Abstract

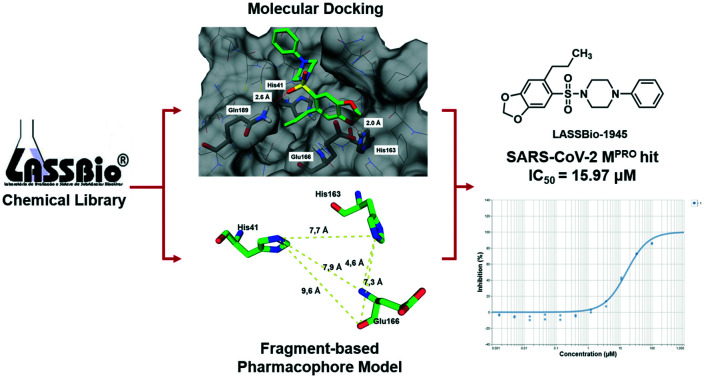

In December 2019, an infectious disease was detected in Wuhan, China, caused by a new pathogenic coronavirus, named SARS-CoV-2. It spread very rapidly, and on March 11th of 2020, the outbreak was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization. Currently, effective treatment options remain limited. SARS-CoV-2 enzyme main protease (MPRO) plays a pivotal role in the viral life cycle, making it a putative drug target. In order to identify suitable hits to develop inhibitors with adequate antiviral properties, we explored the LASSBio Chemical Library employing multiple strategies of virtual screening. A fragment-based pharmacophore model enabled the identification of key interactions involved in the molecular recognition at the catalytic site of MPRO, namely, with amino acid residues His41, His163 and Glu166. Docking-based virtual screening was performed, leading to the identification of LASSBio-1945 (9), a new hit of MPRO, presenting an IC50 = 15.97 μM. This compound, an 1,3-benzodioxolyl sulfonamide, represents an interesting starting point for subsequent hit-to-lead optimization steps and, to the best of our knowledge, a new distinct chemotype for MPRO inhibition.

A SARS-CoV-2 main protease (MPRO) inhibitor was discovered employing molecular docking and a fragment-based pharmacophore model as virtual screening strategies.

Introduction

In December 2019, an infectious disease (COVID-19) was detected in Wuhan, China, caused by a new pathogenic coronavirus (CoV), named SARS-CoV-2. In the past, two other pathogenic CoVs, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), both transmitted from animals to humans, have triggered global epidemics in 2003 and 2012, respectively.1

The new virus has been named SARS-CoV-2 because the RNA genome (GenBank ID: MN908947.3) is about 82% identical to that of SARS-CoV (GenBank ID: NC_004718.3);2 both viruses belong to clade b of the genus Betacoronavirus.3,4 SARS-CoV-2 spread very rapidly from China to all countries, and on March 11th of 2020, the outbreak was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO).5

Current disease management is limited to social measures, such as social distancing, travel ban, and lockdown in many regions. Thus, there is an urgent need for the discovery of prevention and treatment strategies for COVID-19. It is acknowledged that the introduction of a vaccine would happen, in the earliest, at the beginning of 2021. While the discovery of a new drug should take even longer, the drug repositioning approach,6i.e. the use of an existing drug to treat COVID-19, seems the fastest strategy since these compounds have either regulatory approval as drugs or have already cleared safety studies.7,8

Although several known drugs are currently under investigation,7,9 there is a clear need to identify other therapeutic alternatives within the drug repurposing approach. As illustrated by strategies employed to treat HIV nowadays, such as the highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the long-term management of endemic viruses normally includes the use of multiple antiretroviral drugs, interfering with different stages of the virus life-cycle, in an attempt to control infection and the appearance of resistance.10,11 Protease inhibition encompasses one of the strategies employed in HIV multi-therapy, and could be successfully mirrored in the treatment of COVID-19. SARS-CoV-2 presents a main protease (MPRO) that plays a pivotal role in mediating viral replication and transcription, making it an attractive drug target.12,13 Additionally, it has been demonstrated that the active site of MPRO remains highly conserved across different CoVs, suggesting the possibility of wide-spectrum anti-CoV drug design.14,15

In fact, some approaches towards the identification of antiviral agents acting as MPRO inhibitors have already been reported.15,16 In the context of drug repositioning, a combination of SARS-CoV-2 MPRO structure-based virtual screening and high-throughput screening of more than 10 000 compounds (containing approved drugs, clinical trials, and other active substances) identified six compounds as promising MPRO inhibitors (IC50 range: 0.67–21.4 μM). Among these identified inhibitors, disulfiram and carmofur are FDA-approved drugs, whereas ebselen, tideglusib, shikonin, TDZD8 and PX-12 are currently under preclinical studies.16

In another study, a combined strategy employing structure-based drug design, virtual screening and high-throughput screening identified N3, a Michael acceptor inhibitor of MPRO of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, as a potential SARS-CoV-2 MPRO inhibitor. Corroborating the high conservation of the active site of MPRO across different CoVs, N3 was shown to form a covalent bond with and to be an irreversible inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 MPRO.15

In the same study, ebselen was identified as a SARS-CoV2 MPRO inhibitor after a high-throughput screening approach. Ultimately, in a plaque-reduction assay with simian Vero cells infected with SARS-CoV-2, N3 and ebselen displayed antiviral and cell protection efficacy at EC50 values of 16.77 μM and 4.67 μM, respectively,15 demonstrating their antiviral potential against SARS-CoV-2.

In this work, we developed a screening strategy to identify MPRO ligands within the LASSBio Chemical Library (LCL),17 in order to provide a suitable chemical starting point to develop novel inhibitors with adequate antiviral properties. A fragment-based pharmacophore model was created to identify key interactions involved in the molecular recognition at the catalytic site of MPRO by analysing the fragments previously obtained by the Diamond Light Source researchers.18 Afterwards, molecular docking-based virtual screening on MPRO with the LCL was performed. Next, the information generated by the fragment-based pharmacophore model was employed to assist the analysis of the docking poses, thus refining our final ranking. Additionally, this contribution complements the work done by the Diamond Light Source researchers by focusing the analysis on the non-covalent fragments identified by them and, therefore, it is our hope to collaborate with the worldwide efforts to deliver a strategy that can enhance the success rate of attempts to provide novel therapeutic agents to treat COVID-19.

Results and discussion

Fragment-based pharmacophore model

The fragment-based pharmacophore model (FBPM) was developed based on the fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD) strategy. The latter is a well-established approach that has been applied to identify fragment-sized hits to provide novel chemical starting points that can be further optimized for the desired molecular target.19 As fragments have low molecular weights (MWs), they are perfect for probing the most important interactions at the whole active site of a given target, resulting in structural insights about how to increase, fuse or merge these fragments into more potent ligands of higher MW.20,21 With this in mind, we figured out that this information could also be used to identify key amino acid residues in the molecular recognition process, allowing the identification of the most important pharmacophore points of interaction. Then, we could use this knowledge to improve our analysis of the poses generated by the docking in the virtual screening stage.

