Abstract

Background

Bacterial folliculitis and boils are globally prevalent bacterial infections involving inflammation of the hair follicle and the perifollicular tissue. Some folliculitis may resolve spontaneously, but others may progress to boils without treatment. Boils, also known as furuncles, involve adjacent tissue and may progress to cellulitis or lymphadenitis. A systematic review of the best evidence on the available treatments was needed.

Objectives

To assess the effects of interventions (such as topical antibiotics, topical antiseptic agents, systemic antibiotics, phototherapy, and incision and drainage) for people with bacterial folliculitis and boils.

Search methods

We searched the following databases up to June 2020: the Cochrane Skin Specialised Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and Embase. We also searched five trials registers up to June 2020. We checked the reference lists of included studies and relevant reviews for further relevant trials.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that assessed systemic antibiotics; topical antibiotics; topical antiseptics, such as topical benzoyl peroxide; phototherapy; and surgical interventions in participants with bacterial folliculitis or boils. Eligible comparators were active intervention, placebo, or no treatment.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane. Our primary outcomes were 'clinical cure' and 'severe adverse events leading to withdrawal of treatment'; secondary outcomes were 'quality of life', 'recurrence of folliculitis or boil following completion of treatment', and 'minor adverse events not leading to withdrawal of treatment'. We used GRADE to assess the certainty of the evidence.

Main results

We included 18 RCTs (1300 participants). The studies included more males (332) than females (221), although not all studies reported these data. Seventeen trials were conducted in hospitals, and one was conducted in clinics. The participants included both children and adults (0 to 99 years). The studies did not describe severity in detail; of the 232 participants with folliculitis, 36% were chronic. At least 61% of participants had furuncles or boils, of which at least 47% were incised. Duration of oral and topical treatments ranged from 3 days to 6 weeks, with duration of follow‐up ranging from 3 days to 6 months. The study sites included Asia, Europe, and America. Only three trials reported funding, with two funded by industry.

Ten studies were at high risk of 'performance bias', five at high risk of 'reporting bias', and three at high risk of 'detection bias'.

We did not identify any RCTs comparing topical antibiotics against topical antiseptics, topical antibiotics against systemic antibiotics, or phototherapy against sham light. Eleven trials compared different oral antibiotics.

We are uncertain as to whether cefadroxil compared to flucloxacillin (17/21 versus 18/20, risk ratio (RR) 0.90, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.70 to 1.16; 41 participants; 1 study; 10 days of treatment) or azithromycin compared to cefaclor (8/15 versus 10/16, RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.40; 31 participants; 2 studies; 7 days of treatment) differed in clinical cure (both very low‐certainty evidence). There may be little to no difference in clinical cure rate between cefdinir and cefalexin after 17 to 24 days (25/32 versus 32/42, RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.38; 74 participants; 1 study; low‐certainty evidence), and there probably is little to no difference in clinical cure rate between cefditoren pivoxil and cefaclor after 7 days (24/46 versus 21/47, RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.78; 93 participants; 1 study; moderate‐certainty evidence).

For risk of severe adverse events leading to treatment withdrawal, there may be little to no difference between cefdinir versus cefalexin after 17 to 24 days (1/191 versus 1/200, RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.07 to 16.62; 391 participants; 1 study; low‐certainty evidence). There may be an increased risk with cefadroxil compared with flucloxacillin after 10 days (6/327 versus 2/324, RR 2.97, 95% CI 0.60 to 14.62; 651 participants; 1 study; low‐certainty evidence) and cefditoren pivoxil compared with cefaclor after 7 days (2/77 versus 0/73, RR 4.74, 95% CI 0.23 to 97.17; 150 participants; 1 study; low‐certainty evidence). However, for these three comparisons the 95% CI is very wide and includes the possibility of both increased and reduced risk of events. We are uncertain whether azithromycin affects the risk of severe adverse events leading to withdrawal of treatment compared to cefaclor (274 participants; 2 studies; very low‐certainty evidence) as no events occurred in either group after seven days.

For risk of minor adverse events, there is probably little to no difference between the following comparisons: cefadroxil versus flucloxacillin after 10 days (91/327 versus 116/324, RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.98; 651 participants; 1 study; moderate‐certainty evidence) or cefditoren pivoxil versus cefaclor after 7 days (8/77 versus 5/73, RR 1.52, 95% CI 0.52 to 4.42; 150 participants; 1 study; moderate‐certainty evidence). We are uncertain of the effect of azithromycin versus cefaclor after seven days due to very low‐certainty evidence (7/148 versus 4/126, RR 1.26, 95% CI 0.38 to 4.17; 274 participants; 2 studies). The study comparing cefdinir versus cefalexin did not report data for total minor adverse events, but both groups experienced diarrhoea, nausea, and vaginal mycosis during 17 to 24 days of treatment. Additional adverse events reported in the other included studies were vomiting, rashes, and gastrointestinal symptoms such as stomach ache, with some events leading to study withdrawal.

Three included studies assessed recurrence following completion of treatment, none of which evaluated our key comparisons, and no studies assessed quality of life.

Authors' conclusions

We found no RCTs regarding the efficacy and safety of topical antibiotics versus antiseptics, topical versus systemic antibiotics, or phototherapy versus sham light for treating bacterial folliculitis or boils. Comparative trials have not identified important differences in efficacy or safety outcomes between different oral antibiotics for treating bacterial folliculitis or boils.

Most of the included studies assessed participants with skin and soft tissue infection which included many disease types, whilst others focused specifically on folliculitis or boils. Antibiotic sensitivity data for causative organisms were often not reported. Future trials should incorporate culture and sensitivity information and consider comparing topical antibiotic with antiseptic, and topical versus systemic antibiotics or phototherapy.

Plain language summary

What are the benefits and risks of different treatments for bacterial folliculitis and boils (inflammation of the skin around hairs)?

Why is this question important?

Bacterial folliculitis is an inflammation of the tiny pockets in our skin from which hairs grow (hair follicles). It occurs when bacteria (tiny organisms not visible with the naked eye) infect hair follicles. Bacterial folliculitis typically causes red swelling, with or without a small blister that contains pus.

Without treatment, bacterial folliculitis may progress to hard and painful lumps filled with pus, known as boils. These cover several hair follicles, and affect the skin around them.

Bacterial folliculitis and boils affect people worldwide, and have an important negative impact on quality of life. Infections typically:

‐ cause unsightly infections on parts of the body visible to others (such as the face and neck); or

‐ develop where skin rubs, causing discomfort and pain (such as armpits and buttocks).

A range of treatment options for bacterial folliculitis and boils is available. These include:

‐ antibiotics (medicines that fight bacterial infections). These can be applied to part of the body (locally) in the form of creams (topical antibiotics); or they can be taken by mouth (orally) or given as injections, to treat the whole body (systemic antibiotics);

‐ antiseptics (chemicals applied to the skin to fight infections caused by micro‐organisms, such as bacteria);

‐ light therapy; and

‐ surgery, for example, doctors may make a small cut (incision) in the skin to allow pus to drain out.

To find out which treatments work best for bacterial folliculitis and boils, we reviewed the evidence from research studies.

How did we identify and evaluate the evidence?

First, we searched for randomised controlled studies, in which people were randomly put into one of two or more treatment groups. This makes it less likely that any differences between treatments were actually due to differences in the people who received them (rather than the treatments themselves, which is what we wanted to find out).

We then compared the results, and summarised the evidence from all the studies. Finally, we rated our confidence in the evidence, based on factors such as study methods and sizes, and the consistency of findings across studies.

What did we find?

