Abstract

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has killed over 2.5 million people worldwide, but effective care and therapy have yet to be discovered. We conducted this analysis to better understand tocilizumab treatment for COVID-19 patients.

Main text

We searched major databases for manuscripts reporting the effects of tocilizumab on COVID-19 patients. A total of 25 publications were analyzed with Revman 5.3 and R for the meta-analysis. Significant better clinical outcomes were found in the tocilizumab treatment group when compared to the standard care group [odds ratio (OR) = 0.70, 95% confidential interval (C): 0.54–0.90, P = 0.007]. Tocilizumab treatment showed a stronger correlation with good prognosis among COVID-19 patients that needed mechanical ventilation (OR = 0.59, 95% CI, 0.37–0.93, P = 0.02). Among stratified analyses, reduction of overall mortality correlates with tocilizumab treatment in patients less than 65 years old (OR = 0.68, 95% CI: 0.60–0.77, P < 0.00001), and with intensive care unit patients (OR = 0.62, 95% CI: 0.55–0.70, P < 0.00001). Pooled estimates of hazard ratio showed that tocilizumab treatment predicts better overall survival in COVID-19 patients (HR = 0.45, 95% CI: 0.24–0.84, P = 0.01), especially in severe cases (HR = 0.58, 95% CI 0.49–0.68, P < 0.00001).

Conclusions

Our study shows that tocilizumab treatment is associated with a lower risk of mortality and mechanical ventilation requirement among COVID-19 patients. Tocilizumab may have substantial effectiveness in reducing mortality among COVID-19 patients, especially among critical cases. This systematic review provides an up-to-date evidence of potential therapeutic role of tocilizumab in COVID-19 management.

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40249-021-00857-w.

Keywords: Tocilizumab, COVID-19, IL-6, Cytokine storm

Background

The outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread rapidly worldwide and became a global pandemic. [1]. As of April 29, 2021, more than 149 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 have been reported to the World Health Organization (WHO), including more than 3.1 million deaths. [2].

COVID-19 can cause symptoms ranging from mild to very severe, most of COVID-19 patients present mild infection and can recover within weeks. Those who show clinical features of pneumonia, respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), hypercoagulability or septic shock, require hospitalization for management [3]. Although the pathogenesis of COVID-19 remains unclear, an accumulating body of evidence suggests that hyperinflammation with overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines is frequently observed in severe COVID-19 patients and presumably contribute to a poor prognosis [4, 5]. Elevated serum cytokines, including interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-10, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interferon-γ, may cause fatal ARDS and coagulation disorders in COVID-19 patients [6]. In particular, serum interleukin-6 elevation is strongly associated with COVID-19 severity and mortality [7]. Thus, the inhibition of IL-6 is hypothesized to be a promising therapeutic strategy to interfere with COVID-19-induced cytokine storm and thereby alter the course of disease progression.

Tocilizumab, a recombinant humanized anti-IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody, has been approved for uses in patients with rheumatologic disorders and chimeric antigen receptor T cell-induced cytokine release syndrome. Recent publications revealed clinical benefits of tocilizumab treatment in COVID-19 patients [8, 9]. The role of IL-6 inhibition in reducing COVID-19 severity and mortality, however, remains controversial because several large-scale, multi-center observations and randomized clinical trials show minimal benefits [10, 11]. It is necessary to systematically evaluate and update the effects of IL-6 inhibition among COVID-19 patients as new data are generated. Previous meta-analysis investigating tocilizumab were published before a few large, randomized control trials [12, 13]. We included all eligible publications up to this point, investigating the impact of tocilizumab on reducing mortality and intubation in COVID-19 patients.

Methods and materials

Literature search

This meta-analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Metanalysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Additional file 1: Table S1). Two authors (QW, HL) independently searched English publications in PubMed, PMC, Scopus, Google Scholar, and Web of Science. The first active search was performed on December 27, 2020, while the last was performed on March 20, 2020. We used the following keywords and the combinations in the query: “novel coronavirus” or “COVID-19” or “SARS-CoV-2” and “tocilizumab” or “IL-6 blockade” or “IL-6 receptor antagonist”. We retrieved all the references in all manuscripts for future analysis.

Selection criteria

Manuscripts were selected if they were (1) English, peer-reviewed journal articles, (2) studies reporting tocilizumab treatment in COVID-19 patients, (3) studies assigning COVID-19 patients to severity classes, (4) only studying adult patients, (5) patients’ mortality data was available in the paper. Only the most recent study was included if the same investigator published multiple studies using the same dataset.

Quality assessment

Three authors (QW, HL and RGW) assessed the entry manuscripts according to the principles adapted from Xu et al. [14]. The following items were evaluated in the assessment: the clarity of study objectives; whether or not there was a clearly stated study period (start date and end date); the description clarity of the patient selection criteria; whether the study was international or national; the stated tocilizumab treatment method and dose; whether the baseline equivalence groups were clearly considered; the definition of the primary outcome (overall mortality or mechanical ventilation requirement) prior to the study; if the follow-up period was long enough (# months); whether a clear hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) was stated; and the limitations of each study were considered. We ranked the selected papers according to the quality items used in each study (score range 0–10). Quality assessment was not used as exclusion criteria.

Data extraction

We extracted the following information from each included study in this meta-analysis: first author, study period, country, study countries, study type (retrospective or prospective), total number of patients, sex ratio in each group, age in each group, tocilizumab treatment, clinical outcomes (overall mortality and mechanical ventilation requirement), tocilizumab group positive and negative outcome numbers, control group positive and negative outcomes, and HR corresponding 95% CI if available.

Statistical analysis

Revman 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) and R programming language (http://www.R-project.org/) were used to analyze the data. During the full-paper screening process, Cohen’s kappa statistic was used to evaluate the inter-reviewer agreement. Subgroup analyses were also used to study how study areas, patient’s median age, patient’s severity, study size, and male percentage in the groups would affect tocilizumab treatment outcomes. The publication biases were assessed through Begg’s funnel plot in Revman 5.3 and Egger's test in R. Sensitivity analysis was conducted in R to find potential outliers by omitting one study at a time (also called the “one-study removed” model). Statistical heterogeneity between studies was determined by Cochran’s Q test and Higgins I square where P < 0.1 or I2 > 50% was considered as high heterogeneity and a random-effect model was used to combine the data; otherwise, a fixed-effect model was used. A two-sided P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Literature search

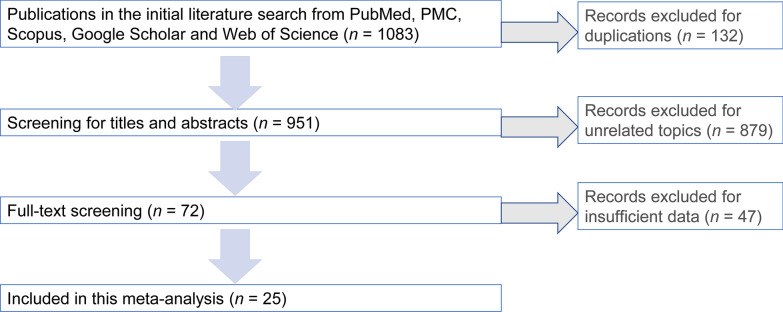

Our literature search flow chart is shown as Fig. 1. We had a total of 1083 publications in the initial literature search. After removing duplicate records, 951 were screened for more details. After scanning the titles and abstracts, 72 were included in the full-text screening. After reviewing the included papers carefully, 47 publications were excluded for insufficient data, leaving 25 publications for this meta-analysis. Cohen's kappa for inter-reviewer agreement was 0.78 for title and abstract screening and 0.81 for full-text screening. The quality of the 25 included publications was fair with an average quality score of 7.72 and a median score of 8 (range 5–10, Additional file 2: Table S2).

