Abstract

Background.

Health literacy has yet to be described in a non-clinical, racially diverse, community-based cohort.

Methods.

Four questions assessing health literacy were asked during annual phone encounters with Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) participants between 2016 and 2018 (n=3629). We used prevalence ratios (PRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to characterize how demographic and acculturation factors related to limited health literacy. Models adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity, and race/ethnicity-stratified models were also examined.

Results.

Limited health literacy was prevalent in 15.4% of the sample. Participants who were older, female, lower-income, or less acculturated were at greater risk for having limited health literacy. Chinese, Hispanic, and Black participants were more likely than White participants to have limited health literacy. Patterns were similar when stratified by race/ethnicity.

Discussion.

Within MESA limited health literacy was common, particularly among Chinese and Hispanic participants, with some of the variance explained by differences in acculturation.

Keywords: Health literacy, acculturation, risk factors

INTRODUCTION

Health literacy has been defined as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.”[1] Limited health literacy can impact a person’s health and quality of care in numerous ways.[2,3] For instance, limited health literacy can make navigating the complex health care systems intimidating.[2,4] Individuals with limited health literacy may have difficulty filling out forms, locating providers and services, and managing health insurance.[4,5] It may also be more difficult for these individuals to share personal information with providers, such as health history, or to engage in self-care and chronic-disease management.[6,7] Related, numeracy skills are important to health literacy, as they are necessary for tasks such as calculating cholesterol and blood sugar levels, measuring medications, understanding nutrition labels, and comprehending health plan coverage and costs.[2,5] Having limited health literacy may be especially problematic in patients with complicated treatment regimens or multimorbidity.[8,9]

Educational attainment, socioeconomic status (SES), and fluency in the predominant language of the healthcare system contribute to the health literacy of an individual.[10] The dynamic relationship between these factors determines how an individual effectively processes information related to health.[10] Existing literature has suggested that immigrants and those who are less acculturated may have more limited health literacy.[10–12]

Within the context of CVD, existing research has consistently suggested that limited health literacy acts as a barrier to optimal health care and health behaviors, and is associated with adverse cardiovascular health behaviors, such as not meeting blood pressure recommendations in those with hypertension.2,4 Limited health literacy has also been associated with poorer health outcomes and increased health care utilization.[13] In a retrospective study of insured patients with heart failure, those with lower health literacy had a higher rate of overall mortality as well as a higher rate of hospitalization, compared to patients with adequate health literacy.[14] Better health may be achieved when individuals have an understanding of their health conditions and maintain a beneficial relationship with health care providers.[2,14–16]

In order to successfully address limited health literacy, it is critical to understand which groups of patients are most likely to have limited health literacy. In the present study we used cross-sectional data from the diverse and community-based Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), to describe associations of demographic and socioeconomic factors with health literacy. Specifically, we document the prevalence of limited health literacy by age categories, sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, place of birth, generation in the United States, and language spoken in the home. We also examine whether the prevalence of limited health literacy differs by race/ethnicity.

METHODS

a. Participants

The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA)[17] cohort recruited 6,814 participants aged 45–85 years old who were free of clinical cardiovascular disease between 2000 and 2002 from six US communities: Chicago, Illinois; Los Angeles County, California; New York, New York; Forsyth County, North Carolina; St Paul, Minnesota; and Baltimore, Maryland. IRB approval was obtained by all participating institutions, and participants gave written informed consent. Only individuals who communicated in English, Spanish, Cantonese or Mandarin were eligible to enroll in the study. All participant-facing study materials were translated from English into the other languages, with back-translation to verify accuracy of translation. Also, study data collection staff teams included individuals who spoke the preferred languages of participants recruited at the site.

Race/ethnicity at baseline was self-reported, and participants identified as White (38%), Black (28%), Hispanic (22%), or Chinese (12%). Since baseline, participants have taken part in 5 additional clinical exams and over 20 follow-up phone calls. Questions on health literacy were asked during follow-up phone calls 18 and 19, which took place between 2016 and 2018. A total 4,045 participants answered the questions on health literacy. For the present analysis, conducted in 2019, we excluded participants who were missing responses for the health literacy questions or other demographic information, yielding an analytic sample of 3,628 participants.

b. Measures

i. Demographic, Socioeconomic Status, and Acculturation Definitions

During the first exam of MESA, a questionnaire obtained information on demographics, socioeconomic status, and acculturation.

Income and education were used as indicators of SES. Income was assessed at exam 5 from 13 categories, and was a priori divided into the following tertiles: less than $20 000, $20 000 to $49 000, and $50 000 or more. Education was assessed at exam 1, where participants were asked to select the highest level of education they had completed from eight categories. The categories used in analysis were defined as less than high school diploma, high school diploma or some college, or college degree or more.

