Abstract

Background

Gastrointestinal (GI) complaints are common in primary care practices. The patient-centered medical home (PCMH) may improve coordination and collaboration by facilitating coordination across healthcare settings and within the community, enhancing communication between providers, and focusing on quality of care delivery.

Objective

To investigate the effect of integrated community gastroenterology specialists (ICS-GI) model within a large primary care practice.

Design

Retrospective cohort with propensity-matched historic controls.

Patients

We identified 265 patients who had a visit with one of our ICS-GI specialists and matched them (1:2) to 530 similar patients seen prior to the implementation of the ICS-GI model.

Main Measures

Frequency of diagnostic testing for GI indications, visits to our outpatient GI referral practice, emergency department and hospital utilization, and time to access of specialty care for the whole population and by GI condition group.

Key Results

Patients seen in our ICS-GI model had similar outpatient care utilization (OR = 1.0, 95% CI 0.7–1.4, p = 0.90), were more likely to have visits in primary care (OR OR=1.5, 95% CI 1.1–2.2, p = 0.02), and were less likely to have visits to our GI outpatient referral practice (OR = 0.3, 95% CI 0.2–0.7, p < 0.0001). Condition-specific analyses show that all GI conditions experienced decreased visits to the outpatient GI referral practice outside of patients with GI neoplasm. Populations did not differ in emergency department, hospital, or diagnostic utilization.

Conclusions

We observed that an embedded specialist in primary care model is associated with improved care coordination without compromising patient safety. The PCMH could be extended to include subspecialty care.

KEY WORDS: patient-centered medical home (PCMH), primary care, gastroenterology, health care utilization, patient-centered care

INTRODUCTION

Gastrointestinal (GI) complaints are common in primary care practices, with bowel disorders constituting approximately 8.7% and biliary and liver disorders 8.2% of medical appointments.1 In 2015, over 54.4 million outpatient visits for GI disease occurred across the USA, 3.0 million hospital admissions with a primary GI diagnosis code, and over 500,000 all-cause 30-day readmissions with a primary GI diagnosis code.2 Hepatitis, esophageal disorders, biliary tract disease, abdominal pain, and inflammatory bowel disease were the most expensive (in order).2 Estimated annual healthcare expenditures for GI diseases totaled $135.9 billion in 2015 and expenditures are anticipated to grow.2

Proposed driving factors for increased demand of GI services include higher rates of endoscopic procedures and the rising burden of hepatitis C that occur in the primary care setting.2,3 However, the increasing complexity of primary care patients along with the increasing specialization within GI practices can fragment care between primary and GI specialty providers. Models for increased collaboration and coordination between primary care and GI specialty providers include integrated primary care and hospital services for patients with GI conditions,4 and the use of electronic consultations (eConsults) by GI specialists into primary care settings.5

The patient-centered medical home (PCMH) may improve coordination and collaboration by facilitating coordination across healthcare settings and within the community, enhancing communication between providers, and focusing on quality of care delivery.6 Although definitions of PCMH do not explicitly state the inclusion of specialists, opportunities exist for care models to include specialty providers to facilitate timely access to high-quality care.

To investigate the effect on GI specialists embedded within primary care, we conducted a retrospective cohort study with propensity-matched historic controls evaluating the impact of this service on diagnostic testing, outpatient and emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and access to specialty care.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Populations

This study was conducted with patients impaneled in Mayo Clinic’s Employee and Community Health (ECH) practice. Mayo Clinic is a tertiary referral, vertically integrated, multispecialty group practice that utilizes a shared electronic health record (EHR).7 ECH is a PCMH including the divisions of Primary Care Internal Medicine, Family Medicine, and Community Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. ECH encompasses a main practice site with 186 primary care providers (PCPs) and three additional clinic sites with a total of 120 PCPs. ECH provides care to approximately 152,000 patients residing in and around Olmsted County, MN, resulting in an average of 136,234 evaluation and management (E&M) visits per year. ECH patients are assigned a physician, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant as their PCP, but ECH provides team-based primary care. We used de-identified patient information, for which written informed consent was not required. Therefore, the Mayo Clinic institutional review board exempted this study.

