Atlastin mediates fusion of ER membranes. Liu et al. show that Atlastin 2/3 also contribute to the recruitment and stabilization of ULK1 and ATG101 at the autophagosome formation sites on the ER.

Abstract

Dynamic targeting of the ULK1 complex to the ER is crucial for initiating autophagosome formation and for subsequent formation of ER–isolation membrane (IM; autophagosomal precursor) contact during IM expansion. Little is known about how the ULK1 complex, which comprises FIP200, ULK1, ATG13, and ATG101 and does not exist as a constitutively coassembled complex, is recruited and stabilized on the ER. Here, we demonstrate that the ER-localized transmembrane proteins Atlastin 2 and 3 (ATL2/3) contribute to recruitment and stabilization of ULK1 and ATG101 at the FIP200-ATG13–specified autophagosome formation sites on the ER. In ATL2/3 KO cells, formation of FIP200 and ATG13 puncta is unaffected, while targeting of ULK1 and ATG101 is severely impaired. Consequently, IM initiation is compromised and slowed. ATL2/3 directly interact with ULK1 and ATG13 and facilitate the ATG13-mediated recruitment/stabilization of ULK1 and ATG101. ATL2/3 also participate in forming ER–IM tethering complexes. Our study provides insights into the dynamic assembly of the ULK1 complex on the ER for autophagosome formation.

Introduction

The ER, consisting of tubules and sheets, forms extensive membrane contact sites (MCSs) with other membrane-bound structures, including endosomes, mitochondria, the Golgi apparatus, lipid droplets, and the plasma membrane (Phillips and Voeltz, 2016; Prinz, 2014; Shibata et al., 2006; Zhang and Hu, 2016). The MCSs participate in lipid transfer and Ca2+ exchange between the two apposed organelles as well as regulate dynamic organelle processes, such as fission, fusion, and positioning (Phillips and Voeltz, 2016; Prinz, 2014; Raiborg et al., 2015). Formation of MCSs is mediated by protein–protein and/or protein–phospholipid interactions (Phillips and Voeltz, 2016; Prinz, 2014). The integral ER membrane proteins VAPA and VAPB (collectively called VAPs) participate in ER contact formation by directly interacting with factors on apposed membranes, including the VAPs–SNX2 interaction in the ER–endosome contact, the VAPs–OSBP interaction in the ER–Golgi contact, and the VAPs–PTPIP51 interaction in the ER–mitochondrion contact (De Vos et al., 2012; Dong et al., 2016; Peretti et al., 2008). VAPs can also interact with proteins on the ER or with phospholipid-binding proteins, which in turn bind to proteins or phospholipids on the apposed membranes, to mediate ER contact formation (Prinz, 2014).

Autophagy refers to a process involving the sequestration of a portion of the cytosolic constituents in a double-membrane autophagosome and its delivery to lysosomes for degradation (Feng et al., 2014; Lamb et al., 2013; Mizushima et al., 2011; Nakatogawa et al., 2009). The core steps of autophagy contain the initiation and nucleation of a cup-shaped isolation membrane (IM) and its subsequent expansion and closure into the autophagosome. Upon closure, the autophagosome fuses with vesicles originating from the endolysosomal compartment to become acidified and eventually form a degradative autolysosome (Mizushima, 2018; Zhao and Zhang, 2019). In mammalian cells, the autophagy induction signal triggers the ER targeting of the ULK1 complex (composed of the scaffold protein FIP200, the kinase ULK1, and the cofactors ATG13 and ATG101), followed by the VPS34 PI(3)P kinase complex to generate PI(3)P-enriched subdomains of the ER known as omegasomes (Axe et al., 2008; Ktistakis and Tooze, 2016). The omegasome acts as a platform for the nucleation and expansion of IMs. It has been suggested that vesicles containing the multispanning membrane protein ATG9 act as one of the membrane sources for IM nucleation and expansion (Karanasios et al., 2016). The WD40 repeat–containing PI(3)P-binding protein WIPI2 (one of four mammalian ATG18 homologues) and the ATG16L–ATG5–ATG12 complex are targeted to IMs for lipidation of the ubiquitin-like protein LC3 (mammalian ATG8 homologue; Polson et al., 2010; Zhao and Zhang, 2018). During its expansion, the IM forms highly dynamic contacts with the ER (Hayashi-Nishino et al., 2009; Ylä-Anttila et al., 2009). The FIP200/ULK1–WIPI2 complex and the ATG2–WIPI4 complex have been suggested to be involved in tethering the ER–IM contact (Zhao et al., 2017, 2018; Zhang, 2020). ATG2 possesses lipid transfer activity and may transport lipids from the ER to the IM at the contact sites (Maeda et al., 2019; Osawa et al., 2019; Valverde et al., 2019). The ER-localized autophagy protein EPG-3/VMP1 modulates the disassembly of the IM–ER contact by regulating the activity of SERCA (Zhao et al., 2017). Loss of VMP1 activity results in enhanced ER–IM contact (Zhao et al., 2017).

The ULK1 complex is not an ordered and constitutively coassembled complex (Shi et al., 2020). Components of the ULK1 complex contain both modular domains as well as intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) and form dissociable interactions (Lin and Hurley, 2016; Mizushima, 2010; Shi et al., 2020). FIP200, consisting of an N-terminal domain (NTD), an IDR linker, a coiled-coil domain, and a C-terminal CLAW domain, acts as the scaffold in assembly of the ULK1 complex. ULK1 contains an N-terminal kinase domain, a long IDR, and a C-terminal early autophagy targeting/tethering (EAT) domain. ATG13 consists of an N-terminal HORMA (Hop1, Rev7, and MAD2) domain, which dimerizes with the HORMA domain of ATG101, and a long C-terminal IDR. The IDR of ATG13 interacts with the NTD of FIP200 as well as with the EAT domain of ULK1 (Shi et al., 2020). Binding to ATG13 triggers conformational changes in the FIP200 NTD that further elicit a direct interaction between FIP200 NTD and ULK1 EAT (Shi et al., 2020). The ULK1 complex is targeted to the ER upon autophagy induction and disassociates from the omegasome before closure of IMs into autophagosomes (Karanasios et al., 2013). The puncta formed by the ULK1 complex on the ER are stabilized by sustained PI(3)P synthesis (Karanasios et al., 2013). VAPs also directly interact with FIP200 and ULK1 through their conserved FFAT motifs and stabilize the ULK1–FIP200 interaction (Zhao et al., 2018). VAPs also contribute to ER–IM contact formation by enhancing formation of the FIP200/ULK1–WIPI2 tethering complex (Zhao et al., 2018). It remains largely unknown how components of the ULK1 complex are dynamically targeted to the ER and form a stable complex there for autophagosome initiation.

The ER-localized transmembrane proteins ATL1, 2, and 3, a class of dynamin-like GTPases, mediate ER membrane fusion. Depletion of ATLs results in the formation of long, unbranched, and less mobile ER tubules (Hu et al., 2009). ATLs regulate multiple ER-related processes, such as calcium homeostasis, lipid metabolism, microtubule dynamics, and membrane trafficking (Lü et al., 2020; Niu et al., 2019; Park et al., 2010). ATLs have been suggested to function in ERphagy, a process referring to selective engulfment of ER fragments into the autophagosome for degradation (Chino and Mizushima, 2020). ATL2 remodels the ER membrane to separate ER fragments for autophagic degradation (Liang et al., 2018), while ATL3 functions as a putative receptor to promote degradation of the tubular ER by interacting with ATG8 family autophagy proteins (Chen et al., 2019). Here, we demonstrate that ATL 2 and 3 (ATL2/3) also function in the basal autophagy pathway. ATL2/3 regulate autophagosome initiation by modulating the ATG13-mediated targeting and stabilization of ULK1 and ATG101 at the autophagosome formation sites on the ER. ATL2/3 also function in the formation of the ER–IM contact. Our study provides insights into the dynamic assembly of the ULK1 complex in early steps of autophagosome formation.

Results

Depletion of ATL2/3 impairs autophagy activity

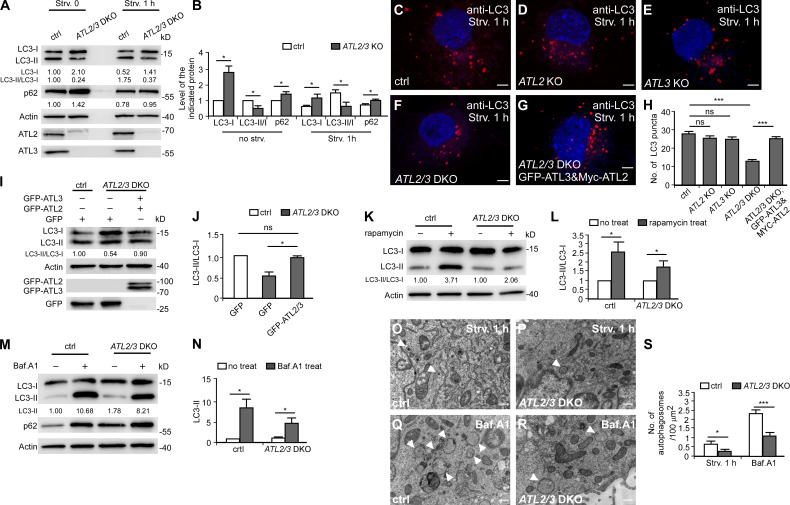

Of all the members of the ATL family, ATL2/3 are expressed in most cell types (Lü et al., 2020). To investigate whether ATLs regulate autophagy, we used ATL2 and ATL3 single knockout (KO) cells and double KO (DKO) COS-7 cells. In these cells, we examined lipidation of LC3 and degradation of the autophagy substrate p62, which are two widely used assays for monitoring autophagy activity (Klionsky et al., 2016). Upon autophagy induction, the diffuse LC3 (LC3-I) is conjugated to PE (LC3-II, the lipidated form) that associates with autophagic structures. Blocking autophagy at different steps leads to characteristic changes in the LC3-I level as well as in the LC3-II/LC3-I ratio. A decrease in the LC3-II/LC3-I ratio suggests an impairment of IM formation, while an increase in the LC3-II/LC3-I ratio suggests that autophagy activity is elevated or blocked at a step downstream of IM initiation (e.g., progression of IMs into autophagosomes or formation and/or function of autolysosomes). We found that in ATL2/3 DKO cells under normal or 1-h starvation conditions, levels of LC3-I were dramatically increased, while levels of LC3-II were increased much less, resulting in a marked reduction in the ratio of LC3-II/LC3-I (Fig. 1, A and B). Compared with control cells under starvation conditions, the number of LC3 puncta was not significantly changed in ATL2 or ATL3 single KO cells but was dramatically reduced in DKO cells (Fig. 1, C–F and H). Levels of p62 were also increased in ATL2/3 DKO cells (Fig. 1, A and B). The autophagy defect in ATL2/3 DKO cells was rescued by expression of ATL2 and ATL3 (Fig. 1, G–J).

Figure 1.

Depletion of ATL2/3 impairs autophagy activity. (A and B) Immunoblotting assays showing levels of p62 and LC3 in control and ATL2/3 DKO COS-7 cells under control conditions and after 1 h of starvation. Quantifications of p62 levels, LC3-I levels, and LC3-II/LC3-I ratios are also shown (normalized by actin levels). The level of LC3-I and ratio of LC3-II/LC3-I in control cells are set to 1.00. (B) The quantitative data of A shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05. (C–G) Compared with control cells (C), the number of LC3 puncta in ATL2 KO (D) and ATL3 KO (E) cells is not evidently decreased, while the number of LC3 puncta in ATL2/3 DKO (F) cells is dramatically decreased after 1 h of starvation. The decreased number of LC3 puncta in ATL2/3 DKO cells is rescued by expression of GFP-ATL3 and Myc-ATL2 (G). Scale bars, 5 µm. (H) Quantitative data for the number of LC3 puncta in control (C), ATL2 KO (D), ATL3 KO (E), ATL2/3 DKO (F) cells and ATL2/3 DKO cells expressing Myc-ATL2 and GFP-ATL3 (G) are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 30 cells in each group). ***, P < 0.001. (I and J) The decreased ratio of LC3-II/LC3-I in ATL2/3 DKO cells is rescued by expression of GFP-ATL2 and GFP-ATL3. Quantification of the LC3-II/LC3-I ratios (normalized by actin levels) is also shown. The LC3-II/LC3-I ratio in control cells is set to 1.00 (I). The quantitative data are shown in J as mean ± SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05. (K and L) Immunoblotting assays showing that the ratios of LC3-II/LC3-I are increased after treatment with rapamycin in control and ATL2/3 DKO cells. Compared with control cells, the degree of change is less dramatic in ATL2/3 DKO cells. Quantification of LC3-II/LC3-I ratios (normalized by actin levels) is also shown. The LC3-II/LC3-I ratios in control and ATL2/3 DKO cells without rapamycin treatment are set to 1.00 (K). The quantitative data are shown in L as mean ± SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05. (M and N) Levels of LC3-II are increased after treatment with Baf.A1 in control and ATL2/3 DKO cells in immunoblotting assays. Compared with control cells, the degree of increase of LC3-II is less dramatic in ATL2/3 DKO cells. Quantification of LC3-II ratios (normalized by actin levels) is also shown. The LC3-II/LC3-I ratio in control cells without rapamycin treatment is set to 1.00 (M). The quantitative data are shown in N as mean ± SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05. (O–S) EM micrographs of control (O and Q) and ATL2/3 DKO (P and R) COS-7 cells after 1 h of starvation (O and P) or after Baf.A1 treatment (Q and R). Arrowheads indicate autophagosomes. The numbers of autophagosomes are quantified in S as mean ± SEM (n = 50 sections in each group, one section for each cell). *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001. Scale bars, 0.5 µm. ctrl, control; Strv, starved.