To build the FBPM, we analysed the 22 non-covalent fragments‡ (detailed in the ESI†) co-crystallized with MPRO by the Diamond research group.18 Considering that the vast majority of LCL compounds were designed as non-covalent ligands, the decision to use only non-covalent fragments was adopted.

Initially, the interactions and crystallographic binding poses of each fragment were individually analysed, aiming to identify if there were patterns of interaction that could highlight specific amino acid residues and/or types of interactions (Table S1, ESI†). Curiously, none of the 22 fragments interacts with MPRO through ionic interactions. After mapping out all the interactions, it became clear that residues His41, His163 and Glu166 interacted more frequently than the others. Glu166 was the higher frequency interacting residue, mainly performing hydrogen bonding by means of its backbone and also forming water-mediated interactions, with its side chain carboxylic acid oriented towards the exterior part of the active site (Fig. 1A).

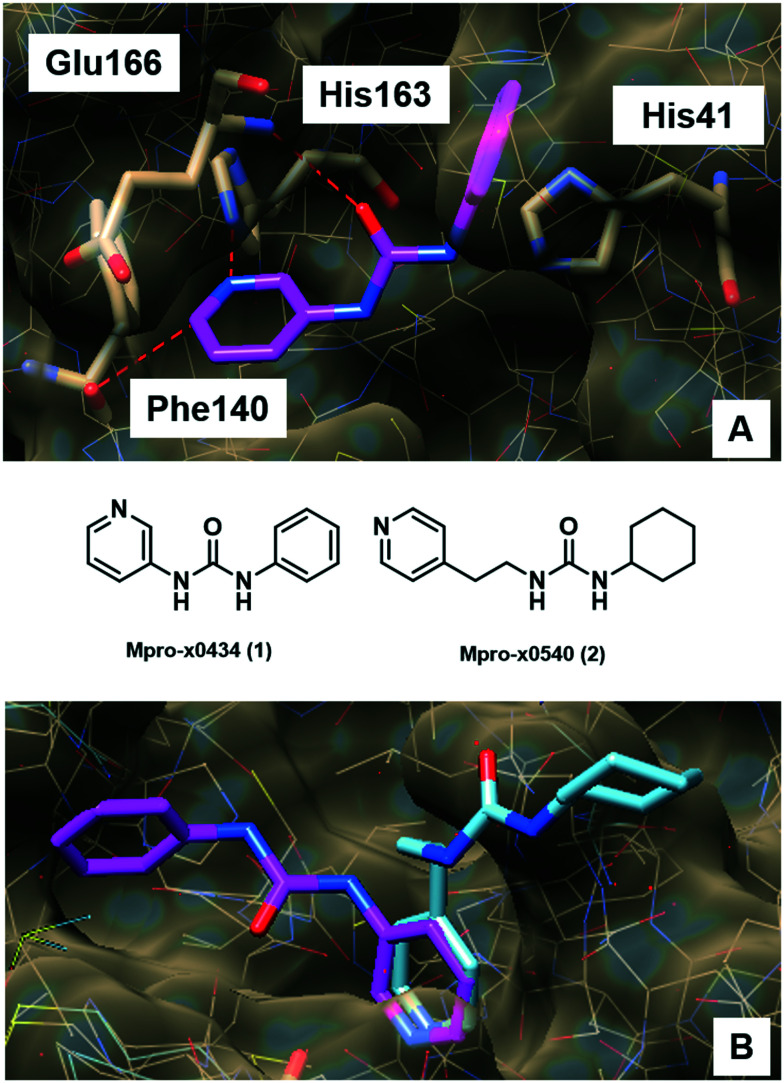

Fig. 1. A) Fragment x0434 (1, magenta) at the MPRO active site and its interactions with His41, Phe140, His163 and Glu166. Hydrogen bonds are shown as red dashed lines. B) Fragments x0434 (1, magenta) and x0540 (2, cyan) superimposed at the MPRO active site. Slight structural changes and differences in the linker size resulted in significantly different binding modes. These images were generated using UCSF Chimera.22.

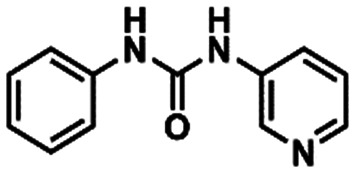

Interestingly, His41 and His163 presented unique and distinct behaviours. His41 was the only residue identified in the active site able to perform π–π stacking interaction with molecular fragments, and it seems to prefer hydrophobic contacts rather than interactions of more polar nature. On the other hand, His163 only interacted through hydrogen bond formation with the fragments, mostly as a hydrogen bond donor. We could also observe that, in most cases, a “convenient” non-classical hydrogen bond with the backbone of the Phe140 residue occurred together with the interaction with His163 (Fig. 1A). This probably happened because of the specific orientation needed by the fragment to interact with His163 which, in turn, projected the electron-deficient hydrogen bonded to the carbon adjacent to the nitrogen to the carbonyl of the Phe140 backbone, favouring this interaction. As mentioned, the interaction with His163 seems to demand a specific orientation inside the MPRO site, because even slight structural changes among the fragments that interact with this residue result in different conformational binding orientations (Fig. 1B). Apparently, adopting the conformation that allows for this specific hydrogen bond formation is preferred, indicating that interacting in this fashion with His163 and Phe140 could be a pharmacophoric feature in the molecular recognition process. The way fragment x540 (2) binds corroborates this hypothesis since it orientated its cyclohexyl-urea subunit towards the exterior of the active site in order to adopt the most adequate orientation to allow the pyridine ring to interact properly with His163 instead of trying to occupy other parts of the active site to interact with additional residues at the expense of a not so ideal orientation to interact with His163 (Fig. 1B).

Another relevant observation was that fragments interacting with His41 did not interact with His163 and vice versa. The only exception was fragment x0434 (1), which interacted with both His41 and His163 (Fig. 1A). This indicated that there were two subgroups of fragments, and two clear distinct regions inside the active site of MPRO to be explored during the molecular design. Additionally, this signalled that in order to interact with both His41 and His163 a ligand would need to display an optimal distance between the respective interacting subunits. With this in mind, the fragments were also analysed regarding (i) the presence of subunits able to interact with His41 and His163; (ii) the size of the linker between these subunits, and (iii) the distance between the central atom of the linker and both subunits (Table S2, ESI†). This analysis suggested that in order to interact simultaneously with His41 and His163, the fragment needed to have a linker of no more than 3 atoms (approximately 2.50 Å) and the optimal distance between the central atom of the linker and the atom interacting as a hydrogen bond acceptor in the aromatic subunit occupying the His163 site was ca. 4.40 Å. The distance of 3.85 Å was the optimal between the central atom of the linker and the centroid of the aromatic subunit interacting with His41, while keeping the adequate orientation to interact with His163 (Table S2, ESI†). These findings corroborate why fragments x0434 (1) and x0540 (2) display such diverse binding orientations. Despite the flexible nature of the linker in 2, it is too long (4.46 Å – five atoms) to accommodate both rings inside the active site (Fig. 1B).

