Abstract

The effects of acotiamide on gastrointestinal motility have not been sufficiently investigated. The aim of this study was to determine whether single preprandial acotiamide or mosapride intake might affect the gastric emptying rate using the 13C breath test. Here, 11 healthy volunteers participated in a randomized three-way crossover study. The subjects received acotiamide (100 mg) or mosapride (5 mg) or placebo before liquid test meal ingestion. Gastric emptying was estimated by determining following parameters: the time required for 50% emptying of the labeled meal (T1/2), lag time for 10% emptying of the labeled meal (Tlag), gastric emptying coefficient (GEC) and regression-estimated constants (β and κ). These parameters were calculated from a 13CO2 breath excretion curve using conventional formulas. The acotiamide, mosapride and placebo conditions were compared, revealing that for gastric emptying rates (values expressed as median), T1/2 (87.83571 min vs 79.95057 min vs 88.74378 min, p = 0.1496), Tlag (46.36449 min vs 42.2897 min vs 47.08094 min, p = 0.4966), GEC (4.382027 vs 4.211441 vs 4.248495, p = 0.8858), β (1.917728 vs 1.757062 vs 1.869141, p = 0.4066) and κ (0.834051 vs 0.819820 vs 0.789523, p = 0.1225) did not significantly differ. In this study, acotiamide (100 mg) or mosapride (5 mg) had no effect on gastric emptying.

Keywords: acotiamide, mosapride, breath test, gastric emptying

Introduction

Although functional dyspepsia (FD) is not a serious disease associated with life prognosis, it is known that symptoms may persist chronically or intermittently, significantly reducing patients’ quality of life (QOL). In Japan, acotiamide, which is only indicated for FD, has been reported to improve the symptoms of patients.(1–3)

Acotiamide has acetylcholinesterase and M1/M2 muscarinic receptor inhibitory activities and is thought to improve dyspepsia symptoms and QOL by improving gastric dysfunction. Phase II and III trials have been conducted in Europe and Japan and have been shown acotiamide to be effective in postprandial distress syndrome (PDS).(1–3) Only acotiamide has been shown to be stable and effective in placebo-controlled double-blind studies in patients with FD. For other drugs, clinical trial results with high evidence levels showing effectiveness in patients with FD have not been obtained.(4)

However, little is known about how acotiamide improves gastric dysfunction. The effect of acotiamide on gastric emptying varies from report to report, as there are reports that there is no effect on gastric emptying and reports that it promotes gastric emptying.(5–7)

The gastrointestinal motility effects of acotiamide have not yet been sufficiently investigated. The aim of this study was to determine whether single preprandial acotiamide intake might have an effect on the rate of liquid gastric emptying using the 13C breath test.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

In this study, the subjects included 11 asymptomatic male and female volunteers (F/M 3/8; age 20–42 years). All were nonsmokers, and no subjects had a previous history of gastrointestinal disease or abdominal surgery. None of the subjects were taking any routine medication at the time of the study.

13C breath test

In the liquid meal experiments, the 11 subjects participated in a randomized, three-way crossover study. After they had fasted overnight (at least 8 h), the subjects received 100 mg of acotiamide or 5 mg of mosapride or placebo before ingesting a liquid test meal in a random sequence.

The test meal consisted of 200 kcal per 200 ml liquid meal (Racol with milk flavor, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) containing 100 mg of 13C-acetic acid (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc., Andover, MA),(8–10) and the subjects were asked to consume the meal within 5 min.

Gastric emptying was measured using the 13C-acetic acid breath test while the subjects were seated. Breath samples were collected in air bags at baseline (before the test meal) and at 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 75, 90, 105, 120, 135, and 150 min after the test meal was ingested.(11,12) The 13CO2/12CO2 ratio in the collected breath samples was determined to compare to the baseline sample using nondispersive infrared spectrophotometry (POCone, Otsuka Electronics Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan).

Data analysis

The results were converted to percent 13CO2 recovered in the expired air per hour (percent dose per hour) and to the cumulative percent of 13CO2 recovered based on the subject’s default production of 300 mmol CO2 per m2 body surface per hour.

