Abstract

Objective: To explore the effect of accelerated rehabilitation nursing in patients after gastric cancer surgery. Methods: This prospective study included 88 gastric cancer patients who scheduled to receive surgery. According to the random number table, these patients were assigned to the control group and the experimental group. Patients in the control group received routine nursing, while those in the experimental group received accelerated rehabilitation nursing. Clinical-related parameters, nutritional index, physiological state, the quality of life (QOL), and complications were compared between the two groups. Results: Compared with the control group, postoperative time to get out of bed, anal exhaust time, recovery time of bowel sound, and the length of hospitalization were shortened (all P<0.05). Hemoglobin (Hb), serum total protein (TP), and albumin (Alb) level in both groups after intervention were significantly lower than those before intervention (all P<0.05). Meanwhile, Hb, serum TP, and Alb level in the experimental group after intervention were significantly higher than those in the control group (all P<0.05). Visual analogue scale (VAS) scores at different time points (12 h-5 d after surgery) in the experimental group were significantly reduced when compared with the control group (all P<0.05). Hamilton anxiety scale (HAMA) and Hamilton depression scale (HAMD) score in the two groups after intervention were markedly lower those before intervention (both P<0.05). At the same time, HAMA and HAMD score in the experimental group after intervention were lower than those in the control group (both P<0.05). Generic quality of life inventory-74 (GQOLI-74) scores in all aspects after intervention were higher than those before intervention (all P<0.05). Meanwhile, GQOLI-74 scores in all aspects in the experimental group after intervention were higher than those in the control group (all P<0.05). The total incidence of complications in the experimental group was significantly decreased when compared with the control group (P<0.05). Conclusion: For gastric cancer patients undergoing surgical treatment, accelerated rehabilitation nursing care can effectively promote their postoperative recovery of intestinal function, significantly improve their nutritional status, relieve their negative emotions, improve their quality of life, and reduce the incidence of complications. It is worth of clinical application.

Keywords: Accelerated rehabilitation nursing, gastric cancer, psychological status, nutritional status, complications

Introduction

Gastric cancer is a common clinical malignant tumor of the digestive tract. At present, surgery is still the essential treatment. However, the structure of gastrointestinal tract is complex. Accordingly, it is difficult to conduct the surgery. In addition, there are many postoperative complications, influencing postoperative recovery [1,2]. Reasonable rehabilitation nursing plays an important role in accelerating the prognosis of patients. Accelerated rehabilitation nursing is a novel model. In the nursing, patients-centered service is emphasized. Its aim is to reduce or block patients’ physiological stress response during the perioperative period through multidisciplinary collaborations in nursing, anesthesia, nutrition, and so on. Eventually, postoperative rehabilitation is accelerated [3]. Gastric cancer is a wasting disease, with most patients accompanied by malnutrition. Additionally, the postoperative recovery of gastrointestinal tract is slow. Therefore, the postoperative nutritional status of patients after gastric cancer surgery has a direct influence on their prognosis. Postoperative nutritional status is thus supposed to be a routine inspection indicator [4]. In recent years, there have been many reports on the application of accelerated rehabilitation nursing in patients with gastrointestinal tumors. Most of these reports are on complications and prognosis [5,6]. On the basis of previous evaluation indicators, we also observed indicators like nutritional status, psychological status, and the quality of life.

Materials and methods

General information

This prospective study was conducted in 88 gastric cancer patients who scheduled to undergo surgery in Affiliated Hospital of Jiangsu University from January 2019 to February 2020. According to the random number table, these patients were allocated to the control group and the experimental group. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Affiliated Hospital of Jiangsu University.

Inclusion criteria: Patients were diagnosed with gastric cancer; patients aged between 20 and 75 years; imaging examination displayed no signs of distant metastasis; patients would like to receive elective surgery; patients had no radiotherapy and chemotherapy before enrollment; patients signed the informed consent.

Exclusion criteria: Patients had dysfunctions of important organs like cardiopulmonary, liver, and kidney; patients had distant metastases; patients needed an urgent surgery for comorbidities such as intestinal obstruction and gastric perforation; patients participated in other research projects.

Methods

Patients in both groups were offered with enteral nutrition support in the early postoperative period. On the first day after surgery, 250 mL of 5% glucose and sodium chloride injection (Hubei Zhongjia Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., China) was pumped through the naso-intestinal tube. The volume of enteral nutrition injection pumped had been gradually increased since the second day after surgery. The pumping rate of nutrient solution was ceased or slowed down when there were discomforts such as diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting [7].

