Abstract

Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) precedes multiple myeloma (MM). Population-based screening for MGUS could identify candidates for early treatment in MM. Here we describe the Iceland Screens, Treats, or Prevents Multiple Myeloma study (iStopMM), the first population-based screening study for MGUS including a randomized trial of follow-up strategies. Icelandic residents born before 1976 were offered participation. Blood samples are collected alongside blood sampling in the Icelandic healthcare system. Participants with MGUS are randomized to three study arms. Arm 1 is not contacted, arm 2 follows current guidelines, and arm 3 follows a more intensive strategy. Participants who progress are offered early treatment. Samples are collected longitudinally from arms 2 and 3 for the study biobank. All participants repeatedly answer questionnaires on various exposures and outcomes including quality of life and psychiatric health. National registries on health are cross-linked to all participants. Of the 148,704 individuals in the target population, 80 759 (54.3%) provided informed consent for participation. With a very high participation rate, the data from the iStopMM study will answer important questions on MGUS, including potentials harms and benefits of screening. The study can lead to a paradigm shift in MM therapy towards screening and early therapy.

Subject terms: Randomized controlled trials, Myeloma

Introduction

Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) is characterized by the presence of monoclonal immunoglobulins (M proteins) or an abnormal ratio of free immunoglobulin light chains (FLC) in the blood1. MGUS can be classified by the type of M proteins present. Non-IgM MGUS is the most common type and is defined by the presence of IgG, IgA, and rarely IgD or IgE M proteins2. IgM MGUS is defined by the presence of IgM M proteins3. Light-chain (LC) MGUS is defined by an abnormal FLC-ratio, indicating an excess of monoclonal FLCs in the absence of M proteins4. Non-IgM MGUS and LC-MGUS are caused by monoclonal bone marrow plasma cells (BMPCs) and are the precursor of multiple myeloma (MM), a malignancy of BMPCs5,6. IgM MGUS is caused by monoclonal lymphoplasmacytic lymphocytes and is a precursor to other lymphoproliferative disorders (LP), most notably Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (WM), and rarely MM3. In addition, MGUS of all types, especially LC-MGUS, can precede amyloid light chain amyloidosis (AL)7. Prior studies suggest a 1% annual risk of progressing from MGUS and LC-MGUS to frank malignancy1,3,4,8.

Before progressing to MM or WM, MGUS is believed to pass through a smoldering MM or WM phase (SMM and SWM), which is associated with a higher disease burden than MGUS and LC-MGUS but without MM or WM related organ damage1. Smoldering disease carries a higher risk of progression to active disease than MGUS. Retrospective data from the Mayo Clinic suggest that the risk of progression from SMM to MM is 10% per year for the first five years9, and that the risk of progression of SWM to WM is 60% within 10 years10.

Currently, consensus guidelines recommend indefinite follow-up in MGUS, SMM, and SWM. However, there is no data available from prospective studies or randomized trials regarding optimal clinical management1,11–13. Three recent observational studies from Sweden and the US have consistently demonstrated that individuals with known MGUS prior to the diagnosis of MM have 13–15% better overall survival in MM14–16. These observations indicate that clinical follow-up of precursor disease leads to earlier detection and diagnosis of MM, resulting in fewer patients presenting with symptomatic end-organ damage at the time of MM diagnosis, which may have contributed to the observed better overall survival.

In the clinical setting, the optimal timing of therapy in MM has been a subject of debate. Traditionally, therapy has been reserved for those with MM-related end-organ damage, however, in 2014 the definition of MM was expanded to also include myeloma-defining biomarkers in asymptomatic individuals8. With the advent of newer, more effective, and less toxic drugs, survival has improved dramatically in MM17–19. Three separate randomized controlled trials starting therapy at the stage of SMM have shown improved progression-free survival, and one study showed superior overall survival20–22. Importantly, these studies have shown more favorable toxicity profiles than earlier trials23. In light of these findings some authors now recommend early treatment in high-risk SMM24,25. However, only 2.7–6.0% of MM patients have previously identified precursor disease, which limits the implementation of early treatment in most MM patients14,16. This raises the question of whether population-based screening and follow-up of MGUS could improve the outcomes in MM by identifying candidates for early treatment. However, there is no evidence supporting the implementation of asymptomatic screening for MGUS, and screening is not currently recommended. To address this question, we have launched a population-based screening study with a subsequent randomized controlled trial (RCT) evaluating the risks and benefits of screening and follow-up of MGUS patients.

Here, we describe the design and recruitment of the Iceland Screens, Treats, or Prevents Multiple Myeloma study (iStopMM), a population-based screening study of MGUS and the disorders it precedes and RCT of follow-up strategies.

Methods

Approval

The study protocol, all information material, biobank, and questionnaires were approved by the Icelandic National Bioethics Committee (Number 16–022, date: 2016-04-26) with approval from the Icelandic Data Protection Agency. Access to national healthcare registries has been approved by the Icelandic Directorate of Health and the Icelandic Cancer Society. The study was preregistered on ClinicalTrials.gov (ClinicaTrials.gov identifier: NCT03327597).

Recruitment and screening

The study’s inclusion criteria were being born in 1975 or earlier and residing in Iceland on the 9th of September 2016, as registered in the Icelandic National Registry. Eligible individuals were invited to participate in the iStopMM study (n = 148,711). A letter containing a detailed information brochure and consent form was mailed to them and an extensive campaign on social and conventional media was launched introducing the study to the Icelandic public. This campaign was followed by phone calls to those who had not yet signed up for the study. Participants could provide informed consent through three different mechanisms: (1) returning a signed informed consent form by mail, (2) registering electronically using a participation code included in the invitation letter, or (3) through a secure internet gateway provided by the Icelandic government (island.is), which is accessible to all residents through a secure electronic authentication process. The only exclusion criterion was previously known LP, other than MGUS.

