Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic changed the way that schools provide instruction to learners and these changes may last for an extended period of time. One current trend is the use of hyflex instruction, which involves teachers providing instruction to students simultaneously in the classroom and online. This form of instruction provides unique challenges for teachers, including establishing expectations and managing classroom behaviors. Teachers must utilize the same best practices in classroom management in the hyflex environment that they typically use in the face-to-face setting, including (a) teaching expectations, (b) modeling the desired behavior, and (c) providing timely and explicit feedback to support students, especially young children and those with disabilities, to follow the guidelines for physical distancing and to keep students, teachers, administrators, and their families safe at this time. This article provides a brief overview for general and special education teachers to apply these strategies in the hyflex instructional environment to support young children and maintain protocols required due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Classroom management, Hyflex instruction, Online learning

Since March 2020, COVID-19 drastically impacted the ways teachers and school administrators deliver academic and behavioral instruction, along with adjusting the behavioral expectations within online and in-person classroom and school settings. While some schools are addressing the pandemic with fully online remote learning, other schools have chosen to provide some form of face-to-face instruction (i.e., hybrid, hyflex, or in-person). Schools that have made this decision are guided by groups such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2020), which provide recommendations for hybrid and in-person learning environments (e.g., spacing between students, plexiglass separators), and include the caveat that the lowest risk comes with virtual learning, where students and teachers are only connected via an online platform (e.g., Zoom, Microsoft Teams). The CDC (2020) recommendations are not exhaustive, but delineate levels of risk (i.e., low, medium, high); these recommendations include dividing students into intentional cohorts, maintain physical distance, students use their own personal supplies (e.g., computer, pencils, books) without sharing, and classrooms are regularly cleaned and disinfected between students.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought instructional access to light when schools quickly moved to online instruction as they were forced to close their doors in March 2020 across the world to prevent spread of the virus. Because of the swift move to online instruction, many students were left to complete the school year online with little to no live support from the teacher. With this in mind, many school districts across the country used the summer to execute a plan for online learning to support students academically and behaviorally in multiple ways, across multiple platforms which provides families with a menu of options to access their child’s education. While physical distancing may be challenging for all stakeholders in the school setting, it is especially challenging for young children, where touch and sensory interaction are critical parts of social-emotional development (Whiddon & Montgomery, 2011). Nowhere has accessing instruction been more necessary than in the early education realm, where instruction for young children is the foundation for success both academically and behaviorally in school later in their childhood.

Virtual Instructional Modes

Traditional online instruction typically fits into three categories: asynchronous, synchronous, or hybrid. In an asynchronous online course, the instructor creates a course within the learning management system (e.g., Canvas, Blackboard), and organizes activities (i.e., readings, videos, quizzes) into modules with due dates to ensure students access the material and complete assignments. Instructors provide grading and feedback, but there is no formal class or meeting time for students and instructors to interact. In a synchronous online course, the teacher and students have a scheduled meeting time (e.g., every Monday morning at 9 am) on an online platform (e.g., Zoom©, Microsoft Teams©) where the teacher instructs, students interact with one another, and there is time and space for the students to ask questions. Synchronous online courses are similar to traditional face-to-face in-person classes, where the classroom is a virtual platform rather than on a campus. A hybrid course is a combination of asynchronous and in-person, where students meet in person (either online or on campus) on designated, predetermined class dates (e.g., every other Monday at 5 pm), and the remaining instruction takes place online asynchronously.

Modes of PreK-12 instruction in the 2020–2021 school year have included hybrid, hyflex, and fully asynchronous. A variation of the hybrid instructional mode, where students were all in person during some weeks of class and online during other weeks of class, the hyflex instructional design (Beatty, 2014) is not new in the higher education setting. It was developed to provide attendance choice flexibility to students in the graduate setting (Bell et al., 2014; Binneweis & Wang, 2019). Students receiving hyflex instruction have the choice to either attend in-person or synchronously online, with an option for students to watch a recording of the class if they are unable to attend either. Students access the same (or similar) course instruction, materials, content, and activities. Despite the fact that hyflex has been used at the university level, it is still a newer model for use with young children.

