Abstract

Confidentiality protections are a key component of high-quality adolescent sexual and reproductive health (SRH) care. Research has shown that adolescents value confidentiality and are more likely to seek care and provide honest information when confidentiality protections are implemented. However, many adolescents do not receive confidential SRH care. We synthesize studies of adolescents, parents, and providers to identify confidentiality-related factors that may explain why adolescents do not seek care or receive confidential services when they do access care. We present themes relevant to each population that address individual-level knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors, as well as clinic-level characteristics such as protocols, billing mechanisms, and clinic type. These findings have the potential to inform intervention efforts to improve the delivery of confidential SRH care for young people.

Keywords: confidentiality, adolescent, healthcare, sexual and reproductive health

Confidentiality protections are a vital aspect of adolescent healthcare because they encourage young people to seek care and disclose sensitive information that helps providers deliver appropriate clinical services.1 Multiple studies have found associations between confidentiality practices and receipt of recommended services.2–4 Additionally, ensuring young people have access to confidential services can help adolescents learn how to navigate the healthcare system and become autonomous healthcare consumers, in line with age-appropriate developmental milestones (e.g., increasing independence from parents).5 Confidentiality is particularly important for sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services, given possible sensitivity and stigma sometimes associated with sexual behavior.

Key tenets of confidential SRH care include an adolescent’s ability to self-consent for services without parental permission or notification, time alone with a provider during a clinic visit, and maintaining privacy of medical information during health care interactions and follow-up, including data stored in electronic health records (EHRs), communication via online patient portals (e.g., test results), and billing of services. Such practices are reflected in guidelines from professional medical organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine (SAHM), as well as legal protections.6–8 For example, all fifty states allow minors to consent to sexually transmitted infection (STI) services without parental permission, and many states allow minors to consent for contraceptives services, with some variation in the extent of protection.8

Despite these protections, receipt of confidential services is sub-optimal. Numerous studies have found adolescents may forgo care, including SRH care, due to confidentiality concerns, such as disclosure of sexual activity or sexual orientation to parents.4,9–13 Even adolescents who have clinic visits may not receive confidential care. For example, estimates suggest that only 14%-43% of adolescents have ever received time alone,14 one important aspect of confidential care.

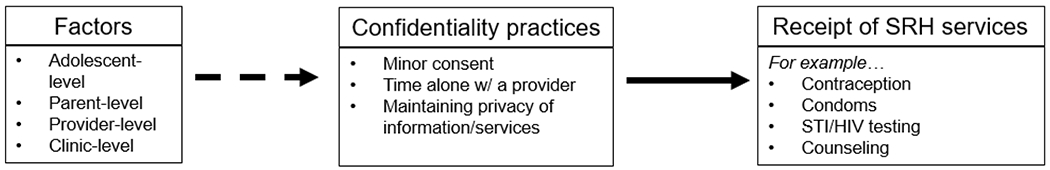

Although the relationship between confidentiality practices and receipt of SRH services is well-established,2–4 a critical outstanding question is how to increase implementation of confidential care, particularly in the context of SRH (Figure 1). Limited research has explicitly assessed barriers and facilitators to confidentiality practices, but there have been a number of studies with adolescents, parents, and providers that assess knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors in relation to confidential SRH services. Given that such data have the potential to illuminate factors that influence implementation of confidentiality practices and could be targets for interventions to increase confidential SRH care, we sought to synthesize this body of research.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework

Approach

In the absence of well-developed literature clearly identifying barriers and facilitators to confidentiality practices, precluding a systematic review, we conducted a narrative review, which offers a more flexible approach to synthesizing relevant studies.15 Using electronic database searches, we identified peer-reviewed literature about confidentiality and adolescents published through November 2017. In addition to including studies that focused specifically on confidentiality in the context of SRH service delivery, we reviewed studies about confidential adolescent health care generally, as every health care visit can potentially serve as an opportunity to address SRH. We chose not to limit studies to a specific clinic setting, type of visit, or provider type to identify potential variation based on these factors that could inform appropriate targeting of strategies for intervention. However, we did focus on literature primarily about young people under the age of 18 (although some samples also included young adults), for whom there are unique legal dimensions related to consent and notification and increased need for initiation of time alone given parental attendance at clinic visits.

From included studies, we grouped similar findings to identify confidentiality-related themes that may explain why adolescents do not seek care or receive confidential services when they do receive care. Our approach was informed by the triadic framework, which recognizes that leveraging the roles and interactions of the adolescent, parent, and provider triad has the potential to improve adolescent health.16,17 Specifically, we categorized themes as relevant to adolescents, parents, and providers, with the latter category including individual-level factors related to providers and other clinic staff as well as system-level factors related to the practice setting and operations. Although perhaps counterintuitive in the context of confidentiality, which involves some degree of limiting parental involvement in healthcare decision-making, our application of the triadic framework to inform our synthesis ultimately demonstrates the value of parent partnerships with both adolescents and providers in relation to increasing receipt of confidential SRH care.

