Abstract

Grasslands are globally imperilled ecosystems due to widespread conversion to agriculture and there is a concerted effort to catalogue arthropod diversity in grasslands to guide conservation decisions. The Palouse Prairie is one such endangered grassland; a mid-elevation habitat found in Washington and Idaho, United States. Ants (Formicidae) are useful indicators of biodiversity and historical ecological disturbance, but there has been no structured sampling of ants in the Palouse Prairie. To fill this gap, we employed a rapid inventory sampling approach using pitfall traps to capture peak ant activity in five habitat fragments. We complemented our survey with a systemic review of field studies for the ant species found in Palouse Prairie. Our field inventory yielded 17 ant species across 10 genera and our models estimate the total ant species pool to be 27. The highest ant diversity was found in an actively-managed ecological trust in Latah County, Idaho, suggesting that restoration efforts may increase biodiversity. We also report two rarely-collected ants in the Pacific Northwest and a microgyne that may represent an undescribed species related to Brachymyrmex depilis. Our score-counting review revealed that grassland ants in Palouse Prairie have rarely been studied previously and that more ant surveys in temperate grasslands have lagged behind sampling efforts of other global biomes.

Keywords: Palouse Prairie, ant biodiversity, rapid species inventory, agroecosystems, insect conservation, prairies

Introduction

Temperate grasslands and savannah are amongst the most endangered biomes in the world, having the highest rate of conversion to agriculture and the lowest rate of government protection (Hoekstra et al. 2005). In the United States, grasslands, savannah and barrens communities are critically endangered, experiencing > 98% decline in areas since European settlement (Noss and Scott 1995). Since organisms found in prairies are threatened by habitat loss, biodiversity surveys that describe the native and non-native fauna are necessary to help provide information for future conservation efforts and guide restoration to areas subject to impacts. Ants are useful biodiversity indicators in grasslands and characterising ant community composition through rapid assessment is pertinent for monitoring and evaluating global grassland restoration efforts (Peters et al. 2016).

Biodiversity surveys play a strategic role in grassland conservation, aiding arguments that habitats contain rare or endemic species (Van Schalkwyk et al. 2019). Temperate grasslands are host to a wide range of endemic plant and animal communities, including many insects of conservation concern (Sampson and Knopf 1994). A comprehensive list of globally-threatened species, the Red List, counts over 2,000 grassland species that are critically engendered, endangered or vulnerable worldwide, 108 of which are in North America (I.U.C.N. 2020). Grasslands are frequently fragmented by agricultural production and they are, therefore, prone to increased rates of local extinctions through a variety of modes, such as reduced population sizes, increased invaders and elimination of keystone predators (Leach and Givnish 1996).

The Palouse Prairie is an endangered grassland ecosystem that originally encompassed south-eastern Washington State and neighbouring northern Idaho (Looney and Eigenbrode 2012, Noss and Scott 1995). The Palouse landscape is characterised by rolling hills formed from wind-blown fertile loess soils, which form the foundation for plant communities of caespitose grass, co-dominant shrubs and forbs (Looney et al. 2009, Daubenmire 1970). The Palouse Prairie has experienced an estimated 99.9% decline in habitat across its former range due to agricultural land use, making it one of the most imperilled ecosystems in the United States (Donovan et al. 2009, Black et al. 1998). What habitat remains is fragmented into small, narrow strips of land and a majority of these fragments are smaller than two hectares with high perimeter-area ratios (Yates et al. 2004). Encouragingly, these fragments are capable of supporting several endangered species (Looney and Eigenbrode 2012).

Published biodiversity surveys are limited for the Palouse Prairie, encompassing a survey of bumblebees (Hatten et al. 2013), macromoths (Thompson et al. 2014) and forbs (Donovan et al. 2009). In this study, we chose ants (Formicidae) for the biodiversity survey in Palouse Prairie. Ants are used prominently for monitoring because they are ubiquitous in terrestrial ecosystems, sampling is relatively inexpensive and many ant species respond quickly to disturbances (Tiede et al. 2017, Hoffmann 2010, Underwood and Fisher 2006, Folgarait 1998, Andersen 1990). However, in poorly-surveyed regions, using ants as biodiversity indicators can be challenging if taxonomic resources are not well developed (Hevia et al. 2016). The Pacific Northwest Region is generally under-sampled for ants and thus up-to-date taxonomic resources are limited (Hoey-Chamberlain et al. 2010). Consequently, we included a systematic review of all ant species found and referred directly with taxonomic experts to verify all species-level identifications.

Material and methods

Rapid inventory survey

Ant surveys were completed at five prairie fragments: Hudson Biological Reserve, Kamiak Butte County Park, Skinner Ecological Preserve, Idler’s Rest Nature Preserve and Philips Farm County Park (Figs 1, 2, Suppl. material 1). We used a rapid inventory sampling method with pitfall trap transects amongst the five sites (Agosti et al. 2000, Ellison et al. 2007). We used 4 cm diameter, 14 cm depth, pitfall traps filled 2/3 with propylene glycol (Higgins and Lindgren 2012). Our survey intended to capture peak ant activity in August on days above 24°C with no precipitation. We worked in four teams to ensure all traps were placed and collected simultaneously. Pitfall traps were run for 48 h, after which ants were transferred to 95% ethanol. Afterwards, ants were pinned for later identification and storage. In total, we ran 131 pitfall traps and collected 424 individual ants (Suppl. material 2).

Figure 1.

Example of an intact Palouse Prairie habitat fragment located at the Hudson Biological Preserve (“Smoot Hill”) in Albion, Washington.

Figure 2.

Map of survey locations for the five Palouse Prairie sites. Red circles encompass the prairie fragment sampled. Inset shows map extent in the Pacific Northwest.

Species-level identification of ants can be time-consuming and difficult in regions with poorly-described ant fauna (reviewed in Ellison 2012). The inland North-western US has few recent records of ants to aid in identification and we thus employed a four-step identification approach. First, all ants were identified to genus using Ant Genera of North America (Fisher and Cover 2007). Second, we used records and pinned specimen photographs posted to online ant taxonomy databases (i.e. Guénard et al. 2017) to identify ants to species. Third, we compared specimens to collections at the Washington State University MT James Museum and the University of Idaho WF Barr Entomological Museum. We also consulted published checklists of ants known from Idaho, Washington and the western United States (Cole 1936, Smith 1941, Yensen et al. 1977, Cook 1953, Wheeler and Wheeler 1986), although these studies reflect the lack of recent comprehensive reports published.

