Abstract

Background

Despite the availability of effective pharmaceutical treatment options, many patients with asthma do not manage to control their illness. This randomized trial with a waiting-list control group examined whether a 3-week course of inpatient pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) improves asthma control (primary endpoint) and other secondary endpoints (e.g., quality of life, cardinal symptoms, mental stress). The subsequent observational segment of the study investigated the long-term outcome after PR.

Methods

After approval of the rehabilitation´ by the insurance providers (T0), 412 adults with uncontrolled asthma (Asthma Control Test [ACT] score < 20 points) undergoing rehabilitation were assigned to either the intervention group (IG) or the waiting-list control group (CG). PR commenced 1 month (T1) after randomization in the IG and 5 months after randomization (T3) in the CG. Asthma control and the secondary endpoints were assessed 3 months after PR in the IG (T3) as an intention-to-treat analysis by means of analyses of covariance. Moreover, both groups were observed for a period of 12 months after the end of PR.

Results

At T3 the mean ACT score was 15.76 points in the CG, 20.38 points in the IG. The adjusted mean difference of 4.71 points was clinically relevant (95% confidence interval [3.99; 5.43]; effect size, Cohen‘s d = 1.27). The secondary endpoints also showed clinically relevant effects in favor of the IG. A year after the end of rehabilitation the mean ACT score was 19.00 points, still clinically relevant at 3.54 points higher than when rehabilitation began. Secondary endpoints such as quality of life and cardinal symptoms (dyspnea, cough, expectoration, pain) and self-management showed moderate to large effects.

Conclusion

The trial showed that a 3-week course of PR leads to clinically relevant improvement in asthma control and secondary endpoints. Patients who do not achieve control of their asthma despite outpatient treatment therefore benefit from rehabilitation.

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) defines asthma as a heterogeneous disease characterized by chronic airway inflammation and varying symptoms, such as wheeze, shortness of breath, and cough (1). The diagnosis is based on clinical symptoms and evidence of reversible obstruction and / or bronchial hyperreactivity (2, 3).

With an estimated 300 million people affected, asthma is one of the most common chronic diseases worldwide (1). In Germany, the 12-month prevalence is 6.3% (4). Cross-sectional studies found a high number of patients with uncontrolled asthma in many countries (5, 6). Therefore, complementary approaches to improving asthma control are needed.

The current German asthma guidelines (2, 3) recommend pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) if, despite adequate outpatient medical care, the physical, psychological, or social consequences of the illness persist, or if asthma control cannot be achieved. Observational studies (7– 9) have shown positive changes in quality of life, key symptoms, physical performance, and asthma control. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have proven the effectiveness of individual components of PR, such as patient education (10), physiotherapy breathing retraining (11), and aerobic training therapy (12). To date, however, no German or international RCTs have tested the effectiveness of complex rehabilitation, which comprises different components.

The EPRA (Effectiveness of Pulmonary Rehabilitation for Patients with Asthma) study [13] combines an RCT that has a waiting list control design with a subsequent observational study. The RCT examines the effectiveness of a three-week, in-patient PR for patients with poorly controlled asthma, based on differences in the Asthma Control Test (ACT) between the intervention group (IG) and the waiting list control group (CG), at three months after rehabilitation of the IG.

Secondary outcomes are quality of life, physical performance, dyspnea, anxiety, depression, self-management skills, therapy adherence, smoking status, illness perception, subjective work ability, and subjective prognosis of gainful employment.

The subsequent observational study examined the outcomes up to twelve months after end of rehabilitation. In addition, the short-term effects on lung function parameters, 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) test, and fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) are reported before and after rehabilitation for both groups.

Methods

The study design of the single-center EPRA study has been described previously (13). The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Bavarian Chamber of Physicians (Bayerische Landesärztekammer) (Nr. 15017; 21 April, 2015). This study has been registered with the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00007740; 15 May, 2015), and was funded by the German Statutory Pension Insurance of South Bavaria (Deutsche Rentenversicherung Bayern Süd).

Study design and data collection

Between June 2015 and August 2017, all patients with asthma who were referred to the Bad Reichenhall Clinic and who met the inclusion criteria were informed by letter about the study and, if they were interested in participating, asked for their consent. At the same time, asthma control was recorded by the patients using the self-administered asthma control test (ACT).

Inclusion criteria were poorly controlled asthma (ACT < 20 points) and an asthma diagnosis confirmed by a pulmonologist at the start of rehabilitation, which was based on typical asthma symptoms as well as a documented (partially) reversible airway obstruction and bronchial hyperreactivity. Exclusion criteria were not being able to participate due to insufficient German language ability or cognitive inability, or having a serious concomitant disease.

Randomization was carried out in a 1:1 ratio for both groups in the order in which the written informed consent forms were received. A randomization list (eMethods) was stratified according to age (< 55 years, < 65 years, ≥ 65 years) and was used externally by one of the authors (M.S.).

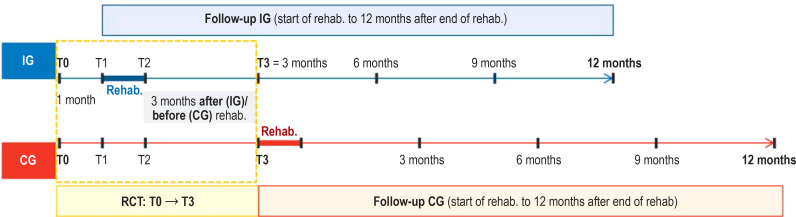

The IG started rehabilitation at one month after randomization, and the CG, at five months after randomization. Data for the RCT were collected at time of randomization (T0), and at one month (T1), two months (T2), and five months (T3) after randomization (see study design, eFigure). For the observational study, data were recorded for both groups at the start and end of rehabilitation, as well as at three, six, nine, and twelve months after the end of rehabilitation (for information about the number of cases planned and achieved, see eMethods; for further details on the study design, see eFigure).

eFigure.

Study design: The EPRA (Effectiveness of Pulmonary Rehabilitation for Patients with Asthma) study combines a randomized control group study with a waiting-list group design (T0 to T3; T0, study inclusion/ randomization; T1, start of rehabilitation for intervention group [IG]; T2, end of rehabilitation for IG;

T3, 3 months after the end of rehabilitation for IG, or start of rehabilitation for the control group [CG]), with a subsequent pooled observational study (follow-up of both study groups for up to 12 months after end of rehabilitation).

Intervention

Patients in the IG went through an intensive, three-week PR in accordance with the quality guidelines of the German statutory health insurers. The PR not only included medical diagnostics and modified drug therapy (as appropriate) but also the following mandatory (M) and optional (O) therapy components:

Endurance and strength training (M)

Whole-body vibration training (O)

Inspiratory muscle training (O)

Patient education about asthma (M)

Inhalation technique training (M)

Allergen avoidance education (O)

Group respiratory physiotherapy (M) or individual respiratory physiotherapy (O)

Buteyko breathing technique training (O)

Respiratory physiotherapeutic mucolysis procedures (O)

Psychological individual and group interventions (O)

Social counseling (O)

Nutritional counseling/therapy (O)

Smoking cessation (O)

A more detailed description can be found in the eMethods section. Note that the CG received the same interventions from T3 to T4.

Outcomes and assessment tools

Asthma control was assessed using the ACT. This questionnaire is recommended by guidelines (1– 3) and comprises a scale from 5 to 25 points, with 20 to 25 points indicating controlled asthma (1). The ACT focuses on asthma symptom control, and a score below 20 is also associated with an increased exacerbation frequency and an unfavorable asthma prognosis (“future risk”) (14, 15). Changes by three or more points are considered clinically relevant (14).

Secondary outcomes were documented with different questionnaires: health-related quality of life with the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ [S]) (16) and the St. George´s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) (17); depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (18); anxiety with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (GAD-7) (19); adherence to drug therapy with the Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS-D) (20); perceptions about the illness with the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (Brief IPQ) (21); self-management with the Skill and Technique Acquisition scale of the Health Education Impact Questionnaire (heiQ) (22); subjective work ability with the Work Ability Scale (WAS) (23); subjective prognosis of employment status with the SPE scale (24); and dyspnoea, cough, sputum, and pain with an 11-point numerical rating scale (NRS; 0–10).

At the beginning and end of rehabilitation, the following objective measured values were also collected:

Spirometry / body plethysmography with bronchodilator testing (FEV1, VC, FEV1/VC, FIV1, RV, TLC, RV/TLC, sRtot)

FeNO

6MWD test

In addition, at the start of rehabilitation, an in vitro allergy screening was carried out, and blood eosinophil count was measured.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were given for all times points. All outcomes of the RCT were evaluated using analyses of covariances. The results of each respective outcome at the corresponding time point (T2, T3) served as the outcome, while group membership (IG/CG), age group allocation, and the T0 value of the outcome were considered independent variables. All randomized patients for whom at least one measured value was available at time T0 (intention-to-treat [ITT] analysis) were included in the analysis. Missing values were handled by multiple imputation (creating ten complete datasets).

Adjusted mean differences (AMD) to T2/T3 including 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) as well as standardized effect sizes (Cohen’s d [25]) are reported. Standardized effects of > 0.2/0.5/0.8 are considered small, medium, and large, respectively. Ordinal regressions were calculated for the SPE scale, and logistic regressions, for the current smoking status. For the observational study, data were evaluated using structural equation models based on the Chi² difference test (for details, see eMethods section).

All calculations were carried out with the software programs SPSS (version 25) and R (3.61). The alpha level for the analysis of the primary outcome was set to 0.05 (eMethods).