Acculturation is defined as “the process whereby an immigrant culture adopts the beliefs and practices of a host culture.”[18] Proxies of acculturation, such as language spoken in the home, nativity, and generation in the United States, were assessed during exam one. Language spoken in the home was categorized as dichotomous for English or other. Nativity, or place of birth, was categorized dichotomously as being born within the United States or elsewhere. As has been done with previous MESA studies[19], we characterized number of generations in the United States by those not born in the United States as generation zero, those with one or two parents born in the United States as first generation, those with both parents born in the United States but two or more grandparents not born in the United States were classified as second generation, and those with both parents born in the United States and three or more grandparents born in the United States were classified as third generation.

ii. Health Literacy

Health literacy was assessed with four questions during an annual follow-up phone call shortly after MESA Exam 6, in the language preferred by the participant (English, Spanish, Cantonese, or Mandarin). The full questions and response options are provided in Table 1. Three of the four questions have previously been validated as having high internal consistency in measuring health literacy,[20] but the research team included a question on numeracy to obtain a more holistic profile on health literacy.[21] To determine whether a summed unidimensional health literacy scale could be used including the fourth question, we evaluated whether the four questions were measuring a single construct by 1) viewing item-to-total correlations and 2) calculating Cronbach’s Alpha, which is a measure of consistency among individual items. Based on the high Cronbach’s Alpha (α = 0.93), the four questions were combined to create a scale of health literacy.

Table 1.

Health Literacy Questions, Scoring and Distribution: Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis 2016–2018

| Question 1 - How often do you have someone help you read materials received from your doctor? [20] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Answer | Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Always |

| N (%) | 2839 (78.2) | 268 (7.4) | 240 (6.6) | 135 (3.7) | 147 (4.0) |

| Score | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Question 2 - How often do you have problems learning about your health condition because of difficulty reading materials received from your doctor? [20] | |||||

| Answer | Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Always |

| N (%) | 2854 (78.6) | 306 (8.5) | 225 (6.2) | 118 (3.2) | 126 (3.5) |

| Score | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Question 3 - How confident are you filling out medical forms by yourself? [20] | |||||

| Answer | Extremely | Quite a bit | Somewhat | A little bit | Not at all |

| N (%) | 2637 (72.7) | 446 (12.3) | 255 (7.0) | 126 (3.5) | 165 (4.5) |

| Score | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Question 4 - In general, how easy or hard do you find it to understand medical statistics? 21 | |||||

| Answer | Very easy | Easy | Hard | Very Hard | |

| N (%) | 1749 (48.2) | 1327 (36.6) | 399 (11.0) | 154 (4.2) | |

| Score | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

Scores for the individual items (shown in Table 1) were summed. We explored continuous, ordinal and dichotomous representations. A standardized definition of low health literacy does not yet exist, based on these questions. However, as has been done previously,[14] for the primary analysis we dichotomized health literacy as adequate (score >10) or limited (score ≤10). There was not psychometric validation of the health literacy scale.

c. Statistical Analysis

Crude prevalences of health literacy categories were calculated. We then calculated prevalence ratios (and their 95% confidence intervals) using relative risk regression (binomial regression with a log link). Models were minimally adjusted, for demographic factors (e.g. when race/ethnicity was the primary exposure, the models were adjusted for age and sex). Analyses of acculturation factors were conducted overall, and stratified by race-ethnicity, given that prior studies have suggested to prevalence of health literacy may vary by race/ethnicity. Due to small cell sizes, stratified results are not presented for some combinations of acculturation and race/ethnicity. All analyses were completed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). MESA data are available to qualified Investigators on the Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center (BioLINCC) website, sponsored by the NIH National, Heart, Lung and Blood Institute: https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/home/.

RESULTS

The sample consisted of 3,629 adults ages 53–94 years (median=69). Of the participants included in the analysis 41.6% were White, 12.5% were Chinese, 25.6% were Black, and 20.2% were Hispanic. Table 1 provides of the distribution of responses for each health literacy question. The health literacy questions were scored and combined, and the mean health literacy score was 6.3, with a range of 4 to 20, and the 25th and 75th percentiles being 4.0 and 7.0, respectively. Limited health literacy (i.e., score of ≤ 10)[20] was prevalent in 15.4% (n = 560) of the sample.

When we looked specifically among females who were ≥70 the prevalence of low health literacy was 24.6% whereas among females <70 it was 10.6%. Among females ≥70, 18.6% had less than a high school diploma, 50.6% completed high school or had some college, and 30.8% has a college degree. In comparison, among males ≥70 the prevalence of low health literacy was 20.3%, and among males <70 it was 8.6%. In terms of educational attainment 12.9% had not completed high school, 41.3% had a high school diploma or some college, and 45.9% had a college degree.