Fig. 1.

Flow-diagram of this meta-analysis

Literature details

Overall, 10 201 patients from 25 different publications were included in this study. Seven of the studies assessed patients from the USA [10, 15–20], 13 of the studies assessed patients from west Europe [8, 21–32], two assessed patients from multiple countries [33, 34], one assessed patients from Brazil [35], and two studies were from India [36, 37]. The main characteristics of the 25 included studies were summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

COVID-19 patients characteristics with IL-6 inhibitor Tocilizumab treatment effects

| Record | First author | Study period | Country | Study type | Total cases | Sex(M) T group | Sex(M) SOC | Age (T group) | Age (SOC) | Outcomes | T group positive outcome | SOC positive outcome | T group negative outcome | SOC negative outcome | HR (95% CI) | Tocilizumab treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Martínez-sanz | 31/01/20–23 /04/20 | Spain | Retrospective | 1229 | 191 (73%) | 574 (59%) | 65 (55–76)* | 68 (57–80)* | Overall mortality | 61 | 120 | 199 | 849 | 0.34 (0.17–0.71) | A median total dose of 600 mg |

| 1 | Martínez-sanz | 31/01/20–23 /04/20 | Spain | Retrospective | 286 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Overall mortality (crp > 150 mg/dl) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.39 (0.19–0.80) | |

| 2 | Potere | 28/03/20–21/04/20 | Italy | Retrospective case-control | 80 | 26 (65.0%) | 26 (65.0%) | 56.0 (50.3–73.2) | 54.5 (50.0–73.0) | Overall mortality | 2 | 11 | 38 | 29 | NA | 324 mg, two concomitant subcutaneous injections |

| 3 | Canziani | 23/02/20–09/05/20 | Italy | Retrospective case-control | 128 | 47 (73%) | 47 (73%) | 63 (12)* | 64 (8)* | 30-day mortality | 17 | 24 | 47 | 40 | 0.61 (0.33–1.15) | Two intravenous infusion of 8 mg/kg |

| 3 | Canziani | 23/02/20–09/05/20 | Italy | Retrospective case-control | 128 | 48 (73%) | 48 (73%) | 64 (12)* | 65 (8) | Mechanical ventilation requirement at 30 days | 9 | 29 | 55 | 35 | 0.36 (0.16–0.83) | |

| 4 | Tsai | 01/03/20–05/05/20 | USA | Retrospectiv | 132 | 46(69.7%) | 50(75.8%) | 62.38 ± 13.49* | 61.35 ± 16·09* | Overall mortality | 18 | 18 | 48 | 48 | NA | 800 mg or 600 mg or 400 mg; one or two doses |

| 5 | Roomi | 01/03/20–30/05/20 | USA | Retrospective | 176 | 60 (72.30) | 23 (27.70) | 65.48* | 58.09 | Overall mortality | 6 | 13 | 26 | 131 | NA | |

| 6 | Guaraldi | 21/02/20–30/04/20 | Italy | Retrospective | 544 | 127 (71%) | 232 (64%) | 64 (54–72) | 69 (57–78) | Overall mortality | 13 | 73 | 166 | 292 | 0·38 (0·17–0·83) | Two intravenous infusion of 8 mg/kg (up to 800 mg), 12 h apart |

| 6 | Guaraldi | 21/02/20–30/04/20 | Italy | Retrospective | 544 | 127 (71%) | 232 (64%) | 64 (54–72) | 69 (57–78) | Mechanical ventilation requirement | 33 | 57 | 146 | 308 | 0·61 (0·40–0·92) | |

| 7 | Menzella | 11/03/20–14/04/20 | Italy | Retrospective | 79 | 29 (71%) | 27 (71%) | 63.3 ± 10.6* | 70.3 ± 11.3* | Overall mortality | 10 | 20 | 31 | 18 | 0.55 (0.22–1.35) | Two intravenous infusion of 8 mg/kg (up to 800 mg), 12 h apart, or subcutaneously 2 to 4 doses of 162 mg |

| 7 | Menzella | 11/03/20–14/04/20 | Italy | Retrospective | 79 | 29 (71%) | 27 (71%) | 63.3 ± 10.6* | 70.3 ± 11.3* | Mechanical ventilation requirement | 9 | 12 | 32 | 26 | 0.44 (0.22–0.89) | |

| 8 | Salvarani | 31/03/20–11/06/20 | Italy | Prospective randomized clinical trial | 123 | 40 (66.7%) | 37 (56.1%) | 61.5 (51.5–73.5) | 60.0 (54.0–69.0) | Overall mortality at 30 days | 2 | 1 | 58 | 62 | NA | Two intravenous infusion of 8 mg/kg (up to 800 mg), 12 h apart. |

| 9 | Gupta | 04/03/20–10/05/20 | USA | Retrospective | 3924 | 299 (69.1%) | 2165 (62.0%) | 58 (48–65) | 63 (52–72) | Overall mortality | 125 | 1419 | 308 | 2072 | 0.71 (0.56–0.92) | Intravenously or subcutaneously during the first 2 days of icu admission |

| 10 | Marte | 08/03/20–25/04/20 | USA | Retrospective | 193 | 74 (77.1%) | 63 (64.9%) | 58.8 ± 13.6* | 62.0 ± 14* | Overall mortality | 43 | 55 | 53 | 42 | NA | One dose only |

| 11 | Klopfenstein | 01/03/20–13/04/20 | France | Retrospective | 45 | NA | NA | 76.8 (52–93) ± 11* | 70.7 (33–96) ± 15* | Overall mortality | 5 | 12 | 15 | 13 | NA | One or two doses |

| 11 | Klopfenstein | 01/03/20–13/04/20 | France | Retrospective | 45 | NA | NA | 76.8 (52–93) ± 11* | 70.7 (33–96) ± 15* | Mechanical ventilation | 0 | 8 | 20 | 17 | NA | |

| 12 | Biran | 01/03/20–22/04/20 | USA | Retrospective | 630 | 155 (74%) | 281 (67%) | 62 (53–71) | 65 (56–74) | Hospital-related mortality | 102 | 256 | 108 | 164 | 0.71 (0.56–0.89) | Intravenous infusion of 400 mg or 8 mg/kg |