Teaching in a Hyflex Environment

Teaching in a hyflex environment is not an easy task; the teacher must provide simultaneous, engaging instruction for both the online and in-person learner, and always has to have a contingency plan for technology glitches. Hyflex provides flexibility for a newer issue, those or potential issues related to quarantining due to COVID-19 exposure, where students don’t miss instruction, and can attend their regular classes from home while quarantined or isolated. Though the convenience of having continuous instruction is one advantage of hyflex teaching, recent news reports (Samee Ali, 2020) indicate that teachers feel overwhelmed by meeting the needs of learners both in-person and online, and are seeking ways to more effectively address this challenge (Samee Ali, 2020).

Teachers must utilize the best practices in classroom management in the hyflex environment that they typically use in the face-to-face setting, including (a) teaching expectations, (b) modeling the desired behavior, and (c) providing timely and explicit feedback to support students, especially young children and those with disabilities, to follow the recommended guidelines for physical distancing (CDC, 2020) while putting forth their best effort to keep students, teachers, administrators, and their families safe at this time. This article provides a brief overview for general and special education teachers to apply these three strategies in the hyflex instructional environment to support children and maintain protocols required due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Classroom Management

Classroom management is a term used to describe the ways a teacher sets and enforces classroom behavioral and academic expectations to create an environment that is conducive to learning and student interaction (Brophy, 2006). Previous research (Gage et al., 2018; Schiefele, 2017) has found that strong classroom management leads to increased engagement and motivation in learning, along with higher academic achievement for students (Stronge et al., 2011). High-quality classroom management in the early childhood years is especially critical for ensuring the academic success of boys who have been identified with or at risk for being identified with emotional or behavioral disabilities (Garwood & Vernon-Feagans, 2017). Classroom management in the early childhood classroom should include explicit teaching of expectations, modeling, and behavior specific feedback.

Setting Remote Students Up for Success

Effectively managing the hyflex classroom requires teachers to proactively set young children up for success by ensuring that remote learners have the appropriate tools for success. First, it is vital that learners have access to reliable high-speed internet, as well as a dedicated device, such as a computer or tablet, that they can use to participate in class activities (Ferri et al., 2020). In addition, young children need the support of parents or other adult caregivers to ensure they are actively engaging in remote learning (Garbe et al., 2020). We suggest that early childhood educators meet with caregivers to ensure that the necessary technology is available in the home and to discuss the caregivers’ roles in supporting learning at home.

In addition, early childhood educators must explicitly plan for ensuring student confidentiality in the hyflex classroom. Under FERPA, non-students and other people in a child’s home can legally attend virtual instruction, but teacher should discourage siblings and others from viewing hyflex instruction and should consider asking families not to record any online learning without permission (U. S. Department of Education, 2020). In addition, there have been occurrences of “zoom bombing” in which a stranger joins an online lesson; in order to reduce the likelihood of this happening, early childhood educators should ensure that their lessons can only be accessed via a password and should set-up a virtual waiting room that requires the teacher to admit each student (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2020).

Teaching Classroom Expectations

Because children do not instinctively know what we expect of them, we must teach them how to meet expectations (Horner & Sugai, 2005) using explicit instruction (Archer & Hughes, 2011). Specifically, teachers should have 3–5 clear and concise classroom expectations (Dunlap et al., 2013). Teachers should choose overarching expectations that are positively stated and describe what they want children to do (Stormont et al., 2008), along with explicit examples and non-examples for each expectation. A sample list of developmentally appropriate expectations that could be used in hyflex instruction mode are: Be kind, Be safe, Be honest. An example of specific behavioral expectations for young children are outlined in Table 1, Classroom Expectations.

Table 1.

