Abstract

Reducing post-acute care in skilled nursing facilities, in favor of home-based care, is a leading cost-saving strategy in new payment models. Yet the extent to which SNF stays can be safely shortened remains unclear. We leveraged the exposure of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries without supplemental coverage to cost sharing after SNF benefit day 20 as a cause of shortened stays. Marked reductions in length of stay, due to cost sharing, shifted patients to home more than a week earlier than expected without cost sharing, producing a discharge spike. These reductions were not associated with clear evidence of compromised patient safety as measured by death, hospitalization for fall-related injuries, or all-cause hospitalization within 9 days of the spike. Adverse consequences requiring hospitalization could not be excluded for a small proportion of shortened stays. These findings suggest potential for improving post-acute care efficiency, as SNF stays may be unnecessarily long to ensure safety.

Care in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) accounts for nearly half of all post-acute spending in Medicare and is thought to be a major source of wasteful care.1 The per-diem basis for payment and lack of consensus on clinical indications for care in a facility, as opposed to at home, may contribute to unnecessary or excessively long SNF stays.2 Accordingly, post-acute care in SNFs has been a primary target for providers in new payment models.

Shifting patients from facilities to home, however, could be harmful to patients if they continue to require the 24-hour in-person clinical monitoring uniquely provided in facilities to ensure their safety and prevent adverse events like falls. Although there is interest in caring for more post-acute patients in the lower-cost home setting through in-person or virtual care, an important prerequisite for this shift is ensuring patient safety. When this condition is met, there is potential for greater use of home-based models, which could be improved to address other clinical goals where current home health care may fall short. A clearer understanding of the role of SNF care is critical as policy makers consider stronger and more widespread incentives to curtail this form of post-acute care.

Much of the current evidence on the value of SNF care is descriptive, including the wide geographic variation in post-acute spending in Medicare that is unrelated to outcomes.3 Fewer studies have used quasi-experimental designs to directly assess the consequences of restricting institutional post-acute care. Evaluations of accountable care organization (ACO) and bundled payment models have found reductions in SNF use and length-of-stay without evidence of adverse outcomes, but the reductions have been modest.4–7 To our knowledge, only four quasi-experimental studies have attempted to isolate the causal effects of potentially larger reductions in post-acute SNF care,8–10 including only one that examined effects of shorter SNF stays conditional on discharge to a SNF (as opposed to effects of hospital discharge to home vs. SNF).11 That study examined SNF discharges hastened by cost sharing for Medicare patients that applies after the 20th day of a SNF benefit period. Lacking data on supplemental coverage to compare patients exposed vs. not exposed to cost sharing, the study focused on patients with multiple SNF stays within a Medicare benefit period and found that patients who reached their 20th benefit day sooner during their second SNF stay (because their prior stay was longer) were discharged earlier and rehospitalized at a significantly higher rate.11 However, these patients also were observably higher-risk, as might be expected from their longer initial SNF stays. Thus, the higher rate of rehospitalization could not be confidently attributed to earlier discharge.

Building on this literature, we conducted two sets of analyses using national survey data on supplemental coverage and Medicare claims and enrollment data to characterize the extent to which SNF discharges accelerated by cost sharing were safe. The cost sharing that begins after the 20th day of a SNF benefit period for Medicare beneficiaries without supplemental coverage is substantial (e.g., $158/day in 2015) and affects both demand-side and supply-side incentives. The cost sharing not only presents an additional factor for patients and SNFs to weigh when considering stays beyond day 20 but also gives SNFs a financial incentive to discharge sooner, as some patients may be unable to pay the out-of-pocket expense.

In our first analysis, we quantified the shifts in patient location resulting from the onset of cost sharing. Among patients exposed to cost sharing after benefit day 20 due to a lack of supplemental coverage, a large spike in discharges entirely to home, for example, would be consistent with SNFs encouraging unnecessarily long stays. At the other extreme, a spike primarily in transfers to hospitals or other facilities, where patients without supplemental coverage would not face cost sharing, would be consistent with SNFs keeping only patients in clear need of continued institutional care beyond day 20.

Second, we examined whether shortened stays resulted in higher rates of death, all-cause hospitalization, and hospitalization for fall-related injuries. We conducted difference-in-differences analyses comparing daily rates of these outcomes between patients more vs. less exposed to cost sharing, before vs. after the expected initiation of cost sharing. Although increases in mortality due to shortened stays would provide clear evidence of unsafe discharges, increases in hospitalizations may not necessarily reflect adverse consequences of earlier discharge. Appropriate shortening of a SNF stay could result in subsequent hospitalization for routine conditions or complications that would have occurred and been managed in the SNF if the stay had not been shortened. That is, remaining in a SNF may censor hospitalizations for clinical developments that occur independent of the timing of discharge. Consequently, our analysis of all-cause hospitalization rates provides an upper bound on adverse consequences of accelerated discharge that necessitate rehospitalization. We examined hospitalization for fall-related injuries as an adverse outcome that relates more specifically to the withdrawal of intensive monitoring available in facilities.

