Abstract

Objective

To evaluate potential MRI-defined effect modifiers of amoxicillin treatment in patients with chronic low back pain and type 1 or 2 Modic changes (MCs) at the level of a previous lumbar disc herniation (index level).

Methods

In a prospective trial (AIM), 180 patients (25–64 years; mean age 45; 105 women) were randomised to receive amoxicillin or placebo for 3 months. Primary outcome was the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) score (0–24 scale) at 1 year. Mean RMDQ score difference between the groups at 1 year defined the treatment effect; 4 RMDQ points defined the minimal clinically important effect. Predefined baseline MRI features of MCs at the index level(s) were investigated as potential effect modifiers. The predefined primary hypothesis was a better effect of amoxicillin when short tau inversion recovery (STIR) shows more MC-related high signal. To evaluate this hypothesis, we pre-constructed a composite variable with three categories (STIR1/2/3). STIR3 implied MC-related STIR signal increases with volume ≥ 25% and height > 50% of vertebral body and maximum intensity increase ≥ 25% and presence on both sides of the disc. As pre-planned, interaction with treatment was analysed using ANCOVA in the per protocol population (n = 155).

Results

The STIR3 composite group (n = 41) and STIR signal volume ≥ 25% alone (n = 45) modified the treatment effect of amoxicillin. As hypothesised, STIR3 patients reported the largest effect (− 5.1 RMDQ points; 95% CI − 8.2 to − 1.9; p for interaction = 0.008).

Conclusions

Predefined subgroups with abundant MC-related index-level oedema on STIR modified the effect of amoxicillin. This finding needs replication and further support.

Key Points

• In the primary analysis of the AIM trial, the effect of amoxicillin in patients with chronic low back pain and type 1 or 2 MCs did not reach the predefined cut-off for clinical importance.

• In the present MRI subgroup analysis of AIM, predefined subgroups with abundant MC-related oedema on STIR reported an effect of amoxicillin.

• This finding requires replication and further support.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00330-020-07542-w.

Keywords: Magnetic resonance imaging, Spine, Low back pain, Amoxicillin, Prospective studies

Introduction

Modic changes (MCs) are magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings of vertebral bone marrow changes extending from the endplate. MCs are defined as type 1 (oedema type), 2 (fatty type), and 3 (sclerotic type) based on their intensity on T1- and T2-weighted MRI [1, 2]. However, the MC intensity and type depend on MRI scanning parameters and magnetic field strength [3, 4], and different MC types may represent stages of a common biological process [5]. This process may involve inflammation, fibrosis, high bone turnover, fatty infiltration, and sclerosis [1, 5, 6]. MCs were related to low back pain (LBP) in some studies but not in others [7–9]. The evidence for an association between MCs and LBP is stronger for type 1 than for type 2 or 3 MCs [10–15]. Proposed explanations for MCs include endplate damage, autoimmunity, and occult discitis [5]. Vertebral bone oedema resembling type 1 MCs is a common MRI finding in spondylodiscitis [16], and one theory is that MCs develop adjacent to a low-grade discitis region caused by haematogenic spread of Cutibacterium acnes bacteria to a previously disrupted, neo-vascularised lumbar disc [17, 18].

A previous trial reported a substantial effect of antibiotic treatment for chronic LBP with type 1 MCs on 0.2-T MRI [19]. Some of these MCs might have appeared as type 2 on 1.5-T MRI [4]. The recent AIM (Antibiotics In Modic changes) trial applied 1.5-T MRI [20] and reported a small but not clinically important effect of amoxicillin in chronic LBP patients with type 1 MCs (− 2.3 points on the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ)) and no effect for type 2 MCs (− 0.1 RMDQ points) [21]. Thus, the type 1 (oedema type) group tended to have a larger effect. More bone marrow oedema may be associated with worse pain and disability [22–24] and might indicate more severe disease with a larger potential for improvement. Therefore, we hypothesised a larger effect of amoxicillin in subgroups with more versus less MC-related oedema. It is relevant to assess subgroup effects across both MC types because both can contain inflammatory changes [25] and oedema [26].

Short tau inversion recovery (STIR) series are ideal for highlighting oedema. STIR suppresses a high signal from fat and often shows oedema in MCs classified as type 2 on T1/T2 series without fat suppression [26]. Although STIR is more sensitive to bone marrow oedema than standard T1/T2 series [26, 27], STIR can likewise not separate infectious from non-infectious causes [28, 29]. This subgroup study of the AIM trial included both STIR and standard fast spin echo T1/T2 sequences. We aimed to evaluate potential MRI-defined effect modifiers of amoxicillin treatment in patients with chronic LBP and type 1 or 2 MCs at the level of a previous lumbar disc herniation.

Materials and methods

The AIM trial included 180 patients from six hospital outpatient clinics in Norway from June 2015 to September 2017 [20, 21]. All the eligibility criteria are detailed in the Appendix, Table A1. The inclusion criteria were age 18–65 years, LBP for more than 6 months with a mean intensity of at least 5 on three 0–10 numerical rating scales, lumbar disc herniation on MRI in the preceding 2 years, and type 1 or type 2 MCs (with height ≥ 10% of the vertebral height and diameter > 5 mm) at the previously herniated disc level. Trial flow chart, trial methods, and baseline characteristics are published [21]. The trial, this study, and statistical analysis plans are registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT02323412).

Randomisation, treatment, and outcome measures

Patients were randomised to receive oral amoxicillin 750 mg or placebo (maize starch) three times daily for 3 months. The amoxicillin and placebo tablets had identical encapsulation, containers, and labelling. A third-party statistician used Stata 13 (StataCorp) to create randomisation lists. Allocation was stratified by prior disc surgery (yes/no) and MC type (type 1 (n = 118) or type 2 (n = 62) only) at the previously herniated disc level(s) with a 1:1:1:1 allocation and random block sizes of four and six [21]. The allocation sequence was concealed and centrally administered. Care providers gave patients a prescription with a computer-generated allocation number to be used at dedicated pharmacies. All care providers, research staff, statisticians, and patients were blinded to treatment allocation during data collection.

The primary endpoint was the RMDQ score (0–24 scale) at 1 year [30, 31]. The minimal clinically important difference in mean RMDQ score at 1 year between treatment groups (treatment effect) was predefined as 4 [20, 21]. The outcome at the end of the treatment period (3 months) was not primary because long-term improvement is desirable and the antibiotic group in the prior trial improved by 4.5 RMDQ points (0–23 scale) from the end of the treatment period to 1 year [19]. The Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) 2.0 (0–100 scale) [32] and LBP intensity (0–10 numeric rating scale) were secondary outcomes [21].

MRI assessment

Baseline MRI of the lumbar spine was performed at six centres using identical protocols and the same type of 1.5-T scanner with the same software version (Magnetom Avanto B19; Siemens). This MRI included sagittal T1- and T2-weighted fast spin echo (‘T1/T2’) and sagittal STIR images. The integrated spine array coil was used, but no surface coils. Echo time (ms)/repetition time (ms) was 11/575 for T1, 87/3700 for T2, and 70/5530 for STIR. Echo train length was 5 for T1, 17 for T2, and 20 for STIR. Matrix was 384 × 269 for T1/T2 and 320 × 224 for STIR. The inversion time for STIR was 160 ms. Slice thickness/spacing was 4 mm/0.4 mm and field of view was 300 mm × 300 mm for all three sequences. Other MRI parameters were also identical between centres [33].