Systematic review methods

We searched for studies in Web of Science that quantified abundance or richness of the ant species within prairie or grassland from 2016 to the present. Our search was conducted in June 2020 using the term “ant AND divers* AND prairie OR ant AND divers* AND grassland”. Our search yielded 106 studies that were reviewed for inclusion, based on three criteria: (i) the study assessed more than one species; (ii) the study was performed in non-agricultural grassland or prairie; and (iii) the biome of the study could be determined; 21 studies met these criteria (Suppl. material 3). We classified the biome of each study using either the site coordinates or other geographic descriptors to locate study areas, then cross-referenced with the EcoRegions web app (Dinerstein et al. 2017).

We examined the frequency of recent publications on each individual species collected in our pitfall survey using the same approach as the biome survey, but instead used the genus and species names as search terms. We tabulated the number of studies from 2010-2020 that reported ant species we found. We read abstracts to ensure that all studies included in this survey involved field observations of the insect species in question and we included multiple species names for recently-revised species (Schär et al. 2018). We did not include purely lab-based studies on behaviour (i.e. Bordoni et al. 2019).

Statistical methods

Analyses and figure generation were completed in R ver 4.0.2 (CRAN 2020). Visualisation of sites was mapped using ggpmap package (Kahle and Wickham 2013). Species accumulation curves were run, using the ‘vegan’ package in R (Dixon 2003). We estimated species richness using the Chao1 estimate, an abundance-based estimate of species richness, following decision-tree recommendations (Hortal et al. 2006).

Results

Amongst all sites, we collected 17 ant species (Table 1), with Aphaenogaster occidentalis the most common. Ants in the genus Formica were the most diverse, with six species (Fig. 3). The non-native species Tetramorium immigrans was found in three locations, but was not abundant. We found a single microgyne (miniature queen) similar to Brachymyrmex depilis. Scattered records of similar Brachymyrmex microgynes exist and they have been interpreted as undescribed, socially parasitic species (Moreau et al. 2014, Deyrup 2016). Finally, we collected Temnothorax nevadensis and Formica puberula, two ant species that are rarely collected in Pacific Northwest temperate ecosystems (Guénard et al. 2017).

Table 1.

Studies reporting species found in this survey between, published 2010 and 2020.

Figure 3.

Numbers of ants collected in all pitfalls for each species. Asterisks indicates a species that has recently been revised, thus the literature search includes *Lasius neoniger and **Tetramorium caespitum. Brachymyrmex sp. indicates abundance of the Brachyrmex sp. microgyne collected.

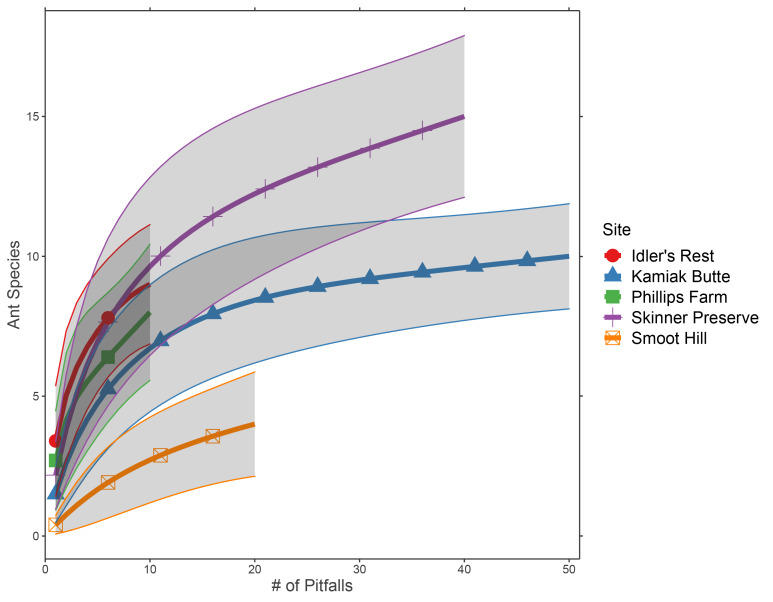

Ant species richness varied amongst sites, with the highest diversity at Skinner Ecological Preserve (Fig. 4) and a total predicted species pool of 27 (Chao1 index = 27.9, SE = 10.2). Skinner Preserve, the largest intact prairie fragment, had the highest species richness (16) and estimated species pool (Chao1 index = 25.8, SE = 10.0). Smoot Hill had the lowest species richness (4) and smallest species pool (Chao1 index = 5.9, SE = 3.6). Two restored habitats adjacent to Ponderosa Pine – Douglas-Fir forests near Moscow, Idaho had intermediate species pools (Philips Farm [9 species] – Chao1 index = 18.0, SE = 9.2; Idler’s Rest [13.6 species] – Chao1 index = 13.6; SE = 4.8). Kamiak Butte had 11 species (Chao1 index = 13.9; SE = 4.4).

Figure 4.

Species accumulation curve with expected mean species richness plotted for each survey location. Dots and lines show estimated species richness at a given sampling interval, while shaded area shows 95% CI.

We found 95 publications detailing a study containing at least one species observed in our survey (Table 1). No field studies have been published for Formica neoclara, F. puberula and F. subaenescens and only one study included Temnothorax nevadensis (Table 1). These limited numbers show our pitfall sampling found several rarely studied or unstudied ant species. In fact, there were five or fewer publications for all the ant species collected besides the common “tramp species” or urban pests, like Tapinoma sessile and Tetramorium immigrans (Kamura et al. 2007, Uno et al. 2010). Our systematic review of ant biodiversity surveys in different biomes over the last five years revealed a bias towards Tropical & Subtropical Grasslands, Savannahs & Shrublands (eight studies, Cross et al. 2016, Van Schalkwyk et al. 2019, Arcoverde et al. 2016, Lasmar et al. 2020, Dröse et al. 2019, Hlongwane et al. 2019, de Queiroz et al. 2020, Santoandré et al. 2019). We found two studies on Tropical & Subtropical Moist Broadleaf Forests (Lawes et al. 2017, Klunk et al. 2018), one study on Tropical & Subtropical Coniferous Forests (Cuautle et al. 2016), three studies on Temperate Broadleaf & Mixed Forests (Braschler and Baur 2016, Helms et al. 2020, Heuss et al. 2019), one study on Montaine Grasslands & Shrublands (Jamison et al. 2016), three studies on Mediterranean Forests, Woodlands & Scrub (Adams et al. 2018, Catarinue et al. 2018, Flores et al. 2018) and one study on Deserts & Xeric Shrublands (Álvarez and Ojeda 2019). In the last five years, only two citations have included information on ants in Temperate Grasslands, Savannahs and Grassland biomes (Ramos et al. 2018, Kim et al. 2018), the biome that encompasses Palouse Prairie (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Number of ant biodiversity surveys published over a 5-year period from 2016-2020 where locations were reported. Biome classifications inferred from a global terrestrial ecoregion map (Dinerstein et al. 2017).