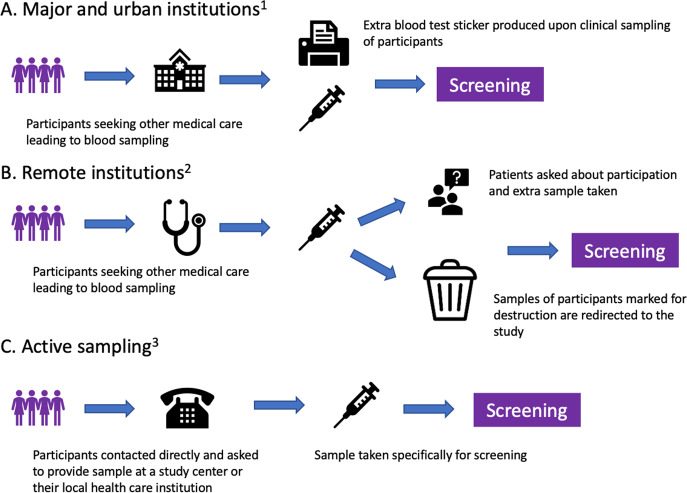

After enrollment, serum samples for screening are collected alongside the collection of blood during clinical care in the universal Icelandic healthcare system, including blood banks (Fig. 1). The study team in collaboration with Landspítali—The National University Hospital of Iceland (LUH), developed an electronic system linking participant data to the central laboratory network of all major and smaller urban healthcare institutions, which covers at least 92% of all Icelandic residents. The system notifies healthcare workers to take an extra blood sample for the study at the point of clinical blood sampling. For smaller rural institutions and private clinics, a manual system was developed whereby laboratory technicians crosslink left-over samples marked for destruction to registered participants and in some cases ask their patients if they are participants in the study and draw an additional sample for the study. To capture samples from participants who do not require clinical blood sampling, an active sampling drive was initiated after three years of passive sample collection.

Fig. 1. Methods of blood sample acquisition.

A and B describe passive sampling starting during the fall of 2016, and C describes active sampling beginning during the fall of 2019. 1: Reykjavik Capital Area, Akureyri, Ísafjörður, Reykjanes Peninsula, Akranes, Healthcare Institution of Northern Iceland, Healthcare Institution of South Iceland, blood banks 2: Neskaupsstaður, Healthcare institution of West Iceland, Healthcare Institution of East Iceland. 3: Available for all Icelandic residents.

All samples are sent to the clinical laboratory at LUH in Reykjavik, Iceland where serum is aliquoted into identical sample tubes and assigned an anonymous study identification number. The laboratory uses TC automation and aliquoter (Thermo Scientific®, MA, USA) for sample handling. Samples are then sent to The Binding Site laboratory in Birmingham, UK where all samples are screened for M protein by capillary zone electrophoresis (CZE; Helena Laboratories, Texas, USA) and for FLC, immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA, and IgM), and total protein by Freelite® and Hevylite® assays performed on an Optilite® turbidimeter (The Binding Site Group Ltd, Birmingham, UK). Immunofixation electrophoresis (IFE; Helena Laboratories, TX, USA) is performed on samples with clear or suspected M protein bands by CZE and/or abnormal FLC results. The CZE and IFE gels are assessed independently by at least two experienced observers.

Randomization and study arms

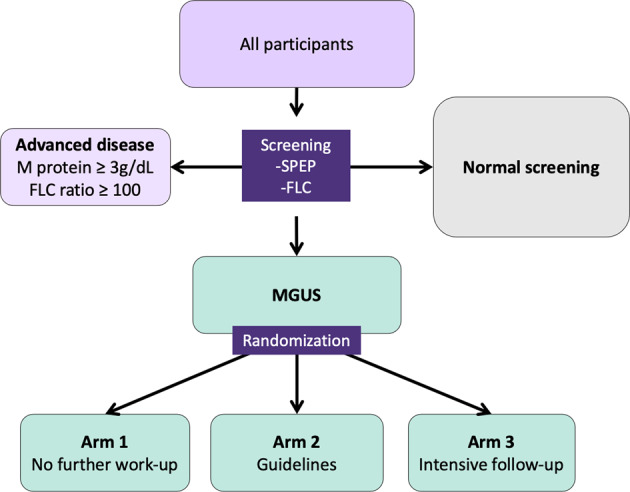

Participants with an M protein or pathological FLC results are considered eligible for the RCT and are randomized into three study arms in a dynamic, non-predetermined manner (Fig. 2). To avoid skewed distribution of high-risk MGUS and LC MGUS, randomization is carried out by blocks of having an M protein >1.5 g/dL and having LC-MGUS. Participants in arm 1 are not informed of their MGUS status and continue to receive conventional healthcare as if they had never been screened. Arm 2 follows current guidelines for follow-up, stratified by low and non-low risk MGUS1. Arm 3 follows a more intensive strategy that is not risk-stratified (see below).

Fig. 2. A flowchart outlining the study design for screening and randomization of individuals with MGUS.

MGUS Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, SPEP Serum protein electrophoresis, FLC Free light chain assay, SMM Smoldering multiple myeloma, MM Multiple myeloma.

Participants with an M protein ≥3.0 g/dL or an FLC ratio ≥100 are not eligible for randomization but are all called in for evaluation since they have, by definition, more advanced disease than MGUS1,8,10. Participants with previously diagnosed MGUS cannot be randomized to arm 1, as they are aware of their MGUS status, and are thus randomized to arms 2 or 3 and will not be included in comparisons with arm 1.

Initial assessment and follow-up

Initial assessment and follow-up of participants in arms 2 and 3 and participants diagnosed with more advanced disease (SMM, SWM, MM, AL, or other LP) at screening is performed in the iStopMM study clinic in Reykjavík, Iceland. Temporary clinics are also regularly established in Akureyri, Ísafjörður, Húsavík, and Egilsstaðir for complete geographical coverage. All participants who are called into the clinic are seen by specialized study nurses and those with more advanced disease are also seen by a physician. The participants undergo a clinical interview and thorough clinical examination and are given detailed oral and written information about their diagnosis and prognosis.

Participants in arm 2 with non-IgM MGUS or LC-MGUS are stratified by having low-risk MGUS or not. These participants are then followed according to guidelines including plain skeletal surveys and bone marrow sampling for those with non-low risk MGUS or when clinically indicated1. All participants in arm 3 follow an intensive follow-up schedule regardless of risk, including bone marrow sampling and whole-body low-dose computerized tomography (WB-LDCT). Participants in arm 2 and 3 with IgM MGUS undergo a computerized tomography (CT) of the abdomen. Diagnostics and follow-up intervals for arms 2 and 3 are shown in Table 1. Participants with smoldering or active disease at baseline or later are followed according to guidelines. This includes intensive follow-up every 4 months or sooner if clinically indicated with annual bone marrow samples and WB-LDCT, as well as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) if no bone lesions are seen on WB-LDCT. Participants who develop intermediate to high-risk SMM, MM, or other related disorders that require treatment are offered participation in a treatment trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03815279) or referred to the hematology unit at LUH or Akureyri Hospital for evaluation, treatment, and follow-up.

