Abstract

The US National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Natural Product Repository is one of the world’s largest, most diverse collections of natural products containing over 230,000 unique extracts derived from plant, marine, and microbial organisms that have been collected from biodiverse regions throughout the world. Importantly, this national resource is available to the research community for the screening of extracts and the isolation of bioactive natural products. However, despite the success of natural products in drug discovery, compatibility issues that make extracts challenging for liquid handling systems, extended timelines that complicate natural product-based drug discovery efforts and the presence of pan-assay interfering compounds have reduced enthusiasm for the high-throughput screening (HTS) of crude natural product extract libraries in targeted assay systems. To address these limitations, the NCI Program for Natural Product Discovery (NPNPD), a newly launched, national program to advance natural product discovery technologies and facilitate the discovery of structurally defined, validated lead molecules ready for translation will create a prefractionated library from over 125,000 natural product extracts with the aim of producing a publicly-accessible, HTS-amenable library of >1,000,000 fractions. This library, representing perhaps the largest accumulation of natural-product based fractions in the world, will be made available free of charge in 384-well plates for screening against all disease states in an effort to reinvigorate natural product-based drug discovery.

Graphical Abstract

Natural products are composed of relatively few elements—carbon, hydrogen, oxygen and an occasional nitrogen, sulfur or halogen—yet the molecular complexity and collective diversity of natural product scaffolds, which are driven by the continual evolution of the biosynthetic genes that produce compounds that interact with the unique three-dimensional structures of nucleic acids and proteins in cellular pathways, provide unparalleled opportunity for drug discovery efforts.1 The value is further demonstrated by the significant proportion of small-molecule approved drugs from 1981 to 2014 in disease areas such as cancer (>60%) that were developed from a natural product or were based on a natural product pharmacophore.2 This ratio is especially impressive given the relatively low percentage (<1%) of natural products screened in high-throughput screening (HTS) campaigns during this time period.3 Furthermore, despite increased research and development spending and a recent emphasis to include more compounds with lead-like and drug-like properties,4–8 fewer than 20% of the core ring scaffolds present in natural products are represented in commercially available synthetic collections.9 Thus, a potential solution to improving the efficiency of drug discovery efforts would be the inclusion of larger numbers of natural product scaffolds, or derivatives thereof, in HTS campaigns.

As the US National Cancer Institute (NCI) has amassed one of the largest, most diverse collections of natural product extracts in the world (Figure 1) and has a mission to stimulate anticancer drug discovery, the question was how to generate a greater integration of natural products in HTS efforts? Although this national resource is available to the research community for the screening of extracts and the isolation of bioactive natural products, screening crude natural product extracts involves testing complex mixtures of compounds of unknown molecular weight with variable polarity, solubility, and stability, which can cause potential assay interference, toxicity, and liquid handling problems in many modern HTS platforms. Toward that end, the NCI Experimental Therapeutics Program (NExT) Chemical Biology Consortium sponsored a workshop to bring together biological screeners and natural product chemists to discuss strategies for the better integration of natural products into screening programs.10 This discussion led to the determination that improvements in the quality of the screening libraries provided by the NCI (i.e., partial purification or prefractionation) and others, along with enhancements in the processes and timelines of NP chemistry efforts, would be necessary to be able to engage the screening centers in the most productive manner.

Figure 1.

(A) Collection locations of marine organisms (blue), plants (green), and microbial specimens (red) that comprise the US National Cancer Institute’s Natural Product Repository. The size of the hexagon is indicative of the relative size of the individual collection, and locations with more than one type of collected organism are shaded in gray. Since 1986, samples collected through the NCI Natural Products Collection program have been acquired through collection agreements based on the NCI Letter of Collection with each participating source country or their representatives, which stipulates equitable benefit sharing from commercial products derived from discoveries made through these collections. Plant specimens have been collected in over 25 countries through contracts with the Missouri Botanical Garden (Africa and Madagascar), the New York Botanical Garden (Central and South America), the University of Illinois at Chicago (Southeast Asia), and the Morton Arboretum and World Botanical Associates (United States and territories). Marine organisms have been collected throughout the world through contracts with SeaPharm, the Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute, the Australian Institute of Marine Science, the University of Canterbury, New Zealand, and the Coral Reef Research Foundation based in Palau in Micronesia. Microbial collections were first obtained through an initial contract with the University of Connecticut and then from the middle 1990s, through collaborations with the United States Department of Agriculture.17,18 (B) Overview of the automation procedure developed to facilitate the production of the NPNPD fraction library: (1) Extracts from the NCI Natural Products Repository are weighed and reconstituted in either organic solvent or water. (2) Dissolved extracts are adsorbed onto cotton rolls contained within an empty SPE cartridge, while 2D-barcoded tubes (10 mL) are preweighed on an automated weighing station (2 h). (3) Extracts (n = 88) are prefractionated on a customized positive pressure solid phase extraction workstation (ppSPE) with two robotic arms working in parallel to produce seven fractions per extract (3.5 h; n = 616 fractions). (4) Fractions are dried using high-performance centrifugal evaporation systems (18 h) and the final mass of each fraction is determined on an automated weighing station (2 h). (5) Assay plates containing fractions and unprocessed extracts are generated from each set of 88 extracts (2 × 384-well plates).

Prefractionated natural product extracts typically show enhanced biological activity due to improved screening performance (often observed as a higher confidence in observed hit rates) and the concentration of active components present as only minor metabolites, as well as streamlined downstream processes for dereplication and the isolation of bioactive components.11–14 In fact, a number of private, prefractionated natural product libraries have been established to date, ranging in numbers from a few hundred to greater than 30,000 prefractionated natural product extracts.11,15,16 Herein, we outline the methods development for the prefractionation of >125,000 extracts from the NCI’s Natural Product Repository extract library as part of the NCI Program for Natural Product Discovery (NPNPD) with the aim of accelerating natural-product based drug discovery by producing a publicly accessible, HTS-amenable library of natural product samples (1,000,000 fractions), which will be made available free of charge in 384-well plates to researchers for screening against any disease.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

NCI Natural Products Repository (NPR) Extracts.

Extracts in the NCI NPR are prepared using both an aqueous and organic solvent extraction process, resulting in two sequential extracts per collected specimen.19 Importantly, depending on the source material, the order in which the aqueous extract is generated significantly influences the final composition of the extract. For plant specimens, the organic extract is produced prior to the water extract using a solvent mix of 1:1 dichloromethane (DCM)/methanol (MeOH), followed by 100% MeOH, resulting in an organic extract enriched in both nonpolar and midpolarity components. In contrast, marine organisms are first extracted with water, which removes salts and polysaccharides, followed by an organic solvent extraction (1:1 DCM/MeOH) of the lyophilized biomass. There are currently more than 30,000 microbial extracts in the NCI NPR that have been derived from fungal and bacterial fermentations grown under varying conditions. To disrupt cells and mat-like material, organic extracts are prepared from high-shear homogenized cultures in 10% MeOH (v/v), followed by partitioning with 50% DCM. The filtered aqueous layer (~1 L) is then lyophilized to create an aqueous extract.

NPR Prefractionated Library Design.

To develop a natural-products-based fraction library that is not only well-adapted to HTS but also captures the diversity of the NCI NPR, several essential criteria were considered during the methods development process. Importantly, platforms that could accommodate 0.2–1.0 g loading of each extract providing enough material within each fraction for generating a large number of HTS plates and be adapted for high-throughput processing were needed. In this regard, the versatility and high-throughput potential of solid-phase extraction (SPE) methods such as those typically used for sample extraction, concentration, and cleanup were considered over high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) or supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC) prefractionation strategies that, by comparison, have a decreased loading capacity, lower throughput, and limited sample collection formats for determining the mass of each fraction. Another advantage of using SPE is the potential to generate a small set of fractions (5 to 10) for each extract that covers a diverse range of metabolites with regards to polarity and thus maximize the coverage of chemical and biological diversity screened within a given HTS campaign. As the goal was the prefractionation of >125,000 crude extracts, the methodologies chosen also had to be optimized for both cost and throughput. However, prior to developing a SPE-based prefractionation method that could be readily adapted to an automated, high-throughput robotics platform (Figure 1B), techniques to address the logistics of sample loading, elution, drying, and weighing were developed. First, the relatively large starting mass of each extract presented significant challenges with regards to sample reconstitution and automated liquid handling loading due to sample viscosity and precipitation, which also impacted the reproducibility of the SPE sample loading and elution techniques. However, after some preliminary experimentation, dissolving 200–250 mg of the organic solvent extracts or 400–1000 mg of the aqueous extracts in 4.5 mL of MeOH/EtOAc/MTBE (6:3:1) or 100% H2O, respectively, followed by directly adsorbing onto a cotton plug and freeze-drying, resulted in a high-throughput amenable loading technique with minimal clogging of the SPE frit and matrix. This dry-loading technique, whereby the freeze-dried, cotton-adsorbed samples are housed in a separate cartridge also allows the SPE adsorbent to be pre-equilibrated following the manufacturer’s recommended guidelines. Next, it was determined that a controlled rate of elution (<10 mL/min), which could be achieved with an individualized positive pressure system (i.e., manually from a top-loaded syringe or robotically with a fixed pipet tip), aided in preventing the drying and cracking of the SPE adsorbent. Based on the initial methods development, a customized positive pressure solid phase extraction (ppSPE) workstation was designed with two robotic arms working together to process 44 extracts each, resulting in 616 total fractions. Importantly, the fractions from the ppSPE system are collected into 10 mL 2D-barcoded tubes, allowing the dried fractions to be tracked and weighed on an automated weighing station and ultimately screened at a known concentration (Figure 1B).