Specific behaviors that meet HyFlex classroom expectations for young children

| Classroom expectations | Specific behaviors expected of face-to-face learners | Specific behaviors expected of online learners |

|---|---|---|

| Be kind | Sharing toys | Turning on the camera |

| Taking turns when speaking | Staying muted when the teacher is speaking | |

| Raising hands before speaking | Taking turns when speaking | |

| Arriving at school on time | Raising hand using Zoom tool before speaking | |

| Cleaning up the classroom | Logging in to class session on time | |

| Following teacher directions | Following teacher's directions | |

| Flushing the toilet | ||

| Be safe | Washing hands after using the toilet and before eating | Use the computer for learning only |

| Using a facial tissue for a runny nose | ||

| Walking in a straight line in the hallway | ||

| Be honest | Tell the truth to teachers | Tell the truth to teachers |

| Tell the truth to classmates | Tell the truth to classmates | |

| Tell the truth to parents | Tell the truth to parents |

To help children meet these expectations, a teacher will need to plan and teach structured lessons that offer young children the opportunity to practice these skills with multiple opportunities for immediate feedback from the teacher, just as they would with academic skills. After initial explicit instruction (Archer & Hughes, 2011), teachers should continue to review these expectations at the beginning of every school day. In the hyflex classroom, one simple solution for doing this is to project a PowerPoint slide with visual expectations for all learners to review at the beginning of class every day. For many students, it may be necessary to include this visual throughout the day, and have copies posted at the beginning of every class.

COVID-19 Expectations

Additional recommendations that can be added to the traditional classroom setting expectations help maintain a safe school environment with minimal quarantines, and promote healthy habits for students to stay healthy and continue in-person attendance. One of the main expectations for children and adults alike is physical distancing. The CDC (2020) recommends a distance of at least 6 feet between students, which can be a challenge for young children. However, classroom expectations must include the expectation for physical distancing, which is a new concept to most young children, and is most likely not an expectation in previous classrooms. Teachers most likely had expectations that students would Respect Personal Space as a guideline where students were expected to keep their hands to themselves, not touch other students’ property, and maintain an arm’s length distance when transitioning to different activities through the school day. Children do not instinctively socially distance from one another, and require explicit instruction (Archer & Hughes, 2011) on this new expectation.

Just as they teach academic skills, instructing students to social distance will require teachers to tell students what they are expected to do, show them how to do it, and have children practice the skill repeatedly to mastery. Early childhood teachers can embed instruction and practice regarding COVID-specific classroom practices such as physical distancing into academic learning. Explicit lessons can be embedded in the hyflex classroom to ensure that the students know that when they are in person, they should maintain social distance. This can be done during hyflex instruction by using the in-person students as models, and having the students do online practice at home.