Discussion

Our model results suggest there are likely many more ant species to be discovered with more intensive sampling in Palouse Prairie and that there is likely to be appreciable diversity of other insect species beyond those of the limited taxonomic focus of this study. Furthermore, one of our collected specimens may be a currently undescribed species of ant, but this putative ant species is rarely collected and taxonomic revision of Brachymyrmex is required to demonstrate if this is the case. In many ecosystems, insect faunas are poorly described (Berenbaum 2008, Dunn 2005). A lack of recent publications on temperate grassland ant faunas and dearth of work on several species collected in Palouse Prairie underscore the importance of survey work in endangered ecosystems. As habitat destruction and fragmentation continue, we may never be able to sample or study the more rarely-collected species (Dunn 2005, Noss and Scott 1995).

Ant communities are under-sampled in cool-temperate ecosystems compared to the tropics and sub-tropics, including temperate grasslands in the north-western United States (Ellison 2012, Radtke et al. 2014). Since ants are excellent biological indicators of ecosystem health, sampling efforts may use our data as a comparison point to see if restoration efforts have been successful (Folgarait 1998, Williams 1994). Luckily, once taxonomic resources are available, assessment of an ecosystem’s ant communities can be completed quickly with greater accuracy of species-level identification (Ellison et al. 2007). The intermediate levels of ant diversity at sites adjacent to forest validate predictions that Palouse Prairie-forest ecotones may support high biodiversity (Morgan et al. 2020) Finally, our estimates of a species pool of 27 reflect similar scales of ant species richness found in large ant surveys in grassland systems, such as Wisconsin, USA tallgrass prairie (29 species in control sites, Kim et al. 2018) and Argentinian grasslands (46 species in grassland sites, Santoandré et al. 2019). However, given our absolute species richness was 17, there is more sampling to be completed to comprehensively describe this fauna. In fact, follow up hand-collect events at Skinner Preserve completed in 2019 found five additional ant species, including Formica altipetens, Formica aserva, Formica obscuripes, Formica ravida and Lasius interjectus (Borowiec, unpublished data).

Research in conservation biological control has shown the value of ants as predators in agroecosystems (Way and Khoo 1992). In our study, we found multiple species of ants in genera often implicated as predators of chewing herbivores, such as Formica and Camponotus (Drummond and Choate 2011). More recent work demonstrates that social insects, including ground-nesting ants, have positive effects on dryland crop yield by increasing water and micronutrient availability to cereals (Evans et al. 2011). However, the value of these ecosystem services likely pales in comparison to the benefit ants could provide as predators of weed seeds (e.g. Evans and Gleeson 2016). Weeds and herbicide resistance are amongst the most economically-challenging pest problems in dryland agriculture (Powell and Shaner 2001) and ants have been implicated in regulating seed banks in other grasslands (Motze et al. 2013). Recovery of more Palouse Prairie could promote higher ant diversity and abundance (Lawes et al. 2017), thus increasing the likelihood that ants are available to provide these critical ecosystem services, including weed seed predation.

Conclusions

The remaining habitat in the Palouse is highly fragmented and only protected by a range of public and private trusts (Looney and Eigenbrode 2012). This is problematic since we found several species of ants that are uncommonly collected. While these species are not endemic to Palouse Prairie, our observations suggest that opportunities to study these insects in grassland habitats are limited. Furthermore, in addition to fragmentation and disturbance from agriculture, several of our sites are invaded by the pavement ant (Tetramorium immigrans), which is associated with disturbed, agricultural habitats (Cerdá et al. 2009). The extremely reduced range of the Palouse Prairie and the presence of invasive species means many other taxonomic groups of animals are in urgent need of sampling before opportunities to describe this fauna are irreversibly lost.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2 metadata

Clark, R.E.

Data type

Figure metadata

File: oo_514441.csv

Figures 3 and 4 metadata

Clark, R.E.

Data type

Figure metadata

File: oo_514440.csv

Figure 5 metadata

Clark, R.E.

Data type

Figure metadata

File: oo_514439.csv

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

KAD, ALC, ECO and REC completed field surveys. REC analysed data. KAD, ALC, GSM and ECO performed the systematic review. KDA, REC and MLB curated and identified ants. All authors contributed to writing and editing the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbate A., Campbell J. Parasitic beechdrops (Epifagus virginiana): a possible ant-pollinated plant. Southeastern Naturalist. 2013;12:661–665. doi: 10.1656/058.012.0318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adams T. A., Staubus W. J., Meyer M. Fire impacts on ant assemblages in California sage scrub. Southwestern Entomologist. 2018;42:323–334. doi: 10.3958/059.043.0204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Agosti D., Majer J. D., Alonso L. E., Schultz T. R. Ants: standard methods for measuring and monitoring biodiversity. 9. Smithsonian Instiution Scholarly Press; Washington, DC: 2000. 280 [Google Scholar]

- Akyürek B., Zeybekoğlu Ü., Görür G., Karavin M. Reported aphid (Hemiptera: Aphidoidea) and ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) species associations from Samsun Province. Journal of the Entomological Research Society. 2016;18(3):97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez F., Ojeda M. Animal diversity and biogeography of the Cuatro Ciénegas Basin. Springer International Publishing; Switzerland: 2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen A. N. The use of ant communities to evaluate change in Australian terrestrial ecosystems: a review and a recipe. Proceedings of the Ecological Society of Australia. 1990;16:347–357. [Google Scholar]

- Arcoverde G. B., Andersen A. N., Setterfield S. A. Is livestock grazing compatible with biodiversity conservation? Impacts on ant communities in the Australian seasonal tropics. Biodiversity and Conservation. 2016;26:883–897. doi: 10.1007/s10531-016-1277-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barton B. T., Ives A. R. Direct and indirect effects of warming on aphids, their predators, and ant mutualists. Ecology. 2014;95(6):1479–1484. doi: 10.1890/13-1977.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenbaum M. Insect conservation and the Entomological Society of America. American Entomologist. 2008;54(2):117–120. doi: 10.1093/ae/54.2.117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Black A. E., Strand E., Morgan P., Scott J. M., Wright R. G., Watson C. Biodiversity and land-use history of the Palouse bioregion: Pre-European to present. Sisk Thomas D., editor. Land use history of North America. U.S. Geological Survey 1998