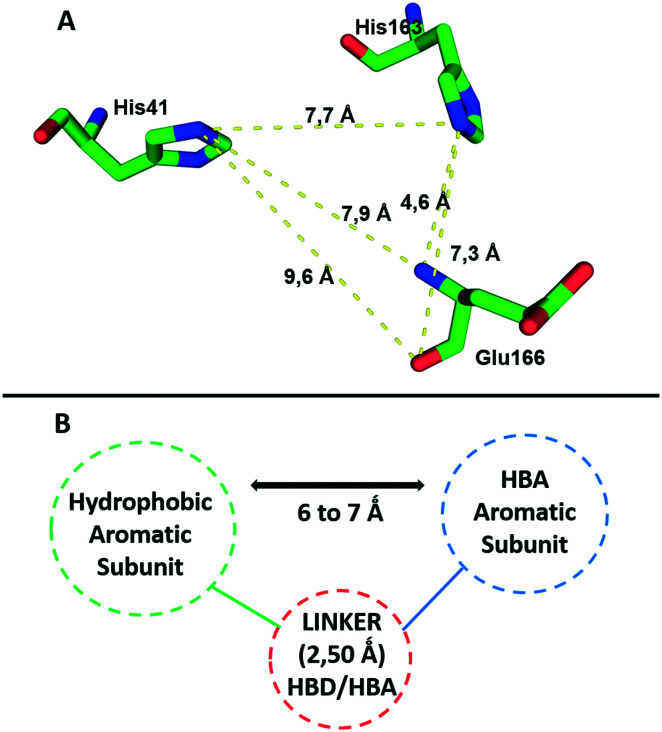

All these features resulted in the building of the 3D pharmacophore model based on residues His41, His163 and Glu166 as pharmacophoric points for the establishment of an energetically favoured binding complex (Fig. 2A). By molecular complementarity, a potential ligand would need to present a hydrophobic aromatic subunit to interact with His41 via π–π stacking, a second aromatic subunit bearing a hydrogen bond acceptor to interact with His163, and a linker that can interact with Glu166 through H-bonding, and that can also provide a distance in the range of 6–7 Å between the atom interacting as a hydrogen bond acceptor with His163 and the aromatic subunit interacting with His41 (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. A) Pharmacophore model based on residues His41, His163 and Glu166 as the key points of interaction required for molecular recognition by MPRO. B) Suggested pharmacophore points, spatial orientation and distances needed for interactions with the key residues by a potential ligand. HBA – hydrogen bond acceptor; HBD – hydrogen bond donor.

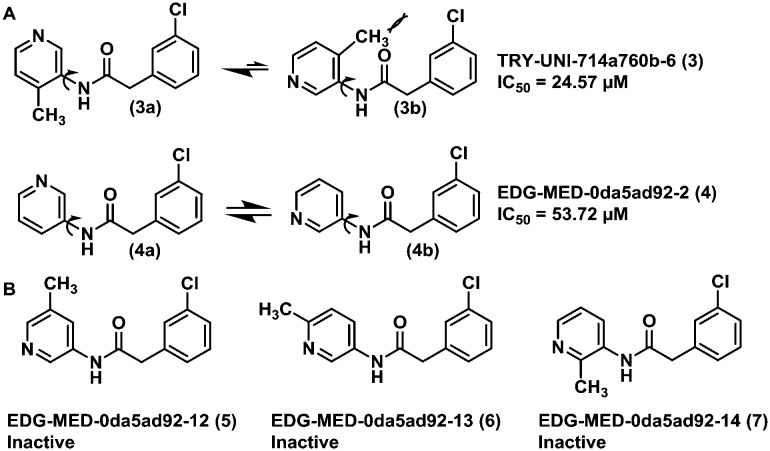

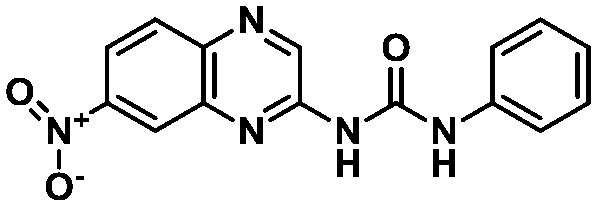

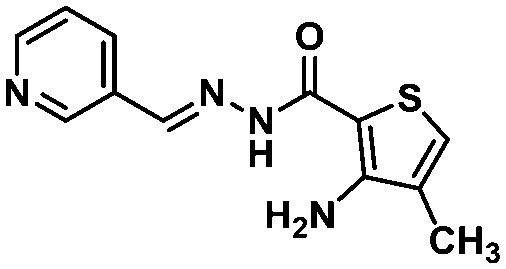

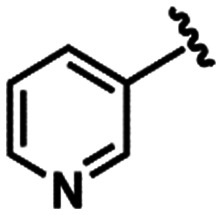

The fragment screening performed by the Diamond Light Source group is part of an international initiative called COVID Moonshot.23 After the fragments were published, the following actions of the initiative were crowdsourcing molecular designs inspired by these fragments, synthetizing and testing the most promising compounds submitted. Some of these results have already been released in their platform,24 which allowed us to evaluate the hypothesis of our FBPM against some experimental data from non-covalent MPRO inhibitors. These experimental data confirm our suggestion that the His163 residue interacting as a hydrogen bond donor is important for the molecular recognition process and formation of the binding complex. This is illustrated by the activities displayed by compounds TRY-UNI-714a760b-6 (3) (IC50 = 24.57 μM) and EDG-MED-0da5ad92-2 (4) (IC50 = 53.72 μM). The subtle insertion of a methyl group in position 6 of the 3-pyridine ring was able to promote a 2-fold increase in MPRO inhibition,25 probably due to the induction of a favourable pyridine ring conformation for the interaction with His163 (Fig. 3A). This conformational effect induced by the methyl group is confirmed by other related isomers, where the methyl group was introduced at other positions of the pyridine ring, and all were found to be inactive (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. A) Conformational effect of the methyl group on the pyridine ring orientation of compounds 3 and 4, demonstrating how the orientation of the nitrogen is key for interaction with His163 and enhances MPRO inhibition. B) Closely related methyl-substituted isomers (5–7) that displayed no activity against MPRO, confirming the importance of the conformational effect.

The preference of His41 for interacting with more hydrophobic subunits is another feature of the pharmacophore model in agreement with the experimental data released by the Moonshot initiative. It suggests a relationship between the increase in the lipophilic character of the aromatic ring that interacts with His41 and a higher MPRO inhibition (Fig. S2, ESI†). It was delightful and reassuring to acknowledge that some of the pharmacophore model's key interaction hypotheses were supported by the experimental data disclosed so far. The next step of this work consisted of applying the information provided by the pharmacophore model to the analysis of the virtual screening results, which will be better detailed in the discussion of the molecular docking results.