During the perioperative period, patients in the control group received routine nursing. Various examinations were taken after admission. Before surgery, patients received 6 h of fasting and water deprivation. During the operation, the drip speed was controlled. After surgery, patients’ vital signs were closely monitored. They were asked to press the abdomen carefully when they had coughing. By doing so, worsened pain, which was caused by increased abdominal pressure, was avoided. For patients with more obvious pain, painkillers were applied to lighten the pain. Furthermore, patients after surgery were instructed on diet.

Patients in the experimental group received accelerated rehabilitation nursing from admission to discharge. Specifically, it consisted of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative nursing. (1) Preoperative nursing: on the first day before surgery, nursing staff explained the necessity and effectiveness of surgical treatment to patients and their family members. The importance of cooperating with medical staff was notified to patients with plain language. Before surgery, patients received 6h of fasting and water deprivation. To avoid postoperative hunger, they were allowed to drink 200 mL of brown sugar water or glucose water 2 h before surgery [8]. (2) Intraoperative nursing: during the operation, patients were kept warm. The flushing solution and disinfectant were appropriately heated to 37°C. The infusion volume and liquid infusion speed were controlled to avoid patients’ discomfort, which was induced by the rapid infusion. (3) Postoperative nursing included 4 aspects. Firstly, pain nursing: after surgery, a self-controlled intravenous analgesic pump was implemented to relieve patients’ pain. For patients with severe pain, a volume of 2 mL pethidine injection (50 mg/mL, Yichang Renfu Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., China) was intramuscularly injected to ease their pain. Secondly, psychological nursing: when patients had poor psychological status or obvious emotional fluctuations, nursing staff or professional psychological counselors would provide targeted psychological counseling in time to enhance their self-confidence; nursing staff talked with patients gently, and alleviated their unstable emotions through face-to-face communication. As a result, their anxiety symptoms were eliminated. Thirdly, exercise rehabilitation nursing: nursing staff asked patients to perform rehabilitation activities as early as possible after the operation. After 6 hours of anesthesia, patients were supposed to change position, move limbs, and turn over. On the 1st day after the operation, they tried to get out of bed. On the 2nd day after the operation, they tried to stand up and walk slowly and gently. Attention was paid to the amount of exercise. According to patients’ condition, the amount of exercise was increased appropriately [9]. Lastly, during enteral nutrition support, patients were instructed to turn over frequently to promote bowel movement and avoid discomforts like abdominal distension.

Outcome measures

Main outcome measures

Clinical-related parameters, like postoperative time to get out of bed, anal exhaust time, recovery time of bowel sound, and the length of hospitalization, were compared between the two groups.

Nutritional index before and 7 d after intervention were compared between the two groups. Specifically, hemoglobin (Hb), serum total protein (TP), and albumin (Alb) level were measured using an automatic blood cell analyzer (Shenzhen Kubeier Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China).

Visual analogue scale (VAS) was used to evaluate postoperative pain at different time points [10]. The higher the score was, the severer the pain.

Secondary outcome measures

Patients were instructed to re-examine in Affiliated Hospital of Jiangsu University 2 months after discharging. Also, they were required to fill in relevant evaluation scales. For patients failed to receive reexamination in time, telephone follow-up was taken. Correspondingly, scales were filled in by nursing staff.

Hamilton anxiety scale (HAMA) and Hamilton depression scale (HAMD) were applied to assess anxiety and depression, respectively [10,11]. The higher the HAMA score, the severer the anxiety was. Similarly, the higher the HAMD score, the severer the depression was.

Generic quality of life inventory-74 (GQOLI-74) was implemented to evaluate the quality of life [12]. The higher the score, the better the quality of life was.

Complications, such as deep vein thrombosis in lower limbs, pulmonary infection, postoperative incision infection, and urinary tract infection, were compared between the two groups. The total incidence of complications = the number of complications/the total number of patients * 100%.

Statistical methods

All data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software version 20.0. The enumeration data were expressed as number/percentage (n/%); comparison was conducted with chi-square test. The measurement data were calculated as mean ± standard deviation (x̅ ± sd); independent sample t test was used for inter-group comparison, while paired t-test was applied for before-after comparison within the same group. The difference was statistically significant when P value was less than 0.05.

Results

Baseline data

There were no significant differences on general information between the two groups (Table 1, all P>0.05).

Table 1.