NPR Prefractionated Library Methods Development.

With the goal of developing a standard SPE protocol that could be adapted for the automated ppSPE system, a diverse subset of plant, marine, and microbial extracts (both aqueous and organic) was selected to construct a model prefractionated library for method evaluation (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1). These included different phyla for each extract source, as well as variations in collection type for the plant extracts (e.g., roots, bark, twigs, and leaves). Several specialized SPE stationary phases including diol (2,3-dihydroxypropoxypropyl, nonend-capped functionalized silica), wide-pore C4 (butyl, nonend-capped), and C8 (octyl, nonend-capped) were evaluated based on their ability to separate highly lipophilic components from midpolarity compounds, while some of the more traditional stationary phases such as C18 and silica were excluded from this pilot study based on prior knowledge and experience acquired from prefractionating NCI NPR extracts.11 Although fractions are considerably less complex than crude extracts and often concentrate minor metabolites, “nuisance compounds” such as polyphenolics may also be concentrated, which can lower the quality of confidence in the active fractions identified.20,21 A common strategy employed for the removal of large polyphenolic tannins from plant extracts prior to prefractionation relies on the irreversible binding properties of polyamide resin.22–24 However, the total polyphenolic content within plant extracts can vary substantially and may comprise upward of 40–60% of the total extract mass.23,25 Thus, large sample-to-resin ratios are often required; with the extent of adsorption influenced by the proportion of condensed and hydrolyzable tannin content present, differences in plant genera, and adsorption techniques used.26,27 Furthermore, polyamide may also remove highly oxygenated, potentially unknown active compounds, as well as polyphenols of biomedical interest within the anthocyanidin, coumarin, and flavonoid groups.28–30 Therefore, techniques that could potentially sequester a large portion of the total phenolic content away from active principles without the need for sample pretreatment were explored, such as those used previously to characterize wine tannins and include the use of copolymer-based SPE matrices.31,32 Based on their universal application for acidic, neutral, and basic compounds, as well as enhanced retention of polar analytes, the polymeric adsorbents used in this study included Oasis HLB (hydrophilic–lipophilic-balanced divinylbenzene, N-vinylpyrrolidone copolymer) and Bondesil ENV (hydroxylated polystyrene divinylbenzene copolymer). Additionally, two mixed-bed SPE columns containing either HLB with C4 (aqueous extracts) or C8 (organic extracts) were investigated for their chromatographic potential to separate a broad range of analytes on a single SPE column.

Table 1.

Overview of the Extracts, Solvents, and Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Adsorbents Investigated for the NPR Model Prefractionated Library

| Polarity | Normal Phase (NP) | Reversed-Phase (RP) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stationary Phasea | Diol | C4 | C8 | ENV | HLB | C4/HLB | C8/HLB | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Solvent Seriesb | 1 (Hex/DCM) |

2 (Hex) |

1 ACN/H2O |

2 MeOH/H2O |

1 ACN/H2O |

2 MeOH/H2O |

1 ACN/H2O |

2 MeOH/H2O |

1 ACN/H2O |

2 MeOH/H2O |

1 ACN/H2O |

2 MeOH/H2O |

1 ACN/H2O |

2 MeOH/H2O |

||||||||||||||||

| Extract Sample | Fraction # | 7 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 10 | |

| Aqueousc | Marine Organisms | Biemna sp. (sponge) | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||

| Moorea sp. (cyanobacterium) | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Goniopora lobata (stony coral) | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Xestospongia testudinaria (sponge) | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jaspis splendens (sponge) | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sigmadocia sp. (sponge) | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Organticd | Plakortis lita (sponge) | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||

| Codium fragile (green algae) | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Moorea sp. (cyanobacterium) | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Plants | Euphorbiaceae Fluegga virosa (root) | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||

| Olacaceae Olax scandens (leaf) | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Proteaceae Conospermum stoechadis (stem) | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Rubiaceae Exostema caribaeum (bark) | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Microbial | Streptomyces hygroscipus (bacterium) | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||

| Aspergillus fumigatus (fungus) | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Pénicillium duclauxi (fungus) | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||

Stationary phases: Isolute diol (2,3-dihydroxypropoxypropyl, nonend-capped functionalized silica: 50 μm, 60 Å); Bakerbond Wide-Pore C4 (butyl, nonend-capped: 50 μm, 60 Å); HyperSep C8 (octyl, nonend-capped: 50 μm, 60 Å); Isolute C8 (octyl, nonend-capped: 50 μm, 60 Å); Bondesil ENV (hydroxylated polystyrene divinylbenzene copolymer; 125 μm); Oasis HLB (hydrophilic–lipophilic-balanced divinylbenzene, N-vinylpyrrolidone copolymer; 60 μm).

Normal phase solvent series included either a stepped gradient from Hex/DCM to EtOAc to MeOH (1) or from Hex to EtOAc to MEOH (2), while reversed-phase solvent series compared stepped gradients of decreasing polarity using either ACN/H2O to ACN/DCM or MeOH/H2O to MeOH/DCM.

Aqueous extracts included in this study were prepared from 100% water.

Organic extracts were prepared from a solvent mix of 1:1 DCM/MeOH (plants and marine organisms), followed by 100% MeOH (plants). Microbial organic extracts were prepared from 10% MeOH (v/v), followed by partitioning with 50% DCM. Abbreviations: ACN, acetonitrile; DCM, dichloromethane; EtOAc, ethyl acetate; Hex, hexanes; MeOH, methanol.

Finally, to facilitate sample tracking within an HTS plate map, standard screening plate formatting standards were used as a guide for refining the number of SPE fraction combinations that would be produced for each extract in the model library, so as to ensure that extracts and their corresponding fractions would be easily deconvoluted from screening results. Of the possible fractionation schemes that would fit within these guidelines, a series of either 7 or 10 total fractions per extract was preferred over smaller sets of fractions to balance the complexity and mass of each fraction with the chromatographic potential of the SPE adsorbents. These fraction numbers also allowed for eventual 384-well plate formatting while leaving suitable space for screening controls. Thus, with wells set aside for assay controls, a set of two 384-well assay plates would contain either 64 or 88 total crude extracts and their corresponding fractions. Accordingly, the organic solvent extracts were separated into seven fractions on HLB, C8, or C8/HLB stationary phase using several reversed-phase (RP) solvent schemes with the aim of comparing a method that used acetonitrile (RP-1.7) to an alternative solvent series using methanol (RP-2.7), each of which were expanded to include a 10-fractionation series (RP-1.10 and RP-2.10; Table 1 and Supplementary Table S2, respectively). Additionally, the organic extracts were separated on a diol stationary phase using four different normal phase (NP) solvent schemes that were based on elution strength values of binary solvent mixtures (Supplementary Table S2).33 The aqueous extracts were prefractionated on HP-20, HLB, ENV, C4, or C4/HLB using the same reversed-phase solvent schemes employed for the organic extracts. However, prior to collecting the first fraction within each series, six bed volumes of 100% H2O (12 mL) were flushed through each sample and SPE cartridge to aid in the removal of salts and polysaccharides from the marine aqueous extracts (Supplementary Table S2).

Analysis of the Model NPR Prefractionated Library.

To evaluate the applicability of SPE to generate an HTS-amenable library of prefractionated natural product extracts, each method was assessed based on several measurable parameters. The first was the distribution of mass within each fractionation series, with at least 2 mg (5 mg preferred) for each fraction as a goal for generating up to 200 screening test plates (10 μg of material per well, respectively) from a single prefractionated extract. Overall, a relatively even distribution of mass, with most fractions containing ≥10 mg, was observed for each of the 7-series fractionation schemes (Table 2). In contrast, each of the corresponding 10-series fractionation schemes exhibited a significant decrease in the number of fractions containing ≥10 mg, with a 50% increase in the percentage of fractions at or below the desired 5 mg threshold. Thus, from the perspective of covering a diverse range of metabolites with enough material available to screen in a larger number of HTS campaigns, the 7-series fractionation schemes seemed preferable. Further analysis revealed that the diol stationary phase accounted for most of the fractions containing less than 5 mg for each of the organic solvent extracts (Supplementary Table S3). These low yields were somewhat expected considering that diol is routinely used to remove waxy or lipophilic components in the early, nonpolar eluents, and thereby potentially unmasking bioactive compounds of interest within the mid- to moderate polarity region.11,34 For the aqueous extracts, the C4 and C8 stationary phases performed better than the polymeric adsorbents (ENV and HLB) with regards to the number of fractions containing less than 5 mg (Supplementary Table S3). Additionally, it was determined that an increase in the mass of each extract from 0.4 to 1 g (necessitated by the large amount of NaCl in these extracts) resulted in a 30-fold reduction in the percentage of fractions at or below the 5 mg threshold (Supplementary Table S3), which would ultimately support a larger number of future HTS campaigns.

Table 2.