Three radiologists (A.E., N.V., and P.M.K.) who were blinded to clinical outcomes and treatment allocation independently rated MRI findings [33]. All had > 10 years of experience in musculoskeletal MRI. The same three radiologists interpreted the MRIs from all study centres. On T1/T2, they rated primary (most extensive) and secondary MC types as type 1 (hypointense on T1, hyperintense on T2), type 2 (hyperintense on T1, iso- or hyperintense on T2), and type 3 (hypointense on T1 and T2) [33]. They evaluated the largest height and volume of MCs on T1/T2 and the largest height, volume and intensity of any MC-related STIR signal increase (Table 1), defined as a visible increase compared with normal vertebral bone marrow, located in or abutting a region with MC on T1/T2 or located and shaped as an MC [33].

Table 1.

Predefined MRI variables at index level(s) with type 1 or 2 MCs and prior disc herniation

| Description | Analysed subgroups | |

|---|---|---|

| STIR signal extent and intensity | ||

| STIR volume | Largest volume of high STIR signal in % of vertebral body marrow volume, visually estimated (not measured), and scored as 0, 1 (< 10%), 2 (< 25%), 3 (25–50%), or 4 (> 50%) | Scores 0–1, 2, and 3–4 |

| STIR height | Maximum height of region with high STIR signal, measured and recalculated into a percentage of vertebral body marrow height | Analysed as a continuous variable and dichotomised into ≤ 50% and > 50% |

| STIR intensity | Maximum intensity of the high STIR signal, measured as a percentage on a scale from normal vertebral body marrow intensity (0%) to cerebrospinal fluid intensity (100%) | < 25%, 25–40%, and > 40%a |

| STIR sup/inf | Presence of high STIR signal both superior (sup) and inferior (inf) to index disc (yes/no) | Yes and no |

| STIR composite | Categorised as STIR3 (volume ≥ 25% AND height > 50% AND intensity ≥ 25% AND yes for sup/inf), STIR2 (not STIR3 or STIR1) and STIR1 (volume < 25% AND intensity < 25%) | STIR1, STIR2, and STIR3 |

| MC type and extent on T1/T2 | ||

| MC type 1 degree | Categorised as type 1 major (primary type 1 both superior and inferior to disc), type 1 minor (primary or secondary type 1, but not type 1 major), and type 2 only (not type 1) | Type 2 only, type 1 minor, and type 1 major |

| MC volume | Largest volume of MC (including all MC types) in % of vertebral body marrow volume, visually estimated, and scored as 0, 1 (< 10%), 2 (< 25%), 3 (25–50%), or 4 (> 50%) | Scores 1, 2, and 3–4 (not score 0; conclusive MC volume cannot be 0 at an index level) |

| MC height | Maximum MC height (including all MC types), measured and recalculated as a percentage of vertebral body marrow height | Analysed as a continuous variable and dichotomised into ≤ 50% and > 50% |

| MC composite | Categorised as 1++ (type 1 major AND volume ≥ 10%—OR—primary type 1 AND volume ≥ 25% AND height ≥ 50% AND yes for sup/inf), 1+ (primary or secondary type 1 but not type 1++) and type 2 only | Type 2 only, 1+, and 1++ |

MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MCs, Modic changes; STIR, short tau inversion recovery; T1/T2, T1- and T2-weighted fast spin echo images

aSTIR intensity < 25% included MCs with no conclusive STIR signal increase (or decreased STIR signal) and thus no conclusive measured STIR intensity values. These values had likely been < 25% if measured, since the STIR intensity was < 20% for > 90% of intensity measurements reported by only one radiologist (as the other radiologists found no visual signal increase and therefore did not measure STIR intensity). To enhance clinical credibility, images were reviewed to ensure that intensity ≥ 25% implied visually convincing hyper-intensity

We based the conclusive MRI findings on the radiologists’ majority rating or mean value of measurements made by two of them (A.E. and P.M.K. if all three agreed there was a lesion to measure). The inter-rater reliability of the MRI evaluations was previously reported [33]. Fleiss’ kappa values [34] for overall inter-rater agreement (mean values across four endplates L4-S1) were 0.88/0.81 for presence of any MCs/type 1 MCs, 0.64/0.69 for MC height/volume, 0.86 for presence of a STIR signal increase, and 0.51/0.56 (0.40/0.40 at L5/S1 inferior to disc) for STIR signal height/volume. For maximum MC-related STIR signal intensity on a 0–100% scale (0% = normal vertebral body; 100% = cerebrospinal fluid), largest mean of differences and widest 95% limits of agreement were 0.9% and ± 7.6%, respectively.

Predefined hypotheses and potential effect modifiers

In the AIM trial protocol, we hypothesised a better effect of amoxicillin when:

STIR shows more MC-related high signal (primary hypothesis)

MCs contain more type 1 than type 2 or are larger (explorative hypothesis)

The nine variables described in Table 1 were predefined as potential effect modifiers in the statistical analysis plan. All concerned MCs at the index level(s) with prior disc herniation because this level was hypothesised to contain low-grade discitis that was the target for treatment. One composite and four underlying variables concerned STIR signal extent and intensity. The STIR composite variable had three categories (STIR1/2/3) and was used to assess the primary hypothesis. STIR3 implied MC-related STIR signal increase with volume ≥ 25% and height > 50% of the vertebral body, maximum intensity increase ≥ 25%, and presence on both sides of the disc. One composite and three underlying variables concerned MC extent and type 1 degree on T1/T2. We constructed each composite variable by clinically plausible grouping of the underlying variables [35]. We did so before analysing the effect of any MRI variable on the outcome but were not blinded to the distribution of the variables in our sample.

Analyses

The baseline properties of the randomised groups were characterised using descriptive methods.

All pre-planned analyses are described in Table 2. Each effect modifier was analysed using ANCOVA with the outcome (RMDQ, ODI, or LBP intensity) at 1 year as the dependent variable and the randomisation group, effect modifier, and their interaction as independent variables adjusted for the baseline values of the outcome. Additionally, we adjusted for age and prior disc surgery because contamination during surgery is a potential cause of discitis. Supporting the use of ANCOVA, Levene’s test indicated homogeneity of variances, and QQ plots indicated normally distributed residuals and outcome variables without extreme outliers. If one or both composite MRI variables modified the treatment effect, we would include both in the same model to assess their independence [36]. Post hoc analyses, marked as such throughout the manuscript, are also described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Analyses—pre-planned and post hoc

| Analysed population | |

|---|---|

| Pre-planned analyses | |

| ANCOVAa—dependent variable: RMDQ score at 1 year; independent variables: baseline RMDQ score, the potential effect modifier, treatment group, their interaction term (effect modifiera treatment), age, former disc herniation surgery | PP and ITT |

| ANCOVAa—as above with ODI score replacing RMDQ score | PP and ITT |

| ANCOVAa—as above with LBP intensity score replacing RMDQ score | PP and ITT |

| ANCOVAa—to assess the independency of any effect modification for STIR composite and/or MC composite; dependent variable: RMDQ score at 1 year; independent variables: baseline RMDQ score, STIR composite, MC composite, age, treatment, STIR composite*treatment, MC composite*treatment, age*treatment, former disc herniation surgery | PP |

| Post hoc analyses—to evaluate STIR3 results | |

| Comparison of treatment groups—baseline factors, concomitant treatment; no statistical testing | STIR3 group |

| Responder analyses—number needed to treat to achieve > 30%, > 50%, and > 75% reduced RMDQ score from baseline to 1 year (for those with complete data) | STIR3 group with data |

| Distribution of responders—number and proportions of patients with > 30%, > 50%, and > 75% reduced RMDQ score at 1 year (those with complete data) by treatment group and STIR group | All with data |

| Linear mixed-effects models—to assess treatment effect over time; using Akaike’s information criterion to decide which covariance matrix to apply; dependent variable: RMDQ (5 time points), ODI (3 time points), or LBP intensity (17 time points); independent variables: time, treatment, time*treatment, age, prior disc herniation surgery | PP STIR3 group |

