Abstract

Background

Hearing loss is a common and costly medical condition. This systematic review sought to identify evidence gaps in published model-based economic analyses addressing hearing loss to inform model development for an ongoing Lancet Commission.

Methods

We searched the published literature through 14 June 2020 and our inclusion criteria included decision model-based cost-effectiveness analyses that addressed diagnosis, treatment, or prevention of hearing loss. Two investigators screened articles for inclusion at the title, abstract, and full-text levels. Data were abstracted and the studies were assessed for the qualities of model structure, data assumptions, and reporting using a previously published quality scale.

Findings

Of 1437 articles identified by our search, 117 unique studies met the inclusion criteria. Most of these model-based analyses were set in high-income countries (n = 96, 82%). The evaluated interventions were hearing screening (n = 35, 30%), cochlear implantation (n = 34, 29%), hearing aid use (n = 28, 24%), vaccination (n = 22, 19%), and other interventions (n = 29, 25%); some studies included multiple interventions. Eighty-six studies reported the main outcome in quality-adjusted or disability-adjusted life-years, 24 of which derived their own utility values. The majority of the studies used decision tree (n = 72, 62%) or Markov (n = 41, 35%) models. Forty-one studies (35%) incorporated indirect economic effects. The median quality rating was 92/100 (IQR:72–100).

Interpretation

The review identified a large body of literature exploring the economic efficiency of hearing healthcare interventions. However, gaps in evidence remain in evaluation of hearing healthcare in low- and middle-income countries, as well as in investigating interventions across the lifespan. Additionally, considerable uncertainty remains around productivity benefits of hearing healthcare interventions as well as utility values for hearing-assisted health states. Future economic evaluations could address these limitations.

Funding

NCATS 3UL1-TR002553-03S3

Keywords: Hearing loss, Cost-effectiveness, Decision modeling, Systematic review

Research in Context.

Evidence before this study

This study was motivated by the Lancet Commission on Hearing Loss, an international stakeholder group of hearing healthcare clinicians, researchers, and patients convened by The Lancet. To the Commission's knowledge, a prior systematic review of model-based economic analyses across the lifespan and across interventions in hearing healthcare does not exist. We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and Global Index Medicus for this systematic review. The search was performed on 14 June 2020. Inclusion criteria during screening were cost-effectiveness analyses of hearing healthcare interventions that used a decision model. Search terms were related to hearing loss, cost-effectiveness, and full text articles.

Added value of this study

This study comprehensively identified and evaluated decision model-based cost-effectiveness analyses in hearing healthcare. Several evidence gaps were uncovered, including limited studies set in LMIC, lack of comparison across hearing healthcare interventions and the lifespan, and input parameter uncertainty for hearing loss utility values and indirect economic effects.

Implications of all the available evidence

The findings of this study have direct implications for health and finance ministers, hearing healthcare clinicians, and ongoing model-building efforts of the Lancet Commission on Hearing Loss. The compilation of analyses and quality scores can aid health policymakers and clinicians in identifying high-quality evidence relevant to their population to guide decision making. Future research and decision models in hearing healthcare should address the evidence gaps uncovered by this systematic review.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

1. Introduction

Hearing loss is the fourth leading cause of years lived with disability worldwide, affecting nearly one in five people [1,2]. Severity of hearing loss can range from mildly affecting communication to profoundly affecting all aspects of daily life [3,4]. Furthermore, the estimated global yearly economic costs of unaddressed hearing loss for the health sector alone exceed $100 billion [5]. Inclusion of lost productivity increases that cost to $750–790 billion annually [5]. Appropriately, policymakers are focusing attention on cost-effective interventions in hearing healthcare to reduce this burden of disease [6,7].

In 2019 a Lancet Commission was convened “to examine how to reduce the global burden of hearing loss,” including investigating the economic efficiency of alternative treatment and prevention opportunities in hearing healthcare [6]. The Commission identified cost-effectiveness analysis as one element that could guide policymakers in the careful allocation of scarce resources to prevent and treat hearing loss. Decision models have long informed cost-effectiveness analyses and have provided significant insight in the field of hearing healthcare [8,9]. However, a systematic assessment of the decision modeling methodologies and qualities that inform these analyses across hearing loss interventions has yet to be performed. Understanding the state of current evidence, as well as the limitations therein, is important for the development of decision models addressing hearing healthcare.

This systematic review seeks to: (1) investigate the methods and quality of model-based cost-effectiveness analyses addressing hearing loss; (2) identify evidence gaps; and (3) inform economic modeling for the Commission.

2. Methods

The methods for this systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (see Appendix 1) [10]. To define the research questions for this review, we collaborated with the Lancet Commission on Hearing Loss [6]. Our research questions were: 1) what are the methods and quality of published model-based cost-effectiveness analyses that address hearing loss?, and 2) what are the evidence gaps in these methods or qualities? This occurred in person in November 2019, through a multi-national, multi-stakeholder meeting and subsequently in virtual conferences for the full Commission or groups within it. After the initial creation of our research question, our research objectives and preliminary results were presented to the full Commission in July 2020 for discussion and refinement of the policy implications. The Commissioners affiliate with over 14 distinct countries and include perspectives from clinicians, health policy experts, health economists, epidemiologists, patients, and others. Please see Appendix 2 for a complete listing of the Commissioners and their affiliations. This study was not registered with PROSPERO.

2.1. Data sources and study selection

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and Global Index Medicus for relevant literature. Search terms were related to hearing loss and cost-effectiveness, and filtered to include full text articles (Appendix 3). The searches were performed on 14 June 2020.

Prespecified inclusion criteria were 1) English-language, 2) original research cost-effectiveness analyses that consider both outcomes and costs, 3) studies that assessed hearing healthcare interventions (preventative, diagnostic, and therapeutic), and 4) studies that included a decision model. We only considered model-based cost-effectiveness analyses because a primary goal of this study is to inform future decision model frameworks of hearing healthcare interventions. However, we did include cost-effectiveness analyses based on clinical trials that utilized a decision model to project the cost-effectiveness of their intervention. We excluded conference abstracts and other types of cost analyses. Please see Appendix 4 for a population, intervention, comparison, outcome, time, and study design (PICOTS) table of the inclusion criteria. Before initiation of our search, we determined that we would review the bibliography of included systematic reviews and meta-analyses identified by the search strategy for relevant articles not included in the search strategy to incorporate into our screening process.

Articles were screened independently for inclusion at the abstract and full text level by two reviewers. Exclusion criteria at the abstract level were articles unrelated to hearing loss or articles that were not cost-effectiveness analyses. Exclusion criteria at the full text level comprised of those at the abstract level as well as articles that did not use a decision model. All inclusion/exclusion conflicts were resolved by discussion between the original reviewers or by discussion with a third investigator. Every effort was made to obtain full text versions of articles not available through Duke University Library. However, there was one citation for which we were unable to access a full text version and thus that article was excluded from further analyses.

2.2. Data and extraction

Data were abstracted from articles included at the full text level. All abstractions were vetted by a second investigator, with disagreements settled by a third investigator. We used the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS), a checklist detailing essential components of a health economic evaluation (see Appendix 5), and simulation modeling best-practice frameworks to guide our data abstraction [11,12]. We abstracted data related to analysis setting and population, interventions simulated, model type, clinical input parameters, and main cost-effectiveness findings that were included the Abstract (Appendix 6). Decision model types abstracted included decision tree diagrams, Markov models (that include a time component to the analysis), and other model types (e.g., diagram, probabilistic, or net-cost). The risk of bias within the modeling studies was determined using components from the CHEERS checklist. Specific components of the checklist which corresponded to potential risk of biased included statement of perspective of analysis, model validation, methods of characterizing of uncertainty, funding source, and disclosure of potential conflicts. After the initial data abstraction, we collected additional data points for studies examining the three interventions most common across all included studies and reported each study separately. We reported acoustic (i.e. traditional) hearing aids and bone-conduction devices in the same table because of their comparison to cochlear implantation and similar data abstraction structure. Studies exploring all other interventions are reported in aggregate and without additional data collection.

