Abstract

Objective

Cancer care has been disrupted by the response of health systems to the COVID-19 pandemic, especially during lockdowns. The objective of our study is to evaluate the impact of the pandemic on the incidence of cancer diagnoses in primary care.

Design

Time-series study of malignant neoplasms and diagnostic procedures, using data from the primary care electronic health records from January 2014 to September 2020.

Setting

Primary care, Catalonia, Spain.

Participants

People older than 14 years and assigned in one of the primary care practices of the Catalan Institute of Health with a new diagnosis of malignant neoplasm.

Main outcome measures

We obtained the monthly expected incidence of malignant neoplasms using a temporary regression, where the response variable was the incidence of cancer from 2014 to 2018 and the adjustment variables were the trend and seasonality of the time series. Excess or lack of malignant neoplasms was defined as the number of observed minus expected cases, globally and stratified by sex, age, type of cancer and socioeconomic status.

Results

Between March and September 2020 we observed 8766 (95% CI 4135 to 13 397) fewer malignant neoplasm diagnoses, representing a reduction of 34% (95% CI 19.5% to 44.1%) compared with the expected. This underdiagnosis was greater in individuals aged older than 64 years, men and in some types of cancers (skin, colorectal, prostate). Although the reduction was predominantly focused during the lockdown, expected figures have not yet been reached (40.5% reduction during the lockdown and 24.3% reduction after that).

Conclusions

Reduction in cancer incidence has been observed during and after the lockdown. Urgent policy interventions are necessary to mitigate the indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and related control measures on other diseases and some strategies must be designed in order to reduce the underdiagnosis of cancer.

Keywords: COVID-19, primary care, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We used good-quality data from primary care electronic health records covering about five million people and 75% of the Catalan population.

Our estimation used data from 5 years and we validated our method in a year not affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our analysis extends the first wave of COVID-19-related effects and lasted for 7 months.

We used ecological data and we were not allowed to ensure a causal correlation between reductions in the incidence of cancer and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Background

COVID-19, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, started as an outbreak in Wuhan (China)1 and quickly evolved into a global pandemic.2 The first cases in Europe were identified in France on 24 January 20203 and the first official case in Catalonia (Spain) was reported a month later on 25 February. In a few months, COVID-19 has become one of the greatest public health challenges in recent times. By 5 November 2020, SARS-CoV-2 has infected over 48 million people worldwide and caused more than 1 233 000 deaths.4 In Catalonia, as of the same date, official figures stated there have been 290 244 confirmed COVID-19 cases and 14 482 deaths.5

In the absence of a vaccine, a social distancing strategy has been the primary intervention to reduce the spread of the epidemic and COVID-19-related deaths.6 In many countries, this strategy includes a national lockdown.6 In Spain, lockdown was adopted on 14 March.7 During and after the lockdown, governments advocated that patients communicated with their general practitioners by phone, encouraged people to stay at home and work from home, cancelled non-essential healthcare services, restricted some diagnostic and therapeutic procedures to urgent cases only, and scaled down most routine preventive activities.8 Despite the need for these measures to control the epidemic and reduce COVID-19 mortality,9 many studies point out collateral health damages. In fact, a reduction in preventive care measures, such as screening10 or childhood vaccination,11 diagnosis,12 and control of chronic diseases in primary care,13 was reported. In addition, some studies highlighted an increase in mental illness14 as well as all-cause mortality.15

Cancer care has also been disrupted by the response of health systems to the pandemic.16 Some studies have highlighted the problem of access to and utilisation of cancer services during and after the first wave of SARS-CoV-2.17–19 Some examples are limitations of access to screening programmes, to medical care cancer-related visits (both in primary care and in hospitals), to cancer diagnostic tests, reduction in scheduled cancer surgeries due to limited access to postsurgical critical care units and occupation of hospital beds by patients with COVID-19, reduction of treatments that could pose a high risk to the patient in the circumstances of the pandemic, and modifications of therapeutic guidelines, among others.18–21 In some countries, a reduction in cancer diagnostics and cancer encounters was observed.22–24 This led to a reduction in new cancer diagnoses and a delay in cancer treatment.25 26 There is evidence that progression of cancers during these delays (even short delays of 3 months for more aggressive cancers) will impact on patients’ long-term survival.24 27 In the UK, substantial increases in the number of avoidable cancer deaths are to be expected as a result of delays in diagnosis due to the COVID-19 pandemic.28 As some projections have estimated that COVID-19-related disruption in healthcare may last for more than 18 months,24 it is crucial to promptly quantify the effects on cancer diagnosis in any health system in order to mitigate their negative effects.

Considering that the future of the COVID-19 pandemic is currently unknown, we need to ensure that patients continue to receive proper cancer care in order to minimise the clinical impact of a diagnostic delay due to COVID-19-related dysfunctions. The aim of this study is to analyse and interpret the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the incidence of malignant neoplasms through the analysis of primary care electronic health records (EHR) data in Catalonia.

Methods

Design and data source

We performed a time-series study of malignant neoplasms case reported diagnoses. Data were extracted from primary care EHR of the Institut Català de la Salut (Catalan Institute of Health; or ICS, its Catalan initials). ICS is the main primary care provider in Catalonia. It manages around 75% of all primary care practices (PCPs) in the Catalan public health system and covers about 5.8 million people. Its population is highly representative of the population of Catalonia in terms of geographical area, age distribution and gender.29 In 2005, ICS implemented a universal EHR system for use in primary care, known as ECAP (Estació Clínica d’Atenció Primària), which is a software system that serves as a repository for structured data on diagnoses (coded according to the International Classification of Diseases 10th revision, ICD-10), clinical variables, prescription data, laboratory test results and diagnostic requests. Data from ICS’ primary care EHR, including cancer diagnoses, have been previously validated in several studies.30

Participants and study period

We included all patients older than 14 years old with a malignant neoplasm diagnosis registered in the EHR (see ICD-10 codes in online supplemental material 1). The study period included all months between January 2014 and September 2020. We divided this period into three for the time-series analysis: training (2014–2018), validation (2019) and analysis (2020). In addition, we separated the year 2020 available months into two periods for calculation of reductions in cancer incidence: ‘lockdown period’ from March to June, coinciding with the state of alarm in Spain (including the lockdown and different phases of de-escalation), and ‘postlockdown period’ from July to September, after the state of alarm.

bmjopen-2020-047567supp001.pdf (458.2KB, pdf)

Variables

The main variable was diagnosis of malignant neoplasms. Monthly incidence rates of malignant neoplasm per 105 population were calculated.