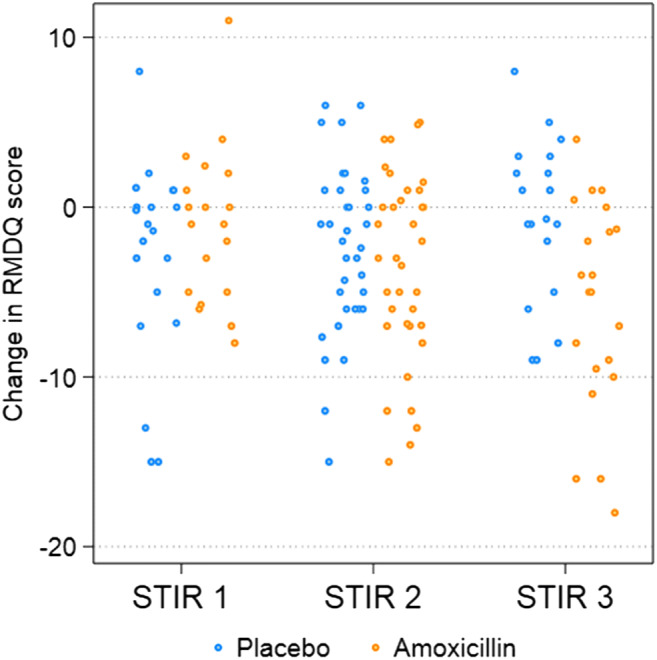

| Scatterplot of change in RMDQ score—to visualise change in RMDQ score from baseline to 1 year in each treatment group for STIR1, STIR2, and STIR3 patients (those with complete data) | PP with data |

| Bangs blinding index—for each treatment group based on their response at 1 year to ‘Which study medicine do you think you received?’ (antibiotics/placebo/unsure); range: − 1 (all report incorrect treatment) to 1 (all report the correct treatment); 0 = random reporting of treatment | STIR3 group |

PP, per protocol; ITT, intention to treat; RMDQ, Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire; ODI, Oswestry Disability Index; LBP, low back pain; STIR, short tau inversion recovery; MC, Modic change

aMissing values of RMDQ, ODI, or LBP intensity were substituted with imputed values from the multiple imputations performed in the trial. This multiple imputation model used 50 imputations, predictive mean matching, and the following predictors: age, leg pain, comorbidity, fear avoidance, emotional distress, physical workload, former surgery for disc herniation, study centre, MC type group, and treatment group

The primary analyses were performed on the predefined per protocol (PP) population described in the Appendix, page 2. The intention to treat (ITT) population was used for supportive analyses. Missing outcome values were imputed using multiple imputation (details in footnote, Table 2).

We used a Bonferroni-corrected alpha of 0.05/6 (0.008) when testing the primary hypothesis (ranked as hypothesis six in the trial protocol) [20]. Otherwise, an alpha of 0.05 was applied to minimise type 2 errors [37]. Analyses were performed using Stata 16 (StataCorp), and figures were made using MATLAB 9.5 (MathWorks) or Stata 16.

Power calculation

The AIM trial was designed with 90% power in each MC type group [20]; 80% power in the total sample would have required 50 patients or 200 patients in a subgroup study with two equally large subgroups [38]. In this study with three subgroup categories, 80% power would have required > 200 patients. Adding covariates in the analyses improved the power [39], but our sample was still small.