We found 18 studies that involved a total of 1300 people. People were followed‐up for between one week and three months. Studies were set in Asia, Europe and America. Only three studies reported information about funding: non‐profit organisations funded one study, and pharmaceutical companies funded two studies.

The studies compared:

‐ different oral antibiotics (11 studies);

‐ different topical antibiotics (2 studies);

‐ different treatments for wound care after boil incision (2 studies);

‐ different traditional Chinese medicines (1 study);

‐ co‐trimoxazole (antibiotics) with, and without, 8‐methoxypsoralen (a light‐sensitising treatment) followed by exposure to sunlight (1 study); and

‐ penicillin (an antibiotic) with, and without, fire cupping (a form of traditional Chinese medicine) after surgery (1 study).

We found no studies that evaluated antiseptics or investigated quality of life or recurrence of bacterial folliculitis or boils.

Here we report the findings from four comparisons of different oral antibiotics.

Cure

The evidence from studies that investigated how successfully different oral antibiotics cured bacterial folliculitis and boils suggests that:

‐ there is probably little to no difference between cefditoren pivoxil and cefaclor (1 study, 93 people);

‐ there may be little to no difference between cefdinir and cephalexin (1 study, 74 people).

The few studies available did not provide sufficiently robust information to determine if:

‐ cefadroxil is better or worse than flucloxacillin (1 study, 41 people); or

‐ azithromycin is better or worse than cefaclor (2 studies, 31 people).

Severe adverse events (such as fever or vomiting)

The evidence from studies that compared frequencies of severe adverse events suggests there may be little to no difference between:

‐ cefadroxil and flucloxacillin (1 study, 651 people);

‐ cefdinir and cephalexin (1 study, 391 people); and

‐ cefditoren pivoxil and cefaclor (1 study, 150 people).

We do not know if azithromycin is associated with more, or fewer, severe adverse events than cefaclor. This is because studies provided insufficiently robust information (2 studies, 274 people).

Minor adverse events (such as feeling thirsty or dizzy)

The evidence from studies that compared frequencies of minor adverse events suggests there is probably little to no difference between:

‐ cefadroxil and flucloxacillin (1 study, 651 people); and

‐ cefditoren pivoxil and cefaclor (1 study, 150 people).

We do not know whether there are more, or fewer, minor adverse events associated with:

‐ cefdinir or cephalexin (1 study, 391 people); or

‐ azithromycin or cefaclor (2 studies, 274 people).

This is because studies reported insufficiently robust information.

What does this mean?

The limited evidence available does not suggest that any one oral antibiotic is better than another for treating bacterial folliculitis and boils.

The comparative benefits and risks of other treatments such as antiseptics or light therapy are unclear, because too few studies have investigated this.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

The evidence in this Cochrane Review is current to June 2020.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

See Table 8 for explanations of specific terms used in this review.

1. Glossary.

| Clinical term | Explanation |

| Anterior nares | External portion of the nostrils, which opens anteriorly into the nasal cavity and allows air inhalation and exhalation |

| Antipseudomonal | Agents used as drugs to destroy bacteria of the genus Pseudomonas |

| Axilla (pl. axillae) | Also known as the armpit, underarm, or oxter; the area directly under the joint where the human arm connects to the shoulder |

| Cellulitis | Term commonly used to indicate non‐necrotising inflammation of the skin and subcutaneous tissues, a process usually related to acute infection that does not involve the fascia or muscles |

| Endogenous chromophobes | A chemical group (such as an azo group) that absorbs light at a specific frequency and so imparts colour to a molecule that originates from within an organism, tissue, or cell |

| Epidermis | One or more layers of cells forming the outermost portion of the skin or integument |

| Fluctuant | Being movable or compressible; often used to describe a tumour or abscess |

| Gram‐negative bacteria | Bacteria that contain an additional outer membrane composed of phospholipids and lipopolysaccharides that do not retain the crystal violet dye in the Gram stain protocol |

| Immunomodulatory | Substance that affects the functioning of the immune system |

| Keratolytic | Causing the horny outer layer of skin to soften and shed |

| Lymphadenitis | Associated with the lymph nodes, which are responsible for fighting off infections of the body; refers to the condition by which lymph nodes become inflamed, swell, and become tender during an infection |

| Monochromatic | Existing in only one colour or particular wavelength |

| Perifollicular tissue | Tissue surrounding a hair follicle; usually used to describe the histopathological appearance of the infiltrate surrounding a hair follicle |

| Pathogen | Any small organism, such as a virus or a bacterium, that can cause disease |

| Pseudomonal | Of or related to the Pseudomonas species, which is a ubiquitous strictly aerobic gram‐negative bacterium with a predilection to moist environments and is a clinically significant opportunistic pathogen, often causing nosocomial infections |

| Purulent | Full of pus or like pus |

| Superficial dermis | Middle layer of skin, deep to the epidermis and superficial to the subcutaneous layer |

| Dieda Xiaoyan Gao | A traditional Chinese medicine ointment with anti‐inflammatory effects |

| STSG | Split‐thickness skin graft, refers to a graft that contains the epidermis and a portion of the dermis |

| ASAT | Aspartate amino transferase, a blood test that checks for liver damage |

| ASLT | Alanine amino transferase, a blood test that checks for liver damage |

| SSTI | Skin and soft tissue infections, bacterial infections of the skin, muscles, and connective tissue such as ligaments and tendons |

| USSSI | Uncomplicated skin and skin structure infections, simple abscesses, impetiginous lesions, furuncles, and cellulitis |

Folliculitis is inflammation of the hair follicle caused by infection, chemical stimulation, or physical injury (Pasternack 2015). The aetiology of folliculitis is diverse, including occlusion folliculitis resulting from blockages caused by exposure to topical products that block the opening of the hair follicle, leading to inflammation, and Malassezia folliculitis, which is caused by Malassezia furfur (also known as Pityrosporum ovale) and presents as itching red papules over the chest, shoulders, or back (Gunatheesan 2018). In this review we were interested in bacterial folliculitis, a bacterial infection within the hair follicle that typically presents as a red swelling with or without a pustule over the follicular opening (Craft 2012). Without treatment, bacterial folliculitis may resolve in 7 to 10 days or may progress to boils.

A boil, also known as a furuncle, is a bacterial infection involving the perifollicular tissue that usually originates from pre‐existing folliculitis (Lopez 2006). A boil appears as a painful red swelling around the follicular opening and may progress to form an abscess (Craft 2012). Some boils may be treated with moist heat application; others with surrounding cellulitis or fever may require treatment with systemic antibiotics (Pasternack 2015). Systemic antibiotics should be continued until the lesion resolves (Pasternack 2015). Carbuncles are large painful swellings with multiple pus‐discharging openings and constitutional symptoms including fever and malaise (Craft 2012). They affect the deeper layers of soft tissue and can lead to scarring. Without control, boils may occasionally be complicated by severe skin infections such as cellulitis or lymphadenitis combined with constitutional symptoms such as fever, fatigue, and chills.

Bacterial folliculitis and boils are prone to occur in areas of the skin subject to rubbing, occlusion, and sweating, such as the neck, face, axillae, and buttocks (Craft 2012). Clinicians usually diagnose bacterial folliculitis and boils based on physical examination findings (Craft 2012).

Bacterial folliculitis and boils are bacterial infections with a worldwide prevalence, but their exact prevalence and incidence are unclear. One study reported a prevalence of around 1.3% in schoolchildren (Al‐Saeed 2006). Another study found that 27% of immunosuppressed organ transplant recipients presented with persistent folliculitis (Lally 2011). In 2010, at least 280,000 boil episodes were reported, and hospital admissions for abscesses, carbuncles, boils, and cellulitis almost doubled in the UK ‐ from 123 admissions per 100,000 in 1998/1999 to 236 admissions per 100,000 in 2010/2011 (Shallcross 2015). This rise might have occurred because staphylococcal strains have become more severe or difficult to treat and may cause recurrent infection, as seen with the increased virulence of community‐onset methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) produced by toxins such as Panton‐Valentine leukocidin (PVL) (Dufour 2002).

