Objective

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends the COVID-19 vaccine be offered to all pregnant women but states that the decision should be left to the woman after careful consideration of individual risk factors.1 Given the increased morbidity associated with COVID-19 in pregnancy, understanding pregnant women's perceptions of and attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy is vital to optimizing vaccine uptake. This study aimed to describe COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate among pregnant women.

Study design

This was a survey study given to pregnant women during their nuchal translucency or anatomic survey sonogram appointment at a single ultrasound unit from December 14, 2020, to January 14, 2021. Women were considered eligible for participation if they were ≥18 years old and spoke English. The survey was developed on the basis of the standards recommended by Kelley et al.2 There were 31 questions regarding sociodemographics, vaccination history, previous COVID-19 symptoms and diagnoses, attitudes toward vaccines in pregnancy, and beliefs about the COVID-19 vaccination specifically. A sample size of 590 participants was determined to be sufficient to produce a confidence interval (CI) of 95% with a 4% margin of error.3 To account for 10% of surveys being incomplete, our minimum sample size was 650 participants. The primary outcome was COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate. Univariate analyses were performed to estimate the effect of different variables on acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination and are reported as odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI. To better understand certain subpopulations’ vaccine acceptance rate, we performed crosswise analyses of a priori variables of interest (race, educational attainment, and influenza vaccine status). These factors were chosen on the basis of previous literature and their utility for public health messaging.4 , 5 All statistical analyses were performed using Stata (version 16.1; StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). This study was approved by the Weill Cornell Medicine Institutional Review Board for Human Participant Research (20-08022547).

