Abstract

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated many social conditions associated with violence. The objective of this systematic review was to examine trends in hospital reported violent trauma associated with the pandemic.

Methods

Databases were searched in using terms “trauma” or “violence” and “COVID-19,” yielding 4,473 records (2,194 de-duplicated). Exclusion criteria included non-hospital based studies and studies not reporting on violent trauma. 44 studies were included in the final review.

Results

Most studies reported no change in violent trauma incidence. Studies predominately assessed trends with violent trauma as a proportion of all trauma. All studies demonstrating an increase in violent trauma were located in the United States.

Conclusions

A disproportionate rise in violence has been reported within the US. However, most studies examined violent trauma as a proportion of all trauma; results may reflect relative changes from lockdowns. Future studies should examine rates of violent trauma to provide additional context.

Keywords: Violence, Trauma, COVID-19, Systematic review

The Sars-Cov-2 virus has had a tremendous impact upon every healthcare system and society in the world since its discovery in the human population in December 2019.1 The virus has since pervaded countries throughout the world, with ubiquitous impacts upon known social determinants of health, including financial insecurity, housing instability, and employment.2, 3, 4 In addition to these stressors, lockdowns and social distancing mandates have contributed to a general worsening of population-level mental health.5 Overall, these impacts, in addition to direct viral morbidity and mortality, have disproportionately impacted low-income communities.6 , 7 Inequities in many of these same social factors are also associated with violent trauma.8 Violence-related trauma has been associated with several community-level and individual factors, including education and employment opportunities, neighborhood level of social disadvantage, financial insecurity, proximity of liquor stores, and social isolation.9 , 10 To this end, many interventions to prevent violent trauma recidivism address these social factors.11

The World Health Organization reported in 2010 that trauma deaths total over 5.8 million annually, or approximately 10% of the annual deaths worldwide.12 Of these, approximately one in three are violence-related.12 These deaths are disproportionately experienced among individuals living in lower income communities. Simultaneously in 2020, these same communities experienced a disproportionate burden of COVID-19 cases,7 , 13 including of the 1.7 million total deaths worldwide.14

The COVID-19 pandemic constitutes a potential increase in the pre-disposing factors underlying the increase of violence, as well as a reduction in traditional mitigating factors and social supports. Given the increased expectations of social distancing and potential for exacerbation of social isolation, a factor known to be associated with violent trauma incidence,9 , 15 , 16 it was expected that the COVID-19 pandemic and violence epidemic would converge. The objective of this study was to systematically review the literature in order to explore trends in community violence over the past year.

Materials and methods

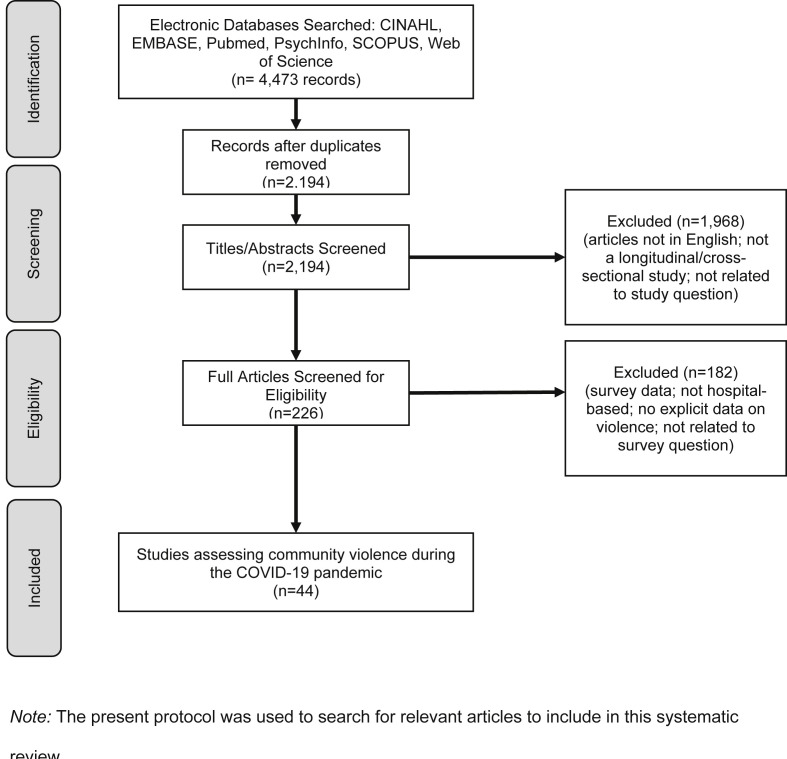

Search terms included: “COVID” and (“Trauma” OR “Violence”). The following databases were searched on December 7, 2020: CINHAL, EMBASE, PubMed, PsychInfo, Scopus, and Web of Science, yielding a total of 4,473 records. No date limit was applied to these searches. Removal of overlapping records yielded a total of 2,194 records, for which the titles and abstracts were screened independently by two authors (KB and EH). Exclusion criteria consisted of articles not written in English, articles which did not assess violence rates, case reports, commentaries, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and unpublished work (i.e., gray literature). Records which were not excluded by both reviewers were retained for full article review. A total of 226 records were then reviewed for inclusion by two authors (KB and EH). Records were removed based on the previous criteria. In order to limit the participant selection bias that may have occurred among population-based surveys, records were excluded if data were not reported based on hospital electronic health records or trauma registries. A total of 44 records were included in the final analysis. See Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Process of Article Selection for Inclusion

Note: The present protocol was used to search for relevant articles to include in this systematic review.

Records were analyzed using a pre-developed spreadsheet to capture data on department of analysis, method of statistical assessment (proportion versus rate data, wherein proportion refers to the proportion of violent trauma relative to all trauma cases, versus rate of violent trauma cases per week/month/year data), direction of statistical change in trauma data (increase, decrease, no change, or not assessed), percentages/rates of violent trauma during the study and reference periods, p-value of significance (significance level was considered with α < 0.05), study and reference time periods, duration of study time period, study location, patient population status (urban or rural), and study population (all patients, adults, or pediatric cases). Statistical assessments were only included if the authors explicitly examined changes in violence incidence between the study and reference periods. Therefore, p-values calculated for chi-square tests for change in all mechanisms of injury were not included, unless follow up testing with Bonferroni corrections were applied. The study's specific definition of violent trauma was also captured (e.g., domestic violence, assaults, stab wounds, etc.). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed (see supplementary information).

