Abstract

How an organism copes with chemicals is largely determined by the genes and proteins that collectively function to defend against, detoxify and eliminate chemical stressors. This integrative network includes receptors and transcription factors, biotransformation enzymes, transporters, antioxidants, and metal- and heat-responsive genes, and is collectively known as the chemical defensome. Teleost fish is the largest group of vertebrate species and can provide valuable insights into the evolution and functional diversity of defensome genes. We have previously shown that the xenosensing pregnane x receptor (pxr, nr1i2) is lost in many teleost species, including Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) and three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus), but it is not known if compensatory mechanisms or signaling pathways have evolved in its absence. In this study, we compared the genes comprising the chemical defensome of five fish species that span the teleosteii evolutionary branch often used as model species in toxicological studies and environmental monitoring programs: zebrafish (Danio rerio), medaka (Oryzias latipes), Atlantic killifish (Fundulus heteroclitus), Atlantic cod, and three-spined stickleback. Genome mining revealed evolved differences in the number and composition of defensome genes that can have implication for how these species sense and respond to environmental pollutants, but we did not observe any candidates of compensatory mechanisms or pathways in cod and stickleback in the absence of pxr. The results indicate that knowledge regarding the diversity and function of the defensome will be important for toxicological testing and risk assessment studies.

Subject terms: Cellular signalling networks, Data mining, Gene regulatory networks, Genome informatics, Functional genomics, Genetic variation, Comparative genomics, Genome evolution

Introduction

The aquatic environment is a sink for anthropogenic compounds, and aquatic animals are particularly vulnerable to chemical stressors in their natural habitats. Many of these chemicals may profoundly influence organism health, including viability, growth, performance, and reproductive abilities. Aquatic species are also widely used as model organisms to assess responses to environmental pollutants. In the OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, 13 tests for toxic properties of chemicals use fish in general, and often specific fish species such as zebrafish, medaka, Atlantic killifish and three-spined stickleback.

The intrinsic defense against toxic chemicals largely depends on a set of genes and proteins collectively known as the chemical defensome1. The term “chemical defensome” refers to a wide range of transcription factors, enzymes, transporters, and antioxidant enzymes that together function to detoxify and eliminate harmful compounds, including xenobiotic and endobiotic chemicals. Thus, the composition of genes comprising a species’ chemical defensome will affect the species overall responsiveness and sensitivity towards chemicals stressors. While we believe that all major protein families that contribute to these defenses are included, it is possible that some individual genes (proteins) have been missed. Genomic-scale information is readily gathered, but less readily analyzed to a great depth. The recent years of sequencing efforts have produced high quality genome assemblies from a wide range of species, facilitating genome-wide mapping and annotation of genes. The chemical defensome was first described in the invertebrates sea urchin and sea anemone1,2, and was later mapped in zebrafish (Danio rerio), coral, arthropods, and partly in tunicates3–6. Although these reports show that the overall metabolic pathways involved in the chemical defensome are largely evolutionarily conserved, the detailed comparison of defensome gene composition in different teleost fish species is not studied.

The diversity in both presence and number of gene homologs can vary substantially between fish species due to the two whole genome duplication (WGD) events in early vertebrate evolution7 and a third fish-specific WGD event8, in addition to other evolutionary mechanisms such as gene loss, inversions and neo- and subfunctionalizations. For example, we have previously shown that several losses of the pregnane x receptor (pxr, or nr1i2) have occurred independently across teleost evolution9. PXR is an important xenosensor and as a ligand-activated transcription factor one of the key regulators of the chemical defensome10,11. The importance of PXR in response to chemical stressors in vertebrates, raises questions of how some fish species cope without this gene.

Thus, the objective of this study was to compare the chemical defensome of zebrafish (Danio rerio), medaka (Oryzias latipes), and Atlantic killifish (Fundulus heteroclitus), which are species that have retained a pxr gene, to Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) and three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus), that have lost this gene by independent mechanisms. Genomes of zebrafish, medaka, killifish, and stickleback were chosen based on their widespread use as model species in both developmental and toxicological studies12–15. Atlantic cod is an ecologically and economically important species in the North Atlantic Ocean, and has commonly been used as a bioindicator species in environmental monitoring programs16–18. The genome of Atlantic cod was first published in 201119, which has facilitated its increased use as model in toxicological studies20–24. Although these fish are all benthopelagic species, their natural habitats range from freshwater to marine environments, from tropical to temperate conditions, and reach sizes ranging from less than five cm (zebrafish and medaka) and 15 cm (killifish and stickleback) to 200 cm (Atlantic cod).

Our results include an overview of the full complement of putative chemical defensome genes in these five fish species. Furthermore, by using previously published transcriptomics data, we investigated the transcriptional expression of defensome genes in early development of zebrafish and stickleback, and their responses to the model polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminant, benzo(a)pyrene.

In conclusion, our study represents the first interspecies comparison of the full complement of chemical defensome genes in teleost model species. We found that although most defensome genes have been retained in the teleost genomes over millions of years, there are distinct differences between the species. Based on our results, we suggest a holistic approach to analyze omics datasets from toxicogenomic studies, where differences in the chemical defensome gene complement are taken into consideration.

Material and methods

Sequence resources

The mapping of chemical defensome genes were performed in the most recently published fish genomes available in public databases (Supplementary Table 1, available at FAIRDOMHub: 10.15490/fairdomhub.1.document.925.3). For zebrafish (Danio rerio, GRCz11), three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculatus, BROAD S1), Atlantic killifish (Fundulus heteroclitus, Fundulus_heteroclitus-3.0.2), and Japanese medaka HdrR (Oryzias latipes, ASM223467v1), we used the genome assemblies and annotations available in ENSEMBL. For Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua), we used the recent gadMor3 genome assembly available in NCBI (GCA_902167405). For all five species, we focused on the protein coding genes and transcripts.

Identification of chemical defensome genes

The list of genes included in the chemical defensome (available at FAIRDOMHub: https://doi.org/10.15490/fairdomhub.1.datafile.3957.1), were based on the previous publications defining the chemical defensome1–3.

Two main approaches were used to identify the genes related to the chemical defensome of the five fish species. First, we searched the current annotations in NCBI for Atlantic cod or ENSEMBL for zebrafish, stickleback, killifish, and medaka using gene names. For the well-annotated zebrafish genome, this approach successfully identified the genes that are part of the chemical defensome, as previously mapped by Stegeman, et al.3. Alternative gene sequences, e.g. splice variants, were removed when identifying the number of genes within the different gene families, but included in the RNA-Seq analyses.

However, only relying on annotations will not identify all defensome genes in the other less characterized fish genomes. Thus, secondly, we also performed hidden Markov model (HMM) searches using HMMER and Pfam profiles representing protein families that are part of the chemical defensome (available at FAIRDOMHub: https://doi.org/10.15490/fairdomhub.1.datafile.3956.1) in the genomes of the remaining four fish species. Putative orthologs of the retrieved protein sequences were identified using reciprocal best hit BLAST searches against the well-annotated zebrafish proteome. To capture any species-specific duplications in the fish genomes compared to the zebrafish reference genome, hits from one-way BLAST hits were also included. The identified peptide sequence IDs were subsequently converted to their related gene IDs using the BioMart tool on ENSEMBL (https://m.ensembl.org/biomart/martview) and R package “mygene” (https://doi.org/doi:10.18129/B9.bioc.mygene). Finally, the resulting gene lists were refined to contain only members of gene families and subfamilies related to the chemical defensome, using the same defensome gene lists as in the first approach (https://doi.org/10.15490/fairdomhub.1.datafile.3957.1).