To the extent that cost sharing causes unsafe discharge decisions that would not occur in response to supply-side incentives only, our results may be interpreted more generally as an upper bound on the adverse consequences of provider-driven efforts to achieve similar reductions in SNF length of stay. Thus, our analyses help to gauge the potential for reducing institutional post-acute care safely even if results do not generalize directly to provider interventions encouraged by new payment models.

STUDY DATA AND METHODS

Study Population

We used Medicare claims and enrollment data to examine all SNF benefit periods covered by Part A that were initiated for fee-for-service beneficiaries from 2007–2015. In Medicare, a benefit period begins with the first SNF stay after no SNF care in the preceding 60 days (see Appendix for handling of multiple SNF stays per benefit period).12 We limited our study cohort to beneficiaries who reached day 15 of the Medicare SNF benefit period and followed those beneficiaries for 14 days (through day 28). This restriction minimized contamination from smaller discharge spikes associated with Minimum Data Set assessments prior to day 15 and on day 30 (Exhibit A5).12 We excluded beneficiaries dually enrolled in Medicaid because of unclear effects of Medicare cost sharing on SNF incentives for this group (Appendix Section 1.2).12

We identified three comparison groups with varying levels of exposure to cost sharing after day 20 of Medicare’s SNF benefit period: 1) a fully exposed group of Medicare Savings Program (MSP) enrollees who receive state assistance for Medicare premiums but not for cost sharing; 2) a high-exposure group of beneficiaries with a low probability of having any supplemental coverage; and 3) a low-exposure group with a high probability of having generous (Medigap or employer-based) supplemental coverage.

Although data on MSP categories are included in Medicare enrollment files, data on private supplemental coverage are not. Therefore, we used survey data on supplemental coverage from the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) to predict supplemental coverage based on patient characteristics ascertained from linked Medicare claims and enrollment data. We applied model coefficients to the full study population to define the high-exposure and low-exposure groups (Appendix section 1.3).12

Study Variables

Time

We followed patients for 14 calendar days starting on benefit day 15, regardless of whether they were discharged. Retaining discharged patients in the cohort was critical for valid estimation of effects of cost-sharing exposure on post-discharge location and outcomes. Thus, although we refer to the study period as days 15–28, the day corresponds to the SNF benefit day only for patients who remained in a SNF. For all patients, it corresponds to the number of calendar days after benefit day 15 (e.g., “day 28” is 13 calendar days after benefit day 15).

Patient Location

We assessed each patient’s location on each calendar day following SNF benefit day 15. Specifically, we assessed whether the patient was in a SNF, in any facility for acute or post-acute care (i.e., SNF, hospital, inpatient rehabilitation facility, or a long-term care hospital), or conversely at home. We further distinguished at home receiving (or referred for) home health care vs. at home without home health care. In a supplementary analysis, we separated out the small proportion of patients in a long-term residential facility from those at home and determined whether patients were receiving hospice care (Appendix section 2.4).12

Daily Rates of Death and Hospitalization

On each calendar day after day 15, we assessed whether the patient was hospitalized (from claims) or died (from the Master Beneficiary Summary File). We used previously described methods13 to identify hospitalizations for fall-related injuries — hospitalizations that might reflect the sequelae of unsafe discharges from SNFs with greater specificity than all-cause hospitalizations.

Patient Characteristics

As covariates for analyses of patient location, hospitalizations, and mortality, we assessed age, sex, disability as the original reason for Medicare eligibility, a chronic condition count, and area-level measures of household income, poverty, educational attainment, and living alone (Appendix section 1.5).12

Statistical Analysis

We conducted two sets of analyses. First, we estimated models to quantify the discrete shifts after day 20 (i.e., discontinuities in the daily trend) in patient location(Appendix section 1.6).12 We estimated these models separately for each group of beneficiaries with varying cost-sharing exposure and checked robustness to alternative model specifications (Appendix sections 2.3, 2.6).12