Review of the Relevant Literature

ADOLESCENT THEMES

Younger adolescents less likely to receive confidential care.

A number of studies examined sociodemographic factors associated with receipt of time alone or adolescent perceptions of whether a clinic visit was “private/confidential”.3,18–24 These studies indicated that younger adolescents were less likely to receive confidential care than older adolescents.18–20,23,24

Low knowledge about confidentiality.

Studies demonstrated that many adolescents were unaware of specific protections for receiving confidential SRH services,25–28 although they may have had a basic understanding of confidentiality.27 For example, a study of Black adolescents aged 13-17 years found that approximately 90% understood that confidentiality means certain aspects of care can be kept private between an adolescent and their doctor,27 yet 76% of adolescents assumed providers would disclose to parents if they were tested for STDs or had an STD.27 Further, one study found that adolescents’ knowledge of consent and confidentiality laws in the state of Minnesota was low.25 Adolescents’ understanding of confidentiality seemed to vary by age, with younger adolescents less aware of their right to confidential care.25,28

General support for confidentiality yet some discomfort regarding time alone.

Multiple studies found adolescents valued confidentiality and having a private relationship with their providers,27,29–33 but several also documented adolescent girls’ discomfort with time alone.32,33 For example, in a qualitative study of Latina and Black girls aged 16-19 years in New York City, some respondents expressed feelings of fear and awkwardness about how their providers presented the concept of time alone, such that, they were reluctant to agree to it, felt uncomfortable disclosing information, and were concerned about prying questions from parents afterward.32 In another study of low-income adolescent enrollees in Florida’s Medicaid or the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), female participants reported wanting their mother present, even if they were not aware of all health risk behaviors.33 Younger adolescents may be more uncomfortable, as one study found that 11-14 year old participants desired provider disclosure of information to parents whereas 15-19 year olds wanted information kept private.34

Trust in providers is low.

Adolescents’ attitudes about confidentiality were often intertwined with trust in their provider. In a study of ninth grade students in Philadelphia, participants indicated that confidentiality was important in the provider-patient relationship, but they did not believe care was confidential unless honesty and respect were also present.30 Verbal reassurances also facilitated trust,30 although the qualitative study of Florida-based adolescents suggested they did not trust their provider would keep their information private, even with verbal assurances.33

PARENT THEMES

Low knowledge about confidentiality.

Studies indicated that parents have a limited understanding of confidentiality protections for adolescents.27,35,36 Basic knowledge of the concept may be high, as a survey of parents of Black adolescents found that the vast majority (88%) understood confidentiality means certain aspects of healthcare can be kept private between an adolescent and their doctor.27 However, another survey found that parental knowledge of specific legal protections in Minnesota was low.36 Moreover, parents had a range of misconceptions about the extent of confidentiality protections. For example, nearly all (96%) participants in the study mentioned previously with parents of Black adolescents believed a doctor will disclose any information they think the parent might want to know, even if the adolescent prefers the parent not be told.27 Most parents also thought provision of specific SRH services, such as testing and treatment for STDs, would be disclosed to parents.27 A qualitative study of Latino parents of 12- to 17-year-olds found that some parents believed confidentiality meant information was kept private between adolescent, provider, and parent.35

Mixed support for confidentiality.

Although parents may have recognized the importance of confidential services for adolescents, parental support for confidentiality appeared mixed.35,37,38 Most participants in the aforementioned qualitative study of Latino parents acknowledged that confidential care helps young people feel more comfortable talking to providers, including about SRH, and helps providers obtain accurate health information.35 Yet, a national online survey of parents found that 61% of respondents preferred to be in the examination room for the entire clinic visit.38 A different national web survey found that 46% of parents wanted full disclosure of confidential information obtained from adolescents during time alone, despite being informed of laws prohibiting this.37

Parental norms conflict with confidentiality.

A couple of studies suggested that parents’ desire to remain involved in their adolescent’s healthcare reflected parental norms that conflict with confidentiality practices.32,35 A qualitative study of Latina and Black mothers of adolescent girls 16-19 years found that many mothers were uncomfortable with confidential care because they worried providers would ask developmentally inappropriate questions (e.g., related to sexual activity).32 Latino parents in another qualitative study also expressed concern about not having important information to help their adolescent stay safe and healthy. In fact, some parents believed they had a right to this information because they were responsible for their teen.35

PROVIDER/CLINIC THEMES

Inadequate knowledge and training about confidentiality.