- Blonder B., Dornhaus A. Time-ordered networks reveal limitations to information flow in ant colonies. PLOS One. 2011;6(5):e20298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordoni A., Matejkova Z., Chimenti L., Massai L., Perito B., Dapporto L., Turillazzi S. Home economics in an oak gall: behavioural and chemical immune strategies against a fungal pathogen in Temnothorax ant nests. The Science of Nature. 2019;106(11):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00114-019-1659-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowens S. R., Glatt D. P., Pratt S. C. Visual navigation during colony emigration by the ant Temnothorax rugatulus. PLOS One. 2013;8(5):e64367. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt M., Gedan K. B., Garcia E. A. Disturbance type affects the distribution of mobile invertebrates in a high salt marsh community. Northeastern Naturalist. 2010;17:103–114. doi: 10.1656/045.017.0108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braschler B., Baur B. Diverse effects of a seven-year grassland fragmentation on major invertebrate groups. PLOS One. 2016;11(2):e0149567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buczkowski G., Bennett G. The influence of forager number and colony size on food distribution in the odorous house ant, Tapinoma sessile. Insectes Sociaux. 2009;56(2):185–192. doi: 10.1007/s00040-009-0011-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buczkowski G. Extreme life history plasticity and the evolution of invasive characteristics in a native ant. Biological Invasions. 2010;12(9):3343–3349. [Google Scholar]

- Buczkowski G., Krushelnycky P. The odorous house ant, Tapinoma sessile (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), as a new temperate-origin invader. Myrmecological News. 2012;16:61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Buczkowski G., Richmond D. The effect of urbanization on ant abundance and diversity: a temporal examination of factors affecting biodiversity. PLOS One. 2012;7(8):e41729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burford B., Lee G., Friedman D., Brachmann E., Khan R., MacArthur Waltz D., McCarty A., Gordon D. Foraging behavior and locomotion of the invasive Argentine ant from winter aggregations. PLOS One. 2018;13(8):e0202117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J., Grodsky S., Halbritter D., Vigueira P., Vigueira C., Keller O., Greenberg C. Asian needle ant (Brachyponera chinensis) and woodland ant responses to repeated applications of fuel reduction methods. Ecosphere. 2019;10(1):e02547. [Google Scholar]

- Cao T. High social density increases foraging and scouting rates and induces polydomy in Temnothorax ants. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 2013;67(11):1799–1807. doi: 10.1007/s00265-013-1587-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Catarinue C., Reyes-López J., Herriaz J. A., Barberá G. G. Effect of pine reforestation associated with soil disturbance on ant assemblages (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in a semi-arid steppe. European Journal of Entomology. 2018;115:562–574. doi: 10.14411/eje.2018.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cerdá X., Palacios R., Retana J. Ant community structure in citrus orchards in the Mediterranean Basin: impoverishment as a consequence of habitat homogeneity. Environmental Entomology. 2009;38(2):317–324. doi: 10.1603/022.038.0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charbonneau D., Hills N., Dornhaus A. 'Lazy' in nature: ant colony time budgets show high 'inactivity' in the field as well as in the lab. Insectes Sociaux. 2015;62(1):31–35. doi: 10.1007/s00040-014-0370-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charbonneau D., Sasaki T., Dornhaus A. Who needs 'lazy' workers? Inactive workers act as a 'reserve' labor force replacing active workers, but inactive workers are not replaced when they are removed. PLOS One. 2017;12(9):e0184074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin D. W., Bennett G. W. Dominance of pavement ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in residential areas of West Lafayette, IN, USA. Journal of Entomological Science. 2018;53(3):379–385. doi: 10.18474/JES17-120.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R. E., Singer M. S. Differences in aggressive behaviors between two ant species determine the ecological consequences of a facultative food-for-protection mutualism. Journal of Insect Behavior. 2018;31(5):510–522. doi: 10.1007/s10905-018-9695-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cole A. C. An annotated list of the ants of Idaho (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) The Canadian Entomologist. 1936;68(2):34–39. doi: 10.4039/Ent6834-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collignon B., Detrain C. Distributed leadership and adaptive decision-making in the ant Tetramorium caespitum. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2010;277(1685):1267–1273. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook T. W. The Ants of California. Pacific Books; IL: 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Cordonnier M., Bellec A., Dumet A., Escarguel G., Kaufmann B. Range limits in sympatric cryptic species: a case study in Tetramorium pavement ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) across a biogeographical boundary. Insect Conservation and Diversity. 2019;12(2):109–120. doi: 10.1111/icad.12316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cordonnier M., Gibert C., Bellec A., Kaufmann B., Escarguel G. Multi-scale impacts of urbanization on species distribution within the genus Tetramorium. Landscape Ecology. 2019;34(8):1937–1948. [Google Scholar]

- Cordonnier M., Bellec A., Escarguel G., Kaufmann B. Effects of urbanization-climate interactions on range expansion in the invasive European pavement ant. Basic and Applied Ecology. 2020;44:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.baae.2020.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cordonnier M., Escarguel G., Dumet A., Kaufmann B. Multiple mating in the context of interspecific hybridization between two Tetramorium ant species. Heredity. 2020;124(5):675–684. doi: 10.1038/s41437-020-0310-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRAN . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020. R version 4.0.2 R: A language and environment for statistical computing. [Google Scholar]

- Cross A. T., Myers C., Mitchell C. N.A., Cross SL, Jackson C, Waina R, Mucina L, Dixon KW, Andersen AN. Ant biodiversity and its environmental predictors in the North Kimberley region of Australia’s seasonal tropics. Biodiversity and Conservation. 2016;25(9):1727–1759. doi: 10.1007/s10531-016-1154-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cuautle M., Vergara C., Badano E. Comparison of ant community diversity and functional group composition associated to land use change in a seasonally dry oak forests. Neotropical Entomology. 2016;45(2):170–179. doi: 10.1007/s13744-015-0353-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuesta-Segura D., Garcia F., Espadaler X. The westernmost locations of Lasius jensi Seifert, 1982 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): first records in the Iberian Peninsula. Myrmecological News. 2012;16:35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dash S., Sanchez L. New distribution record for the social parasitic Antanergates atratulus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): an IUCN red-listed species. Western North American Naturalist. 2009;69(1):140–141. doi: 10.3398/064.069.0109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daubenmire R. Steppe vegetation of Washington. Vol. 62. Washington Agricultural Experiment Station; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport S., Mull J., Hoagstorm C. Consumption of a dangerous ant (Camponotus vicinus) by a threatened minnow (Notropis simus pecosensis) Southwestern Naturalist. 2013;58(1):126–128. [Google Scholar]

