Abstract

Early definitive airway protection and normoventilation are key principles in the treatment of severe traumatic brain injury. These are currently guided by end tidal CO2 as a proxy for PaCO2. We assessed whether the difference between end tidal CO2 and PaCO2 at hospital admission is associated with in-hospital mortality. We conducted a retrospective observational cohort study of consecutive patients with traumatic brain injury who were intubated and transported by Helicopter Emergency Medical Services to a Level 1 trauma center between January 2014 and December 2019. We assessed the association between the CO2 gap—defined as the difference between end tidal CO2 and PaCO2—and in-hospital mortality using multivariate logistic regression models. 105 patients were included in this study. The mean ± SD CO2 gap at admission was 1.64 ± 1.09 kPa and significantly greater in non-survivors than survivors (2.26 ± 1.30 kPa vs. 1.42 ± 0.92 kPa, p < .001). The correlation between EtCO2 and PaCO2 at admission was low (Pearson's r = .287). The mean CO2 gap after 24 h was only 0.64 ± 0.82 kPa, and no longer significantly different between non-survivors and survivors. The multivariate logistic regression model showed that the CO2 gap was independently associated with increased mortality in this cohort and associated with a 2.7-fold increased mortality for every 1 kPa increase in the CO2 gap (OR 2.692, 95% CI 1.293 to 5.646, p = .009). This study demonstrates that the difference between EtCO2 and PaCO2 is significantly associated with in-hospital mortality in patients with traumatic brain injury. EtCO2 was significantly lower than PaCO2, making it an unreliable proxy for PaCO2 when aiming for normocapnic ventilation. The CO2 gap can lead to iatrogenic hypoventilation when normocapnic ventilation is aimed and might thereby increase in-hospital mortality.

Subject terms: Diseases, Medical research

Introduction

Treatment recommendations in traumatic brain injury (TBI) include early definitive airway protection as well as normoventilation with a target arterial partial pressure of CO2 (PaCO2) of 4.6–5.9 kPa (35–45 mmHg)1,2. The effects of hypo- or hyperventilation on cerebral blood flow (CBF), with the potential for hypoxemia or hyperemia of cerebral tissue and their negative impact on outcome, have been widely studied3–7. Using PaCO2 to monitor ventilation requires arterial blood gas (ABG) analyses, but the necessary lab equipment is not yet widely available in the prehospital environment. Therefore end-tidal CO2 (EtCO2) determined by capnography has been used as a surrogate marker to estimate PaCO2 assuming a reliable correlation between EtCO2 and PaCO28.

Capnography is considered the gold standard, both to determine correct placement of a definitive airway and to guide ventilation during emergency care9,10. The assumed correlation between EtCO2 and PaCO2 has been known to be accompanied by a tension difference of CO2 ranging anywhere between 0.26 and 0.66 kPa (2 and 5 mmHg) in otherwise healthy individuals undergoing anesthesia11–16. However, major trauma accompanying TBI can negatively influence ventilation and perfusion, making the interpolation of PaCO2 from EtCO2 in trauma patients unreliable17–19. As expected, subgroup analyses have shown the best correlation between EtCO2 and PaCO2 in isolated TBI when compared to other trauma patients20.

The primary aim of this study is to describe the correlation between EtCO2 and PaCO2 at the time of admission in patients hospitalized with TBI. Furthermore, we investigated the predictive value of tension difference of CO2 between EtCO2 and PaCO2 (CO2 gap) for in-hospital mortality.

Methods

Study participants, setting and ethics approval

This retrospective observational single-center cohort study included all consecutive patients with TBI who were intubated on the scene and transported by the helicopter emergency medical service (HEMS) (Swiss Air-Rescue, Rega) to a Level 1 trauma center (Kantonsspital St. Gallen, Switzerland) between January 1st of 2014 and December 31st of 2019. Exclusion criteria were patients who were not intubated before admission, patients with traumatic injuries requiring intubation for other reasons than TBI, and secondary transport missions including patients with traumatic brain injury who were transported from another hospital to this trauma center.

The local ethics committee of St. Gallen (EKOS) granted permission to use patient data without individual consent according to the federal act on research involving human beings and the ordinance on human research with the exception of clinical trials. The permission also covered the use of patient data regarding the HEMS operation (EKOS St. Gallen 7.7.2020, BASEC Nr. 2020-01737 EKOS 20/122).

