Abstract

Background and Aims:

Endoscopic resection (ER) is an important component of the endoscopic treatment of Barrett’s Esophagus (BE) with dysplasia and intramucosal adenocarcinoma (IMC). ER can be performed by cap assisted endoscopic mucosal resection (cEMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). We compared the histological outcomes of ESD versus cEMR, followed by ablation.

Methods:

We queried a prospectively maintained database of all patients undergoing cEMR and ESD followed by ablation at our institution from January 2006 to March 2020 and abstracted relevant demographic and clinical data. Our primary outcomes included the rate of complete remission of dysplasia (CRD): absence of dysplasia on surveillance histology and complete remission of intestinal metaplasia (CRIM): absence of intestinal metaplasia. Our secondary outcome included complication rates.

Results:

We included 537 patients in the study: 456 who underwent cEMR and 81 who underwent ESD. The cumulative probabilities of CRD at 2 years were 75.8% and 85.6% in the cEMR and ESD groups (p< 0.01). Independent predictors of CRD were: ESD (HR: 2.38; p<0.01) and shorter BE segment length (HR: 1.11; p < 0.01). The cumulative probabilities of CRIM at 2 years were 59.3% and 50.6% in cEMR and ESD groups respectively (p>0.05). The only independent predictor of CRIM was a shorter BE segment (HR: 1.16; p < 0.01).

Conclusions:

BE patients with dysplasia or IMC undergoing ESD reach CRD at higher rates than those treated with cEMR, though CRIM rates at two years and complication rates were similar between the two groups.

Keywords: Barrett’s Esophagus, Esophageal Adenocarcinoma, Endoscopic Eradication Therapy, Endoscopic Mucosal Resection, Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection

Introduction

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is the only known precursor lesion of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), a lethal malignancy.1 Endoscopic eradication therapies (EET) have now become the standard of care for the treatment of dysplastic BE and intramucosal EAC (IMC) and the prevention of progression to EAC.2 EET consists of endoscopic resection (ER) of all visible abnormalities followed by endoscopic ablation of “flat” residual BE mucosa.

Initially, ER utilized cap-assisted endoscopic mucosal resection (cEMR) using either a cap and snare technique or the band ligation technique.3 This allowed for accurate histologic staging of disease, in addition to upstaging of pathology in 30–40% of cases and higher interobserver agreement amongst pathologists.4 However, en bloc resection is generally possible only for lesions smaller than 1.5 cm. Larger lesions had to be resected piecemeal, preventing assessment of lateral margins and potentially increasing the rates of recurrence.5

More recent developments in ER include endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), which allows for en bloc resection of larger lesions, enabling more accurate histopathologic staging, with less diagnostic uncertainty.6 Challenges with ESD include limited training opportunities in the West due to lack of large volumes of suitable pathology (such as early gastric cancer), increased time, and a higher complication rate.7 A meta-analysis of 501 patients with BE neoplasia from 11 cohort studies demonstrated that ESD has high rates of en bloc resection, an acceptable safety profile, and low rates of recurrent disease.8 Data show that resection of esophageal squamous neoplasia in a piecemeal fashion is associated with higher recurrence rates than en bloc resection with ESD.9

A pertinent difference between the endoscopic management of gastric/colonic neoplasia and BE neoplasia is that endoscopic resection is typically followed by ablation of residual BE unlike in the stomach/colon which likely influences histological outcomes favorably. There are very limited comparative data on the longer term (histological) outcomes of BE related neoplasia treated by cEMR followed by ablation and those treated by ESD followed by ablation. A small randomized trial of 40 patients comparing cEMR to ESD found no difference in rates of esophagectomy or complete remission of neoplasia between the treatment groups at three months.10

Hence, we aimed to assess histologic outcomes in patients with BE related dysplasia/neoplasia undergoing initial resection with either cEMR or ESD followed by ablative therapy. Our primary outcome of interest was the rate of complete remission of dysplasia (CRD) and complete remission of intestinal metaplasia (CRIM) at 2 years. Our secondary outcome assessed the safety of these two approaches by comparing complication rates.

Methods

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Patient Selection

We queried a prospectively maintained database of all patients undergoing EET for the management of BE or EAC from January 2006-March 2020 at our institution, a quaternary referral center.

Patients were included if they underwent either cEMR or ESD followed by endoscopic ablation for management of dysplastic BE or EAC. Patients who underwent both cEMR and ESD or received surgery or chemoradiation before endoscopic therapy were excluded from the analysis.

Abstracted information included demographics, treatment details, histology, complications (perforation, clinically significant intra or post-procedure bleeding, or stricture formation requiring dilation within 120 days of the initial procedure) and date of last follow up. For patients undergoing cEMR, we also abstracted whether the cap and snare or band ligation method was used.

