Abstract

Background: Stunting is the impaired growth and development of children due to poor nutrition, repeated infection, and inadequate psychological stimulation. This research aims to examine the impact of maternal nutritional literacy (MNL) in increasing the height or score of a stunted child.

Design and Methods: This study is a randomized control trial, which uses a sample size of 85 participants, 43 interventions and 42 controls, an 80% stress test and a 95% confidence level. The intervention group of the MNL consists of families with children under the age of five, focused on the mother’s ability to perform breastfeeding, hygiene activities, care, and intervention for 3 months.

Result: The status of stunting was determined by the different distribution of stunting before and after the intervention in both the intervention and control groups. There was a decrease of about 9.3% of MNL in the intervention group, while in the control group it decreased by just 2.4% (p<0.05).

Conclusions: It can be concluded that MNL has an effect in preventing stunting, and it is recommended that preventive measures should focus more on normal children, while stunted children should be provided with breastfeeding as the core of MNL.

Significance for public health.

Preventing stunting requires an effort based on the family potential, and the nutritional literacy of the maternal is the most appropriate measure in achieving the preventive goals. This article shows that the maternal nutrition literacy interventions are very good in such a way that they become a reference for improving the nutrition and public health.

Key words: Maternal nutrition literacy, stunting prevention, status of stunting

Introduction

Maternal Nutritional Literacy (MNL) is the lastest topic discovered in the nutritional education for mothers and children, and its emphasis is placed on the general ability of mothers to understand the concept and implementation of nutrition in all aspect of life, especially in the balance diet for all age groups, especially those that are prone to nutritional problems.1 The nutritional literacy of the mothers focuses on breast milk and complementary food literacy.2-5 The pandemic created an exacerbated issues for the breastfeeding mother’s, and the women involved in the breastfeeding had to stop and blamed it on failure in milk supply. Earlier, mothers and babies were systematically isolated from the pandemic in China, Malaysia, Philippines, Indonesia, and other countries and the breast milk supplies was recommended.6 About 3 weeks after birth, 44 percent of the mothers seeking for consultation at the breastfeeding centers in Western Australia for breastfeeding problems experienced an inadequate milk supply. In addition to this, about 74 % were worried that their infants are not really happy after breastfeeding.7 The current gap in the scientific evidence shows the effect of maternal nutritional literacy on the coping mechanism of child nutrition, especially in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic. An experimental MNL intervention study is needed to answer the hypothesis, which can be used to prevent the direct effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on stunted children within the first 1000 days after birth.8 Based on national research on stunting, the trend has increased in the last five years from 25.7% to 30.8% between 2013 and 2018. There has been an increase in South Sulawesi and Makassar City, Indonesia, slowly decreasing from 40.9 to 35.7%. This percentage is high and several systematic and sustained prevention efforts need to be undertaken.9 The negative impact caused by stunting is low academic potential, high risk of non-communicable diseases,10 high cost of health services, and low productivity.11 The problem of stunting should be avoided because its incidence from birth is difficult to treat, and its prevention begins from the preliminary examination period until the child is two years old.12-14 In contrast, based on the results of the systematic review, the determinants of stunting factors in children under the age of five are very complicated and complex, but there are variables that can be used in for the intervention in order to prevent stunting sustainably. Conceptually, it is known that mothers, play the most important role in the care (feeding, care, hygiene, and treatment-seeking) of children during the critical growth period. Child, mother, and social environmental factors are like two sides of a coin. If the response is positive, it was useful to support children’s growth and vice versa, and the maximum caring capacity is seen as an opportunity to improve sustainable nutrition.15-17

The stunting potential can be maximized when the various appropriate intervention efforts can be carried out. The nutrientdense feeding interventions through various means of micronutrient supplements or other feeding programs was recommended, especially in Indonesia, complementary feeding was carried out for all children. Every stunted child at birth must be given the best food according to the recommendations of the Infant and Young Child Feeding by UNICEF /WHO. The important variables in this phase are Early Initiation of Breastfeeding (EIB), colostrum, exclusive breastfeeding, complementary feeding, and continued breastfeeding for up to 2 years. Various research that have been carried out relating to stunting prevention in South Sulawesi, Indonesia includes findings that breastfeeding has the potential to prevent stunting, especially for poor families,5 assistance in overcoming breastfeeding difficulties,3 and to properly prepare for the transition of children from exclusive breastfeeding to complementary foods.4,18 The cases of stunting from birth to 6 months can be identified, but no intervention can be carried out until the child is 6 months old.19 The only effort is exclusive breastfeeding, which also poses problems with inappropriate breastfeeding practices, which comes from the capacity of the mother to breastfeed and family factors delivered by MNL. The objectives of this study is to analyze the effect of MNL intervention on stunting in infants, aged 0-6 months.