- de Queiroz ACM, Rabello A. M., Braga D. L., Santiago G. S., Zurlo L. F., Philpott S. M., Ribas C. R. Cerrado vegetation types determine how land use impacts on ant biodiversity. Biodiversity and Conservation. 2020;29:2017–2034. doi: 10.1007/s10531-017-1379-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deyrup M. Ants of Florida: Identification and Natural History. CRC Press; 2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dinerstein E., Olson D., Joshi A., Vynne C., Burgess N. D., Wikramanayake E., Hahn N., Palminteri S., Hedao P., Noss R., Hansen M. An ecoregion-based approach to protecting half the terrestrial ealm. Bioscience. 2017;67(6):534–545. doi: 10.1093/biosci/bix014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiRienzo N., Dornhaus A. Temnothorax rugatulus ant colonies consistently vary in nest structure across time and context. PLOS One. 2017;12(6):e0177598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon P. VEGAN, a package of R functions for community ecology. Journal of Vegetation Science. 2003;14:927–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1654-1103.2003.tb02228.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doering G., Pratt S. Queen location and nest site preference influence colony reunification by the ant Temnothorax rugatulus. Insectes Sociaux. 2016;63:585–591. doi: 10.1007/s00040-016-0503-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doering G., Pratt S. Symmetry breaking and pivotal individuals during the re-unification of ant colonies. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2019;222(5):jeb194019. doi: 10.1242/jeb.194019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doering G., Sheehy K., Lichtenstein J., Drawert B., Petzold L., Pruitt J. Sources of intraspecific variation in the collective tempo and synchrony of ant societies. Behavioral Ecology. 2019;30(6):1682–1690. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arz135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doering G., Sheehy K., Barnett J., Pruitt J. Colony size and initial conditions combine to shape colony re-unification dynamics. Behavioural Processes. 2020;170:103994. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2019.103994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan S. M., Looney C., Hanson T., Sánchez de León Y, Wulfhorst JD, Eigenbrode SD, Jennings M, Johnson-Maynard J, Bosque Pérez NA. Reconciling social and biological needs in an endangered ecosystem: The Palouse as a model for bioregional planning. Ecology and Society. 2009;14(1) doi: 10.5751/ES-02736-140109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dröse W., Podgaiski L. R., Dias C. R., Souza Mendonca Md. Local and regional drivers of ant communities in forest-grassland ecotones in South Brazil: A taxonomic and phylogenetic approach. PLOS One. 2019;14(4):e0215310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond F., Choate B. Ants as biological control agents in agricultural cropping systems. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews. 2011;4(2):157–180. doi: 10.1163/187498311X571979. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn R. R. Modern insect extinctions, the neglected majority. Conservation Biology. 2005;19(4):1030–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00078.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison A. M., Record S., Arguello A., Gotelli N. J. Rapid inventory of the ant assemblage in a temperate hardwood forest: species composition and assessment of sampling methods. Environmental Entomology. 2007;36(4):766–775. doi: 10.1093/ee/36.4.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison A. M. Out of Oz: opportunities and challenges for using ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) as biological indicators in north-temperate cold biomes. Myrmecological News. 2012;17:105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Evans T. A., Dawes T. Z., Ward P. R., Lo N. Ants and termites increase crop yield in a dry climate. Nature Communications. 2011;2(1):1–7. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans T. A., Gleeson P. V. Direct measurement of ant predation of weed seeds in wheat cropping. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2016;53(4):1177–1185. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.12640. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher B. L., Cover S. P. Ants genera of North America. University of California Press; 2007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald K., Gordon D. Effects of vegetation cover, presence of a native ant species, and human disturbance on colonization by Argentine ants. Conservation Biology. 2012;26(3):525–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2012.01836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores O., Seoane J., Hevia V., Azcárate F. M. Spatial patterns of species richness and nestedness in ant assemblages along an elevational gradient in a Mediterranean mountain range. PLOS One. 2018;13(12):e0204787. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folgarait P. J. Ant biodiversity and its relationship to ecosystem functioning: a review. Biodiversity & Conservation. 1998;7(9):1221–1244. doi: 10.1023/A:1008891901953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson J., Suarez A., Qazi D., Benson T., Chiavacci S., Merrill L. Prevalence and consequences of ants and other arthropods in active nests of Midwestern birds. Canadian Journal of Zoology. 2019;97(8):696–704. doi: 10.1139/cjz-2018-0182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D., Heller N. The invasive Argentine ant Linepithema humile (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Northern California reserves: from foraging behavior to local spread. Myrmecological News. 2014;19:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Gow E., Wiebe K., Higgins R. Lack of diet segregation during breeding by male and female northern flickers foraging on ants. Journal of Field Ornithology. 2013;84(3):262–269. doi: 10.1111/jofo.12025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guénard Benoit, Weiser M. D., Gomez K., Narula N., Economo E. P. The Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics (GABI) database: synthesizing data on the geographic distribution of ant species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Myrmecological News. 2017;24:83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Guyer A., Hibbard B. E., Holzkämper A., Erb M., Robert C. A.M. Influence of drought on plant performance through changes in belowground tritrophic interactions. Ecology and Evolution. 2018;8(13):6756–6765. doi: 10.1002/ece3.4183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm C. Multivariate discrimination and description of a new species of Tapinoma from the western United States. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 2010;103(1):20–29. doi: 10.1603/008.103.0104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatten T. D., Looney C., Strange J. P., Bosque-Pérez N. A., Jetton R. Bumble bee fauna of Palouse prairie: survey of native bee pollinators in a fragmented ecosystem. Journal of Insect Science. 2013;13(1):1–19. doi: 10.1673/031.013.2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinze J., Rueppell O. The frequency of multi-queen colonies increases with altitude in a Nearctic ant. Ecological Entomology. 2014;39(4):527–529. doi: 10.1111/een.12119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Helms J. A., Ijelu S. E., Wills B. D., Landis D. A., Haddad N. M. Ant biodiversity and ecosystem services in bioenergy landscapes. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 2020;290:106780. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2019.106780. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heuss L., Grevé M. E., Schäfer D., Busch V., Feldhaar H. Direct and indirect effects of land‐use intensification on ant communities in temperate grasslands. Ecology and Evolution. 2019;9(7):4013–4024. doi: 10.1002/ece3.5030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hevia V., Carmona C. P., Azcárate F. M., Torralba M., Alcorlo P., Ariño R., Lozano J., Castro-Cobo R., González J. A. Effects of land use on taxonomic and functional diversity: a cross-taxon analysis in a Mediterranean landscape. Oecologia. 2016;181(4):959–970. doi: 10.1007/s00442-015-3512-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins R., Lindgren B. An evaluation of methods for sampling ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in British Columbia, Canada. Can. Entomol. 2012;144(3):491–507. doi: 10.4039/tce.2012.50. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hlongwane Z. T., Mwabyu T., Munyai T. C., Tsvuura Z. Epigaeic ant diversity and distribution in the Sandstone Sourveld in KwaZulu‐Natal, South Africa. African Journal of Ecology. 2019;57(3):382–393. doi: 10.1111/aje.12615. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra J. M., Boucher T. M., Ricketts T. H., Roberts C. Confronting a biome crisis: global disparities of habitat loss and protection. Ecology Letters. 2005;8(1):23–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00686.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoey-Chamberlain R., Hansen L., Klotz J., McNeeley C. A survey of the ants of Washington and surrounding areas in Idaho and Oregon focusing on disturbed sites (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Sociobiology. 2010;56(1):195–208. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann B. D. Using ants for rangeland monitoring: global patterns in the responses of ant communities to grazing. Ecological Indicators. 2010;10(2):105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2009.04.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hortal J. P., Borges A. V., Gaspar C. Evaluating the performance of species richness estimators: sensitivity to sample grain size. Journal of Animal Ecology. 2006;75(1):274–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2006.01048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- I.U.C.N. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, Version 2020-1. IUCN Red List 2020

