Abstract

Comorbid insomnia and sleep apnea (COMISA) are the most common co-occurring sleep disorders and present many challenges to clinicians. This review provides an overview of the clinical challenges in the management of patients with COMISA, with a focus on recent evidence regarding the evaluation and treatment of COMISA. Innovations in the assessment of COMISA have used profile analyses or dimensional approaches to examine symptom clusters or symptom severity that could be particularly useful in the assessment of COMISA. Recent randomized controlled trials have provided important evidence about the safety and effectiveness of a concomitant treatment approach to COMISA using cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) with positive airway pressure (PAP). Furthermore, patient-centered considerations that integrate patient characteristics, treatment preferences, and accessibility to treatment in the context of COMISA are discussed as opportunities to improve patient care. Based on these recent advances and clinical perspectives, a model for using multidisciplinary, patient-centered care is recommended to optimize the clinical management of patients with COMISA.

Key Words: cognitive-behavior therapy for insomnia, insomnia, patient-centered care, positive airway pressure, sleep apnea

Abbreviations: AHI, apnea-hypopnea index; BSM, behavioral sleep medicine; CBT-I, cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia; COMISA, comorbid insomnia and sleep apnea; HSAT, home sleep apnea test; PAP, positive airway pressure; PSG, polysomnography; RCT, randomized controlled trials; SES, socioeconomic status

OSA is a sleep-related breathing disorder that affects approximately 10% to 20% of middle- to older-aged adults1 and is associated with excessive daytime sleepiness, cardiovascular sequelae, neurocognitive deficits, and depression.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Respiratory events result in sleep fragmentation and poor sleep quality. It is also common for people with OSA to have difficulty falling or staying asleep. Given that chronic insomnia is considered a distinct disorder,7,8 comorbid insomnia and sleep apnea (COMISA) are the most common co-occurring sleep disorders, with a global prevalence between 18% and 42%,9 and a prevalence between 29% and 67% among patients presenting for treatment. COMISA is associated with increased medical (eg, cardiometabolic conditions) and psychiatric morbidity (eg, mood disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder), and worse daytime functioning relative to each condition alone.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 As a result, clinical management of COMISA is often very challenging.

Currently, no definitive guidelines exist for evaluating and treating patients with COMISA. Traditional approaches based on clinical lore and older diagnostic nomenclature are being challenged by recent innovations and emerging data that support multidisciplinary approaches with considerations based on patient-centered care. This shift includes utilization of symptom profiles or phenotypes that transcend diagnostic categories, treatment combinations using various specialties and sequences, and consideration of patient characteristics and preferences throughout the process of clinical care. The purpose of this review is to provide an overview of the clinical challenges associated with the management of patients with COMISA. Emphasis is given to recent evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCT) and perspectives in patient-centered care that can optimize clinical management of COMISA.

Clinical Challenges

Traditional Approaches to the Assessment of COMISA

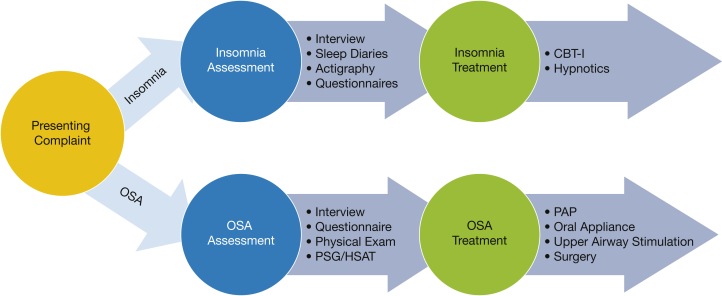

The traditional approach to assessing sleep disorders is to conduct a clinical interview/examination and, if indicated, to conduct a laboratory-based polysomnography (PSG) test. The clinical pathway is driven by provisional diagnosis and tends to be parallel (Fig 1). If the referral is for OSA, or if the chief complaint is suggestive of OSA (eg, snoring, witnessed apneas), the clinical evaluation typically involves (1) a clinical interview to ascertain nocturnal signs and symptoms and daytime indications of sleepiness/fatigue, (2) a physical examination of the oropharynx and assessment of other conditions that could be causing the sleep disturbance, and (3) a laboratory PSG or home sleep apnea test (HSAT). If the referral is for insomnia or if the chief complaint is suggestive of insomnia (eg, difficulty falling or staying asleep), the clinical evaluation typically involves (1) a clinical interview with emphasis on the sleep/wake patterns (eg, bedtimes, waketimes), sleep hygiene considerations, and psychological features (eg, racing thoughts in bed); (2) prospective sleep/wake diaries or actigraphy monitoring for 1 to 2 weeks; and (3) self-report questionnaires, which can include global symptoms of insomnia (eg, Insomnia Severity Index, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index) or questionnaires to assess common comorbid conditions such as mood or anxiety scales.