Results

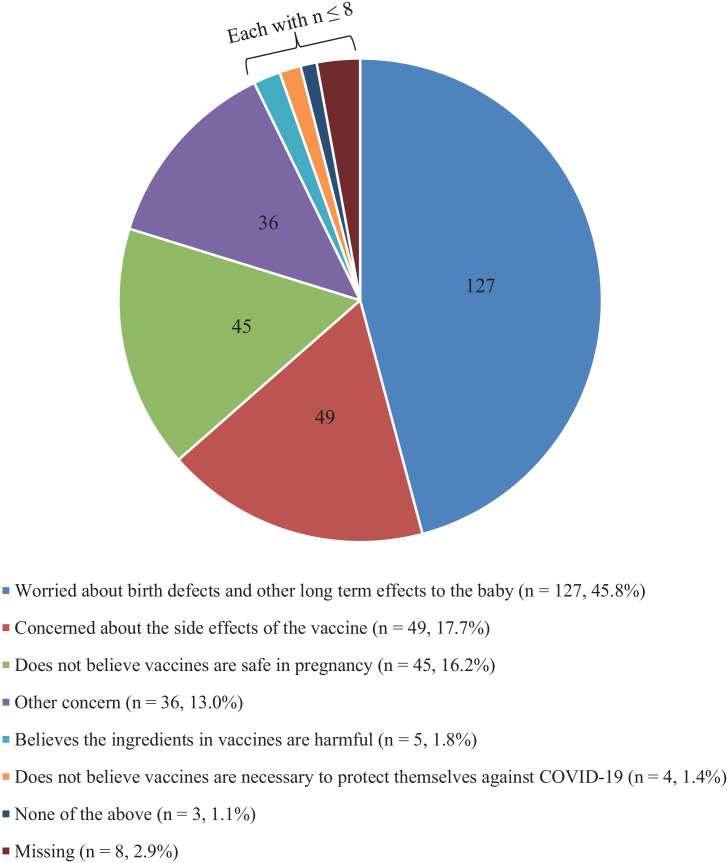

Of the 1002 eligible women approached, 662 (66.1%) completed the survey. All women completed the survey after emergency use authorization was granted to Pfizer-BioNTech (Pfizer, Inc, New York, NY; BioNTech SE, Mainz, Germany) messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine. Most women were more than 30 years old (82.9%), were White (62.7%), and had a bachelor's degree or above (87.7%). Furthermore, 77.9% of women reported having already been vaccinated against influenza during the 2020–2021 season; however, 38.5% of women reported declining vaccination at least once in the past 5 years. Overall, 381 of 653 women (58.3%; 95% CI, 54.5–62.2) would accept the COVID-19 vaccine while pregnant. Among the women who declined vaccination, the most common primary concern was risk to the fetus or neonate (45.8%), followed by vaccine side effects (17.7%) (Figure ). On univariate analyses, younger age, Black or African American race, Hispanic ethnicity, having less than a bachelor's degree, and declining the seasonal influenza vaccine were associated with nonacceptance of COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy (Table ). Trust in the information received about vaccinations was the strongest predictor of COVID-19 vaccination acceptance. On crosswise comparisons, educational status did not affect COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate among Black or African American women; however, among White women, lower education was associated with lower odds of vaccine acceptance (OR, 0.19; 95% CI, 0.05–0.53). In addition, among those who declined influenza vaccination in pregnancy, no Black or African American woman would accept COVID-19 vaccination, whereas 11 of 44 White women (25.0%) would accept the vaccine.

Figure.

Women's primary concern about COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy

Only women who said they would decline the COVID-19 vaccine were included (N=277). Additional options for declining COVID-19 vaccine (do not believe vaccines are necessary to protect their child against COVID-19 and concern about the cost of the vaccine) were omitted due to n=0.

Levy. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021.

Table.

Univariate analysis of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance by demographic data, vaccine history, and COVID-19 experience

| Predictor variable | N | Will accept the COVID-19 vaccine (%) | OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (y) | ||||

| 18–24 | 17 | 6 (35.3) | 0.35 (0.13–0.97)a | .04a |

| 25–30 | 94 | 47 (50.0) | 0.64 (0.40–1.02) | .06 |

| 31–35 | 304 | 185 (60.9) | Reference | NA |

| 36–40 | 179 | 112 (62.6) | 1.08 (0.74–1.57) | .71 |

| >40 | 58 | 31 (53.4) | 0.74 (0.42–1.30) | .29 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 405 | 266 (65.7) | Reference | NA |

| Black or African American | 49 | 9 (18.4) | 0.12 (0.06–0.25)a | <.001a |

| Asian | 117 | 69 (59.0) | 0.75 (0.49–1.15) | .18 |

| Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, American Indian, or Alaska Native | 5 | 3 (60.0) | 0.78 (0.13–4.75) | .79 |

| Other | 71 | 29 (40.9) | 0.36 (0.22–0.60)a | <.001a |

| Hispanic or Latina | 86 | 36 (41.9) | 0.47 (0.29–0.74)a | .001a |

| Location of birth | ||||

| North America (United States or Canada) | 483 | 284 (58.8) | Reference | NA |

| Central or South America | 16 | 8 (50.0) | 0.70 (0.26–1.90) | .48 |

| Europe | 54 | 33 (61.1) | 1.10 (0.62–1.96) | .74 |

| Africa | 3 | 1 (33.3) | 0.35 (0.03–3.89) | .39 |

| Asia or Australia | 75 | 44 (58.7) | 0.99 (0.61–1.63) | .98 |

| Other | 15 | 8 (53.3) | 0.80 (0.29–2.24) | .67 |

| Nulliparous | 356 | 225 (63.2) | 1.52 (1.10–2.08)a | .01a |

| Education level | ||||

| Some of high school, high school graduate (or equivalent), or associate's degree | 79 | 16 (20.3) | 0.14 (0.07–0.25)a | <.001a |

| Bachelor's degree | 237 | 154 (65.0) | Reference | NA |

| Master's degree | 224 | 138 (61.6) | 0.86 (0.59–1.26) | .45 |

| Doctoral degree | 104 | 69 (66.3) | 1.06 (0.65–1.73) | .81 |

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed full time (>20 h/wk) | 502 | 312 (62.2) | Reference | NA |

| Employed part time (<20 h/wk) | 57 | 24 (42.1) | 0.44 (0.25–0.7)a | .004a |

| Unemployed | 86 | 42 (48.8) | 0.58 (0.37–0.92)a | .02a |

| Vaccine history | ||||

| Influenza vaccine in 2020–2021 season | ||||

| Has already received the vaccine | 506 | 335 (66.2) | Reference | NA |

| Has not received the vaccine but plans to receive it | 60 | 29 (48.3) | 0.48 (0.28–0.82)a | .007a |

| Has not received the vaccine and does not plan on receiving it | 85 | 16 (18.8) | 0.12 (0.07–0.21)a | <.001a |

