Abstract

Purpose

To assess the current national rate of medial ulnar collateral ligament (MUCL) repair of the elbow and delineate the patient demographics of those undergoing repair.

Methods

A retrospective review and analysis of a national private insurance database was conducted covering 2007-2017 using Pearl Diver technologies. All patients diagnosed with a MUCL injury and those who underwent repair were included using Clinical Modification and Current Procedural Terminology code 24345, referencing repair of the ulnar collateral ligament of the elbow with local tissue. The extracted data included patient age at time of procedure, sex, race, region, year of surgery, insurance type, hospital setting, and any associated diagnoses with 90 days of the repair procedure. Standard descriptive methods characterized our study sample to calculate frequency counts and percentages. Means with respective standard deviations and/or standard errors, and 95% confidence intervals were calculated and reported for continuous variables, whereas frequencies and percentages were reported for categorical variables. Pearson χ2 tests were used to determine differences between group proportion categorical variables. Significance was considered at a P ≤ .05.

Results

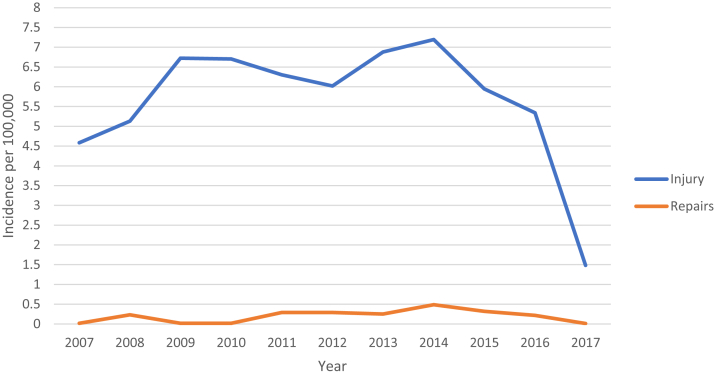

From 2007 to 2014, MUCL injuries showed an upward trend in incidence per 100,000 from 4.59 to 7.19 (56% increase) within the database population. Accordingly, the incidence of MUCL repair rose from 0.016 to 0.49 (2962%). However, from 2015-2017 there was a drop in both categories, as injury incidence fell from 7.19 to 1.48 whereas repair rates dropped from 0.49 to 0.012. The ages undergoing repair show a significant peak in 15-24-year-olds. The incidence of MUCL repair was greatest in the West and South (P < .01). Male patients had a greater incidence of MUCL injury, and a greater incidence of MUCL repair per 100,000 persons compared to females (P < .01).

Conclusions

MUCL repair has emerged as a viable alternative to reconstruction in select indications. The impetus for this change may be to provide a quicker return to sport and fewer complications, largely due to recent improvements in surgical technique for MUCL repair. As anticipated, the incidence of MUCL repair had steadily increased in the United States from 2007 to 2014, with a subsequent relatively inexplicable decrease primarily in 2017, according to the database utilized in this study. The 15-24 year-old age group encompassing young athletes has the greatest incidence of repair by a significant margin.

Level of Evidence

IV, Therapeutic Case Series.

The medial ulnar collateral ligament (MUCL) is the primary stabilizer of the elbow and resists valgus forces on the elbow joint.1,2 MUCL injuries frequently are encountered as part of complex elbow trauma; however, they are commonly investigated in the literature as a sports-related injury. The MUCL experiences significant stresses during overhead-throwing sports such as baseball, football, and gymnastics and can be commonly injured resulting in valgus instability, and thus the bulk of the outcome research is focused on this injury in athletic populations.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Once considered to be a catastrophic injury, particularly for overhead athletes wishing to return to their sport, surgical management of MUCL injuries has proven to yield high return to sport rates.2,3 MUCL reconstruction (i.e., “Tommy John surgery”) was first described in 1986 by Jobe et al, and has for decades been considered the gold standard due to early reports of superior outcomes compared with MUCL repair.4, 5, 6 However, early studies demonstrating inferior results with MUCL repair compared with reconstruction were focused primarily on professional-level athletes.5, 6, 7 Recently, a number of surgeons have since revisited MUCL repair, with promising results. Furthermore, recent studies have demonstrated similar biomechanical properties of MUCL repair augmented with internal bracing compared with those of reconstruction.8,9