Figure 1.

This figure illustrates the traditional model for clinical management of comorbid insomnia and sleep apnea (COMISA). The presenting complaint or reason for referral serves as the basis for provisional diagnosis (insomnia or OSA) which then leads to parallel clinical pathways. If insomnia is suspected, the assessment typically involves a clinical interview with sleep diaries, actigraphy, and questionnaires used as appropriate. The standard treatment is CBT-I with short-term use of hypnotic medications appropriate in certain situations. If OSA is suspected, the assessment typically involves a clinical interview and examination followed by a PSG or HSAT, with questionnaires used as needed. The standard treatment is PAP, with other treatments such as oral appliance, upper airway stimulation, or surgery considered when appropriate. CBT-I = cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia; HSAT = home sleep apnea test; PAP = positive airway pressure; PSG = polysomnography.

For patients with COMISA, the evaluation process is less clear and may include several potential clinical dilemmas. First, the presenting complaint or reason for referral (insomnia or OSA symptoms) could lead the clinician to make different decisions regarding the evaluation pathway. PSG is not recommended in the standard assessment of insomnia, and therefore, patients whose primary complaint is difficulty falling or staying asleep might not receive a PSG or HSAT before initiating treatment for insomnia. This can result in occult OSA remaining undiagnosed and undertreated. Similarly, patients who present with OSA symptoms are less likely to complete prospective sleep diaries or actigraphy monitoring, which could result in undiagnosed or undertreated comorbid insomnia. Furthermore, the clinician’s specialty and clinical environment could influence decisions in the evaluation pathway. For example, pulmonary specialists might be more inclined to focus on OSA assessment (eg, PSG, HSAT) for patients with COMISA, and behavioral specialists (eg, psychiatrist, psychologist) might be more inclined to focus on assessing insomnia. Finally, questionnaires commonly used to assess insomnia alone are not validated in patients with COMISA, potentially resulting in misdiagnosis of comorbid insomnia when the underlying disorder is OSA alone.19 As a result, patients with COMISA may find that these traditional pathways for OSA and insomnia do not fit their condition, and they are at risk for receiving suboptimal treatment.

Innovations in the Assessment of COMISA

In contrast to the traditional approach, recent innovations using symptom profiles are looking beyond the presenting complaint or diagnostic categories, which could be particularly useful in the assessment of COMISA. The subtype of insomnia (eg, difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, or early morning awakenings) can impact the rate of co-occurrence with OSA.12,20 Chung20 found that sleep maintenance and early morning awakenings were the most common subtype of insomnia associated with OSA. In a large population-based study of people with OSA, 16% had sleep-onset insomnia, 59% had sleep maintenance insomnia, and 28% had early morning awakenings.21 Empirically driven clinical and population-based studies using OSA symptoms have identified COMISA as a common OSA phenotype. In a study using the Icelandic Sleep Apnea Cohort with moderate to severe OSA, three symptom clusters were described: (1) minimally symptomatic, (2) disturbed sleep, and (3) excessively sleepy.13 Approximately one third (32.7%) of the cohort belonged to the “disturbed sleep” group, characterized by insomnia symptoms and restless sleep. A similar study conducted on an international clinical sample (Sleep Apnea Global Interdisciplinary Consortium) described two additional clusters (upper airway symptoms with sleepiness and upper airway symptoms dominant) with a lower prevalence (19.0%) of the “disturbed sleep” group.22 Compared with the other clusters, the “disturbed sleep” group contained the highest proportion of females, black individuals, and greatest levels of obesity. Using similar OSA symptoms in the Sleep Heart Health Study among individuals with moderate to severe OSA, Mazzotti et al23 found four OSA clusters, with a 12.2% prevalence of the “disturbed sleep” type. One important limitation in this literature is that relatively few studies have included validated insomnia assessments in the analyses, which might account for the variability of the prevalence of COMISA across studies.24 Crawford et al25 conducted latent profile analyses on a sample, using diagnostic criteria for insomnia, and found that the “mild insomnia” subtype had significantly a greater percentage of OSA (70%) compared with the other subtypes (∼50%). These studies serve as examples of how data-driven approaches could move the field beyond reliance on the presenting complaint and potentially avoid clinician bias.