Results

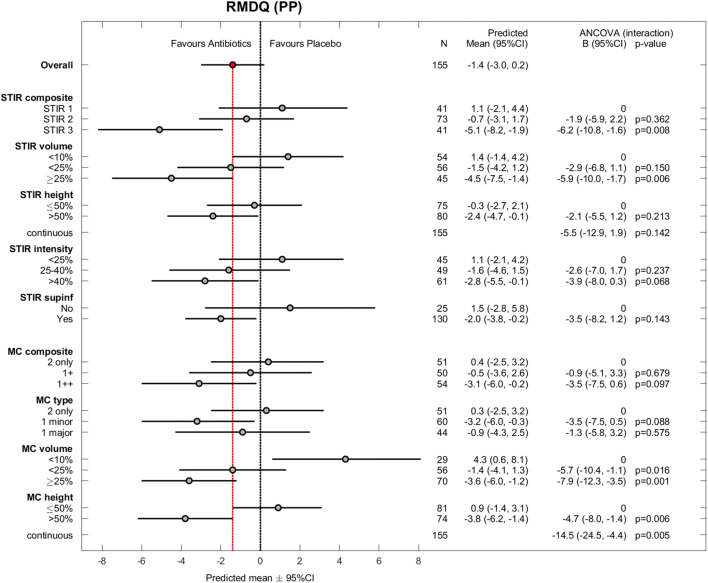

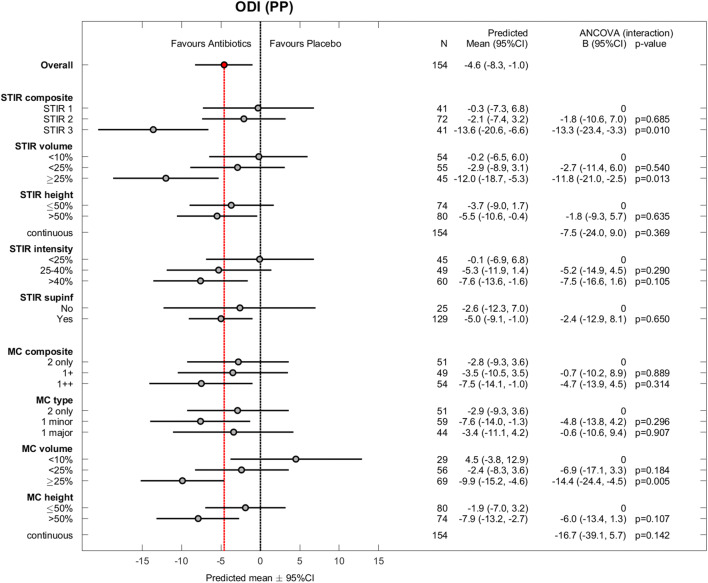

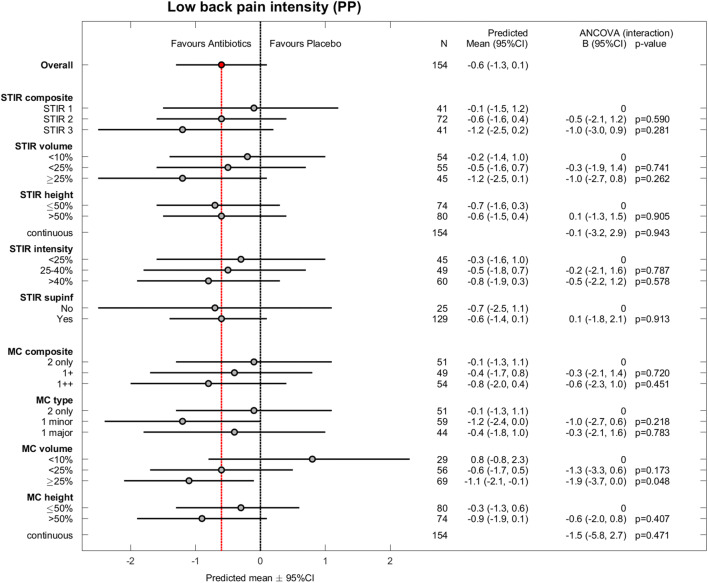

The 180 patients were aged 25–64 years (mean age 45 years; standard deviation 9 years); 105 (58%) patients were women. Table 3 shows baseline MRI findings by treatment group. Of 360 baseline and 1-year outcome values, 13 were missing for RMDQ, 14 for ODI, and 13 for LBP intensity. The results for the effect modifiers were similar in PP analyses (n = 155) (Figs. 1, 2, and 3) and ITT analyses (n = 180) (Appendix, Figs. A1–A3).

Table 3.

Baseline index level MRI findings by treatment group in the total sample (N = 180)

| Amoxicillin group (N = 89) | Placebo group (N = 91) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | % | n | % |

| STIR composite | ||||

| STIR1 | 23 | 25.8 | 25 | 27.5 |

| STIR2 | 42 | 47.2 | 45 | 49.5 |

| STIR3 | 24 | 27.0 | 21 | 23.1 |

| STIR volume—maximum score (% of vertebral body marrow volume; visually estimated) | ||||

| 0 (0%) | 11 | 12.4 | 5 | 5.5 |

| 1 (< 10%) | 21 | 23.6 | 27 | 29.7 |

| 2 (< 25%) | 31 | 34.8 | 36 | 39.6 |

| 3 (25–50%) | 21 | 23.6 | 18 | 19.8 |

| 4 (> 50%) | 5 | 5.6 | 5 | 5.5 |

| STIR height—% of vertebral body marrow height | ||||

| Median (interquartile range) | 51 (32–63) | 51 (38–62) | ||

| < 25 | 15 | 16.9 | 11 | 12.1 |

| 25–50 | 28 | 31.5 | 34 | 37.4 |

| > 50 | 46 | 51.7 | 46 | 50.5 |

| STIR intensity—% increase from normal vertebral body intensity (0%) to CSF intensity (100%) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 39 (14) | 35 (14) | ||

| < 25 | 25 | 28.1 | 27 | 29.7 |

| 25–40 | 26 | 29.2 | 31 | 34.1 |

| > 40 | 38 | 42.7 | 33 | 36.3 |

| STIR sup/inf—STIR signal increase both superior and inferior to disc | ||||

| Yes | 72 | 80.9 | 78 | 85.7 |

| No | 17 | 19.1 | 13 | 14.3 |

| MC composite | ||||

| Type 2 only | 31 | 34.8 | 31 | 34.1 |

| 1+ | 19 | 21.3 | 36 | 39.6 |

| 1++ | 39 | 43.8 | 24 | 26.4 |

| MC type I degree—categories | ||||

| Type 2 only | 31 | 34.8 | 31 | 34.1 |

| Type 1 minor | 24 | 27.0 | 43 | 47.3 |

| Type 1 major | 34 | 38.2 | 17 | 18.7 |

| MC volume—maximum score (% of vertebral body marrow volume; cannot be 0%) | ||||

| 1 (< 10%) | 17 | 19.1 | 15 | 16.5 |

| 2 (< 25%) | 33 | 37.1 | 35 | 38.5 |

| 3 (25–50%) | 30 | 33.7 | 29 | 31.9 |

| 4 (> 50%) | 9 | 10.1 | 12 | 13.2 |

| MC height—% of vertebral body marrow height | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 51 (16) | 49 (16) | ||

| < 25 | 5 | 5.6 | 6 | 6.6 |

| 25–50 | 39 | 43.8 | 45 | 49.5 |

| > 50 | 45 | 50.6 | 40 | 44.0 |

| Index level(s) with MC and previous disc herniation | ||||

| L2/L3 | 2 | 2.2 | 2 | 2.2 |

| L3/L4 | 7 | 7.9 | 5 | 5.5 |

| L4/L5 | 48 | 53.9 | 29 | 31.9 |

| L5/S1 | 58 | 65.2 | 74 | 81.3 |

MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; STIR, short tau inversion recovery; SD, standard deviation; MC, Modic change. MC variables are based on T1- and T2-weighted fast spin echo images, not STIR

Fig. 1.

Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) for all effect modifiers (per protocol). RMDQ scores range from 0 (no disability) to 24 (maximum disability). Observed difference between treatment groups (mean ± 95% CI) and estimated coefficients (with 95% CI) for interaction from the ANCOVA (per protocol) with p values. PP, per protocol; CI, confidence interval; STIR, short tau inversion recovery; MC, Modic change. MC variables are based on T1- and T2-weighted fast spin echo images, not STIR

Fig. 2.

Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) for all effect modifiers (per protocol). ODI scores range from 0 (no disability) to 100 (maximum disability). Observed difference between treatment groups (mean ± 95% CI) and estimated coefficients (with 95% CI) for interaction from the ANCOVA (per protocol) with p values. Missing value not imputed in one patient (excluded). PP, per protocol; CI, confidence interval; STIR, short tau inversion recovery; MC, Modic change. MC variables are based on T1- and T2-weighted fast spin echo images, not STIR

Fig. 3.

Low back pain intensity for all effect modifiers (per protocol). Pain intensity scores range from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain). Observed difference between treatment groups (mean ± 95% CI) and estimated coefficients (with 95% CI) for interaction from the ANCOVA (per protocol) with p values. Missing value not imputed in one patient (excluded). PP, per protocol; CI, confidence interval; STIR, short tau inversion recovery; MC, Modic change. MC variables are based on T1- and T2-weighted fast spin echo images, not STIR

Primary hypothesis—STIR

As hypothesised, the STIR3 group (n = 41) reported the largest effect of amoxicillin; the difference in mean RMDQ score at 1 year between those receiving amoxicillin and those receiving placebo (PP analysis) was − 5.1 (95% CI − 8.2 to − 1.9, p for interaction = 0.008) (Fig. 1). The corresponding difference was − 0.7 (95% CI − 3.1 to 1.7) in the STIR2 group and 1.1 (95% CI − 2.1 to 4.4) in the STIR1 group. The treatment effect in the STIR3 group was − 4.8 points (95% CI − 7.9 to − 1.8; p for interaction = 0.014) in the ITT analysis and − 4.5 RMDQ points (95% CI − 7.9 to − 1.1, p for interaction = 0.14) in the PP model including both composite MRI variables.