Methods of EET

Greater than 98% of the procedures during the study period were performed by two endoscopists (PGI and KKW) with considerable expertise in endoscopic resection and ablation of esophageal neoplasia. Patients received general anesthesia, sedation with propofol or conscious sedation. Patients were typically discharged after the procedure, though in certain instances (after large piecemeal resections or ESD), patients were admitted overnight for observation and discharged the next morning.

Standard diagnostic and therapeutic (if needed) endoscopes were used (Olympus, Center Valley, PA or Fujinon-Fujifilm Medical Systems USA, Lexington, MA). Lesions were carefully assessed with narrow band imaging (including near focus) and marked circumferentially with cautery before resection. In general, cEMR was used for lesions less than 1–1.5 cm in diameter, while ESD was used for larger lesions. ESD was utilized at our institution from 2015.

cEMR Procedure

We have previously described the cEMR technique.3 A hard cap (EMR001, Olympus USA, Center Valley, PA) was fitted onto the end of the endoscope. Saline and epinephrine solution was injected submucosally under the lesion of interest. A crescent-shaped snare (SnareMaster Crescent, Olympus USA) was seated on the inner aspect of the cap, followed by suction of the lesion into the cap, closure of the snare and resection using a combination of cutting and coagulation current from an electrosurgical generator utilizing 16 watts blended current (Conmed Beamer, Conmed USA, Utica, NY). For band-ligator EMR, either the Duette Multi-Band Mucosectomy System (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN) or Captivator EMR System (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA) was used. In both kits, a preloaded band ligator was attached to the endoscope to allow for sequential banding of mucosa. Afterwards, a hexagonal snare was utilized to resect the banded tissue with electrocautery.

ESD Procedure

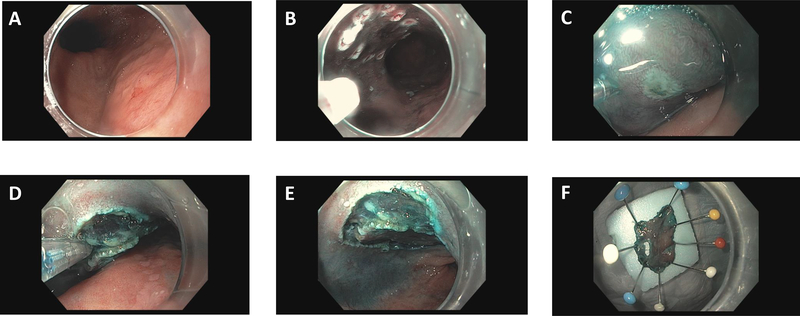

The Olympus water jet endoscope (180J) was utilized with a soft plastic cap attached to the end of the endoscope. A methylene blue, epinephrine and hydroxyl methyl propyl cellulose (HPMC) solution was injected submucosally under the lesion of interest. Incision and dissection were carried out with endoscopic knives, including the DualKnife (Olympus USA), HookKnife (Olympus USA), IT Knife (Olympus USA), or Clutch Cutter (Fujifilm Medical USA) at the discretion of the proceduralist.11 A standard electrosurgical generator (VIO 300D, ENDO CUT Q; Erbe USA Inc, Marietta, Ga, USA) was utilized with appropriate current settings as previously described.12 Resected specimens were pinned to a styrofoam piece, and submitted to pathology for interpretation (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

A. A nodular area is noted in BE mucosa. B. The margins of the lesion are marked with cautery. C. Methylene blue saline injection in utilized to lift the lesion. D. Dissection proceeds utilizing the Hook Knife (Olympus USA, Center Valley, PA). E. The dissection bed after removal of the lesion. F. Pinning of the resected lesion to Styrofoam.

All pathology was read by pathologists with expertise in gastrointestinal pathology. R0 resections were defined as EAC/HGD with both deep and lateral margins negative for dysplasia.