Table 1.

Clinical assessment, imaging, and laboratory studies included for participants in the different study arms of the iStopMM study as per protocol.

| Test | Arm 2–low risk and LC-MGUS | Arm 2–non-low risk | Arm 3–All | SMM and SWM | MM and WM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical exama | First visit | First visit | Each visit | Each visit | At diagnosis |

| Blood sampling | |||||

|

SPEP FLC assay |

Each visit | Each visit | Each visit | Each visit | At diagnosis |

| CBC | First visit | Each visit | Each visit | Each visit | At diagnosis |

|

Total calcium Albumin Creatinine |

First visit | First visit | Each visit | Each visit | At diagnosis |

|

CRP LDH ß2M |

– | – | Each visit | Each visit | At diagnosis |

|

TnT pro-BNP |

– | – | Annually | Annually | At diagnosis |

| Bone marrow | |||||

|

Smear Biopsy |

As clinically indicated |

0 months Except if LC |

0 and 60 months | Annually | At diagnosis |

| Urine | |||||

| Protein dipstick | First visit | First visit | – | – | – |

| UPEP | If positive dipstick or if previously abnormal | If positive dipstick or if previously abnormal | – | – | – |

| Albumin/creatinine ratio | – | – | Annually | Annually | At diagnosis |

| ECG | – | – | Annually | Annually | At diagnosis |

| Imaging | |||||

| WB-LDCT | – | – | 0 and 60 months in LC- and non-IgM | Annually in LC- and non-IgM | At diagnosis of MM |

| Plain X-ray of bones | As clinically indicated | First visit in LC- and non-IgM | – | – | – |

| CT abdomen | – | First visit to IgM | 0 and 60 months in IgM | Annually in IgM | At diagnosis of WM |

| MRI of bones | – | – | – | As clinically indicated | – |

| Follow-up | Every 2–3 years | Annual | Annual | Every 4–6 months | Single-visit |

Note that additional sampling and imaging were permitted as clinically indicated and decided at regularly scheduled clinical decision meetings.

SMM smoldering multiple myeloma, SWM smoldering Waldenströms macroglobulinemia, MM multiple myeloma, WM Waldenströms macroglobulinemia, SPEP serum protein electrophoresis, FLC free light chains, CBC complete blood count, CRP C-reactive protein, LDH Lactate dehydrogenase, ß2M ß-2-microglobulin, TnT Troponin T, pro-BPN pro-Brain natriuretic peptide, UPEP Urine protein electrophoresis, ECG electrocardiogram, WB-LDCT whole-body low-dose computerized tomography, CT Computerized tomography, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, LC Light chain.

To detect AL, urine samples are tested for proteinuria in participants visiting the study clinic. In addition, participants in arm 3 and those with more advanced disease are tested for cardiac markers (Table 1). Those with significant proteinuria and decreased kidney function of unclear etiology are referred to a nephrologist for further evaluation. Those with abnormal cardiac markers not explained by known comorbidities are referred to a cardiologist for clinical evaluation and echocardiography. Bone marrow biopsies are stained with Congo red for the presence of amyloid fibrils in all these cases and another testing for AL is performed as clinically indicated.

After each visit, participant’s test results and clinical findings are thoroughly reviewed by the primary investigator and the clinic staff with respect to their disease status and progression at regular clinical decision meetings. Additional testing including repeat bone marrow sampling, imaging, blood sampling, or clinical evaluation is ordered as clinically indicated at or between protocol visits. Diagnoses of SMM, MM, SWM, WM, AL, and other LP are made according to current diagnostic criteria1,8,26,27.

Imaging

Plain radiographs, WB-LDCT, and CT of the abdomen are performed in LUH and Akureyri Hospital. MRI is performed in LUH and Akureyri Hospital. All radiological images are reviewed independently by two physicians, one in specialty training and a senior radiologist at LUH. The radiological assessments are blinded and any discordance in findings is discussed and solved by the two physicians.

Bone marrow samples

Bone marrow sampling is performed by study nurses that have been trained, both locally and in an accredited facility in the United Kingdom (The Royal Marsden Hospital, London, UK). Samples are collected as bone marrow smears and as trephine biopsies. Bone marrow smears are stained with Giemsa stain and jointly evaluated by two senior hematologists at LUH reporting the percentage of BMPCs or lymphoplasmacytic lymphocytes, lymphoid infiltrates, and sample quality. Trephine biopsies are stained with hematoxylin and eosin, as well as for CD138 before being evaluated by two senior hematopathologists at LUH. The sample with the higher percentage of BMPCs/lymphocytic infiltration at each sampling time is used to guide follow-up.

Questionnaires

Immediately following informed consent, participants were asked to complete questionnaires on psychiatric symptoms (e.g., anxiety and depressive symptoms) and life satisfaction to establish a baseline prior to screening28–30. Throughout the study period, all participants, regardless of screening status, are asked to complete the same questionnaires electronically at predefined intervals, as well as additional questionnaires on psychiatric health, pain, neuropathic symptoms, and more (Table 2).

Table 2.

Questionnaires sent to participants by email or answered at the study clinic.

| Questionnaire | Subject | Validated? | All | Arm 1 and normal screening | Arm 2 and 3 and advanced diseasea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At registration | One time | Annually | One time | Each visit | |||

| Background | |||||||

| Anthropomorphic data | Weight, height etc. | NA | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Social historyb | Socioeconomic status | NA | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Medical historyc | Medical history | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Habitsd | Environment | NA | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Industrial exposure | Environment | NA | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Quality of life | |||||||

| PHQ9 | Depression | Yes | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| GAD-7 | Anxiety | Yes | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| SWLS | Quality of life | Yes | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Other questions of happiness and wellbeing | Quality of life | No | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| SF-36 | Health-related quality of life | Yes | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| PSS-10 | Stress and anxiety | Yes | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| PCL-5 (MGUS specific) | PTSD from MGUS diagnosis | Yes | ✓ | ||||

| PCL-5 (nonspecific) | PTSD other | Yes | ✓ | ||||

| Symptoms | |||||||

| BPI | Pain | Yes | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| NSS | Neuropathy | Yes | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| DN4 | Neuropathy | Yes | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Symptoms of PMR | PMR | No | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Social background | |||||||

| MSPSS | Social support | Yes | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| CD-RISC-10ICE | Resilience | Yes | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| ACE | Childhood traumatic events | Yes | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| LEC | Lifetime traumatic events | Yes | ✓ | ✓ | |||

Note that all participants were asked to answer four questionnaires when providing informed consent electronically or if they provided an email address in their written consent form.