STIR volume ≥ 25% of the vertebral body (n = 45) also significantly modified the treatment effect (Fig. 1). In the STIR3 and STIR volume ≥ 25% groups, the effect of amoxicillin was > 4 RMDQ points (cut-off for clinical importance) and also evident for ODI (Fig. 2) but not for LBP intensity (Fig. 3).

Explorative hypothesis—T1/T2

The results for the composite MC variable based on T1/T2 did not reach statistical significance or clinical importance (Fig. 1). Two underlying subgroups significantly modified the treatment effect in favour of amoxicillin: MC volume ≥ 25% and MC height > 50% of the vertebral body (Fig. 1). The treatment effect within these subgroups did not exceed the threshold for clinical importance.

Post hoc analyses of STIR3

The baseline characteristics of the STIR3 patients were similar in both treatment groups (Appendix, Table A5). The STIR3 patients and total sample had similar mean baseline RMDQ scores (amoxicillin/placebo 12.8/12.6 vs. 12.7/12.8) and prior disc surgery rates (16% vs. 21%).

The number of STIR3 patients needed to be treated to achieve > 30% improved RMDQ score at 1 year was 3.1 (95% CI 1.7 to 27) (Appendix, Tables A2–A3). Among patients receiving amoxicillin, 6 of 22 STIR3 patients (27%) improved > 75% compared with 9 of 41 (22%) STIR2 patients and no STIR1 patients.

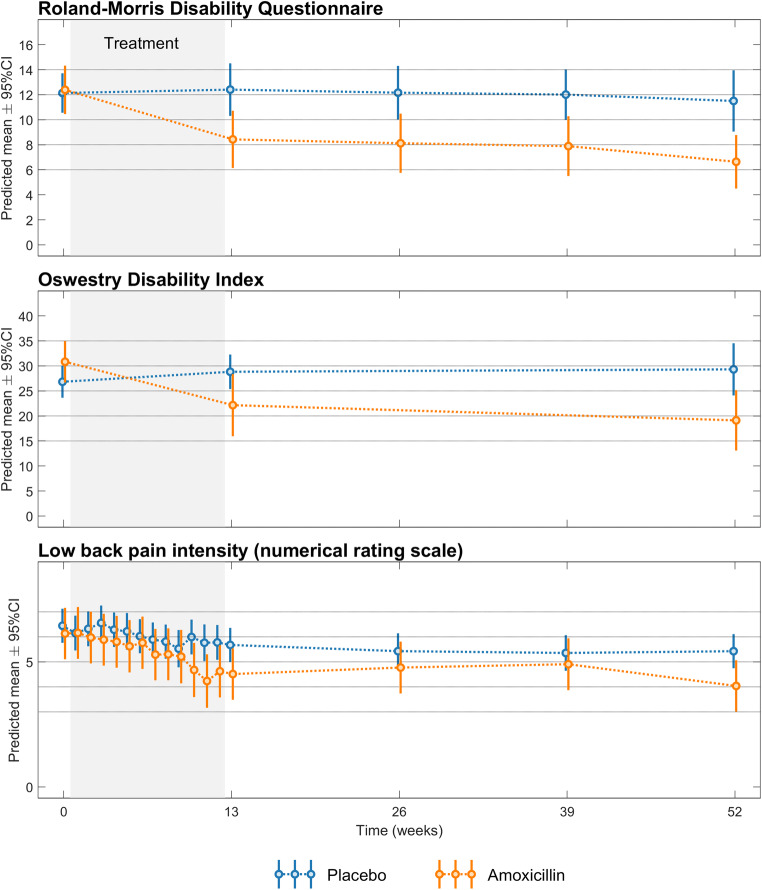

The treatment effect of amoxicillin in the STIR3 group was present at 3 months and remained until the end of the study at 1 year (Fig. 4), but the change in RMDQ score varied considerably between patients (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Treatment effect over time for STIR3 patients (per protocol). Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire score (0–24 scale), Oswestry Disability Index score (0–100 scale), and low back pain intensity (0–10 numerical rating scale) from baseline to 1 year in each treatment group. Higher scores imply worse disability/pain. The results are from post hoc analyses

Fig. 5.

Change in the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) score (per protocol). The change in the RMDQ score (0–24 scale) from baseline to 1 year in each treatment group is plotted for STIR1, STIR2, and STIR3 patients; negative values denote improvement. The results are from post hoc analyses. STIR, short tau inversion recovery

Bangs blinding index for STIR3 patients was − 0.01 in the amoxicillin group, indicating perfect blinding, and 0.61 in the placebo group, indicating un-blinding (Appendix, Table A4).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this was the first study to investigate STIR-based effect modifiers of a treatment for chronic LBP with MCs. These effect modifiers were defined by MC-related high signal on STIR at the previously herniated index level(s) hypothesised to contain a low-grade discitis. The STIR3 and STIR volume ≥ 25% groups with abundant high signal modified the treatment effect of amoxicillin. STIR3 patients reported the largest effect (− 5.1 RMDQ points; 95% CI − 8.2 to − 1.9; p for interaction = 0.008). Subgroups based on T1/T2 features of MCs did not report a clinically important effect of amoxicillin. All subgroups were small, and the findings must be interpreted with caution.

Credibility of results

We consider the subgroup effect of STIR3 to have overall moderate credibility based on the criteria predefined in the statistical analysis plan [36] and the results of the post hoc analyses, but some criteria were not fulfilled (Table 4). The interaction of STIR3 and STIR volume ≥ 25% with treatment was found for the related outcomes RMDQ and ODI but not for LBP, and the finding has not yet been replicated in other studies. No tissue samples were taken, and STIR findings alone are not diagnostic for infection [28, 29]. Further data are needed to link extensive oedema on STIR to low-grade disc infection.

Table 4.

Credibility of the subgroup effect of STIR3 (per protocol)

| Criterion/evaluation | Comment |

|---|---|

| (1) Is the subgroup variable a characteristic measured at baseline or after randomisation? | Yes, at baseline. |

| (2) Is the effect suggested by comparisons within rather than between studies? | Yes, within this study. |

| (3) Was the hypothesis specified a priori? | Yes, in the trial protocol and statistical analysis plan |

| (4) Was the direction of the subgroup effect specified a priori? | Yes, and the a priori specified direction was verified |

| (5) Was the subgroup effect one of a small number of hypothesised effects tested? | Yes, the hypothesis was predefined as primary hypothesis for this study and pre-ordered as hypothesis six (F) in trial protocol |

| (6) Does the interaction test suggest a low likelihood that chance explains the apparent subgroup effect? | Yes, p = 0.008, equal to the Bonferroni adjusted alpha of 0.05/6; this strengthened the result, as the six tests were not independent |

| (7) Is the significant subgroup effect independent? | Probably. The subgroup effect only changed from 5.1 to 4.5 RMDQ points when analysing its independence |

| (8) Is the size of the subgroup effect large? | Yes, 5.1 RMDQ points (predefined minimal clinically important value was 4), but its 95% CI was wide (1.9 to 8.2) |