Traditional Approaches to the Treatment of COMISA

Although well-established treatments exist for OSA and insomnia separately, no definitive guidelines are available for how to combine or integrate these treatments in the case of COMISA. The traditional approach to COMISA has been to treat OSA and insomnia separately (Fig 1). Typically, OSA treatment is considered primary, and thus the first-line treatment for COMISA has followed the guidelines for OSA treatment.26 The gold standard treatment for OSA is positive airway pressure (PAP), with oral appliances, upper airway stimulation, or surgery considered when appropriate.26 Insomnia treatment is considered secondary, typically when the insomnia persists after OSA is well controlled or when OSA treatments fail (eg, low PAP adherence). The gold standard treatment for insomnia is cognitive-behavior therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), which has substantial evidence supporting its effectiveness and safety27,28 (Table 1 gives a summary of CBT-I components). However, CBT-I is typically delivered by a sleep psychologist or similarly trained mental health provider, and the number of qualified CBT-I providers is limited. As a result, hypnotics are frequently used by patients with COMISA.29 This traditional approach is centered on the working hypothesis that the insomnia symptoms are secondary to OSA, and thus it should resolve with optimal OSA treatment.

Table 1.

Summary of Treatment Components of Cognitive-Behavior Therapy for Insomnia

| CBT-I Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Sleep restriction | Restrict time in bed to increase homeostatic pressure for sleep and consolidate sleep |

| Stimulus control | Reestablish bed/bedroom as stimulus for sleep by not entering until sleepy |

| Sleep hygiene | Eliminate habits and lifestyle factors that may increase the risk of sleep disturbances |

| Relaxation strategies | Reduce anxiety and physical tension (hyperarousal) |

| Cognitive therapy | Challenging and restructuring maladaptive thoughts and beliefs that interfere with sleep and daytime functioning |

CBTI = cognitive-behavior therapy for insomnia.

Evidence is accumulating that this sequential approach is suboptimal and does not address several clinical issues. First, when insomnia is present with OSA, evidence suggests that the insomnia symptoms are associated with low adherence to PAP.21,30,31 Regular use of PAP can be very challenging given that only approximately 30% to 50% of OSA patients are regular long-term users of PAP.32, 33, 34 Furthermore, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services reimbursement policy require patients to demonstrate adequate adherence to PAP within the first 3 months, defined as usage of the PAP device for at least 4 hours per night on 70% of nights during a consecutive 30-day period. As a result, patients with COMISA are at particularly high risk for not meeting these expectations and losing reimbursement for PAP therapy. Second, pharmacological treatment of insomnia in patients with COMISA could potentially exacerbate daytime sleepiness or have other adverse effects (eg, increased risk of motor vehicle accidents). Third, patients who do not perceive any benefits from PAP therapy or who do not receive appropriate treatment for insomnia might be dissatisfied with their sleep treatments.35

Given these clinical dilemmas and lack of clear guidelines, prospective clinical studies have sought to gather evidence about concomitant treatments for COMISA. In one of the first studies to use CBT-I in COMISA, Krakow et al36 reported on a case replication series of patients who received CBT-I first, followed by receiving an OSA treatment (PAP, oral appliance, or surgery). They found that 47% reported clinically significant improvements after CBT-I, compared with 88% who reported clinically significant improvements after receiving both treatments. Furthermore, many patients were not initially interested in or ready for OSA treatment as the initial treatment. Using a mixed-methods approach, Ong et al35 found that patients generally preferred to receive a combination of treatments using CBT-I and PAP, but there was uncertainty about the optimal timing of initiating insomnia treatment. These studies exemplify the importance of concomitant treatments targeting both insomnia and OSA in patients with COMISA.

Evidence From Recent RCTs on COMISA

Three RCTs have been published examining CBT-I and PAP for COMISA. Sweetman et al37 compared CBT-I vs a treatment-as-usual control before receiving PAP treatment in 145 patients with COMISA. Compared with the control condition, those in the CBT-I group demonstrated greater average nightly adherence to PAP by 61 minutes (P = .023, d = 0.38) and higher initial PAP treatment acceptance (99% vs 89%; P = .034). Furthermore, those who received CBT-I showed greater improvement on global insomnia severity as measured by the insomnia severity index. A second report from this RCT examined weekly changes in sleep patterns and daytime sleepiness. Sweetman and colleagues38 found a 15% increase in sleepiness the week after administering sleep restriction therapy as part of CBT-I. However, the levels of sleepiness subsided to pretreatment levels in the subsequent weeks, whereas sleep patterns generally improved. A third report from this RCT39 examined the impact of CBT-I on OSA severity and found a 7.5-point greater decrease in AHI from pre to post treatment in the CBT-I group compared with a no-treatment control group.