Follow Up

After initial resection, patients were followed at three month intervals to assess for the presence of and treat residual neoplasia and BE.13,14 Careful inspection of the esophageal mucosa was done with both high definition white light endoscopy and narrow band imaging, and surveillance biopsies were obtained15, and ablation was accomplished utilizing radiofrequency ablation (RFA; BarrX device, Medtronic, Minneapolis), liquid nitrogen cryoablation (TruFreeze spray cryotherapy system, Steris, Mentor, OH), or balloon cryoablation (CryoBalloon Focal Ablation System, Pentax Medical, Montvale, NJ). This was applied using standard manufacturer recommended methodology.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

Our primary endpoints were the rate and time to CRD, defined as absence of dysplasia on biopsies from the tubular esophagus and gastroesophageal junction, during at least one surveillance endoscopy and the rate and time to CRIM (defined as absence of intestinal metaplasia on biopsies from the tubular esophagus and gastroesophageal junction, during at least one surveillance endoscopy). Our secondary outcome was the rate of complications (including perforation, clinically significant intra or post-procedure bleeding requiring hospitalization, endoscopic assessment/therapy or receipt of red blood cells within 30 days, or stricture formation requiring dilation within 120 days of the initial procedure). An a priori subgroup analysis was also planned to assess outcomes between patients who underwent piecemeal cEMR (those with more than one resection piece per lesion) versus those who underwent ESD, as piecemeal cEMR is done in larger lesions that may be comparable in size to those that received ESD.

Statistical Analysis

For continuous variables, descriptive statistics were presented as mean (with standard deviation) and for discrete variables as number (percent). The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the cumulative probability of CRD and CRIM, and cumulative probability curves were generated examining the time to outcomes of interest based on treatment modality. Cox-proportional hazards models were used to assess the association of baseline covariates with the outcomes of CRD and CRIM. Variables of interest in the models included age (in 10 year increments), sex, BMI (as less than 30 vs greater than or equal to 30), history of ever smoking, length of BE at initial procedure, presence of a hiatal hernia, treatment group (cEMR vs ESD), and histology at baseline procedure (LGD vs HGD/EAC). The alpha-level was set at 0.05 for statistical significance.

Results

From January 2006-June 2020, we identified 537 patients who underwent either cEMR or ESD followed by ablation, of which 456 underwent cEMR and 81 underwent ESD.

Basic demographics between the two groups appeared similar (Table 1). The mean length of resected specimens was larger in the ESD group (23.9 mm vs. 10.9 mm), and the rates of en bloc and R0 resection were also higher in the ESD group. On final histology, there were 88 cases (19.3%) of EAC in the EMR group, and of these, 70 (79.5%) were stage T1a while 18 (20.5%) were T1b stage. In the ESD group, 40 cases (49.4%) of EAC were diagnosed, with 27 (67.5%) T1a and 13(32.5%) T1b stage. Most patients within the EMR group received RFA, while 25 (5.5%) received cryotherapy. In the ESD group, 52 (64.2%) patients received RFA and 11 (13.1%) received cryotherapy.

TABLE 1:

Baseline demographics and procedural outcomes

| Cap EMR (N = 456) | ESD (N = 81) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age | <0.01 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 650.2 (9.8) | 68.6 (10.3) | |

| Sex | 0.83 | ||

| Male (N,%) | 382 (83.8%) | 67 (82.7%) | |

| Female (N,%) | 74 (16.2%) | 14 (17.3%) | |

| BMI | 0.02 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 31.1 (5.5) | 29.4 (5.1) | |

| Smoking Status | 0.35 | ||

| Current | 52 (11.4%) | 9 (11.1%) | |

| Past | 262 (57.5%) | 44 (54.3%) | |

| None | 121 (26.5%) | 27 (33.3%) | |

| Unknown | 21 (4.6%) | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Maximal Barrett’s length | 0.26 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 5.8 (3.7) | 6.3 (4.0) | |

| Hiatal Hernia | 0.43 | ||

| Present (N, %) | 380 (83.3%) | 55 (87.3%) | |

| Mean Follow Up (years) | 11.2 (IQR 6.5–15.7) | 1.4 (IQR 0.8–2.0) | <0.01 |

| Procedural details and outcomes | |||

| Mean (SD) length of resected specimen, mm | 10.9 (3.4) | 23.9 (9.6) | <0.01 |

| In patients undergoing piecemeal EMR, mean (SD) length of lesion, mm * | 21.8 (10.3) | ||

| In patients undergoing piecemeal EMR, mean (SD) number of resected pieces | 3.4 (1.8) | ||