| (9) Is the interaction consistent across studies? | Not clear, no other study has examined this interaction |

| (10) Is the interaction consistent across closely related outcomes within the study? | Partly, consistent across the closely related disability outcomes RMDQ and ODI, but not significant for LBP intensity |

| (11) Is there indirect evidence that supports the hypothesised interaction (biological rationale)? | Partly. Discitis can cause MCs, type 1 MCs can be symptomatic, amoxicillin tended to reduce disability in patients with type 1 MCs (oedema) (see text). STIR3 group (extensive oedema) improved most during antibiotic treatment, like verified Cutibacterium acnes discitis (see text). No tissue samples taken to verify infection. Further evidence (e.g. biological) needed to link extent of oedema on STIR to likeliness of disc infection |

| Comparison of treatment groups | STIR3 treatment groups were similar in clinical baseline characteristics and in concomitant treatment during study, supporting the subgroup effect |

| Responder analyses | STIR3: NNT 3–4 to achieve > 30–75% improved RMDQ from baseline to 1-year follow-up, but wide CIs |

| Treatment effect over time | Small numbers, wide CIs. Most improvement during antibiotic treatment as in verified disc infection. Small changes in placebo group difficult to evaluate; might relate to un-blinding, see below |

| Scatterplot of change in RMDQ score | Change in RMDQ score at 1 year varied a lot within STIR3 amoxicillin group, indicating inconsistent subgroup effect |

| Bangs blinding index | In amoxicillin group − 0.01 (no un-blinding); in placebo group 0.61, i.e. possible un-blinding, which may have impaired improvement—or lack of improvement may have caused high blinding index |

The 11 criteria were defined by Sun et al [34]

STIR, short tau inversion recovery; RMDQ, Rolland-Morris Disability Index; CI, confidence interval; ODI, Oswestry Disability Index; LBP, low back pain; MCs, Modic changes; NNT, number needed treat

Post hoc responder analyses supported an effect of amoxicillin in the STIR3 group, but the estimates showed wide CIs (Appendix, Tables A2–A3). Similar to patients with verified Cutibacterium acnes discitis [40], STIR3 patients improved most during antibiotic treatment (Fig. 4). The clinical course in the STIR3 placebo group is difficult to evaluate for credibility because the natural course in untreated groups with abundant MC-related oedema on STIR is unknown. The STIR3 placebo group reported almost no improvement during the 1-year follow-up (Fig. 4). Placebo groups and sick-listed patients with persistent LBP and type 1 MCs also reported little improvement over 1 year in some studies: 0.5–1.4 points for RMDQ [19, 41, 42], 1.9 points for ODI [43], and 0–2.2 points for LBP [19, 41–43].

Incomplete blinding may have contributed to lack of improvement in our placebo group and an overestimated effect of amoxicillin. All patients were blinded to treatment allocation, but placebo patients still tended to suspect they were not on active treatment (Table A4). This might be due to a lack of treatment effect or lack of side effects [44]. AIM patients with little improvement at 3 months and no side effects were less likely to report at 1 year that they had received antibiotics [21]. The precise impact of incomplete blinding on outcome is unclear [45].

As hypothesised, amoxicillin had the largest effect on RMDQ and ODI in the assumed ‘worst’ category of all STIR variables (Figs. 1 and 2). This was not the case in the type 1 major category on T1/T2, and the effect of placebo in the group ‘MC volume <10%’ is difficult to explain and may be spurious (Fig. 1). Thus, the results for STIR variables appear more credible than the explorative T1/T2 results. Below, we further discuss the STIR3 results that correspond to our predefined primary hypothesis.

STIR3 results—interpretation and implications

The effect of amoxicillin was larger for STIR3 patients than for the original type 1 and type 2 only MC groups (− 2.3 and − 0.1 RMDQ points, respectively) in the primary analysis of AIM [19]. The disability at baseline was similar, not worse in the STIR3 group as expected, and cannot explain the difference. These findings make it relevant to examine patients with extensive MC-related oedema on STIR as a separate subgroup in future treatment studies.

It remains unclear why the treatment effect (RMDQ difference) at 1 year was smaller in the STIR3 group (5.1; 0–24 scale) than in the prior cohort with type 1 MCs (8.3; 0–23 scale) [19]. Baseline MC oedema cannot be compared because the prior trial applied 0.2-T MRI without STIR. Both cohorts had MCs at the level of a prior disc herniation. STIR3 patients had slightly lower baseline RMDQ scores than the previous cohort, less than 13 vs. 15 [19]; baseline LBP scores were similar, above 6.

The STIR3 results were consistent with the hypothesis that some MCs with abundant oedema on STIR might represent low-grade discitis. Importantly, spondylodiscitis was an exclusion criterion and was not suspected on MRI. The STIR3 findings were credible by most of the predefined criteria (Table 4) and the treatment course mirrored that of Cutibacterium acnes discitis.

However, replication of our findings is essential. The effect of amoxicillin in the STIR3 group varied greatly (Fig. 5) and was not evident for LBP intensity. The CI overlapped with the cut-off for clinical importance, bacterial infection was not verified, and un-blinding may have occurred. Additionally, adverse events and antibiotic resistance are potential harms [21].

The present findings support the use of STIR to evaluate MCs. They also motivate further studies of MC-related oedema on STIR in relation to possible biological markers of infection that are currently being investigated by our research group. To achieve an optimal classification of MCs for potential clinical use, MC characteristics not studied here, such as diffusion parameters [46], contrast enhancement, and bone turnover [6], should also be investigated.

Further work is needed to quantify STIR findings. The composite STIR variable was based on both visual assessments and several time-consuming manual measurements. The visually estimated STIR signal volume alone yielded similar results and might be more applicable in a clinical setting. However, precise measurements are preferable in research and may become more feasible with advanced automated techniques [47, 48]. To date, few studies have quantified spinal oedema on MRI [29, 49–51].

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include predefined hypotheses, standardised MRI techniques, and MRI ratings by three experienced radiologists [52]. Additionally, potential effect modifiers were defined and categorised before analysing their modifying impact.

Subgroup studies of clinical trials often have limited statistical power and generalisability [36, 53, 54]. This phenomenon also applies to our study. Our pre-decision in the statistical analysis plan to perform primary PP analyses is debatable, although we also present secondary ITT results. The decision implied that we focused primarily on the effect of amoxicillin and secondarily on the effect of allocating patients to receive amoxicillin [55, 56]. The impact of MRI findings on the treatment effect in patients who did not follow their assigned treatment seemed less relevant to study. PP analyses can create prognostic differences between the treatment groups [55]. However, ITT analyses supported the PP findings.

We evaluated the MRIs at inclusion before defining the subgroups, and the definitions of the MRI subgroups were partly dependent on the MRI data [57]. Furthermore, the composite MRI variables had not been validated. The ratings of STIR signal height and volume were less reliable at L5/S1 inferior to the disc [33]. However, the conclusive rating based on multiple observers’ evaluations was likely more reliable than each observer’s rating [52]. When an MC contained both type 1 and another type, we classified the type 1 part as primary or secondary, but we did not measure its exact size or intensity. Our results may not apply to low-field or 3-T MRI. However, they are likely valid with similar 1.5-T MRI protocols [3] and STIR works well with both low- and high-field scanners [58, 59].