Second, we conducted difference-in-differences comparisons of daily rates of death and hospitalization (all-cause or fall-related) between cohorts with more vs. less exposure to cost sharing after day 20, before vs. after the expected onset of cost sharing. To enhance statistical power of these analyses, we combined the full and high-exposure cohorts in comparisons with the low-exposure cohort. Specifically, we estimated linear models for each outcome as a function of time (fixed effects for each day of the 14-day study period), an indicator for cohort exposure, and an interaction between the cohort indicator and the day 20–28 period (when cost sharing would apply for those remaining in a SNF). The latter term estimated the effect of cost-sharing exposure on the outcome (the differential change associated with exposure). Models also included state, year, day of the week, and seasonal fixed effects, as well as patient covariates (Appendix section 1.7).12

For the all-cause hospitalization outcome, we also added an interaction between the exposed cohort and days 20–21 to remove the contribution of SNF-to-hospital transfers induced by cost sharing (Exhibit A20).12 Transfers to a hospital to avoid patient cost sharing effectively continue facility care and thus would not reflect an adverse consequence of a premature discharge home; such transfers also would not be expected in new payment models that reward lower episode or total spending. With days 20–21 removed, estimates may be interpreted as the effect of cost-sharing exposure on hospitalizations that potentially followed discharge home. Mortality and fall-related hospitalizations were not subject to this interpretability issue related to transfers, as transfers do not mechanically increase recorded rates of falls or deaths.

The differential changes estimated by our model are population estimates of the effect of exposure to cost sharing on daily mortality or hospitalization. These estimates understate the effect of earlier discharge induced by cost sharing on patient outcomes because cost sharing shortens stays for only a proportion of exposed patients (most patients incur the cost sharing). To facilitate interpretation of results as changes in outcomes due to earlier discharge (i.e., treatment effects on the treated), we rescaled the population estimates to approximate the effect of spending one fewer day in a SNF from day 20–28 on the cumulative incidence of death or hospitalization by day 28.

In the context of our study, results for all-cause hospitalizations were challenging to interpret and likely overstate adverse effects of earlier discharge for two reasons. First, although we removed a transfer period on days 20–21 from our analysis of all-cause rehospitalization, cost sharing may have induced subsequent SNF-to-hospital transfers to avoid the out-of-pocket expense for patients, particularly on day 22 (Exhibits A17, A20).12 Second, remaining in a SNF may effectively censor some hospitalizations. For example, consider a patient who develops a urinary tract infection (UTI) with associated delirium on day 27 of a stay that is not shortened by cost sharing. The UTI is diagnosed and treated by the SNF. If instead, the same patient were discharged home a week earlier on day 20 due to cost sharing, the patient would develop the UTI and delirium at home, potentially requiring a brief hospitalization to treat it before safely returning home again. In this scenario, the patient may suffer no adverse clinical outcome from earlier discharge, but the utilization pattern differs. Effectively, readmission from home reflects a different set of adverse events than readmission from a SNF even when longer SNF stays have no protective effect; the meaning of the outcome thus changes upon discharge home. For these reasons, our estimated differential changes in all-cause hospitalization rates present an upper bound for premature discharges that led to an adverse event requiring hospitalization.

Limitations

Our study has several important limitations. First, our results pertain to patients discharged in response to cost sharing after spending 19 days in a SNF and may not generalize to other patients or other lengths of stays. Therefore, our study cannot provide guidance to risk-bearing providers about how much to restrict SNF use, but it does characterize the effects of a substantial reduction in length of SNF stays and thus helps gauge the potential for safely shortening stays for some patients.

Second, our comparison groups differed systematically in their characteristics, as expected for groups that differ in insurance coverage. However, as might be expected from the groups’ common status as recently hospitalized and reaching SNF benefit day 15, they had nearly identical baseline discharge rates and their baseline outcomes did not differ markedly. Moreover, non-equivalent control groups are common in difference-in-difference analyses, which assume only that group differences in outcomes would stay constant in the absence of intervention. We found no evidence of departures from this assumption in comparisons of group trends prior to the onset of cost sharing. In a sensitivity analysis, we also excluded beneficiaries who qualified for Medicare based on disability to better balance the more and less exposed cohorts.

Third, we could assess supplemental coverage directly for MSP enrollees but relied on predictions based on CAHPS data to identify other beneficiaries with a low probability of having private supplemental coverage. We address the resulting measurement error by rescaling our estimates to reflect effects of shortened stays as opposed to effects of greater exposure to cost sharing.

Fourth, because we lacked data on functional status, we are unable to determine whether earlier SNF discharge affected patients’ functional recovery. Nevertheless, our study is well suited to test whether SNF patients can be safely discharged sooner, a precondition for continued rehabilitative therapy in lower-cost outpatient or home settings. Finally, we could not assess the incremental burden of shorter SNF stays on caregivers.