In an online survey of providers of various specialties, including family medicine and pediatrics, more than three-fourths (77%) of physicians said they needed additional training on confidentiality laws.39 In the same study, physicians identified low provider knowledge about what services are confidential as a barrier to implementing confidential care.39 Several studies suggested that providers have insufficient knowledge of legal protections related to confidentiality.26,36,39,40 For example, a survey conducted with a random sample of AAP members found that approximately 25% did not know whether their state law allowed adolescents to receive HIV/STI testing without parental consent.40 Other studies with providers highlight a need for training related to confidentiality protections and implementation protocols.41,42 Assessments of frontline office staff revealed similar knowledge gaps.43,44

Experiences with negative parental reaction.

One study documented provider experiences with negative parental reactions about confidential care.45 Most primary care clinicians at urban health centers reported difficult interactions with parents when asking for time alone or, more frequently, when parents desired to know adolescents’ test results (e.g., pregnancy test results).45 The study of Michigan physicians found that about 50% considered parental attitudes to inhibit provision of confidential care.39 Furthermore, in one study parents themselves reported reacting to time alone poorly.35

Limited communication and assurances of confidentiality.

Data suggest that lack of provider communication about confidentiality, particularly in terms of assurances offered directly to the patient, may create a barrier. A study of primary care clinicians in urban health centers found that some physicians limited communication about confidentiality with parents to avoid being “confrontational”.45 In a mystery shopper study of medical practices in the South Bronx in New York City, frontline staff rarely notified callers that services were confidential.46 There may be some variation based on provider training and/or setting as the study of urban-based primary clinicians noted that providers in adolescent clinics used a standardized approach introducing both adolescents and parents to confidentiality at the initial visit.45 Adolescents valued assurances of confidentiality from providers, viewing this specific communication as a provider’s responsibility.47 A study with parents also noted that provider communication about what to expect during a confidential visit minimizes parental concerns.35

Time constraints.

Time constraints emerged as a barrier to confidential care for adolescents.26,39,45 Almost all clinicians in a qualitative study of primary care clinicians cited time constraints as a barrier to offering time alone consistently.45

Type of visit associated with time alone.

Studies suggested that provision of time alone varied based on the type of clinic visit, with adolescents presenting for sexual healthcare and preventive visits more likely to receive time alone.3,18,45 For example, a study with primary care providers in New York found that among adolescents attending a clinic visit with their parents, those who presented with a sexual health complaint were six times more likely to receive time alone compared to adolescents seeking care for other reasons.3 The same study found significantly higher odds of receiving time alone for physicals compared to same-day/walk-in visits.3

Clinic type associated with confidentiality.

Clinic type also influenced adolescent perceptions and receipt of confidential care.48–53 Several studies indicated that adolescents perceive clinics located at or near schools to be less confidential, in part, given the possibility of peers observing them accessing care.48–50 Other studies documented adolescents’ concerns about seeking care at STI clinics because of associated stigma.51,52 Additionally, an assessment of confidentiality practices at Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) found that those participating in the Title X program, which funds health centers to provide confidential family planning services to low-income or uninsured individuals, were more likely to implement practices to maintain adolescents’ confidentiality compared with FQHCs without Title X funding.53

Physical space unfavorable to privacy.

Aspects of a clinic’s physical space may create a barrier to confidential care, according to several studies.31,33,50 In particular, providing reason(s) for visit or other private information in public spaces, such as in a check-in area, worried adolescents.31,50 The Florida-based study of adolescents found participants would prefer to provide sensitive information, specifically a health risk assessment, alone in a patient room.33 However, outpatient primary care providers in an intervention study reported insufficient examination rooms for adolescents to complete a risk assessment in a private space.26

Breaches of confidentiality linked to billing mechanisms.

Many studies highlighted billing practices as a barrier to confidential care,39,42,45,51,53–55 particularly given breaches may occur via explanation of benefits (EOB).45,54,55 The study of Michigan providers found that more than 70% reported that insurance issues inhibited their ability to provide confidential care.39 One study suggested some variation in the extent to which billing is an issue by Title X funding. FQHCs without Title X funding reported challenges that arise when adolescents request separate billing for family planning services, whereas FQHCs with Title X funding had resources to cover the costs without billing parents’ insurance.53

Lack of policy and protocol.

A number of studies underscored a lack of policies and protocols related to implementing confidential practices.26,39,40,45,53,56,57 For example, in a sample of pediatricians and family practitioners, only 43% reported having a specific policy regarding seeing adolescents without their parents present.56 Of those with policies, only 22% were categorized as permitting providers to routinely see adolescents without parents.56 Across multiple studies, gaps in protocols and policies were identified for the following topics: managing confidential test results, maintaining confidentiality with EHRs, addressing when confidentiality may be waived, scheduling appointments, documenting if time alone was spent with an adolescent, and billing for services.26,40,45,57 As a specific example, the study of Michigan providers found that systems issues with EHRs and uncertainty about parental access to EHRs inhibit provision of confidential care.39 Protocols for confidentiality may vary by clinic type, as Title X clinics were more likely to have confidentiality protocols and thus provide confidential care.53

Discussion

Although confidentiality is a key component of high-quality SRH care, many adolescents do not receive confidential services.58 From empirical studies with adolescents, parents, and providers, we identified confidentiality-related themes that capture potential barriers and facilitators to adolescent access to and provider delivery of confidential SRH services. These themes address individual-level knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of each population, as well as clinic-level characteristics such as protocols, billing practices, and physical space. Taken together, our findings underscore the potential for a triadic approach, which leverages the roles of and interactions between adolescents, parents, and providers, to improve receipt of confidential SRH services. Although we have focused on SRH services, much of the relevant literature addressed confidential care for health services generally, and many of the themes have broader implications as well.