Baseline data (n, x̅ ± sd)

| Group | Experimental group (n=44) | Control group (n=44) | χ2/t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (n) | 1.137 | 0.286 | ||

| Male | 25 | 20 | ||

| Female | 19 | 24 | ||

| Age (years) | 54.5±5.4 | 55.2±6.0 | 0.575 | 0.567 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.45±2.04 | 23.18±2.38 | 0.571 | 0.569 |

| Course of disease (years) | 3.34±1.03 | 3.63±1.20 | 1.216 | 0.227 |

| Tumor site (n) | 0.845 | 0.480 | ||

| Stomach fundus | 18 | 20 | ||

| Cardia | 15 | 13 | ||

| Gastric body | 7 | 6 | ||

| Gastric antrum | 4 | 5 | ||

| TNM staging (n) | 0.760 | 0.684 | ||

| Stage l | 20 | 16 | ||

| Stage ll | 16 | 19 | ||

| Stage lll | 8 | 9 | ||

| Operation method (n) | 1.137 | 0.286 | ||

| Gastrointestinal short circuit or Spivack | 24 | 19 | ||

| Radical surgery | 20 | 25 | ||

| Operation time (min) | 78.69±6.96 | 76.97±7.44 | 1.120 | 0.266 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 184.48±30.50 | 180.64±28.47 | 0.610 | 0.543 |

| Pathology (n) | 0.210 | 0.900 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 29 | 27 | ||

| Adenosquamous carcinoma | 10 | 11 | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 5 | 6 |

Note: BMI: body mass index.

Clinical-related parameters

Postoperative time to get out of bed, anal exhaust time, recovery time of bowel sound, and the length of hospitalization in the experimental group were shortened when compared with the control group (Table 2, all P<0.05).

Table 2.

Clinical-related parameters

| Group | Postoperative time to get out of bed (h) | Anal exhaust time (h) | Recovery time of bowel sound (h) | The length of hospitalization (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental group (n=44) | 22.23±5.40# | 30.05±5.49# | 25.47±4.39# | 9.49±2.20# |

| Control group (n=44) | 32.68±4.34 | 39.98±5.03 | 35.50±6.33 | 15.59±2.57 |

Note: Compared with control group;

P<0.05.

Nutrition index

As shown in Table 3, Hb, TP, and Alb level in both groups after intervention were lower than those before intervention (all P<0.05); Hb, TP, and Alb level in the experimental group after intervention were higher than those in the control group (all P<0.05).

Table 3.

Nutrition index (x̅ ± sd, g/L)

| Group | Time | Hb | TP | Alb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental group (n=44) | Before intervention | 101.45±7.59 | 61.26±4.39 | 38.70±3.95 |

| After intervention | 94.48±6.58*,# | 57.48±6.29*,# | 35.44±3.88*,# | |

| Control group (n=44) | Before intervention | 100.37±6.96 | 60.94±5.23 | 38.20±4.22 |

| After intervention | 91.10±5.40* | 54.85±5.55* | 33.17±3.29* |

Note: Hb: hemoglobin; TP: serum total protein; Alb: albumin. Compared with before intervention;

P<0.05.

Compared with control group;

P<0.05.

VAS score

VAS scores at different time points (12 h-5 d after surgery) in the experimental group were significantly lower than those in the control group (Table 4, all P<0.05).

Table 4.

VAS score (x̅ ± sd, score)

| Group | 12 h after surgery | 24 h after surgery | 3 d after surgery | 5 d after surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental group (n=44) | 5.06±1.10# | 4.33±0.78# | 3.20±0.59# | 2.77±0.56# |

| Control group (n=44) | 5.56±0.95 | 5.06±0.66 | 3.98±0.61 | 3.55±0.60 |

Note: VAS: visual analogue scale. Compared with control group;

P<0.05.

HAMA and HAMD score

As displayed in Table 5, HAMA and HAMD score in the two groups after intervention were lower those before intervention (both P<0.05); HAMA and HAMD score in the experimental group after intervention were lower than those in the control group (both P<0.05).

Table 5.

HAMA and HAMD score (x̅ ± sd, score)

| Group | Time | HAMA score | HAMD score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental group (n=44) | Before intervention | 9.86±1.29 | 8.05±1.04 |

| After intervention | 6.78±1.20*,# | 6.04±1.02*,# | |

| Control group (n=44) | Before intervention | 9.56±1.32 | 8.32±1.19 |

| After intervention | 8.84±1.04* | 7.02±1.10* |

Note: HAMA: Hamilton anxiety scale; HAMD: Hamilton depression scale. Compared with before intervention;

P<0.05.