S aureus is the most common pathogen of folliculitis and boils. However, gram‐negative pathogens including Klebsiella, Enterobacter, and Proteus species may replace the gram‐positive flora on facial skin, nasal mucous membranes, and neighbouring areas, causing gram‐negative folliculitis and boils (Böni 2003). 'Hot tub' folliculitis is caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa contamination of undertreated water in saunas or whirlpools (Zacherle 1982).

Certain people are affected by recurrent furunculosis (i.e. boils that have a propensity to recur and may spread amongst family members) (Ibler 2014). Recurrent boils are a bothersome disorder that may affect patients' quality of life (Ibler 2014). Colonisation of S aureus in the anterior nares plays an important role in the origin of chronic or recurrent furunculosis (Ibler 2014).

Description of the intervention

Various interventions have been suggested for treating folliculitis (Craft 2012; O'Dell 1998), including local application of moist heat, phototherapy, antiseptic agents, antibiotics alone, or combination therapy. Treatment of fluctuating boils often requires drainage of the lesion, and for severe infections systemic antibiotics should be given until signs of inflammation have regressed.

Local moist heat around 38 °C to 40 °C applied for 15 to 20 minutes may increase local blood flow, may establish drainage, and has proved helpful in the treatment of newly emerged folliculitis or boils (Pasternack 2015). No adverse effects of local moist heat are known (Petrofsky 2009).

Topical antibiotics may be used in treating folliculitis and boils when the number of lesions is limited, or they may be used in combination with other interventions, for example incision and drainage (Laureano 2014). Available preparations include fusidic acid 2% cream twice daily (Frosini 2017; Koning 2002), clindamycin 2% gel twice daily, and mupirocin 2% ointment applied two to three times daily (Micromedex 2018). These drugs are topically applied over the lesion. Topical antibiotics may cause contact dermatitis, dryness, or pruritus over the applied area. However, these adverse events are usually minor (Tran 2017). No major drug‐drug interactions between these topical antibiotics and other medications are known (Micromedex 2018).

Topical antiseptic agents may be manufactured as gel (such as benzoyl peroxide 2% to 10% twice daily), cream, soap, or solution (e.g. hypochlorite 3% to 5% solution) (Micromedex 2018). These antiseptics may be used alone or in combination with antibiotics for treating folliculitis and boils, especially in recurrent furunculosis (Davido 2013). The adverse events of benzoyl peroxide are usually mild and mainly include skin irritation over the application site (Kawashima 2017). No drug interactions of topical antiseptics are known (Micromedex 2018).

Some Chinese herbal compounds may be used in folliculitis and boils treatment, for example Dieda Xiaoyan Gao ointment containing baizaoxiu, danshen, huangyaopian, zhizi, dahuang, baizhi, shengbanxia, shengnanxing, narukawa, caowu, and camphor, have been given to boils patients (Xu 1992).

Systemic antibiotics may be used for treating folliculitis and boils, especially when systemic symptoms such as fever, lymphadenitis, or cellulitis appear (Pereira 1996). Regimens and common drug‐drug interactions of systemic antibiotics are listed in Table 9. First‐line oral antibiotics including dicloxacillin (250 mg four times daily) and cephalosporins (such as cefadroxil 500 mg twice daily) are commonly used. For antibiotic‐resistant S aureus that has emerged in the community, clindamycin, tetracyclines, trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole, linezolid, or glycopeptide (e.g. parenteral vancomycin) may be used (Laureano 2014; Nagaraju 2004). Oral or parenteral ciprofloxacin 400 to 500 mg twice daily with antipseudomonal activity may be administered for gram‐negative folliculitis such as 'hot tub' folliculitis (Craft 2012). Potential adverse events of systemic antibiotics include allergic reactions, neurological or psychiatric disturbances, and diarrhoea (Shehab 2008). Systemic antibiotics may be used in combination with topical antiseptics for treating folliculitis and boils (Pasternack 2015). For some cases of folliculitis, especially those caused by S aureus, a course of oral antibiotics may be administered over 7 to 10 days (Laureano 2014).

2. Regimens and drug‐drug interactions of systemic antibiotics.

| Drug | Dose/regimen | Drug‐drug interaction (Gilbert 2018;Micromedex 2018) |

| Cefadroxil |

|

|

| Ciprofloxacin |

|

|

| Clindamycin |

|

|

| Tetracyclines |

|

|

| Trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole |

|

|

| Linezolid |

|

|

| Glycopeptide (as vancomycin) | Adult: 30 mg/kg/d IV in 2 divided doses or 40 mg/kg/d IV in 4 divided doses |

|

Al: aluminium; Ca: calcium; CNS: central nervous system; Fe: iron; IM: intramuscular; IV: intravenous; Mg: magnesium; NSAIDs: non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs; Zn: zinc.

Surgical interventions, such as incision and drainage, are likely to be adequate for simple fluctuant folliculitis or boils (Ibler 2014). Incision may cause scarring at the incised site (Ahmad 2017). Combined topical or systemic antibiotics is often employed, especially when there is a lack of response to incision and drainage alone, or when the lesion is in an area where complete drainage is difficult (e.g. face, hands, genitalia) (Ibler 2014).

Phototherapy by monochromatic excimer light (308 nm) with 0.5 to 2 minimal erythema dose (MED) has been used as treatment for superficial folliculitis. Nisticò 2009 reported only mild adverse events such as local erythema.

How the intervention might work

As mentioned above, bacterial folliculitis and boils occur as inflammation of the follicle and perifollicular tissue caused by bacterial infection. Antibacterial, antiseptic, and anti‐inflammatory interventions may therefore be used for treatment.

Topical antibiotics such as clindamycin, aminoglycosides, and fusidic acid directly kill or inhibit pathogenic bacteria within the follicle, avoiding further tissue damage by these pathogens (Frosini 2017).

The therapeutic effects of antiseptic agents are attributed to the killing of bacteria that cause folliculitis and boils, such as S aureus (Fisher 2008). Benzoyl peroxide is an antiseptic that confers not only antibacterial effects but also keratolytic effects, which cause the skin to dry and peel (Kawashima 2017).

Systemic antibiotics can directly inhibit or kill the pathogenic bacteria causing folliculitis and boils. When bacterial cultures are available, systemic antibiotics may be administered according to the pathogen identified (Ibler 2014).

Some medications such as Dieda Xiaoyan Gao ointment have anti‐inflammatory effects and may be helpful in the treatment of folliculitis or boils. Pentoxifylline, a methylxanthine derivative with diverse pharmacological properties, may have a synergic effect in anti‐inflammation by inhibiting tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF‐α) when combined with ciprofloxacin (Wahba‐Yahav 1992).

Ultraviolet‐B radiation, which primarily affects the epidermis and the superficial dermis, is absorbed by endogenous chromophobes, such as nuclear DNA, which initiates a cascade of immunomodulatory effects (Bulat 2011). Phototherapy has been proposed as a treatment option for folliculitis for its anti‐inflammatory effects (Nisticò 2009).

Given that pus, or even an abscess, may be present with fluctuant folliculitis and boils, incision and drainage may be used to remove toxic purulent material, decompress the tissues, and support better blood perfusion, which increases drug concentration in an affected area and improves local immune response and tissue repair (Ibler 2014).