Adolescents, parents, and providers each had low knowledge of specific confidentiality protections. Knowledge gaps among adolescents may prevent them from seeking care, and low knowledge among providers may inhibit receipt of confidential SRH services when they do. Adolescents should be educated about their right to confidential care, whether through school-based or broader health promotion efforts (e.g., communications campaigns, websites, etc.), to alleviate confidentiality concerns that may prevent them from seeking care. A recent analysis of online SRH content for young people highlights a need for comprehensive definitions of confidentiality that include time alone,59 a practice particularly important for younger adolescents who, as research suggests, are less aware of their right to confidential care.25,28 Providers also need information about confidentiality, and it is promising that they recognize gaps in their own training41,42 and are interested in further training.39 One potential opportunity for continuing medical education is to incorporate this topic in efforts to train providers on recent advances in adolescent SRH care (e.g., long-acting reversible contraception, HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis). Doing so may help ensure understanding of how newer services align with existing confidentiality protections, as well as reinforce basic confidentiality practices. Training on confidentiality should also extend to other clinic personnel (e.g., receptionists, nurses, and physician’s assistants), given low knowledge documented among frontline and other office staff.26,43,44

A notable theme in the literature given overwhelming evidence that adolescents value confidential care,27,29–33 is that there can be some degree of adolescent discomfort in receiving time alone, especially among younger patients who may not have prior experience navigating provider-patient relationships without a parent present. Parental and provider discussions that introduce adolescents to the concept of time alone before it is initiated may mitigate adolescent discomfort and are needed in light of a recent study suggesting that less than half of adolescents ages 13-14 years have ever talked about confidentiality with their provider.14 Providers and parents may work together to establish gradual and increasing time alone practices that strengthen the adolescent-provider relationship to promote comfort. For instance, parents may consciously facilitate direct conversations between their children and providers by allowing their children to answer providers’ questions themselves during visits. Providers should offer assurances that information will be kept private in a clear, specific, and developmentally appropriate manner. These assurances should be accompanied with a description of the limitations to confidentiality, including specific instances when confidentiality cannot be maintained. In addition to verbal assurances of confidentiality, practices can provide adolescents with written information (e.g., brochures, letters) that detail related rights and policies.

Efforts to address parental knowledge gaps that help resolve the tension we identified between parental norms and confidentiality practices32,35 may be most effective. This tension likely contributes to mixed parental support for adolescent receipt of confidential care35,37,38,60 as well as parent report and provider experiences of negative parental reactions.35,45 From the HPV vaccine literature, we know that provider concern about negative parental attitudes can be a barrier to service delivery.61 One potential strategy to overcome this barrier is the use of presumptive announcements that assume parents are ready to vaccinate rather than participatory conversations asking parents about their willingness to do so.62 In the context of confidentiality, this approach may be combined with an effort to align with the norms and values parents ascribe to regarding responsibility for their child’s safety and well-being. For example, the Adolescent Health Initiative offers a sample script for introducing confidentiality to parents that situates related practices within a developmental process (“As teens begin to develop into adults”), stresses the normative aspects of confidential care (“we always ask parents/guardians to wait outside”), and educates parents about the benefits of confidential care (“to encourage the teen to discuss their own view of their health”).63 Parents can also be educated about time alone through other channels (e.g., parenting websites) so that they can volunteer to step out of the room if a provider does not ask. Providers can promote parental monitoring and parent-adolescent communication and provide relevant health information that helps keep them involved.17 That said, not all adolescents have safe and supportive relationships with their parents and engaging parents may not always minimize parental concerns about confidentiality or be in the adolescent’s best interest.