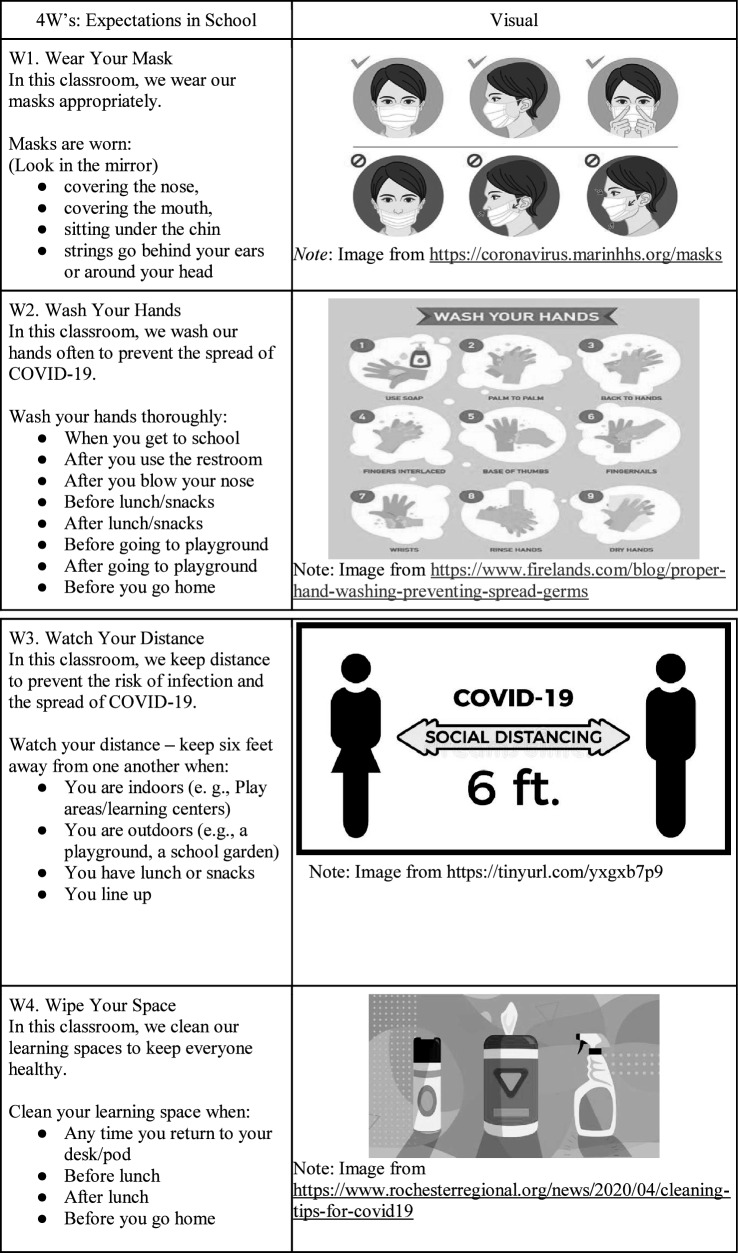

Additional COVID-related expectations include wearing a mask throughout the day appropriately, properly sanitizing personal and community property throughout the school day, and using appropriate hand washing hygiene (CDC, 2020). Wearing masks has become a highly debated topic (Li et al., 2020), but research (Brooks et al., 2020; Hendrix et al., 2020) has repeatedly shown that masks help to reduce the spread of COVID-19, because it is spread through respiratory droplets (CDC, 2020). A mask on one person reduces the spread somewhat, but having all students, teachers, and administrators wear masks reduces the spread of COVID-19 and other airborne illnesses (e.g., the flu) significantly. Expectations for mask-wearing throughout the day, appropriate times and procedures for hand-washing, and cleaning should be accompanied by visuals depicting examples and non-examples. These COVID-specific expectations can be modeled and practiced in the hyflex environment, by ensuring students at home are wearing masks for short periods of time, while the students in person wear masks. Additionally, during transitions, all students can practice cleaning their learning space and washing their hands.

The Four W’s Classroom Visual provides an example of expectations for COVID-related changes in the typical classroom (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

4 W’s: Classroom expectations during COVID-19

Continuous Modeling

In addition to instructing and practicing application of the COVID-related classroom expectations for young children, teachers must consistently model these behaviors on a daily basis. Modeling is an effective instructional practice where a teacher or peer (i.e., the model) demonstrates the behavior they want other students to imitate (Archer & Hughes, 2011). Like children, preschool and early elementary teachers are not accustomed to socially distancing from their students. When adults work with young children, non-verbal communication is a natural occurrence and aids children in gaining language skills (Mundy et al., 1995); teachers may tap a child on their shoulder as a sign of reassurance or to physically address a child’s current need (Lynch & Garrett, 2010), or may give students a high-five for encouragement. To support children in learning to social distance, teachers must model the behavior by also socially distancing. To maintain appropriate social distance from the students in the classroom, teachers must make adjustments to their typical teaching practices. To facilitate physical distancing with young children, teachers should use visuals that provide students with feedback for appropriate behavior, that help support physical distancing. Visuals can be displayed or referred to during hyflex instruction so all students are provided a reminder. The Physically Distanced Teaching Practices chart provides examples of common teaching practices with alternative practices that teachers can use to achieve the same outcome (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Physically distanced teaching practices