Results

Data collection

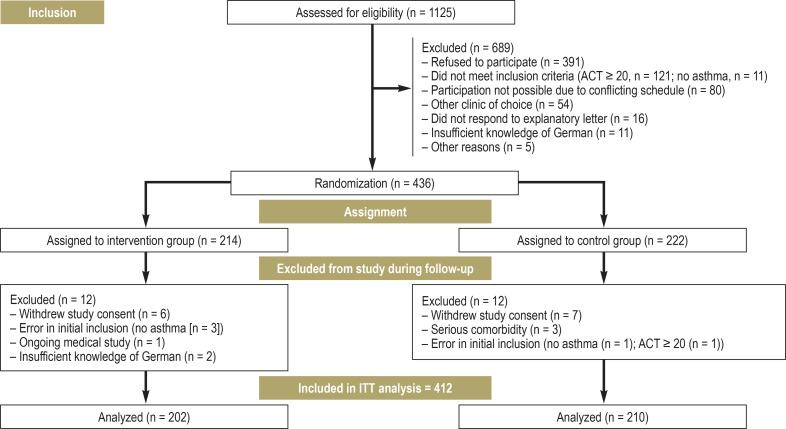

Patient recruitment is shown in Figure 1. The study included N= 412 patients, with 202 in the IG (40.1% female; Mage= 50.7 years) and 210 in the CG (43.3% female; Mage= 51.6 years). In both groups, more than 85% of patients had moderate to severe asthma (Global Initiative for Asthma [GINA] 3–5). In total, 49.4% participated in the German asthma disease management program, and 52.8% had already received patient education about asthma (table 1). In the year prior to study inclusion, 87.9% of participants had at least one exacerbation. In the three months prior to study inclusion, 35.7% had performed at least one short course of oral corticosteroids (corticosteroid tablets), and 75.0% had consulted a pulmonologist at least once. Both groups were already on intensive medication at time T0. For example, 93.6% of patients in the IG, and 92.9% of those in the CG, used an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS), mostly in combination with a long-acting beta-agonist (LABA) (ICS-LABA combination preparation used by 79.2% or 74.8% of the IG or CG patients, respectively). In the previous week, 19.3% (IG) and 12.4% (CG) of the patients had taken corticosteroid tablets (for further details on drug therapy, see eMethods, eTable 4).

Figure 1.

Trial profile: CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) flowchart

CG, control group; IG, intervention group; T0, time at randomization; T1/T2/T3, 1/3/5 months after randomization

Table 1. Description of data collection.

| IG (n = 202) | CG (n = 210) | |

| Age | 50.7 (8.8) | 51.6 (8.7) |

| Female | 81 (40.1 %) | 91 (43.3 %) |

| Pneumologist consulted*1 | 143 (70.8 %) | 166 (79.1 %) |

| General practitioner consulted*1 | 194 (90.7%) | 198 (89.2%) |

| Employment status – Full-time worker – Part-time worker – Unemployed – Pensioner/retired – Other (for ex., homemaker) |

144 (71.3 %) 39 (19.3 %) 10 (5.0 %) 2 (1 %) 8 (3.8 %) |

148 (70.5 %) 44 (21.0 %) 10 (4.8 %) 1 (0.5 %) 7 (3.3 %) |

| Hospital treatment*2 | 53 (26.2 %) | 48 (22.9 %) |

| Days of hospital stay*2 | 1.4 (3.1) | 1.5 (5.2) |

| Hospitalization due to asthma*2 | 17 (8.4 %) | 17 (8.1 %) |

| Days of hospital stay due to asthma *2 | 0.5 (2.1) | 0.5 (2.4) |

| Number of pneumologist consultations *1 | 1.3 ± 1.4 (0–7) | 1.4 ± 1.3 (0–8) |

| At least 1 OCS treatment *1 | 77 (38.1 %) | 70 (33.7 %;) |

| At least 1 exacerbation *3 | 175 (86.7 %) | 187 (89.1 %) |

| Number of exacerbations *2 | 2 (4) | 2 (3) |

| Unable to work*2 | 162 (80.2 %) | 162 (77.2 %) |

| Days of work absenteeism*2 | 28.1 (34.8) | 25.8 (34.1) |

| Unable to work due to asthma*2 | 113 (55.9 %) | 110 (52.4 %) |

| Days of work absenteeism due to asthma *2 | 10.2 (15.0) | 14.4 (26.2) |

| Current smoker | 34 (16.8 %) | 34 (16.2 %) |

| lgE (IU/mL) at start of rehabilitation | 116 (283) | 105 (312) |

| Patients with IgE > 100 IU/mL (at start of rehab.) | 110 (54.5 %) | 105 (50 %) |

Data given either as mean (standard deviation) or number (percent) for T0, unless otherwise stated; IgE, immunoglobulin E; OCS, oral glucocorticosteroids

*1 In the 3 months directly prior to study inclusion; *2 In the 12 months directly prior to enrollment;

*3 Median and interquartile range are given

eTable 4. Asthma medication of the intervention group and the control group at T0 (baseline) and T3, with number (percent).

| IG | CG | |||||||

| T0 (n = 202) | T3 (n = 181) | T0 (n = 210) | T3 (n = 206) | |||||

| ICS (single or combined preparation) | 189 | 93.6 % | 173 | 95.6 % | 195 | 92.9 % | 180 | 87.4 % |

| ICS/LABA | 160 | 79.2 % | 141 | 77.9 % | 157 | 74.8 % | 148 | 71.8 % |

| ICS single | 29 | 14.4 % | 32 | 17.7 % | 38 | 18.1 % | 32 | 15.5 % |

| OCS (in the last 7 days) | 39 | 19.3 % | 27 | 14.9 % | 26 | 12.4 % | 19 | 9.2 % |

| Montelukast | 37 | 18.3 % | 65 | 35.9 % | 34 | 16.2 % | 28 | 13.6 % |

| LAMA | 48 | 23.8 % | 80 | 44.2 % | 47 | 22.4 % | 46 | 22.3 % |

| Theophyllin | 14 | 6.9 % | 8 | 4.4 % | 8 | 3.8 % | 8 | 3.9 % |

| Omalizumab | 5 | 2.5 % | 5 | 2.8 % | 1 | 0.5 % | 4 | 1.9 % |

| Mepolizumab | 0 | 0.0 % | 1 | 0.6 % | 2 | 1.0 % | 3 | 1.5 % |

CG, control group; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; IG, intervention group; LABA, long-acting beta2-agonists; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; OCS, oral corticosteroids

Randomized controlled trial

Primary outcome

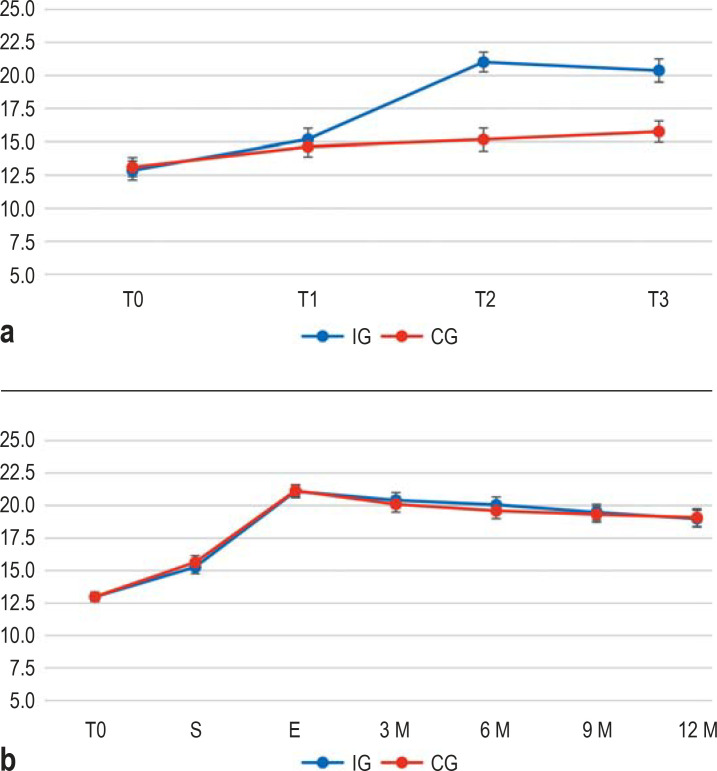

The adjusted mean difference in ACT (primary outcome) showed a 4.71 [3.99; 5.43] point increase for the IG (see Figure 2). This corresponds to a large effect (Cohen’s d = 1.21). At time T3, 68.9% of the IG patients, but only 20.1% of the CG patients, had controlled asthma (p < 0.001).

Figure 2.

a) Randomized controlled trial (RCT; effects between IG and CG): Mean values and 95% confidence intervals of the primary endpoint Asthma Control Test (ACT) from T0 to T3. ACT scores ≥ 20 indicate well-controlled asthma, ACT scores of 5–19 indicate poorly controlled asthma.

b) Pooled cohort observational study (follow-up of the EPRA trial): Mean values and 95% confidence intervals of the ACT scores for the IG and the CG at T0 and at the start (S) and end (E) of rehabilitation. The interval from T0 to start of rehabilitation was 1 month for the IG, and 5 months for the CG.

T0, study inclusion/randomization; T1, start of rehab. for intervention group (IG) = 4 weeks after T0; T2, end of rehab. for IG; T3, 3 months after end of rehab. for IG, and start of rehab. for the control group (CG), who had been on the waiting list (with usual care) prior to T3

Secondary outcomes

With respect to secondary outcomes, the IG performed better, showing medium to strong effects at times T2 and T3. Strong effects at time T3 were shown in quality of life (AQLQ/SGRQ), main symptoms (NRS), self-management (heiQ), and better understanding the asthma illness (IPQ-7).