Ong et al40 conducted a three-arm RCT on 121 adult patients with COMISA, using a partial factorial design to compare the timing of treatment initiation with CBT-I and PAP. Compared with PAP alone, the concomitant treatment arms reported a significantly greater reduction from baseline on the insomnia severity index (P = .0009) and had a greater percentage of participants who were categorized as good sleepers (P = .044) and remitters from insomnia (P = .008). No significant differences were found between the sequential (CBT-I followed by PAP) vs concurrent treatment models on any outcome measure. In contrast to the findings from Sweetman et al,37 no significant differences were found between the concomitant treatment arms and PAP only on PAP adherence.

A third RCT by Bjorvatn et al41 examined 164 adults with COMISA who received CBT-I delivered using bibliotherapy (ie, self-help book) compared with a sleep hygiene control concurrent with initiation CPAP treatment. The authors found that both groups reported reductions in insomnia severity with no significant between-group differences, which the authors attributed to improvements from receiving CPAP.

Collectively, these RCTs support the effectiveness and safety of using therapist-delivered CBT-I in patients with COMISA. Specifically, a four-session CBT-I before or concurrent with PAP is superior to PAP alone on insomnia outcomes, whereas bibliotherapy-delivered CBT-I is insufficient. Additionally, no serious adverse events related to CBT-I were reported, and the increase in sleepiness resulting from sleep restriction therapy was temporary.38 This suggests that CBT-I is safe, although sleepiness should be monitored throughout treatment. The evidence regarding whether CBT-I can also improve adherence to PAP is not entirely clear. Possibly the conflicting findings might be due to the inclusion of mild OSA in the Ong et al40 study, whereas the Sweetman et al37 study included only moderate to severe OSA (apnea-hypopnea index [AHI] ≥ 15). Alternatively, the conflicting findings might be the result of differences in sampling. The Sweetman et al37 study recruited primarily from sleep clinics and the Ong et al40 study recruited from the community, many of whom were not seeking treatment and did not know they had sleep apnea before participating in the study. Finally, the Sweetman et al37 study revealed an intriguing finding that CBT-I can potentially decrease OSA severity.

Clinical Considerations for Patient-Centered Care

In addition to the emerging evidence for assessment and treatment, patient-centered care should also consider patient characteristics, treatment preferences, and accessibility of treatment. This section reviews clinical considerations that have not received sufficient attention in COMISA but could improve assessment and personalization of treatment in patients with COMISA.

Demographics and Socioeconomic Status

Patient demographics are an important consideration in the assessment and treatment of COMISA. Some studies have found sex differences in the clinical presentation of COMISA, with women more likely to present with insomnia symptoms and men more likely to report witnessed apneas.42,43 Furthermore, the OSA phenotype with “disturbed sleep” is more common among women than men with OSA.22,44 Age is a known risk factor for OSA and insomnia independently, and older age appears to be a risk factor for COMISA.45 One study that examined both sex and age found a significant interaction between these two risk factors.46 The highest prevalence of COMISA in men occurred between the ages of 45 and 55 years, but the highest prevalence of COMISA in women occurred past age 55. Regarding OSA therapy, both age and sex influence adherence to PAP therapy, with younger women using PAP less regularly than older men.47,48

Race and ethnicity are also important demographic factors to consider in the presentation and treatment of COMISA. In one study, the OSA phenotype with “disturbed sleep” had the highest proportion of blacks relative to the other four OSA subgroups.22 Blacks are known to have increased prevalence of OSA and more severe disease burden relative to whites but poorer adherence to PAP therapy.49 Furthermore, in clinical samples, blacks have been reported to have poorer adherence to CBT-I therapy than white individuals.50 Blacks, who on average sleep 1 hour less than white individuals, may find the sleep restriction component of CBT-I particularly challenging.51 One study examining sex and ethnicity found that among those with OSA, white women were most likely to report sleep maintenance insomnia, whereas Hispanic women were most likely to report sleep-onset insomnia.43

Socioeconomic status (SES), such as level of education and marital/civil status, should also be considered as part of patient-centered care. Low SES individuals are known to have greater risk of OSA and more disruptive, less efficient sleep.51 Furthermore, lower SES individuals continue to have reduced adherence to PAP therapy compared with higher SES individuals.52 In RCTs of insomnia, lower SES individuals have been found to have significantly higher rates of dropout.53 The presence of a regular bed partner can impact the patient’s presenting complaint and reason for treatment, because individuals who are married or have a regular bed partner might be more motivated to seek treatment and also to adhere to treatment. Ong et al40 found that a high level of education and being married were both associated with better PAP use among COMISA patients, indicating that SES stability might improve treatment outcomes. This also suggests that those with low SES might benefit from additional patient education, and individuals who do not have a regular bed partner might benefit from additional peer support.