| Common teaching practice | Physically distanced alternative teaching practices |

|---|---|

| Walking around the room during independent work time | -Observing students from the front of the room |

| -Have students complete work using Google Docs and observing their work from your own computer | |

| -Students use Nearpod at their desks | |

| 1:1 conferences with students at the teacher’s desk to support learning and behavior needs | -1:1 meetings with students using Google Meet or Zoom. Teachers and students can sit at their own desks and use headphones with a built-in microphone to hold a private conference. This same strategy may be used for individual student testing, such as DIBELS or DRA reading assessments |

| High 5 or pat on the back as positive feedback | -Thumb-up from across the room |

| -Holding up a card that says “good work” with a smiley face icon | |

| -Positive verbal praise | |

| -Air high fives or tell students to give themselves a pat on the back | |

| -Have students to choose or create their own way to receive positive feedback |

Providing Feedback

After children have received explicit instruction on behavioral expectations, teachers need to provide specific feedback on student behaviors by providing positive reinforcement to support behavior change (Alberto & Troutman, 2012). Feedback can be provided using visuals (e.g., thumbs up, a green checkmark) for general praise statements in the hyflex environment to ensure students know that what they are doing is correct.

Behavior-specific praise (BSP) occurs when a teacher verbally acknowledges that a child, or the entire class, is meeting the behavioral expectation by providing explicit feedback on the exact behavior the student performed using the child’s name, the skill, and what they did to earn the feedback. BSP increases the likelihood that students will repeat the specific behavior. BSP can be used for students when they social distance appropriately through feedback (Markelz & Taylor, 2016). For example, rather than telling a student “good job, telling a student, “Giovanni, you did a great job pushing your chair in and waiting patiently at your desk to be called for lineup,” gives the student positive feedback on the specific task they did correctly, and encourages that behavior in the future. Teachers can also provide socially distanced behavior specific praise to students nonverbally by using visual cues such as laminated pictures with specific icons to clue students in to the behavior they did correctly. In the hyflex environment, BSP delivery can be delivered verbally or in the chat feature of the online classroom.

Feedback might include behavior-specific praise, a reminder of the expectations when students are not following them, or a corrective statement (Stormont et al., 2008). Corrective statements, sometimes referred to as reprimands, are used to remind a child of the expected behavior when he or she is not meeting expectations. Reprimands should be used sparingly and teachers should aim for a 9:1 ratio of praise statements to reprimands (Caldarella et al., 2019).

Another quick feedback strategy that can be used to let students know what behavior is expected of them before they do it is precorrection. Precorrection can be modeled for students, and students can provide teachers with precorrection. Research (Schuch & Tipper, 2007) shows that the act of observing others can help learners become more aware of their own behaviors. For example, teachers can ask students to provide feedback on physical distancing behaviors before transitioning from the classroom to the cafeteria, by requesting details on the teacher’s expected behavior. Precorrection is delivered in a form of action-oriented language, but it can also be provided nonverbally by using icons and checklists, especially during unstructured times, such as transition and free play, which can be chaotic and where young children are typically in close physical contact. Precorrection can be provided utilizing visuals (e.g., 6 feet apart, a mask icon, muted microphone icon) to young children during hyflex learning.

Feedback can also be provided to young children as a redirection. Redirection should be used when students are presenting aggressive behaviors, or precursors (i.e., triggers) for aggressive behaviors, that can be unsafe to themselves or others in a classroom.