- Jamison S. L., Robertson M., Engelbrecht I., Hawkes P. An assessment of rehabilitation success in an African grassland using ants as bioindicators. Koedoe. 2016;58(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Joharchi O., Halliday B., Saboori A. Three new species of Laelaspis berlese from Iran (Acari: Laelapidae), with a review of the species occurring in the Western Palaearctic Region. Journal of Natural History. 2012;46(31-32):1999–2018. doi: 10.1080/00222933.2012.707240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joharchi O., Jalaeian M., Paktinat-Saeej S., Ghafarian A. A new species and new records of Laelaspis berlese (Acari, Laelapidae) from Iran. ZooKeys. 2012;208:17–25. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.208.3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joharchi O., Halliday B. A new species and new records of Gymnolaelaps Berlese from Iran (Acari: Laelapidae), with a review of the species occurring in the Western Palaearctic Region. Zootaxa. 2013;3646(1):39–50. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.3646.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahle D., Wickham H. Ggmap: Spatial Visualization with ggplot2. The R Journal. 2013;5:144–161. doi: 10.32614/RJ-2013-014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamura C. M., Morini M. S.C., Figueiredo C. J., Bueno O. C., Campos-Farinha A. E.C. Ant communities (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in an urban ecosystem near the Atlantic Rainforest. Brazilian Journal of Biology. 2007;67(4):635–641. doi: 10.1590/S1519-69842007000400007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karban R., Grof-Tisza P., McMunn M., Kharouba H., Huntzinger M. Caterpillars escape predation in habitat and thermal refuges. Ecological Entomology. 2015;40(6):725–731. doi: 10.1111/een.12243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaspari M., Chang C., Weaver J. Salted roads and sodium limitation in a northern forest ant community. Ecological Entomology. 2010;35(5):543–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2311.2010.01209.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kautz S., Williams T., Ballhorn D. Ecological importance of cyanogenesis and extrafloral nectar in invasive English laurel, Prunus laurocerasus. Northwest Science. 2017;91(2):214–221. doi: 10.3955/046.091.0210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kimball C. Colony structure in Tapinoma sessile ants of northcentral Colorado: a research note. Entomological News. 2016;125(5):357–362. doi: 10.3157/021.125.0507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kimball C. Independent colong foundation in Tapinoma sessile of northcentral Colorado. Entomological News. 2016;126(2):83–86. doi: 10.3157/021.126.0203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T. N., Bartel S., Wills B. D., Landis D. A., Gratton C. Disturbance differentially affects alpha and beta diversity of ants in tallgrass prairies. Ecosphere. 2018;9(10):e02399. doi: 10.1002/ecs2.2399. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King J., Tschinkel W. Experimental evidence that dispersal drives ant community assembly in human-altered ecosystems. Ecology. 2016;97(1):236–249. doi: 10.1890/15-1105.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjar D., Park Z. Increased ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) incidence and richness are associated with alien plant cover in a small mid-Atlantic riparian forest. Myrmecological News. 2016;22:109–117. [Google Scholar]

- Klunk C. L., Giehl E. L.H., Lopes B. C., Marcineiro F. R., Rosumek F. B. Simple does not mean poor: grasslands and forests harbor similar ant species richness and distinct composition in highlands of southern Brazil. Biota Neotropica. 2018;18(3):e20170507. [Google Scholar]

- Lasmar C. J., Ribas C. R., Louzada J., Queiroz A. C.M., Feitosa R. M., Imata M. M.G.F., Alves P., Nascimento G. B., Neves N. S., Domingos D. Q. Disentangling elevational and vegetational effects on ant diversity patterns. Acta Oecologica. 2020;102:103489. doi: 10.1016/j.actao.2019.103489. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawes M. J., Moore A. M., Andersen A. N., Preece N. D., Franklin D. C. Ants as ecological indicators of rainforest restoration: Community convergence and the development of an Ant Forest Indicator Index in the Australian wet tropics. Ecology and Evolution. 2017;7(20):8442–8455. doi: 10.1002/ece3.2992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach M. K., Givnish T. J. Ecological determinants of species loss in remnant prairies. Science. 1996;273:1555–1558. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5281.1555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz E., Krasnec M., Breed M. Identification of undecane as an alarm pheromone of the ant Formica argentea. Journal of Insect Behavior. 2013;26(1):101–108. doi: 10.1007/s10905-012-9337-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Shao M., Jia Y., Jia X., Huang L., Gan M. Small-scale observation on the effects of burrowing activities of ants on soil hydraulic processes. European Journal of Soil Science. 2019;70(2):236–244. doi: 10.1111/ejss.12748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Looney C., Caldwell B. T., Eigenbrode S. D. When the prairie varies: the importance of site characteristics for strategising insect conservation. Insect Conservation and Diversity. 2009;2(4):243–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4598.2009.00061.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Looney C., Eigenbrode S. D. Characteristics and distribution of Palouse Prairie remnants: implications for conservation planning. Natural Areas Journal. 2012;32(1):75–85. doi: 10.3375/043.032.0109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren J., Toepfer S., Haye T., Kuhlmann U. Haemolymph defence of an invasive herbivore: its breadth of effectiveness against predators. Journal of Applied Entomology. 2010;134(5):439–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0418.2009.01478.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Molnár A. V., Mészáros A., Csathó A. I., Balogh G., Csősz S. Ant species dispersing the seeds of the myrmecochorous Sternbergia colchiciflora (Amaryllidaceae) North-Western Journal of Zoology. 2018;14(2):2565–267. [Google Scholar]