At the clinic-level, the lack of policies and protocols related to confidentiality emerged as an important theme. Implementation science can address how clinic-level policies are written and implemented to facilitate the delivery of confidential SRH services. Protocols are key to implementation of policy and could likely serve to address a variety of other barriers identified, including time constraints, physical space, and billing practices. Time constraints are a well-known barrier in healthcare delivery given the multiple, competing demands providers face,64 and protocols could help increase efficiency. Confidentiality protocols could also promote task sharing whereby other appropriately trained clinic staff (e.g., nurses, health educators) are involved in delivering confidential care. However, such an approach requires careful implementation given evidence that having to discuss health issues with multiple people during the same visit increases adolescents’ concerns about confidentiality.50 Use of tablets or other technology for risk assessments could minimize burden on clinicians while also facilitating confidential disclosure of health information.33

Ensuring billing and insurance claims do not breach confidentiality remains a priority. As outlined in a recent joint position statement from SAHM and AAP, protocols play a key role in outlining actions to take when certain billing-related protections cannot be implemented.65 Sending EOBs directly to adolescents (e.g., personal email address instead of a household address), using a generic current procedural terminology code rather than specifying sensitive services, and referring adolescents elsewhere are possible approaches.65–67 Maintaining an updated list of free or sliding scale clinics, where services can be obtained by direct payment to minimize insurance and billing-related confidentiality issues, can facilitate referrals and receipt of services.67 Further, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) mandates coverage of many SRH services, such as contraceptive counseling and STI screening, without cost sharing, which could theoretically reduce concerns about billing-related breaches. However, adolescents may not understand this benefit or how to fully take advantage of it (e.g., scheduling appointments with in-network providers), as one recent study suggests youth had limited understanding of health insurance coverage in the context of confidentiality,68 and EOB statements may still disclose receipt of SRH services. Moreover, the provision of time alone has only increased negligibly (1%) since the passing of the ACA, which may be due to increasing demands placed on providers to deliver preventive services.69 Surprisingly, we did not identify empirical studies that addressed the confidentiality-related implications of the ACA for adolescents, although there has been more recent literature on this topic, including how extension of parental coverage to age 26 years may create confidentiality barriers for young adults.68,70 Likewise, we identified few studies describing confidentiality-related issues associated with EHRs and online patient portals, despite the attention this issue has received from professional medical organizations.71,72 Both SAHM and AAP recommend specific confidentiality protections while using EHRs, including requiring adolescent consent for release of information.71,72

Finally, themes related to clinic and visit type can inform efforts to minimize potential system-level barriers. As part of program requirements, Title X clinics have clearly defined protocols that support confidentiality and can serve as a model for other clinics. This may be particularly important for clinic settings where adolescents have particular concerns about confidentiality that may prohibit them from seeking care at specific locations, such as school-based clinics, clinics near schools, and STI clinics.48–52 Findings from these types of clinics underscore that adolescents have privacy concerns in relation to their peers as well as parents. Flexible hours, inconspicuous entrances, and minimal time in waiting rooms may help alleviate these concerns. Provision of select contraceptive services (i.e., emergency contraception, oral contraception) over-the-counter (OTC) may also facilitate confidential care, although we did not identify any studies empirically assessing this hypothesis, and substantial barriers to OTC emergency contraception access for adolescents have been documented.73,74 Improving confidentiality in acute care visits and in relation to a variety of health issues is also important, given evidence that providers are more likely to offer time alone for preventive care and sexual health-related visits.3,18,45

There are some additional gaps in our understanding of confidentiality worth noting. Across studies, “confidential care” was often not clearly operationalized or confidentiality was only defined in terms of time alone despite other key practices, such as minor consent and appropriate disclosure of test results. Future research should examine such aspects of confidential care, including predictors of their implementation to identify barriers as well as facilitators. Likewise, there is a need to address provider type in relation to confidentiality to inform who could particularly benefit from confidentiality-related training or systems-level intervention. Although we identified a limited number of studies examining provider specialty,26,39,44 findings were mixed (perhaps due to varied operationalization across studies), prohibiting identification of a clear theme.

There are also limitations to our approach. As mentioned previously, few studies have explicitly assessed barriers and facilitators to adolescents’ receipt of confidential care, which prohibited a systematic review. As a narrative review, our literature search was not exhaustive and some relevant articles may not have been included. In particular, we focused on studies including adolescents under the age of 18, and in doing so, we may have excluded key studies addressing billing and other systems-related dimensions of confidentiality that remain salient for young adults. Moreover, most findings were descriptive and did not directly link key factors (e.g., knowledge, clinic type) to care seeking and/or receipt of confidential care, but were included because we interpreted them to be potential barriers/facilitators. Some themes were also only supported by a limited number of studies. Nonetheless, our synthesis of adolescent, parent, and provider perspectives and experiences has highlighted potential explanations for why adolescent receipt of confidential care is sub-optimal.

Summary and Implications

In reviewing the literature on adolescent, parent, and provider perspectives and experiences with confidentiality, we have identified opportunities for intervention to address this persistent challenge to providing high quality clinical care for young people. Across many of our findings, partnerships between these three populations emerged as an approach (Box 1). Parents and providers can educate young people about confidentiality protections to increase knowledge and reduce discomfort with time alone. Providers can offer parents alternative ways to stay engaged in and promote their adolescents’ health by encouraging parent-adolescent communication and parental monitoring. Parents can signal to providers that they are supportive of time alone to reduce provider experience with, and anticipation of, negative parental reaction. Parents may benefit from intervention efforts that help them recognize and embrace their evolving role in protecting their children’s health by supporting acquisition of skills needed to navigate the healthcare system independently. These are just a few examples, but implementation science that considers other dimensions of such partnerships and how to appropriately institutionalize them is warranted. Continued attention to clinic-level factors, which seems to have been the recent focus of major professional organizations,72,75 is also critical. Combining these efforts with a triadic approach that addresses the complex interplay of adolescents, parents, and providers may have the most impact.