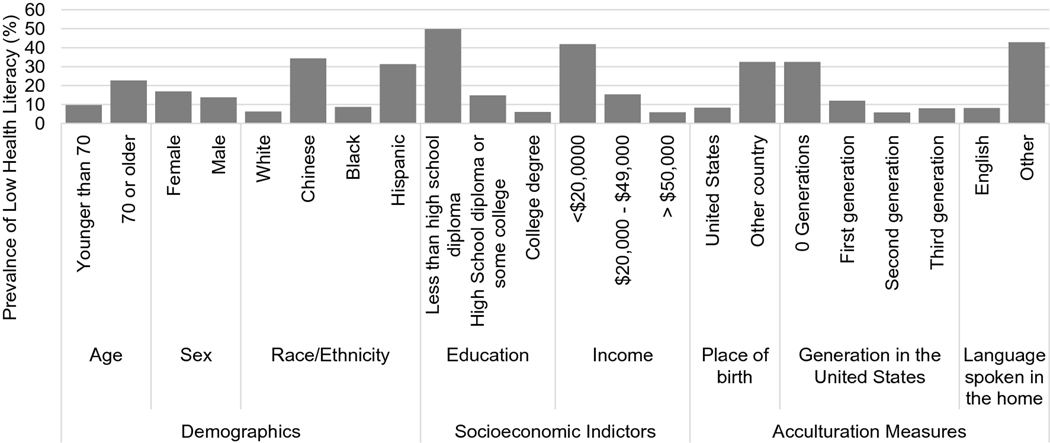

Associations between various demographic and acculturation factors with health literacy are reported in Table 2 and Figure 1. Limited health literacy was more common among participants who were older [prevalence: ≥70 years (22.7%), <70 years (9.7%), PR (95% CI): 2.35 (2.00, 2.76)], female [prevalence: female (16.9%), male (13.7%) PR: 1.23 (1.06, 1.44)], had less education [prevalence: less than high school (49.8%), high school diploma or some college (14.7%), college degree (6.0%), PR: 8.33 (6.68, 10.40)], and had lower income [prevalence: <$20 000 (41.8%), between $20 000 and $49 000 (15.3%), > $50 000 (5.9%), PR:7.06 (5.71, 8.72)]. When we looked specifically among female who were ≥70 the prevalence of low health literacy was 24.6% whereas among female <70 it was 10.6%. Among female ≥70, 18.6% had less than a high school diploma, 50.6% completed high school or had some college, and 30.8% has a college degree. In comparison, among men ≥70 the prevalence of low health literacy was 20.3%, and among men <70 it was 8.6%. In terms of educational attainment 12.9% had not completed high school, 41.3% had a high school diploma or some college, and 45.9% had a college degree.

Table 2.

Crude and adjusted associations of demographic, socioeconomic and acculturative characteristics with health literacy: MESA, 2000–2018

| Health Literacy | Prevalence ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted Prevalence ratio (95% CI) a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Adequate | ||||||

| n (%) | n (%) | ||||||

| total n | 560 (15.4) | 3069 (84.6) | |||||

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age | |||||||

| < 70 | 195 (9.7) | 1824 (90.3) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | |||

| ≥ 70 | 365 (22.7) | 1245 (77.3) | 2.35 (2.00, 2.76) | 2.24 (1.93, 2.61) | |||

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 331 (16.9) | 1626 (83.1) | 1.23 (1.06, 1.44) | 1.23 (1.07, 1.42) | |||

| Male | 229 (13.7) | 1443 (86.3) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 95 (6.3) | 1416 (93.7) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | |||

| Chinese | 156 (34.3) | 299 (65.7) | 5.45 (4.32, 6.88) | 5.21 (4.15, 6.55) | |||

| Black | 80 (8.6) | 849 (91.4) | 1.37 (1.03, 1.82) | 1.36 (1.02, 1.80) | |||

| Hispanic | 229 (31.2) | 505 (68.8) | 4.96 (3.97, 6.20) | 4.93 (3.96, 6.14) | |||

| Socioeconomic Indictors | |||||||

| Education | |||||||

| Less than high school diploma | 223 (49.8) | 225 (50.2) | 8.33 (6.68, 10.40) | 3.88 (3.06, 4.95) | |||

| High School diploma or some college | 248 (14.7) | 1443 (85.3) | 2.46 (1.95, 3.10) | 2.02 (1.60, 1.55) | |||

| College degree | 89 (6.0) | 1401 (94.0) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | |||

| Income | |||||||

| <$20,0000 | 255 (41.8) | 355 (58.2) | 7.06 (5.71, 8.72) | 3.55 (2.81, 4.95) | |||

| $20,000 - $49,000 | 182 (15.3) | 1004 (84.7) | 2.59 (2.05, 3.27) | 1.93 (1.53, 2.44) | |||

