | China | Case-control | 31.00 ± 4.53 | 1552 | 776 | 7 |

| Yan | 2019 | China | Cohort | 30.1 ± 4.5 | 78572 | 13846 | 7 |

| Yen | 2019 | China | Cohort | — | 527 | 74 | 5 |

| Zahra | 2019 | Pakistan | Case-control | — | 200 | 103 | 5 |

| Zhang | 2019 | China | Cohort | 29.0 (27-32) | 2093 | 241 | 5 |

| Zhu | 2019 | China | Case-control | 28.1 ± 4.4 | 3110 | 399 | 5 |

| Zhu | 2019 | China | Case-control | 27.9 ± 4.3 | 3289 | 429 | 5 |

| Aburezq | 2020 | Kuwait | Cross-sectional | 31.45 ± 5.7 | 653 | 92 | 15 |

| Alsaedi | 2020 | Saudi Arabia | Case-control | 31.7 ± 6.6 | 347 | 279 | 5 |

| Bar-Zeev | 2020 | Ohio | Case-control | — | 222408 | 12897 | 5 |

| Basu | 2020 | India | Case-control | 25.78 ± 4.89 | 715 | 127 | 6 |

| Dos Santos | 2020 | Brazil | Cross-sectional | — | 2284 | 126 | 14 |

| Francis | 2020 | USA | Case-control | 30.5 ± 5.7 | 321 | 107 | 7 |

| Ganapathy | 2020 | India | Case-control | 29.54 ± 4.3 | 140 | 70 | 6 |

| Giles | 2020 | Australia | Cross-sectional | — | 671227 | 54805 | 12 |

| Kong | 2020 | China | Cohort | 27.9 ± 3.1 | 1441 | 114 | 6 |

| Lan | 2020 | China | Cohort | 29.6 ± 4.2 | 1910 | 620 | 6 |

| Li | 2020 | China | Case-control | 30.6 ± 4.4 | 610 | 305 | 5 |

| Mishra | 2020 | India | Case-control | — | 373 | 100 | 5 |

| Rayis | 2020 | Saudi Arabia | Case-control | 30 (25-34) | 259 | 48 | 4 |

| Siddiqui | 2020 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | 32.9 ± 5.5 | 218 | 53 | 16 |

| Yong | 2020 | The Netherlands | Cohort | 29.80 ± 4.39 | 452 | 48 | 5 |

GDM: gestational diabetes mellitus.

The numbers of the included studies according to different factors are as follows: maternal age (years) ≥ 25, n = 36; prepregnancy overweight or obese, n = 48; history of GDM, n = 24; primigravida, n = 56; history of congenital anomaly, n = 3; FHD, n = 74; history of macrosomia, n = 26; HIV status, n = 4; history of stillbirth, n = 11; history of abortion, n = 19; history of premature delivery, n = 3; and pregestational smoking, n = 9.