Time-series analyses were performed globally, by sex, age groups (15–64 years old and >64 years old), type of neoplasm, socioeconomic status and rurality. We assessed the socioeconomic status using the validated deprivation index based on census data (MEDEA deprivation index) constructed by the project Mortality and socio-economic and environmental inequalities in small areas of cities in Spain (MEDEA project).31 We categorised the MEDEA Deprivation Index into quartiles, where first and fourth quartiles are the least and the most deprived areas, respectively. Rural areas were categorised separately and were defined as areas with less than 10 000 inhabitants and a population density lower than 150 inhabitants/km2.

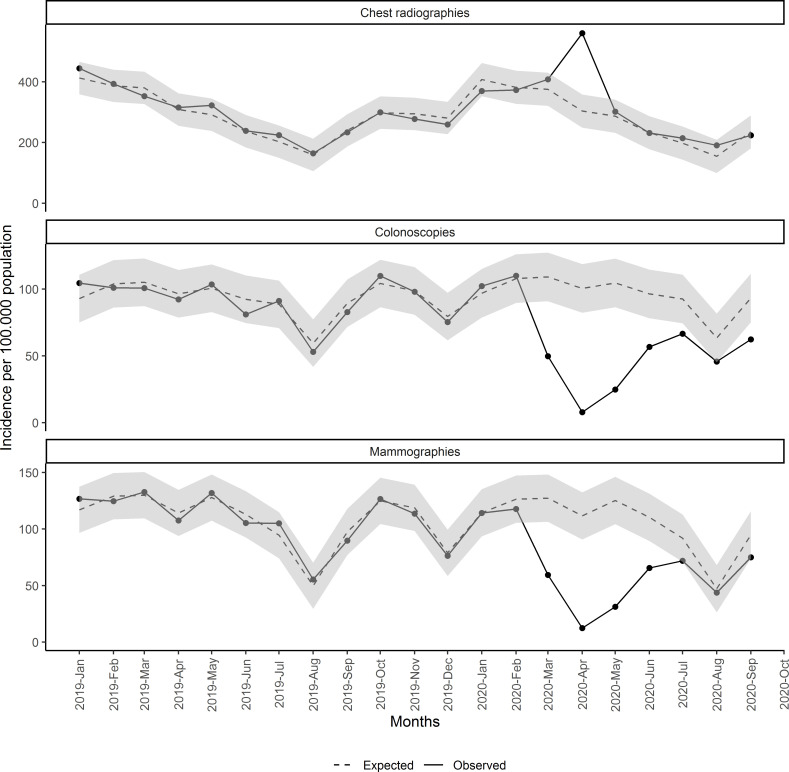

We also performed the same time-series analysis for some related cancer diagnostic procedures with data available, such as mammograms, colonoscopies and chest radiographies.

Statistical analysis

We calculated monthly malignant neoplasm and diagnostic procedures incidence rates per 105 population as the number of new diagnoses or procedures divided by the number of alive population assigned to ICS PCPs and multiplied by 100 000 (source of the population: ECAP).

We obtained the expected incidence for the study period using a time-series regression, where the response variable was the incidence rate per 105 inhabitants from 2014 to 2018, and the adjustment variables were the trend and seasonality of the time series. Data set was divided into three sets: training set (from 2014 to 2018), validation set (2019) and analysis set (2020). We used the training set to adjust the model and validation set to test our method as a sensitivity analysis. We checked whether our method identified any excess or reduction in the monthly incidence rates in a regular year not affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, we projected the estimated time series to our analysis set.

The number of expected cancer diagnoses for each period was obtained multiplying the projected incidence by the population and dividing by 100 000. Excess or lack of malignant neoplasms and diagnostic procedures were defined as the number of observed minus expected diagnoses, estimated monthly and only for the periods where observed incidence was under the lower 95% CIs of the time series. We also calculated the percentage of reduction as follows: (number of observed diagnoses−number of expected diagnoses)/number of expected diagnoses. This percentage was also calculated for the lockdown period and the postlockdown period. We calculated 95% CI for each estimate.

All analyses have been conducted using R V.3.5.1.32 Details and validation of our model can be found in online supplemental material 2.

bmjopen-2020-047567supp002.pdf (169.9KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement statement

This research was done without patient involvement. Patients were not invited to comment on the study design and were not consulted to develop patient relevant outcomes or interpret the results. Patients were not invited to contribute to the writing or editing of this document for readability or accuracy.

Results

The population structure assigned to Catalan PCP and used to calculate cancer incidence rates has remained stable in the study period in terms of age and gender, as shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study population by set: training set (2014–2018), validation set (2019) and analysis set (2020)

| Variable | 2014–2018 | 2019 | 2020* |

| Population older than 14 years | 4 781 835 | 4 846 503 | 4 927 406 |

| % of women | 51.21 | 51.20 | 51.15 |

| % of population older than 64 years | 22.29 | 22.36 | 22.39 |

| Socioeconomic status: % of people in the first quartile (least deprived) | 21.69 | 21.71 | 21.70 |

| Socioeconomic status: % of people in the second quartile | 15.23 | 15.23 | 15.25 |

| Socioeconomic status: % of people in the third quartile | 20.92 | 20.91 | 20.72 |

| Socioeconomic status: % of people in the fourth quartile (most deprived) | 18.24 | 18.24 | 18.47 |

| % of people in rural areas | 23.93 | 23.91 | 23.86 |

*Until September.