| ≥ $50,000 | 101 (5.9) | 1604 (94.1) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | |||

| Acculturation Measures | |||||||

| Place of birth | |||||||

| United States | 209 (8.2) | 2336 (91.8) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | |||

| Other country | 351 (32.4) | 733 (67.6) | 3.94 (3.37, 4.61) | 1.97 (1.61, 2.43) | |||

| Generation in the United States | |||||||

| 0 Generations | 351 (32.4) | 733 (67.6) | 4.10 (3.40, 4.94) | 1.60 (1.19, 2.16) | |||

| First generation | 54 (12.0) | 398 (88.0) | 1.51 (1.12, 2.04) | 0.76 (0.54, 1.08) | |||

| Second generation | 28 (5.8) | 458 (94.2) | 0.73 (0.49, 1.08) | 0.66, (0.44, 1.00) | |||

| Third generation | 127 (7.9) | 1480 (92.1) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | |||

| Language spoken in the home | |||||||

| English | 232 (8.1) | 2631 (91.9) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.00 (Ref) | |||

| Other | 328 (42.8) | 438 (57.2) | 5.28 (4.56, 6.13) | 3.15 (2.53, 3.94) | |||

= Adjusted for age, sex, and race

Figure 1.

Prevalence of low health literacy by participant characteristics: Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis 2000–2018

A higher prevalence of limited health literacy was observed among participants who were Chinese [PR (95% CI): 5.45 (4.32, 6.88)], Hispanic [PR (95% CI): 4.96 (3.97, 6.20)], and Black [PR (95% CI): 1.37 (1.03, 1.82], relative to White participants. After adjusting for age, sex, and race/ethnicity the associations between acculturation and health literacy were attenuated.

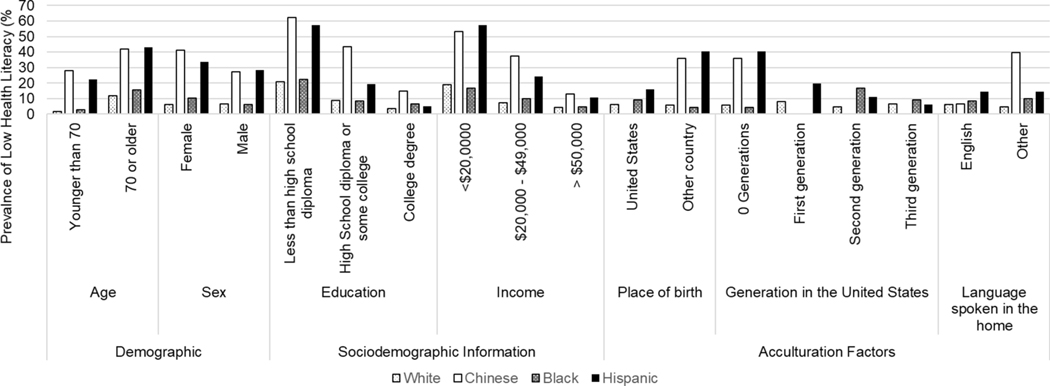

Unadjusted prevalence ratios stratified by race/ethnicity are found within Table 3. Patterns of health literacy with age, income and most acculturation factors were similar to findings from the full study sample. As compared to their male counterparts, Chinese and Black females were more likely to be categorized as having limited health literacy [1.49 (1.15, 1.95), 1.68 (1.07, 2.67), respectively]. Yet among Hispanic participants, females were less likely than men to have limited health literacy in Hispanic participants [1.18 (0.95, 1.47)], whereas among white participants there was no significant difference between males and females [0.90 (0.61, 1.32)]. Race/ethnicity-stratified health literacy associations according to acculturative factors are also shown in Table 3 and select associations are presented in Figure 2. In general individuals who were less accultured to the U.S. were more likely to have limited health literacy.

Table 3.

Crude associations of demographic, socioeconomic and acculturative characteristics with health literacy: MESA, 2000–2018

| White (n = 1514) | Chinese (n=445) | Black (n=929) | Hispanic (n=734) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Literacy | Health Literacy | Health Literacy | Health Literacy | |||||||||

| Low | Adequate | Prevalence ratio | Low | Adequate | Prevalence ratio | Low | Adequate | Prevalence ratio | Low | Adequate | Prevalence ratio | |

| n (%) | n (%) | (95% CI) | n (%) | n (%) | (95% CI) | n (%) | n (%) | (95% CI) | n (%) | n (%) | (95% CI) | |

| total n | 95 (6.3) | 1416 (93.7) | 156 (34.3) | 299 (65.7) | 80 (8.6) | 849 (91.4) | 229 (31.2) | 505 (68.8) | ||||