| Declined influenza vaccine in the past 5 y | 250 | 121 (48.4) | 0.52 (0.37–0.71)a | <.001a |

| Previously declined a recommended vaccine for their child | 14 | 3 (21.4) | 0.22 (0.06–0.80)a | .02a |

| COVID-19 history and perceived severity | ||||

| History of COVID-19 symptoms | 100 | 49 (49.0) | 0.64 (0.42–0.98)a | .04a |

| Tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in the past | 44 | 14 (31.8) | 0.30 (0.16–0.59)a | <.001a |

| Fear of COVID-19 in pregnancy | ||||

| Not fearful at all | 34 | 8 (23.5) | 0.20 (0.09–0.46)a | <.001a |

| Slightly fearful | 299 | 181 (60.5) | 1.01 (0.73–1.40) | .94 |

| Very fearful | 317 | 191 (60.3) | Reference | NA |

| Attitudes of pregnant women toward vaccines in generalb | ||||

| Vaccines are important to protect others in the community | 635 | 378 (59.5) | 8.82 (1.96–39.76) | .005 |

| Vaccines protect me from disease | 633 | 379 (59.9) | 11.94 (2.72–52.36) | .001 |

| I trust the information I receive about vaccines | 585 | 375 (64.1) | 30.95 (9.55–100.33) | <.001 |

| I am worried that vaccines cause birth defects and other long-term negative effects to the neonate | 294 | 122 (41.5) | 0.25 (0.18–0.35) | <.001 |

| I do not believe vaccines are safe in pregnancy | 170 | 46 (27.1) | 0.15 (0.10–0.22) | <.001 |

| There are too many side effects associated with vaccines | 89 | 19 (21.4) | 0.15 (0.09–0.25) | <.001 |

| The ingredients in vaccines are harmful | 59 | 12 (20.3) | 0.14 (0.07–0.28) | <.001 |

| Vaccines are not necessary to prevent spread of disease | 28 | 10 (35.7) | 0.36 (0.17–0.80) | .01 |

Data are presented as number (percentage), unless otherwise specified.

CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio.

Statistically significant results

Data presented are for those who agree with the statement.

Levy. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate of 58.4% was consistent with the acceptance of other recommended vaccines in pregnancy, such as influenza and tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis, and is associated with patient characteristics and previous vaccine history.4 , 5 In addition, we found that the impact of education and influenza vaccination history on vaccine acceptance varied depending on race. Our finding suggested the need for different public health messaging to improve COVID-19 vaccination acceptance. In other words, education about COVID-19 vaccine safety in pregnancy is important, but an alternative approach may be necessary among Black or African American women because of their lived experiences with systemic racism and mistrust in the healthcare system. In our study, the primary concern of pregnant women about COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy was safety, with nearly half declining vaccination for this reason. A parallel goal of ongoing vaccination trials in pregnant women must focus on short- and long-term safety data from vaccination in pregnancy. Limitations of the study include enrollment of women in the first half of pregnancy and the sociodemographics of our population, which limits generalizability to other more vulnerable populations and women in the third trimester of pregnancy. In addition, our study described the vaccine acceptance rate around the time that the mRNA vaccines were introduced. Given that the primary concern about vaccination was safety, this acceptance rate may change over time as more data are accrued. Vaccination against COVID-19 in pregnancy is vital to controlling disease burden and decreasing morbidity in pregnancy. The results of our study underscored the importance of understanding women's perspectives on novel interventions in pregnancy, such as with COVID-19 vaccination, to guide public health and research efforts.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

The authors did not receive financial support for this study.

References

- 1.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . 2020. Vaccinating pregnant and lactating patients against COVID-19.https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2020/12/vaccinating-pregnant-and-lactating-patients-against-covid-19# Available at: Accessed January 15, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelley K, Clark B, Brown V, Sitzia J. Good practice in the conduct and reporting of survey research. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15:261–266. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzg031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartlett JE, Kotrlik JW, Higgins CC. Organizational research: determining appropriate sample size in survey research. Inf Technol J. 2001;19:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldfarb I, Panda B, Wylie B, Riley L. Uptake of influenza vaccine in pregnant women during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:S112–S115. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Razzaghi H, Kahn KE, Black CL, et al. Influenza and Tdap vaccination coverage among pregnant women—United States, April 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1391–1397. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6939a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]