From January 2014 to September 2020, 273 379 new malignant neoplasms were registered in primary care. This represents a monthly average incidence per 105 population of 72.4 during the 2014–2018 period, 72.8 during 2019 and only 54.6 during 2020. From January to September 2020, 24 265 new cancers were recorded, of which 47.3% were women and 63.5% older than 64 years, with similar distribution to previous years. Regarding the type of cancer, non-melanoma skin cancers accounted for 24.8% of all new cancers diagnosed in 2020. Online supplemental material 3 provides the number and monthly incidence average for each type of cancer and other variables for the three periods considered in our study.

bmjopen-2020-047567supp003.pdf (47.3KB, pdf)

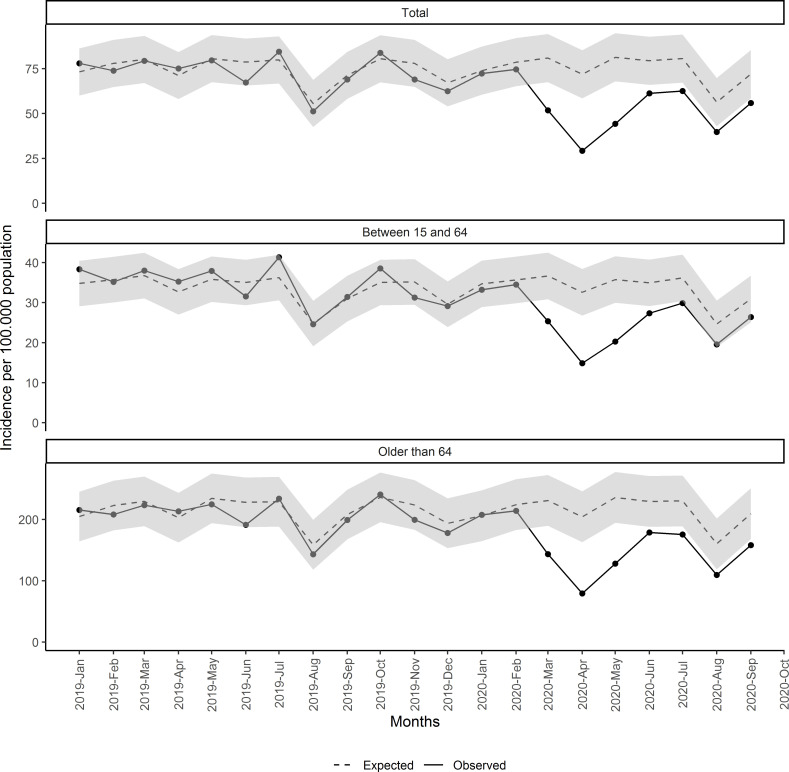

Figure 1 shows the observed and estimated rates of monthly new malignant neoplasm diagnoses (with 95% CI) since January 2019. Observed incidences were as expected for 2019 and the first 2 months of 2020. Since March 2020, observed incidences of malignant neoplasms were significantly lesser than expected, for the whole population and by age groups.

Figure 1.

Monthly incidence of malignant neoplasm since January 2019, total and by age group.

We estimated that the difference between the expected and observed diagnoses accounted for 8766 fewer cancers (95% CI 4135 to 13 397) from March to September. This represents a reduction of 34% in the diagnosis of malignant neoplasm compared with the expected. This reduction was greater during the lockdown period, with 40.5% (95% CI 28.2% to 49.2%) reduction compared with expected, vs 24.3% (95% CI 6.2% to 36.5%) for the postlockdown period (table 2). The months with greater reduction were April, May and March, with reductions of 59.3% (95% CI 50% to 65.7%), 45.5% (95% CI 34.8% to 53.2%) and 36% (95% CI 23.2% to 45.1%), respectively. Detailed expected cases and the number and percentages of cancer reductions by month are shown in online supplemental material 4, stratified by age group, sex, socioeconomic status and type of cancer.

Table 2.

Estimated number of underdiagnosed malignant neoplasms and diagnostic tests and percentage (%) of reduction compared with expected, overall and by lockdown and postlockdown periods

| Total | Total (March–September) | Lockdown period (March–June) | Postlockdown period (July–September) | |||

| n (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | n (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | n (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |

| 8766 (4135 to 13 397) | 34.0 (19.5 to 44.1) | 6262 (3616 to 8909) | 40.5 (28.2 to 49.2) | 2504 (519 to 4488) | 24.3 (6.2 to 36.5) | |

| Between 15 and 64 | 2238 (1125 to 3352) | 25.2 (15.4 to 32.1) | 1997 (1106 to 2888) | 37.2 (24.7 to 46.2) | 241 (19 to 463) | 6.9 (0.7 to 11.1) |

| Older than 64 | 5829 (2627 to 9031) | 35.2 (19.6 to 45.7) | 4094 (2266 to 5921) | 41.2 (27.9 to 50.3) | 1736 (361 to 3110) | 26.1 (6.9 to 38.8) |

| Women | 3686 (1618 to 5754) | 31.6 (16.8 to 41.8) | 2757 (1576 to 3939) | 39.2 (26.9 to 47.9) | 928 (42 to 1814) | 20 (1.1 to 32.8) |

| Men | 5089 (2362 to 7816) | 36.1 (20.8 to 46.4) | 3509 (1951 to 5068) | 41.6 (28.3 to 50.7) | 1580 (411 to 2748) | 27.9 (9.1 to 40.2) |