Data and definitions

Baseline characteristics of patients were obtained from electronic hospital records. Laboratory findings were obtained by automated retrieval using the unique patient identification number in the hospital records. EtCO2 was measured using main-stream capnographs (ZOLL Medical Corporation, Chelmsford, USA). Information on the ventilator settings at admission was prospectively entered into the patients' electronic hospital records.

Outcome information (i.e., survival status) was documented prospectively as part of the routine electronic hospital records and obtained from the corresponding record.

The Injury Severity Score Thorax was determined at admission. EtCO2, systolic blood pressure, pulse and SpO2 were recorded on admission to the Emergency Room (ER) as well as 24 h after admission.

Statistics

Patients’ characteristics were summarized and presented in tables. Continuous variables were summarized by mean ± SD (standard deviation) if normally distributed or by median and IQR (interquartile range) if skewed. Normality was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Categorical variables were summarized with counts and percentages for each level of the variable. Outliers were assessed using the Grubbs test for continuous variables if normally distributed.

Correlation between EtCO2 and PaCO2 was assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient and visualized using a scatter plot. Disagreement between EtCO2 and PaCO2 was visualized using a Bland–Altman plot21. To assess the impact of the time interval between the initial arterial blood gas sample and the first recorded EtCO2 at admission, a linear regression was conducted.

Differences in the CO2 gap between survivors and non-survivors were tested using the Mann–Whitney-Wilcoxon Test. The association between the CO2 gap and the in-hospital mortality was further assessed using univariate and multivariable logistic regression models. To minimize confounding, variables potentially associated with the respiratory system and in-hospital mortality were defined a priori based on a literature review and clinical experience22. The variables included age, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, peripheral capillary oxygen saturation, pressure of oxygen in arterial blood (paO2), and severity of chest injury documented by the ISS (Injury Severity Score) thoracic sub-score. All variables were coded as continuous variables. Complete case analyses were performed due to the low number of missing data and therefore the low risk of bias.

Two-sided p-values of < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R Studio 3.6.0 on macOS 10.15.7.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The local ethics committee of St. Gallen (EKOS) granted permission to use patient data without individual consent according to the federal act on research involving human beings and the ordinance on human research with the exception of clinical trials. The permission also covered the use of patient data regarding the HEMS operation (EKOS St. Gallen 7.7.2020, BASEC Nr. 2020–01737 EKOS 20/122).

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was waived as per the ethics approval.

Results

This study adheres to the STROBE Statement (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology)23. From January 2014 to December 2019 a total of 181 patients were admitted to our trauma center by HEMS after TBI and intubation. Seventy-six patients were excluded. Reasons were mechanisms of injury besides TBI, an alternate reason for unconsciousness, missing ISS, EtCO2 or PaCO2 data, or early extubation in the ER.

Of the 105 patients admitted to the ICU, 28 (27%) died and 77 (73%) were discharged alive. Information on neurological function at discharge was not available.

The patients’ baseline characteristics are displayed in Table 1. Of note, non-survivors were on average more than 20 years older than survivors and had a lower PaO2 in the initial blood gas samples, p < 0.001.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients.

| Variable | Overall n = 105 |

Survivors n = 77 |

Non-survivors n = 28 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 49.5 ± 22.6 | 43.4 ± 21.0 | 66.3 ± 18.1 |

| Age < 18 years, n (%) | 9 (9) | 8 (10) | 1 (4) |

| Male gender, n (%) | 71 (68) | 51 (66) | 20 (71) |

| ISS Total, median (IQR) | 25 (17 to 34) | 25 (14 to 34) | 31 (25 to 38) |

| ISS = 75, n (%) | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (4) |

| ISS Thorax, median (IQR) | 0 (0 to 2) | 0 (0 to 2) | 0 (0 to 2) |

| Missing (ISS Thorax), n (%) | 12 (11) | 9 (12) | 3 (11) |

| Cardiopulmonary parameters | |||

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 127 ± 33 | 127 ± 29 | 125 ± 43 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 78 ± 28 | 80 ± 30 | 72 ± 21 |

| Pulse, bpm | 93 ± 26 | 92 ± 24 | 93 ± 32 |

| SpO2, median (IQR) | 100 (98 to 100) | 100 (98 to 100) | 99.5 (94.8 to 100) |

| Temperature, °C | 35.9 ± 0.93 | 35.9 ± 0.93 | 35.9 ± 0.98 |

| Missing, n (%) | 16 | 11 | 5 |

| Arterial blood gas | |||

| pH, median (IQR) | 7.31 (7.26 to 7.35) | 7.31 (7.28 to 7.36) | 7.31 (7.19 to 7.33) |