Questionnaires were not sent to participants who did not provide an email address and were not called into the study.

PHQ9 patient health questionnaire, GAD-7 General anxiety disorder, SWLS satisfaction with life scale, SF-36 36-item short-form survey, PSS-10 perceived stress scale, PCL-5 post-traumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5, BPI brief pain inventory, NSS neuropathy symptom scale, DN4 Douleur neuropathique. PMR polymyalgia rheumatica, MSPSS Multidimensional scale of social support, CD-RISC-10ICE Connor-Davidson resilience scale. ACE adverse childhood events. LEC Lifetime events checklist.

✓Showing the timing of the questionnaire in that row is the time/frequency assigned to that column.

aIncluding MM, WM, SMM, and SWM.

bEmployment, marital status, education, income, and residence.

cIncluding obstetric history for women.

dIncluding smoking and alcohol intake.

Those who visit the study clinic (arms 2 and 3, and individuals with more advanced disease) answer more extensive questionnaires at each clinic visit and annually. Those who are randomized to arm 1 or are screened negative continue to receive the same annual questionnaires. One-time questionnaires, e.g., baseline characteristics, employment history, resilience, social support, and adverse childhood experiences are sent to all participants by email (Table 2).

Currently, 72 918 (90%) of all participants have provided their email addresses. All non-valid email addresses are reviewed by study staff and participants who visit the study clinic are asked to provide a valid email. Participants are reminded to answer the questionnaires in three separate emails.

Registry crosslinking

Several national healthcare-related registries exist in Iceland that can be accurately crosslinked using a government-issued national identification number. Data from these registries are linked to all participants in the iStopMM study at least twice each year. The following registries are linked to the study datasets: (1) The Icelandic Cancer Registry includes information on all cancers diagnosed in Iceland. It has been mandatory for all physicians and pathologists to register diagnoses of cancer since 1955 and it is virtually complete with high diagnostic accuracy and timeliness31; (2) The Icelandic Causes of Death Registry includes all deaths in Iceland including the date and the presumed causes of death. Registration has been mandatory since 1971; (3) The Icelandic Prescription Medicines Registry includes all prescriptions, including whether the prescriptions were filled or not. in Iceland since 2002; (4) The Icelandic Hospital Discharge Registry includes all inpatient admissions in Iceland from 1999 with the dates of admission and discharge, as well as international classification of diseases (ICD) codes for the diagnoses made by treating physicians. The registry also includes outpatient visits at hospitals, including emergency rooms since 2010; (5) The Icelandic Registry of Primary Health Care Contacts includes all primary care visits and registered ICD-coded diagnoses for all primary care encounters in Iceland since 2004; (6) The Icelandic Central Laboratory Database comprises laboratory test results from all major clinical laboratories in Iceland stored in a central database since 1999, including all blood tests for participants prior to participation and during follow-up in the study; (7) All medical records at LUH, the only tertiary care medical center in Iceland and the general acute care hospital for the vast majority of Icelandic residents. This includes clinical notes, anthropometric data, written radiology and pathology reports, microbiology and virology test results, and all other documented clinical data.

Biobanking

Blood samples drawn at each clinic visit are biobanked including cell-free plasma, serum, and plasma. Bone marrow samples are collected for biobanking in parallel to bone marrow sampling. Urine and blood in Blood-RNA tubes (PAXgeneTM) tubes and in mononuclear cell preparation tubes (BD Vacutainer® CPTTM) are collected at sparser timepoints (Table 3). Samples are processed on-site and aliquoted at the study laboratory in Reykjavík, Iceland, and bone marrow samples separated into plasma and buffy coats. The bone marrow buffy coats from non-IgM MGUS and LC-MGUS are further separated into a plasma cell-enriched CD138+ fraction and a CD 138− fraction by Magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) using CD138 MicroBeads and an autoMACS pro cell separator (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). All cell fractions are cryopreserved and stored in liquid nitrogen. Other biobanking samples are frozen and stored in a secure state-of-the-art robotic biobanking facility in Reykjavík, Iceland, and cataloged using unique study identification numbers.

Table 3.

Biosamples included in the study biobank and when they are obtained from participants.

| Sample | Arm 2–Low risk | Arm 2–Non-low risk | Arm 3–All | SMM and SWM–4-month follow-up | SMM and SWM–6-month follow-up | MM and WM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone marrow | ||||||

| Sorted and unsorted cellsa | None | 0 and 60 months | 0 and 60 months | Annually | Annually | At diagnosis |

| Plasma | None | 0 and 60 months | 0 and 60 months | Annually | Annually | At diagnosis |

| Blood | ||||||

| Cell-free plasma (EDTA tube) | 0 months | Annually | Annually | Every 4 months | Every 6 months | At diagnosis |

| Plasma (Li-Hep tubes) | 0 months | Annually | Annually | Every 4 months | Every 6 months | At diagnosis |

| Serum (SST tubes) | 0 months | Annually | Annually | Every 4 months | Every 6 months | At diagnosis |

| Blood RNA (PaxGene® tube) | 0 months | 0 months | 0 months | 0 months | 0 months | At diagnosis |

| Lymphocytes (CPT tube) | 0 months | 0 and 60 months | 0 and 60 months | 0 and 60 months | 0 and 60 months | At diagnosis |

| Urine | 0 months | 0 months | 0 months | Annually | Annually | At diagnosis |

SMM smoldering multiple myeloma, SWM smoldering Walderströms macroglobulinemia, MM multiple myeloma, WM Waldenströms macroglobulinemia.

aBuffy coat from the bone marrow samples. Unsorted in IgM MGUS but stored as CD138+ and CD138− fractions using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) in Non-IgM MGUS and LC-MGUS.