Upon rapamycin treatment, the ratio of LC3-II/LC3-I in ATL2/3 DKO cells was increased compared with untreated DKO cells, but the degree of increase was less dramatic than in control cells with rapamycin treatment (Fig. 1, K and L). This suggests that autophagy still proceeds but at a reduced rate in ATL2/3 DKO cells. After treatment with the autophagosome–lysosome fusion inhibitor bafilomycin A1 (Baf.A1), levels of LC3-II were lower in ATL2/3 cells than in control cells (Fig. 1, M and N), which is consistent with the notion that autophagy induction is impaired. Ultrastructural EM analysis showed that after 1 h of starvation, there were fewer autophagosomes in ATL2/3 DKO cells than in control cells with or without simultaneous Baf.A1 treatment (Fig. 1, O–S). Taken together, these results indicate that the formation of autophagosomes was impaired by depletion of ATL2/3.

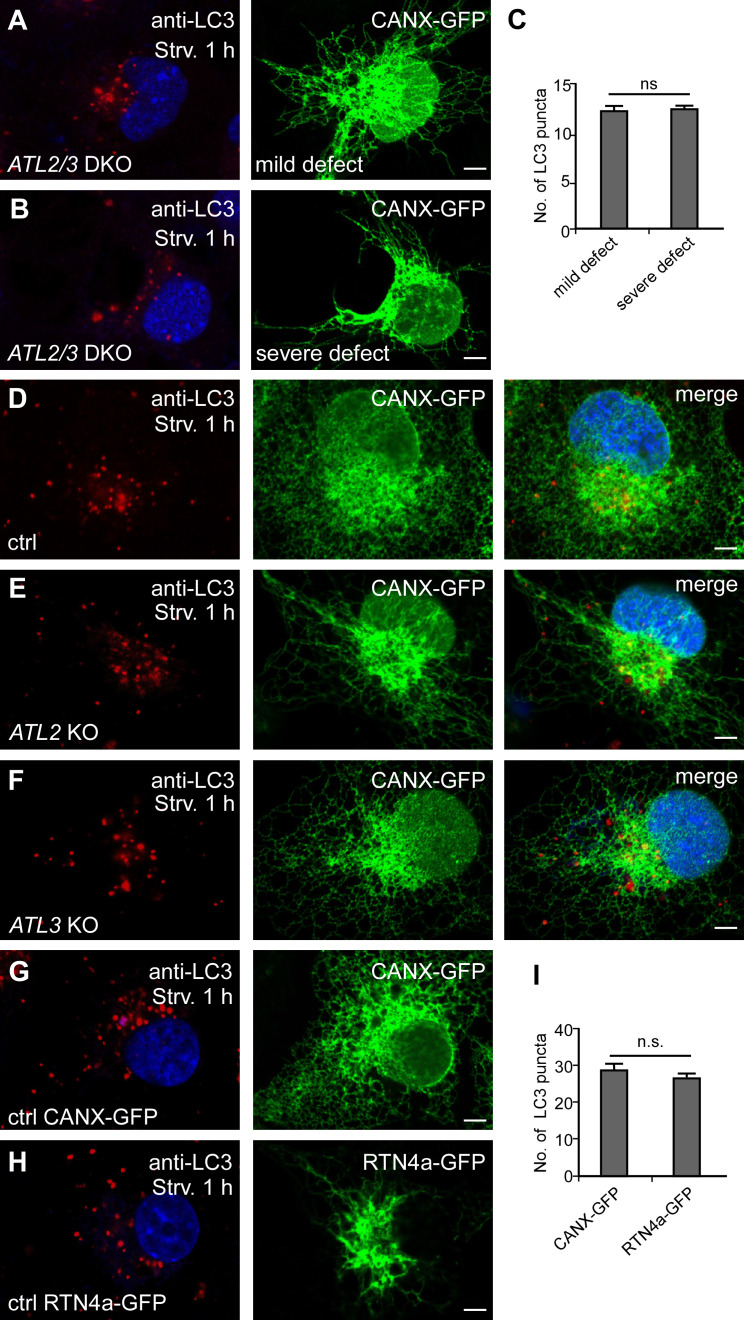

The reduced formation of LC3 puncta in ATL2/3 DKO cells is not associated with altered ER morphology

In ATL2/3 DKO cells, the ER forms long, unbranched tubules, and the severity of the ER morphology defects varies among cells (Hu et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2013). We found that the number of LC3 puncta was the same in ATL2/3 DKO cells with a severe unbranched ER phenotype and in cells with a less evident ER morphology defect (Fig. S1, A–C). The unbranched ER morphology defect was also evident in ATL2, but not ATL3, single KO cells; however, autophagy was not significantly affected in ATL2 or ATL3 single KO cells compared with control cells (Fig. 1 H; and Fig. S1, D–F). The number of LC3 puncta was not evidently changed in cells overexpressing RNT4a, which caused an unbranched ER phenotype as in ATL2/3 DKO cells (Fig. S1, G–I). Therefore, the reduced number of LC3-labeled autophagic structures in ATL2/3 DKO cells is not associated with alterations in the ER morphology.

Figure S1.

ATL2/3 DKO cells show a reduction in LC3 puncta that is not associated with the altered ER morphology. (A–C) The number of LC3 puncta is not significantly different in ATL2/3 DKO cells with a severe or mild ER morphology defect. (A) A mild ER defect. (B) A severe defect with long, unbranched ER tubules that concentrate at the perinuclear region. Cells were starved for 1 h to induce autophagy. Quantitative data are shown in C as mean ± SEM (n = 20 cells in each group). Scale bars, 5 µm. (D–F) Compared with control cells (D), ER morphology is evidently changed in ATL2 KO cells (E) but is largely normal in ATL3 KO cells (F). The formation of LC3 puncta is not affected in ATL2 or ATL3 single KO cells. Scale bars, 5 µm. (G–I) Compared with control cells (G), ER morphology is altered in cells expressing RTN4a-GFP (H), while the number of LC3 puncta is not changed (H). Long, unbranched ER tubules are present and concentrate at the perinuclear region in RNT4a-GFP–expressing cells. Quantitative data are shown in I as mean ± SEM (n = 20 cells in each group). Scale bars, 5 µm. ctrl, control; Strv, starved.

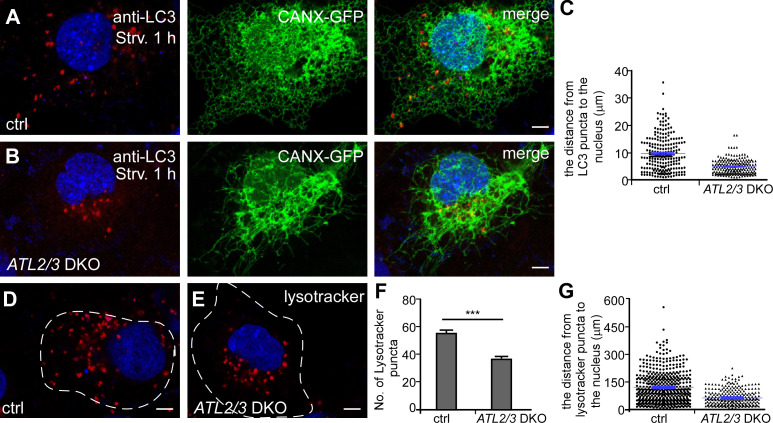

We noticed that in ATL2/3 DKO cells, LC3 puncta were concentrated at the perinuclear region, even in cells with a mild ER morphology defect (Fig. 2, A–C; and Fig. S1, A and B). In control cells, LysoTracker-stained lysosomes were abundant and scattered throughout the cytosol, while in ATL2/3 DKO cells, they were fewer in number and exhibited perinuclear distribution (Fig. 2, D–G). Thus, depletion of ATL2/3 affects the distribution of LC3 puncta and lysosomes.

Figure 2.

The distribution of autophagosomes and lysosomes is affected in ATL2/3 DKO cells. (A–C) Compared with control cells (A), LC3 puncta are concentrated at the perinuclear region in ATL2/3 DKO COS-7 cells (B). The column scatter charts in C show the distances from LC3 puncta to the nearest DAPI-labeled nucleus. Mean ± SEM is shown in blue (n = 218 puncta from 10 cells in control cells, n = 96 puncta from 10 cells in ATL2/3 DKO cells). Scale bars, 5 µm. (D–G) Compared with control cells (D), the number of LysoTracker-stained puncta is decreased in ATL2/3 DKO COS-7 cells (E). LysoTracker-stained puncta are also concentrated in the perinuclear region in ATL2/3 DKO cells (E). (F) Quantification of the number of LysoTracker-stained lysosomes as mean ± SEM (n = 10 cells in each group). ***, P < 0.001. The column scatter charts in G show the distances from LysoTracker puncta to the nucleus. The data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 510 puncta from 10 cells in control cells, n = 269 puncta from 10 cells in ATL2/3 DKO cells). The dashed line represents the cell outline. Scale bars, 5 µm. ctrl, control; Strv, starved.

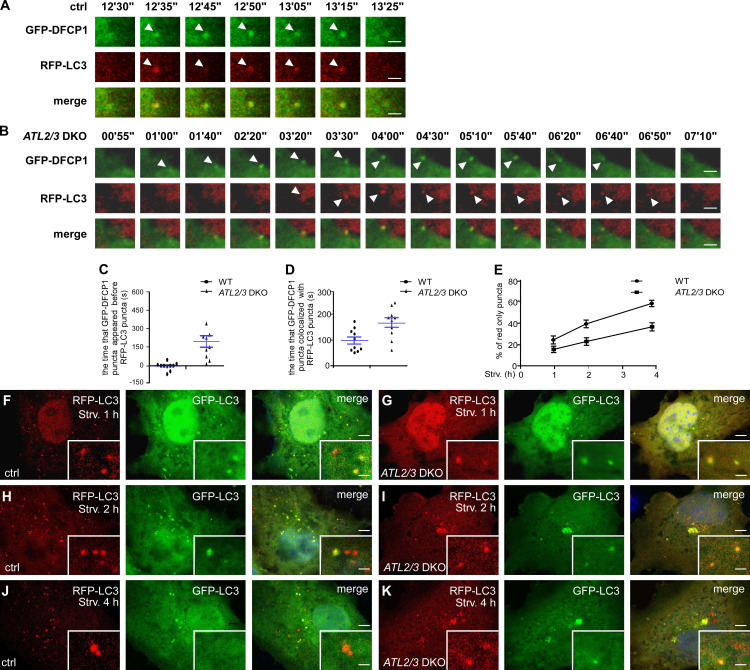

The initiation of IMs is slowed down in ATL2/3 DKO cells

Autophagy occurs in a stepwise manner, involving formation of omegasomes and IMs, fusion of autophagosomes with endosomes to form amphisomes, and formation of autolysosomes (Zhao and Zhang, 2019). The kinetics of starvation-induced autophagy are highly reproducible in a given cell type. LC3-labeled IMs associate with the omegasome marker DFCP1, while LC3-labeled closed autophagosomes, amphisomes, and autolysosomes are separate from the DFCP1 puncta. We examined the dynamic association of GFP-DFCP with RFP-LC3 in control and ATL2/3 DKO cells. Upon starvation, GFP-DFCP1 puncta and RFP-LC3 puncta appeared almost simultaneously in control cells, while RFP-LC3 appeared later than GFP-DFCP1 in ATL2/3 DKO cells (Fig. 3, A–C). GFP-DFCP1 puncta and RFP-LC3 puncta were colocalized in both control and ATL2/3 DKO cells. The association time of GFP-DFCP1 with RFP-LC3 in ATL2/3 DKO cells was significantly longer than in control cells (Fig. 3, A, B, and D). These results indicate that the initiation and expansion of IMs is retarded in ATL2/3 DKO cells.

Figure 3.

IM initiation is slowed down in ATL2/3 DKO cells. (A–D) The temporal appearance of LC3 puncta and DFCP1 puncta in control and ATL2/3 DKO cells. RFP-LC3 puncta and GFP-DFCP1 emerge almost simultaneously in control cells (A), while RFP-LC3 puncta appear later than GFP-DFCP1 in ATL2/3 DKO cells (B). The duration of colocalization of GFP-DFCP1 and RFP-LC3 is also longer in ATL2/3 DKO cells (B) than in control cells (A). Control and ATL2/3 DKO cells were transfected with GFP-DFCP1 and RFP-LC3, treated with HBSS starvation medium, and then monitored using live-cell imaging. Quantitative data in C and D are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 10 cells in each group). Scale bars, 2 µm. (E–K) Formation of red-only puncta in the RFP-GFP-LC3 assay at different time points after starvation in control and ATL2/3 DKO cells. Compared with control cells (F, H, and J), the percentages of red-only puncta are less in ATL2/3 DKO (G, I, and K) cells at the same time points after starvation. Quantitative data in E are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 20 cells in each group). Scale bars, 5 µm; inset scale bars, 0.5 µm. ctrl, control; Strv, starved.