Comparison of the Mass Distribution for the 7 versus 10 Fractionation Series Investigated for the Organic Extracts in the Model NP Library

| % of total fractions | % recovery | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 2 mg | 2–5 mg | 5–10 mg | ≥10 mg | Avg (SD) | |

| Organic Extractsa | |||||

| Plants: | |||||

| 7 fractions | 11.2 | 10.2 | 16.8 | 61.7 | 87.7 (12.7) |

| 10 fractions | 11.8 | 16.8 | 22.1 | 49.3 | 87.7 (10.1) |

| Microorganisms: | |||||

| 7 fractions | 20.2 | 9.2 | 16.0 | 54.6 | 96.8 (2.9) |

| 10 fractions | 34.0 | 10.0 | 14.0 | 42.0 | 95.2 (4.4) |

| Marine Organisms: | |||||

| 7 fractions | 4.8 | 21.9 | 16.2 | 57.1 | 91.3 (7.8) |

| 10 fractions | 11.3 | 26.7 | 18.7 | 43.3 | 96.9 (1.8) |

| Aqueous Extractsb | |||||

| Marine Organisms: | |||||

| (set 1) 7 fractions | 30.2 | 31.8 | 24.6 | 13.5 | 10.1 (5.2) |

| (set 1) 10 fractions | 37.8 | 38.3 | 18.9 | 5.0 | 9.8 (4.9) |

| (set 2) 7 fractions | 1.9 | 22.9 | 27.6 | 47.6 | 16.7 (8.9) |

The organic extracts were prefractionated using 0.2 g of starting material.

The marine aqueous extracts were prefractionated using either 0.4 g (set 1) or 1.0 g (set 2) of starting material.

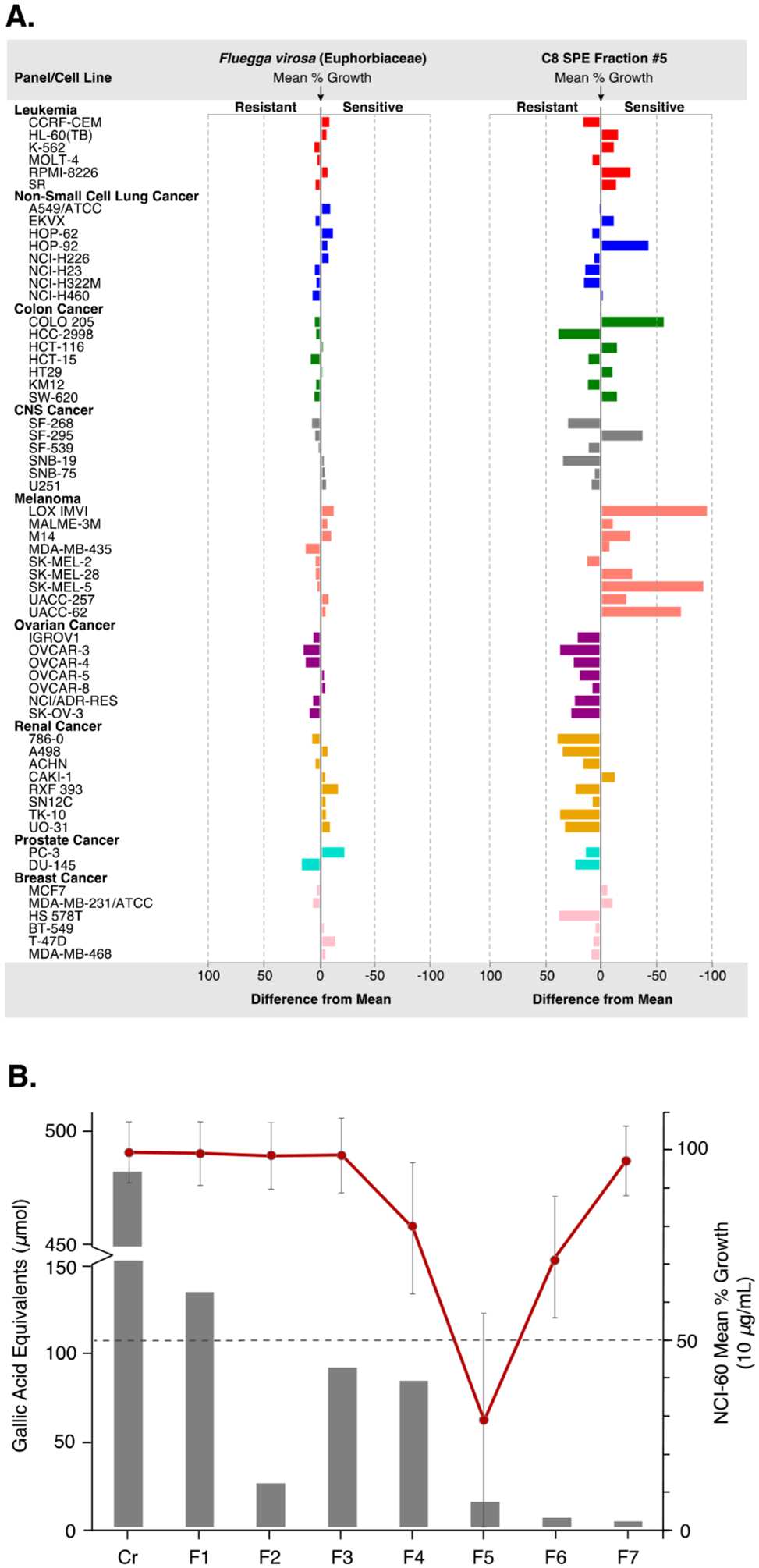

The model library of SPE fractions, comprising more than 2,000 fractions and their respective parent extracts, was screened in the NCI-60 Human Tumor Cell Lines Screen35–37 and in several biochemical assays including those for inhibition of the protease MALT1 (unpublished results), the kinase p38,38 and the phosphodiesterase TDP139 with the aim of identifying prefractionation methods that showed (1) fractions with enhanced biological activity relative to the parent extract, (2) concentration of active components across fractions, and (3) a higher confidence in observed hits. For the plants included in this study, each of the parent organic extracts were inactive in the screening assays, and only one extract, a Thai collection of Fluegga virosa (Euphorbiaceae), exhibited activity in the fractions. A comparison of the NCI-60 active fractions of F. virosa from C8, HLB, and C8 + HLB showed that the activity was spread across three to four fractions with the RP-1.7 solvent scheme, while the RP-2.7 series concentrated the active components (Supplementary Tables S5–S9). Notably, a single fraction from the C8, RP-2.7 scheme of F. virosa showed selective activity against the melanoma cell line panel in the NCI-60 screen (Figure 2A). A similar pattern was observed in the active marine and microbial extracts, demonstrating that the RP-2.7 method was better at concentrating the activity of these extracts (Supplementary Tables S10–S34). Overall, the cytotoxicity and biochemical activity of the fractions for each of the marine and microbial organic extracts was significantly enhanced over their respective crude extracts, providing evidence that fractionation prior to screening can result in the identification of active natural products that would otherwise be missed.

Figure 2.

(A) Differences in mean percent growth against the NCI-60 human tumor cell lines panel (10 μg/mL) for the plant organic solvent extract of Fluegga virosa (, delta = 20.88, range = 35.80) and corresponding active fraction 5 (, delta = 94.68, range = 132.50) from the C8, RP-2.7 scheme. Fraction 5 showed greater overall inhibition of mean cell growth and selectivity against several melanoma cell lines (difference from mean = mean growth percent – growth percent). (B) Comparison of the total phenolic content of the C8, RP-2.7 fractions with the corresponding NCI-60 bioassay data shows that the polyphenolics are concentrated in F1–4, providing an increased confidence in the observed activity of fraction 5. Dashed line = activity threshold at a mean cell growth of ≤50% compared to the control.

A major concern with screening natural product extracts is that assay interfering compounds such as polyphenols (tannins) can lower the confidence of the observed hits.3 Thus, to verify the active fractions of F. virosa and to further assess each of the methods investigated, the total phenolic content was measured for the prefractionated plant extracts using a modified Folin–Ciocalteu (F–C) assay.40,41 As shown in Supplementary Tables S35 and S36, an interesting pattern of the total phenolic distribution was observed among the SPE adsorbents investigated. For each of the plant extracts, 80 to 90% of the recovered phenolics were concentrated within the first four fractions of the C8, RP-2.7 prefractionation schemes, while most of the tannin content from the HLB and diol adsorbents were present in the late eluting fractions (5 to 7). The practical implications of these results are best illustrated by the bioassay results for F. virosa. In the C8, RP-2.7 prefractionation method, the F. virosa fraction eluting with 80% MeOH–H2O (fraction 5), which was active against the NCI-60 cell line panel, contained only 4% of the total phenolic content recovered (Figure 2B and Supplementary Tables S5 and S35), indicating that the C8, RP-2.7 prefractionation method can sequester this well-known class of nuisance compounds away from active constituents of mid- to moderate polarity and therefore reduce the need for polyamide pretreatment.