2.3. Quality assessment

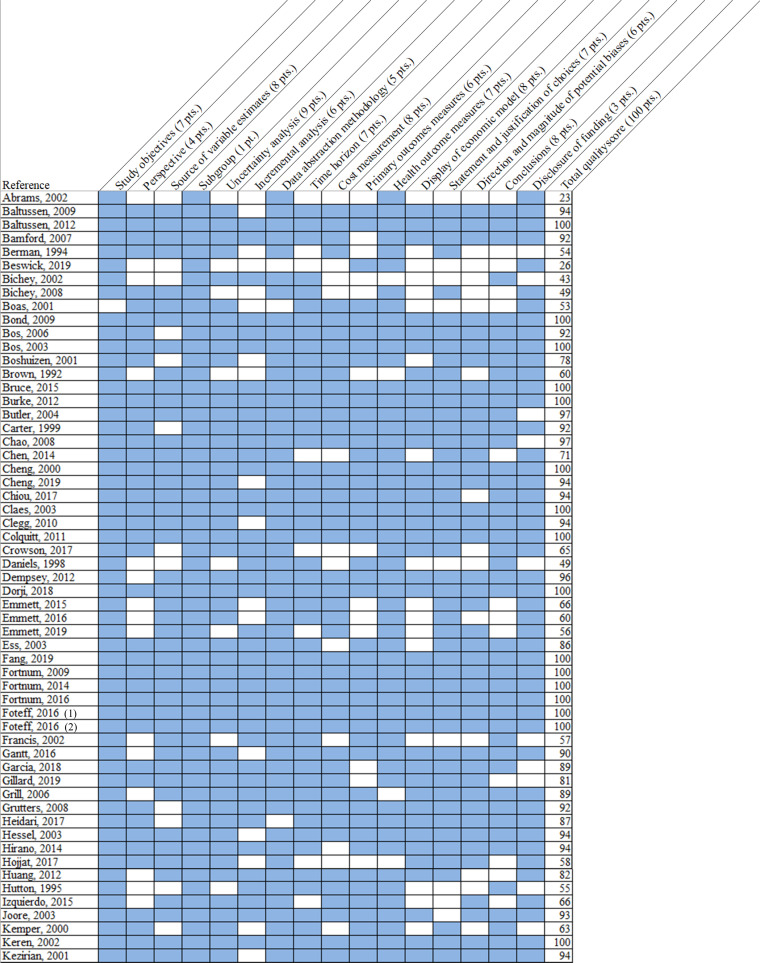

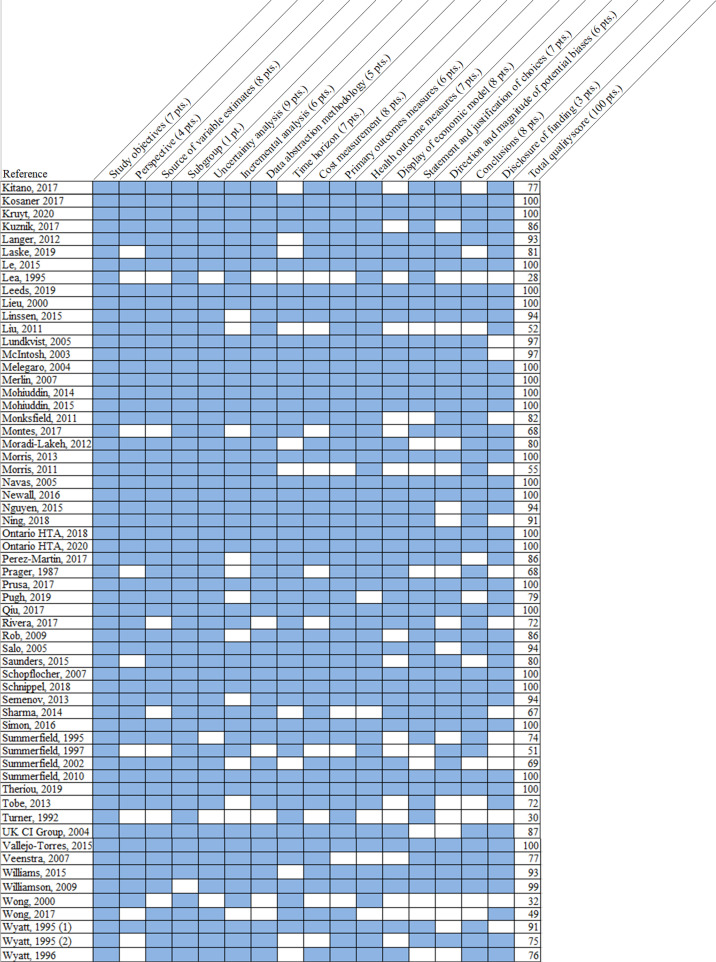

One investigator read each identified paper and abstracted quality indicators. A second investigator then independently read the included paper and noted any disagreements. Disagreements not resolved by consensus were settled by a third investigator's review. We used a previously developed quality measure that examined 16 components of the decision model and cost-effectiveness analysis and yielded a score from 0 to 100, with 100 representing a full quality score [13,14]. The components assessed for quality were related to transparency of modeling and data abstraction methods, clarity and appropriateness of mode structure and input data, and correct comparison of assessed interventions (see Appendix 7 for a complete description of the quality measure). This measure was selected because it was developed specifically for quality ratings of decision models and incorporated differential weighting (one point to eight points) for each aspect of quality [11,13]. This measure does not assign qualitative indicators to numerical scores, so we report individual article quality scores. Major methodologic or reporting deficits were defined as those components receiving a weight of six or more points on the quality rating measure (see Appendix 7, Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Quality of Included Studies.

Fig. 2 illustrates the quality score components assigned to individual studies (listed in each row). Score components are in each column, and the number of points (pts.) assigned for that component is noted in first row. Blue shading indicates that full score was given to the indicated component, while white shading indicates a score of zero for that component. Total quality score, aggregated across the weighted components, are listed in the right-most column. Please refer to Appendix 7 for complete definitions of each quality score component.

2.4. Presentation of cost parameters

All abstracted cost parameters were converted to 2019 USD. Cost parameters were first adjusted to 2019 local currency units using local consumer price indices, then converted to USD using the World Bank currency conversion rates [15]. When articles did not list the currency source year (n = 22), we assigned the year of publication for the adjustments.

2.5. Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. All authors had full access to all the data in the study, had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication prior to submission, and take full responsibility for the content of the article.

3. Results

3.1. Summary of included studies

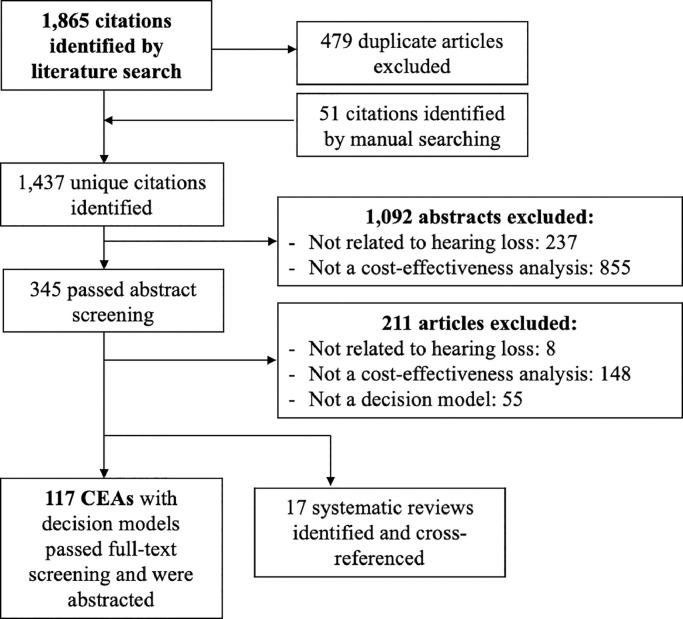

Our search yielded 1437 unique articles, of which 117 unique studies with decision models (Table 1, Batch 1) and 17 systematic reviews[132], [133], [134], [135], [136], [137], [138], [139], [140], [141], [142], [143], [144], [145], [146], [147], [148] met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Model-based studies were predominately set in high-income countries (n = 96, 82%; Table 1, Batch 2), with fewer studies in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC; n = 22, 19%; Table 1, Batch 3; Table 2). One study was set in both a high- and low- and middle-income setting [47]. Sixty-one studies evaluated hearing loss strategies exclusively in pediatric populations (<18 years, 52%; Table 1 Batch 4), 32 in adults (27%; Table 1, Batch 5), and 24 in both (21%; Table 1, Batch 6). The interventions assessed included hearing screening (n = 35, 30%; Table 1 Batch 7), cochlear implantation (n = 34, 29%; Table 1, Batch 8), hearing aid use (n = 28, 24%; Table 1, Batch 9), vaccination (n = 22, 19%; Table 1, Batch 10), and other aspects of hearing healthcare (n = 29, 25%; Table 1, Batch 11); some studies included more than one intervention (see Appendix 8 for a diagram of comparisons made among included studies). The most common decision model types were tree diagrams (n = 72, 62%; Table 1, Batch 12) and Markov models (n = 41, 35%; Table 1, Batch 13). In studies published since 2010, decision trees remained the most commonly used decision model (58%) and the proportion of Markov models used increased slightly to 42%. Sixty-one studies (52%; Table 1, Batch 14) were conducted from a healthcare payer perspective and 46 (39%; Table 1, Batch 15) from a societal or modified societal perspective (inclusive of costs and benefits relevant to society in general, such as productivity benefits or family and caregiver effects). Main cost-effectiveness findings from each included study are reported in Appendix 9 and a summary of funding sources for included studies are in Appendix 10.

Table 1.

Batched citations.

Fig. 1.

Literature Flow Diagram.

Fig. 1 diagrams the flow of studies from search identification to eventual inclusion or exclusion. CEA: cost-effectiveness analysis, PRISMA: preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analyses.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Characteristic | Number of Studies (n = 117 in all)* |

|---|---|

| Setting | |

| Africa | 6 (5%) |

| Asia | 18 (15%) |

| Australia and New Zealand | 10 (9%) |

| Europe | 47 (40%) |

| North America | 35 (30%) |

| South America | 2 (2%) |

| Population | |

| Pediatric only, <18 years | 61 (52%) |

| Adult only, >18 years | 32 (27%) |

| Mixed | 24 (21%) |

| Hearing loss intervention assessed | |

| Hearing screening | 35 (30%) |

| Cochlear implantation | 34 (29%) |

| Hearing aid use | 28 (24%) |

| Vaccination | 22 (19%) |

| Other | 29 (25%) |

| Decision model type | |

| Tree diagram | 72 (62%) |

| Markov state transition | 41 (35%) |

| Other | 8 (7%) |

| Perspective | |

| Healthcare payer | 61 (52%) |

| Societal and modified societal | 46 (39%) |

*Not all categories sum to 117 (or 100%) as some studies may be represented more than once.

3.2. Studies evaluating screening

Thirty-five of the selected studies examined hearing screening strategies, with 24 studies considering neonatal screening (Table 1, Batch 16), seven studies considering child screening (Table 1, Batch 17), and eight studies considering adult hearing screening (Table 3; Table 1 Batch 18). The most commonly evaluated screening strategy in newborn studies was universal newborn screening (n = 13; Table 1, Batch 19), followed by targeted or risk-based newborn screening (n = 8; Table 1, Batch 20). School screening was evaluated in four of the seven child screening analyses (Table 1, Batch 21). The eight studies that included adult screening analyses varied in the age at first screen, the frequency of screening, and the screening test modality. Eighteen of the 24 cost-effectiveness analyses of neonatal hearing screening (Table 1, Batch 22), one child screening analysis, [45] and two adult screening analyses [94,102] projected a main clinical outcome other than quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) or disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), often choosing an intermediate outcome such as number of cases identified. Forty percent of included screening studies across the lifespan evaluated across a time horizon of less than 10 years (Table 1, Batch 23).

Table 3.