- Moreau C. S., Deyrup M. A., Davis L. R. Ants of the Florida Keys: species accounts, biogeography, and conservation (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Journal of Insect Science. 2014;14(1):295. doi: 10.1093/jisesa/ieu157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan P., Heyerdahl E. K., Strand E. K., Bunting S. C., Riser II J. P., Abatzoglou J. T., Nielsen-Pincus M., Johnson M. Fire and land cover change in the Palouse Prairie–forest ecotone, Washington and Idaho. USA. Fire Ecology. 2020;16:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Motze I., Tscharntke T., Sodhi N. S., Klein A. M., Wanger T. C. Ant seed predation, pesticide applications and farmers’ income from tropical multi-cropping gardens. Agricultural and Forest Entomology. 2013;15(3):245–254. doi: 10.1111/afe.12011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson A., Zapata G., Sentner K., Mooney K. Are ants botanists? Ant associative learning of plant chemicals mediates foraging for carbohydrates. Ecological Entomology. 2020;45(2):251–258. doi: 10.1111/een.12794. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann K., Pinter-Wollman N. Collective responses to heterospecifics emerge from individual differences in aggression. Behavioral Ecology. 2019;30(3):801–808. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arz017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noss R. F., Scott J. M. Endangered ecosystems of the United States: a preliminary assessment of loss and degradation. Vol. 28. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Biological Service; Washington, DC: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ouellette G., Drummond F., Choate B., Groden E. Ant diversity and distribution in Acadia National Park, Maine. Environmental Entomology. 2010;39(5):1447–1456. doi: 10.1603/EN09306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paluh D. J., Eddy C., Ivanov K., Hickerson C. A.M., Anthony C. D. Selective foraging on ants by a terrestrial polymorphic salamander. American Midland Naturalist. 2015;174:265–277. doi: 10.1674/0003-0031-174.2.265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. H., Moon T. Y. Structure of ant assemblages on street trees in urban Busan, Korea. Entomological Research. 2020;50:131–137. doi: 10.1111/1748-5967.12415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pećarević M., Danoff-Burg J., Dunn R. R. Biodiversity on Broadway- enigmatic diversity of the societies of ants (Formicidae) on the streets of New York City. PLOS ONE. 2010;5(10):e13222. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pech P. Hyenism in ants: Non-target ants profit from Polyergus rufescens raids (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Sociobiology. 2014;59(1):67–69. doi: 10.13102/sociobiology.v59i1.667. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters V., Campbell K., Dienno G., García M., Leak E., Loyke C, Ogle M., Steinly B., Crist T. Ants and plants as indicators of biodiversity, ecosystem services, and conservation value in constructed grasslands. Biodiversity and Conservation. 2016;25(8):1481–1501. doi: 10.1007/s10531-016-1120-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Powell B., Brightwell R., Silverman J. Effect of an invasive and native ant on a field population of the black citrus aphid (Hemiptera: Aphididae) Environmental Entomology. 2009;38(6):1618–1625. doi: 10.1603/022.038.0614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell S. B., Shaner D. L. Herbicide Resistance and World Grains. CRC Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Radtke T., Glasier J., Wilson S. Species composition and abundance of ants and other invertebrates in stands of crested wheatgrass (Agropyron cristatum) and native grasslands in the northern Great Plains. Canadian Journal of Zoology. 2014;92:49–55. doi: 10.1139/cjz-2013-0103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos C. S., Isabel Bellocq M., Paris C. I., Filloy J. Environmental drivers of ant species richness and composition across the Argentine Pampas grassland. Austral Ecology. 2018;43(4):424–434. doi: 10.1111/aec.12579. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Resasco J., Pelini S. L., Stuble K. L., Sanders N. J., Dunn R. R., Diamond S. E., Ellison A. M., Gotelli N. J., Levey D. J. Using historical and experimental data to reveal warming effects on ant assemblages. PLOS One. 2014;9(2):e88029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas P., Fragoso C., Mackay W. P. Ant communities along a gradient of plant succession in Mexican tropical coastal dunes. Sociobiology. 2014;61(2):119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Rosas-Mejía M., Vásquez-Bolaños M., Gaona-García G., Vanoye-Eligio V. New records of ant species for Sinaloa, Mexico. Southwestern Entomologist. 2019;44(2):551–554. [Google Scholar]