| BE, mmol/l median (IQR) | − 3.6 (− 6.4 to − 1.9) | − 3.6 (− 5.8 to − 1.7) | − 4.9 (− 8.4 to − 2.3) |

| HCO3−, mmol/l median (IQR) | 21.9 (19.9 to 23.6) | 21.5 (20.5 to 23.6) | 21.1 (19.6 to 23.4) |

| Lactate, mmol/l median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.2 to 3.4) | 1.9 (1.2 to 2.7) | 2.8 (1.4 to 4.5) |

| PaCO2, kPa median (IQR) * | 6.0 (5.5 to 6.8) | 5.9 (5.5 to 6.6) | 6.4 (5.7 to 6.8) |

| PaO2, kPa median (IQR) | 28.2 (17.6 to 48.9) | 34.3 (19.6 to 51.5) | 23.1 (14.9 to 29.8) |

| Hemoglobin, g/l | 122 ± 21 | 122 ± 20 | 119 ± 24 |

| Glucose, mmol/l median (IQR) | 8.0 (6.3 to 10.1) | 7.5 (6.0 to 8.9) | 10.2 (8.1 to 13.2) |

Data was complete if not otherwise specified. Continuous variables are reported as mean ± SD = (standard deviation) if normally distributed and not stated otherwise.

BP blood pressure, IQR interquartile range, ISS injury severity score, bpm beats per minute, SpO2 peripheral capillary oxygen saturation.

*PaCO2 = same parameter as shown in detail on Table 2 (initial measure).