Molecular docking-based virtual screening

The LASSBio Chemical Library (LCL) contains ca. 2300 compounds and the library content selection has been driven by medicinal chemistry concepts, with focus on designing compounds with the most adequate lead-like and/or drug-like properties.26–28 For instance, approximately 85% of these compounds are compliant with Lipinski's Ro5, and 95% with Veber's rules.29,30 Some of the compounds in the LCL have shown in vivo activities in one or more animal models, after being administrated orally, which is an indication that they possess overall favourable bioavailability and, hence, adequate pharmacokinetic profiles. From the perspective of a virtual screening campaign, this appropriate profile provides an advantage in accelerating the steps of extensive filtering of huge libraries and, from the perspective of the drug development process, it may provide high quality hits that could progress more effectively into clinical candidates.

Along with rapid development of techniques for determination of biomacromolecules' structures, docking became an important approach of computer-aided drug design.31 Although docking is a well-established technique that contributes to the early drug discovery process, one of its flaws is the frequent false positives arising from ranking compounds based on biased scoring functions.32,33 Therefore, achieving a successful hit identification rate from a chemical library in a virtual screening campaign is also directly related to the combination of appropriate in silico strategies.34 In this context, the integration of both ligand and structure-based methods with visual inspection should be used to help the identification of a subset of compounds from a library to be tested on adequate pharmacological assays.35,36 Hence, ligand-based methods such as molecular similarity and substructure searches were implemented to complement molecular docking analysis.37

In this work, the GOLD (Genetic Optimization for Ligand Docking) program of version 5.8.1 (ref. 38) was employed for docking simulations. GOLD has four dimensionless fitness scores named GoldScore,39 ChemScore,40 ASP (the Astex Statistical Potential),41 and ChemPLP.42 Even though in each case the scale of the score is different, it is a guide as to how good the pose is, i.e. the higher the score, the better the docking result is likely to be. Given the fact that the scoring functions combined had better performance in redocking procedures when compared to each scoring function alone (Table S3, ESI†), rank-by-rank consensus scoring was also applied to aid the analysis of docking poses in this study.43

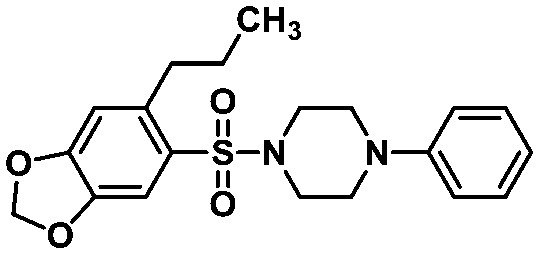

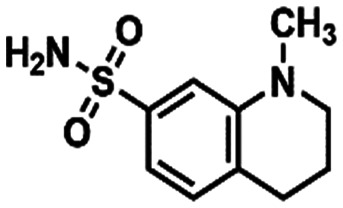

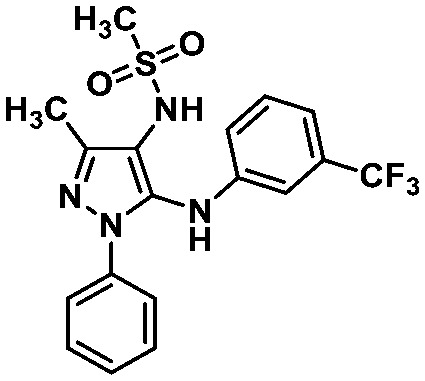

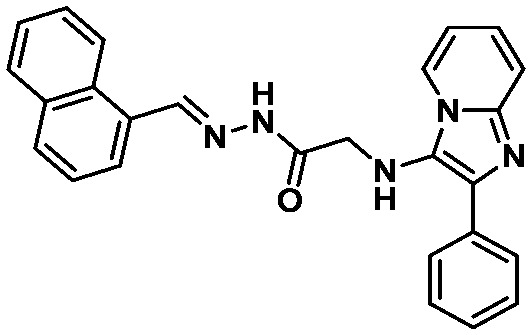

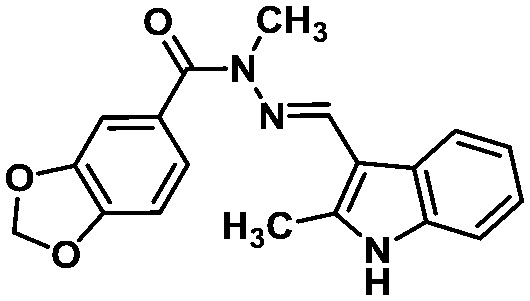

The developed pharmacophore model (Fig. 2) highlighted three residues mainly responsible for molecular recognition, i.e. His41, His163 and Glu166. These amino acid residues are located at two conserved pockets of the MPRO active site, on which His41 forms hydrophobic interactions, His163 acts as a hydrogen bond donor, and Glu166 acts either as a hydrogen bond donor or acceptor. This structural information was used as a criterion to analyse the docking poses of the compounds obtained from the molecular similarity search44 using the non-covalent co-crystalized fragments disclosed by the Diamond research group as queries (Scheme S1†). The established similarity coefficient cut-off of 0.4 led to the identification of LASSBio-1962 (8)45 and LASSBio-1945 (9)46 (Table 1), which were able to interact with the residues of the pharmacophore model. Additionally, the top 2% ranked LCL compounds were analysed according to the pharmacophore model, and compounds LASSBio-428 (10),47 and LASSBio-1615 (11)48 were selected.

Structures, ranking position or similarity coefficient, and nearest neighbour of the identified compounds of the LASSBio Chemical Library through docking-based virtual screening on SARS-CoV-2 MPRO.