Design and Methods

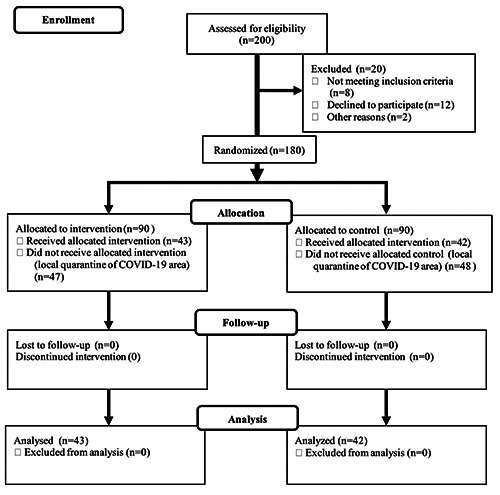

This research is a Randomized Control Trial conducted in Makassar City, Indonesia, from July to October 2020. The proportion of children under five in the case group was 10% and the proportion in the control group was 30%. The total sample consisted of 85 mothers with children aged 0 to 6 months (Figure 1). As the research implementation was limited by local quarantine policy during the COVID-19 pandemic in the city of Makassar, the sample size does not up to half of the required number. Data was collected through home visits by implementing health protocols, such as using of masks, social distancing, and washing of hands. The researcher provided masks and hand sanitizers for each participant that was interviewed during the implementation and also when the family building activities were carried out, especially in the intervention group.

The final number of samples was 43 intervention groups and 42 controls. The first step was the sampling of mother of children aged 0-6 months, and the nutrition officer at the public health center provided a sample of 88 subjects. Furthermore, home visits were made for the initial study and reported that as many as 88 people and at the final data collection, only 85 people were reported, leaving 3 people because they were not willing and hesitant to be met and moved to their hometown (outside Makassar city). This study has been approved by the Makassar City Health Office (440/201/PSDK/III/2000), the Provincial Government of South Sulawesi (070/690-II/BKBP/III/2020), and the Makassar City Government (1954/S-01/PTSP/2020).

Figure 1.

Randomized control trial of maternal nutrition literacy intervention.

The intervention group activities consist of 5 items, class education (the learning outcome are a better understanding of basic principle breastfeeding, complementary feeding), class simulation (The learning outcome are to solve breastfeeding practices and complementary feeding), home visits 2 times a month and total visits of 15 times for (learning outcome are supporting new habit in breastfeeding practices and complementary feeding practices), growth child monitoring, and hand sanitation. Meanwhile, the control group activities consists of 5 items, basic immunization, growth monitoring, and vitamin A supplementation, for every month during the intervention period (natural intervention).

The HAZ-Score-Z data were not normally distributed, and the stunting status data were used for analysis. The state of stunting before the intervention between the intervention and control groups was tested by Kruskal-Wallis test. The same was carried out for the intervention, and the hypothesis testing on the effect of the intervention on stunting prevention was tested with the Wilcoxon test by examining the distribution of stunting before and after the intervention. All of these tests are at a 95% confidence level.

Results and Discussions

Based on this study, it is known that the majority of mothers have responsibility as housewives, 88.4% in the intervention group and 88.1% in the control group respectively. It is also known that the majority of fathers’ occupations are private employees and 60.4% are laborers in the two groups, and most mothers graduated from college 49% (Table 1). The results of statistical analysis showed that at the beginning of the intervention, the distribution of nutritional status (height/age) was the same between the intervention group and the control group (p=0.475). The same happened when the intervention was carried out for 3 months, there was no difference in the distribution of nutritional status (HAZ) (p=0.965). The efficacy of the family guidance interventions for children under five can be seen after comparing the distribution of nutritional status (HAZ) in the group. In the intervention group, it was reported that there was a difference in the distribution of stunting from 23.3% down to 14% (p=0.046) or a decrease of 9.3%. In the control group, there was a decrease in the percentage of stunting from 16.7% to 14.3 (2.4%) but there was no significant decrease (p=0.317) (Table 2).