STUDY RESULTS

Patient characteristics differed substantially between groups with different exposure to SNF cost sharing (Exhibit 1). Patient characteristics were strongly predictive of private supplemental coverage status, allowing identification of a low-exposure group with a high mean probability (0.72) of having Medigap or employer-sponsored supplemental policies and a high-exposure group with a low mean probability (0.26) of having any supplemental coverage (Exhibits A2–A3).12

Exhibit 1.

Characteristics of Study Population by Level of Exposure to SNF Cost Sharing

| Exposure to cost sharing after benefit day 20 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| More exposed to cost sharing | Less exposed to cost sharing | |||||

| Full exposurea | High exposureb | Low exposurec | ||||

| n (SNF episodes) | 202,342 | 292,715 | 1,221,333 | |||

| Mean age,d SD | 76.2 | 12.0 | 80.8 | 12.3 | 81.9 | 7.5 |

| Male, %d | 30.8 | 24.7 | 42.9 | |||

| Race, %d | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 78.2 | 80.9 | 96.2 | |||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 15.7 | 13.6 | 1.3 | |||

| Hispanic | 4.5 | 3.6 | 1.0 | |||

| Other | 1.7 | 1.9 | 1.5 | |||

| Disabled, %d,e | 37.0 | 27.8 | 0.0h | |||

| Mean chronic condition count,f SD | 8.9 | 3.7 | 7.2 | 3.9 | 8.8 | 3.6 |

| Median household income in ZIP code tabulation area, $g SD | 29,600 | 10,000 | 31,200 | 10,700 | 36,800 | 12,900 |

| Percent living alone in ZIP code tabulation area, %g | 28.2 | 29.3 | 28.0 | |||

| Highest educational attainment in ZIP code tabulation area, %g | ||||||

| Percent of residents with a college degree | 14.6 | 15.4 | 19.6 | |||

| Percent of residents with a high school degree | 60.3 | 62.9 | 69.4 | |||

| Percent of residents in poverty in ZIP code tabulation area, %g | 11.8 | 10.5 | 7.63 | |||

Source: Authors’ calculations using fee-for-service Medicare claims data

Notes:

SNF = skilled nursing facility

SD = standard deviation

Medicare Savings Program enrollees exposed to cost sharing

Beneficiaries unlikely to have supplemental coverage

Beneficiaries likely to have employer-sponsored supplemental or Medigap coverage

Patient characteristics obtained from Medicare enrollment file corresponding to year of SNF episode.

Disability status determined using beneficiaries’ original reason for Medicare eligibility (includes patients who became eligible through end-stage renal disease).

Count of 27 conditions from the Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse (CCW)

Characteristic in patients’ residential ZIP code tabulation areas using American Community Survey data

Disabled individuals were excluded from the Low-exposure group to identify patients with a high probability of having supplemental coverage that covers SNF cost sharing. See appendix for additional details.