| Compound | Ranking position | Similarity coefficient | Nearest neighbour |

|---|---|---|---|

LASSBio-1962 (8) LASSBio-1962 (8) |

— | 0.52 |

Mpro-x0434(1) Mpro-x0434(1) |

LASSBio-1945 (9) LASSBio-1945 (9) |

— | 0.42 |

Mpro-x0195 (12) Mpro-x0195 (12) |

LASSBio-428 (10) LASSBio-428 (10) |

2 | — | — |

LASSBio-1615 (11) LASSBio-1615 (11) |

24 | — | — |

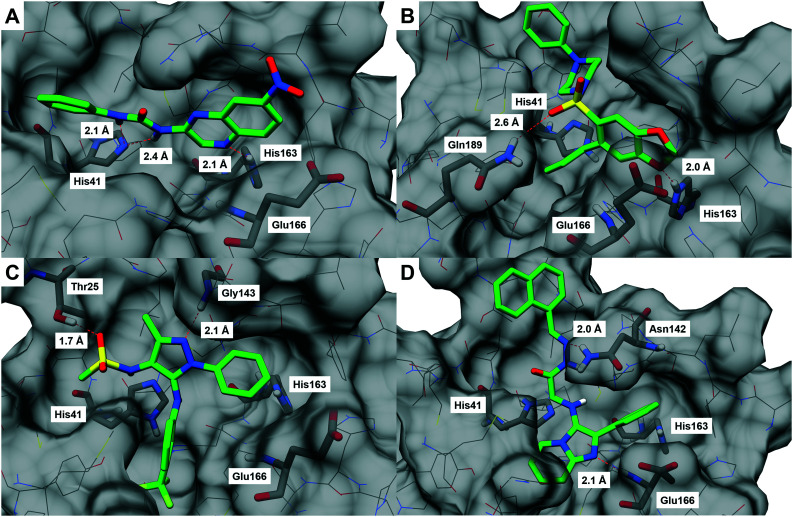

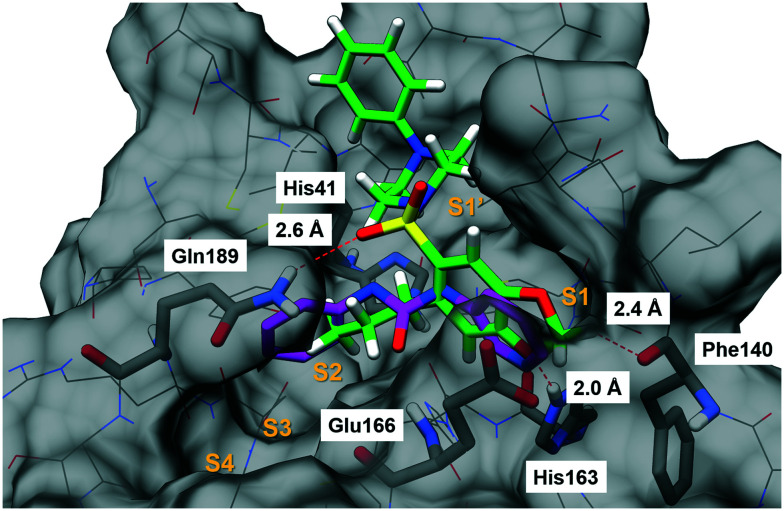

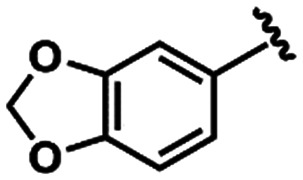

The binding modes of the compounds selected by the molecular similarity search (8–9) illustrated the general molecular recognition pattern (Fig. 4) of the identified compounds in Table 1. The compounds occupied the pocket near His163, as depicted by the binding mode of LASSBio-1962 (8). In addition, LASSBio-1945 (9) was also able to occupy the pocket near His41. LASSBio-1962 (8) shares some degree of similarity with x0434 (1) and forms a H-bond with His163 using the quinoxaline system. However, probably due to the nature of the bicyclic ring, the distance for H-bonding with this residue is increased for 8 (2.1 Å), when compared to 1 (1.7 Å), which might also reflect the inability of the same linker to adopt a conformation similar to 1 and interact with Glu166 (Fig. 4A). However, the urea linker was able to form a bidentate H-bond with His41, suggesting that it could still bind to the active site. On the other hand, the docking pose of LASSBio-1945 (9) (Fig. 4B) suggests that the oxygen atom in the 1,3-benzodioxole ring mimics the hydrogen bond acceptor interaction made by the pyridine nitrogen atom of 1, with the His163 residue. Additionally, the n-propyl side chain occupies the so-called S2 hydrophobic pocket, next to His41. X-ray diffraction studies of previously described peptide inhibitors of MPRO show that isobutyl,15 cyclopropyl,49 and cyclohexyl50 aliphatic side chains are able to occupy this pocket, supporting the binding mode depicted in Fig. 4B. The hydrogen bonding interaction between Gln189 and the oxygen of the sulphonamide group of LASSBio-1945 (9) may also contribute to its molecular recognition.

Fig. 4. Docking poses of (A) LASSBio-1962 (8),45 (B) LASSBio-1945 (9),46 (C) LASSBio-428 (10),47 and (D) LASSBio-1615 (11).48 The structure of SARS-CoV-2 MPRO is shown as lines and surface, with pharmacophore model residues and additional predicted interacting residues shown as sticks (carbon atoms in grey). Docked compounds are shown as sticks (carbon atoms in green). Hydrogen bonds are shown as red dashed lines. These images were generated using UCSF Chimera.22.

The binding mode of compounds selected from the top 2% illustrated that the structures which fitted in the His163 and His41 pockets scored higher. LASSBio-428 (10) and LASSBio-1615 (11) occupied both pockets with aromatic residues, of which 11 interacted with the 2-phenyl-imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine system, and 10 fitted the His163 pocket with its phenyl ring and the His41 pocket with the 3-trifluormethylaniline subunit. Even though these compounds were able to form H-bonds with amino acid residues in the binding site, none interacted with His163.

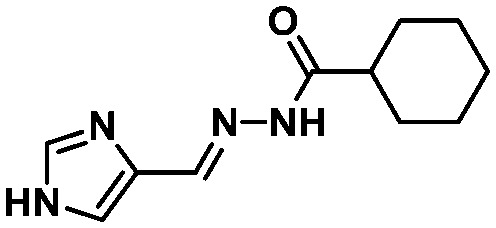

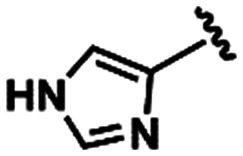

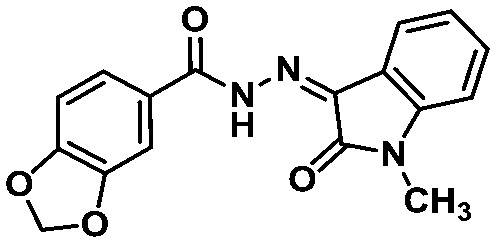

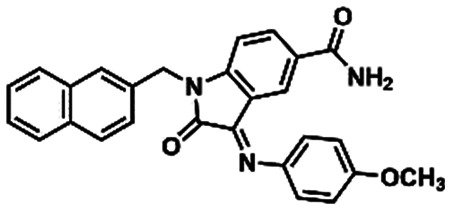

Due to the fact that the oxygen atom of the 1,3-benzodioxole moiety acted as a H-bond acceptor, interacting with the pharmacophoric residue His163, as it is depicted in the binding mode of LASSBio-1945 (9) (Fig. 4B), we performed further substructure-based searches in the chemical library (Table 2). Firstly, we searched for 1,3-benzodioxole derivatives, leading to the identification of LASSBio-1649 (13).51 Secondly, we defined pyridine and imidazole rings as queries based on pyridine co-crystallized fragments disclosed by Diamond Light Source (e.g.1, Fig. 1), and on co-crystallized imidazole inhibitors of SARS-CoV MPRO, in which the imidazole ring was able to interact with the conserved histidine residue equivalent to His163.52 In an attempt to identify additional chemotypes, a similarity search based on inhibitors of SARS-CoV MPRO, obtained from the scientific literature and patents available on the Integrity database, was also conducted (Table 2). After visual analysis based on the pharmacophore model (Fig. S3–S6, ESI†), LASSBio-1649 (13),51 LASSBio-1891 (14),53 and LASSBio-1600 (15)54 were selected as a result of searches using 1,3-benzodioxole, pyridine and imidazole subunits as queries, respectively. LASSBio-1652 (16)51 was selected from the similarity search which resulted in compound 17 (IC50 = 17 μM; MPRO SARS-CoV)55 as the nearest neighbour with a Tanimoto coefficient of 0.51 (Table 2).