Using the method reported by Ghoos et al.,(13) the percent 13CO2 recovery in the expired air per hour (percent dose per hour) against time was fit with the formula y(t) = atbe−ct by nonlinear regression analysis, where y is the percent 13C excretion in the expired air per hour, t is the time in hours, and a, b, and c are constants. The time course of cumulative 13CO2 recovery in the expired air was fit with another formula, z(t) = m(1 − e−kt)β, where z is the cumulative percent 13C excretion in the expired air and an integral of y(t), m is the cumulative 13CO2 recovery at an infinite time, and β and κ are regression-estimated constants. β and κ were determined using the mathematical curve-fitting technique. A larger β indicates slower emptying in the early phase, a larger κ indicates faster emptying in the late phase, and vice versa. The time required for 50% emptying of the labeled meal (T1/2), the analog to the scintigraphy lag time for 10% emptying of the labeled meal (Tlag) and the gastric emptying coefficient (GEC) were calculated as overall measures of gastric emptying: T1/2 = −[ln(1 − 2−1/β)]/κ, Tlag = (lnβ)/κ, and GEC = ln(a).(4–6) These parameters were calculated using the Solver procedure in Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis

In the liquid meal study, statistical evaluation was performed using the Friedman test and Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test. The level of significance was set at a p value <0.05. All the statistical analyses were performed with EZR (Saitama Medical Centre, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), which is a graphical user interface for R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). More precisely, it is a modified version of the R commander designed to add statistical functions that are frequently used in biostatistics.(14)

Ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to study initiation, written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study protocol using the 13C-acetic acid breath test was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Yokohama City University School of Medicine (A130725009). This study was conducted as part of a clinical trial enrolled as UMIN000010966.

Results

The liquid meal study was completed in all 11 subjects, and no adverse events occurred during the study. The results obtained for the three conditions regarding the breath test parameters are summarized in Table 1. All data are expressed as medians and ranges. No significant differences were observed for T1/2 [(87.83571: 70.69122–103.9367 min) vs (79.95057: 74.07966–99.05346 min) vs (88.74378: 78.13759–104.9147 min), p = 0.1496; median: range, acotiamide vs mosapride vs placebo], Tlag [(46.36449: 35.47682–63.0211 min) vs (42.2897: 30.7577–67.03682 min), vs (47.08094: 40.86219–60.12731 min), p = 0.4966; median: range, acotiamide vs mosapride vs placebo], GEC [(4.382027: 3.912023–4.499810) vs (4.211441: 3.942050–4.489715), vs (4.248495: 4.094345–4.442651), p = 0.8858; median: range, acotiamide vs mosapride vs placebo], β [(1.917728: 1.572550–2.240398) vs (1.757062: 1.515265–3.064374), vs (1.869141: 1.676357–2.184435), p = 0.4066; median: range, acotiamide vs mosapride vs placebo] or κ [(0.834051: 0.690610–0.960832) vs (0.819820: 0.630320–1.002294), vs (0.789523: 0.712032–0.887127), p = 0.1225; median: range, acotiamide vs mosapride vs placebo] among the acotiamide group, the mosapride group and the placebo group.

Table 1.

Comparison of breath test parameters among the acotiamide group, the mosapride group and the placebo group for the liquid meal test

| Parameter | Acotiamide | Mosapride | Placebo | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tlag (min) | 46.36449 (35.47682–63.0211) | 42.2897 (30.7577–67.03682) | 47.08094 (40.86219–60.12731) | 0.4966 |

| T1/2 (min) | 87.83571 (70.69122–103.9367) | 79.95057 (74.07966–99.05346) | 88.74378 (78.13759–104.9147) | 0.1496 |

| GEC | 4.382027 (3.912023–4.499810) | 4.211441 (3.942050–4.489715) | 4.248495 (4.094345–4.442651) | 0.8858 |

| β | 1.917728 (1.572550–2.240398) | 1.757062 (1.515265–3.064374) | 1.869141 (1.676357–2.184435) | 0.4066 |

| κ | 0.834051 (0.690610–0.960832) | 0.819820 (0.630320–1.002294) | 0.789523 (0.712032–0.887127) | 0.1225 |

All values represent the median value (range). T1/2, time required for emptying of 50% of the labeled meal (min); Tlag, the analog to the scintigraphy lag time for 10% emptying of the labeled meal; GEC, gastric emptying coefficient; β and κ, regression-estimated constants.