With appropriate patient selection, several authors have shown MUCL repair also can provide excellent outcomes, including greater return to sport rates and shorter rehabilitation times compared with reconstruction.10, 11, 12, 13, 14 Furthermore, MUCL repair eliminates the risk for donor-site complications such as wound infection, postoperative weakness, damage to neurovascular structures, and erroneous graft harvest.11

Even as MUCL repair becomes more common, much of the literature on the patient demographics and operation rates of MUCL injury focuses on reconstruction, with trends in repair remaining understudied.15,16 In the wake of studies reflecting renewed interest in MUCL repair and improved surgical technique, the purpose of this study was to assess the current national rate of MUCL repair of the elbow and delineate the patient demographics of those undergoing repair. We hypothesized that with the renewed interest in repair and recent publications that we would see in increase in the rate of MUCL repair with a similar demographic profile to that of MUCL reconstruction.

Methods

A retrospective review was conducted of all MUCL repair procedures performed between the years 2007-2017 using the PearlDiver technologies (Colorado Springs, CO) National Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act−compliant database. All patients diagnosed with a MUCL injury and those who underwent repair were included using both the corresponding International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Editions, and Clinical Modification and Current Procedural Terminology code 24345, referencing repair of the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) of the elbow with local tissue. All included International Classification of Diseases codes can be found in the Appendix Table 1. The extracted data included patient age at time of procedure, sex, race (unknown, White, Black, Hispanic, other), region of the country procedure was performed (Midwest, Northeast, South, West), state procedure was performed in, year of surgery, insurance type (Medicare, Medicaid, private), hospital setting procedure was performed in (inpatient/outpatient hospital, surgery center), and any associated diagnoses with 90 days of the repair procedure. For incidence calculation, subcategory patient numbers were available in the PearlDiver system for analysis. Standard descriptive methods characterized our study sample to calculate frequency counts and percentages. Means with respective standard deviations and/or standard errors, and 95% confidence intervals were calculated and reported for continuous variables, whereas frequencies and percentages were reported for categorical variables. Pearson χ2 tests were used to determine differences between group proportion categorical variables. Significance was considered at a P ≤ .05. All statistical comparisons were carried out using Minitab 19 Statistical Software (State College, PA). Not all subcategory information was available in PearlDiver system for each patient.

Results

Between 2007 and 2017, there were 4920 MUCL injuries and a total of 216 patients underwent repair. The majority of repairs occurred between 2011 and 2016, with a peak of 47 in 2014 and correlating to a 1-year incidence of 0.49 per 100,000. From 2007 to 2014, MUCL injuries showed an upward trend in incidence per 100,000 from 4.59 to 7.19 (56% increase) and accordingly the incidence of MUCL repairs rose from 0.016 to 0.49 (2,962%). However, from 2015 to 2017, there was a drop in both categories, as injury incidence fell from 7.19 to 1.48 whereas repair rates dropped from 0.49 to 0.012 (Fig 1). The greatest rate of repair was found in 2014 at 6.77% of injuries, which was significantly greater than in 2007, 2009, 2010, 2013, 2016, and 2017 (P < .01).

Fig 1.

MUCL injury incidence and repair rates by year from 2007-2017. (MUCL, medial ulnar collateral ligament.)

