An article by Dr. Wakefield and colleagues in 1998 suggested negative gastrointestinal and behavioural effects of the mumps, measles, rubella (MMR) vaccine. This article rapidly gathered widespread media coverage and stirred one of the largest anti-vaccination movements in the history of humankind. It has affected the herd immunity of many vaccines including the coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination through anti-vaxx campaigns.1 However, it fell into disrepute after several researchers brought the flaws in the paper's methodology to the fore which led to its eventual retraction 2010.2 However, an unchecked, violent and wide dissemination of misinformation worldwide stood testimony of the perils of misinformation.

The paper was found to have wrongfully given credit to observations about the MMR vaccine without inclusion a control group of unvaccinated paediatric patients.3 Additionally, the authors claimed that autism is a consequence of intestinal inflammation but they investigated intestinal symptoms after, and not before, symptoms of autism in all eight cases. In addition to significant methodological flaws which seriously undermine the scientific validity of these observations, Dr. Wakefield's disregard to children in the study was another glaring concern.4 Blood samples for the study were collected from children at his son's birthday party, a serious unethical means of conduct. Allegedly Dr. Wakefield paid each child £5 and joked about it later, rendering this method of collection as unprofessional conduct in hopes of a financial gain.5 Moreover, the research was paid by lawyers representing parents that particularly sought to sue vaccine makers causing a significant bias. Consequent to wide circulation of the now maligned article on social media and among the academic community, many scientific papers attempted to draw up the association between autism and the MMR vaccine, although no viable links were made.6 Once publicized, the media seized the attention and created a large anti-vaccination community in fear of children developing autism.7 The published article in the Lancet had already gained significant attention before it could be discredited, and criticised for its authenticity and detrimental result.

Retracted articles are those that are pulled out from the sourced journal due to serious scientific misconduct, statistical errors, author and publisher oversights, and other reasons.8 The guidelines by the Committee on Publication Ethics state the following as ground for retraction: unreliability, redundancy, plagiarism, competing interests, and unethical conduct.9 The totalled aim after retraction is to acquaint the public regarding the falsification or unintentional error in the article and to increase awareness in lapses during review.10 The retracted article in discussion most definitely played a major role in the anti-vaccination campaign but the additional media advertisement by Dr. Wakefield himself transcended the public health concern even further. After retraction of the article in 2010, the MMR-autism falsehood made headlines in 2016 with the release of Vaxxed, a movie Dr. Wakefield directed that alleges a cover-up by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).11 The story features bioengineer Brian Hooker, who challenged a 2004 CDC study and decided to reanalyze the data. In 2014, Hooker claimed CDC had hidden evidence that the vaccine could increase autism risk in colored males. CDC particularly noted in their paper that rates of vaccination in the oldest age group were slightly higher in kids with autism. But CDC backed it up saying that this effect was “most likely a result of immunization requirements for preschool special education program attendance in children with autism.” The movie caused an out roar amongst parents and forced researchers to reinvestigate. Majority of reports found no correlation that MMR causes autism leaving Dr. Wakefield's research weak yet again. Healthcare communities and research professionals condemned the article false and a danger to society as a multitude of families refused to fulfil the vaccination agenda for MMR.12 Many other vaccines were also condemned for supposedly causing autism in children resulting in a disruption in the mandatory immunization program in the subsequent years.13,14 The problem was so severe that healthcare providers were advised to conduct a full education session with patients and online courses were also created to eliminate doubts and myths.