Transcription of chemical defensome genes in early development

No embryos were directly used in this study. RNA-Seq datasets of early developmental stages of zebrafish (expression values in Transcripts Per Million from ArrayExpress: E-ERAD-475) and stickleback (sequencing reads from NCBI BioProject: PRJNA395155) were previously published by White, et al.25 and Kaitetzidou, et al.26, respectively.

For stickleback, embryos were sampled at early morula, late morula, mid-gastrula, early organogenesis, and 24 h post hatching (hph). The sequencing data was processed and analyzed following the automatic pipeline RASflow27. Briefly, the reads were mapped to the stickleback genome downloaded from ENSEMBL of version release-100. HISAT228 was used as aligner and featureCounts29 was used to count the reads. The library sizes were normalized using Trimmed Mean of M values (TMM)30 and the Counts Per Million (CPM) were calculated using R package edgeR31. The source code and relevant files can be found on GitHub: https://github.com/zhxiaokang/fishDefensome/tree/main/developmentalStages/stickleback/RASflow.

The zebrafish dataset included 18 time points from one cell to five days post fertilization (dpf). In order to best compare to the available stickleback developmental data, we chose to include the following time points in this study: Cleavage_2 cell (early morula), blastula_1k cell (late morula), mid-gastrula, segmentation_1-4-somites (early organogenesis), and larval_protruding_mouth (24 hph).

The temporal clustering was performed on both species. The R package “tscR”32, which clusters time series data using slope distance was applied here, to account for the gene expression variation pattern over time, instead of the absolute gene expression values.

Exposure response of defensome genes in zebrafish early development

RNA-Seq datasets of zebrafish exposed to benzo(a)pyrene (B(a)P) (gene counts from NCBI GEO: GSE64198) were previously published by Fang, et al.33. Briefly, the datasets are results from the following in vivo experiments: Adult parental zebrafish were waterborne-exposed to 50 μg/L B(a)P or 0.1 mL/L ethanol vehicle control, and their eggs collected from days 7 to 11. The eggs were further raised in control conditions or continuously exposed to 42.0 ± 1.9 μg/L B(a)P until 3.3 and 96 (hours post fertilization, hpf), where mid-blastula state and complete organogenesis is reached, respectively. At 3.3 or 96 hpf, embryos (50/pool) or larvae (15/pool) were pooled for RNA isolation, giving three replicate groups of control and exposed at 3.3 hpf and two replicate groups of control and exposed at 96 hpf.

The RNA-Seq reads were mapped to the zebrafish genome and the genes were quantified in the original publication by Fang, et al.33. In our study, the gene counts were then normalized followed by differential expression analysis using edgeR31 and the chemical defensome genes were then identified based on our defensome gene list of zebrafish.

Results and discussion

Chemical defensome genes present in model fish genomes.

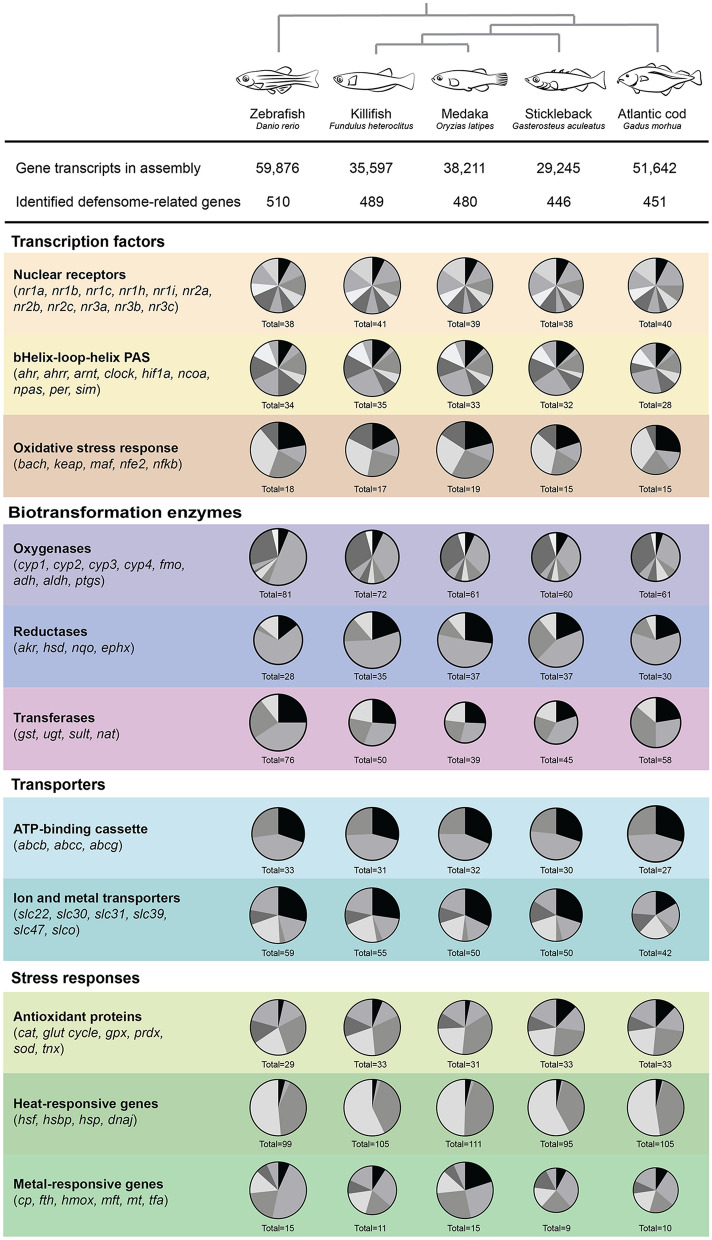

The full complement of chemical defensome genes in zebrafish, killifish, medaka, stickleback and Atlantic cod are available at the FAIRDOMHub (https://doi.org/10.15490/fairdomhub.1.datafile.3958.1). In short, genome analyses of the selected fish species show that the number of chemical defensome genes range from 446 in stickleback to 510 in zebrafish (Fig. 1). Although the number of putative homologous genes in each subfamily varies, we found that all gene subfamilies of the chemical defensome is represented in each species, except for the absence of pxr in stickleback and Atlantic cod. While we believe that all major protein families that are related to the chemical defensome are included, we cannot preclude that there are individual genes that are not identified due to the genome quality and level of annotation.

Figure 1.

Chemical defensome genes in five model fish species. The genes were identified by searching gene names and using HMMER searches with Pfam profiles, followed by reciprocal or best-hit blast searches towards the zebrafish proteome. The gene families are organized in categories following Gene Ontology annotations and grouped by their role in the chemical defensome. The size of the disk represents the relative number of genes in the different fish genomes within each group, with the number of genes in a specific gene family as slices.