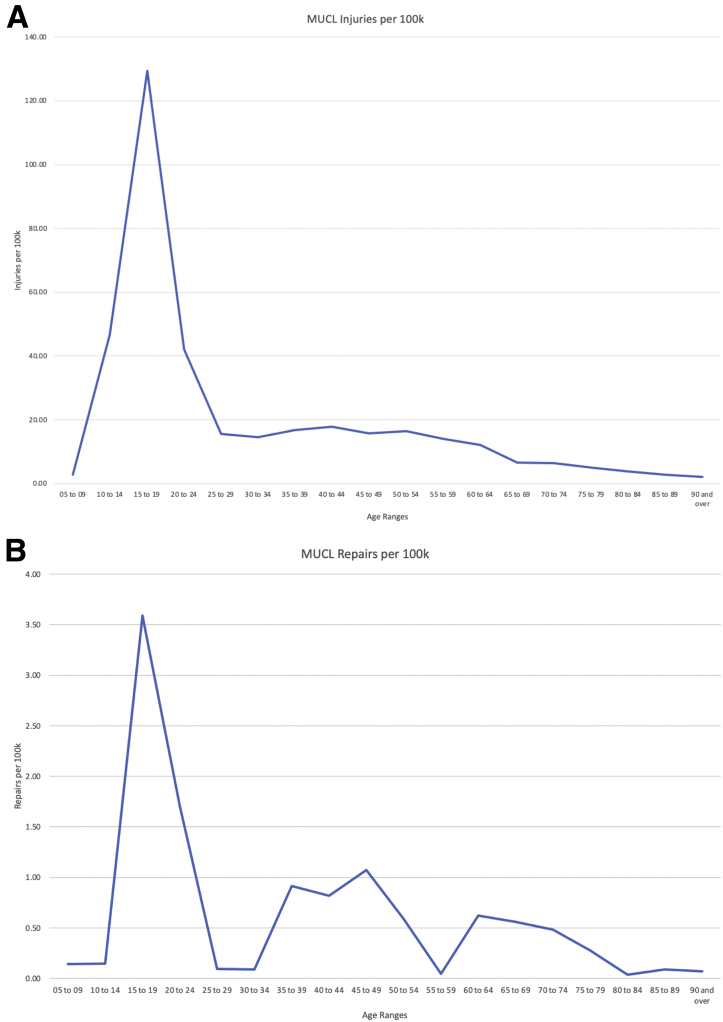

Of the repairs, the sex was provided for 217 patients, with 115 (60%) being female and 102 (40%) male. Male patients more commonly sustained MUCL injuries and the incidence of repair per 100,000 persons was greater in male compared with female patients (incidence of 0.93% vs 0.81% per 100,000; P = .003). The age groups undergoing repair showed a significant spike in ages 15-24 as expected, with substantially smaller peaks found in 45- to 49- and 60- to 64-year-old groupings. Age distribution of injury and repairs can be found in Fig 2. There was no significant difference in the quarter of the year that repairs were performed. The majority of procedures, 61.6%, were performed in the South followed by 19.4% in the Midwest and 18.5% in the West, although the West region had the greatest incidence by a statistically significant margin from the others. Of the listed races, White patients comprised 38.8% of the patients, whereas 59.7% were listed as unknown. A total of 69 patients (36.9%) underwent concomitant ulnar nerve transposition; however, age-level data were not available for this cohort. The bulk of the transpositions were performed in the Southern United States (58%) or the Midwest (25%). There was no sex difference in transposition incidence and age data were incompletely reported for this procedure. There were 18 readmissions within 90 days of the repair, with only 1 (0.46%) potentially correlated to the UCL repair, which was for a postoperative wound infection. Notably, 30% of the UCL repairs studied carried an associated fracture or dislocation of the elbow. For complete results, please refer to Table 1.

Fig 2.

(A) Age distribution of MUCL Injury; (B) age distribution of MUCL repair. (MUCL, medial ulnar collateral ligament.)

Table 1.