Observational study

12-month course

No significant differences were observed in the observational study between IG and CG for any outcome measure at the start of rehabilitation, the end of rehabilitation, or any equivalent follow-up times (all results of the Chi²-difference-test were p > 0.05; see eTable 5, eTable 6). At twelve months after the end of rehabilitation, the mean ACT score was 19.00 points [18.51; 19.48], which is 3.54 points [3.08; 3.99] above the score at the start of rehabilitation, and asthma was under control for 55.9% of patients. The results of other outcomes were similar.

eTable 5. Observational study, Model 2 of results: Means (M) and standard deviations (SD) in clinical outcomes.

| Outcome | M (SD) Randomization | M (SD) Admission | M (SD) Discharge | M (SD) 3 months | M (SD) 6 months | M (SD) 9 months | M (SD) 12 months |

| ACT scores | 12.99 (3.67) | 15.46 (4.21) | 21.12 (3.65) | 20.26 (4.20) | 19.83 (4.26) | 19.38 (4.32) | 19.00 (4.50) |

| AQLQ total | 3.95 (0.94) | 4.35 (0.95) | 5.63 (1.04) | 5.38 (1.25) | 5.28 (1.31) | 5.22 (1.38) | 5.15 (1.29) |

| SGRQ total | 47.0 (15.9) | 42.4 (17.1) | 24.7 (16.6) | 25.7 (18.4) | 26.7 (18.5) | 28.4 (18.5) | 29.7 (18.5) |

| Resting dyspnea | 3.18 (4.25) | 2.71 (3.86) | 1.21 (3.03) | 1.53 (3.05) | 1.62 (3.19) | 1.89 (4.71) | 1.92 (4.62) |

| Exertional dyspnea | 6.55 (2.27) | 6.12 (2.32) | 3.78 (2.42) | 3.67 (2.55) | 3.97 (2.61) | 4.33 (2.71) | 4.45 (2.67) |

| Cough | 4.29 (2.74) | 3.83 (2.69) | 1.95 (2.24) | 2.19 (2.43) | 2.36 (2.38) | 2.59 (2.49) | 2.77 (2.63) |

| Sputum | 3.07 (6.54) | 2.50 (5.96) | 1.30 (2.54) | 1.63 (4.22) | 1.73 (4.06) | 1.96 (4.31) | 2.03 (4.74) |

| Pain | 4.16 (2.72) | 3.67 (2.76) | 1.89 (2.35) | 2.32 (2.46) | 2.61 (2.45) | 2.84 (2.59) | 2.82 (2.59) |

| PHQ-9 | 8.23 (4.80) | 7.50 (4.96) | 3.88 (4.65) | 5.19 (4.88) | 5.39 (4.94) | 5.42 (4.88) | 5.63 (5.17) |

| GAD-7 | 7.41 (4.81) | 6.69 (4.48) | 3.33 (4.21) | 4.45 (4.20) | 4.62 (4.30) | 4.59 (4.31) | 4.79 (4.88) |

No significant differences were observed in the observational study between the intervention and control groups for any outcome at any of the equivalent time points (see eTable 6); therefore, results are given for the group as a whole; ACT, Asthma Control Test; AQLQ, Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire; PHQ-9, ?Patient Health Questionnaire 9; SGRQ, St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire

eTable 6. Observational study. For each outcome, model 1 is compared to model 2; the mean differences (M + 95% CI) from model 2 are between the time of measurement at 12 months and the point of randomization/ start of rehabilitation.

| Outcome | Model comparision* | Pre-post differences between T0 (randomization) and 12 months after rehabilitation | Pre-post differences between start of rehabilitation and 12 months after rehabilitation |

| Chi² (df), p-value | M [95% CI] | M [95% CI] | |

| ACT scores | 4.09 (6), p = 0.665 | 6.01 [5.51; 6.52] | 3.54 [3.03; 4.03] |

| AQLQ total | 12.44 (6), p = 0.053 | 1.19 [1.09; 1.30] | 0.80 [0.70; 0.90] |

| SGRQ total | 7.25 (6), p = 0.297 | –17.4 [–19.11; –15.62] | –12.77 [11.08; 14.45] |

| Resting dyspnea | 4.49 (6), p = 0.611 | –1.26 [–1.51; –1.01] | –0.799 [–1.04; –0.56] |

| Exertional dyspnea | 5.17 (6), p = 0.522 | –2.11 [–2.39; 1.83] | –1.67 [–1.94; –1.40] |

| Cough | 5.40 (6), p = 0.493 | –1.52 [–1.83; –1.21] | –1.06 [–1.34; 0.77] |

| Sputum | 8.68 (6), p = 0.193 | –1.04 [–1.30; –0.77] | –0.47 [–0.71; 0.22] |

| Pain | 2.62 (6), p = 0.855 | –1.35 [–1.63; 1.06] | –0.86 [–1.14; 0.58] |

| PHQ-9 | 3.06 (6), p = 0.801 | –2.61 [–3.09; 2.13] | –1.87 [–2.31; 1.43] |

| GAD-7 | 8.89 (6), p = 0.180 | –2.62 [–3.09; 2.14] | –1.90 [–2.31; –1.50] |

ACT, Asthma Control Test; AQLQ, Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire; CI; confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire; M, mean;

PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9; SGRQ, St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire

*Chi²-difference test according to Satorra and Bentler (2001) for comparing model 1 (only for randomization of the same mean values between the intervention group and the control group) and model 2 (for all equivalent time points for the same mean values for the intervention and control groups)

Lung function parameters and 6-minute walking distance (6MWD) during rehabilitation

Both groups had comparable baseline values at the start of rehabilitation, and comparable improvements in lung function parameters and the 6MWD test at the end of rehabilitation. For example, during the rehabilitation process, the FEV1 value prior to the bronchospasmolysis test improved by 0.31 (IG) or 0.27 (CG) liters, and the distance in the 6MWD test improved by 87 meters (IG) or 90 (CG) meters (etable 3).

eTable 3. Lung function parameters, fractionated exhaled nitric oxide, absolute eosinophil count, and 6MWD test of the intervention group (n = 202) and the control group (n = 210) at rehabilitation admission and at discharge, and their differences (+ 95% CI, SRM). Lung function parameters are given before and after the bronchospasmolysis test.

| Group | M at admission | SD at admission | M at discharge | SD at discharge | M difference | SD difference | 95% CI UP | 95% CI LOW | SRM | |

| FEV1 [l] before/after BSLT | IG | 2.58/2.81 | 0.83/0.84 | 2.89/3.00 | 0.76/0.76 | 0.31/0.19 | 0.44/0.37 | 0.25/0.14 | 0.38/0.24 | 0.71/0.51 |

| CG | 2.55/2.73 | 0.81/0.83 | 2.82/2.89 | 0.80/0.81 | 0.27/0.17 | 0.37/0.31 | 0.22/0.12 | 0.32/0.21 | 0.73/0.53 | |

| FEV1 [% pred.] before/after BSLT | IG | 80.46/87.50 | 22.39/20.73 | 90.34/93.61 | 18.00/17.28 | 9.89/6.11 | 14.01/11.89 | 7.96/4.47 | 11.82/7.75 | 0.71/0.51 |

| CG | 81.74/87.30 | 20.74/20.43 | 90.46/92.78 | 18.50/18.61 | 8.73/5.49 | 11.97/10.52 | 7.11/4.06 | 10.35/6.91 | 0.73/0.52 | |

| FEV1/VC [%] | IG | 68.33/86.93 | 13.56/17.15 | 70.98/90.11 | 10.69/13.59 | 2.65/3.19 | 8.88/11.40 | 1.43/1.61 | 3.88/4.76 | 0.30/0.28 |

| CG | 69.53/85.12 | 11.05/14.93 | 71.40/86.41 | 10.48/14.48 | 1.87/1.29 | 5.96/8.99 | 1.06/0.08 | 2.68/2.51 | 0.31/0.14 | |

| FEV1/VC [% pred.] | IG | 70.71/89.97 | 11.62/14.62 | 72.18/91.58 | 10.35/12.38 | 1.47/1.61 | 6.57/7.61 | 0.56/0.56 | 2.37/2.66 | 0.22/0.21 |

| CG | 74.10/89.96 | 14.49/14.77 | 76.23/91.26 | 14.17/12.58 | 2.13/1.31 | 8.14/8.33 | 1.03/0.18 | 3.23/2.43 | 0.26/0.16 | |

| sRtot [kPa*s] before/after BSLT | IG | 1.60/1.11 | 1.28/0.78 | 1.00/0.86 | 0.50/0.35 | –0.59/–0.25 | 1.15/0.66 | –0.75/–0.34 | –0.43/–0.16 | –0.52/–0.38 |

| CG | 1.59/1.14 | 1.16/0.77 | 1.05/0.91 | 0.54/0.48 | –0.54/–0.23 | 0.89/0.52 | –0.66/–0.30 | –0.42/–0.16 | –0.60/–0.44 | |

| sRtot [%pred.] | IG | 149.28/103.91 | 129.12/77.74 | 93.52/79.75 | 50.01/34.76 | –55.76/–24.16 | 114.22/64.55 | –71.51/–33.06 | –40.01/–15.26 | –0.49/–0.37 |

| CG | 147.35/105.75 | 107.83/72.17 | 97.79/84.70 | 51.24/45.84 | –49.56/–21.05 | 83.48/48.06 | –60.85/–27.55 | –38.27/–14.55 | –0.59/–0.44 | |

| FIV1 [l] | IG | 3.34/3.61 | 0.96/1.00 | 3.85/3.96 | 1.00/1.00 | 0.51/0.35 | 0.67/0.54 | 0.42/0.28 | 0.60/0.43 | 0.76/0.65 |

| CG | 3.31/3.55 | 0.98/1.01 | 3.71/3.82 | 0.97/0.98 | 0.41/0.27 | 0.64/0.54 | 0.32/0.20 | 0.49/0.34 | 0.64/0.50 | |

| VC [l] | IG | 3.76/3.96 | 1.01/1.01 | 4.10/4.19 | 1.01/1.02 | 0.34/0.23 | 0.49/0.38 | 0.27/0.17 | 0.40/0.28 | 0.69/0.59 |

| CG | 3.65/3.84 | 0.97/0.96 | 3.95/4.03 | 0.96/0.97 | 0.30/0.19 | 0.44/0.37 | 0.24/0.14 | 0.36/0.24 | 0.68/0.51 | |

| VC [% pred.] | IG | 93.05/97.90 | 17.34/15.72 | 101.30/103.49 | 15.49/15.26 | 8.25/5.59 | 13.05/10.78 | 6.45/4.10 | 10.05/7.08 | 0.63/0.52 |

| CG | 92.91/97.93 | 16.79/15.61 | 100.69/102.79 | 15.12/15.11 | 7.78/4.86 | 11.42/9.64 | 6.24/3.56 | 9.33/6.16 | 0.68/0.50 | |

| RV [l] | IG | 2.80/2.63 | 0.87/0.79 | 2.47/2.43 | 0.63/0.60 | –0.32/–0.21 | 0.52/0.48 | –0.40/–0.27 | –0.25/–0.14 | –0.62/–0.43 |