As previously shown, the C8, RP-2.7 prefractionation method also concentrated the minor active constituents of the organic extracts. Thus, the C8, RP-2.7 method was compared to C4, HLB, and Diaion HP-20 stationary phases using several aqueous extracts that had exhibited activity against the NCI-60 cell line panel. Similar to the organic extract fractions, the C8 SPE material concentrated the activity of the aqueous extracts to fewer fractions than each of the other SPE matrices investigated (Supplementary Tables S37–S51). A notable example of this was observed with the aqueous extract of a bengamide and bengazole producing sponge Jaspis splendens, which showed NCI-60 active fractions in most of the C4, HLB, and HP-20 fractions, while the C8 SPE activity was contained in the 80 and 100% MeOH fractions, as well as the final wash (Supplementary Tables S37–S41). Furthermore, the aqueous extract obtained from a New Zealand collection of the sponge Sigmadocia sp. showed enhanced NCI-60 activity in one of the C8 SPE fractions with a mean percent growth inhibition of 63% relative to the control at 10 μg/mL, while the HLB fractions did not cross the activity threshold (i.e., growth inhibition). Notably, each of the C4 and HP-20 fractions of this extract were inactive (Supplementary Tables S42–S46). Additionally, analogous to the organic extract of the plant F. virosa, the unfractionated aqueous extract of the sponge Xestospongia testudinaria was inactive, while the fractions of the same extract from C8 and HLB exhibited selectivity against the HL-60(TB) human leukemia cell line in the NCI-60 assay (Supplementary Tables S47–S51), further demonstrating the ability to identify active, low abundance compounds by fractionating extracts prior to screening.

Finally, samples from each of the RP-2.7 schemes were subjected to ultraperformance liquid chromatography coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometry (UPLC–HRMS) and subsequently compared using multivariate statistical modeling. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on the UPLC–HRMS data set and comprised retention time (RT), mass-to-charge ratio (m/z), and intensity to identify correlations within the groupings of fractions from each of the methods investigated. Although the PCA scores plot showed significant separation (p < 0.05) between the fractions (i.e., fractions separated based on polarity) for each RP-2.7 prefractionation scheme, neither adsorbent (C8, HLB nor the mixed-bed SPE) could be readily distinguished from the other based on comparisons of their respective LCMS-PCA scores plots (Figures 3A–C and Supplementary Figures S1–12). As an extension of PCA, which attempts to maximize the amount of variance explained in a data set by combinations of independent variables (components), Partial Least Squares Regression (PLS) explains variance within the context of a response variable (i.e., activity) and is often used in metabolomic analysis given the noisy, highly correlated nature of LC/MS data.42,43 Thus, each component (or score) of a PLS will be groups of m/z-RT pairs that contribute in varying degrees to activity. By integrating the NCI-60 assay data with combined UPLC–HRMS data for each adsorbent, the resulting PLS scores plots distinguished fractions based on their activity and, in general, showed better separation among the C8 fractions (Figure 3D and Supplementary Figures S13–19). In the PLS scores plot for F. virosa (Figure 3D), the fractions located in the lower left region contained varying degrees of activity (Supplementary Tables S5–S9). A presence–absence analysis of the m/z-RT pairs of these fractions identified two metabolites at m/z 597.16 (phyllanthusmin D, 1) and m/z 657.34 (dichapetalin, 2), subsequently found to be responsible for the observed in vitro activity, which were present in the active C8, RP-2.7 fraction at nearly 2 and 15 times the relative abundance of the C8/HLB mixed-bed and HLB SPE fractions, respectively (Supplementary Figure S20). This finding is consistent with the bioassay data and suggests that the HLB material, either alone or in combination with C8, retains 1 and 2. A similar result was observed for the active fractions from the marine organic solvent extract of the sponge Plakortis lita (Supplementary Figure S21). Therefore, based on the UPLC–HRMS data, together with the preceding assessments, the C8, RP-2.7 scheme was selected as the prefractionation method for generating the NPNPD fraction library.

Figure 3.

Principal component analysis (PCA) based on the UPLC–HRMS data of the fractions from the plant organic solvent extract of Fluegga virosa (Euphorbiaceae) using C8 (A), HLB (B), and C8/HLB mixed (C) SPE adsorbents and the RP-2.7 solvent scheme. The 95% confidence ellipses are displayed for each fraction data set. In general, between 40–49% of the variability is represented by the first principal component, which is largely due to variance in molecular size and polarity. (D) Partial least-squares (PLS) scores plot shows the inactive fractions (open symbol) for each of the SPE adsorbents investigated with the RP-2.7 solvent scheme largely clustered in the upper right region, while several bioactive fractions (solid symbol) are distributed in the lower left quadrant.

Automated NPR Prefractionation Workflow and Validation.

An overview of the high-throughput automation platforms used to facilitate the production of the NPNPD fraction library is shown in Figure 1B. Briefly, extracts are reconstituted in either organic solvent or water and transferred to cotton rolls contained within an empty SPE cartridge using a liquid handling robot, followed by freeze-drying to remove solvents. Next, extracts (n = 88) are prefractionated using 2 g of C8 SPE cartridges on a single automated positive pressure SPE workstation (ppSPE) to produce seven fractions per extract, which are collected in preweighed 2D-barcoded tubes. Finally, fractions are dried using high-performance centrifugal evaporation systems, and the final mass is determined with an automated weighing station. To adapt the prefractionation methodology to the automated ppSPE platform, the mass of each organic extract prefractionated was increased from 0.2 to 0.25 g to increase the percentage of fractions at or above the 5 mg threshold. To validate the automated prefractionation process, a set of 44 organic solvent extracts were prefractionated in duplicate using the C8, RP-2.7 method (Supplementary Table S2) and screened against the NCI-60 cell line panel at a single dose (5 μg/mL). As shown in Figure 4A,B, the mass distribution and bioactivity data between the organic extract ppSPE trials are significantly replicated, thus providing proof of the reproducibility of the automated prefractionation methodology.

Figure 4.

Validation of the ppSPE platform for two independent repetitions of the automated prefractionation process. (A) Scatter plots of the fraction mass (n = 88) and corresponding screening results (B) of the prefractionated extracts (n = 88) showed reproducible mass distribution (r = 0.96, p < 0.001) and repeatability in the NCI-60 cell line panel at 5 μg/mL (r = 0.96, p < 0.001) between each ppSPE run, respectively.

Application of the Developed Methodology for Rapid Isolation of Biologically Active Natural Products.

The deconvolution of bioactive components from complex natural product extracts can be a significant bottleneck in the preliminary stages of the drug discovery process.44 However, prefractionated natural product extracts can accelerate the dereplication process by reducing the overall number of compounds to be isolated and identified. As shown in Table 3, the preferred C8, RP-2.7 prefractionation method distributed the components of the crude extracts across each of the fractions with an average number of major analytes detected per fraction ranging from 2 (s = 3) to 17 (s = 21), while the number of minor analytes were between 9 (s = 6) and 28 (s = 27). To demonstrate the potential application of the developed prefractionation methodology to streamline the downstream process of dereplication and isolation of biologically active natural products, several fractions with notable activity profiles, representing a plant, marine, and microbial sourced extract, were selected from the prefractionated sets to develop methods for the rapid isolation (i.e., from 1 to 2 preparative scale steps) and structure elucidation of their active components. For each of these extracts, reversed-phase preparative scale (50–150 mg/separation) chromatographic conditions were developed using preparative HPLC columns (Phenomenex Luna 10 μm C18, 250 × 21.2 mm and Kinetex 5 μm C8, 150 × 21.2 mm) to afford individual compounds of high purity (>90%) and of sufficient quantity for hit validation, dereplication, and potential secondary screens.

Table 3.

Average LCMS Peak Count by Fraction for All of the Extracts Prefractionated in the NPNPD Fraction Library Pilot Study Using the C8, RP-2.7 Method

| Avg peak count per C8 SPE fraction (s) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| ELSDa | 2 (1) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 4 (3) | 7 (3) | 11 (8) | 9 (8) |

| total MSb | 11 (7) | 9 (8) | 12 (8) | 22 (16) | 43 (44) | 40 (34) | 23 (12) |

| majorsc | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 3 (3) | 7 (7) | 17 (21) | 12 (12) | 6 (3) |

| minorsd | 9 (6) | 8 (5) | 9 (6) | 15 (13) | 26 (25) | 28 (27) | 17 (11) |

Total number of analytes detected using an evaporative light scattering detector (ELSD).

Total number of analytes estimated from the LC-HRMS data and defined by m/z value, retention time, and intensity (MS buckets).

Total number of MS buckets within each detectable ELSD retention time window.

Total number of MS buckets that were not detected in the corresponding ELSD chromatogram. Standard deviation (s).

The organic extract of the plant F. virosa was selected for scale-up isolation work based on the observation that, while the organic extract was inactive in the NCI-60 screen, a number of fractions showed potent growth inhibition across most NCI-60 cell lines at 10 μg/mL and, in the C8, RP-2.7 series, cell-line selectivity toward several melanoma cell lines (Figure 2A and Supplementary Tables S5–S9). The major active principle, phyllanthusmin D (1),45 was purified in a single preparative HPLC separation, while a minor active triterpenoid, dichapetalin P (2),46 was isolated in two steps. Although both compounds were found to be cytotoxic at low micromolar concentrations with mean GI50 values of 0.43 μM (1) and 1.74 μM (2), phyllanthusmin D was highly selective and 200-fold more potent against melanoma cell lines at the TGI level (Supplementary Figures S22 and S23).