Why it is important to do this review

Cochrane Skin undertook an extensive prioritisation exercise to identify a core portfolio of the most clinically important titles. Interventions for bacterial folliculitis and boils was identified as a clinically important priority by a panel of international editors. As aforementioned, folliculitis and boils are worldwide prevalent diseases that cause a great burden on the quality of life of individuals, with an estimated 1,944,776 DALYs (disability‐adjusted life years) worldwide in 2016 (range 1,249,848 to 2,603,083) (Global Burden of Disease).

To the best of our knowledge, no systematic reviews to date have examined interventions for folliculitis and boils. Our goal with this systematic review was to find and evaluate the best available evidence on the effects of interventions for folliculitis and boils.

Objectives

To assess the effects of interventions, such as topical antibiotics, topical antiseptic agents, systemic antibiotics, phototherapy, and incision and drainage, for people with bacterial folliculitis and boils.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including parallel, cluster, cross‐over, and split‐body within‐participant RCTs.

Types of participants

People with bacterial folliculitis or boils diagnosed by a healthcare professional or a trained researcher based on clinical presentation or bacterial culture. We excluded participants with non‐bacterial folliculitis, such as Pityrosporum folliculitis and mite folliculitis. We included RCTs conducted in any setting and placed no restrictions on demographic factors such as age and sex.

When a study included participants with various superficial bacterial infections of the skin, we included the study only if the authors reported separate data for those with bacterial folliculitis or boils. When the publication did not provide separate data, we contacted study authors and requested separate data for bacterial folliculitis and boils.

Types of interventions

Interventions included systemic antibiotics, topical antibiotics, topical antiseptics such as topical benzoyl peroxide, phototherapy, and surgical interventions (e.g. incision and drainage). Participants received a single intervention or a combination of interventions.

Comparators included another active intervention, placebo, or no treatment.

Types of outcome measures

We considered outcome data measured at ≤ 1 month and > 1 month as short‐ and long‐term outcomes, respectively. If a trial reported data at multiple time points within the short‐ or long‐term timeframe, we chose the longest time point.

Primary outcomes

Clinical cure: clearance of all visible lesions of folliculitis or boils (i.e. disappearance of all papular or pustular lesions of folliculitis or boils at the end of treatment).

Severe adverse events leading to withdrawal of treatment.

Secondary outcomes

Quality of life: as measured by validated tools, including Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), 36‐item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐36), Skindex 29, Skindex 17, or Dermatology Quality of Life Scale (DQOLS). We considered a DLQI score change of at least 5 as a minimally important difference (Khilji 2002).

Recurrence of folliculitis or boil following completion of treatment.

Minor adverse events not leading to withdrawal of treatment.

Search methods for identification of studies

We aimed to identify all relevant RCTs regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, or in progress).

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Skin Information Specialist searched the following databases up to 11 June 2020 using strategies based on the draft strategy for MEDLINE in our published protocol (Lin 2018):

the Cochrane Skin Specialised Register using the search strategy in Appendix 1;

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) 2020, Issue 6, in the Cochrane Library, using the strategy in Appendix 2;

MEDLINE via Ovid (from 1946) using the strategy in Appendix 3; and

Embase via Ovid (from 1974) using the strategy in Appendix 4.

Trials registers

Two review authors (HL and YT) searched the following trials registers up to 18 June 2020 using the terms 'boil/s', 'furuncle/s', 'furunculosis', 'folliculitis', 'carbuncle', 'sycosis', and 'sycoses':

ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com);

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov);

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (www.anzctr.org.au);

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch/); and

EU Clinical Trials Register (www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu).

Searching other resources

Searching reference lists

We checked the bibliographies of included studies and related systematic reviews for further references to relevant trials.

Unpublished literature

We contacted the authors of reports of relevant RCTs published within the last three years to ask if they were aware of any relevant unpublished data.

Adverse effects

We did not perform a separate search for adverse effects of interventions used for the treatment of folliculitis and boils. We only considered adverse events described in the included RCTs.

Data collection and analysis

Some parts of this section use text that was originally published in another Cochrane protocol or in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Chi 2015; Higgins 2011).

Selection of studies

Two review authors (HL and PL) independently checked the titles and abstracts derived from the searches. Review authors were not blinded to the names of trialists or their institutions. If it was judged from the title and abstract that a study did not relate to an RCT on interventions for treating folliculitis and boils, it was excluded straight away. The same two review authors independently examined the full text of each remaining study and judged whether it met the inclusion criteria of the review. In case of disagreement between review authors on whether or not to include a study, unanimity was achieved through discussion with a third review author (CC). Studies excluded at full‐text review and the reasons for their exclusion are provided in the Characteristics of excluded studies tables. Covidence was used for selection of studies (Covidence).

Data extraction and management

Using a pilot‐tested data extraction form, two review authors (HL and PL) independently extracted the following data from the included RCTs: study methods, participants, interventions, outcomes, country, setting, and funding source (see Appendix 5). We used WebPlotDigitizer to extract data from figures and graphs (WebPlotDigitizer 2017). We used these extracted data to create the Characteristics of included studies tables. In case of disagreement regarding the extracted data, the two review authors consulted with a third review author (CC) to achieve unanimity. One review author (PL) entered the data into Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014), and another review author (HL) checked the entered data.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used Cochrane's tool for assessing risk of bias in RCTs, evaluating the following 'Risk of bias' domains (Higgins 2017).

Random sequence generation (selection bias): adequacy of the method of random sequence generation to produce comparable groups in every aspect except for the intervention.

Allocation concealment (selection bias): adequacy of the method used to conceal the allocation sequence to prevent anyone from foreseeing the allocation sequence in advance of, or during, enrolment.

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias): adequacy of blinding participants and investigators from knowledge of which intervention a participant received.

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias): adequacy of blinding outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received.

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias): completeness of outcome data for each main outcome, including attrition and exclusions from analysis, whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers in each intervention group (compared with total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusions when reported, and any re‐inclusions in our analyses.

Selective reporting (reporting bias): when the trial protocol was available, we determined whether all prespecified outcomes were reported. When the study protocol was unavailable, we identified whether published reports included all expected outcomes, including those that were prespecified.

Other bias: any important concerns about bias not addressed in the other domains, e.g. design‐specific risk of bias and baseline imbalance.

Two review authors (HL and PL) independently assessed the risk of bias of included RCTs; a third review author (CC) was consulted in case of disagreement.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

We expressed dichotomous data as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). When the RR was statistically significant, we also presented the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) and the number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) with 95% CIs (Higgins 2011).

Continuous data

We expressed continuous data as mean differences (MDs) with 95% CIs. When different outcome scales were pooled, we would expressed continuous data as standardised mean differences (SMDs) with 95% CIs (Higgins 2011).

Time‐to‐event data

We planned to express time‐to‐event data as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs. We would extract HRs as presented in the included study report. When HRs were not reported, we would use the methods described in Tierney 2007 to estimate the HRs if sufficient data were provided.

Unit of analysis issues

We planned to separately analyse studies with the following designs using appropriate techniques as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011); however, none of the included studies adopted these designs.

Cluster‐randomised trials

For cluster‐randomised trials that did not adjust for clusters in their analysis, we would employ the Rao methods described in Section 16.3.4 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011; Rao 1992), and planned to estimate the intervention effect assuming an intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.05.

Cross‐over trials

For cross‐over trials, we would only include data from the first period for analysis. When these data were not available, we would employ the statistical methods described in Section 16.4.6 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), undertaking paired analyses by imputing missing standard deviations.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

For studies with multiple intervention groups, we would make separate pairwise comparisons of one intervention versus another. For example, if an RCT included three interventions groups ‐ Group A (placebo or the most frequently used intervention), Group B, and Group C ‐ we would make separate pairwise comparisons of B versus A and C versus A.