| CG | 2.70/2.56 | 0.84/0.74 | 2.42/2.40 | 0.67/0.64 | –0.28/–0.16 | 0.48/0.41 | –0.34/–0.22 | –0.21/–0.10 | –0.58/–0.39 | |

| RV [% pred.] | IG | 138.41/129.94 | 40.27/35.08 | 122.10/119.76 | 26.54/24.68 | –16.31/–10.18 | 26.33/24.39 | –19.95/–13.54 | –12.68/–6.81 | –0.62/–0.42 |

| CG | 133.15/126.26 | 36.41/30.91 | 119.60/118.35 | 28.44/27.49 | –13.55/–7.91 | 23.51/19.94 | –16.73/–10.61 | –10.37/–5.21 | –0.58/–0.40 | |

| TLC [l] | IG | 6.58/6.60 | 1.39/1.42 | 6.59/6.62 | 1.35/1.36 | 0.01/0.02 | 0.50/0.48 | –0.06/–0.05 | 0.08/0.08 | 0.02/0.04 |

| CG | 6.37/6.41 | 1.25/1.24 | 6.38/6.43 | 1.25/1.26 | 0.01/0.02 | 0.53/0.44 | –0.06/–0.04 | 0.08/0.07 | 0.02/0.04 | |

| TLC [% pred.] | IG | 106.45/106.65 | 15.59/15.09 | 106.72/106.74 | 14.75/13.11 | 0.27/0.10 | 10.16/8.50 | –1.13/–1.08 | 1.67/1.27 | 0.03/0.01 |

| CG | 104.94/105.73 | 13.89/13.36 | 105.04/105.88 | 13.33/13.46 | 0.10/0.15 | 8.76/7.19 | –1.09/–0.82 | 1.28/1.12 | 0.01/0.02 | |

| RV/TLC [%] | IG | 42.56/39.92 | 9.91/8.41 | 37.75/36.91 | 7.06/6.59 | –4.81/–3.01 | 6.80/5.39 | –5.75/–3.75 | –3.87/–2.27 | –0.71/–0.56 |

| CG | 42.40/39.92 | 9.88/8.41 | 38.06/37.41 | 7.64/7.38 | –4.35/–2.51 | 5.86/4.77 | –5.14/–3.16 | –3.55/–1.87 | –0.74/–0.53 | |

| EOS | IG | 355.9 (Md = 266.3) | 308.5 | 288.8 (Md = 247.9) | 224.5 | –67.2 | 242.9 | –100.7 | –33.7 | –0.28 |

| CG | 304.1 (Md = 235.6) | 355.8 | 237.0 (Md = 192.9) | 261.9 | –67.1 | 188.6 | –92.6 | –41.6 | –0.36 | |

| FENO | IG | 23.75 (Md = 16.00) | 25.36 | 17.60 (Md = 13.0) | 15.30 | –6.15 | 19.81 | –8.88 | –3.42 | –0.31 |

| CG | 19.12 (Md = 12.35) | 18.83 | 15.17 (Md = 11.0) | 13.17 | –3.95 | 13.87 | –5.82 | –2.07 | –0.28 | |

| 6MWD | IG | 555.37 | 86.64 | 642.35 | 88.05 | 86.98 | 67.00 | 77.74 | 96.22 | 1.30 |

| CG | 553.85 | 87.61 | 643.95 | 90.39 | 90.10 | 63.90 | 81.46 | 98.75 | 1.41 |

BSLT, bronchospasmolysis test; EOS, blood eosinophils/µl (absolute eosinophil count); FENO, fractionated exhaled nitric oxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FIV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s;

CI, confidence interval; LOW, lower limit of the 95% CI; M, mean; Md, median; RV, residual volume; SD, standard deviation; SRM, standardized response mean; sRtot, total specific resistance; TLC, total lung capacity;

VC, vital capacity 6MWD, 6-minute walk distance

Discussion

This RCT showed, for the first time worldwide, that a multimodal PR can significantly improve the degree of asthma control in a clinically relevant manner up to three months after the end of rehabilitation, as determined by the ACT (primary endpoint). While improvement in ACT lowered slightly in the twelve months after rehabilitation, it still remained clinically relevant (with a mean difference in ACT > 3 points). In addition, clinically relevant improvements were found in secondary endpoints, such as key symptoms (shortness of breath, cough, sputum), quality of life, psychological stress, and subjective ability to work. Clinically relevant changes during rehabilitation were also demonstrated for various lung function parameters, the 6MWD test, and FeNO (eMethods, eTable 3). Finally, this study underscores that using RCTs to test the effects of in-patient rehabilitation can also be implemented in the German rehabilitation system.

The differences in asthma control between IG and CG at the end of rehabilitation (adjusted mean difference [AMD] = 6.00; d = 1.69) and three months afterwards (AMD = 4.71, d = 1.21), and the improvements in quality of life are strong effects, according to common criteria. Although the broad inclusion criteria of the EPRA-RCT and the slightly different study populations make comparisons difficult, the effects reported here are mostly larger those of other intervention studies. Current RCTs on respiratory physiotherapy, for example, found effects in the ACT of 0.5 (26) and 2.0 points (27), respectively. Wong et al. (28) showed improvements of 4.6 points in the ACT directly at the end of a six-month outpatient asthma management program, which had more stringent inclusion criteria than the EPRA study. Exercise alone can also improve asthma control and quality of life, but to a lesser extent (29). Studies of only drug therapies report somewhat lower effects on asthma control and quality of life (30), similar to newer therapeutic methods such as biologics (31, 32) and bronchial thermoplasty (33). Thus, the effects of PR reported here should be regarded as strong and clinically relevant as compared to other intervention studies; therefore, PR should be seen as an additional effective treatment option for cases of uncontrolled asthma despite adequate medical treatment.

Medium to strong positive effects were also found for secondary outcomes such as dyspnoea, cough, and sputum. The effects on depression and anxiety were stronger than in studies on cognitive–behavioral interventions in asthma patients (34). Relevant improvements were also found in typical proximal outcome criteria of patient education courses (35), such as self-reported adherence, disease and medication attitudes, and self-management skills. These outcome criteria are considered to be predictors for the persistence of effects in a clinical course. In addition, there were clear effects with regard to the subjective ability to work, a relevant predictor for a successful return to work (36). As a result, PR seems to improve both the patients´ management of the illness and their participation in social life, in addition to improving the clinical symptoms.

The results of the subsequent observational study showed clinically relevant effects in primary and secondary outcomes even after one year, although for methodological reasons these observations cannot be traced back to the PR in a monocausal manner. The RCT that directly preceded it, however, showed that the differences in the values between the start of rehabilitation and three months after rehabilitation are directly attributable to the intervention. Therefore, the longer-term courses are also very likely to be (at least partially) due to the PR.

In addition, the parallel, positive course of the treatment results of CG and IG during rehabilitation (including for the lung function parameters and the 6MWD test) and in follow-up show that patients with asthma in the waiting list CG achieved the same rehabilitation effects as patients who did the PR directly (IG), which speaks for the effectiveness of the intervention itself.

The study examined the effectiveness of “complex rehabilitation”, which consists of various components, so that reliable conclusions about the contributions of individual therapeutic components are not possible, and the exact mechanism of action of the intervention cannot be derived from our data with certainty. Adjusting medication (etable 4), improving drug compliance (MARS-D, Table 3), the positive results of smoking cessation (etable 1), and participating in psychosocial therapy are all likely to have contributed to the positive effects. In addition, unspecific effects (e.g., sense of renewal due to the rehabilitation stay, climate factors, allergen avoidance) are possible. However, the persistence of the improvements at three months after the end of the rehabilitation in the RCT, and the persistence of the effects even up to one year after the PR for both groups, suggest that the effects are largely due to the PR.

Table 3. Adjusted mean differences (AMD), including 95% CI, p-values, and Cohen’s d, between the intervention and control group at T2 and T3.

| Outcome | Time point | AMD [95% CI] | p | Cohen’s d |

| ACT | T2 | 6.00 [5.31; 6.69] | < 0.001 | 1.69 |

| T3 | 4.71 [3.99; 5.43] | < 0.001 | 1.27 | |

| AQLQ total | T2 | 1.32 [1.18; 1.45] | < 0.001 | 1.78 |

| T3 | 0.91 [0.76; 1.06] | < 0.001 | 1.14 | |

| SGRQ total | T2 | –18.5 [–16.3; –20.8] | < 0.001 | –1.57 |

| T3 | –15.5 [–12.9; 18.1] | < 0.001 | –1.16 | |

| Exertional dyspnea | T2 | –2.38 [–2.77; –1.98] | < 0.001 | –1.17 |

| T3 | –2.28 [–2.71; –1.85] | < 0.001 | –1.03 | |

| PHQ-9 | T2 | –3.98 [–4.73; –3.24] | < 0.001 | –1.04 |

| T3 | –1.96 [–2.70; –1.23] | < 0.001 | –0.53 | |

| GAD-7 | T2 | –3.52[–4.23; –2.80] | < 0.001 | –0.95 |

| T3 | –2.01 [–2.74; –1.29] | < 0.001 | –0.54 | |

| heiQ-SK | T2 | 0.58 [0.50; 0.67] | < 0.001 | 1.28 |

| T3 | 0.45 [0.35; 0.54] | < 0.001 | 0.89 | |

| IPQ-7 | T2 | 2.02 [1.66; 2.37] | < 0.001 | 1.10 |

| T3 | 1.79 [1.37; 2.22] | < 0.001 | 0.81 | |

| IPQ-4 | T2 | 0.94 [0.61; 1.28] | < 0.001 | 0.53 |

| T3 | 0.23 [–0.12; 047] | 0.200 | 0.13 | |

| IPQ-3 | T2 | 1.40 [0.99; 1.81] | < 0.001 | 0.66 |

| T3 | 0.59 [0.16; 1.01] | 0.011 | 0.27 | |

| MARS-D*1 | T2 | 0.55 [0.28; 0.82] | < 0.001 | 0.41 |

| T3 | 0.37 [0.08; 0.66] | 0.003 | 0.24 | |

| WAS | T2 | 1.18 [0.82; 1.53] | < 0.001 | 0.65 |

| T3 | 1.01 [0.66; 1.36] | < 0.001 | 0.56 | |

| Odds ratio [95% CI] | ||||

| SPE*2 | T2 | 0.32 [0.20; 0.52] | < 0.001 | |

| T3 | 0.73 [0.45;1.14] | 0.163 | ||

ACT, Asthma Control Test (primary endpoint); AQLQ, Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire;