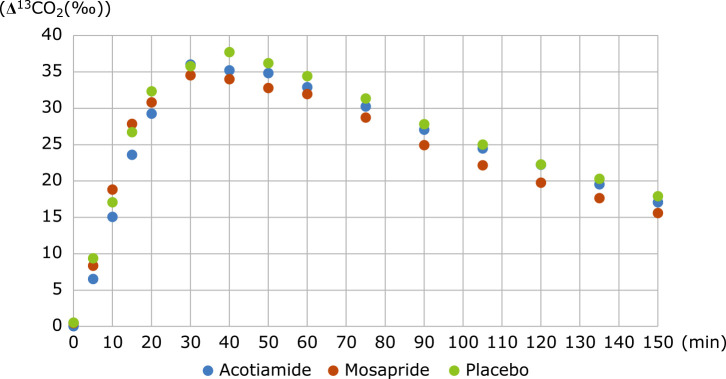

The data of mean time course changes in 13CO2 in the three groups are shown in Fig. 1. Figure 1 shows that no significant differences were visually apparent among the three groups.

Fig. 1.

Time course of Δ13CO2 (‰). Mean time course changes in 13CO2 in the acotiamide (blue), mosapride (red) and placebo (green). This figure reveals that no significant differences were detectable among the 3 groups.

Discussion

The present study was conducted to examine changes in the rate of gastric emptying after a single dose of preprandial acotiamide or mosapride before ingesting a liquid meal in healthy volunteers. The results of the liquid meal studies showed that 100 mg of acotiamide or 5 mg of mosapride had no effect on gastric emptying. The finding that acotiamide had no effect on the gastric emptying rate is consistent with the results reported by Zai et al.(5) and Masuy et al.(7)

The effects of commonly used drugs on gastric emptying in patients with functional gastrointestinal disease are summarized in Table 2.(5–7,15–20) In clinical settings, various drugs are used to treat dyspepsia in patients with functional gastrointestinal disease, but few drugs improve gastric emptying. Proton pump inhibitors, which are frequently used to treat dyspepsia in patients with functional gastrointestinal disease, delay gastric emptying.(19) The difference between healthy volunteers and patients with functional gastrointestinal disease is noteworthy. This study was conducted on healthy volunteers, and the results may be different in patients with functional gastrointestinal disease.

Table 2.

Effect of various drugs on gastric emptying

| Acotiamide | Mosapride | Rikkunshito | Itopride | PPI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zai et al.(5) | → (HV) | ||||

| Masuy et al.(7) | → (HV) | ||||

| Nakamura et al.(6) | ↑ (FD) | ||||

| Kusunoki et al.(21) | ↑ (HV) | ||||

| Sakamoto et al.(15) | ↑ (HV) | ||||

| Kusunoki et al.(16) | ↑ (FD) | ||||

| Nonaka et al.(17) | → (HV/FD) | ||||

| Abid et al.(18) | → (FD) | ||||

| Tougas et al.(19) | ↓ (HV) | ||||

| Nonaka et al.(20) | → (HV) |

→: No change. ↑: Acceleration. HV, healthy volunteer; FD, functional dyspepsia; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

Is there a delay in gastric emptying in patients with FD? Several reports suggest that gastric emptying is impaired in some patients with FD, and a meta-analysis indicates that gastric emptying is significantly delayed in almost 40% of patients with FD.(22) Most studies failed to find a convincing relationship between delayed gastric emptying and symptom patterns, and some studies reported rapid gastric emptying after meals in some patients with FD.(23,24)

There is overwhelming evidence that acotiamide reduces dyspepsia symptoms in patients with FD. However, it is difficult to explain the effect of acotiamide on patients with FD by gastric emptying alone. The reported effects of acotiamide on gastrointestinal function are summarized in Table 3.(5–7,25–27) Many reports indicate that acotiamide has no effect on gastrointestinal function. Current trackable gastrointestinal function tests may not be able to detect changes in gastrointestinal function caused by acotiamide.

Table 3.