In the microbial extracts, prefractionation of a Penicillium griseofulvum (strain ID 0G0S1555, NSC number F250369) organic extract using the developed C8 SPE-based method showed the presence of two separable regions of bioactivity when tested against the NCI-60 human tumor cell lines panel (Figure 5A). The PLS scores plot showed a separation of the active fractions (F1–F6) from the inactive fractions (F4 and F7), with F1–F3 grouped closely together, while F5 and F6 were clustered away from one another and the rest of the P. griseofulvum metabolome, suggesting the presence of two major active principles or a single minor active component in both fractions (Figure 5B). Subsequent bioassay-guided isolation from a single preparative HPLC purification step identified the active principle in fractions F1–F3 to be the mycotoxin patulin (3),47 while the small molecule responsible for the activity of fraction F5 and F6 was identified as a prenylated diketopiperazine, mycelianamide (4).48 In the NCI-60 assay, compounds 3 and 4 showed low micromolar cytotoxicity with mean GI50 values of 2.95 and 1.95 μM, respectively (Supplementary Figures S24–S26). Although the NCI-60 dose response pattern of the organic solvent extract was similar to 3 by a COMPARE analysis (GI50 = 0.71, TGI = 0.65), it was not significantly correlated with 4 (COMPARE at GI50 = 0.16, TGI = 0.15). Thus, under the growth conditions employed for P. griseofulvum 0G0S1555, 3 is likely the major active metabolite responsible for the initial activity profile of the organic extract, while 4 is present as a minor active metabolite, demonstrating the potential of the C8 SPE-based method to separate confounding toxicity from other, perhaps more interesting, activities.

Figure 5.

Prefractionation of a fungal extract of Penicllium griseofulvum using the developed C8 SPE-based method. (A) Partial least-squares (PLS) scores plot based on the UPLC–HRMS and NCI-60 bioassay data shows a separation of the bioactive (F1, F2, F3, F5, and F6) and inactive fractions (F4 and F7). (B) Presence–absence analysis of the UPLC–HRMS data for the active principles, patulin (3, m/z 153.02 [M − H]−, Rt = 0.5 min) and mycelianamide (4, m/z 369.23 [M − 2H2O + H]+, RT = 5.5 min) shows that the separation of NCI-60 bioactive fractions is driven by the presence of 3 (F1–F3) and 4 (F5–F6).

An organic extract from the sponge Spongionella sp. was selected for further proof-of-concept studies based on the potent antiproliferative activity observed against the NCI-60 screen (GI50 = 2.88 μg/mL, TGI = 11.75 μg/mL, and LC50 = 61.66 μg/mL, Supplementary Figure S27). Prefractionation using the developed C8, RP-2.7 SPE method and subsequent preparative HPLC separation led to the isolation of the known gracilin-type trisnorditerpenes gracilins H and I (5 and 6)49 as a 3:2 mixture from a single fraction, while a minor analog, gracilin A (7),50 was purified in a successive HPLC step. In the NCI-60 assay, the 3:2 mixture of 5 and 6 exhibited cytotoxicity against the NCI-60 human tumor cell lines panel with a GI50 value of 0.93 μM (Supplementary Figure S28), while 7 had a GI50 value of 1.05 μM (Supplementary Figure S29). Additional purification of the two stereoisomers showed that the two compounds had GI50 values of 0.76 μM and 3.39 μM for gracilin H (5) and I (6), respectively (Supplementary Figures S3 and S31). Collectively, these examples, representing plant, marine, and microbial sourced secondary metabolites, emphasize the value of the prefractionation methodology to efficiently identify multiple active constituents in a natural product extract, as well as concentrate minor, biologically active natural products in an automated fractionation and purification workflow to accelerate the dereplication process.

Chemoinformatic Analysis of NP Compounds Arising from the NPNPD Model Prefractionated Library.

In addition to the compounds isolated on a preparative scale, a range of biologically active natural products, representing various biosynthetic pathways from the plant, fungal, and marine extracts used in this pilot study, were isolated on a high-throughput semipreparative scale (1–5 mg/separation; Onyx Monolithic C18, 100 × 10 mm) with purities greater than 90% (Figure 6). The compounds, their select physicochemical properties, and measured accurate mass values are presented in Supplementary Tables S52–S54. Overall, the isolated compounds ranged in molecular weight from 154.1 to 656.8 Da, with a spread of clogP values ranging from −0.3 to 7.0. A chemoinformatics analysis was conducted using a previously defined set of structural and physiochemical parameters to compare the chemical properties of the isolated compounds to the biologically relevant chemical space occupied by NP-sourced drugs approved between 1981 and 2010.69 As shown in Figure 7, the distribution of the isolated compounds from this study with that of approved natural product-based drugs demonstrates that the prefractionation methodology described here, using the medium retentive characteristics of the selected C8 SPE matrix, can capture drug-like biologically active natural products with a range of different physiochemical properties, comparable to that of natural product-sourced and -inspired drugs currently approved for clinical use.

Figure 6.

Structures of additional bioactive compounds isolated from the NPNPD model fraction library and corresponding validation set using high-throughput semipreparative HPLC methods. Bengamide B (8),51 bengazole A (9),52 trichothecinol A (10),53 trichothecin (11),54 8-deoxytrichothecin (12),55 8-isocyano-11(20)-ene-15-amphilectaformamide (13),56 8,15-diisocyano-11(20)-amphilectene (14),56,57 luffariellolide (15),58 epinuapapuin B (16),59 muqubilin (17),60,61 aaptamine (18),62 demethyloxyaaptamine (19),62 3,5-dibromo-2-(2,4-dibromophenoxy)phenol (20),63 2,3,5-tribromo-6-(2,4-dibromophenoxy)phenol (21),63 hippuristanol (22),64 erythrolide F (23),65 mycgranol (24),66 agelasine D (25),67 and plakinidine A (26).68

Figure 7.

(A) PCA plot showing the distribution of the isolated natural products from the NPNPD prefractionated library methods development set with that of approved natural product-based drugs. The first three principal components (PC1–PC3) contain 77% of the covariance in the set of 20 structural and physiochemical described previously in the analysis of NCEs from 1981–2010.69 As shown in the component loadings plot for the PCA (B), distribution of compounds along the axis of PC1 is largely driven by vectors related to molecular weight (MW), such as the number of heteroatoms (N, O), hydrogen bond donor/acceptors (HBD, HBA), rotatable bonds (RotB), the topological polar surface area (tPSA), and van der Waals surface area (VWSA). Positioning along the axis of PC2 is influenced in the positive direction by the calculated n-octanol/water partition coefficient (ALOGPs) and in the negative direction by the calculated aqueous solubility (ALOGpS) and relative polar surface area (relPSA). PC3 represents molecular complexity with regards to the number of stereocenters (nStereo) and fraction of sp3 carbons (Fsp3). In general, molecules with greater molecular complexity are shown in the positive direction. See Supplementary Tables S52 and S53, for the calculated structural and physiochemical parameters of the NPNPD compounds that were projected onto the model generated by Stratton et al.69

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, the prefractionation methodology developed to generate the NPNPD fraction library resulted a high-throughput, automated SPE platform that was shown to produce partially purified fractions containing an even distribution of metabolites, to concentrate minor, biologically active natural products, and to accommodate a sufficient amount of starting material (0.2–1.0 g) to support screening and subsequent streamlined downstream processes in drug discovery programs. Although improvements in dereplication strategies and recent advances in NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry instrumentation now allow the structure elucidation of complex natural product scaffolds at the microgram level,44,70 a significant challenge that remains in many modern drug discovery programs is access to the chemical diversity of natural products. This is largely due to the desire to screen libraries of pure compounds, which presents challenges regarding compound availability and supply. Of the more than 250,000 natural products reported, only a small fraction are commercially available.71 Furthermore, it is estimated that 90% of the collective biodiversity of marine, microbial and plant species have yet to be investigated in drug discovery campaigns.72 The NCI effort reported here—the production of a large, publicly available prefractionated natural product library—will enhance the chemical diversity accessible for screening and hopefully stimulate the continued success of natural products as biological probes and lead compounds in drug discovery. To this end, the aim of the NPNPD is to expand the availability of high quality, well annotated natural product-based screening libraries derived from the NCI Natural Products Repository through the generation of a HTS-amenable library containing over 1,000,000 fractions from more than 125,000 marine, microbial, and plant extracts that have been collected from biodiverse regions throughout the world. It is anticipated that the first set of 150,000 plated prefractionated extracts will be available for screening by January 2019.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General Experimental Procedures.

NMR spectra were recorded at 25 °C on a 500 MHz Bruker Avance spectrometer, equipped with a triple resonance 5 mm CPTCI cryo-probe. The 1H and 13C NMR chemical shifts were referenced to the solvent peaks for CD3OD at δH 3.30 and δc 49.05. NMR FID processing and data interpretation was done using MestReNova software, version 11.0. UPLC–HRMS data were acquired using a Phenomenex Kinetex C8 [1.7 μm, 50 × 2.1 mm] column on a Waters Acquity UPLC system coupled to a Waters LCT Premier TOF mass spectrometer with an electrospray ionization source. The mass spectrometric data for compounds 1–26 were recorded on an Agilent 6545 Accurate-Mass Q-TOF LC/MS system (1290 Infinity II) equipped with a dual AJS ESI source. Preparative-scale HPLC purification was performed with a Waters Prep LC system, equipped with a Delta 600 pump and a 996-photodiode array detector or an Agilent 1200 series, equipped with a 6130-single quad mass spectrometer, using a Luna C18 [10 μm, 250 × 21.2 mm], Phenomenex Kinetex C8 HPLC column [5 μm, 150 × 21.2 mm], or a Phenomenex Onyx C18 HPLC column [100 × 10 mm]. Semi-preparative-scale HPLC purification was performed with a Gilson HPLC purification system equipped with a GX-281 liquid handler, a 322-binary pump, a 172-photodiode array detector, and a Verity 1900 MS detector. All solvents used for SPE, HPLC, and MS were GC/LC–MS grade, and the H2O for preparative HPLC was Millipore Milli-Q PF filtered.