CI, confidence interval; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire; heiQ-SK, Health Education Impact Questionnaire: scale of Skills and techniques; IPQ, Illness Perception

Questionnaire; IPQ-3, How much control do you feel you have over your asthma?; IPQ-4, How much do you think your treatment can help with your asthma?; IPQ-7, How well do you feel you understand your asthma?; MARS-D, Medical Adherence Rating Scale; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9; SGRQ, St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire; SPE, Subjective Prognosis of Employment Scale; WAS, Work Ability

Score *1 based on robust regressions; *2 based on ordinal logistic regressions

eTable 1. Mean and standard deviations in additional secondary outcomes from T0–T3, separated for intervention group and control group.

| Outcome | Group | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

| AQLQ Symptoms | IG | 3.93 | 1.06 | 4.27 | 1.04 | 5.60 | 1.07 | 5.49 | 1.22 |

| CG | 3.73 | 1.03 | 3.93 | 1.09 | 4.07 | 1.10 | 4.33 | 1.12 | |

| AQLQ Activity | IG | 4.07 | 0.92 | 4.33 | 1.01 | 5.57 | 1.04 | 5.43 | 1.16 |

| CG | 4.01 | 0.94 | 4.16 | 1.05 | 4.24 | 1.04 | 4.44 | 1.04 | |

| AQLQ Emotional | IG | 3.95 | 1.23 | 4.36 | 1.27 | 5.60 | 1.15 | 5.57 | 1.36 |

| CG | 3.81 | 1.29 | 4.11 | 1.42 | 4.31 | 1.35 | 4.61 | 1.34 | |

| AQLQ Environment | IG | 4.16 | 1.28 | 4.46 | 1.28 | 5.67 | 1.33 | 5.19 | 1.47 |

| CG | 4.22 | 1.25 | 4.26 | 1.34 | 4.36 | 1.33 | 4.46 | 1.41 | |

| SGRQ Symptoms | IG | 64.32 | 19.95 | 58.94 | 22.39 | 38.94 | 21.19 | 38.56 | 25.52 |

| CG | 67.24 | 17.97 | 64.13 | 19.49 | 61.36 | 20.71 | 59.22 | 20.21 | |

| SGRQ Activity | IG | 50.0 | 19.7 | 47.3 | 21.0 | 30.1 | 22.0 | 29.6 | 23.6 |

| CG | 52.4 | 20.1 | 51.3 | 21.0 | 50.0 | 21.0 | 46.7 | 20.2 | |

| SGRQ Impacts | IG | 38.2 | 17.4 | 34.4 | 18.0 | 18.4 | 17.0 | 18.6 | 17.7 |

| CG | 40.0 | 17.8 | 39.3 | 19.2 | 38.0 | 18.5 | 34.5 | 18.6 | |

| Resting dyspnea* | IG | 3.05 | 2.06 | 2.58 | 1.97 | 1.23 | 1.77 | 1.46 | 1.93 |

| CG | 3.32 | 2.14 | 3.15 | 2.07 | 3.13 | 2.09 | 2.91 | 2.28 | |

| Cough | IG | 4.21 | 2.75 | 3.89 | 2.70 | 2.09 | 2.27 | 2.31 | 2.58 |

| CG | 4.40 | 2.78 | 4.29 | 2.71 | 4.07 | 2.76 | 3.75 | 2.82 | |

| Sputum | IG | 2.94 | 2.64 | 2.42 | 2.35 | 1.43 | 1.93 | 1.64 | 2.28 |

| CG | 3.31 | 2.50 | 3.05 | 2.42 | 3.04 | 2.49 | 2.66 | 2.40 | |

| Pain | IG | 4.17 | 2.73 | 3.58 | 2.77 | 1.85 | 2.42 | 2.30 | 2.62 |

| CG | 4.13 | 2.81 | 4.13 | 2.62 | 3.94 | 2.82 | 3.78 | 2.66 | |

| IPQ-1 | IG | 5.51 | 2.16 | 5.16 | 2.32 | 3.68 | 2.21 | 3.50 | 2.50 |

| CG | 5.63 | 2.33 | 5.58 | 2.30 | 5.63 | 2.26 | 5.43 | 2.30 | |

| IPQ-2 | IG | 8.69 | 2.22 | 8.21 | 2.53 | 8.84 | 2.35 | 8.95 | 2.35 |

| CG | 8.79 | 2.04 | 8.71 | 1.97 | 8.76 | 1.93 | 8.60 | 1.96 | |

| IPQ-5 | IG | 6.06 | 2.07 | 5.67 | 2.16 | 4.11 | 2.51 | 4.00 | 2.51 |

| CG | 6.23 | 2.15 | 6.23 | 2.08 | 6.17 | 2.08 | 5.67 | 2.13 | |

| IPQ-6 | IG | 6.37 | 2.61 | 5.64 | 2.73 | 4.06 | 2.97 | 3.73 | 2.84 |

| CG | 6.39 | 2.77 | 6.03 | 2.83 | 6.05 | 2.79 | 5.73 | 2.91 | |

| IPQ-8 | IG | 5.41 | 2.73 | 4.71 | 2.79 | 3.22 | 2.59 | 3.57 | 2.87 |

| CG | 5.55 | 2.88 | 5.34 | 2.73 | 5.26 | 2.70 | 5.14 | 2.77 | |

| Number | Procent | Number | Procent | Number | Procent | Number | Procent | ||

| Current smoker | IG | 34 | 16.8 % | 33 | 16.3 % | 10 | 4.9 % | 15 | 7.4 % |

| CG | 34 | 16.1 % | 32 | 15.2 % | 34 | 16.1 % | 33 | 15.7 % | |

AQLQ, Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire; CG, control group; IG, intervention group; M, mean; SD, standard deviations; IPQ, Illness

Perception Questionnaire; IPQ-1, How much does your asthma affect your life?; IPQ-2, How long do you think your asthma will continue?;

IPQ-5, How much do you experience symptoms from your asthma?; IPQ-6, How concerned are you about your asthma ?; IPQ-8, How

much does your asthma affect you emotionally?; SGRQ, St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire; * dyspnoea intensity at rest

Previous studies have shown that patient education (10, 37), physical exercise (12), and respiratory physiotherapy (11) are effective as single measures. The “PR” package of measures, however, produces stronger effects from these individual components than those reported in the literature, and this in a multitude of outcomes. It can therefore be assumed that the effects of PR can be traced back to the interaction of the multimodal therapy components.

The National Asthma Care Guideline from 2009 (38) explicitly called for RCTs to be carried out for more evidence regarding rehabilitation for patients with asthma. The German Council of Experts for the Assessment of Developments in the Health Care System (2014) also identified the lack of evidence—and in particular, the lack of RCTs—as a core problem in the rehabilitation sector. Missing RCTs are usually justified by the fact that insured persons with an approved application have a legal right to rehabilitation and therefore should not be randomly assigned to a control group without rehabilitation. EPRA shows by way of example that RCTs for testing rehabilitation effects can also be implemented within this legal framework in Germany (39).

Limitations

Limitations of this study include that it is a single-center study, and therefore, its results cannot simply be transferred to all rehabilitation programs for asthma. The EPRA therapy program is intensive and comprehensive, but meets the structural guidelines of the German statutory health insurers (40). Similar prerequisites are likely to be present at other high-performance rehabilitation clinics.

While patients throughout Germany are assigned to the Bad Reichenhall Clinic through different health insurers, over 90% of the cases were assigned through the Statutory pension insurance; in other words, they were mostly patients who were not retired. In addition, individual patient groups (emergency cases, patients with follow-up rehabilitation [Anschlussheilbehandlung, AHB]) could not be included due to the design of the study. Therefore, caution is advised regarding the transferability of these results to other patient groups.

Additionally, blinding was not possible. Furthermore, the proportion of unspecific effects (due to change of location, work leave) or purely medicinal effects in the overall effect cannot be specified exactly. Finally, the results in the secondary outcomes must be interpreted exploratively.

Conclusions

The EPRA study shows that a in-patient pulmonary rehabilitation of 3 weeks for patients with uncontrolled asthma leads to a significant and clinically relevant improvement in asthma control up to three months after the end of rehabilitation. This effect is still detectable to a clinically relevant extent after one year. Therefore, patients whose asthma is poorly controlled despite adequate medical treatment should be referred to an appropriate rehabilitation.

Supplementary Material

eMethods

Description of the intervention

Both patient groups underwent intensive and comprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation of at least three weeks (albeit with a three-month interval between the groups); this corresponded to the quality guidelines of the German statutory health insurers. The therapy program was planned individually for each patient, based on the health deficits recorded during the mandatory admission examination as well as on the rehabilitation goals based on these data and made together with the patient. The therapy program was reviewed at least once a week during rehabilitation at the specialist consultations.

The rehabilitation program comprised the following components of the non-drug therapy (M = mandatory for all rehabilitation patients, except if individual contraindications were present; O = optional; eBox):

Finally, routine pulmonary checkups by a specialist were carried out, and the asthma medication was optimized as necessary, as an mandatory part of medical rehabilitation for asthma.

Sample calculation, randomization, and statistics

Sample calculations

Based on previous (unpublished) pre–post studies at the Bad Reichenhall Clinic, a standardized effect of at least d = 0.3 in the primary outcome (asthma control at 3 months after PR) was assumed. With a power of 0.8 and a significance level of alpha = 0.05, n= 176 (and therefore, a total of n= 352) test persons per group must be evaluated to confirm the effect with statistical inference.