Box 1. Examples of a triadic approach to confidential sexual and reproductive care.

Provider – Parent interactions

Providers can explain the benefits of confidentiality in relation to the norms and values to which parents ascribe.

Parents can signal to providers their support of confidential care practices, such as time alone.

Providers can use presumptive announcements when informing parents about confidentiality.

Providers can offer parents alternative ways to stay engaged by providing relevant health information, encouraging parent-adolescent communication, and parental monitoring.

Provider – Adolescent interactions

Providers can educate adolescent patients about specific confidentiality protections, such as written information detailing their rights to confidential care.

Office staff can inform adolescents of the clinic’s confidentiality practices when appointments are scheduled.

Providers can provide verbal reassurances of confidentiality at each visit, while clearly explaining the limits of confidentiality.

Providers can gradually introduce confidentiality-related practices to adolescents to alleviate potential discomfort.

Parent – Adolescent interactions

Parents can prepare teens for time alone by having conversations with their teen early on, before time alone is implemented.

Parents can indicate that they support their teens receiving confidential care.

Implications and Contribution.

Efforts to improve the delivery of confidential care for adolescents may benefit from a triadic approach that recognizes and leverages the roles of parents, adolescents, and providers in advancing adolescent sexual and reproductive health, along with clinic-level efforts to maintain confidentiality.

Acknowledgments

Findings from this study were presented at the 2018 STD Prevention Conference in Washington, D.C.

Abbreviations:

- SRH

(Sexual and Reproductive Health)

- STI

(Sexually Transmitted Infection)

- AAP

(American Academy of Pediatrics)

- SAHM

(Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine)

- FQHC

(Federally Qualified Health Center)

- EOB

(Explanation of Benefits)

- EHR

(Electronic Health Records)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Brittain AW, Williams JR, Zapata LB, Moskosky SB, Weik TS. Confidentiality in Family Planning Services for Young People: A Systematic Review. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2 Suppl 1):S85–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leichliter JS, Copen C, Dittus PJ. Confidentiality issues and use of sexually transmitted disease services among sexually experienced persons aged 15–25 years—United States, 2013–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(9):237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Sullivan LF, McKee MD, Rubin SE, Campos G. Primary care providers’ reports of time alone and the provision of sexual health services to urban adolescent patients: results of a prospective card study. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(1):110–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thrall JS, McCloskey L, Ettner SL, Rothman E, Tighe JE, Emans SJ. Confidentiality and adolescents’ use of providers for health information and for pelvic examinations. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(9):885–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McNeely C, Blanchard J. The teen years explained: A guide to healthy adolescent development. Johns Hopkins Unviersity; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM. Bright futures: Guidelines for health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents. Am Acad Pediatrics; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ford C, English A, Sigman G. Confidential Health Care for Adolescents: position paper for the society for adolescent medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(2):160–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guttmacher Institute. An Overview of Minors’ Consent Law. 2018; https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/overview-minors-consent-law. Accessed June 13, 2018.