Structures and query substructure or nearest neighbour of the identified compounds of the LASSBio Chemical Library through docking-based virtual screening on SARS-CoV-2 MPRO.

| Compound | Query | Compound | Query or nearest neighbour |

|---|---|---|---|

LASSBio-1649 (13) LASSBio-1649 (13) |

|

LASSBio-1600 (15) LASSBio-1600 (15) |

|

LASSBio-1891 (14) LASSBio-1891 (14) |

|

LASSBio-1652 (16) LASSBio-1652 (16) |

(17) (17) |

All these compounds belong to the class of N-acylhydrazones (NAHs), and this is probably due to the nature of the LASSBio Chemical Library. In fact, the NAH functional group is the major chemotype studied in LASSBio56 and, consequently, it is present in approximately 50% of the LCL compounds. In the particular example of 1,3-benzodioxole, which was also selected in the similarity search (LASSBio-1652, 16), it is an outcome of the continuous studies based on the use of safrole, an abundant Brazilian natural product and the principal chemical constituent of sassafras oil (Ocotea pretiosa).57 In conclusion, these additional searches allowed the identification of another four compounds (13–16) for investigation of potential MPRO inhibition.

Main protease (MPRO) inhibitory activity

The selected compounds in the virtual screening steps were assayed regarding their MPRO inhibition of enzymatic activity by employing the RapidFire High-Throughput Mass Spectrometry assay.58 Initially, these compounds were tested at 50 μM concentration and LASSBio-1945 (9), which presented a percentage of inhibition greater than 50%, had its full dose–response curve determined (Table 3).

IC50 values and percentage of inhibition at 50 μM concentration for MPRO enzymatic activity of the selected compounds in the RapidFire High-Throughput Mass Spectrometry assay.

| Compound | IC50 (μM) | Inhibition at 50 μM (%) |

|---|---|---|

| LASSBio-428 (10) | N.D. | −10.63 |

| LASSBio-1600 (15) | N.D. | −16.29 |

| LASSBio-1615 (11) | N.D. | 7.53 |

| LASSBio-1649 (13) | N.D. | −6.66 |

| LASSBio-1652 (16) | N.D. | −12.83 |

| LASSBio-1891 (14) | N.D. | −6.32 |

| LASSBio-1945 (9) | 15.97 | 68.26 |

| LASSBio-1962 (8) | N.D. | 0.77 |

As demonstrated in Table 3, this iteration of hit discovery allowed us to identify, among the eight compounds evaluated, compound LASSBio-1945 (9)46 as a MPRO inhibitor in the micromolar range (IC50 = 15.97 μM), which means a success rate of 12.5%.

While it was observed that the 1,3-benzodioxole subunit of LASSBio-1945 (9) could mimic the interaction pattern of the 3-amino-pyridinyl subunit of other MPRO inhibitors (Fig. 4B), it was intriguing to note that compounds LASSBio-1649 (13) and LASSBio-1652 (16), also bearing the 1,3-benzodioxole subunit, were inactive. One of the reasons might be the size of the linker of both compounds. The distances between the carbonyl and the imine carbon were 2.9 Å and 3.6 Å for LASSBio-1649 (15) and LASSBio-1652 (18), respectively.

As already discussed in the pharmacophore model section, the linker should not have more than 3 atoms (ca. 2.50 Å) in order to be able to interact simultaneously with His41 and His163. Probably, NAH derivatives 13 and 16 behave in the same way as fragment x0540 (2) (Fig. 1B), i.e. in order to accommodate the 1,3-benzodioxole moiety to interact with His163, they adopt a binding pose where the aromatic subunit supposed to interact in the His41 pocket is oriented towards another position within the active site, resulting in the loss of that additional, relevant interaction. This size of the linker issue could also be one of the factors contributing to the inactivity of compounds LASSBio-1891 (14) and LASSBio-1600 (15), since they also have the NAH linker, despite 15 being able to interact with His41 via hydrophobic interactions and with His163 acting as a hydrogen bond acceptor (Fig. S5, ESI†). The results of LASSBio-1962 (8) support the hypothesis that the interactions with both His163 and His41 are important for activity. Even though the docking pose suggests that 8 was able to interact with His163, LASSBio-1962 (8) was not able to form aromatic interactions with His41. In the cases of LASSBio-428 (10) and LASSBio-1615 (11), the absence of the H-bond interaction with His163 may be the reason for the inactivity.

In summary, these results uncover a potential bioisosteric relationship between the 1,3-benzodioxole moiety present in LASSBio-1945 (9) and the 3-amino-pyridinyl moiety displayed by several fragments, such as 1, TRY-UNI-714a760b-6 (3) (IC50 = 24.57 μM) and EDG-MED-0da5ad92-2 (4) (IC50 = 53.72 μM). The experimental results suggest that the interactions with the residues His41 and His163 of the pharmacophore model are essential for molecular recognition. In addition, the interaction of LASSBio-1945 (9) with Gln189 suggests that perhaps the interaction with Glu166 is not essential if the linker interacts via H-bonding with another close residue. The superimposition of LASSBio-1945 (9) with fragment x0434 (1) illustrates how the n-propyl chain occupies the pocket next to His41, and a possible non-classical hydrogen bond formed by the methylene group of 1,3-benzodioxole, which might be equivalent to the one pointed out for x0434 (1) (Fig. 5). Moreover, LASSBio-1945 (9) is a MPRO inhibitor with a unique structural pattern and a suitable candidate for subsequent optimization steps through medicinal chemistry-oriented SAR cycles.

Fig. 5. Superimposition of the docking pose of LASSBio-1945 (9, green, non-polar hydrogen atoms visible)46 and x0434 (1, magenta). The structure of SARS-CoV-2 MPRO is shown as lines and surface, with pharmacophore model residues and additional predicted interacting residues shown as sticks (carbon atoms in grey). Putative interactions are shown as red dashed lines. Sub-pockets S1–S4 are indicated in orange. This image was generated using UCSF Chimera.22.