| Pre-Resection Worst Histology | 0.89 | ||

| LGD | 90 (19.6%) | 15 (20.3%) | |

| HGD+EAC | 369 (80.4%) | 59 (79.7%) | |

| Post-Resection Worst Histology | 0.31 | ||

| LGD | 76 (19.1%) | 19 (24.1%) | |

| HGD+EAC | 322 (80.9%) | 60 (75.9%) | |

| EAC Histology | 88 | 40 | <0.01 |

| T1a | 70 (79.5%) | 27 (67.5%) | |

| T1b | 18 (20.5%) | 13 (32.5%) | |

| Ablation Methods | <0.01 | ||

| Radiofrequency (%) | 456 (100%) | 52 (64.2%) | |

| Spray Cryotherapy (%) | 23 (5.0%) | 5 (6.2%) | |

| Balloon Cryotherapy | 2 (0.4%) | 6 (7.4%) | |

| EMR Method | |||

| Cap and Snare (%) | 274 (60.1%) | ||

| Band Ligator (%) | 175 (38.4%) | ||

| ESD Knives | |||

| Clutch-Cutter (%) | 42 (51.9%) | ||

| Hook Knife (%) | 37 (45.7%) | ||

| En Bloc Resection (%) | 191 (41.9%) | 79 (97.5%) | <0.01 |

| R0 Resection (%) | 92 (20.2%) | 47 (58.0%) | <0.01 |

EMR: Endoscopic Mucosal Resection; ESD: Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection; SD: Standard Deviation; LGD: Low Grade Dysplasia; HGD: High Grade Dysplasia; EAC: Esophageal Adenocarcinoma; IQR: Interquartile Range; mm : millimeters

Of 117 who had lesion size described in procedure note prior to resection

Primary Outcomes: Complete Remission of Dysplasia and Complete Remission of Intestinal Metaplasia

In total, 420 patients in the cEMR group achieved CRD over a median follow up of 11.2 years (IQR: 6.5–15.7 years), while 48 patients in the ESD group achieved CRD over a median follow up of 1.4 years (IQR: 0.8–2.0 years).

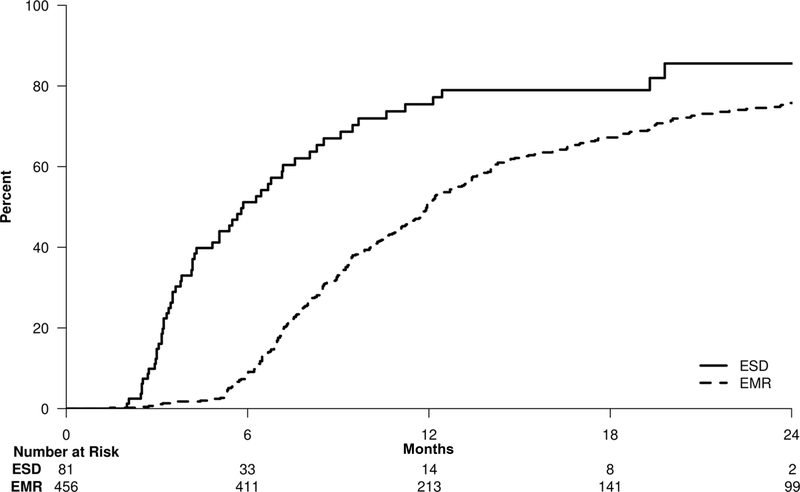

The Kaplan-Meier curve (Figure 2) demonstrates that the 2-year cumulative probability of CRD is lower in cEMR patients compared to ESD patients (75.8% versus 85.6%). Further, univariate analysis demonstrated significantly lower odds of achieving CRD in cEMR patients (HR: 0.41; 95% CI: 0.31–0.54; p<0.01).

Figure 2:

Kaplan-Meier curve for achieving complete remission of dysplasia. At 2 years, the rates of achieving CRD were higher (p< 0.01) in the ESD group (85.6%; 95%CI: 70.5%–94.3%) compared to the cEMR group (75.8%; 95%CI: 71.4%–79.5%).

To assess whether improvements in cEMR technique over time may have contributed to the results, an analysis comparing cEMR (N=48) to ESD (N=80) in patients undergoing procedures from 2015–2019 demonstrated that the odds of CRD remained lower than that of ESD (HR: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.45–0.99; Supplementary Figure 1). Furthermore, within the cEMR group, higher odds of achieving CRD were found in later years (2013–2019; N= 129) compared to earlier years (2006–2012; N=112) of study (HR: 2.09; 95% CI: 1.59–2.75 p<0.01).

Cox proportional hazard models were developed incorporating variables in Table 2. Longer BE segment length was associated with decreased odds of CRD (HR: 0.90; p<0.01), as was treatment with cEMR (HR: 0.42; p< 0.01) compared to ESD.