Integrated Community GI Model

The Mayo Integrated Community Specialist (ICS) model has been previously described.8 Prior to implementation of the ICS-GI model, the Mayo Clinic non-co-located standard gastrointestinal specialist (GI) referral practice provided consultation and longitudinal care for ECH as well as regional, national, and international patients. Beginning January 1, 2015, a 0.6 full-time equivalent (FTE) GI specialist was co-located within the main ECH practice site. Care management and scheduling support were also provided. ICS-GI utilizes a mix of scheduled appointments for face-to-face visits with new and return patients, unscheduled time for curbside and electronic consultations (eConsults), and follow-up care through EHR-generated patient messages and test results. The ICS-GI model is intended to serve patients who could benefit from a close partnership between primary and GI generalist care, as opposed to patients with advanced needs of subspecialty care. ICS-GI triage algorithms are used to direct patients who could benefit from collaborative care between PCPs and GI specialists into the ICS-GI model. Patient populations well served in this model include patients with new-onset or continuing gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, bloating, diarrhea, constipation, and gastrointestinal bleeding. Patients who may be better served in the GI outpatient practice could include those with suspected liver issues in need of a hepatobiliary specialist, or those with other specific GI diagnoses such as inflammatory bowel disease, GI neoplasia, or GI motility disorders. Diagnostic tests are orderable at the discretion of the PCP without need for prior approval by ICS-GI, but consultation with the ICS-GI consultation was available after January 1, 2015. In our study, cases were designated as patients seen for a face-to-face visit by an ICS-GI provider. Historic control patients were matched and sampled from the year prior to implementation of the ICS-GI model. This approach helps to avoid risk of referral bias within our sample.

Measures

Mayo Clinic billing data allowed for identification of patients and visit utilization tracking from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2016. ICS-GI patients were those identified as billed for an E&M consultation code for ICS-GI and with a disease relevant International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis code under five, indication-grouped categories: inflammatory bowel disease/abdominal pain, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)/esophagitis, diarrhea, gastroenterological neoplasm, and gastrointestinal bleeding/anemia (specific codes listed in Supplemental File). Historic controls were defined as patients with a diagnosis in the same five categories and billed for an E&M code with standard GI referral and no ICS-GI visit during the follow-up period. Included patients could have presented with more than one of the indication groups listed above.

Visit Utilization

The primary care visit most closely preceding the first ICS-GI visit (patients) or standard GI referral outpatient visit (historic controls) constituted the “anchor visit.” The mean, median, and interquartile range (IQR) of total outpatient, PCP, GI outpatient, and specialty outpatient referral visits were assessed over 1 year following the anchor visit. As a countermeasure for patient safety, we also calculated the number of emergency department visits and hospital discharges for the study period for each patient. Visits were counted independently and summed over the 12-month period following the anchor visit. As each patient required an ICS-GI visit or outpatient GI referral practice visit to be included as a patient or historic control, respectively, the first visit for each subject was excluded prior to calculating utilization. Visits were classified using Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and provider service location codes based on institutional administrative billing data.

Diagnostic Test Utilization

The first ICS-GI or GI standard referral visit was used as the anchor for diagnostic test utilization. We counted the number of upper endoscopy procedures, colonoscopy, or imaging diagnostics, abdominal computed tomography (CT), abdominal ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), other imaging related to a GI diagnosis, and a swallow or breath test completed as defined by a billed CPT in institutional administrative billing data. Diagnostic test utilization was ascribed to ICS-GI or GI outpatient referral practice if occurring in a window of 14 days prior to and/or 60 days following an outpatient visit for patients and historic controls, respectively.

Access to GI Services

The time to GI visit was calculated as the number of days between the dates of either the ICS-GI or GI outpatient referral visit and the most recent prior PCP visit prior based on E&M codes.