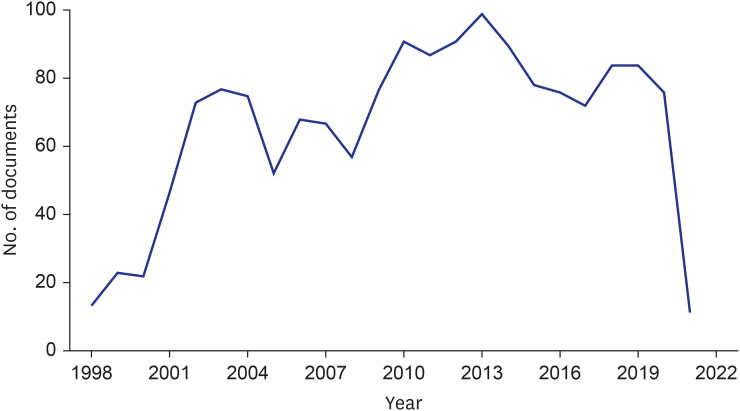

As of February 24, 2021, the retracted article had been cited a total of 1,588 times by Scopus-indexed documents (Fig. 1). Even after 11 years of retraction, the article still manages to be cited by more than 50 citations per year. Of 1,588 citing documents, 107 had been cited at least 107 times (h-index of the retracted article = 107). That would double the total exposure of the retracted article by the use of secondary citations. The initial citation activity gradually increased from 13 in 1998, to 99 in 2013, but slightly picked up again in 2018. The number of citations was high even after the article retraction in 2010. Overall, the top 5 sources of the citations to the retracted article are Vaccine (n = 55), Pediatrics (n = 23), Lancet (n = 17), Archives of Disease in Childhood (n = 15), and Expert Review of Vaccines (n = 14). One of the major sources was a 2014 meta-analysis in Vaccine that examined studies involving a total of a total of almost 1.3 million people. The study rebuked all the false claims made by Dr. Wakefield in his article and movie in order to silence the rumours for good. However, the social media presence of Scopus-indexed journals remains mainly through Twitter (14.2%) and Facebook (7.1%).15,16 Twitter carries an exposure of millions with the mass media (BBC, CNN, etc.) leading the viral spread of news.17 This supports the outburst of anti-vaxxers after the release of Dr. Wakefield's movie as it made headlines in multiple news industries. Studies show a flourishing impact of social media in the circulation of journal released articles within the last decade and a predicted increase in the future as well. The media play a large role in disseminating misinformation before and after retraction of the paper.18 Some studies indicate it as the main culprit of developing the anti-vaccination group across social media.19,20 More than half of secondary publications that cite retracted articles are either accidental or careless citations rendering them inadequate.21,22,23 Thus, the consistent number of citations of faulty research must be correlated to the social media publicity that sprung about debates, misinformed anti-vaccination campaigns, and wrongly cited secondary publications.

Fig. 1. Number of Scopus-indexed documents citing the retracted Lancet article in 1998–2021 (as of February 24, 2021).

As different media sources, news articles, and research articles claimed to support or defy the MMR vaccine- autism correlation, the citations of the retracted article fluctuated. Retracted Watch declared the second most cited article after retraction as of December 2020, was that written by Dr. Wakefield about the MMR vaccine-autism correlation.24 This is a major issue as the main purpose of retraction is to rebuke the article's research and findings. Cited articles also result in their own citations being used causing a chain of disputed information being spread. Since many citations were made after the retraction, this poses the question of whether these citations were used to rebuke the article or support its hypothesis. A detailed study on Dr. Wakefield's retracted work was done in November 2019, to assess the citation context.25 The top 5 citing authors were Fombonne E (n = 15), Wakefield AJ (n = 13), DeStefano F (n = 11), Fischhoff B (n = 10), and Leask J (n = 10). The US was the leading country in terms of citation activity with 683 related articles, followed by the UK (n = 393), Canada (n = 94), Italy (n = 67), and Australia (n = 65). The largest proportion of citing documents are articles (n = 736, 46.3%), followed by reviews (n = 376, 23.7%), and book chapters (n = 142, 8.9%). The main subject areas of the citing documents are medicine (n = 1,088, 43.8%), social sciences (n = 210, 8.4%), and immunology and microbiology (n = 186, 17.5%). The cross sectional analysis of the 1,153 citations found that although most citations negated the findings of the retracted article, they did not mention the retracted status. The study concludes with a strong recommendation for improvements required from publishers, bibliographic databases, and citation management software to ensure that retracted articles are accurately documented in all citations. Two other different researches, focusing on two different retracted papers, proved that their analysis of post-retraction citations were higher in number than pre-retraction citations.21,22 Moreover, they state that majority of post-retraction citations fail to mention the retracted status. This evidence supports the argument that most post-retraction citations diffuse misinformation rather than rebuking it.

In conclusion, retracted articles are still as capable of spreading their fraudulent information due to the weak scrutiny by publishers and their reference evaluation. With the greatest example of Dr. Wakefield's viral anti-vaccination stunt, the anti-vaxxers have distorted the significant progress that has led to herd immunity of many diseases and continue to set hurdles for the current severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 pandemic.26,27

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Conceptualization: Khan H, Gasparyan AY, Gupta L.

- Data curation: Khan H, Gasparyan AY, Gupta L.

- Formal analysis: Khan H, Gasparyan AY.

- Visualization: Khan H, Gasparyan AY, Gupta L.

- Writing - original draft: Khan H, Gupta L.

- Writing - review & editing: Gasparyan AY.

References

- 1.Giubilini A. Vaccination ethics. Br Med Bull. 2021;137(1):4–12. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldaa036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.College of Physicians of Philadelphia. History of vaccines history of anti-vaccination movements. [Updated 2018]. [Accessed March 9, 2021]. https://www.historyofvaccines.org/content/articles/history-anti-vaccination-movements.