Extraction and Prefractionation of Natural Product Extracts for NPR Model Library.

Plant, marine, and microbial extracts included in the model prefractionated library methods development, validation and proof-of-principle studies were obtained from the NCI Natural Products Repository and were prepared according to the extraction procedures detailed in McCloud,19 unless otherwise noted. A portion of the organic solvent extracts (200–250 mg) and aqueous extracts (400–1000 mg) were weighed into barcoded tubes and dissolved in 4.5 mL of MeOH/EtOAc/MTBE (6:3:1) or H2O, respectively. Dissolved samples were adsorbed onto cotton rolls (1.27 cm × 3.81 cm, TIDI Products, LLC) contained within an empty SPE cartridge, followed by freeze-drying to remove solvents. Prior to prefractionation, each SPE cartridge was washed with three column volumes of 100% MeOH, followed by equilibration with three column volumes of the first eluent of the respective solvent series employed. For the normal phase prefractionation series, organic solvent extracts were prefractionated on 2 g Isolute diol SPE cartridges (2,3-dihydroxypropoxypropyl, nonend-capped functionalized silica: 50 μm, 60 Å) using four different gradients: NP-1.7 [Hex/CH2Cl2 (9:1), Hex/CH2Cl2 (7:3), CH2Cl2/EtOAc (5:1), 100% EtOAc, EtOAc/MeOH (5:1), MeOH/EtOAc (1:1), and 100% MeOH]; NP-1.10 [100% Hex, Hex/CH2Cl2 (9:1), Hex/CH2Cl2 (7:3), CH2Cl2/EtOAc (5:1), EtOAc/CH2Cl2 (7:3), 100% EtOAc, EtOAc/MeOH (5:1), MeOH/EtOAc (1:1), MeOH/EtOAc (5:1), and 100% MeOH]; NP-2.7 [100% Hex, Hex/EtOAc (5:1), Hex/EtOAc (1:1), EtOAc/Hex (7:3), 100% EtOAc, EtOAc/MeOH (7:3), and 100% MeOH]; and NP-2.10 [100% Hex, Hex/EtOAc (5:1), Hex/EtOAc (3:2), Hex/EtOAc (2:3), EtOAc/Hex (5:1), 100% EtOAc, EtOAc/MeOH (5:1), EtOAc/MeOH (1:1), MeOH/EtOAc (5:1), and 100% MeOH]. For the reversed-phase prefractionation series, the organic solvent extracts were prefractionated on the following 2 g SPE cartridges: Isolute C8 SPE (octyl, nonend-capped: 50 μm, 60 Å); HyperSep C8 (octyl, nonend-capped: 50 μm, 60 Å); Oasis HLB (hydrophilic–lipophilic-balanced divinylbenzene, N-vinylpyrrolidone copolymer; 60 μm); and Isolute C8, Oasis HLB mixed-bed SPE column (1.5 and 0.5 g, respectively). The aqueous extracts were prefractionated on 2 g SPE cartridges that included Bakerbond Wide-Pore C4 (butyl, nonend-capped: 50 μm, 60 Å); Isolute C8 and HyperSep C8; Oasis HLB; Bondesil ENV (hydroxylated polystyrene divinylbenzene copolymer; 125 μm); and Bakerbond Wide-Pore C4, Oasis HLB mixed-bed SPE (1.5 and 0.5 g, respectively). The reversed-phase solvent series for organic solvent extracts included four different gradients: RP-1.7 [ACN/H2O (5:95), ACN/H2O (3:7), ACN/H2O (1:1), ACN/H2O (7:3), ACN/MeOH/H2O (85:5:10), ACN/MeOH (1:1), and ACN/CH2Cl2 (3:7) or ACN/MeOH (1:1) for ppSPE system]; RP-1.10 [100% H2O, ACN/H2O (5:95), ACN/H2O (15:85), ACN/H2O (3:7), ACN/H2O (1:1), ACN/H2O (7:3), ACN/MeOH/H2O (70:20:10), ACN/MeOH/H2O (60:30:10), ACN/MeOH (1:1), and ACN/CH2Cl2 (3:7) or ACN/MeOH (1:1) for ppSPE system]; RP-2.7 [MeOH/H2O (5:95), MeOH/H2O (1:4), MeOH/H2O (2:3), MeOH/H2O (3:2), MeOH/H2O (4:1), 100% MeOH, and MeOH/CH2Cl2 (3:7) or ACN/MeOH (1:1) for ppSPE system]; and RP-2.10 [MeOH/H2O (5:95), MeOH/H2O (15:85), MeOH/H2O (1:3), MeOH/H2O (35:65), MeOH/H2O (1:1), MeOH/H2O (65:35), MeOH/H2O (3:1), MeOH/H2O (85:15), 100% MeOH, and MeOH/CH2Cl2 (3:7) or ACN/MeOH (1:1) for the automated SPE system]. The aqueous extracts were prefractionated with the reversed-phase solvent schemes, with two additional 100% H2O washes (2 × 8 mL) included prior to the collection of the first eluent. For each prefractionation scheme, the cotton-adsorbed, lyophilized SPE sample cartridge was stacked above an adsorbent-containing SPE cartridge using a SPE tube adapter (Supelco, Sigma-Aldrich) for individualized fractionation or equipped with a barbed luer (Nordson Medical) and SPE sealing cap (Gilson Inc.) and placed within a custom 48-postion manifold printed out of polylactic acid using a Series 1 Pro 3D printer (Type A Machines) for automated ppSPE fractionation. Manual prefractionation was performed using a top-loaded syringe, and the automated prefractionation was carried out with a customized positive pressure solid phase extraction (ppSPE) workstation (Tecan Freedom Evo) with two robotic arms working together to process 44 extracts in parallel. A single ppSPE run could accommodate up to 88 natural product extracts and generate 616 fractions in 3.5 h. A controlled rate of elution (<10 mL/min) was maintained for both prefractionation techniques, and the elution solvents (8 mL) were collected in preweighed 10 mL polypropylene 2D-barcoded tubes containing a linear barcoded protective jacket (FluidX, Phenix Research Products) and dried at 20–35 °C using Genevac HT-12 high-performance centrifugal evaporation systems. Following solvent removal (18 h), the mass of each natural product fraction was determined using a BioMicroLab XL200 automated weighing station.

Data Analysis.

To collect UPLC–HRMS data for multivariate analyses, samples were prepared at a final concentration of 500 μg/mL with an internal reference standard of reserpine (2 μg/mL). A 10 μL injection volume of each sample was performed, and samples were profiled using a Phenomenex Kinetex C8 UPLC column [2 μm, 50 × 2.1 mm] at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min and the following conditions: an initial isocratic hold at 100% H2O (0.1% formic acid) for 2 min, followed by a linear gradient to 100% CH3CN (0.1% formic acid) over 20 min, and a final isocratic hold at 100% CH3CN (0.1% formic acid) for 2 min. UPLC–HRMS data evaluation by PCA was performed with R (v. 3.1.2) from the R-project73 and visualized with ggplot2 for R.74 Peak detection, chromatogram building, isotope removal, and final alignment via the Random Sample Consensus (RANSAC) algorithm were performed using Mzmine 275 with the default parameters and a minimum height (baseline) setting of 1 × 104. The spectral data list including retention time, m/z, and intensity for each peak was exported to Excel (Microsoft) for peak filtering and absence–presence analysis. UPLC–HRMS data evaluation by univariate partial least-squares regression (PLS) was performed with R (v. 3.1.2) from the R-project using the plsdepot package.76 Observational scores values were exported for plotting in Excel. Feature selection, through peak detection, chromatogram building, background subtraction, isotope removal, and final RANSAC alignment, was performed using the xcms77–79 and CAMERA80 packages for R. The profile generation method of the peak picking algorithm was set to “binlinbase”, and the matched filter method was used with the full width at half-maximum option set to 60. NCI-60 mean growth percentages were merged with the resultant feature alignment table as the response variable in the PLS analysis. For the chemoinformatic analysis or PCA of the physiochemical parameters of the compounds isolated from the NPNPD pilot study, the descriptors were calculated and projected onto the model of approved natural product drugs from 1981–2010 as described by Stratton et al.69 The PCA and loadings plots were generated using an open-sourced JavaScript graphing library, plotly.js.81

High-Throughput Screening Assays.

The NCI-60 Human Tumor Cell Lines Screen was conducted by the Molecular Pharmacology Branch of the Developmental Therapeutics Program, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD, USA) as previously described.37 The high throughput target-based in vitro assays including MALT1, p38, and TDP1 were conducted by the Molecular Targets Program within the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD, USA) as detailed elsewhere.38,39

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge K. Gustafson, L. Cartner, and R. Fuller from the Molecular Targets Program at NCI-Frederick for their assistance during the development of the prefractionation methodology, as well as B. Wilson, E. Smith, and L. Krumpe for p38, MALT-1, and Tdp-1 data, respectively. We also thank R. Parchment and W. Kopp at Leidos Biomedical Research, Inc. for managerial support and resources.