In this study, status of stunting was determined based on the Height for Age (HAZ). The results on the status showed that MNL significantly influenced the status of stunting in the intervention group by 9.3%, while it decreased in the control group by by 2.4%. The results of the MNL intervention on the nutritional status of HAZ showed that there were changes in the nutritional status in all groups, both control, and intervention (p <0.05). It was reported that in the age phase from 0 to 3 months to 4 to 6 months there was a tendency to gain weight, which increased the nutritional status of a good diet with the risk of overeating. In the intervention group, the significance was 0.005 while in the control group the significance was 0.025. Generally, the percentage of nutritional status with a greater risk of 7.1% changed to 17.5% or increased by 10.4%. This increase was as a result of a decrease in the percentage of good nutrition from 66% to 61% or a decrease of 5% and the rest from a change in malnutrition status to good nutrition from 14.1% to 9.4% or a decrease of 4.7%. As stated by Hossain M, the reduction in the percentage of stunting globally is 3% per year, while in Indonesia it is only 1.6%.20 Previous studies explained that complementary feefings could improve child nutrition as well as their growth. Above all, the series of studies show that extensive interventions with strict control of sensitive and specific intervention components can significantly reduce stunting. Some of the previous research notes were that not every intervention gave equal effective results in the target community.21-24 There were many factors that influenced it, including social and cultural backgrounds.25 The generalization of the results is that both the sensitive and specific stunting interventions can consistently reduce its incidence in such a way that there will be changes in the status, which decreases significantly with the intervention. The incidence of stunting continued to occur in the group that was not intervened, and this occurred because the incidence of failure to thrive increased with age. The limitation of this study is that the number of samples is not optimal due to limited access to interaction when large-scale social restrictions was implemented in Makassar City.

Table 1.

Characteristics of subjects.

| Mother's occupation | Intervention | Control | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Mother's occupation | ||||||

| Housewife | 38 | 88.4 | 37 | 88.1 | 75 | 88.2 |

| Traders | 1 | 2.3 | 1 | 2.4 | 2 | 2.4 |

| General employees | 4 | 9.3 | 4 | 9.5 | 8 | 9.4 |

| Father's occupation | ||||||

| Workers / workers / motorcycle taxis | 13 | 30.2 | 13 | 30.2 | 26 | 30.6 |

| General employees | 13 | 30.2 | 13 | 30.2 | 26 | 30.6 |

| Traders | 3 | 7.0 | 3 | 7.1 | 6 | 7.1 |

| Officials government | 14 | 32.6 | 13 | 31.0 | 27 | 31.8 |

| Father's education | ||||||

| Elementary school | 2 | 4,7 | 2 | 4.8 | 4 | 4.7 |

| Junior school | 7 | 16.3 | 7 | 16.7 | 14 | 16.5 |

| High school | 13 | 30.2 | 12 | 28.6 | 25 | 29.4 |

| College | 21 | 48.8 | 21 | 50.0 | 42 | 49.4 |

| Mother's education | ||||||

| Elementary school | 2 | 4,7 | 2 | 4.8 | 4 | 4.7 |

| Junior school | 7 | 16.3 | 7 | 16.7 | 14 | 16.5 |

| High school | 13 | 30.2 | 12 | 28.6 | 25 | 29.4 |

| College | 21 | 48.8 | 21 | 50.0 | 42 | 49.4 |

Table 2.

The efficacy of maternal nutrition literacy intervention for stunting prevention.

| Stunting | Intervention | Control | Total | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | (Kruskal-Wallis) | ||

| After | Severely stunted | 2 | 4.7 | 2 | 4.8 | 4 | 4.7 | 0.965 |

| Stunted | 4 | 9.3 | 4 | 9.5 | 8 | 9.4 | ||

| Normal | 37 | 86.0 | 36 | 85.7 | 73 | 85.9 | ||

| Total | 43 | 100.0 | 42 | 100.0 | 85 | 100.0 | ||

| Before | Severely stunted | 2 | 4.7 | 2 | 4.8 | 4 | 4.7 | 0.475 |

| Stunted | 8 | 18.6 | 5 | 11.9 | 13 | 15.3 | ||

| Normal | 33 | 76.7 | 35 | 83.3 | 68 | 80.0 | ||

| Total | 43 | 100.0 | 42 | 100.0 | 85 | 100.0 | ||

| p-value (Wilcoxon) | 0.046* | 0.317 | 0.000** | |||||

Conclusions

The maternal nutrition literacy intervention can be used as a way of reducing stunting in the group of children aged 0-6 months. Stunting prevention interventions need to ideally focus on children that are not stunted because it is easier to prevent stunting than to focus on children that are already stunted even at the age of 0-6 months.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank to Health Polytechnic of Makassar, Indonesia.