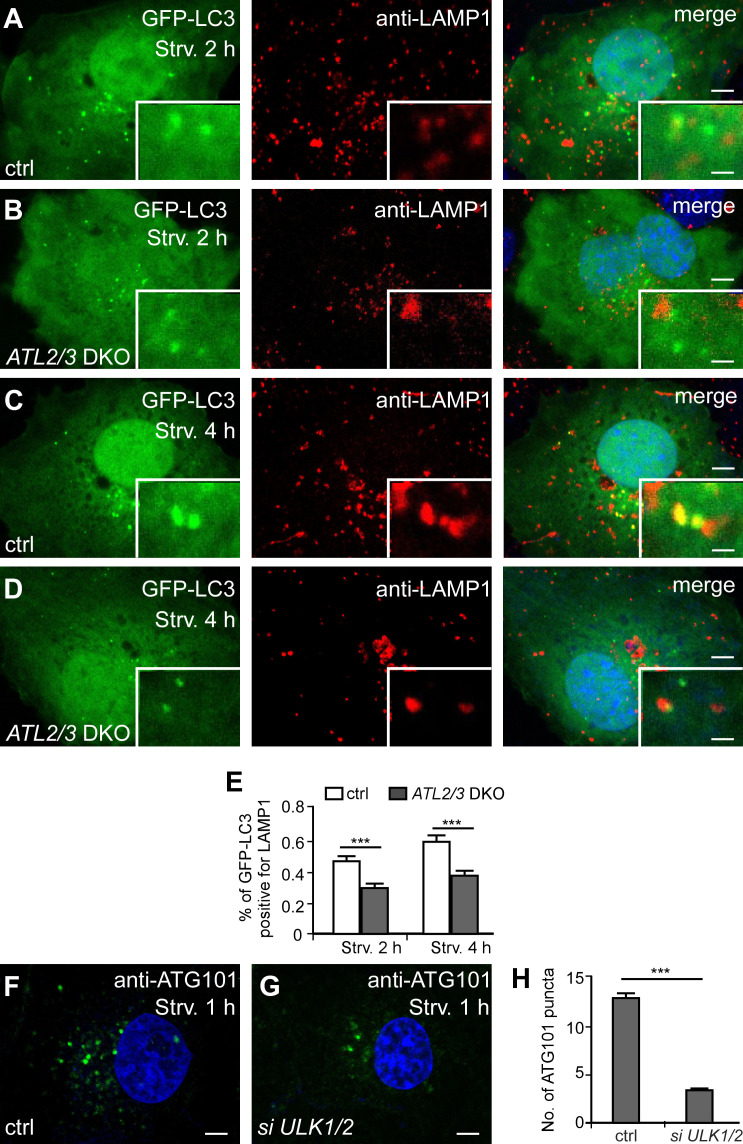

We then used an RFP-GFP-LC3 reporter to monitor the progression of autophagic flux. GFP signals are quenched in acidified environments. Therefore, yellow RFP-GFP-LC3 puncta represent IMs and immature autophagosomes, while red puncta indicate acidified amphisomes and autolysosomes (Kimura et al., 2007). In control cells, the percentage of red-only puncta increased as the starvation time increased, but in ATL2/3 DKO cells, the percentage was less at the same starvation time points (Fig. 3, E–K). We further determined the association of LC3 puncta with late endosomes/lysosomes. After 2 h of starvation, GFP-LC3 puncta partially colocalized with LAMP1-labeled late endosomes/lysosomes, and the percentage of colocalizing puncta was increased after 4 h of starvation in control cells (Fig. S2, A, C, and E). In ATL2/3 DKO cells, the colocalization ratio was also increased as starvation proceeded, but it was lower than in control cells at the same starvation time points (Fig. S2, B, D, and E). These results indicate that the progression of the flux is slowed down by ATL2/3 depletion, which could be due to impaired autophagosome formation and/or autophagosome maturation.

Figure S2.

The autophagic flux is delayed in ATL2/3 DKO cells. (A–E) Compared with control cells (A and C), the percentage of GFP-LC3 puncta that closely associate or colocalize with LAMP1 puncta is less in ATL2/3 DKO (B and D) after 2-h starvation (A and B) or after 4-h starvation (C and D). Quantitative data are shown in E as mean ± SEM (n = 20 cells in each group). Scale bars, 5 µm; inset scale bars, 0.5 µm. (F and G) Compared with control cells (F), the number of ATG101 puncta is dramatically decreased in ULK1/2 KD cells (G). Scale bars, 5 µm. (H) Quantitative data for F and G are shown in H as mean ± SEM (n = 30 cells in each group). ***, P < 0.001. ctrl, control; Strv, starved.

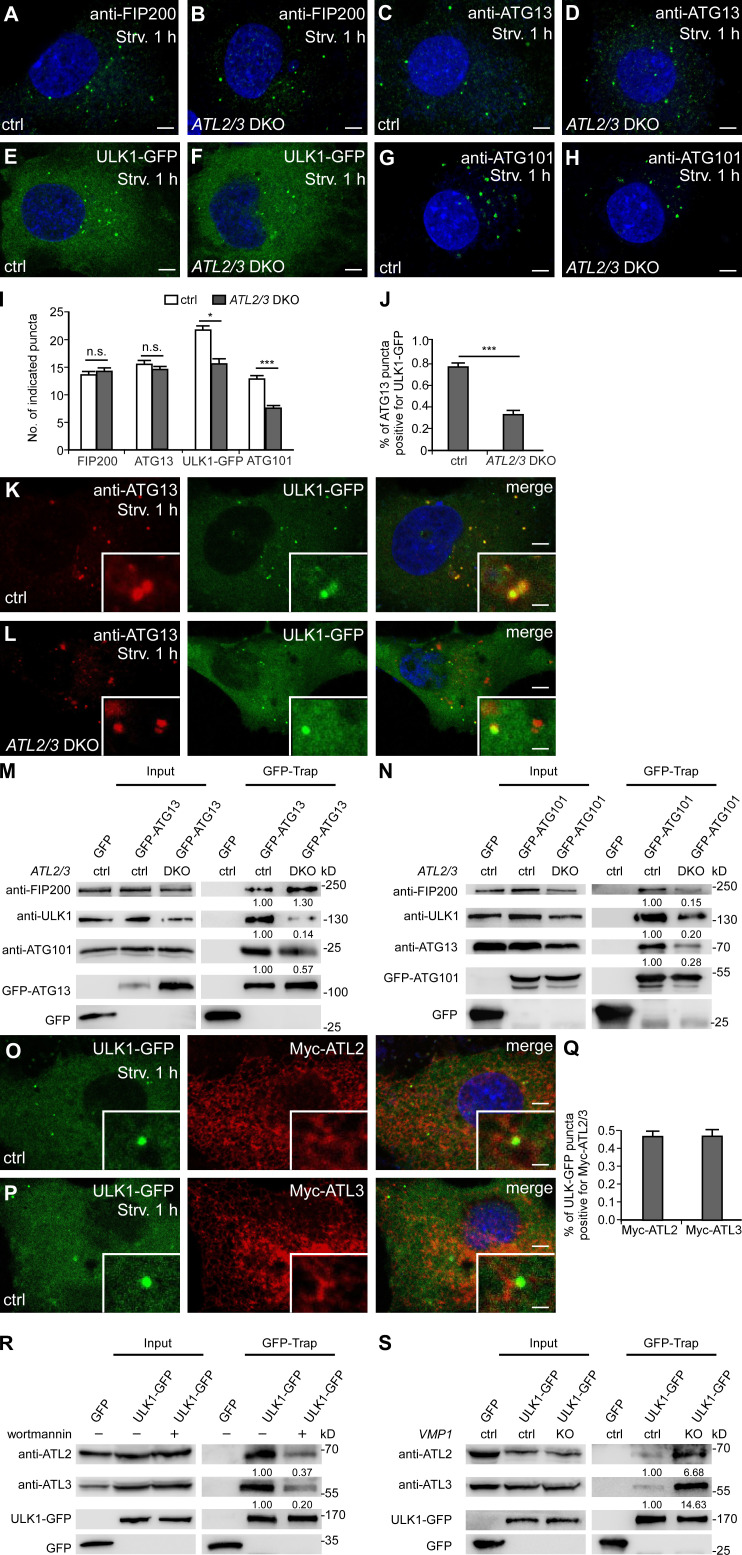

ATL2/3 contribute to the ER targeting of ULK1 and ATG101

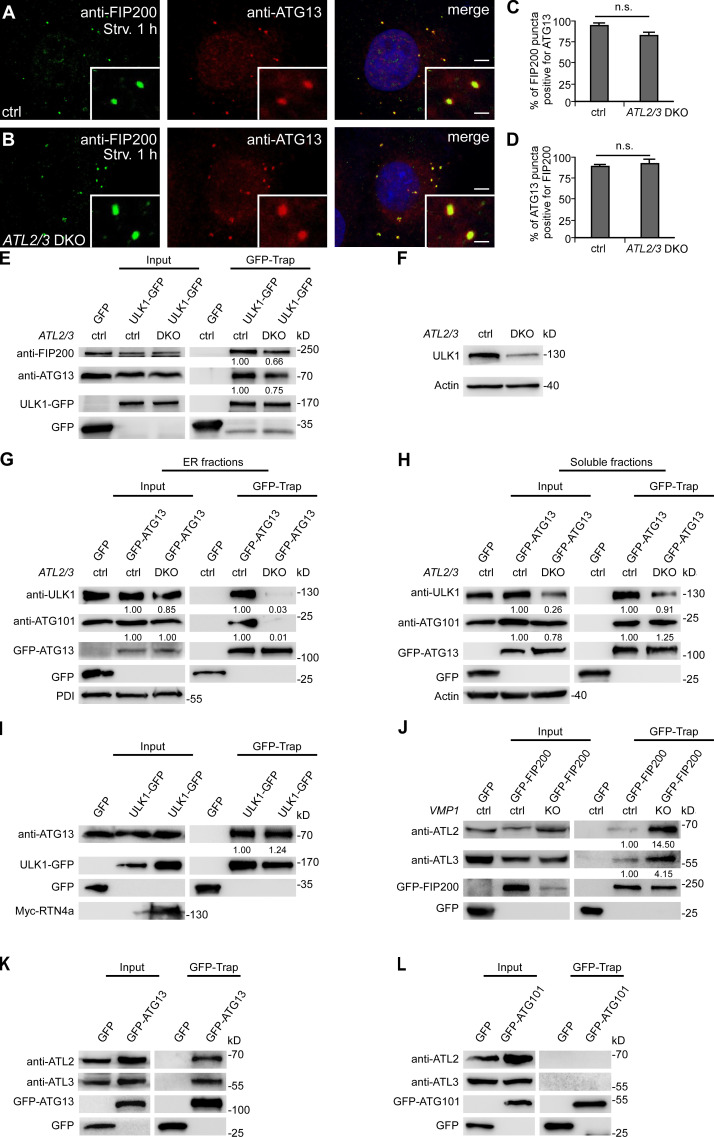

We next investigated which step of autophagosome initiation is impaired. Upon autophagy induction, FIP200 acts at the most upstream step in recruiting other components of the ULK1 complex to the ER (Hara et al., 2008; Itakura and Mizushima, 2010; Nishimura et al., 2017). Compared with control cells, the numbers of anti-FIP200– and anti-ATG13–stained puncta in ATL2/3 DKO cells remained largely unchanged (Fig. 4, A–D and I), while the numbers of ULK1-GFP and anti-ATG101–stained puncta were decreased in ATL2/3 DKO cells (Fig. 4, E–I). We found that in ULK1/2 knockdown (KD) cells, the number of ATG101 puncta was also dramatically decreased, suggesting that deletion of ATL2/3 may indirectly impair ATG101 by affecting ULK1 (Fig. S2, F–H). Targeting of the ULK1 complex components to the FIP200-labeled autophagosome formation sites is dynamic. The colocalization of ATG13 with FIP200 puncta was similar in control and ATL2/3 DKO cells (Fig. S3, A–D). However, the number of ATG13 puncta that were also positive for ULK1-GFP was decreased in ATL2/3 DKO cells (Fig. 4, J–L). Thus, depletion of ATL2/3 impairs the recruitment of ULK1 to ATG13 puncta.

Figure 4.

ATL2/3 contribute to the recruitment of ULK1 to the autophagosome formation sites specified by FIP200/ATG13. (A and B) Compared with control cells (A), puncta formed by endogenous FIP200 (detected by anti-FIP200) show no evident change in ATL2/3 DKO COS-7 cells (B) after 1 h of starvation. Scale bars, 5 µm. (C and D) Compared with control cells (C), puncta labeled by anti-ATG13 antibody are not changed in ATL2/3 DKO COS-7 cells (D) after 1 h of starvation. Scale bars, 5 µm. (E and F) ULK1-GFP forms fewer puncta in ATL2/3 DKO COS-7 cells (F) compared with control cells (E) after 1 h of starvation. Scale bars, 5 µm. (G and H) Compared with control cells (G), fewer puncta are labeled by anti-ATG101 antibody in ATL2/3 DKO COS-7 cells (H) after 1 h of starvation. Scale bars, 5 µm. (I) Quantitative data for A–H are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 30 cells in each group). *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001. (J–L) The relationship between ATG13 puncta and ULK1-GFP puncta in control (K) and ATL2/3 DKO COS-7 cells (L) after 1 h of starvation. The percentage of ATG13 puncta positive for ULK1-GFP is decreased in ATL2/3 DKO cells (L) compared with control cells (K) after 1 h of starvation. Quantitative data are shown in J as mean ± SEM (n = 20 cells in each group). ***, P < 0.001. Scale bars, 5 µm; inset scale bars, 0.5 µm. (M) Levels of endogenous ULK1 and ATG101 coprecipitated by GFP-ATG13 are decreased in ATL2/3 DKO COS-7 cells compared with control cells in GFP-Trap assays, while levels of endogenous FIP200 precipitated by GFP-ATG13 are not reduced. Quantifications of ULK1, ATG101, and FIP200 levels (normalized by GFP-ATG13 levels) are also shown. (N) Levels of endogenous FIP200, ULK1, and ATG13 coprecipitated by GFP-ATG101 are dramatically decreased in ATL2/3 DKO COS-7 cells compared with control cells in GFP-Trap assays. Quantifications of FIP200, ULK1, and ATG13 levels (normalized by GFP-ATG101 levels) are also shown. (O–Q) A subset of ULK1-GFP punctate structures accumulate at distinct Myc-ATL2 (O) and Myc-ATL3 (P) puncta in control cells after 1 h of starvation. Myc-ATL2 and Myc-ATL3 puncta are defined as having a fluorescence intensity that is clearly stronger than the surrounding area. Quantitative data are shown in Q as mean ± SEM (n = 15 cells in each group). Scale bars, 5 µm; inset scale bars, 0.5 µm. (R) In cells treated with wortmannin, levels of endogenous ATL2 and ATL3 precipitated by ULK1-GFP are dramatically decreased compared with untreated cells. Quantification of ATL2 and ATL3 levels (normalized by ULK1-GFP levels) are also shown. (S) Levels of endogenous ATL2 and ATL3 precipitated by ULK1-GFP are increased in VMP1 KO COS-7 cells compared with control cells in GFP-Trap assays. Quantifications of ATL2 and ATL3 levels (normalized by ULK1-GFP levels) are also shown. ctrl, control; Strv, starved.