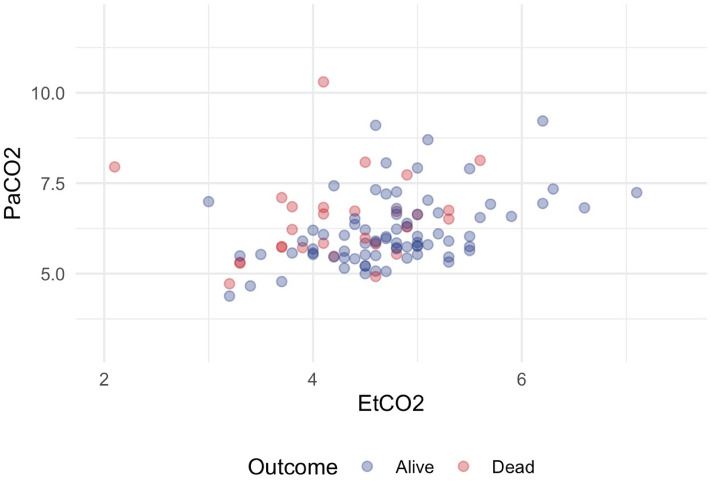

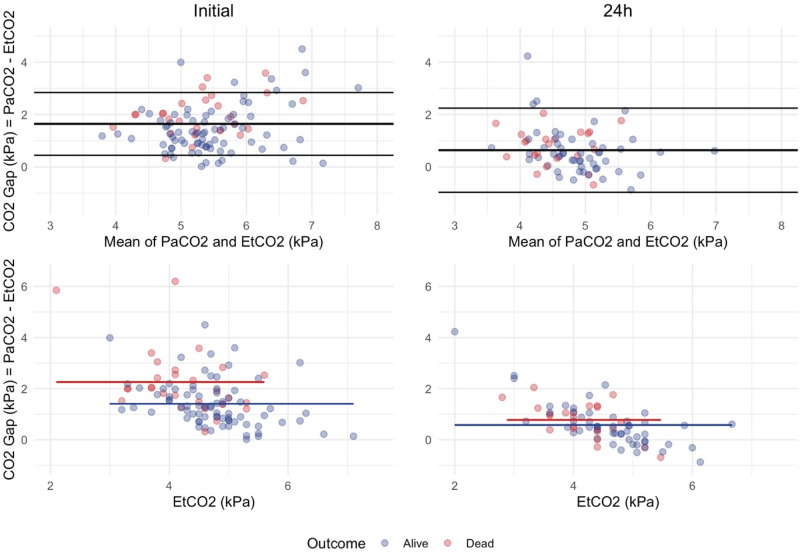

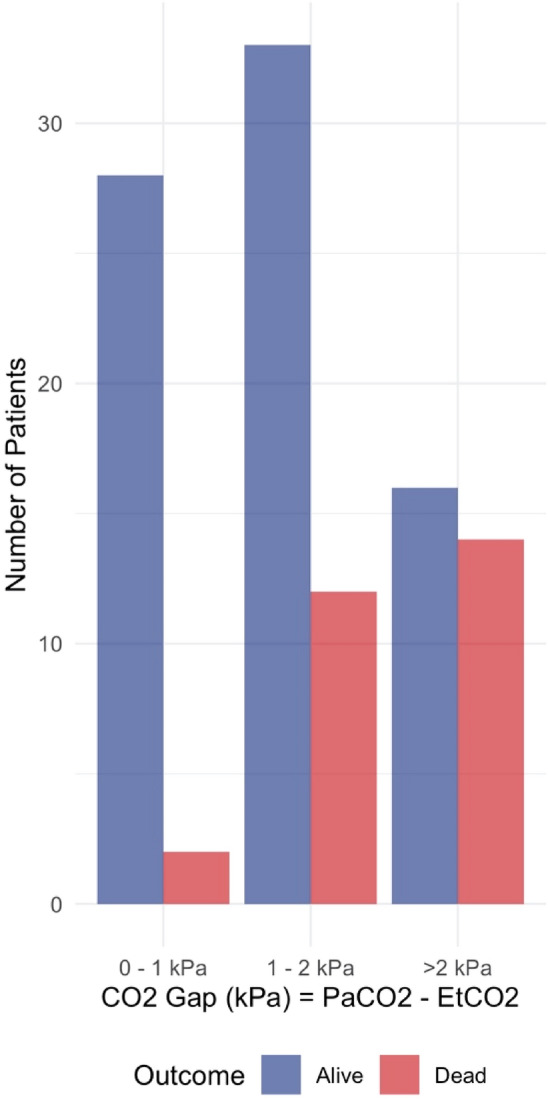

The correlation between EtCO2 and PaCO2 at admission was low, Pearson's r = 0.287, Fig. 1. There was a significant difference between EtCO2 and PaCO2 at admission. The overall mean CO2 gap at admission was 1.64 ± 1.09 kPa and significantly larger in non-survivors than survivors, 2.26 ± 1.30 kPa vs. 1.42 ± 0.92 kPa, p < 0.001, see Table 2 and Figs. 2 and 3. The majority of EtCO2 and PaCO2 pairs were obtained within 30 min, n = 60, 57%. However, there was no significant association between the time intervals of the first arterial blood gas sampling and the first documented EtCO2 on the CO2 gap in a univariate linear regression, p = 0.165.

Figure 1.

Correlation of PaCO2 and EtCO2. Pearson's correlation coefficient overall r = 0.287, for survivors r = 0.438, for non-survivors r = 0.150. PaCO2 and EtCO2 in kPa. Figure was created using RStudio (2020). RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA URL http://www.rstudio.com/ and the package ggplot2 by Wickham H (2016).

Table 2.

PaCO2 and EtCO2 pairs at admission and after 24 h.

| Variable | Overall n = 105 |

Survivors n = 77 |

Non-survivors n = 28 |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial measures | 105 (100) | 76 (99) | 28 (100) | |

| CO2 gap, kPa | 1.64 ± 1.09 | 1.42 ± 0.92 | 2.26 ± 1.30 | < 0.001 |

| PaCO2, kPa | 6.26 ± 1.03 | 6.17 ± 0.96 | 6.48 ± 1.18 | |

| EtCO2, kPa | 4.61 ± 0.78 | 4.76 ± 0.74 | 4.23 ± 0.76 | |

| PaCO2 < 15 min of EtCO2 | 42 (40) | 30 (39) | 13 (46) | |

| PaCO2 < 30 min of EtCO2 | 60 (57) | 39 (51) | 21 (75) | |

| PaCO2 ≥ 30 min of EtCO2 | 45 (43) | 38 (49) | 7 (25) | |

| Measures at 24 h | 75 (71) | 53 (70) | 22 (79) | |

| CO2 gap, kPa | 0.64 ± 0.82 | 0.58 ± 0.86 | 0.78 ± 0.70 | 0.108 |

| PaCO2, kPa | 5.12 ± 0.60 | 5.19 ± 0.59 | 4.91 ± 0.58 | |

| EtCO2, kPa | 4.46 ± 0.79 | 4.59 ± 0.82 | 4.15 ± 0.63 | |

| Hours since admission | 18.6 ± 7.8 | 19 ± 8.0 | 17.7 ± 7.5 |

Data was complete. Numbers are presented with percentages of total in parentheses. Continuous variables are reported as mean ± SD (standard deviation). The CO2 gap and the PaCO2 variables were skewed; however, the mean ± SD was presented due to the use of these parameters in the Bland–Altman plots. CO2 gap = PaO2—EtCO2.