Results

Of the 44 records included in this study, only 28 included an assessment of the change in proportion or rate of community violence incidence during the COVID-19 pandemic to date. Of these, half noted no change as compared to pre-pandemic times (n = 14). The majority of studies (n = 34) included were based out of hospitals located in high-income countries (defined by the World Bank). Eight studies noted an increase, ranging from an increase of 0.6% (1.1%–1.6%)17 to more than 30% (Gosangi et al.: 12%–42%; Diamond et al.: 13%–47%)18 , 19 while six noted a decrease in violent trauma, ranging from a decrease of 1% (2%–1%)20 to 10% (23%–13%).21 An additional 15 studies provided data on the proportion or rate of violent trauma but did not explicitly analyze these changes statistically. Study duration ranged from 1 week to approximately 6 months (7–181 days), with an average length of 53 days. In addition to the overall outcome of changes in violent trauma incidence, studies were stratified and assessed according to department, method of analysis, location, and study duration (See Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Shows information on all of the studies included in this systematic review.

| Authors | Department | Statistical Change in Trauma Incidence of Violent Trauma | Study Location | Method of Statistical Assessment | Study Period % (n) | Reference Period % (n) | P value | Study Time Period | COVID-Related Restrictions during Study Period | Duration (Days) | Urban or Rural | Study-specific definition of violence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diamond, Lundy, Weber et al. | Hand Surgery | Increase | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA and Irvine, California, USA | Proportion | 47% (n = 16) | 13% (n = 31) | p = 0.001 | March 19 - April 3, 2020 vs. March 11 - March 18, 2020 | Regional Lockdowns: March 19 (Pennsylvania) & March 24 (California) | 15 | Urban | "High risk behaviors:" lawlessness, assault, high-speed vehicular chase |

| Abdallah, Zhao, Kaufman et al. | All | Increase | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA | Proportion | 30.8% (n = 148) | 1.6% (n = 6) | p = 0.006 | February 1 - May 30, 2020 vs. same period 2015–2019 | Regional Lockdown: March 16 | 119 | Urban | Intentional/Violent Trauma |

| Yeung, Brandsma, Karst, et al. | Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery | Not Assessed | London, UK | Proportion | 23.4% (n = 17) | 22.9% (n = 44) | N/A | March 23 - May 3, 2020 vs. same period in 2019 | National Lockdown March 23 | 41 | Urban | Interpersonal Violence |

| Lara-Reyna, Yaeger, Rossitto, et al. | Neurosurgery | Not Assessed | New York, New York, USA | N/A | 12.2% (n = 6) | 9.9% (n = 10) | N/A | March 1 - April 26, 2020 vs. November 1, 2019–February 29, 2020 | Regional Lockdown: March 12 | 56 | Urban | Violence-related injuries |

| Régas, Bellemère, Lamon, et al. | Hand Surgery | Not Assessed | Nantes, France | N/A | 0.9% (n = 175) | N/A | N/A | March 17 - May 10, 2020 | National Lockdown: March 17 | 54 | Urban | Violence-related hand injuries |

| Matthay, Kornblith, Matthay, et al. | All | No Change | San Francisco, California, USA | Rate | Weekly Activations as Mean (SD): Stab Wounds 5.0 (1.9), Blunt Assaults: 3.4 (2.3), GSW 3.1 (1.8) | Weekly Activations as Mean (SD): Stab Wounds 4.6 (2.2), Blunt Assaults: 3.6 (1.8), GSW 2.2 (1.6) | Stab Wounds: p = 0.60, Blunt Assaults: p = 0.79, GSW: p = 0.10 | January 1 - June 30, 2020 vs. same period 2015–2019 | Regional Lockdown: March 17 | 181 | Urban | Assaults and Self-harm |

| Dolci, Marongiu, Leinardi, et al. | Orthopedic and Trauma Surgery Departments | Decrease | Italy, Cagliari | Proportion | 1% (n = 5) | 2% (n = 38) | p = 0.01 | March 10 - May 3, 2020 vs. same period 2019 | National Lockdown: March 9 | 54 | Urban | Aggresssions |

| Pichard, Kopel, Lejeune, et al. | Hand Surgery | No Change | Paris, France | Proportion | 7.2% (n = 18) | 4.5% (n = 33) | p = 0.097 | March 17 - May 10, 2020 vs. same period 2019 | National Lockdown: March 17 | 54 | Urban | Aggresssions |

| Saponaro, Gasparini, Pelo, et al. | Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery | Not Assessed | Rome, Italy | N/A | 18.8% (n = 6) | 16.9% (n = 24) | N/A | March 1 - April 30, 2020 vs. same period 2019 | National Lockdown: March 9 | 60 | Urban | Aggresssions |

| Druel, Andeol, Rongieras, et al. | All | No Change | Lyon, France | Proportion | 3.2% (n = 2) containment period, 4.9% (n = 8) pre-containment | 5.4% (n = 28) | p > 0.05 Pre-containment vs. Containment; p > 0.05 Containment vs. 2019 | March 1 - 16, 2020 (Pre-containment) vs. March 17 - April 17, 2020 (Containment) vs. March 1 - April 17, 2019 | National Lockdown: March 17 | 31 | Urban | Altercations (incl. domestic violence and police-related incidents) |

| Atia, Pocnetz, Selby, et al. | Hand Surgery | Not Assessed | Derby, UK | Proportion | 7.0% (n = 5) | 4.0% (n = 5) | N/A | March 24 - April 17, 2020 vs. April 18 - May 10, 2020 | National Lockdown: March 27 | 24 | Urban | Assault/Punch |

| Hampton, Clark, Baxter, et al. | All | No Change | Rotherham, UK | Proportion | 10.0% (n = 5) | 2019: 14.6% (n = 19), Pre-Lockdown: 19.2% (n = 19) | p > 0.05 | March 10 - 23, 2020 (Pre-Lockdown) vs. March 24-April 7, 2020 (Lockdown) vs. March 24- April 7, 2019 | National Lockdown: March 27 | 13 | Urban | Assault/Punch/Violence |

| MacDonald, Neilly, Davies, et al. | All | No Change | Multiple Sites in Scottland: Glasgow, Aberdeen, Ninewells, Dundee, and Iverness, Scottland | Proportion | 2.5% (n = 33) | 2.8% (n = 48, 2018), 3.4% (n = 61, 2019) | p = 0.15 (2020 vs. 2019); p = 0.62 (2020 vs 2018) | March 23 - May 28, 2020 vs. 2018–2019 | National Lockdown: March 23 | 66 | Urban | Assault/Violence |

| Salzano, Dell'Aversana Orabona, Audino, et al. | Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery | Decrease | 6 Centers in Italy: Naples, Milan, Verona, Catanzaro, Rome, Sassari | Proportion | 13.7% (n = 10) | 22.9% (n = 54) | p = 0.10 | February 23 - May 23, 2020 vs. same period 2019 | National Lockdown: March 9 | 90 | Urban | Assault |

| Harris, Ellis, Gorman, et al. | All | Decrease | Adelaide, Australia | Proportion | 4% (n = 7) | 6% (n = 15) | p = 0.04 | March 23 - May 10, 2020 vs. February 3 - March 22, 2020 | Regional Lockdown: March 23 | 61 | Urban | Assault |