Included studies evaluating hearing screening.

| Reference | Model Type | Setting, Population, HL Type | Screening Strategies | Screening tests included | Time Horizon, Perspective | Main Outcome | Main Cost-Effectiveness Findings* | Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neonatal Screening | ||||||||

| Beswick et al. 2019 | Decision Tree | Australia/NZ, Children, Unclear | A. Newborn CMV screening | A. Salivary CMV PCR | 18 years, Modified Societal | Infants detected | HA treatment cost $60.00/QALY gained compared to no treatment, while HA + audiologic rehabilitation cost only $31.91/QALY gained compared to no treatment. | 26 |

| Chiou et al. 2017 | Markov | Asia, Children with SNHL | A. No screening B. Universal screening |

A. TEOAE B. AABR |

Lifetime, Societal | QALY | At willingness to pay of $20,000, aABR had a 90% probability of being cost-effective against TEOAE. | 94 |

| Heidari et al. 2017 | Decision Tree | Middle East, Children, SNHL and CHL | A. Universal screening | A. AABR B. OAE C. Clinical ABR |

1 year, Payer | Infants diagnosed | Over 1 year, the AABR device cost $103,400 less than the OAE device, and detected 800 more cases than the OAE device. | 87 |

| Prusa et al. 2017 | Decision Tree | UK/Europe, Children, Unclear | A. No screening B. Bimonthly toxoplasmosis screening |

A. Toxoplasma antibody or PCR tests B. Amniocentesis + PCR |

Lifetime, Societal | NA | The model calculated total lifetime costs of €103 per birth under prenatal screening as carried out in Austria, saving €323 per birth compared with No-Screening. Without screening and treatment, lifetime societal costs for all affected children would have been €35 million per year. | 100 |

| Rivera et al. 2017 | Markov | Asia, Children, Unclear | A. No screening B. Universal Screening |

A. OAE B. ABR |

Lifetime, Payer and Societal | DALY | Community-based universal newborn hearing screening was found to be cost saving. | 72 |

| Wong et al. 2017 | Decision Tree | South America, Children with b/l SNHL | A. Universal screening B. Screening at the regional health center (RHC) C. Targeted screening D. Screening at the RHC plus targeted screening |

A. OAE | 10 years, Health System | DALY | OAE screening was cost-effective without treatment (CER/GDP=0.06–2.00) and with treatment (CER/GDP-0.58–2.52). | 49 |

| Gantt et al. 2016 | Decision Tree | United States, Children with SNHL | A. No screening B. Targeted cCMV screening C. Universal cCMV screening |

NA | Lifetime, Payer | CMV-related hearing loss identified, CI prevented | The cost of identifying 1 case of hearing loss due to cCMV ranged from $27,460 - $90,038 for universal screening, and $975 - $3916 for targeted screening. | 90 |

| Vallejo-Torres et al. 2015 | Decision Tree | UK/Europe, Children, Unclear | A. No screening B. Biotinidase deficiency screening |

NA | Lifetime, Payer | QALY | Newborn biotinidase deficiency screening was CE at $24,677/QALY in Spain. | 100 |

| Williams et al. 2015 | Decision Tree | UK/Europe, Children with SNHL | A. No screening B. Targeted cCMV screening |

cCMB salivary antigen test | NR, Health System | Case identified, CMV-related SNHL improved | The cost per case of cCMV-related SNHL identified was £668. The cost per case of cCMV-related SNHL improved was £14,202. | 93 |

| Tobe et al. 2013 | Decision Tree | Asia, Children with SNHL | A. No screening B. Targeted screening C. Universal screening |

A. OAE B. AABR |

Lifetime, Modified Societal | DALY | OAE was the most cost-effective strategy at an average cost-effectiveness ratio of I$13,100 (95% CI: 8400–17,200) per DALY averted. | 72 |

| Burke et al. 2012 | Decision Tree | Asia, UK/Europe Children with SNHL | A. Targeted (high-risk) screening B. Universal screening C. One-stage screen D. Two-stage screen |

A. TEOAE B. AABR |

Lifetime, Health System and Societal | Case detected | Universal screening vs. selective screening had an ICER per case detected of £36,181 ($58,497), and INR 157,084 ($9863) for the UK and India, respectively. One-stage vs. two-stage universal screening had an ICER per case detected of £120,972 ($195,586), and INR 926,675 ($58,183) for the UK and India, respectively. | 100 |

| Huang et al. 2012 | Decision Tree | Asia, Children with SNHL | A. Targeted screening B. Universal screening |

NA | Lifetime, Modified Societal | DALY | Targeted strategy tended to be cost-effective in Guangxi, Jiangxi, Henan, Guangdong, Zhejiang, Hebei, Shandong, and Beijing from the level of 9%, 9%, 8%, 4%, 3%, 7%, 5%, and 2%, respectively; while universal strategy trended to be cost-effective in those provinces from the level of 70%, 70%, 48%, 10%, 8%, 28%, 15%, 4%, respectively. | 82 |

| Langer et al. 2012 | Decision Tree | UK/Europe, Children with SNHL | A. Newborn screening alone B. Newborn screening + tracking program |

A. TEOAE B. AABR C. OAE |

Unclear, Payer | Case detected | The ICER of tracking vs. no tracking was €1697 per additional case of bilateral hearing impairment detected. | 93 |

| Schopflocher et al. 2007 | Decision Tree | Canada, Children with SNHL and CHL | A. One-stage screening B. Two-stage screening |

A. AOAE B. AABR |

Other, Societal | Proportion of newborns whose hearing status is correctly identified | 1-stage AABR was more cost-effective than 1-stage AOAE. 2-stage (AOAE followed by AABR) cost $7574.78 additional to correctly identify one additional infant. | 100 |

| Merlin et al. 2007 | Decision Tree | Australia/NZ, Children, Unclear | A. No screening B. Targeted screening C. Universal screening D. One-stage screening E. Two-stage screening |

A. OAE B. AABR |

Immediate, Societal | Infant identified | In the short term, the decision analytic model presented in this report predicted that implementing a two-stage AABR universal neonatal hearing screening (UNHS) program for a cohort of 250,000 newborns would identify an extra 607 infants with unilateral or bilateral hearing impairment by the age of 6 months compared to no formal screening program, at an incremental cost of $6–$11 million. Where a targeted screening program is already in place, expanding to a universal screening program would identify 319 more infants, at an incremental cost of $4–$8 million. | 100 |

| Grill et al. 2006 | Markov | UK/Europe, Children with SNHL | A. Community-based screening B. Hospital-based screening |

NA | 120 months, Health System | Quality weighted detected child months | Both hospital and community programs yielded 794 quality weighted detected child months (QCM) at the age of 6 months with total costs of £3690,000 per 100,000 screened children in the hospital and £3340,000 in the community. | 89 |

| Hessel et al. 2003 | Markov | UK/Europe, Children with SNHL | A. No screening B. Risk screening C. Universal Screening |

A. Two-step TEOAE | 10 years, Health System | Case detected | Cost per case detected: Universal screening = €13,395 Risk screening = €6715 No screening = €4125 |

94 |

| Keren et al. 2002 | Decision Tree | UK/Europe, Children with SNHL | A. No screening B. Selective screening C. Universal screening |

A. TEOAE followed by AABR | Lifetime, Societal | Cost per infant diagnosed by 6 months, cost per deaf child with normal language | The ICER for selective screening vs. no screening was $16,400 per additional infant whose deafness was diagnosed by 6 months of age. The ICER for universal screening vs. selective screening was $44,000 per additional infant whose deafness was diagnosed by 6 months of age. | 100 |

| Boshuizen et al. 2001 | Decision Tree | UK/Europe, Children with Mixed Hearing Loss | A. Home screening B. Child health clinic screening C. Unilateral screening D. Bilateral screening E. Two-stage screening F. Three-stage screening |

A. AABR B. OAE |

NR, Payer | Child detected | Costs of a three-stage screening process in child health clinics were €39.0 (95% confidence interval 20.0 to 57.0) per child detected with automated auditory brainstem response compared with €25.0 (14.4 to 35.6) per child detected with otoacoustic emissions. |

78 |

| Kezirian et al. 2001 | Decision Tree | United States, Children with SNHL | A. One-stage screening B. Two-stage screening |

A. Short-ABR B. OAE |

NR, Provider | Infant identified | Cost per infant with HL identified: 1- S-ABR/S-ABR = $8112 2- S-ABR/None = $9470 3- OAE/OAE= $5113 4- OAE then S-ABR/None= $7996. |

94 |

| Kemper and Downs 2000 | Decision Tree | United States, Children with b/l SNHL | A. Targeted screening B. Universal screening |

A. TEOAE followed by ABR | NR, Health System | Case detected | For every 100,000 newborns screened, universal screening detected 86 of 110 cases of congenital hearing loss, at a cost of $11,650 per case identified. Targeted screening identified 51 of 110 cases, at $3120 per case identified. | 63 |

| Brown 1992 | Decision Tree | UK/Europe, Children, Unclear | A. No screening B. Conventional screening (1st screen at 8–9 months by health visitor, 2nd screen at 10 months by medical officer) C. Screening at 10 months only if clinical indication/concern |

NA | NR, Modified Societal | Unit output | Cost per unit output: - £20.57 for the conventional screening - £11.23 for Alternative policy 1 - £11.23 for Alternative policy 2 - £11.13 for Alternative policy 3 - £11.27 for No screening |

60 |

| Turner 1992 | Decision Tree | United States, Children, Unclear | A. No screening B. Universal screening |

A. High risk register test B. ABR |

NR, Payer | Infant identified | NA | 30 |

| Prager et al. 1987 | Decision Tree | United States, Children | –-NA | A. ABR B. Crib-O-Gram |

Episode of care, Payer | Hearing loss case detected | Crib-O-Gram cost $14,310 per case detected. | 68 |

| Child Screening | ||||||||

| Fortnum et al. 2016 | Decision Tree | UK/Europe, Children with CHL and b/l SNHL | A. No Screening B. School Entry Screening |

A. Pure-tone screen B. HearCheck screen |

Lifetime, Health System | QALY | No screening was dominant over screening. Screening using pure-tone screening was dominant over screening using the HearCheck screener. | 100 |

| Nguyen et al. 2015 | Markov | Australia/NZ, Children with Mixed HL | A. Deadly Ears Program (outreach ENT surgical service and screening program) B. Deadly Ears Program + with mobile telemedicine-enabled screening and surveillance service |

NA | Ages 3–18 to age 50, Societal | QALY | The ICER of MTESS (mobile telemedicine-enabled screening and surveillance) + Deadly Ears vs Deadly ears alone was AUD $656/QALY gained | 94 |

| Baltussen et al. 2012 | Dynamic | Africa, Asia, Children and Adults with Mixed HL | A. Passive Child Screening B. Annual Primary School Screening C. Annual Secondary School Screening D. Annual Primary+Secondary School Screening |