As studies using waiting list control group designs are largely lacking in the German rehabilitation system, a relatively high drop-out rate of 30% between T0 and T3 was assumed (and especially in the CG) (for instance, incorrect inclusion due to an wrong asthma diagnosis, withdrawal of study consent, did not start rehabilitation). Therefore, at least 503 patients should be included and randomized in the study. Further, to minimize seasonal disruptive effects, the study inclusion phase should be at least one year but, for organizational reasons, no longer than two full years. After the maximum planned study inclusion phase (6/2015–8/2017) was complete, n= 430 patients were randomized; of these, n= 412 patients remained in the study (IG, n = 202; CG, n = 210; see Table 1 in the article). The drop-out rate after randomization was therefore considerably lower than assumed (at approximately 3%).

Randomization

The randomization list was created at the University of Würzburg. Randomization was stratified by age group (< 55 years, < 65 years, ≥ 65 years) for the following reasons: first, age has an effect on the primary outcome (asthma control) (e1). The limit of being older than 55 years was based on the mean age expected for asthma patients at the Bad Reichenhall Clinic when the study was planned. Further, empirical data show that the exacerbation rate increases in asthma patients over the age of 55 (e2).

The second limit (being older than 65 years) reflects that employment (exposure on the job) or retirement can influence asthma control. Block randomization within the strata was not used. A randomization list was created for 272 patients in the groups < 55 and 55–64, and for 60 patients in the group ≥ 65. The length of the randomization lists represented the expected frequency distribution of patients in the various age groups when the study was planned, based on the previous experience of the Bad Reichenhall Clinic.

Statistical methods (RCT)

The multiple imputations were carried out in R using the “mice” package (e4). For most outcomes, analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were performed with the corresponding T0 value, age, and group membership as predictors. Outcomes and residuals were checked for violations of normal distribution, violations of heteroscedasticity, and the influence of outliers.

As a further control, robust regressions (function “lmRob” of the R package “robustbase” [e5]) were carried out. Clear differences between the standard analyses and the robust regressions were only observed in the analyses of the Medical Adherence Scale (MARS-D). The (more conservative) results of the robust regressions (based on per-protocol analyses) are given in the text.

Ordinal or binary-logistic regressions were carried out to analyze the subjective prognosis of employment (SPE scale) and smoking status; these also used the value at T0, age, and group membership as predictors. Results are given as odds ratios.

Evaluation of the observational study

Structuring and data pooling

To analyze the observational study, data from the IG and CG at T0 and at all time points with respect to PR (i.e., at the start of rehabilitation, the end of rehabilitation, and three, six, nine, and twelve months after the end of rehabilitation) were used. Due to the waiting list design, this time point assignment for the CG does not correspond to that of the RCT. For example, the “start of rehabilitation” corresponds to time T1 (= four weeks after randomization) for IG patients, but T3 (= five months after randomization) for CG patients.

Statistical methods

A structural equation model approach was used for evaluation. Measurements at the different time points were modeled as variables that covary with one another (e6). Treatment group membership (IG or CG) was used as a group variable (multi-group model). Two models were calculated.

In model 1, all mean values between the two groups were freely estimated except at T0, at which point they were determined to be the same for both groups: as the groups were created through randomization, both groups came from the same population, and differences can only have come about by chance.

In model 2, the means of all variables were restricted as being equal between both groups. Model 2 tests the hypothesis that the two groups did not differ in any of the mean values (same courses before, during and after PR). Model 2 was compared to Model 1 using the Chi²-difference test. A p-value > 0.05 indicates that model 2 does not fit the data significantly worse than model 1, i.e. that group membership had no relevant influence on the course.

All model estimates were calculated using robust maximum likelihood estimators (MLR). The correction formula according to Satorra and Bentler (2001) was used to calculate the Chi² difference test.

Persons for whom values were missing were included using maximum likelihood estimation. Age and sex were included in the models as auxiliary variables (variables that covariate with all variables) in order to improve the estimation of persons with missing values. In addition, as a sensitivity analysis, all calculations were only carried out with persons for whom data were available at all times (“missing listwise”). Since no relevant differences were found between the two calculation methods, only the results were reported in which all persons were included in the analyses. All analyses were carried out in R (e3) using the “lavaan” (e7) package.

(M) Sports and exercise therapy, consisting of (M) endurance training (five units of 45–60 min, every week), (M) strength training (three units of 45–60 min, every week), (O) whole-body vibration training (seven units every week), and (O) inspiratory muscle training (seven 21-min units every week).

Comprehensive patient education ([M] one-week asthma course [seven 45-min teaching units (TUs) during one week]), (M) practical application training for inhaled medication and peak flow meter training (one 60-min TU), (O) education for allergy sufferers (one 60-min TU).

(M) Group breathing physiotherapy (three 45-min units every week); if necessary, also (O) individual breathing physiotherapy. Optional respiratory therapy techniques were (O) Buteyko breathing technique for patients with dysfunctional breathing patterns, and participation in (O) a respiratory physiotherapy seminar on cough techniques for patients with chronic dry cough. In addition, in the case of mucostasis, further (O) special inhalation therapies (brine inhalation, oscillating ultrasonic pressure nebulizer) and other physical therapy measures were offered.

If necessary (e.g., PHQ > 9 points, GAD 7> 9 points, or medical indication), (O) psychosocial support measures, such as psychological individual and group therapy, as well as the entire spectrum of social counseling (LTA, MBOR) were offered

All smokers were offered (O) a comprehensive smoking cessation program (behavioral therapy, free drug cessation aids).

In the case of food intolerances/allergies, as well as for participants who were over- or underweight, comprehensive nutritional counseling was given along with the corresponding diet.

Table 2. Mean (M) and standard deviations (SD) of primary outcome (ACT) and of selected secondary outcomes from T0 – T3, given separately for the intervention group (IG) and control group (CG).

| Outcome | Group | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

| ACT | IG | 12.86 | 3.67 | 15.19 | 4.22 | 21.02 | 3.79 | 20.38 | 4.47 |

| CG | 13.11 | 3.81 | 14.63 | 4.02 | 15.17 | 4.56 | 15.76 | 4.25 | |

| AQLQ total | IG | 4.00 | 0.94 | 4.32 | 0.97 | 5.60 | 1.04 | 5.43 | 1.12 |

| CG | 3.90 | 0.92 | 4.08 | 1.03 | 4.20 | 1.01 | 4.42 | 1.02 | |

| SGRQ total | IG | 46.06 | 15.92 | 42.34 | 17.14 | 25.27 | 17.21 | 25.17 | 18.72 |

| CG | 48.24 | 15.83 | 46.99 | 17.30 | 45.44 | 16.37 | 42.24 | 16.63 | |

| Exertional dyspnea *1 | IG | 6.39 | 2.27 | 6.08 | 2.33 | 3.88 | 2.45 | 3.65 | 2.68 |

| CG | 6.70 | 2.16 | 6.69 | 2.13 | 6.43 | 2.19 | 6.13 | 2.39 | |

| PHQ | IG | 8.10 | 4.81 | 7.50 | 5.01 | 4.17 | 4.79 | 5.30 | 5.22 |

| CG | 8.46 | 5.34 | 8.51 | 5.27 | 8.39 | 5.27 | 7.54 | 5.00 | |

| GAD-7 | IG | 7.24 | 4.82 | 6.41 | 4.47 | 3.63 | 4.38 | 4.75 | 4.66 |

| CG | 7.77 | 5.15 | 7.65 | 5.12 | 7.45 | 5.01 | 7.08 | 5.10 | |

| heiQ-SK | IG | 2.81 | 0.59 | 2.84 | 0.62 | 3.41 | 0.54 | 3.36 | 0.60 |

| CG | 2,86 | 0.58 | 2.90 | 0.56 | 2.86 | 0.57 | 2.93 | 0.58 | |

| IPQ-7 | IG | 6.13 | 2.75 | 6.12 | 2.50 | 8.41 | 1.89 | 8.04 | 2.40 |

| CG | 6.28 | 2.65 | 6.37 | 2.48 | 6.43 | 2.40 | 6.28 | 2.38 | |

| IPQ-4 | IG | 7.50 | 2.20 | 7.88 | 1.94 | 8.47 | 1.87 | 8.27 | 2.06 |

| CG | 7.66 | 2.06 | 7.68 | 1.92 | 7.57 | 1.95 | 8.06 | 1.67 | |

| IPQ-3 | IG | 5.76 | 2.28 | 6.06 | 2.18 | 7.48 | 2.31 | 7.05 | 2.49 |

| CG | 5.85 | 2.33 | 5.98 | 2.25 | 6.11 | 2.22 | 6.49 | 2.11 | |

| MARS-D | IG | 22.33 | 2.81 | 22.34 | 2.73 | 23.58 | 1.72 | 23.21 | 2.46 |

| CG | 21.99 | 3.30 | 22.16 | 3.29 | 22.02 | 3.56 | 22.34 | 3.27 | |

| WAS | IG | 5.70 | 2.26 | 5.94 | 2.12 | 6.84 | 2.40 | 6.96 | 2.26 |

| CG | 5.91 | 2.12 | 5.86 | 2.23 | 5.79 | 2.30 | 6.04 | 2.12 | |

| SPE *2 | IG | 1.71 (Md =2.0) | 0.75 (IQR = 1) | 1.60 (Md = 2.0) | 0.69(IQR = 1) | 1.48 (Md = 1.0) | 0.71(IQR = 1) | 1.52 (Md = 1.0) | 0.71(IQR = 1) |

| CG | 1.68 (Md = 2.0) | 0.74(IQR = 1) | 1.68 (Md = 2.0) | 0.71(IQR = 1) | 1.70 (Md = 2.0) | 0.73(IQR = 1) | 1.57 (Md = 1.0) | 0.75(IQR = 1) | |

ACT, Asthma Control Test (primary endpoint); AQLQ, Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire; CI, confidence interval; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Questionnaire; heiQ-SK, Health Education Impact Questionnaire, scale of Skills and techniques; IPQ, Illness Perception Questionnaire; MARS-D, Medical Adherence Rating Scale; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; SGRQ, St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire; SPE, Subjective Prognosis of Employment Scale; WAS, Work Ability Score

*1 intensity of dyspnea during exercise; *2 additional information on median (Md) and interquartile range (IQR)

eBOX. The main components of non-drug therapy for patients in the EPRA study.