| Skin (non-melanoma) | 3118 (1807 to 4429) | 43.7 (31 to 52.4) | 2346 (1596 to 3095) | 55.1 (45.5 to 61.8) | 773 (211 to 1334) | 26.9 (9.1 to 38.8) |

| Melanoma | 243 (83 to 403) | 35.7 (18.2 to 44.6) | 202 (74 to 330) | 50.9 (27.5 to 62.9) | 41 (9 to 73) | 14.5 (4.8 to 19.3) |

| Colorectal | 568 (167 to 970) | 27.3 (11.0 to 36.7) | 478 (157 to 799) | 38.3 (16.9 to 50.9) | 91 (10 to 171) | 10.9 (1.7 to 15.9) |

| Prostate | 539 (189 to 890) | 33.3 (16.7 to 42.2) | 454 (174 to 735) | 45.2 (24.0 to 57.2) | 85 (15 to 155) | 13.8 (3.7 to 18.8) |

| Breast | 336 (173 to 500) | 17.1 (10.9 to 21.3) | 336 (173 to 500) | 27.8 (17.5 to 35.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Lung | 350 (49 to 650) | 20.0 (4 to 28.5) | 262 (37 to 487) | 25.4 (5.1 to 36.5) | 88 (13 to 163) | 12.2 (2.6 to 17.2) |

| Others | 2585 (873 to 4297) | 24.5 (10.7 to 33.2) | 1829 (801 to 2857) | 28.9 (16.2 to 37.1) | 755 (71 to 1439) | 17.9 (2.2 to 27.4) |

| First quartile: urban least deprived | 2092 (1010 to 3173) | 35.5 (21.8 to 44.3) | 1636 (914 to 2358) | 45.5 (31.8 to 54.6) | 456 (96 to 816) | 19.8 (5.5 to 28.7) |

| Second quartile | 963 (500 to 1427) | 25 (16.4 to 30.6) | 818 (470 to 1165) | 35.4 (25.4 to 42.0) | 146 (30 to 261) | 9.5 (2.5 to 13.8) |

| Third quartile | 1557 (758 to 2356) | 30.2 (18.8 to 37.5) | 1354 (714 to 1994) | 43.5 (28.9 to 53.2) | 203 (43 to 362) | 9.9 (2.7 to 14.3) |

| Fourth quartile: urban more deprived | 1649 (760 to 2539) | 35.7 (20.4 to 46.1) | 1105 (596 to 1613) | 39.9 (26.4 to 49.2) | 545 (164 to 925) | 29.4 (11.1 to 41.4) |

| Rural areas | 1325 (686 to 1965) | 21.3 (13.4 to 26.7) | 1099 (620 to 1579) | 29.9 (20.4 to 36.6) | 226 (66 to 386) | 8.8 (3.2 to 12.7) |

| Colonoscopy | 16 219 (10 836 to 21 603) | 49.8 (41.2 to 55.6) | 13 401 (9812 to 16 990) | 66.1 (58.8 to 71.2) | 2818 (1024 to 4613) | 22.9 (10.6 to 30.7) |

| Mammography | 15 099 (10 974 to 19 223) | 43.2 (39.5 to 45.6) | 15 099 (10 974 to 19 223) | 64.5 (56.9 to 69.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Chest radiography* | 12 638 (9947 to 15 329) | 14.3 (9.3 to 22.1) | 12 638 (9947 to 15 329) | 21.4 (14.2 to 31.7) | 0 | 0 |

*In the case of chest radiography the results are the excess of radiographies and the percentage of increase instead of the underdiagnosis.

bmjopen-2020-047567supp004.pdf (21.2MB, pdf)

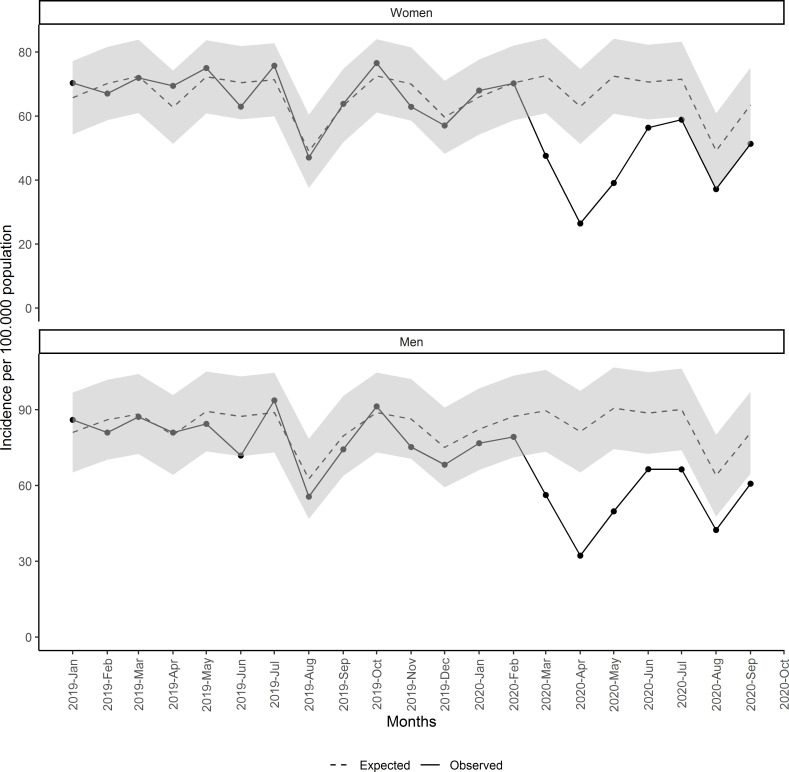

The estimated number of underdiagnosed malignant neoplasms and the percentage of underdiagnoses compared with the expected are presented stratified by age, sex, type of neoplasm, socioeconomic status and rurality in table 2. Population older than 64 years had greater reduction than the population between 15 and 64 years: 35.2% (95% CI 19.6% to 45.7%) vs 25.2% (95% CI 15.4% to 32.1%). Regarding sex, reduction in men was greater than in women: 36.1% (95% CI 20.8% to 46.4%) and 31.6% (95% CI 16.8% to 41.8%), respectively (figure 2 and table 2).