For the measures at 24 h there was no time delay measurement of EtCO2 and PaCO2.

Figure 2.

Bland–Altman plots and point plots comparing PaCO2 and EtCO2. Top row: Bland–Altman plots for all available pairs of PaCO2 and EtCO2 at different time points. Bottom row: corresponding point plots for the same data. The red and blue lines illustrate the mean CO2 gap for deceased and surviving patients, respectively. The mean CO2 gap lines are trimmed, illustrating the EtCO2 range for both groups, respectively. Difference between PaCO2 and EtCO2 was highly significant for the initial pairs (p < 0.001) but not for the pairs after 24 h (see Table 2). Figures were created using RStudio (2020). RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA URL http://www.rstudio.com/ and the package ggplot2 by Wickham H (2016).

Figure 3.

Bar diagram showing survival for CO2 gap groups. Bar diagram showing outcome by groups of CO2 gap measured initially. Figure was created using RStudio (2020). RStudio: integrated development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA URL http://www.rstudio.com/ and the package ggplot2 by Wickham H (2016).

The overall CO2 gap decreased to 0.64 ± 0.82 kPa at 24 h after admission and was no longer significantly different between non-survivors and survivors, 0.78 ± 0.70 kPa vs. 0.58 ± 0.86, p = 0.108, see Table 2 and Fig. 2.

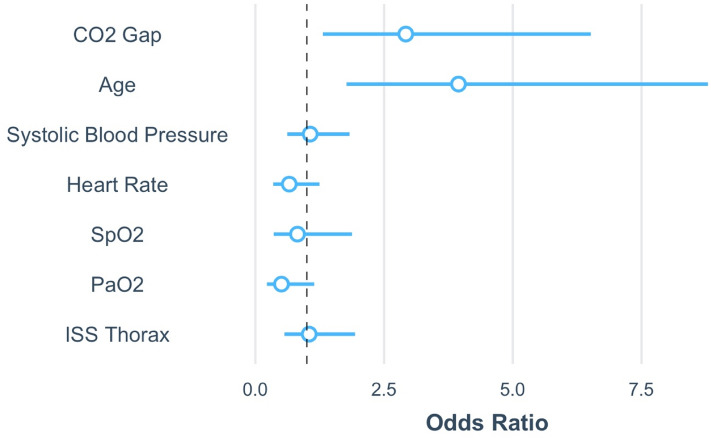

The multivariate logistic regression model showed that the CO2 gap was independently associated with increased mortality in intubated and mechanically ventilated patients with TBI. For every increase of the CO2 gap by 1 kPa, mortality was 2.7 times higher, OR 2.692, 95% CI 1.293–5.646, p = 0.009. Higher age was independently associated with an increased mortality rate as well, OR 1.842 for every increase of 10 years, 95% CI 1.106–2.641, p = 0.001. Systolic blood pressure, heart rate, thoracic trauma, SpO2 and PaO2 were not associated with survival status in this multivariate model, see Table 3 and Fig. 4. Inclusion of further parameters from the arterial blood gas samples (ABG samples), the total ISS, or other cardiopulmonary parameters in the regression model led to multicollinearity; these parameters were therefore excluded from the final model.

Table 3.

Logistic regression models of survival.

| Variable | Univariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR | 95% CI of OR | Std. Err | p value | |

| CO2 gap, kPa | 2.044 | 1.299–3.219 | 0.232 | 0.002 |

| Age, year | 1.059 | 1.030–1.088 | 0.014 | < 0.001 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 0.998 | 0.985–1.011 | 0.007 | 0.750 |

| Pulse, bpm | 1.001 | 0.984–1.018 | 0.009 | 0.909 |

| SpO2, % | 0.948 | 0.875–1.025 | 0.039 | 0.171 |

| PaO2, kPa | 0.974 | 0.950–0.998 | 0.013 | 0.038 |

| ISS Thorax | 1.077 | 0.796–1.457 | 0.154 | 0.629 |

| Variable | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR | 95% CI of OR | Std. err | p value | |

| CO2 gap, kPa | 2.692 | 1.283–5.646 | 0.385 | 0.009 |

| Age, year | 1.063 | 1.026–1.102 | 0.018 | 0.001 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 1.002 | 0.986–1.018 | 0.008 | 0.822 |

| Pulse, bpm | 0.984 | 0.960–1.009 | 0.013 | 0.199 |

| SpO2, % | 0.960 | 0.810–1.137 | 0.106 | 0.635 |

| PaO2, kPa | 0.966 | 0.926–1.007 | 0.022 | 0.101 |

| ISS thorax | 1.030 | 0.683–1.554 | 0.214 | 0.887 |

Figure 4.