Funding Statement

Funding: This study was funded by the Makassar Health Polytechnic

References

- 1.Mbogori T, Murimi M, Ruhul A. Nutrition education intervention: Using train the trainer approach to reach populations with low literacy in Turkana, Kenya. J Nutr Educ Behav 2015;47:S81–2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babakazo P, Donnen P, Akilimali P, et al. Predictors of discontinuing exclusive breastfeeding before six months among mothers in Kinshasa: a prospective study. Int Breastfeed J 2015;10:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ipa A Hartono R, Sirajuddinet al. Breast feeding practice prevention for nutritional stunting of children in Buginese ethnicity. Indian J Forensic Med Toxicol 2020;14:1108–12. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sirajuddin Sirajuddin S, Hadju V, et al. Complemetary feeding practices influences of stunting children in Buginese ethnicity. Indian J Forensic Med Toxicol 2020;14:1227–33. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sirajuddin Nursalim AT. Breastfeeding practices can potential to prevent stunting for poor family. Enferma Clin 2020;30:13–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown A, Shenker N. Experiences of breastfeeding during COVID-19: Lessons for future practical and emotional support. Matern Child Nutr 2020;17:e13088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kent JC, Ashton E, Hardwick CM, et al. Causes of perception of insufficient milk supply in Western Australian mothers. Matern Child Nutr 2020;17:e13080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minhas AS, Scheel P, Garibaldi B, et al. Takotsubo syndrome in the setting of COVID-19. JACC Case Rep 2020;2:1321-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGovern ME, Krishna A, Aguayo VM, et al. A review of the evidence linking child stunting to economic outcomes. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:1171–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Said-Mohamed R, Pettifor JM, Norris SA. Life History theory hypotheses on child growth: Potential implications for short and long-term child growth, development and health. Am J Phys Anthropol 2018;165:4–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danaei G, Andrews KG, Sudfeld CR, et al. Risk factors for childhood stunting in 137 developing countries: A comparative risk assessment analysis at global, regional, and country levels. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dewey KG, Begum K. Long-term consequences of stunting in early life. Matern Child Nutr. 2011;7:S5–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mridha MK, Matias SL, Chaparro CM, et al. Lipid-based nutrient supplements for pregnant women reduce newborn stunting in a cluster-randomized controlled effectiveness trial in Bangladesh. Am J Clin Nutr 2016;103:236–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giao H, Le An P, Truong Vien N, et al. Stunting and overweight among 12-24-month-old children receiving vaccination in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Biomed Res Int 2019;2019:1547626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Onis M, Branca F. Childhood stunting: A global perspective. Matern Child Nutr 2016;12:12–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beal T, Tumilowicz A, Sutrisna A, et al. A review of child stunting determinants in Indonesia. Matern Child Nutr 2018;14:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sukmawati H, Sirajuddin. Assistance in child feeding influences the nutritional intake of stunting children: Randomized control trial. Indian J Forensic Med Toxicol 2020;14:1948–52. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartono R, Ipa A, Sirajuddin, et al. Feeding style for children aged 0-59 months of buginese ethnicity. Indian J Forensic Med Toxicol 2020;14:1216–20. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tama TD, Astutik E, Katmawanti S, et al. Birth patterns and delayed breastfeeding initiation in Indonesia. J Prev Med Public Heal 2020;53:465–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hossain M, Choudhury N, Abdullah KAB, et al. Evidencebased approaches to childhood stunting in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. Arch Dis Child 2017;102:903–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang Y, Kim S, Sinamo S, et al. Effectiveness of a community- based nutrition programme to improve child growth in rural Ethiopia: a cluster randomized trial. Matern Child Nutr 2017;13:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olney DK, Pedehombga A, Ruel MT, et al. A 2-year integrated agriculture and nutrition and health behavior change communication program targeted to women in Burkina Faso reduces anemia, wasting, and diarrhea in children 3-12.9 months of age at baseline: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Nutr 2015;145:1317–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kandpal E, Alderman H, Friedman J, et al. A conditional cash transfer program in the philippines reduces severe stunting. J Nutr 2016;146:1793–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Effendy DS, Prangthip P, Soonthornworasiri N, et al. Nutrition education in Southeast Sulawesi Province, Indonesia: A cluster randomized controlled study. Matern Child Nutr 2020;4: e13030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matias SL, Mridha MK, Tofail F, et al. Home fortification during the first 1000 d improves child development in Bangladesh: a cluster-randomized effectiveness trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;105:958-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]