Figure 2.

Monthly incidence of malignant neoplasm since January 2019 by sex.

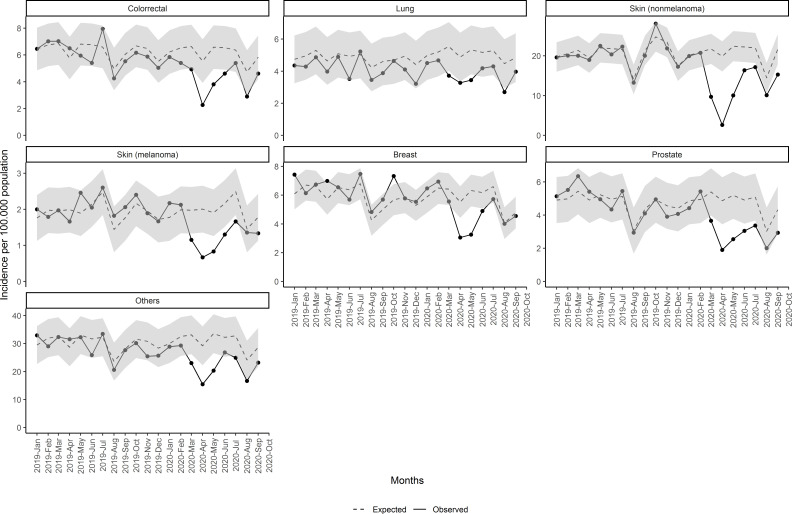

Regarding the type of cancer, we found that in all cancers observed incidences were lesser than expected since March 2020 (figure 3 and table 2). This reduction was greater in April and since then the incidence started to increase, although still under the 95% CI until August, with big differences between the types of cancer. Non-melanoma skin cancers were those with higher reductions with 3118 fewer cancers (95% CI 1807 to 4429), followed by colorectal cancer with 568 fewer cancers (95% CI 167 to 970), representing a reduction of 27.3% (95% CI 11% to 36.7%), and prostatic cancers with 539 fewer cancers (95% CI 189 to 890) and 33.3% reduction (95% CI 16.7% to 42.2%), compared with the expected. Breast and lung new cancers were moderately reduced compared with other types of cancers: 17.1% (95% CI 10.9% to 21.3%%) and 20% (95% CI 4% to 28.5%), respectively. Incidences in lung cancer were under the 95% CI for fewer months than the other types of cancer, as shown in figure 3. In addition, all reductions in breast cancer were during the lockdown period.

Figure 3.

Monthly incidence of malignant neoplasm since January 2019 by type of cancer.

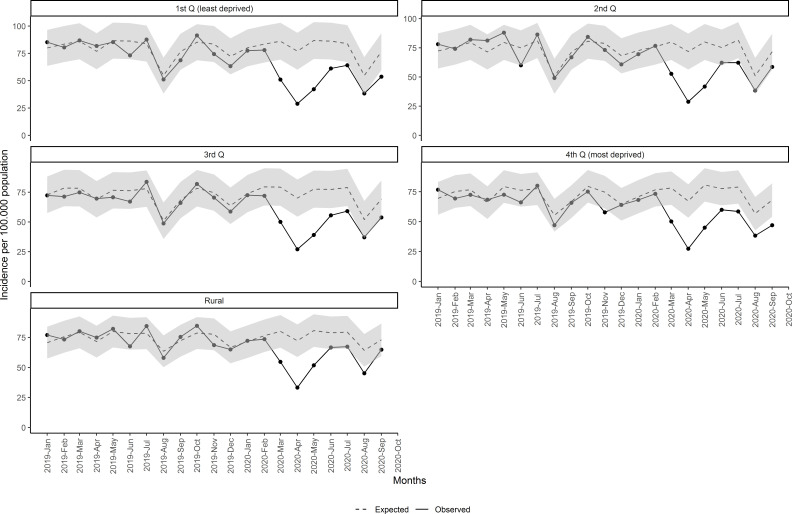

The same pattern and reduction of new malignant diagnosis were observed in all socioeconomic status (figure 4 and table 2), although in rural areas it was the least, with 21.3% (95% CI 13.4% to 26.7%) reduction and only 3 months of statistical differences between observed and expected. Urban least and most deprived areas accounted for similar reduction, although with some differences between periods. The least deprived areas had greater reduction during the lockdown period (45.5% vs 39.9% in the most deprived). Nonetheless, the least deprived areas accounted for less reduction after the lockdown.

Figure 4.

Monthly incidence of malignant neoplasm since January 2019 by socioeconomic status and rurality. Q, quartile.

Finally, figure 5 shows the observed and estimated rates per 105 population of monthly new mammograms, colonoscopies and chest radiographies. We observed a reduction in mammograms and colonoscopies during the same months as we observed for neoplasms and an excess of chest radiographies during April 2020. The reduction in procedures accounted for 16 219 fewer colonoscopies (95% CI 10 836 to 21 603) and for 15 099 fewer mammograms (95% CI 10 974 to 19 223) (table 2). In addition, reduction in mammograms was only observed during the lockdown period.

Figure 5.

Monthly incidence of mammograms, colonoscopies and chest radiographies since January 2019.