Scaled regression coefficient of the multivariate logistic regression. Illustration of the multivariate logistic regression model summarized on Table 3. Regression coefficients are exponentiated and scaled. The horizontal lines around the dots indicates the 95% confidence interval of the odds ratio. CO2 gap = PaO2—EtCO2. Figure was created using RStudio (2020). RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA URL http://www.rstudio.com/. and the package ggplot2 by Wickham H (2016).

Discussion

Our results show that end-tidal capnography is an unreliable tool for monitoring and targeting invasive ventilation at least in the initial treatment of patients with severe TBI. Although the majority of the patients in this study were ventilated within the target range of EtCO2 values, many were unwittingly hypercapnic in the first blood gas sample after arriving in the hospital. Our data show a large variability in the calculated CO2 gap in this patient cohort and it was more pronounced in patients with lower EtCO2. This underestimation of PaCO2 when EtCO2 was used to guide ventilation caused hypoventilation despite normal EtCO2 values. An increased CO2 gap and the resulting hypercapnia were associated with increased in-hospital mortality. This underlines the clinical importance of these findings and the need for either a more reliable surrogate parameter for PaCO2 estimation or early PaCO2 sampling in the prehospital management of patients with TBI.

The CO2 gap

Previous studies have observed that the CO2 gap is multifactorial, with possible causes including ventilation-perfusion mismatch, increased dead space, or, shock with impaired perfusion and temperature11,24. However, most of these factors influencing the CO2 gap are not measurable, detectable or predictable in the initial treatment period in the field or ER. The ability to predict or gauge the CO2 gap based on the patient’s condition is consequently limited. In this context the CO2 gap might be both, an indicator of severity of injury, and a predictor of impaired survival in patients with severe traumatic brain injury.

Two recent publications investigated the CO2 gap in critically ill patients after prehospital emergency anesthesia25,26. Their findings are in line with our results and showed only moderate correlation between EtCO2 and PaCO2, confirming that EtCO2 alone should be used with caution to guide ventilation in the critically ill.

This was further strengthened by our data wherein, the CO2 gap (visualized as mean bias on the Bland–Altman plots) was more pronounced in patients with lower EtCO2 values demonstrating that patients with EtCO2 measures within the target range (4.6–5.9 kPa) were unwittingly hypercapnic.

In a cohort of cardiac arrest patients, Suominen et al. showed an association between an increased CO2 gap and in-hospital mortality 24 h after return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC). Our data is in line with these findings and reinforces the plausibility of this association by controlling for potential confounding due to shock or hypoperfusion in a multivariate logistic regression model.

EtCO2 as a surrogate marker

PaCO2 is considered to be the major determinant of cerebral blood flow (CBF) through its effects on cerebral vascular tone27. This reinforces the importance of precise ventilatory control in the initial management of TBI. It is known that even modest hypercapnia can result in substantial increases in ICP and can cause dangerous cerebral ischemia when intracranial compliance is poor28. Therefore, we hypothesize that the hypoventilation due to underestimation of the arterial CO2 using EtCO2 as a surrogate marker leads to impaired CBF and thereby increases mortality.

Recent TBI guidelines rely on the assumption that the CO2 gap is approximately 0.5 kPa (3.8 mmHg). However, these assumptions are based on data of individuals undergoing general anesthesia without major comorbidities or trauma11,29. In this study, the mean first EtCO2 was 4.6 ± 0.78 kPa, whereas the mean PaCO2 was 6.26 ± 1.03 kPa and far in excess of the target of 4.5–5.0 kPa. Therefore, relying on EtCO2 as a surrogate for PaCO2 provides a false sense of security, and providers may not achieve optimal prehospital PaCO2. At present, no reliable alternative to direct ABG sampling seems to exist in order to approximate PaCO2 reliably.

However, to our best knowledge, there is no data supporting the routine use of point-of-care blood gas analyses in patients mechanically ventilated in the field. This lack of data could be due to the fact that up to now the importance of point-of-care testing in prehospital care has been underestimated, due to the high reliance on proxy markers like EtCO2. Further studies on the optimal timing of sampling after intubation and the beginning of mechanical ventilation, as well as the optimal sampling interval, are needed. We postulate that a single ABG sample post-intubation could gauge the individual CO2 gap and ensure more reliable EtCO2-guided ventilation.