- 9.Reddy DM, Fleming R, Swain C. Effect of mandatory parental notification on adolescent girls’ use of sexual health care services. JAMA. 2002;288(6):710–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein JD, Wilson KM, McNulty M, Kapphahn C, Collins KS. Access to medical care for adolescents: results from the 1997 Commonwealth Fund Survey of the Health of Adolescent Girls. J Adolesc Health. 1999;25(2):120–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas N, Murray E, Rogstad K. Confidentiality is essential if young people are to access sexual health services. Int J STD AIDS. 2006;17(8):525–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones RK, Purcell A, Singh S, Finer LB. Adolescents’ reports of parental knowledge of adolescents’ use of sexual health services and their reactions to mandated parental notification for prescription contraception. JAMA. 2005;293(3):340–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peralta L, Deeds BG, Hipszer S, Ghalib K. Barriers and facilitators to adolescent HIV testing. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(6):400–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grilo SA, Catallozzi M, Santelli JS, et al. Confidentiality Discussions and Private Time With a Health-Care Provider for Youth, United States, 2016. J Adolesc Health. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green BN, Johnson CD, Adams AJJocm. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. 2006;5(3):101–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dittus PJ. Promoting Adolescent Health Through Triadic Interventions. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(2):133–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ford CA, Davenport AF, Meier A, McRee A-L. Partnerships between parents and health care professionals to improve adolescent health. J Adolesc Health. 2011;49(1):53–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edman JC, Adams SH, Park MJ, Irwin CE. Who gets confidential care? Disparities in a national sample of adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(4):393–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubin SE, Alderman EM, Fletcher J, Campos G, O’Sullivan LF, McKee MD. Testing adolescents for sexually transmitted infections in urban primary care practices: results from a baseline study. J Prim Care Community Health. 2011;2(3):209–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein JD, Handwerker L, Sesselberg TS, Sutter E, Flanagan E, Gawronski B. Measuring quality of adolescent preventive services of health plan enrollees and school-based health center users. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41(2):153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuentes L, Ingerick M, Jones R, Lindberg L. Adolescents’ and Young Adults’ Reports of Barriers to Confidential Health Care and Receipt of Contraceptive Services. J Adolesc Health. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Irwin CE Jr., Adams SH, Park MJ, Newacheck PW. Preventive care for adolescents: few get visits and fewer get services. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):e565–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fairbrother G, Scheinmann R, Osthimer B, et al. Factors that influence adolescent reports of counseling by physicians on risky behavior. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37(6):467–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shenkman E, Youngblade L, Nackashi J. Adolescents’ preventive care experiences before entry into the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP). Pediatrics. 2003;112(Supplement E1):e533–e541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loertscher L, Simmons PS. Adolescents’ knowledge of and attitudes toward Minnesota laws concerning adolescent medical care. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2006;19(3):205–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riley M, Ahmed S, Lane JC, Reed BD, Locke A. Using Maintenance of Certification as a Tool to Improve the Delivery of Confidential Care for Adolescent Patients. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017;30(1):76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lyren A, Kodish E, Lazebnik R, O’Riordan MA. Understanding confidentiality: perspectives of African American adolescents and their parents. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(2):261–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim SW, Chhabra R, Rosen A, Racine AD, Alderman EM. Adolescents’ views on barriers to health care: a pilot study. J Prim Care Community Health. 2012;3(2):99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brittain AW, Williams JR, Zapata LB, Pazol K, Romero LM, Weik TS. Youth-Friendly Family Planning Services for Young People: A Systematic Review. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2 Suppl 1):S73–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ginsburg KR, Forke CM, Cnaan A, Slap GB. Important health provider characteristics: the perspective of urban ninth graders. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2002;23(4):237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ginsburg KR, Winn RJ, Rudy BJ, Crawford J, Zhao H, Schwarz DF. How to reach sexual minority youth in the health care setting: The teens offer guidance. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(5):407–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKee MD, O’Sullivan LF, Weber CM. Perspectives on confidential care for adolescent girls. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(6):519–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kadivar H, Thompson L, Wegman M, et al. Adolescent views on comprehensive health risk assessment and counseling: assessing gender differences. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(1):24–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Britto MT, Tivorsak TL, Slap GB. Adolescents’ needs for health care privacy. Pediatrics. 2010:peds. 2010-0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tebb K, Hernandez LK, Shafer MA, Chang F, Eyre SL, Otero-Sabogal R. Understanding the attitudes of Latino parents toward confidential health services for teens. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50(6):572–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rock EM, Simmons PS. Physician knowledge and attitudes of Minnesota laws concerning adolescent health care. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2003;16(2):101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dempsey AF, Singer DD, Clark SJ, Davis MM. Adolescent preventive health care: what do parents want? J Pediatr. 2009;155(5):689–694. e681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gilbert AL, Rickert VI, Aalsma MC. Clinical conversations about health: the impact of confidentiality in preventive adolescent care. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(5):672–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riley M, Ahmed S, Reed BD, Quint EH. Physician Knowledge and Attitudes around Confidential Care for Minor Patients. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2015;28(4):234–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Henry-Reid LM, O’Connor KG, Klein JD, Cooper E, Flynn P, Futterman DC. Current pediatrician practices in identifying high-risk behaviors of adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):e741–e747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldstein L, Chapin J, Lara-Torre E, Schulkin J. The care of adolescents by obstetrician-gynecologists: a first look. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22(2):121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goyal MK, Dowshen N, Mehta A, Hayes K, Lee S, Mistry RD. Pediatric primary care provider practices, knowledge, and attitudes of human immunodeficiency virus screening among adolescents. J Pediatr. 2013;163(6):1711–1715. e1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hyden C, Allegrante JP, Cohall AT. HIV testing sites’ communication about adolescent confidentiality: potential barriers and facilitators to testing. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15(2):173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Akinbami LJ, Gandhi H, Cheng TL. Availability of adolescent health services and confidentiality in primary care practices. Pediatrics. 2003;111(2):394–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McKee MD, Rubin SE, Campos G, O’Sullivan LF. Challenges of providing confidential care to adolescents in urban primary care: clinician perspectives. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(1):37–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alberti PM, Steinberg AB, Hadi EK, Abdullah RB, Bedell JF. Barriers at the frontline: assessing and improving the teen friendliness of South Bronx medical practices. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(4):611–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coker TR, Sareen HG, Chung PJ, Kennedy DP, Weidmer BA, Schuster MA. Improving access to and utilization of adolescent preventive health care: the perspectives of adolescents and parents. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(2):133–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blake DR, Kearney MH, Oakes JM, Druker SK, Bibace R. Improving participation in Chlamydia screening programs: perspectives of high-risk youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(6):523–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rose ID, Friedman DB. Schools: A Missed Opportunity to Inform African American Sexual and Gender Minority Youth About Sexual Health Education and Services. J Sch Nurs. 2017;33(2):109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lindberg C, Lewis-Spruill C, Crownover R. Barriers to sexual and reproductive health care: urban male adolescents speak out. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 2006;29(2):73–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tilson EC, Sanchez V, Ford CL, et al. Barriers to asymptomatic screening and other STD services for adolescents and young adults: focus group discussions. BMC Public Health. 2004;4(1):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reed JL, Huppert JS, Gillespie GL, et al. Adolescent patient preferences surrounding partner notification and treatment for sexually transmitted infections. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(1):61–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beeson T, Mead KH, Wood S, Goldberg DG, Shin P, Rosenbaum S. Privacy and Confidentiality Practices In Adolescent Family Planning Care At Federally Qualified Health Centers. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2016;48(1):17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rubin SE, McKee MD, Campos G, O’Sullivan LF. Delivery of confidential care to adolescent males. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(6):728–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mullins TLK, Zimet G, Lally M, Kahn JA, Interventions AMTNfHA. Adolescent human immunodeficiency virus care providers’ attitudes toward the use of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis in youth. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2016;30(7):339–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bravender T, Price CN, English A. Primary care providers’ willingness to see unaccompanied adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2004;34(1):30–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mead KH, Beeson T, Wood SF, Goldberg DG, Shin P, Rosenbaum S. The role of federally qualified health centers in delivering family planning services to adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(1):87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Copen CE, Dittus PJ, Leichliter JS. Confidentiality Concerns and Sexual and Reproductive Health Care Among Adolescents and Young Adults Aged 15–25. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Steiner RJ, Pampati S, Rasberry CN, Liddon N. “Is it really confidential?” A content analysis of online information about sexual and reproductive health services for adolescents. J Adolesc Health. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Song X, Klein JD, Yan H, et al. Parent and adolescent attitudes towards preventive care and confidentiality. J Adolesc Health. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Holman DM, Benard V, Roland KB, Watson M, Liddon N, Stokley S. Barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among US adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. JAMA pediatrics. 2014;168(1):76–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brewer NT, Hall ME, Malo TL, Gilkey MB, Quinn B, Lathren C. Announcements versus conversations to improve HPV vaccination coverage: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2017;139(1):e20161764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Adolescent Health Initiative. Confidentiality Best Practices. In. Spark Trainings 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yarnall KS, Pollak KI, Østbye T, Krause KM, Michener JL. Primary care: is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health. 2003;93(4):635–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.The Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine and the American Academy of Pediatrics. Confidentiality Protections for Adolescents and Young Adults in the Health Care Billing and Insurance Claims Process. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58(3):374–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sedlander E, Brindis CD, Bausch SH, Tebb KP. Options for assuring access to confidential care for adolescents and young adults in an explanation of benefits environment. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(1):7–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rasberry CN, Liddon N, Adkins SH, et al. The importance of school staff referrals and follow-up in connecting high school students to HIV and STD testing. J Sch Nurs. 2017;33(2):143–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rogers J, Silva S, Benatar S, Briceno ACL. Family Planning Confidential: A Qualitative Research Study on the Implications of the Affordable Care Act. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(6):773–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Adams SH, Park MJ, Twietmeyer L, Brindis CD, Irwin CE. Association between adolescent preventive care and the role of the Affordable Care Act. JAMA pediatrics. 2018;172(1):43–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Loosier PS, Hsieh H, Cramer R, Tao G. Young Adults’ Access to Insurance Through Parents: Relationship to Receipt of Reproductive Health Services and Chlamydia Testing, 2007–2014. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(5):575–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Blythe MJ, Adelman WP, Breuner CC, et al. Standards for health information technology to ensure adolescent privacy. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):987–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gray SH, Pasternak RH, Gooding HC, et al. Recommendations for electronic health record use for delivery of adolescent health care. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54(4):487–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wilkinson TA, Vargas G, Fahey N, Suther E, Silverstein M. “I’ll see what I can do”: What adolescents experience when requesting emergency contraception. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54(1):14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Uysal J, Tavrow P, Hsu R, Alterman A. Availability and Accessibility of Emergency Contraception to Adolescent Callers in Pharmacies in Four Southwestern States. J Adolesc Health. 2019;64(2):219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Adolescent confidentiality and electronic health records. Committee Opinion No. 599. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:1148–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]