NA | Lifetime, Modified Societal | DALY | The cost per DALY averted was < I$285 for all hearing loss interventions. | 100 |

| Baltussen et al. 2009 | Dynamic | Africa, Asia, Children and Adults, Unclear | A. Passive screening B. Primary School screening C. Secondary school screening D. Primary and secondary school screening E. Adult screening q5 years F. Adult screening q10 years |

Pure tone audiometry | Lifetime, Societal | DALY | Findings showed that in both regions, screening strategies for hearing impairment and delivery of hearing aids cost between I$1000/DALY and I$1600/DALY, with passive screening being the most efficient intervention. Active screening at schools and in the community were somewhat less cost-effective. In the treatment of chronic otitis media, aural toilet in combination with topical antibiotics costs was more efficient than aural toilet alone, and cost between I$11 and I$59/DALY in both regions. The treatment of meningitis with ceftriaxone cost between I$55 and I$217/DALY at low coverage levels, in both regions. | 94 |

| Rob et al. 2009 | Decision Tree | Asia, Children and Adults, Unclear | A. Passive screening and fitting at tertiary care center B. Active screening and fitting at secondary care level |

NA |

5 years, Payer and Modified Societal |

DALY | The cost per DALY averted was around Rs 42,200 (US$900) at secondary care level and Rs 33,900 (US$720) at tertiary care level. | 86 |

| Bamford et al. 2007 | Decision Tree | UK/Europe, Children with Mixed Hearing Loss | A. No Screening B. Targeted School Entry Screening C. Universal School Entry Screening |

A. Pure tone sweep audiometry B. Parental questionnaire C. Tympanometry D. Spoken word test |

1-year, Societal | QALY | Universal school entry screening based on pure-tone sweep tests was associated with higher costs and slightly higher QALYs compared with no screen and other screen alternatives; ICER = £2500/QALY gained. The range of expected costs, QALYs, and net benefits was broad. | 92 |

| Brown, 1992 | Decision Tree | UK/Europe Children, Unclear | A. No Screening B. Conventional screening (1st screen at 8–9 months by health visitor, 2nd screen at 10 months by medical officer) C. Screening at 10 months only if clinical indication/concern |

NA | NR, Modified Societal | Other | Cost per unit output: - £20.57 for the conventional screening - £11.23 for Alternative policy 1 - £11.23 for Alternative policy 2 - £11.13 for Alternative policy 3 - £11.27 for No screening |

60 |

| Adult Screening | ||||||||

| Garcia et al. 2018 | Markov | United States Adults, Unclear | A. No screening B. Annual screening |

NA | 20 years, Payer | Hearing loss avoided | The ICER of a hearing conservation program was $10,657 per case of hearing loss prevented. | 89 |

| Linssen et al. 2015 | Markov | UK/Europe Adult, NR | A. Age at first screening (50, 55, 60, 65, or 70 years) B. Number of repeated screenings (up to five repetitions) C. Time interval between repeated screenings (5 or 10 years). |

A. No screening B. Telephone screening C. Internet screening D. Handheld device (HearCheck) E. Audiometric screening |

Lifetime, Health System | QALY | Incremental costs of the screening strategies compared with no screening ranged from €4 to €59. Incremental QALYs ranged from 0.0003 to 0.0104. The ICERs of all the screening strategies compared with the current practice were below €20,000/QALY gained. | 94 |

| Morris et al. 2013 | Markov | UK/Europe Adults with b/l SNHL | A. One-stage audiometric screen (60–70 y/o adults) B. Two-stage screen (postal questionnaire + audiometric) C. GP Referral |

NA | Lifetime, Health System | QALY | The ICER of one-stage screening for 35 dB HL from 60 years vs. GP referrals was £1461. Two-stage screening was eliminated by extended dominance. | 100 |

| Baltussen et al. 2012 | Dynamic | Africa, Asia, Children and Adults with Mixed HL | A. Passive Adult Screening B. Adult Screening q5 years C. Adult Screening q10 years |

NA | Lifetime, Modified Societal | DALY | The cost per DALY averted was < I$285 for all hearing loss interventions. | 100 |

| Liu et al. 2011 | Other/Unclear | United States Adults with SNHL | NA | A. No Screening B. Tone-emitting otoscope C. Self-administered questionnaire D. Otoscope + questionnaire |

1 year, Payer | Probability of hearing aid use after one year | The tone-emitting otoscope was the most cost-effective strategy, with a significant increase in hearing aid use 1 year after screening (2.8%) and an ICER of $1439.00 per additional hearing aid user compared with the control group. | 52 |

| Morris 2011 | Markov | UK/Europe Adults, Other NR | Twelve screening scenarios that vary according to 1. age at first screen (55, 60 or 65 years), 2. target hearing loss (better ear average ≥30 dB HL or ≥35 dB HL) and 3. one- or two-stage screening program |

NA | Lifetime, Health System | QALY | The ICER of screening compared to GP referral service ranged from £1266 to £2185. | 55 |

| Baltussen et al. 2009 | Dynamic | Africa, Asia, Adults and Children, Unclear | A. Passive screening B. Primary School screening C. Secondary school screening D. Primary and secondary school screening E. Adult screening q5 years F. Adult screening q10 years |

Pure tone audiometry | Lifetime, Societal | DALY | Findings showed that in both regions, screening strategies for hearing impairment and delivery of hearing aids cost between I$1000/DALY and I$1600/DALY, with passive screening being the most efficient intervention. Active screening at schools and in the community were somewhat less cost-effective. In the treatment of chronic otitis media, aural toilet in combination with topical antibiotics costs was more efficient than aural toilet alone, and cost between I$11 and I$59/DALY in both regions. The treatment of meningitis with ceftriaxone cost between I$55 and I$217/DALY at low coverage levels, in both regions. | 94 |

| Rob et al. 2009 | Decision Tree | Asia, Adults and Children, Unclear | A. Active Screening and Fitting at Secondary Care Level B. Passive Screening and Fitting at Tertiary Care Level |

NA | 5 years, Payer and Modified Societal | DALY | The cost per DALY averted was around Rs 42,200 (US$900) at secondary care level and Rs 33,900 (US$720) at tertiary care level. | 86 |

*Main Cost-Effectiveness findings cost-effectiveness ratios and costs are presented in the published currency and year.

Abbreviations: AABR – automated auditory brainstem response, ABR – auditory brain response, b/l: bilateral, AOAE – automatic otoacoustic emissions, cCMV – congenital cytomegalovirus, CE – cost-effectiveness, CHL – conductive hearing loss, CI – cochlear implant, COG – Crib-O-Gram, DALY – disability-adjusted life years, GP- general practitioner, HA – hearing aid, HL – hearing loss, (I)CER – (incremental) cost-effectiveness ratio, NA – not applicable, NR – not reported, OAE - Otoacoustic emissions, PCR – polymerase chain reaction, RHC – regional hearing center, SNHL – sensorineural hearing loss, UK – United Kingdom, US – United States.

Currencies: € – Euro, I$ – International Dollars, INR/Rs – Indian Rupee, £ – Pound.

3.3. Studies evaluating cochlear implantation

Thirty-four identified analyses considered cochlear implantation (CI) as a comparator intervention (Table 4; Table 1, Batch 24). Locations of analyses included 10 in Europe (Table 1, Batch 25); thirteen in North America (Table 1, Batch 26); five in Asia (Table 1, Batch 27); four in Australia or New Zealand (Table 1, Batch 28); one in South America [131]; and one in Africa [114]. The most commonly studied interventions were unilateral and bilateral CI (33 studies, 97%; Table 1, Batch 29), with eight studies directly comparing unilateral vs. bilateral CI (Table 1, Batch 30). Other interventions included bimodal hearing technology (CI+HA; four studies; Table 1, Batch 31), deaf education (five studies; Table 1, Batch 32), and hearing aids (HA) (ten studies; Table 1, Batch 33). Simultaneous CI implantation was compared to sequential CI implantation in five studies (Table 1, Batch 34). Abstracted economic parameters included one-time CI device and procedure costs (including costs of surgery/anesthesia, and initial audiology programming of device) as well as recurring costs for CI processor updates. CI device and procedure costs ranged from $11,560–63,970, differing by setting and analysis. Seventy-one percent of studies (n = 24) included CI processor update costs, and these costs were aggregated and assessed either yearly or once per lifetime (Table 1, Batch 35).

Table 4.

Included Studies Evaluating Cochlear Implantation.

| Reference | Model Type | Setting and Population, HL Type | Comparators | Time Horizon, Perspective | Utility Values: value (health state) | CI Device + Procedure Costs† | CI processor update time + cost† | Indirect Economic Costs | Main Cost-Effectiveness Findings* | Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series 2020 | Markov | Canada, Children and Adults with CHL and Mixed HL | A. No Intervention B. Bone Conduction Implant C. CI |

10 years, 25 years, Payer | 0.56 (U/l deafness) +0.24 (CI) |

$350 (adult pre-op) $630 (child pre-op) $24,530 (total procedural costs) |

$4270 - $8640 (Processor replacement, q5–10 years) | No | Among people with single-sided deafness, cochlear implants may be cost-effective compared with no intervention, but bone-conduction implants are unlikely to be. Among people with conductive or mixed hearing loss, bone-conduction implants may be cost-effective compared with no intervention. | 100 |

| Cheng et al. 2019 | Markov | Asia, Children with b/l SNHL | A. Bimodal (CI + HA) B. Simultaneous b/l CI C. Sequential b/l CI |

Lifetime, Payer | +0.066 (bimodal, 1 year) +0.167–0.212 (bimodal, after 1 year) +0.009 (b/l CI vs. bimodal, 1 year) +0.0216–0.03 (b/l CI vs. bimodal, after 1 year) |

$35,350 | NA | No | Simultaneous bilateral cochlear implant compared to bimodal hearing had an ICER of $60,607/ QALY. Sequential bilateral cochlear implantation compared to bimodal had an ICER of $81,782/QALY. | 94 |

| Emmett et al. 2019 | Decision Tree | Asia, Children with SNHL | A. No Intervention B. Deaf Education C. CI |