Discussion

Our study analyses the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and related control measures on cancer diagnosis. We found a reduction of more than 8700 new cancers since March 2020, representing 34% fewer cancers than expected. This reduction was greater during the months of March, April and May, temporarily overlapping with the lockdown measures established in Spain in mid-March 2020.7 However, the reduction in new diagnoses of cancer extended beyond the end of the lockdown, especially for people older than 64 years, men, most deprived areas and some types of cancer. Our work also shows similar reductions in some cancer diagnostic procedures during the same period. Although this negative effect on the incidence of cancers appeared to occur across all ages, sex and socioeconomic status, the most deprived areas had greater reduction after the lockdown (29.4% vs 19.8%) and recovered worse than the least deprived. These deprived areas should be areas of special attention and priority areas of governments’ actions and control measures to reduce pre-existing inequalities that COVID-19 has exacerbated and highlighted.33–35

Other studies found similar results in many countries.12 22 25 33 36 For example, reductions in cancer diagnoses in Italy37 accounted for 39% and for 29% in Slovenia.25 In addition, a reduction of 48%, 75% and 42% was observed for X-rays, mammograms and ultrasounds in Slovenia,25 and colonoscopy has been reduced by 80% in Argentina.36 Some of these reductions are related to a suspension or decline in cancer screening services.22 26 38 39 However, some studies pointed out that the reductions in diagnostic procedures are also related to a decrease in cancer encounters, leading to a reduction in diagnostic suspicion22 and therefore a treatment delay.40

Our study reveals that almost all cancers have been affected. Nonetheless, the reduction in new cancer diagnoses ranged between 43.7% in non-melanoma skin cancers and 17.1% in breast cancers. These differences between cancers are consistent with the impact on cancer diagnosis described in several studies, although these works are mainly focused on the first wave of the COVID-19 period. In Italy, colorectal cancer has decreased by 62% and prostate cancer by 75%, having the greatest reductions, while breast cancer was moderately reduced (26%).37 In the UK, patients with new melanoma dropped by 67.1%, while lung cancer was the least altered (46.8% reduction).22 Dutch researchers also found differences in cancer reductions between non-skin cancers (26%) and skin cancers (60%).26

Several reasons may explain our results. First, during the lockdown, all non-essential health activities were interrupted and authorities advised the population to stay at home. In addition, Spain was heavily hit by COVID-19 in March to May, the health system collapsed, and many diagnostic procedures were halted, except those used to diagnose some complications of COVID-19, such as chest radiography or thoracic CT scans. However, even after the lockdown restrictions, cancer incidence did not achieve the expected results, suggesting that measures to control the pandemic still have side effects on the diagnosis of cancer as well as other diseases. Second, face-to-face visits have dropped drastically since March and have been replaced by telehealth,41 making it more difficult to appraise signs and symptoms and to initiate an investigation for a cancer diagnosis, especially for some populations such as the more socioeconomic disadvantaged individuals who are less likely to engage in telemedicine.42 43 Lastly, studies also suggested some reasons linked to health-seeking behaviour of patients or the fear of being infected by SARS-CoV-2.19 26 44 45

The 34% decrease in the incidence of new cancers in our study is considered to be concerning, although the effects of these reductions are still uncertain as the impact of the pandemic on patients with cancer can only be reliably assessed after a reasonable time. Some studies estimated an increase in the total years of life lost, excess mortality and other consequences,17 24 38 46–50 although these may differ according to tumour type,18 50–52 as some cancers such as lung, pancreatic or breast progress rapidly and require immediate diagnosis and treatment to prevent adverse outcomes.

Our study has some limitations. First, we performed a time-series study with ecological data. This approach does not allow to ensure a causal correlation between reduction in the incidence of malignant neoplasm and the COVID-19 pandemic, although the reduction in the observed data around the start of the state of alarm in March 2020 is clear. Second, as our analysis is based on crude rates, major changes in population structure could limit the use of the proposed method, but since population age and gender distribution has remained relatively stable in the study period we have maintained crude rate analysis for a straightforward reporting of the volume of cancer reductions. Finally, given that COVID-19 hit Spain hard with an excess of 44 000 deaths,53 some can argue that part of the reduction of the incidence of malignant neoplasms could be linked to the harvesting effect, where some patients who could have been diagnosed had deceased. Even so, we observed a reduction in cancers in all age groups, while the excess of deaths caused by COVID-19 was mostly in the elderly.53

Despite the limitations, this study also has strengths. Several studies have used the Catalan primary care EHR data to perform useful research in real-world conditions.31 54 Moreover, our estimation used data from 5 years and we validated our method with 2019 diagnoses, where we did not find any excess or reduction in the incidence of cancer, strengthening our findings in 2020. In addition, our analysis extends the first wave of COVID-19-related effects and lasted for 7 months in contrast to other studies focused on lockdown period only. We also assessed the socioeconomic differences, identifying the most affected areas that should be a priority during the following months. As ICS manages about three in every four practices in Catalonia, our results are generalisable and our method could be introduced to other settings that also use EHR. That way, our findings could be confirmed in other countries.

In conclusion, our study shows a reduction in registered cancer incidence during the COVID-19 pandemic, suggesting delays in cancer diagnosis, which may lead to negative health outcomes. We must continue to control the pandemic, but we also need to ensure that common causes of morbidity and mortality are also taken into account when decisions are made. Urgent policy interventions are necessary to mitigate possible effects on other diseases. In addition, long-term studies should be performed in order to evaluate the future effects of this situation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the efforts of all members of the SISAP team during the last months. We would also like to thank all the primary care healthcare professionals in Catalonia during these challenging times. We also thank Ada Ferrer for her valuable contribution to language editing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Twitter: @ErmengolComa, @mmarzoc

Contributors: EC, CG, NM, MM-C, MB, LM-B, MF, FF, AM and MM contributed to the design of the study, interpretation of the results and reviewed the manuscript. EC, FF and NM had access to the data, performed the statistical analysis and acted as guarantors. EC, CG, MM-C, MB and NM wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet the authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. All data and analytical code are provided at https://github.com/ErmengolComa/neos.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study was done in accordance with existing statutory and ethical approvals from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the IDIAPJGol (project code: 20/172-PCV).