Figure S3.

ATL2/3 contribute to the recruitment of ULK1 by ATG13. (A–D) The percentage of FIP200 puncta positive for ATG13 or the percentage of ATG13 puncta positive for FIP200 is not changed in ATL2/3 DKO COS-7 cells (B) compared with control cells (A) after 1 h of starvation. Quantitative data are shown in C and D as mean ± SEM (n = 17 cells for A, n = 19 cells for B). Scale bars, 5 µm; inset scale bars, 0.5 µm. (E) Levels of endogenous FIP200 and ATG13 coprecipitated by ULK1-GFP are decreased in ATL2/3 DKO COS-7 cells compared with control cells in GFP-Trap assays. Control or ATL2/3 DKO COS-7 cells were transfected with ULK1-GFP. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using GFP-Trap and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-FIP200 or anti-ATG13 antibody. Quantifications of ATG13 and FIP200 levels (normalized by ULK1-GFP levels) are also shown. (F) Levels of ULK1 protein are decreased in ATL2/3 DKO cells compared with control cells. Quantification of ULK1 levels (normalized by actin levels) is also shown. (G) In ER fractions, the levels of endogenous ULK1 and ATG101 proteins are not evidently changed in ATL2/3 DKO cells. Compared with control cells, the interactions of GFP-ATG13 with ULK1 and ATG101 are decreased in ATL2/3 DKO cells. Quantification of endogenous ULK1 and ATG101 are normalized by protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) levels. Quantifications of ULK1 and ATG101 trapped by GFP-ATG13 are first normalized by GFP-ATG13 protein levels and further normalized by their respective input samples. (H) In soluble fractions, the endogenous ULK1 protein level is decreased in ATL2/3 DKO cells, while the ATG101 protein level is only slightly reduced. Compared with control cells, the interactions of GFP-ATG13 with ULK1 and ATG101 are not changed obviously in ATL2/3 DKO cells. Quantifications of endogenous ULK1 and ATG101 are normalized by actin levels. Quantifications of ULK1 and ATG101 trapped by GFP-ATG13 are first normalized by GFP-ATG13 protein levels and further normalized by their respective input samples. (I) Levels of endogenous ATG13 precipitated by ULK1-GFP are not decreased in cells expressing Myc-RTN4a compared with control cells in GFP-Trap assays. Quantification of ATG13 (normalized by ULK1-GFP levels) is also shown. (J) Levels of ATL2 and ATL3 precipitated by GFP-FIP200 are increased in VMP1 KO COS-7 cells compared with control cells in GFP-Trap assays. Control or VMP1 KO cells were transfected with GFP-FIP200. Lysates were immunoprecipitated using GFP-Trap and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-ATL2 or anti-ATL3 antibody. Quantifications of ATL2 and ATL3 levels (normalized by GFP-FIP200 levels) are also shown. (K) Endogenous ATL2 and ATL3 are precipitated by GFP-ATG13 in GFP-Trap assays. (L) GFP-ATG101 fails to precipitate endogenous ATL2 and ATL3 in GFP-Trap assays. ctrl, control; Strv, starved.

We next examined the formation of the ULK1 complex in ATL2/3 DKO cells. Compared with control cells, levels of endogenous FIP200 coimmunoprecipitated by GFP-ATG13 remained unaltered in GFP-Trap assays, while levels of endogenous ULK1 and ATG101 coprecipitated by GFP-ATG13 were dramatically decreased in ATL2/3 DKO cells (Fig. 4 M). Levels of endogenous FIP200 and ATG13 coprecipitated by ULK1-GFP were decreased in ATL2/3 DKO cells (Fig. S3 E). Levels of endogenous FIP200, ULK1, and ATG13 precipitated by GFP-ATG101 were also reduced in the DKO cells (Fig. 4 N). The ULK1 protein level was decreased in ATL2/3 DKO cells (Fig. S3 F), which is consistent with the previous notion that ATG13 is involved in stabilizing ULK1 (Hosokawa et al., 2009b). The ULK1 complex is primarily present in the cytosol and translocates to membranes during starvation (Chan et al., 2009; Hosokawa et al., 2009b). We next examined whether ATL2/3 regulate the assembly of this complex on the ER membrane or in the cytosol. We fractionated the ER from control and ATL2/3 DKO cellular extracts to examine the interactions between GFP-ATG13 and ULK1/ATG101 in the ER and soluble fractions. In the ER fractions, compared with control cells, the levels of endogenous ULK1 and ATG101 proteins were not obviously changed in ATL2/3 DKO cells. However, the interactions of GFP-ATG13 with endogenous ULK1 and ATG101 were dramatically decreased in ATL2/3 DKO cells (Fig. S3 G). In soluble fractions, the endogenous ULK1 level was dramatically decreased, while the ATG101 level was only slightly reduced in ATL2/3 DKO cells. The interactions of GFP-ATG13 with ULK1 and ATG101 did not evidently change when they were normalized by their respective input protein levels (Fig. S3 H).

In cells expressing Myc-RTN4a, which exhibited an extensive unbranched ER phenotype, the interaction of ULK1 with ATG13 in the coimmunoprecipitation assays was not decreased compared with control cells (Fig. S3 I). These results suggest that ATL2/3 contribute to the recruitment and/or stabilization of ULK1 and ATG101 to the puncta on the ER formed by the FIP200–ATG13 subcomplex. This function of ATL2/3 is likely independent of their function in controlling ER morphology.

ATL2/3 interact with components of the ULK1 complex

We determined whether ATL2/3 interact with components of the ULK1 complex. A subset of ULK1-GFP puncta was colocalized with structures with intense Myc-ATL2/3 signals (Fig. 4, O–Q). In coimmunoprecipitation assays, we found that endogenous ATL2 and ATL3 were coprecipitated by ULK1-GFP, GFP-FIP200, and GFP-ATG13 (Fig. 4 S; and Fig. S3, J and K). However, GFP-ATG101 failed to precipitate endogenous ATL2 and ATL3 (Fig. S3 L). PI(3)P has been shown to stabilize the association of puncta formed by the ULK1 complex on the ER (Karanasios et al., 2013). Upon treatment with the PI(3)P kinase inhibitor wortmannin, the interactions of ULK1 with ATL2/3 were greatly attenuated (Fig. 4 R), suggesting that PI(3)P may contribute to their interactions and/or stabilization. These results indicate that ATL2/3 interact with the ULK1 complex.

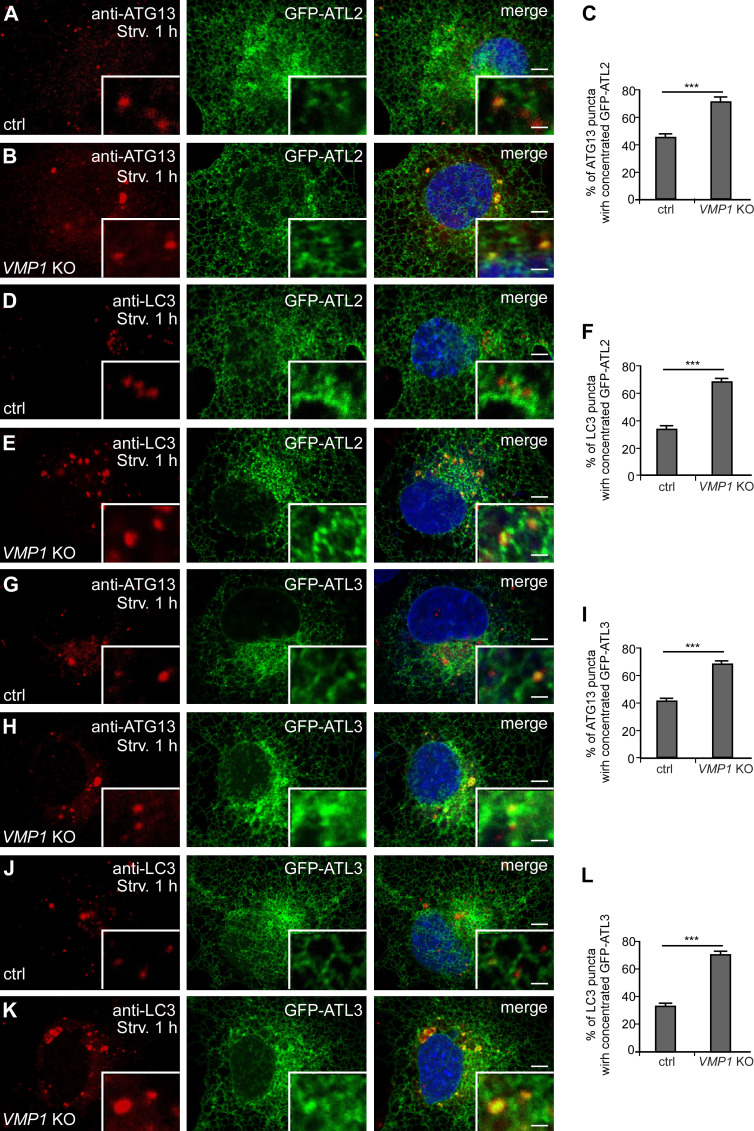

The IM stably associates with the ER in VMP1 KO cells (Zhao et al., 2017). In control cells, a subset of ATG13 or LC3 puncta were colocalized with structures with intense GFP-ATL2/3 signals, and the colocalization ratio was increased in VMP1 KO cells (Fig. S4, A–L). The interactions of ATL2/3 with ULK1-GFP and GFP-FIP200 in VMP1 KO cells were much more prominent in GFP-Trap assays (Fig. 4 S and Fig. S3 J). These results suggest that ATL2/3 are likely to concentrate at autophagosome formation sites specified by the ULK1 complex on the ER.

Figure S4.

GFP-ATL2 and 3 are enriched at the autophagosome formation sites. (A–C) Compared with control cells (A), more ATG13 punctate structures accumulate at distinct GFP-ATL2 puncta in VMP1 KO cells after 1 h of starvation. GFP-ATL2 puncta are defined as having a fluorescence intensity that is clearly stronger than the surrounding area. Quantitative data are shown in C as mean ± SEM (n = 19 cells in each group). Scale bars, 5 µm; inset scale bars, 0.5 µm. (D–F) Compared with control cells (D), more LC3 puncta accumulate at distinct GFP-ATL2 puncta in VMP1 KO cells (E) after 1 h of starvation. Quantitative data are shown in F as mean ± SEM (n = 20 cells in each group). Scale bars, 5 µm; inset scale bars, 0.5 µm. (G–I) Compared with control cells (G), more ATG13 puncta accumulate at distinct GFP-ATL3 puncta (H) after 1 h of starvation. Quantitative data are shown in I as mean ± SEM (n = 19 cells in each group). Scale bars, 5 µm; inset scale bars, 0.5 µm. (J–L) Compared with control cells (J), more LC3 puncta accumulate at distinct GFP-ATL3 puncta after 1 h of starvation in VMP1 KO cells (K). Quantitative data are shown in L as mean ± SEM (n = 20 cells in each group). Scale bars, 5 µm; inset scale bars, 0.5 µm. ***, P < 0.001. ctrl, control; Strv, starved.

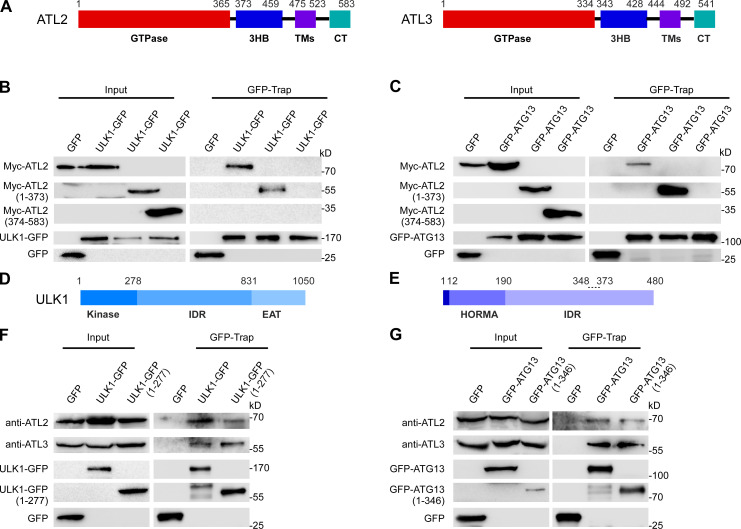

ATL2/3 directly interact with ULK1 and ATG13 via the GTPase domain

ATL proteins contain an N-terminal GTPase domain, a three-helix bundle region (3HB), two membrane-embedded regions, and a C-terminal tail (Fig. 5 A; Wang and Rapoport, 2019). In GFP-Trap assays, the N-terminal GTPase domains of ATL2 and ATL3 (aa 1–373 of ATL2 and aa 1–343 of ATL3) were coprecipitated by GFP-ATG13 and ULK1-GFP, while ATL2 and ATL3 with the N terminus deleted showed no interactions (Fig. 5, B and C; and Fig. S5, A and B).