Conclusion

Predefined subgroups with chronic LBP, an index level with prior disc herniation, and abundant MC-related index-level oedema on STIR modified the treatment effect of amoxicillin. This finding shows moderate credibility based on published criteria and post hoc analyses and requires replication.

Supplementary information

(DOCX 683 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank their collaborators in the AIM study group for their contributions.

Abbreviations

- AIM

Antibiotics in Modic changes

- CI

Confidence interval

- ITT

Intention to treat

- LBP

Low back pain

- MCs

Modic changes

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ODI

Oswestry Disability Index

- PP

Per protocol

- RMDQ

Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire

- STIR

Short tau inversion recovery

- T1/T2

T1- and T2-weighted fast spin echo images

Funding

This study has received funding by the South East Norway Regional Health Authority (grant no. 2015-090) and the Western Norway Regional Health Authority (grant nos. HV 911891 and HV 911938), which had no part in the planning, performing, or reporting of the study.

Compliance with ethical standards

Guarantor

The scientific guarantor of this publication is Per Martin Kristoffersen.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript declare no relationships with any companies, whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article.

Statistics and biometry

One of the authors has significant statistical expertise.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients in this study.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics – South East Norway (reference no. 2014/158).

Study subjects or cohorts overlap

Some study subjects or cohorts have been previously reported in (a) Braten LCH et al Efficacy of antibiotic treatment in patients with chronic low back pain and Modic changes (the AIM study): double blind, randomised, placebo controlled, multicentre trial. BMJ 2019;367:l5654, (b) Kristoffersen PM et al Short tau inversion recovery MRI of Modic changes: a reliability study. Acta Radiol Open 2020;9(1):2058460120902402, (c) Braten LCH et al Association of Modic change types and their short tau inversion recovery signals with clinical characteristics- a cross sectional study of chronic low back pain patients in the AIM study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2020;21(1):368, (d) Grotle M et al Cost-utility analysis of antibiotic treatment in patients with chronic low back pain and Modic changes: results from a randomised, placebo-controlled trial in Norway (the AIM study). BMJ Open 2020;10(6):e035461, and (e) Braten LCH et al Clinical effect modifiers of antibiotic treatment in patients with chronic low back pain and Modic changes - Secondary analyses of a randomised, placebo-controlled trial (the AIM study) (accepted, BMC Musculoskelet Disord).

Methodology

• prospective

• randomised controlled trial (subgroup analysis)

• multicentre study

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Modic MT, Steinberg PM, Ross JS, Masaryk TJ, Carter JR. Degenerative disk disease: assessment of changes in vertebral body marrow with MR imaging. Radiology. 1988;166:193–199. doi: 10.1148/radiology.166.1.3336678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Modic MT, Masaryk TJ, Ross JS, Carter JR. Imaging of degenerative disk disease. Radiology. 1988;168:177–186. doi: 10.1148/radiology.168.1.3289089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fields AJ, Battie MC, Herzog RJ, et al. Measuring and reporting of vertebral endplate bone marrow lesions as seen on MRI (Modic changes): recommendations from the ISSLS Degenerative Spinal Phenotypes Group. Eur Spine J. 2019;28:2266–2274. doi: 10.1007/s00586-019-06119-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bendix T, Sorensen JS, Henriksson GA, Bolstad JE, Narvestad EK, Jensen TS. Lumbar Modic changes-a comparison between findings at low- and high-field magnetic resonance imaging. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37:1756–1762. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318257ffce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dudli S, Fields AJ, Samartzis D, Karppinen J, Lotz JC. Pathobiology of Modic changes. Eur Spine J. 2016;25:3723–3734. doi: 10.1007/s00586-016-4459-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jarvinen J, Niinimaki J, Karppinen J, Takalo R, Haapea M, Tervonen O. Does bone scintigraphy show Modic changes associated with increased bone turnover? Eur J Radiol Open. 2020;7:100222. doi: 10.1016/j.ejro.2020.100222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herlin C, Kjaer P, Espeland A, et al. Modic changes-their associations with low back pain and activity limitation: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0200677. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen TS, Karppinen J, Sorensen JS, Niinimaki J, Leboeuf-Yde C. Vertebral endplate signal changes (Modic change): a systematic literature review of prevalence and association with non-specific low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:1407–1422. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0770-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mok FP, Samartzis D, Karppinen J, Fong DY, Luk KD, Cheung KM. Modic changes of the lumbar spine: prevalence, risk factors, and association with disc degeneration and low back pain in a large-scale population-based cohort. Spine J. 2016;16:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2015.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brinjikji W, Diehn FE, Jarvik JG, et al. MRI findings of disc degeneration are more prevalent in adults with low back pain than in asymptomatic controls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36:2394–2399. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanimoglu H, Cevik S, Yilmaz H, et al. Effects of Modic type 1 changes in the vertebrae on low back pain. World Neurosurg. 2019;121:e426–e432. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.09.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maatta JH, Karppinen J, Paananen M, et al. Refined phenotyping of Modic changes: imaging biomarkers of prolonged severe low back pain and disability. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3495. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Splendiani A, Bruno F, Marsecano C, et al. Modic I changes size increase from supine to standing MRI correlates with increase in pain intensity in standing position: uncovering the “biomechanical stress” and “active discopathy” theories in low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2019;28:983–992. doi: 10.1007/s00586-019-05974-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen RK, Leboeuf-Yde C, Wedderkopp N, Sorensen JS, Jensen TS, Manniche C. Is the development of Modic changes associated with clinical symptoms? A 14-month cohort study with MRI. Eur Spine J. 2012;21:2271–2279. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2309-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saukkonen J, Maatta J, Oura P, et al. Association between Modic changes and low back pain in middle age: a northern Finland birth cohort study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2020;45:1360–1367. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000003529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mavrogenis AF, Megaloikonomos PD, Igoumenou VG, et al. Spondylodiscitis revisited. EFORT Open Rev. 2017;2:447–461. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.2.160062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albert HB, Lambert P, Rollason J, et al. Does nuclear tissue infected with bacteria following disc herniations lead to Modic changes in the adjacent vertebrae? Eur Spine J. 2013;22:690–696. doi: 10.1007/s00586-013-2674-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Capoor MN, Birkenmaier C, Wang JC, et al. A review of microscopy-based evidence for the association of Propionibacterium acnes biofilms in degenerative disc disease and other diseased human tissue. Eur Spine J. 2019;28:2951–2971. doi: 10.1007/s00586-019-06086-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albert HB, Sorensen JS, Christensen BS, Manniche C. Antibiotic treatment in patients with chronic low back pain and vertebral bone edema (Modic type 1 changes): a double-blind randomized clinical controlled trial of efficacy. Eur Spine J. 2013;22:697–707. doi: 10.1007/s00586-013-2675-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Storheim K, Espeland A, Grovle L, et al. Antibiotic treatment in patients with chronic low back pain and Modic changes (the AIM study): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2017;18:596. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2306-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braten LCH, Rolfsen MP, Espeland A, et al. Efficacy of antibiotic treatment in patients with chronic low back pain and Modic changes (the AIM study): double blind, randomised, placebo controlled, multicentre trial. BMJ. 2019;367:l5654. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Homagk L, Marmelstein D, Homagk N, Hofmann GO. SponDT (spondylodiscitis diagnosis and treatment): spondylodiscitis scoring system. J Orthop Surg Res. 2019;14:100. doi: 10.1186/s13018-019-1134-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tonbul M, Guzelant AY, Gonen A, Baca E, Ozbaydar MU. Relationship between the size of bone marrow edema of the talus and ankle pain. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2011;101:430–436. doi: 10.7547/1010430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Unay K, Poyanli O, Akan K, Guven M, Demircay C. The relationship between bone marrow edema size and knee pain. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17:1298–1304. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0842-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dudli S, Sing DC, Hu SS et al (2017) Intervertebral disc/bone marrow cross-talk with Modic changes. Eur Spine J. 10.1007/s00586-017-4955-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Finkenstaedt T, Del Grande F, Bolog N, et al. Modic type 1 changes: detection performance of fat-suppressed fluid-sensitive MRI sequences. Rofo. 2017;190:152–160. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-118130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jimenez-Boj E, Nobauer-Huhmann I, Hanslik-Schnabel B, et al. Bone erosions and bone marrow edema as defined by magnetic resonance imaging reflect true bone marrow inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1118–1124. doi: 10.1002/art.22496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shrot S, Sayah A, Berkowitz F. Can the pattern of vertebral marrow oedema differentiate intervertebral disc infection from degenerative changes? Clin Radiol. 2017;72:613.e7–613.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwarz-Nemec U, Friedrich KM, Stihsen C, et al. Vertebral bone marrow and endplate assessment on MR imaging for the differentiation of Modic type 1 endplate changes and infectious spondylodiscitis. J Clin Med. 2020;9:826. doi: 10.3390/jcm9030826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roland M, Fairbank J. The Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire and the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:3115–3124. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grotle M, Brox JI, Vollestad NK. Cross-cultural adaptation of the Norwegian versions of the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire and the Oswestry Disability Index. J Rehabil Med. 2003;35:241–247. doi: 10.1080/16501970306094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB. The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:2940–2952. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kristoffersen PM, Vetti N, Storheim K, et al. Short tau inversion recovery MRI of Modic changes: a reliability study. Acta Radiol Open. 2020;9:2058460120902402. doi: 10.1177/2058460120902402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fleiss JL (1981) Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 2nd ed. John Wiley, New York, pp. 38–46