Split‐body trials

For split‐body trials, we would conduct paired analyses using data from one side of the body versus the other side of the body. We would analyse continuous and dichotomous data by using the paired t‐test and McNemar's test, respectively.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the authors of studies less than 10 years old to ask for missing data. Where data were unavailable, we conducted an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis to recalculate the intervention effect estimates, included all randomised participants in the analysis, and assumed that those with missing dichotomous outcome data experienced treatment failure. If the ITT data were unavailable, we carefully evaluated other important numerical data for randomised participants as well as per‐protocol population (PP) and as‐treated (AT) and described this in the 'Risk of bias' assessment. For missing continuous outcome data, we planned to attempt to adopt the 'last observation carried forward' (LOCF) approach in analysis when the trials provided relevant original data, that is replacing a missing value with the participant's last observed value. We would furthermore conduct a sensitivity analysis by assuming that those participants with missing dichotomous outcome data experienced treatment success.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We calculated the I2 statistic to assess statistical heterogeneity across the included trials. The importance of the observed value of the I2 statistic depends on (1) the magnitude and direction of effects, and (2) the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P value from Chi2 test, CI for I2 statistic) (Higgins 2011). We considered an I2 of ≥ 50% as representing at least moderate heterogeneity, and planned to follow the guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions by exploring subgroups to explain the heterogeneity.

We also assessed statistical heterogeneity via forest plot inspection, as in some analyses a high I2 might not be a serious issue, especially if the estimates were all on the same side of the forest plot. We would examine whether statistical heterogeneity suggested a dose‐response relationship or the presence of minimum therapeutic dose by conducting a subgroup analysis based on different dosages of the intervention.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned that when at least 10 trials were included in a meta‐analysis on primary outcomes for an intervention, we would use a funnel plot to assess publication bias (Higgins 2011).

Data synthesis

We provided a narrative description of all outcomes when data were available. For trials that were sufficiently similar in terms of participants, interventions, and outcomes, we performed a random‐effects model meta‐analysis to obtain a pooled intervention effect. When a meta‐analysis was not feasible, we summarised the data narratively instead.

When results were estimated for individual studies with low numbers of outcomes (fewer than 10 in total), or when the total sample size was less than 30 participants and an RR was used, we would report the proportion of outcomes in each group together with a P value based on Fisher's exact test.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to conduct the following subgroup analyses when relevant data were available.

Paediatric versus adult participants (further divided into bacterial culture‐proven or clinical diagnosis only).

Immunocompetent versus immunosuppressed participants (further divided into bacterial culture‐proven or clinical diagnosis).

Methicillin‐sensitive S aureus (MSSA) versus MRSA (including PVL gene type).

Different dosages of an intervention.

To test for subgroup differences, we would employ random‐effects model meta‐analysis and use the methods developed by Borenstein 2008, which have been implemented in Review Manager 5 software (Review Manager 2014).

Sensitivity analysis

We would conduct a sensitivity analysis to examine intervention effects after excluding trials with high risk of bias for one or more domains for a given outcome. We would also conduct a sensitivity analysis assuming that those with missing dichotomous outcome data experienced treatment success.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We have presented 'Summary of findings' tables in order to summarise data on our primary outcomes (clinical cure and severe adverse events leading to withdrawal of treatment) and secondary outcomes (quality of life, recurrence, and minor adverse events not leading to withdrawal of treatment) for the most important comparisons: topical antibiotics versus topical antiseptics, topical antibiotics versus systemic antibiotics, and phototherapy versus sham light (see Types of outcome measures). When several major comparisons were reported, or when outcomes needed to be summarised for different populations, we produced additional 'Summary of findings' tables.

Two review authors (HL and PL) assessed the quality of the body of evidence using the five GRADE considerations: study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias (Schünemann 2013). We downgraded the certainty of the evidence from high to moderate, low, or very low based on these five considerations. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third review author (CC). We used GRADEpro GDT, GRADEpro GDT, to prepare the 'Summary of findings' tables and to assess the certainty of the evidence (Atkins 2004; Schunemann 2011).

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; and Characteristics of ongoing studies.

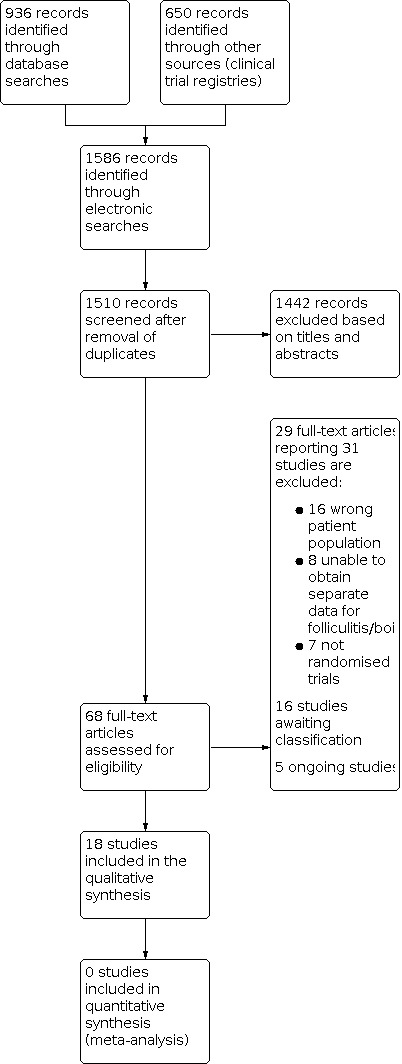

Results of the search

The searches undertaken by the Cochrane Skin Information Specialist of the four databases retrieved 936 records (see Electronic searches). Our searches of the trials registers identified 650 further records. Our screening of the reference lists of the included studies and related systematic reviews did not reveal any additional RCTs. This resulted in a total of 1586 records. After removal of duplicates, we had 1510 records.

We excluded 1442 records based on scanning of titles and abstracts and obtained the full texts of the remaining 68 records. We excluded 31 studies reported in 29 papers (Narayanan 2014a includes three trials) (see Characteristics of excluded studies). We assessed 16 studies as awaiting classification and five studies as ongoing (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification and Characteristics of ongoing studies).

We included 18 studies in the review (see Characteristics of included studies). For a further description of our screening process, see the study flow diagram (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included 18 trials with a total of 1300 participants, covering 30 treatments. Details of the included studies are described in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Design

All 18 included studies were two‐arm parallel RCTs assessing the effects of interventions for bacterial folliculitis and boils.

Sample size

The number of participants in the included studies ranged from 7 to 260. Three included trials had a small sample size of less than 30 participants (Arata 1995a; Montero 1996; Tassler 1993).

Setting

Seventeen trials were conducted at hospitals, whilst the remaining trial was conducted in clinics (Baig 1988). Twelve trials were multicentre (Arata 1988; Arata 1993; Arata 1994a; Arata 1994b; Arata 1995a; Arata 1997; Baig 1988; Beitner 1996; Giordano 2006; Jin 1995; Montero 1996; Tassler 1993), and six trials were conducted at single centres (Iyer 2013; Kessler 2012; Parsad 1997; Shenoy 1990; Xu 1992; Xu 1999). The included trials were conducted in a total of 18 countries (Japan, Sweden, the UK, China, Colombia, Guatemala, Panama, South Africa, India, Germany, Argentina, Austria, Brazil, Belgium, Finland, France, Italy, and the USA).

Participants

The included studies involved at least 232 folliculitis patients (including 83 with chronic folliculitis) and at least 795 participants with furuncles or boils (at least 376 of them received incision). However, most studies did not report the duration of disease, and only one trial mentioned that the duration was more than four weeks (Parsad 1997).