10 years, Modified Societal | Unclear | $11,560 - $27,750 | $45,970 - $112,850 (over lifetime) | Yes: Education |

Deaf education was cost-effective in all countries except Nepal (CER/GDP, 3.59). CI was cost-effective in all countries except Nepal (CER/GDP, 6.38) and Pakistan (CER/GDP, 3.14). | 56 |

| Fang et al. 2019 | Markov | Asia, Children with b/l SNHL | A. B/l HA B. Bimodal (CI+HA) |

Lifetime, Payer | 0.066 (bimodal, 1 year) +0.167–0.212 (bimodal, after 1 year) +0.009 (b/l CI vs. bimodal, 1 year) +0.0216–0.03 (b/l CI vs. bimodal, after 1 year) |

$34,490 | $9,010 (q10 years) | No | The ICER for bimodal was $6487/QALY. | 100 |

| Laske et al. 2019 | Markov | UK/Europe, Adults with SNHL | A. HA B. U/l CI C. Sequential CI |

Lifetime, Unclear | NA | $54,080 |

$13,070 (q10 years) | No | Unilateral CI was CE compared to HA in women up to age 91 and men 89. Sequential CI compared to HA was CE for up to 87 in women and 85 for men. Sequential CI was CE compared to unilateral CI up to age 80 in women and 78 in men. | 81 |

| Theriou et al. 2019 | Decision Tree, Markov | UK/Europe, Adults with b/l SNHL | A. U/l CI B. Bimodal (CI + HA) C. B/l CI |

Lifetime, Payer | 0.433 (non-surgical) 0.478 (U/l CI) 0.510 (bimodal) |

$24,310 | Upgrade: $5290 Tuning/maintenance: $6,430 (year 1) $1,030 (year 2) $970 (year 3) $770 (year 4+) |

No | Bimodal had an ICER of £1,521/QALY in UK and $8,192 in US. The value of further research was £4.8 M at 20,000/QALY in UK and $87.0 M at $50,000/QALY in US. | 100 |

| Ontario Health Technology Assessment 2018 | Markov | Canada, Children and Adults with b/l SNHL | A. U/l CI B. B/l CI |

Lifetime, Payer and Societal | 0.495 (no CI, adult) 0.765 (u/l CI, adult) 0.800 (b/l CI, adult) 0.585 (no CI, pediatric) 0.780 (u/l CI, pediatric) 0.830 (b/l CI, pediatric) |

$24,170 (u/l CI, adult): $24,390 (u/l CI, pediatric) |

$4370 (q3 years) | Yes: Employment, Caregiver/Family | Bilateral CI ICER: Adult post-lingual: $48,978/QALY Child prelingual: $27,427/QALY Child post-lingual: $30,386/QALY |

100 |

| Montes et al. 2017 | Diagram | South America, Children with b/l SNHL | A. No Intervention B. HA C. CI |

Lifetime, Modified Societal | 1.000 (mild HL) 0.880 (moderate, untreated) 0.960 (moderate, treated) 0.667 (severe or profound, untreated) 0.880 (severe or profound, treated) |

$23,610 (surgery kit + 7 assessments) | NA | Yes: Education, Employment, Health Insurance | The ICER for CI was $15,169/QALY, and for HA was $15,430/QALY. | 68 |

| Perez-Martin et al. 2017 | Markov | UK/Europe, Children with b/l SNHL | A. U/l CI B. Sequential CI C. Simultaneous B/l CI |

Lifetime, Payer | +0.106 (second CI) | $24,740 (u/l CI) | $7,420 (Processor replacement, timing unclear); $1,530 (internal replacement, depends on device age); $800 (yearly maintenance, adults); $440 (yearly maintenance, pediatric) |

No | The ICER for simultaneous bilateral CI for 1 year old was €10,323/QALY. The ICER for sequential bilateral CI for 1 year old is €11,733/QALY. | 86 |

| Qiu et al. 2017 | Decision Tree | Asia, Children with b/l SNHL | A. No CI (HA or no intervention) B. U/l CI |

Lifetime, Payer and Patient | 0.50 (HL) 0.61 (HA) 0.55 (Pre-surgery) 0.77 (6 months post-CI) 0.81 (12+ months post-CI) |

HC Payer Perspective: $23,560 HC Payer + Patient Perspective: $30,420 |

$28,110 (Processor Replacement, HC + Patient Perspective; q6 years) |

No | The ICER for the Payer + Patient perspective was 100,561 CNY/QALY ($15,084/QALY). The ICER for the Payer perspective was 40,929 CNY/QALY ($6139/QALY). Both were below 3x Chinese GDP. | 100 |

| Emmett et al. 2016 | Decision Tree | Latin America, Children with b/l SNHL | A. No Intervention B. Deaf Education C. CI |

10 years, Modified Societal |

Unclear |

$24,540 - $37,410 | $60,210 - $97,860 (q10 years) | Yes: Education | Deaf education was very cost effective in all countries (CER/GDP 0.07 – 0.93). CI was cost-effective in all countries (CER/GDP 0.69 – 2.96). | 60 |

| Foteff et al. 2016 (1) | Markov | Australia/NZ, Adults with b/l SNHL | A. B/l HA B. U/l CI C. Sequential b/l CI D. Simultaneous b/l CI |

Lifetime, Payer | 0.495 (HA) 0.765 (u/l CI) |

$37,590 | $8,570 (q5 years) | No | Compared with bilateral hearing aids, the incremental cost-utility ratio for the CI treatment population was AUD 11,160/QALY. | 100 |

| Foteff et al. 2016 (2) | Markov | Australia/NZ, Children with b/l SNHL | A. No Intervention B. B/l HA C. Mixed U/l and B/l CI |

Lifetime, Payer and Societal | +0.23 (b/l HA) +0.125 (u/l CI vs. HA) +0.063 (sequential b/l CI vs. u/l CI) |

$38,500 (device and post-operative costs) | $8,530 (replacement sound processor, q5 years) | Yes: Education | The ICER for unilateral CI compared with HAs was AUD 21,947/QALY. Weighted combined CI compared with HAs had an ICER of AUD 31,238/ QALY. |

100 |

| Emmett et al. 2015 | Decision Tree | Africa, Children with b/l SNHL | A. No Intervention B. Deaf Education C. CI |

10 years, Modified Societal | +0.02–0.04 (CI) | $28,340 - $46,750 | $41,310 - $73,700 (maintenance q10 years) | Yes: Education | CI was CE in South Africa and Nigeria: CER/GDP was 1.03 and 2.05. Deaf education was CE in South Africa, Nigeria, Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda, Malawi with CER/GDP ranging from 0.55 to 1.56. |

66 |

| Saunders et al. 2015 | Decision Tree | Latin America, Children with b/l SNHL | A. No Intervention B. Deaf Education C. CI |

10 years, Societal and Modified Societal | +0.02–0.04 (CI) | $17,590 | NA | Yes: Education | Costs per DALY averted were $5,898 and $5,529 for CI and deaf education, respectively. | 80 |

| Chen et al. 2014 | Decision Tree | Canada, Adults with b/l SNHL | A. No Intervention B. U/l CI C. B/l CI |

25 years, Payer | 0.495 (No intervention) 0.765 (u/l CI) |

$40,340 | $24,260 (q5 years) | No | The ICER for bilateral CI compared to no intervention was $14,658/QALY. The ICUR was $55,020/QALY comparing unilateral to bilateral CI. | 71 |

| Semenov et al. 2013 | Decision Tree | United States, Children with b/l SNHL | A. Deaf Education B. CI at <18 months C. CI at 18–36 months D. CI at >36 months |

Lifetime, Societal | Age <18 months: 0.26 (pre-implantation) 0.76 (6 years post-implantation) Age 18–26 months: 0.31 (pre-implantation) 0.72 (6 years post-implantation) Age > 36 months: 0.37 (pre-implantation) 0.71 (6 years post-implantation) |

$47,510 | $15,020 (lifetime) | Yes: Education, Employment, Transportation, Caregiver/Family | CI led to net societal savings of $31,252, $10,217, and $6680 for ages <18 months, 18–36 months, 36 months. | 94 |

| Summerfield et al. 2010 | Markov | UK/Europe, Children with b/l SNHL | A. Bimodal (CI+HA) B. B/l CI |

Lifetime, Payer | + 0.145 (u/l vs. nonsurgical) + 0.063 (b/l vs. u/l CI) |

$51,630 | $10,140 (q10 years) | No | The net benefit was positive, provided that £21,768 could be spent to gain a QALY. | 100 |

| Bond et al. 2009 | Markov | UK/Europe, Children and Adults with b/l SNHL | A. No Intervention B. U/l CI C. B/l Sequential CI D. B/l Simultaneous CI |

Lifetime, Payer | 0.433 (Pre-Implantation Adults) 0.630 (Post-Implantation at 9 months, Adults) 0.353–0.616 (Pre-Implantation, Pediatric) +0.066–0.232 (CI, Pediatric) |

$40,700 (u/l CI, adults) $42,260 (u/l CI, children) |

$9,610 (adults and children; q10 years) | No | In prelingually deaf children, the ICER for u/l CI was £13,413/QALY, £40,410/QALY for simultaneous b/l CI, and 54,098/QALY for sequential b/l CI. In post-lingually deaf adults, the ICER for u/l CI was £14,163, for simultaneous b/l CI was £49,559, and for sequential b/l CI was £60,301/QALY. |

100 |

| Bichey et al. 2008 | Decision Tree | United States, Children and Adults with b/l SNHL |

A. No CI B. B/l CI |

Lifetime, Societal | 0.33 (before first CI) 0.69 (before second CI) 0.81 (after second CI) |

$55,370 | NA | No | Results indicated a 0.48 mean gain in health utility after bilateral cochlear implantation and a discounted cost of $24,859/QALY in this cohort of patients. | 49 |

| UK Cochlear Implant Study Group 2004 | Decision Tree | UK/Europe, Adults with b/l SNHL | A. No intervention B. HA C. U/l CI |

Lifetime, Payer | 0.433 (pre-implantation) 0.611 (3-month post-implant 0.630 (9-month post-implant) |

$51,310 | $11,010 (q10 years) | No | Unilateral CI in post lingually deafened adults had an ICER of €27,142/QALY. | 87 |

| Bichey et al. 2002 | Other | Canada, Children and Adults with b/l SNHL | A. HA B. CI |