- 35.Song MK, Lin FC, Ward SE, Fine JP. Composite variables: when and how. Nurs Res. 2013;62:45–49. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3182741948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun X, Briel M, Walter SD, Guyatt GH. Is a subgroup effect believable? Updating criteria to evaluate the credibility of subgroup analyses. BMJ. 2010;340:c117. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kent P, Keating JL, Leboeuf-Yde C. Research methods for subgrouping low back pain. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brookes ST, Whitely E, Egger M, Smith GD, Mulheran PA, Peters TJ. Subgroup analyses in randomized trials: risks of subgroup-specific analyses; power and sample size for the interaction test. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lingsma H, Roozenbeek B, Steyerberg E, IMPACT investigators Covariate adjustment increases statistical power in randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1391. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uckay I, Dinh A, Vauthey L, et al. Spondylodiscitis due to Propionibacterium acnes: report of twenty-nine cases and a review of the literature. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:353–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jensen OK, Nielsen CV, Sorensen JS, Stengaard-Pedersen K. Type 1 Modic changes was a significant risk factor for 1-year outcome in sick-listed low back pain patients: a nested cohort study using magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine. Spine J. 2014;14:2568–2581. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jensen OK, Andersen MH, Ostgard RD, Andersen NT, Rolving N. Probiotics for chronic low back pain with type 1 Modic changes: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with 1-year follow-up using Lactobacillus Rhamnosis GG. Eur Spine J. 2019;28:2478–2248. doi: 10.1007/s00586-019-06046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koivisto K, Kyllonen E, Haapea M, et al. Efficacy of zoledronic acid for chronic low back pain associated with Modic changes in magnetic resonance imaging. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Blinding in randomised trials: hiding who got what. Lancet. 2002;359:696–700. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07816-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moustgaard H, Clayton GL, Jones HE, et al. Impact of blinding on estimated treatment effects in randomised clinical trials: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ. 2020;368:l6802. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l6802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bray TJP, Sakai N, Dudek A, et al. Histographic analysis of oedema and fat in inflamed bone marrow based on quantitative MRI. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:5099–5109. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06785-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Griffith JF, Wang D, Shi L, Yeung DK, Lee R, Shan TL. Computer-aided assessment of spinal inflammation on magnetic resonance images in patients with spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:1789–1797. doi: 10.1002/art.39126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jamaludin A, Lootus M, Kadir T, et al. ISSLS PRIZE IN BIOENGINEERING SCIENCE 2017: automation of reading of radiological features from magnetic resonance images (MRIs) of the lumbar spine without human intervention is comparable with an expert radiologist. Eur Spine J. 2017;26:1374–1383. doi: 10.1007/s00586-017-4956-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chronaiou I, Thomsen RS, Huuse EM, et al. Quantifying bone marrow inflammatory edema in the spine and sacroiliac joints with thresholding. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18:497. doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1861-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tibiletti M, Ciavarro C, Bari V, et al. Semi-quantitative evaluation of signal intensity and contrast-enhancement in Modic changes. Eur Radiol Exp. 2017;1:5. doi: 10.1186/s41747-017-0009-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Y, Videman T, Niemelainen R, Battie MC. Quantitative measures of Modic changes in lumbar spine magnetic resonance imaging: intra- and inter-rater reliability. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:1236–1243. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ecf283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Espeland A, Vetti N, Krakenes J. Are two readers more reliable than one? A study of upper neck ligament scoring on magnetic resonance images. BMC Med Imaging. 2013;13:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2342-13-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Assmann SF, Pocock SJ, Enos LE, Kasten LE. Subgroup analysis and other (mis)uses of baseline data in clinical trials. Lancet. 2000;355:1064–1069. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cuzick J. Forest plots and the interpretation of subgroups. Lancet. 2005;365:1308. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gupta SK. Intention-to-treat concept: a review. Perspect Clin Res. 2011;2:109–112. doi: 10.4103/2229-3485.83221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shrier I, Steele RJ, Verhagen E, Herbert R, Riddell CA, Kaufman JS. Beyond intention to treat: what is the right question? Clin Trials. 2014;11:28–37. doi: 10.1177/1740774513504151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rothwell PM. Treating individuals 2. Subgroup analysis in randomised controlled trials: importance, indications, and interpretation. Lancet. 2005;365:176–186. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17709-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Del Grande F, Santini F, Herzka DA, et al. Fat-suppression techniques for 3-T MR imaging of the musculoskeletal system. Radiographics. 2014;34:217–233. doi: 10.1148/rg.341135130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Delfaut EM, Beltran J, Johnson G, Rousseau J, Marchandise X, Cotten A. Fat suppression in MR imaging: techniques and pitfalls. Radiographics. 1999;19:373–382. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.2.g99mr03373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 683 kb)