Figure 5.

ATL2/3 interact with ULK1 and ATG13. (A) Schematic illustration of the domains in ATL2 and ATL3. ATL2/3 contain an N-terminal GTPase domain, a 3HB, two membrane-embedded regions (TMs), and a C-terminal tail (CT). (B and C) In GFP-Trap assays, the N terminus of Myc-ATL2(1–373) is precipitated by ULK1-GFP (B) and GFP-ATG13 (C). HEK293T cells were transfected with ULK1-GFP (B) or GFP-ATG13 (C) together with Myc-tagged full-length or fragments of ATL2. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using GFP-Trap and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Myc antibody. (D and E) Schematic illustration of the domains in ULK1 (D) and ATG13 (E). ULK1 contains an N-terminal kinase domain, a long IDR, and a C-terminal EAT domain. ATG13 contains a HORMA domain in the N-terminal region, which dimerizes with the HORMA domain of ATG101, and a long C-terminal IDR. The IDR of ATG13 interacts with FIP200 and ULK1. The dotted line (348–373) indicates the FIP200-binding motif, and the last 3 aa in the C terminus constitute the ULK1-binding motif. (F and G) Endogenous ATL2/3 are precipitated by the kinase domain of ULK1 and the 1–346 fragment of ATG13. HEK293T cells were transfected with full-length or fragments of ULK1-GFP or GFP-ATG13. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using GFP-Trap and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-ATL2 or anti-ATL3 antibody.

Figure S5.

ATL2/3 interact with ULK1 and ATG13 and function partially redundantly with VAPA/B in autophagy. (A and B) The N terminus of Myc-ATL3(1–343) is precipitated by ULK1-GFP (A) and GFP-ATG13 (B) in GFP-Trap assays. HEK293T cells were transfected with ULK1-GFP or GFP-ATG13 together with Myc-tagged full-length or fragments of ATL3. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using GFP-Trap and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Myc antibody. (C and D) In vitro pulldown assay shows that the N termini of ATL2(1–474) and ATL3(1–443) directly bind to ULK1(1–277) and ATG13(1–346). Asterisks indicate the bands corresponding to the GST fusion proteins. (E and F) In vitro pulldown assays show that the interactions of GST-ATG13(1–346) with HA-ATL2(1–474) (E) and HA-ATL3(1–443) (F) are not evidently decreased by addition of MBP-ULK1(1–277) into the reactions. Asterisks indicate the bands corresponding to the GST fusion proteins. (G–I) The formation of LC3 puncta is similar in ULK1/2 KD cells (G) and in ATL2/3 DKO cells with simultaneous KD of VAPA/B (H). Quantitative data are shown in I as mean ± SEM (n = 20 cells in each group). Scale bars, 5 µm. (J) Compared with control cells, LC3-II/LC3-I ratios are decreased in ULK1/2 KD cells and ATL2/3 DKO cells with simultaneous KD of VAPA/B. Quantifications of LC3-II/LC3-I ratios are also shown (normalized by actin level). (K and L) Compared with VMP1 KD in control cells, levels of WIPI2 precipitated by GFP-VAPA (K) and GFP-VAPB (L) are dramatically decreased in VMP1 KD cells with simultaneous depletion of ATL2/3 in GFP-Trap assays. Quantifications of WIPI2 levels (normalized by GFP-VAPA and GFP-VAPB levels) are also shown. (M) Levels of Myc-VAPA coprecipitated by GFP-ORP1L remain unchanged in ATL2/3 DKO COS-7 cells compared with control cells in GFP-Trap assays. Quantifications of Myc-VAPA levels (normalized by GFP-ORP1L levels) are also shown. (N) Levels of PTPIP51 coprecipitated by GFP-VAPB are not evidently altered in ATL2/3 DKO COS-7 cells compared with control cells in GFP-Trap assays. Quantifications of PTPIP51 levels (normalized by GFP-VAPB levels) are also shown. ctrl, control; NC, negative control; Strv, starved.

We also delineated the domains in ULK1 and ATG13 that bind to ATL2/3. ULK1 contains an N-terminal kinase domain, a long IDR, and a C-terminal EAT domain (Fig. 5 D; Chan et al., 2009; Shi et al., 2020). We found that endogenous ATL2 and ATL3 were coimmunoprecipitated by the kinase domain of ULK1 (aa 1–277; Fig. 5 F). ATG13 contains an ATG101-binding HORMA domain (aa 12–190), a long IDR that contains an FIP200-binding motif (aa 348–373), and a C-terminal ULK1/2-binding site (Fig. 5 E; Qi et al., 2015; Wallot-Hieke et al., 2018). We found that an ATG13 fragment (aa 1–346) bound to endogenous ATL2 and ATL3 in GFP-Trap assays (Fig. 5 G). In vitro pulldown assays showed that GST-ULK1(1–277) and GST-ATG13(1–346) bound to HA-ATL2(1–474) and HA-ATL3(1–443) (Fig. S5, C and D). These results suggest that ATL2 and ATL3 directly interact with ULK1 and ATG13. The binding of GST-ATG13(1–346) to HA-ATL2(1–474) and HA-ATL3(1–443) was not evidently decreased with the addition of MBP-ULK1(1–277) into the in vitro pulldown reactions (Fig. S5, E and F). This suggests that ATG13 and ULK1 can bind to ATL2/3 simultaneously.

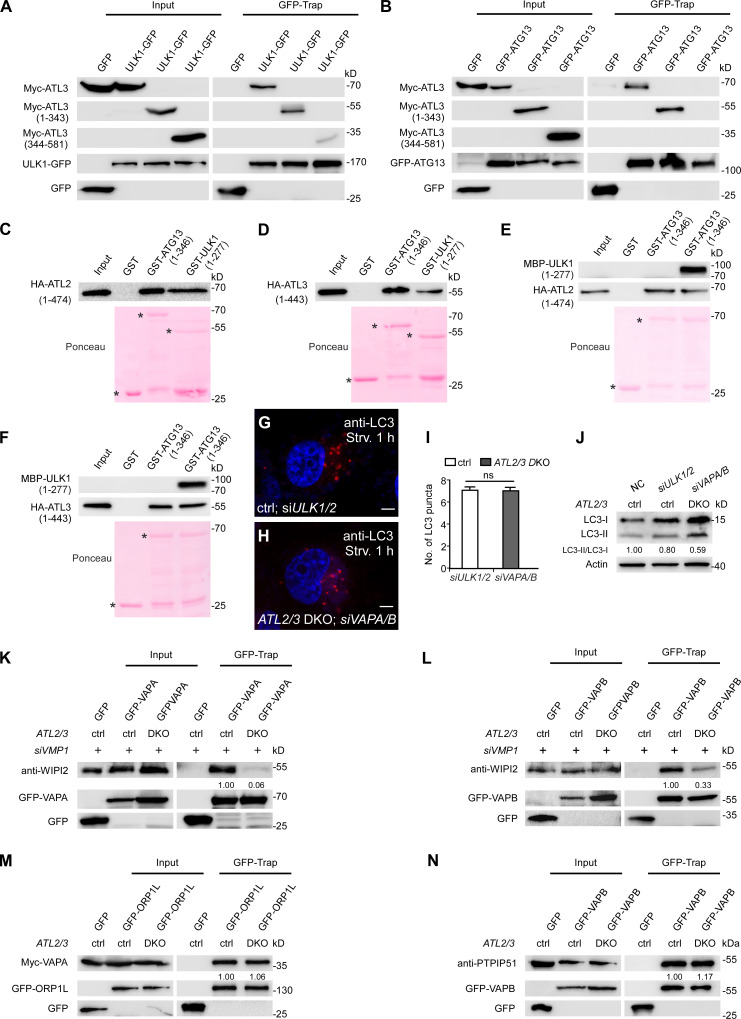

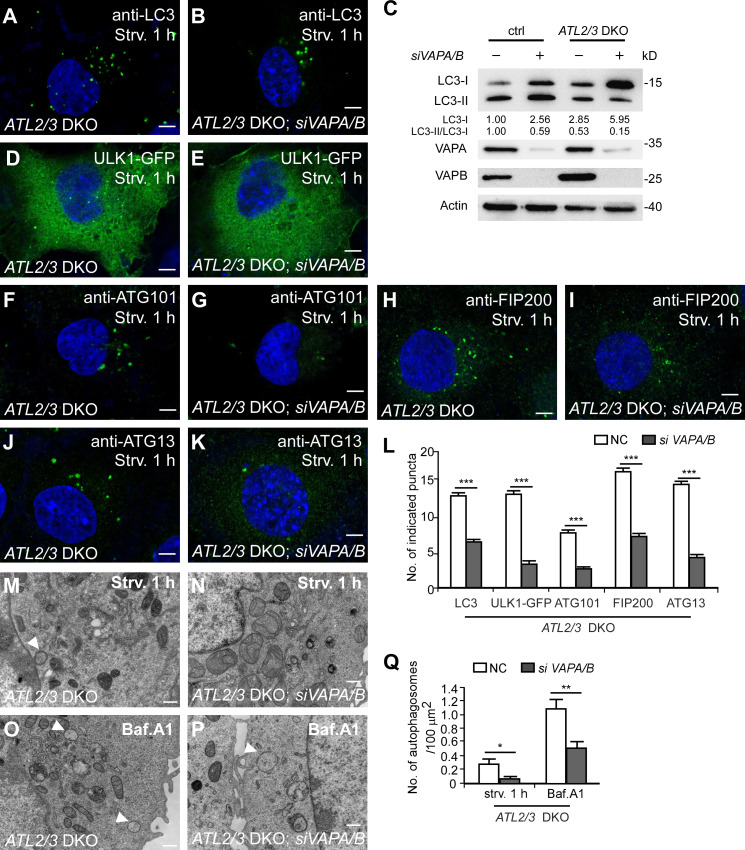

ATL2/3 and VAPA/B function together for ER targeting of the ULK1 complex

The ER-localized proteins VAPA and VAPB stabilize the ULK1–FIP200 interaction and contribute to the formation of the ER–IM contact (Zhao et al., 2018). Compared with VAPA/B KD or ATL2/3 DKO cells, simultaneous depletion of VAPA/B in ATL2/3 DKO cells further reduced the number of LC3 puncta (Fig. 6, A, B, and L). Levels of LC3-I were more dramatically increased, and the ratio of LC3-II/LC3-I was further decreased (Fig. 6 C). The number of LC3 puncta and the ratio of LC3I-I/LC3-I in ATL2/3 DKO; VAPA/B KD cells resembled that in ULK1/2 KD cells (Fig. S5, G–J). The numbers of ULK1-GFP puncta and ATG101 puncta in ATL2/3 DKO cells were further reduced by simultaneously depleting VAPA/B (Fig. 6, D–G and L). The numbers of FIP200 puncta and ATG13 puncta were not evidently affected by depletion of either VAPA/B or ATL2/3; however, their numbers were dramatically reduced in ATL2/3 DKO cells with simultaneous depletion of VAPA/B (Fig. 6, H–L). EM analysis revealed that KD of VAPA/B further decreased the number of autophagosomes in ATL2/3 DKO cells (Fig. 6, M–Q). These results suggest that VAPA/B and ATL2/3 act in a partially redundant manner for the ER targeting of the ULK1 complex.

Figure 6.

ATLs and VAPs act partially redundantly in mediating the formation of FIP200/ULK1 puncta. (A and B) Compared with ATL2/3 DKO COS-7 cells (A), the number of LC3 puncta is further decreased by simultaneous KD of VAPA/B (B). Scale bars, 5 µm. (C) Immunoblotting assays showing LC3 levels in control and ATL2/3 DKO COS-7 cells with or without KD of VAPA/B. Quantifications of LC3-I and LC3-II/LC3-I ratios are also shown (normalized by actin level). The level of LC3-I and the ratio of LC3-II/LC3-I in control cells is set to 1.00. (D and E) Compared with ATL2/3 DKO COS-7 cells (D), the number of ULK1-GFP puncta is much lower after simultaneous KD of VAPA/B (E). Scale bars, 5 µm. (F–K) Compared with ATL2/3 DKO COS-7 cells (F, H, and J), the numbers of ATG101 puncta, FIP200 puncta, and ATG13 puncta are dramatically decreased by simultaneous KD of VAPA/B (G, I, and K). Scale bars, 5 µm. (L) Quantitative data for A and B and D–K are shown in L as mean ± SEM (n = 32 cells in A and B, n = 26 cells in D, n = 21 cells in E, n = 20 cells in F–K). ***, P < 0.001. (M–Q) EM micrographs showing autophagic structures in ATL2/3 DKO COS-7 cells (M and O) and ATL2/3 DKO cells with simultaneous depletion of VAPA/B (N and P) after 1 h of starvation (M and N) or after Bfa.A1 treatment (O and P). Arrowheads indicate autophagosomes. Quantifications of the numbers of autophagosomes are shown in Q as mean ± SEM (n = 50 sections in each group, one section for each cell). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Scale bars, 0.5 µm. ctrl, control; NC, negative control; Strv, starved.