| 13 | Campochiaro | Na | Italy | Retrospective | 65 | 29 (91%) | 27 (82%) | 64 (53 – 75) | 60 (55 – 75.5) | Overall mortality at 28th day | 5 | 11 | 27 | 22 | NA | Two intravenous infusion of 400 mg |

| 14 | Capra | 26/02/20–02/04/2020 | Italy | Retrospective | 85 | 45(73%) | 19 (83%) | 63 (54–73) | 70 (55–80) | Overall mortality | 2 | 11 | 60 | 12 | 0.035 (0.004–0.347) | 400 mg iv once, or subcutaneous 324 mg once or 800 mg iv once |

| 15 | Stone | 20/04/20–15/06/20 | USA | Prospective randomized clinical trial | 243 | 96 (60%) | 45 (55%) | 61.6 (46.4–69.7) | 56.5 (44.7–67.8) | Mechanical ventilation or death at 28 day | 17 | 10 | 144 | 72 | 0.83 (0.38–1.81) | A single dose of 8 mg/kg intravenously, up to 800 mg |

| 15 | Stone | 20/04/20–15/06/20 | USA | Prospective randomized clinical trial | 243 | 96 (60%) | 45 (55%) | 61.6 (46.4–69.7) | 56.5 (44.7–67.8) | Mechanical ventilation at 28 day | 11 | 8 | 150 | 74 | 0.65 (0.26–1.62) | |

| 16 | Kaminski | 26/03/20–18/05/20 | USA | Retrospective | 125 | 38(58%) | 45(75%) | 58.9 ± 17.9* | 57.2 ± 15 | Overall mortality at 28 day | 24 | 30 | 41 | 30 | NA | 400 mg as a single dose iv or an subcutaneous dose of 324 mg |

| 17 | Eimer | 11/03/20–15/04/20 | Sweden | Retrospective | 87 | 28 (96.6%) | 45 (77.6%) | 58.0 (49.0–63.0) | 55.0 (52.0–64.8) | 30‐day all‐cause mortality | 5 | 19 | 24 | 39 | 0.52 (0.19–1.39) | A single dose of 8 mg/kg intravenously |

| 17 | Eimer | 11/03/20–15/04/20 | Sweden | Retrospective | 87 | 28 (96.6%) | 45 (77.6%) | 58.0 (49.0–63.0) | 55.0 (52.0–64.8) | Mechanical ventilation | 24 | 53 | 5 | 5 | NA | |

| 18 | Salama | Until 30/09/2020 | International | Prospective randomized clinical trial | 377 | 150 (60.2%) | 73 (57.0%) | 56.0 ± 14.3* | 55.6 ± 14.9* | Mechanical ventilation or death by day 28 | 30 | 25 | 219 | 103 | 0.56 (0.33–0.97) | Two doses of intravenous (8 mg/kg, up to 800 mg) |

| 18 | Salama | Until 30/09/2020 | International | Prospective randomized clinical trial | 377 | 150 (60.2%) | 73 (57.0%) | 56.0 ± 14.3* | 55.6 ± 14.9* | Death at day 28 | 26 | 11 | 223 | 117 | NA | |

| 19 | Remap–cap | Until 17/06/2020 | UK | Prospective randomized clinical trial | 755 | 261 (74%) | 283 (70%) | 61.5 ± 12.5* | 61.1 ± 12.8* | In–hospital death | 98 | 142 | 252 | 255 | 0.56(0.33–0.97) | 8 mg/kg (up to 800 mg) |

| 20 | Rosas | 03/04/20–28/05/20 | International | Prospective | 438 | 205 (69.7%) | 101 (70.1%) | 60.9 ± 14.6* | 60.6 ± 13.7* | Death at day 28 | 58 | 28 | 236 | 116 | 0.3 (-7.6 to 8.2) | 8 mg/kg (up to 800 mg) |

| 21 | Hermine | 31/03/20–18/04/20 | France | Prospective | 130 | 44 (70%) | 44 (66%) | 64.0 (57.1–74.3) | 63.3 (57.1–72.3) | Death at day 28 | 7 | 8 | 56 | 59 | 0.92 (0.33–2.53) | 8 mg/kg (up to 800 mg) at day1; an additional fixed dose of tcz, 400 mg on day 3 |

| 22 | Veiga | 08/05/20–17/06/20 | Brazil | Prospective | 129 | 44 (68) | 44 (69) | 57.4 ± 15.7* | 57.5 ± 13.5* | Death at day 28 | 14 | 6 | 51 | 58 | NA | A single intravenous infusion at 8 mg/kg |

| 22 | Veiga | 08/05/20–17/06/20 | Brazil | Prospective | 129 | 44 (68) | 44 (69) | 57.4 ± 15.7* | 57.5 ± 13.5* | Mechanical ventilation requirement at day 29 | 4 | 4 | 61 | 60 | NA | A single intravenous infusion at 8 mg/kg |

| 23 | Soin | 30/05/20–31/08/20 | India | Prospective | 180 | 76 (84%) | 76 (86%) | 56 (47–63) | 54 (43–63) | Death at day 28 | 11 | 15 | 80 | 73 | NA | A single dose between 4 mg/kg and 8 mg/kg plus an additional dose if required |

| 23 | Soin | 30/05/20–31/08/20 | India | Prospective | 180 | 76 (84%) | 76 (86%) | 56 (47–63) | 54 (43–63) | Incidence of mechanical ventilation at day 28 | 14 | 13 | 77 | 75 | NA | A single dose between 4 mg/kg and 8 mg/kg plus an additional dose if required |

| 24 | Albertini | 06/04/20–21/04/20 | France | Retrospective | 44 | 16 (73%) | 15 (68%) | 64 (41–80) | 65 (41–82) | Death at day 14 | 1 | 0 | 21 | 22 | NA | A fixed dose of 600 mg for patients <100 kg and 800 mg for those >100 kg |

| 24 | Albertini | 06/04/20–21/04/20 | France | Retrospective | 44 | 16 (73%) | 15(68%) | 64 (41–80) | 65 (41–82) | Mechanical ventilation requirement at day 14 | 2 | 6 | 20 | 16 | NA | A fixed dose of 600 mg for patients <100 kg and 800 mg for those >100 kg |

| 25 | Gokhale | 31/03/20–05/07/20 | India | Retrospective | 269 | 107 (70.9%) | 69 (58.5%) | 53 (44–60) | 55 (47–64) | Overall mortality | 79 | 74 | 72 | 44 | NA | A single intravenous infusion of 400mg |

HR hazard ratio, NA Not applicable, SOC Standard of care, *Age was described in mean ± standard deviation (when other studies used median and interquartile range)