Experimental

Fragment-based pharmacophore model

The fragments were analysed using the fragment 3D viewer in the Fragalysis online platform.59

Redocking

The redocking study of the co-crystalized fragments was performed using all GOLD 5.8.1 scoring functions and, in conjunction, the GOLD scoring functions had a better performance than considering each function separately. The docking poses presenting values of root mean square deviation (RMSD) ≤1.6 were considered validated (Table S3, ESI†). The RMSD cut-off is the mean value of the crystal structures' resolution.

Virtual screening

The protein structure was prepared using GOLD 5.8.1, by removing water and cofactors, and for protonation with default settings. For the docking procedure, the MPRO PDB structure 5RF7 (chain A) was used. The binding site was defined in the prepared structure, selecting residues within the 10 Å radius of the sulphur atom of Cys145. Visual inspection of the superimposed crystal structures allowed the identification of amino acid residues whose side chains adopt different conformations to allow the molecular recognition of the co-crystalized fragments (Fig. S7, ESI†). Based on this analysis, the side chains of binding site residues His41, Met49, Asn142, Cys145, Met165, Glu166 and Gln189 were set with free flexibility. The GOLD genetic algorithm (GA) was set to virtual screening mode and 10 GA runs were performed for each ligand. The highest scored docking poses (ChemPLP) were analysed using Hermes, and the distances and angles were measured using UCSF Chimera.22

Molecular similarity and substructure searches

Molecular similarity searches were performed in the KNIME Analytics Plataform60 using the RDKit61 and CDK62 extension packages. Substructure searches were performed in the ChemInventory63 server.

Main protease (MPRO) inhibition assay

The MPRO inhibition activity was measured employing the RapidFire High-Throughput Mass Spectrometry assay.58

Conclusions

In this work, with the aim to identify suitable chemical starting points in the LASSBio Chemical Library to develop inhibitors with adequate antiviral properties, we employed multiple strategies of virtual screening. First, we created a fragment-based pharmacophore model to identify key interactions involved in the molecular recognition at the catalytic site of MPRO. After performing docking-based virtual screening, the combination of pharmacophore-based analysis, substructure and similarity searches, and consensus scoring allowed the selection of eight compounds for the enzymatic assay, which led to the identification of LASSBio-1945 (9) as a MPRO inhibitor (IC50 = 15.97 μM). This hit (9) represents an interesting starting point for subsequent hit-to-lead optimization steps and, to the best of our knowledge, it is a distinct chemical structure pattern for MPRO inhibition, from what have been published in the literature so far. Further SAR studies and analysis will be carried out with this hit (9) in order to increase its potency and arrive at a promising lead candidate. Additionally, we hope to complement the work done by the Diamond Light Source researchers by providing additional insights into chemical subunits useful for the application of medicinal chemistry strategies, and to collaborate with the worldwide efforts to deliver novel therapeutic agents to treat COVID-19.

Abbreviations

- CoV

Coronavirus

- FBDD

Fragment-based drug discovery

- FBPM

Fragment-based pharmacophore model

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- GOLD

Genetic optimization for ligand docking

- HAART

Highly active antiretroviral therapy

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- MPRO

Main protease

- MERS-CoV

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus

- MW

Molecular weight

- SARS-CoV

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus

- WHO

World Health Organization

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Brazilian funding agencies for the financial support involved in this work: Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico – CNPq (INCT-INOFAR Grant #465.249/2014-0; Grant #381138/2019-4); Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro – FAPERJ (Grant #E-26/010.000090/2018). The authors also thank the COVID Moonshot initiative (https://postera.ai/covid) for performing the main protease (MPRO) inhibition activity assay of the compounds of this work.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/d0md00282h

Footnotes

When this study was performed, there were 22 fragments released. By the time the XRD data of the 23rd fragment was made available, we had the analysis completed.

Notes and references

- Paules C. I. Marston H. D. Fauci A. S. JAMA. 2020;323:707. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse J. S. Lalonde T. Xu S. Liu W. R. ChemBioChem. 2020;21:730–738. doi: 10.1002/cbic.202000047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F. Zhao S. Yu B. Chen Y.-M. Wang W. Song Z.-G. Hu Y. Tao Z.-W. Tian J.-H. Pei Y.-Y. Yuan M.-L. Zhang Y.-L. Dai F.-H. Liu Y. Wang Q.-M. Zheng J.-J. Xu L. Holmes E. C. Zhang Y.-Z. Nature. 2020;579:265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P. Yang X.-L. Wang X.-G. Hu B. Zhang L. Zhang W. Si H.-R. Zhu Y. Li B. Huang C.-L. Chen H.-D. Chen J. Luo Y. Guo H. Jiang R.-D. Liu M.-Q. Chen Y. Shen X.-R. Wang X. Zheng X.-S. Zhao K. Chen Q.-J. Deng F. Liu L.-L. Yan B. Zhan F.-X. Wang Y.-Y. Xiao G.-F. Shi Z.-L. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard, https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed 3 July 2020)

- Pillaiyar T. Meenakshisundaram S. Manickam M. Sankaranarayanan M. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020;195:112275. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G. De Clercq E. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2020;19:149–150. doi: 10.1038/d41573-020-00016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee D. L. Sternberg A. Stange U. Laufer S. Naujokat C. Pharmacol. Res. 2020;157:104859. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil C. Ginex T. Maestro I. Nozal V. Barrado-Gil L. Cuesta-Geijo M. Á. Urquiza J. Ramírez D. Alonso C. Campillo N. E. Martinez A. J. Med. Chem. 2020 doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore R. D. Chaisson R. E. AIDS. 1999;13:1933–1942. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199910010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisinger R. W. Dieffenbach C. W. Fauci A. S. JAMA. 2019;321:451. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.21167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgenfeld R. FEBS J. 2014;281:4085–4096. doi: 10.1111/febs.12936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillaiyar T. Manickam M. Namasivayam V. Hayashi Y. Jung S.-H. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:6595–6628. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F. Chen C. Tan W. Yang K. Yang H. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:22677. doi: 10.1038/srep22677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z. Du X. Xu Y. Deng Y. Liu M. Zhao Y. Zhang B. Li X. Zhang L. Peng C. Duan Y. Yu J. Wang L. Yang K. Liu F. Jiang R. Yang X. You T. Liu X. Yang X. Bai F. Liu H. Liu X. Guddat L. W. Xu W. Xiao G. Qin C. Shi Z. Jiang H. Rao Z. Yang H. Nature. 2020;582:289–293. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin S. A. Jha T. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020;201:112559. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LASSBio Chemical Library, http://www.lassbiochemicallibrary.com, (accessed 10 September 2020)