Subgroup Analysis of MUCL Injury Incidence and Repair Rates by Demographics per 100,000

| UCL Injury | Sample Population | Injury Incidence | UCL Repair | Sample Population | Repair Incidence | P Value∗ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | |||||||

| Midwest | 1114 | 6,077,878 | 18.33 | 42 | 6,077,878 | 0.69 | <.001 |

| Northeast | 64 | 2,032,657 | 3.15 | 1 | 2,032,657 | 0.05 | |

| South | 2867 | 13,453,980 | 21.31 | 133 | 13,453,980 | 0.99 | |

| West | 462 | 3,597,396 | 12.84 | 40 | 3,597,396 | 1.11 | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 1937 | 14,045,160 | 13.79 | 115 | 14,045,160 | 0.82 | .003 |

| Male | 2569 | 10,989,067 | 23.38 | 102 | 10,989,067 | 0.93 |

NOTE. Boldface indicates statistical significance.

MUCL, medial ulnar collateral ligament; UCL, ulnar collateral ligament.

P value corresponds to intracategorical repair incidence.

Discussion

The most important finding of this large database study is that the incidence of MUCL injuries was on the rise in the younger high school and college patient population between 2007 and 2014. Correspondingly, there was an increase in MUCL repair performed nationwide during that same period. Repairs also were more common in male versus female patients. Interestingly, a steep decline in injury incidence and rates of repairs from 2015 to 2017 occurred. Previous small cohort studies on surgical management of MUCL injuries list demographic information about those who have undergone MUCL repair.10,12,13,17 The overwhelming majority of these patients were young, male baseball players, although sports such as football and softball, among others, were also represented. Of note, those in early studies such as Conway et al.5 were relatively older patients playing primarily at professional level, whereas those in later studies such as Richard et al.,12 Savoie et al.,13 and Dugas et al.10 tended to be younger patients playing at collegiate, high school, and even junior high school levels.

Regarding the significant drop off in both injuries and repairs observed between 2015 and 2017, the majority of this is due to the 2017 figures, which is the last year included in the database. There is no indication in the literature as to why this significant drop-off would have occurred during this time frame, and therefore makes the finding less likely to have external validity. While there was a corresponding drop by more than 2 million patients in the 2017 sample population, you would expect a proportional drop in the injury and repair rates, but that was not reflected in the data. There is a potential for significant changes in the demographic make-up of the insured patients during this year or issues within the database in the most recent year of collection; however, this is speculatory and cannot be substantiated.

Ligament reconstruction has been regarded as the gold standard treatment for surgical MUCL injuries and has a track record of success at all levels of sport.18,19 With its widespread use has come opportunities to study the patient trends in reconstruction longitudinally to determine whether there have been shifts in the patient demographics in response to both changes in surgical technique or preventative efforts.15 With the recent surgical advances in MUCL repair, reflected in both biomechanical testing and case series, there is reason to believe that the number of operations is trending upward.8,20 It is theorized that in younger overhead athletes there is a lack of the chronic attritional damage and secondary changes involving the nonligamentous parts of the elbow that are common among professional athletes, which may allow an elbow to be more amenable to repair.13,21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 In these younger patients, the injury more commonly involves either the proximal and/or distal portion of the ligament as opposed to the widespread damage more commonly observed in professional overhead throwing athletes.13 Within this population, results have indicated direct suture repair of the MUCL complex can restore valgus stability, decrease soft-tissue dissection, and preserve bone in comparison with reconstruction enabling reliable and rapid recovery.12,13,17 Furthermore, there is no need to wait for graft incorporation, which accelerates the recovery timetable. In addition, the previously poor outcomes with MUCL repair in professional athletes has not been reproduced in younger and lower-level athletes. With appropriate patient selection, outcomes for MUCL repair have substantially improved with one study quoting a return to play (RTP) of close to 97% within 6 months postoperative and a second study of 111 overhead athletes showing a RTP rate of 92% within 6.7 months.10,13 Compare this with the typical RTP after reconstruction of 83% at a mean of 11.6 months (range 3-72 months) and one can see why this is such a promising development,12 Furthermore, both series present major strides from the initial study Conway et al.5 in 1992 that reported a RTP rate after MUCL repair of 71.4%.5