Meta-analysis results

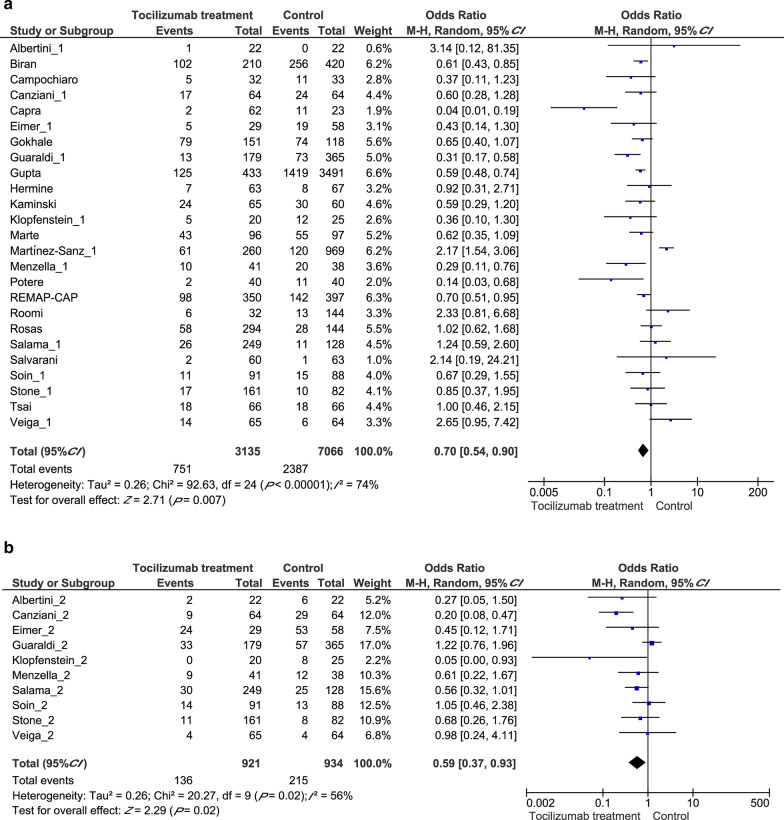

Tocilizumab’s overall effect on clinical outcomes

First, we performed analyses to evaluate tocilizumab’s effect on overall mortality and mechanical ventilation requirement. Our pooled analysis revealed a significant difference between the tocilizumab group (715/3135, 22.8%) and control group (2387/7066, 33.8%) in the random-effect model [Odds ratio (OR) = 0.70, 95% confidential interval (CI): 0.54–0.90, P = 0.007, Fig. 2a], suggesting efficacy of tocilizumab treatment for COVID-19. We also analyzed the studies focused on mechanical ventilation and tocilizumab treatment significantly reduced the requirement for mechanical ventilation (OR = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.37–0.93, P = 0.02, Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Forest plots displaying pooled odds ratios (ORs) for Tocilizumab treatment on different outcomes. a the pooled OR for Tocilizumab treatment on all clinical outcomes; b the pooled OR for Tocilizumab treatment on mechanical ventilation requirement outcome. CI: Confidence interval

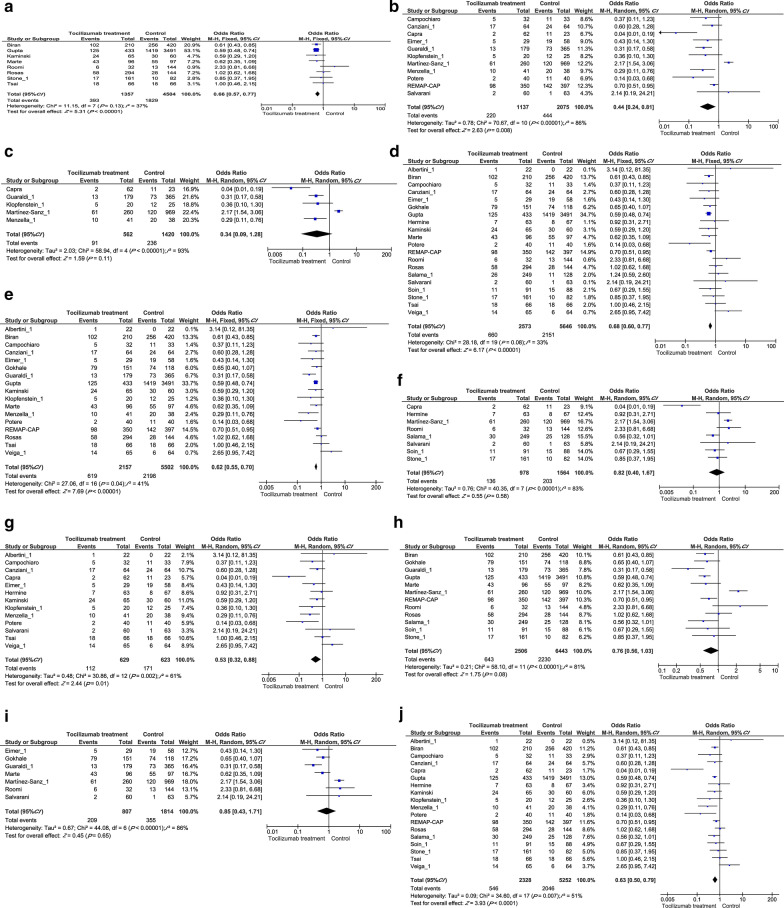

Subgroup analysis

We conducted various stratified analyses to identify possible confounders in tocilizumab treatment studies. First, we divided the manuscripts into different categories according to their traits including (1) study location: USA vs west Europe; (2) age differences: reported mean/median age older than 65 vs younger than 65; (3) disease severity: ICU patients vs general patients; (4) study sizes: patient group size of 150 or less vs 151 and more; (5) gender imbalance: studies with 10% more males in the tocilizumab treatment group than the control group vs 10% or less males.

In both USA and western Europe, tocilizumab treatment significantly reduced mortality (OR = 0.66, 95% CI: 0.57–0.77, P < 0.00001, Fig. 3a; and OR = 0.44, 95% CI: 0.24–0.81, P = 0.008, Fig. 3b), other regions are too little studies to make a subgroup. Tocilizumab treatment did not show efficacy among older subpopulations (OR = 0.34, 95% CI: 0.09–1.28, P = 0.11, Fig. 3c), but significantly benefited patients whose mean/median age is less than 65 years old (OR = 0.68, 95% CI: 0.60–0.71, P < 0.00001, Fig. 3d). Because we divided studies based on their reported median/mean age, results are based on characteristics of the whole group and not the individuals within. Our results also showed that tocilizumab treatment significantly improved outcome among severe or ICU-admitted COVID-19 patients (OR = 0.62, 95% CI: 0.55–0.70, P < 0.00001, Fig. 3e), but had no effects on general COVID-19 patients (OR = 0.82, 95% CI: 0.40–1.67, P = 0.58, Fig. 3f). Interestingly, tocilizumab treatment significantly improved outcomes in studies with 150 patients or less (OR = 0.53, 95% CI: 0.32–0.88, P = 0.01, Fig. 3g), but not in larger studies (OR = 0.76, 95% CI: 0.56–1.03, P = 0.08, Fig. 3h). Tocilizumab treatment did not correlate with improved clinical outcome in male dominated studies (OR = 0.85, 95% CI: 0.43–1.71, P = 0.65, Fig. 3i), but associates with improved outcomes in gender-balanced studies (OR = 0.63, 95% CI: 0.50–0.79, P < 0.0001, Fig. 3j), which suggests different responses to SARS-COV-2 between male and female patients.