Factors influencing mortality

Our data showed a significant age difference between survivors and non-survivors. Age was independently and significantly associated with mortality. Besides the fact that age might be a surrogate for unrecognized confounders due to comorbidities that negatively influence mortality, clinical decision-making may also play a role. In daily routine, palliation might be considered at an earlier stage in elderly trauma victims with limited rehabilitation potential, whereas younger trauma patients may receive maximum therapeutic interventions30.

In our cohort, systolic blood pressure and ISS thorax scores were not significantly associated with mortality in the multivariate analysis.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, it is a retrospective and single-center cohort study with a limited sample size. However, data was almost complete and multivariate adjustments were performed. Second, in order to increase the number of eligible patients in this study, we included patients who had an ABG sample up to 30 min after hospital arrival. However, a sensitivity analysis showed that the observed gradient between EtCO2 and PaCO2 was not significantly associated with the time between arterial blood gas sampling and the documented EtCO2. Still, it is possible that a proportion of the gradient between EtCO2 and PaCO2 was due to changes in ventilation settings during this period. Furthermore, if this time difference was longer than 15 min apart there was no second set of hemodynamic data to statistically evaluate at these two different timepoints.

Lastly, ventilation mode selected in the preclinical setting was not taken into account in analysis of the data. We cannot exclude bias through varying influence of ventilation mode on dead space.

Conclusions

The CO2 gap is an inconsistent phenomenon in pre-hospital anesthetized TBI patients, making EtCO2 an unreliable proxy for PaCO2 when aiming for normocapnic ventilation. The higher-than-expected CO2 gap can lead to iatrogenic hypoventilation when normocapnic ventilation is aimed for and might thereby increase in-hospital mortality."

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Patrick Münger for assistance in acquiring data from the electronic hospital records, Qendi Marku for assistance in acquiring outcome data from electronic hospital records, Mario Tissi and Marlis Planzer for assistance in acquiring data from the HEMS Database and Jeannie Wurz for careful editing of the manuscript.

Author contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to all of the following: (1) the conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, (3) final approval of the version to be submitted. U.P., L.M and P.D designed the study. P.D and U.P performed Data collection. L.M performed statistical analysis. U.P., L.M and P.D drafted and finalized the manuscript. S.J.M.S., M.F., J.K., A.E and R.A reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors have approved the manuscript and agree with its submission. We confirm that this manuscript has not been published elsewhere and is not under consideration by another journal.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Pascal Doppmann and Lorenz Meuli.