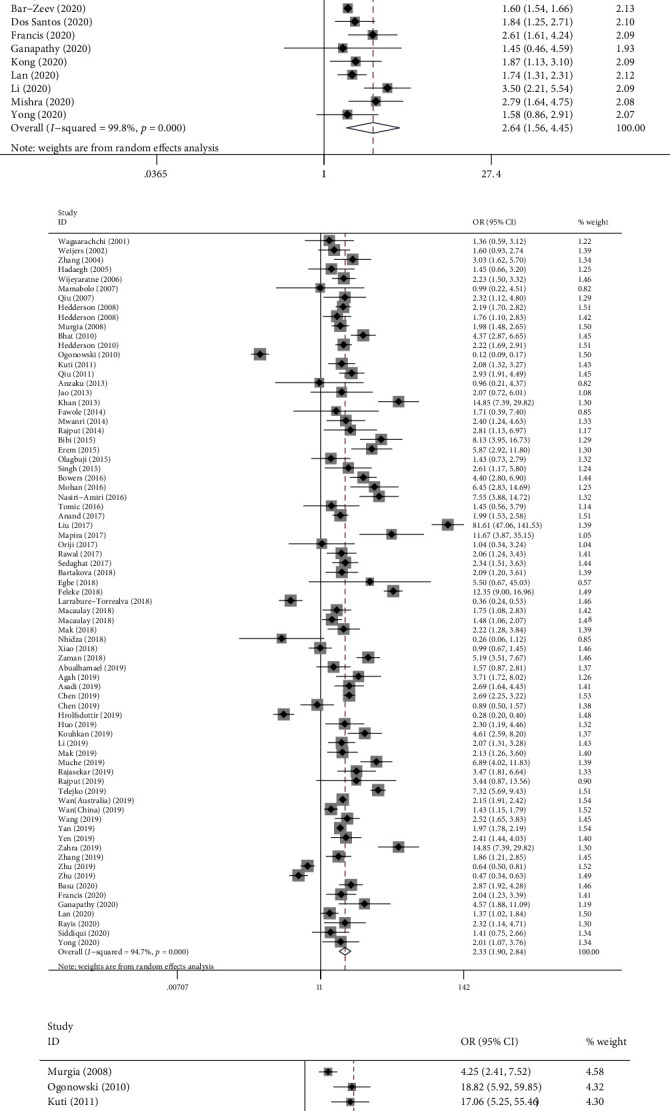

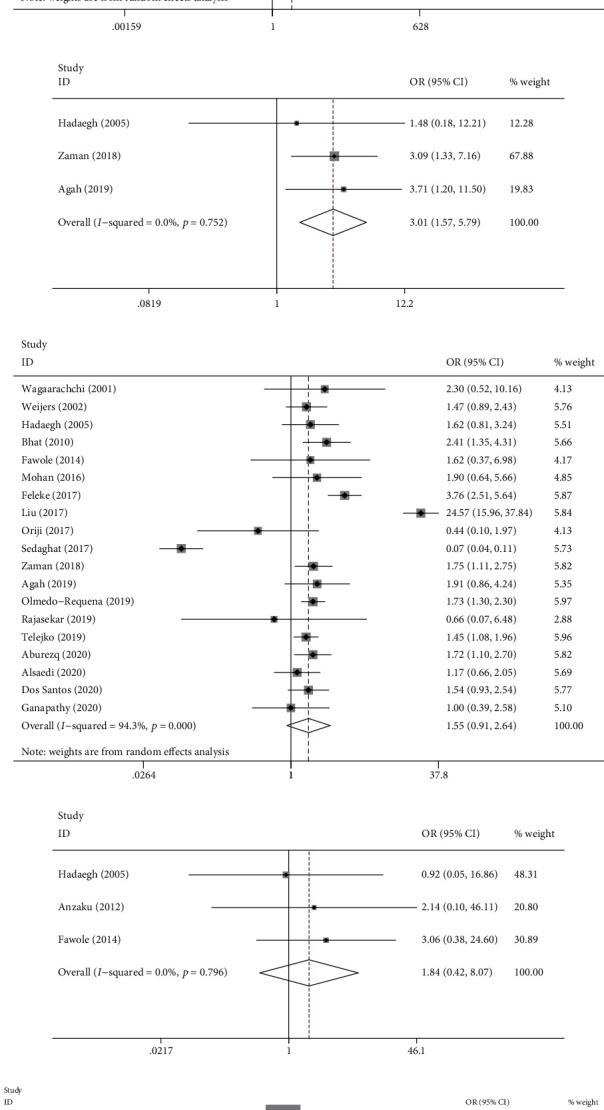

3.3. Factors Associated with GDM

The results demonstrated that maternal age ≥ 25 years (OR: 2.466, 95% CI: (2.121, 2.866), P < 0.001), prepregnancy overweight or obese (OR: 2.637, 95% CI: (1.561, 4.453), P < 0.001), history of GDM (OR: 21.137, 95% CI: (8.785, 50.858), P < 0.001), FHD (OR: 2.326, 95% CI: (1.904, 2.843), P < 0.001), history of macrosomia (OR: 2.539, 95% CI: (1.612, 4.000), P < 0.001), history of stillbirth (OR: 2.341, 95% CI: (1.435, 3.819), P = 0.001), history of premature delivery (OR: 3.013, 95% CI: (1.569, 5.787), P = 0.001), and pregestational smoking (OR: 2.322, 95% CI: (1.359, 3.967), P = 0.002) were associated with a higher risk of GDM. Nonetheless, there were no significant differences in terms of the history of congenital anomaly (OR: 1.837, 95% CI: (0.418, 8.067), P = 0.421), HIV status (OR: 1.168, 95% CI: (0.902, 1.512), P = 0.238), and history of abortion (OR: 1.546, 95% CI: (0.906, 2.639), P = 0.110). In addition, being primigravida (OR: 0.752, 95% CI: (0.698, 0.810), P < 0.001) was associated with the reduced risk of GDM (Table 2, Figures 2(a)–2(f) and 3(a)–3(f)).

Table 2.

Summary of the meta-analysis of associated factors for GDM.

| No. | Factors | No. studies included | OR | 95% CI | I 2 | P heterogeneity | t | Bias P heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maternal age ≥ 25 years | 36 | 2.466 | 2.121, 2.866 | 96.2 | <0.001 | 0.19 | 0.243 |