Fig. 3.

Subgroup analysis of pooled OR for Tocilizumab treatment on COVID-19 prognosis. a USA patients; b West Europe patients; c patients with a median age ≥ 65; d patients with a median age < 65; e ICU patients f general patients g total patient number less than 150 h total patient number more than 150; i studies that had 10% more male in the treatment group than the control group j studies that has balance male percentage in treatment and control group. CI Confidence interval

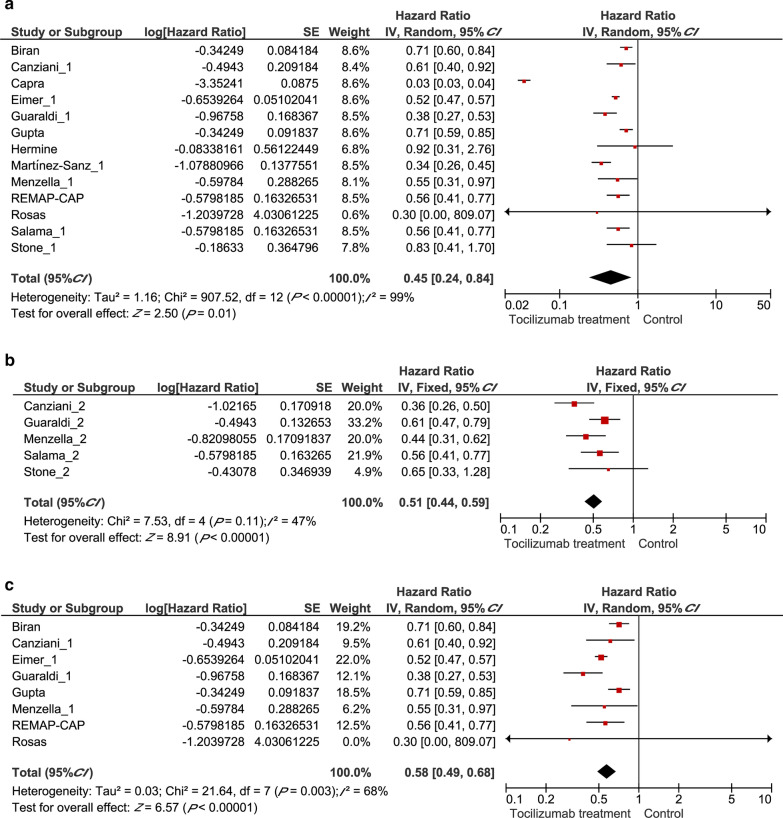

Hazzard ratio on clinical outcomes

To further evaluate the prognostic effects of tocilizumab treatment among COVID-19 patients, we extracted the multivariate HRs and their 95% CI in these studies to calculate a combined HR, demonstrating that patients with a tocilizumab treatment had better outcomes than patients receiving standard care (HR = 0.45, 95% CI: 0.24–0.81, P = 0.01, Fig. 4a). In terms of the secondary outcome, tocilizumab was associated with a lower probability of requiring invasive ventilation (HR = 0.51, 95% CI: 0.44–0.59, P < 0.00001, Fig. 4b). Among severe COVID-19 patients, the administration of tocilizumab correlates with a markedly better prognosis (HR = 0.58, 95% CI 0.49–0.68, P < 0.00001, Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Forest plots displaying pooled hazard ratios (HRs) for Tocilizumab treatment on different outcomes. a the pooled HR for Tocilizumab treatment on all clinical outcomes; b the pooled HR for Tocilizumab treatment on mechanical ventilation requirement outcome; c the pooled HR for Tocilizumab treatment on overall mortality from ICU patients. CI Confidence interval

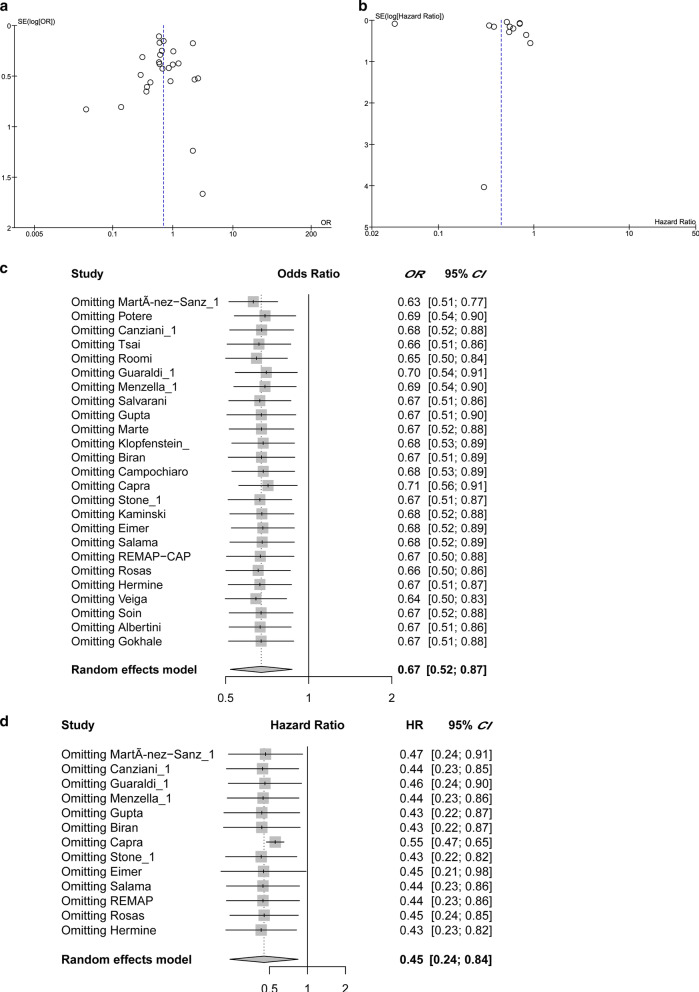

Meta-analysis quality control

Begg's funnel test was used to estimate all the existing publication bias of the literature in this meta-analysis. As shown in Fig. 5a, the shape of the funnel plots of all outcomes showed no evidence of asymmetry, with an Egger's test bias intercept at -0.41 (P = 0.58). For the hazard ratio analysis, Begg's funnel test does not show asymmetry (Fig. 5b), with an Egger’s test bias intercept of 0.4982 (P = 0.6184). The observed tocilizumab treatment effects on all outcomes (by OR) and prognosis (by HR) were not significantly affected by removing any one of the studies included, as is shown in Fig. 5c, d. In summary, there were no significant outliers in this meta-analysis.

Fig. 5.