| Rhodes, Petersen, & Biswas | All | No Change | Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, USA | Proportion | 7.28% (n = 57) | 4.95% (n = 50) | p = 0.38 | January 1 - May 1, 2020 vs. same period 2019 | Regional Lockdown: April 8 | 121 | Urban | Assault |

| Jacob, Mwagiru, Thakur, et al. | All | No Change | Sydney, Australia | Rate | Monthly Mean (SD): 17 (2.1) | Monthly Mean (SD): 2016: 20 (2.1), 2017: 16 (4.2), 2018: 17 (4.2), 2019: 13 (2.1) | p > 0.05 | March 1 - April 30, 2020 vs. same period 2016–2019 | National Social Distancing: March 15; National Lockdown: March 29 | 60 | Urban | Assault |

| Fahy, Moore, Kelly, et al. | Radiology | No Change | Dublin, Ireland | Proportion | 3% (n = 4) | 4% (n = 7) | p > 0.05 | March 27 - April 27, 2020 vs. same period 2019 | National Lockdown: March 27 | 31 | Urban | Assault |

| Zsilavecz, Wain, Bruce, et al. | All | No Change | Pietermaritzburg, Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa | Proportion | 14.9% (n = 23) | 15.9% (n = 181) | p = 0.68 | March 23 - May 31, 2020 vs. same period in 2015–2019 | National Lockdown: March 23 | 69 | Urban | Assault |

| Vishal, Prakash, Rohit, et al. | Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery | No Change | Ranchi, India | Proportion | 18.6% (n = 11) | 4.1% (n = 9) | p = 0.298 | March 24 - June 30, 2020 vs. same period 2019 | National Lockdown: March 25 | 98 | Urban | Assault |

| Ajayi, Trompeter, Arnander et al. | All | Not Assessed | London, UK | N/A | 5.9% (n = 14) | 7.4% (n = 31) | N/A | March 6 - April 14, 2020 vs. January 26 - March 5, 2020 | National Social Distancing Mandates: March 23 | 40 | Urban | Assault |

| de Boutray, Kün-Darbois, Sigaux, et al. | Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery | Not Assessed | Multiple Sites in France: Paris, Toulouse, Marseille, Nantes, Montepellier, Strasbourg, Amiens, Nice, Perpi, Angers, Nimes, Clermont, Caen | N/A | 39.6% (n = 42) | N/A | N/A | March 16 - April 15, 2020 | National Lockdown: March 16 | 30 | Urban | Assault |

| Gumina, Proietti, Polizzotti, et al. | Orthopedic Surgery | Not Assessed | Italy, Rome | N/A | n = 1 | n = 2 | N/A | March 8 - April 8, 2020 vs. same period 2019 | National Lockdown: March 8 | 31 | Urban | Assault |

| Rathore, Kalia, Gupta, et al. | All | Not Assessed | Mandi, India | N/A | 1.8% (n = 3) | 0% (n = 0) | N/A | March 25 – May 3, 2020 vs. same period 2019 | National Lockdown: March 25 | 39 | Rural | Assault |

| Dhillon, Kumar, Saini, et al. | All | Not Assessed | Chandigarh, India | N/A | 5.0% (n = 5) | 1.4% (n = 5) | N/A | March 25 – May 3, 2020 vs. same period 2019 | National Lockdown: March 25 | 39 | Urban | Assault |

| Bhat & Kamath | All | Not Assessed | Manipal, India | Proportion | 0.42% (n = 1) | 1.5% (n = 9) | N/A | March 22 - May 17, 2020 vs. same period 2019 | National Lockdown: March 25 (Ordered on March 22) | 56 | Rural | Assault |

| Morris, Rogers, Kissmer, et al. | All | Decrease | Pietermaritzburg, Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa | Rate | Assault: n = 197; GSW: n = 3 | Assault: 2018: n = 397, 2019: n = 426; GSW: 2018: n = 32 2019: n = 20 | Assault: p < 0.05, GSW: p < 0.05 | April 1 - 30, 2020 vs. same period 2018–2019 | National Lockdown: March 27 | 30 | Urban | Assault/GSW |

| Figueroa, Boddu, Kader, et al. | Neurosurgery | Increase | Miami, Florida, USA | Proportion | 15% | 3% | p = 0.034 | March 1 - April 30, 2020 vs. same period 2016–2019 | Regional Bar/Restaurant Closure: March 17; Regional Lockdown: April 1 | 60 | Urban | Assault/GSW |

| Hashmi, Zahid, Ali, et al. | Orthopedic Surgery | Not Assessed | Karachi, Pakistan | N/A | 6.2% (n = 5) | 3.0% (n = 4) | N/A | March 16 - April 30, 2020 vs. February 1 - March 15, 2020 | National Lockdown: March 15 | 45 | Urban | Assault/GSW |

| Lubbe, Miller, Roehr, et al. | Orthopedic Surgery | Increase | Las Vegas, Nevada, USA | Proportion | GSW: 8.4% (n = 28), Assault: 1.2% (n = 4), Stab Wounds: 0.6% (n = 2) | GSW: 2018: 3.9% (n = 14), 2019: 3.8% (n = 16), Assault: 2018: 2.5% (n = 9), 2019: 3.1% (n = 13), Stab Wounds: 2018: 0% (n = 0), 2019: 0.2% (n = 1) | GSW: p = 0.0008, Assault: p > 0.05, Stab Wounds: p > 0.05 | March 17 - April 30, 2020 vs. same period 2018–2019 | Regional Lockdowns: March 17 | 44 | Urban | Assault/GSW/Stab Wounds |

| Leichtle, Rodas, Procter, et al. | All | No Change | Richmond, Virginia, USA | Proportion | 12.6% (n = 26) | 17.6% (n = 130) | p = 0.09 | March 17 - April 30, 2020 vs. March 1 - 16, 2020 | Regional Lockdown: March 17 | 60 | Urban | Assault/GSW/Stab Wounds |

| Figueiredo, Araújo, Martins et al. | Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery | Not Assessed | Belo Horizonte, Brazil | N/A | 20.4% (n = 11) | 26.1% (n = 23) | N/A | March 24 - 31, 2020 vs. same period 2019 | 1 Week after Regional Lockdown | 7 | Urban | Assault/GSW/Stab Wounds |

| Rajput, Sud, Rees, & Rutka | All | No Change | Liverpool England | Proportion | 17.4% (n = 21) | 16.2% (n = 28) | March 23 - May 10, 2020 vs. January 27 - March 15, 2020 | National Lockdown: March 23 | 48 | Urban | Stab Wounds | Rajput, Sud, Rees, & Rutka |