| 2 | Prepregnancy overweight or obese | 48 | 2.637 | 1.561, 4.453 | 99.8 | <0.001 | 4.85 | 0.001 |

| 3 | FHD | 74 | 2.326 | 1.904, 2.843 | 94.7 | <0.001 | 1.83 | 0.081 |

| 4 | Primigravida | 56 | 0.752 | 0.698, 0.810 | 94.7 | <0.001 | 1.53 | 0.132 |

| 5 | History of congenital anomaly | 3 | 1.837 | 0.418, 8.067 | 0.0 | 0.421 | — | — |

| 6 | History of GDM | 24 | 21.137 | 8.785, 50.858 | 96.9 | <0.001 | 1.35 | 0.181 |

| 7 | History of macrosomia | 26 | 2.539 | 1.612, 4.000 | 86.6 | <0.001 | 2.24 | 0.035 |

| 8 | HIV status | 4 | 1.168 | 0.902, 1.512 | 0.0 | 0.238 | — | — |

| 9 | History of stillbirth | 11 | 2.341 | 1.435, 3.819 | 52.0 | 0.001 | 0.18 | 0.862 |

| 10 | History of abortion | 19 | 1.546 | 0.906, 2.639 | 94.3 | 0.110 | 0.26 | 0.800 |

| 11 | History of premature delivery | 3 | 3.013 | 1.569, 5.787 | 0.0 | 0.001 | — | — |

| 12 | Pregestational smoking | 9 | 2.322 | 1.359, 3.967 | 66.7 | 0.002 | — | — |

CI: confidence interval; FHD: family history of diabetes mellitus; GDM: gestational diabetes mellitus; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; OR: odds ratio.

Figure 2.

Forest plot for factors associated with GDM: (a) maternal age ≥ 25 years; (b) prepregnancy overweight or obese; (c) FHD; (d) history of GDM; (e) HIV status; (f) pregestational smoking.

Figure 3.

Forest plot for previous history of obstetric factors associated with GDM: (a) macrosomia; (b) stillbirth; (c) premature delivery; (d) abortion; (e) congenital anomaly; (f) primigravida.