Propensity Score Development

Propensity scores for the likelihood of receiving the exposure (ICS-GI) were generated from a logistic regression model using the following baseline patient characteristics: age, gender, race, indication-grouped category, and weighted Charlson Comorbidity Index score9 as a proxy for patient complexity. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) uses historical billing data to calculate a 1-year risk of mortality from reported comorbid conditions, including cancer, heart disease, and HIV/AIDS. Each comorbidity present is assigned a score from 1 to 6, and the sum of all comorbidities weighted with patient demographic information creates a patient-level score; the lower the CCI score, the healthier the patient.9

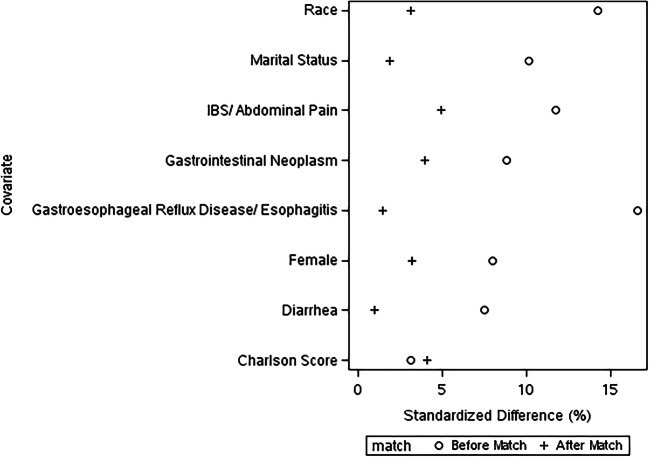

Historic controls for each case were sampled in a balanced, 1:n approach using greedy algorithm with nearest-neighbor matching using caliper width of 0.2 standard deviations of the propensity score. Patients and historic controls are randomly pre-sorted and one or more historic controls are matched for each patient based on the weighted sum of the absolute difference between patient and historic control within the caliper range. Balance of baseline patient characteristics between patients and controls was assessed graphically with balance of covariates achieved at an absolute standardized difference of 10%.

Statistical Analyses

Demographic characteristics of the ICS-GI (patient) and GI standard referral (historic control) cohorts were calculated as frequencies and proportions. Subjects without an anchoring PCP visit prior to a visit in ICS-GI or non-co-located GI were excluded from utilization analyses. Mean and median visit and diagnostic test utilization were calculated with associated standard deviations and interquartile ranges (IQR). Due to dispersion of the outcome data, negative binomial regression was used to ascertain differences in visit utilization, diagnostic test utilization, and full-day time to consult with the outpatient GI practice. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (OR, aOR) were calculated with associated 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and differences were considered significant if OR confidence intervals did not include 1.0. As the integrated specialist model may have differential impact based on patient need, we also looked for differences in utilization by GI indication following the same approaches as listed. All data management and statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) Version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

RESULTS

We identified 265 patients who had an E&M visit with one of our ICS-GI specialists during our study period, and matched them (1:2) to 530 patients with similar characteristics who were seen through a standard GI referral prior to the ICS-GI model (Table 1). Our match was able to balance covariates between patients and historical controls with an absolute standardized difference of 10% (Fig. 1). Included patients had an average age of 52 years of age, and were predominantly female (patients 65.7%, historic controls 64.2%), with low average comorbidity scores (patients 1.5, historic controls 1.4). A majority of our patients were seen for IBS/abdominal pain (patients 49.4%, historic controls 47.0%), followed by GERD/esophagitis (patients 20.4%, historic controls 19.8%) and diarrhea (patients 19.2%, historic controls 18.9%).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Matched Patients and Historic Controls

| ICS-GI (n = 265) |

Standard GI referral before matching (n = 1067) |

Standard GI referral (n = 530) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years (mean ± SD) | 52.5 ± 18.4 | 52.6 ± 17.8 | 51.8 ± 18.2 |

| Weighted Charlson Comorbidity Score (mean ± SD) | 1.5 ± 1.7 | 1.4 ± 1.6 | 1.4 ± 1.6 |