| Göksoy, Akça, & İnanç | General Surgery | No Change | Istanbul, Turkey | Proportion | 0.7% (n = 2) | 1.4% (n = 5) | p > 0.05 | March 15 - May 15, 2020 vs. same period 2019 | Declaration of study site as a "Pandemic Hospital:" March 15 | 61 | Urban | Firearm Injuries |

| Sherman, Khadra, Kale, et al. | All | Increase | New Orleans, USA | Proportion | 26% (n = 97) | 18% (n = 96) | p = 0.004 | March 20 - May 14, 2020 vs. same period 2019 | Regional Lockdown: March 20 | 55 | Urban | GSW |

| Walker, Heaton, Monroe, et al. | All | No Change | Muliple Locations: Rochester Minnesota, USA; Scottsdale, Arizona, USA; Jacksonville, Florida, USA | Proportion | 0% (n = 0) | 0% (n = 0) | p > 0.99 | Feburary 9 - April 21, 2020 vs. March 17 - April 21, 2019 | Regional Social Distancing: March 17 | 72 | Urban | GSW |

| Kurt NG & Gunes C | All | Not Assessed | Batman, Turkey | N/A | 0% GSWs during the pandemic | N/A | N/A | March 28 - April 28, 2020 vs. same period 2019 | National Social distancing mandates extended on March 28 | 31 | Urban | GSW |

| Murphy, Akehurst, & Mutimer | Orthopedic Surgery | No Change | Gloucester, UK | Rate | Assault: n = 1; Domestic Violence: n = 0 | Assault: 2017: n = 2, 2018: n = 1, 2019: n = 2; Domestic Violence: 2017: n = 0, 2018: n = 1, 2019: n = 0 | p > 0.99 | March 9 - April 26, 2020 vs. same period 2017–2019 | Regional Social Distancing: March 20 | 48 | Urban | Assault/Domestic Violence |

| Gosangi, Park, Thomas, et al. | Radiology | Increase | Boston, Massachusetts, USA | Proportion | 42% (n = 11) | 12% (n = 5) | p < 0.001 | March 11 - May 3, 2020 vs. same period 2017–2019 | Regional Lockdown March 24 | 53 | Urban | Domestic Violence |

| Rhodes, Petersen, Lunsford, & Biswas | All | Increase | Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, USA | Proportion | 1.7% (n = 50) | 1.1% (n = 78) | p < 0.01 | March 16 - April 30, 2020 vs. same period 2019 | Regional School Closures: March 16 | 45 | Urban | Domestic Violence |

| Benazzo, Rossi, Maniscalco, et al. | All | Not Assessed | Italy (15 Unspecified Level 1 or 2 Trauma Centers) | Rate | Weekly rate of domestic violence changes vs. 2019: (Week 1) increased by 15% (2020 n = 595); (Weeks 2–6): decreased by 30% (n = 595), 73% (n = 431), 55% (n = 380), 63% (n = 320), 72% (n = 333) | N/A | N/A | February 23 - April 4, 2020 | National Lockdown: March 9 | 41 | Urban | Domestic Violence |

| Olding, Zisman, Olding, & Fan K | All | Not Assessed | London, UK | N/A | 63.0% (n = 19) | 2018: 89.0% (n = 41), 2019: 96.0% (n = 46) | N/A | March 23 - April 29, 2020 | National Social Distancing Mandates: March 23 | 37 | Urban | Interpersonal violence (including domestic violence) |

| Qasim, Sjoholm, Volgraf, et al. | All | No Change | Philadelphia, PA | Proportion | 17.6% (n = 21) | 13.4% (n = 29) | p = 0.50 | March 9 - April 19, 2020 vs. same period 2019 | Regional Lockdowns: March 19 | 41 | Urban | Pediatric non-accidental trauma |

| Kovler, Ziegfeld, Ryan, et al. | All | Increase | Baltimore, Maryland, USA | Proportion | 13% (n = 8) | 3.6% (n = 7) | p = 0.009 | March 28 - April 27, 2020 vs. same period 2018–2019 | Regional Lockdown: March 27 | 30 | Urban | Physical Child Abuse |

Department

Most studies analyzed data from all departments in the hospital (n = 24), i.e., from a formal institutional trauma registry or full review of all encounters of patients in the hospital experiencing traumatic injury during the period of study. Department-specific studies were undertaken by Oral and Maxillary Facial Surgery (n = 6), Orthopedic Surgery (n = 5), Hand Surgery (n = 4), Neurosurgery (n = 2), Radiology (n = 2), and General Surgery (n = 1). Data did not show associations between department and outcome of changes in incidence of intentional injury, nor between department and study duration.

Method of study

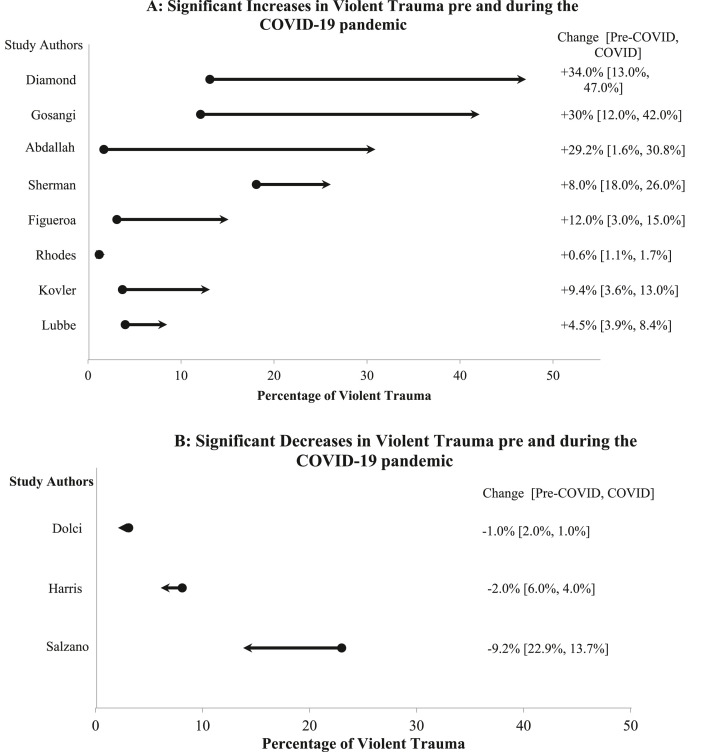

Studies primarily assessed changes in violent trauma with these data captured as a proportion (84%, n = 27) rather than as a rate (16%, n = 5). Of the five studies which assessed trends in violent trauma using rate data, three of which found no change in incidence of violent trauma.22, 23, 24 Morris and colleagues found a statistically significant decrease in violent trauma incidence (assaults decreased by half from approximately 400 during the month of April in 2018 and 2019 to 197 in 2020; gunshot injuries similarly decreased from 32 in 2018, 20 in 2019, to only 3 during the month of April in 2020)25; Benazzo and colleagues did not statistically assess changes in rate.26 Data did not show any association between analysis method and duration of study. All eight studies that reported an increase in violent trauma incidence examined data as a proportion,17, 18, 19 , 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 and five of the six studies demonstrating a decrease utilized proportion data.20 , 21 , 25 , 32, 33, 34 Magnitude of change in the proportion of violent trauma are shown in Fig. 2 , for figures that assessed these data statistically and found any change.

