Skin prick test (SPT) is a vital tool to confirm sensitization in allergic diseases, making it a daily routine for allergists. Although SPT is not considered an aerosol-generating procedure, the close contact between the patient and the performer may pose a risk for transmitting the disease.1 For Turkish health care facilities, the first phase of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic started with identifying the first case and continued by a quarantine period (QP), declared at the end of March 2020. At the beginning of June 2020, the Turkish government initiated the second period and named it the “normalization period” (NP).2 We aimed to compare the situation and behavior of allergists between the 2 phases of the COVID-19 pandemic.

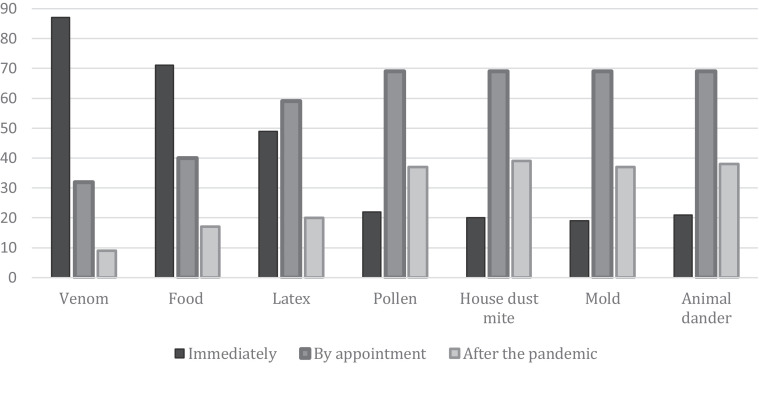

This study is an online survey-based, cross-sectional study conducted between June 20, 2020, and June 28, 2020. Participants were recruited through e-mails and WhatsApp. To our knowledge, this survey presents the first data of allergists’ approaches to performing SPTs during the COVID-19 pandemic. The health care system in Turkey is mainly socialized. Turkey is administratively divided into 81 provinces, but only 33 have at least 1 allergist working. The survey was sent to nearly 300 allergists, and 128 responded by filling the questionnaire; so, we believe that the results of this study are sufficient to represent our country. The participants were from 28 different provinces in Turkey. A total of 55 of the respondents (43%) were pediatric allergists. In the QP, nearly half of the participants had to shut down the SPT laboratories and one-third of them had to work in pandemic outpatient clinics. The ratio of participants who continued to perform SPTs in the QP was 54%. Of all the participants, 16% stated that their prick test laboratories were moved to a different place in their hospital. In the QP, 60% of the participants stated that they were very concerned on the risk of transmission during SPT. Despite wearing masks, 60% of the participants were anxious on being face-to-face with a patient for 15 minutes. Hospital and personal phones were the most preferred methods of telecommunication. There were 43% of the participants who preferred to perform all SPTs by appointment, 36% suggested a partial appointment system, whereas 21% did not consider it necessary to have an appointment system. In addition, 90 (71%) participants considered that the test intervals should be at least 30 minutes. When asked on the diagnostic value of the SPT for the treatment of allergy during the pandemic, 29% answered SPT to be very important, whereas 51% of the participants considered it of moderate importance. Of the participants, 76 (60%) stated that they would prefer to order specific immunoglobulin E tests more than they usually do. Furthermore, 87 participants said that they would prioritize testing with venom, 71 with food allergens, and 49 with latex (Fig 1 ). Priority given to food allergens was 65% among pediatric allergists and 34% among adult allergists. With the transition to the NP, the ratio of participants who had high anxiety on performing an SPT decreased from 60% to 30%.

Figure 1.

The answers of the respondents to the “Please select your timing preference for performing a skin prick test regarding allergens during the pandemic.” The top priority was attributed to the venom allergen (n = 87), followed by food allergens (n = 71) and latex (n = 49).