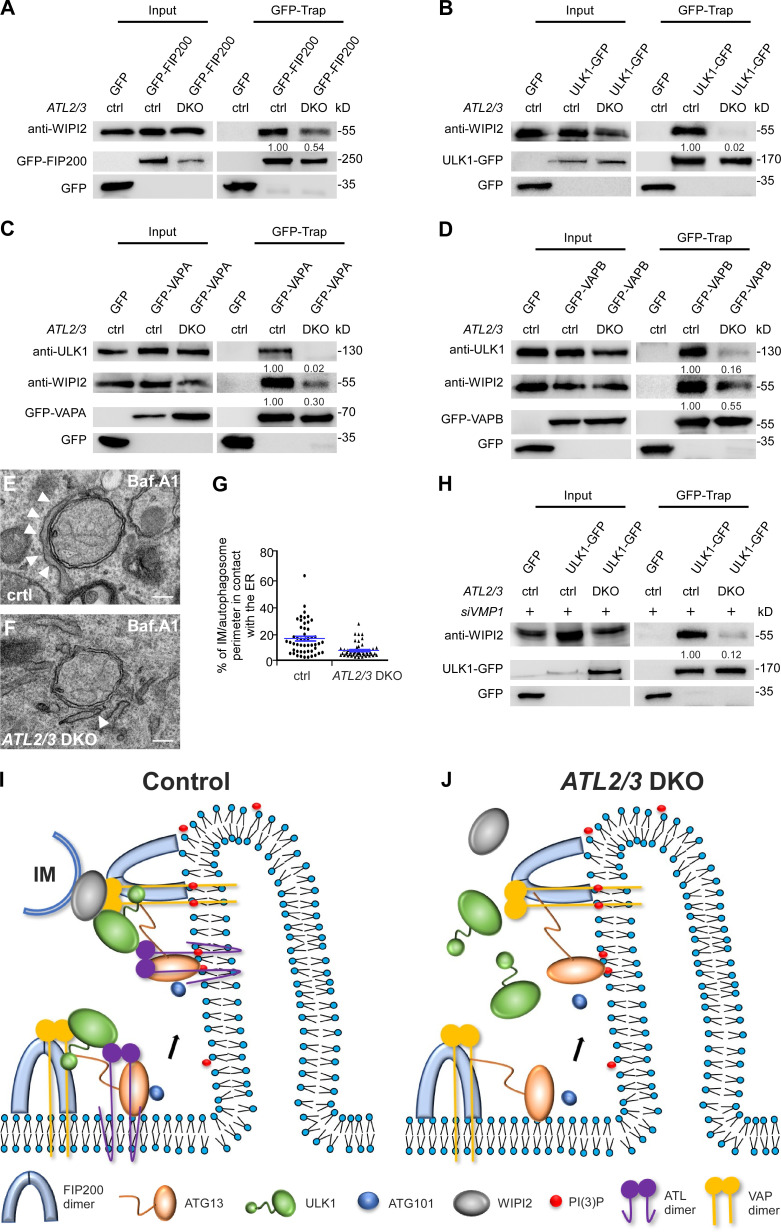

Depletion of ATL2/3 impairs the formation of the ER–IM contact

The interaction of the ULK1 complex and the IM-localized protein WIPI2 contribute to ER–IM contact formation (Zhao et al., 2017, 2018). In ATL2/3 DKO cells, levels of endogenous WIPI2 coimmunoprecipitated by GFP-FIP200 and ULK1-GFP were significantly decreased (Fig. 7, A and B). VAPs also interact with the ULK1 complex and with WIPI2, which contributes to ER–IM contact formation. The interactions of GFP-VAPB or GFP-VAPA with ULK1 and WIPI2 were decreased in ATL2/3 DKO cells (Fig. 7, C and D). We also performed EM analysis to directly visualize the ER–IM contact. Compared with control cells, the percentage of the IM/autophagosome perimeter in contact with the ER was lower in ATL2/3 DKO cells (Fig. 7, E–G). The enhanced interactions of endogenous WIPI2 with ULK1-GFP and GFP-VAPA/B in VMP1 KD cells were dramatically decreased by simultaneous depletion of ATL2/3 (Fig. 7 H; and Fig. S5, K and L). These results indicate that depletion of ATL2/3 impairs the ER–IM contact.

Figure 7.

Depletion of ATL2/3 impairs the formation of the ER–IM contact. (A and B) Compared with control cells, levels of WIPI2 precipitated by GFP-FIP200 (A) and ULK1-GFP (B) are dramatically decreased in ATL2/3 DKO COS-7 cells in GFP-Trap assays. Quantification of WIPI2 levels (normalized by GFP-FIP200 levels and ULK1-GFP levels, respectively) is also shown. (C and D) Levels of endogenous ULK1 and WIPI2 precipitated by GFP-VAPA (C) and GFP-VAPB (D) are dramatically decreased in ATL2/3 DKO COS-7 cells compared with control cells in GFP-Trap assays. Quantifications of ULK1 and WIPI2 levels (normalized by GFP-VAPA levels and GFP-VAPB levels, respectively) are also shown. (E–G) EM micrographs showing the contacts between the ER and autophagosomes in control (E) and ATL2/3 DKO (F) COS-7 cells with Baf.A1 treatment. The arrowheads indicate the ER. For individual autophagosomes, the percentage of the perimeter in contact with the ER was determined. Data are shown in G as mean ± SEM (n = 50 autophagosomes in each group). Scale bars, 200 nm. (H) Compared with VMP1 KD cells, levels of WIPI2 precipitated by ULK1-GFP are dramatically decreased in VMP1 KD cells with simultaneous depletion of ATL2/3 in GFP-Trap assays. Quantification of WIPI2 levels (normalized by ULK1-GFP levels) is also shown. (I and J) Model for the role of ATL2/3 in targeting and stabilizing the ULK1 complex on the ER. In early steps of autophagy, FIP200 and ATG13 are recruited to the autophagosome formation site. The C-shaped NTD of FIP200 is shown here. ULK1 is recruited to the FIP200 puncta with the aid of ATL2/3 and VAPA/B. VAPA/B contribute to stabilizing FIP200-ULK1, while ATL2/3 contribute to stabilizing ATG13-ULK1. ATL2/3 and VAPA/B also contribute to the establishment and/or stabilization of the ER–IM contacts (I). In ATL2/3 DKO cells, formation of FIP200 and ATG13 puncta is unaffected, while targeting of ULK1 and ATG101 is severely impaired. The ER–IM contacts are also impaired (J). ctrl, control.

The interactions of Myc-VAPA with GFP-ORP1L and GFP-VAPB with PTPIP51, which participate in the formation of the ER–endosome contact and the ER–mitochondrion contact, respectively (De Vos et al., 2012; Rocha et al., 2009), were not changed in ATL2/3 DKO cells (Fig. S5, M and N). Thus, ATL2/3 are not generally involved in the formation of ER contacts with other organelles.

Discussion

ATL2/3 modulate autophagosome formation

We demonstrate here that depletion of ATL2/3 impairs the initial step of autophagosome formation. ATL2/3 DKO cells exhibit elevation of the LC3-I level and a reduction in the LC3-II/LC3-I ratio. These are characteristic features when autophagy is inhibited by impairing the assembly of the ULK1 complex, such as through depletion of ULK1, ATG101, FIP200, or VAPs (Hosokawa et al., 2009a; Zhao et al., 2018). In terms of membrane dynamics activity, ATLs have been suggested to be involved in ER-associated processes (Hu et al., 2009; Orso et al., 2009). The impaired COPII formation and ER export in ATL-depleted cells probably results from reduced mobility of ER contents and a consequent defect in cargo packaging (Pawar et al., 2017; Behrendt et al., 2019; Niu et al., 2019). Depletion of ATL2/3 also affects the Golgi morphology and distribution (Chen et al., 2011; Namekawa et al., 2007; Stefano et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2016). The altered spatial distribution of these organelles may also account for the overall impairment of autophagic flux in ATL2/3 DKO cells. Surprisingly, two lines of evidence indicate that the reduced number of LC3 puncta in ATL2/3 DKO cells is not directly associated with the unbranched ER morphology. First, overexpression of the tubule-forming integral ER membrane protein RNT4a (Voeltz et al., 2006), which causes long and unbranched ER tubules similar to those in ATL2/3 DKO cells, has no evident effect on LC3 punctum formation after starvation. Second, in ATL2/3 DKO cells, the extent of changes in ER morphology varies from cell to cell. However, the number of LC3 puncta in ATL2/3 DKO cells with a severe unbranched ER phenotype is similar to cells with a mild unbranched ER phenotype. The ER morphology, however, may affect other aspects of the autophagy pathway. The ER forms contacts with the IM during autophagosome elongation, so the change in the ER morphology may affect the dynamics of autophagosome formation. Moreover, alteration of the ER morphology in ATL2/3-depleted cells results in perinuclear distribution of autophagosomes and lysosomes, which may affect autophagosome maturation (Zhao and Zhang, 2019). However, these defects are not necessarily reflected in the overall number of LC3 puncta.

Previous studies have shown that ATLs act in ERphagy. Several ER membrane proteins, including FAM134B, Rtn3, Sec62, CCPG1, and TEX264, have been shown to act as receptors to mediate ER turnover by directly interacting with ATG8 family members (Chino and Mizushima, 2020). ATL2 colocalizes with FAM134B and acts downstream of FAM134B in the ERphagy pathway, probably by remodeling the ER membrane to separate ER fragments for autophagic degradation (Liang et al., 2018). The function of ATL2 in ERphagy can be compensated by other ATL family members. ATL3 directly interacts with the GABARAP ATG8 subfamily, acting as a receptor for degradation of the tubular ER (Chen et al., 2019). Thus, ATLs have multiple functions in basal autophagy and selective ERphagy.

ATL modulates targeting of ULK1 and ATG101 to the FIP200-ATG13–specified autophagosome formation sites on the ER

The ULK1 complex is not a well-ordered complex, nor is it constitutively coassembled on the ER (Chan et al., 2009; Hosokawa et al., 2009b; Shi et al., 2020). Instead, the formation of the ULK1 complex is mediated by dynamic interactions among the subunits involving IDRs. For example, the C-terminal IDR of ATG13 interacts with the FIP200 NTD as well as with the ULK1 EAT domain. A recent study provided structural insights into the assembly of the ULK1 complex (Shi et al., 2020). FIP200 forms a dimeric structure mediated by its NTD and acts as a scaffold in assembling other subunits. The interaction of ATG13–ATG101 with FIP200 NTD stabilizes the C-shaped conformation of FIP200 NTD, which triggers direct interaction between ULK1 and FIP200 NTD (Shi et al., 2020). The FIP200 NTD dimer is asymmetrically organized and interacts with one copy each of ATG13, ATG101, and ULK1. These three proteins are located near one tip of the C-shaped FIP200 NTD dimer (Shi et al., 2020). Our study here indicates that depletion of the ER-localized ATL2/3 proteins has no effect on the formation of FIP200 and ATG13 puncta but impairs the targeting of ULK1 and ATG101 to the FIP200–ATG13 subcomplex on the ER. The interaction of ATG13 with ULK1 and ATG101 on the ER membrane is decreased in ATL2/3 DKO cells. ATG101 does not interact with ATL2 and ATL3. ATG101 forms fewer puncta in cells depleted of ULK1/2. Thus, KO of ATL2/3 is likely to indirectly impair ATG101 by affecting ULK1. Previous studies indicate that the HORMA domain of ATG13, which possesses an unstable fold, is stabilized by interacting with the HORMA domain of ATG101 (Suzuki et al., 2015). Our results indicate that ATLs also stabilize or facilitate the ATG13–ATG101 interaction as well as the ATG13–ULK1 interaction on the ER membrane.

The ER-localized proteins VAPA and VAPB contribute to stabilizing the ULK1–FIP200 interaction at the autophagosome formation sites. In VAPA/B-depleted cells, the number of ATG13 puncta is not evidently affected, while the formation of ULK1 puncta is significantly reduced. The interaction of ULK1 with FIP200 is reduced, while the interactions of ATG13 with FIP200 or ULK1 are not reduced in cells depleted of VAPs (Zhao et al., 2018). Thus, ATLs stabilize the interaction of ULK1 with ATG13, while VAPs recruit/stabilize ULK1 at FIP200 puncta (Fig. 7 I). In ATL2/3 DKO cells, formation of FIP200 and ATG13 puncta is unaffected, while targeting of ULK1 and ATG101 to the autophagosome formation sites as well as the formation of ER–IM contacts are severely impaired (Fig. 7 J). Consistent with the notion that ATLs and VAPs act at distinct steps of ULK1 recruitment, simultaneous depletion of ATLs and VAPs causes a synthetic loss of ULK1 puncta. ATLs and VAPs also act redundantly in stabilizing the FIP200 and ATG13 puncta on the ER. The components of the ULK1 complex are not integral ER membrane proteins, and they dynamically associate with the ER. FIP200, sustained PI(3)P synthesis, and ATLs/VAPs appear to form a positive feedback loop in regulating the ER localization of the ULK1 complex. Inhibiting PI(3)P synthesis by wortmannin treatment reduces the number and duration of ULK1 complex puncta (Karanasios et al., 2013). ATL2/3 proteins and VAPs become concentrated at the FIP200-labeled autophagosome formation sites upon autophagy induction (Zhao et al., 2018). Wortmannin treatment attenuates the recruitment of VAPs to FIP200-labeled puncta and reduces the interactions of ULK1 with ATL2/3. Turnover of PI(3)P on autophagic structures at the end stage of autophagosome formation may contribute to the disassociation of the ULK1 complex from autophagic structures.