Fig. 2.

Of 44 total records included in this systematic review, 28 included a statistical assessment of changes in violent trauma before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Of these, 12 studies noted a statistically significant change. Studies examining these data by proportion of all trauma (n = 11) are shown here. Not shown: Morris and colleagues demonstrated a statistically significant decrease (p < 0.05) in rate of assault and gunshot wounds before (2018 and 2019) versus during (2020) the COVID-19 pandemic (Assault: 2018: n = 397, 2019: n = 426, 2020: n = 197; GSW: 2018: n = 32, 2019: n = 20, 2020: n = 3). All other relevant studies used proportion data and are shown in the graphs. Direction of change is shown with the arrows (2A: increasing proportion, right-capped arrow to signify the percentage of violent trauma in 2020; 2B: decreasing proportion, left-capped arrow).

Location

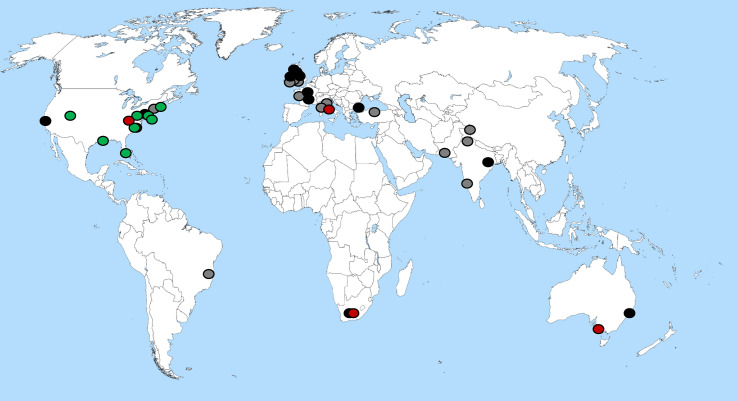

Rural-based studies accounted for two of the 44 records included in this systematic review. Neither study assessed changes in violent trauma statistically.35 , 36 The majority of studies were based in urban locations, with heavy bias towards high-income countries, including the United States (n = 14),17, 18, 19 , 22 , 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 , 37, 38, 39 Australia (n = 2),23 , 34 and Western Europe (n = 18).20 , 21 , 24 , 26 , 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53 Records were examined visually via placement of study results onto a world map. All eight studies showing an increase in violence were based in the United States. See Fig. 3 .

Fig. 3.

Study locations and outcomes. Green reflects studies observing increased incidence of violent trauma; red reflects studies showing a decrease. Black indicate studies that found no statistically significant change. Gray indicates studies that reported violent trauma, but did not statistically assess these data before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Not pictured: five studies were multi-center, and thus not included on this map. These are (with the assigned color as would be pictured on this map): (1) de Boutray and colleagues, multiple sites in France (gray); (2) Benazzo and colleagues, 15 unspecified level one trauma centers in Italy (gray); (3) Walker and colleagues, multiple sites in the United States (black); (4) MacDonald and colleagues, multiple sites in Scotland; and (5) Salzano and colleagues, multiple sites in Italy (red).

Duration

Though the studies included in this review captured data across slightly different time periods, all studies included in this review examined data during the Spring of 2020 (March and/or April), and the majority of studies (n = 30) examined data with the COVID-19 reference period starting within one week of a regional or national lockdown or social distancing order. Two studies assessed data beginning in January (duration of 121 and 181 days), and four assessed data beginning in February (duration 41–119 days). All others began examining data in March (n = 37) or April (n = 1). In order to assess the impact of study duration upon results, records were limited to those that assessed changes in violent trauma statistically (n = 28). These records were then stratified according to duration, in months.

All studies with an increase in violent trauma took place in the United States. In order to examine these data more closely, duration of studies in this specific region was then assessed. Two studies took place over one month, and both found an increase in violent trauma (assessed as proportion of all trauma cases).19 , 31 Of the seven studies that examined data across two months (31–60 days; lowest duration in this category was 41 days37), five noted increases in the proportion of violent trauma incidence.17 , 18 , 28, 29, 30 The other two studies found no change. Of these two, one study was limited to examination of cases of pediatric non-accidental trauma.37 Of the four remaining US-based studies, ranging from 71 to 181 days, three found no change in violent trauma22 , 32 , 39 and one found increased incidence.27

Among the nine studies that statistically examined changes in violent trauma (duration 13–90 days), only the longest study, Salzano and colleagues, noted a decrease in violent trauma.21 Australia based studies accounted for two records, over 60 and 61 days, and demonstrated no change (examined as a rate) and a decrease (examined as proportion) in violent trauma, respectively.23 , 34 Two studies examined data from South Africa: Morris and colleagues found that over 30 days there was a decrease in the rate of violent trauma incidence,25 and Zsilavecz and colleagues found no change in the proportion of violent trauma over 69 days.54

Discussion

Violent trauma has been characterized as the neglected disease of modern society, and its exact etiology remains poorly understood.12 Some risk factors associated with experiencing such violence have been elucidated in the past, including social isolation, poverty, low educational access, poor mental health, and weapon accessibility.15 , 55, 56, 57 Because of the complex interactions between these risk factors, effective evidence-based treatment modalities addressing violent trauma remains difficult.12 , 58 Nevertheless, it is evident that the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a substantial increase in the social factors associated with intentional injury, and the intersectionality of these risk factors during the pandemic was hypothesized to be associated with a universal increase in violent trauma incidence. However, of the 28 studies which statistically assessed this topic (N = 44 overall), results were not conclusive in supporting nor refuting this hypothesis: 15 studies showed no change, 8 showed an increase, and 5 showed a decrease.