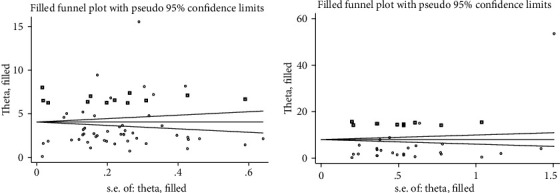

3.4. Sensitivity Analysis and Publication Bias

Sensitivity analysis of each factor was conducted, and the results were found to have stability without any difference in homogeneity and the synthesized results, despite the change of the factors that affected the results (Supplementary Material 2). Results of Egger's test indicated that there was no significant publication bias in maternal age ≥ 25 (t = 0.19, P = 0.243), history of GDM (t = 1.83, P = 0.081), primigravida (t = −1.53, P = 0.132), FHD (t = 1.35, P = 0.181), history of stillbirth (t = −0.18, P = 0.862), and history of abortion (t = −0.26, P = 0.80). Prepregnancy overweight or obese (t = 4.85, P < 0.001) and history of macrosomia (t = 2.24, P = 0.035) showed a publication bias, and after adjustments by the trim and fill method, there was no obvious asymmetry in the funnel plots, meaning no publication bias was detected (Table 2, Figures 4(a)–4(b)).

Figure 4.

Egger's funnel plot of the publication bias improved by the trim and fill method for factors of GDM: (a) prepregnancy overweight or obese and (b) history of macrosomia.

4. Discussion

In this meta-analysis of 1,826,454 pregnant women from diverse international cohorts, our findings suggested that factors such as maternal age ≥ 25 years, prepregnancy overweight or obese, pregestational smoking, FHD, previous history of GDM, macrosomia, stillbirth, and premature delivery significantly increased the risk of GDM. Besides, being primigravida was associated with a lower risk of GDM, whereas history of congenital anomaly, HIV status, and history of abortion showed no impact on the risk of GDM; controlling these relevant factors for GDM could reduce the serious increase of the occurrence of GDM.

Maternal age was reported to be closely associated with GDM. Older maternal age increased the risk of developing GDM, and the threshold for lower risks was recommended as 25 years old by the American Diabetic Association [27], similar to the result of our meta-analysis. However, other studies differed with the result mentioned above, i.e., they recommended that maternal age greater than 35 years was more prone to GDM [20, 28]. Although it is shown that there is a certain difference in the cutoff value of maternal age, there is an inevitable risk of developing GDM with the annual increase of age in modern society [29]. The reason for increasing older ages at pregnancy may be related to the implementation of the universal two-child policy, especially in China, as well as a longer period of education and better access to birth control technologies.

Prepregnancy overweight or obese was another major risk factor identified in the current study. A study conducted by Mohan and Chandrakumar also demonstrated that prepregnancy weight management could reduce a woman's risk of GDM [30]. There were other studies with similar results to ours [31, 32], despite their varieties of dietary habits and with most people consuming large amounts of alcoholic beverages. Counselling for pregnant women should emphasize the need for women to avoid sedentary lifestyles before pregnancy and to be aware of the risks of GDM to both themselves and the unborn child.

Our study also suggested that FHD (particularly in a first-degree relative) was strongly related to an increased risk of GDM, which had been observed in a previous study [33]. This was partly because of an increased susceptibility to GDM due to a genetic deficiency in insulin secretion from their first-degree relatives [34]. Therefore, it is important to emphasize that healthcare education providers must obtain accurate personal or family history from their recipients in order to identify at-risk mothers for preventing GDM.

Another significant medical factor associated with a higher risk for developing GDM was history of GDM. Interestingly, a retrospective study [35] and two case-control studies [21, 36] also had similar results showing that history of GDM was thought to be a common risk factor in repeated pregnancies [34].

Among the obstetric factors of GDM, Anzaku and Musa pointed out that women with previous history of macrosomia were the only independent risk factor for GDM in the next pregnancy [16], which was similar to our results. A case-control study indicated that women having a history of abortion increased the risk of developing GDM at the central hospitals of the Amhara region, Ethiopia [34]. In contrast to this finding, our study showed no significant association between GDM and previous history of abortion, while another study showed a similar result to ours [19]. Limited literatures reported an association between a history of fetal congenital anomaly or premature delivery and GDM. Our results, supported by a previous study, revealed that they had no link [37]. However, women who had a history of premature delivery would be prone to the development of GDM, and it can be attributed to the intrauterine damage of the mother and the fetus [38]; however, more research is required to affirm this result. The current study also indicated that pregnant women with a history of stillbirth would have a higher risk of developing GDM during future pregnancies. This finding was in line with a review conducted in Africa by Muche et al. [23]. A study conducted in Pakistan demonstrated that the incidence of GDM in primigravida Pakistani women was <1% [39]. A previous meta-analysis of 5 included studies implied that being primigravida would reduce the risk of GDM [37]. Our study of a larger trial containing 56 relevant studies has reached the same conclusion.