| Demographics | ||||||||||||

| Age | ||||||||||||

| < 70 | 14 (1.7) | 816 (98.3) | 1.00 (Ref) | 70 (28.0) | 180 (72.0) | 1.00 (Ref) | 15 (2.9) | 498 (97.1) | 1.00 (Ref) | 96 (22.5) | 330 (77.5) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| ≥ 70 | 81 (11.9) | 600 (88.1) | 7.05 (4.03, 12.32) | 86 (42.0) | 119 (58.0) | 1.50 (1.16, 1.94) | 65 (15.6) | 351 (84.4) | 5.34 (3.09, 9.23) | 133 (43.2) | 175 (56.8) | 1.92 (1.54, 2.38) |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | 47 (6.0) | 742 (94.0) | 0.90 (0.61, 1.32) | 94 (41.1) | 135 (58.9) | 1.49 (1.15, 1.95) | 56 (10.4) | 483 (89.6) | 1.68 (1.07, 2.67) | 134 (33.5) | 266 (66.5) | 1.18 (0.95, 1.47) |

| Male | 48 (6.6) | 674 (93.4) | 1.00 (Ref) | 62 (27.4) | 164 (72.6) | 1.00 (Ref) | 24 (6.1) | 366 (93.9) | 1.00 (Ref) | 95 (28.4) | 239 (71.6) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Socioeconomic Indictors | ||||||||||||

| Education | ||||||||||||

| Less than HS | 9 (20.9) | 34 (79.1) | 5.72 (2.91, 11.25) | 51 (62.2) | 31 (37.8) | 4.17 (2.88, 6.04) | 14 (22.2) | 49 (77.8) | 3.34 (1.83, 6.11) | 149 (57.3) | 111 (42.7) | 11.46 (4.38, 29.96) |

| HS diploma or some college | 55 (8.9) | 585 (91.1) | 2.43 (1.58, 3.72) | 75 (43.6) | 97 (56.4) | 2.92 (2.02, 4.23) | 42 (8.3) | 463 (91.7) | 1.25 (0.77, 2.03) | 76 (19.3) | 318 (80.7) | 3.86 (1.45, 10.24) |

| College degree | 31 (3.7) | 817 (96.3) | 1.00 (Ref) | 30 (14.9) | 171 (85.1) | 1.00 (Ref) | 24 (6.7) | 337 (93.3) | 1.00 (Ref) | 4 (5.0) | 76 (95.0) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Income | ||||||||||||

| <$20,0000 | 19 (18.8) | 82 (81.2) | 4.42 (2.67, 7.33) | 86 (53.1) | 76 (46.9) | 4.10 (2.68, 6.26) | 20 (16.7) | 100 (8.3) | 3.55 (1.96, 6.43) | 130 (57.3) | 97 (42.7) | 5.40 (3.55, 8.22) |

| $20,000 - $49,000 | 29 (7.2) | 373 (92.8) | 1.69 (1.07, 2.69) | 47 (37.3) | 79 (62.7) | 2.9 (1.8, 4.6) | 36 (9.8) | 333 (90.2) | 2.08 (1.21, 3.56) | 70 (24.2) | 219 (75.8) | 2.28 (1.45, 3.59) |

| ≥ $50,000 | 40 (4.3) | 900 (95.7) | 1.00 (Ref) | 21 (13.0) | 141 (87.0) | 1.00 (Ref) | 19 (4.7) | 386 (95.3) | 1.00 (Ref) | 21 (10.6) | 177 (89.4) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Acculturation Measures | ||||||||||||

| Place of birth | ||||||||||||

| United States | 89 (6.3) | 1320 (93.7) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.00 (0.00) | 21 (100) | N/A | 76 (9.1) | 763 (90.9) | 1.00 (Ref) | 44 (15.9) | 232 (84.1) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Other country | 6 (5.9) | 96 (94.1) | 0.93 (0.42, 2.08) | 156 (35.9) | 278 (64.1) | N/A | 4 (4.4) | 86 (95.6) | 0.49 (0.18, 1.31) | 185 (40.4) | 273 (56.6) | 2.53 (1.89, 3.40) |

| Gen. in the United States | ||||||||||||

| 0 Generations | 6 (5.9) | 96 (94.1) | 0.88 (0.40, 2.01) | 156 (35.9) | 278 (64.1) | N/A | 4 (4.4) | 86 (95.6) | 0.49 (0.18, 1.30) | 185 (40.4) | 273 (59.6) | 4.24 (2.33, 7.73) |

| First generation | 20 (8.2) | 223 (91.8) | 1.24 (0.75, 2.03) | 0 | 19 (100) | N/A | 0 | 19 (100) | N/A | 34 (19.9) | 137 (80.1) | 2.09 (1.08 4.05) |