Quality assessment. a The funnel plots of all outcome odds ratio analysis. b The funnel plot of pooled hazard ratio analysis. c The sensitivity analysis of OR studies by omitting one at a time. d The sensitivity analysis of all HR studies. CI Confidence interval, HR Hazard ratio, OR Odds Ratio

Discussion

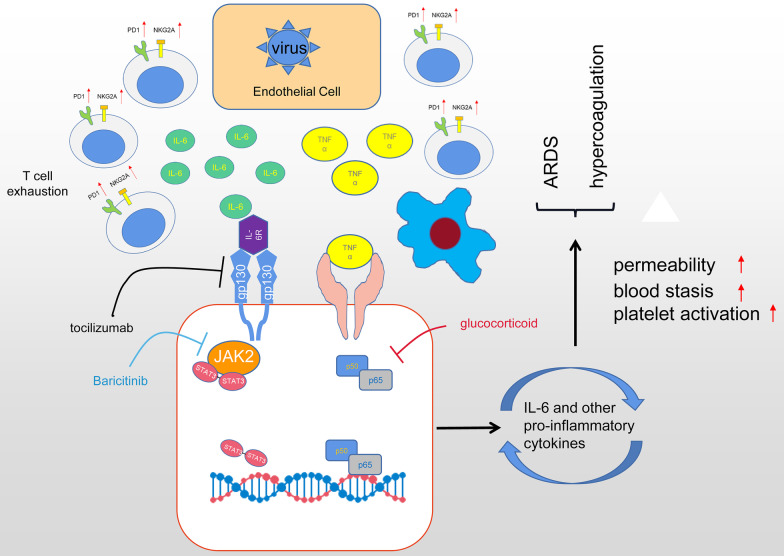

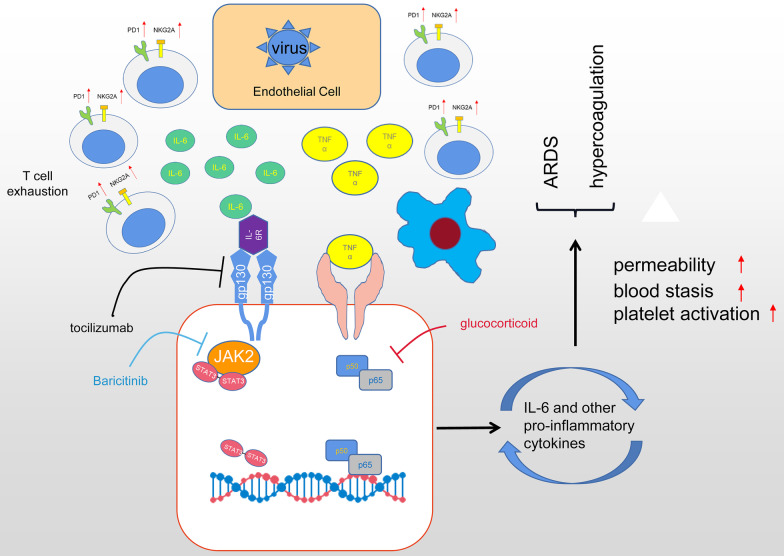

In 2020, the spreading of COVID-19 brought unprecedented healthcare and economy costs and substantial morbidity globally. Major causes of deaths in severe COVID-19 patients were ARDS and disseminated intravascular coagulation, which result from uncontrolled inflammatory processes after SARS-CoV-2 infection [3]. Interestingly, SARS-CoV-2 invades airway epithelial cells without triggering the secretion of type I and III interferon, the first line of defense to block early virus replication [38]. Instead, the infected airway epithelia produce IL-6 and other pro-inflammatory cytokines, attracting monocytes and cytotoxic T cells to the infection site to recognize and to destroy the infected cells [39]. Then, macrophages are summoned to engulf the apoptotic cells through phagocytosis. In healthy responses, SARS-CoV-2 infections are resolved through this process, the level of inflammatory cytokines recedes, and patients recover [40]. In severely affected COVID-19 patients, however, excessive secretion of IL-6 and other pro-inflammatory cytokines summon T cell aggregation and cause T cell functional exhaustion with increased expression of PD-1 and NKG2A [41]. This is confirmed by the commonly observed correlation of lymphopenia with elevated cytokine profiles in severe COVID-19 patients [42]. Furthermore, hyper-secreted IL-6 will activate the JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways in both immune and non-immune cells, inducing a massive and sustained production of NF-κB target genes, including IL-6 and other chemokines [43]. Such a positive feedback loop of IL-6 secretion further fuels hyperinflammation and increases vascular permeability leading to pulmonary edema and ARDS. Moreover, the cytokine storm also results in the disruption of vascular endothelium, blood stasis and the activation of coagulation, triggering a hypercoagulable status in COVID-19 patients [44]. It has been well-recognized that COVID-19-induced cytokine storm is a critical contributor to COVID-19 relevant mortality [40, 45]. Controlling the COVID-19-induced cytokine storm is important for improving severe COVID-19 patients' prognosis.

Although there are no approved therapies for the COVID-19-induced cytokine storm, various strategies targeting different stages of the cytokine storm have been proposed. Glucocorticoid has powerful anti-inflammatory properties and was widely used during the outbreaks of SARS and MERS, but clinical evidence for corticosteroid treatment of SARS-CoV-2-induced lung injuries remains controversial. A large-scale clinical trial showed that the use of dexamethasone resulted in lower 28-day mortality among those severe patients, but the authors also warned that high doses or wrong administration timing can be harmful as glucocorticoid delays viral clearance [46]. Another study from Wuhan showed that high-dose corticosteroid uses were associated with death in patients with severe COVID-19 [3].

Given the pivotal role of IL-6 in COVID-19 induced cytokine storm, it is attractive to target hyperinflammation during SARS-CoV-2 infection via the blockage of IL-6. Tocilizumab is a competitive inhibitor of both the membrane-bound and soluble IL-6 receptor, preventing downstream signal transduction of IL-6. Early reports of tocilizumab treatment in COVID-19 patients showed promising results, while the lack of control and small sample sizes dampened their reliability[24, 25]. To address this question, several multi-center cohort studies inspected the efficiencies of tocilizumab on several subpopulations of COVID-19 patients. Their findings revealed a correlation of early Tocilizumab administration with lower mortality rates among critically ill COVID-19 patients with a rapid disease trajectory[19]. More importantly, Tocilizumab demonstrated satisfactory safety in clinics because COVID-19 patients receiving Tocilizumab do not show higher incidences of adverse events, including secondary infections and hepatotoxicity [33].