Method of study

Nearly all of the studies included in this review assessed violent trauma data as a proportion of all trauma cases over the defined study period. This type of analysis would be expected to skew positive (i.e., higher propensity to report an increase in the proportion of violent trauma), for both population psychological and medical reasons. Specifically, emergent studies demonstrate a reduction in utilization of emergency department services overall, potentially reflective of reduced demand for services and/or reductions in seeking of needed care due to fears of Sars-Cov-2 infection during hospital treatment.59 In addition or alternatively, less non-intentional trauma may have occurred (e.g., work-related accidents, motor vehicle accidents) as individuals worked from and stayed at home: increases in the population rate of intentional trauma related to the pandemic without any change in non-intentional traumas would inflate the proportion, relative to previous years. In contrast to this expectation, only 8 studies reported an increase in the proportion of violent trauma (3 reported a decrease; 13 reported no change). Overall, among the eight studies that found an increase in violent trauma, half reported data on other non-intentional trauma types. Specifically, two studies found a significant decrease in motor vehicle collisions,28 , 30 one found a significant decrease in pedestrian versus automobile accidents (but no change in motor vehicle collisions),29 and one found an overall decrease in unintentional trauma (but no specific declines within motor vehicle collisions/pedestrian accidents).27 In contrast, of the three studies using proportion data which found a decrease in violent trauma, one found a similar decrease in motor vehicle collisions,20 and one found no change34 (the third did not report these data).21 Overall, it is possible that traumatic injuries in general increased after a brief decline at the onset of the pandemic, but that this period lasted only 1–2 months, after which other types of traumatic injuries increased, and so such data were lost: the average duration for studies reporting an increase was 52.6 days, versus 68.3 days among studies reporting a decrease, and 55.6 days among studies reporting no change.

Notably, Philadelphia, a major urban city with high pre-COVID rates of violence and which was reported on by three studies, reflected a consistent increase in the proportion of violent trauma regardless of duration at two weeks19 or 119 days22 (of note: the third study, with duration of 41 days, found no change in violent trauma when assessment was limited to non-accidental pediatric trauma).37 It was beyond the scope of this work to establish and assess, per city included in this study, a rating of “high” versus “low” pre-COVID violent trauma burden. However, such work is needed in the future in order to examine differential changes in violent trauma according to pre-pandemic conditions.

In any case, additional studies using rate data rather than proportional data are needed in order to provide a clearer, complete picture of the actual burden of intentional trauma during the pandemic. Such data would allow comparisons without obfuscation by any changes that may have occurred in non-intentional trauma during the pandemic.

Location

This review found that the majority of published studies examined hospital data based in urban populations. It is possible that that this reflects a bias in academic institutions being primarily based in urban centers, and/or an increased availability of ancillary funding to track these data with the support of a trauma registry staff within the hospital.

All studies demonstrating an increase in violent trauma were located in the United States. These findings reflect a noteworthy unique experience of the United States with regard to violent trauma during the COVID-19 pandemic. Across all of 2020, the United States had the highest number of COVID-19 related deaths overall in the world (approximately 330,000), but did not have the highest number of cases per 1 million people (US: 991; similar countries: Italy: 1,185, Spain 1,066, United Kingdom: 1,037, France: 953, Mexico: 945, Brazil: 896).14

While interpersonal altercations increased world-wide during the COVID-19 pandemic, such cases may have disproportionately resulted in hospitalization in the United States due to increased acuity of injuries, secondary to relatively higher firearm accessibility. Pre-pandemic reasons for higher rates of violent death in the United States as compared to another, similar country were examined in the classic 1988 “Tale of Two Cities” study. In this analysis, Sloan and colleagues examined rates of violent assault and homicide between Seattle, USA and Vancouver, Canada.57 They found that rates of these two events were similar in all categories of injury mechanism except for firearms: incidence of firearm-related assault and homicide were significantly higher in Seattle relative to Vancouver, a finding which the author attributed to differential access to guns.57 The United States has nearly double the number of guns per 100 people as any other nation (US: 88; next highest: Switzerland, 45.7),60 and a previous study limited to the United States showed an association between gun ownership and rate of violent death.61

Duration

Study durations ranged from 1 week to 181 days (approximately 6 months). While no definitive international trends emerged with regard to study length, continued monitoring of trends in violent trauma should still be undertaken, as the risk factors for violence remain present and will likely persist well-after the completion of national vaccination campaigns. Disaster medicine studies have demonstrated that mental health impacts of a disaster event can be noted at the population level nearly a year after resolution.62 Within the context of violent trauma in particular, hospital registries have shown increased incidence and increased acuity for at least six months following a discrete event.63 In contrast, the COVID-19 pandemic is on-going, with various national, regional, and local lockdowns going in and out of effect according to the status of infections in each locale.

Regional analyses limited to the United States, the only country where increases in violent trauma were recorded, demonstrated statistically significant increases in violent trauma during the first and second months of analyses (month 1: n = 2 of 2 reporting; month 2: n = 5 of 7 reporting), with no change during later months (examined as studies with duration of two and a half through six months). This finding may be related to the time period of data collection.

Limitations

This study included only studies that have been published in English. As such, there is a chance that our analyses are biased and limited to the experiences of Western countries (e.g., United States, United Kingdom, Australia, France, Italy, etc.). Indeed, this review did not find any studies from Eastern Asia and only one from South America. These gaps in the literature should be addressed in order to provide full understanding of the global experience of violent trauma and its associations with COVID-19. Nevertheless, this review did capture several studies from non-Western countries, from hospitals based in both urban and rural locations.

In addition, databases were searched approximately one year after the emergence and recognition of the Sars-Cov-2 virus in the human population. Global transmission lagged by a few months, and thus the time period for studies to have examined trends in violent trauma and have published on these data are likely the reason why average study duration of records included in this review was approximately two months. However, this review adequately captures the immediate societal reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic, lockdowns, social distancing, as measured by violent trauma incidence. Therefore, our data could provide a platform upon which policy-makers, particularly based in the United States where all increases in violent trauma were observed, can appropriate resources to address these immediate challenges.