- Douangamath A. Fearon D. Gehrtz P. Krojer T. Lukacik P. Owen C. D. Resnick E. Strain-Damerell C. Aimon A. Ábrányi-Balogh P. Brandão-Neto J. Carbery A. Davison G. Dias A. Downes T. D. Dunnett L. Fairhead M. Firth J. D. Jones S. P. Keely A. Keserü G. M. Klein H. F. Martin M. P. Noble M. E. M. O'Brien P. Powell A. Reddi R. Skyner R. Snee M. Waring M. J. Wild C. London N. von Delft F. Walsh M. A. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:5047. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18709-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortenson P. N. Berdini V. O'Reilly M. Methods Enzymol. 2014;548:69–92. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-397918-6.00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlanson D. A. Fesik S. W. Hubbard R. E. Jahnke W. Jhoti H. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2016;15:605–619. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachman M. Bajusz D. Hetényi A. Scarpino A. Merő B. Egyed A. Buday L. Barril X. Keserű G. M. RSC Med. Chem. 2020;11:552–558. doi: 10.1039/C9MD00519F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen E. F. Goddard T. D. Huang C. C. Couch G. S. Greenblatt D. M. Meng E. C. Ferrin T. E. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chodera J. Lee A. A. London N. von Delft F. Nat. Chem. 2020;12:581. doi: 10.1038/s41557-020-0496-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post Era, COVID Moonshot, https://postera.ai/covid (accessed 03 August 2020)

- Barreiro E. J. Kümmerle A. E. Fraga C. A. M. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:5215–5246. doi: 10.1021/cr200060g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colodette N. M. Franco L. S. Maia R. C. Fokoue H. H. Sant'Anna C. M. R. Barreiro E. J. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 2020;34:1091–1103. doi: 10.1007/s10822-020-00327-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teague S. J. Davis A. M. Leeson P. D. Oprea T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999;38:3743–3748. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19991216)38:24<3743::AID-ANIE3743>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajay A. Walters W. P. Murcko M. A. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:3314–3324. doi: 10.1021/jm970666c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski C. A. Lombardo F. Dominy B. W. Feeney P. J. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 1997;23:3–26. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(96)00423-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veber D. F. Johnson S. R. Cheng H.-Y. Smith B. R. Ward K. W. Kopple K. D. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:2615–2623. doi: 10.1021/jm020017n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark D. E. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery. 2008;3:841–851. doi: 10.1517/17460441.3.8.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.-C. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2015;36:78–95. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitchen D. B. Decornez H. Furr J. R. Bajorath J. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2004;3:935–949. doi: 10.1038/nrd1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripphausen P. Nisius B. Peltason L. Bajorath J. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:8461–8467. doi: 10.1021/jm101020z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedreira J. G. B. Franco L. S. Barreiro E. J. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2019;19:1679–1693. doi: 10.2174/1568026619666190620144142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajorath J. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2002;1:882–894. doi: 10.1038/nrd941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggiora G. Vogt M. Stumpfe D. Bajorath J. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:3186–3204. doi: 10.1021/jm401411z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bases de Estruturas Cristalinas – CAPES, https://bdec.dotlib.com.br/, (accessed 30 June 2020)

- Jones G. Willett P. Glen R. C. Leach A. R. Taylor R. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;267:727–748. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge M. D. Murray C. W. Auton T. R. Paolini G. V. Mee R. P. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 1997;11:425–445. doi: 10.1023/A:1007996124545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooij W. T. M. Verdonk M. L. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Bioinf. 2005;61:272–287. doi: 10.1002/prot.20588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korb O. Stützle T. Exner T. E. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2009;49:84–96. doi: 10.1021/ci800298z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R. Wang S. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2001;41:1422–1426. doi: 10.1021/ci010025x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers D. J. Tanimoto T. T. Science. 1960;132:1115–1118. doi: 10.1126/science.132.3434.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- do Amaral D. N. Lategahn J. Fokoue H. H. da Silva E. M. B. Sant'Anna C. M. R. Rauh D. Barreiro E. J. Laufer S. Lima L. M. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36846-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e Sá C. G., PhD Thesis, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Veloso M. P., PhD Thesis, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Lacerda R. B. Sales N. M. da Silva L. L. Tesch R. Miranda A. L. P. Barreiro E. J. Fernandes P. D. Fraga C. A. M. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. Lin D. Sun X. Curth U. Drosten C. Sauerhering L. Becker S. Rox K. Hilgenfeld R. Science. 2020:eabb3405. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai W. Zhang B. Su H. Li J. Zhao Y. Xie X. Jin Z. Liu F. Li C. Li Y. Bai F. Wang H. Cheng X. Cen X. Hu S. Yang X. Wang J. Liu X. Xiao G. Jiang H. Rao Z. Zhang L.-K. Xu Y. Yang H. Liu H. Science. 2020:eabb4489. [Google Scholar]

- Soares T. A., MSc. Dissertation, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Shimamoto Y. Hattori Y. Kobayashi K. Teruya K. Sanjoh A. Nakagawa A. Yamashita E. Akaji K. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015;23:876–890. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann S. Schübel T. Costa F. N. Barbosa M. L. C. Ferreira F. F. Dias T. L. M. F. Araújo M. V. Alexandre-Moreira M. S. Lima L. M. Laufer S. Barreiro E. J. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2018;90:1073–1088. doi: 10.1590/0001-3765201820170796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva T. F. Bispo Júnior W. Alexandre-Moreira M. S. Costa F. N. Monteiro C. Furlan Ferreira F. Barroso R. C. R. Noël F. Sudo R. T. Zapata-Sudo G. Lima L. M. Barreiro E. Molecules. 2015;20:3067–3088. doi: 10.3390/molecules20023067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Lou Z., Rao Z., Sun B., Yang C., Zhou T. and Niu G., CN103159666A, 2011

- Thota S. Rodrigues D. A. Pinheiro P. de S. M. Lima L. M. Fraga C. A. M. Barreiro E. J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2018;28:2797–2806. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2018.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreiro E. J. Fraga C. A. M. Quim. Nova. 1999;22:744–759. doi: 10.1590/S0100-40421999000500019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leveridge M. Collier L. Edge C. Hardwicke P. Leavens B. Ratcliffe S. Rees M. Stasi L. P. Nadin A. Reith A. D. J. Biomol. Screening. 2016;21:145–155. doi: 10.1177/1087057115606707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fragalysis, Fragment 3D viewer, https://fragalysis.diamond.ac.uk/ (accessed 14 April 2020)

- Berthold M. R., Cebron N., Dill F., Gabriel T. R., Kötter T., Meinl T., Ohl P., Sieb C., Thiel K. and Wiswedel B., in Data Analysis, Machine Learning and Applications, ed. C. Preisach, H. Burkhardt, L. Schmidt-Thieme and R. Decker, Springer, Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg, 2008, pp. 319–326 [Google Scholar]

- RDKit: Open-source cheminformatics, http://www.rdkit.org, (accessed 3 August 2020)

- Steinbeck C. Han Y. Kuhn S. Horlacher O. Luttmann E. Willighagen E. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2003;43:493–500. doi: 10.1021/ci025584y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ChemInventory, https://www.cheminventory.net/, (accessed 3 August 2020)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.