Funding

This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (NIH), under contract HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. This project has also been supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acschem-bio.8b00389.

Additional figures and tables. Isolation of Phyllanthusmin D (1) and Dichapetalin P (2) from Fluegga virosa. Isolation of Patulin (3) and Mycelianamide (4) from Penicillium sp. 0G0S1555. Isolation of Gracilins H (5), I (6), and A (7) from Spongionella sp. (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Firn RD, and Jones CG (2003) Natural products - a simple model to explain chemical diversity. Nat. Prod. Rep 20, 382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Newman DJ, and Cragg GM (2016) Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs from 1981 to 2014. J. Nat. Prod 79, 629–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Henrich CJ, and Beutler JA (2013) Matching the power of high throughput screening to the chemical diversity of natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep 30, 1284–1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Macarron R, Banks MN, Bojanic D, Burns DJ, Cirovic DA, Garyantes T, Green DV, Hertzberg RP, Janzen WP, Paslay JW, Schopfer U, and Sittampalam GS (2011) Impact of high-throughput screening in biomedical research. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 10, 188–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Harvey AL (2007) Natural products as a screening resource. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 11, 480–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Camp D, Davis RA, Campitelli M, Ebdon J, and Quinn RJ (2012) Drug-like Properties: Guiding Principles for the Design of Natural Product Libraries. J. Nat. Prod 75, 72–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Wetzel S, Bon RS, Kumar K, and Waldmann H (2011) Biology-Oriented Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 50, 10800–10826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Paul SM, Mytelka DS, Dunwiddie CT, Persinger CC, Munos BH, Lindborg SR, and Schacht AL (2010) How to improve R&D productivity: the pharmaceutical industry’s grand challenge. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 9, 203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Hert J, Irwin JJ, Laggner C, Keiser MJ, and Shoichet BK (2009) Quantifying biogenic bias in screening libraries. Nat. Chem. Biol 5, 479–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).National Cancer Institute. NCI Experimental Therapeutics (NExT) program https://next.cancer.gov (accessed 2018).

- (11).Henrich CJ, Cartner LK, Wilson JA, Fuller RW, Rizzo AE, Reilly KM, McMahon JB, and Gustafson KR (2015) Deguelins, Natural Product Modulators of NF1-Defective Astrocytoma Cell Growth Identified by High-Throughput Screening of Partially Purified Natural Product Extracts. J. Nat. Prod 78, 2776–2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Butler MS, Fontaine F, and Cooper MA (2014) Natural Product Libraries: Assembly, Maintenance, and Screening. Planta Med 80, 1161–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Cutignano A, Nuzzo G, Ianora A, Luongo E, Romano G, Gallo C, Sansone C, Aprea S, Mancini F, D’Oro U, and Fontana A (2015) Development and Application of a Novel SPE-Method for Bioassay-Guided Fractionation of Marine Extracts. Mar. Drugs 13, 5736–5749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Månsson M, Phipps RK, Gram L, Munro MHG, Larsen TO, and Nielsen KF (2010) Explorative Solid-Phase Extraction (E-SPE) for Accelerated Microbial Natural Product Discovery, Dereplication, and Purification. J. Nat. Prod 73, 1126–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Harvey AL, Edrada-Ebel R, and Quinn RJ (2015) The re-emergence of natural products for drug discovery in the genomics era. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 14, 111–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).NIH National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Natural Product Libraries. https://nccih.nih.gov/grants/naturalproducts/libraries (accessed 2018).

- (17).Brown EC, and Newman DJ (2006) The US National Cancer Institute’s natural products repository; origins and utility. J. Environ. Monit 8, 800–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Cragg GM, Katz F, Newman DJ, and Rosenthal J (2012) The impact of the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity on natural products research. Nat. Prod. Rep 29, 1407–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).McCloud TG (2010) High Throughput Extraction of Plant, Marine and Fungal Specimens for Preservation of Biologically Active Molecules. Molecules 15, 4526–4563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Thorne N, Auld DS, and Inglese J (2010) Apparent activity in high-throughput screening: origins of compound-dependent assay interference. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 14, 315–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Van Middlesworth F, and Cannell RJP (1998) Dereplication and Partial Identification of Natural Products, In Natural Products Isolation (Cannell RJP, Ed.), pp 279–327, Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Cardellina JH, Munro MHG, Fuller RW, Manfredi KP, McKee TC, Tischler M, Bokesch HR, Gustafson KR, Beutler JA, and Boyd MR (1993) A Chemical Screening Strategy for the Dereplication and Prioritization of HIV-Inhibitory Aqueous Natural Products Extracts. J. Nat. Prod 56, 1123–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Tu Y, Jeffries C, Ruan H, Nelson C, Smithson D, Shelat AA, Brown KM, Li X-C, Hester JP, Smillie T, Khan IA, Walker L, Guy K, and Yan B (2010) Automated High-Throughput System to Fractionate Plant Natural Products for Drug Discovery. J. Nat. Prod 73, 751–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Eldridge GR, Vervoort HC, Lee CM, Cremin PA, Williams CT, Hart SM, Goering MG, O’Neil-Johnson M, and Zeng L (2002) High-Throughput Method for the Production and Analysis of Large Natural Product Libraries for Drug Discovery. Anal. Chem 74, 3963–3971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Scalbert A (1992) Quantitative Methods for the Estimation of Tannins in Plant Tissues, In Plant Polyphenols: Synthesis, Properties, Significance (Hemingway RW, and Laks PE, Eds.), pp 259–280, Springer, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Liao X-P, and Shi B (2005) Selective removal of tannins from medicinal plant extracts using a collagen fiber adsorbent. J. Sci. Food Agric 85, 1285–1291. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Collins RA, Ng TB, Fong WP, Wan CC, and Yeung HW (1998) Removal of Polyphenolic Compounds from Aqueous Plant Extracts Using Polyamide Minicolumns. IUBMB Life 45, 791–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Lamoral-Theys D, Pottier L, Dufrasne F, Neve J, Dubois J, Kornienko A, Kiss R, and Ingrassia L (2010) Natural Polyphenols that Display Anticancer Properties Through Inhibition of Kinase Activity. Curr. Med. Chem 17, 812–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Dai J, and Mumper RJ (2010) Plant Phenolics: Extraction, Analysis and Their Antioxidant and Anticancer Properties. Molecules 15, 7313–7352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Jain SK, Bharate SB, and Vishwakarma RA (2012) Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibition by Flavoalkaloids. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem 12, 632–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Jeffery DW, Mercurio MD, Herderich MJ, Hayasaka Y, and Smith PA (2008) Rapid Isolation of Red Wine Polymeric Polyphenols by Solid-Phase Extraction. J. Agric. Food Chem 56, 2571–2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Pérez-Magariño S, Ortega-Heras M, and Cano-Mozo E (2008) Optimization of a Solid-Phase Extraction Method Using Copolymer Sorbents for Isolation of Phenolic Compounds in Red Wines and Quantification by HPLC. J. Agric. Food Chem 56, 11560–11570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Hawryl M, and Hawryl A (2013) Optimization of the Mobile Phase Composition, In Thin Layer Chromatography in Drug Analysis, pp 41–62, CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Versiani MA, Diyabalanage T, Ratnayake R, Henrich CJ, Bates SE, McMahon JB, and Gustafson KR (2011) Flavonoids from Eight Tropical Plant Species That Inhibit the Multidrug Resistance Transporter ABCG2. J. Nat. Prod 74, 262–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Shoemaker RH (2006) The NCI60 human tumour cell line anticancer drug screen. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 813–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Alley MC, Scudiero DA, Monks A, Hursey ML, Czerwinski MJ, Fine DL, Abbott BJ, Mayo JG, Shoemaker RH, and Boyd MR (1988) Feasibility of Drug Screening with Panels of human Tumor Cell Lines Using a Microculture Tetrazolium Assay. Cancer Res 48, 589–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Boyd MR, and Paull KD (1995) Some Practical Considerations and Applications of the National Cancer Institute In Vitro Anticancer Drug Discovery Screen. Drug Dev. Res 34, 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Wilson BAP, Alam MS, Guszczynski T, Jakob M, Shenoy SR, Mitchell CA, Goncharova EI, Evans JR, Wipf P, Liu G, Ashwell JD, and O’Keefe BR (2015) Discovery and Characterization of a Biologically Active Non–ATP-Competitive p38 MAP Kinase Inhibitor. J. Biomol. Screening 21, 277–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Bermingham A, Price E, Marchand C, Chergui A, Naumova A, Whitson EL, Krumpe LRH, Goncharova EI, Evans JR, McKee TC, Henrich CJ, Pommier Y, and O’Keefe BR (2017) Identification of Natural Products That Inhibit the Catalytic Function of Human Tyrosyl-DNA Phosphodiesterase (TDP1). SLAS Discovery 22, 1093–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Cicco N, Lanorte MT, Paraggio M, Viggiano M, and Lattanzio V (2009) A reproducible, rapid and inexpensive Folin–Ciocalteu micro-method in determining phenolics of plant methanol extracts. Microchem. J 91, 107–110. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Ainsworth EA, and Gillespie KM (2007) Estimation of total phenolic content and other oxidation substrates in plant tissues using Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Nat. Protoc 2, 875–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Want E, and Masson P (2011) Processing and Analysis of GC/LC-MS-based Metabolomics Data, In Metabolic Profiling. Methods in Molecular Biology (Methods and Protocol) (Metz T, Ed.), pp 277–298, Humana Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Wold S, Sjöström M, and Eriksson L (2001) PLS-regression: a basic tool of chemometrics. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst 58, 109–130. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Gaudêncio SP, and Pereira F (2015) Dereplication: racing to speed up the natural products discovery process. Nat. Prod. Rep 32, 779–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Ren Y, Lantvit DD, Deng Y, Kanagasabai R, Gallucci JC, Ninh TN, Chai H-B, Soejarto DD, Fuchs JR, Yalowich JC, Yu J, Swanson SM, and Kinghorn AD (2014) Potent Cytotoxic Arylnaphthalene Lignan Lactones from Phyllanthus poilanei. J. Nat. Prod 77, 1494–1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Long C, Aussagues Y, Molinier N, Marcourt L, Vendier L, Samson A, Poughon V, Chalo Mutiso PB, Ausseil F, Sautel F, Arimondo PB, and Massiot G (2013) Dichapetalins from Dichapetalum species and their cytotoxic properties. Phytochemistry 94, 184–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Birkinshaw JH, Michael SE, Bracken A, and Raistrick H (1943) Patulin in the common cold. Collaborative research on a derivative of Penicillium patulum Bainier. II. Biochemistry and chemistry. Lancet II, 625–630. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Oxford AE, and Raistrick H (1948) Studies in the biochemistry of microorganisms: 76. Mycelianamide, C22H28O5N2, a metabolic product of Penicillium griseofulvum Dierckx. Part 1. Preparation, properties, and breakdown products. Biochem. J 42, 323–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Rueda A, Losada A, Fernandez R, Cabanas C, Garcia-Fernandez LF, Reyes F, and Cuevas C (2006) Gracilins G-I, Cytotoxic Bisnorditerpenes from Spongionella pulchella, and the Anti-Adhesive Properties of Gracilin B. Lett. Drug Des. Discovery 3, 753–760. [Google Scholar]