As for infection factors, Egbe et al. found that there were 13 out of 200 (6.5%) HIV-positive respondents through analysis, but no association between HIV and GDM was observed [17]. This finding was consistent with our meta-analysis, which was also supported by the research of Jao et al. [22] and a previous meta-analysis study conducted by Natamba et al. [37]. Because few studies have reported a link between HIV and GDM, their association still needs to be further explored through more researches.

With the exception of the most common risk factors, such as maternal age, prepregnancy overweight or obese, FHD, obstetric factors, and infection factors, this study demonstrated that there was a significant correlation between pregestational smoking and GDM. Previous studies have also noted that pregestational smoking was considered to be a risk factor, although its association has been rarely investigated at present [40]. This condition might be explained by the fact that there were several limitations in the way data collection related to smoking was conducted in our study. A recent systematic review examined the relationship between pregestational smoking and the risk of GDM, but no correlation was found [36]. The aspect of smoking in the development of GDM deserves further investigations. Possible uncontrolled confounding factors should be considered, such as the differences in socioeconomic status between groups, selection bias, or even passive smoking.

Strengths and limitations should be taken into account in further interpreting our findings. In terms of strengths, due to the high prevalence of GDM, our meta-analysis included studies conducted in different countries such as China, USA, Australia, and India, covering a number of nationwide representative populations, which to a certain extent had reduced the possible selection bias and reaching some relatively generalized conclusions. Nevertheless, the present study also had some limitations. Firstly, the role of confounding factors cannot be completely eliminated in our observational studies. Although majority of the articles included in the analysis evaluated multiple factors, limited studies have shown the association between other variables such as living quarters, substance abuse, dietary diversity, and physical activity issues with GDM. Prospective review studies need to clarify the correlation between GDM and the other factors mentioned above. Secondly, there is a high heterogeneity in our results which might also be attributed to the different demographic characteristics among populations in more than 37 countries covered by this meta-analysis. Additionally, qualitative studies about the reasons for GDM pathologically should be added in this review.

5. Conclusions

In our study, maternal age ≥ 25 years, prepregnancy overweight or obese, FHD, previous history of GDM, macrosomia, stillbirth and premature delivery, pregestational smoking, and being primigravida were considered as all independent risk factors of GDM. It is strongly recommended that all pregnant women in the future be screened early for GDM, especially those identified at higher risks of GDM, thereby leading to early diagnosis of GDM and early intervention.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants included in our study for their contributions. This work was supported by the Key Clinical Specialty Development Project of Chongqing (grant number 2012143).

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Ethical Approval

Since this study was based on a meta-analysis of published studies, it did not require patient consent and ethical approval.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Supplementary Materials

References of included studies. Sensitivity analysis: (A) maternal age ≥ 25 years; (B) prepregnancy overweight or obese; (C) FHD; (D) history of GDM; (E) HIV status; (F) pregestational smoking; (G) history of macrosomia; (H) history of stillbirth; (I) history of premature delivery; (J) history of abortion; (K) history of congenital anomaly; (L) primigravida.