Treatment Preferences

Although very little is known about the treatment preferences of COMISA patients, a mixed-methods study35 provided important insights on the patient perspective of COMISA. First, COMISA patients were more inclined to define their sleep problem by their symptom profile (problems falling asleep or problems staying asleep) rather than by the diagnostic category (insomnia or OSA). Thus, clinicians should be cognizant of the patients’ primary complaint, because presenting them with a treatment plan (eg, starting with CPAP) that is inconsistent with their main complaint (eg, problems falling asleep) might be counterproductive. A second finding showed that COMISA patients were confused by having multiple sleep practitioners, rather than one “sleep doctor.” For these patients, having two different treatments presented might be confusing and even conflicting. Because multidisciplinary teams are particularly well suited to manage COMISA,54 patient education might be an important consideration to explain the process and benefits of this approach.

Treatment Accessibility

The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic has raised the importance of flexibility in access to clinical services, which is another important aspect of patient-centered care. Fortunately, management of COMISA is adaptable to this environment, given the rise of HSAT, telemedicine, and digital health. Clinical assessment of COMISA can be conducted using a combination of telehealth visits and online questionnaires to gather clinical information and HSAT to evaluate the presence of OSA. Many PAP machines can be adjusted automatically (ie, auto-PAP) without face-to-face contact, and most PAP machines use can be monitored remotely through the Internet. Similarly, CBT-I can be conducted remotely, using telehealth models, which can increase access to a behavioral sleep medicine (BSM) provider, particularly in rural areas or when a BSM provider is not located nearby. Alternatively, automated digital CBT-I programs are available, and preliminary results from an RCT suggest that it can improve insomnia symptoms but does not significantly improve PAP adherence or daytime sleepiness.55 See Table 2 for further information on CBT-I delivery options.

Table 2.

Summary of CBT-I Delivery Methods and Accessibility

| Delivery Methods | Description | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|

| In-person | Delivered using individual or group format with a behaviorial sleep medicine provider (see behaviorsleep.org for a list of providers). | Limited access because of the limited number of BSM providers. |

| Telehealth | Individual sessions delivered through phone or video with a qualified BSM provider. | Improved access due to reduced need to travel but still requires a BSM provider to deliver treatment. |

| Digital | Automated, digital programs that can be accessed using the internet. Examples include the Path to Better Sleep (www.veterantraining.va.gov/insomnia) or Somryst (https://somryst.com/) | Most accessible because no BSM provider is needed. However, might require resources and technological skills to access. |

BSM = behavioral sleep medicine.

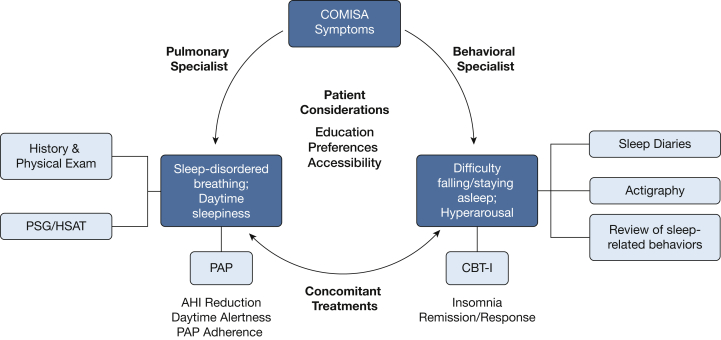

A Model for Effective Clinical Management of COMISA

Progress to date has provided evidence to shift the clinical management of COMISA toward a multidisciplinary, patient-centered approach (Fig 2). Rather than working exclusively from a provisional diagnosis or within specialties, a comprehensive multidisciplinary assessment should be conducted with input from behavioral, pulmonary, and other relevant specialties. This allows clinicians with various backgrounds to use their expertise with the respective diagnostic tools to develop a more comprehensive symptom profile. For example, pulmonary specialists can focus on symptoms related to sleep-disordered breathing and daytime sleepiness through a history and physical examination and PSG/HSAT data. Behavioral specialists can focus on symptoms related to insomnia and hyperarousal by using sleep diaries and actigraphy and assessing sleep-related behaviors. Patient considerations (eg, preferences, demographics) and accessibility options (eg, telehealth) and assessment of other sleep disorders (eg, restless leg syndrome) and comorbidities (eg, mood disorders) that could impact treatment decisions should also be conducted as part of this process by both specialists. The data gathered can then be synthesized to develop a symptom profile to guide discussion among the multidisciplinary team regarding the most appropriate treatment approach. For many patients, an ideal combination would be a four-session CBT-I delivered by a BSM provider early in the course of treatment along with PAP therapy initiated concurrently or shortly after CBT-I that is managed by a pulmonary or sleep specialist. Considerations should be given to patient preferences and accessibility of treatment with alternatives for digital CBT-I or telehealth monitoring. As part of this process, patient education about these treatments along with a discussion of the goals, expectations, and potential barriers can be useful to develop a treatment plan that prioritizes outcomes that are clinically important and personally relevant to the patient. After treatments are delivered, follow-up assessment on key outcomes of each treatment should be conducted to monitor treatment adherence and progress as part of quality care.56,57 This includes AHI reduction, daytime alertness, and PAP adherence for PAP and insomnia remission/response for CBT-I. If needed, alternative treatment modalities can be considered. Because current evidence is still inconclusive to provide specific guidelines on whether all patients with insomnia should receive a PSG/HSAT or the optimal sequence of treatments, this model for COMISA management encourages a dimensional assessment approach, patient engagement, and multidisciplinary expertise to help guide decision-making.