Study monitoring

A study monitor was appointed to review the study protocol and regularly assessed the conduction of the study for compliance with relevant good clinical practice (GCP) principles. An independent data monitoring committee was established including two clinicians and a statistician that are not associated with the study. Interim analyses assessing safety and efficacy data are performed biannually. Additional interim analyses are scheduled when 500 subjects with MGUS have been followed for 6 months and when 100 participants with MGUS have died. When participants who have been randomized have been followed for five years, or if interim analysis shows a difference in the overall survival between arm 1 compared to arms 2 and 3, arm 1 will be discontinued. At that time the participants in arm 1 are unblinded to their MGUS status and offered a choice between randomization to arms 2 or 3, or clinical follow-up in the Icelandic healthcare system.

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint of the study is the overall survival of individuals with MGUS receiving follow-up (arms 2 and 3) compared to those not receiving any follow-up within the study (arm 1) after 5 years of follow-up. Secondary endpoints are cause-specific survival due to MM or other LPs, psychiatric health and well-being, and cost-effectiveness of screening. In addition, study data will be crosslinked to registries and samples in the biobank providing a large dataset for future studies.

Assuming that 3360 individuals with MGUS are identified and the hazard ratio (HR) for the primary outcome is 0.81 as previously described32 the study has 77.2% power to reject the null hypothesis of HR = 1 at 5 years of follow-up and 89.3% power at 7 years of follow-up at an alpha level of 0.05.

Results

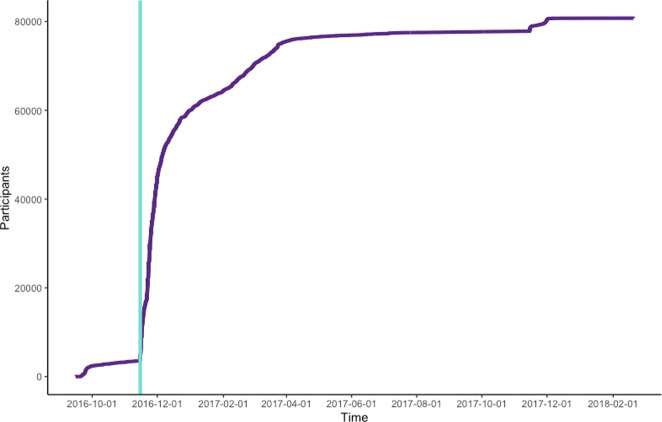

A pilot recruitment phase was started in Akranes (population 7411) in Western Iceland on September 15th, 2016, to ensure that informational materials and processes of recruitment functioned as planned. After minor adjustments, the whole-nation recruitment phase commenced on November 15th, 2016, and continued until February 20th, 2018.

A total of 148,704 individuals born in 1975 and earlier resided in Iceland when enrollment started, constituting the target population of the study. During the 15 months of recruitment, a total of 80,759 (54.3%) individuals provided informed consent for participation in the study (Fig. 3). Written informed consent was provided by 26% of participants while 74% provided informed consent electronically.

Fig. 3. Participant enrollment over the recruitment period.

The light green line represents the end of the pilot period and the initiation of nationwide recruitment.

Of registered participants, 46% were male and 54% female constituting participation rates of 51% and 58%, respectively. Participation was highest (64%) among those between the ages of 60–79 but was lower (46%) in those between the ages of 40–49 and lowest (18%) among those over the age of 90 years old. The majority of participants (59%) were residents of the Reykjavik Capital Area with 18% and 23% of participants residing in other urban centers (more than 5000 inhabitants) and in rural areas, respectively. The participation rates were higher among those not residing in the Reykjavík Capital Area (60% versus 51% in the Reykjavík Capital Area; Table 4).

Table 4.

The age, sex, and geographical distribution of participants and the target population, as well as available national registry data at the close of study recruitment.

| Registered participants | Target population | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 80,759 | 148,704 |

| % females | 54% | 51% |

| median agea | 59 | 57 |

| Age rangea | 40–104 | 40–107 |

| Participation rate | ||

| All | 54% | – |

| Males | 51% | – |

| Females | 58% | – |

| Age group (male/female)a | ||

| 40–49 (%) | 21.2%/23.7% | 27.4%/26.0% |

| 50–59 (%) | 27.7%/29.9% | 29.4%/28.7% |

| 60–69 (%) | 28.4%/26.1% | 23.4%/22.4% |

| 70–79 (%) | 16.6%/14.4% | 12.9%/13.3% |

| 80–89 (%) | 5.7%/5.3% | 6.0%/7.8% |

| >90 (%) | 0.4%/0.5% | 0.9%/1.8% |

| Place of residence | ||

| Reykjavik Capital Area | 58.7% | 62.9% |

| Other urban centersb | 17.5% | 15.6% |

| Rural | 23.3% | 21.1% |

| Missing | 0.6% | 0.4% |

| Known MGUSc | 246 (0.3%) | – |

| Previous LPd | 548 (0.7%) | – |

| Data from registriese | ||

| n hospital admissions | 190,382 | – |

| n primary care visits | 8,187,805 | – |

| n cancers diagnoses | 10,328 | – |

| n prescriptions | 15,839,376 | – |

aAge at the time of study initiation on September 9th, 2016.

bUrban centers with >5000 inhabitants outside the Capital area.

cAs registered before study enrollment in the Icelandic Cancer Registry since 1955, Icelandic Central Laboratory Database since 1999. and a registry of MGUS cases at Icelandic Private Clinics.

dAs recorded before study enrollment in the Icelandic Cancer Registry since 1955.

eAs recorded in national registries at the close of study enrollment on February 20th, 2018.

A total of 548 (0.7%) of participants had previously known LP before enrollment and were therefore excluded and 246 (0.3%) had previously known MGUS before enrollment. At the close of study enrollment on February 20th, 2018, a total of 190,382 hospital admissions since 1999, 8,187,805 primary health care visits since 2004, 10,328 cancer diagnoses since 1955, and 15,839,376 medication prescriptions in the national registries.

Discussion

The iStopMM study is the first nationwide population-based, prospective screening study, and RCT among individuals with MGUS and the disorders it precedes. A total of 80,755 participants, 54.3% of the whole Icelandic population, born 1975 and earlier have enrolled in the iStopMM study. The high participation rate can be attributed to the extensive promotional effort undertaken in social and conventional media across Iceland where participation in scientific studies has historically been high33–35. In addition, using innovative solutions such as electronic informed consent and sampling parallel to clinical blood draws for screening, participants could easily sign-up and did not need to schedule a blood draw specifically for the study.