Compared with control group;

P<0.05.

GQOLI-74 score

As shown in Table 6, GQOLI-74 scores in all aspects after intervention were higher than those before intervention (all P<0.05); GQOLI-74 scores in all aspects in the experimental group after intervention were higher than those in the control group (all P<0.05).

Table 6.

GQOLI-74 score (x̅ ± sd, score)

| Group | Time | Social function | Physical function | Physiological function | Material life state |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental group (n=44) | Before intervention | 66.69±5.40 | 70.07±6.50 | 67.78±5.04 | 56.50±5.90 |

| After intervention | 75.59±5.86*,# | 78.96±5.07*,# | 79.97±5.70*,# | 69.96±5.85*,# | |

| Control group (n=44) | Before intervention | 67.25±5.49 | 69.89±5.96 | 68.10±5.48 | 57.11±5.84 |

| After intervention | 70.06±6.50* | 74.49±5.88* | 75.55±5.20* | 63.39±6.40* |

Note: GQOLI-74: generic quality of life inventory-74. Compared with before intervention;

P<0.05.

Compared with control group;

P<0.05.

Complications

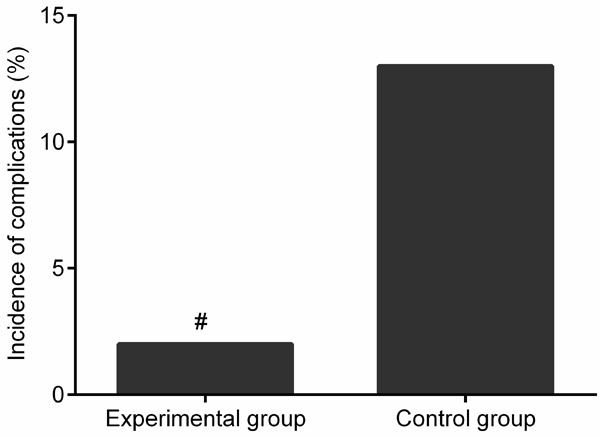

The total incidence of complications in the experimental group, which was composed of pulmonary infection (1 cases) was significantly lower than that in the control group (2.27% vs. 13.64%, χ2=3.880, P<0.05, Figure 1), which consisted of deep vein thrombosis in lower limbs (1 cases), pulmonary infection (1 cases), postoperative incision infection (2 cases), and urinary tract infection (2 cases).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the incidence of complications. Compared with control group, #P<0.05.

Discussion

Before surgery, most patients with gastrointestinal tumors need to fast. However, long-term fasting can cause stomach upset. It was reported that fasting for more than 48 hours could cause gastrointestinal mucosal dysfunction [13,14]. The absorption of nutrients is decreased when the permeability of mucosa is reduced, which is not conducive to the postoperative recovery of patients. If patients are instructed to turn over frequently to promote bowel movement during enteral nutrition support, discomforts like abdominal distension would be declined [15,16]. Perioperative nursing also plays a critical role in the postoperative recovery of patients. In our study, postoperative time to get out of bed, anal exhaust time, recovery time of bowel sound, and the length of hospitalization in the experimental group were shorter than those of the control group, indicating that accelerated rehabilitation nursing can effectively promote the postoperative recovery of intestinal function and shorten the length of hospitalization. Gao et al. also reported that rapid recovery could shorten postoperative time to get out of bed and significantly improve intestinal function in patients with gastric cancer. In their opinion, this might be related to the hypothesis that rapid recovery could reduce physiological stress response to certain extent [17].

Most gastric cancer patients are accompanied by malnutrition, which can aggravate the perioperative stress response and further reduce the body’s immunity. As a result, patients’ prognosis is postponed [18]. Some scholars have proposed that patients with gastrointestinal tumors should be provided with postoperative nutritional support as early as possible. The support can not only offer the required nutrients, but also reduce the stomach discomfort [19]. Gastric cancer surgery is highly traumatic. Thus, it takes a long time to recovery after the operation. Postoperative early enteral nutrition support provides sufficient nutrients for gastric cancer patients undergoing surgery. It is beneficial for the improvement of the body’s immunity and acceleration of prognosis. Cheng et al. also reported that early enteral nutrition support could significantly enhance the cellular immune function of patients underwent radical gastric cancer surgery, improve their nutritional status, and decrease their risk of postoperative complications [20]. In our study, VAS score at different time points (12 h-5 d after surgery) in the experimental group were significantly declined when compared with the control group. Hb, TP, and Alb level in both groups after intervention were lower than those before intervention. Meanwhile, Hb, TP, and Alb level in the experimental group after intervention were higher than those in the control group. These results denote that accelerated rehabilitation nursing can effectively relieve the postoperative pain of gastric cancer patients and improve their postoperative nutritional status.