Lifetime, Payer | 0.82 (CI) | $53,020 | NA | No | Cochlear implantation vs hearing aid had an ICER of $12,774/QALY. | 43 |

| Francis et al. 2002 | Decision Tree | United States, Adults with b/l SNHL | A. No Intervention B. CI |

Lifetime, Payer | 0.70 (Pre-Implantation) 0.85 (Post-Implantation) |

$51,180 | NA | No | CI in older adults had a cost-utility of $9,530/QALY. | 57 |

| Summerfield et al. 2002 | Other | UK/Europe, Adults with b/l SNHL | A. No Intervention B. Acoustic HA C. U/l CI D. Simultaneous b/l CI E. Sequential b/l CI |

30 years, Payer | 0.562 (profound HL, no benefit from HA); 0.725 (profound HL, marginal benefit from HA); 0.750 (traditional benefit from a u/l CI); 0.802 (marginal HA user benefiting from a u/l CI); 0.765 (profound HL, no benefit from HA); 0.836 (severe HL, marginal benefit from HA); 0.934 (benefiting from a u/l CI); 0.965 (benefiting from a b/l CI) |

$46,120 | $1600 - $1800 (q1 year, post year 4) | No | The ICERs were £16,774 for type 1: unilateral implantation vs no intervention, £27,401 for type 2: unilateral implantation vs management with hearing aids, £61,734 for simultaneous bilateral implantation vs unilateral implantation, and £68,916 for provision of an additional implant vs no additional intervention. | 69 |

| Cheng et al. 2000 | Decision Tree | United States, Children with b/l SNHL | A. No Intervention B. CI |

Lifetime, Societal | 0.25 (Pre-Implantation) 0.64 (Post-Implantation) |

$40,560 | $9490 | Yes: Education, Employment, Transportation, Caregiver/Family | The CI ICER was $9,029/QALY using the TTO, $7,500/QALY using the VAS, and $5,197/QALY using the HUI. CI was cost-saving when educational impact was included. | 100 |

| Wong et al. 2000 | Decision Tree | Asia, Children and Adults with b/l SNHL | A. No Intervention B. CI |

Lifetime, Payer | +0.1229 (CI, adult) +0.1266 (CI, pediatric) |

NA | NA | No | The ICER for unilateral cochlear implantation was HK$133,087/QALY in adults and HK$183,100/QALY in children. | 32 |

| Carter et al. 1999 | Decision Tree | Australia/NZ, Children and Adults with SNHL | A. No Intervention B. CI |

10-years, 15-years, 20-years, Payer | +0.0434–0.0484 (CI) | $30,500 | NA | Yes: Education | Costs in AUD per QALY (15-year assessment) ranged from $5,070–$11,100 for children, $11,790–$38,150 for profoundly deaf adults, and $14,410– $41,000 for partially deaf adults. | 92 |

| Summerfield et al. 1997 | Decision Tree | UK/Europe, Children and Adults with b/l SNHL | A. No Intervention B. CI |

Lifetime, Payer | 0.58 (Pre-implantation) 0.81 (Post-implantation) |

NA | NA | Yes: Education | CI had an ICER of £15,600/QALY. | 51 |

| Wyatt et al. 1996 | Decision Tree | United States, Adults with b/l SNHL | A. No Intervention B. CI |

Lifetime, Payer | 0.59 (Pre-implantation) 0.79 (Post-implantation) |

$62,890 | $12,340 (cost of follow-up; audiologic testing and device maintenance) | No | The ICER for CI was $15,928/QALY. | 76 |

| Hutton et al. 1995 | Decision Tree | UK/Europe, Children with b/l SNHL | A. No Intervention B. CI | Lifetime, Societal | 0.60 (HL) 0.70 (CI) |

$2,090 (Pre-op Eval); $39,770 (Implantation) |

NA | Yes: Education | CI in children had an ICER of £16,214/QALY. | 55 |

| Lea et al. 1995 | Decision Tree | Australia/NZ, Children and Adults with b/l SNHL | A. No Intervention B. CI | 10 years, Payer | −0.17 (HL) +0.7–0.15 (CI) |

$21,170 (device) $2490 (procedure) |

$500 (Threshold checks, twice per year first 3 years) $250 (Threshold checks, yearly years 4+) |

No | CI had an ICER of $14,000/QALY in children and $22,000/QALY in adults. | 28 |

| Summerfield et al. 1995 | Decision Tree | UK/Europe, Children and Adults, Unclear | A. No Intervention B. CI | 12 years, Payer | 0.53 (Pre-implantation) 0.67 (Post-implantation) |

$11,650 (implantation); $34,320 (device) |

$1,860 (yearly maintenance, adults) $3,020 (yearly maintenance, pediatric) |

No | The cost of gaining 1 QALY through multichannel implantation in adulthood was between £8,624–25,871. | 74 |

| Wyatt et al. 1995 (1) | Decision Tree | United States, Adults, Unclear | A. No Intervention B. U/l CI |

Lifetime, Payer | +0.30 (CI) | $3,020 (Pre-op eval) $20,500 (Surgery) $33,260 (Device) |

$1,000 (Maintenance costs, every 2 years, years 4+) | No | The ICER for CI was $9,325/QALY, with a range of $7,988-$11,201/QALY. | 91 |

| Wyatt et al. 1995 (2) | Decision Tree | United States, Adults with b/l SNHL | A. No Intervention B. CI |

Lifetime, Payer | +0.27 (CI) | $63,970 (CI Device + procedure costs) | $14,160 (cost of follow-up; audiologic testing and device maintenance) | No | The ICER for cochlear implantation was $15,600/QALY. | 75 |

*Main Cost-Effectiveness findings cost-effectiveness ratios and costs are presented in the published currency and year.

†Cochlear implant device and procedure costs, and cochlear implant processor update time and cost are adjusted to 2019 USD.

Abbreviations: b/l – bilateral, CE – cost-effectiveness, CI – cochlear implant, DALY – disability-adjusted life years, GDP – gross domestic product, HA – hearing aid, HL – hearing loss, HUI – health utilities index, (I)CER – (incremental) cost-effectiveness ratio, ICUR – incremental cost-utility ratio, QALY – quality-adjusted life years, SNHL – sensorineural hearing loss, u/l – unilateral, TTO – Time Trade Off, UK – United Kingdom, US – United States.

Currencies: AUD – Australian Dollar, CNY – Chinese Yuan, € – Euro, HK – Hong Kong Dollar, I$ – International Dollar, INR/Rs – Indian Rupee, £ – Pound.

3.4. Studies evaluating hearing aids

Twenty-eight studies conducted cost-effectiveness analyses that included hearing aids as an intervention (Table 5). Acoustic (i.e. traditional) hearing aids were included in 24 studies (Table 1; Batch 36), while five studies evaluated bone conduction devices (Table 1, Batch 37). Hearing aids were most commonly evaluated in comparison to cochlear implantation (n = 9; Table 1, Batch 38). Eight studies compared hearing aid provision to no intervention, assessing the cost-effectiveness of acoustic hearing aids themselves (Table 1, Batch 39). Costs for non-implantable hearing aid device and fitting ranged from $40–7130, again varying by setting (LMIC vs. high-income country) and analysis. Sixteen of the 28 studies (57%) included recurring costs for hearing aid batteries, device replacement, device repairs, or combinations of these costs (Table 1, Batch 40).

Table 5.

Included Studies Evaluating Hearing Aids.

| Reference | Model Type | Setting and Population, HL Type | Comparators | Time Horizon, Perspective | Utility Values: value (health state) | HA Device + fitting costs† | HA recurring costs† | Indirect Economic Costs | Main Cost-Effectiveness findings* | Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acoustic (i.e. traditional) Hearing Aids | ||||||||||

| Cheng et al. 2019 | Markov | Asia, Children with b/l SNHL | A. Bimodal (u/l CI + HA) B. Simultaneous bilateral CI C. Sequential bilateral CI |

Lifetime, Payer | +0.066 (bimodal, 1 year) +0.167–0.212 (bimodal, after 1 year) +0.009 (b/l CI vs. bimodal, 1 year) +0.0216–0.03 (b/l CI vs. bimodal, after 1 year) |

$990 | NA | No | Simultaneous bilateral cochlear implant compared to bimodal hearing had an ICER of $60,607/ QALY. Sequential bilateral cochlear implantation compared to bimodal had an ICER of $81,782/QALY. | 94 |

| Fang et al. 2019 | Markov | Asia, Children with b/l SNHL | A. Bilateral HA B. Bimodal (CI+HA) |

Lifetime | 0.066 (bimodal, 1 year) +0.167–0.212 (bimodal, after 1 year) +0.009 (b/l CI vs. bimodal, 1 year) +0.0216–0.03 (b/l CI vs. bimodal, after 1 year) |

NA | $1700 (device, q5 years) | No | The ICER for bimodal was $6487/QALY. | 100 |

| Gillard and Harris 2019 | Decision Tree, Markov | United States, Adults with CHL | A. Stapedectomy B. HA |

Lifetime, Payer and Patient | 0.61 (HL) | $2350 | $580 (yearly cost) | No | In otosclerosis, stapedectomy had an ICER of $3918.43/QALY compared to hearing aids. | 81 |

| Laske et al. 2019 | Markov | UK/Europe, Adults with SNHL | A. U/l CI B. Sequential CI C. HA |

Lifetime | +0.28 (u/l CI vs HA) +0.38 (sequential CI vs. HA) +0.1 (sequential CI vs u/l CI) |

$6500 |

$60 (batteries, yearly) $360 (specialist consult q2 years) $6500 (replacement) |

No | Unilateral CI was CE compared to HA in women up to age 91 and men 89. Sequential compared to HA was CE for up to 87 in women and 85 for men. Sequential CI was CE compared to unilateral CI up to age 80 in women and 78 in men. | 81 |

| Theriou et al. 2019 | Decision Tree, Markov | UK/Europe, Adults with b/l SNHL | A. U/l CI B. Bimodal (CI + HA) C. B/l CI |

Lifetime, Payer | NA | $270 | NA | No | Bimodal had an ICER of £1521/QALY in UK and $8192 in US. The value of further research was £4.8 M at 20,000/QALY in UK and $87.0 M at $50,000/QALY in US. | 100 |

| Montes et al. 2017 | Diagram | South America, Children with b/l SNHL | A. No Intervention B. HA C. CI |