Additionally, teachers can use redirection when young children are too emotional to control their behaviors or when they continually struggle to make good choices and need assistance from the teacher (Responsive Classroom, 2014) to regulate their behavior and display appropriate behaviors that meet the classroom expectations. Redirecting language needs to be provided with a specific and simple statement of expected action, clearly telling students what to do, rather than what the student should not do. Nonverbal communication from teachers also plays an essential role in redirection. While teachers need to use a direct and specific statement when redirecting students, they are encouraged to say it gently but firmly to maintain neutrality in their nonverbal messages, including facial expressions and tone of voice (Responsive Classroom, 2014). The Feedback Statements chart provides examples of whole-class and individual feedback that teachers might use to address physical distancing expectations (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Sample feedback statements

| Situation | Feedback to the entire class | Feedback to an individual student |

|---|---|---|

| Praise for appropriate social distancing | I like that you are staying at your own desks. Good work! | Raul, you are doing a fantastic job of giving Jose personal space. I know that he is your best friend and that you love hanging out with him. Thank you for respecting his space |

| Gentle reminder when children are not following guidelines | I am noticing that you are sitting very close to one another on the rug. Please remember to give one another personal space | Keisha, I see that you are having a hard time keeping your hands away from Lilah’s body. Please remember to respect her personal space |

| Gentle reminder before behavior occurs/pre-correction | We are getting ready to go to recess. Thank you for respecting one another’s personal space in the hallway | Francesco, thank you for keeping your hands off your friends’ desks as you walk to the door |

| Use redirection when students present unsafe behaviors in meeting classroom expectations | Everyone, step on the footprints on the floor for a line-up. Then we’ll go outside | Olivia, sit on your spot on the rug so you can keep your distance |

Conclusion

COVID-19 has led to unanticipated changes for schools, and for young children. The introduction of online and hyflex instruction created new challenges for teachers and students alike. While the hybrid and hyflex environment are a challenge, they provide students access to instruction they are missing when they are unable to attend school. Despite the changes to their traditional teaching routine, teachers can use best practices in instruction and classroom management to support students in meeting health and safety guidelines. In order to support students in meeting the requirements for physical distancing in the classroom and school setting, we suggest explicitly teaching expectations, the teacher modeling expectations, and timely feedback on student actions. It is important to note that young children will have a variety of unique needs in the hyflex classroom, so teachers must be flexible with classroom management tools and instruction. It is imperative that teachers stay up-to-date on best practices in hyflex instruction. Helpful Resources provides a variety of resources for teachers during COVID-19 (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Helpful web resources for educators

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Marla J. Lohmann, Email: MLohmann@ccu.edu

Kathleen M. Randolph, Email: krandolp@uccs.edu

Ji Hyun Oh, Email: joh@uccs.edu.

References

- Alberto PA, Troutman AC. Applied behavior analysis for teachers. 9. Prentice Hall; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Archer AL, Hughes CA. Explicit instruction: Effective and efficient teaching. Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Beatty B. Hybrid courses with flexible participation: The HyFlex course design. In: Kyei-Blankson L, Ntuli E, editors. Practical applications and experiences in K-20 blended learning environments. IGI Global; 2014. pp. 153–177. [Google Scholar]

- Bell J, Sawaya S, Cain W. Synchromodal classes: Designing for shared learning experiences between face-to-face and online students. International Journal of Designs for Learning. 2014;5(1):68–82. doi: 10.14434/ijdl.v5i1.12657. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Binneweis S, Wang Z. Challenges of student equity and engagement in a hyflex course. In: Allan CN, Shurety W, Crough J, editors. Blended learning designs in STEM higher education. Springer; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks JT, Butler JC, Redfield RR. Universal masking to prevent SARS-CoV-2 transmission—The time is now. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2020;324(7):635–637. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.13107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brophy J. History of research on classroom management. In: Evertson CM, Weinstein CS, editors. Handbook of classroom management: Research, practice, and contemporary issues. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2006. pp. 17–43. [Google Scholar]