In this study, violent trauma was defined very broadly. Studies reported on violent, interpersonal conflicts including domestic violence, child abuse, gunshot wounds, stabbings, and general assaults. Our definition of violent trauma was any study that reported on intentional, interpersonal conflict resulting in physical injury. This definition is broad, and thus may have contributed to the heterogeneity of our findings. For example, one may have expected gun-related violence to decrease while all-cause domestic violence increased during stay-at-home and lockdown mandates. Our review included hospital-based studies only, and theoretically could have included the exact diagnoses and injury mechanisms as described by the International Classification of Diseases.64 Future researchers with the capacity to report out exact diagnoses should do so, in order to improve the surveillance and monitoring of violent trauma. Moreover, researchers examining changes in any disease over time should report on both the change in relative proportion of the outcome of interest, as well as the absolute rate of increase or decrease. Our review is limited in that each study performed either a proportion or rate analysis, instead of both concurrently. Presentation of both methods of analysis in the future will enhance scientists and clinicians understanding of the true nature of societal events upon trauma and other health conditions of interest.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has shaped the world in a plethora of ways, including an indirect impact upon violent trauma. Studies remain conflicted regarding the exact nature of the impact; most studies that statistically assessed change in violent trauma reported no significant differences before and during the pandemic. Furthermore, the global impact of the pandemic upon violent trauma has not been felt consistently nor universally: the United States has uniquely experienced an increase in violent trauma presenting to hospitals. In particular, this impact of increased violence was skewed towards the initial onset of the pandemic, reported as increases in violent trauma as a proportion of all traumatic injuries. Longer-term studies are necessary in order to comprehensively dissect out regional and temporal trends, and to further quantify the absolute changes in trauma in order to mitigate an over-reliance upon proportion data.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2021.05.004.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Keni R., Alexander A., Nayak P.G., Mudgal J., Nandakumar K. COVID-19: emergence, spread, possible treatments, and global burden. Front Public Heal. 2020;8:216. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woolhandler S., Himmelstein D.U. Intersecting U.S. Epidemics: COVID-19 and lack of health insurance. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(1):63–64. doi: 10.7326/M20-1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . 2020. Double Jeopardy: COVID-19 and Behavioral Health Disparities for Black and Latino Communities in the U.S.https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/covid19-behavioral-health-disparities-black-latino-communities.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel J., Nielsen F., Badiani A., Patel B., Ravindrane R., Wardle H. Poverty, inequality and COVID-19: the forgotten vulnerable. Publ Health. 2020;183:110–111. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taquet M., Luciano S., Geddes J.R., Harrison P.J. Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: retrospective cohort studies of 62 354 COVID-19 cases in the USA. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;8(1):e1. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30462-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rozenfeld Y., Beam J., Maier H., et al. A model of disparities: risk factors associated with COVID-19 infection. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):126. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01242-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.M K.C., Oral E., Straif-Bourgeois S., Rung A.L., Peters E.S. The effect of area deprivation on COVID-19 risk in Louisiana. PloS One. 2020;15(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kieltyka J., Kucybala K., Crandall M. Ecologic factors relating to firearm injuries and gun violence in Chicago. J Forensic Leg Med. 2016;37:87–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tung E.L., Johnson T.A., Neal Y.O., Steenes A.M., Caraballo G., Peek M.E. Experiences of community violence among adults with chronic conditions: qualitative findings from chicago. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(11):1913–1920. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4607-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crandall M., Kucybala K., Behrens J., Schwulst S., Esposito T. Geographic association of liquor licenses and gunshot wounds in Chicago. Am J Surg. 2015;210(1):99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butts J.A., Roman C.G., Bostwick L., Porter J.R. 2015. Cure Violence : A Public Health Model to Reduce Gun Violence. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization . 2010. Injuries and Violence: The Facts. Geneva.https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/key_facts/en/#:∼:text=About 5.8 million people die each year as a result of injuries [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khalatbari-Soltani S., Cumming R.C., Delpierre C., Kelly-Irving M. Importance of collecting data on socioeconomic determinants from the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak onwards. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2020;74(8):620–623. doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-214297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization . 2020. Weekly Epidemiological Update - 29 December 2020.https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update---29-december-2020 Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harding D.J. Violence, older peers, and the socialization of adolescent boys in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Am Socio Rev. 2009;74(3):445–464. doi: 10.1177/000312240907400306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carey D.C., Richards M.H. Exposure to community violence and social maladjustment among urban african American youth. J Adolesc. 2015;37(7):1161–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rhodes H., Petersen K., Lunsford L., Biswas S. COVID-19 resilience for survival: occurrence of domestic violence during lockdown at a rural American college of surgeons verified level one trauma center. Cureus. 2020;12(8) doi: 10.7759/cureus.10059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gosangi B., Park H., Thomas R., et al. Exacerbation of physical intimate partner violence during COVID-19 pandemic. Exacerbation Phys Intim Partn Violence Dur COVID-19 Pandemic. 2021;298(1) doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020202866. E58-E45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diamond S., Lundy J.B., Weber E.L., et al. A call to arms: emergency hand and upper extremity operations during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hand Surg Glob Online. 2020;2(4):175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsg.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dolci A., Marongiu G., Leinardi L., Lombardo M., Dessì G., Capone A. The epidemiology of fractures and muskulo-skeletal traumas during COVID-19 lockdown: a detailed survey of 17.591 patients in a wide Italian metropolitan area. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2020 doi: 10.1177/2151459320972673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salzano G., Dell'Aversana Orabona G., Audino G., et al. Have there been any changes in the epidemiology and etiology of maxillofacial trauma during the COVID-19 pandemic? An Italian multicenter study. J Craniofac Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000007253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matthay Z.A., Kornblith A.E., Matthay E.C., et al. The DISTANCE study: determining the impact of social distancing on trauma epidemiology during the COVID-19 epidemic-an interrupted time-series analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;10 doi: 10.1097/ta.0000000000003044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacob S., Mwagiru D., Thakur I., Moghadam A., Oh T., Hsu J. Impact of societal restrictions and lockdown on trauma admissions during the COVID-19 pandemic: a single-centre cross-sectional observational study. ANZ J Surg. 2020;90(11):2227–2231. doi: 10.1111/ans.16307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy T., Akehurst H., Mutimer J. Impact of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic on the workload of the orthopaedic service in a busy UK district general hospital. Injury. 2020;51(10):2142–2147. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2020.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris D., Rogers M., Kissmer N., Du Preez A., Dufourq N. Impact of lockdown measures implemented during the Covid-19 pandemic on the burden of trauma presentations to a regional emergency department in Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa. African J Emerg Med. 2020;10(4):193–196. doi: 10.1016/j.afjem.2020.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benazzo F., Rossi S., Maniscalco P., et al. The orthopaedic and traumatology scenario during Covid-19 outbreak in Italy: chronicles of a silent war. Int Orthop. 2020;44(8):1453–1459. doi: 10.1007/s00264-020-04637-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdallah H.O., Zhao C., Kaufman E., et al. Increased firearm injury during the COVID-19 pandemic: a hidden urban burden. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;232(2):159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Figueroa J.M., Boddu J., Kader M., et al. The effects of lockdown during the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic on neurotrauma-related hospital admissions. World Neurosurg. 2020;S1878–8750(20):31850–31857. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.08.