| Second generation | 18 (4.5) | 382 (95.5) | 0.68 (0.40, 1.14) | 0 | 2 (100 | N/A | 2 (16.7) | 10 (83.3) | 1.82 (0.50, 6.57) | 8 (11.1) | 64 (88.9) | 1.00 (Ref) a |

| Third generation | 51 (6.6) | 715 (93.4) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0 | 0 | N/A | 74 (9.2) | 734 (90.8) | 1.00 (Ref) | 2 (6.1) | 31 (93.9) | |

| Lang. spoken in the home | ||||||||||||

| English | 94 (6.3) | 1396 (93.7) | 1.00 (Ref) | 5 (6.7) | 70 (93.3) | 1.00 (Ref) | 79 (8.6) | 840 (91.4) | 1.00 (Ref) | 54 (14.3) | 325 (85.7) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Other | 1 (4.8) | 20 (95.2) | 0.75 (0.11, 5.16) | 151 (39.7) | 229 (60.3) | 5.96 (2.53, 14.03) | 1 (10.0) | 9 (90.0) | 1.16 (0.18, 7.56) | 175 (14.3) | 180 (50.7) | 3.46 (2.64, 4.53) |

= To accommodate for some of the small sample sizes of the groups, the second and third generation of Hispanic’s were combined to create the reference group in determining the association of health literacy with generation in the United States.

Figure 2.

Race/ethnicity-stratified prevalence of low health literacy by participant characteristics: Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis 2000–2018

DISCUSSION

In the diverse and population-based MESA sample, about 1 in 7 participants (15.4%) were classified as having limited health literacy. Elderly persons, females, and those with less income were more likely to be categorized as having limited health literacy, relative to those who were comparatively younger, male, and had greater income, respectively. Chinese, Black, and Hispanic participants were more likely to report limited health literacy compared to White participants. Acculturation factors such as being born outside of the United States, fewer generations lived in the United States, and language other than English spoken in the home were all also associated with limited health literacy after adjustment for age, sex, and race.

Health literacy is often thought of as a product of your education but is more appropriately be described as “a product of larger societal structures.”[22] Prior work has shown that education is highly correlated with level of health literacy, benefitting those with more education.[2–4,11–16,23–25] In MESA we also observed a correlation between health literacy and education, overall and when stratified by race-ethnicity. Furthermore, when we stratified by sex we found that we observed that older females had more limited health literacy, and correspondingly lower general educational attainment. The participants of MESA were born in the 1910’s to 1960’s. Presumably, due to their identity (or intersectional identities), many participants within MESA did not have access to a high quality education. The relatively high prevalence of low health literacy among groups that may have had less access to quality education, based on their race/color, sex, or national origin underscores the importance studying social and generational impacts on health literacy.[2]

Putting our results into context, the prevalence of limited health literacy in MESA is similar to that reported in the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) among non-Hispanic whites (NAAL: 9%, and MESA: 6.3%) and white Hispanic adults (NAAL: 41%, and MESA: 31.2%).[3] It is important to note that health literacy within NAAL was assessed in a non-clinical population through 28 health-related tasks, which differs from the 4 subjective health literacy questions used in MESA.[3] However, the prevalence of limited health literacy differed among non-Hispanic Blacks across the two samples (NAAL: 24%, MESA: 8.6%).[3] The prevalence of limited health literacy for Chinese participants from MESA (34.3%) also differs from the prevalence of limited health literacy in Asian/Pacific Islanders in NAAL (13%).[3] Many cross-sectional studies have examined the prevalence of limited health literacy in clinical cohorts (e.g. diabetes, heart failure, hypertension, etc) and found similar estimates.[26] Findings for acculturation were consistent with previous studies which reported that in Hispanics lower acculturation was associated with more limited health literacy.[3,11,12,23,27] Previous studies of acculturation and health literacy in Hispanics had smaller sample sizes or were limited to clinical populations. The association of health literacy and acculturation has not been thoroughly studied among Chinese immigrants,[24] but one non-clinical sample of Chinese Americans from California found that those with limited health literacy and limited English proficiency were less likely to meet cancer screening guidelines.[28] As of this publication, the association of health literacy and acculturation has not been studied within a non-clinical sample of Black or White immigrants within the United States.