Soluble receptors and transcription factors

Stress-activated transcription factors serve as important first responders to many chemicals, and in turn regulate the transcription of other parts of the chemical defensome. Nuclear receptors (NRs) are a superfamily of structurally similar, ligand-activated transcription factors, where members of subfamilies NR1A, B, C, H, and I (such as retinoid acid receptors, peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptors, and liver X receptor), NR2A and B (hepatocyte nuclear factors and retinoid x receptors), and NR3 (such as estrogen receptors and androgen receptor) are involved in the chemical defense34–37. All NR subfamilies were found in the five fish genomes, except for the nr1i2 gene (Supplementary Table 2, available at FAIRDOMHub: 10.15490/fairdomhub.1.document.925.3). We did not find an expansion of any of the groups that indicated an evolved compensational receptor in the absence of pxr.

NR1I2, or pregnane x receptor (PXR) is considered an important xenosensor responsible for the transcription of many genes involved in the biotransformation of xenobiotics10,38. We have previously shown that loss of the pxr gene has occurred multiple times in teleost fish evolution9, including in Atlantic cod and stickleback. Interestingly, our searches did not reveal a pxr gene in the ENSEMBL genome assembly of Japanese medaka HdRr, which is considered the reference medaka strain39,40. In contrast, a pxr gene is annotated in the ENSEMBL genomes of the closely related medaka strains HSOK and HNI. Our previous study identified a sequence similar to zebrafish Pxr in the MEDAKA1 (ENSEMBL release 93) genome9, and a partial coding sequence (cds) of pxr is cloned from medaka genome41. However, the specific strain of these resources is not disclosed.

To assess the possible absence of pxr in the medaka HdRr strain, we also performed synteny analysis. In vertebrate species, including fish, pxr is flanked by the genes maats1 and gsk3b. These genes are also annotated in medaka HdRr, but the specific gene region has a very low %GC and low sequence quality. Thus, we suspect that the absence of pxr in the Japanese medaka HdRr genome is due to a sequencing or assembly error. However, until more evidence of its absence can be presented, we chose to include the medaka pxr gene (UniProt ID A8DD90_ORYLA) in our resulting list of medaka chemical defensome genes.

Other important transcription factors are the basic helix-loop-helix Per-Arnt-Sim (bHLH/PAS) proteins and the oxidative stress-activated transcription factors. bHLH/PAS proteins are involved in circadian rhythms (such as clock and arntl), hypoxia response (such as hif1a and ncoa), development (such as sim), and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway (ahr and arnt) (as reviewed by Gu, et al.42 and Kewley, et al.43), while oxidative stress-activated transcription factors respond to changes in the cellular redox status and promote transcription of antioxidant enzymes44,45. The latter protein family includes nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2 (NFE2), NFE2-like (NFE2L, also known as NRFs) 1, 2, and 3, BACH, the dimerization partners small-Mafs (MafF, MafG and MafK), and the inhibitor Kelch-like-ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1)46. Putative orthologs for all these subfamilies were identified in all five fish genomes.

Biotransformation enzymes

In the first phase of xenobiotic biotransformation, a set of enzymes modifies substrates to more hydrophilic and reactive products. The most important gene family of oxygenases is the cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYPs, EC 1.14.-.-), a large superfamily of heme-proteins that initiate the biotransformation of numerous xenobiotic compounds through their monooxygenase activity47. The subfamilies considered to be involved in xenobiotic transformation is Cyp1, Cyp2, Cyp3, and Cyp4, and genes of these families were found in all fish species. Interestingly, our results show that the zebrafish genome holds almost twice as many genes belonging to the cyp2 subfamily compared to the other four fish species. This is in line with previous findings comparing the CYPome in zebrafish to that in human and cod48,49, but the reason for the cyp2 gene bloom in zebrafish remains unknown. The number of genes in each subfamily differs slightly from previous mappings of the CYPome of zebrafish and cod48,49 (Supplementary Table 3, available at FAIRDOMHub: 10.15490/fairdomhub.1.document.925.3). This is likely explained by the sequence and annotation improvement in latest genome assemblies.

Other oxygenases include flavin-dependent monooxygenases (FMOs, EC 1.14.13.8), aldehyde dehydrogenases (ALDH, EC 1.2.1.3), alcohol dehydrogenases (ADHs, EC 1.1.1.1), and prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthases (PTGS, also known as cyclooxygenases, EC 1.14.99.1). Of these, aldh represented the largest family in our study, with number of putative gene orthologs ranging from 19 to 22 genes. In comparison, fmo had only one gene in zebrafish and four in killifish and cod.

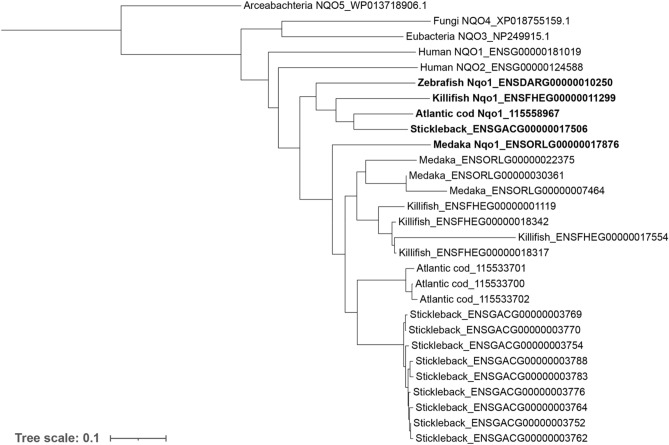

Furthermore, reductases modify chemicals by reducing the number of electrons. Reductases include aldo–keto reductases (AKRs, EC 1.1.1), hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases (HSDs, EC 1.1.1), epoxide hydrolases (EPHXs, EC 3.3.2.9 and EC 3.3.2.10), and the NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductases (NQOs, EC 1.6.5.2). Interestingly, the number of putative orthologous genes in the nqo reductase families varied greatly between the fish species, ranging from one in zebrafish to ten in stickleback. A phylogenetic analysis of the evolutionary relationship of the sequences (Fig. 2), shows that all fish species have a Nqo1 annotated gene. In addition, medaka, killifish, stickleback and cod have three to nine other closely related genes. The endogenous functions of the different nqo genes found in fish, and thus the consequences of their putative evolutionary gain in teleost fish, remains unknown and should be studied further.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductases (NQO), also known as DT-diaphorase (DTD). Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree was built using Clustal Omega50 with standard settings. The tree was drawn using iTol51, and rooted with the archaebacterial NQO5.

In the second phase of biotransformation, endogenous polar molecules are covalently attached to xenobiotic compounds by transferases, thus facilitating the generation of more water-soluble products that can be excreted from the cells and the organism. An important class of such conjugating enzymes are glutathione S-transferases (GSTs, EC 2.5.1.18), which are divided into three superfamilies: the cytosolic GSTs (divided in six subfamilies designated alpha through zeta), the mitochondrial GST (GST kappa) and the membrane-associated GST (designated MAPEG)52,53. Other classes of conjugating enzymes in vertebrates include cytosolic sulfotransferases (SULTs, EC 2.8.2), UDP-glucuronosyl transferases (UGTs, EC 2.4.1.17), N-acetyltransferases (NATs, EC 2.3.1.5), and arylamine NATs (aa-NAT).