Patients with malignant tumors are troubled by various factors such as the disease, cancer pain, and high medical expenses. As a result, they are often accompanied by different degrees of negative emotions. It was confirmed that preoperative anxiety was extremely detrimental to the recovery of patients [21]. Zemła et al. also reported that immediate and effective psychological counseling was very important for patients with negative emotions [22]. Accelerated rehabilitation nursing emphasizes the psychological care of patients and strengthens patients’ self-confidence by targeted psychological counseling. With face-to-face communication, patients’ unstable emotions are effectively declined, and their anxiety symptoms are eliminated. Finally, they are able to confront the disease under optimal mental state. In this case, related treatments are actively accepted. Our results displayed that HAMA and HAMD score in the experimental group after intervention were lower than those in the control group, suggesting that accelerated rehabilitation nursing can effectively improve the postoperative negative emotions of gastric cancer patients. Accordingly, their anxiety and depression are relieved. Annika et al. found that accelerated rehabilitation nursing could effectively improve the postoperative anxiety symptoms of patients with gastric cancer, which was consistent with our results [23].

Psychological care of patients is emphasized in accelerated rehabilitation nursing. Therefore, the anxiety symptoms of patients after surgery are effectively relieved. Early exercise rehabilitation nursing can not only contribute to the recovery of patients’ gastrointestinal function, but also the reduction of complications, like thrombus in the deep veins of lower extremities. The prognosis of patients is accelerated through many aspects. Ultimately, their quality of life is improved [24]. In our study, GQOLI-74 scores in all aspects in the experimental group after intervention were higher than those in the control group, indicating that accelerated rehabilitation nursing can effectively improve the postoperative life quality of gastric cancer patients. It was consistent with the results reported by Sagar et al. [25]. In terms of complications, the total incidence of complications in the experimental group was significantly lower than that in the control group, suggesting that accelerated rehabilitation nursing can effectively reduce the incidence of postoperative complications in patients with gastric cancer.

However, this is a single-center study performed in a limited number of patients. Moreover, the follow-up time is just 2 months. A multi-center study will be conducted in a large number of patients, with follow-up time more than 1 year. Such that, the long-term effect of accelerated rehabilitation nursing care on these indicators in patients undergoing gastric cancer surgery can be verified.