The increase in MUCL repairs being performed from year to year rose at a rate faster than the increase in injury incidence (2692 vs 56% from 2007-2014), indicating a possible shift in treatment algorithms. The incidence of MUCL repair increased significantly over the majority of the study period, with a peak seen in 2014. The data reflect a 1-year statistically significant spike in 2008, with a second significant sustained spike in incidence from 2011 to 2016, although year-to-year changes were not significant over this period. These dates appear to coincide with increased examples of successful MUCL repairs reported in the literature.12,13,17

As previous studies have shown successful results after MUCL repair for young nonprofessional athletes, our data showed a predictable spike in patients aged 15 to 24 years coincides with the at-risk high school and collegiate aged group. However, we also saw spikes in the mid-40s and early 60s, albeit significantly smaller, which likely reflect patients with MUCL injuries secondary to traumatic falls where repair of the UCL for instability was indicated. This is supported by the fact that greater than 30% of the UCL repairs studied carried an associated fracture or dislocation of the elbow.

Regionally, the majority of the repairs were performed in the south in number; however, the West region had the greatest incidence by a statistically significant margin from the others. This regionality bias can be in part be attributed to the greatest risk activity and the weather patterns. Previous studies have shown that baseball players in warm weather areas undergo UCL surgery at greater rates than others, as players in this region are more able to play year around and the same can be extrapolated to the repair cohort.28 In addition, one of the major centers for UCL surgery is located in the South and has historically been a high-volume center for UCL reconstruction.15

The most common associated procedure identified in the data was an ulnar nerve transposition. There was a total of 69 ulnar nerve transpositions performed on the UCL repair cohort, representing 37% of the total. The decision of whether to perform an ulnar nerve transposition is based on multiple factors, including whether the patient is symptomatic at the time of UCL injury, but also may be done prophylactically to avoid a potential future procedure, as studies have cited ulnar nerve neuropraxia of 6.7% to 12% after MUCL reconstruction.29,30 A 2019 study by Erickson et al.31 reviewed isolated ulnar nerve transposition in 52 Major League Baseball players for ulnar nerve neuropraxia, 14 of whom had previous MUCL reconstruction. The authors demonstrated a return to sport rate of only 62%, showing the importance of avoiding this complication if possible.

Limitations

There are significant limitations to this study that are primarily based on the database used, which is composed of privately insured patients and not necessarily representative of the general population. In addition to sampling bias, this study relies on correct coding at the time of procedure for accurate data retrieval from the database, which could lead to either over- or underestimation of the injury prevalence. There is also no patient-level data presented from the database; therefore, missing pieces of information such as individual demographic factors (age, sex, race, etc.) cannot be tracked or excluded on a case-by-case basis. The lack of patient row level data also prevents the use of greater-level statistics that require this information. The significant injury and repair incidence changes in 2017 without clear explanation limit the external validity of this portion of the data.

Conclusions

MUCL repair has emerged as a viable alternative to reconstruction in select indications. The impetus for this change may be to provide a quicker return to sport and fewer complications, largely due to recent improvements in surgical technique for MUCL repair. As anticipated, the incidence of MUCL repair had steadily increased in the United States from 2007 to 2014, with a subsequent relatively inexplicable decrease primarily in 2017, according to the database utilized in this study. The 15- to 24-year-old age group encompassing young athletes has the highest incidence of repair by a significant margin.

Footnotes

The authors report that they have no conflicts of interest in the authorship and publication of this article. Full ICMJE author disclosure forms are available for this article online, as supplementary material.

Supplementary Data

Appendix

Appendix Table 1.