References

- 1.Buchanan T. A., Xiang A. H., Page K. A. Gestational diabetes mellitus: risks and management during and after pregnancy. Nature Reviews. Endocrinology. 2012;8(11):639–649. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2012.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coustan D. R. Gestational diabetes mellitus. Clinical Chemistry. 2013;59(9):1310–1321. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.203331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cho N. H., Shaw J. E., Karuranga S., et al. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2018;138:271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2018.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kampmann U., Madsen L. R., Skajaa G. O., Iversen D. S., Moeller N., Ovesen P. Gestational diabetes: a clinical update. World Journal of Diabetes. 2015;6(8):1065–1072. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v6.i8.1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brawerman G. M., Dolinsky V. W. Therapies for gestational diabetes and their implications for maternal and offspring health: evidence from human and animal studies. Pharmacological Research. 2018;130:52–73. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metzger B. E., Coustan D. R., Trimble E. R. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Clinical Chemistry. 2019;65(7):937–938. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2019.303990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Z., Cheng Y., Wang D., et al. Incidence rate of type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 170,139 women. Journal Diabetes Research. 2020;2020, article 3076463:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2020/3076463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yogev Y., Xenakis E. M., Langer O. The association between preeclampsia and the severity of gestational diabetes: the impact of glycemic control. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;191(5):1655–1660. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.03.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marchetti D., Carrozzino D., Fraticelli F., Fulcheri M., Vitacolonna E. Quality of life in women with gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Journal Diabetes Research. 2017;2017, article 7058082:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2017/7058082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vounzoulaki E., Khunti K., Abner S. C., Tan B. K., Davies M. J., Gillies C. L. Progression to type 2 diabetes in women with a known history of gestational diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Retnakaran R., Qi Y., Connelly P. W., Sermer M., Zinman B., Hanley A. J. Glucose intolerance in pregnancy and postpartum risk of metabolic syndrome in young women. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2010;95(2):670–677. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Retnakaran R., Shah B. R. Glucose screening in pregnancy and future risk of cardiovascular disease in women: a retrospective, population-based cohort study. The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology. 2019;7(5):378–384. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clausen T. D., Mathiesen E. R., Hansen T., et al. High prevalence of type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes in adult offspring of women with gestational diabetes mellitus or type 1 diabetes: the role of intrauterine hyperglycemia. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(2):340–346. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mwanri A. W., Kinabo J., Ramaiya K., Feskens E. J. Gestational diabetes mellitus in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and metaregression on prevalence and risk factors. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2015;20(8):983–1002. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cypryk K., Szymczak W., Czupryniak L., Sobczak M., Lewiński A. Gestational diabetes mellitus—an analysis of risk factors. Endokrynologia Polska. 2008;59(5):393–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anzaku A. S., Musa J. Prevalence and associated risk factors for gestational diabetes in Jos, north-central, Nigeria. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2013;287(5):859–863. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2649-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egbe T. O., Tsaku E. S., Tchounzou R., Ngowe M. N. Prevalence and risk factors of gestational diabetes mellitus in a population of pregnant women attending three health facilities in Limbe, Cameroon: a cross-sectional study. The Pan African Medical Journal. 2018;31 doi: 10.11604/pamj.2018.31.195.17177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feleke B. E. Determinants of gestational diabetes mellitus: a case-control study. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2018;31(19):2584–2589. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2017.1347923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agah J., Roodsarabi F., Manzuri A., Amirpour M., Hosseinzadeh A. Prevalence and associated risk factors of gestational diabetes mellitus in a tertiary hospital in Iran. Clinical and Experimental Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2019;46:85–89. [Google Scholar]