References

- 1.Phelan AL, Katz R, Gostin LO. The novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020;323:709. 10.1001/jama.2020.1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . Novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: increased transmission in the EU/EEA and the UK. Stockholm: ECDC, 2020. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/RRA-sixth-update-Outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-disease-2019-COVID-19.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernard Stoecklin S, Rolland P, Silue Y, et al. First cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in France: surveillance, investigations and control measures, January 2020. Euro Surveill 2020;25:2000094. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.6.2000094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johns Hopkins University coronavirus COVID‐19 global cases by the center for systems science and engineering (CSSE). Available: https://www.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6 [Accessed 5 Nov 2020].

- 5.Departament de Salut . Generalitat de Catalunya. Available: https://dadescovid.cat/ [Accessed 5 Nov 2020].

- 6.Ferguson NM, Laydon D, Nedjati-Gilani G. Report 9: impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand. Imperial College London, 2020. http://www.imperial.ac.uk/mrc-global-infectious-disease-analysis/covid-19/report-9-impact-of-npis-on-covid-19/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boletín oficial del estado (BOE) . Real Decreto 463/2020, de 14 marzo, POR El que se declara El estado de alarma para La gestión de la situación de crisis sanitaria ocasionada POR El COVID-19. Available: https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2020-3692 [Accessed 15 October 2020].

- 8.Harky A, Chiu CM, Yau THL, et al. Cancer patient care during COVID-19. Cancer Cell 2020;37:749–50. 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siqueira CADS, Freitas YNLde, Cancela MdeC, et al. The effect of lockdown on the outcomes of COVID-19 in Spain: an ecological study. PLoS One 2020;15:e0236779. 10.1371/journal.pone.0236779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vigliar E, Iaccarino A, Bruzzese D. Cytology in the time of coronavirus disease (covid-19): an Italian perspective. J Clin Pathol 2020:jclinpath-2020-206614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santoli JM, Lindley MC, DeSilva MB, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Routine Pediatric Vaccine Ordering and Administration - United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:591–3. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6919e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams R, Jenkins DA, Ashcroft DM, et al. Diagnosis of physical and mental health conditions in primary care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2020;5:e543–50. 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30201-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coma E, Mora N, Méndez L, et al. Primary care in the time of COVID-19: monitoring the effect of the pandemic and the lockdown measures on 34 quality of care indicators calculated for 288 primary care practices covering about 6 million people in Catalonia. BMC Fam Pract 2020;21:208. 10.1186/s12875-020-01278-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White RG, Van Der Boor C. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and initial period of lockdown on the mental health and well-being of adults in the UK. BJPsych Open 2020;6:e90. 10.1192/bjo.2020.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banerjee A, Pasea L, Harris S, et al. Estimating excess 1-year mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic according to underlying conditions and age: a population-based cohort study. Lancet 2020;395:1715–25. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30854-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang H, Zhang L. Risk of COVID-19 for patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:e181. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30149-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amit M, Tam S, Bader T, et al. Pausing cancer screening during the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2pandemic: should we revisit the recommendations? Eur J Cancer 2020;134:86–9. 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vanni G, Pellicciaro M, Materazzo M, et al. Breast cancer diagnosis in Coronavirus-Era: alert from Italy. Front Oncol 2020;10:938. 10.3389/fonc.2020.00938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vrdoljak E, Sullivan R, Lawler M. Cancer and coronavirus disease 2019; how do we manage cancer optimally through a public health crisis? Eur J Cancer 2020;132:98–9. 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suárez J, Mata E, Guerra A, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic during Spain’s state of emergency on the diagnosis of colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol 2021;123:32–6. 10.1002/jso.26263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stroman L, Cathcart P, Lamb A, et al. A cross-section of UK prostate cancer diagnostics during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) era - a shifting paradigm? BJU Int 2021;127:30–4. 10.1111/bju.15259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.London JW, Fazio-Eynullayeva E, Palchuk MB, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer-related patient encounters. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 2020;4:657–65. 10.1200/CCI.20.00068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rutter MD, Brookes M, Lee TJ, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on UK endoscopic activity and cancer detection: a national endoscopy database analysis. Gut 2021;70:gutjnl-2020-322179. 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sud A, Jones ME, Broggio J, et al. Collateral damage: the impact on outcomes from cancer surgery of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Oncol 2020;31:1065–74. 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zadnik V, Mihor A, Tomsic S, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on cancer diagnosis and management in Slovenia - preliminary results. Radiol Oncol 2020;54:329–34. 10.2478/raon-2020-0048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dinmohamed AG, Visser O, Verhoeven RHA, et al. Fewer cancer diagnoses during the COVID-19 epidemic in the Netherlands. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:750–1. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30265-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sud A, Torr B, Jones ME, et al. Effect of delays in the 2-week-wait cancer referral pathway during the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer survival in the UK: a modelling study. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:1035–44. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30392-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maringe C, Spicer J, Morris M, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer deaths due to delays in diagnosis in England, UK: a national, population-based, modelling study. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:1023–34. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30388-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bolíbar B, Fina Avilés F, Morros R. Base de datos SIDIAP: La historia clínica informatizada de Atención Primaria como Fuente de información para La investigación epidemiológica. Med Clin 2012;138:617–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Recalde M, Manzano-Salgado CB, Díaz Y, et al. Validation of cancer diagnoses in electronic health records: results from the information system for research in primary care (SIDIAP) in northeast Spain. Clin Epidemiol 2019;11:1015–24. 10.2147/CLEP.S225568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garcia-Gil M, Elorza J-M, Banque M, et al. Linking of primary care records to census data to study the association between socioeconomic status and cancer incidence in southern Europe: a nation-wide ecological study. PLoS One 2014;9:e109706. 10.1371/journal.pone.0109706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.R Core Team . R software: version 3.5.1. R found STAT Comput : 2018.