Our searches identified a gstp gene in zebrafish and cod genomes, but not in medaka, killifish and stickleback. Gstp is previously identified as the major Gst isoenzyme in livers of marine salmonid species54. Although the specificity of GSTP is not fully understood, its activity seems related to oxidative stress55. Furthermore, the total number of gst encoding genes was substantially higher in zebrafish (19 genes) compared to the other fish species (9 in stickleback, 10 in medaka, and 13 in killifish and in cod).

Similarly, the number of ugt encoding genes is considerably higher in zebrafish compared to the other fish genomes. Whereas 31 ugt genes were found annotated in zebrafish, we only identified 15 in killifish, 11 genes in medaka, 17 in stickleback, and 16 in cod. All Ugt subfamilies (ugt1, -2, -5, and -8) are represented in the different fish genomes but include a varying number of homologs. Previous publications indicate that the number of zebrafish ugt encoding genes are as high as 45, with the ugt5 subfamily only existing in teleost and amphibian species56. One study has found cooperation of NQO1 and UGT in detoxification of vitamin K3 in HEK293 cell line57. However, it is not known if there is any correlation between the high number of ugt genes and low number of nqo genes in zebrafish, relative to the other fish species.

Transporter proteins

Energy-dependent efflux transport of compounds across both extra- and intracellular membranes is facilitated by ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters. In humans, the ABCs are organized into seven subfamilies, named ABC A through G, where proteins of B (also known as MDR1), C and G are known to be involved in multidrug resistance (MDR)58. Our results showed that the number of abc genes in each subfamily were quite similar between the fish, except for Atlantic cod that showed a lower number of abcb and abcc compared to the other species (Supplementary Table 4, available at FAIRDOMHub: 10.15490/fairdomhub.1.document.925.3). Abcc1, also known as multidrug resistance-associated protein (mrp1) were identified in all species, whereas abcb1, also known as multidrug resistance protein (mdr1), were only observed in killifish. Neither was abcb5, which is suggested as a close ortholog to abcb1 in zebrafish, found in medaka, stickleback and cod, which is in line with previous results59. A separate group of proteins is called the Solute Carrier (SLC) ‘superfamily,’ which consists of diverse non-homologous groups of ion and metal transporting membrane proteins that facilitate passive transport60. Relevant solute carrier proteins include the drug transporting SLC22 and SLC47, the zinc transporting SLC30 and SLC39, the copper transporting SLC31, and the organic anion transporting SLCO61.

We found that the number of abcb, abcc, abcg, slc, and slco genes was similar between the fish species, with zebrafish holding a slightly higher number of homologs. MDR and P-glycoproteins have been relatively understudied in fish62–64. A clade of abch transporters related to abcg is found in some fish species, including zebrafish, but not in Japanese medaka, stickleback and cod65. However, as the endogenous function of these genes are not determined, we have not included them specifically into this study.

Antioxidant proteins

Antioxidant proteins protect against harmful reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide anions, hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals that are formed as by-products in many physiological processes66,67. The enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD, EC 1.15.1.1) catalyze the conversion of superoxide, one of the most abundant ROS species, to hydrogen peroxide68. The further detoxification of hydrogen peroxide can be performed by catalases (CAT, EC 1.11.1.6) and glutathione peroxidases (GPXs, EC 1.11.1.9)66. The antioxidants also include the glutathione (GSH) system, where GSH is supplied by reduction of gluthatione disulphide by glutathione reductase (GSR, EC 1.8.1.7), or by de novo synthesis via glutamate cysteine ligase (made up by the subunits GCLC and GCLM, EC 6.3.2.2), and glutathione synthase (GSS, EC 6.3.2.3).

Together with xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes, induction of genes and enzymatic activity involved in antioxidant defense has long been recognized as a gold standard in the biomarker approach to environmental studies69. Putative orthologs for all antioxidant genes were clearly identified in the five fish genomes examined.

Heat-responsive genes

Heat-responsive genes represent the largest functional group of genes in the chemical defensome and act in response to a wide range of endogenous and exogenous stressors, such as temperature-shock and heavy metal exposure70. In response to stressors, heat shock factors (HSFs) regulate transcription of heat shock proteins (HSPs)71. HSPs are divided into families based on their molecular size, and each subfamily has various cellular tasks, including cytoskeleton modulation, protein folding, and chaperone functioning72,73.

Not much is known about the heat shock protein expression in fish70. We found that all fish genomes hold putative orthologs of hsf, heat shock binding proteins (hsbp) and hsp. The number of putative orthologs of hsp and dnaj (formerly known as hsp40) is high in all fish genomes, with the highest number in killifish with 40 and 60 genes, respectively.

Metal-responsive genes

In response to heavy metals such as zinc, cadmium, and copper, metal-responsive transcription factors (MTFs) induce expression of metal-binding proteins, such as metallothioneins (MT), ferritin (ferritin heavy subunit fth/fthl); heme oxygenases (hmox, EC 1.14.99.3,), transferrins (tfa), and ferroxidase (also known as ceruloplasmin, cp; EC 1.16.3.1)74.

In our study, we found putative orthologs for all gene families, except a mt encoding gene in stickleback or cod genome assemblies. Metallothioneins are cysteine-rich, low molecular weight proteins, and can thus be lost due to low-quality sequence and subsequent assembly. In discrepancy with the genome data, Mts are previously described in both Atlantic cod (Hylland et al. 1994) and stickleback (Uren Webster 2017), and these protein IDs were included into our overview. Similarly, only one or two mt genes were found in zebrafish, killifish, and medaka, and this low number is in line with previous findings on metallothioneins in fish75.