Lifetime, Modified Societal | 1.000 (mild HL) 0.880 (moderate, untreated) 0.960 (moderate, treated) 0.667 (severe or profound, untreated) 0.880 (severe or profound, treated) |

$1450 | NA | Yes: Education, Employment, Health Insurance | The ICER for CI was $15,169/QALY, and for HA was $15,430/QALY. | 68 |

| Foteff et al. 2016 (1) | Markov | Australia/NZ, Adults with b/l SNHL | A. B/l HA B. U/l CI C. Sequential b/l CI D. Simultaneous b/l CI |

Lifetime, Payer | 0.495 (HA) 0.765 (u/l CI) |

$3560 | $3180 (q5 years); $500 (first 12 months) $490 (Annual audiology follow-up for 5 years) |

No | Compared with bilateral hearing aids the incremental cost-utility ratio for the CI treatment population was AUD 11,160/QALY. | 100 |

| Foteff et al. 2016 (2) | Markov | Australia/NZ, Children with b/l SNHL | A. No Intervention B. B/l HA C. Mixed u/l and b/l CI |

Lifetime, Payer and Societal | +0.23 (b/l HA) +0.125 (u/l CI vs. HA) +0.063 (sequential b/l CI vs. u/l CI) |

$6360 (device) $770 (fitting cost) |

$6360 (q5 years); $490 (annual audiology follow-up for q5 years) |

Yes: Education | The ICER for unilateral CI compared with HAs was AUD 21,947/QALY. Weighted combined CI compared with HAs had an ICER of AUD 31,238/ QALY. |

100 |

| Bruce et al. 2015 | Decision Tree | UK/Europe, children with CHL | A. Ventilation Tubes B. HA C. HA + ventilation tubes D. Do Nothing Strategy |

24 months, Health Systems | +0.00874 (per unit increase in dBHL) | NA | NA | No | VTs vs. do nothing had an ICER of £9065 per QALY gained. Other strategies are dominated. | 100 |

| Mohiuddin et al. 2015 | Decision Tree | UK/Europe, Children with CHL | A. No Intervention B. HA C. Grommets |

2 years, Health Systems | +0.00874 (per unit increase in dBHL) | NA | NA | No | The ICER of Grommets strategy vs. do-nothing was £9065/QALY gained. Hearing-aids strategy was extendedly dominated by the grommets strategy. | 100 |

| Fortnum et al. 2014 | Unclear | UK/Europe, Children with CHL | A. HA B. Surgery C. Watchful Waiting |

2 years, Health Systems | +0.00874 (per unit increase in dBHL) | NA | NA | No | The most cost-effective strategy for a child with Down syndrome experiencing OME-induced hearing loss was watchful waiting, followed by symptom management using HAs. | 100 |

| Mohiuddin et al. 2014 | Decision Tree | UK/Europe, Children with CHL | A. Ventilation Tubes B. HA C. HA + Ventilation Tubes |

2 years, Health Systems | +0.00874 (per unit increase in dBHL) | NA | NA | No | The ICER for VTs strategy compared with the HAs strategy was £5086/QALY gained. | 100 |

| Summerfield et al. 2010 | Markov | UK/Europe, Children with b/l SNHL | A. Bimodal (CI+HA) B. B/l CI |

Lifetime, Payer | NA | $250 | $250 (q5 years) | No | Net benefit was positive, provided that £21,768 could be spent to gain a QALY. | 100 |

| Baltussen et al. 2009 | Dynamic | Africa, Asia, Children and Adults, Unclear | A. Screening + HA B. Chronic otitis media treatment: aural toilet +/- topical abs C. Meningitis treatment: Ceftriaxone |

Lifetime, Societal | 0.88 (untreated moderate HL) 0.96 (treated moderate HL) 0.667 (untreated severe HL) 0.88 (treated severe HL) |

$110 (device) $20 (fitting) |

$110 (device replacement q4 years) | No | Findings showed that in both regions, screening strategies for hearing impairment and delivery of hearing aids cost between I$1000/DALY and I$1600/DALY, with passive screening being the most efficient intervention. Active screening at schools and in the community were somewhat less cost-effective. In the treatment of chronic otitis media, aural toilet in combination with topical antibiotics costs was more efficient than aural toilet alone, and cost between I$11 and I$59/DALY in both regions. The treatment of meningitis with ceftriaxone cost between I$55 and I$217/DALY at low coverage levels, in both regions. | 94 |

| Rob et al. 2009 | Decision Tree | Asia, Children and Adults, Unclear | A. Passive screening and fitting at tertiary care center B. Active screening and fitting at secondary care level |

5 years, Payer and Modified Societal | −0.216 (untreated deafness in adults) −0.168 (treated deafness in adults) |

$40 | NA | Yes: Employment, Transportation | The cost per DALY averted was around Rs 42,200 (US$900) at secondary care level and Rs 33,900 (US$720) at tertiary care level. | 86 |

| Chao and Chen 2008 | Markov | Asia, Adults (50–80 years old), Unclear | A. No Intervention B. HA |

30 years, Societal | 0.78 (HA) | $1350 | $30 - $80 (batteries); $20 (yearly for repair) |

Yes: Employment, Transportation | HA ICERs for women and men were US $13,615/QALY (€ 10,826) and $9702/QALY (€7715), respectively. | 97 |

| Grutters et al. 2008 | Markov | UK/Europe, Adults, Unclear | A. Current Care Delivery B. Total direct care C. Triage care format D. Follow-up care format |

Lifetime, Societal | Acoustic neuroma 0.35–0.42 (no HA) 0.41–0.51 (HA) 0.23 (after treatment) Otitis media: 0.52 (no HA) 0.56 (HA) Otosclerosis: 0.31–0.58 (no HA) 0.45–0.62 (HA) |

$830 (device) $530 (fitting) |

$80 (yearly maintenance); $40 (annual repairs) |

No | Follow-up format resulted in €10,972 saved/QALY lost. | 92 |

| UK Cochlear Implant Study Group 2004 | Decision Tree | UK/Europe, Adults with b/l SNHL | A. No intervention B. HA C. U/l CI |

Lifetime, Payer | 0.433 (Pre-implantation 0.611 (3-month post-implant) 0.630 (9-month post-implant) |

$730 | $520 (replacement, q3 years) | No | Unilateral CI in post lingually deafened adults had an ICER of €27,142/QALY. | 87 |

| Joore et al. 2003 | Markov | UK/Europe, Adults, Unclear | A. No intervention B. HA |

Lifetime, Societal | +0.03 (HA) | $1080 (Device) $480 (ENT fitting) $390 (Audiology fitting) |

$20 – $60 (batteries, yearly) $20 (repair costs, q5 years) |

Yes: Employment | The ICER for hearing aid fitting was €15,807/QALY (US $17,072/QALY). | 93 |

| Abrams et al. 2002 | Unclear | United States, Adults with SNHL | A. HA B. HA + Audiologic Rehabilitation |

Lifetime, Payer | +1.4 (SF-36 mental component scale, HA) +3.0 (SF-36 mental component scale, HA + rehabilitation) |

$1590 (HA + aural rehabilitation) $1510 (HA alone) |

NA | No | HA treatment cost $60.00/QALY gained compared to no treatment, while HA + audiologic rehabilitation cost only $31.91/QALY gained compared to no treatment. | 23 |

| Bichey et al. 2002 | Unclear | Canada, Children and Adults with b/l SNHL | A. HA B. CI |

Lifetime, Payer | 0.62 (HA) 0.82 (CI) |

NA | NA | No | Cochlear implantation vs hearing aid had an ICER of $12,774/QALY. | 43 |

| Summerfield et al. 2002 | Unclear | UK/Europe, Adults with b/l SNHL | A. No intervention B. Acoustic HA C. U/l CI D. Simultaneous b/l CI E. Sequential b/l CI |

30 years, Payer | 0.562 (profound HL, no benefit from HA); 0.725 (profound HL, marginal benefit from HA); 0.750 (traditional benefit from a u/l CI); 0.802 (marginal HA user benefiting from a u/l CI); 0.765 (profound HL, no benefit from HA); 0.836 (severe HL, marginal benefit from HA); 0.934 (benefiting from a u/l CI); 0.965 (benefiting from a b/l CI) |

$790 | $560 (device, q3 years) | No | The ICERs were £16,774 for type 1: unilateral implantation vs no intervention, £27,401 for type 2: unilateral implantation vs management with hearing aids, £61,734 for simultaneous bilateral implantation vs unilateral implantation, and £68,916 for provision of an additional implant vs no additional intervention. | 69 |

| Boas et al. 2001 | Markov | UK/Europe, Adults, Unclear | A. Fitting HA program B. Post-purchase counseling program |

Lifetime, Societal | +0.02 (HA) | $1120 (monaural device) $2230 (binaural device) $160 (fitting cost) |

NA | No | In the age group of 60–64 years old, the costs per QALY ratios of the Fitting HA Program and the Post-purchase counseling HA Program amounted to €21,154 and €18,046/QALY, respectively. | 53 |

| Bone Conduction Devices | ||||||||||

| Kruyt et al. 2020 | Markov | UK/Europe, Children and Adults with CHL and SNHL |

A. Flange fixture BAHA B. BI300 BAHA C. BI400 BAHA D. Ponto Wide BAHA |

10 years, Payer | NA | $1120 - $1530 (bone anchored hearing implant device); $1470 (implant surgery) |

$190 (yearly check-up) | No | Next generation implant was up to €506 more beneficial per patient over 10 years. | 100 |

| Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series, 2020 | Markov | Canada, Children and Adults with Conductive and Mixed HL | A. No Intervention B. Bone Conduction implant C. CI |

10 years, 25 years, Payer | 0.78 (u/l deafness) +0.06 (first 6-months after BAHA) +0.01 (12 months after BAHA) |

$290 (Adult pre-op); $140 (Child pre-op) |

$2360 - $4320 (Processor replacement q3–7 years) | No | Among people with single-sided deafness, cochlear implants may be cost-effective compared with no intervention, but bone-conduction implants are unlikely to be. Among people with conductive or mixed hearing loss, bone-conduction implants may be cost-effective compared with no intervention. | 100 |

| Kosaner et al. 2017 | Markov | Australia/NZ, Adults with SNHL | A. No intervention B. Active middle ear implants |