ATLs and VAPs contribute to the formation of the ER–IM contact

During expansion of the IM into the autophagosome, the ER forms dynamic contacts with the IM. The interaction of FIP200/ULK1 and WIPI2 contributes to tethering of the ER to IMs. In WIPI2-depleted cells, IMs are separate from omegasomes and fail to proceed to autophagosomes (Polson et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2017). The lipid transfer autophagy protein ATG2, which forms a complex with WIPI3/4, also participates in ER–IM contact formation (Maeda et al., 2019; Osawa et al., 2019; Valverde et al., 2019). ATL2/3 enhances formation of the FIP200/ULK1–WIPI2 tethering complex. The involvement of ATL2/3 in ER–IM tethering is further supported by the fact that they are required for the enhanced formation of ER–IM tethering complexes, such as ULK1–WIPI2 and WIPI2–VAPs, in VMP1 KO cells. One possible function of ATL2/3 in ER–IM contacts is to stabilize the ULK1 complex on the ER. Our study provides insights into the dynamic assembly of the ULK1 autophagosome initiation complex on the ER and its subsequent function in forming ER–IM contacts during autophagosome formation.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

HEK293T and COS-7 cells (from ATCC) were cultured in DMEM (SH30022.01; HyClone) and 10% FBS (SH30084.03; HyClone) supplemented with penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2. Neither of these cell lines is listed as misidentified or cross-contaminated in the International Cell Line Authentication Committee database, and both were free of mycoplasma contamination.

For amino acid (aa) starvation, cells were washed three times with 1×PBS and then cultured in DMEM without aa (SH4007.01; HyClone) for the indicated time. For HBSS starvation, cells were washed three times with 1×PBS and then cultured in HBSS medium (14025-092; Gibco). For rapamycin (R0395; Sigma-Aldrich) or Baf.A1 (B1793; Sigma Aldrich) treatment, cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS and rapamycin (100 nM) or Baf.A1 (100 nM) for 6 h. To inhibit PI(3)P kinase, cells were treated with 2 µM wortmannin (PHZ1301; Life Technologies) for 4 h.

To produce ATL2 and ATL3 single KO cells, single gRNA–expressing plasmids were constructed using the vector px458. COS-7 cells were transfected with recombinant plasmids and then sorted by flow cytometry 24 h after transfection. The single gRNA sequences are ATL2, 5′-GACCAGCGACCCAAGCGCCGCGG-3′; and ATL3, 5′-GTTTTCACTGTGGAGAAGCCAGG-3′.

Reagents and antibodies

The following antibodies were used for immunostaining or immunoblotting assays: mouse anti-LC3 (MBL, M152-3), rabbit anti-LC3 (2775S; Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-p62 (MBL, PM045), rabbit anti-FIP200 (SAB4200135; Sigma-Aldrich), rabbit anti-FIP200 (17250-1-AP; Proteintech), rabbit anti-ULK1 (8054; Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-Atg13 (13468S; Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-ATL2 (16688-1-AP; Proteintech), rabbit anti-ATL3 (ab117819; Abcam), mouse anti-WIPI2 (ab105459; Abcam), mouse anti-VAPB (66191-1-IG; Proteintech), rabbit anti-VAPA (15275-1-AP; Proteintech), mouse anti-LAMP1 (553792; BD Biosciences), rabbit anti-PTPIP51 (20641-1-AP; Proteintech), rabbit anti-ATG101 (13492; Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-Myc (2278S; Cell Signaling Technology), mouse anti-Myc (M5546; Sigma-Aldrich), mouse anti-GFP (11814460001; Roche), mouse anti-actin (60008-1-IG; Proteintech), and rabbit anti-HA (H6908; Sigma-Aldrich).

The following reagents were used in this study: wortmannin (PHZ1301; Life Technologies), bafilomycin (B1793; Sigma-Aldrich), rapamycin (R0395; Sigma-Aldrich), Lipofectamine 2000 (12566014; Life Technologies), Lipofectamine RNAi MAX (13778150; Life Technologies), and LysoTracker Deep Red (L12492; Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Plasmids

CANX-GFP, GFP-VAPA, GFP-VAPB, 3×Myc-VAPA, GFP-ATG13, ULK1-GFP, GFP-MFN1, GFP-DFCP1, GFP-ORP1L, and RFP-LC3 were generated as previously described (Zhao et al., 2018). Human cDNAs encoding ATL2 and ATL3 were inserted into pEGFP-C1 vector. Myc-ATL2(1–373), Myc-ATL2(374–583), Myc-ATL3(1–343), Myc-ATL3(344–541), ULK1-GFP (1–277), and GFP-ATG13(1–346) were generated by truncation of corresponding constructs. Human cDNA encoding RTN4a was inserted into pCMV-Myc vector. GFP-FIP200 was kindly provided by Dr. Noboru Mizushima (University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan).

The following primers are used for plasmid construction: GFP-ATL2 (forward) 5′-CGGACTCAGATCTCGAGCTGCGGAGGGGGACGAGGCA-3′, (reverse) 5′-GCAGAATTCGAAGCTTCTAATTTTTCTTCTTGTTATTG-3′; GFP-ATL3 (forward) 5′-GGTACCGCGGGCCCGGGATCCTTGTCCCCTCAGCGAGTG-3′, (reverse) 5′-TCTAGATCCGGTGGATCC CTATTGAGCTTTTTTATCCATG-3′; Myc-ATL2(1–373) (forward) 5′-TCCAAAGTCCTGAATTCATTGATCATAATC-3′, (reverse) 5′-ATGAATTCAGGACTTTGGATGTGGAAGTTC-3′;Myc-ATL2(374–583) (forward) 5′-TCGAATTC ATGCTTCAGGCAACAGCTGAAGC-3′, (reverse) 5′-CTGAAGCATGAATTCGATATCCTGCAGG-3′; Myc-ATL3(1–343) (forward) 5′-CAAGTCCATGTAGGCCCGGGATAGGTACCTCG-3′, (reverse) 5′-CGGGCCTACATGGACTTGGGGTGAGGCAGATC-3′; Myc-ATL3(344–541) (forward) 5′-GGCTCCATGCTTCAGGCCACTGCTGAAGCCAAC-3′, (reverse) 5′-GGCCTGAAGCATGGAGCCTCCGCCTTCAAAGC-3′; ULK1-GFP (1–277) (forward) 5′-CCACCCTTTCGATCCACCGGTCGCCACCATGG-3′, (reverse) 5′-CCGGTGGATCGAAAGGGTGGTGGAAAAATTCA-3′; GFP-ATG13(1–346) (forward) 5′-CCCATTAACAATGACAAGCTTCGAATTCTG-3′, (reverse) 5′-CTTGTCATTAGTTAATGGGTTTGTTGACAAAAG-3′; and Myc-RTN4a (forward) 5′-ATGGAGGCCCGAATTCGGATGGTGAGCAAGGGC-3′, (reverse) 5′-GCCGCGGTACCTCGAGATCATTCAGCTTTGCG-3′.

Transfection and RNAi

Transfection of plasmids was performed with Lipofectamine 2000 (12566014; Life Technologies). Cells were transfected with siRNA and RNAi MAX (13778150; Life Technologies) and cultured for 72 h for siRNA interference. siRNA oligos were purchased from GenePharma and JTS Bio.

The siRNAs sequences are as follows: siRNA negative control, 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′; siRNA monkey VAPA, 5′-GGAUCAACCUCAACUGCAUTT-3′; siRNA monkey VAPB, 5′-GGAAGACAGUGCAGAGCAATT-3′; siRNA monkey VMP1, 5′-GUGAUGGUGUGUUACUUCATT-3′; siRNA monkey ULK1-1, 5′-CCUCCUUCGACUUCCCAAATT-3′; siRNA monkey ULK2-1, 5′-GCAUAGGAACAGUGAUAUATT-3′; siRNA monkey ULK2-2, 5′-CCUAGUAUUCCCAGAGAAATT-3′; and siRNA monkey ULK2-3, 5′-GCACCAAUUCCAGUACCUATT-3′.

Immunostaining assays

Cells were cultured on coverslips in cell culture plates. After harvesting, cells were washed with 1×PBS and fixed with 4% PFA for 20 min at room temperature and then permeabilized by 10 mg/ml digitonin (D141; Sigma) for 10 min. Cells were blocked by 5% goat serum for 1 h and incubated with primary antibodies (diluted by 5% goat serum) at 4°C overnight. After washing three times with 1×PBS (10 min for each), cells were incubated with fluorescently conjugated secondary antibodies (diluted by 5% goat serum) for 1 h at room temperature. After three washes with 1×PBS, coverslips were placed on microscope slides with DAPI in 50% glycerol. LysoTracker Deep Red (1:1,000, L12492; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to stain lysosomes for 30 min at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were examined with a confocal microscope (LSM 880 Meta plus Zeiss Axiovert Zoom; Zeiss) equipped with a 63×/1.40 oil immersion objective lens (Plan-Apochromat; Zeiss) and a camera (AxioCam HRm; Zeiss).

Immunoblotting assays

Cells were washed with 1×PBS, then lysed with lysis buffer (50 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (B14003; Roche) and incubated on ice for 30 min. Cell lysates were centrifuged for 10 min at 4°C at 13,000 rpm. The supernatants were subjected to SDS-PAGE and then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The protein signals were detected by using the corresponding primary antibodies and secondary antibodies. After incubation with the antibodies, the polyvinylidene difluoride membrane was exposed using an imaging system (ChemiScope 6000 Touch; ClinX). The immunoblotting results were normalized with actin protein, which was used as the loading control.

Immunoprecipitation assays

24 h after transfection of plasmids, cells were washed with 1×PBS and then lysed with lysis buffer (50 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (B14003; Roche) and incubated on ice for 30 min. Cell lysates were centrifuged for 10 min at 4°C at 13,000 rpm. The supernatant was incubated with GFP-Trap agarose beads with gentle rotation at 4°C for 1 h. After four washes with elution buffer (50 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1% Triton X-100), the beads were boiled with 2×SDS loading buffer at 100°C for 10 min. The samples are analyzed by immunoblotting assays.

ER extraction assay

Cells were collected with 1×PBS into a 1.5-ml centrifuge tube and then centrifuged for 5 min at 4°C at 500 g. The supernatant was removed and the pellet resuspended in 1 ml buffer E (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, and protease inhibitor cocktail). The cells were placed on ice for 15–20 min and then homogenized on ice and transferred to a new centrifuge tube. The homogenate was centrifuged for 5 min at 4°C at 1,000 g, and then the supernatant moved to a new tube and centrifuged for 20 min at 4°C at 8,000 g. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and centrifuged for 1 h at 4°C at 100,000 g. Finally, the supernatant was removed and retained as the soluble fraction, and the pellet was retained as the ER fraction for analysis.

Protein expression and purification

ULK1(1–277) and ATG13(1–346) were PCR amplified and then inserted into the pGEX-6P-1 vector to generate GST-ULK1(1–277) and GFP-ATG13(1–346), respectively. His-HA-ATL2(1–474) and His-HA-ATL3(1–443) were kindly provided by Dr. Junjie Hu. These proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21-CodenPlus (DE3) and purified using Sepharose 4B beads (for GST-tagged protein; GE Healthcare) and Ni-NTA agarose beads (for His6-tagged proteins; QIAGEN). After desalination with desalting columns (GE Healthcare), proteins were eluted with 1×PBS buffer.

In vitro pulldown assays

GST, GST-ULK1(1–277), and GST-ATG13(1–346) proteins were incubated with 20 µl GST beads in 500 µl pulldown buffer (1×PBS and 0.1% NP-40), and then rotated gently at 4°C for 30 min. The samples were centrifuged for 3 min at 4°C at 3,000 rpm, and the supernatant was removed. His-HA-ATL2 or His-HA-ATL3 (50 µg) was incubated in 500 µl pulldown buffer and then added to the GST beads and rotated gently at 4°C for 1 h. After four washes with pulldown buffer, the beads were boiled with 20 µl 2×SDS loading buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting analysis.

Live-cell imaging

Cells were cultured on glass bottom dishes (801001; NEST). 24 h after transfection of plasmids, cells were cultured in HBSS medium and imaged at 37°C and 5% CO2 using a 100× objective (CFI Plan Apochromat Lambda, NA 1.45; Nikon) with immersion oil on an inverted fluorescence microscope (Eclipse Ti-E; Nikon) with a spinning-disk confocal scanner unit (UltraView; PerkinElmer). Images were taken every 5 s for 1 h. The images were analyzed with Volocity software (PerkinElmer).

EM

The OTO (ferrocyanide-reduced osmium tetroxide postfixation, thiocarbohydrazide-osmium liganding) method was used to prepare the cell samples for transmission EM. Cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 2 h at room temperature (or overnight at 4°C). After postfixation in 1% OsO4 and 0.05% potassium ferrocyanide for 50 min, cells were washed with distilled water and placed in thiocarbohydrazide solution for 30 min at room temperature. The cells were then washed in distilled water again and incubated with 1% OsO4 for 45 min at room temperature. After washing with ddH2O, cells were further dehydrated with a graded series of ethanol solutions and embedded in epoxy resin. Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined using a 120-kV EM (H-7650B; Hitachi) at 100 kV, and images were captured with an AMT charge-coupled device camera (XR-41) using DigitalMicrograph software at room temperature.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Immunoblotting, in vitro pulldown, and coimmunoprecipitation results are representative of at least three independent experiments. The immunoprecipitation efficiency was normalized with the amount of the respective inputs. Cells and images for analysis were chosen randomly. GraphPad Prism and ImageJ software were used in statistical analysis, and parameters, including n, SEM, and P value, are reported in the corresponding figure legends. Statistical comparisons were made using the two-tailed unpaired t test, and the results are shown as mean ± SEM. ns, P > 0.05; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows a reduction in the number of LC3 puncta in ATL2/3 DKO cells independent of the altered ER morphology. Fig. S2 shows a delay of the autophagic flux in ATL2/3 DKO cells. Fig. S3 illustrates that ATL2/3 contribute to the recruitment of ULK1 by ATG13. Fig. S4 shows enrichment of GFP-ATL2 and 3 at the autophagosome formation sites. Fig. S5 displays the interaction of ATL2/3 with ULK1 and ATG13, the autophagy defect in ATL2/3 DKO cells with simultaneous depletion of VAPA/B, and the role of ATL2/3 in the formation of the complexes mediating the ER–IM contact.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Isabel Hanson for editing this work.