In summary, the application of accelerated rehabilitation nursing care in gastric cancer patients undergoing surgical treatment is beneficial for the effectively accelerated postoperative recovery of intestinal function, significantly improved nutritional status, relieved negative emotions, increased quality of life, and reduced complications. It is worthy of clinical application.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Song Z, Wu Y, Yang J, Yang D, Fang X. Progress in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer. Tumour Biol. 2017;39:1010428317714626. doi: 10.1177/1010428317714626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsukamoto T, Nakagawa M, Kiriyama Y, Toyoda T, Cao X. Prevention of gastric cancer: eradication of helicobacter pylori and beyond. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1699–1704. doi: 10.3390/ijms18081699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright AR, Richardson AB, Kikuchi CK, Goldberg DB, Marumoto JM, Kan DM. Effectiveness of accelerated recovery performance for post-ACL reconstruction rehabilitation. Hawaii J Health Soc Welf. 2019;78:41–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiuchi J, Komatsu S, Kosuga T, Kubota T, Okamoto K, Konishi H, Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Ichikawa D, Otsuji E. Long-term postoperative nutritional status affects prognosis even after infectious complications in gastric cancer. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:3133–3138. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bu J, Li N, Huang X, He S, Wen J, Wu X. Feasibility of fast-track surgery in elderly patients with gastric cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:1391–1398. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2839-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang SH, Lee Y, Min SH, Park YS, Ahn SH, Park DJ, Kim HH. Multimodal enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) program is the optimal perioperative care in patients undergoing totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a prospective, randomized, clinical trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:3231–3238. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6625-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herbert G, Perry R, Andersen HK, Atkinson C, Penfold C, Lewis SJ, Ness AR, Thomas S. Early enteral nutrition within 24 hours of lower gastrointestinal surgery versus later commencement for length of hospital stay and postoperative complications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;10:Cd004080. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004080.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tokunaga M, Sato Y, Nakagawa M, Aburatani T, Matsuyama T, Nakajima Y, Kinugasa Y. Perioperative chemotherapy for locally advanced gastric cancer in Japan: current and future perspectives. Surg Today. 2020;50:30–37. doi: 10.1007/s00595-019-01896-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Melick N, van Cingel RE, Brooijmans F, Neeter C, van Tienen T, Hullegie W, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW. Evidence-based clinical practice update: practice guidelines for anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation based on a systematic review and multidisciplinary consensus. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:1506–1515. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zimmerman M, Martin J, Clark H, McGonigal P, Harris L, Holst CG. Measuring anxiety in depressed patients: a comparison of the hamilton anxiety rating scale and the DSM-5 anxious distress specifier interview. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;93:59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raimo S, Trojano L, Spitaleri D, Petretta V, Grossi D, Santangelo G. Psychometric properties of the hamilton depression rating scale in multiple sclerosis. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:1973–1980. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-0940-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou Y, Zhou R, Li W, Lin Y, Yao J, Chen J, Shen T. Controlled trial of the effectiveness of community rehabilitation for patients with schizophrenia in Shanghai, China. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2015;27:167–174. doi: 10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.215026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rynders CA, Thomas EA, Zaman A, Pan Z, Catenacci VA, Melanson EL. Effectiveness of intermittent fasting and time-restricted feeding compared to continuous energy restriction for weight loss. Nutrients. 2019;11:2442–2447. doi: 10.3390/nu11102442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ismail S, Manaf RA, Mahmud A. Comparison of time-restricted feeding and islamic fasting: a scoping review. East Mediterr Health J. 2019;25:239–245. doi: 10.26719/emhj.19.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pash E. Enteral nutrition: options for short-term access. Nutr Clin Pract. 2018;33:170–176. doi: 10.1002/ncp.10007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song J, Zhong Y, Lu X, Kang X, Wang Y, Guo W, Liu J, Yang Y, Pei L. Enteral nutrition provided within 48 hours after admission in severe acute pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e11871. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao L, Zhao Z, Zhang L, Shao G. Effect of early oral feeding on gastrointestinal function recovery in postoperative gastric cancer patients: a prospective study. J Buon. 2019;24:194–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirov KM, Xu HP, Crenn P, Goater P, Tzanis D, Bouhadiba MT, Abdelhafidh K, Kirova YM, Bonvalot S. Role of nutritional status in the early postoperative prognosis of patients operated for retroperitoneal liposarcoma (RLS): a single center experience. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2019;45:261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garla P, Waitzberg DL, Tesser A. Nutritional therapy in gastrointestinal cancers. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2018;47:231–242. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2017.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng Y, Zhang J, Zhang L, Wu J, Zhan Z. Enteral immunonutrition versus enteral nutrition for gastric cancer patients undergoing a total gastrectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:11. doi: 10.1186/s12876-018-0741-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stamenkovic DM, Rancic NK, Latas MB, Neskovic V, Rondovic GM, Wu JD, Cattano D. Preoperative anxiety and implications on postoperative recovery: what can we do to change our history. Minerva Anestesiol. 2018;84:1307–1317. doi: 10.23736/S0375-9393.18.12520-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zemła AJ, Nowicka-Sauer K, Jarmoszewicz K, Wera K, Batkiewicz S, Pietrzykowska M. Measures of preoperative anxiety. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2019;51:64–69. doi: 10.5603/AIT.2019.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Heymann-Horan A, Bidstrup P, Guldin MB, Sjøgren P, Andersen EAW, von der Maase H, Kjellberg J, Timm H, Johansen C. Effect of home-based specialised palliative care and dyadic psychological intervention on caregiver anxiety and depression: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Cancer. 2018;119:1307–1315. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0193-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sagar RC, Kumar KVV, Ramachandra C, Arjunan R, Althaf S, Srinivas C. Perioperative artificial enteral nutrition in malnourished esophageal and stomach cancer patients and its impact on postoperative complications. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2019;10:460–464. doi: 10.1007/s13193-019-00930-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Düzgün İ, Baltacı G, Turgut E, Atay OA. Effects of slow and accelerated rehabilitation protocols on range of motion after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2014;48:642–648. doi: 10.3944/AOTT.2014.13.0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]