In many of the included trials, participants with folliculitis and boils were only a subgroup without detailed age information, and we could not calculate the interquartile range (IQR) in these participants. The studies that provided the sex of their participants enrolled a total of 332 males and 221 females, with an age range from 0 to 99 years old.

Two trials did not report the age of participants (Shenoy 1990; Xu 1992). One trial enrolled only children (between 6 months to 12 years) (Montero 1996). Three trials included adults aged 18 years or older (Iyer 2013; Parsad 1997; Tassler 1993), and five trials included participants aged 16 years or older (Arata 1993; Arata 1994a; Arata 1994b; Arata 1995a; Arata 1997). Two trials included participants aged at least 10 years, Baig 1988, or 13 years old (Giordano 2006). Five trials included both paediatric and adult participants: aged 0 to over 70 years (Arata 1988), 1 to 25 years (Kessler 2012), 3 to 81 years (Beitner 1996), 3 to 65 years (Xu 1999), and 6 to 65 years (Jin 1995).

Interventions

The included studies assessed six topical treatments, 16 oral treatments, and eight other treatments, as either interventions or comparators.

Topical treatments

Ofloxacin (Jin 1995)

Norfloxacin (Jin 1995)

Sisomicin (Arata 1988)

Gentamicin (Arata 1988)

Dieda Xiaoyan Gao ointment (Xu 1992)

Ichthammol ointment (Xu 1992)

Oral treatments

Cefaclor (Arata 1993; Arata 1994a; Arata 1994b; Arata 1995a; Montero 1996)

Flucloxacillin (Baig 1988; Beitner 1996)

Cefadroxil (Beitner 1996)

Cefdinir (Giordano 2006)

Cefalexin (Giordano 2006)

Cefditoren pivoxil (Arata 1993)

Fleroxacin (Tassler 1993)

Amoxicillin/clavulanate (Tassler 1993)

Erythromycin (Baig 1988)

Azithromycin (Arata 1995a; Montero 1996)

Grepafloxacin (Arata 1997)

Ofloxacin (Arata 1997)

Ciprofloxacin (Parsad 1997)

Pentoxifylline plus ciprofloxacin (Parsad 1997)

S‐1108 (Arata 1994a)

SY 5555 (Arata 1994b)

Other treatments

Co‐trimoxazole plus 8‐methoxypsoralen and sunlight (Shenoy 1990)

Co‐trimoxazole plus placebo and sunlight (Shenoy 1990)

Fire cupping plus penicillin intramuscular injection (Xu 1999)

Incision for pus plus penicillin intramuscular injection (Xu 1999)

Wound packing following incision and drainage (Kessler 2012)

Incision and drainage without wound packing (Kessler 2012)

Excision of carbuncle with primary split thickness skin grafting (STSG) (Iyer 2013)

Excision of carbuncle with delayed STSG (Iyer 2013)

The 14 trials that compared oral or topical treatments reported a treatment duration of between three days and six weeks (Arata 1988; Arata 1993; Arata 1994a; Arata 1994b; Arata 1995a; Arata 1997; Baig 1988; Beitner 1996; Giordano 2006; Jin 1995; Montero 1996; Parsad 1997; Tassler 1993; Xu 1992). Iyer 2013 measured outcomes seven days postoperatively; similarly, Xu 1999 measured clinical cure seven days after the cupping procedure. Kessler 2012 assessed failure 48 hours after the procedures, and healing at 1 week and 1 month afterwards. Shenoy 1990 measured outcomes 15, 45, and 90 days after the procedure. To monitor the relapse of the lesions, the Parsad 1997 trial followed up the participants for 6 months.

There were five trials with co‐interventions, including excision with primary or delayed STSG (Iyer 2013); incision and drainage with or without wound packing (Kessler 2012); oral ciprofloxacin with or without oral pentoxifylline (Parsad 1997); oral co‐trimoxazole with or without oral 8‐methoxypsoralen followed by sunlight exposure (Shenoy 1990); and penicillin intramuscular injection combined with lesion incision with or without fire cupping (Xu 1999).

Comparators

Most trials compared the efficacy between different medications for folliculitis or boils: three compared different topical drugs (Arata 1988; Jin 1995; Xu 1992), and 11 compared different oral drugs (Arata 1993; Arata 1994a; Arata 1994b; Arata 1995a; Arata 1997; Baig 1988; Beitner 1996; Giordano 2006; Montero 1996; Parsad 1997; Tassler 1993). Iyer 2013 assessed primary versus delayed STSG after boils incision and drainage. Kessler 2012 analysed the efficacy of wound packing after boils incision. Xu 1999 analysed the efficacy of fire cupping after boils incision and drainage. Shenoy 1990 assessed co‐trimoxazole (an antibiotic) with and without 8‐methoxypsoralen followed by exposure to sunlight.

Outcomes

Fifteen trials measured our primary outcome of clinical cure; 12 trials severe adverse events or safety; 13 studies minor adverse events or safety; and three trials recorded recurrence (Kessler 2012; Parsad 1997; Shenoy 1990). Although no trials assessed quality of life, one trial assessed wound healing and pain (Kessler 2012). With regard to safety, data were not always reported per diagnosis. The follow‐up duration in these trials ranged from three days to six months from start of treatment.

Funding sources

Of the 18 included trials, two were industry supported (Beitner 1996; Giordano 2006), and one was supported by nonprofit organisations (such as government or academic institutions) (Kessler 2012). The remaining 15 trials did not report funding sources.

Excluded studies

We excluded 31 articles because they did not report respective data for bacterial folliculitis and boils; were not a randomised trial; or were a prevention study. The reasons for exclusion are listed in Characteristics of excluded studies.

Studies awaiting classification

A total of 16 trials are awaiting classification. For five trials, only the study title was available, and we were only able to obtain the abstracts of the other 11 trials rather than full texts. Of the 11 trials, one trial included participants with chronic folliculitis (Balachandran 1995); one trial included participants with superficial pyoderma (Bernard 1997); six trials included participants with skin and soft tissue infections (Bilen 1998; Carr 1994; Chen 2011; Fujita 1982; Macedo De Souza 1995; Welsh 1987); and three trials included participants with folliculitis, furunculosis, and pyodermitis (cellulitis, erysipelas) (Lobo 1995; NCT01032499; Pereira 1996).

As for the interventions assessed, nine trials compared different oral antibiotics (Bernard 1997; Bilen 1998; Carr 1994; Chen 2011; Fujita 1982; Lobo 1995; Macedo De Souza 1995; NCT01032499; Pereira 1996); one trial compared oral antibiotics with placebo (Balachandran 1995); and one trial compared oral antibiotics with topical antibiotics (Welsh 1987).

Details of these studies are provided in Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Ongoing studies

Five clinical trials have not yet been completed, including two in Clinical Trials Registry‐India (CTRI/2015/01/005361; CTRI/2018/03/012411); two in the EU Clinical Trials Register (EUCTR 2008‐006151‐42; EUCTR 2016‐005105‐39); and one in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01281930). Three of these studies include participants with uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infections (CTRI/2015/01/005361; CTRI/2018/03/012411; EUCTR 2008‐006151‐42); one trial includes participants with folliculitis (EUCTR 2016‐005105‐39); and the remaining trial includes participants with boils (NCT01281930).

Two trials compare different oral antibiotics in adolescents and adults (CTRI/2015/01/005361; EUCTR 2008‐006151‐42). One trial compares different topical antibiotics (CTRI/2018/03/012411), and another compares antibiotics and antiseptic medications (EUCTR 2016‐005105‐39). One trial compares different wound packing after furunculosis incision and drainage in children (NCT01281930).