TABLE 2:

Predictors of Complete Remission of Dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus patients undergoing endoscopic therapy

| Univariate HR (95% CI) | P-Value | Multivariate HR (95% CI) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| 10-Year Increments | 1.04 (0.95–1.15) | 0.36 | 1.03 (0.93–1.40) | 0.55 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | REF | REF | ||

| Male | 1.12 (0.88–1.44) | 0.35 | 1.25 (0.97–1.61) | 0.09 |

| BMI | ||||

| ≥30 | REF | REF | ||

| <30 | 0.94 (0.78–1.12) | 0.47 | 1.19 (0.99–1.44) | 0.07 |

| Smoking | ||||

| Never | REF | REF | ||

| Ever | 1.20 (0.99–1.46) | 0.06 | 1.15 (0.93–1.41) | 0.20 |

| Barrett’s Length | ||||

| 1 cm Increments | 0.91 (0.89–0.94) | <.01 | 0.90 (0.88–0.93) | <.01 |

| Hiatal Hernia | ||||

| Absent | REF | REF | ||

| Present | 0.90 (0.71–1.16) | 0.42 | 0.96 (0.74–1.25) | 0.76 |

| Treatment Group | ||||

| ESD | REF | REF | ||

| Cap EMR | 0.41 (0.31–0.54) | <.01 | 0.42 (0.29–0.59) | <.01 |

| Worst Histology | ||||

| HGD/EAC | REF | REF | ||

| LGD | 1.02 (0.82–1.27) | 0.89 | 0.99 (0.78–1.25) | 0.93 |

OR: Odds Ratio; REF: Reference; BMI: Body Mass Index; ESD: Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection; EMR: Endoscopic Mucosal Resection; LGD: Low Grade Dysplasia; HGD: High Grade Dysplasia; EAC: Esophageal Adenocarcinoma

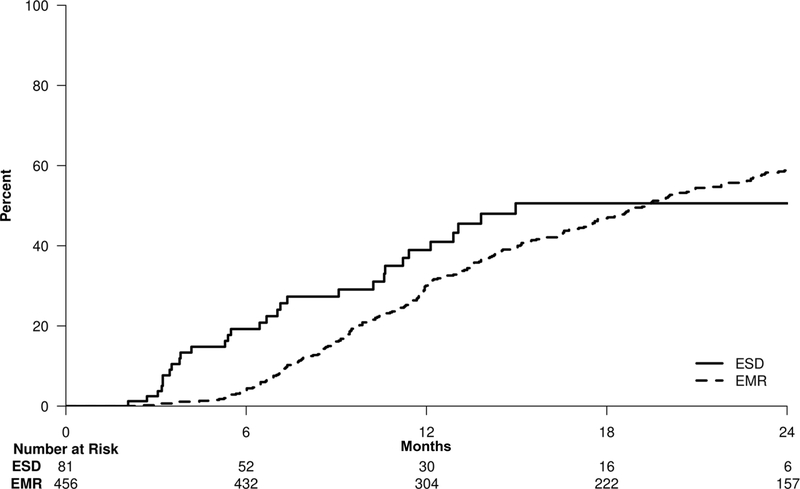

In total, 358 patients (78.5%) in the cEMR group and 33 (40.7%) in the ESD achieved CRIM. The median follow up was 7.8 years (IQR: 3.1–10.5 years) in the cEMR group and was 1.1 years (IQR: 0.6 – 1.8 years) in the ESD group.

The Kaplan-Meier curve in Figure 3 illustrates that while patients in the ESD group tended to achieve CRIM sooner than in the cEMR group, by two years the cumulative probabilities for CRIM in the cEMR and ESD groups were comparable at 59.3% (95% CI:54.3–63.7) and 50.6% (95% CI: 34.9–69.0), respectively. Overall, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in achieving CRIM (cEMR relative to ESD, HR: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.52–1.07; p = 0.11).

Figure 3:

Kaplan-Meier curve for achieving complete remission of intestinal metaplasia. At 2 years, rates of achieving CRIM in the ESD group (50.6%; 95%CI: 34.9%–69.0%) and the cEMR group (59.3%; 95%CI: 54.3%–63.7%) were comparable (p = 0.11).

An analysis comparing cEMR (n=48) to ESD (n=81) in patients undergoing procedures from 2015–2019 demonstrated that the odds of CRIM achievement were not statistically significant between the treatment modalities (HR: 0.88; 95% CI: 0.54–1.43; p = 0.6; Supplementary Figure 2). However, within the cEMR group, higher odds of achieving CRIM were also found in later years (2013–2019) compared to the earlier years (2006–2012) of study (HR:2.01; 95% CI: 1.50–2.69; p <0.01).

On multivariate analysis, the two variables significantly associated with achievement of CRIM were longer BE length, associated with a lower probability of achieving CRIM (HR: 0.86; p < 0.01), and BMI <30, which was associated with higher probability of CRIM (HR: 1.26; p = 0.03; Table 3).