MGUS was first described as “benign gammopathy” by Dr. Jan Waldenström in 196036 and later defined as MGUS by Dr. Robert Kyle in 197837. Since then, screening studies in Olmstead county2 and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in the US38,39, in Ghana40, and the PLCO-NCI Cancer Screening Trial41 have fundamentally changed our understanding of MGUS and the disorders it precedes. These studies have provided important evidence directing the course of clinical and basic science in the field and guided the management of individuals with MGUS. The iStopMM study builds upon these studies with nationwide screening and detailed clinical assessment and follow-up of individuals with MGUS within an RCT. Through this design, the iStopMM study aims to evaluate the potential harms and benefits of population-based screening while also providing evidence for the optimal diagnostic approach and follow-up of individuals with MGUS.

Guidelines currently recommend screening for cancers of the breast, cervix, colon, lungs, and prostate42. Cancer screening is controversial due to the high number of individuals needed to be screened to improve clinical outcomes and the high level of false-positive results that may lead to overtreatment, a lower sense of wellbeing, and even psychiatric illness43. In fact, a diagnosis of active cancer, including MM, has been associated with psychiatric disorders44 and suicide45,46. However, the role of screening in these outcomes is not known and such effects have not been shown to result from the diagnosis of pre-cancerous conditions like MGUS47,48. All participants of the iStopMM study are closely monitored for their psychiatric well-being using multiple psychometrically sound questionnaires. This will provide high-quality evidence on the potential psychological harms of MGUS screening that may have wider implications for cancer screening in general. Widely accepted criteria for when population-based disease screening is appropriate was developed by Wilson and Jungner in 196849 and recently expanded further50. As detailed in Table 5, most of these criteria are already filled by MM. However, there are still important questions that need to be answered, most notably whether the benefits of screening outweigh the associated harms and costs. The results of the iStopMM study will provide answers to these outstanding questions on whether population-based screening is warranted in MM.

Table 5.

Application of the Wilson and Jungner criteria and the additional recently proposed emerging criteria to multiple myeloma.

| Criteria | Applies to MM? | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Original criteria49 | ||

| The condition sought should be an important health problem | Yes | MM is the second most common hematological malignancy with 31,810 new cases and 12,770 attributed deaths in 2018 in the United States alone53 |

| There should be an accepted treatment with recognized disease | Yes | Treatment for MM is widely available and international organizations recommending specific care for MM54 |

| Facilities for diagnosis and treatment should be available | Yes | This at least applies to developed countries |

| There should be a recognizable or early symptomatic stage | Yes | MGUS and SMM are clearly established entities1 and precede all cases of MM5,6 |

| There should be a suitable test or examination | Yes | SPEP, IFE, and FLC assays are sensitive and specific tests for MM and its precursors and can easily be repeated to confirm the diagnosis55 |

| The test should be acceptable to the population | Yes | Screening is done by a blood test which is widely acceptable |

| The natural history of the condition, including development from latent to declared disease, should be adequately understood | Yes | Although there is still much to learn about the underlying pathogenesis of MM, a wealth of literature on the subject exists56. Furthermore, the natural history of MM and its development from precursor disorders is adequately understood with studies including decades of follow-up available57 |

| There should be an agreed policy on whom to treat as patients | Yes | Although this is currently a moving target, there are clear guidelines on whom to treat, i.e., those with end-organ damage or myeloma defining events. In light of recent evidence, however, treatment might become available at even earlier stages20,21,58. If and when such early treatment is appropriate, there are institutions in place that will include such treatment in their guidelines |

| The cost of case-finding (including diagnosis and treatment of patients diagnosed) should be economically balanced in relation to possible expenditures on medical care as a whole | Unknown | There are currently no screening studies available for MM and its precursor conditions and a cost-benefit analysis is not available. This will be addressed as part of the iStopMM study |

| Case finding should be a continuing process and not a “once and for all” project | Yes | Since blood sampling for screening can be carried out at any time MM screening can be a continuing process |

| Emerging screening criteria50 | ||

| The screening program should respond to a recognized need | Yes | Although survival in MM has dramatically improved in recent years17–19 the disease remains a major burden on affected individuals and healthcare systems59 |

| The objectives of screening should be defined at the outset | Yes | The objectives of screening for MM are clear: providing earlier treatment for MM |

| There should be a defined target population | Unknown | Currently, a well-defined target population for screening does not exist. This is addressed with regards to age, sex, and various other measures in the iStopMM study. However, due to the dominant white ethnicity of the Icelandic population, race cannot be addressed in the iStopMM study. Another study, the PROMISE study, focuses on the impact of screening in individuals of African descent. (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03689595) |

| There should be scientific evidence of screening program effectiveness | Unknown | The objective of the iStopMM study is to provide this evidence |

| The program should integrate education, testing, clinical services, and program management | Yes | There are excellent patent resources available in MM and its precursor disorders. Any screening program would be able to fulfill this criterion |

| There should be quality assurance, with mechanisms to minimize potential risks of screening | Yes | This organizational issue can be solved in MM screening since there are clear response criteria60 and accepted relevant endpoints like survival available for MM |

| The program should ensure informed choice, confidentiality, and respect for autonomy | Yes | This is a practical issue that does not require scientific proof of concept, although such proof is provided in the iStopMM trial |

| The program should promote equity and access to screening for the entire population | Yes | Since the cost of MM screening is relatively low and requires no specialized equipment at the point of patient care, equity in testing is therefore feasible. Follow-up for precursor disorders and treatment for MM can however be expensive and could lead to inequity in non-universal healthcare systems |

| Program evaluation should be planned from the outset | Yes | The practical issue of evaluation is possible for MM as proven by the methodology described above |

| The overall benefits of screening should outweigh the harm | Unknown | This is the principal study objective of the iStopMM study |

Current clinical consensus guidelines for MGUS are not based on RCT data but rather on observational studies and expert opinions1,11–13. By conducting an RCT of different follow-up strategies, the iStopMM study aims to provide high-quality evidence for the optimal follow-up in MGUS. This includes the role of clinical assessment, questionnaires on symptoms, imaging, blood, bone marrow, and urine sampling. In addition, for research purposes, these clinical parameters are crosslinked to past and future testing in the Universal Icelandic healthcare, as well as health-related endpoints such as all cancers and death. Furthermore, novel testing modalities like next-generation flow cytometry of plasma cells in the blood and bone marrow51 and their microenvironment, mass spectrometry52, and single-cell, and germline genetics will be utilized to investigate their role in clinical management and to gain insight into the pathogenesis of MGUS and the biological processes involved in its progression to more advanced disorders. This is even further supplemented by the study´s extensive biobank, which includes blood, bone marrow, and urine samples collected repeatedly over the study period that can be retrieved at a later date for all participants or for participants of particular interest. With this extensive dataset and biobank, the iStopMM results will generate one of the most complete datasets on MGUS to date, providing unique opportunities for future studies.