Shifts in Patient Location

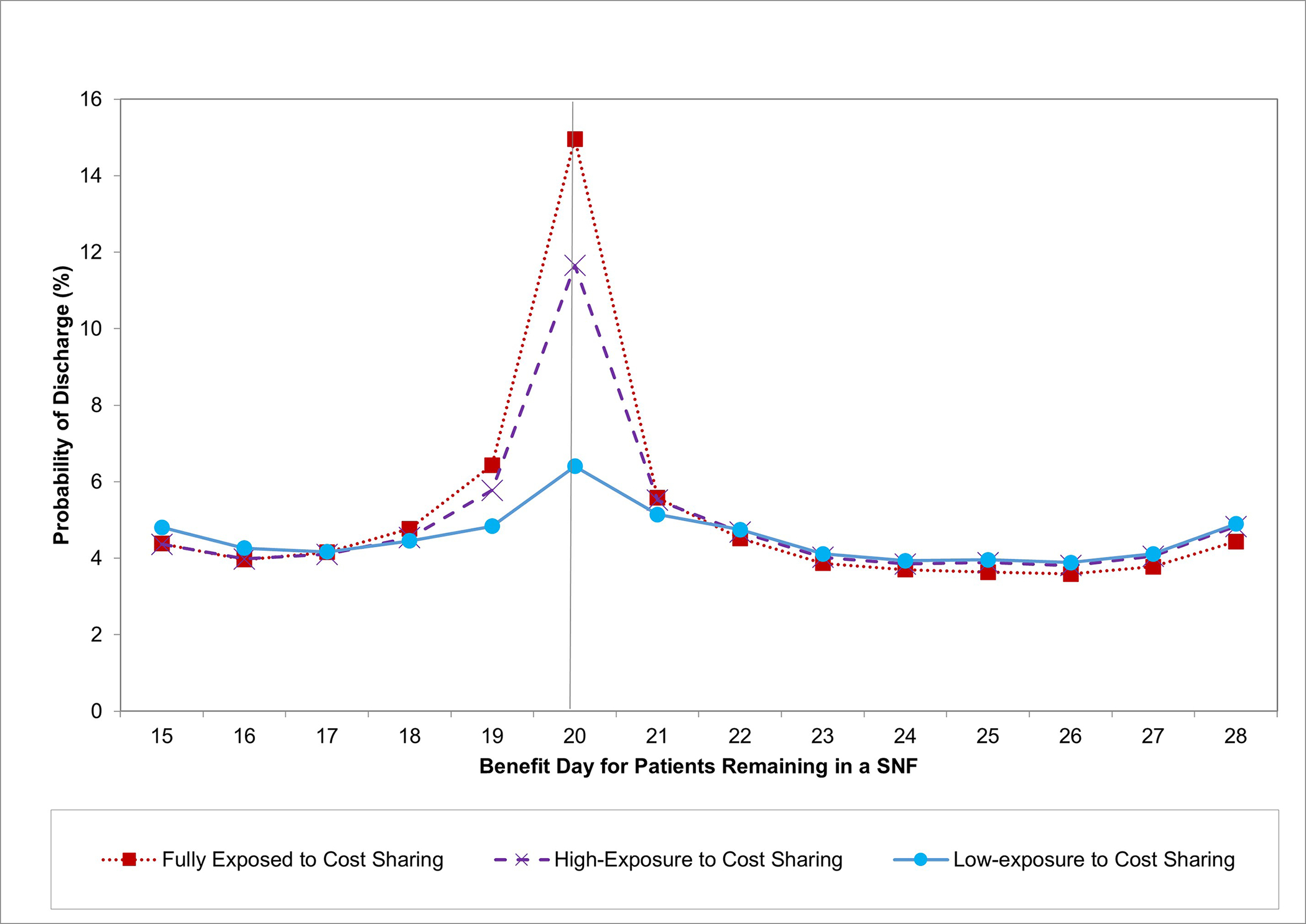

Discharge spikes on day 20 were greater for patients in the full-exposure and high-exposure groups than those in the low-exposure group (Exhibit 2). Discharge spikes also varied monotonically with the predicted probabilities of supplemental coverage used to derive the high-exposure and low-exposure groups (Exhibit A4).12

Exhibit 2. Daily Rate of Discharge from SNFs by Exposure to Cost Sharing.

Source: Authors’ calculations using fee-for-service Medicare claims data.

Notes: SNF = Skilled Nursing Facility. Daily discharge rates (the proportion of patients in a SNF on a given day who are discharged on that day) are plotted by benefit day. Rates are adjusted for state, year, and day of the week.

The vertical line denotes the last day before cost sharing begins for exposed groups.