- 33.Baena-Díez JM, Barroso M, Cordeiro-Coelho SI, et al. Impact of COVID-19 outbreak by income: hitting hardest the most deprived. J Public Health 2020;42:698–703. 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buron A, Auge JM, Sala M, et al. Association between socioeconomic deprivation and colorectal cancer screening outcomes: low uptake rates among the most and least deprived people. PLoS One 2017;12:e0179864. 10.1371/journal.pone.0179864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dunlop S, Coyte PC, McIsaac W. Socio-economic status and the utilisation of physicians' services: results from the Canadian national population health survey. Soc Sci Med 2000;51:123–33. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00424-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bozovich GE, Alves De Lima A, Fosco M. Daño colateral de la pandemia por COVID-19 en centros privados de salud de Argentina [Collateral damage of COVID-19 pandemic in private healthcare centres of Argentina]. Medicina 2020;80:37–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Vincentiis L, Carr RA, Mariani MP. Cancer diagnostic rates during the 2020 ‘lockdown’, due to COVID-19 pandemic, compared with the 2018–2019: an audit study from cellular pathology. J Clin Pathol 2020::jclinpath-2020-206833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Del Vecchio Blanco G, Calabrese E, Biancone L, et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic in the colorectal cancer prevention. Int J Colorectal Dis 2020;35:1951–4. 10.1007/s00384-020-03635-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dinmohamed AG, Cellamare M, Visser O, et al. The impact of the temporary suspension of national cancer screening programmes due to the COVID-19 epidemic on the diagnosis of breast and colorectal cancer in the Netherlands. J Hematol Oncol 2020;13:147. 10.1186/s13045-020-00984-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vanni G, Tazzioli G, Pellicciaro M, et al. Delay in breast cancer treatments during the first COVID-19 Lockdown. A multicentric analysis of 432 patients. Anticancer Res 2020;40:7119–25. 10.21873/anticanres.14741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pérez Sust P, Solans O, Fajardo JC, et al. Turning the crisis into an opportunity: digital health strategies deployed during the COVID-19 outbreak. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2020;6:e19106. 10.2196/19106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asan O, Cooper Ii F, Nagavally S, et al. Preferences for health information technologies among US adults: analysis of the health information national trends survey. J Med Internet Res 2018;20:e277. 10.2196/jmir.9436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michalowsky B, Hoffmann W, Bohlken J, et al. Effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on disease recognition and utilisation of healthcare services in the older population in Germany: a cross-sectional study. Age Ageing 2021;50:afaa260. 10.1093/ageing/afaa260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harper CA, Satchell LP, Fido D, et al. Functional fear predicts public health compliance in the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Ment Health Addict 2020;27:1–14. 10.1007/s11469-020-00281-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vanni G, Materazzo M, Pellicciaro M, et al. Breast cancer and COVID-19: the effect of fear on patients' decision-making process. In Vivo 2020;34:1651–9. 10.21873/invivo.11957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee Y-H, Kung P-T, Wang Y-H, et al. Effect of length of time from diagnosis to treatment on colorectal cancer survival: a population-based study. PLoS One 2019;14:e0210465. 10.1371/journal.pone.0210465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rubinstein SM, Steinharter JA, Warner J, et al. The COVID-19 and cancer Consortium: a collaborative effort to understand the effects of COVID-19 on patients with cancer. Cancer Cell 2020;37:738–41. 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dobson CM, Russell AJ, Rubin GP. Patient delay in cancer diagnosis: what do we really mean and can we be more specific? BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:387. 10.1186/1472-6963-14-387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lai AG, Pasea L, Banerjee A, et al. Estimated impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer services and excess 1-year mortality in people with cancer and multimorbidity: near real-time data on cancer care, cancer deaths and a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e043828. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yousaf-Khan U, van der Aalst C, de Jong PA, et al. Final screening round of the Nelson lung cancer screening trial: the effect of a 2.5-year screening interval. Thorax 2017;72:48–56. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-208655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ginsburg KB, Curtis GL, Timar RE, et al. Delayed radical prostatectomy is not associated with adverse oncologic outcomes: implications for men experiencing surgical delay due to the COVID-19 pandemic. J Urol 2020;204:720–5. 10.1097/JU.0000000000001089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matsuo K, Novatt H, Matsuzaki S, et al. Wait-time for hysterectomy and survival of women with early-stage cervical cancer: a clinical implication during the coronavirus pandemic. Gynecol Oncol 2020;158:37–43. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.05.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Instituto de Salud Carlos III . Vigilancia de Los excesos de mortalidad POR todas LAS causas: MoMo. Available: https://www.isciii.es/QueHacemos/Servicios/VigilanciaSaludPublicaRENAVE/EnfermedadesTransmisibles/MoMo/Documents/informesMoMo2020/MoMo_Situacion%20a%2019%20de%20julio_CNE.pdf [Accessed 15 Oct 2020].

- 54.Ramos R, Balló E, Marrugat J, et al. Validity for use in research on vascular diseases of the SIDIAP (information system for the development of research in primary care): the EMMA study. Rev Esp Cardiol 2012;65:29–37. 10.1016/j.recesp.2011.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-047567supp001.pdf (458.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-047567supp002.pdf (169.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-047567supp003.pdf (47.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-047567supp004.pdf (21.2MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. All data and analytical code are provided at https://github.com/ErmengolComa/neos.