| Gender (n (%)) | |||

| Female | 174 (65.7%) | 661 (61.9%) | 340 (64.2%) |

| Male | 91 (34.3%) | 406 (38.1%) | 190 (35.8%) |

| Race (n (%)) | |||

| White | 235 (88.7%) | 978 (91.7%) | 472 (89.1%) |

| Black | 5 (1.9%) | 28 (2.6%) | 8 (1.5%) |

| Other | 11 (3.6%) | 26 (2.4%) | 23 (3.8%) |

| Asian | 8 (3.0%) | 26 (2.4%) | 19 (3.6%) |

| Unknown | 6 (2.3%) | 9 (0.8%) | 8 (1.5%) |

| Gastrointestinal conditions* (n (%)) | |||

| IBS/abdominal pain | 131 (49.4%) | 467 (43.8%) | 249 (47.0%) |

| Diarrhea | 51 (19.2%) | 174 (16.3%) | 100 (18.9%) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease/esophagitis | 54 (20.4%) | 292 (27.4%) | 105 (19.8%) |

| Gastrointestinal neoplasm | 45 (17.0%) | 217 (20.3%) | 98 (18.5%) |

| Gastrointestinal bleed/anemia | 27 (10.2%) | 122 (11.4%) | 54 (10.2%) |

| Marital status (n (%)) | |||

| Married | 172 (64.9%) | 723 (67.8%) | 341 (64.3%) |

| Divorced | 20 (7.5%) | 98 (9.2%) | 35 (6.6%) |

| Single | 57 (21.5%) | 203 (19.0%) | 123 (23.2%) |

| Widowed | 16 (6.0%) | 43 (4.0%) | 31 (5.8%) |

ICS-GI, integrated community specialist–gastrointestinal specialist; SD, standard deviation

*Patients may be diagnosed with more than one condition, and therefore may be represented in more than one condition category

Figure 1.

Balance of covariates between patients and historic controls before and after matching.

Visit Utilization

In 2014, 3062 visits occurred in the GI referral practice following a visit to primary care; there were fewer visits to the GI referral practice following a primary care visit in 2015 (2095). The rate of GI referral visits to total primary care visits remained consistent between 2014 and 2015 (1.9%). Overall, patients and historic controls had outpatient care utilization (patient median 5.0 visits, historic control mean 5.0 outpatient visits; OR = 1.0, 95% CI 0.8–1.1; p = 0.90) (Table 2). Compared to patients receiving a standard GI referral, patients seen in our ICS-GI practice were more likely to experience higher likelihood of visits to primary care (OR = 1.5, 95% CI 1.1–2.2; p = 0.02) and significantly lower likelihood of visits to our outpatient GI referral practice (OR = 0.8, 95% CI 0.2–0.7; p < 0.001). There were no significant differences in visits to other outpatient specialty practices, visits to the emergency department, or number of hospital discharges.

Table 2.

Differences in Utilization of Visits and Services Between Patients and Historic Controls, with Measures of Effect

| Patients, ICS-GI* (N = 254) | Historic controls, non-ICS-GI* (N = 376) | Negative binomial | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Median | IQR | Mean | SD | Median | IQR | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| All outpatient | 6.2 | 5.5 | 5.0 | (2.0, 9.0) | 6.5 | 5.4 | 5.0 | (2.0, 9.0) | 1.0 (0.7, 1.4) | p = 0.90 |

| Primary care outpatient | 3.1 | 3.3 | 2.0 | (1.0, 4.0) | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.0 | (1.0, 4.0) | 1.5 (1.1, 2.2) | 0.02 |

| Outpatient GI** | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.0 | (0.0, 0.0) | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.0 | (0.0, 1.0) | 0.3 (0.2, 0.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Other outpatient specialty | 3.0 | 3.4 | 2.0 | (0.0, 4.0) | 3.6 | 4.1 | 2.0 | (1.0, 5.0) | 0.8 (0.5, 1.2) | 0.05 |

| Emergency department | 0.8 | 1.5 | 0.0 | (0.0, 1.0) | 0.7 | 1.4 | 0.0 | (0.0, 1.0) | 1.4 (0.6, 3.1) | 0.40 |

| Inpatient | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.0 | (0.0, 0.0) | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.0 | (0.0, 0.0) | 1.1 (0.4, 2.8) | 0.90 |

ICS-GI, integrated community specialist–gastroenterology; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; GI, gastroenterology