10 years, Payer | 0.57514 (pre- implementation); 0.66868 (six months after device use) |

$15,820 | NA | No | Active middle ear implants had an ICUR of AUD 9913.72/QALY. | 100 |

| Colquitt et al. 2011 | Decision Tree, Markov | UK/Europe, Children and Adults with b/l deafness | A. BCHA B. BAHA |

10 years, Payer | 0.465 (unable to hear at all) 0.644 (able to hear conversation with one person but not group) 0.849 (able to hear conversation with one person and with group) +0.178–0.385 (BAHA) |

$12,060 (adult BAHA) $2010 (adult HA) $15,930 (child BAHA) $2050 (child HA) |

$11,340 BAHA long-term maintenance costs (adult) $11,580 BAHA (pediatric) |

No | Incremental cost per QALY gained was between £55,642 and £119,367 for children and between £46,628 and £100,029 for adults for BAHAs compared with BCHA. | 100 |

| Monksfield et al. 2011 | Decision Tree | UK/Europe, Adults eligible for BAHD | A. HA B. BAHD |

Lifetime, Payer | 0.66 (post-implantation) | $12,420 (surgery + BAHD) $570 (digital HA) |

$2190 (BAHD yearly) $570 (q5 years) |

No | BAHD had an ICER of £17,610 (US $26,415) per QALY gained. | 82 |

*Main Cost-Effectiveness findings cost-effectiveness ratios and costs are presented in the published currency and year.

†Hearing aid device and fitting costs, and hearing aid recurring costs are adjusted to 2019 USD.

Abbreviations: BAHA – bone anchored hearing aid, BAHD – bone anchored hearing device, BCHA – bone conducting hearing aid, b/l – bilateral, CE – cost-effectiveness, CHL – conductive hearing loss, CI – cochlear implant, DALY – daily-adjusted life-years, dBHL - decibels hearing loss, HA – hearing aid, HL – hearing loss, (I)CER – (incremental) cost-effectiveness ratio, ICUR – incremental cost-utility ratio, OME – otitis media with effusion, QALY – quality-adjusted life year, SNHL – sensorineural hearing loss, u/l – unilateral, UK – United Kingdom, US – United States, VTs – ventilation tubes,.

Currencies: AUD – Australian Dollar, € – Euro, INR/Rs – Indian Rupee, I$ – International Dollar, £ – Pound.

3.5. Health outcome measures

Quality-adjusted life-years were the most commonly reported health outcome measure from included decision models, with 62% of studies reporting the main health outcome in QALYs (Table 1, Batch 41). Twelve percent of studies reported DALYs (Table 1, Batch 42), 5% reported life-years (Table 1, Batch 43), and 24% reported other outcome measures (Table 1, Batch 44). Utility values incorporated into economic analyses varied widely in terms of the impact of hearing loss on patient quality of life and the impact of hearing loss treatment on quality of life (Table 4, Table 5). Of the 86 studies that reported QALYs or DALYs, 24 derived their own utility values to calculate these health outcomes (Table 1, Batch 45).

3.6. Indirect economic costs

Untreated hearing loss has significant effects on labor force participation and educational attainment, and economic analyses may take such costs into account [149]. Forty-one studies (35%) incorporated indirect economic effects into the economic analysis (Table 1, Batch 46). Effects of hearing loss on employment and productivity were considered in 21% of studies (n = 24; Table 1, Batch 47), education costs in 20% (n = 23; Table 1, Batch 48), caregiver or family effects in 11% (n = 13; Table 1, Batch 49), and transportation costs in 9% (n = 11; Table 1, Batch 50).

3.7. Quality of included studies

Median quality rating of all included studies was 92, IQR [[72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98], [99], [100]], and the mean was 83, standard deviation (SD)=20. When only studies published since 2010 were included, the median quality score increased slightly to 94, IQR [[79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98], [99], [100]] and the mean increased to 87, SD=17. When only studies published since 2000 were included, the median quality score was 94, IQR [79–100], and the mean was 86, SD=18. The most frequent reasons we applied quality deductions were failure to assess interventions incrementally (i.e. failing to compare each studied intervention's costs and benefits to the next most effective intervention after eliminating dominated options. Interventions are considered dominated if they are more costly but less effective than an alternative (strong dominance), or when a combination of two interventions is better than a third intervention (weak or extended dominance); n = 29, 25%; Table 1, Batch 51), absence of statement of perspective of analysis (i.e., healthcare payer perspective, societal perspective, etc.; n = 25, 21%; Table 1, Batch 52), absence of explicit consideration of biases (n = 33, 28%; Table 1, Batch 53), and lack of model structure transparency and justification (n = 34, 29%; Table 1 Batch 54) (Fig. 2). Forty-nine studies (42%) had two or more major methodologic or reporting deficits (Table 1, Batch 55). Please see Appendix 11 for a breakdown of quality scores in each intervention category.

3.8. Modeling methods

Almost all of the identified decision models used sensitivity analysis to characterize uncertainty in their model-based results (n = 109, 93%; Table 1, Batch 56). The methods used included one-way deterministic (n = 97, 83%; Table 1; Batch 57), multi-way deterministic (n = 31, 26%; Table 1, Batch 58), and probabilistic sensitivity analysis (n = 49, 42%; Table 1, Batch 59). The proportion of studies that included probabilistic sensitivity analyses increased to 58% when only studies published since 2010 were analyzed. We found that 15% of analyses (n = 17) explicitly reported validation exercises in their methods or results sections (Table 1; Batch 60). Seven studies reported face validity (Table 1, Batch 61), seven reported external (or “predictive”) validation exercises (Table 1, Batch 62), and three reported internal validation exercises (Table 1, Batch 63). The proportion of studies that reported any validation efforts did not change when only studies published since 2010 were evaluated.

4. Discussion

This systematic review identified a large body of literature that explores the economic efficiency of interventions in hearing healthcare. The most frequently examined interventions were related to prevention of hearing loss from infectious causes, i.e., vaccination studies; detection of hearing loss through screening strategies; and treatment of hearing loss, including cochlear implantation and hearing aid provision. These interventions were most frequently examined in high-income settings [2].

The median quality score of included studies was high and we found that more recent studies had slightly higher quality than earlier studies. However, almost half of all included studies had two or more major methodologic or reporting deficits. Some studies did not compare alternative interventions incrementally, rather compared multiple interventions to a set best practice or current standard of care. While this approach might be helpful for policymakers in some circumstances, a formal cost-effectiveness analysis should compare all studied intervention alternatives incrementally to identify the intervention that maximizes expected benefit for its cost. Incremental comparison is recommended by cost-effectiveness guidelines and failing to compare incrementally can affect the validity of cost-effectiveness conclusions and subsequent policy recommendations [150]. Sensitivity analysis is a crucial component of decision analysis and almost all included studies incorporated sensitivity analysis of some form, with a higher proportion of studies published after 2010 including probabilistic sensitivity analysis. That said, model validation exercises were not reported in over 80% of studies, and this proportion did differ between more recently published studies and earlier studies. Including validation exercises in model-based analyses follows modeling best-practice guidelines and can increase the transparency and applicability of the results [12,150].

The data synthesis and analysis in the systematic review reveal several evidence gaps. First, despite over 80% of the global burden of hearing loss lying in LMIC, the vast majority of the included studies (82%) were conducted in a high-income setting. This is of particular importance as health policy decisions in LMIC are increasingly made based on prioritization approaches such as health technology assessments that include cost-effectiveness analyses. Additionally, the lack of studies in LMIC reveals that disproportionately lower efforts and resources are being invested to identify solutions to the hearing healthcare problems in regions of the world where the burden of hearing loss is highest. The reason for this dearth of evidence in LMIC may be due to relatively sparse setting-specific clinical or economic data or to workforce shortages of hearing health professionals [2]. Future decision analyses that seek to alleviate the global burden of hearing loss should evaluate hearing interventions in LMIC. Decision scientists may partner with local hearing health researchers and clinicians to collect data to inform model developments and the parameters selected for the models. Indeed, decision models are particularly useful in settings where data are sparse or highly variable.

Nearly all decision models included in this review evaluated a single intervention or a set of interventions aimed at a single etiology of hearing loss. Out of all included studies, we identified two studies performed by the same lead author that directly compared the cost-effectiveness of interventions targeting hearing loss prevention and treatment from multiple etiologies and across the lifespan [115,116]. These studies considered child and adult screening strategies, antibiotic administration for meningitis-associated hearing loss, and antibiotics or aural toilet for chronic otitis media. When considering optimal resource allocation in conditions of scarcity, policymakers and finance ministers will benefit from analyses and models that compare interventions targeting hearing loss across etiologies and the lifespan. Future research should explore how a decision model that considers numerous etiologies of hearing loss from beginning to end of life might provide such information.

Health economic analyses traditionally report clinical outcomes in terms of QALYs or DALYs to allow for comparison of value across multiple conditions. The majority of decision models we identified did report health outcomes in QALYs or DALYs; however, there was no uniform source for utility values used to calculate QALYs and DALYs. Over one quarter of studies reporting QALYs or DALYs used their own methods to determine utility values of decision model health states. This variability highlights the high degree of uncertainty around this model input, and the lack of a definitive source for parameterizing model-based utility values. While utility values should be specific to the population under study, common approaches to incorporating utility values of hearing health states in decision models may provide consistency and comparability between studies. Future research might explore the creation of appropriate and well-developed utility values of hearing loss – that also bear the appropriate study populations in mind – to inform decision models and reduce this model input uncertainty.

We also identified an evidence gap in inclusion of the indirect economic effects of hearing loss. Around one third of included studies incorporated indirect economic effects into their cost-effectiveness analysis as recommended by the Second Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine [150]. Exclusion of the effects of hearing loss on economic productivity, education, and social support may underestimate the true economic burden of hearing loss and the potential for amelioration of the burden. Emerging evidence that associates hearing loss with cognitive decline and other medical comorbidities may further increase the indirect economic effects associated with hearing loss, such as caregiver and family burden [151]. There is a need for high-quality estimates of the impact of hearing loss on indirect economic outcomes that can be incorporated into decision modeling analyses.