- (50).Mayol L, Piccialli V, and Sica D (1985) Gracilin A, an unique nor-diterpene metabolite from the marine sponge Spongionella gracilis. Tetrahedron Lett 26, 1357–1360. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Quinoa E, Adamczeski M, Crews P, and Bakus GJ (1986) Bengamides, Heterocyclic Anthelmintics from a Jaspidae Marine Sponge. J. Org. Chem 51, 4494–4497. [Google Scholar]

- (52).Adamczeski M, Quinoa E, and Crews P (1988) Unusual Anthelminthic Oxazoles from a Marine Sponge. J. Am. Chem. Soc 110, 1598–1602. [Google Scholar]

- (53).Loukaci A, Kayser O, Bindseil KU, Siems K, Frevert J, and Abreu PM (2000) New Trichothecenes Isolated from Holarrhena floribunda. J. Nat. Prod 63, 52–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Hanson JR, Marten T, and Siverns M (1974) Studies in Terpenoid Biosynthesis. Part XII. Carbon-13 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectra of the Trichothecanes and the Biosynthesis of Trichothecolone from [2-13C]Mevalonic Acid. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans 1 1, 1033–1036. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Chinworrungsee M, Wiyakrutta S, Sriubolmas N, Chuailua P, and Suksamrarn A (2008) Cytotoxic Activities of Trichothecenes Isolated from an Endophytic Fungus Belonging to Order Hypocreales. Arch. Pharmacal Res 31, 611–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Wratten SJ, Faulkner DJ, Hirotsu K, and Clardy J (1978) Diterpenoid Isocyanides from the Marine Sponge Hymeniacidon amphilecta. Tetrahedron Lett 19, 4345–4348. [Google Scholar]

- (57).Ciavatta ML, Gavagnin M, Manzo E, Puliti R, Mattia CA, Mazzarella L, Cimino G, Simpson JS, and Garson MJ (2005) Structural and stereochemical revision of isocyanide and isothiocyanate amphilectenes from the Caribbean marine sponge Cribochalina sp. Tetrahedron 61, 8049–8053. [Google Scholar]

- (58).Albizati KF, Holman T, Faulkner DJ, Glaser KB, and Jacobs RS (1987) Luffariellolide, an anti-inflammatory sesterterpene from the marine sponge Luffariella sp. Experientia 43, 949–950. [Google Scholar]

- (59).Sperry S, Valeriote FA, Corbett TH, and Crews P (1998) Isolation and Cytotoxic Evaluation of Marine Sponge-Derived Norterpene Peroxides. J. Nat. Prod 61, 241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Kashman Y, and Rotem M (1979) Muqubilin, a New C24-Isoprenoid From a Marine Sponge. Tetrahedron Lett 20, 1707–1708. [Google Scholar]

- (61).Manes LV, Bakus GJ, and Crews P (1984) Bioactive Marine Sponge Norditerpene and Norsesterterpene Peroxides. Tetrahedron Lett 25, 931–934. [Google Scholar]

- (62).Calcul L, Longeon A, Mourabit AA, Guyot M, and Bourguet-Kondracki M-L (2003) Novel alkaloids of the aaptamine class from an Indonesian marine sponge of the genus. Tetrahedron 59, 6539–6544. [Google Scholar]

- (63).Calcul L, Chow R, Oliver AG, Tenney K, White KN, Wood AW, Fiorilla C, and Crews P (2009) NMR Strategy for Unraveling Structures of Bioactive Sponge-Derived Oxy-polyhalogenated Diphenyl Ethers. J. Nat. Prod 72, 443–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Higa T, Tanaka J, Tsukitani Y, and Kikuchi H (1981) Hippuristanols, Cytotoxic Polyoxygenated Steroids from the Gorgonian Isis hippuris. Chem. Lett 10, 1647–1650. [Google Scholar]

- (65).Pordesimo EO, Schmitz FJ, Ciereszko LS, Hossain MB, and Van der Helm D (1991) New Briarein Diterpenes from the Caribbean Gorgonians Erythropodium caribaeorum and Briareum sp. J. Org. Chem 56, 2344–2357. [Google Scholar]

- (66).Rudi A, Benayahu Y, and Kashman Y (2005) Mycgranol, a New Diterpene from the Marine Sponge Mycale aff. graveleyi. J. Nat. Prod 68, 280–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Abdjul DB, Yamazaki H, Kanno S, Takahashi O, Kirikoshi R, Ukai K, and Namikoshi M (2015) Structures and Biological Evaluations of Agelasines Isolated from the Okinawan Marine Sponge Agelas nakamurai. J. Nat. Prod 78, 1428–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).West RR, Mayne CL, Ireland CM, Brinen LS, and Clardy J (1990) Plakinidines: Cytotoxic Alkaloid Pigments from the Fijian Sponge Plakortis sp. Tetrahedron Lett 31, 3271–3274. [Google Scholar]

- (69).Stratton CF, Newman DJ, and Tan DS (2015) Cheminformatic comparison of approved drugs from natural product versus synthetic origins. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 25, 4802–4807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Molinski TF (2010) NMR of natural products at the ‘nanomole-scale’. Nat. Prod. Rep 27, 321–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Chen Y, de Bruyn Kops C, and Kirchmair J (2017) Data Resources for the Computer-Guided Discovery of Bioactive Natural Products. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 57, 2099–2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Harvey A (2000) Strategies for discovering drugs from previously unexplored natural products. Drug Discovery Today 5, 294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).R Core Development Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- (74).Wickham H (2009) ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis, 1st ed., Springer-Verlag, New York. [Google Scholar]

- (75).Pluskal T, Castillo S, Villar-Briones A, and Oresic M (2010) MZmine 2: modular framework for processing, visualizing, and analyzing mass spectrometry-based molecular profile data. BMC Bioinf 11, 395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Sanchez G plsdepot: Partial Lease Squares (PLS) Data Analysis Methods. R package version 0.1.17, 2012.

- (77).Smith CA, Want EJ, O’Maille G, Abagyan R, and Siuzdak G (2006) XCMS: Processing Mass Spectrometry Data for Metabolite Profiling Using Nonlinear Peak Alignment, Matching, and Identification. Anal. Chem 78, 779–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Tautenhahn R, Böttcher C, and Neumann S (2008) Highly sensitive feature detection for high resolution LC/MS. BMC Bioinf 9, 504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Benton HP, Want EJ, and Ebbels TM (2010) Correction of mass calibration gaps in liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry metabolomics data. Bioinformatics 26, 2488–2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Kuhl C, Tautenhahn R, Bottcher C, Larson TR, and Neumann S (2012) CAMERA: An Integrated Strategy for Compound Spectra Extraction and Annotation of Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry Data Sets. Anal. Chem 84, 283–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Johnson AC, Tétreault-Pinard E, Lysenko M, Reusser R, Monfera R, Riesco N, Tusz M, Douglas C, Postlethwaite B, Parmer C, and Vados A plotly.js: The open source JavaScript graphing library that powers Plotly; Plotly, Inc., 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.