This study has a number of strengths. MESA provides a unique opportunity to analyze health literacy data in a non-clinical sample from 6 communities which includes representation from four major racial and ethnic categories and is not limited to those who speak English. Though many health literacy measures exist in multiple languages, or have been validated in other languages, a majority of the health literacy research studies exclude those who do not speak English or Spanish.[29,30] Herein we included native Mandarin and Cantonese speakers. In addition, many prior health literacy studies within the United States have been conducted within one race or ethnic category, or dichotomize the racial/ethnic categories to black and white.[11,12,25,28,31–33] Another strength of this study is assessment of acculturation factors in the MESA cohort. Including acculturation factors within our assessment of health literacy provides information about the experience and barriers for immigrants who are attempting to navigate and comprehend health-related information in the US. Our findings were consistent with previous studies demonstrating that those with lower acculturation also reported lower health literacy.[3,11,12]

There are some limitations that should be considered when interpreting our results. First, our results are cross-sectional in nature and thus causation cannot be inferred from our results. However, from a public health perspective, our findings are useful for documenting the burden of limited health literacy among Americans. Second, health literacy was assessed based on responses to 4 subjective questions. A multitude of health literacy measures exist, including some which objectively assess health knowledge.[7,34] Future research should consider the importance of multidimensional health literacy assessments.[35] Third, the health literacy questions have only been validated in English. For the purpose of this study, the validated health literacy questions were translated from English to the participant’s preferred language, and then back-translated to English to verify accuracy of translation. It is, however, possible they may not have adequate cultural and dialectic translation. Furthermore, psychometric validation in the various languages has not taken place. Fourth, cognitive function, which may also influence health literacy, was not taken into consideration with these analyses.[36] Fifth, acculturation measures for this analysis were taken at MESA Exam 1 (2000–2002), which may not accurately capture any additional acculturation after baseline. Lastly, selection bias may exist if those who take part in cohort studies are different than those who do not. Thus the results of these analyses may not be generalizable to the entire racial or ethnic group being considered.[36]

NEW CONTRIBUTION TO THE LITERATURE

There is a need to identify sustainable and scalable means to increase health-literacy across the population, and particularly among population sub-groups where health literacy is generally low. These findings provide novel information about the burden of health literacy, in a non-clinical U.S-based setting, according to demographic and acculturation factors. Results from these analyses can inform groups to target for future health literacy interventions, but more importantly highlight the importance for population based interventions to increase health literacy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32 HL07779 (Ms. Anderson). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. MESA is a National Institutes of Health (NIH) contract. The NIH was involved in the overall MESA study design and data collection. However the NIH was not involved with the analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication. The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the Minnesota Population Center (P2C HD041023) funded through a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).This research was supported by contracts HHSN268201500003I, N01-HC-95159, N01-HC-95160, N01-HC-95161, N01-HC-95162, N01-HC-95163, N01-HC-95164, N01-HC-95165, N01-HC-95166, N01-HC-95167, N01-HC-95168 and N01-HC-95169 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and by grants UL1-TR-000040, UL1-TR-001079, and UL1-TR-001420 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the MESA study for their valuable contributions.

A full list of participating MESA investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.mesanhlbi.org. No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Financial disclosure: No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper. MESA is a National Institutes of Health (NIH) contract. The NIH was involved in the overall MESA study design and data collection. However the NIH was not involved with the analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: All authors have no conflicts of interest to state.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.What is Health Literacy? | Health Literacy | CDC [Internet]. 2018. [cited 2019 Sep 28]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/learn/index.html

- 2.Magnani Jared W, Mujahid Mahasin S, Aronow Herbert D, Cené Crystal W, Vaughan Dickson Victoria, Edward Havranek, et al. Health Literacy and Cardiovascular Disease: Fundamental Relevance to Primary and Secondary Prevention: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;138:e48–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results From the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. 2003;76. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow MK. Health Literacy, Health Inequality and a Just Healthcare System. The American Journal of Bioethics. 2007;7:5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Health Literacy - Fact Sheet: Health Literacy Basics [Internet]. [cited 2019 Sep 25]. Available from: https://health.gov/communication/literacy/quickguide/factsbasic.htm