Figure 2.

Working model for a patient-centered, multidisciplinary approach to the management of COMISA. Rather than working from a provisional diagnosis, pulmonary and behavioral specialists can use their relevant expertise in diagnostic tools to generate a symptom profile. Based on the findings from this comprehensive assessment, concomitant treatments using PAP and CBT-I should be considered. Follow-up assessment on key outcomes should be conducted after receiving each treatment (eg, AHI reduction for PAP, insomnia remission for CBT-I) to determine whether further treatment or alternative approaches are needed. Considerations of patient characteristics, treatment preferences and accessibility, treatment adherence, and satisfaction are central throughout this process. AHI = apnea-hypopnea index; CBT-I = cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia; COMISA = comorbid insomnia and sleep apnea; HSAT = home sleep apnea test; PAP = positive airway pressure; PSG = polysomnography.

Future Directions

Future research should continue to build on these findings and investigate other areas that can improve precision and personalization of care. First, research is needed to validate data-driven assessment approaches for COMISA and to inform the implementation of these methods in clinical settings. The rise of wearable technologies and machine learning can provide an avenue to collect “real-world” data from patients and synthesize these into symptom profiles. Second, research is still needed to provide guidance on the optimal treatment combination or sequence. For example, are there patients with COMISA who should receive PAP first? Should patients be assessed at certain intervals during the treatment pathway to determine whether they should continue with their current treatment or add another treatment? RCT designs such as the sequential multiple assignment randomized trial can provide insights to these questions. Third, specific research is needed on patient-centered factors, such as demographic variables, patient preferences, and various delivery methods that can enhance patient engagement and impact treatment response (eg, culturally tailored CBT-I, linguistically tailored education on OSA and PAP). Finally, future studies should consider other treatment combinations beyond CBT-I and PAP. For example, what is the effectiveness of behavioral approaches combined with an oral appliance or upper airway stimulation? Integrating CBT-I with other cognitive-behavioral strategies for PAP adherence (eg, motivational interviewing) also could be useful, and preliminary findings from a recently completed RCT58 have reported benefits for a broad CBT intervention. Future investigations such as these can provide more specific data to inform best practices for managing patients with COMISA.

Acknowledgments

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: None declared.

Role of sponsors: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Other contributions: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: Preparation for this paper was based upon support by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under grant award number R01HL114529.