The European COVID-19 outbreak position document recommends that SPT should be generally suspended or replaced by laboratory tests during the pandemic except for some individual cases.1 In our questionnaire, most participants attributed importance to venom allergy and, especially, pediatric allergy specialists gave more priority to food allergens by stating that they would continue to perform skin prick tests with these allergens despite the pandemic. Owing to the urgent nature of these allergies, we consider this result an excellent and practical example of a careful risk-benefit assessment, which the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology and Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma has mentioned.1 More than half of the participants preferred to perform an SPT at least 30 days after treatment completion of COVID-19 in a patient. In other words, participants did not want to test even if the official quarantine period was over.

One consequence of the pandemic is the increased exposure to disinfectants. The American Nurses’ study revealed that poor asthma control was associated with exposure to formaldehyde, hypochlorite bleach, and hydrogen peroxide but not with exposure to alcohol-based disinfectants.3 Most participants chose chlorine-containing disinfectants for the floors and alcohol-based disinfectants for the surfaces of seats and desks. We consider this result to be according to the recommendations of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that advise patients to choose disinfectants that are less likely to cause an asthma attack, such as products with ethanol (ethyl alcohol).4

We found that only one-third of the participants had a written action plan. This low result is likely to be related to the fact that the survey was conducted at the beginning of the pandemic for our country. The World Health Organization shares daily information on the number of coronavirus cases for countries.5 Following this information may help adjust allergy clinics by predicting the pandemic course in the upcoming time. Basic reproductive rate (R0) is the average number of people infected by 1 person in a susceptible population.6 For Turkey, R0 was below 1 in the NP, and we revealed in our study that physicians felt less anxious when performing an SPT during this period. An implication of our result to clinical practice may be the possibility of approaching SPTs according to the R0 ratio. In this sense, an R0 ratio below 1 may refer to continuing normal operations. In contrast, an R0 ratio above 1 may refer to postponing SPTs similar to the stratified approach mentioned by Shaker et al7 in a special article on pandemic contingency planning for allergy clinics.

Our suggestion, because it would not be practical to suspend all SPTs for long periods, is that the decision on prioritization of testing should be made carefully. For instance, SPT with venom and food extracts may be done more urgently than others. Proper measures, such as universal masking and effective triage, to create a safer environment are needed. Performing SPTs by appointment would be reasonable. The primary limitation of this study is the lack of effective, sustainable, or verified data backing up our findings. Therefore, we suggest that further studies are needed to validate our recommendations.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Funding: The authors have no funding sources to report.

References

- 1.Pfaar O, Klimek L, Jutel M, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: practical considerations on the organization of an allergy clinic—an EAACI/ARIA position paper. Allergy. 2021;76(3):648–676. doi: 10.1111/all.14453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guide on working in healthcare institutions during the normalization period in COVID-19 pandemic. Study by Scientific Advisory Board, Republic of Turkey Ministry of Health. 2020. Available at: https://covidlawlab.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Guide-to-working-in-healthcare-institutions-during-normalization-.pdf. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- 3.Dumas O, Wiley AS, Quinot C, et al. Occupational exposure to disinfectants and asthma control in US nurses. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(4) doi: 10.1183/13993003.00237-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. People with moderate to severe asthma. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/asthma.html. Accessed November 28, 2020.

- 5.World Health Organization. Infection prevention and control guidance for long-term care facilities in the context of COVID-19: interim guidance, 21 March 2020. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331508/WHO-2019-nCoV-IPC_long_term_care-2020.1-eng.pdf. Accessed November 29, 2020.

- 6.Li Y, Campbell H, Kulkarni D, et al. The temporal association of introducing and lifting non-pharmaceutical interventions with the time-varying reproduction number (R) of SARS-CoV-2: a modelling study across 131 countries. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(2):193–202. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30785-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaker MS, Oppenheimer J, Grayson M, et al. COVID-19: pandemic contingency planning for the allergy and immunology clinic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(5) doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.03.012. 1477-1488.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]