When examining within our individual GI disease conditions, we observed similar utilization patterns with decreased likelihood of outpatient GI visits for those seen in the ICS-GI model than those seen prior to the model implementation for all condition groups except GI neoplasms: diarrhea OR = 0.3, 95% CI 0.2–0.6; p = 0.001; GERD/esophagitis OR = 0.4, 95% CI 0.2–0.7; p = 0.003; GI bleed/anemia OR = 0.4, 95% CI 0.2–1.0; p = 0.05; GI neoplasms OR = 0.6, 95% CI 0.2–1.4; p = 0.20; IBS/abdominal pain OR = 0.4, 95% CI 0.3–0.6; p < 0.0001. Additionally, GERD/esophagitis patients had increased likelihood of more primary care visits (aOR = 1.5, 95% CI 1.0, 2.2; p = 0.02).

Diagnostic Test Utilization

We did not observe any differences in diagnostic test utilization between those seen within our ICS-GI model and those seen prior to the ICS-GI model implementation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Differences in Utilization of Procedures Between Patients and Historic Controls, with Measures of Effect

| Patients, ICS-GI (N = 265) | Historic controls, non-ICS-GI (N = 530) | Negative binomial | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Median | IQR | Mean | SD | Median | IQR | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Upper endoscopy procedures | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.0 | (0.0, 1.0) | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.0 | (0.0, 1.0) | 1.0 (0.7, 1.3) | 0.90 |

| Colonoscopy or imaging | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.0 | (0.0, 1.0) | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.0 | (0.0, 1.0) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.2) | 0.60 |

| Abdominal computed tomography | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.0 | (0.0, 0.0) | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.0 | (0.0, 0.0) | 1.0 (0.7, 1.4) | 1.0 |

| Abdominal ultrasound | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | (0.0, 0.0) | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | (0.0, 0.0) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.7) | 0.80 |

| Magnetic resonance imaging | 0.05 | 0.2 | 0.0 | (0.0, 0.0) | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | (0.0, 0.0) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.1) | 0.09 |

| Other GI** imaging | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.0 | (0.0, 0.0) | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.0 | (0.0, 0.0) | 1.0 (0.7, 1.6) | 0.90 |

| Swallow or breath test | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.0 | (0.0, 0.0) | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | (0.0, 0.0) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.7) | 0.80 |

ICS-GI, integrated community specialist–gastroenterology; Std, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; GI, gastroenterology

Access to GI Services

Patients seen within our ICS-GI model were more likely to experience a shorter time to consult with GI following their PCP visit when compared with patients sent to our general GI referral practice for a face-to-face visit (adjusted OR 0.8; 95% CI 0.6, 1.0; P = 0.02). This decreased time to GI consult from their primary care appointment continued to be present for patients with GERD/esophagitis (OR = 0.6, 95% CI 0.4–0.9; p = 0.02), but we did not observe similar trends within our other GI condition groups (IBS/abdominal pain, diarrhea, GI neoplasm, GI bleed/anemia).

DISCUSSION

We observed that the ICS-GI model was associated with reduced time to specialty consultation, fewer visits to the standard GI referral practice without increased use of emergency services, and increased likelihood of visits with primary care. Subgroup analyses demonstrated that all disease groups experienced a decreased likelihood of visiting our standard GI referral practice except for those with GI neoplasm. The time to consultation with a GI specialist was improved particularly among those with GERD/esophagitis. We did not observe any differences in advanced imaging or procedures between the two models.

We observed fewer visits to the standard GI referral practice with the ICS-GI model. This finding is similar to that of Keely et al. who observed that use of a gastroenterologist eConsult service eliminated the need for a face-to-face consultation 68% of the time.5 Our findings are also similar to observations we made with an integrated ICS-neurology model which observed decreases in standard neurology referrals.10 Additionally, we anticipate that our ICS-GI availability via telephone and eConsult service, unmeasured in the current study, also facilitates decreased utilization of our GI referral practice; thereby, our findings may be underestimating the true impact of our ICS-GI model on referrals to our GI referral practice. Our findings provide additional information that an ICS-GI model can reduce time to face-to-face consultations when the specialist is embedded within the primary care practice.