The iStopMM study has some limitations. Firstly, the study is performed in Iceland which has a highly genetically homogenous white population and generalization of the study findings in non-white populations is somewhat limited. Secondly, by offering early treatment the natural history of MGUS progression to MM is affected. The main ethical issue of the study is that participants in arm 1 are not made aware of their MGUS status. These participants will not gain the potential benefits of screening but will also not be exposed to the potential harms of screening including psychological harms. These participants will continue receiving care in the universal Icelandic healthcare system and may be diagnosed there. Importantly, participants with markers of advanced disease at screening are not randomized to arm 1. Arm 1 will also be followed closely in regular interim analyses and will be unblinded if shown to have inferior survival.

In conclusion, using a novel and innovative recruitment methodology, including electronic informed consent and sampling parallel to clinical blood draws, as well as social and conventional media campaigns, over 80,000 individuals, more than half of the eligible Icelandic population, have enrolled in the iStopMM study. By population-based screening, follow-up of individuals with MGUS within an RCT, and early treatment in MM, the iStopMM study will generate large datasets and sample collections that will impact our basic understanding of MGUS and the disorders it precedes. Furthermore, it holds promise to fundamentally change the paradigm of MM treatment from late treatment in MM patients with end-organ damage to screening and early intervention, improving the overall survival and quality of life for patients worldwide.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The iStopMM study is funded by the Black Swan Research Initiative by the International Myeloma Foundation and the Icelandic Centre for Research (grant agreement No 173857). Furthermore, this project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 716677). Screening tests are performed by The Binding Site Ltd. Birmingham, UK. Additional funding is provided by the University of Iceland, Landspítali University Hospital, and the Icelandic Cancer Society. Crosslinking of study data to national registries is performed by the Icelandic Directorate of Health and the Icelandic Cancer Society. The study is made possible by the hundreds of nurses, laboratory technicians, and physicians around Iceland who collect blood samples from participants for screening or during follow-up and provide clinical care that is not part of the study. Icelandic and International myeloma patient organizations including Perluvinir, the Icelandic myeloma patient organization, and the International Myeloma Foundation have provided the project with important perspectives and networks. The information technology department and clinical laboratory staff at LUH made the complex sampling processes required for the study possible. The staff at Loftfar, Aton, Miðlun and Hvíta Húsið played an integral part in the development of recruiting strategies and media campaigns. Decode genetics have generously provided the study team with important insights and access to their state-of-the-art facilities. Presidents Vigdís Finnbogadóttir and Guðni Th Jóhannesson are thanked for their public support of the study. The iStopMM team including Sigurlína H Steinarsdóttir, Hera Hallbera Björnsdóttir, Tinna Hallsdóttir, Ingibjörg Björnsdóttir, and Eva Brynjarsdóttir are particularly acknowledged for their hard and dedicated work. Special thanks go to the residents of Akranes, Iceland who participated in the pilot and proof-of-concept of the study’s recruitment. Most importantly, acknowledgments go to the thousands of Icelanders who have generously provided their informed consent for the study, answered questionnaires, provided blood samples, and undergone diagnostic testing and follow-up.

Author contributions

The manuscript was written by S.R. and S.Y.K. with additional input from the other coauthors. The study concept was developed by S.Y.K., O.L., and S.H. All the coauthors contributed to the scientific and practical design of the iStopMM study.

Conflict of interest

P.K. is an employee of The Binding Site. BGMD has done consultancy for Amgen, Janssen, Celgene, Takeda. S.H. is the director of The Binding Site. O.L. has received research funding from: National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute (NCI), U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation (MMRF), International Myeloma Foundation (IMF), Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (LLS), Perelman Family Foundation, Rising Tide Foundation, Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Takeda, Glenmark, Seattle Genetics, Karyopharm; Honoraria/ad boards: Adaptive, Amgen, Binding Site, BMS, Celgene, Cellectis, Glenmark, Janssen, Juno, Pfizer; and serves on Independent Data Monitoring Committees (IDMCs) for clinical trials lead by Takeda, Merck, Janssen, Theradex. S.Y.K. has received research funding from International Myeloma Foundation, European Research Council, Icelandic Center for Research (Rannís), Amgen, Celgene. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

3/20/2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41408-023-00814-w

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41408-021-00480-w.