Sports and movement therapy (endurance and strength training, whole-body vibration training, inspiratory muscle training)

Comprehensive patient education (one-week asthma course, inhaler device training, Allergen avoidance education for people with allergies)

All forms of respiratory physiotherapy (RP) (group RP, individual RP, Buteyko, bronchial drainage method)

Psychological diagnostics, therapy, and counseling (individually and/or in group)

Social counseling

Nutritional counseling/therapy

Allergen avoidance measures and allergen avoidance education

Smoking cessation

eTable 2. Adjusted mean differences including 95% CI, p-values, and Cohen’s d effect size between the intervention group and the control group at T2 and T3.

| Outcome | Time point | AMD [95% CI] | p-value | Cohen’s d |

| AQLQ Symptoms | T2 | 1.41 [1.24; 1.58] | < 0.001 | 1.65 |

| T3 | 1.03 [0;84; 1.22] | < 0.001 | 1.07 | |

| AQLQ Activity | T2 | 1.28 [1.14; 1.43] | < 0.001 | 1.69 |

| T3 | 0.94 [0.78; 1.11] | < 0.001 | 1.10 | |

| AQLQ Emotional | T2 | 1.20 [1.02; 1.38] | < 0.001 | 1.28 |

| T3 | 0.86 [0.66; 1.06] | < 0.001 | 0.84 | |

| AQLQ Environment | T2 | 1.35 [1.15; 1.54] | < 0.001 | 1.31 |

| T3 | 0.76 [0.54; 0.99] | < 0.001 | 0.67 | |

| SGRG Symptoms | T2 | –20.6 [–24.0; –17.2] | <0.001 | –1.19 |

| T3 | –18.9 [–22.8; –15.1] | < 0.001 | –0.94 | |

| SGRQ Activity | T2 | –18.2 [–21.2; –15.1] | < 0.001 | –1.15 |

| T3 | 15.5 [–18.9; –12.2] | < 0.001 | –0.89 | |

| SGRQ Impacts | T2 | –18.3 [–20.9; –15.8] | < 0.001 | –1.40 |

| T3 | –14.7 [–17.4; –12.0] | < 0.001 | –1.06 | |

| Resting dyspnea*1 | T2 | –1.78 [–2.11; 1.46] | < 0.001 | –1.05 |

| T3 | –1.33 [–1.69; –0.96] | < 0.001 | –0.70 | |

| Cough | T2 | –1.90 [–2.33; –1.47] | < 0.001 | –0.85 |

| T3 | –1.34 [–1.79; –0.89] | < 0.001 | –0.58 | |

| Sputum | T2 | –1.42 [–1.77; –1.07] | < 0.001 | –0.78 |

| T3 | –0.82 [–1.19; –0.45] | < 0.001 | –0.43 | |

| Pain | T2 | –2.11 [–2.52; –1.17] | < 0.001 | –1.01 |

| T3 | –1.50 [–1.93; –1.07} | < 0.001 | –0.68 | |

| IPQ-1 | T2 | –1.88 [–2.20; –1.55] | < 0.001 | –1.12 |

| T3 | –1.86 [–2.25; –1.48] | < 0.001 | –0.94 | |

| IPQ-2 | T2 | 0.14 [–0.19; 0.47] | 0.402 | 0.083 |

| T3 | 0.41 [0.07; 0.74] | 0.020 | 0.231 | |

| IPQ-5 | T2 | –1.95 [–2.31; –1.59] | < 0.001 | –1.05 |

| T3 | –1.57 [–1.96; –1.19] | < 0.001 | –0.79 | |

| IPQ-6 | T2 | –1.98 [–2.42; –1.54] | < 0.001 | –0.87 |

| T3 | –1.99 [–2.43; –1.55] | < 0.001 | –0.88 | |

| IPQ-8 | T2 | –1.96 [–2.38; –1.53] | < 0.001 | –0.89 |

| T3 | –1.49 [–1.95; –1.03] | < 0.001 | –0.63 | |

| Odds ratio [95% CI] | ||||

| Current smoker*2 | T2 | 0.03 [0.01; 0.14] | < 0.001 | |

| T3 | 0.12 [0.04; 0.38] | < 0.001 | ||

AMD, adjusted mean difference; AQLQ, Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire; CG, control group; CI, confidence interval; IG, intervention group; SGRQ, St. George´s Respiratory Questionnaire; IPQ, Illness Perception Questionnaire; IPQ-1, How much does your asthma ?affect your life?; IPQ-2, How long do you think your asthma will continue?; IPQ-5, How much do you experience symptoms from your asthma ?; IPQ-6, How concerned are you about your asthma ?; IPQ-8, How much does your illness affect you emotionally?

*1 Dyspnea intensity at rest; *2 based on logistic regressions

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Dr. Veronica A. Raker.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all EPRA patients, who cooperatively filled out up to eight extensive questionnaires over a period of more than a year. We also thank the study assistants (B. Obermaier, M. Messerschmidt, and A. Klotz) and the DRV Bayern Süd, who supported the study financially. We would like to thank the Department of General Practice and Health Services Research and the Department of Internal Medicine VI, Clinical Pharmacology, and Pharmacoepidemiology of the Heidelberg University Hospital for the use of the MARS-D.

Data sharing statement

Anonymized data can be requested by other scientists for research purposes.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Dr. Schultz has received consulting honoraria from Berlin Chemie, Sanofi-Aventis, and GSK, reimbursement of conference registration fees and travel expenses from Boehringer, and honoraria for the preparation of scientific meetings from Novartis, AstraZeneca, Berlin Chemie, and Boehringer.

Dennis Nowak has received honoraria for lecturing activities from Berlin Chemie, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Mundipharma, Novartis, Hexal, and Lilly, and consulting honoraria from Pfizer (smoking cessation).

The remaining authors declare that no conflict of interest exist..

References

- 1.Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, 2020. www.ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/GINA-2020-full-report_-final-_wms.pdf (last accessed on 6 July 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buhl R, Bals R, Baur X, et al. [Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of asthma - guideline of the German Respiratory Society and the German Atemwegsliga in cooperation with the Paediatric Respiratory Society and the Austrian Society of Pneumology] Pneumologie. 2017;71 doi: 10.1055/s-0044-100881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bundesärztekammer, Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung, Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften. Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Asthma - Langfassung, 3rd edition. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robert Koch-Institut (ed.) Asthma bronchiale. Faktenblatt zu GEDA 2012: Ergebnisse der Studie „Gesundheit in Deutschland aktuell 2012“. RKI, Berlin 2014; www.rki.de/DE/Content/Gesundheitsmonitoring/Gesundheitsberichterstattung/GBEDownloadsF/Geda2012/Asthma_bronchiale.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (last accessed on 6 July 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demoly P, Annunziata K, Gubba E, Adamek L. Repeated cross-sectional survey of patient-reported asthma control in Europe in the past 5 years. Eur Respir Rev. 2012;21:66–74. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00008111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Price D, Fletcher M, van der Molen T. Asthma control and management in 8,000 European patients: the REcognise Asthma and LInk to Symptoms and Experience (REALISE) survey. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2014;24 doi: 10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emtner M, Herala M, Stalenheim G. High-intensity physical training in adults with asthma A 10-week rehabilitation program. Chest. 1996;109:323–330. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ochmann U, Kotschy-Lang N, Raab W, Kellberger J, Nowak D, Jorres RA. Long-term efficacy of pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with occupational respiratory diseases. Respiration. 2012;84:396–405. doi: 10.1159/000337271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lingner H, Ernst S, Grobetahennig A, et al. Asthma control and health-related quality of life one year after inpatient pulmonary rehabilitation: the ProKAR Study. J Asthma. 2015;52:614–621. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2014.996650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gibson PG, Powell H, Coughlan J, et al. Self-management education and regular practitioner review for adults with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001117. CD001117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruton A, Lee A, Yardley L, et al. Physiotherapy breathing retraining for asthma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6:19–28. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30474-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mendes FA, Goncalves RC, Nunes MP, et al. Effects of aerobic training on psychosocial morbidity and symptoms in patients with asthma: a randomized clinical trial. Chest. 2010;138:331–337. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schultz K, Seidl H, Jelusic D, et al. Effectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation for patients with asthma: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial (EPRA) BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17 doi: 10.1186/s12890-017-0389-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schatz M, Kosinski M, Yarlas AS, Hanlon J, Watson ME, Jhingran P. The minimally important difference of the Asthma Control Test. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:719–723 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schatz M, Zeiger RS, Yang SJ, et al. Change in asthma control over time: predictors and outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juniper EF, Buist AS, Cox FM, Ferrie PJ, King DR. Validation of a standardized version of the asthma quality of life questionnaire. Chest. 1999;115:1265–1270. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.5.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM, Littlejohns P. A self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation The St. George‘s Respiratory Questionnaire. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:1321–1327. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.6.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahler C, Hermann K, Horne R, et al. Assessing reported adherence to pharmacological treatment recommendations Translation and evaluation of the Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS) in Germany. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16:574–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Main J, Weinman J. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60:631–637. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osborne RH, Elsworth GR, Whitfield K. The Health Education Impact Questionnaire (heiQ): an outcomes and evaluation measure for patient education and self-management interventions for people with chronic conditions. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66:192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ilmarinen J. Work ability—a comprehensive concept for occupational health research and prevention. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2009;35:1–5. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mittag O, Raspe H. [A brief scale for measuring subjective prognosis of gainful employment: findings of a study of 4279 statutory pension insurees concerning reliability (Guttman scaling) and validity of the scale] Rehabilitation (Stuttg) 2003;42:169–174. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences 2nd edition. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Bonin D, Klein SD, Wurker J, et al. Speech-guided breathing retraining in asthma: a randomised controlled crossover trial in real-life outpatient settings. Trials. 2018;19 doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-2727-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ritz T, Rosenfield D, Steele AM, Millard MW, Meuret AE. Controlling asthma by training of Capnometry-Assisted Hypoventilation (CATCH) vs slow breathing: a randomized controlled trial. Chest. 2014;146:1237–1247. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong LY, Chua SS, Husin AR, Arshad H. A pharmacy management service for adults with asthma: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Fam Pract. 2017;34:564–573. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmx028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freitas PD, Silva AG, Ferreira PG, et al. Exercise improves physical activity and comorbidities in obese adults with asthma. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018;50:1367–1376. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bateman ED, Esser D, Chirila C, et al. Magnitude of effect of asthma treatments on asthma quality of life questionnaire and asthma control questionnaire scores: systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:914–922. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henriksen DP, Bodtger U, Sidenius K, et al. Efficacy, adverse events, and inter-drug comparison of mepolizumab and reslizumab anti-IL-5 treatments of severe asthma—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Clin Respir J. 2018;5 doi: 10.1080/20018525.2018.1536097. 1536097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tian BP, Zhang GS, Lou J, Zhou HB, Cui W. Efficacy and safety of benralizumab for eosinophilic asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Asthma. 2018;55:956–965. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2017.1379534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Castro M, Rubin AS, Laviolette M, et al. Effectiveness and safety of bronchial thermoplasty in the treatment of severe asthma: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:116–124. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0354OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yorke J, Adair P, Doyle AM, et al. A randomised controlled feasibility trial of group cognitive behavioural therapy for people with severe asthma. J Asthma. 2017;54:543–554. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2016.1229335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faller H, Reusch A, Meng K. DGRW-Update: Patientenschulung. Rehabilitation. 2011;50:284–291. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1285889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kinnunen U, Natti J. Work ability score and future work ability as predictors of register-based disability pension and long-term sickness absence: A three-year follow-up study. Scand J Public Health. 2018;46:321–330. doi: 10.1177/1403494817745190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kohler B, Kellerer C, Schultz K, et al. An internet-based asthma self-management program increases knowledge about asthma—results of a randomized controlled trial. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;117:64–71. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bundesärztekammer (BÄK), Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV), Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Asthma - Langfassung, 2nd edition. Version 5. 2009, last updated: August 2013. www.versorgungsleitlinien.de/themen/asthma (last accessed on 6 July 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hüppe A, Langbrandtner J, Lill C, Raspe H. The effectiveness of actively induced medical rehabilitation in chronic inflammatory bowel disease - results from a randomized controlled trial (MERCED) Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;117:89–96. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deutsche Rentenversicherung. Strukturqualität von Reha-Einrichtungen - Anforderungen der Deutschen Rentenversicherung. 2nd edition, July 2014. www.deutsche-rentenversicherung.de/Allgemein/de/Inhalt/3_Infos_fuer_Experten/01_sozialmedizin_forschung/downloads/quali_strukturqualitaet/Broschuere_Strukturanforderungen.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=9.2012 (last accessed on 27 May 2020) [Google Scholar]