Effects of acotiamide on gastrointestinal function

| Esophageal motor function |

LES pressure |

EGJ compliance |

Gastric emptying |

Gastric accommodation |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ishimura et al.(25) | → (HV) | ||||

| Zai et al.(5) | → (HV) | ||||

| Mikami et al.(26) | → (HV) → (GERD) | → (HV) → (GERD) | → (HV) → (GERD) | ||

| Nakamura et al.(6) | ↑ (FD) | ↑ (FD) | |||

| Masuy et al.(7) | → (HV) | ||||

| Funaki et al.(27) | ↑ (FD) |

→: No change. ↑: Acceleration. LES, lower esophageal sphincter; EGJ, esophagogastric junction; HV, healthy volunteer; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; FD, functional dyspepsia; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

The gastric emptying rate, as measured by the breath test, is affected by gastric accommodation, as measured by the barostat method, and by the outflow of gastric contents into the duodenum due to contraction of the gastric antrum. Sekino et al.(28) reported that improved gastric accommodation may lead to a reduction in gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with FD but it may also lead to a delay in gastric emptying, as measured by the breath test. Even if acotiamide promotes gastric antrum contraction, this effect may be counterbalanced by improved gastric accommodation, and the gastric emptying rate may remain unchanged.

Mosapride is a drug derived from cisapride. Cisapride was effective in treating dyspepsia symptoms in patients with FD but is no longer available due to arrhythmia side effects.(18) Mosapride is available in limited areas, and there is little evidence of its use in patients with FD. In our study, we found no effect on gastric emptying. There are two reports that show that gastric emptying is promoted in healthy subjects, one by Kusunoki et al.(21) using an ultrasonic method and the other by Sakamoto et al.(15) using a highly viscous test food. Differences in methods and test meals may have affected the results.

The present study had some limitations. First, the number of subjects was small. Second, the subjects were healthy volunteers who did not have any symptoms. If possible, we would like to perform the same study in patients with functional gastrointestinal disease and compare the results with those from healthy volunteers.

Our study findings revealed that single-dose acotiamide or mosapride intake had no significant influence on the rate of gastric emptying. The effect of acotiamide on dyspepsia symptoms in patients with FD was considered to be caused by a mechanism other than promotion of gastric emptying, for example, the amount of gastric acid secretion and acylated ghrelin level.(29,30)

Author Contributions

MK, MI, YI, and HI designed the study; MK, MI, MM, KF, AK, and AN performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by a research grant in part by Yokohama City University Fund for supporting basic research.