This work was supported by the following grants to H. Zhang: National Natural Science Foundation of China (92054301, 31630048, and 31790403), Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology (2017YFA0503401), Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (Z181100001318003), Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB19000000), and Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences (QYZDY-SSW-SMC006).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: J. Hu and H. Zhang designed the experiments. N. Liu, H. Zhao, and Y.G. Zhao performed the experiments. N. Liu and H. Zhang wrote the manuscript.

References

- Axe, E.L., Walker S.A., Manifava M., Chandra P., Roderick H.L., Habermann A., Griffiths G., and Ktistakis N.T.. 2008. Autophagosome formation from membrane compartments enriched in phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate and dynamically connected to the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Biol. 182:685–701. 10.1083/jcb.200803137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrendt, L., Kurth I., and Kaether C.. 2019. A disease causing ATLASTIN 3 mutation affects multiple endoplasmic reticulum-related pathways. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 76:1433–1445. 10.1007/s00018-019-03010-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, E.Y., Longatti A., McKnight N.C., and Tooze S.A.. 2009. Kinase-inactivated ULK proteins inhibit autophagy via their conserved C-terminal domains using an Atg13-independent mechanism. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29:157–171. 10.1128/MCB.01082-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J., Stefano G., Brandizzi F., and Zheng H.. 2011. Arabidopsis RHD3 mediates the generation of the tubular ER network and is required for Golgi distribution and motility in plant cells. J. Cell Sci. 124:2241–2252. 10.1242/jcs.084624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q., Xiao Y., Chai P., Zheng P., Teng J., and Chen J.. 2019. ATL3 Is a tubular ER-phagy receptor for GABARAP-mediated selective autophagy. Curr. Biol. 29:846–855.e6. 10.1016/j.cub.2019.01.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chino, H., and Mizushima N.. 2020. ER-phagy: Quality control and turnover of endoplasmic reticulum. Trends Cell Biol. 30:384–398. 10.1016/j.tcb.2020.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vos, K.J., Mórotz G.M., Stoica R., Tudor E.L., Lau K.F., Ackerley S., Warley A., Shaw C.E., and Miller C.C.. 2012. VAPB interacts with the mitochondrial protein PTPIP51 to regulate calcium homeostasis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 21:1299–1311. 10.1093/hmg/ddr559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, R., Saheki Y., Swarup S., Lucast L., Harper J.W., and De Camilli P.. 2016. Endosome-ER contacts control actin nucleation and retromer function through VAP-dependent regulation of PI4P. Cell. 166:408–423. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y., He D., Yao Z., and Klionsky D.J.. 2014. The machinery of macroautophagy. Cell Res. 24:24–41. 10.1038/cr.2013.168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara, T., Takamura A., Kishi C., Iemura S., Natsume T., Guan J.L., and Mizushima N.. 2008. FIP200, a ULK-interacting protein, is required for autophagosome formation in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 181:497–510. 10.1083/jcb.200712064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi-Nishino, M., Fujita N., Noda T., Yamaguchi A., Yoshimori T., and Yamamoto A.. 2009. A subdomain of the endoplasmic reticulum forms a cradle for autophagosome formation. Nat. Cell Biol. 11:1433–1437. 10.1038/ncb1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa, N., Sasaki T., Iemura S., Natsume T., Hara T., and Mizushima N.. 2009a. Atg101, a novel mammalian autophagy protein interacting with Atg13. Autophagy. 5:973–979. 10.4161/auto.5.7.9296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa, N., Hara T., Kaizuka T., Kishi C., Takamura A., Miura Y., Iemura S., Natsume T., Takehana K., Yamada N., et al. 2009b. Nutrient-dependent mTORC1 association with the ULK1-Atg13-FIP200 complex required for autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell. 20:1981–1991. 10.1091/mbc.e08-12-1248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J., Shibata Y., Zhu P.P., Voss C., Rismanchi N., Prinz W.A., Rapoport T.A., and Blackstone C.. 2009. A class of dynamin-like GTPases involved in the generation of the tubular ER network. Cell. 138:549–561. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itakura, E., and Mizushima N.. 2010. Characterization of autophagosome formation site by a hierarchical analysis of mammalian Atg proteins. Autophagy. 6:764–776. 10.4161/auto.6.6.12709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karanasios, E., Stapleton E., Manifava M., Kaizuka T., Mizushima N., Walker S.A., and Ktistakis N.T.. 2013. Dynamic association of the ULK1 complex with omegasomes during autophagy induction. J. Cell Sci. 126:5224–5238. 10.1242/jcs.132415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karanasios, E., Walker S.A., Okkenhaug H., Manifava M., Hummel E., Zimmermann H., Ahmed Q., Domart M.C., Collinson L., and Ktistakis N.T.. 2016. Autophagy initiation by ULK complex assembly on ER tubulovesicular regions marked by ATG9 vesicles. Nat. Commun. 7:12420. 10.1038/ncomms12420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, S., Noda T., and Yoshimori T.. 2007. Dissection of the autophagosome maturation process by a novel reporter protein, tandem fluorescent-tagged LC3. Autophagy. 3:452–460. 10.4161/auto.4451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky, D.J., Abdelmohsen K., Abe A., Abedin M.J., Abeliovich H., Acevedo Arozena A., Adachi H., Adams C.M., Adams P.D., Adeli K., et al. 2016. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (3rd edition). Autophagy . 12:1–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ktistakis, N.T., and Tooze S.A.. 2016. Digesting the expanding mechanisms of autophagy. Trends Cell Biol. 26:624–635. 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, C.A., Yoshimori T., and Tooze S.A.. 2013. The autophagosome: Origins unknown, biogenesis complex. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 14:759–774. 10.1038/nrm3696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.R., Lingeman E., Ahmed S., and Corn J.E.. 2018. Atlastins remodel the endoplasmic reticulum for selective autophagy. J. Cell Biol. 217:3354–3367. 10.1083/jcb.201804185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, M.G., and Hurley J.H.. 2016. Structure and function of the ULK1 complex in autophagy. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 39:61–68. 10.1016/j.ceb.2016.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lü, L., Niu L., and Hu J.. 2020. “At last in” the physiological roles of the tubular ER network. Biophys. Rep. 6:105–114. 10.1007/s41048-020-00113-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, S., Otomo C., and Otomo T.. 2019. The autophagic membrane tether ATG2A transfers lipids between membranes. eLife. 8:e45777. 10.7554/eLife.45777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima, N. 2010. The role of the Atg1/ULK1 complex in autophagy regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22:132–139. 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima, N. 2018. A brief history of autophagy from cell biology to physiology and disease. Nat. Cell Biol. 20:521–527. 10.1038/s41556-018-0092-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima, N., Yoshimori T., and Ohsumi Y.. 2011. The role of Atg proteins in autophagosome formation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 27:107–132. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatogawa, H., Suzuki K., Kamada Y., and Ohsumi Y.. 2009. Dynamics and diversity in autophagy mechanisms: lessons from yeast. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10:458–467. 10.1038/nrm2708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namekawa, M., Muriel M.P., Janer A., Latouche M., Dauphin A., Debeir T., Martin E., Duyckaerts C., Prigent A., Depienne C., et al. 2007. Mutations in the SPG3A gene encoding the GTPase atlastin interfere with vesicle trafficking in the ER/Golgi interface and Golgi morphogenesis. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 35:1–13. 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura, T., Tamura N., Kono N., Shimanaka Y., Arai H., Yamamoto H., and Mizushima N.. 2017. Autophagosome formation is initiated at phosphatidylinositol synthase-enriched ER subdomains. EMBO J. 36:1719–1735. 10.15252/embj.201695189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu, L., Ma T., Yang F., Yan B., Tang X., Yin H., Wu Q., Huang Y., Yao Z.P., Wang J., et al. 2019. Atlastin-mediated membrane tethering is critical for cargo mobility and exit from the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 116:14029–14038. 10.1073/pnas.1908409116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orso, G., Pendin D., Liu S., Tosetto J., Moss T.J., Faust J.E., Micaroni M., Egorova A., Martinuzzi A., McNew J.A., and Daga A.. 2009. Homotypic fusion of ER membranes requires the dynamin-like GTPase atlastin. Nature. 460:978–983. 10.1038/nature08280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osawa, T., Kotani T., Kawaoka T., Hirata E., Suzuki K., Nakatogawa H., Ohsumi Y., and Noda N.N.. 2019. Atg2 mediates direct lipid transfer between membranes for autophagosome formation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 26:281–288. 10.1038/s41594-019-0203-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.H., Zhu P.P., Parker R.L., and Blackstone C.. 2010. Hereditary spastic paraplegia proteins REEP1, spastin, and atlastin-1 coordinate microtubule interactions with the tubular ER network. J. Clin. Invest. 120:1097–1110. 10.1172/JCI40979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawar, S., Ungricht R., Tiefenboeck P., Leroux J.C., and Kutay U.. 2017. Efficient protein targeting to the inner nuclear membrane requires Atlastin-dependent maintenance of ER topology. eLife. 6:e28202. 10.7554/eLife.28202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peretti, D., Dahan N., Shimoni E., Hirschberg K., and Lev S.. 2008. Coordinated lipid transfer between the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi complex requires the VAP proteins and is essential for Golgi-mediated transport. Mol. Biol. Cell. 19:3871–3884. 10.1091/mbc.e08-05-0498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, M.J., and Voeltz G.K.. 2016. Structure and function of ER membrane contact sites with other organelles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17:69–82. 10.1038/nrm.2015.8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polson, H.E., de Lartigue J., Rigden D.J., Reedijk M., Urbé S., Clague M.J., and Tooze S.A.. 2010. Mammalian Atg18 (WIPI2) localizes to omegasome-anchored phagophores and positively regulates LC3 lipidation. Autophagy. 6:506–522. 10.4161/auto.6.4.11863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz, W.A. 2014. Bridging the gap: Membrane contact sites in signaling, metabolism, and organelle dynamics. J. Cell Biol. 205:759–769. 10.1083/jcb.201401126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi, S., Kim D.J., Stjepanovic G., and Hurley J.H.. 2015. Structure of the human Atg13-Atg101 HORMA heterodimer: An interaction hub within the ULK1 complex. Structure. 23:1848–1857. 10.1016/j.str.2015.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiborg, C., Wenzel E.M., and Stenmark H.. 2015. ER-endosome contact sites: Molecular compositions and functions. EMBO J. 34:1848–1858. 10.15252/embj.201591481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha, N., Kuijl C., van der Kant R., Janssen L., Houben D., Janssen H., Zwart W., and Neefjes J.. 2009. Cholesterol sensor ORP1L contacts the ER protein VAP to control Rab7-RILP-p150 glued and late endosome positioning. J. Cell Biol. 185:1209–1225. 10.1083/jcb.200811005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X., Yokom A.L., Wang C., Young L.N., Youle R.J., and Hurley J.H.. 2020. ULK complex organization in autophagy by a C-shaped FIP200 N-terminal domain dimer. J. Cell Biol. 219:e201911047. 10.1083/jcb.201911047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata, Y., Voeltz G.K., and Rapoport T.A.. 2006. Rough sheets and smooth tubules. Cell. 126:435–439. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefano, G., Renna L., Moss T., McNew J.A., and Brandizzi F.. 2012. In Arabidopsis, the spatial and dynamic organization of the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus is influenced by the integrity of the C-terminal domain of RHD3, a non-essential GTPase. Plant J. 69:957–966. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04846.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, H., Kaizuka T., Mizushima N., and Noda N.N.. 2015. Structure of the Atg101-Atg13 complex reveals essential roles of Atg101 in autophagy initiation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 22:572–580. 10.1038/nsmb.3036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde, D.P., Yu S., Boggavarapu V., Kumar N., Lees J.A., Walz T., Reinisch K.M., and Melia T.J.. 2019. ATG2 transports lipids to promote autophagosome biogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 218:1787–1798. 10.1083/jcb.201811139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voeltz, G.K., Prinz W.A., Shibata Y., Rist J.M., and Rapoport T.A.. 2006. A class of membrane proteins shaping the tubular endoplasmic reticulum. Cell. 124:573–586. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallot-Hieke, N., Verma N., Schlütermann D., Berleth N., Deitersen J., Böhler P., Stuhldreier F., Wu W., Seggewiß S., Peter C., et al. 2018. Systematic analysis of ATG13 domain requirements for autophagy induction. Autophagy. 14:743–763. 10.1080/15548627.2017.1387342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N., and Rapoport T.A.. 2019. Reconstituting the reticular ER network - mechanistic implications and open questions. J. Cell Sci. 132:jcs227611. 10.1242/jcs.227611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S., Romano F.B., Field C.M., Mitchison T.J., and Rapoport T.A.. 2013. Multiple mechanisms determine ER network morphology during the cell cycle in Xenopus egg extracts. J. Cell Biol. 203:801–814. 10.1083/jcb.201308001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ylä-Anttila, P., Vihinen H., Jokitalo E., and Eskelinen E.L.. 2009. 3D tomography reveals connections between the phagophore and endoplasmic reticulum. Autophagy. 5:1180–1185. 10.4161/auto.5.8.10274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H. 2020. Lipid transfer at ER-isolation membrane contacts. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21:121. 10.1038/s41580-020-0212-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]