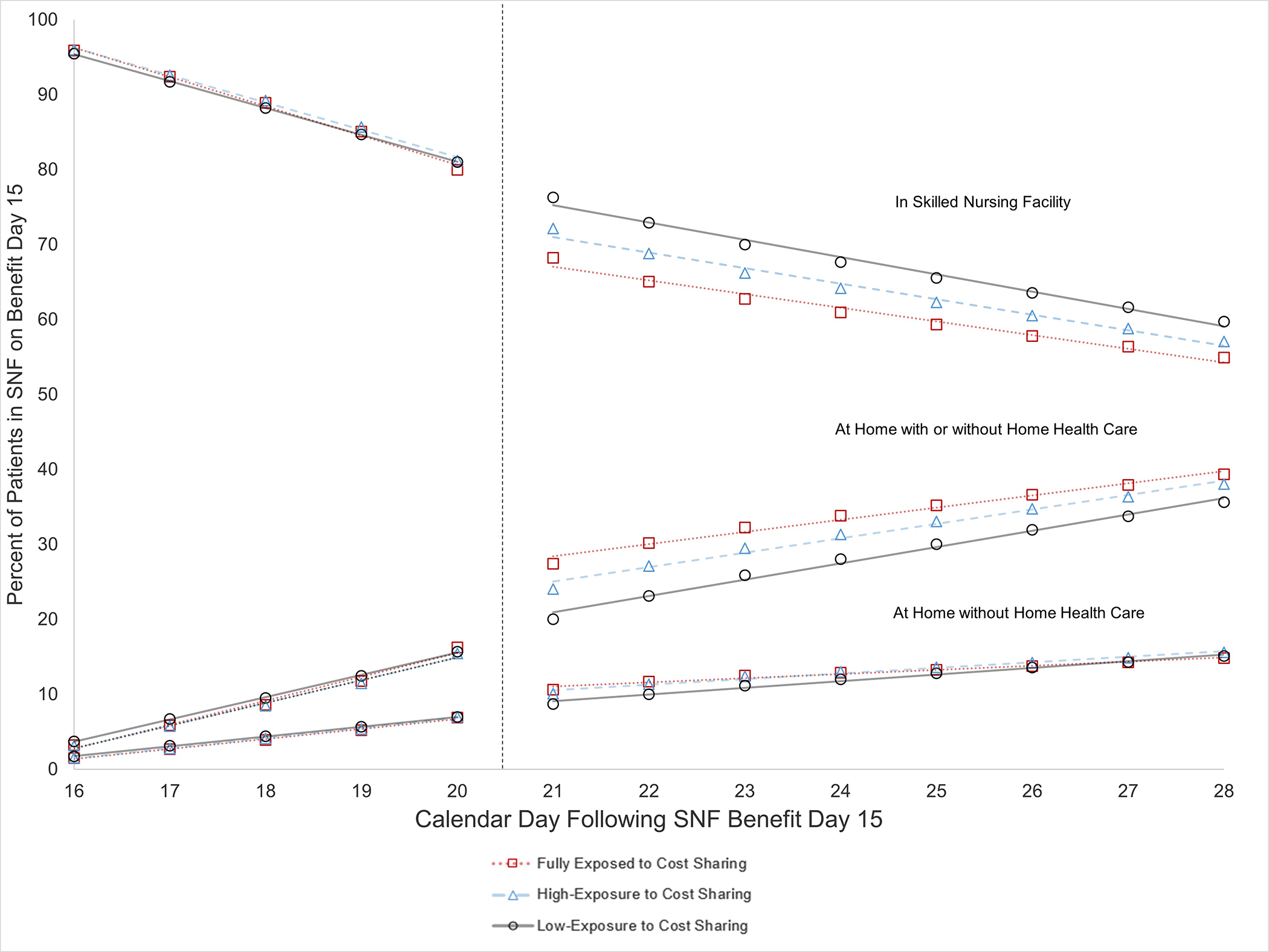

Corresponding to these discharge spikes, the proportion of the full-exposure group remaining in a SNF sharply dropped by 9.24 percentage points (95% Confidence Interval [CI]:−9.61,−8.86) on day 21 (the sixth calendar day following benefit day 15), and the proportion at home sharply increased by the same amount, including a 2.83 percentage points (95% CI:2.69,2.97) increase in the proportion home without home health care (Exhibit 3). Discontinuities in location followed a similar pattern among patients in the high-exposure group and were smaller in magnitude in the low-exposure group (Exhibit 4, A12).12 On average for the full-exposure and high-exposure groups combined, the discontinuous reduction in the proportion in a SNF was 5.8 percentage points greater than for the low-exposure group.

Exhibit 3. Effects of Discharges Induced by Cost Sharing on Patient Location.

Source: Authors’ calculations using fee-for-service Medicare claims data.

Notes: SNF = Skilled Nursing Facility. Location of patients who were in a SNF on benefit day 15 is plotted by subsequent calendar day (numbered from 16–28 for ease of interpretation) with fitted lines from regression discontinuity models. The adjusted percentage of patients in a SNF, at home instead of an acute or post-acute facility), and at home without home health care is presented for groups with different exposure to cost sharing after benefit day 20. The vertical dashed line indicates the initiation of patient cost sharing for those who remain in the SNF. See Exhibit A12 for corresponding regression discontinuity estimates.

Exhibit 4.

Effects of Cost Sharing and Early Discharge Due to Cost Sharing on Patient Outcomes

| Patient Outcome | Baseline Daily Rate | Unadjusted Baseline Difference | Effect of Exposure to Cost Sharinga | Effect of Early Discharge due to Cost Sharinga,c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of patients experiencing outcome on calendar day 19 in more exposed cohort, % | Mean difference in daily rate from calendar day 16–19 between more vs. less exposed cohort, percentage points | Difference-in-differences estimate of effect on daily rate,b percentage points | Rescaled to cumulative effect on outcome occurring by calendar day 28 associated with one fewer day in a SNF, percentage points | |

| Death | 0.22 | 0.026**** | −0.007 | −0.14 |

| All-cause hospitalization | 0.79 | 0.049**** | 0.019* | 0.29 |

| Hospitalization or death | 0.99 | 0.073**** | 0.008 | 0.12 |

| Fall-related hospitalizationd | 0.03 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.03 |