Abbreviations

- GEC

gastric emptying coefficient

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Tack J, Masclee A, Heading R, et al. A dose-ranging, placebo-controlled, pilot trial of Acotiamide in patients with functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2009; 21: 272–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsueda K, Hongo M, Tack J, Aoki H, Saito Y, Kato H. Clinical trial: dose-dependent therapeutic efficacy of acotiamide hydrochloride (Z-338) in patients with functional dyspepsia—100 mg t.i.d. is an optimal dosage. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010; 22: 618-e173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsueda K, Hongo M, Tack J, Saito Y, Kato H. A placebo-controlled trial of acotiamide for meal-related symptoms of functional dyspepsia. Gut 2012; 61: 821–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miwa H, Kusano M, Arisawa T, et al.; Japanese Society of Gastroenterology. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for functional dyspepsia. J Gastroenterol 2015; 50: 125–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zai H, Matsueda K, Kusano M, Urita Y, Saito Y, Kato H. Effect of acotiamide on gastric emptying in healthy adult humans. Eur J Clin Investig 2014; 44: 1215–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamura K, Tomita T, Oshima T, et al. A double-blind placebo controlled study of acotiamide hydrochloride for efficacy on gastrointestinal motility of patients with functional dyspepsia. J Gastroenterol 2017; 52: 602–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masuy I, Tack J, Verbeke K, Carbone F. Acotiamide affects antral motility, but has no effect on fundic motility, gastric emptying or symptom perception in healthy participants. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2019; 31: e13540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mossi S, Meyer-Wyss B, Beglinger C, et al. Gastric emptying of liquid meals measured noninvasively in humans with [13C]acetate breath test. Dig Dis Sci 1994; 39 (12 Suppl): 107S–109S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inamori M, Iida H, Endo H, et al. Aperitif effects on gastric emptying: a crossover study using continuous real-time 13C breath test (BreathID system). Dig Dis Sci 2009; 54: 816–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inamori M, Akiyama T, Akimoto K, et al. Early effects of peppermint oil on gastric emptying: a crossover study using a continuous real-time 13C breath test (BreathID system). J Gastroenterol 2007; 42: 539–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanoshima K, Matsuura M, Kaai M, et al. The α-glucosidase inhibitor voglibose stimulates delayed gastric emptying in healthy subjects: a crossover study with a 13C breath test. J Clin Biochem Nutr 2017; 60: 216–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nonaka T, Sekino Y, Iida H, et al. Early effect of single-dose sitagliptin administration on gastric emptying: crossover study using the 13C breath test. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2013; 19: 227–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghoos YF, Maes BD, Geypens BJ, et al. Measurement of gastric emptying rate of solids by means of a carbon-labeled octanoic acid breath test. Gastroenterology 1993; 104: 1640–1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant 2013; 48: 452–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakamoto Y, Sekino Y, Yamada E, et al. Mosapride accelerates the delayed gastric emptying of high-viscosity liquids: a crossover study using continuous real-time C breath test (BreathID system). J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011; 17: 395–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kusunoki H, Haruma K, Hata J, et al. Efficacy of rikkunshito, a traditional japanese medicine (Kampo), in treating functional dyspepsia. Intern Med 2010; 49: 2195–2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nonaka T, Kessoku T, Ogawa Y, et al. Does postprandial itopride intake affect the rate of gastric emptying? A crossover study using the continuous real time 13C breath test. Hepatogastroenterology 2011; 58: 224–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abid S, Jafri W, Zaman MU, Bilal R, Awan S, Abbas A. Itopride for gastric volume, gastric emptying and drinking capacity in functional dyspepsia. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2017; 8: 74–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tougas G, Earnest DL, Chen Y, Vanderkoy C, Rojavin M. Omeprazole delays gastric emptying in healthy volunteers: an effect prevented by tegaserod. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005; 22: 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nonaka T, Kessoku T, Ogawa Y, et al. Effects of histamine-2 receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors on the rate of gastric emptying: a crossover study using a continuous real-time C breath test (BreathID system). J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011; 17: 287–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kusunoki H, Haruma K, Hata J, et al. Efficacy of mosapride citrate in proximal gastric accommodation and gastrointestinal motility in healthy volunteers: a double-blind placebo-controlled ultrasonographic study. J Gastroenterol 2010; 45: 1228–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quartero AO, de Wit NJ, Lodder AC, Numans ME, Smout AJ, Hoes AW. Disturbed solid-phase gastric emptying in functional dyspepsia: a meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci 1998; 43: 2028–2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lunding JA, Tefera S, Helge Gilja O, et al. Rapid initial gastric emptying and hypersensitivity to gastric filling in functional dyspepsia: effects of duodenal lipids. Scandinavian J Gastroenterol 2006; 41: 1028–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kusano M, Zai H, Shimoyama Y, et al. Rapid gastric emptying, rather than delayed gastric emptying, might provoke functional dyspepsia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 26 Suppl 3: 75–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishimura N, Mori M, Mikami H, et al. Effects of acotiamide on esophageal motor function and gastroesophageal reflux in healthy volunteers. BMC Gastroenterol 2015; 15: 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mikami H, Ishimura N, Okada M, et al. Acotiamide has no effects on esophageal motor activity or esophagogastric junction compliance. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018; 24: 241–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Funaki Y, Ogasawara N, Kawamura Y, et al. Effects of acotiamide on functional dyspepsia patients with heartburn who failed proton pump inhibitor treatment in Japanese patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2019; 32: e13749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sekino Y, Yamada E, Sakai E, et al. Influence of sumatriptan on gastric accommodation and on antral contraction in healthy subjects assessed by ultrasonography. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2012; 24: 1083-e564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyamoto S, Tsuda M, Kato M, et al. Evaluation of gastric acid suppression with vonoprazan using calcium carbonate breath test. J Clin Biochem Nutr 2019; 64: 174–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agawa S, Futagami S, Yamawaki H, et al. Acylated ghrelin levels were associated with depressive status, physical quality of life, endoscopic findings based on Kyoto classification in Japan. J Clin Biochem Nutr 2019; 65: 65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]