The protocols of the trials are listed in Characteristics of ongoing studies.

We attempted to contact the authors of the studies awaiting classification and ongoing studies if email addresses were provided (see Appendix 6).

Risk of bias in included studies

Our judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item presented as percentages across all of the included trials are shown in Figure 2, and we summarise our judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item for each included trial in Figure 3. Further details regarding risk of bias are provided in the 'Risk of bias' tables in the Characteristics of included studies section.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Two trials used an adequate method of generation of the randomisation sequence (Giordano 2006; Kessler 2012). The remaining 16 trials did not describe the process of randomisation and were thus rated as unclear risk of bias.

Allocation was concealed in six trials (Arata 1988; Arata 1993; Arata 1994a; Arata 1994b; Arata 1995a; Arata 1997), whilst it was unclear if allocation was concealed in the other 12 trials.

Blinding

We rated eight trials as at low risk of performance bias because both the investigators and participants were blinded (Arata 1988; Arata 1993; Arata 1994a; Arata 1994b; Arata 1995a; Arata 1997; Parsad 1997; Shenoy 1990). We judged 10 RCTs as at high risk of performance bias because the participants were not blinded (Baig 1988; Beitner 1996; Giordano 2006; Iyer 2013; Jin 1995; Kessler 2012; Montero 1996; Tassler 1993; Xu 1992; Xu 1999).

In five trials, the blinded physicians assessed the outcomes (Arata 1993; Arata 1994a; Arata 1995a; Arata 1997; Shenoy 1990). Also, we judged the Giordano 2006 and Kessler 2012 trials as at low risk of detection bias because a third person was assigned to assess clinical response. We rated three open‐label trials as at high risk of detection bias because unblinded physicians assessed outcomes (Baig 1988; Montero 1996; Tassler 1993).

We considered the other eight trials as having an unclear risk of detection bias because it was not reported whether the outcome assessors were blinded (Arata 1988; Arata 1994b; Beitner 1996; Iyer 2013; Jin 1995; Parsad 1997; Xu 1992; Xu 1999).

Incomplete outcome data

The risk of attrition bias was low in six trials because of a low or null dropout rate (Baig 1988; Giordano 2006; Iyer 2013; Jin 1995; Kessler 2012; Xu 1992). The risk of attrition bias was high in one trial due to a high dropout rate (Shenoy 1990). We rated 10 trials as at unclear risk of attrition bias because ITT data were unavailable, and the outcome efficacy analysis was based on the PP data (Arata 1988; Arata 1993; Arata 1994a; Arata 1994b; Arata 1995a; Arata 1997; Beitner 1996; Montero 1996; Parsad 1997; Tassler 1993). No dropouts or withdrawals were mentioned in the Xu 1999 trial.

Selective reporting

Thirteen trials reported both the prespecified primary efficacy and adverse outcomes and were judged to be at a low risk of reporting bias (Arata 1988; Arata 1993; Arata 1994a; Arata 1994b; Arata 1995a; Arata 1997; Baig 1988; Beitner 1996; Giordano 2006; Jin 1995; Montero 1996; Parsad 1997; Tassler 1993). The other five trials did not report the adverse events and were considered to be at a high risk of reporting bias (Iyer 2013; Kessler 2012; Shenoy 1990; Xu 1992; Xu 1999).

Other potential sources of bias

The risk of other sources of bias was unclear in all studies because there was insufficient information to assess whether another important risk of bias existed.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7

Summary of findings 1. Topical antibiotics compared to topical antiseptics for bacterial folliculitis and boils (furuncles and carbuncles).

| Topical antibiotics compared to topical antiseptics for bacterial folliculitis and boils (furuncles and carbuncles) | |||||

| Patient or population: bacterial folliculitis and boils (furuncles and carbuncles) Setting: no trials were identified Intervention: topical antibiotics Comparison: topical antiseptics | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with topical antiseptics | Risk with topical antibiotics | ||||

| Clinical cure | No trials were identified. | ||||

| Severe adverse events leading to withdrawal of treatment | No trials were identified. | ||||

| Quality of life | No trials were identified. | ||||

| Recurrence of folliculitis or boil following completion of treatment | No trials were identified. | ||||

| Minor adverse events not leading to withdrawal of treatment | No trials were identified. | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

Summary of findings 2. Topical antibiotics compared to systemic antibiotics for bacterial folliculitis and boils (furuncles and carbuncles).

| Topical antibiotics compared to systemic antibiotics for bacterial folliculitis and boils (furuncles and carbuncles) | |||||

| Patient or population: bacterial folliculitis and boils (furuncles and carbuncles) Setting: no trials were identified Intervention: topical antibiotics Comparison: systemic antibiotics | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with systemic antibiotics | Risk with topical antibiotics | ||||

| Clinical cure | No trials were identified. | ||||

| Severe adverse events leading to withdrawal of treatment | No trials were identified. | ||||

| Quality of life | No trials were identified. | ||||

| Recurrence of folliculitis or boil following completion of treatment | No trials were identified. | ||||

| Minor adverse events not leading to withdrawal of treatment | No trials were identified. | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

Summary of findings 3. Phototherapy compared to sham light for bacterial folliculitis and boils (furuncles and carbuncles).

| Phototherapy compared to sham light for bacterial folliculitis and boils (furuncles and carbuncles) | |||||

| Patient or population: bacterial folliculitis and boils (furuncles and carbuncles) Setting: no trials were identified Intervention: phototherapy Comparison: sham light | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with sham light | Risk with phototherapy | ||||

| Clinical cure | No trials were identified. | ||||

| Severe adverse events leading to withdrawal of treatment | No trials were identified. | ||||

| Quality of life | No trials were identified. | ||||

| Recurrence of folliculitis or boil following completion of treatment | No trials were identified. | ||||

| Minor adverse events not leading to withdrawal of treatment | No trials were identified. | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

Summary of findings 4. Cefadroxil compared to flucloxacillin for bacterial furunculosis.

| Cefadroxil compared to flucloxacillin for bacterial furunculosis | |||||

| Patient or population: bacterial furunculosis Setting: clinics Intervention: cefadroxil Comparison: flucloxacillin | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with flucloxacillin | Risk with cefadroxil | ||||

| Clinical cure (measured after 10 days of treatment) |

Study population | RR 0.90 (0.70 to 1.16) | 41 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 | |

| 900 per 1000 | 810 per 1000 (630 to 1000) | ||||

| Severe adverse events leading to withdrawal of treatment (reported during 10 days of treatment) |

Study population | RR 2.97 (0.60 to 14.62) | 6514 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 | |

| 6 per 1000 | 18 per 1000 (4 to 90) | ||||

| Quality of life | Not measured | ||||

| Recurrence of folliculitis or boil following completion of treatment | Not measured | ||||

| Minor adverse events not leading to withdrawal of treatment (reported during 10 days of treatment) |

Study population | RR 0.78 (0.62 to 0.98) | 6514 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE3 | |

| 358 per 1000 | 279 per 1000 (222 to 351) | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1Downgraded one level due to high risk of performance bias and two levels for serious imprecision (not meeting optimal information size (total number of participants n = 70; 35 in each group), and the confidence interval included 1.0). 2Downgraded one level due to high risk of performance bias and one level for imprecision (the confidence of intervals included 1.0). 3Downgraded one level due to high risk of performance bias. 4The complete study participants were included in adverse event analysis.