TABLE 3:

Predictors of Complete Remission of Intestinal Metaplasia in Barrett’s esophagus patients undergoing endoscopic therapy

| Univariate HR (95% CI) | P-Value | Multivariate HR (95% CI) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| 10-Year Increments | 0.93 (0.84–1.03) | 0.15 | 0.96 (0.86–1.06) | 0.40 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | REF | REF | ||

| Male | 1.01 (0.78–1.32) | 0.93 | 1.14 (0.86–1.50) | 0.36 |

| BMI | ||||

| ≥30 | REF | REF | ||

| <30 | 0.93 (0.77–1.14) | 0.51 | 1.26 (1.03–1.55) | 0.03 |

| Smoking | ||||

| Never | REF | REF | ||

| Ever | 1.12 (0.91–1.39) | 0.28 | 1.02 (0.82–1.28) | 0.84 |

| Barrett’s Length | ||||

| 1 cm Increments | 0.86 (0.83–0.89) | <.01 | 0.86 (0.83–0.89) | <.01 |

| Hiatal Hernia | ||||

| Absent | REF | REF | ||

| Present | 0.78 (0.60–1.02) | 0.07 | 0.83 (0.63–1.10) | 0.19 |

| Treatment Group | ||||

| ESD | REF | REF | ||

| Cap EMR | 0.74 (0.52–1.07) | 0.11 | 0.78 (0.48–1.27) | 0.32 |

| Worst Histology | ||||

| HGD/EAC | REF | REF | ||

| LGD | 0.9 (0.71–1.16) | 0.42 | 1.10 (0.85–1.42) | 0.47 |

OR: Odds Ratio; REF: Reference; BMI: Body Mass Index; ESD: Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection; EMR: Endoscopic Mucosal Resection; LGD: Low Grade Dysplasia; HGD: High Grade Dysplasia; EAC: Esophageal Adenocarcinoma

Secondary outcome: Complications

Complication rates did not significantly differ between the treatment groups. Clinically relevant bleeding occurred in 2 cases each in both treatment groups (cEMR: 0.4%; ESD: 2.5%; p = 0.11). There were no perforations in either group. Strictures occurred in 17 cEMR patients (3.8%) and in 4 ESD patients (5.9%), but this difference also was not statistically significant (p = 0.50).

A Priori Sensitivity Analyses

We assessed histological outcomes between patients receiving piecemeal cEMR (greater than 1 resection specimen per procedure) and those receiving en bloc ESD. Of the cEMR patients, 266 underwent piecemeal cEMR. The average size (SD) of cEMR lesions undergoing piecemeal resection was 21.8 (10.3) mm, compared to 23.9 (9.6) mm in the ESD treatment group. The mean (SD) number of specimens resected in the piecemeal EMR group was 3.4 (1.8). ESD was associated with a significantly higher probability of achieving CRD compared to piecemeal cEMR on univariate and multivariate analysis (multivariate HR: 2.23, 95% CI 1.55–3.21; p < 0.01). However, there was no significant difference in achieving CRIM between ESD and piecemeal cEMR (HR: 1.37, 95% CI 0.66–1.79; p = 0.30). Within the cEMR group, piecemeal resection was associated with a higher probability of CRIM (HR: 1.34, 95% CI 1.08–1.66; p <0.01) and CRD (HR: 1.24, 95% CI 1.02–1.51; p = 0.04).

Discussion

We analyzed a comprehensive, prospectively maintained database of all patients at our institution receiving endoscopic treatment of dysplastic BE or early stage EAC with cEMR versus ESD followed by endoscopic ablation. The vast majority of procedures were performed by two endoscopists experienced in BE endotherapy. We demonstrate that CRD was achieved in a higher proportion of patients receiving ESD compared to cEMR at 2 years. However, the odds of patients achieving CRIM were similar at two years after initial resection. While, we did observe that histological outcomes improved over time in the cEMR group, potentially due to improvements in cEMR or ablation techniques, the difference in histological outcomes between the two groups persisted in patients treated after 2015.

The solitary study to date that evaluated comparative histological outcomes of ESD with cEMR was a small randomized trial of 40 patients. The primary outcome was R0 resection, with a secondary outcome of complete remission of neoplasia (defined as absence of HGD or EAC on at least one follow up endoscopy) at 3 months.10 Rates of neoplasia remission were similar between the groups. CRD and CRIM rates were not reported. Our results substantially extend these findings. In addition to longer follow up, our more stringent criteria for CRD, may explain why our CRD and CRIM rates are lower than the neoplasia remission rates reported by Terheggen et al.