- Caldarella P, Larsen RAA, Williams L, Wills HP, Wehby JH. Teacher praise-to-reprimand ratios: Behavioral response of students at risk for EBD compared with typically developing peers. Education and Treatment of Children. 2019;42(4):447–468. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2020.1711872. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Considerations for schools: Operating schools during COVID-19. Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/schools-childcare/schools.html

- Dunlap G, Wilson K, Strain P, Lee JK. Prevent teach reinforce for young children: The early childhood model of individualized positive behavior support. Brookes Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2020). FBI warns of teleconferencing and online classroom hijacking during COVID-19 pandemic. Retrieved from https://www.fbi.gov

- Ferri F, Grifoni P, Guzzo T. Online learning and emergency remote teaching: Opportunities and challenges in emergency situations. Societies. 2020;10(4):86. doi: 10.3390/soc10040086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gage NA, Scott T, Hirn R, MacSuga-Gage AS. The relationship between teachers’ implementation of classroom management practices and student behavior in elementary school. Behavioral Disorders. 2018;43(2):302–315. doi: 10.1177/2F0198742917714809. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garbe A, Ogurlu U, Logan N, Cook P. COVID-19 and remote learning: Experiences of parents with children during the pandemic. American Journal of Qualitative Research. 2020;4(3):45–65. doi: 10.29333/ajqr/8471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garwood JD, Vernon-Feagans L. Classroom management affects literacy development of students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Exceptional Children. 2017;83(2):123–142. doi: 10.1177/2F0014402916651846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix MJ, Walde C, Findley K, Trotman R. Absence of apparent transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from two stylists after exposure at a hair salon with a universal face covering policy. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2020;69:930–932. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6928e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner RH, Sugai G. School-wide positive behavior support: An alternative approach to discipline in schools. In: Bambara L, Kern L, editors. positive behavior support. Guilford Press; 2005. pp. 359–390. [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Liu Y, Li M, Qian X, Dai SY. Mask or no mask for COVID-19: A public health and market study. PLoS ONE. 2020 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch R, Garrett PM. ‘More than words’: Touch practices in child and family social work. Child & Family Social Work. 2010;15(4):389–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2206.2010.00686.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Markelz AM, Taylor JC. Effects of teacher praise on attending behaviors and academic achievement of students with emotional and behavioral disabilities. Journal of Special Education Apprenticeship. 2016;5(1):1. [Google Scholar]

- Mundy P, Casari C, Sigman M, Ruskin E. Nonverbal communication and early language acquisition in children with down syndrome and in normally developing children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1995;38(1):157–167. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3801.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Responsive Classroom. (2014). Reinforcing, reminding, and redirecting. Retrieved from https://www.responsiveclassroom.org/reinforcing-reminding-and-redirecting/

- Samee Ali, S. (2020). Educators teaching online and in person at the same time feel burned out. Retrieved October 18, 2020, from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/educators-teaching-online-person-same-time-feel-burned-out-n1243296

- Schiefele U. Classroom management and mastery-oriented instruction as mediators of the effects of teacher motivation on student motivation. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2017;64:115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schuch S, Tipper SP. On observing another person’s actions: Influences of observed inhibition and errors. Perception & Psychophysics. 2007;69(5):828–837. doi: 10.3758/bf03193782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stormont M, Lewis TJ, Beckner R, Johnson NW. Implementing positive behavior supports in early childhood and elementary settings. Corwin Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stronge JH, Ward TJ, Grant LW. What makes good teachers good? A cross-case analysis of the connection between teacher effectiveness and student achievement. Journal of Teacher Education. 2011;62:339–355. doi: 10.1177/2F0022487111404241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Department of Education. (2020). FERPA and virtual learning during COVID-19. Retrieved from https://studentprivacy.ed.gov/sites/default/files/resource_document/file/FERPAandVirtualLearning.pdf

- Whiddon, M. A., & Montgomery, M. J. (2011). Is touch beyond infancy important for children’s mental health? VISTAS Online, 11, Article 88. Retrieved from http://counselingoutfitters.com/vistas/vistas11/Article_88.pdf