- 6.Farrell TW, Chandran R, Gramling R. Understanding the role of shame in the clinical assessment of health literacy. Fam Med. 2008;40:235–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, Pitkin K, Parikh NS, Coates W, et al. The health care experience of patients with low literacy. Arch Fam Med. 1996;5:329–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ornstein SM, Nietert PJ, Jenkins RG, Litvin CB. The Prevalence of Chronic Diseases and Multimorbidity in Primary Care Practice: A PPRNet Report. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2013;26:518–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Association of Health Literacy With Medication Knowledge, Adherence, and Adverse Drug Events Among Elderly Veterans: Journal of Health Communication: Vol 17, No sup3 [Internet]. [cited 2019 Sep 25]. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10810730.2012.712611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreps GL, Sparks L. Meeting the health literacy needs of immigrant populations. Patient Education and Counseling. 2008;71:328–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alba AD, Britigan DH, Lyden E, Johansson P. Assessing health literacy levels of Spanish-speaking Hispanic patients in Spanish at federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) in the Midwest. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2016;27:1726–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.López L, Grant RW, Marceau L, Piccolo R, McKinlay JB, Meigs JB. Association of Acculturation and Health Literacy with Prevalent Dysglycemia and Diabetes Control Among Latinos in the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. J Immigrant Minority Health. 2016;18:1266–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DK, Robinson S, Biddle MJ, Pelter MM, Nesbitt T, Southard J, et al. Health Literacy Predicts Morbidity and Mortality in Rural Patients with Heart Failure. J Card Fail. 2015;21:612–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peterson PN, Shetterly SM, Clarke CL, Bekelman DB, Chan PS, Allen LA, et al. Health Literacy and Outcomes Among Patients With Heart Failure. JAMA. 2011;305:1695–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stewart DW, Cano MÁ, Correa-Fernández V, Spears CA, Li Y, Waters AJ, et al. Lower health literacy predicts smoking relapse among racially/ethnically diverse smokers with low socioeconomic status. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Peel J, Baker DW. Health literacy and knowledge of chronic disease. Patient Education and Counseling. 2003;51:267–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, et al. Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: Objectives and Design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:871–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodriguez F, Hicks LS, López L. Association of acculturation and country of origin with self-reported hypertension and diabetes in a heterogeneous Hispanic population. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lutsey PL, Diez Roux AV, Jacobs DR, Burke GL, Harman J, Shea S, et al. Associations of Acculturation and Socioeconomic Status With Subclinical Cardiovascular Disease in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1963–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Family medicine. 2004;36:588–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woloshin S, Schwartz LM, Welch HG. Patients and medical statistics: Interest, confidence, and ability. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:996–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackert M, Mabry-Flynn A, Donovan EE, Champlin S, Pounders K. Health Literacy and Perceptions of Stigma. Journal of Health Communication. Taylor & Francis; 2019;24:856–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perez A. Acculturation, Health Literacy, and Illness Perceptions of Hypertension among Hispanic Adults. J Transcult Nurs. 2015;26:386–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li C-C, Matthews AK, Dong X. The Influence of Health Literacy and Acculturation on Cancer Screening Behaviors Among Older Chinese Americans. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine. 2018;4:233372141877819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shea JA, Beers BB, McDonald VJ, Quistberg DA, Ravenell KL, Asch DA. Assessing Health Literacy in African American and Caucasian Adults: Disparities in Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) Scores. :7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Low Health Literacy and Health Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review | Annals of Internal Medicine | American College of Physicians [Internet]. [cited 2019 Sep 25]. Available from: https://annals.org/aim/fullarticle/747040?casa_token=D6dFDoH3f-4AAAAA:tS_EuBhJqKxTP7arjuei6B_vzUH7tOKgNU5kn_UVX4VfElN0ejTIxZwq1FLw8tPqLPXp16p3Zw

- 27.Ciampa PJ, White RO, Perrin EM, Yin HS, Sanders LM, Gayle EA, et al. The association of acculturation and health literacy, numeracy and health-related skills in Spanish-speaking caregivers of young children. J Immigr Minor Health. 2013;15:492–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Low health literacy and cancer screening among Chinese Americans in California: a cross sectional analysis | BMJ Open [Internet]. [cited 2019 Sep 25]. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/5/1/e006104?int_source=trendmd&int_medium=trendmd&int_campaign=trendmd [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, Noorbaloochi S, Grill JP, Snyder A, et al. Validation of Screening Questions for Limited Health Literacy in a Large VA Outpatient Population. J GEN INTERN MED. 2008;23:561–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Health Literacy Tool Shed: A Source for Validated Health Literacy Instruments: Journal of Consumer Health on the Internet: Vol 21, No 1 [Internet]. [cited 2019 Sep 25]. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15398285.2017.1280344 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Health Literacy Explains Racial Disparities in Diabetes Medication Adherence: Journal of Health Communication: Vol 16, No sup3 [Internet]. [cited 2019 Sep 25]. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10810730.2011.604388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.James DCS, Harville C, Efunbumi O, Martin MY. Health literacy issues surrounding weight management among African American women: a mixed methods study. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics. 2014;28:41–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leung AYM, Bo A, Hsiao H-Y, Wang SS, Chi I. Health literacy issues in the care of Chinese American immigrants with diabetes: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Altin SV, Finke I, Kautz-Freimuth S, Stock S. The evolution of health literacy assessment tools: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.A New Measurement of Acculturation for Hispanics: The Bidimensional Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (BAS) - Gerardo Marin, Raymond J. Gamba, 1996. [Internet]. [cited 2019 Sep 28]. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/07399863960183002 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Livaudais-Toman J, Burke NJ, Napoles A, Kaplan CP. Health Literate Organizations: Are Clinical Trial Sites Equipped to Recruit Minority and Limited Health Literacy Patients? J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2014;7:1–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]