Another observation from our study is the higher rate of CRD in the ESD group with a comparable rate of CRIM between the two groups following ablation after resection. Lower rates of CRIM compared to CRD have been observed in many endoscopic eradication therapy trials and likely reflect the persistence of non-dysplastic BE epithelium after the eradication of dysplasia and the longer time taken to achieve CRIM.16,17 Faster progression to CRD in the ESD group may reflect that larger resected specimens leave less residual flat BE mucosa to be treated. On multivariate analysis, as the length of BE increased, the likelihood of CRD decreased, which is consistent with this line of reasoning. Supporting this theory, our study demonstrated that rates of CRD were higher in the ESD group compared to the piecemeal EMR group as well, as the latter group may not remove as much residual BE as the ESD group. In a recent study, we have demonstrated that the goal of endoscopic therapy for dysplastic BE should be CRIM given the higher risk of recurrence after achieving only CRD.18

Our other outcomes (CRIM rates and complication rates) are consistent with findings reported in the literature.8 A recent meta-analysis incorporating 5 studies suggested that outcomes for management of early esophageal cancer between multiband mucosectomy and cEMR were similar in regards to resection and complication rates, mirroring our results.19

Compared to cEMR, ESD is a newer technique, and hence follow up time after ESD is relatively short to robustly assess recurrence outcomes. Approximately 10% of patients in the ESD group and 7% in the cEMR group received cryotherapy, which may indicate more resistant disease, as cryotherapy was typically utilized in our practice in situations where RFA was unable to induce CRIM. As such, our results likely include patients with more severe disease than may be found in the general population. Another limitation of our study is the lack of randomization.

Propensity score matching was considered, but given the clear confounding due to the time (as ESD was performed only after 2015) in choosing which resection technique was utilized, this was not performed. However, our results are unlikely to be due to time period differences as the two groups otherwise appeared similar in regards to patient demographics and procedures were performed in both groups by the same endoscopists with extensive experience in endoscopic therapy. Additionally, our institution’s database of EET procedures is prospectively maintained and consistently updated, and our ability to examine patient charts allowed us to abstract in granular detail a variety of important variables that affect clinical management of these patients. While cEMR has a current procedural terminology code for reimbursement, no specific code exists as of yet for ESD. There are greater capital expenses associated with ESD including specialized equipment and dedicated training, as well as longer procedural times and duration of anesthesia.20 As such, ESD has not been as widely adopted as cEMR. However, economic analyses have demonstrated ESD is still more cost effective compared to surgery, which may be the alternative if ESD is not available at an institution.21

In conclusion, we report that in the management of dysplastic BE with cEMR and ESD followed by endoscopic ablation, while CRD is achieved earlier and in a higher proportion of patients with ESD. CRIM rates appear to be similar between the two groups. In expert hands both sets of procedures appear to be safe and well tolerated. Continued monitoring for additional outcomes such as recurrence, are required for further elucidation of the optimal role of these procedures in the management of BE neoplasia.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1: Kaplan-Meier curve for achieving complete remission of dysplasia in subset of patients treated from 2015–2020. The odds of CRD remained lower for cEMR than for ESD (HR: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.45–0.99).

Supplementary Figure 2: Kaplan-Meier curve for achieving complete remission of intestinal metaplasia in subset of patients treated from 2015–2020. The odds of CRIM were not statistically significant between the treatment modalities (HR: 0.88; 95% CI: 0.54–1.43).

What you need to know:

Background

Cap-assisted endoscopic mucosal resection (cEMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) are utilized in the treatment of Barrett’s neoplasia. Long term comparative outcomes are uncertain.

Findings

A review of patients at our institution undergoing cEMR vs. ESD for management of Barrett’s neoplasia demonstrated higher rates of clinical remission of dysplasia (CRD) for ESD patients, but no difference in clinical remission of intestinal metaplasia (CRIM) at 2 years, even after adjustment for confounding variables in a multivariate model. Complication rates were similar between the two treatment groups.

Implications for Patient Care

cEMR and ESD followed by ablation appear to be equally effective in the management of Barrett’s neoplasia, though ESD leads to CRD faster and may be preferable in larger lesions given the ability to assess lateral margins. Long term recurrence outcomes in the two strategies need to be studied.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Supported in part by NCI grant (CA 241162) to PGI and the Freeman Foundation

Disclosures:

DC Codipilly: None

L Dhaliwal: None

M Oberoi: None

P Gandhi: None

ML Johnson: None

RM Lansing: None

WS Harmsen: None

KK Wang: Research funding: Fuji Medical, Erbe

PG Iyer: Research funding: Exact Sciences

Abbreviations

- BE

Barrett’s Esophagus

- EAC

Esophageal Adenocarcinoma

- NDBE

Non-Dysplastic Barrett’s Esophagus

- LGD

Low Grade Dysplasia

- HGD

High Grade Dysplasia

- cEMR

Cap-Assisted Endoscopic Mucosal Resection

- ESD

Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection

- CRIM

Complete Remission of Intestinal Metaplasia

- CRD

Complete Remission of Dysplasia

- EGD

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy

- IQR

Interquartile Range

- SD

Standard Deviation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics,2019. CA Cancer J Clin 2019;69:7–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krishnamoorthi R, Singh S, Ragunathan K, et al. Risk of recurrence of Barrett’s esophagus after successful endoscopic therapy. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;83: 1090–1106.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Namasivayam V, Wang KK, Prasad GA. Endoscopic Mucosal Resection in the Management of Esophageal Neoplasia: Current Status and Future Directions. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2010;8:743–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wani S, Mathur SC, Curvers WL, et al. Greater Interobserver Agreement by Endoscopic Mucosal Resection Than Biopsy Samples in Barrett’s Dysplasia. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2010;8:783–788.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prasad GA, Buttar NS, Wongkeesong LM, et al. Significance of neoplastic involvement of margins obtained by endoscopic mucosal resection in Barrett’s esophagus. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2007;102:2380–2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Podboy A, Kolahi KS, Friedland S, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection is associated with less pathologic uncertainty than endoscopic mucosal resection in diagnosing and staging Barrett’s-related neoplasia. Dig Endosc 2020;32:346–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang KK, Prasad G, Tian J. Endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection in esophageal and gastric cancers. Current opinion in gastroenterology 2010;26:453–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang D, Zou F, Xiong S, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early Barrett’s neoplasia: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2018;87:1383–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu X, Chen J, Yuan Z, et al. Endoscopic resection techniques for squamous premalignant lesions and early carcinoma of the esophagus: ER-Cap, MBM, and ESD, how do we choose? A multicenter experience. Therapeutic advances in gastroenterology 2020;13:1756284820909172–1756284820909172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terheggen G, Horn EM, Vieth M, et al. A randomised trial of endoscopic submucosal dissection versus endoscopic mucosal resection for early Barrett’s neoplasia. Gut 2017;66:783–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sawas T, Visrodia KH, Zakko L, et al. Clutch cutter is a safe device for performing endoscopic submucosal dissection of superficial esophageal neoplasms: a western experience. Diseases of the Esophagus 2018;31(11). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Genere JR, Priyan H, Sawas T, et al. Safety and histologic outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection with a novel articulating knife for esophageal neoplasia. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 2020;91:797–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sami SS, Ravindran A, Kahn A, et al. Timeline and location of recurrence following successful ablation in Barrett’s oesophagus: an international multicentre study. Gut 2019;68:1379–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Visrodia K, Zakko L, Singh S, et al. Cryotherapy for persistent Barrett’s esophagus after radiofrequency ablation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2018;87:1396–1404.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levine DS, Haggitt RC, Blount PL, et al. An endoscopic biopsy protocol can differentiate high-grade dysplasia from early adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology 1993;105:40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaheen NJ, Sharma P, Overholt BF, et al. Radiofrequency ablation in Barrett’s esophagus with dysplasia. New England Journal of Medicine 2009;360:2277–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phoa KN, Pouw RE, Bisschops R, et al. Multimodality endoscopic eradication for neoplastic Barrett oesophagus: results of an European multicentre study (EURO-II). Gut 2016;65:555–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sawas T, Alsawas M, Bazerbachi F, et al. Persistent intestinal metaplasia after endoscopic eradication therapy of neoplastic Barrett’s esophagus increases the risk of dysplasia recurrence: meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2019;89:913–925.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dan X, Lv XH, San ZJ, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Multiband Mucosectomy Versus Cap-assisted Endoscopic Resection For Early Esophageal Cancer and Precancerous Lesions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2019;29:313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schlachterman A, Yang D, Goddard A, et al. Perspectives on endoscopic submucosal dissection training in the United States: a survey analysis. Endoscopy international open 2018;6:E399–E409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dahan M, Pauliat E, Liva-Yonnet S, et al. What is the cost of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD)? A medico-economic study. United European gastroenterology journal 2019;7:138–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Kaplan-Meier curve for achieving complete remission of dysplasia in subset of patients treated from 2015–2020. The odds of CRD remained lower for cEMR than for ESD (HR: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.45–0.99).

Supplementary Figure 2: Kaplan-Meier curve for achieving complete remission of intestinal metaplasia in subset of patients treated from 2015–2020. The odds of CRIM were not statistically significant between the treatment modalities (HR: 0.88; 95% CI: 0.54–1.43).