- Rowles A., Silverman J. Carbohydrate supply limits invasion of natural communities by Argentine ants. Oecologia. 2009;161:161–171. doi: 10.1007/s00442-009-1368-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salyer A., Bennett G., Buczkowski G. Odorous house ants (Tapinoma sessile) as back-seat drivers of localized ant decline in urban habitats. PLOS One. 2014;9(12):e113878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson F., Knopf F. Prairie Conservation in North America. BioScience. 1994;44(6):418–421. doi: 10.2307/1312365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Peña S. House infestation and outdoor winter foraging by the winter ant, Prenolepis imparis Say (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Saltillo, Mexico. Southwestern Entomologist. 2013;38(2):357–360. doi: 10.3958/059.038.0219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santoandré S., Filloy J., Zurita G. A., Bellocq M. I. Taxonomic and functional β-diversity of ants along tree plantation chronosequences differ between contrasting biomes. Basic and Apply Ecology. 2019;41:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.baae.2019.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schär S., Talavera G., Espadeler X., Rana J. D., Andersen A. A., Cover S. P., Vila R. Do Holarctic ant species exist? Trans-Beringian dispersal and homoplasy in the Formicidae. Journal of Biogeography. 2018;45(8):1917–1928. doi: 10.1111/jbi.13380. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt A., Fraser L., Carlyle C., Bassett E. Does cattle grazing affect ant abundance and diversity in temperate grasslands? Rangeland Ecology & Management. 2012;65(3):292–298. doi: 10.2111/REM-D-11-00100.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scholes D., Suarez A. Speed-versus-accuracy trade-offs during nest relocation in Argentine ants (Linepithema humile) and odorous house ants (Tapinoma sessile) Insectes Sociaux. 2009;56(4):413–418. doi: 10.1007/s00040-009-0039-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheard J., Sanders N., Gundlach C., Schär S., Larsen R. Monitoring the influx of new species through citizen science: the first introduced ant in Denmark. PeerJ. 2020;8:e8850. doi: 10.7717/peerj.8850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ślipiński P., Zmihorski M., Czechowski W. Species diversity and nestedness of ant assemblages in an urban environment. European Journal of Entomolog. 2012;109(2):197–206. doi: 10.14411/eje.2012.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith F. A list of the ants of Washington state. Pan Pacific Entomologist. 1941;17:23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sorrells T., Kuritzky L., Kauhanen P., Fitzgerald K., Sturgis S., Chen J., Dijamco C., Basurto K., Gordon D. Chemical defense by the native winter ant (Prenolepis imparis) against the invasive Argentine ant (Linepithema humile) PLOS One. 2011;6(4):e18717. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner F., Seifert B., Moder K., Schlick-Steiner B. A multisource solution for a complex problem in biodiversity research: Description of the cryptic ant species Tetramorium alpestre (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Zoologischer Anzeiger-A Journal of Comparative Zoology. 2010;249(3-4):223–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jcz.2010.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor K., Visvader A., Nowbahari E., Hollis K. Precision rescue behavior in North American ants. Evolutionary Psychology. 2013;11(3):665–677. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C., Tillberg C., Schultz C. Facultative mutualism increases survival of an endangered ant-tended butterfly. Journal of Insect Conservation. 2020;24(2):385–395. doi: 10.1007/s10841-020-00218-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. L., Zack R. S., Crabo L., Landolt P. J. Survey of macromoths (Insecta: Lepidoptera) of a Palouse prairie remnant site in eastern Washington State. Pan-Pacific Entomologist. 2014;90(4):191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Tiede Y., Schlautmann J., Donoso D. A., Wallis C. I.B., Bendix J., Brandl R., Farwig N. Ants as indicators of environmental change and ecosystem processes. Ecological Indicators. 2017;83:527–537. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.01.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toennisson T., Sanders N., Klingeman W., Vail K. Influences on the structure of suburban ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) communities and the abundance of Tapinoma sessile. Environmental Entomology. 2011;40(6):1397–1404. doi: 10.1603/EN11110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood E., Christian C. Consequences of prescribed fire and grazing on grassland ant communities. Environmental Entomology. 2009;38(2):325–332. doi: 10.1603/022.038.0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood E. C., Fisher B. L. The role of ants in conservation monitoring: If, when, and how. Biological Conservation. 2006;132(2):166–182. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2006.03.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uno S., Cotton J., Philpott S. M. Diversity, abundance, and species composition of ants in urban green spaces. Urban Ecosystems. 2010;13(4):425–441. doi: 10.1007/s11252-010-0136-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Schalkwyk J., Pryke J. S., Samways M. J. Contribution of common vs. rare species to species diversity patterns in conservation corridors. Ecological Indicators. 2019;104:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.05.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- VanWeelden M., Bennett G., Buczkowski G. The effects of colony structure and resource abundance on food dispersal in Tapinoma sessile (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Journal of Insect Science. 2015;15(1):10. doi: 10.1093/jisesa/ieu176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonshak M., Gordon D. Intermediate disturbance promotes invasive ant abundance. Biological Conservation. 2015;186:359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2015.03.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner H., Arthofer W., Seifert B., Muster C., Steiner F., Schlick-Steiner B. Light at the end of the tunnel: Integrative taxonomy delimits cryptic species in the Tetramorium caespitum complex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Myrmecological News. 2017;25:95–129. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner H., Karaman C., Aksoy V., Kiran K. A mixed colony of Tetramorium immigrans Santischi, 1927 and the putative social parasite Tetramorium aspina sp.n (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Myrmecological News. 2018;28:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner H., Gamisch A., Arthofer W., Moder K., Steiner F., Schlick-Steiner B. Evolution of morphological crypsis in the Tetramorium caespitum ant species complex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Scientific Reports. 2018;8(1):1–1. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30890-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Strazanac J., Butler L. Association between ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and habitat characteristics in oak-dominated mixed forests. Environmental Entomology. 2001;30(5):842–848. doi: 10.1603/0046-225X-30.5.842. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warren R. J., Giladi I., Bradford M. A. Environmental heterogeneity and interspecific interactions influence nest occupancy by key seed-dispersing ants. Environmental Entomology. 2012;41(3):463–468. doi: 10.1603/EN12027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way M., Khoo K. C. Role of ants in pest management. Annual Review of Entomology. 1992;37:479–503. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.37.010192.002403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weseloh R. Paths of Formica neogagates (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) on tree and shrub leaves: Implications for foraging. Environmental Entomology. 2000;29(3):525–534. doi: 10.1603/0046-225X-29.3.525. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weseloh R. Patterns of foraging of the forest ant Formica neogagates Emery (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) on tree branches. Biological Control. 2001;20:16–22. doi: 10.1006/bcon.2000.0880. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler G. C., Wheeler J. The ants of Nevada. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County; CA: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. F. Exotic ant biology, impact, and control of introduced species. Westview Press; San Francisco, CA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Yates E. D., Levia Jr. D. F., Williams C. L. Recruitment of three non-native invasive plants into a fragmented forest in southern Illinois. Forest Ecology and Managment. 2004;190:119–130. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2003.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yensen N. P., Clark W. H., Francoeur A. A checklist of Idaho ants. The Pan-Pacific Entomologist. 1977;53:181–187. [Google Scholar]

- Yitbarek S., Vandermeer J. H., Allen D. The combined effects of exogenous and endogenous variability on the spatial distribution of ant communities in a forested ecosystem (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Environmental Entomology. 2011;40(5):1067–1073. doi: 10.1603/EN11058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y., Wang D. Response of ants to human-altered habitats with reference to seed dispersal of the myrmecochore Corydalis giraldii Fedde (Papaveraceae) Nordic Journal of Botany. 2018;36(7):e01882. doi: 10.1111/njb.01882. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure 2 metadata

Clark, R.E.

Data type

Figure metadata

File: oo_514441.csv

Figures 3 and 4 metadata

Clark, R.E.

Data type

Figure metadata

File: oo_514440.csv

Figure 5 metadata

Clark, R.E.

Data type

Figure metadata

File: oo_514439.csv