Expression of defensome genes during early development of fish

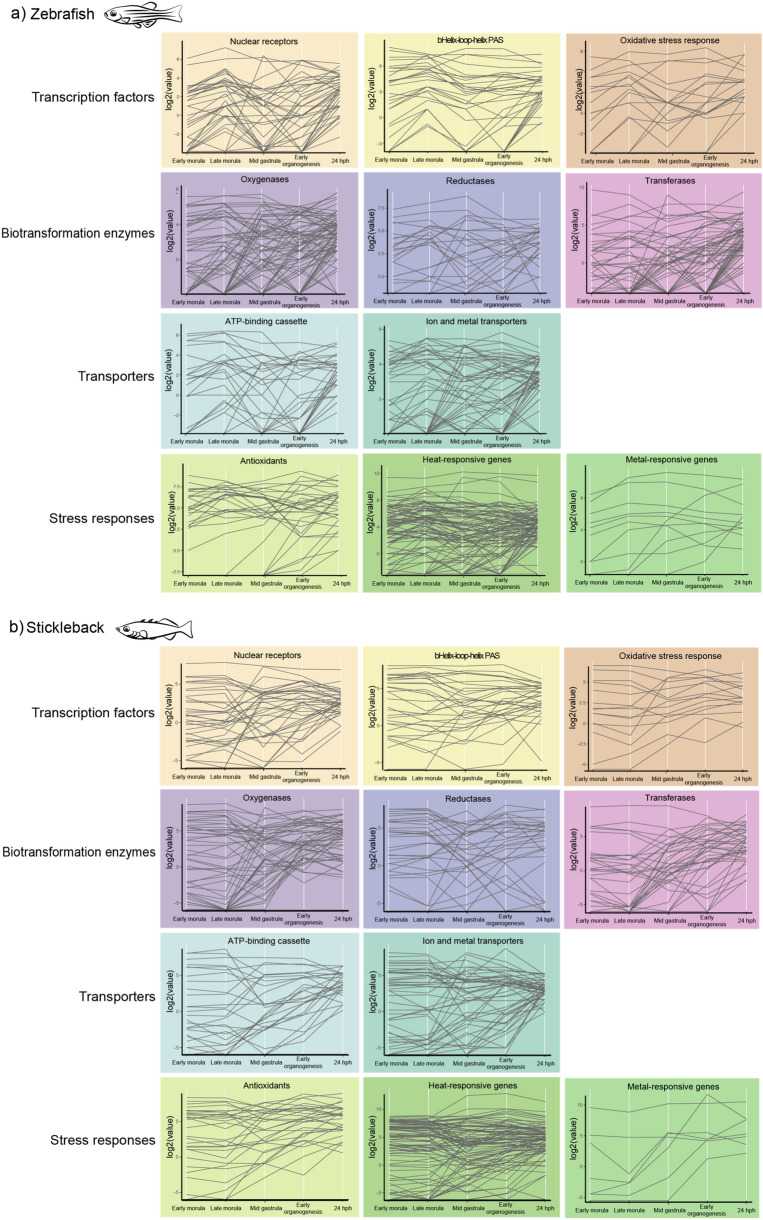

The developmental stage at which a chemical exposure event occurs greatly impacts the effect on fish. In general, chemical exposures during early developmental stages of fish cause the most adverse and detrimental effects. Based on data from the ECETOC Aquatic Toxicity database, fish larvae are more sensitive to substances than embryos and juveniles76. However, it is not known how the sensitivity is correlated to the expression of the chemical defensome. As examples in this study, we mapped the expression of the full complement of chemical defensome genes during early development using previously published transcriptomics data from zebrafish25 and stickleback26 (Fig. 3, relevant data available on FAIRDOMHub: https://doi.org/10.15490/fairdomhub.1.assay.1379.1).

Figure 3.

Transcription of chemical defensome genes in early development of (a) zebrafish (Danio rerio) and (b) stickleback (Gasterasteus aculeatus). Absolute transcription values (log2 scale) of defensome genes, grouped into their functional category, are shown at early morula, late morula, mid gastrula, early organogenesis, and 24 h post hatching (hph).

Our results showed that many defensome genes are not expressed until after hatching in both species. The delayed genes belonged to all functional categories but were especially prominent where there are several paralogs within the same gene subfamily, for example the transporters and the transferases (Fig. 3). In contrast, the heat shock proteins hspa8 and hsp90ab1 were highly transcribed at all stages in both zebrafish and stickleback (Fig. 3). Hspa8 is a constitutively expressed member of the Hsp70 subfamily, which is previously known as important in rodent embryogenesis77. The role of Hsp90ab1 in development is less known78.

Using temporal clustering analysis (relevant data available on FAIRDOMHub: https://doi.org/10.15490/fairdomhub.1.assay.1379.2), we further investigated whether the absence of pxr in stickleback lead to a shift in target gene expression during development. Our results did not find clustering patterns of genes related to pxr, or any other transcription factor, in neither fish. Cyp3a65, a well known zebrafish Pxr target gene79, were transcribed at the late morula stage in stickleback and at the mid gastrula stage in zebrafish. This difference could possibly be explained by the difference in synteny of cyp3a65 in zebrafish and cyp3a65 in a number of fish species49. In a previous study, zebrafish cyp3a65 appear to have bimodal expression49, but this was not observed in the set of developmental stages included in our study. For the glutathione transferases, we found substantial variations in expression between different genes, which is also previously shown at the protein expression and enzyme activity level80,81. Thus, although it has been demonstrated that genes regulated by common transcription factors tend to be located spatially close in the genome sequence and thus facilitate a concerted gene expression82, we did not observe such patterns in our datasets.

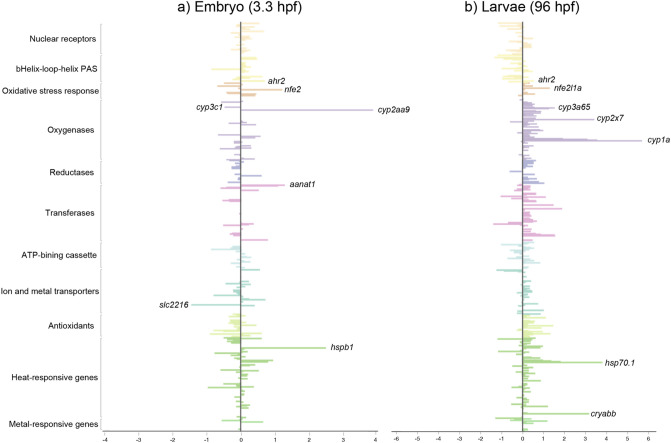

Exposure response of the defensome genes

Next, we studied the transcriptional effect of waterborne exposure to 42.0 ± 1.9 μg/L benzo(a)pyrene (BaP), a well-known Ahr agonist, on the chemical defensome genes at embryonic and larval stages of zebrafish (relevant data available on FAIRDOMHub: https://doi.org/10.15490/fairdomhub.1.datafile.3961.1). In the original publication of the RNA-Seq data, Fang, et al.33 showed that the number of differentially expressed genes increased from 8 at the embryonic stage (3.3. hpf) to 1153 at the larvae stage (96 hpf), where the affected pathways included the Ahr detoxification pathway. Focusing on the chemical defensome genes, we show that following exposure at the larval stage, but not embryonic stage, we found a trend of clustered regulation of functionally grouped genes (Fig. 4). In general, transcription factors were downregulated, whereas biotransformation enzymes were upregulated. However, the BaP xenosensor, ahr2, and the oxidative stress-responsive transcription factor nfe2l1a, were both upregulated (1.4- and 2.4-fold, respectively). The crosstalk between these transcription factors following exposure to chemical stressors is previously studied in zebrafish83,84. Furthermore, we showed that at the embryonic stage the exposure led to a strong upregulation of cyp2aa9 (14-fold) and an increased transcription of single genes such as ahr2, nfe2, aanat1, and hspb1 (Fig. 4a). These effects were not identified using the differential expression analysis in the original study but can indicate low level changes in the chemical defensome signaling network. Cyp1a, which is an established biomarker of exposure to BaP and other polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) in fish85–87, was not induced at this stage. However, as described in the original study33, we found a strong induction of cyp1a (50-fold) at the larvae developmental stage (Fig. 4b). Induction of zebrafish cyp1a is previously shown from 24 hpf following exposure to the Ahr model-agonist TCDD88.

Figure 4.