All Included Codes

| Code ICD-10-D-S5330XA | International Classification of Diseases Traumatic rupture of unspecified ulnar collateral ligament initial encounter |

| Code ICD-10-D-S5330XD | Traumatic rupture of unspecified ulnar collateral ligament subsequent encounter |

| Code ICD-10-D-S5331XA | Traumatic rupture of right ulnar collateral ligament initial encounter |

| Code ICD-10-D-S5331XD | Traumatic rupture of right ulnar collateral ligament subsequent encounter |

| Code ICD-10-D-S5331XS | Traumatic rupture of right ulnar collateral ligament sequela |

| Code ICD-10-D-S5332XA | Traumatic rupture of left ulnar collateral ligament initial encounter |

| Code ICD-10-D-S5332XD | Traumatic rupture of left ulnar collateral ligament subsequent encounter |

| Code ICD-10-D-S5332XS | Traumatic rupture of left ulnar collateral ligament sequela |

| Code ICD-10-D-S53441A | Ulnar collateral ligament sprain of right elbow initial encounter |

| Code ICD-10-D-S53441D | Ulnar collateral ligament sprain of right elbow subsequent encounter |

| Code ICD-10-D-S53441S | Ulnar collateral ligament sprain of right elbow sequela |

| Code ICD-10-D-S53442A | Ulnar collateral ligament sprain of left elbow initial encounter |

| Code ICD-10-D-S53442D | Ulnar collateral ligament sprain of left elbow subsequent encounter |

| Code ICD-10-D-S53442S | Ulnar collateral ligament sprain of left elbow sequela |

| Code ICD-10-D-S53449A | Ulnar collateral ligament sprain of unspecified elbow initial encounter |

| Code ICD-10-D-S53449D | Ulnar collateral ligament sprain of unspecified elbow subsequent encounter |

| Code ICD-9-D-8411 | Ulnar collateral ligament sprain |

ICD, International Classification of Diseases.