- 3.Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. Vaccines and autism. [Updated 2018]. [Accessed March 21, 2021]. https://www.chop.edu/centers-programs/vaccine-education-center/vaccines-and-other-conditions/vaccines-autism.

- 4.Burns JF. British Medical Council bars doctor who linked vaccine with autism. [Updated 2010]. [Accessed March 19, 2021]. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/25/health/policy/25autism.html.

- 5.Deer B. How the case against the MMR vaccine was fixed. BMJ. 2011;342(7788):c5347. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Infectious Diseases and Immunization Committee. Autistic spectrum disorder: no causal relationship with vaccines. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2007;18(3):177–179. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hackett AJ. Risk, its perception and the media: the MMR controversy. Community Pract. 2008;81(7):22–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gasparyan AY, Ayvazyan L, Akazhanov NA, Kitas GD. Self-correction in biomedical publications and the scientific impact. Croat Med J. 2014;55(1):61–72. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2014.55.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) Retraction guidelines. [Updated 2009]. [Accessed March 19, 2021]. http://publicationethics.org/files/retraction guidelines.pdf.

- 10.Moylan EC, Kowalczuk MK. Why articles are retracted: a retrospective cross-sectional study of retraction notices at BioMed Central. BMJ Open. 2016;6(11):e012047. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wessel L. Four vaccine myths and where they came from. Science. 2017 doi: 10.1126/science.aal1110. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karafillakis E, Dinca I, Apfel F, Cecconi S, Wűrz A, Takacs J, et al. Vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers in Europe: a qualitative study. Vaccine. 2016;34(41):5013–5020. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davidson M. Vaccination as a cause of autism-myths and controversies. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2017;19(4):403–407. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2017.19.4/mdavidson. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.OpenLearn. The MMR vaccine: public health, private fears. [Updated 2016]. [Accessed March 9, 2021]. https://www.open.edu/openlearn/ocw/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2552&printable=1.

- 15.Zheng H, Aung HH, Erdt M, Peng TQ, Sesagiri Raamkumar A, Theng YL. Social media presence of scholarly journals. J Assoc Inf Sci Technol. 2019;70(3):256–270. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hassan SU, Imran M, Gillani U, Aljohani NR, Bowman TD, Didegah F. Measuring social media activity of scientific literature: an exhaustive comparison of Scopus and novel altmetrics big data. Scientometrics. 2017;113:1037–1057. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cha M, Benevenuto F, Haddadi H, Gummadi K. The world of connections and information flow in Twitter. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern A Syst Hum. 2012;42(4):991–998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta L, Gasparyan AY, Misra DP, Agarwal V, Zimba O, Yessirkepov M. Information and misinformation on COVID-19: a cross-sectional survey study. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(27):e256. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burki T. Vaccine misinformation and social media. Lancet Digit Heal. 2019;1(6):e258–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson SL, Wiysonge C. Social media and vaccine hesitancy. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(10):e004206. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneider J, Ye D, Hill AM, Whitehorn AS. Continued post-retraction citation of a fraudulent clinical trial report, 11 years after it was retracted for falsifying data. Scientometrics. 2020;125(3):2877–2913. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bornemann-Cimenti H, Szilagyi IS, Sandner-Kiesling A. Perpetuation of retracted publications using the example of the Scott S. Reuben case: incidences, reasons and possible improvements. Sci Eng Ethics. 2016;22(4):1063–1072. doi: 10.1007/s11948-015-9680-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bolboacă SD, Buhai DV, Aluaș M, Bulboacă AE. Post retraction citations among manuscripts reporting a radiology-imaging diagnostic method. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0217918. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Center for Scientific Integrity, Inc. Top 10 most highly cited retracted papers. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed March 9, 2021]. https://retractionwatch.com/the-retraction-watch-leaderboard/top-10-most-highly-cited-retracted-papers/

- 25.Suelzer EM, Deal J, Hanus KL, Ruggeri B, Sieracki R, Witkowski E. Assessment of citations of the retracted article by Wakefield et al with fraudulent claims of an association between vaccination and autism. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1915552. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.15552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guttinger S. The anti-vaccination debate and the microbiome: How paradigm shifts in the life sciences create new challenges for the vaccination debate. EMBO Rep. 2019;20(3):e47709. doi: 10.15252/embr.201947709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hussain A, Ali S, Ahmed M, Hussain S. The anti-vaccination movement: a regression in modern medicine. Cureus. 2018;10(7):e2919. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]