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lubbe R., Miller J., Roehr C., et al. Effect of statewide social distancing and stay-at-home directives on orthopaedic trauma at a southwestern level 1 trauma center during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Orthop Trauma. 2020;34(9):e343–e348. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sherman W., Khadra H., Kale N., Wu V., Gladden P., Lee O. How did the number and type of injuries in patients presenting to a regional level I trauma center change during the COVID-19 pandemic with a stay-at-home order? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020 doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000001484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kovler M., Ziegfeld S., Ryan L., et al. Increased proportion of physical child abuse injuries at a level I pediatric trauma center during the Covid-19 pandemic. Child Abuse Negl. 2020:104756. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rhodes H., Petersen K., Biswas S. Trauma trends during the initial peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in the midst of lockdown: experiences from a rural trauma center. Cureus. 2020;12(8) doi: 10.7759/cureus.9811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leichtle S., Rodas E., Procter L., Bennett J., Schrader R., Aboutanos M. The influence of a statewide “Stay-at-Home” order on trauma volume and patterns at a level 1 trauma center in the United States. Injury. 2020;51(11):2437–2441. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2020.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harris D., Ellis D., Gorman D., Foo N., Haustead D. Impact of COVID-19 social restrictions on trauma presentations in South Australia. Emerg Med Australasia (EMA) 2020 doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.13680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rathore L.P., Kalia S., Gupta L., et al. Change in trauma patterns in hilly areas of northern India during nationwide lockdown: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2020;14(10) doi: 10.7860/jcdr/2020/45605.14151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhat A.K., Kamath K.S. Comparative study of orthopaedic trauma pattern in covid lockdown versus non-covid period in a tertiary care centre. J Orthop. 2020;23:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2020.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qasim Z., Sjoholm L.O., Volgraf J., et al. Trauma center activity and surge response during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic-the Philadelphia story. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;89(4):821–828. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lara-Reyna J., Yaeger K.A., Rossitto C.P., et al. “Staying home”-early changes in patterns of neurotrauma in New York city during the COVID-19 pandemic. World Neurosurg. 2020;143:e344–e350. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.07.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walker L.E., Heaton H.A., Monroe R.J., et al. Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on emergency department presentations in an integrated health system. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(11):2395–2407. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hampton M., Clark M., Baxter I., et al. The effects of a UK lockdown on orthopaedic trauma admissions and surgical cases. Bone Jt Open. 2020;1(5):137–143. doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.15.bjo-2020-0028.r1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Atia F., Pocnetz S., Selby A., Russell P., Bainbridge C., Johnson N. The effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on hand trauma surgery utilization. Bone Jt Open. 2020;1(10):639–643. doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.110.BJO-2020-0133.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Boutray M., Kün-Darbois J.D., Sigaux N., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on the epidemiology of maxillofacial trauma activity: a French multicentre comparative study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;(20):30383. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2020.10.005. S0901-5027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fahy S., Moore J., Kelly M., Flannery O., Kenny P. Analysing the variation in volume and nature of trauma presentations during COVID-19 lockdown in Ireland. Bone Jt Open. 2020;1(6):261–266. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.16.BJO-2020-0040.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Druel T., Andeol Q., Rongieras F., Bertani A., Bordes M., Alvernhe A. Evaluation of containment measures' effect on orthopaedic trauma surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective comparison between 2019 and 2020. Int Orthop. 2020;44(11):2229–2234. doi: 10.1007/s00264-020-04712-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gumina S., Proietti R., Polizzotti G., Carbone S., Candela V. The impact of COVID-19 on shoulder and elbow trauma: an Italian survey. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020;29(9):1737–1742. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2020.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olding J., Zisman S., Olding C., Fan K. Penetrating trauma during a global pandemic: changing patterns in interpersonal violence, self-harm and domestic violence in the Covid-19 outbreak. Surgeon. 2020;(20):30103–30107. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2020.07.004. S1479-666X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ajayi B., Trompeter A., Arnander M., Sedgwick P., Lui D. 40 days and 40 nights: clinical characteristics of major trauma and orthopaedic injury comparing the incubation and lockdown phases of COVID-19 infection. Bone Jt Open2. 2020;1(7):330–338. doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.17.BJO-2020-0068.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yeung E., Brandsma D., Karst F., Smith C., Fan K. The influence of 2020 coronavirus lockdown on presentation of oral and maxillofacial trauma to a central London hospital. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;59(1):102–105. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2020.08.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rajput K., Sud A., Rees M., Rutka O. Epidemiology of trauma presentations to a major trauma centre in the North West of England during the COVID-19 level 4 lockdown. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00068-020-01507-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Régas I., Bellemère P., Lamon B., Bouju Y., Lecoq F., Chaves C. Hand injuries treated at a hand emergency center during the COVID-19 lockdown. Hand Surg Rehabil. 2020;39(5):459–461. doi: 10.1016/j.hansur.2020.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pichard R., Kopel L., Lejeune Q., Masmoudi R., Masmejean E. Impact of the COronaVIrus Disease 2019 lockdown on hand and upper limb emergencies: experience of a referred university trauma hand centre in Paris, France. Int Orthop. 2020;44(8):1497–1501. doi: 10.1007/s00264-020-04654-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saponaro G., Gasparini G., Pelo S., et al. Influence of Sars-Cov 2 lockdown on the incidence of facial trauma in a tertiary care hospital in Rome. Italy. Minerva Stomatol. 2020 doi: 10.23736/S2724-6329.20.04446-5. 0.23736/S0026-4970.20.04446-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.MacDonald D.R.W., Neilly D.W., Davies P.S.E., et al. Effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on orthopaedic trauma: a multicentre study across Scotlan. Bone Jt Open. 2020;1(9):541–548. doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.19.BJO-2020-0114.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zsilavecz A., Wain H., Bruce J.L., et al. Trauma patterns during the COVID-19 lockdown in South Africa expose vulnerability of women. S Afr Med J. 2020;110(11):1110–1112. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2020.v110i11.15124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Papachristos A.V., Wildeman C., Roberto E. Social Science & Medicine Tragic, but not random: the social contagion of nonfatal gunshot injuries. Soc Sci Med. 2015;125:139–150. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Papachristos A.V., Braga A.A., Hureau D.M. Social networks and the risk of gunshot injury. J Urban Health. 2012;89(6):992–1003. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9703-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sloan J.H., Kellermann A.L., Reay D.T., et al. Handgun regulations, crime, assaults, and homicide. A tale of two cities. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(19):1256–1262. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198811103191905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krug E., Dahlberg L.L., Mercy J.A., Zwi A.B., Lozano R. World report on violence and health. 2002. https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/en/summary_en.pdf

- 59.Pikoulis E., Solomos Z., Riza E. Gathering evidence on the decreased emergency room visits during the coronavirus disease 19 pandemic. Publ Health. 2020;185:42–43. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bangalore S., Messerli F.H. Gun ownership and firearm-related deaths. Am J Med. 2013;126(10):873–876. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Siegel M., Ross C.S., King C.I. The relationship between gun ownership and firearm homicide rates in the United States, 1981–2010. Am J Publ Health. 2013;103(11):2098–2105. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Phillippi S.W., Beiter K., Thomas C.L., et al. Medicaid utilization before and after a natural disaster in the 2016 baton rouge – area flood. Am J Publ Health. 2020;109(S4):S316–S321. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wahl G.M., Marr A.B., Brevard S.B., et al. The changing face of trauma: new orleans before and after hurricane katrina. Am Surg. 2009;75:284–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. ICD–10: External Cause of Injury Mortality Matrix.https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/injury/injury_matrices.htm [online] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.