Source: Author’s analysis of fee-for-service Medicare claims data

Notes:

SNF= skilled nursing facility

p<0.10

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Estimates reflect changes within nine days after the discharge spike at SNF benefit day 20

Estimates for the daily rate of all-cause hospitalization refer to the differential change from days 16–19 to days 22–28 for patients who were more vs. less exposed to cost sharing, omitting days 20–21 because direct transfers from SNFs to hospitals on those days resulting from cost sharing do not reflect unsafe discharges to home (see Exhibit A17 confirming increases in hospitalizations on days 20–21 were coded as facility-to-facility transfers).12 Estimates for death and fall-related hospitalizations, which were not subject to this limitation in interpretability, reflect the differential change from days 16–19 to days 20–28. Day 15 is excluded because we required patients to be in a SNF on day 15, but not other days, to be included in the sample.

Approximated by dividing the effect of exposure to cost sharing on the cumulative incidence of the outcome through day 28 (3rd column multiplied by 9 or 7 days, depending on the outcome) by the effect of exposure on the mean number of days spent in a SNF through day 28 (0.45 fewer days).

Fall-related injury hospitalizations are identified using the following ICD codes in either the primary or secondary diagnosis field: e880, e881, e882, e884, e885, e888, 800–848, 850–854, 920–924.

Receipt of hospice care discontinuously increased on day 21 more in the full- and high-exposure groups than in the low-exposure group (Exhibit A11).12 Results differed minimally when treating long-term care facilities as a separate category from home (Exhibits A13–14), when not adjusting for patient characteristics, and with alternative model specifications (Exhibit A16).12 In supplementary analyses, discharge spikes in the full- and high-exposure groups were larger for patients with lower health risk and lower-income groups (Exhibits A6–10).12

Effects of Cost Sharing Exposure and Earlier Discharge on Outcomes

On average for the combined exposed group (full- and high-exposure), the cumulative number of days spent in a SNF over the day 20–28 period was differentially reduced by 0.45 days relative to the low-exposure group. This suggests a drastic reduction in length of stay among those discharged due to cost sharing. For example, if this difference were attributable entirely to the 5.8 percentage-point differential shift out of SNFs on day 20 for the combined exposed cohort, a 0.45-day difference would suggest that those discharged early to avoid cost sharing spent 7.8 fewer days in a SNF (0.45/0.058) from day 20–28.

Greater exposure to cost sharing was not associated with a statistically significant differential change in daily rates of mortality, hospitalization for a fall-related injury, or all-cause hospitalization (Exhibit 4, A17), though the latter neared statistical significance (P=0.053).12 When rescaled to reflect the effect of earlier discharge, the 0.019 percentage point differential increase in daily all-cause hospitalization rate due to cost-sharing exposure corresponded to a 0.29 percentage-point increase in the cumulative incidence of hospitalization over the day 22–28 period resulting from one fewer SNF day ([0.019×7 days]/0.45 days), or a 2.0 percentage-point increase resulting from a 7-day reduction in length of stay (Exhibit 4); in other words, hastening discharge by a week did not affect rehospitalization by day 28 for 98% of patients discharged early. In an exploratory analysis, we found evidence that at least some of this increase was for conditions that generally should not be caused by earlier discharge and can be treated in a hospital or SNF (e.g., UTIs or cellulitis) (Exhibit A21).12

We observed a small increase in transfers from SNFs to hospitals on days 20–21 that accounted for <1.0 percent of the increase in discharges on day 20 (Exhibits A20);12 we could not quantify subsequent transfers induced by cost sharing. In an analysis of a composite indicator of hospitalization or death, much of the non-significant increase in hospitalization was offset by a non-significant decrease in mortality associated with exposure to cost sharing (Exhibit 4). For all outcomes, trends in daily rates prior to day 20 did not differ between comparison groups and were visually similar (Exhibit A17, A19).12

DISCUSSION

Shortened SNF Stays and Patient Safety

Despite marked shortening of SNF stays by cost-sharing, we found no clear evidence that earlier discharge home significantly compromised patient safety. Discharges prompted by cost sharing shifted patients almost entirely to home, including a substantial proportion discharged home without home health care (30 percent of the shift to home) and thus without ostensible need for continued rehabilitative therapy or skilled nursing care.