References

- 1.Kyle RA, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma: IMWG consensus perspectives risk factors for progression and guidelines for monitoring and management. Leukemia. 2010;24:1121–1127. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kyle RAMD, et al. Prevalence of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:1362–1369. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kyle RA, et al. Long-term follow-up of IgM monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Blood. 2003;102:3759–3764. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dispenzieri A, et al. Prevalence and risk of progression of light-chain monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: a retrospective population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2010;375:1721–1728. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60482-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Landgren O, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) consistently precedes multiple myeloma: a prospective study. Blood. 2009;113:5412–5417. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-194241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiss BM, Abadie J, Verma P, Howard RS, Kuehl WM. A monoclonal gammopathy precedes multiple myeloma in most patients. Blood. 2009;113:5418–5422. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-195008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiss BM, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) precedes the diagnosis of AL amyloidosis by up to 14 years. Blood. 2011;118:1827. doi: 10.1182/blood.V118.21.1827.1827. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajkumar SV, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e538–e548. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70442-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kyle RA, et al. Clinical course and prognosis of smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;356:2582–2590. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kyle RA, et al. Progression in smoldering Waldenström macroglobulinemia: long-term results. Blood. 2012;119:4462–4466. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-384768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van de Donk NWCJ, et al. The clinical relevance and management of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and related disorders: Recommendations from the European Myeloma Network. Haematologica. 2014;99:984–996. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.100552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bird J, et al. UK myeloma forum (UKMF) and nordic myeloma study group (NMSG): Guidelines for the investigation of newly detected M-proteins and the management of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) Br. J. Haematol. 2009;147:22–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berenson JR, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: a consensus statement: Guideline. Br. J. Haematol. 2010;150:28–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sigurdardottir EE, et al. The role of diagnosis and clinical follow-up of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance on survival in multiple myeloma. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:168–174. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Go RS, Gundrum JD, Neuner JM. Determining the clinical significance of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: a SEER-medicare population analysis. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2015;15:117–186. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goyal G, et al. Impact of prior diagnosis of monoclonal gammopathy on outcomes in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2019;33:1273–1277. doi: 10.1038/s41375-019-0419-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thorsteinsdottir S, et al. Dramatically improved survival in multiple myeloma patients in the recent decade: results from a Swedish population-based study. Haematologica. 2018;103:e412–e415. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2017.183475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar SK, et al. Improved survival in multiple myeloma and the impact of novel therapies. Blood. 2008;111:2516–2520. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kristinsson SY, Landgren O, Dickman PW, Derolf ÅR, Björkholm M. Patterns of survival in multiple myeloma: a population-based study of patients diagnosed in Sweden from 1973 to 2003. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25:1993–1999. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mateos M-V, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for high-risk smoldering multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:438–447. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1300439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lonial S, et al. Randomized trial of lenalidomide versus observation in smoldering multiple myeloma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019;38:1126–1137. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Landgren CO, et al. Daratumumab monotherapy for patients with intermediate-risk or high-risk smoldering multiple myeloma: a randomized, open-label, multicenter, phase 2 study (CENTAURUS) Leukemia. 2020;34:1840–1852. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0718-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao AL, et al. Early or deferred treatment of smoldering multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis on randomized controlled studies. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019;11:5599–5611. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S205623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landgren O. Shall we treat smoldering multiple myeloma in the near future? Hematology. 2017;1:194–204. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2017.1.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kapoor P, Rajkumar SV. Smoldering multiple myeloma: to treat or not to treat. Cancer J. 2019;25:65–71. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castillo JJ, et al. Recommendations for the diagnosis and initial evaluation of patients with Waldenström Macroglobulinaemia: a Task Force from the 8th International Workshop on Waldenström Macroglobulinaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 2016;175:77–86. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision (ICD-10). (2016).

- 28.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin A, Rief W, Klaiberg A, Braehler E. Validity of the brief patient health questionnaire mood scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2006;28:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsem RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985;49:71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sigurdardottir LG, et al. Data quality at the Icelandic Cancer Registry: comparability, validity, timeliness and completeness. Acta Oncol. 2012;51:880–889. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2012.698751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kristinsson SY, et al. Patterns of survival and causes of death following a diagnosis of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: a population-based study. Haematologica. 2009;94:1714–1720. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.010066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harris TB, et al. Age, gene/environment susceptibility-reykjavik study: multidisciplinary applied phenomics. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007;165:1076–1087. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gudbjartsson DF, et al. Large-scale whole-genome sequencing of the Icelandic population. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:435–444. doi: 10.1038/ng.3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jónsson H, et al. Whole genome characterization of sequence diversity of 15,220 Icelanders. Sci. Data. 2017;21:170115. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2017.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waldenström J. Studies on conditions associated with disturbed gamma globulin formation (gammopathies) Harvey Lect. 1960;56:211–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kyle RA. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Natural history in 241 cases. Am. J. Med. 1978;64:814–826. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(78)90522-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Landgren O, et al. Prevalence of myeloma precursor state monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance in 12372 individuals 10-49 years old: a population-based study from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Blood Cancer J. 2017;7:e618. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2017.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Landgren O, et al. Racial disparities in the prevalence of monoclonal gammopathies: a population-based study of 12 482 persons from the national health and nutritional examination survey. Leukemia. 2014;28:1537–1542. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Landgren O, et al. Prevalence of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance among men in Ghana. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2007;82:1468–1473. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)61089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Landgren O, et al. Association of immune marker changes with progression of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance to multiple myeloma. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:1293–1301. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith RA, et al. Cancer screening in the United States, 2019: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019;69:184–210. doi: 10.3322/caac.21557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adami HO, Kalager M, Valdimarsdottir U, Bretthauer M, Ioannidis JPA. Time to abandon early detection cancer screening. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2019;49:e13062. doi: 10.1111/eci.13062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu D, et al. Clinical diagnosis of mental disorders immediately before and after cancer diagnosis: a nationwide matched cohort study in Sweden. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1188–1196. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fang F, et al. Suicide and cardiovascular death after a cancer diagnosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:1310–1318. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hultcrantz M, et al. Incidence and risk factors for suicide and attempted suicide following a diagnosis of hematological malignancy. Cancer Med. 2015;4:147–154. doi: 10.1002/cam4.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Korfage IJ, et al. How distressing is referral to colposcopy in cervical cancer screening? Gynecol. Oncol. 2014;132:142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taghizadeh N, et al. Health-related quality of life and anxiety in the PAN-CAN lung cancer screening cohort. BMJ Open. 2019;9:1–10. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilson, J. M. G. & Jungner, G. World Health Organization. Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease. (World Health Organization, 1968).

- 50.Andermann A., Blancquaert I., Beauchamp S. & Déry V. Revisiting Wilson and Jungner in the genomic age: a review of screening criteria over the past 40 years. Bull. World Health Organ.10.2471/BLT.07.050112 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Flores-Montero J, et al. Immunophenotype of normal vs. myeloma plasma cells: Toward antibody panel specifications for MRD detection in multiple myeloma. Cytom. Part B. 2016;90:61–78. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.21265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mills JR, Barnidge DR, Murray DL. Detecting monoclonal immunoglobulins in human serum using mass spectrometry. Methods. 2015;81:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ludwig H, et al. International Myeloma Working Group recommendations for global myeloma care. Leukemia. 2014;28:981–992. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bradwell AR, et al. Highly sensitive, automated immunoassay for immunoglobulin free light chains in serum and urine. Clin. Chem. 2001;47:673–680. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/47.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anderson KC, Carrasco RD. Pathogenesis of myeloma. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2011;6:249–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kyle RA, et al. Long-term follow-up of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;378:241–249. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Korde, N. et al. Treatment with carfilzomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone with lenalidomide extension in patients with smoldering or newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. JAMA Oncol.10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2010 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Cowan AJ, et al. Global burden of multiple myeloma: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:1221–1227. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kumar S, et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus criteria for response and minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:e328–e346. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30206-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.