Summary of findings 5. Cefdinir compared to cefalexin for bacterial folliculitis and boils (furuncles and carbuncles).

| Cefdinir compared to cefalexin for bacterial folliculitis and boils (furuncles and carbuncles) | |||||

| Patient or population: bacterial folliculitis and boils (furuncles and carbuncles) Setting: hospital Intervention: cefdinir Comparison: cefalexin | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with cefalexin | Risk with cefdinir | ||||

| Clinical cure (measured 17 to 24 days after treatment) |

Study population | RR 1.00 (0.73 to 1.38) | 74 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | |

| 760 per 1000 | 770 per 1000 (670 to 876) | ||||

| Severe adverse events leading to withdrawal of treatment (reported during 17 to 24 days of treatment) |

Study population | RR 1.05 (0.07 to 16.62) | 3912 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | |

| 5 per 1000 | 5 per 1000 (0 to 83) | ||||

| Quality of life | Not measured | ||||

| Recurrence of folliculitis or boil following completion of treatment | Not measured | ||||

| Minor adverse events not leading to withdrawal of treatment | Not reported. But the authors do state that of the 391 participants who received study medications, 10% in the cefdinir group and 4% in the cefalexin group experienced diarrhoea (P = 0.017), 3% and 6% nausea, respectively (P = 0.203), and 3% and 6% of females experienced vaginal mycosis (P = 0.500) during therapy. | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1Downgraded one level due to high risk of performance bias and one level for imprecision (confidence interval included 1.0). 2The complete study participants were included in adverse event analysis.

Summary of findings 6. Azithromycin compared to cefaclor for bacterial boils (furuncles and carbuncles).

| Azithromycin compared to cefaclor for bacterial boils (furuncles and carbuncles) | |||||

| Patient or population: bacterial boils (furuncles and carbuncles) Setting: hospitals and clinics (multicentre) Intervention: azithromycin Comparison: cefaclor | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with cefaclor | Risk with azithromycin | ||||

| Clinical cure (measured 7 days after treatment) |

Study population | RR 1.01 (0.72 to 1.40) | 31 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 | |

| 625 per 1000 | 631 per 1000 (450 to 875) | ||||

| Severe adverse events leading to withdrawal of treatment (reported during 7 days of treatment) |

No severe adverse events leading to withdrawal of treatment occurred in either the azithromycin or cefaclor group. | ‐ | 2744 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 2 | |

| Quality of life | Not measured | ||||

| Recurrence of folliculitis or boil following completion of treatment | Not measured | ||||

| Minor adverse events not leading to withdrawal of treatment (reported during 7 days of treatment) |

Study population | RR 1.26 (0.38 to 4.17) | 2744 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 3 | |

| 40 per 1000 | 51 per 1000 (15 to 166) | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1Downgraded two levels due to high risk of performance bias and detection bias, and one level due to imprecision (not meeting optimal information size of 70, with 35 in each group). 2Downgraded two levels due to high risk of performance bias and detection bias, and one level due to imprecision (few events). 3Downgraded two levels due to high risk of performance bias and detection bias, and one level due to imprecision (the confidence interval included 1). 4The complete study participants were included in adverse event analysis.

Summary of findings 7. Cefditoren pivoxil compared to cefaclor for bacterial boils (furuncles and carbuncles).

| Cefditoren pivoxil compared to cefaclor for bacterial boils (furuncles and carbuncles) | |||||

| Patient or population: bacterial boils (furuncles and carbuncles) Setting: hospitals and clinics (multicentre) Intervention: cefditoren pivoxil Comparison: cefaclor | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with cefaclor | Risk with cefditoren pivoxil | ||||

| Clinical cure (measured after 7 days of treatment) |

Study population | RR 1.17 (0.77 to 1.78) | 93 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE1 | |

| 447 per 1000 | 523 per 1000 (344 to 795) | ||||

| Severe adverse events leading to withdrawal of treatment (reported during 7 days of treatment) |

No participants taking cefaclor withdrew from treatment due to severe adverse events, whilst 2 participants in the cefditoren pivoxil group withdrew due to adverse events (nausea and heavy feeling in stomach). | RR 4.74 (0.23 to 97.17) | 1504 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW2 | |

| Quality of life | Not measured | ||||

| Recurrence of folliculitis or boil following completion of treatment | Not measured | ||||

| Minor adverse events not leading to withdrawal of treatment (reported during 7 days of treatment) |

Study population | RR 1.52 (0.52 to 4.42) | 1504 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE3 | |

| 68 per 1000 | 104 per 1000 (36 to 303) | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1Downgraded one level due to imprecision (just one modest‐size trial). 2Downgraded two levels due to serious imprecision (few events and the confidence of intervals included 1.0). 3Downgraded one level due to imprecision (the confidence of intervals included 1.0). 4The complete study participants were included in adverse event analysis.

No trials compared topical antibiotics versus topical antiseptics (Table 1), topical antibiotics versus systemic antibiotics (Table 2), or phototherapy versus sham light for bacterial folliculitis and boils (Table 3).

We could not undertake the following planned subgroup analyses due to the low number of studies included: paediatric versus adult participants, immunocompetent versus immunosuppressed participants, MSSA versus MRSA (including PVL gene type), and different dosages of an intervention.

Most comparisons included only one RCT, therefore we were unable to perform meta‐analyses for these comparisons.

Topical interventions

Ofloxacin gel versus norfloxacin cream

One RCT compared the efficacy of 0.5% ofloxacin gel with 1.0% norfloxacin gel applied over the lesions twice daily (Jin 1995).

Primary outcome 1. Clinical cure: clearance of all visible lesions of folliculitis or boils (i.e. disappearance of all papular or pustular lesions of folliculitis or boils at the end of treatment)

The ofloxacin and ofloxacin groups did not differ in cure (risk ratio (RR) 1.00, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.94 to 1.07; participants = 60; studies = 1, see Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Ofloxacin gel versus norfloxacin gel, Outcome 1: Clinical cure

Primary outcome 2. Severe adverse events leading to withdrawal of treatment

No serious adverse events occurred in either group.

Secondary outcome 1. Quality of life: as measured by validated tools, including Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), 36‐item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐36), Skindex 29, Skindex 17, or Dermatology Quality of Life Scale (DQOLS)

Quality of life data were not reported.

Secondary outcome 2. Recurrence of folliculitis or boil following completion of treatment

Recurrence data were not reported.

Secondary outcome 3. Minor adverse events not leading to withdrawal of treatment

No adverse events occurred in either group.

Sisomicin ointment versus gentamicin ointment

One study compared the clinical response between sisomicin 1% ointment and gentamicin 1% ointment applied over folliculitis lesions two to three times daily for seven days (Arata 1988).

Primary outcome 1. Clinical cure: clearance of all visible lesions of folliculitis or boils (i.e. disappearance of all papular or pustular lesions of folliculitis or boils at the end of treatment)

The trial detected no difference in clinical cure between the two study groups (RR 1.20, 95% CI 0.55 to 2.63, P = 0.24; participants = 38; studies = 1, see Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Sisomicin ointment versus gentamicin ointment, Outcome 1: Clinical cure

Primary outcome 2. Severe adverse events leading to withdrawal of treatment

No serious adverse events occurred in either group.

Secondary outcome 1. Quality of life: as measured by validated tools, including DLQI, SF‐36, Skindex 29, Skindex 17, or DQOLS

Quality of life data were not reported.

Secondary outcome 2. Recurrence of folliculitis or boil following completion of treatment

Recurrence data were not reported.

Secondary outcome 3. Minor adverse events not leading to withdrawal of treatment

The safety analysis enrolled 151 participants (75 in the sisomicin group and 76 in the gentamicin group). One participant that received gentamicin had adverse event (irritable sensation) (RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.01 to 8.16, P = 0.50; participants = 151; studies = 1, see Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.