We observed that the ICS-GI was associated with reduced time to specialty consultation and more primary care visits. Overall, our findings suggest improved coordination of GI services into primary care with the ICS-GI model. We believe that the model provides an opportunity for the ICS-GI specialist to work through non-visit care modalities (e-consults, EHR messaging) which provides guidance for the PCC to comfortably follow-up with the patient while reducing need for clinical GI outpatient visits. Significant barriers to delivery of coordinated care between primary and specialty care providers exist including difficulty in communication between providers, particularly regarding the reason for and expectations of the specialty consult request, and lack of established roles and responsibilities between primary and specialty care providers (e.g., responsibility for follow-up and ongoing care).11 The patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model is intended to facilitate high-value healthcare via coordination across healthcare settings and within the community, enhanced communication between providers, and a focus on quality of care delivery.6 Although definitions of PCMH do not explicitly state the inclusion of specialists, our findings highlight the unique opportunity that exists for care models to include specialty providers to facilitate timely access to high-quality care.

Strengths of this study include the exploration of a novel model to extend the PCMH model to include the skill sets of GI specialty expertise, the ability to evaluate the effect of this model within a well-established PCMH serving a large, defined population, and a unified EHR and billing system which allowed for adequate capture of diagnostic and visit services acquired by our empaneled patient population.

Limitations of our study include those characteristic of a retrospective, observational study including risk of selection bias. We did utilize a propensity scoring matching technique that helps to minimize the effects of this type of bias. Although we were thorough in collecting and utilizing as many patient characteristics that made sense in our propensity match, our study remains at risk of uncontrolled confounding. Our study also lacked the ability to assess the impact of curbside consults and e-consults which serve a large part of the ICS-GI practice, as our EHR systems of the time did not capture these types of consultation. Our study may be underpowered to detect true differences in visit and testing utilization, particularly when looking within our individual GI condition groups. Finally, due to the integrated practice model and recourse availability in our practice, ease of translatability of our findings to other healthcare settings may be different.

We observed that an embedded specialist in primary care model is associated with improved care coordination without compromising patient safety. The PCMH could be extended to include subspecialty care. Opportunities exist to identify if patients with specific gastrointestinal diseases are optimally suited for this type of care delivery.

Funding

This study was funded by the Mayo Clinic Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery and the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.St Sauver JL, Warner DO, Yawn BP, et al. Why patients visit their doctors: assessing the most prevalent conditions in a defined American population. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2013;88(1):56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peery AF, Crockett SD, Murphy CC, et al. Burden and Cost of Gastrointestinal, Liver, and Pancreatic Diseases in the United States: Update 2018. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(1):254–272.e211. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Surveillance for Viral Hepatitis – United States, 2017. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2017surveillance/index.htm. Accessed March 3, 2020, 2020.

- 4.Niv Y, Dickman R, Levi Z, et al. Establishing an integrated gastroenterology service between a medical center and the community. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(7):2152–2158. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i7.2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keely E, Canning S, Saloojee N, Afkham A, Liddy C. Improving Access to Gastroenterologist Using eConsultation: A Way to Potentially Shorten Wait Times. Journal of the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology. 2018;1(3):124–128. doi: 10.1093/jcag/gwy017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson GL, Powers BJ, Chatterjee R, et al. The patient centered medical home. A systematic review. Annals of internal medicine. 2013;158(3):169–178. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi PY, St Sauver JL, Finney Rutten LJ, et al. Health outcomes in diabetics measured with Minnesota Community Measurement quality metrics. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2015;8:1–8. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S71726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young NP, Elrashidi MY, Crane SJ, Ebbert JO. Pilot of integrated, colocated neurology in a primary care medical home. J Eval Clin Pract. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of chronic diseases. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elrashidi MY, Philpot LM, Young NP, et al. Effect of integrated community neurology on utilization, diagnostic testing, and access. Neurology Clinical practice. 2017;7(4):306–315. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim B, Lucatorto MA, Hawthorne K, et al. Care coordination between specialty care and primary care: a focus group study of provider perspectives on strong practices and improvement opportunities. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2015;8:47–58. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S73469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]