Transcriptional responses on chemical defensome genes in (a) zebrafish embryo (3.3 h post fertilization (hpf)) and (b) zebrafish larvae (96 hpf) following exposure to benzo(a)pyrene. The transcription is shown as log2 fold change between exposed and control group at each timepoint. The genes are grouped into their functional categories in the chemical defensome and the name of some genes are indicated for clarity.

Summary and perspectives

The chemical defensome is essential for detoxification and subsequent clearance of xenobiotic compounds, and the composition of the defensome can determine the toxicological responses to many chemicals. Based on the previous annotations of the chemical defensome in other species, our results showed that the number of chemical defensome genes ranged from 446 in three-spined stickleback to 510 in zebrafish due to a varying number of gene homologs in the evolutionarily conserved modules. Of the five fish included in this study, zebrafish has the highest number of gene homologs in most gene families, with the interesting exception of the nqo reductases where medaka, killifish, cod, and especially stickleback, had retained a higher number of homologs compared to only one in zebrafish.

We have previously shown that the stress-activated receptor pxr gene has been lost in stickleback and cod, but is retained in zebrafish, Atlantic killifish and medaka9. The main objective of this study was to explore whether other compensatory genes or signaling pathways had evolved in its absence. However, based on our results, we did not observe such compensatory mechanisms. Still, there could be other variables linked to the absence of pxr that fell outside the scope of this study, such as sequence divergences, regulatory elements and expression variation.

Furthermore, we analyzed the transcriptional levels of the defensome genes in early development of zebrafish and stickleback. Importantly, the full complement of defensome genes was not transcribed until after hatching. Comparing the transcriptional effects of waterborne exposure to BaP, a well-known Ahr agonist, on chemical defensome genes at two developmental stages of zebrafish, we found a trend for clustering of gene functional groups at the larvae, but not embryonic, stage.

This study presents characterization of the chemical defensome in five different fish species and at different developmental stages as a way of illustrating and understanding genome-based interspecies and stage-dependent differences in sensitivity and response to chemical stressors. As this study has focused on the presence or absence of chemical defensome genes, and the variation across model teleosts, the role of intraspecies, strain-dependent variants in defensome genes were not included. Several studies have identified defensome gene variants linked to pollution tolerance in fish populations, e.g. in the Ahr pathway89–92. In the study by Lille-Langøy, et al.93, we previously showed that single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the zebrafish pxr gene affect ligand activation patterns. Thus, sequence variation and variation in expression and inducibility also play important roles in chemical sensitivity differences between species, and SNP and copy number variation contributes to sensitivity differences within species.

Traditionally, studying single molecular biomarkers of exposure has proven very useful in toxicological studies69,94. Now, the recent advances in omics technologies enable a more holistic view of toxicological responses, including gene set enrichment analysis and pathway analysis approaches95–98. However, these analyses can be challenging when working with less studied and annotated species, such as marine teleosts. As seen from our results, studying the full gene complement of the chemical defense system can identify trends of grouped responses that can provide a better understanding of the overall orchestrated effects to chemical stressors, e.g. applied in genome-scale metabolic reconstructions99. Such insights will be highly useful in chemical toxicity testing and environmental risk assessment.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the Norwegian Research Council as part of the iCOD and iCOD 2.0 projects (Grant Nos. 192441/I30 and 244654/E40), and the dCod 1.0 project (Grant No. 248840) which is part of Centre for Digital Life Norway. The American collaborators were funded by the National Institute of Health (USA) NIH P42ES007381 (Boston University Superfund Center to JJS and JVG), NIH R21HD073805 (JVG) and NHI R01ES029917 (JVG) grants. The Ocean Outlook exchange program funded the trans-Atlantic collaboration. The authors are thankful for the constructive comments from Dr. Adele Mennerat in the writing process.

Author contributions

M.E. and X.Z. contributed equally to the study design and execution, and wrote the main draft of the manuscript. O.A.K., J.V.G., J.J.S., I.J. and A.G. contributed to the design of the study, discussion of results, and writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the submitted article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Marta Eide and Xiaokang Zhang.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-89948-0.

References

- 1.Goldstone JV, et al. The chemical defensome: Environmental sensing and response genes in the Strongylocentrotus purpuratus genome. Dev. Biol. 2006;300:366–384. doi: 10.1016/J.Ydbio.2006.08.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstone JV. Environmental sensing and response genes in cnidaria: the chemical defensome in the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2008;24:483–502. doi: 10.1007/S10565-008-9107-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stegeman, J. J., Goldstone, J. V. & Hahn, M. E. in Fish physiology: Zebrafish Ch. 10, (Elsevier, 2010).

- 4.Shinzato C, Hamada M, Shoguchi E, Kawashima T, Satoh N. The repertoire of chemical defense genes in the coral Acropora digitifera genome. Zool. Sci. 2012;29:510–517. doi: 10.2108/zsj.29.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yadetie F, et al. Conservation and divergence of chemical defense system in the tunicate Oikopleura dioica revealed by genome wide response to two xenobiotics. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Marco L, et al. The choreography of the chemical defensome response to insecticide stress: insights into the Anopheles stephensi transcriptome using RNA-Seq. Sci. Rep. 2017 doi: 10.1038/srep41312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dehal P, Boore JL. Two rounds of whole genome duplication in the ancestral vertebrate. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:1700–1708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer A, Van de Peer Y. From 2R to 3R: evidence for a fish-specific genome duplication (FSGD) BioEssays. 2005;27:937–945. doi: 10.1002/bies.20293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eide M, et al. Independent losses of a xenobiotic receptor across teleost evolution. Sci. Rep. 2018 doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28498-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blumberg B, et al. SXR, a novel steroid and xenobiotic-sensing nuclear receptor. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3195–3205. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.20.3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kliewer SA, Goodwin B, Willson TM. The nuclear pregnane X receptor: a key regulator of xenobiotic metabolism. Endocr. Rev. 2002;23:687–702. doi: 10.1210/Er.2001.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill AJ, Teraoka H, Heideman W, Peterson RE. Zebrafish as a model vertebrate for investigating chemical toxicity. Toxicol. Sci. 2005;86:6–19. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Embry MR, et al. The fish embryo toxicity test as an animal alternative method in hazard and risk assessment and scientific research. Aquat. Toxicol. 2010;97:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burnett KG, et al. Fundulus as the premier teleost model in environmental biology: Opportunities for new insights using genomics. Comp. Biochem. Phys. D. 2007;2:257–286. doi: 10.1016/j.cbd.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katsiadaki I, Scott AP, Mayer I. The potential of the three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus L.) as a combined biomarker for oestrogens and androgens in European waters. Mar. Environ. Res. 2002;54:725–728. doi: 10.1016/S0141-1136(02)00110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hylland K, et al. Water column monitoring near oil installations in the North Sea 2001–2004. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2008;56:414–429. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooks SJ, et al. Water column monitoring of the biological effects of produced water from the ekofisk offshore oil installation from 2006 to 2009. J. Toxicol. Environ. Heal. A. 2011;74:582–604. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2011.550566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holth TF, Beylich BA, Camus L, Klobucar GI, Hylland K. Repeated sampling of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) for monitoring of nondestructive parameters during exposure to a synthetic produced water. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A. 2011;74:555–568. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2011.550564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Star B, et al. The genome sequence of Atlantic cod reveals a unique immune system. Nature. 2011;477:207–210. doi: 10.1038/Nature10342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yadetie F, et al. RNA-Seq analysis of transcriptome responses in Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) precision-cut liver slices exposed to benzo[a]pyrene and 17 alpha-ethynylestradiol. Aquat. Toxicol. 2018;201:174–186. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yadetie F, Karlsen OA, Eide M, Hogstrand C, Goksøyr A. Liver transcriptome analysis of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) exposed to PCB 153 indicates effects on cell cycle regulation and lipid metabolism. BMC Genomics. 2014 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bizarro C, Eide M, Hitchcock DJ, Goksøyr A, Ortiz-Zarragoitia M. Single and mixture effects of aquatic micropollutants studied in precision-cut liver slices of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) Aquat. Toxicol. 2016;177:395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2016.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hansen BH, et al. Embryonic exposure to produced water can cause cardiac toxicity and deformations in Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) and haddock (Melanogrammus aeglefinus) larvae. Mar. Environ. Res. 2019;148:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2019.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eide M, Karlsen OA, Kryvi H, Olsvik PA, Goksøyr A. Precision-cut liver slices of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua): An in vitro system for studying the effects of environmental contaminants. Aquat. Toxicol. 2014;153:110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2013.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White RJ, et al. A high-resolution mRNA expression time course of embryonic development in zebrafish. Elife. 2017 doi: 10.7554/eLife.30860.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaitetzidou E, Katsiadaki I, Lagnel J, Antonopoulou E, Sarropoulou E. Unravelling paralogous gene expression dynamics during three-spined stickleback embryogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2019 doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40127-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang XK, Jonassen I. RASflow: an RNA-Seq analysis workflow with Snakemake. BMC Bioinform. 2020 doi: 10.1186/s12859-020-3433-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim D, Landmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12:357–U121. doi: 10.1038/Nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:923–930. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson MD, Oshlack A. A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.tscR: A time series clustering package combining slope and Frechet distances. v. R package version 1.2.0. (Bioconductor version: Release (3.12), 2020).