References

- 1.Karbach L.E., Elfar J. Elbow instability: Anatomy, biomechanics, diagnostic maneuvers, and testing. J Hand Surg. 2017;42:118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2016.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erickson B.J., Harris J.D., Chalmers P.N., et al. Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction: Anatomy, indications, techniques, and outcomes. Sports Health. 2015;7:511–517. doi: 10.1177/1941738115607208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erickson B.J., Bach B.R., Jr., Cohen M.S., et al. Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction: The Rush experience. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4 doi: 10.1177/2325967115626876. 2325967115626876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jobe F.W., Stark H., Lombardo S.J. Reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68:1158–1163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conway J.E., Jobe F.W., Glousman R.E., Pink M. Medial instability of the elbow in throwing athletes. Treatment by repair or reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:67–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Azar F.M., Andrews J.R., Wilk K.E., Groh D. Operative treatment of ulnar collateral ligament injuries of the elbow in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:16–23. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280011401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cain E.L., Jr., Andrews J.R., Dugas J.R., et al. Outcome of ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction of the elbow in 1281 athletes: Results in 743 athletes with minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:2426–2434. doi: 10.1177/0363546510378100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dugas J.R., Walters B.L., Beason D.P., Fleisig G.S., Chronister J.E. Biomechanical comparison of ulnar collateral ligament repair with internal bracing versus modified jobe reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:735–741. doi: 10.1177/0363546515620390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones CM, Beason DP, Dugas JR. Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction versus repair with internal bracing: Comparison of cyclic fatigue mechanics [published online February 16, 2018]. Orthop J Sports Med. doi: 10.1177/2325967118755991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Dugas J.R., Looze C.A., Capogna B., et al. Ulnar collateral ligament repair with collagen-dipped fibertape augmentation in overhead-throwing athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47:1096–1102. doi: 10.1177/0363546519833684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erickson BJ, Bach BR, Jr., Verma NN, Bush-Joseph CA, Romeo AA. Treatment of ulnar collateral ligament tears of the elbow: Is repair a viable option [published online January 25, 2017]? Orthop J Sports Med. doi: 10.1177/2325967116682211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Richard M.J., Aldridge J.M., 3rd, Wiesler E.R., Ruch D.S. Traumatic valgus instability of the elbow: Pathoanatomy and results of direct repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:2416–2422. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Savoie F.H., 3rd, Trenhaile S.W., Roberts J., Field L.D., Ramsey J.R. Primary repair of ulnar collateral ligament injuries of the elbow in young athletes: A case series of injuries to the proximal and distal ends of the ligament. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:1066–1072. doi: 10.1177/0363546508315201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Urch E., DeGiacomo A., Photopoulos C.D., Limpisvasti O., ElAttrache N.S. Ulnar collateral ligament repair with suture bridge augmentation. Arthrosc Tech. 2018;7:e219–e223. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2017.08.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erickson B.J., Nwachukwu B.U., Rosas S., et al. Trends in medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in the United States: A retrospective review of a large private-payer database from 2007 to 2011. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:1770–1774. doi: 10.1177/0363546515580304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rothermich MA, Conte SA, Aune KT, Fleisig GS, Cain EL, Jr., Dugas JR. Incidence of elbow ulnar collateral ligament surgery in collegiate baseball players published online April 11, 2018]. Orthop J Sports Med. doi: 10.1177/2325967118764657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Argo D., Trenhaile S.W., Savoie F.H., 3rd, Field L.D. Operative treatment of ulnar collateral ligament insufficiency of the elbow in female athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:431–437. doi: 10.1177/0363546505281240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson A.T., Pidgeon T.S., Morrell N.T., DaSilva M.F. Trends in revision elbow ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in professional baseball pitchers. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40:2249–2254. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wymore L., Chin P., Geary C., et al. Performance and injury characteristics of pitchers entering the Major League Baseball draft after ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:3165–3170. doi: 10.1177/0363546516659305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bodendorfer B.M., Looney A.M., Lipkin S.L., et al. Biomechanical comparison of ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction with the docking technique versus repair with internal bracing. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46:3495–3501. doi: 10.1177/0363546518803771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Regan W.D., Korinek S.L., Morrey B.F., An K.N. Biomechanical study of ligaments around the elbow joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;(271):170–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrey B.F., Tanaka S., An K.N. Valgus stability of the elbow. A definition of primary and secondary constraints. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;(265):187–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loftice J., Fleisig G.S., Zheng N., Andrews J.R. Biomechanics of the elbow in sports. Clin Sports Med. 2004;23:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2004.06.003. vii-viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gainor B.J., Piotrowski G., Puhl J., Allen W.C., Hagen R. The throw: Biomechanics and acute injury. Am J Sports Med. 1980;8:114–118. doi: 10.1177/036354658000800210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fleisig G.S., Andrews J.R., Dillman C.J., Escamilla R.F. Kinetics of baseball pitching with implications about injury mechanisms. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:233–239. doi: 10.1177/036354659502300218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andrews J.R., Heggland E.J., Fleisig G.S., Zheng N. Relationship of ulnar collateral ligament strain to amount of medial olecranon osteotomy. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:716–721. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290060801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.An K.N., Morrey B.F., Chao E.Y. The effect of partial removal of proximal ulna on elbow constraint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;209:270–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erickson B.J., Harris J.D., Tetreault M., Bush-Joseph C., Cohen M., Romeo A.A. Is Tommy John surgery performed more frequently in major league baseball pitchers from warm weather areas? Orthop J Sports Med. 2014;2 doi: 10.1177/2325967114553916. 2325967114553916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clain J.B., Vitale M.A., Ahmad C.S., Ruchelsman D.E. Ulnar nerve complications after ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction of the elbow: A systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47:1263–1269. doi: 10.1177/0363546518765139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Somerson J.S., Petersen J.P., Neradilek M.B., Cizik A.M., Gee A.O. Complications and outcomes after medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction: A meta-regression and systematic review. JBJS Rev. 2018;6:e4. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.17.00138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erickson B.J., Chalmers P.N., D'Angelo J., Ma K., Romeo A.A. Performance and return to sport after ulnar nerve decompression/transposition among professional baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47:1124–1129. doi: 10.1177/0363546519829159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.