Another possible approach of COVID-19-induced cytokine storm mitigation is to inhibit the JAK-STAT intracellular signaling pathway. As we mentioned before, the activation of JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways are important mediators of cytokine storm by receiving signals from proinflammatory signals, such as IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, IFN-γ, and GM-CSF, and producing more proinflammatory cytokines. Baricitinib, an orally administered selective inhibitor of JAK 1 and 2, was found effective in reducing recovery time among COVID-19 patients, especially in severe cases requiring high-flow oxygen or noninvasive ventilation [47]. Baricitinib is also suggested to reduce viral entry due to its inhibition of AP2-associated protein kinase 1[48], however, the concerns of increasing viral loads and thromboembolism risks limit its uses. Taken together, the suppression of COVID-19 induced cytokine storms is key to the effective treatment of severe COVID-19 patients and can be targeted with different strategies. We summarized the possible mechanisms and therapeutic strategies to address the COVID-19-induced cytokine storm in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 associated cytokine storm and targeted therapeutic approaches

In this study, we reported that the administration of tocilizumab to COVID-19 patients is associated with reduced mortality and shorter intubation time. However, the conclusion should be interpreted with caution since several randomized clinical trials fail to support it. There are some confounders that should contribute to the inconsistency. Most importantly, both the trials recruited general, but not severe, COVID-19 patients for study [19, 33]. According to our analysis, however, the association of tocilizumab with clinical benefits is even stronger among severe COVID-19 patients. The most recently published prospective randomized clinical trial backs our conclusion, suggesting that COVID-19 patients with moderate or severe disease were more likely to benefit from tocilizumab [33]. It is of great necessity to conduct more clinical trials to pinpoint the subgroups of COVID-19 patients that are most likely to benefit tocilizumab treatment. In addition, routes, dosing, and timing of tocilizumab administration also play important roles and need to be considered carefully. Currently, there are no standard regulations and doctors apply tocilizumab empirically or based on availability. Although the efficacy and safety of subcutaneous tocilizumab are comparable to intravenous tocilizumab in most clinical applications [49], intravenous tocilizumab is preferred over subcutaneous therapy to treat COVID-19-induced cytokine storm [20]. Currently, tocilizumab is administered either at fixed doses or dependent on bodyweight. Most of the patients received tocilizumab quickly after entering ICU, which presumably represents a hyperinflammatory prime. In addition, the lack of a reliable/useful/accurate biomarker for the COVID-19-induced cytokine storm dampens the efficiency of tocilizumab. Currently, serum IL-6 level, along with other inflammatory markers such as CRP, ferritin, are used in isolation or together to determine and predict the efficacy of tocilizumab in COVID-19 treatment. Further studies are warranted.

There are some advantages of this systematic review when compared to several published ones with the similar topic. Small-scale, unbalanced or non-peer-reviewed studies constitute the major sources of previous meta-analyses [12, 13]. The inclusion of recently published high impact large-scale studies enable us to provide more reliable and updated insights into tocilizumab uses in COVID-19 patients. Notably, to minimize the interferences of confounding factors, we conducted various subgroup analyses, such as severe patient only-, age stratified- and gender stratified- analyses. Our results demonstrated that severely ill COVID-19 patients can benefit more from tocilizumab treatment, providing evidence for further clinical trials and patient managements. We also evaluated the efficacy of tocilizumab uses on different outcomes, including mortality and the reduction in mechanical ventilation duration. There are some limitations in this study as dosing, timing and routes of tocilizumab administration vary among the included manuscripts. Furthermore, the definition of COVID-19 severity is inconsistent among the included manuscripts. Finally, the follow-up time in terms of mortality occurrence is not the same across all studies, which might result in immortal time bias to some degree.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis included 25 peer-reviewed publications with more than 10 201 individuals to analyze the correlation of tocilizumab with clinical outcomes among COVID-19 patients. Our study shows that tocilizumab treatment is associated with a lower risk of mortality and mechanical ventilation requirement among COVID-19 patients, especially among the critically ill. A combined HR also demonstrated that COVID-19 patients receiving tocilizumab treatment had better prognosis than those receiving standard care. Our stratified sub-group analysis revealed that disease severity, age, and sex play important roles in determining the efficacy of tocilizumab. Therefore, our results provide substantial evidence that tocilizumab benefits critically ill COVID-19 patients.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Quality assessment of included studies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- CI

Confidence interval

- HR

Hazard ratio

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- IL-2

Interleukin-2

- IL-6

InterleukinInterleukin-6

- IL-10

InterleukinInterleukin-10

- Jak1

Janus kinase 1

- Jak2

Janus kinase 2

- MERS

Middle east respiratory syndrome

- NKG2A

Natural killer cell receptor group 2 member A

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor-κB

- OR

Odds Ratio

- PD-1

Programmed-cell death protein 1

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses

- SARS

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

- SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- STATs

Signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-α

Authors' contributions

Qiu Wei, Hua Lin and Rongguo Wei did literature search, quality assessment and data extraction. Donghua Zou and Jinru Wei did data analysis and data visualization. All authors wrote and revised the manuscript together. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Project of Qingxiu District of Nanning Scientific Research and Technology Development Plan (2019038 and 2020059), the Project of Nanning Scientific Research and Technology Development Plan (20183040-4), Guangxi medical and health key discipline construction project (To department of Emergency Medicine and Clinical Medical Laboratory Center), and the High-Level Medical Expert Training Program of Guangxi “139” Plan Funding (G201903049).

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusion of this article is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Footnotes

Qiu Wei, Hua Lin and Rong-Guo Wei contributed equally to this work

Contributor Information

Dong-Hua Zou, Email: zoudonghua@gxmu.edu.cn.

Jin-Ru Wei, Email: weijinru@stu.gxmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395:470–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard [Internet]. https://covid19.who.int. Accessed 1 Jan 2021.