- 33.Fang XF, et al. Transcriptomic Changes in Zebrafish Embryos and Larvae Following Benzo[a]pyrene Exposure. Toxicol. Sci. 2015;146:395–411. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfv105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mangelsdorf DJ, et al. The nuclear receptor superfamily - the 2nd decade. Cell. 1995;83:835–839. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jin LH, Li Y. Structural and functional insights into nuclear receptor signaling. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2010;62:1218–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aranda A, Pascual A. Nuclear hormone receptors and gene expression. Physiol. Rev. 2001;81:1269–1304. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bertrand S, et al. Unexpected novel relational links uncovered by extensive developmental profiling of nuclear receptor expression. Plos Genet. 2007;3:2085–2100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kretschmer XC, Baldwin WS. CAR and PXR: xenosensors of endocrine disrupters? Chem. Biol. Interact. 2005;155:111–128. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spivakov M, et al. Genomic and phenotypic characterization of a wild medaka population: towards the establishment of an isogenic population genetic resource in fish. G3. 2014;4:433–445. doi: 10.1534/g3.113.008722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirchmaier S, Naruse K, Wittbrodt J, Loosli F. The genomic and genetic toolbox of the teleost medaka (Oryzias latipes) Genetics. 2015;199:905–918. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.173849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Milnes MR, et al. Activation of steroid and xenobiotic receptor (SXR, NR1I2) and its orthologs in laboratory, toxicologic, and genome model species. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008;116:880–885. doi: 10.1289/Ehp.10853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gu YZ, Hogenesch JB, Bradfield CA. The PAS superfamily: sensors of environmental and developmental signals. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2000;40:519–561. doi: 10.1146/Annurev.Pharmtox.40.1.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kewley RJ, Whitelaw ML, Chapman-Smith A. The mammalian basic helix-loop-helix/PAS family of transcriptional regulators. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2004;36:189–204. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(03)00211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nguyen T, Sherratt PJ, Pickett CB. Regulatory mechanisms controlling gene expression mediated by the antioxidant response element. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2003;43:233–260. doi: 10.1146/Annurev.Pharmtox.43.100901.140229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oyake T, et al. Bach proteins belong to a novel family of BTB-basic leucine zipper transcription factors that interact with MafK and regulate transcription through the NF-E2 site. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:6083–6095. doi: 10.1128/MCB.16.11.6083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nguyen T, Nioi P, Pickett CB. The Nrf2-antioxidant response element signaling pathway and its activation by oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:13291–13295. doi: 10.1074/Jbc.R900010200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nelson DR, et al. Comparison of cytochrome P450 (CYP) genes from the mouse and human genomes, including nomenclature recommendations for genes, pseudogenes and alternative-splice variants. Pharmacogenetics. 2004;14:1–18. doi: 10.1097/01.Fpc.0000054151.92680.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karlsen OA, Puntervoll P, Goksøyr A. Mass spectrometric analyses of microsomal cytochrome P450 isozymes isolated from beta-naphthoflavone-treated Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) liver reveal insights into the cod CYPome. Aquat. Toxicol. 2012;108:2–10. doi: 10.1016/J.Aquatox.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goldstone JV, et al. Identification and developmental expression of the full complement of Cytochrome P450 genes in Zebrafish. BMC Genom. 2010 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Madeira F, et al. The EMBL-EBI search and sequence analysis tools APIs in 2019. Nucl. Acids Res. 2019;47:W636–W641. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v4: recent updates and new developments. Nucl. Acids Res. 2019;47:W256–W259. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hayes JD, Flanagan JU, Jowsey IR. Glutathione transferases. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2005;45:51–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nebert DW, Vasiliou V. Analysis of the glutathione S-transferase (GST) gene family. Hum. Genomics. 2004;1:460–464. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-1-6-460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dominey RJ, Nimmo IA, Cronshaw AD, Hayes JD. The major glutathione-S-transferase in salmonid fish livers is homologous to the mammalian Pi-class gst. Comp. Biochem. Phys. B. 1991;100:93–98. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(91)90090-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tew KD, et al. The role of glutathione S-transferase P in signaling pathways and S-glutathionylation in cancer. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011;51:299–313. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang HY, Wu Q. Cloning and comparative analyses of the zebrafish ugt repertoire reveal its evolutionary diversity. PLoS ONE. 2010 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nishiyama T, et al. Cooperation of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 and UDP-glucuronosyltransferases reduces menadione cytotoxicity in HEK293 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;394:459–463. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dean M, Hamon Y, Chimini G. The human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. J. Lipid Res. 2001;42:1007–1017. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2275(20)31588-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luckenbach T, Fischer S, Sturm A. Current advances on ABC drug transporters in fish. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2014;165:28–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hediger MA, et al. The ABCs of solute carriers: physiological, pathological and therapeutic implications of human membrane transport proteins: introduction. Pflug Arch. Eur. J. Phys. 2004;447:465–468. doi: 10.1007/S00424-003-1192-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roth M, Obaidat A, Hagenbuch B. OATPs, OATs and OCTs: the organic anion and cation transporters of the SLCO and SLC22A gene superfamilies. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012;165:1260–1287. doi: 10.1111/J.1476-5381.2011.01724.X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fischer S, et al. Abcb4 acts as multixenobiotic transporter and active barrier against chemical uptake in zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos. BMC Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-11-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jackson JS, Kennedy CJ. Regulation of hepatic abcb4 and cyp3a65 gene expression and multidrug/multixenobiotic resistance (MDR/MXR) functional activity in the model teleost, Danio rerio (zebrafish) Comp. Biochem. Phys. C. 2017;200:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ferreira M, Costa J, Reis-Henriques MA. ABC transporters in fish species: a review. Front. Physiol. 2014 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jeong CB, et al. Marine medaka ATP-binding cassette (ABC) superfamily and new insight into teleost Abch nomenclature. Sci. Rep. 2015 doi: 10.1038/srep15409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Droge W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol. Rev. 2002;82:47–95. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dupre-Crochet S, Erard M, Nuss O. ROS production in phagocytes: why, when, and where? J. Leukoc. Biol. 2013;94:657–670. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1012544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Deby C, Goutier R. New perspectives on the biochemistry of superoxide anion and the efficiency of superoxide dismutases. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1990;39:399–405. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90043-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van der Oost R, Beyer J, Vermeulen NPE. Fish bioaccumulation and biomarkers in environmental risk assessment: a review. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2003;13:57–149. doi: 10.1016/S1382-6689(02)00126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Iwama GK, Thomas PT, Forsyth RHB, Vijayan MM. Heat shock protein expression in fish. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 1998;8:35–56. doi: 10.1023/A:1008812500650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Morimoto RI. Cells in stress: transcriptional activation of heat-shock genes. Science. 1993;259:1409–1410. doi: 10.1126/Science.8451637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Basu N, et al. Heat shock protein genes and their functional significance in fish. Gene. 2002;295:173–183. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(02)00687-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kampinga HH, et al. Guidelines for the nomenclature of the human heat shock proteins. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2009;14:105–111. doi: 10.1007/S12192-008-0068-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brugnera E, et al. Cloning, chromosomal mapping and characterization of the human metal-regulatory transcription factor Mtf-1. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3167–3173. doi: 10.1093/Nar/22.15.3167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Smirnov LP, Sukhovskaya IV, Nemova NN. Effects of environmental factors on low-molecular-weight peptides of fishes: a review. Russ. J. Ecol. 2005;36:41–47. doi: 10.1007/s11184-005-0007-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hutchinson TH, Solbe J, Kloepper-Sams PJ. Analysis of the ECETOC aquatic toxicity (EAT) database: III: comparative toxicity of chemical substances to different life stages of aquatic organisms. Chemosphere. 1998;36:129–142. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(97)10025-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Luft JC, Dix DJ. Hsp70 expression and function during embryogenesis. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1999;4:162–170. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(1999)004<0162:Heafde>2.3.Co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Haase M, Fitze G. HSP90AB1: Helping the good and the bad. Gene. 2016;575:171–186. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.08.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kubota A, et al. Role of pregnane X receptor and aryl hydrocarbon receptor in transcriptional regulation of pxr, CYP2, and CYP3 genes in developing zebrafish. Toxicol. Sci. 2015;143:398–407. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tierbach A, Groh KJ, Schonenberger R, Schirmer K, Suter MJ. Glutathione S-transferase protein expression in different life stages of zebrafish (Danio rerio) Toxicol. Sci. 2018;162:702–712. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfx293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tierbach A, Groh KJ, Schonenberger R, Schirmer K, Suter MJ. Biotransformation Capacity of Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Early Life Stages: functionality of the Mercapturic Acid Pathway. Toxicol. Sci. 2020;176:355–365. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfaa073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang J, et al. Spatial clustering and common regulatory elements correlate with coordinated gene expression. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2019;15:e1006786. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hahn ME, Timme-Laragy AR, Karchner SI, Stegeman JJ. Nrf2 and Nrf2-related proteins in development and developmental toxicity: insights from studies in zebrafish (Danio rerio) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;88:275–289. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rousseau ME, et al. Regulation of Ahr signaling by Nrf2 during development: effects of Nrf2a deficiency on PCB126 embryotoxicity in zebrafish (Danio rerio) Aquat. Toxicol. 2015;167:157–171. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Goksøyr A. Purification of hepatic microsomal cytochromes P-450 from ß-naphthoflavone-treated Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua), a marine teleost fish. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1985;840:409–417. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(85)90222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Goksøyr A, Förlin L. The cytochrome P450 system in fish, aquatic toxicology, and environmental monitoring. Aquat. Toxicol. 1992;22:287–312. doi: 10.1016/0166-445X(92)90046-P. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stegeman JJ, Lech JJ. Cytochrome-P-450 monooxygenase systems in aquatic species: carcinogen metabolism and biomarkers for carcinogen and pollutant exposure. Environ. Health Perspect. 1991;90:101–109. doi: 10.2307/3430851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Andreasen EA, et al. Tissue-specific expression of AHR2, ARNT2, and CYP1A in zebrafish embryos and larvae: Effects of developmental stage and 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin exposure. Toxicol. Sci. 2002;68:403–419. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/68.2.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wirgin I, et al. Mechanistic basis of resistance to PCBs in Atlantic tomcod from the Hudson River. Science. 2011;331:1322–1325. doi: 10.1126/science.1197296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Oziolor EM, Bigorgne E, Aguilar L, Usenko S, Matson CW. Evolved resistance to PCB- and PAH-induced cardiac teratogenesis, and reduced CYP1A activity in Gulf killifish (Fundulus grandis) populations from the Houston Ship Channel, Texas. Aquat. Toxicol. 2014;150:210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Williams LM, Oleksiak MF. Ecologically and evolutionarily important SNPs identified in natural populations. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011;28:1817–1826. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Reid NM, et al. The genomic landscape of rapid repeated evolutionary adaptation to toxic pollution in wild fish. Science. 2016;354:1305–1308. doi: 10.1126/science.aah4993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lille-Langøy R, et al. Sequence variations in pxr (nr1i2) from zebrafish (Danio rerio) strains affect nuclear receptor function. Toxicol. Sci. 2019;168:28–39. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfy269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Peakall DB. The role of biomarkers in environmental assessment 1: introduction. Ecotoxicology. 1994;3:157–160. doi: 10.1007/Bf00117080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fabregat A, et al. Reactome pathway analysis: a high-performance in-memory approach. BMC Bioinform. 2017;18:142. doi: 10.1186/s12859-017-1559-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Martins C, Dreij K, Costa PM. The state-of-the art of environmental toxicogenomics: challenges and perspectives of "omics" approaches directed to toxicant mixtures. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019 doi: 10.3390/ijerph16234718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Brooks BW, et al. Toxicology advances for 21st century chemical pollution. One Earth. 2020;2:312–316. doi: 10.1016/j.oneear.2020.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hanna EM, et al. ReCodLiver0.9: overcoming challenges in genome-scale metabolic reconstruction of a non-model species. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020;7:591406. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.591406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.