- E1.Kaplan A, Hardjojo A, Yu S, Price D. Asthma across age: insights from primary care. Front Pediatr. 2019,;7 doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Bloom CI, Nissen F, Douglas IJ, Smeeth L, Cullinan P, Quint JK. Exacerbation risk and characterisation of the UK‘s asthma population from infants to old age. Thorax. 2018;73:313–320. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.R Core Team R. A language and environment for statistical computing. In. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. www.R-project.org/ (last accessed on 27 May 2020) 2019 [Google Scholar]

- E4.van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K, Robitzsch A, Vink G, Doove L, Jolani S, Schouten R, Gaffert P, Meinfelder F, Gray B. mice. R-Package version 3.7.0. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/mice/mice.pdf (last accessed on 27 May 2020) (2019) [Google Scholar]

- E5.Maechler M, Rousseeuw P, Croux C, Todoroc V, Ruckstuhl A, Salibian-Barrera M, Verbeke T, Koller M, Conceicao E.L.T., di Palma, M.A. Robustbase; R-Package version 0.93 [Google Scholar]

- E6.Newsom, JT. Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York: Routledge. 2015 doi: 10.1080/10705511.2016.1276837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Rosseel Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software; 2012;48:1–36. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

Description of the intervention

Both patient groups underwent intensive and comprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation of at least three weeks (albeit with a three-month interval between the groups); this corresponded to the quality guidelines of the German statutory health insurers. The therapy program was planned individually for each patient, based on the health deficits recorded during the mandatory admission examination as well as on the rehabilitation goals based on these data and made together with the patient. The therapy program was reviewed at least once a week during rehabilitation at the specialist consultations.

The rehabilitation program comprised the following components of the non-drug therapy (M = mandatory for all rehabilitation patients, except if individual contraindications were present; O = optional; eBox):

Finally, routine pulmonary checkups by a specialist were carried out, and the asthma medication was optimized as necessary, as an mandatory part of medical rehabilitation for asthma.

Sample calculation, randomization, and statistics

Sample calculations

Based on previous (unpublished) pre–post studies at the Bad Reichenhall Clinic, a standardized effect of at least d = 0.3 in the primary outcome (asthma control at 3 months after PR) was assumed. With a power of 0.8 and a significance level of alpha = 0.05, n= 176 (and therefore, a total of n= 352) test persons per group must be evaluated to confirm the effect with statistical inference.

As studies using waiting list control group designs are largely lacking in the German rehabilitation system, a relatively high drop-out rate of 30% between T0 and T3 was assumed (and especially in the CG) (for instance, incorrect inclusion due to an wrong asthma diagnosis, withdrawal of study consent, did not start rehabilitation). Therefore, at least 503 patients should be included and randomized in the study. Further, to minimize seasonal disruptive effects, the study inclusion phase should be at least one year but, for organizational reasons, no longer than two full years. After the maximum planned study inclusion phase (6/2015–8/2017) was complete, n= 430 patients were randomized; of these, n= 412 patients remained in the study (IG, n = 202; CG, n = 210; see Table 1 in the article). The drop-out rate after randomization was therefore considerably lower than assumed (at approximately 3%).

Randomization

The randomization list was created at the University of Würzburg. Randomization was stratified by age group (< 55 years, < 65 years, ≥ 65 years) for the following reasons: first, age has an effect on the primary outcome (asthma control) (e1). The limit of being older than 55 years was based on the mean age expected for asthma patients at the Bad Reichenhall Clinic when the study was planned. Further, empirical data show that the exacerbation rate increases in asthma patients over the age of 55 (e2).

The second limit (being older than 65 years) reflects that employment (exposure on the job) or retirement can influence asthma control. Block randomization within the strata was not used. A randomization list was created for 272 patients in the groups < 55 and 55–64, and for 60 patients in the group ≥ 65. The length of the randomization lists represented the expected frequency distribution of patients in the various age groups when the study was planned, based on the previous experience of the Bad Reichenhall Clinic.

Statistical methods (RCT)

The multiple imputations were carried out in R using the “mice” package (e4). For most outcomes, analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were performed with the corresponding T0 value, age, and group membership as predictors. Outcomes and residuals were checked for violations of normal distribution, violations of heteroscedasticity, and the influence of outliers.

As a further control, robust regressions (function “lmRob” of the R package “robustbase” [e5]) were carried out. Clear differences between the standard analyses and the robust regressions were only observed in the analyses of the Medical Adherence Scale (MARS-D). The (more conservative) results of the robust regressions (based on per-protocol analyses) are given in the text.

Ordinal or binary-logistic regressions were carried out to analyze the subjective prognosis of employment (SPE scale) and smoking status; these also used the value at T0, age, and group membership as predictors. Results are given as odds ratios.

Evaluation of the observational study

Structuring and data pooling

To analyze the observational study, data from the IG and CG at T0 and at all time points with respect to PR (i.e., at the start of rehabilitation, the end of rehabilitation, and three, six, nine, and twelve months after the end of rehabilitation) were used. Due to the waiting list design, this time point assignment for the CG does not correspond to that of the RCT. For example, the “start of rehabilitation” corresponds to time T1 (= four weeks after randomization) for IG patients, but T3 (= five months after randomization) for CG patients.

Statistical methods

A structural equation model approach was used for evaluation. Measurements at the different time points were modeled as variables that covary with one another (e6). Treatment group membership (IG or CG) was used as a group variable (multi-group model). Two models were calculated.

In model 1, all mean values between the two groups were freely estimated except at T0, at which point they were determined to be the same for both groups: as the groups were created through randomization, both groups came from the same population, and differences can only have come about by chance.

In model 2, the means of all variables were restricted as being equal between both groups. Model 2 tests the hypothesis that the two groups did not differ in any of the mean values (same courses before, during and after PR). Model 2 was compared to Model 1 using the Chi²-difference test. A p-value > 0.05 indicates that model 2 does not fit the data significantly worse than model 1, i.e. that group membership had no relevant influence on the course.

All model estimates were calculated using robust maximum likelihood estimators (MLR). The correction formula according to Satorra and Bentler (2001) was used to calculate the Chi² difference test.

Persons for whom values were missing were included using maximum likelihood estimation. Age and sex were included in the models as auxiliary variables (variables that covariate with all variables) in order to improve the estimation of persons with missing values. In addition, as a sensitivity analysis, all calculations were only carried out with persons for whom data were available at all times (“missing listwise”). Since no relevant differences were found between the two calculation methods, only the results were reported in which all persons were included in the analyses. All analyses were carried out in R (e3) using the “lavaan” (e7) package.

(M) Sports and exercise therapy, consisting of (M) endurance training (five units of 45–60 min, every week), (M) strength training (three units of 45–60 min, every week), (O) whole-body vibration training (seven units every week), and (O) inspiratory muscle training (seven 21-min units every week).

Comprehensive patient education ([M] one-week asthma course [seven 45-min teaching units (TUs) during one week]), (M) practical application training for inhaled medication and peak flow meter training (one 60-min TU), (O) education for allergy sufferers (one 60-min TU).

(M) Group breathing physiotherapy (three 45-min units every week); if necessary, also (O) individual breathing physiotherapy. Optional respiratory therapy techniques were (O) Buteyko breathing technique for patients with dysfunctional breathing patterns, and participation in (O) a respiratory physiotherapy seminar on cough techniques for patients with chronic dry cough. In addition, in the case of mucostasis, further (O) special inhalation therapies (brine inhalation, oscillating ultrasonic pressure nebulizer) and other physical therapy measures were offered.