- 20.dos Santos P. A., Madi J. M., da Silva E. R., de Oliveira Pereira Vergani D., de Araújo B. F., Garcia R. M. R. Gestational diabetes in the population served by Brazilian public health care. Prevalence and risk factors. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia / RBGO Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2020;42 doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1700797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ganapathy A., Holla R., Darshan B. B., et al. Determinants of gestational diabetes mellitus: a hospital-based case–control study in coastal South India. International Journal of Diabetes in Developing Countries. 2021;41 doi: 10.1007/s13410-020-00844-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jao J., Wong M., Van Dyke R. B., et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus in HIV-infected and -uninfected pregnant women in Cameroon. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(9):e141–e142. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muche A. A., Olayemi O. O., Gete Y. K. Prevalence and determinants of gestational diabetes mellitus in Africa based on the updated international diagnostic criteria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Public Health. 2019;77(1):p. 36. doi: 10.1186/s13690-019-0362-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirke A. B., Evans S. F., Walters B. N. Gestational diabetes in a rural, regional centre in south Western Australia: predictors of risk. Rural and Remote Health. 2014;14 doi: 10.22605/rrh2667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zaman F., Nouhjah S., Shahbazian H., Shahbazian N., Latifi S. M., Jahanshahi A. Risk factors of gestational diabetes mellitus using results of a prospective population-based study in Iranian pregnant women. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews. 2018;12(5):721–725. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2018.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abualhamael S., Mosli H., Baig M., Noor A. M., Alshehri F. M. Prevalence and associated risk factors of gestational diabetes mellitus at a university hospital in Saudi Arabia. Pak J Med Sci. 2019;35(2):325–329. doi: 10.12669/pjms.35.2.498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lao T. T., Ho L. F., Chan B. C., Leung W. C. Maternal age and prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(4):948–949. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.04.06.dc05-2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bibi S., Saleem U., Mahsood N. The frequency of gestational diabetes mellitus and associated risk factors at khyber teaching hospital Peshawar. Journal of Postgraduate Medical Institute. 2015;29:43–46. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y., Ren X., He L., Li J., Zhang S., Chen W. Maternal age and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of over 120 million participants. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2020;162:p. 108044. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohan M. A., Chandrakumar A. Evaluation of prevalence and risk factors of gestational diabetes in a tertiary care hospital in Kerala. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews. 2016;10(2):68–71. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yen I. W., Lee C. N., Lin M. W., et al. Overweight and obesity are associated with clustering of metabolic risk factors in early pregnancy and the risk of GDM. PLoS One. 2019;14(12, article e0225978) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu L., Han L., Zhan Y., Cui L., Chen W., Ma L. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus and associated risk factors in pregnant Chinese women: a cross-sectional study in Huangdao, Qingdao, China. Asia-Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018;27:383–388. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.032017.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moosazadeh M., Asemi Z., Lankarani K. B., et al. Family history of diabetes and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research and Reviews. 2017;11(Suppl 1):S99–s104. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2016.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen Y., Jia Y., Li Y., et al. Genetic determinants of gestational diabetes mellitus: a case-control study in two independent populations. Acta Diabetologica. 2020;57(7):843–852. doi: 10.1007/s00592-020-01485-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barnes R. A., Wong T., Ross G. P., et al. Excessive weight gain before and during gestational diabetes mellitus management: what is the impact? Diabetes Care. 2020;43(1):74–81. doi: 10.2337/dc19-0800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y. Y., Liu Y., Li C., et al. Frequency and risk factors for recurrent gestational diabetes mellitus in primiparous women: a case control study. BMC Endocrine Disorders. 2019;19(1):p. 22. doi: 10.1186/s12902-019-0349-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Natamba B. K., Namara A. A., Nyirenda M. J. Burden, risk factors and maternal and offspring outcomes of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA): a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2019;19(1):p. 450. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2593-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee K. W., Ching S. M., Ramachandran V., et al. Prevalence and risk factors of gestational diabetes mellitus in Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2018;18(1):p. 494. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-2131-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jawa A., Raza F., Qamar K., Jawad A., Akram J. Gestational diabetes mellitus is rare in primigravida Pakistani women. Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;15(3):191–193. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.83404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tabatabaei N., Giguere Y., Forest J.-C., Rodd C. J., Kremer R., Weiler H. A. Osteocalcin is higher across pregnancy in Caucasian women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Canadian Journal of Diabetes. 2014;38(5):307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

References of included studies. Sensitivity analysis: (A) maternal age ≥ 25 years; (B) prepregnancy overweight or obese; (C) FHD; (D) history of GDM; (E) HIV status; (F) pregestational smoking; (G) history of macrosomia; (H) history of stillbirth; (I) history of premature delivery; (J) history of abortion; (K) history of congenital anomaly; (L) primigravida.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.