References

- 1.Balk E.M., Moorthy D., Obadan N.O. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: Jul 2011. Diagnosis and Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adults. Report number: 11-EHC052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peppard P.E., Young T., Palta M., Skatrud J. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(19):1378–1384. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005113421901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young T., Palta M., Dempsey J., Skatrud J., Weber S., Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(17):1230–1235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weaver T.E., George C.F.P. Cognition and performance in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. In: Kryger M.H.I., Roth T.I., Dement W.C., editors. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 5th ed. Elsevier Saunders; St. Louis, MO: 2011. pp. 1194–1206. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nieto F.J., Young T.B., Lind B.K. Association of sleep-disordered breathing, sleep apnea, and hypertension in a large community-based study: Sleep Heart Health Study. JAMA. 2000;283(14):1829–1836. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.14.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marin J.M., Agusti A., Villar I. Association between treated and untreated obstructive sleep apnea and risk of hypertension. JAMA. 2012;307(20):2169–2176. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Academy of Sleep Medicine . 3rd ed. American Academy of Sleep Medicine; Darien, IL: 2014. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Psychiatric Association . 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Vol 5. Arlington, VA. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y., Ren R., Lei F. Worldwide and regional prevalence rates of co-occurrence of insomnia and insomnia symptoms with obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2019;45:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2019.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ong J.C., Gress J.L., San Pedro-Salcedo M.G., Manber R. Frequency and predictors of obstructive sleep apnea among individuals with major depressive disorder and insomnia. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67(2):135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi S.J., Joo E.Y., Lee Y.J., Hong S.B. Suicidal ideation and insomnia symptoms in subjects with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep Med. 2015;16(9):1146–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krell S.B., Kapur V.K. Insomnia complaints in patients evaluated for obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep & Breathing. 2005;9 doi: 10.1007/s11325-005-0026-x. 104-110-104-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ye L., Pien G.W., Ratcliffe S.J. The different clinical faces of obstructive sleep apnoea: a cluster analysis. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(6):1600–1607. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00032314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang C.J., Appleton S.L., Vakulin A. Co-morbid OSA and insomnia increases depression prevalence and severity in men. Respirology. 2017;22(7):1407–1415. doi: 10.1111/resp.13064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tasbakan M.S., Gunduz C., Pirildar S., Basoglu O.K. Quality of life in obstructive sleep apnea is related to female gender and comorbid insomnia. Sleep Breath. 2018;22(4):1013–1020. doi: 10.1007/s11325-018-1621-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallace D.M., Sawyer A.M., Shafazand S. Comorbid insomnia symptoms predict lower 6-month adherence to CPAP in US veterans with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2018;22(1):5–15. doi: 10.1007/s11325-017-1605-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta M.A., Knapp K. Cardiovascular and psychiatric morbidity in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) with insomnia (sleep apnea plus) versus obstructive sleep apnea without insomnia: a case-control study from a Nationally Representative US sample. PLoS One. 2014;9(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sivertsen B., Bjornsdottir E., Overland S., Bjorvatn B., Salo P. The joint contribution of insomnia and obstructive sleep apnoea on sickness absence. J Sleep Res. 2013;22(2):223–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2012.01055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wallace D.M., Wohlgemuth W.K. Predictors of insomnia severity index profiles in United States veterans with obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(12):1827–1837. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung K.F. Insomnia subtypes and their relationships to daytime sleepiness in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Respiration. 2005;72(5):460–465. doi: 10.1159/000087668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bjornsdottir E., Janson C., Sigurdsson J.F. Symptoms of insomnia among patients with obstructive sleep apnea before and after two years of positive airway pressure treatment. Sleep. 2013;36(12):1901–1909. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keenan B.T., Kim J., Singh B. Recognizable clinical subtypes of obstructive sleep apnea across international sleep centers: a cluster analysis. Sleep. 2018;41(3) doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsx214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mazzotti D.R., Keenan B.T., Lim D.C., Gottlieb D.J., Kim J., Pack A.I. Symptom subtypes of obstructive sleep apnea predict incidence of cardiovascular outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(4):493–506. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201808-1509OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ong J.C., Crawford M.R. Insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med Clin. 2013;8(3):389–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crawford M.R., Chirinos D.A., Iurcotta T. Characterization of patients who present with insomnia: is there room for a symptom cluster-based approach? J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(7):911–921. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Epstein L.J., Kristo D., Strollo P.J., Jr. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(3):263–276. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qaseem A., Kansagara D., Forciea M.A., Cooke M., Denberg T.D. Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of P. Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(2):125–133. doi: 10.7326/M15-2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu J.Q., Appleman E.R., Salazar R.D., Ong J.C. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia comorbid with psychiatric and medical conditions: a meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1461–1472. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krakow B., Ulibarri V.A., Romero E. Persistent insomnia in chronic hypnotic users presenting to a sleep medical center: a retrospective chart review of 137 consecutive patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198(10):734–741. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181f4aca1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wickwire E.M., Smith M.T., Birnbaum S., Collop N.A. Sleep maintenance insomnia complaints predict poor CPAP adherence: a clinical case series. Sleep Med. 2010;11(8):772–776. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pieh C., Bach M., Popp R. Insomnia symptoms influence CPAP compliance. Sleep Breath. 2013;17(1):99–104. doi: 10.1007/s11325-012-0655-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rotenberg B.W., Murariu D., Pang K.P. Trends in CPAP adherence over twenty years of data collection: a flattened curve. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;45(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s40463-016-0156-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baratta F., Pastori D., Bucci T. Long-term prediction of adherence to continuous positive air pressure therapy for the treatment of moderate/severe obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep Med. 2018;43:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2017.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tan B., Tan A., Chan Y.H., Mok Y., Wong H.S., Hsu P.P. Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure therapy in singaporean patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Otolaryngol. 2018;39(5):501–506. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ong J.C., Crawford M.R., Kong A. Management of obstructive sleep apnea and comorbid insomnia: a mixed-methods evaluation. Behav Sleep Med. 2017;15(3):180–197. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2015.1087000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krakow B., Melendrez D., Lee S.A., Warner T.D., Clark J.O., Sklar D. Refractory insomnia and sleep-disordered breathing: a pilot study. Sleep Breath. 2004;8(1):15–29. doi: 10.1007/s11325-004-0015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sweetman A., Lack L., Catcheside P.G. Cognitive and behavioral therapy for insomnia increases the use of continuous positive airway pressure therapy in obstructive sleep apnea participants with co-morbid insomnia: a randomized clinical trial. Sleep. 2019;42(12):zsz178. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsz178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sweetman A., McEvoy R.D., Smith S. The effect of cognitive and behavioral therapy for insomnia on week-to-week changes in sleepiness and sleep parameters in patients with comorbid insomnia and sleep apnea: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep. 2020;43(7) doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsaa002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sweetman A., Lack L., McEvoy R.D. Cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia reduces sleep apnoea severity: a randomised controlled trial. ERJ Open Res. 2020;6(2) doi: 10.1183/23120541.00161-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ong J.C., Crawford M.R., Dawson S.C. A randomized controlled trial of CBT-I and PAP for obstructive sleep apnea and comorbid insomnia: main outcomes from the MATRICS study. Sleep. 2020;43(9):zsaa041. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsaa041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bjorvatn B., Berge T., Lehmann S., Pallesen S., Saxvig I.W. No effect of a self-help book for insomnia in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and comorbid chronic insomnia - a randomized controlled trial. Front Psychol. 2018;9:2413. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shepertycky M.R., Banno K., Kryger M.H. Differences between men and women in the clinical presentation of patients diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep. 2005;28(3):309–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Subramanian S., Guntupalli B., Murugan T. Gender and ethnic differences in prevalence of self-reported insomnia among patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2011;15(4):711–715. doi: 10.1007/s11325-010-0426-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saaresranta T., Hedner J., Bonsignore M.R. Clinical phenotypes and comorbidity in European sleep apnoea patients. PLoS One. 2016;11(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lichstein K.L., Riedel B.W., Lester K.W., Aguillard R.N. Occult sleep apnea in a recruited sample of older adults with insomnia. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:405–410. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.3.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Z., Li Y., Yang L. Characterization of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with insomnia across gender and age. Sleep Breath. 2015;19(2):723–727. doi: 10.1007/s11325-015-1121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Woehrle H., Graml A., Weinreich G. Age- and gender-dependent adherence with continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Sleep Med. 2011;12(10):1034–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patel S.R., Bakker J.P., Stitt C.J., Aloia M.S., Nouraie S.M. Age and gender disparities in adherence to continuous positive airway pressure [Published online ahead of print July 17, 2020] Chest. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.07.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wallace D.M., Williams N.J., Sawyer A.M. Adherence to positive airway pressure treatment among minority populations in the US: a scoping review. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;38:56–69. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2017.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.El-Solh A.A., O’Brien N., Akinnusi M., Patel S., Vanguru L., Wijewardena C. Predictors of cognitive behavioral therapy outcomes for insomnia in veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Sleep Breath. 2019;23(2):635–643. doi: 10.1007/s11325-019-01840-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Williams N., Jean Louis G., Blanc J., Wallace D.M. Race, socieconomic position and sleep. In: Grandner M., editor. Sleep and Health. 1st ed. Academic Press; San Diego: 2019. pp. 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pandey A., Mereddy S., Combs D. Socioeconomic inequities in adherence to positive airway pressure therapy in population-level analysis. J Clin Med. 2020;9(2):442. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheng P., Kalmbach D.A., Tallent G., Joseph C.L., Espie C.A., Drake C.L. Depression prevention via digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep. 2019;42(10):zsz150. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsz150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ong J.C., Crisostomo M.I. The more the merrier? Working towards multidisciplinary management of obstructive sleep apnea and comorbid insomnia. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69(10):1066–1077. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Edinger J, Manber R. The Apnea And Insomnia Research (Air) Trial: a preliminary report. Paper presented at: SLEEP2020; August 27-30, 2020.

- 56.Edinger J.D., Buysse D.J., Deriy L. Quality measures for the care of patients with insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11(3):311–334. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aurora R.N., Collop N.A., Jacobowitz O., Thomas S.M., Quan S.F., Aronsky A.J. Quality measures for the care of adult patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11(3):357–383. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alessi C., Martin J., Fung C. Randomized controlled trial of an integrated behavioral treatment in veterans with obstructive sleep apnea and coexisting insomnia. Sleep. 2018;41(suppl_1) A155-A155. [Google Scholar]