- 3.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manson JJ, Crooks C, Naja M, Ledlie A, Goulden B, Liddle T, et al. COVID-19-associated hyperinflammation and escalation of patient care: a retrospective longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2:e594–602. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30275-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore JB, June CH. Cytokine release syndrome in severe COVID-19. Science. 2020;368:473–474. doi: 10.1126/science.abb8925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Del Valle DM, Kim-Schulze S, Huang H-H, Beckmann ND, Nirenberg S, Wang B, et al. An inflammatory cytokine signature predicts COVID-19 severity and survival. Nat Med. 2020;26:1636–1643. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1051-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J, Hao Y, Ou W, Ming F, Liang G, Qian Y, et al. Serum interleukin-6 is an indicator for severity in 901 patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: a cohort study. J Trans Med. 2020;18:406. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02571-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martínez-Sanz J, Muriel A, Ron R, Herrera S, Pérez-Molina JA, Moreno S, et al. Effects of tocilizumab on mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a multicentre cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(2):238–243. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kewan T, Covut F, Al-Jaghbeer MJ, Rose L, Gopalakrishna KV, Akbik B. Tocilizumab for treatment of patients with severe COVID–19: a retrospective cohort study. EclinicalMedicine. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsai A, Diawara O, Nahass RG, Brunetti L. Impact of tocilizumab administration on mortality in severe COVID-19. Sci Rep. 2020;10:19131. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76187-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Efficacy of tocilizumab in patients hospitalized with Covid-19 | NEJM. 2021. 10.1056/NEJMoa2028836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Lan S-H, Lai C-C, Huang H-T, Chang S-P, Lu L-C, Hsueh P-R. Tocilizumab for severe COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;56:106103. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kotak S, Khatri M, Malik M, Malik M, Hassan W, Amjad A, et al. Use of tocilizumab in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of current evidence. Cureus. 2020;12:e10869. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu L, He F, Wang H, Gao B, Wu H, Zhao S. A high plasma D-dimer level predicts poor prognosis in gynecological tumors in East Asia area: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:51551–51558. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roomi S, Ullah W, Ahmed F, Farooq S, Sadiq U, Chohan A, et al. Efficacy of hydroxychloroquine and tocilizumab in patients with COVID-19: single-center retrospective chart review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e21758. doi: 10.2196/21758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta S, Wang W, Hayek SS, Chan L, Mathews KS, Melamed ML, et al. Association between early treatment with tocilizumab and mortality among critically Ill patients with COVID-19. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.6252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rojas-Marte G, Khalid M, Mukhtar O, Hashmi AT, Waheed MA, Ehrlich S, et al. Outcomes in patients with severe COVID-19 disease treated with tocilizumab: a case-controlled study. QJM. 2020;113:546–550. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biran N, Ip A, Ahn J, Go RC, Wang S, Mathura S, et al. Tocilizumab among patients with COVID-19 in the intensive care unit: a multicentre observational study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2:e603–e612. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30277-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stone JH, Frigault MJ, Serling-Boyd NJ, Fernandes AD, Harvey L, Foulkes AS, et al. Efficacy of tocilizumab in patients hospitalized with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2333–2344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2028836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaminski MA, Sunny S, Balabayova K, Kaur A, Gupta A, Abdallah M, et al. Tocilizumab therapy for COVID-19: a comparison of subcutaneous and intravenous therapies. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;101:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eimer J, Vesterbacka J, Svensson A-K, Stojanovic B, Wagrell C, Sönnerborg A, et al. Tocilizumab shortens time on mechanical ventilation and length of hospital stay in patients with severe COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. J Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1111/joim.13162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Potere N, Nisio MD, Cibelli D, Scurti R, Frattari A, Porreca E, et al. Interleukin-6 receptor blockade with subcutaneous tocilizumab in severe COVID-19 pneumonia and hyperinflammation: a case–control study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Canziani LM, Trovati S, Brunetta E, Testa A, De Santis M, Bombardieri E, et al. Interleukin-6 receptor blocking with intravenous tocilizumab in COVID-19 severe acute respiratory distress syndrome: a retrospective case-control survival analysis of 128 patients. J Autoimmun. 2020;114:102511. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guaraldi G, Meschiari M, Cozzi-Lepri A, Milic J, Tonelli R, Menozzi M, et al. Tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2:e474–e484. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30173-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menzella F, Fontana M, Salvarani C, Massari M, Ruggiero P, Scelfo C, et al. Efficacy of tocilizumab in patients with COVID-19 ARDS undergoing noninvasive ventilation. Crit Care. 2020;24:589. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03306-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salvarani C, Dolci G, Massari M, Merlo DF, Cavuto S, Savoldi L, et al. Effect of tocilizumab vs standard care on clinical worsening in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.6615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klopfenstein T, Zayet S, Lohse A, Balblanc J-C, Badie J, Royer P-Y, et al. Tocilizumab therapy reduced intensive care unit admissions and/or mortality in COVID-19 patients. Med Mal Infect. 2020;50:397–400. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campochiaro C, Della-Torre E, Cavalli G, De Luca G, Ripa M, Boffini N, et al. Efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in severe COVID-19 patients: a single-centre retrospective cohort study. Eur J Intern Med. 2020;76:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Capra R, De Rossi N, Mattioli F, Romanelli G, Scarpazza C, Sormani MP, et al. Impact of low dose tocilizumab on mortality rate in patients with COVID-19 related pneumonia. Eur J Intern Med. 2020;76:31–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hermine O, Mariette X, Tharaux P-L, Resche-Rigon M, Porcher R, Ravaud P, et al. Effect of tocilizumab vs usual care in adults hospitalized with COVID-19 and moderate or severe pneumonia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:32–40. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.6820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Albertini L, Soletchnik M, Razurel A, Cohen J, Bidegain F, Fauvelle F, et al. Observational study on off-label use of tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID-19. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2021;28:22–27. doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2020-002414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Interleukin-6 Receptor Antagonists in Critically Ill Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021. 10.1056/NEJMoa2100433 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Salama C, Han J, Yau L, Reiss WG, Kramer B, Neidhart JD, et al. Tocilizumab in patients hospitalized with Covid-19 pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2021 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2030340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosas IO, Bräu N, Waters M, Go RC, Hunter BD, Bhagani S, et al. Tocilizumab in hospitalized patients with severe Covid-19 pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2021 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2028700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Veiga VC, Prats JAGG, Farias DLC, Rosa RG, Dourado LK, Zampieri FG, et al. Effect of tocilizumab on clinical outcomes at 15 days in patients with severe or critical coronavirus disease 2019: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2021;372:n84. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soin AS, Kumar K, Choudhary NS, Sharma P, Mehta Y, Kataria S, et al. Tocilizumab plus standard care versus standard care in patients in India with moderate to severe COVID-19-associated cytokine release syndrome (COVINTOC): an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00081-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gokhale Y, Mehta R, Kulkarni U, Karnik N, Gokhale S, Sundar U, et al. Tocilizumab improves survival in severe COVID-19 pneumonia with persistent hypoxia: a retrospective cohort study with follow-up from Mumbai. India BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:241. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-05912-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ribero MS, Jouvenet N, Dreux M, Nisole S. Interplay between SARS-CoV-2 and the type I interferon response. PLOS Pathog. 2020;16:e1008737. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vanderheiden A, Ralfs P, Chirkova T, Upadhyay AA, Zimmerman MG, Bedoya S, et al. Type I and Type III interferons restrict SARS-CoV-2 infection of human airway epithelial cultures. J Virol. 2020;94:382–727. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00985-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan. China Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng M, Gao Y, Wang G, Song G, Liu S, Sun D, et al. Functional exhaustion of antiviral lymphocytes in COVID-19 patients. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17:533–535. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0402-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu J, Li S, Liu J, Liang B, Wang X, Wang H, et al. Longitudinal characteristics of lymphocyte responses and cytokine profiles in the peripheral blood of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. EBioMedicine. 2020;55:102763. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hojyo S, Uchida M, Tanaka K, Hasebe R, Tanaka Y, Murakami M, et al. How COVID-19 induces cytokine storm with high mortality. Inflamm Regen. 2020;40:37. doi: 10.1186/s41232-020-00146-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jose RJ, Manuel A. COVID-19 cytokine storm: the interplay between inflammation and coagulation. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:e46–e47. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30216-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, Jiang L, Song J. Correction to: clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan. China Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1294–1297. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06028-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, Mafham M, Bell JL, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with covid-19—preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kalil AC, Patterson TF, Mehta AK, Tomashek KM, Wolfe CR, Ghazaryan V, et al. Baricitinib plus remdesivir for hospitalized adults with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2031994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Richardson P, Griffin I, Tucker C, Smith D, Oechsle O, Phelan A, et al. Baricitinib as potential treatment for 2019-nCoV acute respiratory disease. Lancet. 2020;395:e30–e31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30304-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burmester GR, Rubbert-Roth A, Cantagrel A, Hall S, Leszczynski P, Feldman D, et al. Efficacy and safety of subcutaneous tocilizumab versus intravenous tocilizumab in combination with traditional DMARDs in patients with RA at week 97 (SUMMACTA) Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:68–74. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Quality assessment of included studies.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the conclusion of this article is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.