The large reductions in SNF length of stay of more than a week also were not associated with a significant increase in mortality or hospitalization for fall-related injuries within 9 days of the day-20 discharge spike. As an upper bound on adverse consequences requiring a hospitalization, the results for all-cause hospitalization suggest that at most a small percentage of patients whose SNF stays were markedly shortened were harmed and hospitalized as a result, a finding that was not statistically significant and was diminished further in importance by the largely offsetting non-significant reduction in mortality. We also found a discontinuous increase in hospice use associated with exposure to cost sharing, suggesting that SNFs may delay end-of-life care discussions and referrals to hospice when incentives to lengthen stays go unchecked.

Although we lacked data on other clinical outcomes and may have missed some adverse consequences of earlier discharge, these findings taken together suggest substantial potential for SNF stays to be safely shortened. Our findings are consistent with evidence that SNF stays are often excessively long and with early success by risk-bearing providers in curtailing SNF stays without adverse consequences evident so far.3–6,14 Our results are inconsistent with one study concluding that shortening SNF stays meaningfully worsens outcomes based on an increase in all-cause hospitalization.11 In comparison with that study, our study found a smaller increase in all-cause hospitalization associated with earlier discharge, demonstrated it to be an upper bound on adverse events requiring hospitalization, additionally examined mortality and fall-related hospitalizations, and was robust to checks of inferential assumptions.

Policy Implications

Our findings are consistent with the notion that post-acute care can be safely transitioned from a SNF to home earlier in the recovery period for many patients, and suggest that efforts by risk-bearing providers in alternative payment models to limit SNF length of stay are well founded. Although the merits of innovation in home-based post-acute care are beyond the scope of our study, our results do suggest opportunities for more efficient post-acute care delivery, as current lengths of facility stays may not be necessary to ensure patient safety.

Relative to our findings, new payment models that incentivize providers to use SNF care more judiciously may pose less risk of adverse consequences than patient cost sharing. Whereas demand-side cost-sharing can lead to reductions in both appropriate and inappropriate care because patients may not be well informed, supply-side incentives for better-informed providers might reduce inappropriate care more selectively. In other words, our findings do not generalize to supply-side interventions directly, or exclude their potential for harm, but do support their rationale.

In conclusion, our findings are consistent with overuse of SNF care in fee-for-service Medicare, and contribute to the empirical basis for policies targeting unnecessary use of institutional post-acute care while monitoring for adverse consequences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (P01AG032952). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Post-Acute Care. Washington, DC: June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Medicare’s post-acute care: Trends and ways to rationalize payments. Washington, D.C.2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newhouse JP, Garber AM. Geographic variation in health care spending in the united states: Insights from an institute of medicine report. JAMA. 2013;310(12):1227–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McWilliams JM, Gilstrap LG, Stevenson DG, Chernew ME, Huskamp HA, Grabowski DC. Changes in postacute care in the Medicare Shared Savings Program. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2017;177(4):518–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McWilliams JM, Hatfield LA, Landon BE, Hamed P, Chernew ME. Medicare spending after 3 years of the Medicare Shared Savings Program. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;379(12):1139–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnett ML, Wilcock A, McWilliams JM, et al. Two-Year Evaluation of Mandatory Bundled Payments for Joint Replacement. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(3):252–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dummit LA, Kahvecioglu D, Marrufo G, et al. Association between hospital participation in a Medicare bundled payment initiative and payments and quality outcomes for lower extremity joint replacement episodes. Jama. 2016;316(12):1267–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Werner RM, Coe NB, Qi M, Konetzka RT. Patient outcomes after hospital discharge to home with home health care vs to a skilled nursing facility. JAMA internal medicine. 2019;179(5):617–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rose L The Effects of Skilled Nursing Facility Care: Regression Discontinuity Evidence from Medicare. American Journal of Health Economics. 2020;6(1):39–71. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin GZ, Lee A, Lu SF. Medicare Payment to Skilled Nursing Facilities: The Consequences of the Three-Day Rule. National Bureau of Economic Research;2018. 0898–2937. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Werner RM, Konetzka RT, Qi M, Coe NB. The impact of Medicare copayments for skilled nursing facilities on length of stay, outcomes, and costs. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(6):1184–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.To access the Appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online.

- 13.Hoffman GJ, Hays RD, Shapiro M, Wallace SP, Ettner SL. Claims-based identification methods and the cost of fall-related injuries among US older adults. Medical care. 2016;54(7):664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandra A, Dalton MA, Holmes J. Large increases in spending on postacute care in Medicare point to the potential for cost savings in these settings. Health Affairs. 2013;32(5):864–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.