References

- 1.Abdelmalik PA, Draghic N, Ling GSF. Management of moderate and severe traumatic brain injury. Transfusion. 2019;59:1529–1538. doi: 10.1111/trf.15171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Volovici V, Steyerberg EW, Cnossen MC, Haitsma IK, Dirven CMF, Maas AIR, et al. Evolution of evidence and guideline recommendations for the medical management of severe traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2019;36:3183–3189. doi: 10.1089/neu.2019.6474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muizelaar JP, Marmarou A, Ward JD, Kontos HA, Choi SC, Becker DP, et al. Adverse effects of prolonged hyperventilation in patients with severe head injury: A randomized clinical trial. J. Neurosurg. 1991;75:731–739. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.75.5.0731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouma GJ, Muizelaar JP. Cerebral blood flow, cerebral blood volume, and cerebrovascular reactivity after severe head injury. J. Neurotrauma. 1992;9(Suppl 1):S333–S348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouma GJ, Muizelaar JP. Cerebral blood flow in severe clinical head injury. New Horiz. 1995;3:384–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stein NR, McArthur DL, Etchepare M, Vespa PM. Early cerebral metabolic crisis after TBI influences outcome despite adequate hemodynamic resuscitation. Neurocrit. Care. 2012;17:49–57. doi: 10.1007/s12028-012-9708-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis DP, Idris AH, Sise MJ, Kennedy F, Eastman AB, Velky T, et al. Early ventilation and outcome in patients with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Crit. Care Med. 2006;34:1202–1208. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000208359.74623.1C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maeda T, Yoshino A, Katayama Y. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury: Updated in 2013. Japanese J. Neurosurg. 2013;22:831–836. doi: 10.7887/jcns.22.831. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frerk C, Mitchell VS, McNarry AF, Mendonca C, Bhagrath R, Patel A, et al. Difficult Airway Society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults. Br. J. Anaesth. 2015;115:827–848. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Checketts MR. AAGBI recommendations for standards of monitoring during anaesthesia and recovery 2015. Anaesthesia. 2016;71:470–471. doi: 10.1111/anae.13421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fletcher R, Jonson B. Deadspace and the single breath test for carbon dioxide during anaesthesia and artificial ventilation: Effects of tidal volume and frequency of respiration. Br. J. Anaesth. 1984;56:109–119. doi: 10.1093/bja/56.2.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujimoto S, Suzuki M, Sakamoto K, Ibusuki R, Tamura K, Shiozawa A, et al. Comparison of end-tidal, arterial, venous, and transcutaneous pco2. Respir Care. 2019;64:1208–1214. doi: 10.4187/respcare.06094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shankar KB, Moseley H, Vemula V, Ramasamy M, Kumar Y. Arterial to end-tidal carbon dioxide tension difference during anaesthesia in early pregnancy. Can. J. Anaesth. 1989;36:124–127. doi: 10.1007/BF03011432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Onodi C, Bühler PK, Thomas J, Schmitz A, Weiss M. Arterial to end-tidal carbon dioxide difference in children undergoing mechanical ventilation of the lungs during general anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2017;72:1357–1364. doi: 10.1111/anae.13969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiller J, Silvers A, McIlroy DR, Niggemeyer L, White S. A retrospective observational study examining the admission arterial to end-tidal carbon dioxide gradient in intubated major trauma patients. Anaesth. Intensive Care. 2010;38:302–306. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1003800212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Law GTS, Wong CY, Kwan CW, Wong KY, Wong FP, Tse HN. Concordance between side-stream end-tidal carbon dioxide and arterial carbon dioxide partial pressure in respiratory service setting. Hong Kong Med J. 2009;15:440–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yosefy C, Hay E, Nasri Y, Magen E, Reisin L. End tidal carbon dioxide as a predictor of the arterial PCO2 in the emergency department setting. Emerg. Med. J. 2004;21:557–559. doi: 10.1136/emj.2003.005819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belpomme V, Ricard-Hibon A, Devoir C, Dileseigres S, Devaud M-L, Chollet C, et al. Correlation of arterial PCO2 and PETCO2 in prehospital controlled ventilation. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2005;23:852–859. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prause G, Hetz H, Lauda P, Pojer H, Smolle-Juettner F, Smolle J. A comparison of the end-tidal-CO2 documented by capnometry and the arterial pCO2 in emergency patients. Resuscitation. Ireland. 1997;35:145–148. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9572(97)00043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warner KJ, Cuschieri J, Garland B, Carlbom D, Baker D, Copass MK, et al. The utility of early end-tidal capnography in monitoring ventilation status after severe injury. J. Trauma. Inj. Infect. Crit. Care. 2009;66:26–31. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181957a25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin Bland J, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. Elsevier. 1986;327:307–310. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)90837-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang JT, Erickson SL, Killien EY, Mills B, Lele AV, Vavilala MS. Agreement between arterial carbon dioxide levels with end-tidal carbon dioxide levels and associated factors in children hospitalized with traumatic brain injury. JAMA Netw. Open. 2019;2:e199448. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.9448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suominen PK, Stayer S, Wang W, Chang AC. The effect of temperature correction of blood gas values on the accuracy of end-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring in children after cardiac surgery. ASAIO J. 2007;53:670–674. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e3181569bf3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Price J, Sandbach DD, Ercole A, Wilson A, Barnard EBG. End-tidal and arterial carbon dioxide gradient in serious traumatic brain injury after prehospital emergency anaesthesia: A retrospective observational study. Emerg. Med. J. 2020;1:209077. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2019-209077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harve-Rytsälä H, Ångerman S, Kirves H, Nurmi J. Arterial and end-tidal carbon dioxide partial pressure difference during prehospital anaesthesia in critically ill patients. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2020;1:13751. doi: 10.1111/aas.13751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogoh S. Interaction between the respiratory system and cerebral blood flow regulation. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019;1:1197–1205. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00057.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steiner LA, Balestreri M, Johnston AJ, Coles JP, Smielewski P, Pickard JD, et al. Predicting the response of intracranial pressure to moderate hyperventilation. Acta Neurochir. 2005;147:477–483. doi: 10.1007/s00701-005-0510-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nunn JF, Hill DW. Respiratory dead space and arterial to end-tidal carbon dioxide tension difference in anesthetized man. J. Appl. Physiol. 1960;15:383–389. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1960.15.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fiorentino, M., Hwang, F., Pentakota, S. R., Livingston, D. H., Mosenthal, A. C. Palliative care in trauma: not just for the dying. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. [Internet]. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2019 [cited 2020 Dec 11]. p. 1156–63. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31658239/ [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.